Benchmark Problems for Computational Model Verification: Ensuring Reliability in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and applying benchmark problems to verify computational models in biomedical research.

Benchmark Problems for Computational Model Verification: Ensuring Reliability in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for developing and applying benchmark problems to verify computational models in biomedical research. It covers foundational principles of verification and validation (V&V), establishes methodological workflows for creating effective benchmarks, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents rigorous protocols for validation and comparative analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide aims to enhance model credibility, facilitate regulatory acceptance, and accelerate the translation of in silico findings into clinical applications.

Core Principles of Model Verification: Building a Foundation for Trustworthy Computational Science

In computational science and engineering, the phrases "solving the equations right" and "solving the right equations" encapsulate the fundamental distinction between verification and validation (V&V). This distinction forms the cornerstone of credible computational simulations across diverse fields, from aerospace engineering to drug development. Verification is a primarily mathematical exercise dealing with the correctness of the solution to a given computational model, while validation assesses the physical accuracy of the computational model itself by comparing its results with experimental reality [1] [2] [3]. As computational models become increasingly integral to decision-making in high-consequence systems, a rigorous understanding and application of V&V processes, supported by standardized benchmark problems, is paramount for establishing confidence in simulation results [3].

Core Concepts and Definitions

The following table summarizes the definitive characteristics of verification and validation, highlighting their distinct objectives and questions.

Table 1: Fundamental Definitions of Verification and Validation

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | "Are we solving the equations correctly?" | "Are we solving the right equations?" |

| Primary Objective | Assess numerical accuracy and software correctness [2] [3]. | Assess physical modeling accuracy by comparing with experimental data [2] [3]. |

| Nature of Process | Mathematics-focused; a check on programming and computation [1]. | Physics-focused; a check on the science of the model [1]. |

| Key Activities | - Code Verification (checking for bugs, consistency of discretization) [2]- Solution Verification (estimating numerical uncertainty) [2] | Quantifying modeling errors through comparison with high-quality experimental data [2]. |

| Relationship to Reality | Not an issue; deals with the computational model in isolation [3]. | The central issue; deals with the relationship between computation and the real world [3]. |

V&V Frameworks Across Disciplines

The principles of V&V are universally critical, but their implementation varies to meet the specific needs and risks of different fields. The table below compares how V&V is applied in several high-stakes disciplines.

Table 2: Application of V&V Across Different Fields

| Field | Verification Emphasis | Validation Emphasis | Key Standards & Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | Code and solution verification to quantify numerical errors in strongly coupled non-linear PDEs [1] [2]. | Comparison with experimental data for flows with shocks, boundary layers, and turbulence [1] [3]. | AIAA guidelines; ASME V&V 20; focus on aerodynamic simulation credibility [1]. |

| Medical Device Development | Software verification per IEEE 1012 and FDA guidance to ensure algorithm correctness [4] [5]. | Analytical and clinical validation to assess physiological accuracy and clinical utility [4] [5]. | ASME V&V 40 standard; risk-informed credibility framework based on Context of Use (COU) [4]. |

| Biometric Monitoring Tech (BioMeTs) | Verification of hardware and sample-level sensor outputs (in silico/in vitro) [5]. | Analytical validation of data processing algorithms and clinical validation in target patient populations [5]. | V3 Framework: Verification, Analytical Validation, Clinical Validation [5]. |

| Software Verification | Formal proof of correctness against a specification (e.g., using Dafny, Lean) [6]. | Witness validation and testing against benchmarks (e.g., SV-COMP) [7]. | Competition benchmarks (e.g., SV-COMP) to compare verifier performance on standardized tasks [7]. |

| Nuclear Reactor Safety | Use of manufactured and analytical solutions for code verification [3]. | International Standard Problems (ISPs) for validation against near-safety-critical experiments [3]. | Focus on high-consequence systems where full-scale testing is impossible [3]. |

The Risk-Informed Framework in Medical Technology

The ASME V&V 40 standard for medical devices introduces a sophisticated, risk-informed credibility framework. The process begins by defining the Context of Use (COU), which precisely specifies the role and scope of the computational model in addressing a specific question about device safety or efficacy [4]. The required level of V&V evidence is then determined by a risk analysis, which considers the model's influence on the decision and the consequence of an incorrect decision [4]. This ensures that the rigor of the V&V effort is commensurate with the potential impact on patient health and safety.

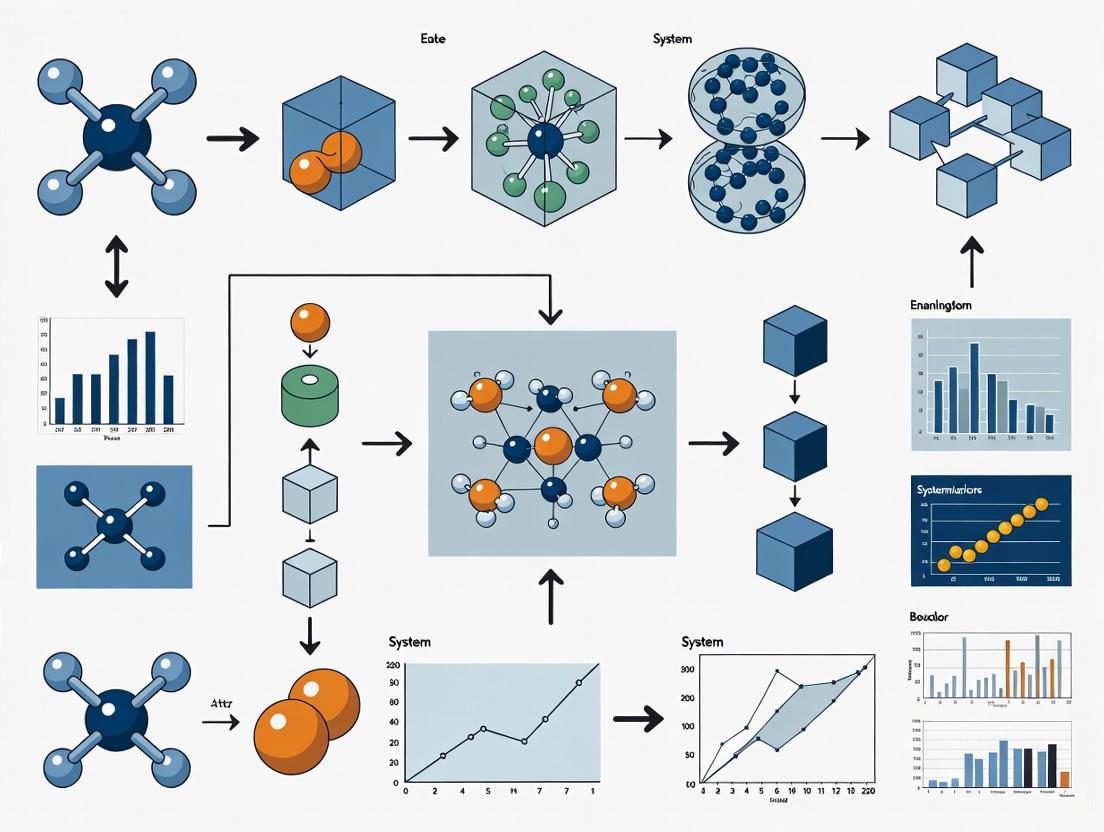

Diagram 1: The ASME V&V 40 Credibility Assessment Process

Benchmark Problems in Verification Research

Benchmarks are the essential tools for conducting rigorous V&V. They provide standardized test cases to measure, compare, and improve the performance of computational models and software.

Types of Verification Benchmarks

Verification benchmarks are designed to have known solutions, allowing for the precise quantification of numerical error. The main types include:

- Manufactured Analytical Solutions (MMS): A chosen solution is substituted into the governing PDEs, which then define the source terms and boundary conditions. The code is then run to see if it can recover the chosen solution [3].

- Classical Analytical Solutions: These are exact solutions to simplified versions of the PDEs (e.g., Couette flow, Poiseuille flow in CFD) and provide a fundamental check on the code [3].

- Highly Accurate Numerical Solutions: Solutions obtained from well-verified codes with extremely fine grids or high-order methods serve as a reference "truth" for more complex problems [3].

The Vericoding Benchmark: A New Frontier

A recent advancement in software verification is the development of large-scale benchmarks for vericoding—the AI-driven generation of formally verified code from formal specifications. The table below summarizes quantitative results from a major benchmark study, demonstrating the current capabilities of off-the-shelf Large Language Models (LLMs) in this domain [6].

Table 3: Vericoding Benchmark Results Across Programming Languages (n=12,504 specifications)

| Language / System | Benchmark Size | Reported LLM Success Rate | System Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dafny | 3,029 tasks | 82% | Automated Theorem Prover (SMT-based) |

| Verus/Rust | 2,334 tasks | 44% | Automated Theorem Prover (SMT-based) |

| Lean | 7,141 tasks | 27% | Interactive Theorem Prover (Tactic-based) |

This benchmark highlights that performance varies significantly by the underlying verification system, with higher success rates observed for automated provers like Dafny compared to interactive systems like Lean [6]. The study also found that adding natural-language descriptions to the formal specifications did not significantly improve performance, underscoring the unique nature of the vericoding task [6].

Experimental Protocols for V&V

A rigorous V&V process relies on well-defined experimental and computational protocols.

Protocol for a Verification Assessment (Grid Convergence Study)

A standard method for solution verification in computational physics is the grid convergence study, which quantifies the numerical uncertainty arising from the discretization of the spatial domain [1].

- Problem Definition: Select a benchmark case with a known exact solution or a key Quantity of Interest (QoI) like pressure recovery [1] [3].

- Grid Generation: Create a sequence of at least three systematically refined computational grids. The refinement ratio should be constant and greater than 1.1 [1].

- Solution Execution: Run the simulation on each grid level to compute the QoI.

- Error Calculation & Order of Accuracy: For cases with a known exact solution, calculate the error for each grid. The observed order of accuracy of the method should match the theoretical order [3].

- Uncertainty Estimation: For cases without a known solution, use techniques like Richardson Extrapolation to estimate the numerical error on the finest grid and the value of the QoI in the limit of zero grid spacing [1].

Protocol for a Validation Assessment

Validation assesses the modeling error by comparing computational results with experimental data [2].

- Context of Use & Validation Metric: Define the purpose of the model and select a quantitative metric (e.g., a norm of the difference) to compare computational and experimental results [4] [3].

- Experimental Data Acquisition: Conduct a carefully designed experiment, estimating the uncertainty in both input and output measurements. It is critical to report the conditions realized in the experiment, not just those desired [3].

- Computational Simulation: Run the simulation using the experimentally measured inputs and boundary conditions.

- Comparison and Validation Metric Evaluation: Compare the computational and experimental outcomes using the pre-defined validation metric.

- Credibility Assessment: Judge the model's adequacy for the COU by evaluating whether the difference between the computational results and experimental data, considering both numerical and experimental uncertainties, falls within an acceptable tolerance defined during the risk analysis [4].

Diagram 2: Workflow for a Model Validation Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential resources and tools used in computational model verification research.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Verification & Validation Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Example Benchmarks / Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Manufactured Solution | A pre-defined solution used to verify a code's ability to solve the governing equations correctly by generating corresponding source terms [3]. | NAFEMS benchmarks; Code verification tests in ANSYS, ABAQUS [3]. |

| Grid Convergence Benchmark | A test case to evaluate how the numerical solution changes with spatial or temporal resolution, quantifying discretization error [1]. | Standardized CFD problems (e.g., flow over a bump); SV-COMP verification tasks [1] [7]. |

| Formal Verification Benchmark | A suite of programs with formal specifications to test the ability of verifiers or AI models to generate correct code and proofs [6]. | DafnyBench (782 tasks), CLEVER (161 Lean tasks), SV-COMP (33,353+ C/Java tasks) [7] [6]. |

| International Standard Problem (ISP) | A validation benchmark where multiple organizations simulate the same carefully characterized experiment, allowing for comparative assessment [3]. | Nuclear reactor safety experiments coordinated by OECD/NEA [3]. |

| Verification Tool (SMT Solver) | An automated engine that checks the logical validity of verification conditions generated from code and specifications [6]. | Used within Dafny and Verus/Verus to discharge proof obligations [6]. |

| Interactive Theorem Prover | A software tool for constructing complex mathematical proofs in a step-by-step, machine-checked manner [6]. | Lean, Isabelle, Coq; used in vericoding and mathematical theorem proving [6]. |

The disciplined separation of "solving the equations right" (verification) from "solving the right equations" (validation) is fundamental to credible computational science. This distinction, supported by rigorous benchmarks and standardized protocols, enables researchers and drug development professionals to properly quantify and communicate the limitations and predictive capabilities of their models. As computational methods continue to advance and permeate high-consequence decision-making, the adherence to robust V&V practices will remain the foundation for building justified confidence in simulation results.

The Critical Role of Benchmark Problems in Establishing Model Credibility

In computational science, the predictive power of a model is only as strong as the evidence backing it. Benchmark problems serve as the foundational evidence, providing standardized tests that allow researchers to verify, validate, and compare computational models objectively. These benchmarks are indispensable for transforming speculative models into trusted tools for critical decision-making, especially in fields like drug development where outcomes have significant consequences. The process separates scientific rigor from marketing claims, ensuring that reported advancements reflect genuine capability improvements rather than optimized performance on narrow tasks [8] [9]. This article explores the indispensable role of benchmarking through examples across computational disciplines, provides methodologies for rigorous implementation, and visualizes the processes that establish true model credibility.

The Benchmarking Imperative: From Code Verification to AI Evaluation

Core Functions of Benchmark Problems

Benchmark problems provide multiple, interconnected functions that collectively establish model credibility:

Verification: Benchmarks determine whether a computational model correctly implements its intended algorithms. For example, in Particle-in-Cell and Direct Simulation Monte Carlo (PIC-DSMC) codes, verification involves testing individual algorithms against analytic solutions on simple geometries before progressing to coupled systems [10].

Validation: This process assesses how well a model represents real-world phenomena. The ASME V&V 30 Subcommittee, for instance, develops benchmark problems that compare computational results against high-quality experimental data with precisely characterized measurement uncertainties [11].

Performance Comparison: Benchmarks enable objective comparisons between different methodologies, algorithms, or systems using standardized metrics and conditions [12]. This function is crucial for identifying optimal approaches for specific applications.

Identification of Limitations: Well-designed benchmarks reveal the boundaries of a model's capabilities and accuracy. As noted in PIC-DSMC research, benchmarks help "identify and understand issues and discrepancies" that might not be apparent when modeling complex real-world objects [13] [10].

The Consequences of Inadequate Benchmarking

The absence of rigorous benchmarking practices can lead to overstated capabilities and undetected flaws. Recent research from the Oxford Internet Institute found that only 16% of 445 large language model (LLM) benchmarks used rigorous scientific methods to compare model performance [9]. Approximately half of these benchmarks attempted to measure abstract qualities like "reasoning" or "harmlessness" without providing clear definitions or measurement methodologies. This lack of rigor enables "benchmark gaming," where model makers can optimize for specific tests without achieving genuine improvements in capability [9]. Such practices have real-world consequences, as demonstrated by the 2024 CrowdStrike outage that disrupted 8.5 million devices globally [6].

Benchmarking in Action: Cross-Domain Applications

Computational Fluid Dynamics and Thermal Fluids

The ASME V&V 30 Subcommittee has established a series of benchmark problems for verifying and validating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models in nuclear system thermal fluids behavior. Their second benchmark problem focuses on single-jet experiments at different Reynolds numbers, providing:

- Experimental data sets obtained using scaled-down facilities with measurement uncertainties estimated using ASME PTC 19.1 Test Uncertainty standards [11]

- Stepwise, progressive approaches that focus on each key ingredient individually [11]

- Protocols that encourage participants to apply whatever V&V practices they would normally use in regulatory submissions [11]

This approach demonstrates how benchmarking can be integrated into a regulatory framework to establish credibility for safety-critical applications.

Formal Software Verification

In formal software verification, the "vericoding" benchmark represents a significant advancement. Unlike "vibe coding" (which generates potentially buggy code from natural language descriptions), vericoding involves LLM-generation of formally verified code from formal specifications [6]. Recent benchmarks contain 12,504 formal specifications across multiple verification languages (Dafny, Verus/Rust, and Lean), providing a comprehensive testbed for verification tools. The quantitative results from this benchmark are presented in the table below.

Table 1: Performance of Off-the-Shelf LLMs on Vericoding Benchmarks

| Language | Benchmark Size | Success Rate | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dafny | 3,029 specifications | 82% | Uses SMT solvers to automatically discharge verification conditions |

| Verus/Rust | 2,334 specifications | 44% | |

| Lean | 7,141 specifications | 27% | Uses tactics to build proofs interactively |

The data reveals significant variation in success rates across languages, with Dafny demonstrating notably higher performance. Interestingly, adding natural-language descriptions did not significantly improve performance, suggesting that formal specifications alone provide sufficient context for code generation [6].

Neural Network Verification

The International Verification of Neural Networks Competition (VNN-COMP) represents a coordinated effort to develop benchmarks for neural network verification. This initiative:

- Brings together researchers interested in formal methods and tools providing guarantees about neural network behaviors [14]

- Categorizes benchmarks based on system expressiveness and problem formulation [14]

- Includes categories for different network types (feedforward vs. recurrent) and supported layers/activations [14]

- Aims to standardize benchmarks, model formats, and property specifications to enable meaningful comparisons [14]

This organized approach addresses the critical need for verification in safety-critical applications like autonomous driving and medical systems.

Computational Electromagnetics

In computational electromagnetics (CEM), simple geometric shapes like spheres serve as effective validation tools. As researchers from Riverside Research noted, "using spheres for CEM validation provides a range of challenges and broadly meaningful results" because complications that arise "can be representative of issues that occur when modeling more complex objects" while being easier to identify and understand [13].

Methodological Framework: Designing Effective Benchmarking Studies

The Benchmark Development Process

The creation of effective benchmarks follows a systematic methodology that can be visualized as a workflow with feedback mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Benchmark development and refinement cycle.

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of benchmark development, where results from initial implementations inform refinements to improve the benchmark's quality and effectiveness.

Statistical Rigor in Benchmark Comparisons

When comparing model performance using benchmarks, appropriate statistical methods are essential. For algorithm comparisons in optimization, researchers should consider:

- Non-parametric tests: These do not assume normal distributions or homogeneity of variance, making them suitable for computational performance data [15].

- Paired designs: Measurements from different algorithms applied to the same problem instances are not independent and should be treated as paired data [15].

- One-sided tests: When the goal is to demonstrate that one algorithm is superior to another (rather than simply different) [15].

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test often represents a suitable choice as it considers both the direction and magnitude of differences, unlike the sign test which only considers direction [15]. Performance profiles offer an alternative visualization approach that displays the entire distribution of performance ratios across multiple problem instances [15].

Database Benchmarking Best Practices

For database benchmarking, Aerospike researchers recommend specific practices to ensure meaningful results:

Table 2: Recommended Practices for Database Benchmarking

| Recommended Practices | Practices to Avoid |

|---|---|

| Non-trivial dataset sizes (1TB+) | Short duration tests |

| Non-trivial number of objects (20M-1B+) | Small, predictable datasets in DRAM/cache |

| Realistic, distributed object sizes | Non-replicated datasets |

| Latency measurement under load | Lack of mixed read/write loads |

| Multi-node cluster testing | Single node tests |

| Node failure/consistency testing | Narrow, unique-feature benchmarks |

| Scale-out by adding nodes | |

| Appropriate read/write workload mix |

These practices emphasize realistic conditions that reflect production environments rather than optimized laboratory scenarios [8].

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Benchmarking

PIC-DSMC Code Verification Protocol

The verification of Particle-in-Cell and Direct Simulation Monte Carlo codes follows a hierarchical approach that systematically tests individual components before integrated systems [10]:

Unit Testing: Verify the three core algorithms (particle pushing, Monte Carlo collision handling, and field solving) individually using analytic solutions on simple geometries.

Coupled System Testing: Test interactions between coupled components, such as between electrostatic field solutions and particle-pushing in non-collisional PIC.

Integrated Testing: Evaluate complete system performance on complex benchmark problems like capacitive radio frequency discharges with comparisons to established codes and analytical solutions where available.

This incremental approach isolates potential error sources and provides comprehensive evidence of code correctness [10].

Benchmark Implementation Workflow

The execution of benchmark studies follows a structured workflow that can be visualized as a sequential process with critical decision points.

Diagram 2: Benchmark implementation and execution workflow.

This workflow highlights the critical decision point in hardware configuration, where researchers must choose between identical setups for direct comparison or optimized configurations that reflect realistic deployment scenarios [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Benchmarking

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|

| SPECint Benchmarks | Measures integer processing performance of CPU and memory subsystems | Computer system performance evaluation [12] |

| YCSB (Yahoo! Cloud Serving Benchmark) | Evaluates database performance under different workload patterns | NoSQL and relational database systems [8] |

| Vericoding Benchmark Suite | Tests formally verified code generation from specifications | AI-based program synthesis and verification [6] |

| VNN-LIB | Standardized format for neural network verification problems | Neural network formal verification [14] |

| Performance Profilers (gprof, Intel VTune) | Identify computational bottlenecks and resource utilization patterns | Software performance optimization [12] |

| CoreMark | Evaluates core-centric low-level algorithm performance | Embedded processor comparison [12] |

These tools provide the foundational infrastructure for conducting reproducible benchmarking studies across computational domains.

Benchmark problems serve as the bedrock of credibility for computational models across scientific disciplines. From verifying safety-critical CFD simulations to validating increasingly sophisticated AI systems, standardized, well-designed benchmarks provide the evidentiary foundation that separates genuine capability from optimized performance on narrow tasks. As computational models grow more complex and are deployed in higher-stakes environments like drug development, the role of benchmarks becomes increasingly crucial. The methodologies, protocols, and resources outlined in this article provide researchers with the framework needed to implement rigorous benchmarking practices that yield trustworthy, reproducible results—the essential prerequisites for scientific progress and responsible innovation.

In computational model verification research, distinguishing between different types of errors is fundamental for assessing model credibility and reliability. Numerical errors arise from the computational methods used to solve model equations, while modeling errors stem from inaccuracies in the model's theoretical formulation or its parameters when representing real-world phenomena [16] [4]. This distinction is critically important across scientific disciplines, from systems biology to engineering, as it determines the appropriate strategies for model improvement and validation. The process of evaluating uncertainty associated with measurement results, known as uncertainty analysis or error analysis, provides a structured framework for quantifying these discrepancies and establishing confidence in computational predictions [16].

The regulatory landscape for computational models, particularly in biomedical fields, emphasizes the necessity of this distinction. Agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have established frameworks for assessing the credibility of computational models used in medical device submissions, requiring rigorous verification and validation activities that separately address numerical and modeling aspects [17] [4]. Similarly, in drug development, computational models for evaluating drug combinations must undergo thorough credibility assessment to ensure reliable predictions [18]. Understanding the sources and magnitudes of different error types enables researchers to determine whether a model is "fit-for-purpose" for specific regulatory decisions.

Fundamental Error Categories

Computational errors can be systematically categorized based on their origin, behavior, and methods for quantification. The most fundamental distinction lies between accuracy, which refers to the closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true or accepted value, and precision, which describes the degree of consistency and agreement among independent measurements of the same quantity [16]. This dichotomy directly relates to systematic errors (affecting accuracy) and random errors (affecting precision), which exhibit fundamentally different characteristics and require different mitigation approaches.

Systematic errors are reproducible inaccuracies that consistently push results in the same direction. These errors cannot be reduced by simply increasing the number of observations and often require calibration against known standards or fundamental model adjustments for correction [16]. In contrast, random errors represent statistical fluctuations in measured data due to precision limitations of measurement devices or environmental factors. These can be evaluated through statistical analysis and reduced by averaging over multiple observations [16]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these primary error categories.

Table 1: Fundamental Categories of Measurement Errors

| Error Category | Definition | Sources | Reduction Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Errors | Reproducible inaccuracies consistently in the same direction | Instrument calibration errors, incomplete model definitions, environmental factors | Calibration against standards, model refinement, accounting for confounding factors |

| Random Errors | Statistical fluctuations (in either direction) in measured data | Instrument resolution limitations, environmental variability, physical variations | Statistical analysis, averaging over multiple observations, improved measurement precision |

| Precision | Measure of how well a result can be determined without reference to a theoretical value | Reliability or reproducibility of the result | Improved instrument design, controlled measurement conditions |

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true or accepted value | Measurement error or amount of inaccuracy | Calibration, comparison with known standards, elimination of systematic biases |

Numerical vs. Modeling Errors

Beyond the fundamental categories of systematic and random errors, the computational modeling domain requires a specialized classification distinguishing numerical from modeling errors. Numerical errors originate from the computational techniques employed to solve mathematical formulations, including discretization approximations, convergence thresholds, and round-off errors in digital computation [19] [20]. These errors are primarily concerned with how accurately the mathematical equations are solved computationally.

Modeling errors, conversely, arise from the fundamental formulation of the model itself and its parameters when representing physical, biological, or chemical reality [21] [4]. These include incomplete understanding of underlying mechanisms, incorrect simplifying assumptions, or inaccurate parameter values derived from experimental data. The table below contrasts the defining characteristics of these two critical error types in computational research.

Table 2: Numerical Errors vs. Modeling Errors in Computational Research

| Characteristic | Numerical Errors | Modeling Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Computational solution techniques | Model formulation and parameterization |

| Examples | Discretization errors, round-off errors, convergence thresholds | Incorrect mechanistic assumptions, oversimplified biology, inaccurate parameters |

| Detection Methods | Code verification, mesh refinement studies, convergence testing | Validation against experimental data, uncertainty quantification, model selection techniques |

| Reduction Strategies | Higher-resolution discretization, improved solver tolerance, advanced numerical methods | Improved experimental design, incorporation of additional biological knowledge, parameter estimation from comprehensive datasets |

| Impact on Predictions | Affects solution accuracy for given mathematical model | Affects biological fidelity and real-world predictive capability |

Experimental Protocols for Error Quantification

Standardized Benchmarking Approaches

Robust experimental protocols for error quantification employ standardized benchmarking approaches that enable meaningful comparison across different modeling methodologies. In systems biology, comprehensive benchmark collections provide rigorously defined problems with known solutions for evaluating computational methodologies [21]. These benchmarks typically include the dynamic model equations (e.g., ordinary differential equations for biochemical reaction networks), corresponding experimental data, observation functions describing how model states relate to measurements, and assumptions about measurement noise distributions and parameters [21].

A representative benchmarking protocol involves several critical steps. First, model calibration is performed using designated training data to estimate unknown parameters. Next, model validation is conducted against independent test datasets not used during calibration. Finally, predictive capability is assessed by comparing model predictions with experimental outcomes under novel conditions not used in model development. Throughout this process, specialized statistical measures quantify different aspects of model performance, including goodness-of-fit metrics, parameter identifiability analysis, and residual analysis to detect systematic deviations [21] [4].

Uncertainty Quantification Methodologies

Uncertainty quantification represents a critical component of error analysis, providing statistical characterization of the confidence in model predictions. For computational models in regulatory settings, such as medical device applications, comprehensive Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) processes are employed [4]. The ASME VV-40-2018 technical standard provides a risk-informed credibility assessment framework that begins with defining the Context of Use (COU)—the specific role and scope of the model in addressing a question of interest [4].

The experimental workflow for uncertainty quantification typically involves:

- Parameter Uncertainty Analysis: Evaluating how uncertainty in input parameters propagates to uncertainty in model outputs, often using sensitivity analysis techniques like Sobol indices or Morris methods.

- Experimental Error Incorporation: Accounting for measurement errors in experimental data used for model calibration, often assuming independent normally distributed additive errors [21].

- Model discrepancy characterization: Quantifying systematic differences between model predictions and reality that persist even after parameter calibration.

- Predictive Uncertainty Estimation: Combining parameter, experimental, and model structure uncertainties to estimate total uncertainty in model predictions for decision-making [4].

Comparative Analysis of Error Types Across Disciplines

Domain-Specific Error Manifestations

The manifestation and relative importance of different error types vary significantly across scientific disciplines, reflecting domain-specific challenges and methodological approaches. In systems biology, benchmark problems for dynamic modeling of intracellular processes reveal that modeling errors often dominate due to incomplete knowledge of biological mechanisms and limited quantitative data [21]. For these models of biochemical reaction networks, parameters are frequently non-identifiable from available data, and structural model errors arise from necessary simplifications of complex cellular processes.

In wave energy converter (WEC) design, comparative studies of linear, weakly nonlinear, and fully nonlinear modeling approaches demonstrate how model selection introduces specific error patterns [19]. Simplified linear models may underestimate structural loads or overestimate energy production in certain operational conditions, potentially leading to less cost-effective designs. The benchmarking process reveals trade-offs between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, with different modeling approaches exhibiting characteristic error profiles for various performance indicators like power output, fatigue loads, and levelized cost of energy [19].

For building energy models, studies benchmarking validation practices reveal that standard models like CEN ISO 13790 and 52016-1 cannot be considered properly validated when assessed against rigorous verification and validation frameworks from scientific computing [20]. This highlights how modeling errors can persist even in standardized approaches widely adopted in industry, potentially contributing to the recognized performance gap between predicted and actual building energy consumption.

Quantitative Error Comparisons

Direct quantitative comparison of errors across computational models requires standardized metrics and benchmarking initiatives. The Credibility of Computational Models Program at the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health addresses the challenge of unknown or low credibility of existing models, many of which have never been rigorously evaluated [17]. This program focuses on developing new credibility assessment frameworks and conducting domain-specific research to establish model capability when used in regulatory submissions.

In systems biology, a comprehensive collection of 20 benchmark problems provides a basis for comparing model performance across different methodologies [21]. These benchmarks span models with varying complexity (ranging from 9 to 269 parameters) and data availability (from 21 to 27,132 data points per model), enabling systematic evaluation of how error magnitudes scale with problem complexity. The benchmark initiative provides the models in standardized formats, including human-readable forms and machine-readable SBML files, along with experimental data and detailed documentation of observation functions and noise models [21].

Table 3: Error Analysis in Computational Modeling Across Disciplines

| Discipline | Primary Error Challenges | Benchmarking Initiatives | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systems Biology | Parameter identifiability, limited quantitative data, structural model simplifications | 20 benchmark problems with experimental data; models with 9-269 parameters [21] | FDA Credibility of Computational Models Program; ASME VV-40-2018 standard [17] [4] |

| Wave Energy Converters | Trade-offs between model fidelity and computational efficiency; under-estimation of structural loads | Comparison of linear, weakly nonlinear, and fully nonlinear modeling approaches [19] | Accuracy in power performance predictions; impact on levelized cost of energy estimates [19] |

| Building Energy Modeling | Performance gap between predicted and actual energy use; inadequate validation of standard models | Benchmarking against V&V frameworks from scientific computing; analysis of CEN ISO 13790 and 52016-1 [20] | Need for scientifically based standard models; Building Information Modelling (BIM) integration [20] |

| Medical Devices | Model credibility for regulatory decisions; insufficient verification and validation | Risk-informed credibility assessment; model influence vs. decision consequence analysis [4] | FDA guidance on computational modeling; ASME VV-40-2018 technical standard [17] [4] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust error analysis requires specialized computational tools and frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for evaluating and distinguishing numerical and modeling errors in computational studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Error Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Error Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Model Collections | 20 systems biology benchmark models [21]; DREAM challenge problems | Provide standardized test cases with known solutions for method comparison and validation |

| Modeling Standards and Formats | Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML); Simulation Experiment Description Markup Language (SED-ML) | Enable model reproducibility and interoperability; facilitate error analysis across computational platforms |

| Verification Tools | Code verification test suites; mesh convergence analysis tools | Identify and quantify numerical errors in computational implementations |

| Uncertainty Quantification Frameworks | ASME VV-40-2018 standard; Bayesian inference tools; sensitivity analysis packages | Provide structured approaches for quantifying and characterizing modeling uncertainties |

| Validation Datasets | Experimental data with error characterization; validation experiments specifically designed for model testing | Enable assessment of modeling errors through comparison with empirical observations |

Error Propagation and Analysis Frameworks

Formal error propagation frameworks provide mathematical foundations for quantifying how uncertainties in input parameters and measurements translate to uncertainties in model predictions. The fundamental approach involves calculating the relative uncertainty, defined as the ratio of the uncertainty to the measured quantity [16]. For a measurement expressed as (best estimate ± uncertainty), the relative uncertainty provides a dimensionless measure of quality that enables comparison across different measurements and scales.

For complex models where analytical error propagation is infeasible, computational techniques like Monte Carlo methods are employed to simulate how input uncertainties propagate through the model. These methods repeatedly sample from probability distributions representing input uncertainties and compute the resulting distribution of model outputs. This approach captures both linear and nonlinear uncertainty propagation and can handle complex interactions between uncertain parameters [16] [4].

Implications for Computational Model Verification Research

The systematic distinction between numerical and modeling errors has profound implications for computational model verification research and its applications in scientific discovery and product development. For drug development professionals, understanding these error sources is essential when employing computational approaches for evaluating drug combinations, where network models help identify mechanistically compatible drugs and generate hypotheses about their mechanisms of action [18]. The regulatory pathway for drug combination approval is largely determined by the approval status of individual compounds, making credible computational predictions invaluable for efficient development.

The emergence of in silico trials as a regulatory-accepted approach for evaluating medical products further elevates the importance of rigorous error analysis [4]. Regulatory agencies now consider evidence produced through modeling and simulation, but require demonstration of model credibility for specific contexts of use. The ASME VV-40-2018 standard provides a methodological framework for this credibility assessment, emphasizing that model risk should inform the extent of verification and validation activities [4]. This risk-informed approach recognizes that not all applications require the same level of model fidelity, enabling efficient allocation of resources for error reduction based on the consequences of incorrect predictions.

Future advances in computational model verification research will need to address ongoing challenges, including insufficient data for model development and validation, lack of established best practices for many application domains, and limited availability of credibility assessment tools [17]. As noted in studies of building energy models, increasing consensus among scientists on verification and validation procedures represents a critical prerequisite for developing scientifically based standard models [20]. By continuing to refine methodologies for distinguishing, quantifying, and reducing both numerical and modeling errors, the research community can enhance the predictive capability of computational models across diverse scientific and engineering disciplines.

Verification—the process of ensuring that a system, model, or implementation correctly satisfies its specified requirements—is a cornerstone of reliability in both engineering and computational science. History is replete with catastrophic failures that resulted from inadequate verification processes. These failures, while tragic, provide invaluable lessons for contemporary research, particularly in the emerging field of benchmark problems for computational model verification. This article examines historical verification failures across engineering disciplines, extracts their fundamental causes, and demonstrates how these lessons directly inform the design of robust verification benchmarks and methodologies in computational research, including drug development. By understanding how verification broke down in concrete historical cases, researchers can develop more rigorous validation frameworks that prevent similar failures in computational models.

Historical Case Studies of Verification Failures

The following case studies illustrate how deficiencies in verification protocols—whether in mechanical design, safety systems, or operational procedures—have led to disastrous outcomes. Analysis of these events reveals common patterns that are highly relevant to modern computational verification.

Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster (1986)

The Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff, resulting in the loss of seven crew members. The failure was traced to the O-ring seals in the solid rocket boosters [22].

- Verification Failure: The O-rings' susceptibility to temperature was known from previous tests, but this critical variable was not adequately incorporated into the pre-launch verification process. The verification protocol did not properly account for the effect of cold weather on seal resilience.

- Quantitative Gap: Test data showing O-ring failure at low temperatures existed but was not conclusively linked to launch commit criteria.

- Lesson for Computational Research: Verification must be conducted across the entire anticipated operational envelope, including edge cases. A benchmark that only tests a model under "normal" conditions is insufficient. This directly informs the need for stress-testing computational models under a wide range of parameters.

Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster (1986)

The Chernobyl disaster was one of the worst nuclear accidents in history. It was caused by a combination of a flawed reactor design and serious operator errors during a safety test [22].

- Verification Failure: The safety test procedure itself was not adequately verified to ensure it could be conducted without triggering a catastrophic failure. The complex, counter-intuitive behavior of the reactor under the test conditions was not understood or properly modeled.

- System Complexity: The accident highlights the danger of emergent properties in complex systems, where the interaction of components creates unpredictable risks.

- Lesson for Computational Research: It is critical to verify not only individual model components but also their integrated behavior under unusual but plausible scenarios. This underscores the need for benchmarks that test system-level integration and adversarial conditions.

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (2010)

The explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig led to the largest marine oil spill in history. A critical point of failure was the blowout preventer (BOP), a last-line-of-defense safety device that failed to seal the well [22].

- Verification Failure: The BOP had not been adequately verified to function under the actual high-pressure conditions it encountered. The verification tests and maintenance protocols were insufficient to guarantee reliability in a real-world crisis.

- Single Point of Failure: The disaster demonstrates the risk of relying on a complex safety system whose own verification is incomplete.

- Lesson for Computational Research: Fail-safe mechanisms and contingency plans within a computational pipeline must themselves be rigorously verified. Benchmarks should be designed to test failure modes and the robustness of a model's corrective measures.

Titan Submersible Implosion (2023)

The Titan submersible imploded during a dive to the Titanic wreckage. The failure was attributed to the experimental design of its carbon-fiber hull [22].

- Verification Failure: The vessel's novel design bypassed standard verification and certification processes. It was not reviewed or inspected by an independent regulatory body, and its design predictions were not validated against sufficient real-world testing.

- Lack of Independent Review: The development process lacked the crucial external verification that is standard in engineering.

- Lesson for Computational Research: This highlights the paramount importance of independent, third-party verification and the use of standardized, peer-reviewed benchmarks. Relying solely on internal or developer-reported metrics is insufficient for establishing trust in a model's capabilities.

Table 1: Summary of Historical Engineering Disasters and Core Verification Failures

| Event | Primary Verification Failure | Consequence | Lesson for Computational Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space Shuttle Challenger (1986) | Incomplete testing of critical components (O-rings) across full operational envelope (temperature) [22]. | Loss of vehicle and crew. | Benchmarks must test models under edge cases and adverse conditions, not just average performance. |

| Chernobyl Disaster (1986) | Inadequate verification of safety test procedures and understanding of complex system interactions [22]. | Widespread radioactive contamination. | Benchmarks must probe system-level behavior and emergent properties in complex models. |

| Deepwater Horizon (2010) | Failure to verify the reliability of a critical safety system (blowout preventer) under real failure conditions [22]. | Massive environmental damage. | Verification must include fail-safe mechanisms and stress-test recovery protocols. |

| Titan Submersible (2023) | Avoidance of standard certification and independent verification processes for a novel design [22]. | Loss of vessel and occupants. | Necessity of independent, third-party evaluation against standardized benchmarks. |

The Link to the Scientific Replication Crisis

The replication crisis, particularly in psychology and medicine, is the epistemological counterpart to engineering verification failures. It represents a systemic failure to verify scientific claims through independent reproduction [23]. A 2015 large-scale project found that a significant proportion of landmark studies in cancer biology and psychology could not be reproduced [24]. This crisis has been attributed to factors like publication bias, questionable research practices (e.g., p-hacking), and a lack of transparency in methods and data [23] [24].

The core parallel is that a single study or simulation, like a single engineering test, is not a verification. Verification is a process, not an event. It requires:

- Direct Replication: Repeating the exact same experiment or simulation to control for sampling error, artifacts, and fraud [24].

- Conceptual Replication: Testing the underlying hypothesis or model using different methods to ensure generalizability [24].

Failures to replicate are not necessarily failures of science; rather, they are an essential part of scientific inquiry that helps identify boundary conditions and hidden variables [25]. The journey from a non-replicable initial finding to a robust theory often takes decades, as seen in the development of neural networks, which experienced multiple "winters" before the emergence of reliable deep learning [25].

A Modern Case: Verification Failures in AI Benchmarking

The field of artificial intelligence currently faces its own verification crisis, directly mirroring historical precedents. A 2025 study from the Oxford Internet Institute found that only 16% of 445 large language model (LLM) benchmarks used rigorous scientific methods to compare model performance [9].

Key verification failures identified include:

- Lack of Construct Validity: ~50% of benchmarks claimed to measure abstract concepts like "reasoning" or "harmlessness" without offering clear, operational definitions [9].

- Non-Rigorous Sampling: 27% of benchmarks relied on convenience sampling (e.g., reusing problems from calculator-free exams) rather than rigorous random or stratified sampling, which fails to probe model weaknesses [9].

- Contamination: Model performance is inflated when training data contains benchmark test problems, invalidating the benchmark's ability to verify true capability [9] [6].

These issues demonstrate a failure to apply the lessons of history. Without verified, robust benchmarks, claims of AI advancement are as unreliable as an unverified engineering design.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of AI Benchmark Quality (from OII Study) [9]

| Benchmarking Metric | Finding in AI Benchmark Study | Implication for Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Methodological Rigor | Only 16% of 445 LLM benchmarks used rigorous scientific methods. | Widespread lack of basic verification standards in the field. |

| Construct Definition | ~50% failed to clearly define the abstract concept they claimed to measure. | Impossible to verify what is being measured, leading to ambiguous results. |

| Sampling Method | 27% relied on non-representative convenience sampling. | Results do not generalize, failing to verify performance in real-world conditions. |

A Framework for Rigorous Verification and Benchmarking

Learning from historical failures, we propose a verification framework for computational models, articulated in the workflow below. This process integrates lessons from engineering disasters, the replication crisis, and modern AI benchmarking failures.

Verification Workflow for Computational Models

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Verification

Drawing from high-fidelity validation practices in engineering [26] and modern AI benchmark design [9] [6], the following protocols are essential for rigorous verification:

Define the Specification with Operational Clarity: Before any testing, unambiguously define what the model is supposed to do. This involves:

- Operationalizing Abstract Concepts: Convert terms like "reasoning" or "safety" into measurable quantities. For a drug discovery model, this could mean defining "efficacy" as a specific reduction in tumor size in a defined animal model, and "toxicity" as the absence of certain physiological markers [9].

- Formal Specifications: Where possible, use formal methods and logic (e.g., Hoare triples) to define pre-conditions, post-conditions, and invariants that the code must satisfy. The move towards "vericoding" (generating formally verified code) exemplifies this rigorous approach [6].

Design Comprehensive Benchmarks: The benchmark suite itself must be verified to be effective.

- Cover the Operational Envelope: Include easy, typical, and edge-case scenarios. For a model predicting protein folding, this means testing on proteins with common and rare structures. This directly addresses the Challenger failure by testing across all expected conditions.

- Prevent Contamination: Ensure test data is not included in training data. This may require curated, held-out datasets or live challenges, as seen in the VNN-COMP competition for neural network verification [14].

- Use Statistical Rigor: Employ random or stratified sampling instead of convenience sampling to ensure results are representative and generalizable [9].

Execute Tests and Perform Independent Auditing:

- Blinded Evaluation: Where possible, evaluations should be performed blinded to the model's identity to prevent bias.

- Third-Party Verification: The gold standard is independent replication and verification by a neutral body. This is a core principle in clinical trials and is embodied in competitions like VNN-COMP [14] and the push for verified benchmarks in AI [9]. This step addresses the Titan submersible's fatal flaw.

Iterate Based on Root Cause Analysis: When verification fails, conduct a deep analysis to understand the "why." Was it a data flaw? A model architecture limitation? An poorly defined objective? Use this analysis to refine the model and the benchmarks, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Verification

The following table details key solutions and methodologies required for implementing a rigorous verification pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Model Verification

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Verification Process | Exemplar / Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Formal Specification Languages | Provides a mathematically precise framework for defining model requirements and correctness conditions, enabling automated verification [6]. | Dafny, Lean, Verus/Rust [6] |

| Curated & Held-Out Test Sets | Serves as a ground truth for evaluating model performance on unseen data, preventing overfitting and providing a true measure of generalizability. | VNN-COMP Benchmarks (e.g., ACAS-Xu, MNIST-CIFAR) [14] |

| Vericoding Benchmarks | Provides a test suite for evaluating the ability of AI systems to generate code that is formally proven to be correct, moving beyond error-prone "vibe coding" [6]. | DafnyBench, CLEVER, VERINA [6] |

| High-Fidelity Reference Data | Experimental or observational data of sufficient quality and precision to serve as a validation target for simulation results [26]. | FZG Gearbox Data (engineering) [26], Public Clinical Trial Datasets (biology) |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | Tools to ensure benchmark results are statistically sound, not the result of random chance or p-hacking. | R, Python (SciPy, StatsModels) |

The historical record, from the Challenger disaster to the AI benchmarking crisis, delivers a consistent message: verification is not an optional add-on but a fundamental requirement for reliability. Failures occur when verification is rushed, gamed, or bypassed. For researchers and drug development professionals, the path forward is clear. It requires adopting a mindset of rigorous, independent verification, using benchmarks that are themselves well-specified and robust. By learning from the painful lessons of the past, we can build computational models and AI systems that are not merely innovative, but are also demonstrably reliable, safe, and trustworthy. The future of critical applications in drug development and healthcare depends on this disciplined approach to verification.

Verification constitutes a foundational pillar of the scientific method, serving as the critical process for confirming the truth and accuracy of knowledge claims through empirical evidence and reasoned argument. In modern computational science and engineering, this epistemological principle is formalized through the framework of Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ). This systematic approach provides the mathematical and philosophical underpinnings for assessing computational models against theoretical benchmarks and empirical observations [27] [28]. The epistemological significance of verification lies in its capacity to establish computational credibility, ensuring that models accurately represent theoretical formulations before they are evaluated against physical reality.

The rising importance of verification corresponds directly with the expanding role of computational modeling across scientific domains. As noted in the context of the 2025 VVUQ Symposium, "As we enter the age of AI and machine learning, it's clear that computational modeling is the way of the future" [27]. This transformation necessitates robust verification methodologies to maintain scientific rigor in increasingly complex digital research environments. The epistemological framework of verification thus bridges classical scientific reasoning with contemporary computational science, creating a structured approach to knowledge validation in silico experimentation.

Theoretical Framework: Verification in Computational Science

The VVUQ Paradigm

Within computational science, verification is formally distinguished from, yet fundamentally connected to, validation and uncertainty quantification. This triad forms a comprehensive epistemological framework for establishing model credibility:

Verification: The process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution [28]. This addresses the question, "Have we solved the equations correctly?" from an epistemological standpoint.

Validation: The process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the intended uses of the model [28]. This answers, "Have we solved the correct equations?"

Uncertainty Quantification: The systematic assessment of uncertainties in mathematical models, computational solutions, and experimental data [27]. This addresses the epistemological question, "How confident can we be in our results given various sources of doubt?"

This structured approach provides a philosophical foundation for computational science, establishing a rigorous methodology for building knowledge through simulation and modeling. The framework acknowledges that different forms of evidence and argumentation contribute collectively to scientific justification.

Epistemological Significance

The epistemological significance of verification lies in its capacity to address fundamental questions of justification in computational science. When researchers engage in verification activities, they are essentially asking: How do we know what we claim to know through our computational models? The process provides multiple forms of justification:

Mathematical justification through code verification ensures computational implementations faithfully represent formal theories.

Numerical justification through solution verification quantifies numerical errors and their impact on results.

Practical justification through application to benchmark problems demonstrates performance under controlled conditions with known solutions.

This multi-faceted approach to justification reflects the evolving nature of scientific methodology in computational domains, where traditional empirical controls are supplemented with mathematical and numerical safeguards.

Benchmark Problems as Experimental Frameworks

The Function of Benchmarks in Knowledge Production

Benchmark problems serve as crucial experimental frameworks in verification research, functioning as standardized test cases with known solutions or well-characterized behaviors against which computational tools can be evaluated. These benchmarks operate as epistemic artifacts that facilitate knowledge transfer across research communities while enabling comparative assessment of methodological approaches. Their epistemological value lies in creating shared reference points that allow for collective judgment of verification claims across the scientific community.

The construction and use of benchmarks represent a form of communal verification, where individual claims of methodological performance are tested against community-established standards. This process mirrors traditional scientific practices of experimental replication while adapting them to computational contexts. As evidenced by the International Verification of Neural Networks Competition (VNN-COMP), benchmarks create "a mechanism to share and standardize relevant benchmarks to enable easier progress within the domain, as well as to understand better what methods are most effective for which problems" [14].

Domain-Specific Benchmark Applications

Table 1: Benchmark Problems Across Computational Domains

| Domain | Benchmark Examples | Verification Focus | Knowledge Claims Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Networks | ACAS-Xu, MNIST, CIFAR-10 classifiers [14] | Formal guarantees about neural network behaviors | Robustness to adversarial examples, safety envelope compliance |

| Drug Development | PharmaBench ADMET properties [29] | Predictive accuracy for pharmacokinetic properties | Reliability of early-stage drug efficacy and toxicity predictions |

| Materials Science | AI-ready materials datasets [30] | Predictive capabilities for material processing and performance | Accuracy in predicting complex material behaviors across scales |

| Medical Devices | Model-informed drug development tools [31] | Context-specific model performance | Reliability of model-informed clinical trial designs and dosing strategies |

The diversity of benchmark applications demonstrates how verification principles adapt to domain-specific epistemological requirements. In neural network verification, benchmarks focus on establishing formal guarantees about system behaviors, particularly for safety-critical applications [14]. In pharmaceutical development, benchmarks like PharmaBench emphasize predictive accuracy for complex biological properties, addressing the epistemological challenge of extrapolating from computational models to clinical outcomes [29].

Comparative Analysis of Verification Methodologies

Quantitative Comparison of Verification Approaches

Table 2: Verification Methodologies Across Computational Fields

| Methodology | Theoretical Basis | Application Context | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-anonymity Assessment [32] | Statistical re-identification risk | Quantitative data privacy protection | Provides measurable privacy guarantees | Only accounts for processed variables in analysis |

| Physics-Based Regularization [30] | Physical laws and constraints | Machine learning models for physical systems | Enhances model generalizability | Requires domain expertise to implement effectively |

| Formal Verification [14] | Mathematical proof methods | Neural network safety verification | Provides rigorous guarantees | Computationally intensive for complex networks |

| Fit-for-Purpose Modeling [31] | Context-specific validation | Drug development decision-making | Aligns verification with intended use | Requires careful definition of context of use |

The comparative analysis reveals how verification methodologies embody different epistemological approaches to justification. K-anonymity assessment provides probabilistic justification through statistical measures of re-identification risk [32]. In contrast, formal verification of neural networks seeks deductive justification through mathematical proof methods [14]. The epistemological strength of each approach correlates with its capacity to provide appropriate forms of evidence for specific knowledge claims within their respective domains.

Experimental Protocols in Verification Research

Verification research employs standardized experimental protocols that reflect its epistemological commitments to transparency and reproducibility. These protocols typically include:

1. Benchmark Selection and Characterization The process begins with selecting appropriate benchmark problems that represent relevant challenges within the domain. For example, in neural network verification, benchmarks include "ACAS-Xu, MNIST, CIFAR-10 classifiers, with various parameterizations (initial states, specifications, robustness bounds, etc.)" [14]. The epistemological requirement here is that benchmarks adequately represent the problem space while having well-characterized expected behaviors.

2. Tool Execution and Performance Metrics Verification tools are executed against selected benchmarks using standardized performance metrics. In VNN-COMP, this involves running verification tools on benchmark problems and measuring capabilities in proving properties of neural networks [14]. The epistemological significance lies in creating comparable evidence across different methodological approaches.

3. Result Validation and Uncertainty Assessment Results undergo rigorous validation, including uncertainty quantification. As noted in materials science AI applications, "efficacy of any simulation method needs to be validated using experimental or other high-fidelity computational approaches" [30]. This step addresses the epistemological challenge of establishing truth in the absence of perfect reference standards.

Signaling Pathways in Verification Research

Verification Research Workflow

The verification research workflow demonstrates the epistemological pathway from initial problem formulation to justified knowledge claims. This pathway illustrates how verification processes incorporate multiple forms of evidence, beginning with theoretical foundations, proceeding through computational benchmarking, and culminating in empirical validation and uncertainty assessment. Each stage contributes distinct justificatory force to the final knowledge claims, with verification serving as the bridge between theoretical frameworks and empirical testing.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Tools

Computational Verification Tools

Table 3: Essential Verification Tools and Their Epistemological Functions

| Tool/Category | Epistemological Function | Application Context | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| VNN-LIB Parser [14] | Standardizes specification of verification properties | Neural network verification | Python framework for parsing VNN-LIB specifications |

| Multi-agent LLM System [29] | Extracts experimental conditions from unstructured data | ADMET benchmark creation | GPT-4 based agents for bioassay data mining |

| K-anonymity Calculators [32] | Quantifies re-identification risk in datasets | Privacy protection in research data | Statistical tools in R or Stata for risk assessment |

| Fit-for-Purpose Evaluation [31] | Assesses model alignment with intended use | Drug development decision-making | Context-specific validation frameworks |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools [27] | Characterizes and propagates uncertainties in models | Computational model evaluation | Sensitivity analysis and statistical sampling methods |

These methodological tools serve as the epistemic instruments of verification research, enabling researchers to implement verification principles in practical computational contexts. Their epistemological significance lies in their capacity to operationalize abstract verification concepts into concrete assessment procedures that generate comparable evidence across studies and research communities.

Case Study: Verification in Pharmaceutical Development

The application of verification principles in Model-Informed Drug Discovery and Development (MID3) provides a compelling case study of verification's epistemological role in high-stakes scientific domains. The "fit-for-purpose" strategic framework in MID3 exemplifies how verification adapts to domain-specific epistemological requirements [31]. This approach requires that verification activities be closely aligned with the "Question of Interest" and "Context of Use" (COU), acknowledging that verification standards must vary according to the consequences of model failure.

In pharmaceutical development, verification encompasses multiple methodological approaches:

1. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Verification QSAR models undergo verification through benchmarking against known chemical activities, ensuring computational predictions align with established structure-activity relationships [31]. This verification provides epistemological justification for using these models in early-stage drug candidate selection.

2. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Model Verification PBPK models are verified through comparison with physiological data and established pharmacokinetic principles [31]. This verification process creates justification for extrapolating drug behavior across populations and dosing scenarios.

3. AI/ML Model Verification in Drug Discovery Machine learning approaches in drug discovery require specialized verification methodologies due to their data-driven nature. As noted in PharmaBench development, "Accurately predicting ADMET properties early in drug development is essential for selecting compounds with optimal pharmacokinetics and minimal toxicity" [29]. The verification process here focuses on ensuring predictive accuracy across diverse chemical spaces and biological contexts.

The epistemological significance of verification in pharmaceutical development is underscored by its role in regulatory decision-making. Verification evidence contributes to the "totality of MIDD evidence" that supports drug approval and labeling decisions [31]. This demonstrates how verification processes directly impact real-world decisions with significant health and ethical implications.

Verification remains a dynamic and evolving epistemological practice that continues to adapt to new computational methodologies and scientific challenges. The ongoing development of verification standards and benchmarks reflects the scientific community's commitment to maintaining rigorous justificatory practices amidst rapidly advancing computational capabilities. As computational models increase in complexity and scope, particularly with the integration of AI and machine learning, verification methodologies must correspondingly evolve to address new forms of epistemological uncertainty.

The future of verification research will likely involve developing hybrid approaches that combine traditional mathematical verification with statistical and empirical methods, creating multi-faceted justificatory frameworks suited to complex computational systems. This evolution will reinforce verification's fundamental role in the scientific method, ensuring that computational advancement remains grounded in epistemological rigor and evidential justification.

Methodologies and Applications: Designing Effective Verification Benchmarks for Biomedical Models

A Standardized Workflow for Deterministic Model Verification

In computational science and engineering, model verification is the process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution [33]. This differs from validation, which assesses how well the model represents physical reality. As computational models play increasingly critical roles in fields from drug development to nuclear reactor safety, establishing standardized verification workflows becomes essential for ensuring reliability and credibility of predictions [33] [34].

The use of benchmark problems—well-defined problems with established solutions—provides a fundamental methodology for verification. These benchmarks enable cross-comparison of different computational approaches, identification of methodological errors, and assessment of numerical accuracy without the confounding uncertainties of experimental measurement [35]. This guide examines current verification methodologies through the lens of established benchmark problems, comparing approaches across multiple disciplines to extract generalizable principles for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Model Verification

Distinguishing Verification from Validation

A critical foundation for any verification workflow is understanding the distinction between verification and validation:

- Verification: "Solving the equations right" - Assessing whether the computational model correctly implements the intended mathematical model and numerical methods [33].

- Validation: "Solving the right equations" - Determining how well the computational model represents physical reality through comparison with experimental data [33].

This distinction, formalized by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) and other standards organizations, emphasizes that verification addresses numerical correctness rather than physical accuracy [33].

Understanding potential error sources guides effective verification strategy design:

Table: Classification of Errors in Computational Models

| Error Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical Errors | Arise from computational solution techniques | Discretization error, incomplete grid convergence, computer round-off errors [33] |

| Modeling Errors | Due to mathematical representation approximations | Geometry simplifications, boundary condition assumptions, material property specifications [33] |

| Acknowledged Errors | Known limitations accepted by the modeler | Physical approximations (e.g., rigid bones in joint models), convergence tolerances [33] |

| Unacknowledged Errors | Mistakes in modeling or programming | Coding errors, incorrect unit conversions, logical flaws in algorithms [33] |

Standardized Verification Workflow

Based on analysis of verification approaches across multiple disciplines, we propose a comprehensive workflow for deterministic model verification.

Core Verification Procedures

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for deterministic model verification:

Deterministic Model Verification Workflow

Verification Metrics and Acceptance Criteria

Establishing quantitative metrics is essential for objective verification assessment:

Table: Verification Metrics and Acceptance Criteria

| Verification Step | Quantitative Metrics | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Time Step Convergence | Percentage discretization error: ( eqi = \frac{q{i^} - q_i}{q_{i^}} \times 100 ) [34] | Error < 5% relative to reference time-step [34] |

| Smoothness Analysis | Coefficient of variation D of first difference of time series [34] | Lower D values indicate smoother solutions; threshold depends on application |

| Benchmark Comparison | Relative error vs. reference solutions [35] | Problem-dependent; often < 1-5% for key output quantities |

| Code Verification | Order of accuracy assessment [33] | Expected theoretical order of accuracy achieved |

Benchmark Problems in Practice

Established Benchmark Problems

Benchmark problems provide reference solutions for verification across disciplines: