Fixing Discretization Error: A Researcher's Guide to Mesh Convergence in Biomedical Simulation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, execute, and validate mesh convergence studies in Finite Element Analysis.

Fixing Discretization Error: A Researcher's Guide to Mesh Convergence in Biomedical Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, execute, and validate mesh convergence studies in Finite Element Analysis. Covering foundational theory, step-by-step methodologies, advanced troubleshooting for complex biomedical models, and robust validation techniques, it addresses the critical challenge of discretization error to ensure reliable simulation outcomes in areas like implant design and tissue mechanics. The guidance is grounded in practical applications, helping to build credibility for computational models used in clinical research.

What is Discretization Error? Building the Foundation for Reliable FEA

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a discretization error? Discretization error is the error that occurs when a function of a continuous variable is represented in a computer by a finite number of evaluations, such as on a discrete lattice or grid [1]. It is the fundamental difference between the exact solution of the original mathematical model (e.g., a set of partial differential equations) and the solution obtained from a numerical approximation on that discrete grid [2]. This error arises because the simple interpolation functions of individual finite elements cannot always capture the actual complex behavior of the continuum [3].

How does discretization error differ from other computational errors? Discretization error is distinct from other common computational errors [1] [2].

- vs. Round-off error: Caused by the finite precision of floating-point arithmetic in computers.

- vs. Iterative convergence error: Arises when an iterative numerical method is stopped before reaching the exact solution of the discrete equations.

- vs. Physical modeling error: Results from inaccuracies or simplifications in the mathematical description of the physical system itself. Discretization error would exist even if calculations could be performed with exact arithmetic, as it stems from the discrete representation of the problem itself [1].

Why is mesh convergence important? Mesh convergence is the process of refining the computational mesh until the solution stabilizes to a consistent value [4]. A mesh convergence study is crucial because it helps determine the level of discretization error in a simulation [2]. By systematically comparing results from simulations with varying mesh densities, you can identify the point where further refinement no longer significantly improves the results, ensuring your solution is both accurate and computationally efficient [4] [5].

What are common symptoms of high discretization error? Common indicators of significant discretization error in your results include [3]:

- Stress/Strain Jumps: Visible discontinuities or jumps in stresses or strains between adjacent elements.

- Poor Boundary Representation: Misrepresentation of the actual stresses or physical behavior at the model's boundaries.

- Lack of Equilibrium: Failure of the numerical solution to satisfy equilibrium conditions at every point in the domain.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Discretization Error in Stress Analysis

Problem: Your finite element analysis shows unrealistic stress concentrations or large jumps in stress values between elements.

Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Error Magnitude | Quantify the local discretization error using stress jumps between elements or equilibrium violations [3]. |

| 2 | Apply Local Mesh Refinement | Refine the mesh specifically in regions of high stress gradients (e.g., around holes, notches, sharp corners) [4]. |

| 3 | Re-run Simulation | Obtain a new solution with the refined mesh. |

| 4 | Check for Convergence | Compare results from the original and refined meshes. If changes are significant, repeat refinement until the solution stabilizes [4]. |

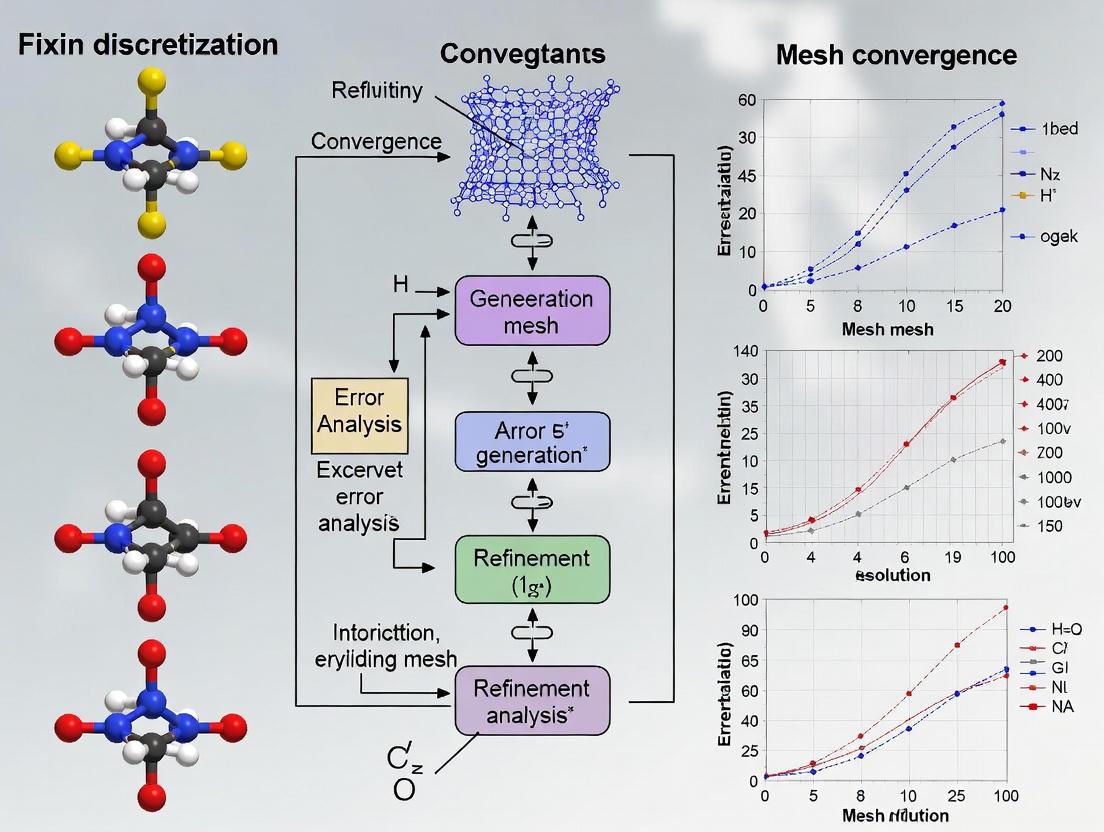

Diagram: Workflow for Mitigating Discretization Error

Issue 2: Managing Discretization Error in Regulatory Submissions for Drug Development

Problem: Ensuring that the discretization error in your predictive in silico model is sufficiently controlled for regulatory evaluation.

Solution:

| Step | Action | Regulatory Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define Context of Use (CoU) | Clearly state the model's purpose and the impact of its predictions on regulatory decisions [6]. |

| 2 | Perform Risk-Based Analysis | Assess the risk associated with an incorrect prediction due to discretization error [6] [7]. |

| 3 | Execute Mesh Convergence | Conduct a formal mesh convergence study to quantify and bound the discretization error [2]. |

| 4 | Document V&V Activities | Meticulously document all verification and validation activities, including error quantification [7]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Mesh Convergence Study

Aim: To determine a mesh density that provides a solution with acceptable discretization error without excessive computational cost [5].

Methodology:

- Initial Mesh: Generate a baseline mesh with a reasonable level of refinement.

- Simulation: Run the simulation and record the key output parameters of interest (e.g., maximum stress, displacement, flow rate).

- Systematic Refinement: Refine the mesh globally or in critical regions. Adaptive meshing procedures can automatically identify and refine regions with high error levels [3].

- Iterate: Repeat the simulation with the refined mesh.

- Comparison: Compare the results from successive mesh refinements. The process is complete when the change in the key parameters between subsequent refinements falls below a pre-defined acceptable threshold [4].

Diagram: Mesh Convergence Study Workflow

Protocol 2: Verification of Discretization Error Using Manufactured Solutions

Aim: To verify the order of accuracy of a numerical method and estimate discretization error when an analytical solution to the original problem is not available [8].

Methodology:

- Manufacture a Solution: Choose a smooth, non-trivial function that resembles the expected solution.

- Derive Source Terms: Substitute the manufactured solution into the governing partial differential equations (PDEs) to compute the necessary source terms that would make it an exact solution.

- Solve Numerically: Run the simulation on a series of progressively finer grids using the derived source terms and boundary conditions from the manufactured solution.

- Calculate Error: On each grid, compute the error as the difference between the numerical result and the known manufactured solution.

- Determine Convergence Rate: The observed rate at which the error decreases with grid refinement should match the theoretical order of accuracy of the numerical method [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Components for Discretization Error Analysis

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Mesh Generation Software | Creates the discrete spatial domain (grid/mesh) on which the governing equations are solved. The quality of this mesh directly influences discretization error [2]. |

| Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) Algorithm | Automatically refines the computational mesh in regions identified with high error, allowing for efficient error reduction without globally increasing computational cost [3]. |

| Grid Convergence Index (GCI) Method | Provides a standardized procedure for estimating the discretization error and reporting the uncertainty from a grid convergence study [2]. |

| Verification & Validation (V&V) Framework (e.g., ASME V&V 40) | A structured process for assessing the credibility of computational models, which includes the evaluation of discretization error within the context of the model's intended use and associated decision risk [6] [7]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Tools | A set of mathematical techniques used to characterize and quantify the impact of all sources of uncertainty, including discretization error, on the model's outputs [7]. |

Why Mesh Convergence is Non-Negotiable for Model Verification

Frequently Asked Questions

What is mesh convergence, and why is it critical for simulation accuracy? Mesh convergence is the process of progressively refining a computational mesh until the key results of a simulation (e.g., stresses, flow rates, or pressure drops) stop changing significantly. It is non-negotiable because it verifies that your numerical solution is independent of the discretization error introduced by the mesh itself. Without a mesh convergence study, your results may be quantitatively wrong, no matter how converged your solver residuals appear to be [9].

My simulation solves with a coarse mesh but fails to converge on a finer mesh. Why? This is a common issue. Finer meshes have less numerical dissipation, which can allow small physical instabilities (like vortex shedding) to appear, causing divergence in a steady-state simulation [10]. Additionally, as the mesh is refined, the aspect ratios of elements can become too large, leading to numerical round-off errors, particularly in boundary layers [10]. Switching to a transient simulation or improving mesh quality by ensuring even refinement in all directions can often resolve this [10].

I am performing a mesh convergence study, but my value of interest keeps changing. When do I stop? You stop when the change in your value of interest between two successive mesh refinements falls within a pre-defined, acceptable tolerance for your specific application [9]. For instance, if the average outlet temperature changes by less than 0.5°C between a 6-million and an 8-million cell mesh, the 6-million cell mesh can be considered to provide a mesh-independent solution [9].

What is the difference between solver convergence and mesh convergence? These are two distinct but equally important concepts:

- Solver Convergence: This indicates that for a specific mesh, the numerical solver has found a stable solution that satisfies the governing equations within a specified tolerance. This is typically monitored through residual plots [9].

- Mesh Convergence: This confirms that the solution itself (the final answer you report) is not a function of the cell size used. It ensures that discretization error has been minimized [9].

How can I troubleshoot a model that won't converge, even on a single mesh? Start with a linear static analysis to check the basic integrity of your model [11]. Ensure your load increments are not too large; use automatic incrementation and allow for more iterations (e.g., 20-25) [11]. Check for poor element quality, such as high aspect ratios (greater than 1:10), and refine the mesh in high-stress gradient areas [11]. Also, verify that you are using the appropriate stress data type (e.g., "Corner" stress instead of "Centroidal" stress for surface values like bending stress) [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Mesh Convergence Problems

| Problem | Symptoms | Possible Causes & Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divergence on Finer Meshes [10] | Solver fails with floating point errors or turbulence parameter divergence. Max stress increases linearly with element refinement. [12] | Reduced Numerical Damping: Physical instabilities are resolved. Poor Element Quality: High aspect ratios, especially in boundary layers. | Improve mesh quality, ensuring even refinement in all directions. Switch from a steady-state to a transient simulation. [10] Use "Corner" stress instead of "Centroidal" stress for surface values. [12] |

| Non-Converging Nonlinear Analysis [11] | The analysis fails to complete, with pivot/diagonal decay warnings or slow convergence. | Large Load Increments: The solver cannot find equilibrium. Poorly Shaped Elements: Aspect ratios >1:10. Material/Geometric Instabilities: Such as buckling or contact. | Use automatic load incrementation and increase the max number of iterations (e.g., 20-25). [11] Refine the mesh in critical areas and use an arc-length method for post-buckling response. [13] |

| Incorrect Stress Values [12] | Maximum stress values keep increasing with mesh refinement without settling. | Incorrect Stress Sampling: Using centroidal stress for bending problems measures stress at different distances from the neutral axis. | Change the results contour plot data type from "Centroid" to "Corner" to read stress values from the consistent surface location. [12] |

| Mesh-Dependent Integrated Values [10] | Volume-integrated values (e.g., scalar shear) keep increasing with mesh count, even after primary variables converge. | Noisy Derivatives: The integrated function may involve derived quantities (e.g., strain rates) that amplify discretization error. | Recognize that these quantities converge slower than primary variables. A pragmatic decision may be required to stop refinement within an acceptable error margin. [10] |

Quantitative Data for Mesh Independence

The following table summarizes data from a successful mesh independence study for an average outlet temperature. The goal is to find the mesh where the value of interest stabilizes within a user-defined tolerance.

Table: Example Mesh Independence Study for Average Outlet Temperature

| Mesh Size (Million Cells) | Average Outlet Temperature (°C) | Change from Previous Mesh | Within Tolerance? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 | 24.5 | -- | -- |

| 6.0 | 26.1 | +1.6 °C | No |

| 8.0 | 26.3 | +0.2 °C | Yes (if tolerance ≥ 0.5°C) |

Table: Stress Convergence Data Highlighting a Common Pitfall

| Element Size (mm) | Max Stress (MPa) - Centroidal | Max Stress (MPa) - Corner | Converged? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 | 165.0 | 171.2 | -- |

| 0.30 | 168.0 | 172.3 | -- |

| 0.20 | 170.5 | 173.6 | Yes (Values are tight) |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Software and Functions

Table: Key Tools for Mesh Convergence and Verification

| Tool / Software | Primary Function in Verification | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Ansys Meshing / Fidelity CFD [14] | High-Quality Mesh Generation | Provides physics-aware, automated, and intelligent meshing tools to produce the most appropriate mesh for accurate, efficient solutions. |

| Converge CFD [15] | Automated CFD Solving | A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software with advanced solver capabilities for simulating fluid behavior and thermodynamic properties. |

| Linear Solver | Basic Model Integrity Check | Performing a linear analysis before a nonlinear one helps check the model's basic behavior and integrity, a recommended first step. [11] |

| Arc-Length Method (e.g., Modified Riks) [13] | Tracking Post-Failure Response | An advanced nonlinear technique that allows the solution to trace through complex stability paths, such as those in buckling or material collapse. |

| Monitor Points/Integrated Values | Tracking Quantities of Interest | Defining and monitoring key outputs (e.g., pressure drop, max stress) is essential to ensure they reach a steady state during the simulation. [9] |

Experimental Protocol for a Mesh Independence Study

Follow this detailed methodology to ensure your solution is mesh-independent.

1. Perform Initial Simulation and Establish Baseline

- Create your initial mesh and run the simulation.

- Ensure solver convergence: Residual RMS errors should drop to at least 10⁻⁴, key monitor points must be steady, and domain imbalances should be below 1% [9].

- Record the values from your monitor points (e.g., maximum stress, average temperature).

2. Refine Mesh and Compare Results

- Refine your mesh globally, aiming for a factor of 1.5 to 2 times more elements than the previous mesh. Ensure refinement is even in all directions to maintain element quality [10] [9].

- Run the simulation again and ensure it meets the same solver convergence criteria.

- Compare the monitor point values from this refined mesh with those from the previous mesh.

3. Check Tolerance and Iterate

- If the change in your value of interest is within your acceptable tolerance (e.g., <1% change), you have likely achieved a mesh-independent solution.

- If the change is outside your tolerance, repeat Step 2 by further refining the mesh until the change between two consecutive meshes falls within the tolerance [9].

- For reporting and future similar analyses, use the smallest mesh that gave the mesh-independent solution to optimize computational time.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I ensure my computational model of a brain implant is producing accurate and reliable results?

- Answer: The accuracy of computational models, such as those simulating drug diffusion from an implant, relies heavily on a Mesh Independence Study. A solution is "mesh independent" when further refinement of the mesh does not significantly change the results. To achieve this:

- Run an Initial Simulation: Start with a baseline mesh and run your simulation, ensuring the residuals converge to an acceptable value (e.g., 10⁻⁴) [9].

- Refine the Mesh: Globally refine your mesh (e.g., 1.5 times more elements) and run the simulation again [9].

- Compare Key Outputs: Compare the values of interest (e.g., drug concentration, flow rate) between the two simulations. If the difference is within your acceptable tolerance (e.g., <1%), the initial mesh is sufficient. If not, further refine until the solution stabilizes [9].

- Use Error Indicators: For complex geometries, use spatial error estimates (like Mises stress error indicators) to identify and refine only regions with high discretization error, creating a more efficient model [16].

FAQ 2: My experimental data for a drug-eluting implant shows inconsistent release rates. What could be the cause?

- Answer: Inconsistent release rates often stem from poorly controlled manufacturing or environmental parameters. A Design of Experiments (DOE) approach is crucial for identifying key variables. For an osmosis-driven implant, critical factors to investigate include [17]:

- Osmogen Concentration: The concentration of the osmotic agent directly drives the release rate.

- Membrane Pore Size: The size of the pores in the osmotic membrane controls the flow of the drug solution.

- Needle/Outlet Geometry: The dimensions of the perfusion needle can affect flow resistance. Systematically varying these parameters, as demonstrated in vitro with agarose gel, allows you to optimize the implant for a consistent, predictable flow rate [17].

FAQ 3: What are the primary advantages of using soft, flexible materials for brain implants over traditional rigid ones?

- Answer: Rigid neural probes cause a significant biological response that limits their long-term efficacy. They damage surrounding brain tissue, which the body then encapsulates with scar tissue. This scar layer insulates the probe from neurons, degrading signal quality and often requiring removal [18]. Soft implants (e.g., made from materials like Fleuron) are thousands to millions of times softer and more flexible. This dramatically reduces tissue damage and scar formation, leading to better biocompatibility, longer functional lifespan, and more accurate neural data recording or controlled drug delivery [18].

FAQ 4: How do I formulate a strong, answerable research question for a study on a new head injury treatment?

- Answer: A well-structured research question is the foundation of rigorous research. Use the PICOT framework for interventional studies or PECOT for observational studies to ensure all critical elements are included [19]:

- Population: The patient or subject group (e.g., adults with moderate traumatic brain injury).

- Intervention/ Exposure: The treatment or factor being studied (e.g., a novel drug-eluting implant).

- Comparator: The control or alternative (e.g., standard care or a placebo implant).

- Outcome: The measured result (e.g., cognitive test scores, tumor recurrence rate).

- Time: The relevant time frame (e.g., over 90 days). Furthermore, the question should pass the FINER criteria: it should be Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant [19].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: In Vitro Characterization of an Osmosis-Driven Brain Implant

This protocol outlines the methodology for testing a 3D-printed, dual-reservoir implant for localized drug delivery to the brain [17].

- Apparatus Setup: Use 0.2% agarose gel as a brain tissue analog in a controlled environment.

- Implant Loading: Load the implant's reservoirs with a drug analog (e.g., food dye) and an osmogen (e.g., sodium chloride at a specific concentration).

- Implantation: Anchor the implant within the agarose gel using its integrated needles.

- Data Collection: Monitor and record the release rate (e.g., µL/hour) and measure the diffusion distance (mm) of the dye in the gel over a set period.

- DOE Execution: Repeat the experiment varying key parameters (osmogen concentration, membrane pore size, needle length) according to a predefined design of experiments (DOE) matrix to model their effect on performance [17].

Protocol 2: Deep Brain Stimulation for Traumatic Brain Injury

This summarizes the clinical trial protocol for using deep brain stimulation (DBS) to treat chronic cognitive deficits from traumatic brain injury (TBI) [20].

- Patient Selection: Recruit participants with stable, long-term (>2 years) cognitive impairments from moderate to severe TBI.

- Preoperative Modeling: Create a virtual model of each patient's brain to precisely identify the target location within the central lateral nucleus of the thalamus.

- Surgical Implantation: Surgically implant the DBS device, guided by the virtual model, to ensure accurate electrode placement.

- Titration and Treatment: After surgery, begin a titration phase (e.g., 2 weeks) to optimize stimulation parameters. This is followed by a long-term treatment phase (e.g., 90 days, 12 hours per day).

- Outcome Assessment: Evaluate efficacy using standardized cognitive tests, such as the trail-making test, at baseline and after the treatment period [20].

Table 1: Performance Data of Osmosis-Driven Brain Implant from In Vitro Testing [17]

| Parameter | Optimized Value | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | 2.5 ± 0.1 µl/Hr | Determines the dosage of therapeutic agent delivered per unit time. |

| Diffusion Distance | 15.5 ± 0.4 mm | Indicates the coverage area of the drug within the brain tissue analog. |

| Osmotic Membrane Pore Size | 25 nm | Controls the permeability and flow resistance of the release mechanism. |

| Osmogen Concentration | 25.3% | Drives the osmotic pressure and thus the force behind drug delivery. |

Table 2: Clinical Trial Outcomes of Deep Brain Stimulation for Traumatic Brain Injury [20]

| Metric | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Average Improvement in Processing Speed | 32% | Far exceeded the target of 10%, indicating a significant cognitive recovery. |

| Performance Decline After Stimulation Withdrawal | 34% slower | Provides evidence that the cognitive benefits were directly linked to the active implant. |

| Number of Participants | 5 | Proof-of-concept study demonstrating feasibility and effect size for a larger trial. |

| Time Since Injury for Participants | 3 to 18 years | Shows potential for treating chronic, long-standing impairments. |

Research Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Research Workflow from Problem to Thesis

DBS Reactivates Cognitive Pathways After TBI

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Advanced Brain Implant Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Agarose Gel (0.2%) | Serves as a physiologically relevant brain tissue analog for in vitro testing of drug diffusion distance and release kinetics [17]. |

| Osmogen (e.g., NaCl) | The driving agent in osmosis-based implants; its concentration is a critical parameter controlling drug release rate [17]. |

| Fleuron Material | A novel, soft, photoresist polymer enabling high-density, flexible neural probes that minimize tissue damage and improve biocompatibility [18]. |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Device | An implantable pulse generator used to deliver precisely calibrated electrical stimulation to specific brain regions to modulate neural activity [20]. |

| Virtual Brain Model | Patient-specific computational models used to preoperatively plan and guide the precise surgical placement of brain implants [20]. |

| Trail-Making Test | A standardized neuropsychological assessment tool used as a primary outcome measure to evaluate cognitive processing speed and executive function [20]. |

h-refinement vs. p-refinement and Their Impact on Accuracy

Core Concept FAQs

What are h-refinement and p-refinement? h-refinement and p-refinement are two fundamental strategies used in Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to improve the accuracy of numerical solutions. h-refinement reduces the size of elements in the computational mesh, leading to a larger number of smaller elements. p-refinement increases the order of the polynomial functions used to approximate the solution within each element without changing the mesh itself [21]. A third approach, hp-refinement, combines both techniques and can achieve exponential convergence rates when appropriate estimators are used [22].

When should I use h-refinement versus p-refinement? The choice between h and p-refinement depends on the nature of your problem and the characteristics of the solution. h-refinement is more general and better suited for problems with non-smooth solutions, such as those involving geometric corners, bends, or singularities where stresses theoretically become infinite [21] [22]. p-refinement is particularly effective for problems with smooth solutions and is often preferred for addressing issues like volumetric locking in incompressible materials or shear locking in bending-dominated problems [21]. For optimal results, consider hp-refinement which adaptively combines both approaches [22].

How do refinement strategies impact computational cost and accuracy? Both refinement strategies balance computational cost against solution accuracy. h-refinement increases the total number of degrees of freedom (DoFs), which can significantly increase memory requirements and computation time, especially in 3D problems [23]. p-refinement increases the number of DoFs per element and the bandwidth of the system matrices, but may be more computationally efficient for achieving the same accuracy in problems with smooth solutions [24]. Importantly, all refinement strategies must consider round-off error accumulation, which increases with the number of DoFs and can eventually dominate the total error [23].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Lack of Convergence in Stresses Near Geometric Features

- Symptoms: Stresses continue to increase without converging when the mesh is refined around sharp corners or re-entrant edges.

- Root Cause: This indicates the presence of a geometric singularity where stresses are theoretically infinite. In these instances, no amount of mesh refinement will produce a converged stress value [21].

- Solution:

- Modify the geometry to include a small, realistic fillet radius instead of a perfect sharp corner [21].

- Apply h-refinement around the singularity, but assess convergence based on global energy norms or displacements rather than local stresses.

- Consider using specialized singular elements or a sub-modeling approach to isolate the singularity effect.

Problem: Volumetric or Shear Locking

- Symptoms: The model behaves unrealistically stiff, with significantly under-predicted displacements or deformations. This is common in incompressible materials (hyperelasticity, plasticity) or thin structures undergoing bending [21].

- Root Cause: Standard low-order elements struggle to model incompressible behavior or pure bending without generating artificial shear strains.

- Solution: Implement p-refinement. Switching to second-order (or higher) elements is typically effective at mitigating locking phenomena [21]. For incompressible problems, elements specifically formulated for incompressibility may be necessary.

Problem: Inefficient Error Reduction and High Computational Cost

- Symptoms: The error decreases very slowly despite aggressive refinement, leading to unsustainable computational costs.

- Root Cause: Using a uniform refinement strategy (especially h-refinement) across the entire domain, including areas where the solution is already accurate.

- Solution: Implement adaptive mesh refinement (AMR). AMR automatically refines the mesh only in regions where the estimated discretization error is highest [23] [25] [22]. The general adaptive procedure involves four steps:

Quantitative Comparison and Selection Guide

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of h-refinement and p-refinement

| Aspect | h-refinement | p-refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Reduces element size (h) [21] |

Increases element polynomial order (p) [21] |

| Suitable Problem Types | Non-smooth solutions, singularities, capturing local features [21] [22] | Smooth solutions, mitigating locking effects [21] [22] |

| Convergence Rate | Algebraic [22] | Exponential (for smooth solutions) [22] |

| Computational Overhead | Increases total number of elements/DoFs, impacts matrix assembly and solver time [23] | Increases integration points and matrix bandwidth per element [24] |

| Mesh Requirements | Can use simple linear elements; must manage quality during partitioning | Requires a mesh that can support higher-order shape functions |

| Handling of Singularities | Effective only if geometry is modified (e.g., with a fillet) [21] | Cannot resolve singularities alone |

Experimental Protocols for Convergence Analysis

Protocol 1: Conducting a Mesh Convergence Study

A systematic mesh convergence study is essential for validating your results and ensuring they are not dependent on the discretization [21].

- Define Quantity of Interest: Identify a key output parameter (e.g., maximum stress, tip displacement, natural frequency).

- Generate a Sequence of Meshes: Create at least three progressively finer meshes. These can be globally refined (h-refinement) or use increased polynomial order (p-refinement).

- Run Simulations: Execute the analysis for each mesh in the sequence.

- Calculate Relative Change: For each refinement level

i, calculate the relative change in the quantity of interest:Relative Change = |Q_i - Q_(i-1)| / |Q_(i-1)|. - Assess Convergence: Plot the quantity of interest against a measure of element size (e.g.,

h) or the number of DoFs. The solution is considered converged when the relative change between two successive refinements falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 1-5%) [21].

Table 2: Error Norms for Quantitative Convergence Measurement [21]

| Error Norm | Definition | Interpretation | Ideal Convergence Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L²-Norm Error | |u - u_h|_{L²} |

Measures error in displacements | O(h^(p+1)) |

|

| Energy-Norm Error | `|u - u_h | _H` | Related to the error in energy | O(h^p) |

Protocol 2: Implementing Adaptive Refinement (AMR)

For complex problems, adaptive refinement is more efficient than global refinement [23] [25] [22].

- Initial Solution: Solve the boundary value problem on an initial coarse mesh [22].

- Error Estimation: Compute a local error estimator for each element. This can be a residual-based estimator [22] or a recovery-based estimator.

- Element Marking: Select elements for refinement using a marking strategy (e.g., refine the top 30% of elements with the largest errors) [23] [22].

- Mesh Refinement: Refine the marked elements. For h-refinement, this involves subdividing elements [25]. Ensure mesh conformity during this process [22].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-4 until a global error estimate falls below a tolerance or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Figure 1: Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) Workflow. This iterative process automatically refines the mesh in regions of high error until convergence is achieved [25] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function in Discretization Error Research |

|---|---|

| A Posteriori Error Estimator | Quantifies the local and global discretization error, guiding where to refine the mesh [22]. |

| Mesh Generation Software | Creates the initial computational mesh (hexahedral, tetrahedral, prismatic) and enables its refinement [26] [27]. |

| hp-Adaptive FEM Solver | A finite element solver that supports both h- and p-refinement, often automatically [22]. |

| Method of Manufactured Solutions (MMS) | A verification technique where an analytical solution is predefined to calculate the exact error and validate the error estimator [22]. |

The Mesh Convergence Study: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Biomedical Models

In finite element analysis (FEA), the Quantity of Interest (QoI) is the specific result parameter you select to monitor during mesh convergence studies. This choice fundamentally determines the accuracy and reliability of your simulation results. The QoI serves as the benchmark for determining when your mesh is sufficiently refined, balancing computational cost with numerical accuracy. Selecting an appropriate QoI is particularly critical in biomedical applications—from cardiovascular stent design to traumatic brain injury research—where simulation results directly impact device safety and therapeutic outcomes.

Table: Common Quantities of Interest in Biomechanical FEA

| Quantity of Interest | Typical Applications | Convergence Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Displacement/Deflection | Structural mechanics, cantilever beams | Converges most rapidly with mesh refinement [28] |

| Maximum Principal Strain | Traumatic brain injury, soft tissue mechanics | Requires finer mesh; sensitive to distribution [29] |

| von-Mises Stress | Cardiovascular stents, implant durability | Convergence problems with coarse meshes [30] |

| Pressure Distribution | Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, blood flow | May converge at different rates than strain [29] |

| Natural Frequencies | Modal analysis, vibration studies | Generally less mesh-sensitive than stress [21] |

Troubleshooting Guide: QoI Selection Challenges

How do I select an appropriate Quantity of Interest for my specific research problem?

Problem Identification Researchers often struggle to identify which parameter best represents the physical phenomenon being studied, leading to inconclusive convergence studies or inaccurate results.

Solution Protocol

- Align with Research Objectives: Your QoI should directly correspond to your primary research question. For traumatic brain injury studies, maximum principal strain correlates with tissue damage and should be prioritized over displacement [29].

- Consider Physical Significance: In cardiovascular stent analysis, peak strain values at integration points serve as better QoIs for fatigue prediction than composite displacement metrics [31].

- Evaluate Sensitivity: Parameters with higher spatial gradients (stresses, localized strains) require more refined meshes than integrated values (total deformation, reaction forces) [32].

- Verify Practical Utility: Ensure your QoI can be validated experimentally or compared with analytical solutions where possible [21].

Why do my results fail to converge even with extensive mesh refinement?

Problem Identification Some QoIs, particularly stresses near geometric singularities, may never converge regardless of mesh refinement due to theoretical limitations.

Solution Protocol

- Identify Singularities: Sharp corners with zero radius generate theoretically infinite stresses. Recognize when non-convergence indicates a physical singularity rather than numerical error [32] [21].

- Apply Engineering Judgment: For sharp internal corners, the stress depends entirely on element size rather than physical reality. In these cases, model the actual specified radius from engineering drawings [32].

- Shift QoI Focus: When singularities are present, consider monitoring strain energy or displacements away from the singularity instead of local stresses [28].

- Implement Adaptive Refinement: Use advanced FEA capabilities that automatically refine mesh in high-gradient regions while maintaining coarser elements elsewhere [24].

How can I efficiently converge distributed parameters rather than single-point values?

Problem Identification Many biological phenomena involve distributed responses rather than isolated peak values, creating challenges for traditional convergence approaches.

Solution Protocol

- Extend Beyond Peak Values: For brain injury models, consider "response vectors" that account for both magnitude and distribution of strain across deep white matter regions [29].

- Implement Statistical Measures: Population-based median strain values across entire brain elements provide more robust convergence metrics than isolated maximum values [29].

- Adopt Multi-scale Approaches: Use submodeling techniques where a global model identifies critical regions, and local refined submodels provide detailed stress distributions [31].

- Leverage Error Norms: Utilize L2-norm and energy error norms that provide averaged errors over entire structures rather than point values [21].

Experimental Protocols for QoI Convergence Studies

Standardized Mesh Convergence Methodology

Mesh Convergence Workflow

Initial Mesh Generation

Systematic Refinement Procedure

- Refine mesh globally or in regions of interest, typically reducing element size by 1.5-2x between steps

- Maintain consistent element quality during refinement

- For cardiovascular stents, use consistently refined meshes to properly characterize discretization impact [31]

QoI Monitoring and Calculation

Advanced Convergence Techniques for Complex Geometries

Local Refinement Strategy

Localized Refinement Strategy

Element Technology Selection

- Choose between reduced integration (C3D8R) and enhanced full-integration (C3D8I) elements based on application

- For brain models, enhanced full-integration elements serve as benchmarks immune to hourglass locking [29]

- Monitor hourglass energy when using reduced integration elements (<10% of internal energy typically recommended) [29]

Adaptive Refinement Approaches

- Utilize p-refinement (increasing element order) as alternative to h-refinement (reducing element size)

- For fiber network materials, implement length-based adaptive h-refinement strategies [24]

- Consider mixed approaches where p-refinement addresses locking issues while h-refinement captures geometric features [21]

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between mesh convergence and validation?

Mesh convergence verifies that your numerical model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model by reducing discretization error, while validation confirms that your mathematical model correctly represents physical reality. Convergence ensures you're getting the right answer to your equations; validation ensures you're solving the right equations for your physical problem [30]. Both are essential for credible simulations.

How many mesh refinement steps are typically required?

At least three systematically refined meshes are necessary to plot a meaningful convergence curve and identify trends [32] [21]. However, if two successive refinements produce nearly identical results (<1% change in QoI), convergence may be assumed without additional steps. For publication-quality research, multiple refinement steps providing clear convergence behavior are recommended.

Can I use the same mesh density for different load magnitudes?

No, increased load magnitudes typically increase stress gradients, requiring finer meshes for comparable accuracy relative to material strength limits [32]. A mesh that provides sufficient accuracy for linear elastic analysis may be inadequate for plastic deformation analysis under higher loads, even with identical geometry.

How do I handle non-converging stresses at geometric singularities?

First, distinguish between physical stress concentrations and numerical singularities. For sharp corners with zero radius, stresses are theoretically infinite. Model the actual manufactured radius instead of idealizing sharp corners. If sharp corners are unavoidable, base design decisions on stresses away from the singularity following St. Venant's principle [32] [33].

Research Reagent Solutions: FEA Computational Tools

Table: Essential Numerical Tools for Mesh Convergence Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in QoI Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Element Formulations | C3D8I (enhanced full integration), C3D8R (reduced integration) | Control hourglassing, volumetric locking; affect strain accuracy [29] |

| Refinement Methods | h-refinement, p-refinement, adaptive refinement | Systematically reduce discretization error in QoI [24] [21] |

| Convergence Metrics | Fractional change (%), L2-norm, energy error norm | Quantify difference between successive refinements [31] [21] |

| Quality Measures | Aspect ratio, skew, warpage, Jacobian | Ensure element geometry doesn't adversely affect results [29] |

| Hourglass Controls | Relax stiffness, enhanced hourglass control | Mitigate zero-energy modes in reduced integration elements [29] |

Selecting appropriate quantities of interest represents the foundation of reliable mesh convergence research. The most effective QoIs directly reflect your research objectives, exhibit measurable convergence behavior, and align with physically meaningful phenomena. By implementing the systematic approaches outlined in this guide—including standardized refinement protocols, localized mesh strategies, and comprehensive verification techniques—researchers can significantly enhance the credibility of their computational simulations while optimizing computational resource utilization.

Question: I am performing a finite element analysis to model a new polymer-based drug delivery tablet. My initial results seem to change when I refine the mesh. How many data points do I need to create a reliable convergence curve to ensure my results are accurate?

Answer: For a reliable convergence curve, you need a minimum of three data points (mesh refinements). However, using four or more points is highly recommended to confidently identify the trend and confirm that your solution has stabilized [34] [21].

The core of a mesh convergence study is to refine your mesh systematically and plot a key result (like a critical stress or displacement) against a measure of mesh density. The point where this result stops changing significantly with further refinement indicates that your solution has converged [35] [34].

The table below summarizes the purpose and value of using different numbers of data points.

| Number of Data Points | Purpose and Sufficiency |

|---|---|

| Minimum 3 Points | Establishes a basic trend line. Allows you to see if the quantity of interest is beginning to plateau. Considered the bare minimum [21] [34]. |

| Recommended 4+ Points | Provides a more reliable curve. Helps distinguish a true asymptotic convergence from a temporary plateau and builds greater confidence that the solution has stabilized [34]. |

Your Experimental Protocol for a Convergence Study

Follow this detailed methodology to create your convergence curve and verify mesh independence.

- Identify Your Quantity of Interest: Before you begin, select the specific result you want to converge. This is often the maximum stress in a critical region, maximum displacement, or strain energy [30] [34].

- Create a Series of Meshes: Generate at least three to four different meshes for your model with increasing levels of refinement.

- Start with a relatively coarse mesh that captures the basic geometry.

- For each subsequent simulation, refine the mesh by reducing the global element size or increasing the number of element divisions [35].

- Focus on critical areas: Use local mesh refinement in regions with high stress gradients, complex geometry, or where your quantity of interest is located. You do not need to refine the entire model, but ensure a smooth transition from fine to coarse mesh areas [21] [4] [34].

- Run Simulations and Record Data: Solve your model for each mesh level. Record the value of your quantity of interest and a measure of mesh density, such as the number of elements or degrees of freedom in the model [35].

- Plot the Convergence Curve and Analyze: Create a plot with mesh density on the x-axis and your quantity of interest on the y-axis. Analyze the curve to find the point where the result stabilizes. The solution is considered converged when the difference between two successive refinements is less than a pre-defined tolerance (e.g., 1-5%) [9] [31].

For a visual guide, the workflow below outlines the core steps of this iterative process.

Research Reagent Solutions: Your FEA Convergence Toolkit

In the context of FEA, the "reagents" are the software tools and numerical inputs required for your study.

| Tool / Parameter | Function in Convergence Analysis |

|---|---|

| FEA Software (e.g., ANSYS, COMSOL) | Provides the environment for geometry creation, meshing, solving, and result processing. Modern software often includes automatic mesh refinement and convergence monitoring tools [4] [36]. |

| Constitutive Material Model | Defines the mathematical relationship between stress and strain for your material. Accurate models (e.g., Drucker-Prager for powders) are crucial for credible results in pharmaceutical simulations [37]. |

| Local Mesh Refinement | A technique to apply finer mesh only in regions of interest (e.g., sharp corners, high stress gradients), optimizing computational cost and accuracy [21] [4]. |

| Tolerance Criteria | A user-defined threshold (e.g., 1-5% change in results between meshes) that quantitatively defines when convergence is achieved [9] [31]. |

Important Troubleshooting Notes

- Singularities: Be cautious of geometric singularities (e.g., perfectly sharp corners). In these regions, stress will theoretically be infinite and will keep increasing with mesh refinement, making convergence impossible. The solution is to model a small, realistic radius instead [21] [34].

- Element Type: The order of your elements matters. Second-order (quadratic) elements often converge faster and more accurately than first-order (linear) elements, especially for problems involving bending or incompressibility [21] [38].

- Don't Use Element Size Alone: A mesh that was converged for one model may not be converged for another, even if the element size is the same. Stress gradients and loading conditions also affect convergence. Always perform a study for each new model or significant load case [34].

Conceptual Foundations: Discretization Error and Mesh Convergence

In simulations using the Finite Element Method (FEM), discretization is the process of decomposing a complex physical system with an unknown solution into smaller, finite elements whose behavior can be approximately described [39]. The discretization error is the difference between this numerical approximation and the true physical solution.

Mesh convergence is the process of iteratively refining this mesh until the solution stabilizes to a consistent value, indicating that further refinement does not significantly improve accuracy [4] [39]. The goal is to find a middle ground: a mesh fine enough to provide reliable results but as coarse as possible to conserve computational resources like time and memory [39].

Local mesh refinement is a powerful technique within this process. Instead of uniformly refining the entire model, computational resources are focused on critical areas of interest, such as regions with high stress gradients, complex geometry, or sharp corners [4]. This targeted approach maximizes efficiency without sacrificing the accuracy of the overall solution.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Mesh Convergence Issues

This section addresses specific challenges researchers might encounter when performing mesh convergence studies.

FAQ 1: My solution does not appear to be converging, even with a very fine mesh. The results keep changing. What could be wrong?

- Probable Cause: This could indicate a stress singularity, a numerical artifact rather than a real physical phenomenon [4]. Singularities occur at points where the geometry creates a theoretical infinite stress, such as sharp re-entrant corners, point loads, or where boundary conditions change abruptly. The mesh cannot accurately capture this, leading to unreasonably high and non-converging stress values.

- Solution:

- Identify: Carefully examine the locations of high stress. If they are confined to single points at geometric singularities, they are likely numerical artifacts [4].

- Mitigate: Implement a small geometric fillet (round) at sharp corners to create a more physical stress distribution.

- Evaluate: Use the stress results at a reasonable distance away from the singularity, as predicted by Saint-Venant's principle.

- Smooth: Leverage software tools like stress smoothing to better represent the stress fields around these points [4].

FAQ 2: My model is too large, and running multiple convergence iterations is computationally prohibitive. How can I proceed?

- Probable Cause: Attempting to perform global mesh refinement on a large-scale model for every convergence check is inherently resource-intensive.

- Solution: Implement a sequential local mesh refinement strategy [40].

- Start by solving the problem on a coarse global mesh.

- Use error estimators to identify specific subdomains with high solution errors or non-linear behavior (e.g., high saturation fronts in flow problems) [40].

- Refine the mesh only within these critical regions.

- Use the coarse mesh solution as an initial guess for the refined mesh problem to accelerate convergence in the non-linear solver [40].

- This approach can achieve significant speedups (e.g., 25 times) compared to global refinement [40].

FAQ 3: How do I know when my mesh is "good enough," and what should I monitor?

- Probable Cause: Uncertainty in the mesh convergence process and selecting the wrong metric to monitor.

- Solution:

- Select Monitoring Points: Choose specific points or regions in your model that are critical to your analysis. Ensure these are geometrically defined or use surface result points so their location is consistent across mesh refinements [39].

- Monitor the Right Quantities: Displacements and global forces typically converge first. Stresses and strains are higher-order results and require a finer mesh to converge [39]. Always monitor the maximum stress in your area of interest.

- Set a Convergence Criterion: Define a threshold for the relative change in your monitored results between successive mesh refinements. A common target is a change of less than 1-2% [39].

Experimental Protocol for a Mesh Convergence Study

The following workflow provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for conducting a robust mesh convergence study.

Diagram 1: Mesh Convergence Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Model Definition: Begin with a fully defined simulation model, including geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, and loads.

- Initial Coarse Mesh: Generate an initial mesh with a global element size that is relatively coarse to obtain a quick, approximate solution [40].

- Initial Simulation Run: Solve the model using this coarse mesh.

- Result Extraction: Record the key results of interest at specific monitoring points. These typically include:

- Local Mesh Refinement: Analyze the solution to identify critical regions (e.g., areas of maximum stress, high gradients, or complex geometry). Apply local mesh refinement only to these areas [4] [40].

- Subsequent Simulation Run: Solve the model again with the locally refined mesh.

- Result Comparison and Convergence Check: Compare the results from the current and previous simulations at the monitoring points. Calculate the relative change for each key result.

- Iterate or Conclude: If the change in all key results is below a predefined tolerance (e.g., 1-2%), the solution has converged [39]. If not, return to Step 5 and further refine the mesh, focusing on the areas that still show significant change.

Quantitative Data for Mesh Convergence

The tables below summarize typical quantitative data from mesh convergence studies, providing a reference for evaluating your own results.

Table 1: Example Convergence Data for Cantilever Deflection [39]

| Mesh Element Type | Target Element Size (mm) | Deflection at End (mm) | Relative Change vs. Previous (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beam (Bernoulli) | N/A | 7.145 | N/A |

| Beam (Timoshenko) | N/A | 7.365 | N/A |

| Surface (Quadrilateral) | 20.0 | 6.950 | N/A |

| Surface (Quadrilateral) | 10.0 | 7.225 | 3.96% |

| Surface (Quadrilateral) | 5.0 | 7.315 | 1.25% |

| Surface (Quadrilateral) | 2.5 | 7.350 | 0.48% |

Note: The surface model results converge towards the Timoshenko beam solution, which accounts for shear deformation.

Table 2: Example Convergence Data for Plate Stress/Strain [39]

| Target FE Element Length (m) | First Principal Stress (MPa) | Relative Stress Change (%) | First Principal Strain | Relative Strain Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.500 | 105.5 | N/A | 0.000550 | N/A |

| 0.100 | 118.2 | 12.04% | 0.000615 | 11.82% |

| 0.050 | 121.1 | 2.45% | 0.000628 | 2.11% |

| 0.010 | 122.5 | 1.16% | 0.000635 | 1.11% |

| 0.005 | 122.7 | 0.16% | 0.000636 | 0.16% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key "reagents" or essential components in the computational experiment of a mesh convergence study.

Table 3: Essential Components for a Mesh Convergence Study

| Item | Function in the Computational Experiment |

|---|---|

| FE Software (e.g., Ansys, RFEM) | The primary environment for geometry creation, material definition, meshing, solving, and result extraction [4] [39]. |

| Error Estimators | Algorithms that provide a quantitative measure of the spatial and temporal discretization error, guiding where to refine the mesh [40]. |

| Local Mesh Refinement Tool | A software feature that allows for targeted increases in mesh density in user-defined or algorithmically-determined regions of interest [4]. |

| Convergence Metric | A predefined quantity (e.g., displacement, stress) and a tolerance (e.g., 1% relative change) used to objectively determine when the solution has stabilized [39]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary computational resources (CPU/GPU power, memory) to solve multiple iterations of increasingly refined models in a reasonable time. |

Advanced Algorithm for Sequential Local Refinement

For complex non-linear problems (e.g., multiphase flow), a more sophisticated algorithm that separates temporal and spatial adaptivity can be implemented for maximum efficiency [40]. The following diagram illustrates this advanced workflow.

Diagram 2: Advanced Sequential Refinement

Key Aspects of the Algorithm:

- Separate Estimators: The algorithm uses two distinct error estimators: one for spatial discretization error and another for temporal discretization error [40].

- Targeted Refinement: This separation allows the solver to independently refine the time steps in regions with high temporal variation (e.g., a saturation front) and the spatial mesh in regions with high spatial gradients [40].

- Optimized Initial Guess: After each refinement, the solution from the previous, coarser mesh is projected onto the new mesh to provide a high-quality initial guess for the non-linear solver, significantly accelerating convergence [40].

- Computational Efficiency: This approach prevents over-refinement and can lead to orders-of-magnitude speedup compared to using uniformly fine meshes and time steps across the entire model [40].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most common root cause when a mesh refinement study fails to show convergence? A failed convergence is most often due to the presence of a geometric singularity in the model, such as a sharp re-entrant corner, which creates a stress (or other field quantity) that theoretically goes to infinity. Successive mesh refinements at this singularity will prevent convergence. Other common causes include insufficient element order and inadequate resolution of boundary layers.

Q2: How do I distinguish between a discretization error problem and a model formulation error? A discretization error will typically manifest as a smooth change in the solution output as the mesh is refined. A model formulation error, such as an incorrect material property or boundary condition, will often persist regardless of mesh density. Conducting a verification test against a known analytical solution can help isolate the issue to the discretization.

Q3: My solution oscillates between mesh refinements instead of monotonically approaching a value. What does this indicate? Oscillatory behavior often indicates a problem with mesh quality or stability of the numerical scheme. Check for highly skewed elements or sudden large changes in element size. For non-linear problems, it can also suggest that the solver tolerances need to be tightened.

Q4: For a complex anatomical model, what is a practical criterion for stopping mesh refinement? A practical stopping criterion is the "relative change threshold." When the relative change in your key output metrics (e.g., peak stress, average flow) between two successive mesh refinements falls below a pre-defined tolerance (e.g., 2-5%), the solution can be considered mesh-converged for that context of use.

Q5: How does the model's "Context of Use" influence the required level of mesh convergence? The required level of convergence is directly informed by the model risk, which is a combination of the decision consequence and the model influence [41]. A high-stakes decision, such as predicting a safety-critical event, will demand a much stricter convergence threshold than a model used for early-stage conceptual exploration.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Residuals Stagnate After Mesh Refinement

Symptoms:

- The solver residuals stop decreasing after an initial drop.

- Key output parameters do not change with further mesh refinement.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Mesh Quality | Identify and repair highly distorted elements (skewness > 0.9, excessive aspect ratio). |

| 2 | Verify Material Model Continuity | Ensure material properties (e.g., hyperelastic model) are physically realistic and numerically stable. |

| 3 | Inspect Boundary Conditions | Confirm that applied loads and constraints are consistent with the physiology and do not create numerical singularities. |

| 4 | Enable Solution Adaptation | Use built-in error estimators to guide local (rather than global) mesh refinement in high-error regions. |

Problem: Abrupt Solution Jump with Local Refinement

Symptoms:

- A significant, unexpected change in the solution occurs when applying local mesh refinement in a specific region.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Refinement Zone Geometry | Ensure the refinement region is correctly defined and does not introduce artificial geometric features. |

| 2 | Check for "Over-refinement" | Excessively small elements adjacent to coarse ones can cause ill-conditioning; use a smoother size transition. |

| 3 | Re-run with Global Refinement | Compare the result to isolate if the jump is due to the local refinement or an underlying model issue. |

| 4 | Verify Interpolation Methods | Confirm that data mapping between meshes (e.g., for fluid-structure interaction) is accurate and conservative. |

Problem: Solver Fails on Finest Mesh

Symptoms:

- The simulation runs successfully on coarse meshes but fails due to memory or convergence errors on the finest mesh.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Monitor System Resources | Use system monitoring tools to confirm the failure is due to RAM exhaustion. |

| 2 | Switch to Iterative Solver | For large linear systems, use an iterative solver (e.g., Conjugate Gradient) with a good pre-conditioner to reduce memory usage. |

| 3 | Implement Multi-Grid Method | Use a multi-grid solver to accelerate convergence on very fine meshes. |

| 4 | Consider Model De-coupling | If possible, solve a simplified or sub-model to obtain the needed result, reducing the overall problem size. |

Quantitative Convergence Data

The following data summarizes a mesh convergence study for a representative cardiac electrophysiology model, a common type of complex anatomical model in pharmaceutical research [41].

Table 1: Mesh Convergence Study for Ventricular Action Potential Duration (APD90)

| Mesh Name | Number of Elements (millions) | Average Element Size (mm) | Computed APD90 (ms) | Relative Error vs. Finest Mesh (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extra-Coarse | 0.15 | 1.50 | 288.5 | 4.12% |

| Coarse | 0.85 | 0.85 | 295.1 | 1.86% |

| Medium | 2.10 | 0.60 | 298.3 | 0.83% |

| Fine | 5.50 | 0.40 | 300.1 | 0.23% |

| Extra-Fine | 12.00 | 0.28 | 300.8 | - |

Table 2: Credibility Assessment and Recommended Actions

| Observed Convergence Behavior | Credibility Assessment | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth, monotonic change in output with refinement. | High Credibility. Suggests numerical results are reliable for this Context of Use. | Document the convergence trend and final relative error. The "Medium" or "Fine" mesh may be sufficient. |

| Output oscillates or changes erratically. | Low Credibility. Results are not reliable for decision-making. | Investigate mesh quality, solver settings, and model stability. A fundamental review of the model setup is required. |

| Convergence is achieved but required an unexpectedly fine mesh. | Credibility depends on risk. The model may be capturing a critical local phenomenon. | Justify the computational expense via a formal risk-based analysis of the decision consequence [41]. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Mesh Refinement Study

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing a mesh convergence study, a critical component of model verification and credibility assessment [41].

1. Define the Context of Use (COU) and Quantities of Interest:

- Clearly state the purpose of the model and the specific key outputs (e.g., peak stress in a specific tissue, average flow rate through a valve).

- Define the acceptable level of error for these outputs based on the model's risk and the consequences of the decision it will inform [41].

2. Generate a Sequence of Meshes:

- Create at least 4-5 different meshes with a systematic increase in refinement. This can be global refinement (increasing elements everywhere) or local refinement (targeting regions with high solution gradients).

- For each mesh, record the characteristic element size and total number of elements/nodes (see Table 1).

3. Execute Simulations and Extract Data:

- Run the simulation for each mesh in the sequence using identical solver settings, boundary conditions, and material properties.

- Extract the pre-defined Quantities of Interest from the results of each simulation.

4. Calculate Relative Error:

- Treat the solution from the finest mesh as the reference "exact" solution.

- For each coarser mesh, calculate the relative error for each Quantity of Interest using the formula: ( \text{Relative Error} = \frac{|\text{Mesh Value} - \text{Finest Mesh Value}|}{|\text{Finest Mesh Value}|} \times 100\% )

5. Analyze Convergence Trend:

- Plot the relative error against the characteristic element size (or number of degrees of freedom) on a log-log scale.

- A straight-line trend on this plot indicates systematic convergence. The slope of the line is related to the order of accuracy of the numerical method.

6. Determine Convergence Status:

- Assess if the relative error for your key outputs has fallen below the acceptable threshold defined in Step 1.

- The solution is considered converged for the given COU when this threshold is met.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Convergence Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Mesh Generation Software (e.g., ANSYS ICEM CFD, Gmsh, Simvascular) | Creates the computational mesh (grid) that discretizes the complex anatomical geometry into finite elements or volumes. |

| Finite Element / Volume Solver (e.g., FEBio, OpenFOAM, Abaqus, COMSOL) | Solves the underlying system of partial differential equations on the generated mesh to compute the field quantities (stress, flow, electrical potential). |

| Solution-Based Error Estimators | Automated tools within solvers that calculate local error fields (e.g., energy norm error) to guide adaptive mesh refinement. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary computational power (CPU/GPU cores, large RAM) to solve the large linear systems arising from fine meshes. |

| Post-Processing & Scripting Tools (e.g., Paraview, MATLAB, Python with NumPy/Matplotlib) | Extracts key results, automates the calculation of relative errors, and generates convergence plots from the simulation output data. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

What is a Mesh Convergence Study and Why is it Critical?

A mesh convergence study is a systematic process used in computational analysis to ensure that the results of a simulation are not significantly affected by the size of the mesh elements. In Finite Element Analysis (FEA), the physical domain is divided into smaller, finite-sized elements to calculate approximate system behavior. The solution from FEA is an approximation that is highly dependent on mesh size and element type [42]. The core purpose of a convergence study is to find a mesh resolution where further refinement does not meaningfully alter the results, thereby increasing confidence in the accuracy of the numerical results and supporting sound engineering decisions [43] [42].

Discretization error is the error introduced when a continuous problem is approximated by a discrete model, representing a major source of inaccuracy in computational processes [44]. This error arises inherently when a mathematically continuous theory is converted into an approximate estimation within a computational model [44]. A mesh convergence study is the primary method for quantifying and minimizing this error.

How Do I Perform a Formal Mesh Convergence Study?

The formal method for establishing mesh convergence requires plotting a critical result parameter (such as stress at a specific location) against a measure of mesh density [43]. Follow this detailed workflow:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Select a Critical Result Parameter: Identify a key output variable that is critical to your design objectives. This is typically a maximum stress value in static stress analysis, but could also be displacement, temperature, or other field variables relevant to your simulation [43].

Create Initial Mesh: Generate an initial mesh with a reasonable level of refinement. This serves as your baseline.

Run Simulation and Record Results: Execute the analysis and record the value of your critical parameter from this first run.

Systematically Refine the Mesh: Increase the mesh density, particularly in regions of interest with high stress gradients. The refinement should involve splitting elements in all directions [43]. For local stress results, you can refine the mesh only in the regions of interest while retaining a coarser mesh elsewhere, provided transition regions are at least three elements away from the region of interest when using linear elements [43].

Repeat Solving and Data Collection: Run the analysis again with the refined mesh and record the new value of your critical parameter.

Check Convergence Criteria: Calculate the relative change in your critical parameter between successive mesh refinements. A common criterion is to continue until the relative change falls below a predetermined tolerance (e.g., 2-5%).

Plot Convergence Curve: Plot your critical result parameter against a measure of mesh density (like number of elements or element size) after at least three refinement runs. Convergence is achieved when the curve flattens out, approaching an asymptotic value [43] [42].

What Quantitative Criteria Define a Converged Solution?

A solution is considered converged when the results stabilize and do not change significantly with further mesh refinement. The following table summarizes the key quantitative criteria and methods:

Table 1: Quantitative Methods for Assessing Mesh Convergence

| Method | Description | Convergence Criterion | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Result Parameter Stability | Monitoring the change of a critical result (e.g., stress) with mesh refinement [43]. | Relative change between refinements is below a defined tolerance (e.g., <2%) [43]. | Static stress analysis, general FEA. |

| Asymptotic Approach | Plotting results against mesh density to observe the curve approaching a horizontal asymptote [42]. | The result parameter reaches a stable asymptotic value [42]. | All analysis types, provides visual confirmation. |

| H-Method | Refining the mesh by increasing the number of simple (often first-order) elements [42]. | Further refinement does not significantly alter the results [42]. | Predominantly used in Abaqus; not suitable for singular solutions [42]. |

| P-Method | Keeping elements minimal but increasing the order of the elements (e.g., 4th, 5th order) [42]. | The nominal stress quickly reaches its asymptotic value by changing the element order [42]. | Computationally efficient for certain problems [42]. |

What Are Common Pitfalls and Bad Practices to Avoid?

Even with a structured approach, researchers often encounter these common pitfalls:

- Using Element Size as the Sole Measure: Assuming a mesh is convergent because it has the same element size as a converged mesh from a different, non-similar model is not valid. Stress accuracy depends more on the element's proximity to stress concentrations and the local stress gradients than on a universal element size [43].

- Ignoring Geometry Representation: A common error is modeling internal sharp corners with zero radius. As the mesh refines, the calculated stress will increase without limit because the theoretical stress concentration is infinite for this geometry. The actual radius specified in the design must be modeled with a sufficient number of elements to predict valid elastic stresses [43].

- Incorrectly Extending Convergence Findings: The results of a local convergence study can only be extended to corresponding locations in structurally similar models with similar loadings and stress gradients. A strengthened structure or a simple increase in load magnitude can create higher stress gradients, requiring increased mesh density for comparable accuracy [43].

- Neglecting Computational Trade-offs: Achieving mesh convergence can be computationally expensive as it requires multiple iterations. It is essential to use engineering judgment and company guidelines to balance mesh refinement with computational resources [42].

How is Convergence Different for Nonlinear and Dynamic Problems?

For nonlinear problems (involving material, boundary, or geometric nonlinearities), the convergence of the numerical solution becomes more complex. The equilibrium equation for a nonlinear model does not have a unique solution, and the solution depends on the entire load history [42].

Protocol for Nonlinear Convergence:

- Load Stepping: Break the total applied load into small incremental loads [42].

- Iteration: Within each load increment, perform several iterations to find an approximate equilibrium solution. Newton-Raphson and Quasi-Newton techniques are common robust iterative methods [42].

- Tolerances: Specify tolerances for residuals and errors. A solution is found for an iteration when the residual force

R = P - Iis less than the specified tolerances [42].

For dynamic simulations (e.g., structural vibrations, impact analysis), time integration accuracy is crucial. The size of the time step must be small enough to capture all relevant phenomena occurring in the analysis. Use software parameters to control time integration accuracy, such as half-increment residual tolerance. Higher-order time integration methods (implicit/explicit Runge-Kutta) can be used for higher accuracy at a higher computational cost [42].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Convergence Analysis

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Their Functions in Convergence Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Convergence Analysis |

|---|---|

| h-Element FEA Solver (e.g., Abaqus Standard) | Solves the discretized system; accuracy is improved by increasing the number of elements (H-method) [42]. |

| p-Element FEA Solver (e.g., Pro Mechanica) | Converges on a result by increasing the order of elements within a minimal mesh, largely reducing dependency on element size [43]. |

| Mesh Refinement Tool | Automates the process of subdividing elements in regions of interest for the convergence study. |

| Convergence Criterion (Tolerance) | A user-defined value (e.g., 2% change in max stress) that quantitatively defines when convergence is achieved. |

| Post-Processor & Plotting Software | Used to extract critical result parameters and generate convergence curves plotting results vs. mesh density [43]. |

Overcoming Common Pitfalls: Singularities, Locking, and Element Selection

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the fundamental difference between a stress singularity and a stress concentration? A stress singularity is a point where the stress does not converge to a finite value; it theoretically becomes infinite with continued mesh refinement. In contrast, a stress concentration is a localized peak stress that will converge to a specific, finite value with a sufficiently refined mesh [45] [46].

- My model has a sharp, re-entrant corner. The stresses keep increasing as I refine the mesh. Is this a singularity? Yes, this is a classic geometric singularity [45] [46]. In reality, no corner is perfectly sharp, and the singularity is an artifact of the idealized geometry. Modeling a small fillet radius converts the singularity into a manageable stress concentration [46].

- When can I safely ignore a stress singularity in my results? You can ignore singularities if you are only interested in stresses in regions far away from the singular point, as governed by Saint-Venant's Principle [47] [46]. However, you should not ignore the outcomes in the immediate region of the singularity, as high stresses do exist there and are often the point of failure [47].

- How does material nonlinearity affect singularities? Using a nonlinear, elastic-plastic material model is an effective strategy. The stress at the singularity will be limited by the material's yield strength, preventing the unphysical "infinite" stress and providing a more realistic result [47] [46].

- Why is accurate stress concentration analysis critical for fatigue life prediction? Fatigue life is highly sensitive to local stress levels. The table below illustrates how an inaccurate, non-converged stress value can lead to a non-conservative and significantly overestimated fatigue life [45].

| Mesh Density (Elements on 45° arc) | Peak Stress (psi) | Predicted Fatigue Life (Cycles) |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse (2 elements) | 57,800 | >1,000,000 |

| Medium (6 elements) | 63,700 | 315,000 |

| Converged (10+ elements) | 65,600 | 221,000 |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Mesh Convergence and Singularity Issues

Problem: Stresses at a geometric feature (e.g., a sharp corner) do not converge and keep increasing with mesh refinement.

Objective: To implement a structured workflow to distinguish between a stress singularity and a stress concentration, and to apply appropriate strategies to obtain physically meaningful results.

Required Tools: Your standard Finite Element Analysis software with linear and nonlinear solvers.

Methodology: Follow the diagnostic and resolution workflow below to systematically address convergence issues.

Experimental Protocol: Performing a Mesh Convergence Study