Mesh Convergence in FEA: A Complete Guide for Reliable Biomedical Simulations

This article provides a comprehensive guide to mesh convergence studies in Finite Element Analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in biomedical and drug development.

Mesh Convergence in FEA: A Complete Guide for Reliable Biomedical Simulations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to mesh convergence studies in Finite Element Analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in biomedical and drug development. It covers foundational principles, demonstrating why convergence is a non-negotiable pillar for credible computational results. The guide details systematic methodologies for performing convergence studies, including both h- and p-refinement techniques, and addresses common challenges like singularities and nonlinearities. Finally, it establishes a robust framework for validating FEA models against analytical solutions and experimental data, empowering scientists to build confidence in their simulations of medical devices, bioprinted tissues, and other critical biomedical systems.

What is Mesh Convergence and Why is it Critical for Biomedical FEA?

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is a fundamental computational technique for numerically solving differential equations arising in engineering and mathematical modeling, particularly for problems where analytical solutions are unavailable or impractical [1]. The method subdivides a large, complex physical system into smaller, simpler parts called finite elements, creating a mesh that transforms partial differential equations into solvable algebraic equations [1]. The reliability of these solutions hinges critically on the concept of convergence—the process whereby the approximate FEA solution stabilizes and approaches a true value as key numerical parameters are refined [2].

Achieving convergence transforms FEA from a mere approximation tool into a source of trustworthy results. This process ensures that the solution is not artificially dependent on numerical choices like mesh density, time step size, or load increment specification [2]. For researchers across disciplines, including drug development and biomedical engineering, establishing convergence is a non-negotiable step in validating computational models that inform critical decisions, from implant design to biomechanical interactions [3].

The Critical Role of Mesh Convergence Studies

Fundamental Principles

Mesh convergence is arguably the most foundational type of convergence in FEA. The core principle is straightforward: as the finite element mesh is progressively refined, the computed solution should approach a stable, asymptotic value [4]. The primary goal of a mesh convergence study is to find a mesh that is fine enough that further refinement does not yield relevant increases in accuracy, yet as coarse as possible to conserve computational resources such as computing time and memory space [4].

In practice, reaching the convergence limit is typically identified by monitoring the change in key results between successive refinement steps. A common criterion is less than 1% change in critical outcomes like displacement or stress values [4]. It is important to note that convergence behavior varies significantly depending on the physical quantity being examined. Displacements and primary variables typically converge more readily and with coarser meshes than higher-order results like stresses and strains, which often require more refined discretization due to their dependence on derivatives of the primary solution [4].

Quantitative Demonstration of Mesh Convergence

The following table summarizes data from a mesh convergence study conducted on an aluminum cantilever model, analyzing the influence of mesh density and element type on the calculated displacement at the beam's end [4].

Table 1: Mesh Convergence Study for Cantilever Displacement

| Model Type | Element Description | Target FE Size (mm) | Calculated Displacement (mm) | Relative Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam (Bernoulli) | - | - | 7.145 | Reference |

| Beam (Timoshenko) | - | - | 7.365 | Reference |

| Surface (Quad) | Coarse | 20.0 | 6.950 | - |

| Surface (Quad) | Medium | 10.0 | 7.210 | +3.74 |

| Surface (Quad) | Fine | 5.0 | 7.305 | +1.32 |

| Surface (Quad) | Very Fine | 2.5 | 7.340 | +0.48 |

| Surface (Tri) | Coarse | 20.0 | 6.750 | - |

| Surface (Tri) | Medium | 10.0 | 7.150 | +5.93 |

| Surface (Tri) | Fine | 5.0 | 7.290 | +1.96 |

| Surface (Tri) | Very Fine | 2.5 | 7.330 | +0.55 |

The data demonstrates several key principles. First, beam elements (which have analytical shape functions) show no mesh dependence in this simple case. Second, surface models consistently approach the more accurate Timoshenko beam solution (7.365 mm) as the mesh is refined, with the relative change between steps dropping below 1% at the finest refinement level. Third, quadrilateral elements generally demonstrate slightly superior convergence characteristics compared to triangular elements at equivalent mesh sizes [4].

Convergence behavior becomes even more critical when examining stress results. A separate study on a plate with a concentrated load monitored principal stress and strain at a critical point [4]. The results showed that with a target FE element length of 0.01 m, both stress and strain deviated by only about 0.2% from the previous refinement step, indicating satisfactory convergence for engineering purposes [4].

Methodological Approaches to Mesh Refinement

Two primary methodological approaches exist for achieving mesh convergence:

H-Method: This approach uses simple first-order linear or quadratic elements and improves solution accuracy by systematically increasing the number of elements (decreasing element size, 'h') in the model [2]. The computational time increases with the number of elements. The solution progressively approaches the analytical value with each refinement, and the goal is to find the mesh resolution where further refinement does not significantly alter the results [2].

P-Method: This method keeps the number of elements minimal and achieves convergence by increasing the order of the interpolation polynomials (element order, 'p') within each element [2]. While computationally efficient in terms of mesh generation, the computational time increases with element order as degrees of freedom rise exponentially. The P-method often achieves faster convergence for smooth solutions [2].

Table 2: Comparison of H-Method and P-Method Strategies

| Characteristic | H-Method | P-Method |

|---|---|---|

| Refinement Strategy | Decrease element size ('h') | Increase element order ('p') |

| Mesh Structure | Changes with refinement | Remains constant |

| Computational Cost | Increases with number of elements | Increases with element order |

| Implementation | Widely used in codes like Abaqus | Less common, requires high-order elements |

| Application Strength | General purpose, handles singularities | Efficient for smooth solutions |

Comprehensive Convergence Protocol for FEA Research

Workflow for Convergence Verification

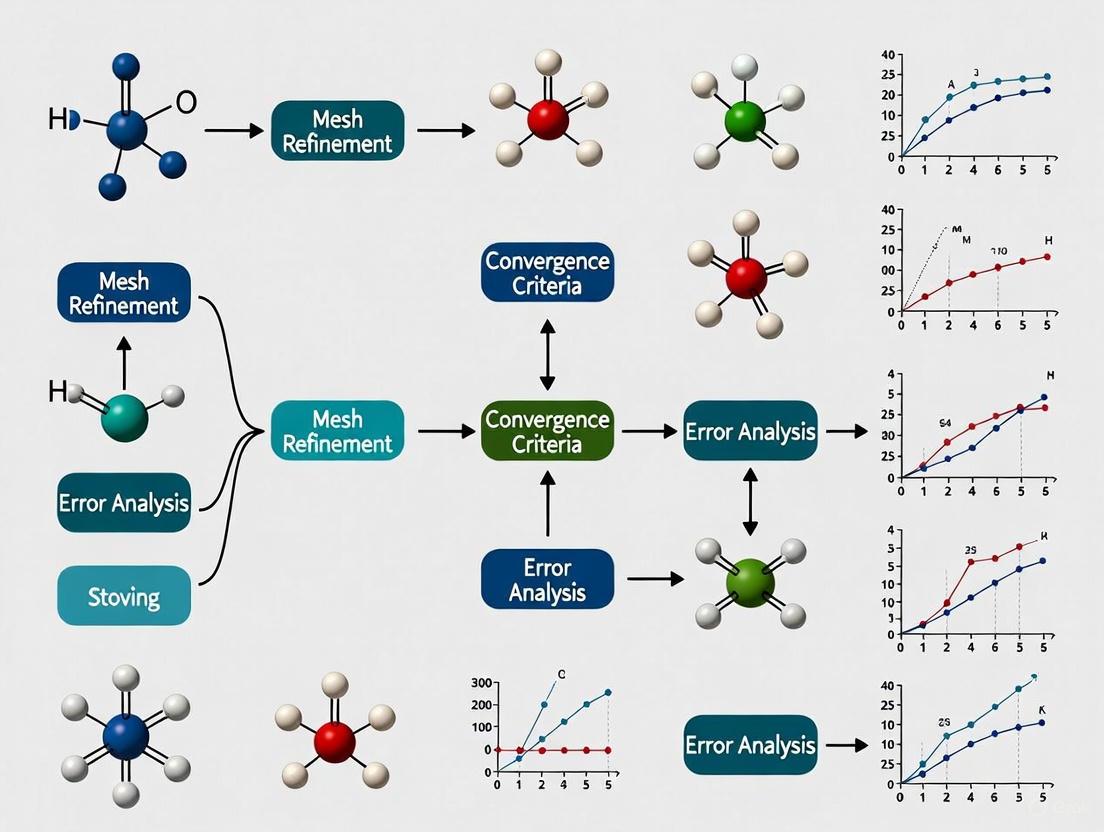

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for verifying convergence in finite element analysis, integrating mesh, time, and iterative convergence aspects.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Mesh Convergence

Objective: To determine a computationally efficient mesh that produces results independent of further mesh refinement for a given FEA model.

Materials and Software:

- FEA software with mesh generation and refinement capabilities (e.g., RFEM, Abaqus) [4] [2]

- Computer workstation with sufficient memory for multiple model solutions

- The physical model to be analyzed with defined geometry, material properties, loads, and boundary conditions

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Model Setup and Baseline Generation

- Create the FEA model with complete geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, and loading.

- Identify critical locations for result monitoring (e.g., maximum stress regions, points of interest). For accurate tracking, use geometrically defined nodes or result points that maintain consistent relative positions during mesh refinement [4].

- Generate an initial, relatively coarse mesh appropriate for the geometry.

Initial Solution and Result Recording

- Solve the model with the initial mesh.

- Record key results from the predefined critical locations, particularly displacements, stresses, strains, or other relevant quantities.

- Document computational resources used (solution time, memory requirements).

Systematic Mesh Refinement

- Refine the mesh globally or apply local refinement in critical regions where high stress gradients are anticipated or observed [4].

- For the h-method, reduce the target element size by a consistent factor (e.g., 1.5-2x refinement). For the p-method, increase the element order.

- Resolve the model and record the same key results and computational metrics.

Convergence Assessment

- Calculate the relative change in key results between successive refinement steps using the formula: [ \text{Relative Change (\%)} = \frac{|R{i} - R{i-1}|}{R{i-1}} \times 100\% ] where (R{i}) is the result at refinement step i.

- Plot results versus element size or degrees of freedom to visualize convergence behavior.

Termination Criteria Evaluation

- Continue the refinement process until the relative change in all critical results falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., 1-5% depending on required accuracy) [4].

- The mesh from the previous refinement step is typically selected as the converged mesh, providing an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If no convergence is observed with mesh refinement, investigate potential singularities (e.g., reentrant corners, point loads, crack tips) which may require special treatment [4] [2].

- For complex models, consider applying local mesh refinement only in critical regions rather than globally to reduce computational burden [4].

- If stresses fail to converge while displacements do, this often indicates the need for further localized refinement in high-stress gradient regions [4].

Advanced Convergence Considerations

Convergence in Nonlinear Analysis

Convergence challenges become significantly more complex when nonlinearities are introduced into an FEA model through material behavior (e.g., plasticity, hyperelasticity), boundary conditions (e.g., contact, friction), or geometric effects (large deformations) [2]. Unlike linear problems with unique solutions, nonlinear problems may have zero, one, many, or infinite solutions, and the solution depends on the entire load history [2].

Solving nonlinear problems requires breaking the total load into smaller increments and employing iterative methods like Newton-Raphson or Quasi-Newton techniques to find equilibrium at each load step [2]. The convergence criterion for these iterations typically requires that the residual forces (the difference between external and internal forces) fall below specified tolerances [2]:

[ P - I = R \leq \text{Tolerances} ]

Time Integration Convergence

For dynamic simulations involving structural vibrations, impact analysis, or transient thermal behavior, time integration accuracy becomes critical for convergence [2]. The time step must be small enough to capture all relevant physical phenomena while balancing computational cost. Higher-order time integration methods (e.g., implicit/explicit Runge-Kutta) provide improved accuracy but at increased computational expense [2]. Most commercial FEA packages provide user-specified parameters to control time integration accuracy, such as half-increment residual tolerance or maximum change allowed in field variables per increment [2].

Methodological Gaps in Current Practice

Recent literature reviews identify persistent methodological shortcomings in FEA research, particularly in biomedical applications. Common issues include: oversimplified material properties (e.g., uniform bone characteristics); static loading conditions neglecting dynamic physiological forces; idealized fracture geometries missing clinical variation; and unverified interface conditions that may exaggerate implant stability [3]. These gaps highlight the importance of comprehensive convergence studies beyond mere mesh refinement, including material modeling and loading conditions, to ensure clinically relevant results [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FEA Convergence Studies

| Reagent Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mesh Generation Software | Creates finite element discretization of physical geometry | Built-in meshers in FEA packages (Abaqus, ANSYS, RFEM); h-refinement vs. p-refinement capabilities [4] [2] |

| Convergence Metrics Calculator | Quantifies differences between refinement iterations | Custom scripts or built-in tools to calculate relative change (%) in key results; visualization of convergence plots [4] |

| Result Interpolation Tools | Enables consistent result comparison across different meshes | Spatial interpolation algorithms; result points at fixed geometric locations [4] |

| Nonlinear Solution Algorithms | Solves equilibrium equations for nonlinear problems | Newton-Raphson method; Quasi-Newton methods; arc-length methods for unstable structural responses [2] |

| Time Integration Schemes | Advances solution through time in dynamic analyses | Implicit vs. explicit methods; Runge-Kutta methods; automatic time stepping controls [2] |

Convergence studies represent the critical bridge between approximate computational results and trustworthy scientific findings in finite element analysis. A systematic approach to convergence—encompassing mesh refinement, nonlinear solution techniques, and time integration accuracy—ensures that FEA results reflect the underlying physics rather than numerical artifacts. For researchers across disciplines, particularly in safety-critical fields like biomedical device development, rigorous convergence protocols are not merely academic exercises but essential components of responsible computational science. By adopting the comprehensive frameworks and methodologies outlined in this document, scientists can significantly enhance the reliability and credibility of their computational findings, ultimately leading to more robust designs and discoveries.

In biomedical engineering, the concept of convergence represents the integration of distinct technological disciplines to create innovative solutions that surpass the capabilities of any single field. This paradigm is exemplified by the synergy between advanced manufacturing like 3D bioprinting and computational modeling techniques such as Finite Element Analysis (FEA). The critical process of mesh convergence within FEA ensures that digital simulations accurately predict physical behavior, thereby validating designs before they are ever physically realized [5]. This foundational accuracy is paramount across biomedical applications, from engineered tissues that mimic physiological functions to patient-specific implants that restore biological function.

The transformative potential of this convergence is accelerating the development of personalized medical solutions. By combining the structural precision of 3D printing with the predictive power of converged computational models, researchers can create biocompatible constructs with enhanced accuracy and functionality [6] [7]. This approach is revolutionizing regenerative medicine, drug development, and implant design, ultimately leading to more effective patient-specific therapeutic outcomes.

Convergence in 3D Bioprinting and Nanotechnology

The integration of 3D bioprinting with nanotechnology represents a frontier of convergence in biomedicine. This synergy enables the fabrication of complex, functional structures with unprecedented molecular-level control. 3D printing provides the macro-scale structural framework, while nanotechnology introduces dynamic, smart functionalities at the micro and nano scales [6].

Key convergent technologies in this domain include:

- Smart Implants: 3D-printed structures incorporating nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, hydroxyapatite) that provide enhanced mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and bio-responsiveness [6].

- Targeted Drug Delivery Systems: Nanoengineered 3D-printed scaffolds that enable controlled release of therapeutic agents in response to specific biological stimuli [6].

- Bioresponsive Tissue Scaffolds: Constructs that dynamically interact with their biological environment to promote tissue integration and regeneration [6].

The incorporation of functional nanomaterials into 3D bioprinting processes is spearheading a revolutionary change in biomedical engineering. These nanomaterials endow 3D-printed constructs with novel characteristics including enhanced mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, antibacterial functionality, and bio-responsiveness [6]. These capabilities facilitate the development of advanced medical devices and implants that closely mimic the properties of natural tissues.

Research Reagent Solutions for Convergent Bioprinting

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for convergent 3D bioprinting applications.

| Category/Name | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Bioinks (Alginate, Chitosan, Gelatin) | Mimic native ECM; provide structural support and biocompatibility [8]. | Soft tissue engineering, cell encapsulation [8]. |

| Synthetic Polymers (PCL, PLA, PVA) | Provide superior mechanical properties and tunable degradation rates [8]. | Load-bearing bone scaffolds, customized implants [8]. |

| Functional Nanomaterials (Graphene, CNTs, Metal Nanoparticles) | Enhance electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and bio-responsive behavior [6]. | Neural interfaces, smart implants, biosensors [6]. |

| Photoinitiators (e.g., for GelMA) | Enable UV-induced cross-linking of bioinks for rapid solidification [8]. | High-resolution hydrogel constructs [8]. |

Fundamental Principles of Mesh Convergence in FEA

Mesh convergence is a critical computational principle that ensures the reliability and accuracy of Finite Element Analysis. It refers to the process of progressively refining a model's mesh until the results stabilize within an acceptable tolerance, indicating that the solution is no longer significantly affected by element size [9] [5]. In biomedical applications, where predicting stress distribution, strain, and thermal conductivity is essential for patient safety, neglecting this process can lead to dangerously inaccurate conclusions.

The formal method for establishing mesh convergence involves creating a convergence curve, where a critical result parameter (such as peak stress) is plotted against a measure of mesh density [5]. As the mesh is refined, the results should asymptotically approach a stable value, indicating convergence.

Protocol: Conducting a Mesh Convergence Study

Application Note: This protocol provides a standardized methodology for performing a mesh convergence study, essential for validating any FEA model in biomedical research, from implant mechanics to tissue scaffold design.

Principle: To determine the mesh density at which a chosen output (e.g., maximal stress, displacement) becomes independent of further element refinement, thereby ensuring result accuracy and computational efficiency [9] [5].

Materials and Software:

- FEA Software (e.g., Abaqus, Ansys, COMSOL)

- 3D Geometry of the model (e.g., from CAD software or CT scan)

- Computational Workstation

Procedure:

- Model Setup: Develop the initial FEA model with complete geometry, material properties, and boundary conditions representative of the biomedical scenario [10].

- Initial Mesh Generation: Create a starting mesh using the software's default settings or an initial, relatively coarse element size estimate [9].

- Solve and Record: Run the simulation and record the value of the critical output parameter from the region of interest.

- Systematic Refinement: Refine the mesh globally or, more efficiently, locally in regions of interest (e.g., stress concentrations, geometric features) [5].

- Iterate and Plot: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for at least 3-5 different mesh density levels. Plot the critical result parameter against the number of elements or average element size.

- Analyze Convergence: Determine the point where the change in the result between successive refinements falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 2-5%). The mesh prior to this point is often considered sufficiently converged for engineering purposes [9] [11].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Lack of Convergence: If results do not stabilize, check for modeling errors such as sharp re-entrant corners with no radius, which can create a theoretical stress singularity [5].

- Computational Limits: For very large models, use sub-modeling techniques to perform a detailed convergence study only on the critical region.

- Element Type Consideration: Higher-order elements (e.g., QUAD8, C3D10) often converge faster and more accurately than linear elements (e.g., QUAD4) [9].

Diagram 1: Mesh Convergence Study Workflow. This flowchart outlines the iterative process of solving and refining a finite element model to achieve a mesh-independent result.

Applied Case Study: FEA and Convergence in Dental Implant Design

A compelling application of convergence in biomedical FEA is the design and analysis of restorative dental posts for endodontically treated teeth (ETT). A 2025 study used 3D FEA to assess stress distribution in a severely damaged mandibular first molar restored with different configurations of titanium posts [10].

Protocol: FEA of Restored Endodontically Treated Tooth

Application Note: This protocol details the steps for creating a patient-specific FEA model to evaluate the mechanical performance of dental restorations, informing clinical decisions for optimal stress distribution.

Principle: To simulate occlusal loading conditions on a virtual model of a restored tooth derived from medical imaging data, identifying stress concentrations that may lead to clinical failure [10].

Materials and Software:

- CBCT Scan Data

- Image Processing Software (e.g., MIMICS)

- 3D Modeling Software (e.g., SolidWorks)

- FEA Software (e.g., Abaqus)

Procedure:

- Model Generation: Import and process a high-resolution CBCT scan of a human mandibular first molar using image processing software to create a 3D stereolithography (STL) file of the enamel and dentin structures [10].

- Geometric Reconstruction: Combine the enamel and dentin geometries in CAD software. Model supporting structures, including the periodontal ligament (PDL) as a uniform 200 μm layer and the surrounding alveolar bone [10].

- Restoration Modeling: Modify the tooth model to simulate clinical procedures:

- Create an access cavity and shape root canals.

- Model post spaces in the canals (e.g., distal, mesiobuccal, mesiolingual).

- Insert virtual models of the posts (e.g., titanium FILPOST).

- Build up the core with composite resin and design a zirconia crown [10].

- Material Properties Assignment: Assign linear, isotropic, and homogeneous material properties to all components based on literature values (Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio) [10].

- Mesh Generation and Convergence: Generate a finite element mesh and perform a convergence study as described in Protocol 3.1 to determine the appropriate mesh density.

- Boundary Conditions and Loading: Constrain the outer surface of the alveolar bone. Apply a simulated occlusal load (e.g., 200 N) at a specific angle on the crown's occlusal surface [10].

- Analysis and Post-Processing: Solve the model and analyze the resulting stress distributions (e.g., von Mises stress) at critical locations: the occlusal surface, finish line, furcation area, and along the root canal.

Key Findings from Case Study [10]:

- The model with a single distal post (Model D) recorded the highest stress values at all assessed locations.

- The model with two posts in the distal and mesiolingual canals (Model DML) reported the lowest stress values.

- The use of two posts significantly reduced stress concentrations compared to a single-post design, suggesting enhanced structural durability.

Table 2: Maximum stress values (MPa) reported for different dental post configurations in a mandibular molar FEA study [10].

| Tooth Location | Model D (Single Post) | Model DMB (Distal + Mesiobuccal) | Model DML (Distal + Mesiolingual) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occlusal Surface | Highest Value | Intermediate Value | Lowest Value |

| Finish Line | Highest Value | Intermediate Value | Lowest Value |

| Furcation Area | Highest Value | Intermediate Value | Lowest Value |

| Root Canal (7mm from apex) | Highest Value | Intermediate Value | Lowest Value |

Advanced Convergence: Integrating FEA with Machine Learning

A frontier in computational convergence is the coupling of FEA with Machine Learning (ML) to create ultra-efficient predictive models. This approach is particularly valuable for characterizing the mechanical behavior of complex 3D-printed meta-biomaterials used in orthopedic implants, where traditional FEA can be computationally prohibitive [11].

In one implementation, an ML model, specifically a Physics-Informed Artificial Neural Network (PIANN), was trained using a large dataset generated from an automated FEA workflow [11]. The trained network learned to predict optimal FEA modeling parameters directly from experimental force-displacement data, thereby inverting the conventional process. This convergence of ML and FEA resulted in accurate simulations that agreed with experimental observations while outperforming state-of-the-art models in terms of quantitative and qualitative accuracy [11].

Diagram 2: ML-Augmented FEA Workflow. This diagram illustrates the data-driven process of using machine learning to predict accurate parameters for finite element simulations, enhancing model reliability and efficiency.

The critical role of convergence in biomedical applications is undeniable, creating a powerful synergy between 3D bioprinting, advanced materials, and computational mechanics. Mesh convergence studies within FEA provide the foundational assurance that digital prototypes will behave as predicted in the physical world, de-risking the development of patient-specific implants and tissue constructs. Furthermore, the emerging convergence of FEA with machine learning heralds a new era of computational efficiency, enabling the rapid exploration and optimization of complex biomedical designs that were previously infeasible. As these fields continue to co-evolve, they will accelerate the translation of innovative engineering solutions into clinical practice, ultimately advancing the frontier of personalized medicine and improving patient outcomes.

In finite element analysis (FEA), mesh convergence studies are fundamental for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of computational simulations. For researchers and scientists in fields including drug development and biomechanics, understanding the convergence behavior of key output parameters—displacements, stresses, and error norms—is critical for validating model predictions [12]. The process involves systematically refining the finite element mesh until the solution stabilizes, indicating that further refinement will not substantially change the results [13]. This document establishes detailed application notes and protocols for conducting mesh convergence studies, with specific emphasis on quantifying convergence through displacement, stress, and mathematical error norms.

The core principle of mesh convergence is that as element sizes decrease (h-refinement) or element order increases (p-refinement), the numerical solution should approach the true analytical solution [12]. However, different physical quantities converge at different rates, and understanding these differences is essential for correct interpretation of FEA results. For instance, displacements typically converge faster than stresses, as stresses are derived from displacement derivatives [14]. This article provides a structured framework for evaluating convergence across these different quantities, with specific application to both compressible and nearly-incompressible material models relevant to biological tissues and pharmaceutical materials [15].

Theoretical Foundation

Displacement and Stress Convergence

In finite element analysis, the displacement field represents the primary solution variable, with the stress field derived from these displacements through constitutive relationships. The accuracy of each field exhibits distinct convergence characteristics during mesh refinement.

Displacement solutions typically show monotonic convergence toward the true solution with mesh refinement. For example, in a cantilever beam model with quadrilateral elements (QUAD4), the tip displacement progressively approaches the theoretical value as the number of elements increases [9]. Stress solutions, being dependent on displacement derivatives, generally converge more slowly than displacements and may exhibit oscillatory behavior during initial refinement stages [14]. This occurs because stresses are calculated from strain-displacement matrices that amplify numerical errors present in the displacement solution.

Higher-order elements demonstrate superior convergence characteristics compared to linear elements. Research shows that 8-node quadrilateral elements (QUAD8) can achieve converged stress solutions with far fewer elements than their 4-node counterparts [9]. In some cases, higher-order elements may even produce constant stress solutions regardless of mesh density for simple problems, immediately providing the converged answer [9].

Error Norms in Convergence Analysis

Error norms provide quantitative measures of solution accuracy in finite element analysis, enabling researchers to objectively evaluate convergence during mesh refinement studies.

- L2-Norm for Displacements: The L2-norm measures the root-mean-square error in displacement solutions over the entire domain. It is defined as the square root of the integral of the squared difference between exact and finite element solutions [14]. This norm provides a global measure of displacement accuracy and typically converges at a rate of (p+1), where (p) is the polynomial order of the element shape functions [12].

- Energy Norm: The energy norm measures error in the energy of the system, incorporating both displacement and stress fields. It converges at a rate of (p) and is particularly useful for evaluating overall solution quality [12] [15].

- L2-Norm for Stresses: This norm quantifies errors in stress solutions, which are critical for failure analysis and strength predictions. Stress L2-norms typically converge more slowly than displacement norms due to their derivation from displacement derivatives [14].

Table 1: Error Norms in Finite Element Convergence Analysis

| Error Norm Type | Physical Interpretation | Convergence Rate | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| L2-Norm (Displacement) | Global displacement error | (p+1) | Overall deformation accuracy |

| Energy Norm | System energy error | (p) | General solution quality |

| L2-Norm (Stress) | Global stress error | Typically ( | Stress accuracy assessment |

Special Considerations for Nearly-Incompressible Materials

Nearly-incompressible materials, such as rubber-like materials and soft biological tissues, present particular challenges for finite element analysis. These materials experience minimal volume change under loading, with Poisson's ratios approaching 0.5 [15]. Standard displacement-based finite elements often exhibit "volumetric locking," severely underestimating displacements and producing inaccurate stress distributions [15].

Specialized element formulations are required to address this limitation. Bubble-function enriched elements (bES-FEM, bFS-FEM) introduce additional displacement modes that prevent locking while maintaining stability [15]. Mixed displacement-pressure formulations ((u-p) elements) separately interpolate displacements and pressure, effectively bypassing the locking phenomenon [15] [14]. For nearly-incompressible materials, researchers should prioritize these specialized elements to ensure proper convergence of both displacement and stress fields.

Quantitative Data on Convergence Behavior

Experimental convergence studies provide concrete data on expected convergence rates for different element types and analysis conditions. These quantitative benchmarks help researchers set appropriate expectations for mesh refinement studies.

Table 2: Exemplary Convergence Rates for Triangular Elements in Elasticity

| Problem Type | Element Formulation | Displacement Error Convergence Rate | Stress Error Convergence Rate | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressible Elastic Plate | Higher-order triangular | 1.97 | 2.90 (Recovered) | [14] |

| Nearly-Incompressible Elastic Plate | Higher-order triangular | 0.98 | 1.78 (Recovered) | [14] |

| Nearly-Incompressible Elasticity | bES-FEM/bFS-FEM (Bubble-enriched) | Optimal rates achieved | Optimal rates achieved | [15] |

Research demonstrates that error recovery techniques significantly improve convergence rates for stress solutions. The superconvergent patch recovery (SPR) technique, which fits higher-order polynomials to stress sampling points, can produce stress convergence rates exceeding displacement convergence rates [14]. For nearly-incompressible materials, standard elements exhibit significantly degraded convergence (approximately 0.98 for displacements), while specialized formulations restore optimal convergence behavior [14].

The number of elements required for convergence varies substantially by element type. For a simple cantilever beam model, QUAD8 elements achieved the exact solution (300 MPa maximum stress) with just a single element, while QUAD4 elements required approximately 50 elements along the length to achieve results within 1% of the converged value (297 MPa vs. 299.7 MPa) [9].

Experimental Protocols for Convergence Studies

General Mesh Convergence Protocol

This protocol establishes a standardized methodology for performing mesh convergence studies applicable to a wide range of finite element analyses.

Objective: To determine the mesh density required for results of acceptable accuracy while minimizing computational resources.

Workflow:

Procedure:

Problem Definition: Clearly define the physical problem, including geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, and loading. For nonlinear problems, include all relevant nonlinearities (geometric, material, contact).

Quantity of Interest Identification: Identify specific solution quantities to monitor during convergence studies. These typically include:

- Critical displacements at key locations

- Maximum and minimum stress values

- Stress concentrations at critical features

- Reaction forces at supports

- For error norm calculation: select appropriate norms (L2, energy) [14]

Initial Mesh Creation: Generate an initial coarse mesh appropriate for the problem geometry. Document initial mesh statistics:

- Number of nodes and elements

- Element type and order (linear/quadratic)

- Minimum and average element quality metrics

Finite Element Solution: Solve the finite element model with the current mesh. For nonlinear problems, ensure equilibrium convergence is achieved.

Result Extraction: Extract the identified quantities of interest from the solution. For stress values, note the sampling location (nodes, Gauss points, element centers).

Mesh Refinement: Systematically refine the mesh using one of these approaches:

Convergence Assessment: Compare current results with previous mesh solution. Calculate percentage differences for each quantity of interest. Convergence is typically achieved when differences fall below 2-5% for most engineering applications [9].

Termination: When results stabilize within acceptable tolerances, the solution has converged. The penultimate mesh generally provides the optimal balance of accuracy and computational efficiency.

Error Norm Calculation Protocol

This specialized protocol details the calculation of mathematical error norms for rigorous quantification of solution accuracy.

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate finite element solution accuracy using L2 and energy error norms.

Workflow:

Procedure:

Reference Solution Preparation:

- For problems with analytical solutions, compute exact displacement and stress fields

- For complex problems without analytical solutions, use a highly refined "overkill" mesh solution as reference

- Ensure reference solution accuracy through verification procedures

Finite Element Analysis: Perform analysis with the current mesh density. Export complete displacement and stress fields.

Solution Recovery: Implement recovery procedures to improve solution accuracy:

- Superconvergent Patch Recovery (SPR): Fit higher-order polynomials to stress values at optimal sampling points (Gauss points) over patches of elements [14]

- Displacement Recovery: Fit higher-order polynomials to nodal displacements over element patches to obtain improved displacement derivatives [14]

Error Norm Calculation: Compute mathematical norms of the solution error:

Effectivity Index Calculation: Compute the effectivity index (θ) as the ratio of the estimated error to the actual error. This validates the error estimation procedure, with ideal effectivity index approaching 1.0 [14].

Convergence Rate Documentation: Plot error norms against element size on log-log scales. Calculate convergence rates from the slope of these curves for comparison with theoretical expectations.

Protocol for Nearly-Incompressible Materials

Objective: To ensure proper displacement, stress, and error norm convergence for nearly-incompressible materials.

Procedure:

Element Selection: Choose elements specifically designed for nearly-incompressible behavior:

Material Definition: Precisely define material properties with Poisson's ratio approaching 0.5 (typically >0.49 for rubber-like materials, 0.499+ for biological tissues).

Convergence Monitoring: Pay particular attention to:

- Pressure field oscillations (check for checkerboarding patterns)

- Volume change errors (should be minimal)

- Stress accuracy in regions of constraint

Specialized Error Norms: Implement error norms specific to mixed formulations, including separate displacement and pressure error measures [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Finite Element Convergence Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Convergence Studies |

|---|---|---|

| FEA Software Platforms | Ansys Mechanical [13] | Provides automated mesh convergence tools and adaptive refinement capabilities |

| Element Formulations | QUAD8/QUAD4 [9], bES-FEM/bFS-FEM [15] | Different element technologies with distinct convergence characteristics |

| Error Assessment Tools | L2 Norm Calculators [14], Energy Norm Algorithms [15] | Quantify solution errors for rigorous convergence assessment |

| Reference Solutions | Analytical Benchmarks [9], Overkill Meshes [14] | Provide "true" solutions for error calculation |

| Mesh Generation Tools | Adaptive Meshing Algorithms [13], Local Refinement Tools [13] | Enable systematic mesh refinement in critical regions |

| Visualization Packages | Stress Contour Plotters, Convergence Graph Tools | Identify convergence patterns and problem areas |

Mesh convergence studies represent a critical step in validating finite element analyses across scientific and engineering disciplines. Through systematic application of the protocols outlined herein, researchers can confidently establish the accuracy of displacement, stress, and error norm predictions. Particular attention should be paid to material-dependent considerations, especially for nearly-incompressible biological and pharmaceutical materials requiring specialized element formulations. The quantitative framework presented enables objective assessment of solution quality, ensuring reliable computational results for research and development applications.

In Finite Element Analysis (FEA), a mesh convergence study is a critical process for ensuring that a computational model's predictions are accurate and not unduly influenced by the discretization choices made during model creation. It involves progressively refining the mesh (increasing the number of elements) and observing the stabilization of key output quantities. Ignoring this essential procedure can lead to false positives, where non-converged results are mistaken for valid predictions, and unreliable predictions that fail to represent the true physical behavior of the system under investigation. This application note details the protocols for conducting robust convergence studies, framed within the broader thesis that such studies are fundamental to credible computational research in biomechanics and engineering.

Quantitative Evidence: The Impact of Discretization

The following tables summarize common pitfalls and quantitative outcomes associated with inadequate mesh convergence.

Table 1: Categories of Modeling Errors in FEA [16]

| Error Category | Description | Impact on Model Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Idealisation Errors | Simplifications of mechanical behaviour (e.g., modelling a plate as a beam), inaccurate mass assignment, erroneous boundary conditions. | Cannot be corrected by mesh refinement alone; requires structural model changes. |

| Discretization Errors | Mesh is too coarse, leading to unconverged modal data; poor element shape sensitivity; truncation errors from order reduction. | Directly addressed and mitigated through mesh convergence studies. |

| Parameter Errors | Incorrect assumptions for material properties (Young's modulus), geometric properties (shell thickness), or non-structural mass. | Parameter updating can be performed, but requires a converged mesh for reliable results. |

Table 2: Convergence Study Outcomes and Interpretations

| Observed Outcome | Possible Interpretation | Risk of Ignoring Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Results change significantly with mesh refinement. | Solution is mesh-dependent; current mesh is too coarse. | False Positive: An incorrect solution is accepted as correct. |

| Results stabilize within an acceptable tolerance. | Solution is mesh-converged; results are reliable for the defined physics. | N/A - The study has been correctly performed. |

| Results oscillate or diverge with refinement. | Potential existence of model structure errors (e.g., ill-posed boundary conditions) or numerical instabilities. | Unreliable Prediction: The model is not fit for purpose, leading to misguided conclusions. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Basic Mesh Convergence Study

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for performing a h-convergence study, where the mesh size (h) is systematically reduced.

Problem Definition and Quantity of Interest (QoI) Selection:

- Define the specific output variable(s) to monitor for convergence. Common QoIs include:

- Maximum von Mises stress in a critical region.

- Maximum displacement at a loaded point.

- Natural frequency of a specific mode.

- Define an acceptable convergence tolerance (e.g., 2% change between successive refinements).

- Define the specific output variable(s) to monitor for convergence. Common QoIs include:

Initial Mesh Generation:

- Create an initial, relatively coarse mesh that captures the essential geometry.

- Document the initial mesh statistics: number of elements, number of nodes, and element type.

Iterative Solution and Refinement:

- Run the FEA simulation and record the value of the selected QoI(s).

- Refine the mesh globally or in areas of high stress/strain gradients. Adaptive meshing techniques can automate this process.

- For each refinement level, repeat the simulation and record the QoI(s) and mesh statistics.

- Continue until the change in the QoI(s) between two consecutive refinements is less than the pre-defined tolerance.

Data Analysis and Reporting:

- Plot the QoI(s) against a measure of mesh density (e.g., number of elements, element size).

- Confirm the solution is asymptotically approaching a stable value.

- In publications, report the final mesh density and the convergence behavior as evidence of result reliability [17].

Protocol for Integration with Model Updating

For models being updated with experimental data, convergence is equally critical. The following workflow integrates these processes.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for FEA model validation, highlighting the prerequisite of mesh convergence before parameter updating [16].

- Sensitivity Analysis: This step involves computing the sensitivity of model outputs (e.g., natural frequencies) to changes in updating parameters (e.g., material properties). The relationship is linearized as:

ε_z = z_m - z(θ) ≈ r_i - G_i(θ - θ_i), whereG_iis the sensitivity matrix [16]. A converged mesh is essential for a stable and meaningful sensitivity matrix. - Parameter Estimation & Model Updating: Using a weighted least-squares approach, model parameters are adjusted to minimize the difference between analytical predictions and test data. The objective function is often of the form

J = ε_z^T W_z ε_z + (θ - θ_0)^T W_θ (θ - θ_0), which minimizes the residual while penalizing large parameter changes from their initial valuesθ_0[16]. - Validation Assessment: The updated model must be assessed for its ability to predict system behavior under conditions not used in the updating process. A model updated using a non-converged mesh will fail this predictive assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Robust FEA Convergence Study

| Item | Function & Relevance to Convergence |

|---|---|

| FEA Software with Solver Verification | The foundation. Software must use verified numerical solvers. Without this, convergence studies are meaningless. |

| Mesh Generation Tool | Creates the discrete model. Must support both global and local (adaptive) refinement capabilities. |

| Convergence Metric | A predefined criterion (e.g., 2% change in max stress) to objectively stop the refinement process. |

| Parameter Selection Algorithm | Identifies the most sensitive parameters for model updating, preventing ill-conditioning by focusing on influential parameters [16]. |

| Regularization Method | Addresses ill-conditioned systems common in model updating (e.g., Tikhonov regularization) to ensure stable and physically meaningful parameter corrections [16]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the computational resources needed to run multiple iterations of a high-fidelity model rapidly. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Can be integrated to create surrogate models, drastically reducing the time required for repeated analyses in convergence studies and parameter optimization [18]. |

In Finite Element Analysis (FEA), mesh convergence describes a solution that becomes stable and does not change significantly with further mesh refinement. Achieving mesh convergence is fundamental to ensuring the accuracy and reliability of simulation results, as it confirms that the discretization error introduced by modeling a continuous structure with finite elements is acceptably small [12]. This document uses the universally recognized cantilever beam example to establish a clear protocol for conducting mesh convergence studies, providing researchers with a practical framework applicable to complex analyses in fields including biomechanics and medical device development.

The cantilever beam, a simple structural member fixed at one end and free at the other, serves as an excellent analog for many biological and mechanical structures, from micro-scale implant struts to macro-scale architectural components. Its well-understood theoretical behavior provides a robust benchmark for validating numerical models [19] [20]. The core principle of a convergence study is to iteratively refine the mesh and observe the change in a Quantity of Interest (QoI), such as displacement or stress, until the solution stabilizes within a pre-defined tolerance [21] [22].

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

The "h-" and "p-" Refinement Methods

Two primary strategies exist for improving solution accuracy in FEA:

- h-refinement: Reducing the characteristic size (

h) of elements in the mesh. This method increases the number of elements and nodes [12]. - p-refinement: Increasing the polynomial order (

p) of the element's shape functions. This enhances the element's ability to represent complex stress fields without changing the mesh density [12].

For many practical applications, particularly with standard element types, the h-refinement method is the most straightforward and commonly adopted approach.

Quantifying Convergence and Error

Convergence is quantitatively assessed by tracking the QoI across multiple refinement steps. The relative change between successive simulations is calculated, and convergence is typically declared when this change falls below a target threshold (e.g., 1-2%) [21]. For a more rigorous analysis, error norms can be computed. The L2-norm (displacement error) and energy-norm (stress error) are standard measures, with the expected convergence rates being p+1 and p, respectively, where p is the order of the element [12].

Experimental Protocol: A Mesh Convergence Study on a Cantilever Beam

This protocol outlines the systematic procedure for performing a mesh convergence study, using a cantilever beam as the test case.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 1: Key materials and software used in the cantilever beam convergence study.

| Item Name | Specification / Example | Primary Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cantilever Beam Specimen | Aluminum, Length=100 mm, Cross-section=20x1 mm [21] | Serves as the physical or numerical test article for analysis. |

| FEA Software Platform | ANSYS, ABAQUS, SAP2000, or equivalent [19] [20] | Provides the computational environment for discretization and solving. |

| Mesh Generation Tool | Integrated within FEA platform | Creates the finite element mesh with controllable parameters. |

| Convergence Metric | Maximum Displacement / Maximum Von Mises Stress [21] [12] | The specific QoI monitored to assess solution stability. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow of a mesh convergence study.

Step 1: Model Setup and Initial Meshing

- Create a geometric model of a cantilever beam with defined dimensions and material properties (e.g., Young's Modulus = 70 GPa for aluminum) [21].

- Apply a representative load (e.g., a 1 kN point load at the free end) and boundary conditions (fully fixed at one end).

- Generate an initial, relatively coarse mesh. The choice of element type (e.g., linear quadrilateral vs. triangular) can influence the convergence path and should be noted [21].

Step 2: Iterative Solution and Refinement

- Solve the FEA model and record the QoI, such as the displacement at the free end.

- Systematically refine the mesh. For global refinement, reduce the average element size across the entire model. For greater efficiency, use local mesh refinement in regions with high stress gradients, ensuring a smooth transition to coarser areas [12] [22].

- Repeat the solve-and-record process for at least three to four progressively finer meshes to establish a trend [22].

Step 3: Convergence Assessment

- Calculate the relative difference for the QoI between successive mesh refinement levels.

- Plot the QoI against a measure of mesh density (e.g., number of nodes or element size).

- Declare convergence when the relative change between the last two iterations is below a pre-defined tolerance (e.g., <1-2%) [21].

Data Presentation and Analysis

The results from the convergence study should be compiled into a table for clear comparison and trend analysis. Table 2: Example results from a mesh convergence study of a cantilever beam under a 1 kN end load.

| Mesh Density Level | Number of Elements | Max Displacement (mm) | Relative Change in Displacement (%) | Max Von Mises Stress (MPa) | Relative Change in Stress (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 100 | 7.10 | - | 285 | - |

| Medium | 500 | 7.32 | 3.00 | 310 | 8.77 |

| Fine | 2000 | 7.35 | 0.41 | 325 | 4.84 |

| Very Fine | 8000 | 7.36 | 0.14 | 328 | 0.92 |

Analysis of Results:

- Displacement Convergence: Displacements, being a global measure, typically converge rapidly. In this example, the displacement stabilizes after the "Fine" mesh, with a change of only 0.14% to the "Very Fine" mesh [21].

- Stress Convergence: Stresses, being derivative quantities, converge more slowly. The stress is still changing by 0.92% in the final step, suggesting that further refinement may be needed for highly accurate stress values [21] [12].

Experimental Validation and Model Updating

A converged computational model gains full credibility when validated against experimental data. This process closes the loop of the "Simulation-Verification-Validation" cycle.

Experimental Modal Validation Protocol

For dynamic analyses, such as predicting natural frequencies, the following validation protocol is employed:

- Experimental Setup: A steel cantilever beam is instrumented with accelerometers at multiple points along its length [20].

- Data Acquisition: The beam is excited (e.g., with an impact hammer), and its dynamic response is recorded. Through techniques like Frequency Domain Decomposition (FDD), the experimental natural frequencies and mode shapes are extracted [19] [20].

- Model Updating: The FEA model's input parameters (e.g., material properties, boundary conditions) are iteratively adjusted within physical bounds to minimize the discrepancy between simulated and experimental results. The Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC) is used to quantitatively compare mode shapes [20]. A MAC value above 0.9 indicates excellent correlation [20].

Integrated Workflow for Validated Analysis

The diagram below outlines the comprehensive workflow integrating FEA with experimental validation.

Advanced Considerations and Best Practices

Pitfalls and Special Cases

- Geometric Singularities: In regions with re-entrant corners or zero-radius fillets, stress is theoretically infinite. Mesh refinement in these areas will cause stress to increase without bound. The solution is to model the actual, non-zero radius present in the physical part [12] [22].

- Locking Phenomena: Volumetric locking (in incompressible materials) and shear locking (in bending) can cause overly stiff behavior. Using second-order elements (p-refinement) is often an effective remedy [12].

Integration with Digital Workflows

Validated and converged FEA models can serve as the foundation for Digital Twins. As demonstrated in recent research, updated FEA results can be integrated into a Building Information Modeling (BIM) framework, enabling real-time visualization of structural performance and supporting condition assessment and maintenance planning [20].

The cantilever beam example provides a foundational analogy for understanding and executing mesh convergence studies. The rigorous, iterative protocol of model refinement, solution, and comparison against experimental data is essential for producing trustworthy simulation results. This practice is a critical component of the finite element method, transforming it from a simple design tool into a powerful, predictive technology that can reliably inform decision-making in scientific research and professional engineering.

A Step-by-Step Methodology for Performing Convergence Studies

In Finite Element Analysis (FEA), a Quantity of Interest (QoI) is a specific, numerically computed value that serves as a key indicator of a system's physical response under prescribed conditions. The careful selection of an appropriate QoI is fundamental to the reliability and relevance of any FEA study, particularly within the framework of mesh convergence. Mesh convergence studies evaluate how the numerical solution changes as the mesh is refined, and a model is considered converged when the results for the chosen QoI stabilize with progressively finer meshes [23]. This process ensures numerical accuracy and transforms simulation from an exercise in approximation into a tool for engineering certainty [23].

The selection process is not merely a technical step but a strategic one, dictated by the primary research or design question. Stresses are paramount in failure and yield analysis, displacements are critical in stiffness and deformation studies, and natural frequencies are essential for vibrational and dynamic response characterization. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers on the selection, calculation, and convergence verification of these primary quantities of interest.

Characteristics of Key Quantities of Interest

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and convergence considerations for the three primary categories of QoIs.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Quantities of Interest in FEA

| Quantity of Interest | Primary Physical Significance | Typical Applications | Convergence Behavior & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stresses (e.g., Von Mises) | Predicts yielding and failure in ductile materials [24]. | Structural integrity analysis of implants [3], biomechanics of bone [24] [25], and component design. | Generally slower to converge than displacements. Requires finer meshes, especially near stress concentrations. Sensitive to mesh quality and boundary conditions [23]. |

| Displacements | Measures deformation and structural stiffness. | Analysis of structural deformations [25], gap and interference checks, and fixation device displacement under load [3]. | Typically the fastest converging variable. Often used as a primary convergence criterion as it is less sensitive than stress [23]. |

| Natural Frequencies | Defines inherent dynamic characteristics and resonance modes. | Vibration analysis, seismic studies, and dynamic load design. | Convergence is assessed by tracking frequency values (Hz) across mesh refinements. Ensures the model captures the correct global and local dynamic stiffness. |

Protocols for Mesh Convergence Studies

General Workflow for a Convergence Study

A robust mesh convergence study follows a systematic procedure to validate the FEA model. The workflow below outlines the key steps, from initial mesh generation to the final decision on mesh adequacy.

Protocol 1: Convergence for Stress Analysis

Stress analysis, particularly with the Von Mises stress, is common in biomechanical and engineering applications but presents specific challenges for convergence.

- Objective: To obtain a mesh-independent stress distribution for accurate failure prediction.

- Materials & Software: FEA Pre-processor (for meshing), FEA Solver (e.g., Abaqus, ANSYS, open-source alternatives like OpenSees [1]), Post-processor, and a tool for statistical analysis of stress data.

- Procedure:

- Mesh Generation: Begin with a coarse mesh. Subsequent refinements should focus on regions of high stress gradients, such as geometric discontinuities, holes, and load application points. Both uniform and adaptive (non-uniform) meshes can be used, with the latter being more efficient for complex geometries [24].

- Simulation Execution: Run the simulation for each mesh refinement level and extract the stress field.

- Data Processing - Handling Non-Uniform Meshes: For meaningful comparison across different non-uniform meshes, use statistics that account for element size.

- The Mesh-Weighted Arithmetic Mean (MWAM) is the recommended central tendency statistic for a global stress value. It is calculated by summing the product of the stress in each element and its area (or volume), then dividing by the total area (or volume) [24]:

MWAM = Σ(σ_i * A_i) / Σ(A_i)whereσ_iis the stress in elementiandA_iis its area. - This prevents skewing of results, as larger elements appropriately contribute more to the global stress value than smaller ones [24].

- The Mesh-Weighted Arithmetic Mean (MWAM) is the recommended central tendency statistic for a global stress value. It is calculated by summing the product of the stress in each element and its area (or volume), then dividing by the total area (or volume) [24]:

- Convergence Check: Plot the MWAM of stress (or the maximum stress in a critical region) against mesh density (e.g., number of degrees of freedom). Convergence is achieved when the change in this value between subsequent refinements falls below a predetermined threshold (e.g., 2-5%).

Protocol 2: Convergence for Displacement Analysis

Displacement analysis is often more straightforward, as displacements converge faster than stresses.

- Objective: To ensure that the calculated deformations and stiffness of the system are mesh-independent.

- Materials & Software: FEA Pre-processor, FEA Solver, Post-processor.

- Procedure:

- Mesh Generation: Systematically refine the mesh globally. As displacements are a global response, local refinement is less critical than in stress analysis.

- Simulation Execution: Run the simulation for each mesh refinement level.

- Data Processing: Extract the maximum displacement in the model or the displacement at specific critical points (e.g., the tip of a cantilever, the center of a plate) [3].

- Convergence Check: Plot the selected displacement value against mesh density. The solution is considered converged once the displacement value plateaus with further refinement [23].

The Researcher's Toolkit for FEA Convergence

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for FEA Convergence Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in Convergence Studies |

|---|---|

| FEA Software with Meshing Tools | Provides the computational environment for generating meshes, solving the underlying differential equations, and extracting results. Essential for performing the systematic refinements required for convergence testing [1]. |

| Automated Meshing Scripts | Custom or built-in scripts that allow for batch generation of meshes with varying levels of refinement. Critical for ensuring systematic and consistent changes between mesh iterations, especially in complex geometries [26]. |

| Statistical Analysis Package | Software (e.g., Python with Pandas/NumPy, R) used to compute mesh-weighted statistics like the MWAM, which are crucial for accurately comparing stress results from non-uniform meshes [24]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Clusters or workstations with significant memory and processing power. Convergence studies require multiple simulation runs, which can be computationally expensive, making HPC resources highly valuable [1]. |

| Quasi-Ideal Mesh | A conceptual or practical mesh template that defines the target level of homogeneity and refinement. It serves as a benchmark to ensure different models are compared on a consistent basis, accounting for differences in element size [24]. |

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Despite a structured protocol, convergence can be elusive. Several advanced factors must be considered. Non-converging results may signal underlying issues beyond mere mesh density, including poor element quality, incorrect boundary conditions, or unaccounted-for nonlinear effects [23]. Furthermore, the simplifications inherent in material modeling—such as assuming uniform bone properties—can create a significant gap between a converged simulation and physical reality, limiting predictive accuracy [3] [25]. For dynamic problems, the QoI shifts to natural frequencies and mode shapes. Convergence must be verified for the frequencies of interest, ensuring the model correctly captures the inertial and stiffness properties that govern dynamic response.

The diagram above illustrates that the path to a converged result is not solely dependent on mesh density. The selected QoI is intrinsically linked to and influenced by solver algorithms (e.g., direct vs. iterative), the geometric construction and quality of the mesh, and the fidelity of the assigned material properties. A successful convergence study must therefore holistically address all these factors.

In Finite Element Analysis (FEA), achieving accurate and reliable results is paramount for researchers and engineers. The principle of mesh convergence states that as a computational mesh is refined, the numerical solution should approach the true physical solution of the underlying partial differential equations [12]. Two principal methodologies have emerged for systematic mesh refinement: h-refinement and p-refinement. The strategic selection between these approaches directly impacts computational efficiency, resource allocation, and result accuracy across diverse applications from structural mechanics to biomedical engineering [27] [28]. For researchers in drug development and biomedical fields, where modeling may involve complex biological structures or fluid-structure interactions, understanding these refinement strategies is essential for constructing valid computational models that predict real-world behavior without excessive computational cost.

Theoretical Foundations of Refinement Methods

H-Refinement Methodology

H-refinement is a mesh improvement technique that enhances solution accuracy by systematically reducing element sizes in critical regions while maintaining constant polynomial order of the shape functions [29]. This method increases the number of elements (and consequently degrees of freedom) in the computational domain, particularly targeting areas where error estimators indicate significant discretization errors [27]. The fundamental premise of h-refinement is that smaller elements can better capture high solution gradients and complex geometric features, leading to a more accurate representation of the physical phenomena being studied. The process is typically iterative, with each adaptation cycle identifying regions requiring finer discretization based on error assessment, subdividing elements in those regions, and resolving the system until satisfactory convergence is achieved [27].

P-Refinement Methodology

In contrast to h-refinement, p-refinement enhances solution accuracy by increasing the polynomial order (p) of the element shape functions while maintaining a fixed mesh topology [28] [29]. This approach elevates the mathematical sophistication of the solution approximation within each element rather than increasing element count. For sufficiently smooth solutions, p-refinement offers exponential error reduction as the polynomial order increases, whereas h-refinement typically provides only algebraic error reduction [28]. This makes p-refinement particularly effective for problems with smooth solutions where high-order approximations can dramatically accelerate convergence. The p-method essentially enriches the approximation space by employing higher-order polynomials, allowing more complex solution variations to be captured within each element without altering the computational grid.

The R-Refinement Alternative

A less common third approach, r-refinement, involves redistributing existing nodes within the domain to minimize potential energy without changing the total number of elements or their polynomial order [29]. This method relocates nodes toward regions where higher solution resolution is needed, effectively optimizing the mesh topology for a fixed number of degrees of freedom. While theoretically interesting, r-refinement remains less widely implemented in commercial FEA software and is considered obsolete for most practical applications [29].

Comparative Analysis: H-Refinement vs. P-Refinement

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of H- and P-Refinement

| Characteristic | H-Refinement | P-Refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Decreases element size | Increases polynomial order |

| Mesh Topology | Changes with refinement | Remains constant |

| Error Reduction Rate | Algebraic convergence | Exponential convergence for smooth solutions |

| Computational Cost | Increases degrees of freedom significantly | Increases degrees of freedom moderately |

| Implementation Complexity | Requires handling of hanging nodes | Avoids hanging nodes |

| Geometric Adaptation | Excellent for capturing complex geometries | Limited by initial mesh geometry |

| Solution Smoothness Requirement | Effective for non-smooth solutions | Requires smooth solutions for optimal performance |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Practical Applications

| Application Domain | H-Refinement Effectiveness | P-Refinement Effectiveness | Key Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind Turbine Wake Simulation [28] | High (resolves fine wake details) | High (exponential error reduction for smooth flows) | P-refinement potential for 60,000x DOF reduction for same precision |

| Brain Stimulation Modeling [27] | Critical for accuracy | Not implemented in study | <25% element increase exposed >60% errors in unrefined models |

| Metal Forming Analysis [30] | Computationally efficient | Not specified | Comparison carried out to evaluate computational efficiency |

| Structural Analysis [12] | Effective for stress concentrations | Superior for incompressible materials | Second-order elements preferred for incompressibility |

Key Advantages and Limitations

H-refinement demonstrates particular strength in handling problems with complex geometries, discontinuities, or singularities where the solution lacks smoothness [12]. By concentrating smaller elements in regions of interest, it can effectively capture localized phenomena such as stress concentrations around geometric features. However, this approach significantly increases the total number of degrees of freedom, leading to greater computational resource requirements for both processing and data storage [9]. The introduction of "hanging nodes" at interfaces between refined and unrefined regions adds implementation complexity that must be properly managed through constraint equations or special transition elements.

P-refinement excels in scenarios with smooth solutions where increasing the polynomial order delivers rapid convergence without altering mesh connectivity [28]. This method avoids hanging nodes and can achieve high accuracy with relatively few elements, making it computationally efficient for appropriate problems. However, its effectiveness diminishes when solutions contain discontinuities or sharp gradients, and it offers limited ability to improve geometric representation beyond the initial mesh resolution [12]. Additionally, higher-order elements require more sophisticated integration schemes and can lead to ill-conditioned systems if not properly implemented.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for H-Refinement Study

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate solution convergence through systematic element size reduction in regions of high discretization error.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- FEA software with adaptive meshing capabilities (e.g., Ansys Mechanical 2025R1 [13] or BEM-FMM [27])

- Error estimation algorithms (e.g., based on stress gradients or residual methods)

- Model of the physical system to be analyzed

Methodology:

- Initial Analysis: Perform FEA simulation with a baseline mesh configuration

- Error Assessment: Calculate error distribution across the domain using appropriate error estimators

- Element Selection: Identify elements exceeding predefined error thresholds for refinement

- Mesh Adaptation: Subdivide selected elements while maintaining mesh compatibility

- Iterative Solution: Repeat analysis with refined mesh until convergence criteria satisfied

- Result Verification: Compare key parameters (stresses, displacements, potentials) across refinement cycles

In brain stimulation modeling, researchers implementing this protocol discovered that increasing mesh elements by less than 25% in critical regions exposed electric field errors exceeding 60% in unrefined models [27]. This demonstrates the critical importance of targeted refinement in computational models for biomedical applications.

Protocol for P-Refinement Study

Objective: To assess convergence behavior through elevation of element polynomial order while maintaining fixed mesh topology.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- High-order FEA solver (e.g., Horses3D [28] or p-version FEA software)

- Mesh generation software capable of supporting higher-order elements

- Appropriate quadrature rules for numerical integration

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Solve problem using linear (p=1) or quadratic (p=2) elements

- Polynomial Enhancement: Systematically increase approximation order across the domain or in selected regions

- Solution Tracking: Monitor convergence of quantities of interest with increasing p-levels

- Condition Monitoring: Observe system conditioning and address potential numerical issues

- Convergence Assessment: Determine when further polynomial increase provides diminishing returns

In wind turbine wake simulations, this approach has demonstrated potential for dramatic reductions in degrees of freedom – up to 60,000 times reduction compared to low-order methods for equivalent precision [28].

Convergence Assessment Protocol

Objective: To establish quantitative criteria for determining when a solution has sufficiently converged.

Methodology:

- Parameter Selection: Identify critical response quantities (displacements, stresses, potentials, etc.)

- Progressive Refinement: Execute multiple analysis cycles with either h- or p-refinement

- Change Monitoring: Track variation in key parameters between refinement cycles

- Convergence Criteria: Establish threshold for acceptable change (typically 1-5% depending on application)

- Termination Decision: Conclude refinement when changes fall below established thresholds

As demonstrated in cantilever beam studies, convergence can be determined when stress variations between refinement cycles reduce to approximately 0.9% [9]. For less critical applications, variations up to 5% may be acceptable depending on computational constraints and engineering requirements.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Refinement Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| BEM-FMM Solver [27] | Boundary Element Method with Fast Multipole Acceleration | Electromagnetic modeling for brain stimulation |

| Horses3D [28] | High-order discontinuous Galerkin solver | Wind turbine wake simulation and fluid dynamics |

| Ansys Mechanical [13] | Commercial FEA with adaptive meshing | Structural analysis with automatic refinement |

| Error Estimators | Identify regions requiring refinement | Guide adaptive processes in both h- and p-methods |

| Fast Multipole Method | Accelerates boundary element calculations | Enables higher resolution models in BEM-FMM |

Application-Specific Implementation Guidelines

Biomedical Engineering Applications

In computational models of brain stimulation (TES, TMS) and electrophysiology (EEG), adaptive h-refinement has proven essential for accuracy. Studies using Boundary Element Method with Fast Multipole Acceleration (BEM-FMM) have demonstrated that strategically increasing mesh elements by less than 25% in critical regions can expose electric field errors exceeding 60% in unrefined models [27]. This has profound implications for TES dosing prediction and EEG lead field calculations, where accurate electric field strength is crucial. For these applications, implementing an automated adaptive refinement algorithm that efficiently allocates additional unknowns to critical areas significantly improves solution accuracy without prohibitive computational cost.

Fluid Dynamics and Wind Energy

For wind turbine wake simulation, both h- and p-refinement strategies offer distinct advantages. Research indicates that p-refinement provides exponential error reduction for sufficiently smooth flows, potentially reducing degrees of freedom by orders of magnitude compared to traditional low-order methods [28]. In one study, researchers projected that a low-order mesh with 100 million degrees of freedom could be replaced by a high-order mesh with just 1.6 thousand degrees of freedom for equivalent precision – a 60,000-fold reduction [28]. This dramatic efficiency gain makes p-refinement particularly attractive for large-scale fluid dynamics simulations where computational resources constrain model fidelity.

Structural Mechanics