AIC vs BIC: A Researcher's Guide to Optimal Model Selection in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) Information Criterions for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

AIC vs BIC: A Researcher's Guide to Optimal Model Selection in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) Information Criterions for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. It covers the foundational theory behind these probabilistic model selection tools, their practical application in methodologies like ARIMA and machine learning, solutions to common implementation challenges, and a comparative analysis with alternative validation techniques. The content is designed to equip scientists with the knowledge to balance model fit with complexity, ultimately enhancing the reliability of predictive models in pharmaceutical research and clinical applications.

Understanding AIC and BIC: The Statistical Foundations for Scientific Research

The Overfitting Problem in Model Selection

In statistical modeling and machine learning, overfitting occurs when a model corresponds too closely or exactly to a particular dataset, capturing not only the underlying relationship but also the random noise [1]. This "unfortunate property" is particularly associated with maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which will always use additional parameters to improve fit, regardless of whether those parameters capture genuine signals or merely noise [2].

The consequences of overfitting are significant for scientific research. Overfitted models typically exhibit poor generalization performance on unseen data, reduced robustness and portability, and can lead to spurious conclusions through the identification of false treatment effects and inclusion of irrelevant variables [2] [1]. In drug development contexts, this can compromise model reliability for regulatory decision-making [3].

The core of the overfitting problem represents a trade-off between bias and variance [4]. Underfitted models with high bias are too simplistic to capture underlying patterns, while overfitted models with high variance are overly complex and fit to noise. The goal of model selection is to find the optimal balance between these extremes [1] [4].

Penalized Likelihood as a Solution

Penalized likelihood methods directly address overfitting by adding a penalty term to the likelihood function that increases with model complexity [5]. This approach discourages unnecessarily complex models while still rewarding good fit to the data.

The general form of a penalized likelihood function can be represented as:

$$PL(\theta) = \log\mathcal{L}(\theta) - P(\theta)$$

Where $\log\mathcal{L}(\theta)$ is the log-likelihood of the parameters $\theta$ given the data, and $P(\theta)$ is a penalty term that increases with the number or magnitude of parameters.

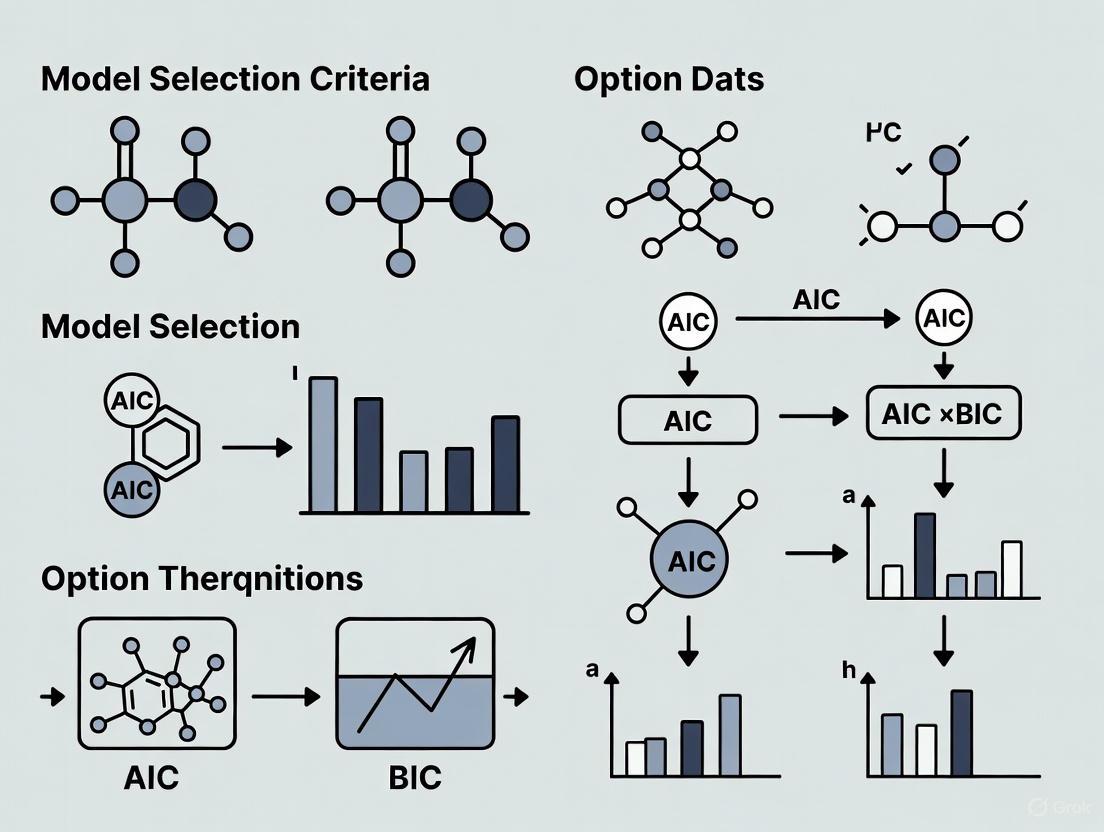

Figure 1: The penalized likelihood workflow incorporates both model fit and complexity penalties to select optimal models.

Comparison of Information Criteria and Penalized Methods

Theoretical Foundations

The most common penalized likelihood approaches include information criteria like AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion), as well as regularization methods like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) [6] [5].

AIC is defined as: $AIC = 2k - 2\ln(\hat{L})$, where $k$ is the number of parameters and $\hat{L}$ is the maximized likelihood value [7]. BIC uses a different penalty: $BIC = k\ln(n) - 2\ln(\hat{L})$, where $n$ is the sample size [8]. The stronger sample size-dependent penalty in BIC typically leads to selection of simpler models compared to AIC [8].

Performance Comparison in Simulation Studies

Comprehensive simulation studies comparing variable selection methods provide quantitative evidence of their relative performance across different scenarios. The table below summarizes key findings from large-scale simulations evaluating correct identification rates (CIR) and false discovery rates (FDR) [6].

Table 1: Performance comparison of variable selection methods in simulation studies

| Method | Search Approach | CIR (Small Model Space) | FDR (Small Model Space) | CIR (Large Model Space) | FDR (Large Model Space) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaustive BIC | Exhaustive | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.15 |

| Stochastic BIC | Stochastic | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.07 |

| Exhaustive AIC | Exhaustive | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.65 | 0.22 |

| Stochastic AIC | Stochastic | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.19 |

| LASSO-CV | Pathwise | 0.70 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.20 |

| Greedy BIC | Stepwise | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.18 |

Simulation conditions varied sample sizes, effect sizes, and correlations among regression variables for both linear and generalized linear models [6]. The results demonstrate that exhaustive search with BIC performs best for small model spaces, while stochastic search with BIC excels for larger model spaces, achieving the highest correct identification rates and lowest false discovery rates [6].

Context-Dependent Performance

The optimal choice between AIC and BIC depends on research goals and assumptions. AIC is designed to select the model that best approximates an unknown reality (aiming for good prediction), while BIC attempts to identify the "true model" from the candidate set [8]. This fundamental difference leads to distinct practical behaviors:

- AIC tends to be less stringent, with penalty $2k$, making it more suitable for prediction-focused applications where some false positives are acceptable [8] [7]

- BIC provides a stronger penalty ($k\ln(n)$) that increases with sample size, making it more conservative and potentially better for explanatory modeling where identifying the true underlying structure is prioritized [6] [8]

Table 2: Characteristics of different penalized likelihood approaches

| Method | Penalty Term | Theoretical Goal | Best Application Context | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | $2k$ | Find best approximating model | Predictive modeling, forecasting | Asymptotically efficient for prediction | Can overfit with many candidates |

| BIC | $k\ln(n)$ | Identify true model | Explanatory modeling, theoretical science | Consistent selection with fixed true model | Misses weak signals in large samples |

| LASSO | $\lambda|\beta|_1$ | Shrinkage and selection | High-dimensional regression | Simultaneous selection and estimation | Biased estimates, random selection |

| SCAD | Complex non-convex | Unbiased sparse estimation | Scientific inference with sparsity | Oracle properties, unbiasedness | Computational complexity |

| NGSM | Adaptive data-driven | Robust sparse estimation | Data with outliers or heavy tails | Robustness and efficiency | Implementation complexity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Simulation Studies in Variable Selection Research

The comprehensive comparison by Xu et al. [6] employed rigorous simulation protocols to evaluate variable selection methods:

Data Generation:

- Linear models: $y = X\beta + \epsilon$ with $\epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2)$

- Generalized linear models: Binary outcomes with logistic link function

- Varied sample sizes ($n$ = 50, 100, 200, 500), effect sizes, and correlation structures among predictors

Evaluation Metrics:

- Correct Identification Rate (CIR): Proportion of true predictors correctly included

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): Proportion of selected predictors that are actually false

- Recall: Sensitivity in identifying true predictors

Implementation:

- Each method was applied to identical simulated datasets

- Performance metrics were averaged across 1000 simulation replications

- Both small ($p$ = 8) and large ($p$ = 30) model spaces were evaluated

Regularization Parameter Selection

For penalized methods requiring tuning parameters (e.g., LASSO, SCAD), selection of regularization parameters is critical. Common approaches include [9] [5]:

- Cross-validation: Minimizing prediction error on held-out data

- Information criteria: Using AIC or BIC to select optimal penalty

- Stability selection: Repeated subsampling to identify stable variables

Recent research has proposed improved metrics like Decorrelated Prediction Error (DPE) for Gaussian processes, which provides more consistent tuning parameter selection than traditional cross-validation metrics, particularly with limited data [9].

Robust Penalized Likelihood Methods

Advanced penalized likelihood approaches address data contamination and non-normal errors. The Nonparametric Gaussian Scale Mixture (NGSM) method models error distributions flexibly without requiring specific distributional assumptions [5]:

Model Structure: $$yi = xi^\top\beta + \epsiloni, \quad \epsiloni \sim N(0, \sigmai^2)$$ $$\sigmai^2 \sim G, \quad G \text{ is unspecified mixing distribution}$$

Estimation:

- Combines expectation-maximization and gradient-based algorithms

- Incorporates nonparametric estimation of error distribution

- Provides robustness to outliers while maintaining efficiency

Simulation studies demonstrate that NGSM methods maintain superior performance compared to traditional robust methods (e.g., Huber loss, LAD-LASSO) when data contains outliers or follows heavy-tailed distributions [5].

Application in Drug Development

Penalized likelihood methods have demonstrated significant utility in pharmaceutical applications, particularly in population pharmacokinetic (popPK) modeling [3]. Automated model selection approaches using penalized likelihood can identify optimal model structures while preventing overparameterization.

Figure 2: Automated popPK model selection workflow incorporating penalized likelihood for pharmaceutical applications.

Implementation in Automated PopPK Modeling

Research by [3] demonstrates successful application of penalized likelihood in automated popPK modeling:

Model Space:

- Over 12,000 unique popPK model structures for extravascular drugs

- Varied compartment structures, absorption mechanisms, error models

Penalty Function:

- AIC component: Penalizes model complexity and overparameterization

- Parameter plausibility: Penalizes abnormal parameter values (high standard errors, unrealistic inter-subject variability)

- Combines statistical fit with domain expertise considerations

Performance:

- Identified model structures comparable to manually developed expert models

- Reduced average development time from weeks to less than 48 hours

- Evaluated fewer than 2.6% of models in search space through efficient optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools for implementing penalized likelihood methods

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Implementation Details | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| pyDarwin | Automated model selection | Bayesian optimization with random forest surrogate + exhaustive local search | PopPK modeling, drug development [3] |

| DiceKriging | Gaussian process modeling | Penalized likelihood estimation for GPs | Computer experiments, simulation modeling [9] |

| NONMEM | Nonlinear mixed effects modeling | Industry standard for popPK analysis | Pharmacometric modeling, drug development [3] |

| SCAD Penalty | Nonconvex penalization | Oracle properties for variable selection | Scientific inference with sparse signals [5] |

| NGSM Distribution | Flexible error specification | Nonparametric Gaussian scale mixture | Robust estimation with outliers [5] |

| Cross-Validation | Tuning parameter selection | K-fold with decorrelated prediction error | General model selection, hyperparameter tuning [9] |

Penalized likelihood methods provide a principled approach to navigating the bias-variance tradeoff inherent in statistical modeling. The comparative evidence demonstrates that:

- BIC-based methods generally outperform AIC and LASSO in both correct identification rates and false discovery rates, particularly when combined with exhaustive or stochastic search strategies [6]

- Method performance is context-dependent - exhaustive search BIC excels for small model spaces, while stochastic search BIC performs better for large model spaces [6]

- Advanced penalized methods (NGSM, SCAD) offer robust performance for data with outliers or complex error structures [5]

- Automated implementations in drug development demonstrate real-world efficacy, significantly reducing model development time while maintaining quality [3]

The choice of penalized likelihood approach should be guided by research objectives, dataset characteristics, and theoretical considerations about the underlying truth. For predictive modeling where no true model is assumed to exist in the candidate set, AIC may be preferred, while for explanatory modeling with belief in a true parsimonious underlying model, BIC provides superior performance [8].

In statistical modeling and machine learning, a fundamental challenge is selecting the best model from a set of candidates. Overfitting—where a model learns the noise in the data rather than the underlying signal—is a constant risk. Information criteria provide a principled framework for model selection by balancing goodness-of-fit against model complexity [7] [10]. Among these, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are two of the most widely used measures. While often mentioned together, they are founded on different philosophies and are designed to achieve different goals. This guide provides an objective comparison of these criteria, with a focus on AIC's primary objective: optimizing a model's predictive accuracy [7].

The core trade-off that AIC and BIC address is universal: a model must be complex enough to capture the essential patterns in the data, yet simple enough to avoid fitting spurious noise. AIC approaches this problem from an information-theoretic perspective, seeking the model that best approximates the true, unknown data-generating process, with the goal of making the most accurate predictions for new data [7] [8]. In contrast, BIC is derived from a Bayesian perspective and is often interpreted as a tool for identifying the "true" model, assuming it exists within the set of candidates [11] [8].

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulae

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)

AIC is founded on information theory, specifically the concept of Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which measures the information lost when a candidate model is used to approximate reality [7]. AIC does not assume that the true model is among the candidates being considered [8]. Its formula is:

AIC = 2k - 2ln(L̂) [7]

Where:

- k: Number of estimated parameters in the model.

- L̂: Maximized value of the likelihood function of the model.

The model with the minimum AIC value is preferred. The term -2ln(L̂) rewards better goodness-of-fit, while the 2k term penalizes model complexity, acting as a safeguard against overfitting [7].

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

BIC, also known as the Schwarz Information Criterion, is derived from an asymptotic approximation of the logarithm of the Bayes factor [11] [8]. Its formula is:

BIC = -2ln(L̂) + k ln(N) [11]

Where:

- k: Number of parameters.

- L̂: Maximized value of the likelihood.

- N: Sample size.

Like AIC, the model with the minimum BIC is preferred. The critical difference lies in the penalty term: BIC's k ln(N) penalty depends on sample size, making it more stringent than AIC's 2k penalty for larger datasets (typically when N ≥ 8) [11] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the goals, theoretical foundations, and penalties of AIC and BIC.

Figure 1: Theoretical and goal-oriented differences between AIC and BIC.

A Direct Comparison: AIC vs. BIC

The choice between AIC and BIC is not a matter of one being universally superior; rather, it depends on the analyst's goal. The following table summarizes their key differences.

Table 1: A direct comparison of AIC and BIC characteristics.

| Aspect | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Select the model with the best predictive accuracy for new data [8]. | Select the true model, assuming it exists in the candidate set [8]. |

| Theoretical Basis | Information theory (minimizing expected Kullback-Leibler divergence) [7] [8]. | Bayesian probability (asymptotic approximation of the Bayes factor) [11] [8]. |

| Penalty for Complexity | 2k (linear in parameters, independent of N) [7]. |

k ln(N) (increases with sample size) [11]. |

| Asymptotic Behavior | Not consistent; may overfit as N → ∞ by selecting overly complex models [8]. | Consistent; probability of selecting true model → 1 as N → ∞ [8]. |

| Sample Size Dependence | Independent of sample size (N) in the penalty term. | Dependent on sample size (N); penalty grows with N. |

| Implicit Assumptions | Reality is complex and not exactly described by any candidate model [8]. | The true model is among the candidate models being considered [8]. |

Experimental Performance and Empirical Data

Simulation studies across various fields provide concrete evidence of how these criteria perform in practice.

Simulation Protocol: Linear Model Comparison

A common experimental design to test AIC and BIC involves generating data from a known model and seeing which criterion more frequently selects the correct model in a controlled setting [6] [11].

- Data Generation: Data is simulated from a known linear model, often referred to as the "true" or "generating" model.

- Candidate Models: A set of candidate models is fitted to the simulated data. This set typically includes the true model, simpler models (underfitting), and more complex models (overfitting).

- Criterion Calculation: AIC and BIC are calculated for each candidate model.

- Model Selection: The model minimizing each criterion is selected.

- Replication: This process is repeated thousands of times to compute the frequency with which AIC and BIC correctly identify the generating model.

Key Findings from Comparative Studies

- Variable Selection in Linear Models: A comprehensive simulation comparing variable selection methods found that BIC-based searches (exhaustive and stochastic) resulted in the highest correct identification rate (CIR) and the lowest false discovery rate (FDR). This indicates a stronger performance for BIC in identifying the exact set of true predictor variables, especially in larger model spaces [6].

- Ecological Model Selection: A review of model selection tools in ecology found that maximum likelihood criteria (AIC) consistently favored simpler population models when compared to Bayesian criteria (BIC, DIC, Bayes Factors) in simulations of population abundance trajectories [11].

- Neuroimaging and Dynamic Causal Modeling: A study comparing AIC, BIC, and the variational Free Energy in the context of brain connectivity models found that the Free Energy had the best model selection ability. It was noted that the complexity of a model is not usefully characterized by the number of parameters alone, which is a key assumption in both AIC and BIC [12].

Table 2: Summary of experimental performance results from various fields.

| Field / Study | AIC Performance | BIC Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Selection [6] | Lower Correct Identification Rate (CIR) | Higher Correct Identification Rate (CIR) | Linear and Generalized Linear Models |

| Ecology [11] | Favored simpler models | Favored more complex models | Simulated population abundance trajectories |

| Pharmacokinetics [13] | Applied for selecting number of exponential terms | Compared against AIC and F-test | Evaluating linear pharmacokinetic equations for drugs |

Practical Applications and Use Cases

The theoretical and empirical differences translate into specific recommendations for application.

When to Prefer AIC

AIC is the preferred tool when the primary goal is prediction. Its focus on finding the best approximating model makes it ideal for [7] [8]:

- Forecasting: Building models to predict future outcomes, where the true data-generating process is acknowledged to be complex and unknown.

- Exploratory Research: In early stages of investigation where the goal is to identify promising predictors without a strong assumption that a simple "true" model exists.

When to Prefer BIC

BIC is more suitable when the goal is explanatory modeling or theory testing. Its tendency to select simpler models and its consistency property are advantageous when [11] [8]:

- Identifying a Data-Generating Mechanism: There is a strong theoretical belief that a relatively simple true model exists within the set of candidates.

- Hypothesis Testing: Comparing specific, theoretically-motivated models where the number of parameters is not the sole focus.

A Unified Workflow and the Scientist's Toolkit

In practice, many analysts use both criteria. The following workflow is often recommended:

- Define a set of candidate models based on domain knowledge.

- Fit all models to the data.

- Calculate both AIC and BIC for each model.

- If both criteria agree, there is strong evidence for the selected model.

- If they disagree, report the results of both. The disagreement itself is informative: AIC may be suggesting a model with better predictive power, while BIC may be advocating for a more parsimonious explanation. The final decision should then be guided by the primary research goal [8].

Table 3: Essential "research reagents" for implementing AIC and BIC in practice.

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Provides functions to compute AIC and BIC automatically from fitted model objects. | Essential for all applications. |

| Likelihood Function | The core component from which AIC/BIC are calculated; measures model fit. | Must be specified correctly for the model family (e.g., Normal, Binomial). |

| Set of Candidate Models | A pre-defined collection of models representing different hypotheses. | The quality of the selection is bounded by the candidate set. |

| Model Averaging | A technique that combines predictions from multiple models, weighted by their AIC or BIC scores. | Useful when no single model is clearly superior; improves prediction robustness [7]. |

AIC and BIC are foundational tools for model selection, yet they serve different masters. AIC's goal is predictive accuracy. It seeks the model that will perform best on new, unseen data, openly acknowledging that all models are approximations. BIC's goal is to identify the true model, operating under the assumption that a simple reality exists within the set of candidates. Empirical studies consistently show that BIC has a higher probability of selecting the true model in controlled simulations, while AIC is designed to be more robust in the realistic scenario where the truth is complex and unknown.

Therefore, the choice is not about which criterion is better in a vacuum, but which one is better suited to the specific research objective. For prediction, AIC is the recommended guide. For explanation and theory testing, BIC often provides a more stringent and consistent standard. The most robust practice is to use them in concert, letting their agreement—or thoughtful interpretation of their disagreement—guide the path to a well-justified model.

Model selection represents a fundamental challenge in statistical science, particularly in fields like drug development and computational biology where identifying the correct data-generating mechanism is paramount. Within this landscape, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) has emerged as a prominent tool specifically designed for identifying the "true" model under certain conditions. Developed by Gideon Schwarz in 1978, BIC offers a large-sample approximation to the Bayes factor, enabling statisticians to select among a finite set of competing models by balancing model fit with complexity [14]. Unlike its main competitor, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), which prioritizes predictive accuracy, BIC applies a more substantial penalty for model complexity, making it theoretically consistent—meaning that as sample size increases, the probability of selecting the true model (if it exists among the candidates) approaches 1 [15] [16].

The mathematical foundation of BIC rests on Bayesian principles, deriving from an approximation of the model evidence (marginal likelihood) through Laplace's method [14] [17]. This theoretical underpinning distinguishes it from information-theoretic approaches and positions it as a natural choice for researchers whose primary goal is model identification rather than prediction. In practical terms, BIC helps investigators avoid overfitting by penalizing the inclusion of unnecessary parameters, thus steering them toward more parsimonious models that likely capture the essential underlying processes [18].

Mathematical Foundation and Theoretical Framework

Core Formulation and Derivation

The BIC is formally defined by the equation:

BIC = -2ln(L) + kln(n)

Where:

- L represents the maximized value of the likelihood function for the estimated model

- k denotes the number of free parameters to be estimated

- n signifies the sample size [14] [17]

The first component (-2ln(L)) serves as a measure of model fit, decreasing as the model's ability to explain the data improves. The second component (kln(n)) acts as a complexity penalty, increasing with both the number of parameters and the sample size. This penalty term is crucial—it grows with sample size, ensuring that as more data becomes available, the criterion becomes increasingly selective against unnecessarily complex models [14].

The derivation of BIC begins with Bayesian model evidence, integrating out model parameters using Laplace's method to approximate the marginal likelihood of the data given the model [14] [17]. Through a second-order Taylor expansion around the maximum likelihood estimate and assuming large sample sizes, the approximation simplifies to the familiar BIC formula, with constant terms omitted as they become negligible in model comparisons [14].

BIC in Relation to Bayes Factors

A key advantage of BIC emerges when comparing two models, where the difference in their BIC values approximates twice the logarithm of the Bayes factor [19]. This connection to Bayesian hypothesis testing provides a coherent framework for interpreting the strength of evidence for one model over another. The following diagram illustrates this theoretical relationship and the derivation pathway:

Comparative Analysis: BIC Versus AIC

Philosophical Differences and Penalty Structures

The fundamental distinction between BIC and AIC stems from their differing objectives: BIC aims to identify the true model (assuming it exists in the candidate set), while AIC seeks to maximize predictive accuracy [15] [16]. This philosophical divergence manifests mathematically in their penalty terms for model complexity. Although both criteria follow the general form of -2ln(L) + penalty(k, n), they employ different penalty weights:

- BIC penalty: kln(n)

- AIC penalty: 2k

For sample sizes larger than 7 (when ln(n) > 2), BIC imposes a stronger penalty for each additional parameter, making it more conservative and predisposed to selecting simpler models [14] [16]. This difference in penalty structure means that BIC favors more parsimonious models, particularly as sample size increases, while AIC allows greater complexity to potentially enhance predictive performance.

Practical Implications for Model Selection

The choice between BIC and AIC has tangible consequences in practical research scenarios. A comprehensive simulation study comparing variable selection methods demonstrated that BIC-based approaches generally achieved higher correct identification rates (CIR) and lower false discovery rates (FDR) compared to AIC-based methods, particularly when the true model was among those considered [6]. This aligns with BIC's consistency property and makes it particularly valuable in scientific contexts where identifying the correct explanatory variables is crucial for theoretical understanding.

The table below summarizes the key differences between BIC and AIC:

Table 1: Comparison of BIC and AIC Characteristics

| Characteristic | BIC | AIC |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify true model | Maximize predictive accuracy |

| Penalty Term | kln(n) | 2k |

| Theoretical Basis | Bayesian approximation | Information-theoretic |

| Model Consistency | Yes (as n→∞) | No |

| Typical Error倾向 | Underfitting | Overfitting |

| Sample Size Sensitivity | Higher penalty with larger n | Constant penalty per parameter |

Performance Evaluation and Experimental Evidence

Simulation Studies in Variable Selection

Empirical evaluations through simulation studies provide crucial insights into BIC's performance relative to alternative selection criteria. A comprehensive comparison of variable selection methods examined BIC and AIC across various model search approaches (exhaustive, greedy, LASSO path, and stochastic search) in both linear and generalized linear models [6]. The researchers explored a wide range of realistic scenarios, varying sample sizes, effect sizes, and correlations among regression variables.

The results demonstrated that exhaustive search with BIC and stochastic search with BIC outperformed other method combinations across different performance metrics. Specifically, on small model spaces, exhaustive search with BIC achieved the highest correct identification rate, while on larger model spaces, stochastic search with BIC excelled [6]. These approaches resulted in superior balance between identifying true predictors (recall) and minimizing false inclusions (false discovery rate), supporting efforts to enhance research replicability.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The simulation studies revealed distinct performance patterns between BIC and AIC across various experimental conditions:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of BIC vs. AIC in Simulation Studies

| Experimental Condition | Criterion | Correct Identification Rate | False Discovery Rate | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Model Spaces | BIC | Higher | Lower | When identification of true predictors is priority |

| Large Model Spaces | BIC | Higher | Lower | High-dimensional settings with stochastic search |

| Predictive Focus | AIC | Lower | Higher | When forecasting accuracy is primary goal |

| Large Sample Sizes | BIC | Significantly Higher | Significantly Lower | n > 100 with true model in candidate set |

| Small Sample Sizes | AIC | Comparable or Slightly Lower | Higher | n < 50 when true model uncertain |

The experimental protocol for these simulations typically involved: (1) generating data with known underlying models, (2) applying different selection criteria across various search methods, (3) calculating performance metrics including correct identification rate, recall, and false discovery rate, and (4) repeating the process across multiple parameter configurations to ensure robustness [6].

Interpretation Guidelines and Decision Framework

Rules of Evidence for BIC Differences

When comparing models using BIC, the magnitude of difference between models provides valuable information about the strength of evidence. The following guidelines, proposed by Raftery (1995), offer a framework for interpreting BIC differences:

- Difference of 0-2: Weak evidence for the model with lower BIC

- Difference of 2-6: Positive evidence

- Difference of 6-10: Strong evidence

- Difference > 10: Very strong evidence [19]

These thresholds correspond approximately to Bayes factor interpretations, with a difference of 2 representing positive evidence (Bayes factor of about 3), and a difference of 10 representing very strong evidence (Bayes factor of about 150) [19]. This quantitative framework helps researchers move beyond simple binary model selection toward graded interpretations of evidence.

Strategic Decision Framework for Model Selection

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for researchers deciding between BIC and AIC based on their specific analytical goals and contextual factors:

Applications in Scientific Research and Drug Development

Specific Use Cases in Pharmaceutical Research

BIC finds numerous applications throughout drug development and biomedical research:

Clinical Trial Design and Analysis: BIC helps identify the most relevant patient covariates and treatment effect modifiers in randomized controlled trials, leading to more precise subgroup analyses and tailored therapeutic recommendations [16].

Genomic and Biomarker Studies: In high-dimensional genomic data analysis, BIC assists in selecting the most informative biomarkers from thousands of candidates, effectively balancing biological relevance with statistical reliability [6] [16].

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling: When comparing different compartmental models for drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, BIC provides an objective criterion for selecting the most appropriate model structure without overparameterization [18].

Dose-Response Modeling: BIC helps determine the optimal complexity of dose-response relationships, distinguishing between linear, sigmoidal, and more complex response patterns based on experimental data.

Research Toolkit for BIC Implementation

Successful application of BIC in research requires both statistical software and conceptual understanding:

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for BIC Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in BIC Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (AIC(), BIC() functions), Python (statsmodels), Stata (estat ic) |

Computes BIC values for fitted models |

| Model Search Algorithms | Exhaustive search, Stepwise selection, Stochastic search | Explores candidate model space efficiently |

| Specialized Packages | statsmodels (Python), lmSupport (R), REGISTER (SAS) |

Implements BIC-based model comparison |

| Visualization Tools | BIC profile plots, Model selection curves | Displays BIC values across candidate models |

| Benchmark Datasets | Iris data, Simulated data with known structure | Validates BIC performance in controlled scenarios |

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Theoretical Constraints and Practical Challenges

Despite its theoretical advantages for identifying true models, BIC comes with important limitations that researchers must acknowledge:

Large Sample Assumption: BIC's derivation relies on large-sample approximations, and its performance may deteriorate with small sample sizes where the Laplace approximation becomes less accurate [14] [17].

True Model Assumption: BIC operates under the assumption that the true model exists within the candidate set, a condition that rarely holds in practice with complex biological systems [17].

High-Dimensional Challenges: In variable selection problems with numerous potential predictors, BIC cannot efficiently handle complex collections of models without complementary search algorithms [14] [6].

Over-Penalization Risk: The strong penalty term may lead BIC to exclude weakly influential but scientifically relevant variables, particularly in studies with large sample sizes [16] [17].

Complementary Approaches and Hybrid Strategies

Sophisticated research practice often combines BIC with other methodological approaches to mitigate its limitations:

Multi-Model Inference: Rather than selecting a single "best" model, researchers can use BIC differences to calculate model weights and implement model averaging, acknowledging inherent model uncertainty [15].

Complementary Criteria: Using BIC alongside other criteria (AIC, cross-validation) provides a more comprehensive view of model performance, particularly when different criteria converge on the same model [15].

Bayesian Alternatives: For complex models with random effects or latent variables, fully Bayesian approaches with Bayes factors or Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) may offer more appropriate solutions despite computational challenges [18].

The Bayesian Information Criterion remains a powerful tool for researchers prioritizing the identification of true data-generating mechanisms, particularly in scientific domains like drug development where theoretical understanding is as important as predictive accuracy. Its strong penalty for complexity, foundation in Bayesian principles, and consistency properties make it uniquely suited for distinguishing substantively meaningful signals from statistical noise.

Nevertheless, the judicious application of BIC requires awareness of its limitations and appropriate contextualization within broader analytical strategies. By combining BIC with complementary criteria, robust model search algorithms, and domain expertise, researchers can leverage its strengths while mitigating its weaknesses. As methodological research advances, BIC continues to evolve within an expanding toolkit for statistical model selection, maintaining its specialized role in the ongoing pursuit of scientific truth.

In statistical modeling, particularly in fields like pharmacology and ecology, researchers are often faced with the challenge of selecting the best model from a set of candidates. A model that is too simple may fail to capture important patterns in the data (underfitting), while an overly complex model may fit the noise rather than the signal (overfitting). To address this trade-off, information criteria provide a framework for model comparison by balancing goodness-of-fit with model complexity [7] [14].

Two of the most widely used criteria are the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Despite their similar appearance in formula structure, they are founded on different theoretical principles and are designed for different goals. This guide provides an objective comparison of AIC and BIC, detailing their formulas, performance, and appropriate applications, with a special focus on use cases relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Formulas and Theoretical Foundations

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is an estimator of prediction error and thereby the relative quality of statistical models for a given dataset [7]. Its goal is to find the model that best explains the data with minimal information loss, making it particularly suited for predictive accuracy [20].

- Core Formula:

AIC = -2 * ln(L) + 2kL: The maximum value of the likelihood function for the model.k: The number of estimated parameters in the model.

- Theoretical Basis: AIC is founded on information theory. It estimates the relative amount of information lost when a given model is used to represent the process that generated the data. The model that minimizes this information loss is considered the best [7].

- Small Sample Correction: For small sample sizes relative to the number of parameters (n/k < 40), a corrected version, AICc, is recommended [20] [21]:

AICc = AIC + (2k(k+1))/(n-k-1)

The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), also known as the Schwarz Information Criterion, is a criterion for model selection among a finite set of models [14]. It aims to identify the true model, assuming it exists among the candidates, and thus emphasizes model parsimony [20].

- Core Formula:

BIC = -2 * ln(L) + k * ln(n)L: The maximum value of the likelihood function for the model.k: The number of parameters in the model.n: The number of data points.

- Theoretical Basis: BIC is derived as an approximation to the Bayesian model evidence (marginal likelihood) using Laplace's method [14] [22] [17]. It is closely related to Bayes factors and can be interpreted under certain conditions to provide posterior model probabilities [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and theoretical pathways that lead to the development of AIC and BIC, highlighting their distinct philosophical starting points.

Direct Comparison: AIC vs. BIC

Penalty Term Analysis and Model Selection倾向

The key difference between AIC and BIC lies in their penalty terms for model complexity. This difference in penalty structure leads to distinct selection behaviors, which can be framed in terms of sensitivity (AIC) and specificity (BIC) [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Penalty Terms and Selection倾向

| Feature | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|

| Full Formula | -2ln(L) + 2k |

-2ln(L) + k * ln(n) |

| Penty Term | 2k |

k * ln(n) |

| Sample Size (n) Effect | Penalty is independent of n |

Penalty increases with ln(n) |

| Philosophical Goal | Predictive accuracy, minimizing information loss | Identification of the "true" model |

| Typical Selection倾向 | Tends to favor more complex models | Tends to favor simpler models |

| Analogy to Testing | Higher sensitivity, lower specificity [16] | Lower sensitivity, higher specificity [16] |

| Sample Size Crossover | Penalty is 2k for all n |

Penalty is larger than AIC when n ≥ 8 [11] |

Performance in Simulation Studies

Experimental data from various simulation studies help quantify the performance differences between AIC and BIC.

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Performance from Simulation Studies

| Study Context | AIC Performance | BIC Performance | Key Findings and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetic Modeling [23] | Minimal mean AICc corresponded best with predictive performance. | Not the primary focus; AICc recommended. | AIC (corrected for small samples) is effective for minimizing prediction error in complex biological data where a "true model" may not exist. |

| Dynamic Causal Modelling (DCMs) [12] | Outperformed by the Free Energy criterion. | Outperformed by the Free Energy criterion. | In complex Bayesian model comparisons (e.g., for fMRI), both AIC and BIC were surpassed by a more sophisticated Bayesian measure. |

| Iris Data Clustering [16] | Correctly selected the 3-class model matching the three species. | Selected an underfitting 2-class model, lumping two species together. | An example of BIC's higher specificity leading to underfitting when the true structure is more complex. |

| General Model Selection [16] [11] | More likely to overfit, especially with large n. |

More likely to underfit, especially with small n (<7). |

The relative performance is context-dependent. BIC is consistent (finds the true model with infinite data) if the true model is candidate; AIC is efficient for prediction [11]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Pharmacokinetic Simulation

To illustrate how these criteria are evaluated, we detail a key experiment from the search results that assessed AIC's performance in a mixed-effects modeling context, common in drug development [23].

- 1. Research Objective: To evaluate whether minimal mean AIC corresponds to the best predictive performance in a population (mixed-effects) pharmacokinetic model.

- 2. Data Simulation:

- A hypothetical pharmacokinetic profile was generated using the function

y(t) = 1/t, which resembles a drug concentration-time curve [23]. - This was approximated by a sum of

Mexponentials withKnon-zero coefficients. - Population data for

Nindividuals were simulated using:y_i(t_j) = [1/t_j] * (exp(η_i) + ε_ij), whereη_irepresents interindividual variability (varianceω²) andε_ijrepresents measurement noise (varianceσ²) [23].

- A hypothetical pharmacokinetic profile was generated using the function

- 3. Model Fitting:

- A set of pre-specified models with different numbers of exponential terms (

K) were fitted to the simulated data. - For data with

ω² > 0, nonlinear mixed-effects modeling was performed using NONMEM software [23].

- A set of pre-specified models with different numbers of exponential terms (

- 4. Calculation of Criteria:

- AIC and the small-sample corrected AICc were calculated for each fitted model [23].

- 5. Validation:

- The predictive performance of each model was quantified on a simulated validation dataset using the Mean Square Prediction Error (MSPE), adjusted for interindividual variability [23].

- 6. Analysis:

- The means of the AIC and AICc values across multiple simulation runs were compared to the mean predictive performance.

- Result: Mean AICc corresponded very well, and better than mean AIC, with the mean predictive performance, confirming its utility for selecting models with the best predictive power in this context [23].

Practical Application and Workflow

Decision Framework for Researchers

The choice between AIC and BIC depends on the goal of the statistical modeling exercise. The following workflow provides a practical guide for researchers and scientists.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Model Selection Studies

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Provides environments for fitting models, calculating likelihoods, and computing AIC/BIC values. | General model fitting and comparison for any statistical analysis. |

| Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Modeling Tool (NONMEM) | Software designed for population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and simulation. | Used in the featured pharmacokinetic simulation to fit models to population data [23]. |

Time Series Package (e.g., statsmodels) |

Contains specialized functions for fitting models like ARIMA and calculating information criteria. | Used to determine the optimal lag length in autoregressive models via BIC [17]. |

| Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) Clustering | An algorithm that models data as a mixture of Gaussian distributions; BIC/AIC can determine the optimal number of clusters. | Used to find the correct number of subpopulations (clusters) in data, such as in the Iris dataset [17] [16]. |

| Likelihood Function | The core component computed during model fitting, representing the probability of the data given the model parameters. The value of L in the AIC/BIC formulas. |

Fundamental to all maximum likelihood estimation and subsequent model comparison. |

AIC and BIC are foundational tools for model selection, each with distinct strengths derived from their theoretical foundations. AIC, with its lighter penalty 2k, is optimized for predictive accuracy and is less concerned with identifying a "true" model. In contrast, BIC, with its sample-size-dependent penalty k*ln(n), is designed for model identification and favors parsimony, especially with larger datasets.

For researchers in drug development and other applied sciences, the choice is not about which criterion is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the task at hand. If the goal is robust prediction, as is often the case in prognostic model building or dose-response forecasting, AIC (or AICc for small samples) is the recommended tool. If the goal is to identify the most plausible data-generating mechanism from a set of theoretical candidates, BIC may be preferable. In practice, reporting results from both criteria provides a more comprehensive view of model uncertainty and robustness.

In statistical modeling, a fundamental challenge is selecting the best model from a set of candidates. The core dilemma involves balancing model fit (how well a model explains the observed data) against model complexity (the number of parameters required for the explanation). Overly simple models may miss important patterns (underfitting), while overly complex models may capture noise as if it were signal (overfitting) [15] [24]. Information criteria provide a quantitative framework to navigate this trade-off, with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) standing as two of the most prominent methods [15] [25]. These criteria are indispensable across numerous fields, including econometrics, molecular phylogenetics, spatial analysis, and drug development, where they guide researchers toward models with optimal predictive accuracy or theoretical plausibility [15] [26] [27].

The evaluation of any model involves two competing aspects: the goodness-of-fit and model parsimony. While goodness-of-fit, often measured by the log-likelihood, generally improves with additional parameters, parsimony demands explaining the data with as few parameters as possible [15] [7]. AIC and BIC resolve this tension by introducing penalty terms for complexity, creating a single score that allows for direct comparison between models of differing structures [15] [24]. Understanding their formulation, differences, and appropriate application contexts is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in empirical analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of AIC and BIC

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)

Developed by Hirotugu Akaike, the AIC is an estimator of prediction error rooted in information theory [7]. Its core purpose is to estimate the relative information lost when a candidate model is used to represent the true data-generating process. The model that minimizes this information loss is considered optimal [7]. The AIC formula is:

In this equation, L represents the maximum value of the likelihood function for the model, and k is the number of estimated parameters [15] [7]. The term -2ln(L) decreases as the model's fit improves, rewarding better fit. Conversely, the term 2k increases with the number of parameters, penalizing complexity. The model with the lowest AIC value is preferred [15] [25] [7]. AIC is particularly favored when the primary goal is predictive accuracy, as it tends to favor more flexible models that may better capture underlying patterns in new data [15] [25].

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

Also known as the Schwarz Information Criterion, the BIC originates from a Bayesian probability framework [14]. Its objective is different from AIC's: BIC aims to identify the true model from a set of candidates, under the assumption that the true model is among those considered [28] [14]. The formula for BIC is:

BIC = ln(n)k - 2ln(L) [15] [14]

Here, n denotes the sample size, k is the number of parameters, and L is the model's likelihood [15] [14]. The critical difference from AIC lies in the penalty term ln(n)k. Because ln(n) is greater than 2 for any sample size larger than 7, BIC penalizes complexity more heavily than AIC in most practical situations [14] [29]. This stronger penalty encourages the selection of simpler models, a property known as parsimony [15] [25]. BIC is often the preferred choice when the research goal is explanatory, focusing on identifying the correct data-generating process rather than mere forecasting [15] [25].

Conceptual Workflow of Model Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical process a researcher follows when using AIC and BIC for model selection, highlighting the key decision points.

Comparative Analysis: AIC versus BIC

Key Differences in Formulation and Philosophy

The divergence between AIC and BIC stems from their foundational philosophies and mathematical structures. AIC is designed for predictive performance, seeking to approximate the model that will perform best on new, unseen data. It is derived from an estimate of the Kullback-Leibler divergence, a measure of information loss [26] [7]. In contrast, BIC is derived from Bayesian model probability and aims to select the model with the highest posterior probability, effectively trying to identify the "true" model if it exists within the candidate set [28] [14]. This fundamental difference in objective explains their differing penalties for model complexity.

The penalty term is the primary mathematical differentiator. AIC’s penalty of 2k is constant relative to sample size, while BIC’s penalty of ln(n)k grows with the number of observations [15] [14] [29]. This has a critical implication: as sample size increases, BIC's preference for simpler models becomes more pronounced. For small sample sizes (n < 7), the two criteria may behave similarly, but for the large-sample studies common in modern research, BIC will typically select more parsimonious models than AIC [29].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between AIC and BIC

| Feature | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Predictive accuracy | Identify the "true" model |

| Theoretical Foundation | Information Theory (Kullback-Leibler divergence) | Bayesian Probability (Marginal Likelihood) |

| Penalty Term | 2k |

ln(n)k |

| Sample Size Effect | Penalty is independent of sample size | Penalty increases with sample size |

| Model Consistency | Not consistent - may not select true model as n→∞ | Consistent - selects true model if present as n→∞ |

| Typical Application | Forecasting, time series analysis, machine learning | Theoretical model identification, scientific inference |

Performance Under Different Experimental Conditions

Empirical studies across various domains reveal how AIC and BIC perform under different conditions. In phylogenetics, research has shown that under non-standard conditions (e.g., when some evolutionary edges have small expected changes), AIC tends to prefer more complex mixture models, while BIC prefers simpler ones. The models selected by AIC performed better at estimating edge lengths, whereas models selected by BIC were superior for estimating base frequencies and substitution rate parameters [26].

In spatial econometrics, a Monte Carlo simulation study investigated the performance of AIC and BIC for selecting the correct spatial model among alternatives like the Spatial Lag Model (SLM) and Spatial Error Model (SEM). The results demonstrated that under ideal conditions, both criteria can effectively assist analysts in selecting the true spatial econometric model and properly detecting spatial dependence, sometimes outperforming traditional Lagrange Multiplier (LM) tests [27].

When considering model misspecification (where the "true" model is not in the candidate set), AIC generally outperforms BIC. This is because AIC is not attempting to find a nonexistent true model but rather the best approximating model for prediction [28]. This robustness to misspecification makes AIC particularly valuable in exploratory research phases or in fields where the underlying processes are not fully understood.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of AIC and BIC Across Domains

| Research Domain | Experimental Setup | AIC Performance | BIC Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Phylogenetics [26] | Comparison of partition vs. mixture models with genomic data | Preferred complex mixture models; better branch length estimation | Preferred simpler models; better parameter estimation | Performance trade-off depends on estimation goal |

| Spatial Econometrics [27] | Monte Carlo simulation with spatial dependence | Effective at detecting spatial dependence and selecting true model | Effective at model selection, sometimes better than LM tests | Both criteria reliable under ideal conditions |

| Genetic Epidemiology [30] | Marker selection for discriminant analysis | Selected 25-26 markers providing best fit to data | Selected different marker set than single-locus lod scores | Both useful for model comparison with different parameters |

| General Model Selection [29] | Simulated data with known generating process | Correctly identified true predictors but included spurious ones | Selected more parsimonious model with fewer false positives | BIC's stronger penalty reduced overfitting |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Implementation Workflow

Implementing AIC and BIC for model selection follows a systematic protocol. The first step involves specifying candidate models based on theoretical knowledge and research questions. For instance, in time series analysis, this might involve ARIMA models with different combinations of autoregressive (p) and moving average (q) parameters [25]. In genetic studies, it may involve models with different sets of markers as inputs [30]. The crucial requirement is that all models must be fit to the identical dataset to ensure comparability.

The next step is model fitting via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The likelihood function L must be maximized for each candidate model, and the maximum likelihood value L^ recorded along with the number of parameters k and sample size n [24] [7] [14]. Most statistical software (R, Python, Stata) automates the calculation of AIC and BIC once models are fit [15]. For example, in R, the commands AIC(model) and BIC(model) return the respective values after fitting a model [15].

The final stage involves comparison and selection. Researchers calculate AIC and BIC for all models and rank them from lowest to highest [7]. The model with the lowest value is considered optimal for that criterion. It is also valuable to compute the relative likelihood or probability for each model. For AIC, the quantity exp((AIC_min - AIC_i)/2) provides the relative probability that model i minimizes information loss [7].

Protocol for Spatial Econometric Model Selection

A specific experimental protocol from spatial econometrics illustrates a comprehensive application. This Monte Carlo study aimed to evaluate AIC and BIC for selecting spatial models like the Spatial Lag Model (SLM) and Spatial Error Model (SEM) [27].

- Data Generation: Simulate datasets with known spatial dependencies using different spatial weights matrices (e.g., rook and queen contiguity) and a real geographical structure (Greece's spatial layout) to test robustness [27].

- Model Specification: Define multiple candidate spatial econometric models, including the Spatial Independent Model (SIM), SLM, SEM, and more complex extensions like the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), SARAR, and SDEM [27].

- Model Fitting: Estimate each candidate model using maximum likelihood methods for each simulated dataset.

- Criterion Calculation: Compute AIC and BIC for every fitted model. The formulas applied were the standard ones:

AIC = 2k - 2ln(L)andBIC = ln(n)k - 2ln(L)[27]. - Performance Evaluation: Assess how frequently each criterion selects the data-generating model (the "true" model). Compare the performance of AIC and BIC against traditional spatial dependence tests like Lagrange Multiplier tests [27].

This protocol can be adapted to other domains by modifying the data generation process and the family of candidate models, providing a robust framework for comparing the performance of information criteria.

Research Reagent Solutions for Model Selection Experiments

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing AIC/BIC Model Selection

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Model Selection Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (AIC(), BIC() functions), Python (statsmodels), Stata (estat ic) [15] |

Provides computational environment for model fitting and criterion calculation |

| Model Families | ARIMA (time series), GLM (regression), Mixed Models, Spatial Econometric Models [15] [25] [27] | Defines the set of candidate models to be evaluated and compared |

| Data Simulation Tools | Custom Monte Carlo scripts, Synthetic data generators [27] | Creates controlled datasets with known properties to validate selection criteria |

| Visualization Packages | ggplot2 (R), matplotlib (Python) | Creates plots for comparing criterion values across models and diagnostic checks |

| Specialized Packages | IQ-TREE2 (phylogenetics), spdep (spatial statistics) [26] |

Domain-specific implementation of complex models and selection criteria |

Practical Applications and Decision Guidelines

Field-Specific Applications

The application of AIC and BIC spans numerous scientific disciplines, each with particular considerations. In econometrics and time series forecasting, AIC is often preferred for optimizing forecasting models such as ARIMA, GARCH, or VAR, where predictive accuracy is paramount [15] [25]. For instance, when determining the appropriate parameters (p,d,q) for an ARIMA model, analysts typically fit multiple combinations and select the one with the lowest AIC, as it tends to produce better forecasts [25].

In phylogenetics and molecular evolution, both criteria are extensively used to select between partition and mixture models of sequence evolution. Recent research suggests caution, as AIC may underestimate the expected Kullback-Leibler divergence under nonstandard conditions and prefer overly complex mixture models [26]. The choice between AIC and BIC here depends on whether the goal is accurate estimation of evolutionary relationships (potentially favoring AIC) or identification of the correct evolutionary process (potentially favoring BIC) [26].

In genetic epidemiology and drug development, these criteria help in feature selection, such as identifying genetic markers associated with diseases. For example, one study applied AIC and BIC stepwise selection to asthma data, identifying a group of markers that provided the best fit, which differed from those with the highest single-locus lod scores [30]. This demonstrates how information criteria can reveal multivariate relationships that simpler methods might miss.

Strategic Selection Guide

The choice between AIC and BIC should be intentional, based on research goals and data context. The following decision diagram outlines a systematic approach for researchers.

Limitations and Complementary Methods

While AIC and BIC are powerful tools, they are not universal solutions. Both assume that models are correctly specified and can be sensitive to issues like missing data, multicollinearity, and non-normal errors [15]. They also do not replace theoretical understanding or robustness checks [15]. Importantly, AIC and BIC provide only relative measures of model quality; a model with the lowest AIC in a set may still be poor in absolute terms if all candidates fit inadequately [7].

When AIC and BIC disagree, it often reflects their different philosophical foundations. Such disagreement should prompt researchers to consider the underlying reasons—perhaps the sample size is large enough for BIC's penalty to dominate, or maybe the true model is not in the candidate set [28]. In these situations, domain knowledge becomes crucial for making the final decision [15].

Several alternative methods can complement information criteria. Cross-validation provides a direct estimate of predictive performance without relying on asymptotic approximations and is particularly useful when the sample size is small [24]. The Hannan-Quinn Criterion (HQC) offers an intermediate penalty between AIC and BIC [15]. In Bayesian statistics, Bayes factors provide a more direct approach to model comparison, though with higher computational costs [14]. For complex or high-dimensional data, penalized likelihood methods like LASSO and Ridge regression combine shrinkage with model selection [15] [24].

The fundamental trade-off between model fit and complexity lies at the heart of statistical modeling. AIC and BIC provide mathematically rigorous yet practical frameworks for navigating this trade-off, each with distinct strengths and philosophical underpinnings. AIC prioritizes predictive accuracy and is more robust when the true model is not among the candidates, making it ideal for forecasting and exploratory research. BIC emphasizes theoretical parsimony and consistently identifies the true model when it exists in the candidate set, making it valuable for explanatory modeling and confirmatory research.

The experimental evidence demonstrates that neither criterion is universally superior; their performance depends on the research context, sample size, and modeling objectives. In practice, calculating both AIC and BIC provides complementary insights, with any disagreement between them offering valuable information about the model space. Ultimately, these information criteria are most powerful when combined with diagnostic techniques, robustness checks, and substantive domain knowledge, forming part of a comprehensive approach to statistical modeling and scientific discovery.

In the pursuit of scientific discovery, particularly in fields such as drug development and biomedical research, statistical models serve as essential tools for understanding complex relationships in data. Model selection criteria provide objective metrics to navigate the critical trade-off between a model's complexity and its goodness-of-fit to the observed data. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are two widely used measures for this purpose [7] [31]. Both criteria are founded on the principle of parsimony, guiding researchers toward models that explain the data well without unnecessary complexity [31].

The core principle unifying AIC and BIC is that a lower score indicates a better model. This is because these criteria quantify the relative amount of information lost when a model is used to represent the underlying process that generated the data [7]. A model that loses less information is considered higher quality. This score is calculated by balancing the model's fit against its complexity; the fit is rewarded, while complexity is penalized [31]. The ensuing sections will delve into the theoretical foundations of AIC and BIC, illustrate their application through experimental data, and provide practical guidance for their use in research.

Theoretical Foundations of AIC and BIC

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)

The AIC was developed by Hirotugu Akaike and is derived from information theory [32]. Its goal is to select a model that has strong predictive accuracy, meaning it will perform well with new, unseen data [8] [15]. It achieves this by being asymptotically efficient; as the sample size grows, AIC is designed to select the model that minimizes the mean squared error of prediction [31] [33]. The formula for AIC is:

AIC = 2k - 2ln(L) [7] [15] [31]

In this equation:

krepresents the number of estimated parameters in the model.Lis the maximum value of the likelihood function for the model.-2ln(L)represents the lack of fit or deviance; a better fit results in a higher likelihood and a smaller value for this term.2kis the penalty term for the number of parameters, discouraging overfitting [7].

The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)

The BIC, also known as the Schwarz Bayesian Criterion, originates from a Bayesian perspective [32]. Its objective is different from AIC's: BIC aims to identify the "true model" from a set of candidates, assuming that the true data-generating process is among the models being considered [8]. It is a consistent criterion, meaning that as the sample size approaches infinity, the probability that BIC selects the true model converges to 1 [31] [33]. The formula for BIC is:

BIC = ln(n)k - 2ln(L) [15] [31] [32]

In this equation:

nis the sample size.kis the number of parameters.Lis the model's likelihood.ln(n)kis the penalty term for model complexity.

A key difference is that BIC's penalty term includes the sample size n, making it more stringent than AIC's penalty, especially with large datasets [31]. This stronger penalty leads BIC to favor simpler models than AIC [15] [31].

Visualizing the Model Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of using AIC and BIC for model selection, from candidate model formulation to final model interpretation.

A Comparative Analysis of AIC and BIC

Core Differences and When to Use Each Criterion

The choice between AIC and BIC is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather depends on the researcher's goal [8] [15].

- Use AIC when the primary objective is predictive accuracy. AIC is optimal for finding the model that will make the most accurate predictions on new data, even if it is not the simplest model [15] [33]. It is well-suited for forecasting applications, such as predicting patient response to a drug or forecasting disease progression.

- Use BIC when the goal is to identify the true underlying data-generating process, assuming it is among the candidate models. BIC is preferred for explanatory modeling and theory testing, where parsimony and identifying the correct explanatory variables are paramount [8] [15] [33].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between AIC and BIC

| Feature | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Predictive accuracy [8] [15] | Identification of the "true" model [8] [15] |

| Theoretical Basis | Information Theory (Kullback-Leibler divergence) [7] | Bayesian Probability [32] |

| Penalty Term | 2k [7] |

ln(n) * k [15] |

| Sample Size | Does not depend directly on n [8] |

Penalty increases with ln(n) [31] |

| Asymptotic Property | Efficient [33] | Consistent [31] [33] |

| Tendency | Prefers more complex models [8] [31] | Prefers simpler models, especially with large n [15] [31] |

Interpreting the Magnitude of Differences

The absolute value of AIC or BIC is not interpretable; only the differences between models matter. A common approach is to compute the difference between each model's criterion score and the minimum score among the set of candidate models (ΔAIC or ΔBIC) [7]. Guidelines for interpreting these differences are provided in the table below.

Table 2: Guidelines for Interpreting Differences in AIC and BIC Values

| ΔAIC or ΔBIC | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|

| 0 - 2 | Substantial/Weak evidence [31] |

| 2 - 6 | Moderate evidence [31] |

| 6 - 10 | Strong evidence [31] [32] |

| > 10 | Very strong evidence [31] [32] |

For AIC, it is also possible to compute relative likelihoods or weights to quantify the probability that a given model is the best among the candidates [7].

Experimental Protocols and Empirical Evidence

Simulation Study on Variable Selection Performance

To objectively compare the performance of AIC and BIC, researchers conduct comprehensive simulation studies. These studies explore a wide range of conditions, such as varying sample sizes, effect sizes, and correlations among variables, for both linear and generalized linear models [6]. The goal is to evaluate how well each criterion identifies the correct set of variables associated with the outcome.

4.1.1 Key Experimental Protocol

A typical simulation protocol involves the following steps [6]:

- Data Generation: Data is simulated from a known model, which is designated as the "true model." This model contains a specific set of relevant variables.

- Model Search and Evaluation: Different variable selection methods are applied to the simulated data. This includes combining search algorithms (e.g., exhaustive, stochastic, LASSO path) with evaluation criteria (AIC and BIC).

- Performance Calculation: The selected models are compared against the true model using specific performance metrics calculated over many simulation runs.

4.1.2 Standard Performance Metrics

The following metrics are commonly used to evaluate performance [6]:

- Correct Identification Rate (CIR): The proportion of simulations where the exact true model is identified.

- Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of true relevant variables that are correctly included in the selected model.

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): The proportion of selected variables that are, in fact, irrelevant.

4.1.3 Illustrative Experimental Data

Simulation results show that the performance of AIC and BIC is highly dependent on the context, such as the size of the model space and the search algorithm used.

Table 3: Summary of Simulation Results from [6]

| Experimental Condition | Best Performing Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Small Model Space (Small number of potential predictors) | Exhaustive Search with BIC [6] | Achieved the highest Correct Identification Rate (CIR) and lowest False Discovery Rate (FDR). |

| Large Model Space (Larger number of potential predictors) | Stochastic Search with BIC [6] | Outperformed other methods, resulting in the highest CIR and lowest FDR. |

| General Trend | - | BIC-based methods generally led to higher CIR and lower FDR compared to AIC-based methods, which may help increase research replicability [6]. |

These findings highlight that BIC tends to be more successful at correctly identifying the true model without including spurious variables, while AIC has a higher tendency to include irrelevant variables (overfit) in an effort to maximize predictive power [6] [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Model Selection

Successfully implementing a model selection study requires a suite of statistical and computational tools. The table below details essential "research reagents" for this process.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Model Selection Studies

| Tool Category | Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python (statsmodels), Stata, SAS [15] | Provides the computational environment to fit models and calculate AIC/BIC values. R has built-in AIC() and BIC() functions. |

| Search Algorithms | Exhaustive Search, Greedy Search (e.g., Stepwise), Stochastic Search, LASSO path [6] | Methods to efficiently or comprehensively explore the space of possible models, especially when the number of predictors is large. |

| Performance Metrics | Correct Identification Rate (CIR), Recall, False Discovery Rate (FDR) [6] | Quantitative measures used in simulation studies to objectively evaluate and compare the performance of different selection criteria. |

| Model Validation Techniques | Residual Analysis, Specification Tests, Predictive Cross-Validation [15] | Used to check the absolute quality of a model selected via AIC/BIC, ensuring residuals are random and predictions are robust. |

AIC and BIC are foundational tools for model selection, both adhering to the principle that a lower score indicates a better model by balancing fit and complexity. AIC is geared toward finding the model with the best predictive accuracy, while BIC is designed to identify the true data-generating model, favoring greater parsimony [8] [15]. Empirical evidence from simulation studies confirms that BIC typically achieves a higher rate of correct model identification with a lower false discovery rate, whereas AIC may include more variables to minimize prediction error [6].

For researchers in drug development and other scientific fields, the choice between these criteria should be guided by the research question. If the goal is prediction, AIC is often more appropriate. If the goal is explanatory theory testing and identifying the correct underlying mechanism, BIC is generally preferred. Ultimately, AIC and BIC are powerful aids to, not replacements for, scientific judgment and should be used in conjunction with domain knowledge, model diagnostics, and validation techniques [15] [31].

Implementing AIC and BIC in Biomedical Research and Pharmacometric Modeling

In statistical modeling and machine learning, model selection is a fundamental process for identifying the most appropriate model among a set of candidates that best describes the underlying data without overfitting. Two of the most widely used criteria for this purpose are the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). These metrics are particularly valuable in research fields like pharmaceutical development, where they help build parsimonious models that predict drug efficacy, patient outcomes, or biological pathways while balancing complexity and interpretability.

Both AIC and BIC evaluate model quality based on goodness-of-fit while imposing a penalty for model complexity. The general concept is to reward models that achieve high explanatory power with fewer parameters, thus guarding against overfitting. The mathematical foundations of these criteria stem from information theory and Bayesian probability, providing a robust framework for comparative model assessment. Researchers across disciplines rely on these tools for tasks ranging from variable selection in regression models to comparing mixed-effects models and time-series forecasts.

The core formulas for AIC and BIC are:

- AIC = -2log(L) + 2p

- BIC = -2log(L) + p⋅log(n)

where L represents the model's likelihood, p denotes the number of parameters, and n is the sample size. Lower values for both metrics indicate better model balance between fit and complexity. Although both criteria follow the same general principle, BIC typically imposes a stronger penalty for additional parameters, especially with larger sample sizes, often leading to selection of more parsimonious models.

Theoretical Foundations of AIC and BIC

Mathematical Formulations