A Comprehensive Guide to Comparing Machine Learning Models for Prediction in Drug Development

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to compare and evaluate machine learning (ML) prediction models.

A Comprehensive Guide to Comparing Machine Learning Models for Prediction in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to compare and evaluate machine learning (ML) prediction models. It covers foundational principles, from defining regression and classification tasks to selecting appropriate evaluation metrics like MAE, RMSE, and AUC-ROC. The guide explores methodological applications of ML in drug discovery, including target identification and clinical trial optimization, and addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies for robust model development. Finally, it details rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques, including statistical testing and performance benchmarking against traditional methods, to ensure reliable and interpretable results for critical biomedical decisions.

Core Principles of Predictive Machine Learning in Biomedicine

In biomedical research, the accurate prediction of health outcomes is paramount for advancing diagnostic precision, prognostic stratification, and personalized treatment strategies. This endeavor relies heavily on supervised machine learning, where models learn from labeled historical data to forecast future events [1]. The choice of the fundamental prediction approach—regression or classification—is the first and most critical step, dictated entirely by the nature of the target variable the researcher aims to predict [2] [3].

Regression models are employed when predicting continuous numerical values, such as a patient's blood pressure, the exact concentration of a biomarker, or the anticipated survival time [1]. In contrast, classification models are used to predict discrete categorical outcomes, such as whether a tumor is malignant or benign, a tissue sample is cancerous or healthy, or a patient will respond to a drug or not [2] [1]. While this distinction may seem straightforward, the practical implications for model design, performance evaluation, and clinical interpretation are profound. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches within a biomedical context, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Core Conceptual Distinctions and Their Biomedical Implications

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between regression and classification tasks, highlighting their distinct goals and evaluation mechanisms in a biomedical setting.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Regression and Classification

| Feature | Regression | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Output Type | Continuous numerical value [2] [1] | Discrete categorical label [2] [1] |

| Primary Goal | Model the relationship between variables to predict a quantity; to fit a best-fit line or curve through data points [2] | Separate data into classes; to learn a decision boundary between categories [2] |

| Common Loss Functions | Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Huber Loss [2] [4] | Binary Cross-Entropy (Log Loss), Categorical Cross-Entropy, Hinge Loss [2] |

| Representative Algorithms | Linear Regression, Ridge/Lasso Regression, Regression Trees [1] | Logistic Regression, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) [5] [6] |

| Biomedical Example | Predicting disease progression score, patient length of stay, or drug dosage [1] | Diagnosing disease (e.g., cancer vs. no cancer), classifying cell types, or detecting fraudulent insurance claims [2] [1] |

The logical choice between these two paradigms flows from a simple, initial question about the nature of the target outcome. This decision process is outlined below.

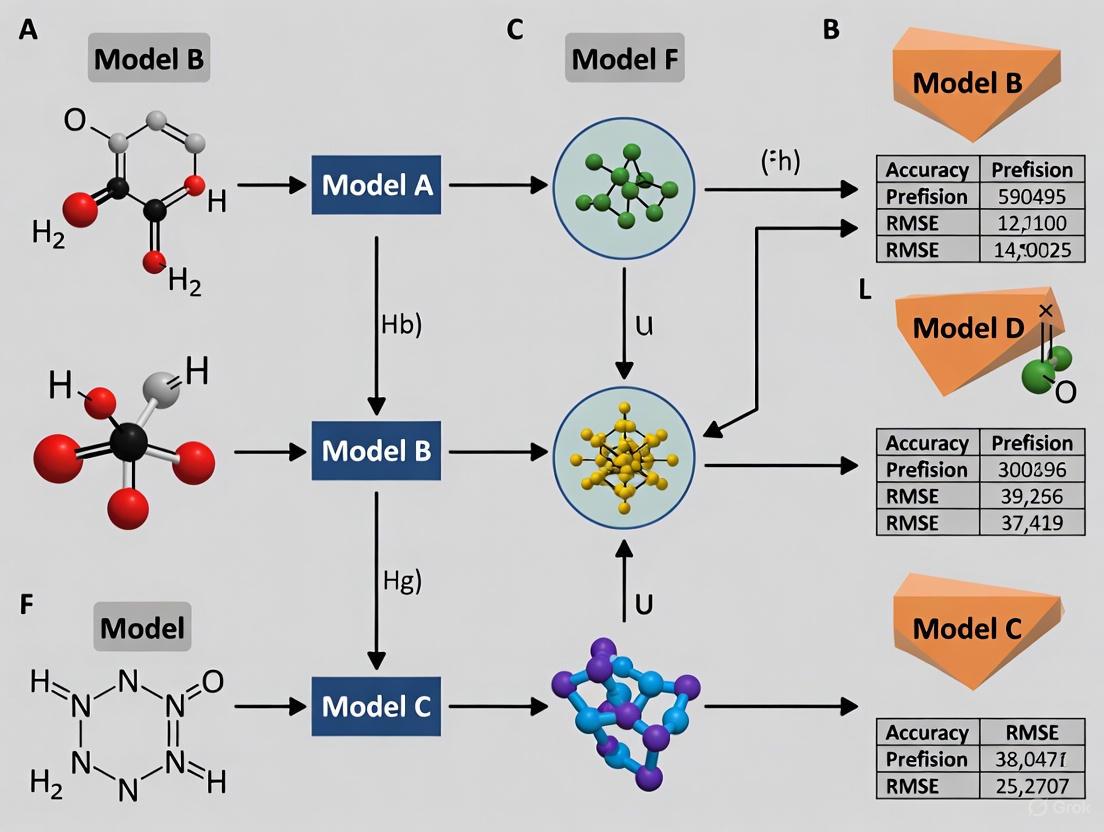

Figure 1: A decision workflow for choosing between regression and classification.

Performance Metrics: Quantifying Success in Different Tasks

The criteria for judging model performance are fundamentally different for regression and classification, reflecting their distinct objectives.

Metrics for Regression

Regression metrics quantify the distance or error between predicted and actual continuous values [4].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Regression Models

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation & Biomedical Implication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | (\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N} | yi - \hat{y}i | ) | Average absolute error. Robust to outliers. Easy to interpret (e.g., average error in predicted days of hospital stay) [4]. |

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | (\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2) | Average of squared errors. Heavily penalizes larger errors, making it sensitive to outliers [4]. | ||

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | (\sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2}) | Square root of MSE. Error is on the same scale as the original variable, aiding interpretation [4]. | ||

| R² (R-Squared) | (1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^{N} (yi - \hat{y}i)^2}{\sum{i=1}^{N} (y_i - \bar{y})^2}) | Proportion of variance in the target variable explained by the model. Ranges from -∞ to 1 (higher is better) [4]. |

Metrics for Classification

Classification performance is evaluated using metrics derived from the confusion matrix, which cross-tabulates predicted and actual classes [7] [4]. For a binary classification task, the confusion matrix is structured as follows:

Table 3: The Confusion Matrix for Binary Classification

| Predicted: Negative | Predicted: Positive | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual: Negative | True Negative (TN) | False Positive (FP) |

| Actual: Positive | False Negative (FN) | True Positive (TP) |

From this matrix, several key metrics are derived, each offering a different perspective on performance.

Table 4: Key Performance Metrics for Classification Models

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation & Biomedical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (\frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN}) | Overall proportion of correct predictions. Can be misleading with class imbalance [7] [4]. |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | (\frac{TP}{TP + FN}) | Ability to correctly identify positive cases. Critical when missing a disease (false negative) is dangerous [7]. |

| Specificity | (\frac{TN}{TN + FP}) | Ability to correctly identify negative cases. Important when false positives lead to unnecessary treatments [7]. |

| Precision | (\frac{TP}{TP + FP}) | When prediction is positive, how often is it correct? Needed when false positives are a key concern [7]. |

| F1-Score | (2 \times \frac{Precision \times Recall}{Precision + Recall}) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Useful when a balanced measure is needed [7] [4]. |

| AU-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve | Measures the model's ability to separate classes across all possible thresholds. Value from 0 to 1 (higher is better) [7]. |

Experimental Comparison: A Case Study in Stress Detection

A seminal study provides a direct, empirical comparison of regression and classification models for a biomedical prediction task: stress detection using wrist-worn sensors [8].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

- Dataset: The AffectiveROAD dataset, containing biosignal data (Blood Volume Pulse (BVP), Skin Temperature (ST), etc.) from Empatica E4 devices worn by participants during driving tasks, which included both stressful (city driving) and less stressful (highway) conditions [8].

- Target Variable: Unique continuous subjective stress estimates (scale 0-1) collected and validated in real-time, providing a ground truth for regression. For classification, these continuous values were discretized into "stressed" or "not-stressed" classes [8].

- Data Preprocessing & Feature Extraction: Signals were divided into 60-second windows with a 0.5-second slide. A total of 119 features were extracted from accelerometer (ACC), electrodermal activity (EDA), BVP, and ST signals [8].

- Models and Validation:

- Classification: Implemented using a Random Forest classifier.

- Regression: Implemented using a Bagged tree-based ensemble model.

- Validation Strategy: Both user-independent (leave-one-subject-out) and personal models were tested. Subject-wise feature selection was also applied to improve user-independent recognition [8].

Key Experimental Findings and Data

The study yielded critical results that directly inform the choice between regression and classification.

Table 5: Comparative Performance of Regression vs. Classification for Stress Detection [8]

| Model Type | Feature Set | Average Balanced Accuracy (Classification) | Average Balanced Accuracy (Regression + Discretization) |

|---|---|---|---|

| User-Independent | BVP + Skin Temperature | 74.1% | 82.3% |

| User-Independent | All Features | 70.5% | 79.5% |

The core finding was that regression models outperformed classification models when the final task was to classify observations as stressed or not-stressed [8]. By first predicting a continuous stress value and then discretizing it, the model achieved a higher balanced accuracy (82.3%) than the classifier trained directly on discrete labels (74.1%). This suggests that modeling the underlying continuous nature of a phenomenon like stress, even for a discrete outcome, can capture more nuanced information and lead to superior performance. Furthermore, the study found that subject-wise feature selection for user-independent models could improve detection rates more than building personal models from an individual's data [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Algorithms and Reagents

Successful implementation of regression and classification models requires a suite of algorithmic tools and, in the case of biomedical applications, physical research reagents.

Essential Machine Learning Algorithms

Table 6: Key Machine Learning Algorithms for Biomedical Prediction

| Algorithm | Prediction Type | Brief Description & Biomedical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Classification, Regression | An ensemble of decision trees. Robust and often provides high accuracy. Used for disease diagnosis and outcome prediction [8] [6]. |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Classification, (Regression) | Finds an optimal hyperplane to separate classes. Effective in high-dimensional spaces, such as for genomic data classification [5] [9]. |

| Logistic Regression | Classification | A linear model for probability estimation of binary or multi-class outcomes. Widely used for risk stratification (e.g., predicting disease onset) [1]. |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | Classification, Regression | An ensemble technique that builds trees sequentially to correct errors. Noted for high predictive performance in complex biomedical tasks [10]. |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Classification, Regression | Multi-layered networks that learn hierarchical feature representations. Excel at tasks like medical image analysis and processing complex, multi-modal data [10] [9]. |

Experimental Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials used in the featured stress detection experiment [8], which serves as a template for the types of resources required in similar biomedical signal processing studies.

Table 7: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosignal-Based Prediction

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Empatica E4 Wrist-worn Device | A research-grade wearable sensor used to collect raw physiological data including acceleration (ACC), electrodermal activity (EDA), blood volume pulse (BVP), and skin temperature (ST) [8]. |

| AffectiveROAD Dataset | A publicly available dataset providing the labeled biosignal data and continuous stress annotations necessary for supervised model training and validation [8]. |

| Matlab (version 2018b) / Python with scikit-learn | Software environments for implementing feature extraction, machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Bagged Trees), and performance evaluation metrics [8] [7]. |

| Blood Volume Pulse (BVP) Sensor | Photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor within the Empatica E4 used to measure blood flow changes, from which features related to heart rate and heart rate variability are derived for stress detection [8]. |

The experimental workflow, from data acquisition to model deployment, integrates these reagents and algorithms into a cohesive pipeline, as visualized below.

Figure 2: A generalized experimental workflow for biomedical prediction tasks.

The choice between regression and classification is a foundational decision that shapes the entire machine learning pipeline in biomedical research. As evidenced by experimental data, the decision is not always binary; in some cases, solving a regression problem (predicting a continuous score) can yield better performance for a subsequent classification task than a direct classification approach [8]. The selection must be guided by the nature of the clinical or research question, the available target variable, and the desired output for decision-making. A clear understanding of the distinct metrics, algorithms, and experimental considerations for each approach, as outlined in this guide, empowers researchers and drug development professionals to build more effective and interpretable predictive models, ultimately accelerating progress in translational medicine.

The evolution of predictive modeling has transitioned from traditional statistical methods to modern artificial intelligence (AI), significantly enhancing accuracy and applicability across research domains. In fields ranging from healthcare to education, researchers and developers must navigate a complex landscape of modeling families, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. Traditional statistical approaches offer interpretability and established reliability, while machine learning (ML) algorithms excel at identifying complex, nonlinear patterns in large datasets. The most recent advancements in generative AI have further expanded capabilities for content creation and data augmentation. This guide provides a comprehensive, evidence-based comparison of these model families, focusing on their predictive performance, implementation requirements, and practical applications in research settings, enabling professionals to select optimal modeling strategies for their specific challenges.

Performance Comparison Across Model Families

Quantitative comparisons across diverse domains consistently demonstrate performance trade-offs between traditional statistical, machine learning, and AI approaches.

Table 1: Predictive Performance Across Domains and Model Families

| Domain | Application | Best Performing Model | Key Metric | Performance | Traditional Model Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Academic Performance Prediction | XGBoost [11] | R² | 0.91 | N/A |

| Education | Academic Performance Prediction | Voting Ensemble (Linear Regression, SVR, Ridge) [12] | R² | 0.989 | N/A |

| Healthcare | Cardiovascular Event Prediction | Random Forest/Logistic Regression [13] | AUC | 0.88 | Conventional risk scores (AUC: 0.79) |

| Medical Devices | Demand Forecasting | LSTM (Deep Learning) [14] | wMAPE | 0.3102 | Statistical models (lower accuracy) |

| Industry | General Predictive Modeling | Gradient Boosting [15] [16] | Accuracy | Highest with tuning | Random Forest (slightly lower accuracy) |

The performance advantages of more complex models come with specific resource requirements and implementation considerations.

Table 2: Computational Requirements and Scalability

| Model Family | Training Speed | Inference Speed | Data Volume Requirements | Hardware Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistical Models | Fast | Fastest | Low to Moderate | Standard CPU |

| Random Forest | Fast (parallel) [16] | Fast | Moderate to High | Multi-core CPU |

| Gradient Boosting | Slower (sequential) [15] [16] | Fast | Moderate to High | CPU or GPU |

| Deep Learning (LSTM) | Slowest | Fast | Highest | GPU accelerated |

| Generative AI | Very Slow | Variable | Highest | Specialized GPU |

Key Model Families and Methodologies

Traditional Statistical Models

Traditional statistical approaches form the foundation of predictive modeling, characterized by strong assumptions about data distributions and relationships. These include linear regression, logistic regression, time series models (e.g., Exponential Smoothing, SARIMAX), and conventional risk scores like GRACE and TIMI in healthcare [13] [14]. These models remain widely valued for their interpretability, computational efficiency, and well-established theoretical foundations. They typically operate with minimal hyperparameter tuning and provide confidence intervals and p-values for rigorous statistical inference. However, their performance may diminish when faced with complex, non-linear relationships or high-dimensional data [13].

Machine Learning Ensemble Models

Random Forest

Random Forest employs bagging (bootstrap aggregating) to build multiple decision trees independently on random data subsets, then aggregates predictions through averaging (regression) or voting (classification) [15] [16]. The algorithm introduces randomness through bootstrap sampling and random feature selection at each split, creating diverse trees that collectively reduce variance and overfitting.

Key Advantages: Robust to noise and overfitting, handles missing data effectively, provides native feature importance metrics, and offers faster training through parallelization [15] [16].

Limitations: Can become computationally complex with many trees, slower prediction times compared to single models, and less interpretable than individual decision trees [15].

Gradient Boosting Methods

Gradient boosting builds trees sequentially, with each new tree correcting errors of the previous ensemble [15] [16]. Unlike Random Forest's parallel approach, gradient boosting uses a stage-wise additive model where new trees are fitted to the negative gradients (residuals) of the current model, gradually minimizing a differentiable loss function.

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) incorporates regularization (L1/L2) to prevent overfitting, handles missing values internally, employs parallel processing, and uses depth-first tree pruning [17]. Its robustness and flexibility make it a top choice for structured tabular data.

CatBoost specializes in handling categorical features natively without extensive preprocessing, uses ordered boosting to prevent overfitting, builds symmetric trees for faster inference, and provides superior ranking capabilities [18].

LightGBM utilizes histogram-based algorithms for faster computation, employs leaf-wise tree growth for higher accuracy, implements Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) to focus on informative instances, and uses Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB) to reduce dimensionality [17].

Diagram 1: Random Forest vs Gradient Boosting Architectures

Deep Learning and Generative AI

Deep Learning models, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), excel at capturing complex temporal dependencies and patterns in sequential data [14]. These models automatically learn hierarchical feature representations through multiple processing layers, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering in many cases.

Generative AI represents a transformative advancement within machine learning, capable of creating new content rather than merely predicting outcomes. As noted by MIT experts, "Machine learning captures complex correlations and patterns in the data we have. Generative AI goes further" [19]. These models can augment traditional machine learning workflows by generating synthetic data for training, assisting with feature engineering, and explaining model outcomes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Evaluation Framework

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for meaningful model comparisons. Standard evaluation methodologies include:

Data Preprocessing: Appropriate handling of missing values (imputation vs. removal), categorical variable encoding (one-hot, label, or target encoding), feature scaling (normalization, standardization), and train-test splitting with temporal considerations for time-series data [12].

Performance Metrics: Selection of domain-appropriate metrics including R² (coefficient of determination), AUC (Area Under ROC Curve), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), MAE (Mean Absolute Error), wMAPE (Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error), and precision-recall curves for imbalanced datasets [11] [12] [13].

Validation Strategies: Implementation of k-fold cross-validation, stratified sampling for imbalanced datasets, temporal cross-validation for time-series data, and external validation on completely held-out datasets to assess generalizability [13].

Interpretability Methods

Modern interpretability techniques are crucial for building trust and understanding in complex models:

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Calculates feature importance by measuring the marginal contribution of each feature to the prediction across all possible feature combinations, providing both global and local interpretability [11] [18] [12].

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Creates local surrogate models to approximate complex model predictions for individual instances, highlighting features most influential for specific predictions [12].

Native Model Interpretation: Tree-based models offer built-in feature importance metrics (e.g., Gini importance, permutation importance), while CatBoost provides advanced visualization tools like feature analysis charts showing how predictions change with feature values [18].

Diagram 2: Standard Model Development Workflow

Decision Framework for Model Selection

Choosing the appropriate model family depends on multiple factors relating to data characteristics, resource constraints, and project objectives.

Table 3: Model Selection Guidelines Based on Project Requirements

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need quick baseline with minimal tuning | Random Forest [15] [16] | Robust to noise, parallel training, lower overfitting risk | Minimal hyperparameter tuning required |

| Maximum predictive accuracy | Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM) [11] [15] [16] | Sequentially corrects errors, captures complex patterns | Requires careful hyperparameter tuning |

| Dataset with many categorical features | CatBoost [18] [17] | Native categorical handling, reduces preprocessing | Limited tuning for categorical-specific parameters |

| Large-scale datasets with high dimensionality | LightGBM [17] | Histogram-based optimization, leaf-wise growth | Monitor for overfitting with small datasets |

| Time-series/sequential data | LSTM/GRU [14] | Captures temporal dependencies, long-range connections | Requires substantial data, computational resources |

| Need model interpretability | Traditional statistical models or Random Forest [13] | Transparent mechanics, native feature importance | Trade-off between interpretability and performance |

| Limited labeled data | Traditional methods or Generative AI for synthetic data [19] | Lower data requirements, established reliability | Generative AI requires validation of synthetic data |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools and Libraries for Predictive Modeling Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boosting Libraries | XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM [18] [17] | High-performance gradient boosting implementations | Structured/tabular data prediction tasks |

| Interpretability Frameworks | SHAP, LIME [11] [12] | Model prediction explanation and feature importance analysis | Model debugging, validation, and explanation |

| Deep Learning Platforms | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Neural network design and training | Complex pattern recognition, image, text, sequence data |

| Traditional Statistical Packages | statsmodels, scikit-learn | Classical statistical modeling and analysis | Baseline models, interpretable predictions |

| Automated ML Tools | AutoML frameworks | Streamlined model selection and hyperparameter optimization | Rapid prototyping, resource-constrained environments |

| Data Visualization Libraries | Matplotlib, Seaborn, Plotly | Exploratory data analysis and result communication | Data understanding, pattern identification, reporting |

The evolution from traditional statistics to modern AI has created a rich ecosystem of modeling approaches, each with distinct advantages for research applications. Traditional statistical models provide interpretability and established methodologies, ensemble methods like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting offer robust performance for structured data, while deep learning excels at complex pattern recognition in high-dimensional spaces. The emerging integration of generative AI with predictive modeling further expands possibilities for data augmentation and workflow optimization. Selection should be guided by data characteristics, computational resources, interpretability requirements, and performance targets rather than defaulting to the most complex approach. As these technologies continue evolving, researchers should maintain focus on methodological rigor, appropriate validation, and domain-specific relevance to ensure scientific validity and practical utility.

Evaluating the performance of predictive models is a cornerstone of reliable machine learning research. For regression tasks, particularly in scientific fields like drug discovery, selecting the appropriate metric is crucial, as it directly influences model selection and the interpretation of results. This guide provides an objective comparison of three fundamental metrics—Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²)—to equip researchers with the knowledge to make informed decisions in their prediction studies.

Core Metric Definitions and Mathematical Foundations

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of MAE, RMSE, and R-squared.

| Metric | Mathematical Formula | Interpretation | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE(Mean Absolute Error) | ( \text{MAE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} | yi - \hat{y}i | ) [20] [21] | Average magnitude of error, in the same units as the target variable. | Robust to outliers [21] [22]. Simple and intuitive interpretation [21]. | Does not penalize large errors heavily, which may be undesirable in some applications [21]. |

| RMSE(Root Mean Squared Error) | ( \text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2} ) [20] [22] | Standard deviation of the prediction errors. Same units as the target. | Sensitive to large errors; penalizes larger deviations more heavily [21] [22]. Mathematically convenient for optimization [21]. | Highly sensitive to outliers, which can dominate the metric's value [21] [22]. Less interpretable than MAE on its own [20]. | ||

| R²(R-squared) | ( R^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}i)^2}{\sum{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2} ) [20] [23] | Proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. [24] [23] | Scale-independent, providing a standardized measure of model performance (range: 0 to 1, higher is better) [24]. Intuitive as a percentage of variance explained. [23] | Can be misleading with complex models or small datasets, leading to overfitting [23]. A value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, which is often unrealistic and may signal overfitting. [25] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for selecting the most appropriate evaluation metric based on the specific context and goals of your research.

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting regression metrics.

Performance Comparison in Experimental Studies

Data from recent pharmacological and clinical studies demonstrate how these metrics are used to compare model performance in real-world scenarios.

Example 1: AI in Drug Discovery

A 2025 study comparing machine learning models for predicting pharmacokinetic parameters provides a clear example of multi-metric evaluation [26].

| Model Type | R² Score | MAE Score |

|---|---|---|

| Stacking Ensemble | 0.92 | 0.062 |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | 0.90 | Not Reported |

| Transformer | 0.89 | Not Reported |

| Random Forest & XGBoost | Lower than AI models | Not Reported |

The stacking ensemble model, with its high R² and low MAE, was identified as the most accurate, demonstrating its superior ability to explain the variance in the data while maintaining the smallest average prediction error [26].

Example 2: Clinical Medicine Context

Interpretation of R² must be contextual. A 2024 review in clinical medicine found that many impactful studies report R² values much lower than those seen in physical sciences or AI research [25].

| Clinical Condition | Reported R² Value |

|---|---|

| Pediatric Cardiac Arrest (Predictors: sex, time to EMS, etc.) | 0.245 [25] |

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage (Model with 16 factors) | 0.17 [25] |

| Sepsis Mortality (Predictors: SOFA score, etc.) | 0.167 [25] |

| Traumatic Brain Injury Outcome | 0.18 - 0.21 [25] |

The review concluded that in complex clinical contexts influenced by genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors, an R² as low as >15% can be considered meaningful, provided the model variables are statistically significant [25]. This contrasts sharply with the R² > 0.9 reported in the AI drug discovery study [26], highlighting the critical importance of domain context.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details key resources, both data- and software-based, that are foundational for conducting machine learning prediction research in drug development.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [26] | Bioactivity Database | A large, open-source repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used as a standardized dataset for training and validating predictive models. [26] |

| GDSC Dataset [27] | Pharmacogenomic Database | Provides genomic profiles and drug sensitivity data (e.g., IC50 values) for hundreds of cancer cell lines, enabling the development of drug response prediction models. [27] |

| Scikit-learn [27] [23] | Python Library | Offers accessible implementations of numerous regression algorithms (Elastic Net, SVR, Random Forest, etc.) and evaluation metrics (MAE, MSE, R²), making it a staple for ML prototyping. [27] [23] |

| Stacking Ensemble Model [26] [28] | Machine Learning Method | A advanced technique that combines multiple base models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) through a meta-leader to achieve higher predictive accuracy, as demonstrated in state-of-the-art studies. [26] [28] |

MAE, RMSE, and R² are complementary tools, each providing a unique lens for evaluating regression models. There is no single "best" metric; the optimal choice is dictated by your research question, the nature of your data, and the cost associated with prediction errors. A robust evaluation strategy involves reporting multiple metrics to provide a comprehensive view of model performance, from the average magnitude of errors (MAE) and the impact of outliers (RMSE) to the overall proportion of variance explained (R²). By applying these metrics judiciously and with an understanding of their interpretations, researchers can make more reliable, reproducible, and meaningful advancements in predictive science.

The Role of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) in Modern Pharma

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) represents a paradigm shift in how pharmaceuticals are discovered and developed, moving away from traditional, often empirical, approaches toward a quantitative, data-driven framework. MIDD employs a suite of computational techniques—including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP)—to integrate data from nonclinical and clinical sources to inform decision-making [29]. This approach is critically needed to address the unsustainable status quo in the pharmaceutical industry, characterized by Eroom's Law (the inverse of Moore's Law), which describes the declining productivity and skyrocketing costs of drug development over time [30]. The high cost, failure rates, and risks associated with long development timelines have made attracting necessary funding for innovation increasingly difficult.

The core value proposition of MIDD lies in its ability to quantitatively predict drug behavior, efficacy, and safety, thereby de-risking development and increasing the probability of regulatory success. A recent analysis in Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics estimates that the use of MIDD yields "annualized average savings of approximately 10 months of cycle time and $5 million per program" [30]. Furthermore, regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) strongly encourage MIDD approaches, formalizing their support through programs like the MIDD Paired Meeting Program, which provides sponsors with opportunities to discuss MIDD approaches for specific drug development programs [31]. This program specifically focuses on dose selection, clinical trial simulation, and predictive safety evaluation, underscoring the critical areas where MIDD adds value.

Core MIDD Methodologies and Comparison with AI-Driven Approaches

The MIDD toolkit encompasses a diverse set of quantitative methods, each suited to specific questions throughout the drug development lifecycle. The selection of a particular methodology is guided by a "fit-for-purpose" principle, ensuring the model is closely aligned with the key question of interest and the context of its intended use [32]. The following table summarizes the primary MIDD tools and their applications, providing a foundation for comparison with emerging AI/ML methodologies.

Table 1: Key MIDD Methodologies and Their Primary Applications in Drug Development

| Methodology | Description | Primary Applications in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | Mechanistic modeling that simulates drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion based on human physiology and drug properties [32]. | Predicting drug-drug interactions, dose selection in special populations (e.g., organ impairment), and supporting bioequivalence assessments [32] [30]. |

| Population PK (PPK) and Exposure-Response (ER) | Models that describe drug exposure (PK) and its relationship to efficacy/safety outcomes (PD) while accounting for variability between individuals [32]. | Optimizing dosing regimens, identifying patient factors (e.g., weight, genetics) that influence drug response, and supporting label updates [32] [29]. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Integrative models that combine systems biology with pharmacology to simulate drug effects in the context of disease pathways and biological networks [32]. | Target validation, biomarker identification, understanding complex drug mechanisms, and exploring combination therapies [32]. |

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Quantitative analysis of summary-level data from multiple clinical trials to understand the competitive landscape and drug performance [32]. | Informing clinical trial design, benchmarking against standard of care, and supporting go/no-go decisions [32]. |

The rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) introduces a powerful, complementary set of tools to the drug development arsenal. While traditional MIDD models are often rooted in physiological or pharmacological principles, ML is focused on making predictions as accurate as possible by learning patterns from large datasets, often without explicit pre-programming of biological rules [33]. The table below offers a structured comparison between well-established MIDD approaches and emerging AI/ML techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional MIDD Approaches vs. AI/ML Techniques in Drug Development

| Feature | Traditional MIDD Approaches | AI/ML Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Infer relationships between variables (e.g., dose, exposure, response) and generate mechanistic insight [33]. | Make accurate predictions from data patterns, often functioning as a "black box" [33]. |

| Data Requirements | Structured, well-curated datasets. Effective even with a limited number of clinically important variables [33]. | Large, high-dimensional datasets (e.g., 'omics', imaging, EHRs). Excels when the number of variables far exceeds observations [33] [34]. |

| Interpretability | High; produces "clinician-friendly" measures like hazard ratios and supports causal inference [33]. | Often low, especially in complex models like neural networks, though methods like SHAP exist to improve explainability [33] [34]. |

| Key Strengths | Mechanistic insight, established regulatory pathways, suitability for dose optimization and trial design [32] [31]. | Handling unstructured data, identifying complex, non-linear patterns, and accelerating discovery tasks like molecule design [35] [34]. |

| Ideal Application Context | Public health research, dose justification, clinical trial simulation, and regulatory submission [33] [31]. | 'Omics' analysis, digital pathology, patient phenotyping from EHRs, and novel drug candidate generation [33] [35]. |

A synergistic integration of the two approaches is increasingly seen as the most powerful path forward. Hybrid models that combine AI/ML with MIDD are emerging; for example, AI can automate model development steps or analyze large datasets to generate inputs for mechanistic PBPK or QSP models [34] [30]. This fusion promises to enhance both the efficiency and predictive power of quantitative drug development.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows in MIDD and AI

A Standard MIDD Workflow: From Data to Regulatory Submission

The application of MIDD follows a structured, iterative process. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for implementing a MIDD approach, from defining the problem to regulatory interaction, which is critical for ensuring model acceptance.

Diagram Title: MIDD Workflow from Concept to Regulation

A key component of the modern regulatory landscape is the FDA's MIDD Paired Meeting Program [31]. This program allows sponsors to have an initial meeting with the FDA to discuss a proposed MIDD approach, followed by a follow-up meeting after refining the model based on FDA feedback. This iterative dialogue de-risks the use of innovative modeling and simulation in regulatory decision-making.

An AI-Enhanced Protocol for Predicting Drug-Target Interactions

In the AI/ML domain, novel models are being developed to tackle specific challenges like predicting drug-target interactions (DTI). The following workflow details the protocol for the Context-Aware Hybrid Ant Colony Optimized Logistic Forest (CA-HACO-LF) model, a representative advanced ML approach cited in the literature [36].

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for CA-HACO-LF Model for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

| Step | Protocol Detail | Tools & Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Acquisition | Obtain the "11,000 Medicine Details" dataset from Kaggle. | Public dataset repository (Kaggle) [36]. |

| 2. Data Pre-processing | Clean and standardize textual data (drug descriptions, target information). | Text normalization (lowercasing, punctuation removal), stop word removal, tokenization, and lemmatization [36]. |

| 3. Feature Extraction | Convert processed text into numerical features that capture semantic meaning. | N-Grams (for sequential pattern analysis) and Cosine Similarity (to assess semantic proximity between drug descriptions) [36]. |

| 4. Feature Optimization | Select the most relevant features to improve model performance and efficiency. | Customized Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) to intelligently traverse the feature space [36]. |

| 5. Classification & Prediction | Train the model to identify and predict drug-target interactions. | Hybrid Logistic Forest (LF) classifier, which combines a Random Forest with Logistic Regression [36]. |

| 6. Performance Validation | Evaluate the model against established benchmarks using multiple metrics. | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC-ROC, RMSE, and Cohen's Kappa [36]. |

The logical flow of this AI-driven protocol, from raw data to a validated predictive model, is visualized in the following diagram.

Diagram Title: AI Model for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective application of MIDD and AI requires a combination of sophisticated software, computational resources, and data. The following table catalogs key "research reagents" essential for work in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MIDD and AI-Driven Drug Development

| Tool Category | Example Tools/Platforms | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biosimulation Software | Certara's Suite (e.g., Simcyp, NONMEM), Schrödinger's Physics-Enabled Platform | Platforms for PBPK, population PK/PD, and QSP modeling. Used for mechanistic simulation of drug behavior and trial outcomes [35] [30]. |

| AI/ML Drug Discovery Platforms | Exscientia, Insilico Medicine, Recursion, BenevolentAI | End-to-end platforms using generative chemistry, phenomics, and knowledge graphs for target identification and molecule design [35]. |

| Cloud Computing Infrastructure | Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud | Scalable computational power and data storage for running large-scale simulations and training complex AI/ML models [35] [34]. |

| Curated Datasets | DrugCombDB, Open Targets, Kaggle Medicinal Datasets | Structured biological, chemical, and clinical data essential for training and validating both MIDD and AI/ML models [36]. |

| Programming & Analytics Environments | Python (with libraries like Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch), R | Open-source environments for developing custom ML models, performing statistical analysis, and automating data workflows [34] [36]. |

Model-Informed Drug Development has firmly established itself as a cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical research, providing a robust, quantitative framework to navigate the complexities of drug development from discovery through post-market optimization. The integration of AI and ML methodologies is not replacing MIDD but rather augmenting it, creating a powerful synergy. AI brings unparalleled scale and pattern recognition capabilities to data-rich discovery problems, while MIDD provides the mechanistic understanding and regulatory rigor needed for clinical development and approval.

The future of the field lies in the continued democratization of these tools—making them more accessible to non-modelers through improved user interfaces and AI-assisted automation—and the deeper fusion of mechanistic and AI-driven models [30]. As these technologies mature and regulatory pathways become even more clearly defined, the industry is poised to finally reverse Eroom's Law, delivering innovative therapies to patients more rapidly, cost-effectively, and safely than ever before.

Implementing ML Models for Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is transforming the landscape of clinical trial design, offering sophisticated solutions to long-standing challenges in drug development. Clinical trials face unprecedented challenges including recruitment delays affecting 80% of studies, escalating costs exceeding $200 billion annually in pharmaceutical R&D, and success rates below 12% [37]. ML models present a transformative approach to address these systemic inefficiencies across the clinical trial lifecycle, from initial target identification to final trial design optimization. These technologies demonstrate particular strength in enhancing predictive accuracy, improving patient selection, and optimizing trial parameters, ultimately accelerating the development of new therapies while maintaining scientific rigor and patient safety.

The application of ML in clinical research represents a paradigm shift from traditional statistical methods toward data-driven approaches capable of identifying complex, non-linear relationships in multidimensional clinical data. Where conventional statistical models like logistic regression operate under strict assumptions of linearity and independence, ML algorithms can autonomously learn patterns from data, handling complex interactions without manual specification beforehand [38]. This capability is particularly valuable in clinical trial design, where numerous patient-specific, molecular, and environmental factors interact in ways that traditional methods may fail to capture. The resulting models offer substantial improvements in predicting trial outcomes, optimizing eligibility criteria, and generating synthetic control arms, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and success rates of clinical development programs.

Comparative Performance Analysis of ML Models

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Applications

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models in Predictive Tasks

| Model Category | Specific Model | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Methods | XGBoost | Academic Performance Prediction | R² = 0.91, 15% MSE reduction | [11] |

| Ensemble Methods | XGBoost | Temperature Prediction in PV Systems | MAE = 1.544, R² = 0.947 | [39] |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forest | MACCE Prediction Post-PCI | AUROC: 0.88 (95% CI 0.86-0.90) | [13] |

| Deep Learning | LSTM (60-day) | Market Price Forecasting | R² = 0.993 | [40] |

| Large Language Models | GPT-4-Turbo-Preview | RCT Design Replication | 72% overall accuracy | [41] |

| Traditional Statistical | Logistic Regression | Clinical Prediction Models | AUROC: 0.79 (95% CI 0.75-0.84) | [13] |

Table 2: Specialized Performance of ML Models in Clinical Trial Applications

| Model Type | Clinical Application | Strengths | Limitations | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Networks (Digital Twin Generators) | Synthetic control arms | Reduces control participants while maintaining statistical power | Requires extensive historical data for training | [42] |

| Large Language Models | RCT design generation | 88% accuracy in recruitment design, 93% in intervention planning | 55% accuracy in eligibility criteria design | [41] |

| Predictive Analytics | Trial outcome forecasting | 85% accuracy in forecasting trial outcomes | Potential algorithmic bias concerns | [37] |

| Ensemble Methods | Patient stratification | Handles complex feature interactions, native missing data handling | Lower interpretability than traditional statistics | [38] |

| Reinforcement Learning | Adaptive trial designs | Enables real-time modifications to trial protocols | Complex implementation requiring specialized expertise | [43] |

The performance advantages of ML models over traditional statistical approaches are evident across multiple domains. In predictive modeling tasks, ensemble methods like XGBoost and Random Forest consistently demonstrate superior performance, with XGBoost achieving remarkable R² values of 0.91 in educational prediction [11] and 0.947 in environmental forecasting [39]. Similarly, for predicting Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events (MACCE) after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), ML-based models significantly outperformed conventional risk scores with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.88 compared to 0.79 for traditional scores [13]. These performance gains are attributed to the ability of ML algorithms to capture complex, non-linear relationships and feature interactions that conventional methods often miss.

In clinical trial specific applications, ML models show particular promise in enhancing various design elements. Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4-Turbo-Preview demonstrate substantial capabilities in generating clinical trial designs, achieving 72% overall accuracy in replicating Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) designs, with particularly strong performance in recruitment (88% accuracy) and intervention planning (93% accuracy) [41]. Digital twin technology, powered by proprietary neural network architectures, enables the creation of virtual control arms that can reduce the number of required control participants while maintaining statistical power [42]. Furthermore, AI-powered predictive analytics achieve 85% accuracy in forecasting trial outcomes, contributing to accelerated trial timelines (30-50% reduction) and substantial cost savings (up to 40% reduction) [37].

Context-Dependent Performance Considerations

The performance advantages of ML models are not universal but depend significantly on dataset characteristics and application context. The "no free lunch" theorem in ML suggests that no single algorithm performs optimally across all possible scenarios [38]. The comparative effectiveness of ML models versus traditional statistical approaches is heavily influenced by factors such as sample size, data linearity, number of candidate predictors, and minority class proportion. For instance, while deep learning models like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks demonstrate exceptional performance in capturing temporal dependencies for market price forecasting (R² = 0.993) [40], they require substantially larger datasets and more computational resources compared to traditional methods.

The interpretability-performance tradeoff represents a critical consideration in clinical trial applications where model transparency is often essential for regulatory approval and clinical adoption. While ensemble methods like XGBoost and Random Forest typically offer superior predictive accuracy, their "black-box" nature complicates explanation to end users and requires post hoc interpretation methods like Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) [11] [38]. In contrast, traditional statistical models like logistic regression provide high interpretability through directly understandable coefficients but may struggle with complex nonlinear relationships [38]. This tradeoff necessitates careful model selection based on the specific requirements of each clinical trial application, balancing the need for accuracy against interpretability and implementation constraints.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Training and Validation Frameworks

Table 3: Standardized Experimental Protocols for ML Model Validation

| Protocol Component | Implementation Details | Purpose | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | 80% training, 20% testing | Ensure robust performance estimation | 5,000 samples split [39] |

| Cross-Validation | Time-series cross-validation | Prevent data leakage in temporal data | Respects chronological order [40] |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | Optuna optimization framework | Systematic parameter search | Enhanced LSTM performance [40] |

| Performance Metrics | MAE, RMSE, R², AUROC, BLEU, ROUGE-L | Comprehensive model assessment | Multiple error metrics [41] [39] [40] |

| Feature Importance Analysis | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretability | Identified key predictors [11] |

Robust experimental protocols are essential for ensuring the validity and reliability of ML models in clinical trial applications. The methodology typically begins with comprehensive data preprocessing, including cleaning, normalization, and categorical variable encoding to ensure dataset quality [11]. For predictive modeling tasks, datasets are commonly partitioned into training and testing subsets, with a typical split of 80% for training and 20% for testing, as demonstrated in environmental prediction studies using 5,000 samples [39]. For temporal data, time-series cross-validation is employed to respect chronological order and prevent data leakage between training and testing sets [40]. Hyperparameter optimization represents a critical step, with frameworks like Optuna enabling systematic search for optimal parameters to enhance model performance [40].

Model validation extends beyond simple accuracy metrics to encompass multiple dimensions of performance. In clinical prediction modeling, comprehensive evaluation includes discrimination (e.g., AUROC), calibration, classification metrics, clinical utility, and fairness [38]. For LLM applications in clinical trial design, quantitative assessment involves both accuracy measurements (degree of agreement with ground truth) and natural language processing-based metrics including Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU), Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE)-L, and Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering (METEOR) [41]. Qualitative assessment by clinical experts using Likert scales provides additional validation across domains such as safety, clinical accuracy, objectivity, pragmatism, inclusivity, and diversity [41]. This multifaceted validation approach ensures that models meet both statistical and clinical standards for implementation.

Domain-Specific Methodological Adaptations

The application of ML in clinical trial design requires specific methodological adaptations to address domain-specific challenges. For digital twin generation, specialized neural network architectures are purpose-built for clinical prediction, trained on large, longitudinal clinical datasets to create patient-specific outcome forecasts [42]. These models incorporate baseline patient data to simulate how individuals would have progressed under control conditions, enabling the creation of synthetic control arms. For adaptive trial designs, reinforcement learning algorithms are employed to enable real-time modifications to trial protocols based on interim results, with Bayesian frameworks maintaining statistical validity during these adaptations [43].

Eligibility optimization represents another area requiring specialized methodologies. ML-based approaches like Trial Pathfinder analyze completed trials and electronic health record data to systematically evaluate which eligibility criteria are truly necessary, broadening patient access without compromising safety [43]. This methodology involves comparing eligibility criteria from multiple completed Phase III trials to real-world patient data, demonstrating that exclusions based on specific laboratory values often have minimal impact on trial outcomes [43]. Similarly, AI-powered patient recruitment tools leverage natural language processing to match patient records with trial criteria, improving enrollment rates by 65% [37]. These domain-specific methodological innovations highlight how ML techniques must be adapted to address the unique requirements and constraints of clinical trial applications.

Visualization of ML Applications in Clinical Trials

ML Workflow in Clinical Trial Design

ML Model Selection Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for ML in Clinical Trials

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | Electronic Health Record (EHR) Harmonization | Curates, cleans, and harmonizes clinical datasets | Flatiron Health EHR database (61,094 NSCLC patients) [43] |

| Model Interpretability | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explains model predictions by quantifying feature importance | Identified socioeconomic factors in educational prediction [11] |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Optuna Framework | Automates hyperparameter search for optimal model configuration | Enhanced LSTM performance in market forecasting [40] |

| Digital Twin Generation | Proprietary Neural Network Architectures | Creates patient-specific outcome predictions for control arms | Unlearn's Digital Twin Generators (DTGs) [42] |

| Multi-Agent Systems | ClinicalAgent | Coordinates multiple AI agents for trial lifecycle management | Improved trial outcome prediction by 0.33 AUC [43] |

| Validation Metrics | BLEU, ROUGE-L, METEOR | NLP-based evaluation of language model outputs | Assessed LLM-generated clinical trial designs [41] |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | AWS, Google Cloud, Azure | Provides scalable infrastructure for complex simulations | Enabled in-silico trials without extensive in-house infrastructure [43] |

The successful implementation of ML in clinical trial design relies on a suite of specialized research tools and platforms that enable the development, validation, and deployment of predictive models. Data harmonization solutions like the Flatiron Health EHR database provide curated, cleaned, and harmonized clinical datasets essential for training robust ML models [43]. These preprocessed datasets address the critical challenge of data quality that affects approximately 50% of clinical trial datasets [37], enabling more reliable model development. For model interpretation, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) provides crucial explanatory capabilities by quantifying the contribution of each feature to individual predictions [11] [38]. This interpretability layer is particularly important in clinical applications where understanding model reasoning is essential for regulatory approval and clinical adoption.

Specialized computational frameworks form another critical component of the ML research toolkit for clinical trials. Hyperparameter optimization platforms like Optuna enable systematic parameter search, significantly enhancing model performance as demonstrated in LSTM applications for market forecasting [40]. For digital twin generation, proprietary neural network architectures purpose-built for clinical prediction enable the creation of patient-specific outcome forecasts that can reduce control arm sizes while maintaining statistical power [42]. Multi-agent AI systems like ClinicalAgent demonstrate the potential for autonomous coordination across the clinical trial lifecycle, improving trial outcome prediction by 0.33 AUC over baseline methods [43]. Cloud computing platforms including AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure provide the scalable infrastructure necessary for running complex in-silico trials without requiring extensive in-house computational resources [43]. Together, these tools create a comprehensive ecosystem supporting the integration of ML methodologies throughout the clinical trial design process.

Machine learning models demonstrate substantial potential to enhance clinical trial design across multiple application stages, from target identification to final protocol development. The comparative analysis reveals that while no single algorithm performs optimally across all scenarios, ensemble methods like XGBoost and Random Forest consistently achieve superior predictive accuracy for structured data tasks, while deep learning approaches like LSTM excel in temporal forecasting, and specialized neural networks power emerging applications like digital twin generation. The performance advantages of these ML approaches translate into tangible benefits for clinical trial efficiency, including accelerated timelines (30-50% reduction), cost savings (up to 40%), and improved recruitment rates (65% enhancement) [37].

The successful implementation of ML in clinical trial design requires careful consideration of the tradeoffs between model performance, interpretability, and implementation complexity. While ML models frequently outperform traditional statistical approaches in predictive accuracy, their "black-box" nature presents challenges for clinical adoption and regulatory approval. The emerging toolkit of interpretability methods like SHAP, combined with specialized research reagents and computational frameworks, helps address these concerns while enabling researchers to leverage the full potential of ML methodologies. As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into clinical trial design promises to enhance the efficiency, reduce the costs, and improve the success rates of clinical development programs, ultimately accelerating the delivery of new therapies to patients.

In the data-intensive fields of modern scientific research, including drug development and pharmacology, selecting the appropriate machine learning (ML) model is a critical determinant of success. The algorithmic landscape is broadly divided into supervised machine learning models, which learn from labeled historical data, and deep learning models, which use layered neural networks to automatically extract complex features. A more recent and advanced paradigm, Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs), has emerged, bridging data-driven learning with the principles of mechanistic modeling. These are not merely incremental improvements but represent a fundamental shift in how we approach temporal and continuous processes [44] [45].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three algorithmic families. The performance of any model is not inherently superior but is highly contingent on dataset characteristics and the specific scientific question at hand. As highlighted in clinical prediction modeling, there is no universal "golden method," and the choice involves navigating trade-offs between interpretability, data hunger, flexibility, and computational cost [38]. This analysis synthesizes recent comparative findings and experimental data to offer a structured framework for researchers to make an informed model selection.

Methodological Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison across different algorithmic families, a rigorous and standardized evaluation protocol is essential. The following section details the core methodologies and experimental designs commonly employed in benchmarking studies.

Core Algorithmic Definitions and Experimental Setup

Supervised Machine Learning (e.g., Logistic Regression): As defined in clinical prediction literature, statistical logistic regression is a theory-driven, parametric model that operates under conventional assumptions (e.g., linearity) and relies on researcher input for variable selection without data-driven hyperparameter optimization [38]. In comparative studies, datasets are typically split into training and test sets, with performance evaluated using metrics like Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC). It is crucial to report not just discrimination (AUROC) but also calibration and clinical utility to gain a comprehensive view of model performance [38].

Deep Learning (e.g., Multi-Layer Perceptrons): Deep neural networks (DNNs) are composed of multiple layers that perform sequential affine transformations followed by non-linear activations [45]. The training process involves minimizing a loss function through gradient-based optimization. In comparisons, these models are evaluated on the same data splits as supervised ML models, with careful attention to hyperparameter tuning (e.g., learning rate, network architecture) and the use of techniques like cross-validation to mitigate overfitting, especially with smaller sample sizes [38] [46].

Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs): Neural ODEs parameterize the derivative of a system's state using a neural network. The core formulation is:

dz(t)/dt = f(z(t), t, θ)andz(t) = z(t₀) + ∫ f(z(s), s, θ) ds from t₀ to t[44] [47]. The model is trained by solving the ODE using a numerical solver (e.g., Runge-Kutta) and adjusting parametersθto fit the observed data. A key experimental protocol involves testing the model's ability to generalize to unseen initial conditions or parameters without retraining, a task where advanced variants like cd-PINN (continuous dependence-PINN) have shown significant promise [48].

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow and core logical relationships for developing and evaluating the three classes of models, from data input to final prediction.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental findings from recent literature, comparing the performance of different algorithmic families across various tasks and metrics.

Performance in Clinical and Pharmacological Prediction

Table 1: Comparative performance of various ML models in predicting Alzheimer's disease on structured tabular data (OASIS dataset). Adapted from [49].

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (Ensemble) | 96% | 96% | 96% | 96% |

| Support Vector Machine | 96% | 96% | 96% | 96% |

| Logistic Regression (Supervised ML) | 96% | 96% | 96% | 96% |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 94% | 94% | 94% | 94% |

| Adaptive Boosting | 92% | 92% | 92% | 92% |

Table 2: Performance and characteristics of models for predicting firm-level innovation outcomes. Adapted from [46].

| Model | Best ROC-AUC | Key Strengths | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Based Boosting (Ensemble) | Highest | Superior accuracy, precision, F1-score | Medium |

| Support Vector Machine (Supervised ML) | High | Excelled in recall metric | Low-Medium |

| Logistic Regression (Supervised ML) | Weaker | Interpretability, simplicity | Highest |

| Artificial Neural Network (Deep Learning) | Context-dependent | Universal approximator | Low (with small data) |

Table 3: Accuracy of Neural ODE variants in solving the Logistic growth ODE under untrained parameters. Data from [48].

| Model | Context | Relative Error vs. PINN |

|---|---|---|

| Standard PINN | Fixed parameters/initial values | Baseline (10⁻³ to 10⁻⁴) |

| Standard PINN | New parameters/initial values (no fine-tuning) | Significant deviation |

| cd-PINN (Improved Neural ODE) | New parameters/initial values (no fine-tuning) | 1-3 orders of magnitude higher accuracy |

Model Characteristics and Applicability

Table 4: Taxonomy of algorithm families, outlining their core characteristics and trade-offs. Synthesized from [38] [44] [47].

| Aspect | Supervised ML (e.g., Logistic Regression) | Deep Learning (e.g., DNN) | Neural ODEs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Process | Theory-driven; relies on expert knowledge | Data-driven; automatic feature learning | Data-driven; learns continuous dynamics |

| Handling of Nonlinearity | Low; requires manual specification | High; intrinsically captures complex patterns | High; models continuous-time dynamics |

| Interpretability | High (white-box) | Low (black-box) | Medium (mechanistic-inspired) |

| Sample Size Requirement | Low | High (data-hungry) | Varies; can be high for complex systems |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | High (requires ODE solvers) |

| Handling Irregular/ Sparse Time Series | Poor (requires pre-processing) | Moderate (with custom architectures) | Native and robust handling |

| Best-Suited Tasks | Structured tabular data with linear relationships | Complex, high-dimensional data (images, text) | Continuous-time processes, dynamical systems |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following tools and conceptual "reagents" are fundamental for conducting research and experiments in the field of predictive algorithms, particularly when working with Neural ODEs.

- Numerical ODE Solvers: Software packages (e.g., in PyTorch or JAX) that solve initial value problems. They are the computational engine for forward-pass evaluation and gradient calculation via the adjoint sensitivity method in Neural ODEs [50] [47].

- Adjoint Sensitivity Method: A mathematical technique for efficient gradient computation in ODE-defined systems. It allows training of Neural ODEs with constant memory cost in relation to depth, enabling the modeling of deep continuous networks [50] [44].

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN): A framework that integrates the governing equations (physical laws) of a system directly into the loss function of a neural network. This acts as a regularizer, guiding the model to learn solutions that are physically plausible, especially in scenarios with sparse data [48].

- Structured Tabular Datasets (e.g., OASIS, CIS): Curated, domain-specific datasets used as benchmarks for comparing model performance on tasks like disease prediction [49] or innovation outcome forecasting [46]. They are the essential "substrate" for validating supervised ML models.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): A class of deep learning models designed for data structured as graphs. They are often combined with Neural ODEs to model the dynamics of relational systems, such as molecular interactions or particle systems, by learning the interactions between entities [51].

- Equivariant Architectures: Neural network designs that constrain the model to preserve specific symmetries (e.g., rotational or translational invariance). When incorporated into Graph Neural ODEs, they enforce crucial physical inductive biases, leading to more generalizable and physically consistent predictions in n-body systems [51].

Architectural and Data-Flow Diagram of a Neural ODE

The diagram below illustrates the architecture of a Neural ODE model, highlighting how a neural network defines a continuous transformation of the hidden state, contrasting with the discrete layers of a standard Deep Learning network.

The experimental data and comparative analysis lead to several conclusive insights. For prediction tasks on structured, tabular data where relationships are approximately linear and interpretability is paramount, Supervised ML models like Logistic Regression remain competitive and often superior due to their simplicity, stability on smaller samples, and strong performance [38] [49]. The "No Free Lunch" theorem is clearly at play; a study on innovation prediction found that while ensemble methods generally led in ROC-AUC, Logistic Regression was the most computationally efficient, making it a pragmatic choice under resource constraints [46].

Deep Learning excels in handling complex, high-dimensional data and automatically discovering intricate nonlinear interactions. However, this power comes at the cost of requiring large datasets, significant computational resources, and reduced interpretability, making it less suitable for many traditional scientific datasets with limited samples [38].

Neural ODEs represent a paradigm shift for modeling continuous-time and dynamical systems. Their ability to natively handle irregularly sampled data and provide a continuous trajectory offers a unique advantage in domains like pharmacology and molecular dynamics [44] [47]. The choice within this family can be nuanced: for long-term prediction stability and robustness in systems like charged particle dynamics, Neural ODEs (e.g., SEGNO) are preferable. In contrast, Neural Operators (e.g., EGNO) may offer higher short-term accuracy and data efficiency [51].

In conclusion, the "best" algorithm is inherently context-dependent. Researchers must weigh the trade-offs between precision, stability, interpretability, and computational cost against their specific data characteristics and scientific goals. The future lies not in a single dominant algorithm but in purpose-driven selection and the development of hybrid models that leverage the strengths of each paradigm.

The field of pharmacometrics is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). For decades, traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling software like NONMEM (Nonlinear Mixed Effects Modeling) has been the gold standard for population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) analysis, a critical component of model-informed drug development (MIDD) [52] [53]. These traditional methods rely on predefined structural models and statistical assumptions, a process that can be labor-intensive and slow [54].

Recently, AI-based models have emerged as a powerful alternative, promising to enhance predictive performance and computational efficiency by identifying complex patterns in high-dimensional clinical data without heavy reliance on strict mathematical assumptions [55]. This article provides an objective, data-driven comparison between these two paradigms, synthesizing evidence from recent real-world case studies to guide researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies consistently demonstrate that AI/ML models can match or exceed the predictive accuracy of traditional PopPK models across various drug classes. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from two such studies.

Table 1: Comparative Predictive Performance of AI vs. Traditional PopPK Models

| Study & Drug Class | Model Type | Best Performing Model(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs) [55] | Traditional PopPK | Published PopPK models | RMSE: 3.09 (CBZ), 26.04 (PHB), 16.12 (PHE), 25.02 (VPA) μg/mL | AI models showed lower prediction error for 3 out of 4 drugs. |

| AI/ML Models | AdaBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest | RMSE: 2.71 (CBZ), 27.45 (PHB), 4.15 (PHE), 13.68 (VPA) μg/mL | ||

| General PopPK (Simulated & Real Data) [52] | Traditional | NONMEM (NLME) | Assessed via RMSE, MAE, R² on simulated and real-world data from 1,770 patients. | AI/ML models "often outperform NONMEM," with performance varying by model and data. Neural ODEs provided strong performance and explainability. |

| AI/ML Models | 5 ML, 3 DL, and Neural ODE models |

Case Study Insights

- Superior Handling of Complex Relationships: The study on anti-epileptic drugs concluded that ensemble AI methods like AdaBoost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Random Forest leveraged patient-specific electronic medical records to achieve higher predictive accuracy, particularly for drugs with high PK variability like phenytoin and valproic acid [55].

- Performance-Data Relationship: The broader comparative analysis noted that AI model performance varies with data characteristics. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs) were highlighted for delivering strong performance while maintaining a degree of model explainability, especially with large datasets [52].

Experimental Protocols in Reviewed Studies

Protocol 1: Comparative Analysis of NONMEM and AI-based PopPK Prediction

1. Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of AI-based MIDD methods for population PK analysis against traditional NONMEM-based nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) methods [52].

2. Data Sources:

- Simulated Data: Created using a two-compartment model with a known ground truth.

- Real Clinical Data: A large-scale dataset comprising 1,770 patients pooled from multiple clinical trials.

3. AI Models Tested: The study tested a comprehensive suite of nine AI models:

- Five Machine Learning (ML) models

- Three Deep Learning (DL) models

- One Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) model

4. Evaluation Metrics: Predictive performance was quantitatively assessed using root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and the coefficient of determination (R²).

5. Key Workflow Steps: The following diagram illustrates the core comparative workflow of this study.

Protocol 2: Predicting Concentrations of Anti-Epileptic Drugs

1. Objective: To compare the predictive performance of AI models and published PopPK models for therapeutic drug monitoring of four anti-epileptic drugs (carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproic acid) [55].

2. Data Source:

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) records and electronic medical records from Seoul National University Hospital (2010–2021).

- Data included concentration measurements, time since last dose, dosage regimens, demographics, comorbidities, and laboratory results.

3. Data Preprocessing:

- Standardized diagnosis codes (ICD-10).

- Handled missing data using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE).

- Addressed multi-collinearity by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

- Scaled continuous variables using MinMaxScaler.

4. AI Models Tested: Ten different AI models were developed and compared, including:

- Ensemble Methods: Random Forest (RF), Adaboost (ADA), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), Light Gradient Boosting (LGB)

- Neural Networks: Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Other ML models: Lasso and Ridge Regression, Decision Tree

5. Model Training & Evaluation:

- Dataset for each drug was randomly split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio.

- Hyperparameters were tuned to minimize overfitting, selecting those yielding the lowest Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the validation set.

- The final predictive performance of the best AI model for each drug was compared against the performance of its corresponding published PopPK model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Platforms

The experimental workflows rely on a combination of established software, novel computational tools, and specific data processing techniques.

Table 2: Essential Tools for Modern Pharmacokinetic Research

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|