Stochastic Model Verification: Procedures for Validating Predictive Models in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to stochastic model verification for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Stochastic Model Verification: Procedures for Validating Predictive Models in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to stochastic model verification for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of probabilistic model checking and uncertainty quantification, details methodological applications from model calibration to synthesis, addresses advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques for complex models, and compares validation frameworks and performance metrics. The content synthesizes current methodologies to enhance the reliability and regulatory acceptance of stochastic models in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Stochastic Model Verification: Core Principles and Uncertainty

Defining Stochastic Model Verification vs. Validation

In scientific research and industrial development, the trustworthiness of stochastic models is paramount. These models, which explicitly account for randomness and uncertainty in system behavior, are critical in fields ranging from drug development to energy management. Establishing confidence in these models requires rigorous Verification and Validation (V&V) processes. Although sometimes used interchangeably, verification and validation are distinct activities that answer two fundamental questions: Verification asks, "Have we built the model correctly?" ensuring the computational implementation accurately represents the intended mathematical model and its stochastic properties. Validation asks, "Have we built the correct model?" determining how well the model's output corresponds to real-world behavior and observations [1] [2] [3].

For stochastic models, the V&V process presents unique challenges. It must confirm that the implementation correctly captures probabilistic elements, such as random processes and uncertainty propagation, and must demonstrate that the model's statistical output is consistent with empirical data. The framework established for traditional computational science and engineering (CSE) models provides a foundation, but its application to Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) and complex stochastic systems requires specific adaptations [3]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for the verification and validation of stochastic models, providing researchers with a structured approach to ensure model credibility.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Core Concepts

- Stochastic Model: A mathematical representation of a system that incorporates random variables or processes to account for uncertainty or inherent randomness in its behavior. Its outputs are often characterized by probability distributions rather than deterministic values.

- Verification: The process of confirming that a computational model is implemented correctly according to its specifications and underlying mathematical assumptions. It is a check for numerical and coding errors [2]. In the context of stochastic models, this includes verifying that random number generators, sampling algorithms, and uncertainty propagation are functioning as intended.

- Validation: The process of substantiating that a model, within its domain of applicability, possesses a satisfactory range of accuracy consistent with its intended purpose [2]. For stochastic models, this involves comparing the model's probabilistic outputs (e.g., means, variances, prediction intervals) with observed data from the real-world system.

The V&V Framework for Stochastic Models

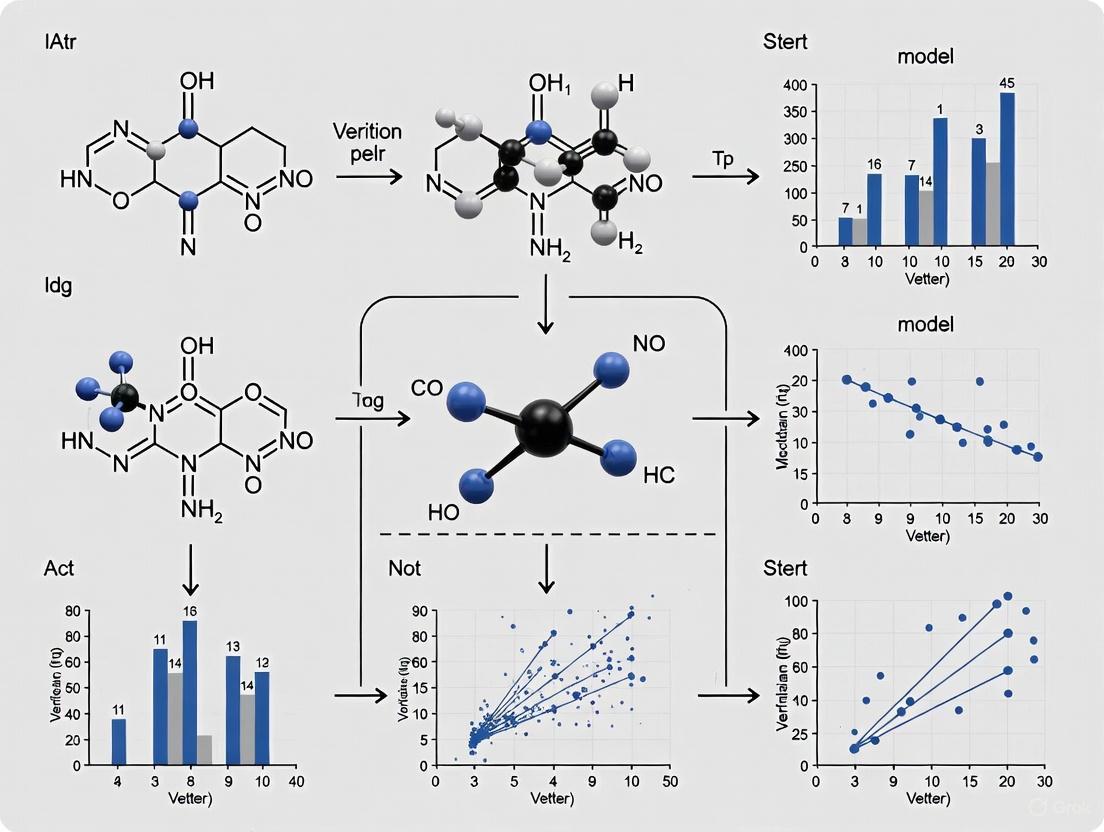

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of verification and validation within the stochastic model development lifecycle, highlighting the distinct roles of computational/mathematical checks against the real world.

Verification Protocols for Stochastic Models

The goal of verification is to ensure the computational model is solved correctly. For stochastic models, this involves checking both the deterministic numerical aspects and the specific implementation of stochastic components.

Stochastic Verification Tests

Table 1: Key Verification Tests for Stochastic Models

| Test Category | Protocol Description | Expected Outcome | Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic Limits | Run the model under conditions where randomness is eliminated (e.g., variance set to zero) or where an analytical solution is known. | Model outputs match the known deterministic solution or analytical result. | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) < 1e-10 relative to analytical solution. |

| Monte Carlo Benchmarking | Compare results against a simple, independently coded Monte Carlo simulation for a simplified version of the model. | Output distributions from the complex and benchmark models are statistically indistinguishable. | P-value > 0.05 in two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. |

| Moment Recovery | Input a known distribution and verify that the model's sampled outputs correctly recover the distribution's moments (mean, variance, skewness). | Sampled moments converge to theoretical values as the number of iterations increases. | Relative error of sampled mean and variance < 1%. |

| Random Number Generator (RNG) Testing | Subject the RNG to statistical test suites (e.g., Dieharder, TestU01) to ensure it produces sequences free of detectable patterns. | RNG passes a comprehensive set of statistical tests for randomness. | P-values uniformly distributed in [0,1] for all test suite items. |

| Convergence Analysis | Evaluate how model outputs change with increasing number of simulations (N) and decreasing numerical discretization (e.g., time step Δt). | Outputs converge to a stable value as N increases and Δt decreases. | Output variance < 5% of mean for N > 10,000. |

Detailed Protocol: Numerical Convergence Analysis

Objective: To ensure that the numerical solution of the stochastic model is stable and accurate, independent of the numerical parameters used for simulation.

Methodology:

- Parameter Selection: Identify key numerical parameters, such as the number of stochastic realizations (N), time step (Δt), and mesh size for spatial models.

- Baseline Establishment: Define a "baseline" simulation using the finest practical resolution (largest N, smallest Δt).

- Parameter Variation: Run multiple simulations while systematically varying one parameter at a time (e.g., N = 100, 1,000, 10,000; Δt = 1.0, 0.1, 0.01).

- Output Comparison: For each simulation, compute key output metrics (e.g., mean, 95th percentile, probability of failure). Plot these metrics against the varying parameter (e.g., 1/N, Δt).

- Convergence Criterion: Establish a convergence threshold (e.g., relative change in output < 1% between successive parameter refinements). The model is considered verified for a given set of numerical parameters when the outputs remain within this threshold.

Tools and Technologies:

- Simulation & Modeling: MATLAB/Simulink, Ansys, National Instruments LabVIEW [1].

- Version Control: Git for tracking code and model changes.

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) clusters are often essential for running large ensembles of simulations required for convergence testing.

Validation Protocols for Stochastic Models

Validation assesses the model's predictive accuracy against empirical data, focusing on the model's ability to replicate the statistical behavior of the real-world system.

Stochastic Validation Tests

Table 2: Key Validation Tests for Stochastic Models

| Validation Method | Protocol Description | Data Requirements | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis Testing | Formally test if the model's output distribution is equal to the observed data distribution. Uses tests like t-test (for means) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov (for full distributions) [2]. | Independent experimental or observational dataset not used for model calibration. | Fail to reject H₀ (model = system) at α=0.05 significance level. A low p-value indicates the model is not a valid representation. |

| Confidence Interval Overlap | Calculate confidence intervals for the mean (or other statistics) of both model outputs and observed data. | Sufficient data points to compute reliable confidence intervals (typically n > 30). | Significant overlap between model and data confidence intervals suggests model validity. |

| Bayesian Validation | Use Bayesian methods to compute the posterior probability of the model given the observed validation data. | A prior probability for the model and the likelihood function for the data. | A high posterior probability provides strong evidence for model validity. |

| Time Series Validation | For dynamic models, compare time-series outputs (e.g., prediction intervals, autocorrelation) to observed temporal data. | Time-series data from the real system under comparable initial and boundary conditions. | Observed data falls within the model's prediction intervals, and key temporal patterns are reproduced. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Assess how variation in model inputs (especially stochastic ones) affects the outputs. A valid model should be sensitive to inputs known to drive the real system. | Not required, but domain knowledge is needed to identify critical inputs. | Model outputs are most sensitive to inputs that are known to be key drivers in the real system. |

Detailed Protocol: Input-Output Transformation Validation

Objective: To quantitatively compare the model's input-output transformations against those of the real system for the same set of input conditions [2].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Collect a set of input conditions (Xsystem) and corresponding output measures of performance (Ysystem) from the real system. This must be a separate dataset not used in model training or calibration.

- Model Execution: Run the stochastic model using the exact same input conditions (X_system). Due to the model's stochastic nature, perform multiple (n ≥ 30) independent replications for each input condition to build an output distribution.

- Output Aggregation: For each input condition, calculate the average model output, E(Y_model), across the replications.

- Statistical Comparison: Use a paired t-test to compare the set of system outputs (Ysystem) against the set of average model outputs (E(Ymodel)).

- Null Hypothesis, H₀: E(Ymodel) = Ysystem

- Alternative Hypothesis, H₁: E(Ymodel) ≠ Ysystem

- Model Accuracy as a Range: If a perfect match is unrealistic, define an acceptable range of accuracy [L, U] [2]. The test then becomes whether the difference D = E(Ymodel) - Ysystem falls within [L, U] for all practical purposes.

Example from Industry: A notable example is the Siemens-imec collaboration on EUV lithography. They calibrated a stochastic model to predict failure probabilities and then validated it against wafer-level experimental data. The validation showed the model could predict failure probabilities with sufficient accuracy to guide a redesign of the optical proximity correction (OPC) process, which ultimately reduced stochastic failures by one to two orders of magnitude [4]. This demonstrates a successful input-output validation with direct industrial impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key computational tools and resources essential for conducting rigorous V&V of stochastic models.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Stochastic Model V&V

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Model Checkers (e.g., PRISM, Storm) | Formal verification tools for stochastic systems; algorithmically check if a model satisfies temporal logic specifications [5]. | Verifying correctness properties of randomized algorithms or reliability of communication protocols. |

| Statistical Test Suites (e.g., Dieharder, TestU01) | A battery of statistical tests to verify the quality and randomness of Random Number Generators (RNGs). | Ensuring the foundational stochastic element of a model is free from detectable bias or correlation. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Toolkits (e.g., Chaospy, UQLab) | Software libraries for performing sensitivity analysis, uncertainty propagation, and surrogate modeling. | Quantifying the impact of input uncertainties on model outputs and identifying key drivers of uncertainty. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Parallel computing resources to manage the high computational cost of running thousands of stochastic simulations. | Performing large-scale Monte Carlo studies for convergence analysis and validation. |

| Version Control System (e.g., Git) | Tracks changes in model code, scripts, and parameters, ensuring reproducibility and collaboration. | Maintaining a history of model versions and their corresponding V&V results. |

| Data Provenance Tools | Document the origin, processing, and use of data throughout the modeling lifecycle [3]. | Ensuring validation data is traceable and used appropriately, enhancing trustworthiness. |

Integrated V&V Workflow for a Case Study: SciML for Glacier Modeling

The following diagram maps the specific V&V activities for a SciML case study based on building a DeepONet surrogate model to predict glacier velocity, loosely adapted from He et al. [3]. This illustrates how the general V&V principles are applied to a cutting-edge stochastic modeling paradigm.

Workflow Description:

- Verification (DeepONet):

- Verify Implementation: Ensure the Neural Network architecture (DeepONet) and training algorithm (e.g., Adam optimizer) are correctly implemented and that the mean-squared error loss is computed properly [3].

- Stochastic Checks: Verify the process of sampling training data from the underlying CSE model (e.g., Shallow-Shelf Approximation solver) is random and unbiased.

- Convergence Test: Monitor the training and validation loss to ensure the model converges to a stable minimum.

- Validation (Glacier Prediction):

- Collect Calibration Data: Gather recent, system-specific data (e.g., satellite measurements of glacier velocity) that was not part of the original training data [3].

- Calibrate Model Inputs: Solve an inverse problem to tune uncertain model inputs (e.g., basal friction parameters) to match the calibration data.

- Validate Predictions: Run the calibrated model to make a scientific claim (e.g., future sea-level rise contribution). Compare these predictions to independent data or alternative models to establish credibility [3].

A rigorous and disciplined approach to verification and validation is the cornerstone of developing trustworthy stochastic models. As demonstrated, verification and validation are complementary but distinct processes that address different aspects of model quality. The protocols outlined here—from convergence analysis and RNG testing to statistical hypothesis testing and input-output validation—provide a actionable framework for researchers. Adhering to these protocols, leveraging the appropriate toolkit, and transparently documenting the V&V process and its limitations are essential practices. This not only ensures the reliability of scientific conclusions drawn from the model but also builds the credibility necessary for these models to inform critical decisions in drug development, engineering design, and scientific discovery.

The Role of Probabilistic Model Checking (PMC)

Probabilistic Model Checking (PMC) is a formal verification technique for analyzing stochastic systems. It involves algorithmically checking whether a probabilistic model, such as a Markov chain or Markov decision process, satisfies specifications written in a temporal logic. Unlike traditional verification, PMC provides quantitative insights into system properties, calculating the likelihood of events or expected values of rewards/costs [5]. This approach is crucial for establishing the correctness of randomized algorithms and evaluating performance, reliability, and safety across various fields, including computer science, biology, and drug development [5].

Application Domains and Quantitative Analysis

Probabilistic Model Checking has been successfully applied to a diverse range of application domains. The table below summarizes the primary models, property specifications, and key applications for each area.

Table 1: Key Application Domains of Probabilistic Model Checking

| Application Domain | Primary PMC Models | Typical Property Specifications | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Distributed Algorithms [5] | DTMC, MDP | Probabilistic Computation Tree Logic (PCTL), Linear Temporal Logic (LTL) | Verification of consensus, leader election, and self-stabilization protocols; worst-case runtime analysis [5]. |

| Communications and Networks [5] | DTMC, MDP, Probabilistic Timed Automata (PTA), CTMC | PCTL, Continuous Stochastic Logic (CSL), reward-based extensions | Analysis of communication protocols (e.g., Bluetooth, Zigbee); network reliability and performance evaluation (e.g., QoS, dependability) [5]. |

| Computer Security [5] | MDP | PCTL, Probabilistic Timed CTL | Adversarial analysis; verification of security protocols using randomization (e.g., key generation) [5]. |

| Biological Systems [6] | DTMC, CTMC | CSL, PCTL | Analysis of complex biological pathways (e.g., FGF signalling pathway); understanding system dynamics under different stimuli [6]. |

| Drug Development (MIDD) [7] | Various quantitative models (PBPK, QSP, etc.) | Model predictions and simulations | Target identification, lead compound optimization, First-in-Human (FIH) dose prediction, clinical trial optimization [7]. |

The quantitative data produced by PMC analyses for these domains can be complex. The table below provides a comparative overview of common quantitative measures.

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Data from PMC Analyses

| Quantitative Measure | Description | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Probability of Event | The likelihood that a specific temporal logic formula is satisfied. | "The probability that consensus is reached within 5 rounds exceeds 0.99" [5]. |

| Expected Reward/Cost | The expected cumulative value of a reward/cost structure over a path. | "The expected energy consumption before system shutdown is at most 150 Joules" [5]. |

| Long-Run Average | The steady-state or long-run average value of a reward. | "The long-run availability of the network is at least 98%" [5]. |

| Mean Time to Failure (MTTF) | The expected time until a critical failure occurs. | "The MTTF for the optical network topology is at least 200 hours" [5]. |

| Instantaneous Measure | The value of a state-based reward at a specific time instant. | "The protein concentration at time t=100 is above the critical threshold with probability 0.9" [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for PMC Analysis

Protocol: PMC Analysis of a Biological Signalling Pathway

This protocol outlines the methodology for applying PMC to analyze a complex biological system, as demonstrated in the study of the Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signalling pathway [6].

System Definition and Abstraction

- Objective: Define the biological question of interest and the scope of the model.

- Procedure: Identify the key chemical species (e.g., proteins, ligands, receptors) and their possible states (e.g., phosphorylated, bound). Determine the relevant biochemical reactions and their kinetic parameters (e.g., reaction rates), often derived from laboratory data or literature.

- Output: A list of species, states, and reactions that define the system's dynamics.

Model Construction

- Objective: Translate the abstracted system into a formal probabilistic model.

- Procedure: Construct a Continuous-Time Markov Chain (CTMC) where each state represents a unique combination of the species' concentrations or states. Model transitions between states as probabilistic events, with rates determined by the kinetic parameters of the corresponding reactions. This can be done using the PRISM model checker's modelling language [6].

- Output: A PRISM model file (

.prism) encoding the CTMC.

Property Formalization

- Objective: Specify the biological hypotheses as quantitative properties using a temporal logic.

- Procedure: Formulate properties in Continuous Stochastic Logic (CSL). Example properties for the FGF pathway include [6]:

P=? [ F ( AKT_concentration > threshold ) ]- "What is the probability that the concentration of AKT eventually exceeds a given threshold?"S=? [ FGFR3_active > 50 ]- "What is the long-run probability that more than 50 units of FGFR3 are active?"

- Output: A set of CSL queries to be checked against the model.

Model Checking Execution

- Objective: Compute the quantitative results for the specified properties.

- Procedure: Use the PRISM model checker to verify each CSL property against the constructed CTMC model. This process involves exhaustive state-space exploration and numerical computation.

- Output: Numerical results (e.g., probabilities, expected values) for each query.

Result Analysis and Model Refinement

- Objective: Interpret the results in their biological context and refine the model if necessary.

- Procedure: Analyze the quantitative outputs to validate hypotheses or gain new insights into the pathway's dynamics. Perform parameter sensitivity analysis or model checking under different initial conditions (scenarios) to test the system's robustness. If results contradict established biological knowledge, the model may need refinement.

- Output: A biological interpretation of the results and, if needed, a refined model.

Protocol: Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) with PMC

This protocol describes how PMC and related quantitative modeling techniques are integrated into the drug development pipeline following a "fit-for-purpose" strategy [7].

Define Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU)

- Objective: Precisely define the scientific or clinical question the model will address and the specific context in which the model's predictions will be used.

- Procedure: In collaboration with a cross-functional team (pharmacometricians, clinicians, statisticians), draft a formal COU statement. This specifies the role of the model (e.g., for internal decision-making, regulatory submission), the decisions it will inform, and the associated uncertainties.

- Output: A documented QOI and COU.

Select Fit-for-Purpose Modeling Tool

- Objective: Choose the quantitative modeling methodology most appropriate for the QOI and development stage.

- Procedure: Select from a suite of tools based on the problem. For example:

- First-in-Human (FIH) Dose Prediction: Use Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling or quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) [7].

- Clinical Trial Optimization: Use clinical trial simulation or adaptive trial design methodologies [7].

- Population Variability Analysis: Use Population Pharmacokinetics (PPK) and Exposure-Response (ER) modeling [7].

- Output: A selected modeling approach.

Model Building, Calibration, and Verification

- Objective: Develop, parameterize, and verify the technical correctness of the model.

- Procedure: Build the model structure based on physiological/ pharmacological knowledge (for mechanistic models) or clinical data (for empirical models). Calibrate model parameters using in vitro, in vivo, or clinical data. Verify that the model implementation is correct.

- Output: A calibrated and verified model.

Model Validation and Simulation

- Objective: Assess the model's predictive performance and run simulations to answer the QOI.

- Procedure: Validate the model by comparing its predictions against a separate dataset not used for calibration. Once validated, execute simulations to explore clinical scenarios, optimize doses, or predict trial outcomes.

- Output: Validation report and simulation results.

Regulatory Submission and Integration

- Objective: Integrate model evidence into the overall development strategy and regulatory submissions.

- Procedure: Incorporate model findings, including assumptions, limitations, and results, into regulatory briefing documents and dossiers (e.g., for 505(b)(2) applications). Effectively communicate the model's value in supporting key development decisions [7].

- Output: Model-integrated evidence included in regulatory filings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The effective application of Probabilistic Model Checking relies on a suite of software tools and formalisms. The following table details the key "research reagents" essential for conducting PMC analyses.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Probabilistic Model Checking Research

| Tool or Formalism | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| PRISM [8] | Software Tool | A general-purpose, open-source probabilistic model checker supporting analysis of DTMCs, CTMCs, and MDPs. It features a high-level modeling language and multiple analysis engines [5] [6]. |

| Storm [5] | Software Tool | A high-performance probabilistic model checker designed for scalability and efficiency, offering both exact and approximate analysis methods for large, complex models. |

| PCTL [5] | Formalism (Temporal Logic) | Probabilistic Computation Tree Logic. A property specification language used to express quantitative properties over DTMCs and MDPs (e.g., "the probability of eventual success is at least 0.95"). |

| CSL [5] | Formalism (Temporal Logic) | Continuous Stochastic Logic. An extension of PCTL for specifying properties over CTMCs, incorporating time intervals and steady-state probabilities. |

| Markov Decision Process (MDP) [5] [8] | Formalism (Mathematical Model) | A modeling formalism that represents systems with both probabilistic behavior and nondeterministic choices, ideal for modeling concurrency and adversarial environments. |

| PMC-VIS [8] | Software Tool | An interactive visualization tool that works with PRISM to help explore large MDPs and the computed PMC results, enhancing the understandability of models and schedulers. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Model [7] | Modeling Approach | A mechanistic modeling approach used in MIDD to predict a drug's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) based on physiological parameters and drug properties. |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) [7] | Modeling Approach | An integrative modeling framework that combines systems biology with pharmacology to generate mechanism-based predictions on drug behavior and treatment effects across biological scales. |

The verification of stochastic models in drug development is fundamentally shaped by three interconnected challenges: uncertainty, nondeterminism, and partial observability. These are not merely statistical inconveniences but core characteristics of biological systems and clinical environments that must be explicitly modeled and reasoned about to build reliable, predictive tools. Uncertainty manifests from random fluctuations in biological processes, such as mutation acquisition leading to drug resistance or unpredictable patient responses to therapy [9]. Nondeterminism arises when a system's behavior is not uniquely determined by its current state, often due to the availability of multiple therapeutic actions or scheduling decisions, requiring sophisticated optimization techniques [10] [11]. Partial observability reflects the practical reality that critical system states, such as the exact number of drug-resistant cells or a patient's true disease progression, cannot be directly measured but must be inferred from noisy, incomplete data like sparse blood samples or patient-reported outcomes [12] [11]. Framing drug development within this context moves the field beyond deterministic models, which assume average behaviors and full system knowledge, toward more realistic stochastic frameworks that can capture the intrinsic variability and hidden dynamics of disease and treatment [9].

The limitations of deterministic models are particularly acute in early-phase trials and when modeling small populations, where random events can have disproportionately large impacts on outcomes [9]. The ULTIMATE framework represents a significant theoretical advance by formally unifying the modeling of probabilistic and nondeterministic uncertainty, discrete and continuous time, and partial observability, enabling the joint analysis of multiple interdependent stochastic models [10]. This holistic approach is vital for complex problems in pharmacology, where a single model type is often insufficient to capture all relevant properties of a software-intensive system and its context.

Quantitative Landscape of Stochastic Challenges

The following table summarizes the key stochastic model types used to address these challenges, along with their primary applications in drug development.

Table 1: Stochastic Model Types for Drug Development Challenges

| Model Type | Formal Representation of Challenges | Primary Drug Development Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) [11] | Probabilistic transitions (Uncertainty), multiple possible actions (Nondeterminism), distinguishes between internal state and external observations (Partial Observability) | Clinical trial optimization [13], personalized dosing strategy synthesis [11] |

| Markov Decision Process (MDP) [10] | Probabilistic transitions (Uncertainty), multiple possible actions (Nondeterminism) | General treatment strategy optimization |

| Stochastic Agent-Based Model (ABM) [14] | Randomness in agent behavior/interactions (Uncertainty), can incorporate action choices (Nondeterminism) | Disease spread modeling [14], intra-tumor heterogeneity and evolution [15] |

| Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) / First-Passage-Time (FPT) Model [15] | Models continuous variables with random noise (Uncertainty) | Tumor growth dynamics and time-to-event metrics (e.g., remission, recurrence) [15] |

| Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) [12] | Generative model learning distributions from data (Uncertainty), infers unobserved patterns (Partial Observability) | Analysis of multi-item Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) [12] |

Quantifying the impact of these challenges is crucial for robust experimental design and analysis. The table below outlines common quantitative metrics and data sources used for this purpose in pharmacological research.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics and Data for Challenge Analysis

| Challenge | Key Quantitative Metrics | Exemplar Pharmacological Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Variance in population size [9]; Credible intervals from posterior predictive distributions [14]; Probability density of first-passage-time [15] | Time-to-toxicity data [13]; Tumor volume time-series from murine models [15] |

| Nondeterminism | Expected reward/value function [11] [16]; Probability of property satisfaction under optimal strategy [10] | Dose-toxicity data from phase I trials [13]; Historical treatment response data |

| Partial Observability | Belief state distributions [11] [16]; Reconstruction error in generative models [12]; Calibration accuracy on synthetic data [14] | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) [12]; Sparse pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) samples |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian Verification of Stochastic Agent-Based Disease Models

1. Objective: To verify the calibration of a stochastic Agent-Based Model (ABM) of disease spread, ensuring robust parameter inference for reliable outbreak predictions [14].

2. Background: ABMs simulate individuals (agents) in a population, each following rules for movement, interaction, and disease state transitions (e.g., Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Recovered). Their stochastic nature is ideal for capturing heterogeneous population spread but complicates parameter estimation. This protocol uses Simulation-Based Calibration (SBC), a verification method that tests the calibration process itself using synthetic data, isolating calibration errors from model structural errors [14].

3. Experimental Workflow:

4. Materials & Reagents:

- Computational Framework: High-performance computing cluster.

- Software: PRISM model checker [11], custom ABM code (e.g., Python, C++), Bayesian inference libraries (e.g., PyMC3, Stan).

- Data: Synthetic data generated from the ABM with known parameter values [14].

5. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1 (Model Definition): Formally define the ABM's state transitions, observables, and prior distributions for model parameters (e.g., infection rate, recovery rate) [14].

- Step 2 (Synthetic Data Generation): Run the ABM multiple times with a fixed set of known "ground truth" parameters to generate a synthetic dataset of observables (e.g., daily infection counts). This eliminates model structure error and data quality issues [14].

- Step 3 (Bayesian Inference): Calibrate the ABM against the synthetic dataset using one of two methods:

- Step 4 (Calibration Verification - SBC): Analyze the resulting posterior distributions. A well-calibrated method will produce posteriors that are, on average, centered on the known ground-truth parameters used in Step 2. Discrepancies indicate issues with the calibration method itself [14].

- Step 5 (Overall Model Validation): Only after verification, calibrate the model against real-world data and use posterior predictive checks to compare model projections to actual outcomes [14].

Protocol 2: Generative Stochastic Modeling of Patient-Reported Outcomes

1. Objective: To characterize multi-item Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and their relationship to drug concentrations and clinical variables, addressing partial observability of a patient's true health status [12].

2. Background: PROMs are challenging to analyze due to their multidimensional, discrete, and often skewed nature. Traditional methods like linear mixed-effects models can be limited by their structural assumptions. The Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM), a generative stochastic model, learns the joint probability distribution of all variables without pre-specified assumptions, inferring hidden patterns and handling missing data [12].

3. Experimental Workflow:

4. Materials & Reagents:

- Data: Longitudinal, item-level PROM data, mid-dose drug concentrations, clinical variables (e.g., CD4 count, viral load) [12].

- Software: Machine learning libraries with RBM implementations (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Hardware: GPU-accelerated computing resources for efficient training.

5. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1 (Data Compilation): Assemble a dataset where each data point includes all PROM items, drug concentrations, and clinical variables for a patient at a given time [12].

- Step 2 (Model Training): Train the RBM using the Persistent Contrastive Divergence (PCD) algorithm. The visible layer nodes represent the compiled data. The model learns weights and biases to minimize the energy of compatible configurations [12].

- Step 3 (Inference): Use the trained model to infer the states of the hidden nodes for any given patient's data. These hidden states represent latent features that capture the complex, unobserved dependencies between the visible variables [12].

- Step 4 (Variable Importance Analysis): Leverage the model's structure to rank the importance of all input variables (PROM items, drug levels, clinical markers) in predicting post-baseline PROMs, providing insight into key drivers of patient experience [12].

- Step 5 (Simulation): Use the trained RBM as a generative tool to simulate individual-level disease progression trajectories based on baseline variables, supporting trial design and therapeutic drug monitoring [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Relevance to Core Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| PRISM Model Checker [10] [11] | A probabilistic model checker for formal verification of stochastic models. | Verifies properties of MDPs and POMDPs, handling uncertainty and nondeterminism [10] [11]. |

| Gillespie Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) [9] | Exact simulation of trajectories for biochemical reaction networks. | Captures intrinsic uncertainty (process noise) in biological systems [9]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) [14] | Bayesian parameter inference for models with computable likelihoods. | Quantifies parameter uncertainty from observational data [14]. |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) [14] | Bayesian parameter inference for complex models where likelihoods are intractable. | Enables calibration under uncertainty when likelihood-based methods fail [14]. |

| Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) [12] | A generative neural network for learning complex data distributions. | Infers hidden features from partially observable data (e.g., PROMs) [12]. |

| Kalman Filter Layer [17] | A layer for deep learning models that performs closed-form Gaussian inference. | Maintains a belief state for optimal decision-making under partial observability [17]. |

| Simulation-Based Calibration (SBC) [14] | A verification method that uses synthetic data to test calibration procedures. | Isolates and identifies errors in model calibration under uncertainty [14]. |

Multi-model stochastic systems provide a sophisticated formalism for analyzing complex systems characterized by probabilistic behavior, multiple interdependent components, and distinct operational modes. The UniversaL stochasTIc Modelling, verificAtion and synThEsis (ULTIMATE) framework represents a foundational approach in this domain, designed to overcome the limitations of analyzing single, isolated models [18]. Its core innovation lies in enabling the joint analysis of multiple interdependent stochastic models of different types, a capability beyond the reach of conventional probabilistic model checking (PMC) techniques [18].

The ULTIMATE framework unifies, for the first time, the modeling of several critical aspects of complex systems:

- Probabilistic and nondeterministic uncertainty.

- Discrete and continuous time.

- Partial observability.

- The use of both Bayesian and frequentist inference to exploit domain knowledge and empirical data [18].

This unification is vital for software-intensive systems, whose accurate modeling and verification depend on capturing complex interactions between heterogeneous stochastic sub-systems.

Key Interdependencies and System Dynamics

In multi-model stochastic systems, interdependencies define how different sub-models or system layers influence one another. The Interdependent Multi-layer Model (IMM) offers a conceptual structure for understanding these relationships, where an upper layer acts as a dependent variable and the layer beneath it serves as its set of independent variables [19]. This creates a nested, hierarchical system.

Types of Interdependencies

- Vertical Interdependency: This describes the functional relationship between different layers of a system, such as economic, socio-cultural, and physical layers in an international trade network [19]. A disruption in a lower layer (e.g., physical infrastructure) propagates upwards, affecting layers like economic output.

- Horizontal Interdependency: This occurs between models or components within the same layer. In Concurrent Stochastic Games (CSGs), multiple players or components with distinct objectives make concurrent, rational decisions, leading to complex interactions [20].

- Multi-Coalitional Verification: An extension beyond traditional two-coalition verification for CSGs, this involves analyzing equilibria among any number of distinct coalitions, where no coalition has an incentive to unilaterally change its strategy in any game state [20].

Cascading Effects and Resilience

A primary reason for modeling interdependencies is to understand the propagation of cascading effects, both positive and negative, through a system [19]. The resilience of such a multi-layer system—defined as its capacity to recover or renew after a shock—is critically dependent on the interactions between and within its layers [19].

Experimental Protocols and Verification Procedures

This section outlines detailed methodologies for analyzing and verifying multi-model stochastic systems, with a focus on the ULTIMATE framework and applications in multi-agent systems.

Protocol 1: ULTIMATE Framework Verification

Aim: To verify dependability and performance properties of a heterogeneous multi-model stochastic system using the ULTIMATE framework.

- Step 1: System Decomposition. Decompose the target system into constituent stochastic models (e.g., Discrete-Time Markov Chains, Continuous-Time Markov Chains, Markov Decision Processes, Stochastic Games).

- Step 2: Interdependency Mapping. Identify and formally specify the interdependencies between the models defined in Step 1. This includes data flow, shared variables, and triggering events.

- Step 3: Property Specification. Formally specify the system-level properties to be verified using appropriate temporal logics. The ULTIMATE framework supports the extended probabilistic alternating-time temporal logic with rewards (rPATL) for multi-coalitional properties [20].

- Step 4: Model Integration and Analysis. Utilize the ULTIMATE tool to integrate the models and their interdependencies. The framework's novel verification method will handle the complex interactions.

- Step 5: Synthesis (if required). Based on the verification results, synthesize optimal strategies for the system components (e.g., controllers for agents) that guarantee the satisfaction of the specified properties.

Protocol 2: Multi-Agent Path Execution (MAPE) Robustness Verification

Aim: To verify the reliability and robustness of pre-planned multi-agent paths under stochastic environmental uncertainties [21].

- Step 1: Preplanned Path Generation. Use a Multi-Agent Pathfinding (MAPF) algorithm, such as Conflict-Based Search (CBS), to generate a set of conflict-free paths for all agents [21].

- Step 2: Adjustment Solution Definition. Define an adjustment solution based on a set of constraint rules and a priority strategy to avoid conflicts and deadlocks during execution [21].

- Step 3: Markov Decision Process (MDP) Model Development. Develop a probabilistic MDP model by refining the pre-planned paths from Step 1. Integrate guard conditions derived from the constraint tree and the specific constraint rules from Step 2, applied before agents enter risk-prone locations [21].

- Step 4: Formal Property Specification. Specify reliability and robustness properties using Probabilistic Computation Tree Logic (PCTL). Example properties include "the probability that all agents reach their goals without deadlock is at least 0.95" or "the expected time to completion is less than 100 time units" [21].

- Step 5: Probabilistic Model Checking. Use a probabilistic model checker, such as PRISM, to verify the MDP model against the PCTL properties. This step quantitatively assesses the system's performance under uncertainty [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical workflow for the formal verification of a multi-model stochastic system, integrating protocols 1 and 2.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Toolkit for Stochastic System Verification

The following table details the essential computational tools and formalisms required for research in multi-model stochastic system verification.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Stochastic System Verification

| Tool/Formalism Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ULTIMATE Framework [18] | Integrated Software Framework | Supports representation, verification, and synthesis of heterogeneous multi-model stochastic systems with complex interdependencies. |

| PRISM / PRISM-Games [20] [21] | Probabilistic Model Checker | A tool for modeling and formally verifying systems that exhibit probabilistic and nondeterministic behavior (MDPs, CSGs) against PCTL/rPATL properties. |

| Markov Decision Process (MDP) [21] | Mathematical Model | Models systems with probabilistic transitions and nondeterministic choices; the basis for verification under uncertainty. |

| Concurrent Stochastic Game (CSG) [20] | Mathematical Model | Models interactions between multiple rational decision-makers with distinct objectives in a stochastic environment. |

| rPATL (Probabilistic ATL with Rewards) [20] | Temporal Logic | Specifies equilibria-based properties for multiple distinct coalitions in CSGs, including probability and reward constraints. |

| PCTL (Probabilistic CTL) [21] | Temporal Logic | Used to formally state probabilistic properties (e.g., "the probability of failure is below 1%") for Markov models. |

| Conflict-Based Search (CBS) [21] | Algorithm | A state-of-the-art MAPF algorithm for generating conflict-free paths for multiple agents, used as input for execution verification. |

Quantitative Data and Model Analysis

The application of these frameworks yields quantitative results that can be used to compare system configurations and evaluate performance.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Multi-Model Stochastic System Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Applicable Model / Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability Metrics | Probability of satisfying a temporal logic property (e.g., P≥0.95 [φ]) | MDPs, CSGs, Multi-model Systems [18] [21] | Quantifies the likelihood that a system satisfies a critical requirement, such as safety or liveness. |

| Reward/Cost Metrics | Expected cumulative reward (or cost) | MDPs, CSGs with reward structures [20] | Measures long-term average performance, such as expected time to completion or total energy consumption. |

| Equilibria Metrics | Social welfare / Social cost at Nash Equilibrium | Multi-coalitional CSGs [20] | The total combined value of all coalitions' objectives at a stable strategy profile. |

| Resilience Metrics | Speed of return to equilibrium after a shock | Interdependent Multi-Layer Models (IMM) [19] | In "engineering resilience," a faster return indicates higher resilience. |

| Ability to absorb shock and transition to new equilibria | Interdependent Multi-Layer Models (IMM) [19] | In "ecological resilience," a greater capacity to absorb disturbance indicates higher resilience. |

Advanced Application Note: Multi-Coalitional Agent Verification

Application: This protocol details the verification of systems where agents are partitioned into three or more distinct coalitions, each with independent objectives.

Background: Traditional verification for CSGs is often limited to two coalitions. Many practical applications, such as communication protocols with multiple stakeholders or multi-robot systems with mixed cooperative and competitive goals, require a multi-coalitional perspective [20].

Procedure:

- Model as a CSG: Formulate the system as a concurrent stochastic game with state space S, action sets for N players, a probabilistic transition function, and reward functions for each coalition.

- Coalition Partitioning: Partition the set of all players/agents into k distinct coalitions, C~1~, C~2~, ..., C~k~.

- Property Specification: Express the desired system behavior using an extension of rPATL that can reason about equilibria among the k coalitions. A typical property is of the form ⟨⟨C~1~, ..., C~k~⟩⟩~opt~ P~≥p~ [ψ], which queries whether the coalitions can adhere to a subgame-perfect social welfare optimal Nash equilibrium such that the probability of the path formula ψ being satisfied is at least p [20].

- Model Checking: Use an extended version of the PRISM-games tool to compute the equilibria and verify the specified property [20].

Visualization: The diagram below illustrates the model checking process for a multi-coalitional concurrent stochastic game.

Frameworks for Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) in Model Parameters

Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) provides a structured framework for understanding how variability and errors in model inputs propagate to affect model outputs, which is fundamental for developing trustworthy models in scientific and engineering applications [22]. For stochastic model verification procedures, UQ is indispensable as it quantifies the degree of trustworthiness of evidence-based explanations and predictions [23]. The integration of UQ is particularly crucial in high-stakes domains like drug development and healthcare, where decisions based on model predictions directly impact patient outcomes and resource allocation [22] [24]. This document outlines principal UQ frameworks and protocols applicable to parameter estimation in stochastic models, with emphasis on methods relevant to systems biology and drug discovery research.

The effectiveness of UQ methods varies significantly across applications, complexities, and model types. The table below summarizes performance characteristics of recently developed UQ frameworks based on empirical evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of UQ Frameworks

| Framework Name | Primary Application Domain | Reported Performance/Advantage | Method Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tether Benchmark [23] | Fundamental LLM UQ Tasks | ~70% on simple inequalities; ~33% (near random) on complex inequalities without guidance | Benchmarking |

| SurvUnc [24] | Survival Analysis | Superiority demonstrated on selective prediction, misprediction, and out-of-domain detection across 4 datasets | Meta-model (Post-hoc) |

| PINNs with Quantile Regression [25] | Systems Biology | Significantly superior efficacy in parameter estimation and UQ compared to Monte Carlo Dropout and Bayesian methods | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| ULTIMATE [18] [26] | Multi-Model Stochastic Systems | Effective verification of systems with probabilistic/nondeterministic uncertainty, discrete/continuous time, and partial observability | Probabilistic Model Checking |

| UNIQUE [27] | Molecular Property Prediction | Unified benchmarking of multiple UQ metrics; performance highly dependent on data splitting scenario | Benchmarking |

Table 2: Categorization of Uncertainty Sources in Model Parameters

| Uncertainty Type | Source Examples | Typical Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Aleatoric (Data-related) | Intrinsic/Extrinsic variability, Measurement error, Lack of knowledge [22] | Improved data collection, Error-in-variables models |

| Epistemic (Model-related) | Model discrepancy, Structural uncertainty, Simulator numerical error [22] | Model calibration, Multi-model inference, Bayesian updating |

| Coupling-related | Geometry uncertainty from medical image segmentation, Scale transition in multi-scale models [22] | Sensitivity analysis, Robust validation across scales |

UQ Framework Architectures and Methodologies

The ULTIMATE Framework for Multi-Model Stochastic Systems

The ULTIMATE framework addresses a critical gap in verifying complex systems that require the joint analysis of multiple interdependent stochastic models of different types [26]. Its architecture is designed to handle model interdependencies through a sophisticated verification engine.

Diagram: ULTIMATE Verification Workflow

The ULTIMATE verification engine processes two primary inputs: a multi-model comprising multiple interdependent stochastic models (e.g., DTMCs, CTMCs, MDPs, POMDPs), and a formally specified property for one of these models [26]. The framework then performs dependency analysis, synthesizes a sequence of analysis tasks, and executes these tasks using integrated probabilistic model checkers, numeric solvers, and inference engines [26]. This approach unifies the modeling of probabilistic and nondeterministic uncertainty, discrete and continuous time, partial observability, and leverages both Bayesian and frequentist inference [18].

PINNs with Quantile Regression for Systems Biology

A novel framework integrating Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) with quantile regression addresses parameter estimation and UQ in systems biology models, which are frequently described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [25]. This method utilizes a network architecture with multiple parallel outputs, each corresponding to a distinct quantile, facilitating comprehensive characterization of parameter estimation and its associated uncertainty [25].

Diagram: PINNs with Quantile Regression Architecture

This approach has demonstrated significantly superior efficacy in parameter estimation and UQ compared to alternative methods like Monte Carlo dropout and standard Bayesian methods, while maintaining moderate computational costs [25]. The integration of physical constraints directly into the learning objective ensures that parameter estimates remain consistent with known biological mechanisms.

SurvUnc for Survival Analysis

SurvUnc introduces a meta-model based framework for post-hoc uncertainty quantification in survival analysis, which predicts time-to-event probabilities from censored data [24]. This framework features an anchor-based learning strategy that integrates concordance knowledge into meta-model optimization, leveraging pairwise ranking performance to estimate uncertainty effectively [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for UQ Implementation

| Tool/Reagent | Function in UQ Protocol | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LM-Polygraph [28] | Implements >12 UQ and calibration algorithms; provides benchmarking framework | LLM uncertainty quantification |

| PRISM/Storm [26] | Probabilistic model checkers for analyzing Markov models | Stochastic system verification |

| ULTIMATE Tool [26] | Representation, verification and synthesis of multi-model stochastic systems | Complex interdependent systems |

| PINNs with Quantile Output [25] | Parameter estimation with comprehensive uncertainty characterization | Systems biology ODE models |

| SurvUnc Package [24] | Post-hoc UQ for any survival model without architectural modifications | Survival analysis in healthcare |

Experimental Protocols for UQ Evaluation

Protocol: UQ Benchmarking for Molecular Property Prediction

Purpose: To evaluate and compare UQ strategies in machine learning-based predictions of molecular properties, critical for drug discovery applications [27].

Materials:

- UNIQUE framework or equivalent benchmarking environment

- Molecular dataset with measured properties (e.g., IC50, solubility)

- Multiple UQ methods for comparison (e.g., ensemble methods, Bayesian neural networks, quantile regression)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Curate dataset of molecular structures and associated properties

- Implement multiple data splitting strategies (random, scaffold, temporal) to evaluate scenario-dependent UQ performance [27]

Model Training:

- Train base predictive models (e.g., Random Forest, GNN, Transformer) on training splits

- Apply UQ methods to generate uncertainty estimates alongside predictions

UQ Metric Calculation:

- Calculate standard UQ metrics including calibration curves, sharpness, and proper scoring rules

- Compute non-standard UQ metrics relevant to the application domain [27]

Performance Evaluation:

- Assess UQ method capability to identify poorly predicted compounds, particularly in regions of steep structure-activity relationships (SAR) [27]

- Compare methods across different data splitting scenarios to evaluate robustness

Interpretation:

- Note that UQ performance is highly dependent on the evaluation scenario, particularly the data splitting method [27]

- Recognize that several UQ methods struggle to identify poorly predicted compounds in regions of steep SAR

Protocol: Parameter Estimation and UQ in Systems Biology Models

Purpose: To estimate parameters and quantify their uncertainty in systems biology models described by ODEs using PINNs with quantile regression [25].

Materials:

- Observed time-series data for biological species (typically noisy and incomplete)

- ODE model representing the biological system

- PINN implementation with multiple quantile outputs

Procedure:

- Network Configuration:

- Implement a neural network with multiple parallel outputs, each corresponding to a distinct quantile (e.g., τ = 0.1, 0.5, 0.9)

- Incorporate ODE equations directly into the loss function as physics constraints [25]

Training:

- Minimize a composite loss function containing both data mismatch terms and physics residual terms

- Utilize adaptive training strategies to balance the contribution of different loss components

Parameter Estimation:

- Extract parameter values and their uncertainties from the trained network

- Use the median (τ = 0.5) estimates as the primary parameter values

- Utilize the spread between different quantiles to characterize parameter uncertainty

Validation:

- Compare parameter estimates and their uncertainties to those obtained through Bayesian methods and Monte Carlo dropout [25]

- Validate predictive uncertainty on held-out experimental data

Interpretation:

- This method has demonstrated superior efficacy in parameter estimation and UQ compared to Monte Carlo dropout and Bayesian methods at moderate computational cost [25]

Protocol: History-Matching for Data Worth Analysis

Purpose: To evaluate the value of existing or potential observation data for reducing forecast uncertainty in models [29].

Materials:

- Existing model with parameter sets

- Current and potential observation data

- Linear uncertainty analysis tools

Procedure:

- Base Uncertainty Calculation:

- Run history-matching to estimate model parameters

- Quantify the uncertainty of a key model forecast using the calibrated model [29]

Data Perturbation:

- Systematically add potential observation data or remove existing observation data

- Recalculate forecast uncertainty after each perturbation

Data Worth Quantification:

- Quantify the change in forecast uncertainty resulting from data changes

- Data that significantly reduces forecast uncertainty when added (or increases it when removed) has high worth [29]

Network Design:

- Use data worth analysis to inform the design of observation networks

- Prioritize monitoring locations that provide the greatest reduction in forecast uncertainty for critical model predictions

Implementing robust uncertainty quantification frameworks is essential for advancing stochastic model verification procedures, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development. The frameworks and protocols outlined here provide structured approaches for researchers to quantify, evaluate, and communicate uncertainty in model parameters. As these methods continue to evolve, their integration into standard research practice will enhance the reliability and trustworthiness of computational models in scientific discovery and decision-making.

Verification in Practice: Methods and Applications in Biomedical Research

Probabilistic and Parametric Model Checking Techniques

Probabilistic and parametric model checking represent advanced formal verification techniques for analyzing stochastic systems. Probabilistic model checking is a method for the formal verification of systems that exhibit probabilistic behavior, enabling the analysis of properties related to reliability, performance, and other non-functional characteristics specified in temporal logic [5]. Parametric model checking (PMC) extends this approach by computing algebraic formulae that express key system properties as rational functions of system and environment parameters, facilitating analysis of sensitivity and optimal configuration under varying conditions [30]. These techniques have evolved significantly from their initial applications in verifying randomized distributed algorithms to becoming valuable tools across diverse domains including communications, security, and pharmaceutical development [5] [31]. This document presents application notes and experimental protocols for employing these verification procedures within the context of stochastic model verification research, with particular attention to applications in drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Modeling Formalisms

Core Modeling Paradigms

Several probabilistic modeling formalisms support different aspects of system analysis. Discrete-time Markov Chains (DTMCs) model systems with discrete state transitions and probabilistic behavior, suitable for randomized algorithms and reliability analysis [5] [32]. Continuous-time Markov Chains (CTMCs) incorporate negative exponential distributions for transition delays, making them ideal for performance and dependability evaluation where timing characteristics are crucial [5]. Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) combine probabilistic transitions with nondeterministic choices, enabling modeling of systems with both stochastic behavior and controllable decisions, such as controller synthesis and security protocols with adversarial elements [5] [33].

The verification of these models employs temporal logics for property specification. PCTL (Probabilistic Computation Tree Logic) is used for DTMCs and MDPs to express probability-based temporal properties [5] [32]. CSL (Continuous Stochastic Logic) extends these capabilities to CTMCs for reasoning about systems with continuous timing [5]. For more complex requirements involving multiple objectives, multi-objective queries allow the specification of trade-offs between different goals, such as optimizing performance while minimizing resource consumption [33].

Parametric Extensions

Parametric model checking introduces parameters to transition probabilities and rewards in these models, enabling the analysis of how system properties depend on underlying uncertainties [30]. Recent advances like fast Parametric Model Checking (fPMC) address scalability limitations through model fragmentation techniques, partitioning complex Markov models into fragments whose reachability properties are analyzed independently [30]. For systems requiring multiple interdependent stochastic models of different types, frameworks like ULTIMATE support heterogeneous multi-model stochastic systems with complex interdependencies, unifying probabilistic and nondeterministic uncertainty, discrete and continuous time, and partial observability [18].

Application Notes

Domain Applications and Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Application Domains for Probabilistic and Parametric Model Checking

| Domain | Application Examples | Models Used | Properties Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Distributed Algorithms | Consensus protocols, leader election, self-stabilization [5] | DTMCs, MDPs | Correctness probability, worst-case runtime, expected termination time [5] |

| Communications and Networks | Bluetooth, FireWire, Zigbee protocols, wireless sensor networks [5] | DTMCs, MDPs, Probabilistic Timed Automata (PTAs) | Reliability, timeliness, collision probability, quality-of-service metrics [5] |

| Computer Security | Security protocols, adversarial analysis [5] | MDPs | Resilience to attack, probability of secret disclosure, worst-case adversarial behavior [5] |

| Drug Development (MID3) | Dose selection, trial design, special populations, label claims [31] | Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models, disease progression models | Probability of trial success, optimal dosing regimens, exposure-response relationships [31] |

| Software Performance Analysis | Quality properties of Java code, resource use, timing [34] | Parametric Markov chains | Performance properties, resource consumption, confidence intervals for quality metrics [34] |

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Verification Methods

| Method/Tool | Application Context | Accuracy/Performance Results | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROPER Method (point estimates, 10³ program log entries) | Software performance analysis of Java code [34] | Accurate within 7.9% of ground truth [34] | Under 15 ms analysis time [34] |

| PROPER Method (point estimates, 10⁴ program log entries) | Software performance analysis of Java code [34] | Accurate within 1.75% of ground truth [34] | Under 15 ms analysis time [34] |

| PROPER Method (confidence intervals) | Software performance analysis with uncertainty quantification [34] | All confidence intervals contained true property value [34] | 6.7-7.8 seconds on regular laptop [34] |

| fPMC | Parametric model checking through model fragmentation [30] | Effective for systems where standard PMC struggles [30] | Improved scalability for multi-parameter systems [30] |

| Symbolic Model Checking (using BDDs) | Randomized distributed algorithms, communication protocols [5] | Enabled analysis of models with >10¹⁰ states [5] | Handled state space explosion for regular models [5] |

Business Impact in Pharmaceutical Development

The application of modeling and verification techniques in pharmaceutical development, termed Model-Informed Drug Discovery and Development (MID3), has demonstrated significant business value. Companies like Pfizer reported reduction in annual clinical trial budget of $100 million and increased late-stage clinical study success rates through these approaches [31]. Merck & Co/MSD achieved cost savings of approximately $0.5 billion through MID3 impact on decision-making [31]. Regulatory agencies including the FDA and EMA have utilized MID3 analyses to support approval of unstudied dose regimens, provide confirmatory evidence of effectiveness, and enable extrapolation to special populations [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Parametric Model Checking via Model Fragmentation (fPMC)

Purpose: To efficiently compute parametric reachability probabilities for Markov models with complex behavior and multiple parameters through model fragmentation [30].

Materials and Methods:

- Input Requirements: Parametric Markov model (DTMC or MDP) with defined state space, transitions, and parameters; set of target states; parameter value ranges.

- Tools: fPMC tool implementation [30].

- Procedure:

- Model Partitioning: Decompose the input Markov model into fragments based on structural analysis.

- Fragment Analysis: Compute reachability probabilities for each fragment independently using parametric model checking.

- Result Combination: Combine fragment results using composition rules to obtain overall parametric reachability formula.

- Formula Simplification: Apply algebraic simplification to the combined parametric formula.

- Validation: Verify correctness through simulation or comparison with standard PMC where feasible.

Output Analysis: Parametric closed-form expressions for reachability probabilities; sensitivity analysis of parameters; evaluation of scalability compared to standard PMC.

Protocol for Software Performance Analysis with Confidence Intervals (PROPER Method)

Purpose: To formally analyze timing, resource use, cost and other quality aspects of computer programs using parametric Markov models synthesized from code with confidence intervals [34].

Materials and Methods:

- Input Requirements: Java source code; program execution logs; hardware platform specifications; performance property specifications.

- Tools: PROPER tool implementation; PRISM model checker or similar probabilistic verification tool [34].

- Procedure:

- Model Synthesis: Automatically generate parametric discrete-time Markov chain model from Java source code.

- Parameter Estimation: Calculate confidence intervals for model parameters using program log data and statistical methods.

- Formal Verification: Apply probabilistic model checking with confidence intervals to compute confidence bounds for performance properties.

- Validation: Compare point estimates with actual measurements when available; assess coverage probability of confidence intervals.

- Reuse Analysis: Utilize the synthesized parametric model to predict performance under different hardware platforms, libraries, or usage profiles.

Output Analysis: Confidence intervals for performance properties; point estimates when using large program logs; documentation of analysis accuracy and computational performance.

Protocol for Clinical Trial Simulation in Drug Development

Purpose: To assess the impact of trial design, conduct, analysis and decision making on trial performance metrics through simulation [35].

Materials and Methods:

- Input Requirements: Disease progression model; pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model; patient population model; dose-response relationships; trial design parameters.

- Tools: Clinical trial simulation software; statistical analysis packages; model-based drug development platforms.

- Procedure:

- Protocol Development: Create comprehensive simulation plan documenting data generation, analytical methods, and decision criteria.

- Virtual Population Generation: Simulate virtual patient populations with appropriate covariate distributions.

- Trial Execution Simulation: Implement trial design including randomization, dosing, visit schedules, and dropout mechanisms.

- Data Analysis: Apply statistical methods to simulated trial data according to pre-specified analysis plan.

- Decision Assessment: Evaluate decision criteria against trial performance metrics.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess robustness of conclusions to model assumptions and parameter uncertainty.

Output Analysis: Probability of trial success; optimal dose selection; power analysis; operating characteristics of design alternatives; documentation for regulatory submission [31] [35].

Visualization Diagrams

Model Fragmentation Workflow for fPMC

PROPER Method Analysis Workflow

Model Relationships in Probabilistic Verification

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Probabilistic Model Checking

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PRISM Model Checker [5] [32] | Probabilistic model checker supporting DTMCs, CTMCs, MDPs, and probabilistic timed automata | General-purpose verification of stochastic systems; educational use [5] [32] |

| Storm Model Checker [5] | High-performance probabilistic model checker optimized for efficient analysis | Large-scale industrial verification problems [5] |

| fPMC Tool [30] | Implementation of fast parametric model checking through model fragmentation | Parametric analysis of systems with multiple parameters where standard PMC struggles [30] |

| PROPER Tool [34] | Automated probabilistic model synthesis from Java source code with confidence intervals | Software performance analysis and quality property verification [34] |

| ULTIMATE Framework [18] | Verification and synthesis of heterogeneous multi-model stochastic systems | Complex systems requiring multiple interdependent stochastic models of different types [18] |

| Temporal Logics (PCTL, CSL) [5] [32] | Formal specification languages for probabilistic system properties | Expressing verification requirements for Markov models [5] [32] |

| Clinical Trial Simulation Software [31] [35] | MID3 implementation for pharmaceutical development | Dose selection, trial design optimization, and regulatory submission support [31] [35] |

Bayesian and Frequentist Inference for Parameter Estimation

Parameter estimation forms the critical bridge between theoretical stochastic models and their practical application in scientific research and drug development. The choice between Bayesian and Frequentist inference frameworks significantly influences how researchers quantify uncertainty, incorporate existing knowledge, and ultimately derive conclusions from experimental data. Within stochastic model verification procedures, this selection dictates the analytical pathway for confirming model validity and reliability.

The Bayesian framework treats parameters as random variables with probability distributions, systematically incorporating prior knowledge through Bayes' theorem to update beliefs as new data emerges [36]. In contrast, the Frequentist approach regards parameters as fixed but unknown quantities, relying on long-run frequency properties of estimators and tests without formal mechanisms for integrating external information [37]. This fundamental philosophical difference manifests in distinct computational requirements, interpretation of results, and applicability to various research scenarios encountered in verification procedures for stochastic systems.

Theoretical Foundations

Bayesian Inference Framework

Bayesian methods employ a probabilistic approach to parameter estimation that combines prior knowledge with experimental data using Bayes' theorem:

Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior

This framework generates full probability distributions for parameters rather than point estimates, enabling direct probability statements about parameter values [36]. The posterior distribution incorporates both the prior information and evidence from newly collected data, providing a natural mechanism for knowledge updating as additional information becomes available.

Key advantages of the Bayesian approach include its ability to formally incorporate credible prior data into the primary analysis, support probabilistic decision-making through direct probability statements, and adapt to accumulating evidence during trial monitoring [38]. These characteristics make Bayesian inference particularly valuable for complex stochastic models where prior information is reliable or data collection occurs sequentially.

Frequentist Inference Framework

Frequentist inference focuses on the long-run behavior of estimators and tests, operating under the assumption that parameters represent fixed but unknown quantities. This approach emphasizes point estimation, confidence intervals, and hypothesis testing based on the sampling distribution of statistics [37].

Frequentist methods typically calibrate stochastic models by optimizing a likelihood function or minimizing an objective function such as the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values [37]. Uncertainty quantification relies on asymptotic theory or resampling techniques like bootstrapping, with performance evaluated through repeated sampling properties such as type I error control and coverage probability.

The Frequentist framework provides well-established protocols for regulatory submissions and benefits from computational efficiency in many standard settings, particularly when historical data incorporation is not required or desired.

Comparative Theoretical Properties

Table 1: Theoretical Comparison of Inference Frameworks

| Property | Bayesian | Frequentist |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Interpretation | Random variables with distributions | Fixed unknown quantities |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Posterior credible intervals | Confidence intervals |

| Prior Information | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions | Not formally incorporated |

| Computational Demands | Often high (MCMC sampling) | Typically lower (optimization) |

| Result Interpretation | Direct probability statements about parameters | Long-run frequency properties |

| Sequential Analysis | Natural framework for updating | Requires adjustment for multiple looks |

| Small Sample Performance | Improved with informative priors | Relies on asymptotic approximations |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Bayesian Inference Workflow Protocol

Objective: Estimate parameters of a stochastic model using Bayesian inference with proper uncertainty quantification.

Materials and Reagents:

- Dataset comprising observed system outputs

- Specified probabilistic model (likelihood)

- Justified prior distributions for parameters

- Computational environment supporting MCMC sampling

Procedure:

Model Specification: Define the complete probabilistic model including:

- Likelihood function: ( p(D|\theta) ) where D represents data and θ represents parameters

- Prior distributions: ( p(\theta) ) for all parameters

- Hierarchical structure if applicable

Prior Selection: Justify prior choices based on:

- Historical data from previous studies

- Expert knowledge in the domain

- Non-informative priors when prior knowledge is limited

Posterior Computation: Implement sampling algorithm:

- Configure Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) parameters

- Run multiple chains with diverse initializations

- Set appropriate warm-up/adaptation periods

- Monitor convergence using Gelman-Rubin statistic (( \hat{R} )) [37]

Posterior Analysis: Extract meaningful inferences:

- Calculate posterior summaries (mean, median, quantiles)

- Examine marginal and joint posterior distributions

- Perform posterior predictive checks

- Evaluate model fit using appropriate diagnostics

Decision Making: Utilize posterior for scientific inferences:

- Compute probabilities of clinical significance

- Make predictions for future observations

- Compare competing models using Bayes factors or information criteria