Uncertainty Quantification in Computational Models: From Foundations to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) methodologies and their critical applications in computational science and biomedicine.

Uncertainty Quantification in Computational Models: From Foundations to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) methodologies and their critical applications in computational science and biomedicine. It explores foundational UQ concepts, including the distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty, and details advanced techniques like polynomial chaos, ensembling, and Bayesian inference. The content covers practical implementation strategies for drug discovery and biomedical models, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios with limited data, and examines Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) frameworks for building credibility. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current UQ practices to enhance model reliability and support risk-informed decision-making in precision medicine and therapeutic development.

Understanding Uncertainty Quantification: Core Concepts and Critical Importance

Defining Aleatory vs. Epistemic Uncertainty in Scientific Models

In the realm of computational modeling for scientific research, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, the precise characterization and quantification of uncertainty is not merely an academic exercise—it is a fundamental requirement for model reliability and regulatory acceptance. Uncertainty permeates every stage of model development, from conceptualization through implementation to prediction. The distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty provides a crucial philosophical and practical framework for categorizing and addressing these uncertainties systematically [1]. While both types manifest as unpredictability in model outputs, their origins, reducibility, and implications for decision-making differ profoundly.

Aleatory uncertainty (from Latin "alea" meaning dice) represents the inherent randomness, variability, or stochasticity natural to a system or phenomenon. This type of uncertainty is irreducible in principle, as it stems from the fundamental probabilistic nature of the system being modeled, persisting even under perfect knowledge of the underlying mechanisms [2]. In contrast, epistemic uncertainty (from Greek "epistēmē" meaning knowledge) arises from incomplete information, limited data, or imperfect understanding on the part of the modeler. This form of uncertainty is theoretically reducible through additional data collection, improved measurements, or model refinement [3] [4]. The ability to distinguish between these uncertainty types enables researchers to allocate resources efficiently, focusing reduction efforts where they can be most effective while acknowledging inherent variability that cannot be eliminated.

Conceptual Foundations and Distinctions

Defining Characteristics and Properties

The conceptual distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty extends beyond their basic definitions to encompass fundamentally different properties and implications for scientific modeling. These characteristics determine how each uncertainty type should be represented, quantified, and ultimately addressed within a modeling framework.

Aleatory uncertainty embodies the concept of intrinsic randomness or variability that would persist even with perfect knowledge of system mechanics. This category includes stochastic processes such as thermal fluctuations in chemical reactions, quantum mechanical phenomena, environmental variations affecting biological systems, and the inherent randomness in particle interactions [2]. In pharmaceutical contexts, this might manifest as inter-individual variability in drug metabolism or random fluctuations in protein folding dynamics. The irreducible nature of aleatory uncertainty means it cannot be eliminated by improved measurements or additional data collection, though it can be precisely characterized through probabilistic methods.

Epistemic uncertainty represents limitations in knowledge, modeling approximations, or incomplete information that theoretically could be reduced through better science. This encompasses uncertainty about model parameters, structural inadequacies in mathematical representations, insufficient data for reliable estimation, and limitations in experimental measurements [3] [1]. In drug development, epistemic uncertainty might arise from limited understanding of a biological pathway, incomplete clinical trial data, or simplification of complex physiological processes in pharmacokinetic models. Unlike aleatory uncertainty, epistemic uncertainty can potentially be minimized through targeted research, improved experimental design, or model refinement.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Aleatory and Epistemic Uncertainty

| Characteristic | Aleatory Uncertainty | Epistemic Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inherent system variability or randomness | Incomplete knowledge or information |

| Reducibility | Irreducible in principle | Reducible through additional data or improved models |

| Representation | Probability distributions | Confidence intervals, belief functions, sets of distributions |

| Data Dependence | Persistent with infinite data | Diminishes with increasing data |

| Common Descriptors | Random variables, stochastic processes | Model parameters, structural uncertainty |

Practical Implications of the Distinction

The classification of uncertainties as either aleatory or epistemic carries significant practical implications for modeling workflows, resource allocation, and decision-making processes. From a pragmatic standpoint, this distinction helps modelers identify which uncertainties have the potential for reduction through targeted investigation [1]. When epistemic uncertainties dominate, resources can be directed toward data collection, model refinement, or experimental validation. Conversely, when aleatory uncertainties prevail, efforts may be better spent on characterizing variability and designing robust systems that perform acceptably across the range of possible outcomes.

The distinction also critically influences how dependence among random events is modeled. Epistemic uncertainties can introduce statistical dependence that might not be properly accounted for if their character is not correctly modeled [1]. For instance, in a system reliability problem, shared epistemic uncertainty about material properties across components creates dependence that significantly affects system failure probability estimates. Similarly, in time-variant reliability problems, proper characterization of both uncertainty types is essential for accurate risk assessment over time.

From a decision-making perspective, the separation of uncertainty types enables more informed risk management strategies. In pharmaceutical development, understanding whether uncertainty about a drug's efficacy stems from inherent patient variability (aleatory) versus limited clinical data (epistemic) directly impacts regulatory strategy and further development investments. This distinction becomes particularly crucial in performance-based engineering and risk-based decision-making frameworks where uncertainty characterization directly influences safety factors and design standards [1].

Quantitative Representation and Mathematical Frameworks

Mathematical Representations and Propagation

The quantitative representation and propagation of aleatory and epistemic uncertainties require distinct mathematical frameworks that respect their fundamental differences. For aleatory uncertainty, conventional probability theory with precisely known parameters typically suffices. However, when epistemic uncertainty is present, more advanced mathematical structures are necessary to properly represent incomplete knowledge.

Dempster-Shafer (DS) structures provide a powerful framework for representing epistemic uncertainty by assigning belief masses to intervals or sets of possible values rather than specific point estimates [2]. In this representation, epistemic uncertainty in a parameter (x) might be expressed as (x \sim {([\underline{x}i, \overline{x}i], pi)}{i=1}^n), where each interval ([\underline{x}i, \overline{x}i]) receives a probability mass (p_i). This structure naturally captures the idea of having limited or imprecise information about parameter values.

For systems involving both uncertainty types, a hierarchical representation emerges where aleatory uncertainty is modeled through conditional probability distributions parameterized by epistemically uncertain variables. The propagation of these combined uncertainties through system models follows a two-stage approach. First, aleatory uncertainty is modeled conditional on epistemic parameters, often through stochastic differential equations or conditional probability densities such as (p(t,x∣θ)≈\mathcal{N}(x; μ(θ), σ^2(θ))), where (θ) represents epistemically uncertain parameters [2]. Second, epistemic uncertainty is propagated through moment evolution equations, which for polynomial systems can be derived using Itô's lemma:

[ \dot{M}k∣{e0} = -k \sumi αi m{i+k-1}∣{e0} + \frac{1}{2} k(k-1) q^2 m{k-2}∣{e_0} ]

where statistical moments (M_k) and parameters become interval-valued due to epistemic uncertainty [2].

Table 2: Mathematical Representations for Different Uncertainty Types

| Uncertainty Type | Representation Methods | Key Mathematical Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Purely Aleatory | Probability theory | Random variables, stochastic processes, probability density functions |

| Purely Epistemic | Evidence theory, Interval analysis | Dempster-Shafer structures, credal sets, p-boxes |

| Mixed Uncertainties | Hierarchical probabilistic models | Second-order probability, Bayesian hierarchical models |

Output Representation and Decision Aggregation

After propagating mixed uncertainties through a system model, the resulting uncertainty in system response is typically expressed using probability boxes (p-boxes) within a Dempster-Shafer structure: ({([Fl(x), Fu(x)], pi)}), where each ([Fl(x), F_u(x)]) bounds the cumulative distribution function envelopes induced by the propagated moment intervals for each focal element [2]. This representation preserves the separation between aleatory variability (captured by the CDFs) and epistemic uncertainty (captured by the interval-valued CDFs and their assigned masses).

Prior to decision-making, this second-order uncertainty is often "crunched" into a single actionable distribution through transformations such as the pignistic transformation:

[ P{\text{Bet}}(X ≤ x) = \frac{1}{2} \sumi \left( \underline{N}i(x) + \overline{N}i(x) \right) p_{D,i} ]

which converts set-valued belief structures into a single cumulative distribution function for expected utility calculations and risk analysis [2]. Quantitative indices such as the Normalized Index of Decision Insecurity (NIDI) or the ignorance function ((I_g)) can be computed to assess residual ambiguity and guide confidence-aware decision policies, providing metrics for how much epistemic uncertainty remains in the final analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Uncertainty Quantification

Protocol 1: Bayesian Neural Networks for Epistemic Uncertainty Quantification

Purpose: To quantify epistemic uncertainty in deep learning models used for scientific applications, such as quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling in drug development.

Theoretical Basis: In Bayesian deep learning, epistemic uncertainty is captured through distributions over model parameters rather than point estimates [4]. This approach treats the weights (W) of a neural network as random variables with a prior distribution (p(W)) that is updated through Bayesian inference to obtain a posterior distribution (p(W|X,Y)) given data ((X,Y)).

Materials and Reagents:

- TensorFlow Probability or PyTorch with Bayesian layers: Enables implementation of variational inference for neural networks

- Dataset: Domain-specific dataset (e.g., chemical compounds with associated biological activities)

- High-performance computing resources: GPUs for efficient sampling and training

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Implement a neural network with probabilistic layers. For example, using TensorFlow Probability's

DenseVariationallayer, which places distributions over weights rather than point estimates [4]. - Prior Definition: Define appropriate prior distributions for network parameters, typically Gaussian priors with specified mean and variance.

- Variational Inference: Approximate the true posterior (p(W|X,Y)) using a variational distribution (q_θ(W)) parameterized by (θ).

- Loss Optimization: Minimize the negative Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) loss function: [ \mathcal{L}(θ) = \mathbb{E}{qθ(W)}[\log p(Y|X,W)] - \text{KL}(q_θ(W) \| p(W)) ] which balances data fit with regularization toward the prior.

- Uncertainty Estimation: For prediction on a new sample (x^), approximate the predictive distribution: [ p(y^|x^,X,Y) ≈ \int p(y^|x^*,W)q_θ(W)dW ] using Monte Carlo sampling from the variational posterior.

- Epistemic Uncertainty Quantification: Compute the standard deviation of predictions across multiple stochastic forward passes as a measure of epistemic uncertainty.

Interpretation: The epistemic uncertainty, quantified by the variability in predictions under different parameter samples, decreases as more data becomes available and the posterior distribution over weights tightens [4].

Protocol 2: Aleatoric Uncertainty Quantification with Probabilistic Regression

Purpose: To quantify aleatoric uncertainty in regression tasks, capturing inherent noise in the data generation process that persists regardless of model improvements.

Theoretical Basis: Aleatoric uncertainty is modeled by making the model's output parameters of a probability distribution rather than point predictions [4]. For continuous outcomes, this typically involves predicting both the mean and variance of a Gaussian distribution, with the variance representing heteroscedastic aleatoric uncertainty.

Materials and Reagents:

- Deep learning framework with probabilistic capabilities (TensorFlow Probability, PyTorch)

- Dataset with observed input-output pairs, ideally with replication to estimate inherent variability

- Standard computing resources: Aleatoric uncertainty quantification is computationally less demanding than full Bayesian inference

Procedure:

- Model Architecture: Design a neural network with two output units – one predicting the mean (μ(x)) and another predicting the variance (σ^2(x)) of the target distribution.

- Distribution Layer: Implement a

DistributionLambdalayer that constructs a Gaussian distribution parameterized by the network's outputs: [ p(y|x) = \mathcal{N}(y; μ(x), σ^2(x)) ] - Loss Function: Use the negative log-likelihood as the loss function: [ \mathcal{L} = -\sum{i=1}^N \log p(yi|x_i) ] which naturally balances mean prediction accuracy with uncertainty calibration.

- Model Training: Optimize all network parameters simultaneously using stochastic gradient descent.

- Aleatoric Uncertainty Extraction: For new predictions, the predicted variance represents the aleatoric uncertainty, which captures how much noise is expected in the outcome for the given input.

Interpretation: Unlike epistemic uncertainty, aleatoric uncertainty does not decrease with additional data from the same data-generating process [4]. The predicted variance reflects inherent noise or variability that cannot be reduced through better modeling or more data collection.

Protocol 3: Distinguishing Epistemic and Aleatoric Uncertainty in Language Models

Purpose: To identify and separate epistemic from aleatoric uncertainty in large language models (LLMs) applied to scientific text generation or analysis.

Theoretical Basis: In language models, token-level uncertainty mixes both epistemic and aleatoric components [5]. Epistemic uncertainty reflects the model's ignorance about factual knowledge, while aleatoric uncertainty stems from inherent unpredictability in language (multiple valid ways to express the same concept).

Materials and Reagents:

- Two language models of different capacities (e.g., LLaMA 7B and LLaMA 65B)

- Text corpora from relevant scientific domains

- Linear probing implementation for model activations

Procedure:

- Contrastive Setup: Use a large, powerful model (e.g., LLaMA 65B) as a reference for "knowable" information, assuming it has less epistemic uncertainty than a smaller model (e.g., LLaMA 7B).

- Token Classification: For each token generated by the small model, classify uncertainty type based on the entropy difference between models:

- Compute next-token predictive entropy for both small ((HS)) and large ((HL)) models

- Flag tokens where (HS) is high but (HL) is low as primarily epistemic uncertainty

- Tokens where both models show high entropy indicate primarily aleatoric uncertainty

- Probe Training: Train linear classifiers on the small model's internal activations to predict the epistemic uncertainty labels derived from the contrastive analysis.

- Unsupervised Alternative: For cases where a large reference model is unavailable, implement unsupervised methods that detect epistemic uncertainty through analysis of activation patterns.

Interpretation: This approach allows for targeted improvement of language model reliability in scientific applications by identifying when model uncertainty stems from lack of knowledge (potentially fixable) versus inherent language ambiguity (unavoidable) [5].

Research Toolkit for Uncertainty Quantification

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Uncertainty Quantification in Scientific Models

| Tool/Reagent | Type/Category | Function in Uncertainty Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow Probability | Software library | Implements probabilistic layers for aleatoric uncertainty and Bayesian neural networks for epistemic uncertainty [4] |

| Dempster-Shafer Structures | Mathematical framework | Represents epistemic uncertainty through interval-valued probabilities and belief masses [2] |

| Bayesian Neural Networks | Modeling approach | Quantifies epistemic uncertainty through distributions over model parameters [4] |

| Probabilistic Programming | Programming paradigm | Enables flexible specification and inference for complex hierarchical models with mixed uncertainties |

| Linear Probes | Diagnostic tool | Identifies epistemic uncertainty in internal model representations [5] |

| P-Boxes (Probability Boxes) | Output representation | Visualizes and quantifies mixed uncertainty in prediction outputs [2] |

Applications in Scientific Domains

Drug Development and Pharmaceutical Applications

In pharmaceutical research and development, the distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainty directly impacts decision-making across the drug discovery pipeline. In early-stage discovery, epistemic uncertainty often dominates due to limited understanding of novel biological targets, incomplete structure-activity relationship data, and simplified representations of complex physiological systems in silico models. Targeted experimental designs can systematically reduce these epistemic uncertainties, focusing resources on the most influential unknown parameters.

As compounds progress through development, aleatory uncertainty becomes increasingly significant, particularly in clinical trials where inter-individual variability in drug response, metabolism, and adverse effects manifests as irreducible randomness. Proper characterization of this variability through mixed-effects models and population pharmacokinetics allows for robust dosing recommendations and safety profiling. The regulatory acceptance of model-based drug development hinges on transparent quantification of both uncertainty types, with epistemic uncertainty determining the "credibility" of model predictions and aleatory uncertainty defining the expected variability in real-world outcomes [1].

Engineering and Risk Assessment

In engineering applications, particularly structural reliability and risk assessment, the proper treatment of aleatory and epistemic uncertainties significantly influences safety factors and design standards [1]. Aleatory uncertainty in material properties, environmental loads, and usage patterns defines the inherent variability that designs must accommodate. Epistemic uncertainty in model form, parameter estimation, and experimental data introduces additional uncertainty that can be reduced through research, testing, and model validation.

The explicit separation of these uncertainty types enables more rational risk-informed decision-making. When epistemic uncertainties dominate, resources can be allocated to research and testing programs that reduce ignorance. When aleatory uncertainties prevail, the focus shifts to robust design strategies that perform acceptably across the range of possible conditions. This approach is particularly valuable in performance-based engineering, where understanding the sources and character of uncertainties allows for more efficient designs without compromising safety [1].

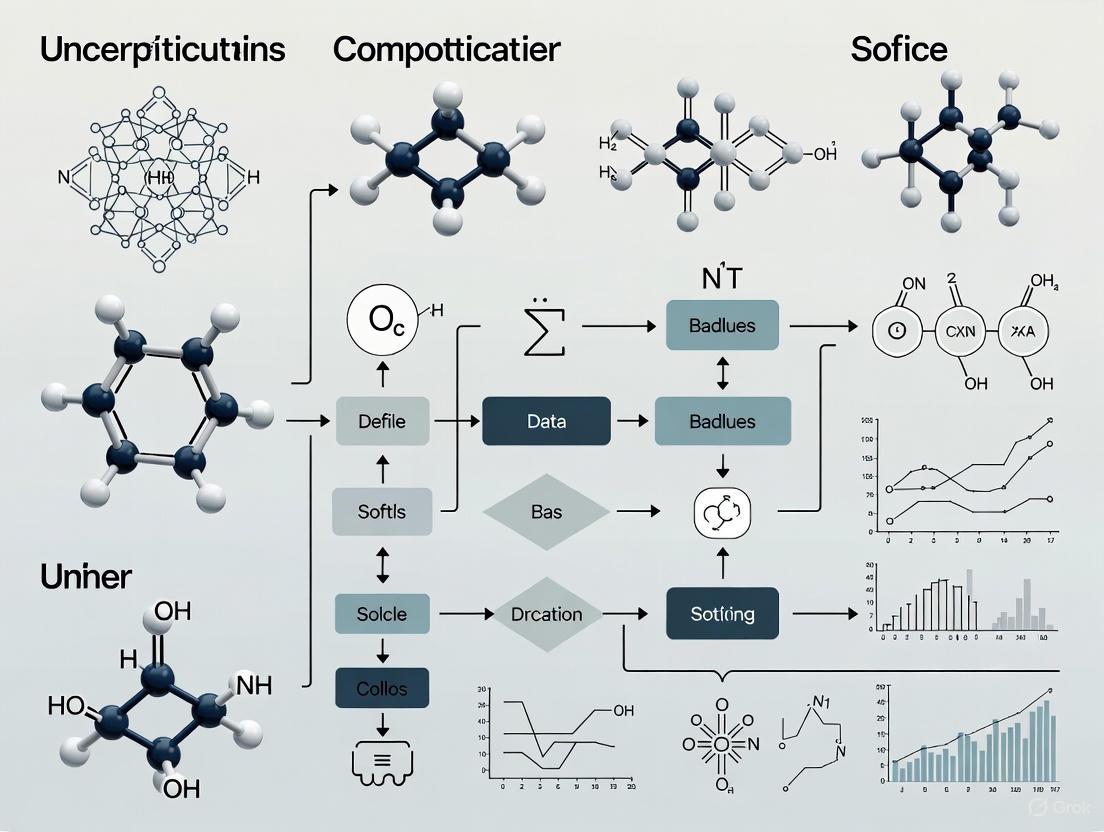

Methodological Workflow and Decision Framework

The systematic quantification and management of aleatory and epistemic uncertainties follows a structured workflow that transforms raw uncertainties into actionable insights for scientific decision-making. The process begins with uncertainty identification and classification, followed by appropriate mathematical representation, propagation through system models, and finally interpretation for specific applications.

Uncertainty Quantification and Decision Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the critical branching point where uncertainties are classified as either aleatory or epistemic, determining their subsequent mathematical treatment. The convergence of both pathways at the propagation stage acknowledges that most practical problems involve mixed uncertainties that must be propagated jointly through system models. The final decision analysis step incorporates measures of residual epistemic uncertainty (ambiguity) to enable confidence-aware decision-making.

The power of this structured approach lies in its ability to provide diagnostic insights throughout the modeling process. By maintaining the separation between uncertainty types, modelers can identify whether limitations in predictive accuracy stem from fundamental variability (suggesting acceptance or robust design) versus reducible ignorance (suggesting targeted data collection or model refinement). This diagnostic capability is particularly valuable in resource-constrained research environments where efficient allocation of investigation efforts can significantly accelerate scientific progress.

Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) constitutes a systematic framework essential for establishing credibility in computational modeling and simulation. As manufacturers increasingly shift from physical testing to computational predictive modeling throughout product life cycles, ensuring these computational models are formed using sound procedures becomes paramount [6]. VVUQ addresses this need through three interconnected processes: Verification determines whether the computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical description; Validation assesses whether the model accurately represents real-world phenomena; and Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) evaluates how variations in numerical and physical parameters affect simulation outcomes [6] [7]. This framework is particularly crucial in fields like drug discovery and precision medicine, where computational decisions guide expensive and time-consuming experimental processes, making trust in model predictions fundamental [8] [9] [10].

The paradigm of scientific computing is undergoing a fundamental shift from deterministic to nondeterministic simulations, explicitly acknowledging and quantifying various uncertainty sources throughout the modeling process [11]. This shift profoundly impacts risk-informed decision-making across engineering and scientific disciplines, enabling researchers to quantify confidence in predictions, optimize solutions stable across input variations, and reduce development costs and unexpected failures [7]. This document outlines structured protocols and application notes for implementing VVUQ within computational models, with particular emphasis on pharmaceutical applications and molecular design.

Theoretical Foundations of VVUQ

Core Definitions and Relationships

The VVUQ framework systematically addresses different aspects of model credibility. Verification is the process of determining that a computational model accurately represents the underlying mathematical model and its solution [6] [11]. Also described as "solving the equations right," verification activities include code review, comparison with analytical solutions, and convergence studies [7]. Validation, by contrast, is the process of determining the degree to which a model accurately represents the real-world system from the perspective of its intended uses [6] [11]. This "solving the right equations" process involves comparing simulation results with experimental data and assessing model performance [7]. Uncertainty Quantification is the science of quantifying, characterizing, tracing, and managing uncertainties in computational and real-world systems [7]. UQ seeks to address problems associated with incorporating real-world variability and probabilistic behavior into engineering and systems analysis, moving beyond single-point predictions to assess likely outcomes across variable inputs [7].

Uncertainty Taxonomy

Uncertainties within VVUQ are broadly classified into two fundamental categories based on their inherent nature:

Aleatoric Uncertainty: Also known as stochastic uncertainty, this represents inherent variations in physical systems or natural randomness in observed phenomena. Derived from the Latin "alea" (rolling of dice), this uncertainty is irreducible through additional data collection as it represents an intrinsic property of the system [11] [9]. Examples include material property variations, manufacturing tolerances, and stochastic environmental conditions [7].

Epistemic Uncertainty: Arising from lack of knowledge or incomplete information, this uncertainty is theoretically reducible through additional data collection or improved modeling. Derived from the Greek "episteme" (knowledge), this uncertainty manifests in regions of parameter space where data is sparse or models are inadequately calibrated [11] [9]. Examples include model form assumptions, numerical approximation errors, and unmeasured parameters [7].

Table 1: Uncertainty Classification and Characteristics

| Uncertainty Type | Nature | Reducibility | Representation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleatoric | Inherent randomness | Irreducible | Probability distributions | Material property variations, experimental measurement noise [11] [9] |

| Epistemic | Lack of knowledge | Reducible | Intervals, belief/plausibility | Model form assumptions, sparse data regions, numerical errors [11] [9] |

Additional uncertainty sources include approximation uncertainty from model incompetence in fitting complex data, though this is often considered negligible for universal approximators like deep neural networks [9]. Numerical uncertainty arises from discretization, iteration, and computer round-off errors addressed through verification techniques [11].

VVUQ Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive VVUQ workflow, integrating verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification processes into a unified framework for establishing model credibility.

VVUQ Application in Drug Discovery

The Uncertainty Challenge in Pharmaceutical Development

In drug discovery, decisions regarding which experiments to pursue are increasingly influenced by computational models for quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) [8]. These decisions are critically important due to the time-consuming and expensive nature of wet-lab experiments, with typical discovery cycles extending over 3-6 years and costing millions of dollars. Accurate uncertainty quantification becomes essential to use resources optimally and improve trust in computational models [8] [9]. A fundamental challenge arises from the fact that computational methods for QSAR modeling often suffer from limited data and sparse experimental observations, with approximately one-third or more of experimental labels being censored (providing thresholds rather than precise values) in real pharmaceutical settings [8].

The problem of human trust represents one of the most fundamental challenges in applied artificial intelligence for drug discovery [9]. Most in silico models provide reliable predictions only within a limited chemical space covered by the training set, known as the applicability domain (AD). Predictions for compounds outside this domain are unreliable and potentially dangerous for drug-design decision-making [9]. Uncertainty quantification addresses this by enabling autonomous drug designing through confidence level assessment of model predictions, quantitatively representing prediction reliability to assist researchers in molecular reasoning and experimental design [9].

Uncertainty Quantification Methods for Drug Discovery

Multiple UQ approaches have been deployed in drug discovery projects, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation considerations:

Similarity-Based Approaches: These methods operate on the principle that if a test sample is too dissimilar to training samples, the corresponding prediction is likely unreliable [9]. This category includes traditional applicability domain definition methods such as bounding boxes, convex hull approaches, and k-nearest neighbors distance calculations [9]. These methods are more input-oriented, considering the feature space of samples with less emphasis on model structure.

Bayesian Methods: These approaches treat model parameters and outputs as random variables, employing maximum a posteriori estimation according to Bayes' theorem [9]. Bayesian neural networks provide a principled framework for uncertainty decomposition but often require specialized implementations and can be computationally intensive for large-scale models.

Ensemble-Based Strategies: These methods leverage the consistency of predictions from various base models as an estimate of confidence [9]. Techniques include bootstrap aggregating (bagging) and deep ensembles, which have demonstrated strong performance in molecular property prediction tasks while maintaining implementation simplicity.

Table 2: Uncertainty Quantification Methods in Drug Discovery

| Method Category | Core Principle | Representative Techniques | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based | Predictions for samples dissimilar to training set are unreliable | Bounding Box, Convex Hull, k-NN Distance [9] | Intuitive interpretation, model-agnostic | Limited model-specific insights, dependence on feature representation |

| Bayesian | Parameters and outputs treated as random variables | Bayesian Neural Networks, Monte Carlo Dropout [9] | Principled uncertainty decomposition, strong theoretical foundation | Computational intensity, implementation complexity |

| Ensemble-Based | Prediction variance across models indicates uncertainty | Bootstrap Aggregating, Deep Ensembles [8] [9] | Implementation simplicity, strong empirical performance | Computational cost multiple models, potential correlation issues |

Advanced UQ Protocol: Handling Censored Regression Labels

Pharmaceutical data often contains censored labels where precise measurement values are unavailable, instead providing thresholds (e.g., "greater than" or "less than" values). Standard UQ approaches cannot fully utilize this partial information, necessitating specialized protocols.

Protocol 3.1: Censored Regression with Uncertainty Quantification

Objective: Adapt ensemble-based, Bayesian, and Gaussian models to learn from censored regression labels for reliable uncertainty estimation in pharmaceutical settings.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Experimental data with both precise and censored labels (typically ≥30% censored in pharmaceutical applications)

- Implementation of Tobit model from survival analysis

- Computational environment: Python 3.11 with PyTorch 2.0.1 or equivalent deep learning framework

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Identify and flag censored labels in the dataset, distinguishing left-censored (below detection threshold), right-censored (above detection threshold), and precise measurements.

- Model Adaptation: Implement Tobit likelihood function for each model type:

- For ensemble methods: Modify loss function to incorporate censored information across ensemble members

- For Bayesian networks: Implement censored-aware posterior estimation

- For Gaussian models: Adapt variance estimation to account for censored regions

- Temporal Evaluation: Assess model performance on time-split data to simulate real-world deployment conditions and evaluate temporal generalization.

- Uncertainty Calibration: Validate uncertainty estimates using proper scoring rules and calibration metrics specific to censored data scenarios.

Validation Metrics:

- Ranking ability: Correlation between uncertainty estimates and prediction errors (Spearman correlation for regression)

- Calibration ability: Agreement between predicted confidence intervals and empirical error distributions

- Temporal performance: Model degradation assessment over time with changing data distributions

Implementation Notes: This protocol has demonstrated essential improvements in reliably estimating uncertainties in real pharmaceutical settings where substantial portions of experimental labels are censored [8].

VVUQ in Molecular Design and Digital Twins

Uncertainty-Aware Molecular Design Framework

Molecular design presents unique challenges for uncertainty quantification, particularly when optimizing across expansive chemical spaces where models must extrapolate beyond training data distributions. The integration of UQ with graph neural networks (GNNs) enables more reliable exploration of chemical space by quantifying prediction confidence for novel molecular structures [12].

Protocol 4.1: UQ-Enhanced Molecular Optimization with Graph Neural Networks

Objective: Integrate uncertainty quantification with directed message passing neural networks (D-MPNNs) and genetic algorithms for efficient molecular design across broad chemical spaces.

Computational Resources:

- Graph neural network implementation (Chemprop recommended)

- Tartarus and GuacaMol platforms for benchmarking

- Genetic algorithm framework for molecular optimization

Experimental Workflow:

- Surrogate Model Development: Train D-MPNN models on molecular structure-property data to predict target properties and their associated uncertainties.

- Uncertainty Integration: Implement probabilistic improvement optimization (PIO) to guide molecular exploration based on the likelihood that candidate molecules exceed predefined property thresholds.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Balance competing design objectives using uncertainty-weighted selection criteria, particularly advantageous when objectives are mutually constraining.

- Validation and Selection: Synthesize and experimentally characterize top candidate molecules identified through the uncertainty-aware optimization process.

Key Implementation Considerations:

- The PIO approach is particularly effective for practical applications where molecular properties must meet specific thresholds rather than extreme values

- Multi-objective tasks benefit substantially from UQ integration, balancing exploration and exploitation in chemically diverse regions

- Benchmark against uncertainty-agnostic approaches using established molecular design platforms

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for uncertainty-aware molecular design combining GNNs with genetic algorithms:

VVUQ for Digital Twins in Precision Medicine

Digital twins in precision medicine represent virtual representations of individual patients that simulate health trajectories and interventions, creating demanding requirements for VVUQ implementation [10]. The VVUQ framework is essential for ensuring safety and efficacy when integrating digital twins into clinical practice.

Verification Challenges: Code verification for multi-scale physiological models spanning cellular to organ-level processes, with particular emphasis on numerical accuracy and solution convergence for coupled differential equation systems.

Validation Methodologies: Development of personalized trial methodologies and patient-specific validation metrics comparing virtual predictions with clinical observations across diverse patient populations.

Uncertainty Quantification: Characterization of parameter uncertainties, model form uncertainties, and intervention response variabilities across virtual patient populations.

Standardization Needs: Establishment of standardized VVUQ processes specific to medical digital twins, addressing regulatory requirements and clinical acceptance barriers [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for VVUQ Implementation

| Tool/Category | Function | Example Applications | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASME VVUQ Standards | Terminology and procedure standardization | Terminology (VVUQ 1-2022), Solid Mechanics (V&V 10-2019), Medical Devices (V&V 40-2018) [6] | Provides standardized frameworks for credibility assessment |

| UQ Software Platforms | Uncertainty propagation and analysis | SmartUQ for design of experiments, calibration, statistical comparison [7] | Offers specialized tools for uncertainty propagation and sensitivity analysis |

| Graph Neural Networks | Molecular representation learning | D-MPNN in Chemprop for molecular property prediction [12] | Enables direct operation on molecular graphs with uncertainty quantification |

| Bayesian Inference Tools | Probabilistic modeling and inference | Bayesian neural networks, Monte Carlo dropout methods [9] | Provides principled uncertainty decomposition |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Method evaluation and comparison | Tartarus (materials science), GuacaMol (drug discovery) [12] | Enables standardized performance assessment across methods |

| Censored Data Handlers | Management of threshold-based observations | Tobit model implementations for censored regression [8] | Essential for pharmaceutical data with detection limit censoring |

Concluding Remarks

The VVUQ framework represents a fundamental shift from deterministic to probabilistically rigorous computational modeling, enabling credible predictions for high-consequence decisions in drug discovery, molecular design, and precision medicine. Successful implementation requires systematic attention to verification principles, validation against high-quality experimental data, and comprehensive uncertainty quantification addressing both aleatoric and epistemic sources. The protocols and applications outlined herein provide actionable guidance for researchers implementing VVUQ in computational models, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. As computational models continue to increase in complexity and scope, further development of standardized VVUQ methodologies remains essential for bridging the gap between simulation and clinical or industrial application.

Uncertainty quantification (UQ) provides a structured framework for understanding how variability and errors in model inputs and assumptions propagate to affect biomedical research outputs and clinical decisions [13]. In healthcare, clinical decision-making is a critical process that directly affects patient outcomes, yet inherent uncertainties in medical data, patient responses, and treatment outcomes pose significant challenges [13]. These uncertainties stem from various sources, including variability in patient characteristics, limitations of diagnostic tests, and the complex nature of diseases [13].

The three pillars of model credibility in computational biomedicine are verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification [13]. While verification ensures the computational implementation correctly solves the model equations and validation confirms the model matches experimental behavior, UQ addresses how uncertainties in inputs affect outputs, making it equally crucial for establishing model trustworthiness [13]. As biomedical research increasingly relies on complex computational models and data-driven approaches, systematically analyzing uncertainties becomes essential for improving the precision and reliability of medical evaluations.

UQ Applications in Biomedical Research: Protocols and Data Analysis

Biomarker Discovery and Validation for Neurological Diseases

Experimental Protocol: Biomarker Identification and Tracking for Motor Neuron Disease

- Objective: To discover and validate biomarkers for improving diagnosis, monitoring progression, and guiding treatment decisions in motor neuron disease (MND) [14].

- Materials and Reagents:

- Patient blood samples for plasma isolation

- DNA/RNA extraction kits

- Next-generation sequencing reagents

- ELISA kits for target protein quantification

- Cell culture materials for extracellular vesicle isolation

- MRI contrast agents (where applicable)

- Methodology:

- Patient Cohort Selection: Recruit MND patients and age-matched healthy controls following ethical approval and informed consent. Document disease stage, progression history, and genetic background [14].

- Multimodal Sample Collection: Collect blood samples for molecular analysis (cell-free DNA, proteins, extracellular vesicles) and schedule brain MRI scans using standardized protocols [14].

- Molecular Profiling:

- Neuroimaging:

- Data Integration and Biomarker Validation:

- Apply machine learning and bioinformatics approaches to identify biomarker patterns from multimodal datasets [14].

- Correlate biomarker levels with clinical scores and progression rates.

- Validate candidate biomarkers in an independent patient cohort to assess reproducibility and clinical utility [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Data Analysis in MND Biomarker Discovery

| Biomarker Type | Measurement Technique | Data Variability Source | UQ Method Applied | Key Outcome Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Biomarkers | Next-Generation Sequencing | Sequencing depth, alignment errors | Confidence intervals for mutation frequency | Sensitivity/Specificity for disease subtyping |

| Protein Biomarkers | ELISA/MS-based Proteomics | Inter-assay precision, biological variation | Error propagation from standard curves | Correlation with disease progression (R² value) |

| Imaging Biomarkers | Advanced MRI | Scanner variability, patient movement | Test-retest reliability analysis | Effect size in differentiating patient groups |

| Metabolic Biomarkers | Metabolomics Platform | Instrument drift, peak identification | Principal component analysis with uncertainty | Predictive accuracy for treatment response |

Uncertainty-Aware Diagnostic Imaging Analysis

Application Note: Quantifying Uncertainty in Medical Image Processing for Clinical Decision Support

Medical image processing algorithms often serve as either self-contained models or components within larger simulations, making UQ for these tools critical for clinical adoption [13]. For example, an algorithm quantifying extravasated blood volume in cerebral haemorrhage patients directly influences treatment decisions, where understanding measurement uncertainty is essential [13].

Protocol: UQ for Tumor Volume Segmentation in MRI

- Objective: To quantify segmentation uncertainty in MRI-based tumor volume measurements and its impact on treatment monitoring.

- Input Data Requirements: Multi-parametric MRI scans (T1, T2, FLAIR, contrast-enhanced T1) with standardized acquisition parameters.

- Processing and Analysis:

- Multi-observer Annotation: Have multiple expert radiologists manually segment tumor volumes to establish ground truth with inter-observer variability [13].

- Algorithmic Segmentation: Apply deep learning-based segmentation models (e.g., U-Net variants) to generate primary volume estimates.

- Uncertainty Quantification:

- Implement test-time augmentation to assess model robustness to input variations.

- Use Monte Carlo dropout during inference to estimate model uncertainty.

- Calculate volume difference metrics between algorithmic and expert segmentations.

- Uncertainty Propagation: Model how segmentation uncertainty affects subsequent clinical decisions, such as determining treatment response based on volume changes.

Table 2: Uncertainty Sources in Diagnostic Imaging Models

| Uncertainty Category | Source Example | Impact on Model Output | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Related (Aleatoric) | MRI image noise, partial volume effects | Irreducible variability in pixel intensity | Characterize noise distribution, use robust loss functions |

| Model-Related (Epistemic) | Limited training data for rare findings, model architecture choices | Poor generalization to new datasets | Bayesian neural networks, ensemble methods, data augmentation |

| Coupling-Related | Geometry extraction from segmentation for surgical planning | Errors in 3D reconstruction from 2D slices | Surface smoothing algorithms, manual review checkpoints |

Enhancing Clinical Trial Design Through UQ

Protocol: Incorporating Biomarkers and UQ in Clinical Trial Outcomes

Researchers at the UQ Centre for MND Research focus on developing biomarkers that provide clear, data-driven readouts of whether a therapy is working, helping to accelerate and refine MND clinical trials [14]. The integration of UQ in this process allows for better trial design and more nuanced interpretation of results.

Methodology:

- Endpoint Selection: Identify and validate quantitative biomarkers (imaging, blood-based, or physiological) as secondary or primary endpoints alongside clinical scores [14].

- Uncertainty Characterization: For each biomarker endpoint, quantify measurement precision, biological variability, and assay performance metrics.

- Power Analysis: Use uncertainty estimates to perform more accurate sample size calculations, potentially reducing required patient numbers while maintaining statistical power.

- Adaptive Design: Implement futility analyses and dose adjustment rules based on biomarker trajectories and their confidence intervals during the trial.

- Subgroup Identification: Apply machine learning methods to uncertainty-aware biomarker data to identify patient subgroups with distinct treatment responses [14].

Visualization of UQ Workflows in Biomedicine

UQ-Integrated Biomedical Research Workflow

Diagram 1: UQ workflow for biomedical research.

Diagram 2: Uncertainty sources affecting clinical decisions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical UQ Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in UQ Studies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality nucleic acids for genomic biomarker studies; lot-to-lot variability contributes to measurement uncertainty. | Genetic biomarker discovery in MND using cell-free DNA [14]. |

| ELISA Assay Kits | Quantify protein biomarker concentrations; standard curve precision directly impacts uncertainty in concentration estimates. | Validation of inflammatory protein biomarkers in patient serum [14]. |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Enrich for vesicles from biofluids; isolation efficiency affects downstream analysis and introduces variability. | Studying vesicle cargo as potential disease biomarkers [14]. |

| MRI Contrast Agents | Enhance tissue contrast in imaging; pharmacokinetic variability between patients affects intensity measurements. | Quantifying blood-brain barrier disruption in neurological diseases. |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Maintain consistent growth conditions; serum lot variations contribute to experimental uncertainty in cell models. | Developing in vitro models for disease mechanism studies. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Reagents | Enable high-throughput sequencing; reagent performance affects base calling quality and variant detection confidence. | Whole genome sequencing for identifying genetic risk factors [14]. |

Uncertainty quantification provides an essential framework for advancing biomedical research from exploratory science to clinical application. By systematically addressing data-related, model-related, and coupling-related uncertainties, researchers can develop more reliable diagnostic tools, biomarkers, and treatment optimization strategies. The protocols and analyses presented here demonstrate practical approaches for implementing UQ across various biomedical domains, ultimately supporting the development of more robust, clinically relevant research outcomes that can better inform patient care decisions. As biomedical models grow in complexity, integrating UQ from the initial research stages will be crucial for building trustworthiness and accelerating translation to clinical practice.

In computational modeling, particularly within biomedical and drug development research, Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) transforms model predictions from deterministic point estimates into probabilistic statements that characterize reliability. The process involves representing input parameters as random variables with specified probability distributions and propagating these uncertainties through computational models to quantify their impact on outputs. [15] [16] This forward UQ process enables researchers to compute key statistics—including means, variances, sensitivities, and quantiles—that describe the resulting probability distribution of model outputs. These statistics provide critical insights for risk assessment, decision-making, and model validation in preclinical drug development. [15] [17]

Table 1: Definitions of Key UQ Statistics

| Statistic | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation in Biomedical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | E[u_N(p)] |

Expected value of model output (e.g., average drug response) |

| Variance | E[(u_N(p) - E[u_N(p)])²] |

Spread or variability of model output around the mean |

| Median | Value m where P(u_N ≤ m) ≥ ½ and P(u_N ≥ m) ≥ ½ |

Central value where half of output distribution lies above/below |

| Quantiles | Value q where P(u_N ≥ q) ≥ 1-δ and P(u_N ≤ q) ≥ δ for δ ∈ (0,1) |

Threshold values defining probability boundaries (e.g., confidence intervals) |

| Total Sensitivity | S_T,ℐ = V(ℐ)/Var(u_N) for subset ℐ of parameters |

Fraction of output variance attributable to a parameter subset |

| Global Sensitivity | S_G,ℐ = [V(ℐ) - ∑∅≠𝒥⊂ℐV(𝒥)]/Var(u_N) |

Main effect contribution of parameters to output variance |

| Local Sensitivity | ∇u_N(p̃) at fixed parameter value p̃ |

Local rate of change of output with respect to parameter variations |

Computational Methodologies for UQ Statistics

Various computational approaches exist for estimating UQ statistics, each with distinct strengths and computational requirements. The choice of methodology depends on model complexity, computational cost per evaluation, and dimensional complexity.

Non-Intrusive Polynomial Chaos (PC) Methods

Polynomial Chaos expansions build functional approximations (emulators) that map parameter values to model outputs using orthogonal polynomials tailored to input distributions. [15] The UncertainSCI software implements modern PC techniques utilizing weighted Fekete points and leverage score sketching for near-optimal sampling. [15] Once constructed, the PC emulator enables rapid computation of output statistics without additional costly model evaluations:

- Means and moments are obtained analytically from PC coefficients

- Sensitivities are computed via variance decomposition

- Quantiles are calculated numerically by sampling the cheap-to-evaluate emulator [15]

Sampling-Based Approaches

Monte Carlo (MC) and Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) methods propagate input uncertainties by evaluating the computational model at numerous sample points. [16] While conceptually straightforward, these methods typically require thousands of model evaluations to achieve statistical convergence. Advanced variants include:

- Multifidelity Monte Carlo (MFMC): Uses control variates from low-fidelity models to reduce estimator variance, accelerating mean estimation by almost four orders of magnitude compared to standard MC. [18]

- Importance Sampling: Preferentially places samples in important regions (e.g., near failure boundaries) to efficiently estimate rare event probabilities. [16]

- Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC): Employed for Bayesian data assimilation in dynamical systems like epidemiological ABMs, enabling parameter estimation with streaming data. [19]

Stochastic Expansion Methods

Beyond PC, other expansion techniques include Stochastic Collocation (SC) and Functional Tensor Train (FTT), which form functional approximations between inputs and outputs. [16] These methods provide analytic response moments and variance-based sensitivity metrics, with PDFs/CDFs computed numerically by sampling the expansion.

Diagram 1: UQ Statistical Analysis Workflow

Experimental Protocols for UQ Analysis

Protocol: Polynomial Chaos-Based UQ Analysis

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing non-intrusive polynomial chaos expansion for uncertainty quantification in computational models, adapted from UncertainSCI methodology. [15]

Research Reagent Solutions:

- UncertainSCI Python Suite: Open-source software for building PC emulators with near-optimal sampling strategies [15]

- Parameter Distributions: Probability distributions characterizing input uncertainties (normal, uniform, beta, etc.) [16]

- Forward Model: Existing computational simulation code (e.g., bioelectric cardiac models, drug response models)

- Sampling Ensemble: Set of parameter values determined via weighted Fekete points or randomized subsampling

Procedure:

- Parameter Distribution Specification

- Define probabilistic input parameters

p = (p₁, p₂, ..., p_d)with joint distributionμ - Select appropriate polynomial basis functions orthogonal to input distributions (e.g., Hermite for normal, Legendre for uniform)

- Define probabilistic input parameters

Experimental Design Generation

- Generate parameter sample ensemble

{p^(1), p^(2), ..., p^(N)}using weighted Fekete points - Utilize leverage score sketching for near-optimal sampling in high-dimensional spaces

- Generate parameter sample ensemble

Forward Model Evaluation

- Execute computational model at each parameter sample:

u(p^(i))fori = 1, ..., N - Collect output responses, potentially including field values in high-dimensional spaces

- Execute computational model at each parameter sample:

Polynomial Chaos Emulator Construction

- Solve for PC expansion coefficients using regression or projection methods

- Build surrogate model:

u_N(p) = ∑_{α∈Λ} c_α Ψ_α(p)whereΨ_αare multivariate orthogonal polynomials

Statistical Quantification

- Compute mean from zeroth-order coefficient:

E[u_N] ≈ c_0 - Calculate variance from higher-order coefficients:

Var(u_N) ≈ ∑_{α≠0} c_α² - Determine sensitivity indices via Sobol' decomposition of variance

- Estimate quantiles by sampling the PC surrogate and computing empirical quantiles

- Compute mean from zeroth-order coefficient:

Validation and Error Assessment

- Compare emulator predictions with additional forward model evaluations

- Assess convergence of statistical estimates with increasing sample size

Protocol: Multifidelity Global Sensitivity Analysis

This protocol describes the Multifidelity Global Sensitivity Analysis (MFGSA) method for efficiently computing variance-based sensitivity indices, leveraging both high-fidelity and computationally cheaper low-fidelity models. [18]

Research Reagent Solutions:

- High-Fidelity Model: Accurate but computationally expensive computational model

- Low-Fidelity Models: Approximate models with correlated outputs but reduced computational cost

- MFGSA MATLAB Toolkit: Open-source implementation for multifidelity sensitivity analysis [18]

- Correlation Assessment: Methods to quantify output correlation between model fidelities

Procedure:

- Model Fidelity Characterization

- Identify computational costs for each model fidelity:

C_1, C_2, ..., C_KwhereC_1is high-fidelity cost - Quantify correlation structure between model outputs across fidelities

- Identify computational costs for each model fidelity:

Optimal Allocation Design

- Determine optimal number of evaluations for each model fidelity to minimize estimator variance

- Allocate computational budget according to relative costs and correlations

Multifidelity Sampling

- Generate input samples according to specified parameter distributions

- Evaluate both high-fidelity and low-fidelity models at allocated sample counts

Control Variate Estimation

- Form multifidelity estimators for variance components using low-fidelity models as control variates

- Compute corrected estimates that leverage correlations between model outputs

Sensitivity Index Calculation

- Calculate main effect (first-order) sensitivity indices:

S_i = Var[E[Y|X_i]]/Var[Y] - Compute total effect indices:

S_Ti = E[Var[Y|X_~i]]/Var[Y]whereX_~idenotes all parameters exceptX_i - Rank parameters by contribution to output uncertainty

- Calculate main effect (first-order) sensitivity indices:

Variance Reduction Assessment

- Compare statistical precision of MFGSA with traditional single-fidelity approaches

- Quantify computational speed-up achieved through multifidelity framework

Table 2: UQ Method Selection Guide

| Method | Optimal Use Case | Computational Cost | Key Statistics | Implementation Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion | Smooth parameter dependencies, moderate dimensions | 50-500 model evaluations [15] | Means, variances, sensitivities, quantiles [15] | UncertainSCI [15], UQLab [20] |

| Multifidelity Monte Carlo | Models with correlated low-fidelity approximations | 10-1000x acceleration over MC [18] | Means, variances, sensitivity indices [18] | MFMC MATLAB Toolbox [18] |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling | General purpose, non-smooth responses | 100s-1000s model evaluations [16] | Full distribution statistics | Dakota [16] |

| Sequential Monte Carlo | Dynamic systems with streaming data | Varies with state dimension | Time-varying parameter distributions | Custom Jax implementations [19] |

| Importance Sampling | Rare event probability estimation | More efficient than MC for rare events | Failure probabilities, risk metrics | Dakota [16] |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Uncertainty quantification statistics play critical roles in various biomedical applications, from preclinical drug development to clinical treatment planning.

Preclinical Drug Efficacy Assessment

In preclinical drug development, UQ statistics quantify confidence in therapeutic efficacy predictions. For example, in rodent pain models assessing novel analgesics, UQ can determine how parameter uncertainties (e.g., dosage timing, bioavailability) affect predicted pain reduction metrics. [17] Variance-based sensitivity indices identify which pharmacological parameters contribute most to variability in efficacy outcomes, guiding experimental refinement.

Bioelectric Field Modeling

In computational models of bioelectric phenomena (e.g., cardiac potentials or neuromodulation), UQ statistics quantify how tissue property variations affect simulation results. [15] Mean and variance estimates characterize expected ranges of induced electric fields, while quantiles define safety thresholds for medical devices. Sensitivity analysis reveals critical parameters requiring precise measurement.

Diagram 2: UQ in Biomedical Decision Support

Disease Model Calibration

For epidemiological models of disease transmission, UQ statistics facilitate model calibration to observational data. [19] Sequential Monte Carlo methods assimilate streaming infection data to update parameter distributions, with mean estimates providing expected disease trajectories and quantiles defining confidence envelopes for public health planning. Sensitivity analysis identifies dominant factors controlling outbreak dynamics.

The comprehensive quantification of means, variances, sensitivities, and quantiles provides the statistical foundation for credible computational predictions in drug development and biomedical research. These UQ statistics transform deterministic simulations into probabilistic forecasts with characterized reliability, enabling evidence-based decision-making under uncertainty. Modern computational frameworks like UncertainSCI, Dakota, and multifidelity methods make sophisticated UQ analysis accessible to researchers, supporting robust preclinical assessment and therapeutic development. As computational models grow increasingly complex, the rigorous application of these UQ statistical measures will remain essential for translating in silico predictions into real-world biomedical insights.

Parametric Uncertainty Quantification (Parametric UQ) is a fundamental process in computational modeling that involves treating uncertain model inputs as random variables with defined probability distributions and propagating this uncertainty through the model to quantify its impact on outputs [21]. This approach replaces the traditional deterministic modeling paradigm, where inputs and outputs are fixed values, with a probabilistic framework that provides a more comprehensive understanding of system behavior and model predictions. In fields such as drug development and physiological modeling, this is particularly crucial as model parameters often exhibit uncertainty due to measurement limitations and natural physiological variability [21].

The process consists of two primary stages: Uncertainty Characterization (UC), which involves quantifying uncertainty in model inputs by determining appropriate probability distributions, and Uncertainty Propagation (UP), which calculates the resultant uncertainty in model outputs by propagating the input uncertainties through the model [21]. This probabilistic approach enables researchers to assess the robustness of model predictions, identify influential parameters, and make more informed decisions that account for underlying uncertainties.

Key Methodological Approaches

Parametric UQ employs several computational techniques, each with distinct strengths and applications. The table below summarizes the primary methods used in computational modeling research:

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches for Parametric Uncertainty Quantification

| Method | Core Principle | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Uses repeated random sampling from input distributions to compute numerical results [22] [23] | Project forecasting, risk analysis, financial modeling, physiological systems [21] [23] | Handles nonlinear and complex systems; conceptually straightforward; parallelizable [22] | Computationally intensive (convergence rate: N⁻¹/²); requires many model evaluations [22] |

| Sensitivity Analysis (Sobol Method) | Variance-based global sensitivity analysis that decomposes output variance into contributions from individual inputs and interactions [24] | Factor prioritization, model simplification, identification of key drivers of uncertainty [25] | Quantifies both individual and interactive effects; model-independent; provides global sensitivity measures [24] [25] | Computationally demanding; complexity increases with dimensionality [24] |

| Bayesian Inference with Surrogate Models | Combines prior knowledge with observed data using Bayes' theorem; often uses surrogate models (Gaussian Processes, PCE) to approximate complex systems [26] [27] | Parameter estimation for complex models with limited data; clinical decision support systems [27] | Incorporates prior knowledge; provides full posterior distributions; quantifies epistemic uncertainty [27] | Computationally challenging for high-dimensional problems; requires careful prior specification [27] |

| Conformal Prediction | Distribution-free framework that provides finite-sample coverage guarantees without strong distributional assumptions [28] | Uncertainty quantification for generative AI, human-AI collaboration, changepoint detection [28] | Provides distribution-free guarantees; valid under mild exchangeability assumptions; computationally efficient [28] | Requires appropriate score functions; confidence sets may be uninformative with poor scores [28] |

Advanced and Hybrid Approaches

Recent methodological advances have focused on increasing computational efficiency and expanding applications to complex systems. Physics-Informed Neural Networks with Uncertainty Quantification (PINN-UU) integrate the space-time domain with uncertain parameter spaces within a unified computational framework, demonstrating particular value for systems with scarce observational data, such as subsurface water bodies [26]. Similarly, conformal prediction methods have been extended to generative AI settings through frameworks like Conformal Prediction with Query Oracle (CPQ), which connects conformal prediction with the classical missing-mass problem to provide coverage guarantees for black-box generative models [28].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol: Variance-Based Global Sensitivity Analysis Using Sobol Method

Table 2: Key Parameters for Variance-Based Sensitivity Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Typical Settings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order Sobol Index (Sᵢ) | Measures the contribution of a single input parameter to the output variance [24] | Range: 0 to 1 | Values near 1 indicate parameters that dominantly control output uncertainty [24] |

| Total Sobol Index (Sₜ) | Measures the overall contribution of an input parameter, including both individual effects and interactions with other variables [24] | Range: 0 to 1 | Reveals parameters involved in interactions; Sₜ ≫ Sᵢ indicates significant interactive effects [24] |

| Sample Size (N) | Number of model evaluations required | Typically 1,000-10,000 per parameter | Convergence should be verified by increasing sample size [24] |

| Sampling Method | Technique for generating input samples | Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [24] | LHS provides more uniform coverage of parameter space than random sampling [24] |

Workflow Implementation:

Define Input Distributions: For each uncertain parameter, specify a probability distribution representing its uncertainty (e.g., normal, uniform, log-normal) based on experimental data or expert opinion [21].

Generate Sample Matrix: Create two independent sampling matrices (A and B) of size N × k, where N is the sample size and k is the number of parameters, using Latin Hypercube Sampling [24].

Construct Resampling Matrices: Create a set of matrices where each parameter in A is replaced sequentially with the corresponding column from B, resulting in k additional matrices.

Model Evaluation: Run the computational model for all sample points in matrices A, B, and the resampling matrices, recording the output quantity of interest for each evaluation.

Calculate Sobol Indices: Compute first-order and total Sobol indices using variance decomposition formulas:

- First-order index: ( Si = \frac{V[E(Y|Xi)]}{V(Y)} )

- Total index: ( S{Ti} = 1 - \frac{V[E(Y|X{-i})]}{V(Y)} ) where ( V[E(Y|X_i)] ) is the variance of the conditional expectation [24].

Interpret Results: Parameters with high first-order indices (( Si > 0.1 )) are primary drivers of output uncertainty and should be prioritized for further measurement. Parameters with low total indices (( S{Ti} < 0.01 )) can potentially be fixed at nominal values to reduce model complexity [25].

Figure 1: Workflow for Variance-Based Global Sensitivity Analysis

Protocol: Consistent Monte Carlo Uncertainty Propagation

Principle: In distributed or sequential uncertainty analyses, consistent Monte Carlo methods must preserve dependencies of random variables by ensuring the same sequence is used for a particular quantity regardless of how many times or where it appears in the analysis [22].

Implementation Requirements:

Unique Stream Identification: Assign a unique random number stream to each uncertain input variable in the system, maintained across all computational processes and analysis stages.

Seed Management: Implement a reproducible seeding strategy that ensures identical sequences are regenerated for the same input variables in subsequent analyses.

Dependency Tracking: Maintain a mapping between input variables and their corresponding sample sequences, particularly when reusing previously computed quantities in further analyses.

Validation Step: To verify consistency, compute the sample variance of a composite function ( Z = h(X, Y) ) where ( Y = g(X) ), ensuring that the same sequence ( {xn}{n=1}^N ) is used in both evaluations. Inconsistent sampling, where independent sequences are used for the same variable, will produce biased variance estimates [22].

Protocol: Probability of Success Assessment in Drug Development

Table 3: Probability of Success Assessment Framework

| Component | Description | Data Sources | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Prior | Probability distribution capturing uncertainty in effect size for phase III [29] | Phase II data, expert elicitation, real-world data, historical clinical trials [29] | Critical for go/no-go decisions at phase II/III transition [29] |

| Predictive Power | Probability of rejecting null hypothesis given design prior [29] | Phase II endpoint data, association between biomarker and clinical outcomes [29] | Sample size determination for confirmatory trials [29] |

| Assurance | Bayesian equivalent of power using mixture prior distributions [29] | Combination of prior beliefs and current trial data [29] | Incorporating historical information into trial planning [29] |

Implementation Workflow:

Define Success Criteria: Specify the target product profile, including minimum acceptable and ideal efficacy results required for regulatory approval and reimbursement [29].

Construct Design Prior: Develop a probability distribution for the treatment effect size in phase III, incorporating phase II data on the primary endpoint. When phase II uses biomarker or surrogate outcomes, leverage external data (e.g., real-world data, historical trials) to establish relationship with clinical endpoints [29].

Calculate Probability of Success: Compute the probability of demonstrating statistically significant efficacy in phase III, integrating over the design prior to account for uncertainty in the true effect size [29].

Decision Framework: Use the computed probability of success to inform portfolio management decisions, with typical thresholds ranging from 65-80% for progression to phase III, depending on organizational risk tolerance and development costs [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Parametric UQ

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Algorithms | Sobol Method | Variance-based sensitivity analysis quantifying parameter contributions to output uncertainty [24] | Implemented in UQ modules of COMSOL, SAS, R packages (sensitivity) [24] |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) | Surrogate modeling for efficient uncertainty propagation and sensitivity analysis [24] | Adaptive PCE automates surrogate model creation; direct Sobol index computation [24] | |

| Gaussian Process Emulators | Bayesian surrogate models for computationally intensive models [27] | Accelerates model calibration; enables UQ for complex models in clinically feasible timeframes [27] | |

| Conformal Prediction | Distribution-free uncertainty quantification with finite-sample guarantees [28] | Applied to generative AI, changepoint detection; requires appropriate score functions [28] | |

| Software Tools | COMSOL UQ Module | Integrated platform for screening, sensitivity analysis, and reliability analysis [24] | Provides built-in Sobol method, LHS sampling, and automated surrogate modeling [24] |

| Kanban Monte Carlo Tools | Project forecasting incorporating uncertainty and variability [23] | Uses historical throughput data for delivery date and capacity predictions [23] | |

| Data Resources | Real-World Data (RWD) | Informs design priors for probability of success calculations [29] | Patient registries, historical controls; improves precision of phase III effect size estimation [29] |

| Historical Clinical Trial Data | External data for biomarker-endpoint relationships [29] | Quantifies association between phase II biomarkers and phase III clinical endpoints [29] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Biomedical Research

Temporal Distribution Shifts in Pharmaceutical Data

Real-world pharmaceutical data often exhibits significant temporal distribution shifts that impact the reliability of UQ methods. A comprehensive evaluation of QSAR models under realistic temporal shifts revealed:

- Magnitude Connection: The extent of distribution shift correlates strongly with the nature of the assay, with some assays showing pronounced shifts in both label and descriptor space over time [30].

- Performance Impairment: Pronounced distribution shifts impair the performance of popular UQ methods used in QSAR models, highlighting the challenge of identifying techniques that remain reliable under real-world data conditions [30].

- Calibration Impact: Temporal shifts significantly impact post hoc calibration of uncertainty estimates, necessitating regular reassessment and adjustment of UQ approaches throughout model deployment [30].

Cardiac Electrophysiology Models

Comprehensive UQ/SA in cardiac electrophysiology models demonstrates the feasibility of robust uncertainty assessment for complex physiological systems:

- Robustness Demonstration: Action potential simulations can be fully robust to low levels of parameter uncertainty, with a range of emergent dynamics (including oscillatory behavior) observed at larger uncertainty levels [21].

- Influential Parameter Identification: Comprehensive analysis revealed that five key parameters were highly influential in producing abnormal dynamics, providing guidance for targeted parameter measurement and model refinement [21].

- Model Failure Analysis: The framework enables systematic analysis of different behaviors that occur under parameter uncertainty, including "model failure" modes, enhancing model reliability in safety-critical applications [21].

Figure 2: Parametric UQ Methodologies and Research Applications

Pulmonary Hemodynamics Modeling

Bayesian parameter inference with Gaussian process emulators enables efficient UQ for complex physiological systems:

- Clinical Timeframes: GP emulators accelerate model calibration, enabling estimation of microvascular parameters and their uncertainties within clinically feasible timeframes [27].

- Disease Correlation: In chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), changes in inferred parameters strongly correlate with disease severity, particularly in lungs with more advanced disease [27].

- Heterogeneous Adaptation: CTEPH leads to heterogeneous microvascular adaptation reflected in distinct parameter shifts, enabling more targeted treatment strategies [27].

Parametric UQ, through modeling inputs as random variables, provides an essential framework for robust computational modeling in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. The methodologies outlined—from variance-based sensitivity analysis to consistent Monte Carlo approaches and Bayesian inference—offer structured protocols for implementing comprehensive uncertainty assessment. Particularly in drug development, where resources are constrained and decisions carry significant consequences, these approaches enable more informed decision-making by explicitly quantifying and propagating uncertainty through computational models. The integration of real-world data and advanced computational techniques continues to enhance the applicability and reliability of parametric UQ across the biomedical domain, supporting the development of more credible and clinically relevant computational models.

UQ's Role in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)