Probabilistic Model Verification and Validation: A Foundational Framework for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to probabilistic model verification and validation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Probabilistic Model Verification and Validation: A Foundational Framework for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to probabilistic model verification and validation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of probabilistic modeling and its critical role in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD). The scope covers a range of methodologies, from quantitative systems pharmacology to AI-driven approaches, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. It further details rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses, synthesizing key takeaways to enhance model reliability, streamline regulatory approval, and accelerate the delivery of new therapies.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Probabilistic Modeling in Drug Development

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is an essential framework for advancing drug development and supporting regulatory decision-making by providing quantitative predictions and data-driven insights [1]. Probabilistic models form the backbone of this approach, enabling researchers to quantify uncertainty, variability, and confidence in predictions throughout the drug development lifecycle. These models range from relatively simple quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to highly complex quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) frameworks, all sharing the common goal of informing critical development decisions with mathematical rigor [1] [2]. The fundamental power of MIDD lies in its ability to maximize information from gathered data, build confidence in drug targets and endpoints, and allow for extrapolation to new clinical situations without requiring additional costly studies [2].

The adoption of these probabilistic approaches has transformed modern drug development from a largely empirical process to a more predictive and efficient science. By systematically accounting for variability and uncertainty, these models help accelerate hypothesis testing, assess potential drug candidates more efficiently, reduce costly late-stage failures, and ultimately accelerate market access for patients [1]. Global regulatory agencies now expect drug developers to apply these tools throughout a product's lifecycle where feasible to support key questions for decision-making and validate assumptions to minimize risk [2]. The evolution of these methodologies has been so significant that they have transitioned from "nice to have" components to "regulatory essentials" in late-stage clinical drug development programs [2].

Spectrum of Models in MIDD

The MIDD framework encompasses a diverse set of probabilistic modeling approaches, each with distinct applications, mathematical foundations, and positions along the spectrum from empirical to mechanistic methodologies. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of these key approaches, highlighting their primary applications, probabilistic elements, and regulatory use cases.

Table 1: Key Probabilistic Modeling Approaches in MIDD

| Model Type | Primary Application | Probabilistic Elements | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR [1] | Predict biological activity from chemical structure | Confidence intervals on predictions, uncertainty in descriptor contributions | Regression models, machine learning classifiers |

| PBPK [1] [2] | Predict drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) | Inter-individual variability in physiological parameters, uncertainty in system parameters | Virtual population simulations, drug-drug interaction prediction |

| Population PK/PD [1] [2] | Characterize drug exposure and response variability | Random effects for inter- and intra-individual variability, parameter uncertainty | Non-linear mixed effects modeling, covariate analysis |

| QSP [1] [2] | Simulate drug effects on disease pathways | Uncertainty in system parameters, variability in pathway interactions | Virtual patient simulations, disease progression modeling |

| Exposure-Response [1] | Quantify relationship between drug exposure and efficacy/safety | Confidence bands on response curves, prediction intervals | Logistic regression, time-to-event models |

| MBMA [2] | Indirect comparison of treatments across studies | Uncertainty in treatment effect estimates, between-study variability | Hierarchical Bayesian models, meta-regression |

Model Selection Framework

Selecting the appropriate probabilistic model requires careful consideration of the development stage, available data, and specific questions of interest. The "fit-for-purpose" principle dictates that models must be closely aligned with the question of interest (QOI), context of use (COU), and required level of model evaluation [1]. A model is not considered fit-for-purpose when it fails to define the COU, lacks appropriate data quality and quantity, or incorporates unjustified complexities or oversimplifications [1].

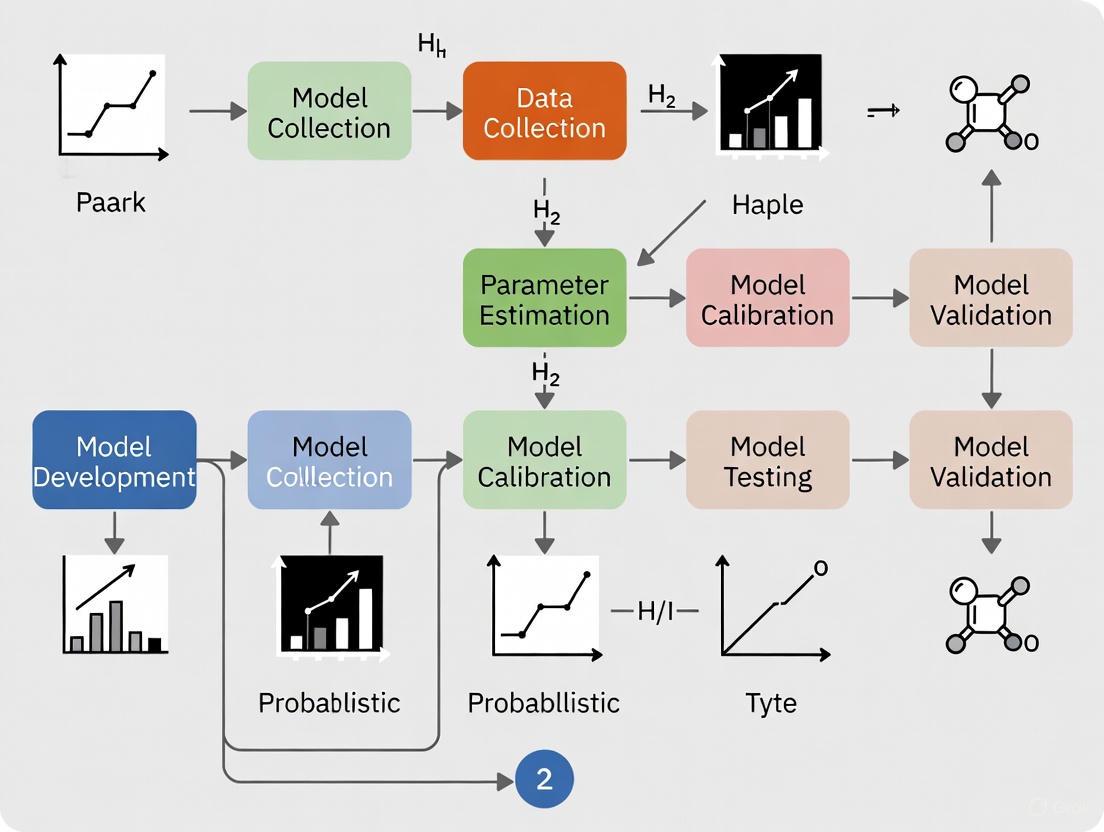

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting and applying probabilistic models within the MIDD framework:

Model Selection Workflow in MIDD

This structured approach ensures that model complexity is appropriately matched to the development stage and specific questions being addressed, while maintaining a focus on the regulatory context throughout the process.

Detailed Model Applications and Protocols

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR models are computational approaches that predict the biological activity of compounds based on their chemical structure [1]. These models establish probabilistic relationships between molecular descriptors (independent variables) and biological responses (dependent variables), allowing for predictive assessment of novel compounds without synthesis and testing.

Experimental Protocol 1: Development and Validation of a QSAR Model

- Objective: To develop a validated QSAR model for predicting compound activity against a specific biological target.

- Materials:

- Chemical Database: Curated set of compounds with known chemical structures and experimental activity values (e.g., IC50, Ki).

- Descriptor Calculation Software: Tools like RDKit, PaDEL, or Dragon for computing molecular descriptors.

- Statistical Software: R, Python with scikit-learn, or specialized QSAR platforms.

- Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collect and curate a homogeneous dataset of compounds with reliable activity data. Apply stringent exclusion criteria for poor-quality measurements.

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, geometric) for all compounds in the dataset.

- Descriptor Selection: Apply feature selection techniques (e.g., genetic algorithms, stepwise selection) to reduce dimensionality and avoid overfitting.

- Model Training: Split data into training (≈70-80%) and test (≈20-30%) sets. Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., partial least squares, random forest, support vector machines) to training data.

- Internal Validation: Assess model performance on training set using cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold) and calculate metrics including Q², R², and root mean square error (RMSE).

- External Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set to estimate predictive performance on new compounds.

- Applicability Domain: Define the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions using approaches such as leverage or distance-based methods.

- Quality Assurance: Ensure compliance with OECD principles for QSAR validation, including defined endpoint, unambiguous algorithm, appropriate validation, and applicability domain [3].

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK modeling is a mechanistic approach that simulates how a drug moves through and is processed by different organs and tissues in the body based on physiological, biochemical, and drug-specific properties [2]. These models incorporate probabilistic elements through virtual population simulations that account for inter-individual variability in physiological parameters.

Experimental Protocol 2: PBPK Model Development for Special Populations

- Objective: To develop a PBPK model for predicting drug exposure in unstudied special populations (e.g., pediatrics, hepatic impairment).

- Materials:

- PBPK Software Platform: Commercial (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) or open-source platforms.

- System Data: Population demographic, physiological, and genetic data for target populations.

- Drug-Specific Parameters: In vitro and in vivo data on drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion.

- Procedure:

- Model Development: Develop and validate a base PBPK model using healthy adult data, incorporating drug-specific parameters (e.g., solubility, permeability, metabolic clearance).

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify critical system parameters that most influence drug exposure using local or global sensitivity analysis.

- Virtual Population: Generate virtual populations representing the target special population by modifying relevant physiological parameters (e.g., organ sizes, blood flows, enzyme expression).

- Simulation: Execute multiple trials (n=100-1000) with different virtual subjects to predict population pharmacokinetics and account for variability.

- Model Verification: Compare simulation results with any available observed data in the special population, if available.

- Dosing Recommendation: Simulate different dosing regimens to identify optimal dosing for the special population.

- Regulatory Considerations: PBPK models are frequently used to support waivers for clinical studies in special populations and to predict drug-drug interactions [2].

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Modeling

QSP represents the most integrative probabilistic modeling approach, combining computational modeling and experimental data to examine the relationships between a drug, the biological system, and the underlying disease process [4] [2]. These models typically incorporate multiple probabilistic elements, including uncertainty in system parameters and variability in pathway interactions.

Experimental Protocol 3: QSP Model for Combination Therapy Optimization

- Objective: To develop a QSP model for identifying optimal drug combinations in oncology.

- Materials:

- Pathway Data: Literature-curated information on disease-relevant biological pathways.

- Drug Properties: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters for individual drugs.

- QSP Platform: Specialized software for complex systems modeling.

- Procedure:

- Network Construction: Map key biological pathways and interactions relevant to the disease and drug mechanisms.

- Mathematical Representation: Translate biological network into ordinary differential equations or agent-based models.

- Parameter Estimation: Calibrate model parameters using available preclinical and clinical data, quantifying uncertainty through Bayesian inference or profile likelihood approaches.

- Virtual Patient Generation: Create populations of virtual patients with variability in key biological parameters to represent heterogeneous patient populations.

- Intervention Testing: Simulate monotherapies and combination therapies across the virtual population to identify synergistic effects.

- Biomarker Identification: Simulate potential biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment response prediction.

- Application: QSP is particularly valuable for new modalities, dose selection, combination therapy optimization, and target selection [2].

Probabilistic Aspects and Validation Framework

Quantifying Uncertainty and Variability

A fundamental strength of probabilistic models in MIDD is their explicit handling of two distinct types of randomness: uncertainty and variability. Uncertainty represents limited knowledge about model parameters that could theoretically be reduced with more data, while variability reflects true heterogeneity in populations that cannot be reduced with additional sampling [3].

Table 2 outlines common probabilistic elements and validation approaches across MIDD methodologies:

Table 2: Probabilistic Elements and Validation in MIDD Models

| Model Type | Sources of Uncertainty | Sources of Variability | Validation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR [1] [3] | Descriptor selection, model structure, activity measurement error | Chemical space diversity, assay variability | External validation, y-randomization, applicability domain assessment |

| PBPK [2] | System parameters, drug-specific parameters, system structure | Physiological differences, enzyme expression, demographics | Prospective prediction vs. observed data, drug-drug interaction verification |

| Population PK/PD [1] [2] | Structural model, parameter estimates, residual error model | Between-subject variability, between-occasion variability | Visual predictive checks, bootstrap analysis, normalized prediction distribution errors |

| QSP [4] [2] | Pathway topology, system parameters, connection strengths | Biological pathway expression, disease heterogeneity | Multilevel validation (molecular, cellular, clinical), prospective prediction |

Model Verification and Validation (V&V) Protocol

Robust validation is essential for establishing confidence in probabilistic models and ensuring their appropriate use in regulatory decision-making. The following protocol provides a general framework for model V&V:

Experimental Protocol 4: Comprehensive Model Verification and Validation

- Objective: To establish a comprehensive V&V framework for probabilistic models in MIDD.

- Procedure:

- Verification:

- Confirm correct implementation of mathematical equations and algorithms.

- Perform unit testing of individual model components.

- Verify numerical accuracy and stability across expected operating ranges.

- Internal Validation:

- Assess model fit to the data used for model development.

- Perform cross-validation (e.g., k-fold, leave-one-out) to evaluate overfitting.

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to identify influential parameters and assumptions.

- External Validation:

- Evaluate model performance against data not used in model development.

- Compare predictions with prospective experimental or clinical results.

- Assess predictive performance using appropriate metrics (e.g., mean absolute error, prediction intervals).

- Predictive Check:

- Generate posterior predictive distributions for key endpoints.

- Compare simulated outcomes with observed data using visual predictive checks.

- Quantify calibration using statistical measures (e.g., prediction-corrected visual predictive checks).

- Verification:

- Documentation: Maintain comprehensive documentation of all model assumptions, data sources, software tools, and validation results to support regulatory submissions [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of probabilistic models in MIDD requires both computational tools and well-characterized data resources. The following table details key components of the MIDD research toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Probabilistic Modeling in MIDD

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation Platforms [1] [2] | NONMEM, Monolix, Simcyp, GastroPlus, R, Python | Implement and execute probabilistic models | Population modeling, PBPK simulation, statistical analysis, machine learning |

| Data Curation Resources [3] [2] | Clinical trial databases, literature compendia, in-house assay data | Provide input data for model development and validation | Highly curated clinical data, standardized assay results, quality-controlled datasets |

| Model Validation Tools [3] | R packages (e.g., xpose, Pirana), Python libraries | Perform model verification, validation, and diagnostic testing | Visual predictive checks, bootstrap analysis, sensitivity analysis |

| Visualization & Reporting [3] | R Shiny, Spotfire, Jupyter Notebooks | Communicate model results and insights to stakeholders | Interactive dashboards, reproducible reports, publication-quality graphics |

Regulatory Context and Future Directions

The regulatory landscape for MIDD approaches has evolved significantly, with global regulatory agencies now encouraging the integration of these approaches into drug submissions [2]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has developed the M15 guideline to establish global best practices for planning, evaluating, and documenting models in regulatory submissions [4]. This standardization promises to improve consistency among global sponsors in applying MIDD in drug development and regulatory interactions [1].

The FDA's Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND) pilot program represents another significant regulatory advancement, designed to qualify novel drug development tools—including M&S and AI-based methods—as regulatory methodologies [4]. These developments, coupled with the FDA's commitment to reducing animal testing through alternatives like MIDD, highlight the growing importance of probabilistic modeling in regulatory science [2].

Looking forward, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with traditional MIDD approaches promises to further enhance their predictive power and efficiency [1] [4]. As these technologies mature, probabilistic models will likely play an increasingly central role in accelerating the development of safer, more effective therapies while reducing costs and animal testing throughout the drug development lifecycle.

The Critical Role of Verification and Validation in Regulatory Success

Verification and validation (V&V) are independent procedures used together to ensure that a product, service, or system meets specified requirements and fulfills its intended purpose [5]. These processes serve as critical components of a quality management system and are fundamental to regulatory success in highly regulated industries such as medical devices and pharmaceuticals. While sometimes used interchangeably, these terms have distinct definitions according to standards adopted by leading organizations [5]. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) defines validation as "the assurance that a product, service, or system meets the needs of the customer and other identified stakeholders," while verification is "the evaluation of whether or not a product, service, or system complies with a regulation, requirement, specification, or imposed condition" [5]. Similarly, the FDA provides specific definitions for medical devices, stating that validation ensures the device meets user needs and requirements, while verification ensures it meets specified design requirements [5].

A commonly expressed distinction is that validation answers "Are you building the right thing?" while verification answers "Are you building it right?" [5]. This distinction is crucial in regulatory contexts, where a product might pass verification (meeting all specifications) but fail validation (not addressing user needs adequately) if specifications themselves are flawed [5]. For computational models used in regulatory submissions, the ASME V&V 40-2018 standard provides a risk-informed credibility assessment framework that integrates both processes [6].

Theoretical Framework: A Probabilistic Approach to V&V

The probabilistic approach to verification and validation represents a paradigm shift from deterministic checklists to risk-informed, quantitative assessments of model credibility. This approach acknowledges the inherent uncertainties in computational models and provides a framework for quantifying confidence in model predictions, which is particularly valuable for regulatory decision-making [6].

Foundational Concepts

In probabilistic V&V, the traditional binary pass/fail outcome is replaced with a credibility assessment that evaluates the degree of confidence in the model's predictions for a specific Context of Use (COU). The ASME V&V 40 standard establishes a risk-informed process that begins with identifying the question of interest, which describes the specific question, decision, or concern being addressed with a computational model [6]. The COU then establishes the specific role and scope of the model in addressing this question, detailing how model outputs will inform the decision alongside other evidence sources [6].

Risk-Informed Credibility Assessment

The probabilistic framework introduces model risk as a combination of model influence (the contribution of the computational model to the decision relative to other evidence) and decision consequence (the impact of an incorrect decision based on the model) [6]. This risk analysis directly informs the rigor required in V&V activities, with higher-risk applications necessitating more extensive evidence of model credibility [6].

Table: Risk Matrix for Credibility Assessment Planning

| Low Decision Consequence | Medium Decision Consequence | High Decision Consequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Influence | Minimal V&V Rigor | Moderate V&V Rigor | Substantial V&V Rigor |

| Medium Influence | Moderate V&V Rigor | Substantial V&V Rigor | Extensive V&V Rigor |

| High Influence | Substantial V&V Rigor | Extensive V&V Rigor | Extensive V&V Rigor |

Application Notes: V&V in Regulatory Contexts

Regulatory Landscape for In Silico Evidence

Regulatory agencies increasingly accept evidence produced in silico (through modeling and simulation) to support marketing authorization requests for medical products [6]. The FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) published guidance on "Reporting of Computational Modeling Studies in Medical Device Submissions" in 2016, followed by the ASME V&V 40-2018 standard in 2018 [6]. Similarly, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has published guidelines on physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, sharing key features with the ASME standard [6].

The Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) initiative represents a significant advancement in regulatory science, proposing modeling and simulation of human ventricular electrophysiology for safety assessment of new pharmaceutical compounds [6]. This initiative, sponsored by FDA, the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium, and the Health and Environmental Science Institute, exemplifies the growing regulatory acceptance of in silico methods when supported by rigorous V&V.

V&V Activities and Methodologies

Verification and validation encompass distinct but complementary activities throughout the development lifecycle:

Verification Activities involve checking that a product, service, or system meets a set of design specifications [5]. In development phases, verification procedures involve special tests to model or simulate portions of the system, followed by analysis of results [5]. In post-development phases, verification involves regularly repeating tests to ensure continued compliance with initial requirements [5]. For machinery and equipment, verification typically consists of:

- Design Qualification (DQ): Confirming through review and testing that equipment meets written acquisition specifications

- Installation Qualification (IQ): Verifying proper installation

- Operational Qualification (OQ): Ensuring operational performance meets specifications

- Performance Qualification (PQ): Demonstrating consistent performance under routine operations [5]

Validation Activities ensure that products, services, or systems meet the operational needs of the user [5]. Validation can be categorized by:

- Prospective validation: Conducted before new items are released

- Retrospective validation: For items already in use, based on historical data

- Partial validation: For research and pilot studies with time constraints

- Re-validation: Conducted after changes, relocation, or specified time periods [5]

Table: Analytical Method Validation Attributes

| Attribute | Description | Application in Probabilistic Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy and Precision | Closeness to true value and repeatability | Quantified through uncertainty distributions |

| Sensitivity and Specificity | Ability to detect true positives and negatives | Incorporated into model reliability estimates |

| Limit of Detection/Quantification | Lowest detectable/quantifiable amount | Modeled as probability distributions |

| Repeatability/Reproducibility | Consistency under same/different conditions | Source of uncertainty in model predictions |

| Linearity and Range | Proportionality and operating range | Defined with confidence intervals |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Model Verification Process

Objective: To ensure computational models are implemented correctly and operate as intended.

Materials and Methods:

- Software Tools: Event-B formal modeling tool, Rodin platform, static code analysis tools [7]

- Input Data: Model specifications, design documents, algorithm descriptions

- Verification Techniques:

- Requirement Reviews: Evaluate requirement documents for completeness, clarity, and testability [8]

- Design Reviews: Systematically examine software design artifacts for logical correctness and alignment with requirements [8]

- Code Reviews: Peer review source code to identify defects and enforce standards [8]

- Static Code Analysis: Use automated tools to analyze source code without execution [8]

- Unit Testing: Execute test cases for individual units or functions [8]

- Formal Verification: Use mathematical proof methods, such as those implemented in Event-B, to verify algorithm correctness [7]

Procedure:

- Analyze model requirements to ensure they are clear, complete, and testable

- Plan verification activities, including techniques, responsible personnel, and timeline

- Prepare verification artifacts (requirement specifications, design documents, source code)

- Execute planned verification activities

- Document all findings, including defects and inconsistencies

- Resolve identified issues through development team collaboration

- Perform re-verification to confirm effective corrections

- Compile verification summary report for stakeholder approval [8]

Protocol 2: Model Validation Process

Objective: To ensure computational models meet stakeholder needs and function as intended in real-world scenarios.

Materials and Methods:

- Validation Environment: Realistic test environment mirroring production conditions [8]

- Reference Data: Experimental data, clinical data, historical performance data [6]

- Validation Techniques:

- Functional Testing: Validate software functions against specified requirements [8]

- Integration Testing: Test interactions between integrated modules [8]

- System Testing: Perform end-to-end testing on fully integrated systems [8]

- User Acceptance Testing (UAT): End users verify software meets their needs [8]

- Performance Testing: Validate responsiveness, stability, and scalability [8]

- Uncertainty Quantification: Characterize and quantify uncertainties in model predictions [6]

Procedure:

- Analyze and validate business and functional requirements against end user needs

- Define validation test plan scope, objectives, and schedules

- Design test scenarios and cases simulating real-world usage

- Set up realistic test environment mirroring production conditions

- Execute validation test cases (functional, system, UAT, performance testing)

- Log and analyze defects, focusing on impact to context of use

- Evaluate model credibility through comparison of predictions with validation data

- Compile validation evidence report assessing suitability for regulatory submission [8] [6]

Protocol 3: Probabilistic Neural Network V&V for Load Balancing

Objective: To verify and validate an Effective Probabilistic Neural Network (EPNN) for load balancing in cloud environments using formal methods.

Materials and Methods:

- Modeling Framework: Effective Probabilistic Neural Network (EPNN) architecture [7]

- Verification Tool: Event-B formal modeling tool with Rodin platform [7]

- Algorithms: Round Robin Assigning Algorithm (RRAA), Data Discovery Algorithm (DDA) [7]

- Validation Metrics: Resource utilization, response time, system reliability [7]

Procedure:

- Formal Modeling: Develop formal model of EPNN algorithm in Event-B tool [7]

- Proof Obligation Generation: Use Rodin tool to construct proof obligations based on algorithm context [7]

- Automated Proof: Execute automated proof generation to verify algorithm correctness [7]

- Manual Proof Refinement: Manually correct events not properly associated with invariants or context [7]

- Model Validation: Validate EPNN performance against load balancing metrics (resource utilization, response time) [7]

- Uncertainty Quantification: Characterize probabilistic uncertainties in neural network predictions [7]

- Credibility Assessment: Evaluate model credibility for specific cloud computing contexts of use [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Model Verification and Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Event-B Formal Modeling Tool | Provides platform for formal specification and verification of systems | Algorithm correctness verification through mathematical proof [7] |

| Rodin Platform | Open-source toolset for Event-B with automated proof support | Generation of proof obligations and automated proof techniques [7] |

| Static Code Analysis Tools | Analyze source code for defects without execution | Early detection of coding errors and standards compliance [8] |

| Uncertainty Quantification Framework | Characterize and quantify uncertainties in model predictions | Probabilistic assessment of model reliability [6] |

| Traceability Matrix | Verify requirement coverage throughout development | Ensure all requirements have corresponding test coverage [8] |

| Validation Test Environment | Mirror production conditions for realistic testing | System validation under actual operating conditions [8] |

Verification and validation play a critical role in regulatory success by providing evidence of product safety and efficacy. The probabilistic approach to V&V represents an advanced methodology that quantifies model credibility through risk-informed assessment frameworks. By implementing rigorous V&V protocols aligned with regulatory standards such as ASME V&V 40, researchers and product developers can generate compelling evidence for regulatory submissions while ensuring their products reliably meet user needs. The integration of formal verification methods, comprehensive validation testing, and uncertainty quantification provides a robust foundation for regulatory approval in increasingly complex technological landscapes.

In modern drug development and clinical research, the "fit-for-purpose" approach provides a flexible yet rigorous framework for validating models and biomarker assays, ensuring they are appropriate for their specific intended use rather than holding them to universal, one-size-fits-all standards. This paradigm recognizes that the level of evidence and stringency required for validation depends on the model's role in decision-making and its context of use (COU) [9]. Within a broader research thesis on probabilistic approaches to model verification and validation, the fit-for-purpose principle becomes particularly powerful. It allows for the incorporation of uncertainty quantification and probabilistic reasoning, enabling researchers to build models that more accurately represent real-world biological variability and the inherent uncertainties in prediction.

The foundation of this approach lies in aligning the model's capabilities with the specific "Question of Interest" (QoI) it is designed to address. A model intended for early-stage hypothesis generation requires a different validation stringency than one used to support regulatory submissions for dose selection or patient stratification [10]. The context of use explicitly defines the role and scope of the model, the decisions it will inform, and the population and conditions in which it will be applied, forming the critical basis for all subsequent validation activities [11] [10].

The V3 Framework: Verification, Analytical Validation, and Clinical Validation

A comprehensive framework for establishing that a model or Biometric Monitoring Technology (BioMeT) is fit-for-purpose is the V3 framework, which consists of three foundational components: Verification, Analytical Validation, and Clinical Validation [11]. This framework adapts well-established engineering and clinical development practices to the specific challenges of digital medicine and computational modeling.

Verification is the process of confirming through objective evidence that the model's design outputs correctly implement the specified design inputs. In essence, it answers the question: "Did we build the model correctly according to specifications?" [11] [12]. This involves checking that the code is implemented correctly, the algorithms perform as intended in silico, and the computational components meet their predefined requirements.

Analytical Validation moves the evaluation from the bench to an in-vivo context, assessing the performance of the model's algorithms in translating input data into the intended physiological or clinical metrics. It occurs at the intersection of engineering and clinical expertise and is typically performed by the entity that created the algorithm [11]. For a probabilistic model, this would include validating the accuracy of its uncertainty estimates.

Clinical Validation demonstrates that the model acceptably identifies, measures, or predicts a relevant clinical, biological, or functional state within a specific context of use and a defined population [11]. It answers the critical question: "Did we build the right model for the intended clinical purpose?" [12]. This requires evidence that the model's outputs correlate meaningfully with clinical endpoints or realities.

The relationship and primary questions addressed by these components are summarized in the workflow below.

Quantitative Performance Standards for Method Validation

The specific performance parameters evaluated during validation are highly dependent on the type of model or assay being developed. The fit-for-purpose approach tailors the validation requirements to the assay's technology category and its position on the spectrum from research tool to clinical endpoint. The American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) has identified five general classes of biomarker assays, each with recommended performance parameters to investigate during validation [9].

Table 1: Recommended Performance Parameters by Assay Category

| Performance Characteristic | Definitive Quantitative | Relative Quantitative | Quasi-Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | + | |||

| Trueness (Bias) | + | + | ||

| Precision | + | + | + | |

| Reproducibility | + | |||

| Sensitivity | + | + | + | + |

| Specificity | + | + | + | + |

| Dilution Linearity | + | + | ||

| Parallelism | + | + | ||

| Assay Range | + | + | + | |

| LLOQ/ULOQ | + (LLOQ-ULOQ) | + (LLOQ-ULOQ) |

For definitive quantitative methods (e.g., mass spectrometric analysis), accuracy is dependent on total error, which is the sum of systematic error (bias) and random error (intermediate precision) [9]. While bioanalysis of small molecules traditionally follows the "4-6-15 rule" (where 4 of 6 quality control samples must be within 15% of their nominal value), biomarker method validation often allows for more flexibility, with 25% being a common default value for precision and accuracy (30% at the Lower Limit of Quantitation) [9]. A more sophisticated approach involves constructing an "accuracy profile" which plots the β-expectation tolerance interval to visually display the confidence interval (e.g., 95%) for future measurements, allowing researchers to determine the probability that future results will fall within pre-defined acceptance limits [9].

Experimental Protocols for Fit-for-Purpose Validation

Protocol: Multi-Stage Validation for Biomarker Assays

This protocol outlines a phased approach for biomarker method validation, emphasizing iterative improvement and continuous assessment of fitness-for-purpose [9].

1. Purpose and Goal To establish a robust, phased methodology for the validation of biomarker assays, ensuring they are fit-for-purpose for their specific intended use in clinical trials or research.

2. Experimental Workflow The validation process proceeds through five discrete stages:

Stage 1: Definition and Selection

- Define the explicit purpose and Context of Use (COU) for the assay.

- Select the candidate assay based on the COU and the biological question.

- Output: A clearly articulated validation goal.

Stage 2: Planning and Assembly

- Assemble all necessary reagents, components, and data pipelines.

- Write a detailed method validation plan.

- Finalize the classification of the assay (e.g., definitive quantitative, qualitative).

- Output: A comprehensive validation protocol.

Stage 3: Experimental Performance Verification

- Execute the validation plan to characterize the assay's performance parameters (see Table 1).

- Critically evaluate fitness-for-purpose by comparing performance data against the pre-defined acceptance criteria from Stage 1.

- Output: A validation report and a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for routine use.

Stage 4: In-Study Validation

- Deploy the assay in a pilot or actual clinical study.

- Assess robustness in the clinical context and identify real-world issues (e.g., related to patient sample collection, storage, and stability).

- Output: An assessment of practical fitness-for-purpose.

Stage 5: Routine Use and Monitoring

- Implement the assay for its intended routine use.

- Establish ongoing Quality Control (QC) monitoring, proficiency testing, and procedures for handling batch-to-batch QC issues.

- Output: A system for continuous quality assurance and iterative improvement.

3. Key Considerations

- The driver of the process is continuous improvement, which may necessitate iterations that loop back to any earlier stage.

- For probabilistic models, each stage should include steps for evaluating uncertainty calibration, such as calculating metrics like the Expected Calibration Error (ECE) [13].

Protocol: Implementing a Probabilistic Phenotyping Model

This protocol details the methodology for building a probabilistic disease phenotype from Electronic Health Records (EHR) using the Label Estimation via Inference (LEVI) model, a Bayesian approach that does not require gold-standard labels [13].

1. Purpose and Goal To create a probabilistically calibrated disease phenotype from EHR data that outputs well-calibrated probabilities of diagnosis instead of binary classifications, enabling better risk-benefit tradeoffs in downstream applications.

2. Experimental Workflow

Step 1: Candidate Population Filtering

- Filter the EHR population down to disease-specific candidates using broad, inclusive criteria (e.g., presence of relevant diagnosis codes, medications, or terms in clinical notes).

- Goal: Increase disease prevalence in the candidate pool while minimizing the exclusion of true positive cases.

Step 2: Develop Labeling Functions (LFs)

- Iteratively develop a set of heuristic "labeling functions" – rules that vote on a patient's positive or negative status.

- LFs can apply to any data modality (e.g., "patient prescribed drug X," "disease Y mentioned in a numbered list").

- Validate LFs through spot-checking accuracy and clinician consultation.

Step 3: Aggregate Votes Using LEVI Model

- Apply the LEVI model, which computes the posterior probability of a positive diagnosis using a closed-form Bayesian solution. The model leverages:

α_ρ,β_ρ: Priors for disease prevalence.α_TPR,β_TPR: Priors for the True Positive Rate of positive LFs.α_FPR,β_FPR: Priors for the False Positive Rate of positive LFs.

- The posterior label probability is derived as:

P(z_j=1 | V_j) = σ( log( (α_ρ + n_pos - 1)/(β_ρ + n_neg - 1) ) + Σ_i:V_ij=1 log( (α_TPR + k_TP_i - 1)/(α_FPR + k_FP_i - 1) ) + Σ_i:V_ij=0 log( (β_FPR + N_i - k_FP_i - 1)/(β_TPR + N_i - k_TP_i - 1) ) )Whereσis the logistic function,V_jis the vote vector for patientj,n_pos/n_negare counts of positive/negative votes, andk_TP_i/k_FP_iare counts of true/false positives for LFiestimated from the data.

- Apply the LEVI model, which computes the posterior probability of a positive diagnosis using a closed-form Bayesian solution. The model leverages:

Step 4: Prior Selection via Maximum Entropy

- Encode prior knowledge about prevalence and LF performance using the principle of Maximum Entropy, making the prior distribution as non-committal as possible given known constraints (e.g., an "upper bound" on a variable's plausible value).

3. Key Considerations

- This method is particularly valuable in EHR data, which often suffers from incompleteness, leading to ambiguous or contradictory evidence for a diagnosis.

- The output is a well-calibrated probability, which allows for more nuanced decision-making based on the specific costs of false positives and false negatives in a given application [13].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of this probabilistic phenotyping process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully implementing a fit-for-purpose validation strategy requires a suite of methodological tools and conceptual frameworks. The table below details key "research reagents" essential for this process.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Fit-for-Purpose Model Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Framework | Context of Use (COU) | Defines the specific role, scope, and decision-making context of the model, forming the foundation for all validation activities [10]. |

| Conceptual Framework | Question of Interest (QoI) | Articulates the precise scientific or clinical question the model is designed to address, ensuring alignment between the model and its application [10]. |

| Validation Framework | V3 (Verification, Analytical Validation, Clinical Validation) | Provides a structured, three-component framework for the foundational evaluation of models and BioMeTs [11]. |

| Statistical Tool | Accuracy Profile / β-Expectation Tolerance Interval | A visual tool for assessing the total error of a quantitative method, predicting the confidence interval for future measurements against pre-defined acceptance limits [9]. |

| Computational Model | Label Estimation via Inference (LEVI) | A Bayesian model for aggregating weak supervision signals to create probabilistically calibrated outputs without the need for gold-standard labels [13]. |

| Regulatory Document | Model Analysis Plan (MAP) | A pre-defined plan outlining the technical criteria, assumptions, and analysis pipeline for a model, serving as the foundation for regulatory alignment [10]. |

| Quality Control Tool | Traceability Matrix | A document that links requirements (e.g., user needs, design inputs) to corresponding verification and validation activities, ensuring comprehensive coverage [14]. |

Adopting a fit-for-purpose approach is fundamental to developing models that are not only scientifically sound but also clinically meaningful and resource-efficient. By rigorously aligning the model with a specific Question of Interest and Context of Use, and by employing structured frameworks like V3 and probabilistic methodologies like LEVI, researchers can generate the robust evidence base needed to support critical decisions in drug development and clinical practice. This paradigm, especially when integrated with probabilistic reasoning, ensures that models are deployed with a clear understanding of their capabilities, limitations, and inherent uncertainties, ultimately enhancing the reliability and impact of model-informed drug development.

In the rigorous framework of probabilistic model verification and validation, the drug development process represents a critical domain for applying structured uncertainty quantification. Transition probabilities—the quantitative metrics that define the likelihood a drug candidate moves from one clinical phase to the next—serve as fundamental parameters in state-transition models that predict research outcomes, resource allocation, and ultimate commercial viability [15]. These probabilities form the mathematical backbone of cost-effectiveness analyses and portfolio decision-making, translating complex, multi-stage clinical development pathways into computable risk metrics.

Understanding and accurately estimating these probabilities is essential for creating robust models that reflect the actual dynamics of drug development. This overview examines the methodologies for deriving these critical values from published evidence, explores disease-specific variations that challenge aggregate estimates, and provides structured protocols for their application in probabilistic research models, thereby contributing to more reliable verification and validation of developmental risk assessments.

Defining Transition Probabilities in Clinical Development

Transition probabilities are mathematically defined as the probability that a drug product moves from one defined clinical phase to the next during a specified time period, known as the cycle length [15]. In the context of a state-transition model for drug development, these probabilities quantify the risk of progression through sequential stages: typically from Phase I to Phase II, Phase II to Phase III, and Phase III to regulatory approval and launch.

These probabilities are cumulative, representing the compound likelihood of successfully overcoming all scientific, clinical, and regulatory hurdles within a phase. Decision modelers face two primary challenges: published data often comes in forms other than probabilities (e.g., rates, relative risks), and the time frames of published probabilities rarely match the cycle length required for a specific model [15].

The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR)–Society for Medical Decision Making (SMDM) Modeling Task Force recommends deriving transition probabilities from "the most representative data sources for the decision problem" [15]. The hierarchy of evidence sources includes:

- Population-based epidemiological studies are preferred for modeling the natural history of a condition.

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) provide the highest-quality evidence of efficacy for intervention arms, though generalizability to real-world settings can be limited.

- Network meta-analyses offer a robust methodology for comparing multiple interventions that have not been directly tested against each other in single RCTs, maintaining randomization within trials for unbiased relative treatment effects [15].

Table 1: Common Statistical Measures Used to Derive Transition Probabilities

| Statistic | Definition | Range | Use in Probability Derivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability/Risk | Number of events / Number of people followed | 0–1 | Direct input; may require cycle-length adjustment |

| Rate | Number of events / Total person-time experienced | 0 to ∞ | Converted to probability using survival formulas |

| Relative Risk (RR) | Probability in exposed / Probability in unexposed | 0 to ∞ | Adjusts baseline probabilities for subgroups or treatments |

| Odds | Probability / (1 - Probability) | 0 to ∞ | Intermediate step in calculations |

| Odds Ratio (OR) | Odds in exposed / Odds in unexposed | 0 to ∞ | Used to adjust probabilities via logistic models |

Disease-Specific Variations in Transition Probabilities

Aggregate transition probabilities at the therapeutic area level can mask significant variations at the individual disease level, a critical consideration for accurate model validation. Research analyzing eight specific diseases revealed that for five of them, success probabilities for individual diseases deviated meaningfully (by more than ten percentage points) from the broader neurological or autoimmune therapeutic area probabilities [16].

Table 2: Comparative Cumulative Phase Success Probabilities by Disease [16]

| Disease / Therapeutic Area | Phase I to II | Phase II to III | Phase III to Launch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurology (Therapeutic Area) | 62% | 19% | 9-15% |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | 75% | 27% | 4% |

| Autoimmune (Therapeutic Area) | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| Crohn's Disease | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area | Aligned closely with autoimmune area |

Key observations from this comparative analysis include:

- Neurological Disease Deviation: For Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), drugs showed a higher probability of success in early phases (Phase I to II and Phase II to III) compared to the neurological area overall. However, this advantage reversed dramatically in the final phase, where the probability of success from Phase III to launch (4%) was less than half that of the broader neurology area (9-15%) [16].

- Autoimmune Disease Consistency: In contrast, the three autoimmune disorders studied—Crohn's disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Multiple Sclerosis—followed nearly identical success probability trajectories that closely matched their overarching therapeutic area. This consistency occurred despite differences in the availability of efficacy biomarkers, suggesting that other factors beyond biomarker understanding influence phase transition success in this domain [16].

- Rarity and Biomarker Impact: The study found no clear trends linking success probabilities to whether a disease was rare or not. The presence of efficacy biomarkers (classified as high/medium for MS and RA, but not for Crohn's) was noted as important for Phase III success but not determinative, indicating that multiple factors govern transition outcomes [16].

These findings underscore a critical principle for model verification: the use of therapeutic-area-level transition probabilities as precise predictors for specific diseases within that area can be misleading. Effective probabilistic validation must account for this heterogeneity by incorporating disease-specific data where material differences exist.

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Deriving and Applying Transition Probabilities

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive methodology for building a probabilistic drug development model, from data acquisition to validation.

Protocol 1: Deriving Transition Probabilities from Published Statistics

This protocol details the conversion of common published statistics into usable transition probabilities, corresponding to the "Conversion" node in the workflow.

Objective: To transform relative risks, odds ratios, rates, and probabilities with mismatched time frames into cycle-length-specific transition probabilities for state-transition models.

Materials and Inputs:

- Published study reports containing relevant statistics (see Table 1)

- Baseline probability for the target population (for RR and OR conversions)

- Defined cycle length for the decision model

Methodology:

From Relative Risk (RR) to Probability:

- Obtain the relative risk ((RR)) and the baseline probability ((p_{control})) from the literature.

- Calculate the probability in the treated/exposed group as: (p{treatment} = RR \times p{control}).

- Ensure the resulting probability is within the valid range [0,1]; if not, consider using a logistic transformation.

From Odds and Odds Ratios (OR) to Probability:

- If the odds ((O)) is provided, convert to probability using: (p = O / (1 + O)).

- If an odds ratio ((OR)) and baseline probability ((p{control})) are provided:

- First, convert the baseline probability to odds: (O{control} = p{control} / (1 - p{control})).

- Calculate the odds for the treated group: (O{treatment} = OR \times O{control}).

- Convert the resulting odds back to a probability: (p{treatment} = O{treatment} / (1 + O_{treatment})).

From Rates to Probabilities:

- Acquire the event rate ((r)) per unit time.

- Use the exponential transformation to calculate the probability ((p)) over a specific cycle length ((t)): (p = 1 - e^{-r \times t}).

- This formula assumes a constant hazard rate over the interval.

Cycle Length Adjustment (Two-State Model):

- For a known probability ((p)) over a given time period ((T)), and a target cycle length ((t)), the corresponding transition probability ((pt)) can be derived from the rate: (r = -ln(1-p) / T), followed by (pt = 1 - e^{-r \times t}).

- This method is appropriate only when two state transitions are possible (e.g., remaining in the state or moving to one other state).

Validation Steps:

- Cross-validate derived probabilities against any reported probabilities in the source literature.

- Perform unit checks to ensure all probabilities fall between 0 and 1.

- Confirm that probabilities for all transitions from a single state sum to 1 (or ≤1 if censoring is present).

Protocol 2: Incorporating Disease-Specific and Model Structure Adjustments

This protocol addresses the advanced modeling techniques referenced in the "Disease Adjustments" and "Model Populate" nodes of the workflow.

Objective: To adjust aggregate therapeutic-area probabilities for specific diseases and to handle models with three or more potential transitions from a single state.

Materials and Inputs:

- Disease-level clinical trial data (e.g., from Citeline's Pharmaprojects or similar databases) [16]

- Aggregate therapeutic-area transition probabilities

- State-transition model with defined health states

Methodology:

Implementing Disease-Specific Adjustments:

- Identify Material Deviations: Compare available disease-specific success probabilities (see Table 2) to therapeutic-area benchmarks. A deviation of >10 percentage points is suggested as a threshold for "meaningful" difference [16].

- Parameter Replacement: Where material deviations exist, replace the aggregate probability with the disease-specific estimate.

- Stratified Analysis: If data permits, stratify probabilities further by relevant factors such as drug class (e.g., TNF blockers) or the presence of efficacy biomarkers, though their predictive power may vary [16].

Handling Multiple Health-State Transitions:

- Challenge Identification: The standard two-state cycle-length adjustment fails when a patient can transition to three or more states in a single cycle (e.g., from "Local Cancer" to "Regional Cancer," "Metastatic Cancer," or "Death").

- Rate Matrix Approach:

- Define a transition rate for each possible state change.

- Organize these rates into a matrix ((R)).

- Use matrix exponentiation to calculate the transition probabilities over the model's cycle length: (P(t) = e^{R \times t}).

- Bootstrapping as an Alternative: When individual-level patient data is available, bootstrapping can be used to estimate the distribution of transition probabilities for complex multi-state models.

Sensitivity Analysis and Uncertainty Allocation:

- Parameter Uncertainty: Use probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) by assigning probability distributions (e.g., Beta for probabilities, Gamma for rates) to key transition parameters and running Monte Carlo simulations.

- Model Uncertainty: Evaluate the impact of using different data sources (e.g., disease-specific vs. therapeutic-area probabilities) on the model's outcomes.

- Structural Uncertainty: Test alternative model structures, such as different cycle lengths or state definitions, to ensure the robustness of conclusions derived from the transition probabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Transition Probability Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citeline's Pharmaprojects | Commercial Database | Tracks drug development programmes from start to success/failure; provides disease-level trial data. | Source for deriving disease-specific transition probabilities and analyzing development trends [16]. |

| Network Meta-Analysis | Statistical Methodology | Enables indirect comparison of multiple interventions using Bayesian framework to generate probabilistic outputs. | Generating relative treatment effects and transition probabilities for drugs not directly compared in head-to-head trials [15]. |

| Probabilistic Model Checker | Software Tool | Formally verifies temporal properties of probabilistic models against specified requirements. | Checking safety and liveness properties of state-transition models under uncertainty [17]. |

| State-Transition Model | Modeling Framework | A Markov or semi-Markov model that simulates the progression of cohorts through health states using transition probabilities. | Core structure for cost-effectiveness analysis and drug development risk projection [15]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Computational Algorithm | Randomly samples input distributions (e.g., of transition probabilities) to quantify outcome uncertainty. | Conducting probabilistic sensitivity analysis to understand the impact of parameter uncertainty on model results [15]. |

Transition probabilities are more than mere inputs for clinical development models; they are the fundamental parameters that encode the complex, stochastic reality of drug development into a verifiable and validatable quantitative framework. Their accurate derivation from published evidence—whether from rates, relative risks, or odds ratios—and their proper adjustment for disease-specific contexts are critical steps in building models that truly reflect underlying risks. The methodological protocols and toolkit presented here provide a structured approach for researchers to quantify development risk rigorously. By applying these principles within the broader context of probabilistic verification and validation, modelers can enhance the reliability of their predictions, ultimately supporting more informed and resilient decision-making in pharmaceutical research and development.

Historical Context and the Evolution of Probabilistic Analysis in Biomedical Research

The integration of probabilistic reasoning into biomedical research represents a fundamental paradigm shift from authority-based medicine to evidence-based science. This transition, which began centuries ago, has transformed how researchers quantify therapeutic effectiveness, validate models, and manage uncertainty in clinical decision-making. The historical development of this approach reveals a persistent tension between clinical tradition and mathematical formalization, with key breakthroughs often emerging from interdisciplinary collaboration.

The 18th century marked a crucial turning point, as physicians began moving away from absolute confidence in medical authority toward reliance on relative results based on systematic observation [18]. British naval physician James Lind captured this emerging probabilistic mindset in 1772 when he noted that while "a work more perfect and remedies more absolutely certain might perhaps have been expected from an inspection of several thousand patients," such "certainty was deceitful" because "more enlarged experience must ever evince the fallacy of positive assertions in the healing art" [18]. This recognition of inherent uncertainty in therapeutic outcomes laid the groundwork for more formal statistical approaches.

Historical Foundations: Key Figures and Conceptual Breakthroughs

Early Pioneers of Medical Probability

Table 1: Key Historical Figures in Medical Probabilistic Reasoning

| Figure | Time Period | Contribution | Conceptual Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| James Lind | 1716-1794 | Systematic observation and reporting of all cases (successes and failures) | Unconscious probabilistic reasoning through complete case reporting [18] |

| John Gregory | 1724-1773 | Explicit use of term "probability" in medical context | Conscious, pre-mathematical probabilistic reasoning [18] |

| John Haygarth | 1740-1824 | Application of mathematical probability to smallpox infection | Conscious, mathematical mode using "doctrine of chances" [18] |

| Carl Liebermeister | 1833-1901 | Probability theory applied to therapeutic statistics | Radical solution to problem of arbitrary statistical thresholds [19] |

The 19th century witnessed further formalization of these approaches. German physician Carl Liebermeister made remarkable contributions with his 1877 paper "Über Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung in Anwendung auf therapeutische Statistik" (On Probability Theory Applied to Therapeutic Statistics), which offered innovative solutions to the problem of arbitrary probability thresholds in assessing therapeutic effectiveness [19]. Liebermeister recognized that available statistical theory was "so far been too incomplete and inconvenient" for practical clinical use, and he challenged the prevailing "unshakeable dogma" that "series of observations which do not consist of very large numbers cannot prove anything at all" [19]. His work provided building blocks for a paradigm shift in medical statistics that would have better served clinicians than today's predominant methodology.

The Formalization of Statistical Methods

The early 20th century saw the emergence of frequentist statistics as a dominant paradigm, largely driven by practical considerations. As noted in historical analyses, "prior to the computer age, you had to be a serious mathematician to do a proper Bayesian calculation," but frequentist methods could be implemented using "probability tables in big books that mere mortals such as you or I could pull off the shelf" [20]. This accessibility led to widespread adoption, though not always with proper understanding. By 1929, a review of 200 medical research papers found that 90% should have used statistical methods but didn't, and just three years later, concerns were already being raised about frequent violations of "the fundamental principles of statistical or of general logical reasoning" [20].

Diagram 1: Historical Evolution of Probabilistic Analysis in Biomedical Research

Modern Probabilistic Analysis: Applications and Protocols

Current Applications in Biomedical Research

The life science analytics market, valued at USD 11.27 billion in 2025, reflects the massive adoption of probabilistic and data analytics techniques across biomedical research [21]. This growth is driven by several key applications:

Drug Discovery and Development: Advanced analytics help identify promising drug candidates, predict trial outcomes, and optimize study protocols to reduce time and costs [21]. The integration of diverse data sources, including genomics and real-world evidence, enables more informed decision-making throughout the R&D pipeline.

Clinical Data Science Evolution: Traditional clinical data management is evolving into clinical data science, with professionals shifting from operational tasks (data collection and cleaning) to strategic contributions (generating insights and predicting outcomes) [22]. This transition requires new skill sets and represents a fundamental change in how clinical data is utilized.

Risk-Based Approaches: Regulatory support for risk-based quality management (RBQM) and data management is encouraging sponsors to focus on critical-to-quality factors rather than comprehensive data review [22]. This approach introduces higher data quality through proactive issue detection, greater resource efficiency via centralized data reviews, and shorter study timelines.

Protocol: Model-Based Experimental Manipulation of Probabilistic Behavior

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Probabilistic Behavioral Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Intertemporal Choice Task (ICT) | Presents series of choices between immediate smaller and delayed larger rewards to measure delay discounting [23] | Standardized task parameters: reward amounts, delay intervals, trial counts |

| Latent Variable Models | Probabilistically links behavioral observations to underlying cognitive processes using generative equations [23] | Various model architectures: exponential, hyperbolic discounting functions; softmax choice rules |

| Parameter Estimation Algorithms | Calibrates model parameters from individual choice sequences using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods [23] | Optimization techniques: Markov Chain Monte Carlo, gradient descent, expectation-maximization |

| Adaptive Design Optimization | Generates experimental trials designed to elicit specific behavioral probabilities based on individual model parameters [23] | Algorithmic approaches: mutual information maximization, entropy minimization |

Experimental Workflow for Delay Discounting Studies:

This protocol exemplifies the modern probabilistic approach to modeling cognitive processes, with specific application to delay discounting behavior [23].

Materials and Setup:

- Implement computerized Intertemporal Choice Task (ICT) with precise timing controls

- Configure trial parameters: immediate reward (e.g., $10-$100), delayed reward (e.g., $20-$100), delay intervals (e.g., 1 day-1 year)

- Establish data collection system capturing choice responses and reaction times

Procedure:

- Run A (Model Inference):

- Present series of binary choice trials following standardized ICT protocol

- Collect minimum of 50-100 trials per participant to ensure reliable parameter estimation

- Record complete trial-by-trial data:

d = {(x_i, y_i), i = 1,2,...,T}wherex_iare predictor vectors of immediate/delayed options andy_iare observed choices [23]

Model Calibration:

- Estimate individual discounting parameters using maximum likelihood estimation

- Validate model fit through posterior predictive checks and residual analysis

- Compare alternative models using information criteria (AIC/BIC) or cross-validation

Run B (Model Application):

- Generate adaptive trials designed to induce specific discounting probabilities (0.1-0.9) using calibrated model

- Present second ICT with experimentally manipulated trial parameters based on model predictions

- Collect behavioral responses for validation of model predictions

Validation Analysis:

- Compare predicted versus observed choice probabilities across the induced probability range

- Calculate prediction error metrics (e.g., mean squared error, classification accuracy)

- Assess model validity through out-of-sample prediction performance [23]

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Probabilistic Model Validation

Probabilistic Approaches to Model Verification and Validation

Framework for Probabilistic Model Validation

Modern probabilistic model validation represents a formal approach to assessing predictive accuracy while accounting for approximation error and uncertainty [24]. This framework is particularly relevant for computational models used in biomedical research, where both inherent variability (aleatory uncertainty) and limited knowledge (epistemic uncertainty) must be addressed.

The core validation procedure involves several key components:

Uncertainty Representation: Random quantities are represented using functional analytic approaches, particularly polynomial chaos expansions (PCEs), which permit the formulation of uncertainty assessment as a problem of approximation theory [24].

Parameter Calibration: Statistical procedures calibrate uncertain parameters from experimental or model-based measurements, using PCEs to represent inherent uncertainty of model parameters [24].

Hypothesis Testing: Simple hypothesis tests explore the validation of the computational model assumed for the physics (or biology) of the problem, comparing model predictions with experimental evidence [24].

Protocol: Probabilistic Model Checking for Biomedical Systems

Probabilistic model checking provides a formal verification approach for stochastic systems, with growing applications in biological modeling and healthcare systems [25].

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Probabilistic model checking software (PRISM, Storm, or Modest toolset)

- Model specification in appropriate formalism (DTMC, CTMC, MDP)

- Temporal logic properties (PCTL, CSL) encoding biological hypotheses

- High-performance computing resources for large state spaces

Procedure:

Model Formulation:

- Define system components and their probabilistic interactions

- Select appropriate modeling formalism based on system characteristics:

- Discrete-time Markov chains (DTMCs) for discrete probabilistic systems

- Continuous-time Markov chains (CTMCs) for systems with timing properties

- Markov decision processes (MDPs) for systems with nondeterminism and probability

Property Specification:

- Formalize biological hypotheses as temporal logic properties:

P≥0.95 [F≤100 "target_expression"](The probability that target expression level is eventually reached within 100 time units is at least 0.95)S≥0.98 ["steady_state"](The long-run probability of being in steady state is at least 0.98)

- Formalize biological hypotheses as temporal logic properties:

Model Checking Execution:

- Implement numerical algorithms for probability computation

- Handle state space explosion through:

- Symbolic methods using binary decision diagrams

- Statistical model checking for very large models

- Abstraction refinement techniques

Validation Metrics:

- Compare computation-observation agreement using statistical distance measures

- Implement validation metrics accounting for both aleatory and epistemic uncertainty

- Assess predictive capability through out-of-sample testing [24]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Integration of AI and Machine Learning

The life science analytics market is witnessing rapid integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, particularly for drug discovery and development, personalized medicine, and disease management [21]. This trend is shifting the industry from initial AI hype toward "smart automation" that leverages the best automation approach—whether AI, rule-based, or other—to optimize efficiency and manage risk for each specific use case [22].

Key developments include:

AI-Augmented Medical Coding: Modified workflows where traditional rule-based automation handles most coding, with AI providing suggestions or automatic coding for remaining records [22]

Predictive Analytics Growth: The predictive segment is anticipated to grow with the highest CAGR in the life science analytics market, using statistical models and machine learning to forecast patient responses, identify clinical trial risks, and optimize market strategies [21]

Risk-Based Approaches: Regulatory encouragement of risk-based quality management (RBQM) is prompting sponsors to shift from traditional data collection to dynamic, analytical tasks focused on critical data points [22]

Advancing Model Validation Frameworks

Future developments in probabilistic model validation will need to address several challenging frontiers:

History-Dependent Models: Extension of validation frameworks to latent variable models with history dependence, where current behavior depends on previous states and choices [23]

Multi-Categorical Response Models: Development of validation approaches for response models with multiple categories beyond binary choice paradigms [23]

Uncertainty Quantification: Enhanced methods for characterizing both epistemic and aleatory uncertainties, particularly when dealing with limited experimental data [24]

The continued evolution of probabilistic analysis in biomedical research represents the modern instantiation of a centuries-long development toward more rigorous, quantitative assessment of medical evidence. From the "arithmetical observation" movement of the 18th century to contemporary AI-driven analytics, the fundamental goal remains consistent: to replace unfounded certainty with measured probability, thereby advancing both scientific understanding and clinical practice.

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) represents a paradigm shift in how pharmaceuticals are developed and evaluated. By leveraging quantitative modeling and simulation, MIDD provides a framework to integrate knowledge from diverse data sources, supporting more efficient and confident decision-making. These approaches allow researchers to extrapolate and interpolate information, enabling predictions of drug behavior in scenarios where direct clinical data may be limited or unavailable. The four methodological tools discussed in this article—Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, Exposure-Response analysis, and Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA)—form the cornerstone of modern MIDD. Within the context of model verification and validation, a probabilistic framework offers a rigorous methodology for quantifying uncertainty, assessing model credibility, and establishing the boundaries of reliable inference, thereby ensuring that model-based decisions are both scientifically sound and statistically justified [26] [27].

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK modeling is a mathematical technique that predicts the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of compounds by incorporating physiological, physicochemical, and biochemical parameters. Unlike traditional compartmental models that rely on empirical data fitting, PBPK models represent the body as a network of anatomically meaningful compartments, each corresponding to specific organs or tissues interconnected by the circulatory system [28] [26]. This physiological basis allows for a more mechanistic and realistic representation of drug disposition. The primary output of a PBPK simulation is a set of concentration-time profiles in plasma and various tissues, providing a comprehensive view of a drug's temporal behavior within the body [28].

Key Applications in Drug Development

Table 1: Key Applications of PBPK Modeling

| Application Area | Specific Use | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Drug Development | Extrapolating adult PK to children by incorporating age-dependent physiological changes [28]. | Reduces the need for extensive clinical trials in pediatric populations, addressing ethical and practical challenges. |

| Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Assessment | Predicting the potential for metabolic interactions when drugs are co-administered [26] [29]. | Informs contraindications and dosing recommendations, enhancing patient safety. |

| Formulation Optimization | Simulating absorption for different formulations (e.g., immediate vs. extended release) [26]. | Guides the selection of optimal formulation properties prior to costly manufacturing. |

| Special Population Dosing | Predicting PK in patients with organ impairment (e.g., hepatic or renal dysfunction) by adjusting corresponding physiological parameters [28] [29]. | Supports dose adjustment and labeling for subpopulations. |

| First-in-Human Dose Selection | Predicting safe and efficacious starting doses from preclinical data [29]. | De-risks early clinical trials and helps establish a rational starting point for dosing. |

Experimental Protocol for PBPK Model Development

The development of a whole-body PBPK model follows a systematic, stepwise protocol.

- Model Structure Specification: Define the model's anatomical representation. This involves selecting which organs and tissues to include as separate compartments based on the drug's properties and the model's purpose. Tissues with similar properties can be "lumped" together to simplify the model without sacrificing critical functionality [28].

- Tissue Model Selection: For each tissue compartment, determine the appropriate sub-model. The most common is the perfusion rate-limited (well-stirred) model, which assumes rapid equilibrium between blood and tissue. For drugs facing significant diffusion barriers (e.g., across the blood-brain barrier), a more complex permeability rate-limited model is required [28].