Time Step Convergence Analysis in Agent-Based Models: A Framework for Credible Biomedical Simulation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to time step convergence analysis for Agent-Based Models (ABMs) in biomedical research and drug development.

Time Step Convergence Analysis in Agent-Based Models: A Framework for Credible Biomedical Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to time step convergence analysis for Agent-Based Models (ABMs) in biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational principles of numerical verification, methodological approaches for adaptive and multiscale ABMs, practical troubleshooting for non-convergence issues, and rigorous validation frameworks aligned with regulatory credibility standards. Aimed at researchers and scientists, the content synthesizes current best practices to ensure ABMs used in in silico trials and therapeutic development are both computationally robust and scientifically credible.

Why Time Step Convergence is Critical for Credible Agent-Based Models

Defining Time Step Convergence in the Context of ABM Verification

In the field of Agent-Based Modelling (ABM), verification is a critical process for ensuring that a computational model correctly implements its intended design and that simulation outputs are robust and reliable. A cornerstone of this process is Time Step Convergence Analysis (TSCA), a numerical verification procedure that assesses whether a model's outputs are unduly influenced by the discrete time-step length selected for its simulation [1]. For ABMs intended to inform decision-making in fields like drug development, establishing time step convergence provides essential evidence of a model's numerical correctness and robustness [1].

This document delineates the formal definition, mathematical foundation, and a detailed experimental protocol for performing TSCA, framing it within the broader context of mechanistic ABM verification for in-silico trials.

Mathematical Definition and Quantitative Framework

Time Step Convergence Analysis specifically aims to assure that the time approximation introduced by the Fixed Increment Time Advance (FITA) approach—used by most ABM frameworks—does not extensively influence the quality of the solution [1]. The core objective is to determine if the simulation results remain stable and consistent as the computational time step is refined.

The analysis quantifies the discretization error introduced by the chosen time step. For a given output quantity of interest, this error is calculated as the percentage difference between results obtained with a reference time step and those from a larger, candidate time step.

Quantitative Measure of Discretization Error The percentage discretization error for a specific time step is calculated using the following equation [1]:

eqi = (|qi* - qi| / |qi*|) * 100

i*is the smallest, computationally tractable reference time step.qi*is a reference output quantity (e.g., peak value, final value, or mean value) obtained from a simulation executed with the reference time stepi*.qiis the same output quantity obtained from a simulation executed with a larger time stepi(wherei > i*).eqiis the resulting percentage discretization error.

A common convergence criterion used in practice is that the model is considered converged if the error eqi is less than 5% for all key output quantities [1].

Table 1: Key Components of the Time Step Convergence Analysis Mathematical Framework

| Component | Symbol | Description | Considerations in ABM Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Time Step | i* |

The finest, computationally feasible time step used as a benchmark. | Must be small enough to be considered a "ground truth" but not so small that simulation runtime becomes prohibitive. |

| Candidate Time Step | i |

A larger time step whose error is being evaluated. | Often chosen as multiples of the reference time step (e.g., 2x, 5x, 10x). |

| Output Quantity | q |

A key model output used to measure convergence (e.g., final tumor size, peak concentration). | Must be a relevant, informative metric for the model's purpose. Multiple outputs should be tested. |

| Discretization Error | eqi |

The percentage error of the output at time step i compared to the reference. |

The 5% threshold is a common heuristic; stricter or more lenient thresholds can be defined based on model application. |

Experimental Protocol for Time Step Convergence Analysis

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for conducting a TSCA, adaptable to most ABM contexts.

The procedure for performing a time step convergence analysis follows a systematic workflow to ensure consistent and reproducible results.

Protocol Details

Step 1: Select Focal Output Quantities (q)

- Objective: Identify a limited set of critical output variables that are central to the model's research question and intended use.

- Procedure: Consult the model's conceptual framework and ODD (Overview, Design concepts, Details) protocol. Typical outputs include:

- Final system state: e.g., total number of cells at simulation end.

- Peak/Dynamic values: e.g., maximum concentration of a molecule, time-series of key metrics.

- Summary statistics: e.g., mean, variance, or spatial distribution of an agent property over time.

- Documentation: Record the chosen outputs and justify their selection based on the model's objectives.

Step 2: Determine the Reference Time Step (i*)

- Objective: Establish the smallest, computationally tractable time step to serve as the benchmark.

- Procedure:

- Start with a time step informed by the fastest dynamic process in the model (e.g., molecular binding rate, fastest agent decision cycle).

- Iteratively reduce the time step until further reduction leads to negligible changes in the focal outputs, while remaining mindful of computational constraints.

- The chosen

i*should be the smallest step that maintains feasible runtimes for multiple replications.

- Documentation: Report the final

i*value and the rationale for its selection.

Step 3: Define a Suite of Candidate Time Steps (i)

- Objective: Select a series of larger time steps for which the discretization error will be calculated.

- Procedure: Choose 3-5 candidate time steps that are multiples of the reference time step

i*(e.g.,2i*,5i*,10i*,20i*). This should include time steps typically used in similar models for comparison. - Documentation: List all candidate time steps to be tested.

Step 4: Execute Simulation Runs

- Objective: Generate output data for all selected time steps.

- Procedure:

- For the reference time step

i*and each candidate time stepi, run the simulation. - Hold all other parameters and model features constant. Use the same random seed across all runs to ensure deterministic comparability, isolating the effect of the time step [1] [2].

- Record the values for all focal outputs (

qi*andqi).

- For the reference time step

- Documentation: Note the simulation environment, software version, and random seed used to ensure replicability.

Step 5: Calculate Discretization Error

- Objective: Quantify the error associated with each candidate time step.

- Procedure: For each candidate time step

iand each focal outputq, calculate the percentage discretization error using the equation:eqi = (|qi* - qi| / |qi*|) * 100[1]. - Documentation: Compile the results in a table for clear comparison.

Table 2: Exemplar Time Step Convergence Analysis Results for a Hypothetical Tumor Growth ABM

| Time Step (i) | Final Tumor Cell Count (qi) | Discretization Error (eqi) | Peak Drug Concentration (qi) | Discretization Error (eqi) | Convergence Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 min (i*) | 10,250 (qi*) | Reference | 98.5 µM (qi*) | Reference | Reference |

| 0.6 min | 10,247 | 0.03% | 98.1 µM | 0.41% | Converged |

| 1.2 min | 10,230 | 0.20% | 97.5 µM | 1.02% | Converged |

| 6.0 min | 10,150 | 0.98% | 94.2 µM | 4.37% | Converged |

| 12.0 min | 9,950 | 2.93% | 89.1 µM | 9.54% | Not Converged |

Step 6: Apply Convergence Criterion and Interpret Results

- Objective: Determine if the model's outputs are acceptably stable across the tested time steps.

- Procedure:

- Apply a pre-defined error threshold (e.g.,

eqi < 5%) to the results for all key outputs [1]. - A time step

iis considered acceptable if the error for all focal outputs is below the threshold. - The largest time step that meets this criterion is often selected for future experiments to optimize computational efficiency.

- Apply a pre-defined error threshold (e.g.,

- Interpretation: Failure to converge within reasonable time steps may indicate that the model contains dynamics that are too fast for a FITA approach, potentially requiring a different simulation algorithm or model refinement.

Step 7: Documentation and Reporting

- Objective: Ensure the analysis is transparent, reproducible, and can be included as part of model verification for regulatory submissions.

- Procedure: Report all elements from the previous steps: focal outputs, reference and candidate time steps, simulation setup, raw results, error calculations, and the final convergence conclusion.

Successfully conducting TSCA and broader ABM verification requires a suite of computational tools and conceptual frameworks.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ABM Verification and TSCA

| Tool Category | Specific Examples / Functions | Role in TSCA and ABM Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Verification Software | Model Verification Tools (MVT): An open-source tool suite for deterministic and stochastic verification of discrete-time models [1]. | Automates steps like TSCA, uniqueness analysis, and parameter sweep analysis, streamlining the verification workflow. |

| ABM Platforms | NetLogo: A "low-threshold, high-ceiling" environment with high-level primitives for rapid ABM prototyping and visualization [3]. Custom C++/Python Frameworks: (e.g., PhysiCell, OpenABM) offer flexibility for complex, high-performance models [4]. | Provide the environment to implement the model and adjust the time step parameter for conducting TSCA. |

| Sensitivity & Uncertainty Analysis Libraries | SALib (Python) for Sobol analysis [1]. Pingouin/Scikit/Scipy for LHS-PRCC analysis [1]. | Used in conjunction with TSCA for parameter sweep analysis to ensure the model is not ill-conditioned. |

| Conceptual Frameworks | VV&UQ (Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification): An ASME standard adaptable for in-silico trial credibility assessment [1]. ODD Protocol: A standard for describing ABMs to ensure transparency and replicability [2]. | Provides the overarching methodological structure and reporting standards that mandate and guide TSCA. |

Time Step Convergence Analysis is a non-negotiable component of the verification process for rigorous Agent-Based Models, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development. By systematically quantifying the discretization error associated with the simulation's time step, researchers can substantiate the numerical robustness of their findings. The protocol outlined herein provides a concrete, actionable roadmap for integrating TSCA into the ABM development lifecycle, thereby strengthening the credibility of models intended to generate evidence for regulatory evaluation and scientific discovery.

The Impact of Numerical Errors on Predictive Outcomes in Biomedical ABMs

Agent-based models (ABMs) are a powerful class of computational models that simulate complex systems through the interactions of autonomous agents. In biomedical research, they are increasingly used to simulate multiscale phenomena, from cellular dynamics to population-level epidemiology [5] [6]. However, the predictive utility of these models is critically dependent on their numerical accuracy and credibility. One of the most significant, yet often overlooked, challenges is the impact of numerical errors introduced during the simulation process, particularly those related to time integration and solution verification [7]. Without rigorous assessment and control of these errors, ABM predictions can diverge from real-world behavior, leading to flawed biological interpretations and unreliable therapeutic insights. This application note examines the sources and consequences of numerical errors in biomedical ABMs and provides detailed protocols for their quantification and mitigation, framed within the context of time step convergence analysis.

Foundations of Numerical Errors in ABM Simulation

In computational modeling, numerical errors are discrepancies between the true mathematical solution of the model's equations and the solution actually produced by the simulation. For ABMs, which often involve discrete, stochastic, and multi-scale interactions, these errors can be particularly insidious. The primary sources of error include:

- Temporal Discretization Error: Arises from approximating continuous-time processes with discrete time steps. This is a form of truncation error and is a function of the time step size (∆t). Excessively large time steps can destabilize a simulation and invalidate results [8].

- Spatial Discretization Error: Occurs in ABMs with continuous spatial coordinates or those coupled with continuum fields (e.g., diffusing chemokines). The choice of spatial grid resolution or agent movement rules can introduce inaccuracies.

- Stochastic Error: Stemming from the inherent randomness in agent behaviors and interactions. While fundamental to many ABMs, the finite number of stochastic realizations leads to statistical uncertainty in the output.

- Round-off Error: Caused by the finite precision of floating-point arithmetic in computers. This is typically less significant than other error types but can accumulate in long-running simulations.

The Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) framework is essential for establishing model credibility. Verification is the process of ensuring the computational model correctly solves the underlying mathematical model, addressing the numerical errors described above. In contrast, validation determines how well the mathematical model represents reality [7]. This note focuses primarily on verification.

The Critical Role of Time Step Selection

The time step (∆t) is a pivotal parameter controlling the trade-off between simulation accuracy and computational cost. Traditional numerical integrators for differential equations (e.g., Euler, Runge-Kutta) require small time steps to maintain stability and accuracy, especially when simulating phenomena with widely different time scales, such as in molecular dynamics or rapid cellular signaling events [9].

Modern approaches are exploring machine learning to learn structure-preserving maps that allow for longer time steps. However, methods that do not preserve the geometric structure of the underlying Hamiltonian flow can introduce pathological behaviors, such as a lack of energy conservation and loss of equipartition between different degrees of freedom in a system [9]. This highlights that time step selection is not merely a numerical concern but one of fundamental physical and biological fidelity.

Quantifying Numerical Errors: A Verification Framework

A systematic approach to solution verification is necessary to quantify numerical approximation errors in ABMs. Curreli et al. (2021) propose a general verification framework consisting of two sequential studies [7].

Deterministic Model Verification

This first step aims to isolate and quantify errors from temporal and spatial discretization by eliminating stochasticity.

- Objective: To evaluate the order of accuracy of the numerical method and identify a range of potentially suitable time steps.

- Protocol:

- Parameter Selection: Identify a set of QoIs that are representative of the model's purpose (e.g., tumor cell count, cytokine concentration).

- Stochastic Control: Temporarily disable all stochastic elements in the model, fixing random seeds or replacing probabilistic rules with deterministic ones.

- Mesh Refinement: For spatially explicit models, perform a mesh refinement study to ensure spatial discretization error is minimized relative to temporal error [8].

- Temporal Convergence: Execute the deterministic model with a sequence of progressively smaller time steps (e.g., ∆t, ∆t/2, ∆t/4, ...). A common strategy is to use a constant refinement ratio (r) greater than 1.2.

- Error Calculation: Treat the solution from the finest time step as the "reference" or "exact" solution. For each QoI (φ), calculate the error (ε) for each time step (∆t) as the difference from the reference solution (φ_ref), often using a norm like L2 or L∞.

- Order of Accuracy: The observed order of accuracy (p) can be estimated from the slope of the error versus time step size on a log-log plot. If the numerical method is designed to be p-th order accurate, the results should converge at this rate.

Stochastic Model Verification

Once a suitable time step is identified from the deterministic study, this step quantifies the impact of the stochastic elements.

- Objective: To ensure that the statistical uncertainty due to stochasticity is sufficiently small, or at least quantified, for the chosen time step.

- Protocol:

- Re-enable Stochasticity: Restore all probabilistic rules and random components to the model.

- Ensemble Simulation: For the time step(s) identified in the deterministic study, run a large ensemble (N ≥ 100) of simulations with different random number generator seeds.

- Statistical Analysis: For each QoI, calculate the mean and variance across the ensemble at key time points. The standard error of the mean (SEM = σ/√N) indicates the precision of the estimated mean due to finite sampling.

- Error Budgeting: The total error in any single stochastic realization is a combination of the numerical discretization error (from the deterministic study) and the statistical error. The goal is to ensure that the discretization error is a small fraction of the statistical variance or the effect size of interest.

Table 1: Key Quantities of Interest (QoIs) for Error Analysis in Biomedical ABMs

| Biological Scale | Example Quantities of Interest (QoIs) | Relevant Error Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Subcellular / Molecular | Protein concentration, metabolic reaction rates | L2 norm of error, relative error |

| Cellular | Cell count, division rate, apoptosis rate, migration speed | Absolute error, coefficient of variation |

| Tissue / Organ | Tumor volume, vascular density, spatial gradient of biomarkers | Spatial norms, shape metrics (e.g., fractal dimension) |

| Population / Organism | Total tumor burden, disease survival time, drug plasma concentration | Statistical mean and variance, confidence intervals |

Table 2: Summary of Verification Studies and Their Outputs

| Study Type | Primary Objective | Key Inputs | Key Outputs | Success Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic Verification | Quantify discretization error | Sequence of decreasing time steps (∆t) | Observed order of convergence (p), error vs. ∆t plot | Error decreases systematically with ∆t at expected rate p. |

| Stochastic Verification | Quantify statistical uncertainty | Ensemble size (N), fixed ∆t | Mean and variance of QoIs, standard error of the mean (SEM) | SEM is acceptably small for the intended application. |

Experimental Protocols for Time Step Convergence Analysis

Protocol 1: Baseline Convergence Analysis

This protocol outlines the core procedure for performing a time step convergence analysis on an existing biomedical ABM.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- A fully implemented biomedical ABM (e.g., a model of tumor-immune interactions or tissue development).

- High-performance computing (HPC) resources for ensemble runs.

- Data analysis environment (e.g., Python/R with libraries for statistical analysis and plotting).

- Solver Configuration: Access to the solver's time-stepping parameters (e.g., BDF or Generalized alpha methods in COMSOL) and relative tolerance settings [8].

Methodology:

- QoI Selection: Define 3-5 key QoIs that represent the primary outputs of your biological study.

- Deterministic Verification: a. Disable stochastic rules in the model. b. Run the simulation with a coarse time step (∆tcoarse) over the entire biological time of interest (T). c. Repeat the simulation, successively halving the time step (∆tcoarse/2, ∆t_coarse/4, ...) until the changes in the QoIs become negligible. The finest time step solution serves as the reference. d. For each time step, calculate the error norm for each QoI relative to the reference.

- Stochastic Verification: a. Re-enable stochasticity. b. Select a candidate time step from the deterministic study (e.g., the largest step where error was below a 5% threshold). c. Perform an ensemble of at least 100 simulations with different random seeds. d. Calculate the mean trajectory and variance for each QoI across the ensemble.

- Analysis and Interpretation: a. Generate a convergence plot (log(Error) vs. log(∆t)) to visually confirm the order of accuracy. b. If the error does not decrease systematically, the model may have a coding error, or the chosen time step may be outside the asymptotic convergence range. c. Decide on the final time step by balancing the acceptable error level from the deterministic study with the computational cost of the ensemble runs required for the stochastic study.

Protocol 2: Advanced Structure-Preserving Integration

For ABMs that simulate mechanical or Hamiltonian systems (e.g., molecular dynamics, biomechanical interactions), using structure-preserving integrators can allow for larger time steps without sacrificing physical fidelity.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- ABM with a well-defined Hamiltonian or Lagrangian structure.

- Machine Learning frameworks (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) for implementing learned integrators.

- Training data consisting of high-fidelity, short-time-scale trajectories.

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: Define the system in terms of its Hamiltonian (H(p,q)) or its mechanical action.

- Generator Selection: Choose a generating function parametrization (e.g., the symmetric S³(𝑝̄,𝑞̄) form), which naturally leads to time-reversible and symplectic maps [9].

- Model Training: a. Use a neural network to represent the generating function. b. Train the network on data from short, high-accuracy simulations to learn the system's action. c. The loss function should penalize deviations from Hamilton's equations or a lack of symplecticity.

- Validation: a. Test the trained integrator on long-time-scale predictions not seen during training. b. Monitor conserved quantities (e.g., energy, momentum) to ensure the structure-preserving properties are functioning correctly. c. Compare the trajectories and final state QoIs against those generated by a high-accuracy conventional integrator with a very small time step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and "Reagents" for ABM Verification

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Dependent Solver (BDF/Generalized alpha) | Provides implicit time-stepping methods for stiff systems (e.g., diffusion-reaction). | Protocol 1: Core solver for performing convergence analysis [8]. |

| Events Interface | Handles instantaneous changes in model conditions (e.g., drug dose administration). | Prevents solver convergence issues and ensures accurate capture of step changes [8]. |

| Relative Tolerance Parameter | Controls the error tolerance for adaptive time-stepping solvers. | Tuning this parameter is part of the tolerance refinement study in convergence analysis [8]. |

| Generating Function (S³) | A scalar function that parametrizes a symplectic and time-reversible map. | Protocol 2: Core component for building a structure-preserving ML integrator [9]. |

| Expectation-Maximization Algorithm | A probabilistic method for finding maximum likelihood estimates of latent variables. | Useful for calibrating ABM parameters or estimating latent micro-variables from data, complementing verification [10]. |

| Ensemble Simulation Workflow | A scripted pipeline to launch and aggregate results from many stochastic runs. | Protocol 1: Essential for performing the stochastic verification study. |

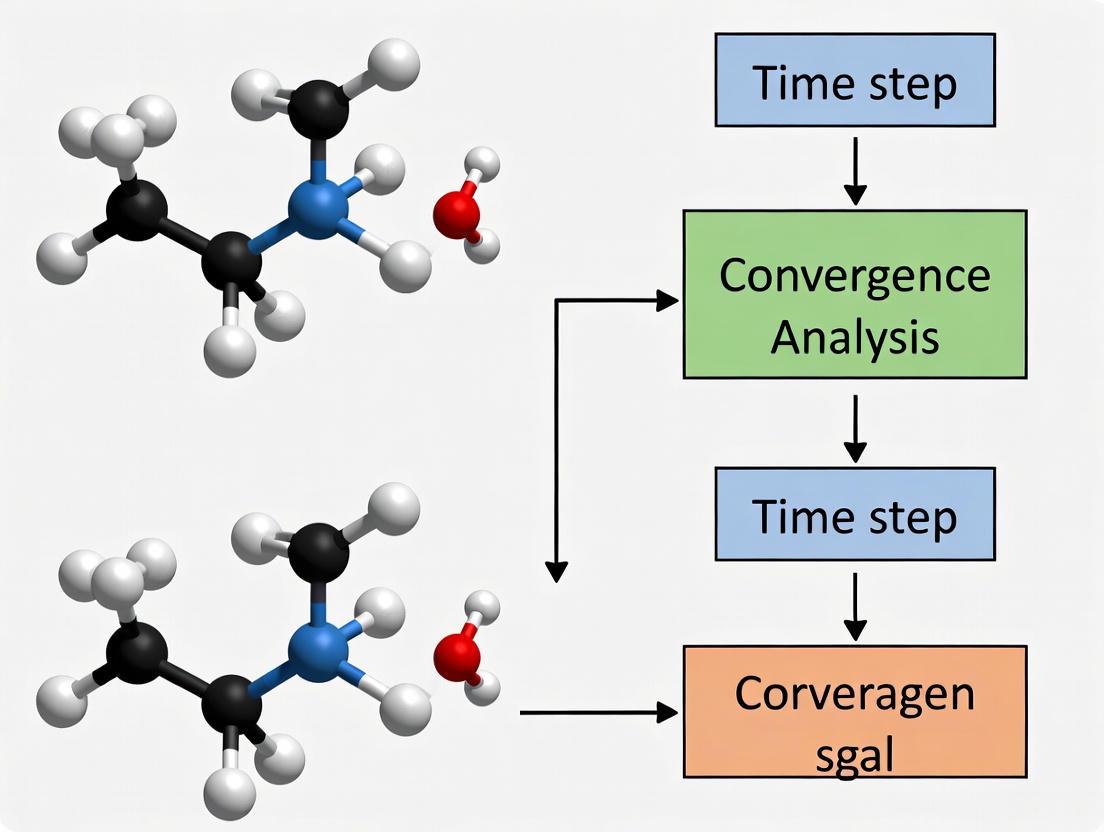

Workflow Visualization

Distinguishing Deterministic and Stochastic Verification for ABMs

Verification is a critical step in establishing the credibility of Agent-Based Models (ABMs), especially when they are used in mission-critical scenarios such as in silico trials for medicinal products [1] [11]. The process ensures that the computational model is implemented correctly and behaves as intended, providing confidence in its predictions. For ABMs, verification is uniquely challenging due to their hybrid nature, often combining deterministic rules with stochastic elements to simulate complex, emergent phenomena [11]. This document provides a detailed framework for distinguishing between and applying deterministic and stochastic verification methods within the specific context of time step convergence analysis in ABM research.

The core distinction lies in the treatment of randomness. Deterministic verification assesses the model's behavior under controlled conditions where all random seeds are fixed, ensuring numerical robustness and algorithmic correctness. In contrast, stochastic verification evaluates the model's behavior across the inherent randomness introduced by pseudo-random number generators, ensuring statistical reliability and consistency of outcomes [1] [11]. For ABMs used in biomedical research, such as simulating immune system responses or disease progression, both verification types are essential for regulatory acceptance [1].

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Core Concepts in ABM Verification

Agent-Based Models are a class of computational models that simulate the actions and interactions of autonomous entities (agents) to understand the emergence of system-level behavior from individual-level rules [12] [13]. Their verification involves two complementary processes:

- Deterministic Verification: This process aims to identify, quantify, and reduce numerical errors associated with the model's implementation when all stochastic elements are controlled. It assumes that with identical inputs and random seeds, the model will produce identical outputs. The primary focus is on assessing the impact of numerical approximations, such as time discretization, and ensuring the model does not exhibit ill-conditioned behavior [1] [11].

- Stochastic Verification: This process addresses the model's behavior when its inherent stochasticity is active. It evaluates the consistency and reliability of results generated across different random seeds and ensures that the sample size of stochastic simulations is sufficient to characterize the model's output distribution reliably [1] [14].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these verification types and their key components.

The Role of Time Step Convergence Analysis

Time step convergence analysis is a cornerstone of deterministic verification for ABMs that use a Fixed Increment Time Advance (FITA) approach [1]. Since ABMs often lack a formal mathematical foundation in differential equations, verifying that the model's outputs are not overly sensitive to the chosen time-step length is crucial. This analysis ensures that the discretization error introduced by the time-step is acceptable and that the model's dynamics are stable and reliable for the chosen step size. It provides a foundation for confidence in temporal simulations, particularly for models of biological processes where timing can critically influence emergent outcomes.

Deterministic Verification Protocols

Existence and Uniqueness Analysis

Aim: To verify that the model produces an output for all valid inputs and that identical inputs yield identical outputs within an acceptable tolerance for numerical rounding errors [1].

Protocol:

- Define Input Ranges: Establish the physiologically or theoretically plausible ranges for all model input parameters.

- Test Input Combinations: Systematically execute the model across the defined input space, including boundary values, to ensure a solution is generated for every combination. Models should not crash or hang.

- Uniqueness Testing: For a fixed random seed, run multiple identical simulations with the same input parameter set.

- Quantify Variation: Measure the variation in key output quantities across these identical runs. The variation should be minimal, attributable only to the finite precision of floating-point arithmetic.

- Set Tolerance: Establish a tolerance level for maximum permitted variation (e.g., machine precision) to pass the uniqueness test.

Time Step Convergence Analysis

Aim: To assure that the time approximation introduced by the FITA approach does not extensively influence the quality of the solution [1].

Protocol:

- Select Reference Outputs: Choose one or more key output quantities (QoIs) for analysis (e.g., peak value, final value, or mean value over time).

- Define Time Steps: Select a series of time-step lengths (∆t) for testing. This should include a reference time-step (∆t*) that is the smallest computationally tractable step.

- Run Simulations: Execute the model with a fixed random seed for each time-step in the series.

- Calculate Discretization Error: For each QoI and each time-step, compute the percentage discretization error using the formula: eq_i = |(QoI_i - QoIi) / QoIi| × 100 where QoI_i* is the value at the reference time-step ∆t*, and QoI_i is the value at the larger time-step ∆t.

- Assess Convergence: A model is considered converged if the error eq_i for all QoIs falls below a predetermined threshold (e.g., 5% as used in prior studies [1]) for a chosen operational time-step.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Deterministic Verification

| Verification Step | Quantitative Metric | Target Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Step Convergence | Percentage Discretization Error (eq_i) | < 5% [1] | Error due to time-step choice is acceptable |

| Smoothness Analysis | Coefficient of Variation (D) | Lower is better | High D indicates risk of stiffness or discontinuities |

| Uniqueness | Output variance across identical runs | Near machine precision | Model is deterministic at the code level |

Smoothness Analysis

Aim: To identify potential numerical errors leading to singularities, discontinuities, or buckling in the output time series [1].

Protocol:

- Generate Output Time Series: Run the model and record the time series for relevant output variables.

- Apply Moving Window: For each time point in the series, select a window of k nearest neighbors (e.g., k=3 [1]).

- Compute First Difference: Calculate the first difference of the time series within each window.

- Calculate Coefficient of Variation (D): Compute the standard deviation of the first difference and scale it by the absolute value of its mean. The formula for a window is effectively: D = σ(Δy) / |μ(Δy)|.

- Interpret Results: A high value of D indicates a non-smooth output, suggesting potential numerical instability, stiffness, or unintended discontinuities in the model logic.

Parameter Sweep and Sensitivity Analysis

Aim: To ensure the model is not numerically ill-conditioned and to identify parameters to which the output is abnormally sensitive [1].

Protocol:

- Define Parameter Space: Identify all input parameters and their plausible ranges.

- Sample Parameter Space: Use sampling techniques such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to efficiently explore the multi-dimensional input space.

- Execute Simulations: Run the model for each sampled parameter set.

- Check for Failures: Identify any parameter combinations for which the model fails to produce a valid output.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate Partial Rank Correlation Coefficients (PRCC) between input parameters and output values. This identifies parameters with significant influence on outputs, independent of other parameters, and is suitable for non-linear but monotonic relationships [1].

Stochastic Verification Protocols

Consistency and Sample Size Analysis

Aim: To verify that the stochastic model produces consistent and reliable results across different random seeds and that a sufficient number of simulation replicates are used to characterize the output distribution [1].

Protocol:

- Define Stochastic Outputs: Identify the key output variables of interest that are subject to stochasticity.

- Run Multi-Seed Replicates: Execute the model N times, each time with a different random seed, while holding all input parameters constant.

- Analyze Output Distribution: For each output variable, calculate descriptive statistics (mean, variance, confidence intervals) and visualize the distribution.

- Determine Sample Size: Assess the stability of the mean and variance estimates as N increases. The sufficient sample size is reached when these estimates stabilize within an acceptable confidence level. Techniques like bootstrapping can be used for this assessment.

Simulation-Based Calibration (SBC)

Aim: To verify the correctness of the calibration process itself within a Bayesian inference framework, isolating calibration errors from model structural errors [14].

Protocol:

- Draw from Prior: Draw a parameter set θ̃ from the defined prior distribution p(θ).

- Generate Synthetic Data: Run the stochastic model using θ̃ to generate a synthetic dataset ỹ.

- Perform Bayesian Inference: Use a calibration method (e.g., MCMC, ABC) to infer the posterior distribution p(θ|ỹ) given the synthetic data ỹ.

- Draw Posterior Samples: Draw L samples {θ_1, ..., θ_L} from the inferred posterior.

- Calculate Rank Statistic: Determine the rank of the true parameter θ̃ with respect to the posterior samples.

- Repeat and Check Uniformity: Repeat steps 1-5 a large number of times (n). If the calibration is well-calibrated, the ranks of the true parameters will be uniformly distributed across the (L+1) possible rank values [14].

The workflow for this powerful calibration verification method is outlined below.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Stochastic Verification

| Verification Step | Quantitative Metric | Target Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Variance of outputs across seeds | Stable mean and variance | Model stochasticity is well-behaved |

| Sample Size | Convergence of output statistics | Stable estimates with increasing N | Sufficient replicates for reliable inference |

| Simulation-Based Calibration | Distribution of rank statistics | Uniform distribution | Bayesian inference process is well-calibrated [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ABM Verification

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Verification | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Verification Tools (MVT) [1] | Software Suite | Provides integrated tools for deterministic verification steps (existence, time-step convergence, smoothness, parameter sweep). | Automated calculation of discretization error and smoothness coefficient. |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [1] | Sampling Algorithm | Efficiently explores high-dimensional input parameter spaces for sensitivity analysis. | Generating input parameter sets for PRCC analysis. |

| Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) [1] | Statistical Metric | Quantifies monotonic, non-linear relationships between inputs and outputs, controlling for other parameters. | Identifying key model drivers during parameter sweep analysis. |

| Sobol Sensitivity Analysis [1] | Statistical Metric | Variance-based sensitivity analysis to apportion output uncertainty to input parameters. | Global sensitivity analysis for complex, non-additive models. |

| Simulation-Based Calibration (SBC) [14] | Bayesian Protocol | Verifies the statistical correctness of a model calibration process using synthetic data. | Checking the performance of MCMC sampling for an ABM of disease spread. |

| Pseudo-Random Number Generators [11] | Algorithm | Generate reproducible sequences of random numbers. Implements stochasticity in the model. | Controlling stochastic elements (e.g., agent initialization, interactions) using seeds. |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

To comprehensively verify an ABM, deterministic and stochastic protocols should be executed in a logical sequence. The following integrated workflow is recommended for a robust verification process, particularly within time step convergence studies:

Phase 1: Foundational Deterministic Checks

- Begin with Existence and Uniqueness Analysis to ensure basic model stability and determinism with a fixed seed.

- Perform Time Step Convergence Analysis to establish a numerically stable time-step for all subsequent analyses.

- Conduct Smoothness Analysis on outputs generated with the converged time-step to check for numerical artifacts.

Phase 2: System Exploration

- Execute Parameter Sweep Analysis using LHS and PRCC to understand model sensitivity and identify critical parameters. This should be done with a fixed random seed for deterministic interpretation.

Phase 3: Stochastic Reliability Assessment

- With the critical parameters and stable time-step identified, perform Consistency and Sample Size Analysis by running the model with multiple random seeds.

- If the model is calibrated using Bayesian methods, perform Simulation-Based Calibration with synthetic data to verify the calibration pipeline.

This workflow ensures that the model is numerically sound before its stochastic properties are fully investigated, providing a structured path to credibility for ABMs in biomedical research and drug development.

For computational models, particularly Agent-Based Models (ABMs) used in mission-critical scenarios like drug development and in silico trials, establishing credibility is a fundamental requirement [11]. Model credibility assessment is a multi-faceted process, and solution verification serves as one of its critical technical pillars. This process specifically aims to identify, quantify, and reduce the numerical approximation error associated with a model's computational solution [11]. In the context of ABMs, which are inherently complex and often stochastic, formally linking solution verification to the broader credibility framework is essential for demonstrating that a model's outputs are reliable and fit for their intended purpose, such as supporting regulatory decisions [15] [11].

This document details application notes and protocols for integrating rigorous solution verification, with a specific focus on time step convergence analysis, into the credibility assessment of ABMs for biomedical research.

The Role of Solution Verification in Credibility Assessment

Solution verification provides the foundational evidence that a computational model is solved correctly and with known numerical accuracy. For a credibility framework, it answers the critical question: "Did we solve the equations (or rules) right?" [11]. This is distinct from validation, which addresses whether the right equations (or rules) were solved to begin with.

Regulatory guidance, such as that from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), emphasizes the need for an agile, risk-based framework that promotes innovation while ensuring robust scientific standards [15]. The FDA's draft guidance on AI in drug development highlights the importance of ensuring model credibility—trust in the performance of a model for a particular context of use [15]. Solution verification is a direct contributor to this trust, as it quantifies the numerical errors that could otherwise undermine the model's predictive value.

For ABMs, this is particularly crucial. The global behavior of these systems emerges from the interactions of discrete autonomous agents, and their intrinsic randomness introduces stochastic variables that must be carefully managed during verification [11]. A lack of rigorous verification can lead to pathological behaviors, such as non-conservation of energy in physical systems or loss of statistical equipartition, which hamper their use for rigorous scientific applications [9].

Quantitative Framework for Solution Verification

A comprehensive solution verification framework for ABMs should systematically quantify errors from both deterministic and stochastic aspects of the model [11]. The table below outlines key metrics and their targets for a credible ABM.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for ABM Solution Verification

| Verification Aspect | Metric | Target / Acceptance Criterion | Relation to Credibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Convergence | Time Step Sensitivity (e.g., key output change with step refinement) | < 2% change in key outputs over a defined range | Ensures numerical stability and independence of results from solver discretization [8]. |

| Stochastic Convergence | Variance of Key Outputs across Random Seeds | Coefficient of Variation (CV) < 5% for core metrics | Demonstrates that results are robust to the model's inherent randomness [11]. |

| Numerical Error | Relative Error (vs. analytical or fine-grid solution) | < 1% for major system-level quantities | Quantifies the inherent approximation error of the computational method [11]. |

| Solver Performance | Solver Relative Tolerance | Passes tolerance refinement study (e.g., tightened until output change is negligible) | Confirms that the solver's internal error control is sufficient for the problem [8]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequential process of integrating these verification activities into a model's credibility assessment plan.

Application Note: Time Step Convergence in a Biomedical ABM

Case Study: UISS-TB Model Verification

The Universal Immune System Simulator for Tuberculosis (UISS-TB) is an ABM of the human immune system used to predict the progression of pulmonary tuberculosis and evaluate therapies in silico [11]. Its credibility is paramount for potential use in in silico trials. The model involves interactions between autonomous entities (pathogens, cells, molecules) within a spatial domain, with stochasticity introduced via three distinct random seeds (RS) for initial distribution, environmental factors, and HLA types [11].

Table 2: Input Features for the UISS-TB Agent-Based Model [11]

| Input Feature | Description | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

Mtb_Sputum |

Bacterial load in the sputum smear (CFU/ml) | 0 | 10,000 |

Th1 |

CD4 T cell type 1 (cells/µl) | 0 | 100 |

TC |

CD8 T cell (cells/µl) | 0 | 1134 |

IL-2 |

Interleukin 2 (pg/ml) | 0 | 894 |

IFN-g |

Interferon gamma (pg/ml) | 0 | 432 |

Patient_Age |

Age of the patient (years) | 18 | 65 |

Time Step Convergence Protocol

Objective: To determine a computationally efficient yet numerically stable time step for the UISS-TB model by ensuring key outputs have converged.

Workflow:

Selection of Outputs: Identify a suite of critical outputs that represent the model's core dynamics. For UISS-TB, this includes:

- Total bacterial load

- Concentration of key immune cells (e.g., T-cells, Macrophages)

- Level of critical cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-10)

Parameterization: Configure the model for a representative baseline scenario using a standard set of input features (Table 2).

Execution: Run the model multiple times, varying only the computational time step (

Δt). A suggested range is from a very fine step (e.g.,Δt₀) to progressively larger steps (e.g.,2Δt₀,4Δt₀,8Δt₀). To account for stochasticity, each time step configuration must be run with multiple random seeds (e.g., n=50).Analysis: For each key output, plot its final value (or a relevant time-averaged value) against the time step size. The converged time step is identified as the point beyond which further refinement does not cause a statistically significant change in the output (e.g., < 2% change from the value at the finest time step).

The diagram below maps this analytical process.

Experimental Protocols for Credibility Assessment

Protocol: Deterministic Verification of ABMs

This protocol assesses the numerical accuracy of the model's deterministic core [11].

- Fix Random Seeds: Set all random seeds to a fixed value to eliminate stochastic variation.

- Mesh Refinement Study: If the model has a spatial component, perform a mesh refinement study to ensure solutions are independent of spatial discretization [8].

- Tolerance Refinement: Tighten the solver's relative tolerance (e.g., from

1e-3to1e-5) and run the model. A credible model will show negligible changes in key outputs when the tolerance is tightened beyond a certain point [8]. - Time Step Convergence: Follow the Time Step Convergence Protocol detailed in Section 4.2.

Protocol: Stochastic Verification of ABMs

This protocol quantifies the uncertainty introduced by the model's stochastic elements [11].

- Define Sample Size: Determine the number of replicates (

N) required for statistically robust results. This can be estimated by running a pilot study and calculating the coefficient of variation for key outputs. - Execute Replicates: Run the model

Ntimes, each with a different, independent random seed. - Analyze Variance: For each key output, calculate the mean, standard deviation, and variance across the

Nreplicates. - Assess Distribution: Check that the distribution of outputs is stable and well-characterized (e.g., using bootstrapping methods). The goal is to ensure that the number of replicates is sufficient to provide a reliable estimate of the output distribution.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ABM Verification

| Item / Resource | Function in Verification |

|---|---|

| Pseudo-Random Number Generators (PRNG) | Algorithms (e.g., MT19925, TAUS2, RANLUX) used to generate reproducible stochastic sequences. Critical for testing and debugging [11]. |

| Fixed Random Seeds | A set of predefined seeds used to ensure deterministic model execution across different verification tests, enabling direct comparison of results [11]. |

| Solver Relative Tolerance | A numerical parameter controlling the error tolerance of the time-integration solver. Tightening this tolerance is a key step in verifying that numerical errors are acceptable [8]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential computational resource for running the large number of replicates (often thousands) required for robust stochastic verification and convergence studies [11]. |

| Events Interface | A software component used to accurately model instantaneous changes in loads or boundary conditions (e.g., a drug bolus). Its use prevents solver convergence issues and improves accuracy [8]. |

Methodologies for Implementing Convergence Analysis in Complex ABMs

A Step-by-Step Solution Verification Framework for ABMs

Verification ensures an Agent-Based Model (ABM) is implemented correctly and produces reliable results, which is fundamental for rigorous scientific research, including drug development. This framework provides a standardized protocol for researchers to verify their ABM implementations systematically. The process is critical for establishing confidence in model predictions, particularly when ABMs are used to simulate complex biological systems, such as disease progression or cellular pathways, where accurate representation of dynamics is essential. This document outlines a step-by-step verification methodology framed within the context of time step convergence analysis, a cornerstone for ensuring numerical stability and result validity in dynamic simulations [3].

Quantitative Verification Metrics

A robust verification process relies on quantifying various aspects of model behavior. The following metrics should be tracked and analyzed throughout the verification stages.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Metrics for ABM Verification

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Target Value/Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Stability | Time Step (Δt) Convergence | < 5% change in key outputs | Systematic Δt reduction [16] |

| Solution Adaptive Optimization | Dynamic parameter adjustment | Agent-based evolutionary algorithms [16] | |

| Behavioral Validation | State Transition Accuracy | > 95% match to expected rules | Unit testing of agent logic |

| Emergent Phenomenon Consistency | Qualitative match to theory | Expert review & pattern analysis [3] | |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Parameter Perturbation Response | Smooth, monotonic output change | Local/global sensitivity analysis |

| Random Seed Dependence | < 2% output variance | Multiple runs with different seeds |

Experimental Protocols for Verification

Protocol 1: Time Step Convergence Analysis

Objective: To determine the maximum time step (Δt) that yields numerically stable and accurate results without significantly increasing computational cost.

Materials:

- The fully coded ABM

- High-performance computing (HPC) resources

- Data logging software (e.g., custom scripts, database)

Methodology:

- Initialization: Define a set of progressively smaller time steps (e.g., Δt, Δt/2, Δt/4, Δt/8).

- Baseline Simulation: Execute the model with the smallest time step (e.g., Δt/8) for a fixed simulated time. Designate the results from this run as the "ground truth" or reference solution.

- Comparative Runs: Run the model for the same simulated time using each of the larger time steps in the set.

- Output Comparison: For each run, record key model outputs (e.g., agent population counts, spatial distribution metrics, aggregate system properties) at identical time intervals.

- Error Calculation: Compute the relative error for each larger time step run against the reference solution. Common metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Convergence Determination: Identify the largest time step for which the relative error in key outputs falls below a pre-defined tolerance (e.g., 5%). This Δt is considered the converged time step for future experiments.

Protocol 2: Agent Logic and Rule Verification

Objective: To verify that individual agents are behaving according to their programmed rules and that local interactions produce the expected global dynamics.

Materials:

- ABM with modular agent logic

- Unit testing framework (e.g., JUnit for Java, pytest for Python)

- Visualization tools (e.g., NetLogo, Matplotlib) [3]

Methodology:

- Unit Testing: Isolate and test individual agent behavioral functions. For example, test if a "cell agent" correctly transitions from a healthy to an infected state upon contact with a "pathogen agent" based on the defined probability.

- Interaction Testing: Create minimal simulation environments with a small number of agents (2-5) to verify that interaction rules (e.g., attraction, repulsion, communication, infection) function as intended.

- State Transition Tracking: Implement logging to track agent state changes over time. Analyze the logs to ensure state transitions occur only under the correct conditions and with the expected probabilities.

- Visual Inspection: Use the model's visualization to observe agent behavior in a controlled, small-scale scenario. This is a qualitative but crucial step for identifying obvious rule violations or unexpected behaviors [3].

Protocol 3: Solution Adaptive Optimization for Seeding

Objective: To optimize the initial configuration of agents (seeding) for efficient exploration of the solution space in complex models, particularly in dynamic networks [16].

Materials:

- ABM with a defined fitness function

- Evolutionary computing libraries (e.g., DEAP, ECJ)

Methodology:

- Fitness Function Definition: Define a fitness function that quantifies the performance of a given seeding strategy (e.g., the speed of information spread in a social network, the rate of tumor growth suppression).

- Candidate Solution Generation: Initialize a population of candidate seeding solutions using an agent-based evolutionary approach [16].

- Adaptive Optimization: Employ a genetic algorithm where candidate solutions are evaluated within the ABM. An adaptive solution optimizer dynamically selects, crosses over, and mutates the best-performing seeding strategies over multiple generations [16].

- Validation: Run the ABM with the optimized seed and compare its outputs and convergence speed against baseline seeding strategies to verify improvement.

Verification Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and iterative nature of the proposed verification framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational tools and materials required to implement the verification framework effectively.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ABM Verification

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Verification |

|---|---|---|

| NetLogo | A programmable, multi-agent modeling environment [3] | Prototyping, visualization, and initial rule verification. |

| Repast Suite (Pyramid, Java, .NET) | A family of advanced, open-source ABM platforms. | Building large-scale, high-performance models for convergence testing. |

| AnyLogic | A multi-method simulation tool supporting ABM, discrete event, and system dynamics. | Modeling complex systems with hybrid approaches. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A collection of computers for parallel processing. | Running multiple parameter sets and small Δt simulations for convergence analysis. |

| Version Control System (e.g., Git) | A system for tracking changes in source code. | Maintaining model integrity, collaboration, and reproducing results. |

| Unit Testing Framework (e.g., JUnit, pytest) | Software for testing individual units of source code. | Automating the verification of agent logic and functions. |

| Data Logging Library (e.g., Log4j, structlog) | A tool for recording application events. | Tracking agent state transitions and model execution for post-hoc analysis. |

Adaptive Time-Stepping and Two-Layer Frameworks for Evolving Systems

Adaptive frameworks represent a paradigm shift in managing complex, evolving systems across various scientific and engineering disciplines. These frameworks are characterized by their ability to dynamically adjust system parameters or structures in response to real-time data and changing conditions. The core principle involves implementing a structured feedback mechanism that allows the system to self-optimize while maintaining operational integrity. Particularly valuable are two-layer architectures that separate strategic oversight from tactical execution, enabling sophisticated control in environments where system dynamics are non-stationary or only partially observable. Such frameworks have demonstrated significant utility in domains ranging from urban traffic management and artificial intelligence to clinical drug development, where they improve efficiency, resource allocation, and overall system resilience against unpredictable disturbances [17] [18] [19].

The mathematical foundation of these systems often rests on adaptive control theory and reinforcement learning principles, creating structures that can navigate the trade-offs between immediate performance optimization and long-term system stability. In the specific context of agent-based models (ABMs), which are computational models for simulating the interactions of autonomous agents, adaptive time-stepping becomes crucial for managing computational efficiency while maintaining model accuracy. When combined with a two-layer framework, this approach provides a powerful methodology for analyzing complex adaptive systems where micro-level interactions generate emergent macro-level phenomena [10].

Key Two-Layer Framework Implementations

Comparative Analysis of Adaptive Frameworks

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Representative Two-Layer Frameworks

| Application Domain | Framework Name | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Traffic Control | Max Pressure + Perimeter Control | Network throughput, Queue spill-back prevention | Outperformed individual layer application in almost all congested scenarios | [17] |

| Continual Machine Learning | CABLE (Continual Adapter-Based Learning) | Classification accuracy, Transfer, Severity | Mitigated catastrophic forgetting, promoted efficient knowledge transfer across tasks | [18] |

| Medical Question Answering | Two-Layer RAG | Relevance, Coverage, Coherence, Hallucination | Achieved comparable median scores to GPT-4 with significantly smaller model size | [20] |

| Energy Systems Optimization | Double-Loop Framework | Operational flexibility, Resource allocation | Enhanced efficiency in fluctuating demand and renewable energy integration | [21] |

Structural Commonalities Across Domains

Despite their application across disparate fields, these two-layer frameworks share remarkable structural similarities. The upper layer typically operates at a strategic level, processing aggregated information to establish boundaries, set objectives, or determine constraint policies. For instance, in the traffic control framework, this layer implements perimeter control based on Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams (MFDs) to regulate exchange flows between homogeneously congested regions, thus preventing over-saturation [17]. Similarly, in the CABLE framework for continual learning, the upper layer computes gradient similarity between new examples and past tasks to guide adapter selection policies [18].

Conversely, the lower layer functions at a tactical level, handling real-time, distributed decisions based on local information. In traffic systems, this manifests as Max Pressure distributed control at individual intersections, while in continual learning systems, it involves the execution of specific adapter networks for task processing. This architectural separation creates a robust control mechanism where the upper layer prevents systemic failures while the lower layer optimizes local performance, effectively balancing global efficiency with local responsiveness [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Implementation of Two-Layer Adaptive Traffic Signal Control

Objective: To implement and validate a two-layer adaptive signal control framework combining Max Pressure (MP) distributed control with Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD)-based Perimeter Control (PC) for large-scale dynamically-congested networks [17].

Materials and Computational Setup:

- Simulation Environment: Macroscopic simulation environment incorporating Store-and-Forward dynamic traffic paradigm

- Key Features: Finite queues, spill-back consideration, dynamic rerouting capabilities

- Network Scale: Real large-scale network implementation

- Demand Scenarios: Moderate and highly congested conditions with stochastic demand fluctuations up to 20% of mean

Procedure:

- Network Partitioning: Divide the large-scale network into homogeneously congested regions using MFD analysis

- Critical Node Identification: Apply the proposed algorithm to select critical nodes based on traffic characteristics for partial MP deployment

- Upper Layer Implementation:

- Implement MFD-based perimeter control to regulate transfer flows between regions

- Set optimal transfer flow thresholds based on real-time congestion measurements

- Adjust perimeter control parameters every 15 minutes based on aggregated region data

- Lower Layer Implementation:

- Deploy MP control at all critical nodes identified in step 2

- Implement distributed pressure calculation for each intersection based on local queue lengths

- Update signal phases every minute based on current pressure measurements

- Integration and Validation:

- Test the integrated two-layer framework under moderate congestion scenarios

- Validate system performance under highly congested conditions with dynamic demand patterns

- Conduct sensitivity analysis for demand stochasticity (up to 20% of mean)

- Compare against baseline scenarios: MP-only, PC-only, and traditional signal control

Performance Metrics:

- Network-wide throughput (vehicles/hour)

- Average delay time per vehicle

- Queue length and spill-back occurrence frequency

- Resilience to demand fluctuations

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Traffic Control Framework Validation

| Experimental Condition | Network Throughput (veh/hr) | Average Delay Reduction | Queue Spill-back Prevention | Stochastic Demand Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate Congestion (MP+PC) | >15% improvement vs. baselines | >20% reduction | Significant improvement (p<0.05) | Maintained performance with 20% fluctuation |

| High Congestion (MP+PC) | >20% improvement vs. baselines | >25% reduction | Eliminated recurrent spillbacks | Performance degradation <5% with 20% fluctuation |

| Partial MP Implementation | Similar to full-network MP | Comparable to full implementation | No significant difference | Maintained robustness |

Protocol: Continual Adapter-Based Learning (CABLE) Framework

Objective: To implement a reinforcement learning-based two-layer framework for continual learning that dynamically routes tasks to existing adapters, minimizing catastrophic forgetting while promoting knowledge transfer [18].

Materials and Computational Setup:

- Hardware: NVIDIA A100 GPU with CUDA compatibility

- Knowledge Base: Pre-trained CLIP model or domain-specific pre-trained models

- Benchmark Datasets: Fashion MNIST, CIFAR-100, Mini ImageNet, COIL-100, CUB, CORe50

- Adapter Architecture: Two convolutional layers appended to frozen backbone

Procedure:

- Backbone Initialization:

- Initialize frozen pre-trained knowledge base (CLIP model)

- Set requires_grad = False for all backbone parameters

- Adapter Pool Initialization:

- Create initial adapter with randomly initialized parameters sampled from Gaussian distribution

- Set adapter-specific learning parameters (SGD optimizer, batch size 32, weight decay 0.0005, momentum 0.9)

- Task Similarity Measurement:

- For each new incoming task, compute gradient similarity between task examples and existing adapters

- Calculate similarity score using cosine similarity in gradient space

- Reinforcement Learning Policy Training:

- Implement policy network that takes similarity scores as input

- Set reward function based on task performance and parameter efficiency

- Train policy using exploration rate ε = 0.2, batch size b = 50

- Adapter Selection and Creation:

- If policy selects existing adapter: Fine-tune selected adapter on new task using Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.001, decay at 55th and 80th epochs)

- If policy creates new adapter: Initialize new adapter with random Gaussian parameters

- Evaluation Protocol:

- Test all previous tasks after learning each new task

- Calculate classification accuracy, transfer, and severity metrics

- Compare against baseline methods (ER, ER+GMED, PCR, SEDEM, MoE-Adapters)

Validation Metrics:

- Classification accuracy across all learned tasks

- Transfer metric: Average change in accuracy after introducing new task

- Severity: Newly defined measure of forgetting intensity

- Parameter efficiency: Number of adapters created versus tasks learned

Visualization of Two-Layer Framework Architectures

Structural Diagram of Generic Two-Layer Adaptive Framework

Generic Two-Layer Adaptive Architecture

The diagram illustrates the core components and information flows in a generic two-layer adaptive framework. The upper layer (blue nodes) performs strategic oversight through performance analysis and constraint management, while the lower layer (green nodes) handles tactical execution. The adapter pool (yellow cylinder) enables dynamic resource allocation, and the feedback loop (gray diamond) facilitates continuous system adaptation based on performance metrics.

Implementation-Specific Workflows

Domain-Specific Framework Implementations

This diagram compares three specific implementations of two-layer frameworks across different domains. Each implementation maintains the core two-layer structure while adapting the specific components to domain-specific requirements, demonstrating the versatility of the architectural pattern.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Environments | Store-and-Forward Dynamic Traffic Paradigm | Models traffic flow with finite queues and spill-backs | Large-scale urban network simulation [17] |

| Pre-trained Models | CLIP Vision-Language Model | Frozen knowledge base for continual learning | Backbone for CABLE adapter networks [18] |

| Benchmark Datasets | CIFAR-100, Mini ImageNet, Fashion MNIST | Standardized evaluation of image classification | Continual learning task sequences [18] |

| Specialized Datasets | NOAA AIS Maritime Data, Beijing Air Quality Data | Domain-specific time series forecasting | Maritime trajectory prediction and pollution monitoring [18] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Adam | Parameter optimization with adaptive learning rates | Adapter fine-tuning in continual learning [18] |

| Evaluation Metrics | Classification Accuracy, Transfer, Severity | Quantifies continual learning performance | Measures catastrophic forgetting and knowledge transfer [18] |

| Retrieval Systems | Whoosh Information Retrieval Engine | BM25F-ranked document retrieval | Medical question-answering from social media data [20] |

| Large Language Models | GPT-4, Nous-Hermes-2-7B-DPO | Answer generation and summarization | Two-layer medical QA framework [20] |

The implementation of adaptive time-stepping within two-layer frameworks provides a robust methodology for managing complex evolving systems across computational science, engineering, and biomedical research. The experimental protocols and performance metrics outlined in this document demonstrate consistent patterns of improvement in system efficiency, resource allocation, and adaptability to changing conditions. For researchers implementing these frameworks, several critical success factors emerge:

First, the careful definition of boundary conditions between layers is essential, as overly restrictive boundaries can limit adaptation while excessively permissive boundaries may destabilize the system. Second, the temporal granularity of adaptation mechanisms must align with system dynamics—frequent adjustments for rapidly changing systems (e.g., traffic signals) versus more deliberate adaptations for stable systems (e.g., clinical trial modifications). Third, comprehensive validation protocols must assess both individual layer performance and emergent behaviors from layer interactions, particularly testing system resilience under stochastic conditions as demonstrated in the traffic control framework's evaluation under demand fluctuations up to 20% of mean values [17].

These frameworks show particular promise for agent-based model research, where they can help manage the computational complexity of micro-macro dynamics while maintaining mathematical rigor. The translation of complex ABMs into learnable probabilistic models, as demonstrated in the housing market example [10], provides a template for how two-layer frameworks can bridge the gap between theoretical modeling and empirical validation, ultimately enhancing the predictive power and practical utility of complex system simulations.

Integrating Machine Learning to Infer Rules and Improve Convergence

The integration of machine learning (ML) with agent-based modeling (ABM) represents a paradigm shift in computational biology and drug development, enabling researchers to infer behavioral rules from complex data and significantly accelerate model convergence. This fusion addresses fundamental challenges in ABM, including the abstraction of agent rules from experimental data and the extensive computational resources required for models to reach stable states. Within the context of time step convergence analysis, ML-enhanced ABMs facilitate more accurate simulations of biological systems, from multicellular interactions to disease progression, by ensuring that the simulated dynamics faithfully represent underlying biological processes. These advancements are critical for developing predictive models of drug efficacy, patient-specific treatment responses, and complex disease pathologies, ultimately streamlining the drug development pipeline.

Agent-based modeling is a powerful computational paradigm for simulating complex systems by modeling the interactions of autonomous agents within an environment. In biomedical research, ABMs simulate everything from intracellular signaling to tissue-level organization and population-level epidemiology [5]. However, traditional ABMs face two significant challenges: first, the rules governing agent behavior are often difficult to abstract and formulate directly from experimental data; second, these models can require substantial computational resources and time to converge to a stable state or representative outcome [5] [22].

Machine learning offers synergistic solutions to these challenges. ML algorithms can "learn" optimal ABM rules from large datasets, bypassing the need for manual, a priori rule specification. Furthermore, ML can guide ABMs toward faster convergence by optimizing parameters and initial conditions [22]. The convergence of an ABM—the point at which the model's output stabilizes across repeated simulations—is a critical metric of its reliability and computational efficiency, especially when analyzing dynamics over discrete time steps. For researchers and drug development professionals, robust convergence analysis ensures that simulated drug interventions or disease mechanisms are statistically sound and reproducible.

This Application Note provides a detailed framework for integrating ML with ABM to infer agent rules and improve convergence, complete with experimental protocols, visualization workflows, and a curated toolkit for implementation.

Core Concepts and Synergistic Integration

The ABM⇄ML Loop in Biomedical Systems

The integration of ML and ABM is not a one-way process but a synergistic loop (ABM⇄ML). ML can be applied to infer the rules that govern agent behavior from high-dimensional biological data, such as single-cell RNA sequencing or proteomics data [5]. Once a rule-set is devised, running ABM simulations generates a wealth of data that can be analyzed again using ML to identify robust emergent patterns and statistical measures [5]. This cyclic interaction is particularly powerful for modeling multi-scale biological processes where cellular decisions lead to tissue-level phenomena.

The Role of ML in Convergence Analysis

Convergence in ABMs is hindered by stochasticity and the high-dimensional parameter space. ML algorithms, particularly reinforcement learning (RL), can be integrated directly into the simulation to help agents adapt their strategies, leading to faster convergence to realistic system-level behaviors [22]. Furthermore, supervised learning models can analyze outputs from preliminary ABM runs to identify parameter combinations and time-step configurations that lead to the most rapid and stable convergence, optimizing the simulation setup before costly, long-running simulations are executed.

Application Notes: Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Inferring Agent Rules from Observational Data

This protocol details the process of using ML to derive the decision-making rules for agents from empirical data, such as cell tracking or patient data.

- Objective: To construct a data-driven ABM where agent rules are not predefined but learned from experimental measurements.

- Materials: High-dimensional dataset (e.g., single-cell omics, clinical time-series data), computational environment (e.g., Python, NetLogo with extensions).

- Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Clean and normalize the raw data. For temporal data, structure it into state-action pairs (e.g., "current cell state" and "observed behavioral outcome").

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Recursive Feature Elimination to identify the most critical variables influencing agent behavior [23].

- Model Selection and Training: Train an interpretable ML model to map agent states to behaviors.

- Rule Integration: Translate the trained ML model (e.g., the decision paths of a Decision Tree) into the conditional logic (

if-thenrules) governing the agents in the ABM platform. - Validation: Run the ABM and compare its emergent population-level outputs to held-out experimental data not used in training, ensuring the learned rules generate realistic dynamics.

Protocol 2: Improving Convergence with Advanced Numerical Methods and ML

This protocol focuses on strategies to reduce the number of time steps and computational resources required for an ABM to reach a stable solution.

- Objective: To enhance the numerical stability and convergence speed of a hybrid multi-scale ABM.

- Materials: A configured hybrid ABM, numerical computing libraries (e.g., SciPy, SUNDIALS).

- Procedure:

- Hybrid Model Formulation: Define the multi-scale model. Typically, the ABM handles discrete, cellular-scale events, while a system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) describes faster, sub-cellular processes (e.g., signaling dynamics) [24].

- Solver Selection: Implement a sophisticated numerical solver for the ODE component. Adams-Bashforth-Moulton (ABM) predictor-corrector methods are highly effective, as they offer higher-order accuracy with reduced local truncation errors, leading to more stable integration over many time steps [25].

- Temporally-Separated Linking: Solve the continuum (ODE) model on a faster time scale than the ABM. Sync the scales at predefined intervals to exchange information [24].

- ML-Guided Calibration: Use the outputs from initial, short ABM runs to train a surrogate ML model (e.g., a Gaussian Process) to predict final system states. This surrogate can then be used to identify and pre-set optimal initial conditions and parameters that lead to faster convergence in the full-scale simulation.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating ML with ABM to infer rules and improve convergence, as described in the protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for implementing the protocols outlined in this document.

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for ML-ABM Integration

| Tool / Technique | Category | Primary Function in ML-ABM Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Trees / Random Forests [22] | Machine Learning | Provides interpretable models for deriving transparent, rule-based agent logic from data. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) [22] | Machine Learning | Enables agents to learn optimal behaviors through interaction with the simulated environment, improving behavioral accuracy and convergence. |

| Adams-Bashforth-Moulton (ABM) Solver [25] | Numerical Method | A predictor-corrector method for solving ODEs in hybrid models with high accuracy and stability, directly improving convergence. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [23] | Data Preprocessing | Reduces the dimensionality of input data, mitigating overfitting and identifying key drivers of agent behavior. |

| Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) [26] | Interoperability | Provides cross-platform compatibility for ML models, allowing seamless integration of trained models into various ABM frameworks. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Outcomes

The integration of ML and ABM yields measurable improvements in model performance and predictive power. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of ML-ABM Integration on Model Performance

| Performance Metric | Traditional ABM | ML-Enhanced ABM | Context / Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion Rate Increase | Baseline | Up to 30% | Account-Based Marketing (as a proxy for targeting efficacy) | [27] |

| Deal Closure Rate | Baseline | 25% increase | Sales pipeline (as a proxy for intervention success) | [27] |

| Sales Cycle Reduction | Baseline | 30% reduction | Process efficiency (as a proxy for accelerated discovery) | [27] |

| Behavioral Accuracy | Predefined, static rules | Significantly higher | Agent decision-making using Reinforcement Learning | [22] |

| Numerical Precision | First-order solvers (e.g., Euler) | Second-order accuracy | ODE solving with ABM-Solver in Rectified Flow models | [25] |