Mastering Sensitivity Analysis for Parameter Uncertainty in Clinical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sensitivity analysis for parameter uncertainty, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mastering Sensitivity Analysis for Parameter Uncertainty in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sensitivity analysis for parameter uncertainty, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of why sensitivity analysis is a critical component of robust scientific and clinical research, moving into detailed methodological approaches including global versus local techniques and practical implementation steps. The guide further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and concludes with essential validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different methods. By synthesizing current best practices and regulatory perspectives, this resource aims to enhance the credibility, reliability, and interpretability of model-based inferences in biomedical research.

What is Parameter Uncertainty and Why Does Sensitivity Analysis Matter?

Parameter uncertainty is a fundamental concept in pharmacometrics and clinical modeling, representing the imperfect knowledge about the fixed but unknown values of parameters within a mathematical model [1]. In model-informed drug development (MIDD), it is crucial to distinguish parameter uncertainty (also known as second-order uncertainty) from stochastic uncertainty (first-order uncertainty), which describes the natural variability between individual patients or experimental units [1]. Accurately quantifying and accounting for parameter uncertainty is essential for robust parameter estimation, reliable model predictions, and informed decision-making in drug development and regulatory submissions [2] [1].

The assessment of parameter uncertainty becomes particularly critical when working with limited datasets, which regularly appear in pharmacometric analyses of special patient populations or rare diseases [2] [3]. Failure to adequately account for this uncertainty can lead to overconfidence in model predictions, suboptimal resource allocation, and biased estimation of the value of collecting additional evidence [1].

Parameter uncertainty arises from multiple sources throughout the drug development pipeline. Understanding these sources is essential for selecting appropriate quantification methods and interpreting results correctly.

Fundamental Definition and Context

In health economic and pharmacometric models, parameter uncertainty refers to the imprecision in estimating model parameters from available data [1]. This differs fundamentally from stochastic uncertainty, which describes inherent biological variability between individuals. While parameter uncertainty can theoretically be reduced by collecting more data, stochastic uncertainty represents an inherent property of the system being modeled [1].

Limited Sample Sizes: Small datasets (n ≤ 10) regularly encountered in analyses of special patient populations or rare diseases represent a significant source of parameter uncertainty [2] [3]. In such cases, standard methods like standard error (SE) and bootstrap (BS) fail to adequately characterize uncertainty [2].

Experimental Noise: In high-throughput drug screening, the absence of experimental replicates makes it impossible to correct for experimental noise, resulting in uncertainty for estimated drug-response metrics such as IC50 values [4].

Model Specification Uncertainty: The choice of parametric distributions to describe individual patient variation introduces uncertainty in the distribution parameters themselves, particularly when these parameters are correlated [1].

Extrapolation Uncertainty: In dose-response modeling, extrapolating beyond tested concentration ranges introduces significant uncertainty, often unaccounted for in quality control metrics [4].

Table 1: Classification of Parameter Uncertainty Sources in Pharmacometric Models

| Uncertainty Category | Description | Typical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size Limitations | Insufficient subjects for precise parameter estimation | Overconfident confidence intervals; biased parameter estimates [2] |

| Experimental Variance | Measurement error and technical noise in data collection | Inaccurate drug-response metrics (e.g., IC50, AUC) [4] |

| Distributional Uncertainty | Uncertainty in parameters of distributions describing stochastic uncertainty | Incorrect characterization of patient heterogeneity [1] |

| Extrapolation Uncertainty | Uncertainty when predicting outside observed data ranges | Poor generalization of model predictions [4] |

Quantitative Assessment of Parameter Uncertainty

Various statistical methods have been developed to quantify parameter uncertainty, each with distinct strengths and limitations depending on dataset characteristics and model complexity.

Methodological Approaches for Uncertainty Quantification

Log-Likelihood Profiling-Based Sampling Importance Resampling (LLP-SIR): This recently developed technique combines proposal distributions from log-likelihood profiling with sampling importance resampling, demonstrating superior performance for small-n datasets (≤10 subjects) compared to conventional methods [2].

Gaussian Processes for Dose-Response Modeling: A probabilistic framework that quantifies uncertainty in dose-response curves by modeling experimental variance and generating posterior distributions for summary statistics like IC50 and AUC values [4].

Non-Parametric Bootstrapping: This approach repeatedly resamples the original dataset with replacement to construct an approximate sampling distribution of statistics of interest, preserving correlation among parameters without distributional assumptions [1].

Multivariate Normal Distributions (MVNorm): This method assumes parameters follow a multivariate Normal distribution, defined by parameter estimates and their variance-covariance matrix, valid for sufficiently large sample sizes according to the Central Limit Theorem [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Parameter Uncertainty Methods for Small Datasets

| Method | Key Principle | Optimal Use Case | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLP-SIR | Combines likelihood profiling with resampling | Small datasets (n ≤ 10); pharmacometric models [2] | Computational intensity |

| Bayesian Approaches (BAY) | Integrates prior knowledge with observed data | When informative priors are available; hierarchical models [2] | Sensitivity to prior specification |

| Gaussian Processes | Probabilistic curve fitting with uncertainty estimates | Dose-response data without replicates; biomarker identification [4] | Complex implementation |

| Non-Parametric Bootstrap | Resampling with replacement to estimate sampling distribution | Moderate sample sizes; correlated parameters [1] | May perform poorly with very small n |

| Standard Error (SE) | Based on asymptotic theory | Large sample sizes only [2] | Unreliable for n ≤ 10 |

Impact of Uncertainty on Model Outcomes

The practical implications of parameter uncertainty are substantial across drug development applications. In health economic modeling, accounting for parameter uncertainty in distributions describing stochastic uncertainty substantially increases the uncertainty surrounding health economic outcomes, illustrated by larger confidence ellipses surrounding cost-effectiveness point-estimates and different cost-effectiveness acceptability curves [1]. For biomarker discovery, incorporating uncertainty estimates enables more reliable identification of genetic sensitivity and resistance markers, with demonstrated ability to identify clinically established drug-response biomarkers while providing evidence for novel associations [4].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Parameter Uncertainty

Protocol 1: LLP-SIR for Small-n Pharmacometric Analyses

Purpose: To accurately assess parameter uncertainty in pharmacometric analyses with limited data (n ≤ 10 subjects) [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Patient data (typically 10 or fewer subjects)

- Pharmacometric model structure

- Computational environment for model fitting (e.g., R, NONMEM)

- Log-likelihood profiling algorithm

- Sampling importance resampling implementation

Procedure:

- Model Estimation: Fit the pharmacometric model to the original dataset to obtain initial parameter estimates.

- Log-Likelihood Profiling: For each parameter, construct a profile log-likelihood by systematically varying the parameter across a plausible range while optimizing all other parameters.

- Proposal Distribution Construction: Use the likelihood profiles to generate proposal distributions for each parameter that reflect their uncertainty.

- Importance Resampling: Draw parameter candidates from the proposal distributions and calculate importance weights based on the likelihood ratio between the true and proposal distributions.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculate confidence intervals (typically 0-95% CI) from the weighted resamples and evaluate coverage properties against reference CIs derived from stochastic simulation and estimation.

Validation: Compare determined CIs and coverage probabilities with reference methods; LLP-SIR should demonstrate best alignment with reference CIs in small-n settings [2].

Protocol 2: Gaussian Process Regression for Dose-Response Uncertainty

Purpose: To quantify uncertainty in dose-response experiments and improve biomarker detection in high-throughput screening without replicates [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- High-throughput drug screening data (multiple concentrations per compound)

- Cell viability measurements

- Molecular characterization data (e.g., genetic variants)

- Gaussian process regression implementation

- Bayesian hierarchical modeling framework

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Organize dose-response data with measured cell viability values across concentration gradients for each compound-cell line combination.

- Gaussian Process Modeling: Apply GP regression to describe the relationship between dose concentrations and response, modeling experimental variance without assuming a specific functional form.

- Posterior Sampling: Generate samples from the posterior distribution over functions to quantify uncertainty in curve fits for each experiment.

- Summary Statistics Calculation: Compute IC50 and AUC values from GP samples, recording both point estimates (mean) and uncertainty measures (standard deviation).

- Biomarker Identification: Test association between response statistics and genetic variants using both frequentist (ANOVA) and Bayesian frameworks, incorporating uncertainty estimates.

- Validation: Compare GP-based uncertainty estimates with standard deviations measured from replicate experiments where available.

Applications: This approach successfully identified 24 clinically established drug-response biomarkers and provided evidence for six novel biomarkers by accounting for association with low uncertainty [4].

Protocol 3: Bootstrap and MVNorm for Health Economic Models

Purpose: To account for parameter uncertainty in parametric distributions used to describe stochastic uncertainty in patient-level health economic models [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- Individual patient data (IPD) for time-to-event or other outcomes

- Pre-specified parametric distributions (e.g., Weibull, Gamma)

- Statistical software with bootstrapping and multivariate Normal sampling capabilities

- Health economic model structure (e.g., discrete event simulation)

Bootstrap Approach Procedure:

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: Generate r bootstrap samples (where r equals required PSA runs) by resampling the original dataset with replacement, maintaining original sample size.

- Distribution Fitting: Fit pre-specified distributions to each bootstrap sample, recording all estimated parameter values.

- PSA Execution: Perform probabilistic sensitivity analysis, using a different set of correlated parameter values from each bootstrap iteration to define the distributions in each PSA run.

MVNorm Approach Procedure:

- Parameter Estimation: Fit pre-specified distributions to the original dataset, recording parameter estimates and their variance-covariance matrix.

- Multivariate Distribution Definition: Define a multivariate Normal distribution using the parameter estimates and variance-covariance matrix.

- Parameter Sampling: Draw r feasible sets of parameter values from the defined multivariate distribution.

- PSA Execution: Perform probabilistic sensitivity analysis, using a different set of sampled parameter values in each PSA run.

Comparison: For larger sample sizes (n=500), both approaches perform similarly, but the MVNorm approach is more sensitive to extreme values with small samples (n=25), potentially yielding infeasible modeling outcomes [1].

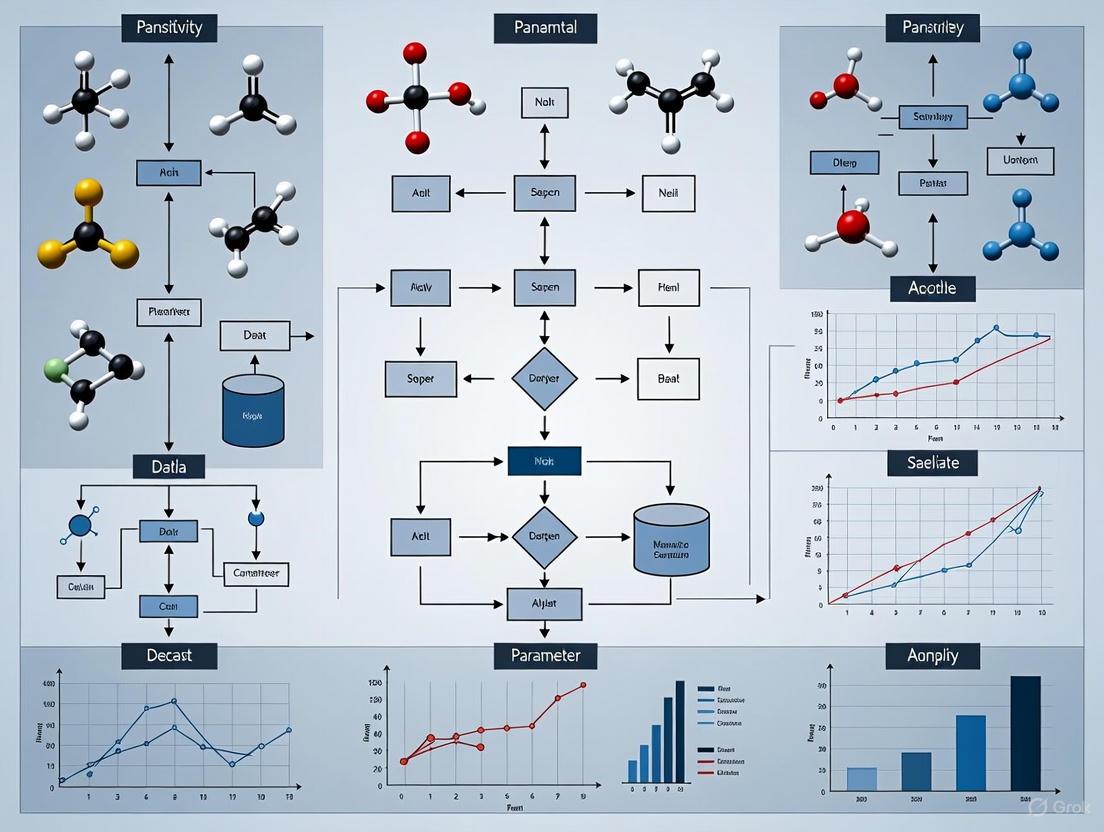

Visualizing Workflows for Parameter Uncertainty Assessment

Workflow for Parameter Uncertainty Assessment: This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to selecting and applying appropriate methods for parameter uncertainty assessment based on dataset characteristics and research context. The workflow begins with data input and proceeds through method selection based on sample size and data type, with specialized approaches for small-n datasets (LLP-SIR), dose-response data (Gaussian Processes), and larger datasets (Bootstrap and MVNorm approaches) [2] [4] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Uncertainty Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Log-Likelihood Profiling Algorithm | Constructs likelihood-based proposal distributions for parameters | LLP-SIR implementation for small-n analyses [2] |

| Gaussian Process Regression Package | Implements probabilistic dose-response curve fitting with uncertainty estimates | High-throughput screening data without replicates [4] |

| Bootstrap Resampling Software | Generates multiple resampled datasets to estimate sampling distributions | Health economic models with correlated parameters [1] |

| Multivariate Normal Sampler | Draws correlated parameter sets from defined distributions | Reflecting parameter uncertainty in parametric distributions [1] |

| Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling Framework | Integrates prior knowledge with observed data for improved predictions | Biomarker discovery incorporating uncertainty estimates [4] |

| Clinical Trial Simulation Platform | Virtually predicts trial outcomes under different uncertainty scenarios | Pharmacometrics-informed clinical scenario evaluation [3] |

| Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) Tools | Provides quantitative predictions across drug development stages | Fit-for-purpose application from discovery to post-market [5] |

Defining and addressing parameter uncertainty is essential for robust pharmacometric modeling and informed decision-making in drug development. The appropriate selection of uncertainty assessment methods depends critically on dataset characteristics, with specialized approaches like LLP-SIR demonstrating particular value for small-n analyses where conventional methods fail [2]. As model-informed drug development continues to evolve, incorporating systematic uncertainty assessment through Gaussian Processes [4], bootstrapping [1], and related methodologies will remain crucial for generating reliable evidence across the drug development continuum, from early discovery through regulatory approval and post-market monitoring [5].

The Critical Role of Sensitivity Analysis in Robust Scientific Inference

Sensitivity analysis is a crucial technique used to predict the impact of varying input variables on a given outcome, serving as a cornerstone for strategic decision-making in modern analytics and scientific research [6]. In the context of robust scientific inference, particularly in biomedical research and drug development, sensitivity analysis provides a structured, data-driven approach for assessing how uncertainties in model parameters and inputs influence model outputs, predictions, and subsequent conclusions [7]. This methodology transforms uncertainties into numerical values that can be analyzed, compared, and integrated into decision-making processes, enabling researchers to quantify the reliability of their inferences and prioritize efforts toward the most influential factors [7].

The fundamental importance of sensitivity analysis lies in its ability to strengthen decision-making by removing guesswork and relying on hard data. Statistical models and numerical evaluations reduce bias and help leaders understand risks with clarity [7]. For computational models predicting drug efficacy and toxicity—emergent properties arising from interactions across multiple levels of biological organization—sensitivity analysis provides essential "road maps" for navigating across scales, from molecular mechanisms to clinical observations [8]. By systematically testing how changes in input variables affect outcomes, researchers can build more credible, transparent, and trustworthy models that withstand critical evaluation from both theoretical and experimental perspectives [8].

Core Principles and Quantitative Frameworks

Foundational Concepts

Sensitivity analysis operates on several core principles essential for robust scientific inference. The approach is fundamentally based on the recognition that all models, whether computational or conceptual, contain uncertainties that must be characterized to establish confidence in their predictions [8]. At its core, sensitivity analysis involves applying mathematical models and statistical techniques to estimate the probability, impact, and exposure of these uncertainties, transforming them into measurable data that can be objectively evaluated [7].

A key conceptual framework in modern sensitivity analysis is the "fit-for-purpose" principle, which indicates that analytical tools need to be well-aligned with the "Question of Interest," "Context of Use," and "Model Evaluation" criteria [5]. This principle emphasizes that sensitivity analysis methodologies should be appropriately scaled and scoped to address the specific inference problem at hand—from early exploratory research to late-stage regulatory decision-making. A model or method is not "fit-for-purpose" when it fails to define the context of use, lacks data with sufficient quality or quantity, or incorporates unjustified complexities that obscure rather than illuminate key relationships [5].

Quantitative Methodologies

Several quantitative methodologies form the backbone of sensitivity analysis in scientific inference, each with distinct applications and advantages:

- Local Sensitivity Analysis: Examines how small perturbations around a nominal parameter value affect model outputs. While computationally efficient, this approach may miss nonlinear behaviors across broader parameter spaces.

- Global Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluates how model outputs are affected by variations across the entire parameter space, often using techniques like Monte Carlo sampling [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying interactions between parameters and understanding system behaviors under diverse conditions.

- Regression-Based Techniques: Utilize statistical models to quantify relationships between input parameters and outputs, providing sensitivity measures like standard regression coefficients.

- Variance-Based Methods: Decompose the output variance into contributions from individual parameters and their interactions, offering comprehensive sensitivity measures such as Sobol indices.

Each methodology offers complementary strengths: differential equations capture dynamic processes, network theory reveals structural relationships, and statistical learning identifies patterns in complex data [8]. The integration of machine learning with traditional sensitivity analysis approaches represents a growing area of innovation, where ML excels at uncovering patterns in large datasets while conventional methods provide biologically grounded, mechanistic frameworks [8].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Methods for Sensitivity Analysis

| Method | Primary Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-at-a-Time (OAT) | Local sensitivity around nominal values | Computational efficiency; Intuitive interpretation | Misses parameter interactions; Limited exploration of parameter space |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Global sensitivity across parameter distributions [7] | Comprehensive; Handles complex distributions | Computationally intensive; Requires many simulations |

| Regression-Based Methods | Linear and monotonic relationships | Simple implementation; Standardized coefficients | Assumes linearity; Limited for complex responses |

| Variance-Based Methods | Apportioning output variance to inputs [7] | Captures interactions; Comprehensive | High computational cost; Complex implementation |

| Machine Learning Approaches | High-dimensional parameter spaces | Handles nonlinearities; Pattern recognition | "Black box" concerns; Requires large datasets |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Model Sensitivity Testing

Purpose: To systematically evaluate how uncertainties in model parameters influence key outputs and inferences in drug development research.

Materials and Equipment:

- Computational model (e.g., PBPK, QSP, PK/PD)

- Parameter distributions (defined from experimental data or literature)

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python, MATLAB)

- High-performance computing resources (for large-scale simulations)

Procedure:

- Define the Model and Outputs of Interest

- Clearly articulate the model structure, including all equations, parameters, and state variables.

- Identify specific model outputs relevant to scientific inference (e.g., efficacy endpoints, toxicity metrics, exposure measures).

Characterize Parameter Uncertainty

- For each model parameter, define a probability distribution representing its uncertainty.

- Distributions may be based on experimental data, literature values, or expert opinion.

- Document all distribution assumptions and their justifications.

Generate Parameter Samples

- Using sampling techniques (Latin Hypercube, Monte Carlo), generate multiple parameter sets representing possible combinations across the uncertainty space [7].

- Sample size should be sufficient to achieve stable sensitivity estimates (typically 1,000-10,000 iterations).

Execute Model Simulations

- Run the model with each parameter set to generate corresponding output values.

- Implement parallel processing where possible to reduce computational time.

Calculate Sensitivity Measures

- Compute sensitivity indices (e.g., correlation coefficients, partial derivatives, variance-based measures) quantifying relationships between parameters and outputs.

- Use multiple sensitivity measures to capture different aspects of parameter influence.

Interpret and Document Results

- Identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs (key drivers).

- Assess whether sensitive parameters are well-constrained by existing data.

- Document all procedures, results, and interpretations for transparency.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If sensitivity patterns are unclear, increase sample size or try alternative sensitivity methods.

- For computationally intensive models, consider emulator-based approaches (e.g., Gaussian process regression) to approximate model behavior.

- If all parameters show low sensitivity, reevaluate model structure for potential oversimplifications or missing interactions.

Protocol 2: Risk-Based Decision Framework for Drug Development

Purpose: To prioritize research efforts and resource allocation based on sensitivity analysis results within drug development programs.

Materials and Equipment:

- Sensitivity analysis results from Protocol 1

- Decision context framework (e.g., go/no-go criteria, optimization objectives)

- Risk assessment templates

- Cross-functional stakeholder team

Procedure:

- Define Decision Context

- Clearly articulate the specific decision(s) to be informed by sensitivity analysis.

- Identify decision thresholds or criteria (e.g., minimal efficacy requirements, maximum acceptable toxicity).

Map Sensitivities to Development Risks

- Classify parameters by both sensitivity and uncertainty:

- High sensitivity, high uncertainty: Key knowledge gaps requiring immediate research

- High sensitivity, low uncertainty: Well-characterized critical parameters

- Low sensitivity, high uncertainty: Lower priority for additional characterization

- Low sensitivity, low uncertainty: Minimal impact on decisions

- Classify parameters by both sensitivity and uncertainty:

Quantify Impact on Decision Criteria

- Use sensitivity results to assess how parameter uncertainties propagate to decision-relevant outcomes.

- Calculate confidence levels for meeting key decision criteria.

Develop Mitigation Strategies

- For high sensitivity/high uncertainty parameters, design experiments to reduce uncertainty.

- For critical parameters with acceptable uncertainty, establish monitoring plans.

- Consider model refinement opportunities to better represent key biological processes.

Implement Iterative Learning Cycle

- As new data become available, update parameter distributions and refine sensitivity analyses.

- Reassess decisions based on reduced uncertainties.

- Document the evolution of understanding throughout the development process.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If decision thresholds are consistently missed despite parameter optimization, consider fundamental model limitations or alternative development paths.

- When stakeholder consensus is challenging, use sensitivity analysis to objectively highlight most influential factors and areas of greatest uncertainty.

- If unexpected parameter interactions emerge, conduct additional analyses to understand their biological basis and implications.

Visualization and Workflow Implementation

Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for implementing sensitivity analysis in scientific inference, particularly within drug development contexts:

Multi-Scale Biological Context

Drug efficacy and toxicity emerge from interactions across multiple biological scales, as visualized in the following diagram. Sensitivity analysis helps navigate this complexity by identifying which parameters and processes most significantly influence overall outcomes:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust sensitivity analysis requires both computational tools and methodological frameworks. The following table details essential components of the modern sensitivity analysis toolkit for drug development researchers:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Sensitivity Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Models, Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models, Population PK/PD Models | Provide mechanistic frameworks for simulating drug behavior across biological scales; Serve as foundation for sensitivity testing [5] [8] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R with sensitivity package, Python with SALib, MATLAB SimBiology, NONMEM | Implement sensitivity algorithms; Calculate sensitivity indices; Visualize results [7] |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools | Monte Carlo Simulation engines, Latin Hypercube Sampling, Markov Chain Monte Carlo | Generate parameter samples representing uncertainty space; Propagate uncertainties through models [7] |

| Data Management Systems | Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS), Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELN) | Curate experimental data for parameter estimation; Ensure data quality for uncertainty characterization |

| Visualization Frameworks | Sensitivity dashboards, Tornado diagrams, Scatterplot matrices, Sobol' indices plots | Communicate sensitivity results to diverse stakeholders; Support interactive exploration of parameter influences [6] |

| Decision Support Tools | Risk assessment matrices, Go/No-go frameworks, Portfolio optimization algorithms | Translate sensitivity results into actionable development decisions; Prioritize research activities [7] |

Applications in Drug Development and Beyond

Drug Development Case Studies

Sensitivity analysis plays a transformative role throughout the drug development continuum, from early discovery to post-market monitoring. In early discovery, sensitivity analysis of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models helps prioritize compound synthesis by identifying which molecular features most strongly influence target engagement and preliminary safety profiles [5]. During preclinical development, Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models leverage sensitivity analysis to determine critical physiological parameters influencing drug disposition, guiding design of definitive toxicology studies and predicting human starting doses [5].

In clinical development, population pharmacokinetic and exposure-response models utilize sensitivity analysis to quantify how patient factors (e.g., renal/hepatic function, drug interactions) contribute to variability in drug exposure and effects [5]. This analysis informs optimal dosing strategies and identifies patient subgroups requiring dose adjustments. For regulatory decision-making, sensitivity analysis demonstrates the robustness of primary conclusions to model assumptions and parameter uncertainties, increasing confidence in benefit-risk assessments [8].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of sensitivity analysis is rapidly evolving, with several trends shaping its future application in scientific inference. AI-driven automation is revolutionizing sensitivity analysis through automated data import from diverse sources and automated charting via natural language commands [6]. These advances reduce manual setup time by up to 50% and make sophisticated analyses accessible to non-specialists. Real-time data integration allows for immediate updates as new information becomes available, reducing decision cycles by up to 40% and ensuring analyses reflect the most current information [6].

The integration of machine learning with traditional modeling represents another significant advancement, where ML techniques enhance pattern recognition in high-dimensional parameter spaces while mechanistic models provide biological interpretability [8]. This synergistic approach addresses the limitations of both methods when used in isolation. Finally, community-driven efforts to establish standards for model transparency, reproducibility, and credibility—such as ASME V&V 40, FDA guidance documents, and FAIR principles—are strengthening the foundational role of sensitivity analysis in regulatory science and public health decision-making [8].

Table 3: Sensitivity Analysis Applications Across Drug Development Stages

| Development Stage | Primary Sensitivity Analysis Applications | Key Methodologies | Impact on Decision-Making |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Early Research | Target validation; Compound optimization; In vitro-in vivo extrapolation | QSAR models; Systems biology networks; High-throughput screening analysis | Prioritizes most promising chemical series; Identifies critical experiments for mechanism confirmation [5] |

| Preclinical Development | First-in-human dose prediction; Species extrapolation; Toxicology study design | PBPK models; Allometric scaling; Dose-response modeling | Supports safe starting dose selection; Guides clinical monitoring strategies [5] |

| Clinical Development | Protocol optimization; Patient stratification; Dose selection; Trial enrichment | Population PK/PD; Exposure-response; Covariate analysis | Informs adaptive trial designs; Optimizes dosing regimens; Identifies responsive populations [5] |

| Regulatory Review & Approval | Benefit-risk assessment; Labeling decisions; Post-market requirements | Model-based meta-analysis; Comparative effectiveness; Uncertainty quantification | Provides evidence for approval decisions; Supports personalized medicine recommendations [5] [8] |

| Post-Market Monitoring | Real-world evidence integration; Population heterogeneity assessment; Risk management | Pharmacoepidemiologic models; Outcomes research; Safety signal detection | Optimizes risk evaluation mitigation strategies; Informs label updates [5] |

In computational modeling, whether for drug development, environmental assessment, or engineering design, Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) is the science of quantitatively characterizing and estimating uncertainties in both computational and real-world applications [9]. It aims to determine how likely certain outcomes are when some aspects of the system are not exactly known. A closely related discipline, Sensitivity Analysis (SA), systematically investigates the relationships between model predictions and its input parameters [10]. Together, these fields provide researchers with methodologies to assess how input uncertainty propagates through computational models to affect output uncertainty, enabling more credible predictions and robust decision-making under uncertainty [11].

This application note outlines core principles, methodologies, and practical protocols for quantifying how input uncertainty impacts model outputs, with particular emphasis on applications relevant to pharmaceutical development and other scientific domains. The content is structured to provide researchers with both theoretical foundations and implementable frameworks for integrating UQ and SA into their modeling workflows, thereby enhancing model reliability and regulatory acceptance.

Theoretical Foundations: Classifying Uncertainty

Fundamental Uncertainty Typologies

Uncertainty in mathematical models and experimental measurements arises from multiple sources, which can be categorized as follows [9]:

- Parameter Uncertainty: Stems from model parameters that are inputs to the computer model but whose exact values are unknown or cannot be exactly inferred through statistical methods.

- Parametric Uncertainty: Arises from the inherent variability of input variables of the model.

- Structural Uncertainty: Also termed model inadequacy, model bias, or model discrepancy, this originates from the lack of knowledge of the underlying physics or biology in the problem.

- Algorithmic Uncertainty: Results from numerical errors and approximations in the implementation of the computer model.

- Experimental Uncertainty: Derives from the variability of experimental measurements, observable when repeating measurements using identical settings.

Aleatoric vs. Epistemic Uncertainty

A particularly valuable classification distinguishes between two fundamental types of uncertainty [9] [12]:

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: Also known as stochastic, irreducible, or variability uncertainty, this represents inherent randomness that differs each time an experiment is run. It can be characterized using traditional probability theory and statistical moments, with Monte Carlo methods being a common quantification approach [9] [11].

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Also called systematic, subjective, or reducible uncertainty, this results from incomplete knowledge about the system, process, or mechanism. It is typically quantified through Bayesian probability, where probabilities indicate the degree of belief regarding a specific claim [9].

In real-world applications, both types often coexist and interact, requiring methods that can explicitly express both separately [9]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for directing resources efficiently; if epistemic uncertainty dominates, collecting more data may significantly reduce overall output uncertainty [11].

Methodological Frameworks for Uncertainty Propagation

Forward Uncertainty Propagation

Forward UQ quantifies uncertainty in model outputs given uncertainties in inputs, model parameters, and model errors [11]. The targets of uncertainty propagation analysis include evaluating low-order moments of outputs (mean, variance), assessing system reliability, determining complete probability distributions, and estimating uncertainty in values that cannot be directly measured [9].

Table 1: Sampling-Based Methods for Forward Uncertainty Propagation

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Runs numerous model simulations with randomly varied inputs to map output distribution | Intuitive, handles any model complexity, comprehensive uncertainty characterization | Computationally expensive for complex models | Baseline approach for most systems [12] |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling | Stratified sampling technique for improved efficiency over random sampling | Better coverage of input space with fewer runs than Monte Carlo | More complex implementation than simple Monte Carlo | Engineering design, environmental modeling [12] |

| Monte Carlo Dropout | Keeps dropout active during prediction for multiple forward passes | Computationally efficient for neural networks, no retraining required | Specific to neural network architectures | Deep learning applications, image classification [12] |

| Gaussian Process Regression | Places prior distribution over functions, uses data for posterior distribution | Provides inherent uncertainty estimates, no extra training required | Scaling issues with very large datasets | Optimization, time series forecasting [12] |

Bayesian Methods for Uncertainty Quantification

Bayesian statistics provides a powerful framework for UQ by explicitly dealing with uncertainty through probability distributions rather than single fixed values [12]. Key approaches include:

- Bayesian Inference: Updates prior beliefs with observed data using Bayes' theorem to calculate posterior probability distributions for model parameters [12].

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC): Samples from complex, high-dimensional probability distributions that cannot be sampled directly, particularly useful for Bayesian posterior estimation [12] [11].

- Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs): Treat network weights as probability distributions rather than fixed values, enabling principled uncertainty quantification in deep learning applications [12].

Advanced and Ensemble Methods

- Ensemble Methods: Train multiple independent models with different architectures, training data subsets, or initialization. Uncertainty is quantified through the variance or spread of ensemble predictions, with disagreement among models indicating higher uncertainty [12].

- Conformal Prediction: A distribution-free, model-agnostic framework for creating prediction intervals (regression) or prediction sets (classification) with valid coverage guarantees and minimal assumptions about model or data distribution [12].

Sensitivity Analysis Techniques

Global Sensitivity Analysis Methods

Sensitivity analysis evaluates how uncertainty in model outputs can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in model inputs [10]. Global methods explore the entire input space, making them particularly valuable for nonlinear models and those with parameter interactions.

Table 2: Global Sensitivity Analysis Methodologies

| Method | Underlying Approach | Sensitivity Measures | Strengths | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sobol' Method | Variance-based decomposition | First-order, second-order, and total-effect indices | Comprehensive, captures interactions | General model analysis [13] [11] |

| Extended Fourier Amplitude Sensitivity Test (EFAST) | Fourier analysis of variance | First-order and total sensitivity indices | Computational efficiency, handles interactions | Crop growth models [13], environmental systems |

| Morris Method | One-at-a-time elementary effects | Elementary effects mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) | Efficient screening for important parameters | Initial parameter screening [14] |

| Regional Sensitivity Analysis | Conditional sampling based on output behavior | Behavioral vs. non-behavioral parameter distributions | Identifies critical parameter ranges for specific outcomes | Penstock modeling [14], engineering design |

Practical Implementation of EFAST Global Sensitivity Analysis

The EFAST method combines advantages of the classic FAST and Sobol' methods, quantitatively analyzing both direct and indirect effects of input parameters on outputs [13]. The following protocol outlines its implementation for analyzing cultivar parameters in crop growth models, adaptable to other domains:

Experimental Protocol: EFAST Global Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To identify cultivar parameters that significantly impact simulation outputs under different environmental conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software Environment: R statistical programming platform with 'sensitivity' package [13]

- Model System: DSSAT-Wheat crop growth model or domain-specific equivalent

- Computational Resources: Workstation capable of running 800+ simulations [13]

Procedure:

- Parameter Selection: Identify target parameters for analysis (e.g., P5, P1D, P1V, G2, G1 for wheat models) [13]

- Input Sample Generation:

- Generate 800 sets of cultivar parameters using the specialized sampling strategy of the EFAST method [13]

- Ensure parameter ranges reflect biologically/physically plausible values

- Model Execution:

- Run simulations for each parameter set under each experimental condition of interest

- Record output variables (e.g., yield, dry matter, leaf area index) [13]

- Sensitivity Index Calculation:

- Compute first-order sensitivity indices (main effects) using Fourier decomposition

- Calculate total sensitivity indices (including interaction effects)

- Apply statistical analysis using SPSS or equivalent software [13]

- Interpretation:

- Rank parameters by sensitivity indices

- Identify parameters with significant interactions (total sensitivity >> first-order sensitivity)

- Evaluate how parameter sensitivities change under different stress conditions [13]

Validation:

- Confirm reproducibility through repeated sampling

- Compare results with other sensitivity methods when feasible

- Validate against experimental data where available

Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Regulatory Science

Uncertainty Considerations in Drug Development

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration acknowledges that regulatory decisions must frequently draw conclusions from imperfect data, making the identification and evaluation of uncertainty sources a critical component of drug application review [15]. Specific challenges include:

- Human Variability: Clinical trials cannot provide complete information about effectiveness or harm in more variable real-world populations [15]

- Trial Limitations: Time-limited trials cannot measure effects of chronic use, and sample size limitations create uncertainty about whether differences represent true effects or random variation [15]

- Unknown Unknowns: Lack of knowledge about what data might be missing or what domains of harm should be studied has historically led to significant safety controversies [15]

Methodological Uncertainties in Clinical Evidence

Tarek Hammad of Merck & Co. outlines three distinct but interrelated categories of uncertainty in pharmaceutical research [15]:

- Clinical Uncertainty: Arises from reliance on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with volunteers under specific inclusion/exclusion criteria, limiting real-world application, plus potential for off-label use and adverse events with long latent periods [15]

- Statistical Uncertainty: Stems from sampling techniques and a system designed primarily for drugs to pass tests rather than precisely quantify risks and benefits [15]

- Methodological Uncertainty: Includes disparities between RCTs designed to assess benefits versus observational studies typically employed for post-market harm assessment [15]

Uncertainty Taxonomy in Drug Development

Case Studies in Applied Uncertainty Quantification

Radiative Cooling Materials Life Cycle Assessment

A comprehensive uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of radiative cooling materials provides insights into parameter influence on environmental impact assessments [16]:

Key Findings:

- Process-related parameters (sputtering rate and pumping power) contributed more significantly to uncertainty than inventory datasets [16]

- Doubling pumping power doubled environmental impact, while lowest sputtering rates increased impact by over 600% [16]

- Best- and worst-case scenario analyses showed variations up to 1278%, emphasizing the need for precise process data [16]

Methodological Approach:

- Combined parameter variation, scenario analysis, and Monte Carlo simulations

- Utilized pedigree matrix evaluation for data quality assessment

- Implemented lognormal distributions for Monte Carlo analysis reflecting positively skewed environmental data [16]

Wheat Cultivar Parameter Sensitivity Under Stress Conditions

Research on wheat cultivar parameters in the DSSAT model demonstrates how sensitivity analysis identifies critical parameters under varying environmental conditions [13]:

Key Findings:

- P5 and P1D were most sensitive for aboveground dry matter and dry matter nitrogen fertilizer utilization [13]

- G2, G1, and P1D were most sensitive for yield and maximum nitrogen at maturity [13]

- Water and nitrogen stresses significantly decreased parameter sensitivity, with water stress having greater impact [13]

- Parameter uncertainty was minimized at 200 kg/hm² nitrogen treatment, providing optimal simulation conditions [13]

Research Reagent Solutions for UQ/SA Studies

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Uncertainty Quantification and Sensitivity Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Programming Environments | R with 'sensitivity' package [13] | Global sensitivity analysis implementation | General SA applications, including EFAST method |

| Bayesian Inference Tools | PyMC, TensorFlow-Probability [12] | Bayesian neural networks, probabilistic modeling | Complex models requiring uncertainty-aware deep learning |

| Sampling Algorithms | Latin Hypercube Sampling, Monte Carlo [12] | Efficient input space exploration | Forward uncertainty propagation |

| Surrogate Modeling Techniques | Gaussian Process Regression, Principal Components Analysis [12] [11] | Computational cost reduction for complex models | Models with high computational demands per simulation |

| Model Validation Frameworks | AIAA, ASME Validation Standards [11] | Quantitative model credibility assessment | Regulatory submissions, high-consequence applications |

Integrated UQ/SA Protocol for Model Evaluation

Building on the principles and case studies presented, the following integrated protocol provides a structured approach for comprehensive model evaluation:

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Uncertainty Analysis and Global Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To characterize model sensitivities and quantify uncertainty contributions from various sources in computational models.

Materials:

- Software: R with sensitivity package, Python with UQ libraries (e.g., PyMC, TensorFlow-Probability, Scikit-learn) [13] [12]

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing access for large-scale simulations

- Model System: Validated computational model of the system under study

Procedure:

- Uncertainty Analysis (UA):

Screening Phase:

- Apply Morris method for computationally efficient parameter screening [14]

- Identify parameters with negligible effects for potential fixation

- Refocus subsequent analysis on influential parameters

Multi-method Global Sensitivity Analysis:

Regional Sensitivity Analysis:

- Conduct RSA to identify critical parameter ranges for specific output behaviors [14]

- Define behavioral vs. non-behavioral parameter distributions based on output thresholds

- Map parameter combinations leading to extreme or critical outputs

Uncertainty Decomposition:

- Quantify contributions of individual uncertainty sources to output variance [11]

- Distinguish between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty contributions

- Identify opportunities for uncertainty reduction through targeted data collection

Decision Support Outputs:

- Parameter prioritization for model refinement and data collection

- Guidance for resource allocation to reduce dominant uncertainty sources

- Model validation targets based on uncertainty characterization

- Risk assessment under uncertainty for decision-making

This structured methodology provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for analyzing and interpreting how input uncertainty impacts model outputs, facilitating more reliable predictions and robust decision-making across scientific domains.

Sensitivity Analysis (SA) is defined as "the study of how uncertainty in the output of a model (numerical or otherwise) can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input" [17]. In the context of parameter uncertainty research, SA provides a systematic framework for understanding how variations in model parameters affect model outputs and inferences. This discipline has evolved beyond a simple model-checking exercise to become an essential methodology for robust scientific inference and decision-making [18]. The fundamental relationship explored in SA can be expressed as (y=g(x)), where (y=[y1,y2,...,yM]) represents M output variables, (x=[x1,x2,...,xN]) represents N input variables, and (g) is the model mapping inputs to outputs [17].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, SA serves three primary strategic objectives: model evaluation (assessing robustness and credibility), model simplification (reducing complexity without sacrificing predictive capability), and exploratory analysis (discovering consequential system behaviors and informing decisions) [17] [19]. The appropriate application of SA is particularly crucial in drug development and biomedical contexts, where models inform safety-critical decisions and regulatory evaluations [20].

Core Objectives of Sensitivity Analysis

Model Evaluation: Establishing Robustness and Credibility

Model evaluation through SA aims to gauge model inferences when assumptions about model structure or parameterization are dubious or have changed [17]. In drug development contexts, this establishes whether model-based predictions remain stable despite underlying parameter uncertainties [20]. The ASME V&V40 Standard emphasizes the importance of uncertainty quantification and SA when evaluating computational models for healthcare applications, as rigorous SA provides confidence that model-based decisions are robust to uncertainties [20].

Key Applications:

- Credibility Assessment: Testing whether small changes in parameter values significantly alter model outputs and the decisions they inform [17] [20].

- Error Diagnosis: Understanding how and under what conditions modeling choices propagate through model components and manifest in their effects on outputs [19].

- Performance Evaluation: Moving beyond single performance metrics to analyze multiple error signatures across different scales and system states [19].

Table 1: Model Evaluation Protocols Across Domains

| Domain | Primary Evaluation Focus | Key Parameters Analyzed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiative Cooling Materials LCA | Parameter sensitivity on environmental impact | Sputtering rate, pumping power | [16] |

| Cardiac Electrophysiology | Action potential robustness to parameter uncertainty | Ion channel conductances, steady-state parameters | [20] |

| Hydropower Penstock Modeling | Structural variability in dynamic response | Modal parameters, structural properties | [14] |

| BSL-IAPT Economic Evaluation | Cost-effectiveness uncertainty | Probabilities, costs, QALYs | [21] |

Model Simplification: Managing Complexity

Model simplification through SA identifies factors or components with limited effects on outputs or metrics of interest [17]. This "factor fixing" approach reduces unnecessary computational burden and helps focus research efforts on the most influential parameters. In complex physiological models like whole-heart electrophysiology models with hundreds of parameters, SA provides a principled approach to model reduction without significant loss of predictive capability [20].

Protocol 1: Factor Fixing Methodology

Define Significance Threshold: Establish a minimum threshold value for contribution to output variance (e.g., 1-5% of total variance) based on model purpose and regulatory requirements [17] [20].

Global Sensitivity Analysis: Apply variance-based methods (Sobol indices) or screening methods (Morris method) to rank parameters by influence [17] [14].

Identify Non-Influential Factors: Flag parameters with sensitivity indices below the significance threshold as candidates for fixing [17].

Verify Simplification: Test the reduced model (with fixed parameters) against the full model to ensure performance is not significantly degraded within the intended application domain [17].

Document Rationale: Record the sensitivity indices and decision process for regulatory submissions [20].

Exploratory Analysis: Informing Decision-Making

Exploratory analysis uses SA to discover decision-relevant and highly consequential outcomes, particularly through "factor mapping" that identifies which values of uncertain factors lead to model outputs within a specific range [17]. This application is particularly valuable in drug development for understanding risk boundaries and safe operating spaces for therapeutic interventions.

Protocol 2: Exploratory Factor Mapping

Define Behavioral/Non-Behavioral Regions: Establish output regions corresponding to desirable (e.g., therapeutic efficacy) and undesirable (e.g., toxicity) outcomes [17] [19].

Generate Input-Output Mappings: Use Monte Carlo sampling or Latin Hypercube sampling to explore the input space [16] [14].

Identify Critical Parameter Regions: Statistically analyze which parameter combinations consistently lead to behavioral or non-behavioral outcomes [17].

Map Decision Boundaries: Quantify parameter thresholds that separate desirable and undesirable outcomes [19].

Communicate Decision-Relevant Insights: Present results in terms of actionable parameter controls for development decisions [18].

Figure 1: Exploratory Factor Mapping Workflow. This diagram illustrates the process for identifying critical parameter regions that influence decision-relevant outcomes.

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Global vs. Local Sensitivity Analysis

A critical distinction in SA approaches lies between local and global methods. Local SA varies parameters around specific reference values to explore how small input perturbations influence model performance, while global SA varies uncertain factors within the entire feasible space to reveal global effects including interactive effects [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Local and Global Sensitivity Analysis Methods

| Characteristic | Local Sensitivity Analysis | Global Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Exploration | Limited to vicinity of reference values | Entire feasible parameter space |

| Computational Demand | Lower | Higher |

| Interaction Effects | Not captured | Explicitly quantified |

| Linearity Assumption | Required | Not required |

| Common Methods | One-at-a-time (OAT), derivatives | Sobol indices, Morris method, PAWN |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Limited for nonlinear systems | Preferred for complex models |

Protocol 3: Implementing Global Sensitivity Analysis

Characterize Input Uncertainty: Define probability distributions for all uncertain parameters based on experimental data, literature, or expert opinion [20]. For environmental impact assessments, lognormal distributions are often preferred due to positive skew common in environmental data [16].

Generate Parameter Samples: Use space-filling designs like Latin Hypercube Sampling to efficiently explore the parameter space [14]. Sample sizes typically range from hundreds to tens of thousands depending on model complexity.

Execute Model Simulations: Run the model with each parameter set, ensuring computational efficiency through parallelization where possible [20].

Calculate Sensitivity Indices: Compute global sensitivity measures (e.g., Sobol indices for variance decomposition) using specialized software packages.

Validate Sensitivity Results: Check convergence of indices with sample size and compare multiple methods where feasible [14].

Uncertainty Propagation and Analysis

Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) consists of two stages: uncertainty characterization (quantifying uncertainty in model inputs) and uncertainty propagation (estimating resultant uncertainty in model outputs) [20]. SA complements UQ by apportioning output uncertainty to different input sources.

Protocol 4: Integrated UQ and SA Workflow

Uncertainty Characterization:

Uncertainty Propagation:

- Employ Monte Carlo simulation for robust propagation through complex models [16]

- Run sufficient iterations (typically 1,000-10,000) for stable statistics

- Analyze output distributions for key decision metrics

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Calculate variance-based sensitivity indices (e.g., Sobol indices)

- Identify parameter interactions through total-effect indices

- Rank parameters by influence on output uncertainty [20]

Decision Support:

Figure 2: Integrated UQ-SA Workflow. This diagram shows the relationship between uncertainty characterization, propagation, and sensitivity analysis in supporting decisions.

Domain-Specific Applications

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Applications

In LCA studies, SA addresses significant uncertainties arising from parameter choices, inventory data, and modeling assumptions [16]. A case study on radiative cooling materials demonstrated that process-related parameter choices contributed more significantly to uncertainty than inventory datasets, with key parameters like sputtering rate and pumping power impacting environmental footprint by over 600% in worst-case scenarios [16].

Protocol 5: LCA Uncertainty Assessment

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Analyze variations in production processes using one-at-a-time methods to identify critically sensitive parameters [16].

Monte Carlo Analysis: Assess uncertainty within inventory datasets using statistical sampling approaches [16].

Pedigree Matrix Evaluation: Incorporate data quality indicators for incomplete data using reliability, completeness, temporal, geographical, and technological accuracy criteria [16].

Scenario Analysis: Compare best-case, worst-case, and most probable outcomes to understand outcome ranges [16].

Biomedical and Healthcare Applications

In biomedical contexts, SA establishes model credibility for regulatory evaluation and clinical decision support [20]. Cardiac electrophysiology models, for example, require comprehensive SA to assess robustness to parameter uncertainty given natural physiological variability and measurement limitations [20].

Table 3: Sensitivity Analysis in Healthcare Decision Models

| Application Area | Key Uncertain Parameters | Sensitivity Methods | Decision Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Evaluation of BSL-IAPT | Probabilities of recovery, costs, QALYs | Scenario analysis, probabilistic SA | Cost-effectiveness of psychological therapies |

| Cardiac Cell Models | Ion channel conductances, kinetics | Comprehensive UQ/SA, robustness analysis | Drug safety assessment (CiPA initiative) |

| Penstock Structural Models | Modal parameters, material properties | Morris screening, regional SA | Structural reliability and safety |

Protocol 6: Healthcare Model Validation

Identify Influential Parameters: Use factor prioritization to determine which parameters contribute most to output variability [17] [20].

Assess Clinical Robustness: Verify that model-based recommendations remain stable across plausible parameter ranges [20].

Validate Against Multiple Endpoints: Test sensitivity across different clinical outcomes of interest [19].

Communicate Uncertainty Bounds: Present results with confidence intervals or uncertainty ranges for informed decision-making [21] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Sensitivity Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Algorithms | Latin Hypercube Sampling, Monte Carlo | Efficient parameter space exploration | All model types with computational constraints |

| Variance-Based Methods | Sobol indices, FAST | Quantify parameter influence and interactions | Models with nonlinearities and interactions |

| Screening Methods | Morris method, Elementary Effects | Identify important parameters efficiently | High-dimensional models with many parameters |

| Distribution Analysis | Lognormal, Uniform, Triangular | Represent parameter uncertainty appropriately | Context-dependent uncertainty characterization |

| Software Platforms | SAFE Toolbox, SALib, UQLab | Implement various SA methods | Accessible SA for research communities |

| Uncertainty Propagation | Monte Carlo simulation, Polynomial Chaos | Propagate input uncertainty to outputs | Risk assessment and decision support |

Sensitivity analysis serves as an essential discipline throughout the model development and application lifecycle, from initial evaluation through simplification to exploratory analysis [18]. For drug development professionals and researchers, mastering SA methodologies provides critical capabilities for robust inference and decision-making under uncertainty. The continued evolution of SA as an independent discipline promises enhanced capabilities for systems modeling, machine learning applications, and policy support across scientific domains [18]. By adopting structured protocols and understanding the distinct objectives of factor prioritization, factor fixing, and factor mapping, researchers can more effectively quantify and communicate the impact of parameter uncertainty on model-based conclusions.

Real-World Consequences of Ignoring Parameter Uncertainty in Drug Development

In modern drug development, computational and statistical models inform critical decisions, from target identification to dosing strategies. The reliability of these models hinges on accurately accounting for parameter uncertainty—the imperfect knowledge of model inputs estimated from limited data. Ignoring this uncertainty creates a facade of precision, leading to catastrophic failures in late-stage clinical trials and compromised patient safety. This application note details the tangible consequences of this oversight and provides actionable protocols to embed rigorous uncertainty quantification (UQ) and sensitivity analysis (SA) into the drug development workflow. Emerging trends like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) make robust UQ not just a statistical best practice but a cornerstone of efficient and trustworthy pharmaceutical innovation [22] [5] [23].

Quantifying the Impact: Consequences of Neglecting Parameter Uncertainty

Ignoring parameter uncertainty propagates silent errors through the development pipeline, with measurable impacts on cost, safety, and efficacy.

Table 1: Documented Consequences of Ignoring Parameter Uncertainty

| Development Stage | Consequence of Ignoring Uncertainty | Quantitative Impact / Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Preclinical & Clinical Predictions | Underestimation of prediction uncertainty, leading to overconfident and risky decisions. | Crop model analogy: Prediction uncertainties varied wildly (±6 to ±54 days for phenology; ±1.5 to ±4.5 t/ha for yield) when uncertainty was properly accounted for, compared to single-model practices [24]. |

| Clinical Trial Design | Inefficient or failed trial designs due to inaccurate power calculations and dose selection. | Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) that incorporates UQ can reduce cycle times by ~10 months and save ~$5 million per program [23]. |

| Drug Discovery & Development Efficiency | Increased late-stage attrition and resource waste from pursuing drug candidates with poorly understood risk profiles. | The industry faces "Eroom's Law" (the inverse of Moore's Law), where R&D productivity declines despite technological advances. UQ is key to reversing this trend [23]. |

| Regulatory Decision-Making | Submissions lacking robust UQ may face regulatory skepticism, require additional data, or fail to demonstrate definitive risk-benefit profiles. | Global regulators (FDA, EMA) show growing acceptance of advanced models and RWE, but they require transparent quantification of uncertainty for decision-making [22] [25]. |

Beyond these quantitative impacts, the strategic cost is profound. An over-reliance on single, deterministic models obscures the boundaries of knowledge, preventing teams from identifying critical data gaps and making truly risk-aware decisions [24] [26]. This can ultimately delay life-saving therapies for patients.

Visualizing the Problem and Solution

The following workflows contrast the standard, high-risk approach with a robust methodology that integrates UQ and SA.

Diagram 1: High-Risk Workflow Ignoring Parameter Uncertainty

High-Risk Pathway - This workflow illustrates how using a single "best-fit" parameter estimate without quantifying uncertainty leads to overconfident predictions and a high risk of failure in clinical trials [24] [5].

Diagram 2: Robust Workflow Integrating UQ and SA

Robust Pathway - This workflow demonstrates a robust approach where parameter uncertainty is quantified and propagated, enabling risk-informed decisions and efficiently guiding research [24] [5] [26].

Experimental Protocols for UQ and SA

Integrating UQ and SA requires standardized protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key analyses.

Protocol: Uncertainty Propagation for a Pharmacokinetic (PK) Model

This protocol quantifies how uncertainty in PK parameters (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution) translates to uncertainty in predicted drug exposure (AUC, C~max~).

1. Define Model and Parameters:

- Model: Specify the structural PK model (e.g., two-compartment intravenous model).

- Parameters: Identify parameters to be estimated (

CL,V1,Q,V2). Define their prior distributions based on preclinical data or literature (e.g., Log-Normal).

2. Estimate Posterior Parameter Distributions:

- Tool: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling within a Bayesian framework [24].

- Inputs: Observed concentration-time data.

- Output: Joint posterior distribution of all parameters, representing knowledge conditional on the data.

3. Propagate Uncertainty:

- Method: Monte Carlo Simulation.

- Procedure:

- Draw a large number (e.g., N=5000) of parameter vectors from the posterior distribution.

- For each parameter vector, simulate the PK model to predict drug concentration over time.

- For each time point, calculate the median prediction and the 5th and 95th percentiles to form a 90% prediction interval [26].

4. Analyze Output:

- The width of the prediction interval visually communicates the uncertainty in the model forecast, crucial for first-in-human (FIH) dose selection and trial simulations [5].

Protocol: Global Sensitivity Analysis with Sobol' Indices

This protocol identifies which parameters contribute most to output uncertainty, guiding resource allocation for more precise parameter estimation.

1. Generate Input Sample:

- Method: Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or Sobol' sequences.

- Range: Sample each parameter from its defined probability distribution (from Protocol 4.1, Step 2).

- Size: Create a sample matrix of size N × k, where k is the number of parameters. A typical N is 1000-10,000 per parameter [27].

2. Execute Model Simulations:

- Run the model for each parameter set in the sample matrix.

- Record the Quantity of Interest (QoI), e.g., AUC at steady state.

3. Calculate Sensitivity Indices:

- Method: Calculate Sobol' indices using variance-based methods [27].

- First-Order Index (S~i~): Measures the fractional contribution of a single parameter to the output variance.

- Total-Effect Index (S~Ti~): Measures the total contribution of a parameter, including its interactions with all other parameters.

4. Interpret Results:

- Priority: Parameters with high total-effect indices are the most influential sources of uncertainty and should be prioritized for further experimental refinement.

Implementing these protocols requires a combination of software tools and methodological frameworks.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UQ and SA

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in UQ/SA |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Software Environment | Core platform for statistical computing; hosts packages for UQ/SA (e.g., SEMsens for sensitivity analysis, bayesplot for MCMC diagnostics) [28]. |

| Python (PyTorch, TensorFlow, SciKit-Learn) | Software Environment | Flexible programming language with extensive libraries for ML, deep learning, and UQ methods like Deep Ensembles and Bayesian Neural Networks [26]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Algorithm / Method | A class of algorithms for sampling from probability distributions, fundamental for Bayesian parameter estimation and UQ [24]. |

| Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) | Method | Combines predictions from multiple models, weighting them by their posterior model probability, to produce more reliable and robust predictions than any single model [24]. |

| Monte Carlo Dropout (MCD) | Method | A technique to approximate Bayesian inference in Deep Neural Networks, providing uncertainty estimates for AI/ML predictions [26]. |

| Sobol' Indices | Metric | Variance-based global sensitivity measures that quantify a parameter's individual and interactive contribution to output uncertainty [27]. |

| PBPK/QSP Platform (e.g., Certara, ANSYS) | Commercial Software | Specialized software for building mechanistic Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models, increasingly integrating UQ features [5] [23]. |

Ignoring parameter uncertainty is a critical vulnerability in modern drug development, directly linked to costly late-stage failures and suboptimal dosing. The quantitative data and protocols presented herein demonstrate that a systematic approach to UQ and SA is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity. By adopting Bayesian estimation, propagating uncertainty via Monte Carlo methods, and using global SA to pinpoint key uncertainty drivers, development teams can replace overconfidence with quantified risk. This transition is pivotal for reversing Eroom's Law, building regulator trust, and ultimately delivering better, safer medicines to patients more efficiently.

A Practical Guide to Sensitivity Analysis Methods: From OAT to Global Variance-Based Techniques

Sensitivity Analysis (SA) is a critical methodology in computational modeling, defined as the study of how uncertainty in the output of a model can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input [17]. In the context of parameter uncertainty research, SA provides systematic approaches to understand the relationship between a model's N input variables, x = [x~1~, x~2~, ..., x~N~], and its M output variables, y = [y~1~, y~2~, ..., y~M~], where y = g(x) and g represents the model that maps inputs to outputs [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals dealing with complex models, selecting the appropriate SA approach is paramount for drawing reliable inferences from their models, particularly when making critical decisions about drug safety, efficacy, and development pathways.

The fundamental distinction in SA methodologies lies between local and global approaches, each with different philosophical underpinnings, mathematical frameworks, and application domains. Local sensitivity analysis is performed by varying model parameters around specific reference values, with the goal of exploring how small input perturbations influence model performance [17]. In contrast, global sensitivity analysis varies uncertain factors within the entire feasible space of variable model responses, revealing the global effects of each parameter on the model output, including any interactive effects [17] [29]. For models that cannot be proven linear, global sensitivity analysis is generally preferred as it provides a more comprehensive exploration of the parameter space [17].

The importance of SA extends across multiple research applications, including model evaluation, simplification, and refinement [17]. In drug development specifically, SA plays a crucial role within Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) frameworks, helping to optimize development stages from early discovery to post-market lifecycle management [5]. Understanding the distinctions between local and global approaches enables scientists to align their sensitivity analysis methodology with their specific research questions, model structures, and decision-making contexts.

Comparative Analysis: Local vs. Global Sensitivity Analysis

Fundamental Concepts and Methodological Differences

Local and global sensitivity analysis approaches differ fundamentally in their exploration of the parameter space and their interpretation of sensitivity measures. Local SA investigates the impact of input factors on the model locally, at some fixed point in the space of input factors, typically by computing partial derivatives of the output functions with respect to the input variables [29]. The sensitivity measure in local SA is usually based on the partial derivative of the output Y with respect to each input X~i~, evaluated at a specific point in the parameter space [30]. This approach essentially measures the slope of the output response surface at a nominated point, providing a localized view of parameter effects.

In practical implementation, local SA often employs One-at-a-Time (OAT) designs, where each input factor is varied individually while keeping all other factors fixed at baseline values [30] [29]. Although simple to implement and computationally efficient, OAT methods have a significant limitation: they do not fully explore the input space and cannot detect the presence of interactions between input variables, making them unsuitable for nonlinear models [30]. The proportion of input space which remains unexplored with an OAT approach grows superexponentially with the number of inputs, potentially leaving large regions of the parameter space uninvestigated [30].

Global SA, conversely, is designed to explore the input parameter space across its entire range of variation, quantifying input parameter importance based on characterization of the resulting output response surface [31]. Unlike local methods that provide sensitivity measures at specific points, global methods employ multidimensional averaging, evaluating the effect of each factor while all others are varying as well [29]. This comprehensive exploration enables global SA to capture interaction effects between parameters, which is especially important for non-linear, non-additive models where the effect of changing two factors is different from the sum of their individual effects [29].

The mathematical formulation of global SA typically requires specifying probability distributions over the input space, acknowledging that the influence of each input incorporates both the effect of its range of variation and the form of its probability density function [29] [32]. This contrasts with local methods, where variations are typically small and not directly linked to the underlying uncertainty in the parameter values.

Comparative Strengths, Limitations, and Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Local and Global Sensitivity Analysis Approaches

| Characteristic | Local Sensitivity Analysis | Global Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Space Exploration | Explores small perturbations around nominal values [17] | Explores entire feasible parameter space [17] |

| Core Methodology | Partial derivatives; One-at-a-Time (OAT) designs [30] [29] | Multidimensional averaging; Monte Carlo sampling [29] |

| Interaction Effects | Cannot detect interactions between parameters [17] [30] | Can quantify interaction effects [17] [29] |

| Computational Cost | Lower computational demands [17] [33] | Higher computational costs, especially for complex models [33] |