Validation Metrics for Continuous Variables: A 2025 Guide for Robust Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and interpreting validation metrics for continuous variables in biomedical and clinical research.

Validation Metrics for Continuous Variables: A 2025 Guide for Robust Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for selecting, applying, and interpreting validation metrics for continuous variables in biomedical and clinical research. Tailored for scientists and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational statistical theory with practical application, covering essential parametric tests, advanced measurement systems like Gage R&R, data quality best practices, and modern digital validation trends. Readers will gain the knowledge to ensure data integrity, optimize analytical processes, and make statistically sound decisions in regulated environments.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Continuous Data and Validation

In the context of validation metrics for continuous variables research, understanding the fundamental nature of continuous data is paramount. Continuous data represent measurements that can take on any value within a given range, providing an infinite number of possible values and allowing for meaningful division into smaller increments, including fractional and decimal values [1]. This contrasts with discrete data, which consists of distinct, separate values that are counted. In scientific and drug development research, common examples of continuous data include blood pressure measurements, ejection fraction, laboratory values (e.g., cholesterol), angiographic variables, weight, temperature, and time [2] [3].

The power of continuous data lies in the depth of insight it provides. Researchers can draw conclusions with smaller sample sizes compared to discrete data and employ a wider variety of analytical techniques [3]. This rich information allows for more accurate predictions and deeper insights, which is particularly valuable in fields like drug development where precise measurements can determine treatment efficacy and safety. The fluid nature of continuous data captures the subtle nuances of biological systems in a way that discrete data points cannot, making it indispensable for robust validation metrics.

Measures of Central Tendency: Mean, Median, and Mode

Measures of central tendency are summary statistics that represent the center point or typical value of a dataset. The three most common measures are the mean, median, and mode, each with a distinct method of calculation and appropriate use cases within research on continuous variables [4] [5].

Definitions and Calculations

- Mean (μ or x̄): The arithmetic average, calculated as the sum of all values divided by the number of values in the dataset (Σx/n) [4] [5]. The mean includes every value in your data set as part of the calculation and is the value that produces the lowest amount of error from all other values in the data set [4].

- Median: The middle value that separates the greater and lesser halves of a dataset. To find it, data is ordered from smallest to largest. For an odd number of observations, it is the middle value; for an even number, it is the average of the two middle values [4] [5].

- Mode: The value that appears most frequently in a dataset [6]. For continuous data in its raw form, the mode is often unusable as no two values may be exactly the same. A common practice is to discretize the data into intervals, as in a histogram, and define the mode as the midpoint of the interval with the highest frequency [6].

Comparative Analysis: Mean vs. Median

The choice between mean and median is critical and depends heavily on the distribution of the data, a key consideration when establishing validation metrics.

Table 1: Comparison of Mean and Median as Measures of Central Tendency

| Characteristic | Mean | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Arithmetic average | Middle value in an ordered dataset |

| Effect of Outliers | Highly sensitive; pulled strongly in the direction of the tail [5] | Robust; resistant to the influence of outliers and skewed data [4] [5] |

| Data Utilization | Incorporates every value in the dataset [4] | Depends only on the middle value(s) [5] |

| Best Used For | Symmetric distributions (e.g., normal distribution) [4] [5] | Skewed distributions [4] [5] |

| Typical Data Reported | Mean and Standard Deviation (SD) [2] | Median and percentiles (e.g., 25th, 75th) or range [2] |

In a perfectly symmetrical, unimodal distribution (like the normal distribution), the mean, median, and mode are all identical [4] [6]. However, in skewed distributions, these measures diverge. The mean is dragged in the direction of the skew by the long tail of outliers, while the median remains closer to the majority of the data [4] [5]. A classic example is household income, which is typically right-skewed (a few very high incomes); in such cases, the median provides a better representation of the "typical" income than the mean [5].

Assessing Data Distribution and Its Implications

The distribution of data is a foundational concept that directly influences the choice of descriptive statistics and inferential tests. For continuous data, the most frequently assessed distribution is the normal distribution (bell curve), which is symmetric and unimodal [2].

Normality Assessment Workflow

Determining whether a continuous variable is normally distributed is a crucial step in selecting the correct analytical pathway. The following diagram outlines the key steps and considerations in this process.

Methodologies for Normality Testing

As shown in the workflow, assessing normality involves both graphical and formal statistical methods, which are integral to robust experimental protocols:

- Graphical Methods: Visual examination of data is a primary step. Researchers can use histograms to see if the data resembles a bell-shaped curve, box plots to assess symmetry and identify outliers, and Q-Q plots (Quantile-Quantile plots) where data points aligning closely with the diagonal line suggest normality [2].

- Statistical Tests: Formal hypothesis tests provide an objective measure. Commonly used tests include the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Shapiro-Wilk test [2]. A p-value greater than the significance level (e.g., > 0.05) in these tests suggests that the data does not significantly deviate from a normal distribution.

Statistical Significance Testing for Continuous Data

Once the distribution is understood, researchers can select appropriate tests to determine statistical significance—the probability that an observed effect is not due to random chance alone.

Hypothesis Testing Framework

The foundation of these tests is the null hypothesis (H₀), which typically states "there is no difference" between groups or "no effect" of a treatment. The alternative hypothesis (H₁) states that a difference or effect exists. The p-value quantifies the probability of obtaining the observed results if the null hypothesis were true. A p-value less than a pre-defined significance level (alpha, commonly 0.05) provides evidence to reject the null hypothesis [2].

Guide to Selecting Statistical Tests

The choice of statistical test is dictated by the number of groups being compared and the distribution of the continuous outcome variable.

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Comparing Continuous Variables

| Number of Groups | Group Relationship | Parametric Test (Data ~Normal) | Non-Parametric Test (Data ~Non-Normal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| One Sample | - | One-sample t-test [7] | One-sample sign test or median test [7] |

| Two Samples | Independent (Unpaired) | Independent (unpaired) two-sample t-test [2] [7] | Mann-Whitney U test [7] |

| Two Samples | Dependent (Paired) | Paired t-test [2] [7] | Wilcoxon signed-rank test [7] |

| Three or More Samples | Independent (Unpaired) | One-way ANOVA [2] [7] | Kruskal-Wallis test [7] |

| Three or More Samples | Dependent (Paired) | Repeated measures ANOVA [7] | Friedman test [7] |

Key Assumptions and Applications

- T-test: A commonly used parametric test to compare means. Its assumptions include: data derived from a normally distributed population, for two-sample tests the populations must have equal variances, and all measurements must be independent [2]. It is used to compare a sample mean to a theoretical value (one-sample), compare means from two related groups (paired), or compare means from two independent groups (independent) [2].

- ANOVA (Analysis of Variance): Used to test for differences among three or more group means, extending the capability of the t-test. Using multiple t-tests for more than two groups increases the probability of a Type I error (falsely rejecting the null hypothesis), which ANOVA controls [2]. A significant ANOVA result (p < 0.05) indicates that not all group means are equal, but it does not specify which pairs differ, necessitating a post-hoc test (e.g., Tukey's test) for further investigation [7].

- Non-Parametric Tests: These are used when data violates the normality assumption, particularly with small sample sizes or ordinal data. They are typically based on ranks of the data rather than the actual values and are thus less powerful than their parametric counterparts but more robust to outliers and non-normality [2] [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Continuous Data Analysis

Successfully analyzing continuous data in validation studies requires more than just statistical knowledge; it involves a suite of conceptual and practical tools.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Analyzing Continuous Variables

| Tool or Concept | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Measures of Central Tendency | To summarize the typical or central value in a dataset (Mean, Median, Mode) [4] [5]. |

| Measures of Variability | To quantify the spread or dispersion of data points (e.g., Standard Deviation, Range, Interquartile Range) [2]. |

| Normality Tests | To objectively assess if data follows a normal distribution, guiding test selection (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk test) [2]. |

| Data Visualization Software | To create histograms, box plots, and Q-Q plots for visual assessment of distribution and outliers [8]. |

| Statistical Software | To perform complex calculations for hypothesis tests (e.g., R, SPSS, Python with SciPy/Statsmodels) [7]. |

| Tolerance Intervals / Capability Analysis | To understand the range where a specific proportion of the population falls and to assess process performance against specification limits, respectively [3]. |

The rigorous analysis of continuous data forms the bedrock of validation metrics in scientific and drug development research. A meticulous approach that begins with visualizing and understanding the data distribution, followed by the informed selection of descriptive statistics (mean vs. median) and inferential tests (parametric vs. non-parametric), is critical for drawing valid and reliable conclusions. By adhering to this structured methodology—assessing normality, choosing robust measures of central tendency, and applying the correct significance tests—researchers can ensure their findings accurately reflect underlying biological phenomena and support the development of safe and effective therapeutics.

The Critical Role of Validation in Research and Regulated Environments

Validation provides the critical foundation for trust and reliability in both research and regulated industries. It encompasses the processes, tools, and metrics used to ensure that systems, methods, and data consistently produce results that are fit for their intended purpose. In 2025, validation has become more business-critical than ever, with teams facing increasing scrutiny from regulators and growing complexity in global regulatory requirements [9]. The validation landscape is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the adoption of digital tools, evolving regulatory priorities, and the need to manage more complex workloads with limited resources.

This transformation is particularly evident in life sciences and clinical research, where proper validation is essential for ensuring data integrity, patient safety, and compliance with Good Clinical Practices (GCP) and FDA 21 CFR Part 11 [10]. Without rigorous validation, clinical data may be compromised, resulting in delays, increased costs, and potentially jeopardizing patient safety. The expanding scale of regulatory change presents a formidable challenge, with over 40,000 individual regulatory items issued at federal and state levels annually, requiring organizations to identify, analyze, and determine applicability to their business operations [11].

Current Challenges in Validation

Validation teams in 2025 face a complex set of challenges that reflect the increasing demands of regulatory environments and resource constraints.

Primary Validation Team Challenges

A comprehensive analysis of the validation landscape reveals three dominant challenges that teams currently face [9] [12]:

Audit Readiness: For the first time in four years, audit readiness has emerged as the top challenge for validation teams, surpassing compliance burden and data integrity. Organizations are now expected to demonstrate a constant state of preparedness as global regulatory requirements grow more complex [9] [12].

Compliance Burden: The expanding regulatory landscape creates significant compliance obligations, with firms across insurance, securities, and investment sectors facing a steady stream of new requirements fueled by shifting federal priorities, proactive state legislatures, and emerging risks tied to climate, technology, and cybersecurity [11].

Data Integrity: Ensuring the accuracy and consistency of data throughout its lifecycle remains a fundamental challenge, particularly as organizations adopt more complex digital systems and face increased scrutiny from regulatory bodies [9].

Resource Constraints and Workload Pressures

Compounding these challenges, validation teams operate with limited resources while managing increasing workloads [12]:

Lean Team Structures: 39% of companies report having fewer than three dedicated validation staff, despite increasingly complex regulatory workloads [9] [12].

Growing Workloads: 66% of organizations report that their validation workload has increased over the past 12 months, creating significant pressure on already constrained resources [9] [12].

Strategic Outsourcing: 70% of companies now rely on external partners for at least some portion of their validation work, with 25% of organizations outsourcing more than a quarter of their validation activities [12].

Table 1: Primary Challenges Facing Validation Teams in 2025

| Rank | Challenge | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Readiness | Maintaining constant state of preparedness for regulatory inspections |

| 2 | Compliance Burden | Managing complex and evolving regulatory requirements |

| 3 | Data Integrity | Ensuring accuracy and consistency of data throughout its lifecycle |

Table 2: Validation Team Resource Constraints

| Constraint Type | Statistic | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Small Team Size | 39% of companies have <3 dedicated validation staff | Limited capacity for complex workloads |

| Increased Workload | 66% report year-over-year workload increase | Resource strain and potential burnout |

| Outsourcing Dependence | 70% use external partners for some validation work | Need for specialized expertise access |

Digital Transformation in Validation

The adoption of Digital Validation Tools (DVTs) represents a fundamental shift in how organizations approach validation, with 2025 marking a tipping point for the industry.

Adoption Trends and Benefits

Digital validation systems have seen remarkable adoption rates, with the number of organizations using these tools jumping from 30% to 58% in just one year [9]. Another 35% of organizations are planning to adopt DVTs in the next two years, meaning nearly every organization (93%) is either using or actively planning to use digital validation tools [9]. This massive shift is driven by the substantial advantages these systems offer, including centralized data access, streamlined document workflows, support for continuous inspection readiness, and enhanced efficiency, consistency, and compliance across validation programs [9].

Survey respondents specifically cited data integrity and audit readiness as the two most valuable benefits of digitalizing validation, directly addressing the top challenges facing validation teams [9]. The move toward digital validation is part of a broader industry transformation that includes the adoption of advanced strategies such as automated testing, continuous validation, risk-based validation, and AI-driven analytics [10].

Advanced Validation Strategies for 2025

Several advanced approaches are enhancing validation processes in 2025 and beyond [10]:

Automated Testing and Validation Tools: Automation streamlines repetitive tasks, improves accuracy, and ensures consistency while accelerating validation cycles. Automated validation frameworks can generate test cases based on User Requirements Specification documents, execute tests across different environments, and produce detailed reports [10].

Continuous Validation (CV) Approach: This strategy integrates validation into the software development lifecycle (SDLC), ensuring that each new feature or update undergoes validation in real-time. This proactive approach minimizes the risk of errors and reduces the need for large-scale re-validation efforts [10].

Risk-Based Validation (RBV): This methodology focuses resources on high-risk areas, allowing organizations to allocate their efforts strategically. In electronic systems, modules dealing with patient randomization, adverse event reporting, and electronic signatures typically warrant extensive validation, while lower-risk elements may undergo lighter validation [10].

AI and Machine Learning Integration: Artificial intelligence tools can analyze large datasets for anomalies, identify discrepancies, and predict potential errors. AI-driven analytics enhance data integrity by flagging irregularities that may escape manual review and can automate audit trail reviews and compliance reporting [10].

Table 3: Digital Validation Tool Adoption Trends

| Adoption Stage | Percentage of Organizations | Key Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Currently Using DVTs | 58% | Audit readiness and data integrity |

| Planning to Adopt (Next 2 Years) | 35% | Efficiency and compliance needs |

| Total Engaged with DVTs | 93% | Industry tipping point reached |

Validation Metrics and Methodologies

Robust validation requires appropriate metrics and methodologies to ensure systems perform as intended across various applications and use cases.

Validation Metrics for Clinical Research Hypotheses

In clinical research, validated metrics provide standardized, consistent, and systematic measurements for evaluating scientific hypotheses. Recent research has developed both brief and comprehensive versions of evaluation instruments [13]:

The brief version of the instrument contains three core dimensions:

- Validity: Assesses clinical validity and scientific validity

- Significance: Evaluates established medical needs, impact on future direction of the field, effect on target population, and cost-benefit considerations

- Feasibility: Examines required costs, needed time, and scope of work

The comprehensive version includes these three dimensions plus additional criteria:

- Novelty: Leads to innovation in medical practice, new methodologies for clinical research, alteration of previous findings, novel medical knowledge, or incremental new findings

- Clinical Relevance: Impact on current clinical practice, medical knowledge, and health policy

- Potential Benefits and Risks: Significant benefits, tolerable risks, and overall risk-benefit balance

- Ethicality: Absence of ethical concerns, willingness to participate if eligible, and overall ethical study design

- Testability: Ability to be tested in ideal settings with adequate patient population

- Interestingness: Personal interest and potential for collaboration

- Clarity: Clear purposes, focused groups, specified variables, and defined relationships among variables

Each evaluation dimension includes 2 to 5 subitems that assess specific aspects, with the brief and comprehensive versions containing 12 and 39 subitems respectively. Each subitem uses a 5-point Likert scale for consistent assessment [13].

Machine Learning Validation Metrics

For machine learning applications, different evaluation metrics are used depending on the specific task [14]:

Binary Classification: Common metrics include accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, precision, F1-score, Cohen's kappa, and Matthews' correlation coefficient (MCC). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC) provide threshold-independent evaluation [14].

Multi-class Classification: Approaches include macro-averaging (calculating metrics separately for each class then averaging) and micro-averaging (computing metrics from aggregate sums across all classes) [14].

Regression: Continuous variables are analyzed using methods like linear regression and artificial neural networks, with cross-validation being essential for ensuring robustness of discovered patterns [15].

Statistical Considerations for Continuous Variables

The analysis of continuous variables requires particular methodological care. Categorizing continuous variables by grouping values into two or more categories creates significant problems, including considerable loss of statistical power and incomplete correction for confounding factors [16]. The use of data-derived "optimal" cut-points can lead to serious bias and should be tested on independent observations to assess validity [16].

Research demonstrates that 100 continuous observations are statistically equivalent to at least 157 dichotomized observations, highlighting the efficiency loss caused by categorization [16]. Furthermore, statistical models with a categorized exposure variable remove only 67% of the confounding controlled when the continuous version of the variable is used [16].

Digital vs Traditional Validation Workflow

Validation in Practice: Applications and Protocols

REDCap Validation in Clinical Research

REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is widely adopted for its flexibility and capacity to manage complex clinical trial data, but requires thorough validation to ensure consistent and reliable performance [10]. The validation process involves several key components:

- User Requirements Specification (URS): Details all functional and non-functional requirements, including data entry forms, workflows, and reporting capabilities

- Risk Assessment: Identifies potential threats to data integrity, patient safety, and regulatory compliance

- Functional Testing: Rigorous examination of each module to ensure specified requirements are met

- Performance Testing: Simulates high-load conditions to verify system can handle large datasets and concurrent users

- Security Validation: Verifies role-based access controls, encryption mechanisms, and audit trails

- Data Migration Testing: Validates integrity of transferred data when migrating from legacy systems

- Audit Trail Review: Confirms all data modifications are logged accurately

- Change Control: Ensures system updates do not compromise validation status [10]

Shiny App Validation in Regulated Environments

Shiny applications present unique validation challenges due to their stateful, interactive, and user-driven nature [17]. Practical validation strategies include:

- Modular Code: Keeping UI and logic separate to enhance maintainability and testability

- Version Control: Using tools like Git to maintain environmental snapshots and track changes

- Comprehensive Testing: Implementing unit tests with

testthatand end-to-end tests withshinytest2 - Environment Management: Using

renvor Docker to freeze environments and ensure consistency - Input Validation: Restricting and validating user inputs to prevent errors

- Comprehensive Logging: Implementing audit trails to track user actions and input history [17]

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) Validation

The validation of New Approach Methodologies represents an emerging frontier, with initiatives like the Complement-ARIE public-private partnership aiming to accelerate the development and evaluation of NAMs for chemical safety assessments [18]. This collaboration focuses on:

- Establishing criteria for selecting specific NAMs for validation

- Obtaining community input on NAMs that meet readiness criteria

- Developing comprehensive procedures and protocols to transparently evaluate and document the robustness of NAMs [18]

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Validation Platforms | Automated test execution and documentation | Pharmaceutical manufacturing |

| testthat R Package | Unit testing for code validation | Shiny application development |

| shinytest2 | End-to-end testing for interactive applications | Shiny application validation |

| renv | Environment reproducibility management | Consistent validation environments |

| riskmetric | Package-level risk assessment | R package validation |

| VIADS Tool | Visual interactive data analysis and hypothesis generation | Clinical research hypothesis validation |

Regulatory Landscape and Future Directions

Evolving Regulatory Priorities

The regulatory environment continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace, with several key trends shaping validation requirements in 2025-2026 [11]:

Climate Risk: Weather-related disasters costing the U.S. economy $93 billion in the first half of 2025 alone are driving climate-responsive regulatory initiatives, including modernized risk-based capital formulas and heightened oversight of property and casualty markets [11].

Artificial Intelligence: Regulators are focusing on algorithmic bias, governance expectations, and auditing of AI systems across applications including underwriting, fraud detection, and customer interactions [11].

Cybersecurity: With more than 40 new requirements issued in 2024 alone, regulators are emphasizing incident response, standards, reinsurance, and data security, particularly for AI-driven breaches and social engineering [11].

Omnibus Legislation: Sprawling, multi-topic bills that often include insurance provisions alongside unrelated measures are increasing in complexity, with 47 omnibus regulations tracked so far in 2025 compared to 22 in all of 2024 [11].

Strategic Imperatives for Compliance Leaders

The volume and complexity of 2025 regulatory activity highlight clear imperatives for compliance organizations [11]:

- Anticipate More Change, Not Less: Even in a deregulatory environment, the net effect is rising obligations across federal and state levels

- Prioritize State-Level Awareness: With states filling gaps left by federal rollbacks, compliance teams must track and adapt to divergent state frameworks

- Build Climate and Technology Readiness: Climate risk modeling, AI governance, and cybersecurity resilience are becoming non-negotiable capabilities

- Prepare for Legislative Complexity: Omnibus bills and multi-layered health regulations require sophisticated monitoring and rapid analysis capabilities [11]

Validation plays an indispensable role in ensuring the integrity, reliability, and regulatory compliance of systems and processes across research and regulated environments. The validation landscape in 2025 is characterized by increasing digital transformation, with nearly all organizations either using or planning to use digital validation tools to address growing regulatory complexity and resource constraints. As teams navigate challenges including audit readiness, compliance burden, and data integrity, the adoption of advanced strategies such as automated testing, continuous validation, and risk-based approaches becomes increasingly critical for success.

The future of validation will be shaped by evolving regulatory priorities, including climate risk, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and the growing complexity of omnibus legislation. Organizations that proactively build capabilities in these areas, implement robust validation methodologies appropriate to their specific contexts, and maintain flexibility in the face of changing requirements will be best positioned to ensure both compliance and innovation in the years ahead.

In the realm of validation metrics for continuous variables research, the selection of an appropriate statistical method is a critical foundational step. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the choice between parametric and non-parametric approaches directly impacts the validity, reliability, and interpretability of study findings. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodological paths, focusing on their performance under various data distribution scenarios encountered in scientific research. By examining experimental data and detailing analytical protocols, this article aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to make informed decisions that strengthen the evidential basis of their research conclusions.

Theoretical Foundations: Understanding the Core Methodologies

Parametric and non-parametric methods constitute two fundamentally different approaches to statistical inference, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings and technical requirements.

Parametric methods are statistical techniques that rely on specific assumptions about the underlying distribution of the population from which the sample was drawn. These methods typically assume that the data follows a known probability distribution, most commonly the normal distribution, and estimate the parameters (such as mean and variance) of this distribution using sample data [19]. The validity of parametric tests hinges on several key assumptions: normality (data follows a normal distribution), homogeneity of variance (variance is equal across groups), and independence of observations [19] [20].

Non-parametric methods, in contrast, are "distribution-free" techniques that do not rely on stringent assumptions about the population distribution [19] [21]. These methods are based on ranks, signs, or order statistics rather than parameter estimates, making them more flexible when dealing with data that violate parametric assumptions [22] [23].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Across Key Metrics

The relative performance of parametric and non-parametric methods varies significantly depending on data characteristics and research context. The following structured comparison synthesizes findings from multiple experimental studies to highlight critical performance differences.

| Characteristic | Parametric Methods | Non-Parametric Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumptions | Assume normal distribution, homogeneity of variance, independence [19] [20] | Minimal assumptions; typically require only independence and random sampling [19] [23] |

| Parameters Used | Fixed number of parameters [19] | Flexible number of parameters [19] |

| Data Handling | Uses actual data values [19] | Uses data ranks or signs [22] [21] |

| Measurement Level | Best for interval or ratio data [19] | Suitable for nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio data [19] [22] |

| Central Tendency Focus | Tests group means [19] | Tests group medians [19] [21] |

| Efficiency & Power | More powerful when assumptions are met [19] [22] | Less powerful when parametric assumptions are met [19] [22] |

| Sample Size Requirements | Smaller sample sizes required [19] | Larger sample sizes often needed [19] [22] |

| Robustness to Outliers | Sensitive to outliers [19] | Robust to outliers [19] [24] |

| Computational Speed | Generally faster computation [19] | Generally slower computation [19] |

Statistical Power and Error Rates in Empirical Studies

| Study Context | Data Distribution | Sample Size | Parametric Test Performance | Non-Parametric Test Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized trial analysis [25] | Various non-normal distributions | 10-800 participants | ANCOVA generally superior power in most situations | Mann-Whitney superior only in extreme distribution cases |

| Simulation study [25] | Moderate positive skew | 20 per group | Log-transformed ANCOVA showed high power | Mann-Whitney showed lower power |

| Simulation study [25] | Extreme asymmetry distribution | 30 per group | ANCOVA power compromised | Mann-Whitney demonstrated advantage |

| General comparison [22] | Normal distribution | Small samples | t-test about 60% more efficient than sign test | Sign test requires larger sample size for same power |

| Clustered data analysis [26] | Non-normal, clustered | Varies | Standard parametric tests may be invalid | Rank-sum tests specifically developed for clustered data |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Applications

To ensure reproducible results in validation metrics research, standardized experimental protocols for method selection and application are essential.

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for choosing between parametric and non-parametric methods in research involving continuous variables:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Normality Testing and Distribution Assessment

- Visual Inspection: Generate histogram, Q-Q plot, and boxplot to assess distribution shape, symmetry, and presence of outliers [20].

- Formal Normality Tests: Apply Shapiro-Wilk test (preferred for small to moderate samples) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to quantitatively evaluate normality assumption.

- Variance Homogeneity Assessment: Use Levene's test or Bartlett's test to verify homogeneity of variances across comparison groups.

- Decision Threshold: Establish pre-determined alpha level (typically p < 0.05) for violation of assumptions; consider robust alternatives or transformations when assumptions are violated.

Protocol 2: Analysis of Randomized Trials with Baseline Measurements

- Data Structure Assessment: Determine correlation structure between baseline and post-treatment measurements [25].

- Change Score Evaluation: Examine distribution of change scores rather than just post-treatment scores, as change scores often approximate normality better than raw scores [25].

- Method Selection: Based on simulation studies, prefer ANCOVA with baseline adjustment over separate tests of change scores or post-treatment scores, as ANCOVA generally provides superior power even with non-normal data [25].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct parallel analyses using both parametric (ANCOVA) and non-parametric (Mann-Whitney on change scores) approaches to verify robustness of findings.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Statistical Analysis

The following table catalogues key methodological tools essential for implementing the described experimental protocols in validation metrics research.

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | Assesses departure from normality assumption | Preliminary assumption checking for parametric tests |

| Levene's Test | Evaluates homogeneity of variances across groups | Assumption checking for t-tests, ANOVA |

| Hodges-Lehmann Estimator | Provides robust estimate of treatment effect size | Non-parametric analysis of two-group comparisons [21] |

| Data Transformation Protocols | Methods to normalize skewed distributions (log, square root) | Pre-processing step for parametric analysis of non-normal data |

| Bootstrap Resampling | Empirical estimation of sampling distribution | Power enhancement, confidence interval estimation for complex data |

| ANCOVA with Baseline Adjustment | Controls for baseline values in randomized trials | Increases power in pre-post designs with continuous outcomes [25] |

The choice between parametric and non-parametric methods for analyzing continuous variables in validation research represents a critical methodological crossroad. Parametric methods offer superior efficiency and power when their underlying assumptions are satisfied, while non-parametric approaches provide robustness and validity protection when data deviate from these assumptions. Evidence from experimental studies indicates that ANCOVA often outperforms non-parametric alternatives in randomized trial contexts, even with non-normal data [25]. However, in cases of extreme distributional violations or small sample sizes, non-parametric methods maintain their advantage. For research professionals in drug development and scientific fields, a principled approach to method selection—informed by systematic data assessment, understanding of statistical properties, and consideration of research context—ensures that conclusions drawn from continuous variable analysis rest upon a solid methodological foundation.

In precision medicine and drug development, the journey from raw data to therapeutic insight is built upon a foundation of trusted information. Validation metrics serve as the critical tools for assessing the performance of analytical models and artificial intelligence (AI) systems, ensuring they produce reliable, actionable outputs [27] [28]. Parallel to this, data quality dimensions provide the framework for evaluating the underlying data itself, measuring its fitness for purpose across attributes like accuracy, completeness, and consistency [29] [30]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the interconnectedness of these two domains is paramount. Robust validation is impossible without high-quality data, and the value of quality data is realized only through validated analytical processes [31]. This synergy is especially critical when working with continuous variables in research, where subtle data imperfections can significantly alter model predictions and scientific conclusions.

The need for this integrated approach is underscored by industry findings that poor data quality costs businesses an average of $\text{\textdollar}12.9$ to $\text{\textdollar}15$ million annually [29] [30]. In regulatory contexts like drug development, rigorous model verification and validation (V&V) processes, coupled with comprehensive uncertainty quantification (UQ), are essential for building trust in digital twins and other predictive technologies [31]. This article explores the key metrics for validating models with continuous outputs, details their intrinsic connection to data quality dimensions, and provides practical methodologies for implementation within research environments.

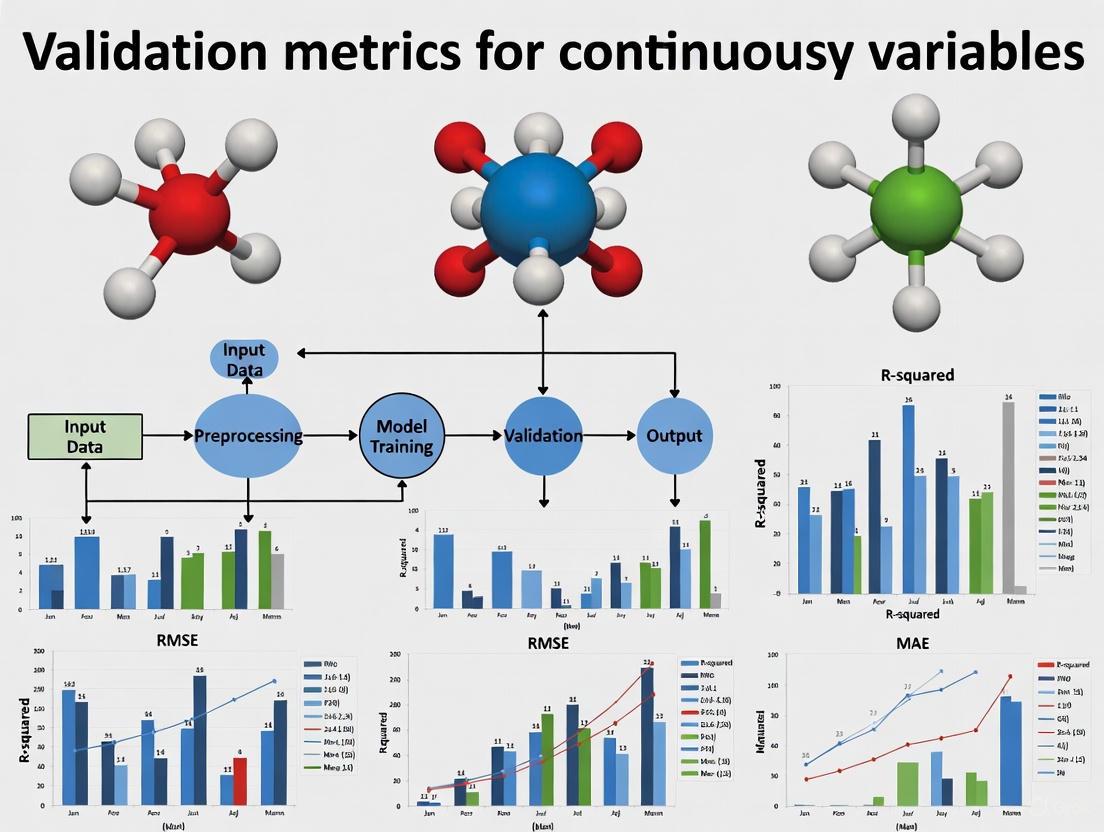

Key Validation Metrics for Continuous Variables

For research involving continuous variables—such as biomarker concentrations, pharmacokinetic parameters, or physiological measurements—specific validation metrics are employed to quantify model performance against ground truth data. These metrics provide standardized, quantitative assessments of how well a model's predictions align with observed values.

The following table summarizes the core validation metrics used for continuous variable models in scientific research:

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for Models with Continuous Outputs

| Metric | Mathematical Formula | Interpretation | Use Case in Drug Development | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Average magnitude of prediction errors (same units as variable). Lower values indicate better performance. | Predicting patient-specific drug dosage levels where the cost of error is linear and consistent. | |||

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Average of squared errors. Penalizes larger errors more heavily than MAE. | Validating pharmacokinetic models where large prediction errors (e.g., in peak plasma concentration) are disproportionately dangerous. | |||

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Square root of MSE. Restores units to the original scale. | Evaluating prognostic models for tumor size reduction; provides error in clinically interpretable units (e.g., mm). | |||

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. | Assessing a model predicting continuous clinical trial endpoints; indicates how well the model explains variability in patient response. |

Each metric offers a distinct perspective on model performance. While MAE provides an easily interpretable average error, MSE and RMSE are more sensitive to outliers and large errors, which is critical in safety-sensitive applications [28]. R² is particularly valuable for understanding the explanatory power of a model beyond mere prediction error, indicating how well the model captures the underlying variance in the biological system [28].

The Critical Link Between Validation Metrics and Data Quality

Validation metrics and data quality dimensions exist in a symbiotic relationship. The reliability of any validation metric is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the data used to compute it. This relationship can be visualized as a workflow where data quality serves as the foundation for meaningful validation.

Diagram 1: Workflow from data quality to trusted insights.

The following table details how specific data quality dimensions directly impact the integrity and reliability of validation metrics:

Table 2: How Data Quality Dimensions Impact Validation Metrics

| Data Quality Dimension | Impact on Validation Metrics | Example in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [29] [30] | Inaccurate ground truth data creates a false baseline, rendering all validation metrics meaningless and providing a misleading sense of model performance. | If true patient blood pressure measurements are systematically miscalibrated, a model's low MAE would be an artifact of measurement error, not predictive accuracy. |

| Completeness [30] [32] | Missing data points in the test set bias validation metrics. The calculated error may not be representative of the model's true performance across the entire data distribution. | A model predicting drug efficacy trained and tested on a dataset missing outcomes for elderly patients will yield unreliable R² values for the overall population. |

| Consistency [29] [33] | Inconsistent data formats or units (e.g., mg vs µg) introduce artificial errors, inflating metrics like MSE and RMSE without reflecting the model's actual predictive capability. | Merging lab data from multiple clinical sites that use different units for a biomarker without standardization will artificially inflate the RMSE of a prognostic model. |

| Validity [30] [34] | Data that violates business rules (e.g., negative values for a physical quantity) causes model failures and computational errors during validation. | A physiological model expecting a positive heart rate will fail or produce garbage outputs if the validation set contains negative values, preventing metric calculation. |

| Timeliness [35] [33] | Using outdated data for validation fails to assess how the model performs on current, relevant data, leading to metrics that don't reflect real-world usability. | Validating a model for predicting seasonal disease outbreaks with data from several years ago may show good MAE but fail to capture recent changes in pathogen strains. |

This interplay necessitates a "multi-metric, context-aware evaluation" [27] that considers both the statistical performance of the model and the data quality that underpins it. For instance, a surprisingly low MSE should prompt an investigation into data accuracy and consistency, not just be taken as a sign of a good model.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Model Validation

Implementing a rigorous, standardized protocol for model validation is essential for generating credible, reproducible results. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive methodology that integrates data quality checks directly into the validation process.

Diagram 2: End-to-end model validation protocol.

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Dataset Partitioning: Split the source data into three distinct sets: training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and a hold-out test set (e.g., 15%). The hold-out test set must remain completely untouched until the final validation phase [28].

- Data Quality Profiling: Use automated data profiling tools [30] or custom scripts to assess the quality of each dataset against the core dimensions:

- Completeness: Calculate the percentage of missing values for each critical field. Establish a threshold (e.g., >5% missingness may require imputation or exclusion) [35].

- Accuracy and Validity: Perform range validation [34] to ensure continuous variables fall within physiologically or clinically plausible limits (e.g., human body temperature between 35°C and 42°C). Apply format validation to categorical variables and identifiers.

- Consistency: Check for unit uniformity and consistent data formats across all records [32].

- Data Remediation: Based on the profiling results, apply techniques like imputation for missing data (with careful documentation of the method) or correction of invalid values. Any remediation applied to the training set must be applied identically to the validation and test sets.

Phase 2: Model Training and Validation

- Model Training: Train the model using only the training dataset.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Use the validation set to tune model hyperparameters. This prevents information from the test set leaking into the model development process.

- Final Validation: Execute the final, tuned model on the pristine hold-out test set to generate predictions. This step is crucial for obtaining an unbiased estimate of model performance on new, unseen data [28].

Phase 3: Metric Calculation and Analysis

- Compute Validation Metrics: Calculate the key metrics outlined in Table 1 (MAE, MSE, RMSE, R²) by comparing the model's predictions on the test set to the ground truth values.

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Go beyond point estimates by quantifying uncertainty in the model's predictions. This can involve calculating confidence intervals for the validation metrics or using Bayesian methods to provide probabilistic predictions [31]. UQ is essential for communicating the reliability of model outputs in clinical decision-making.

- Continuous Validation: For models deployed in production, establish a continuous model validation cadence [36]. This involves periodically re-validating the model on newly acquired data to detect and alert on "data drift," where the statistical properties of the incoming data change over time, degrading model performance.

To implement the protocols and metrics described, researchers require a suite of methodological "reagents" – the essential tools, software, and conceptual frameworks that enable robust validation and data quality management.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation and Data Quality

| Tool Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Application in Validation & Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical & Programming Frameworks | R (caret, tidyverse), Python (scikit-learn, pandas, NumPy, SciPy) |

Provide libraries for calculating all key validation metrics (MAE, MSE, R²), statistical analysis, and data manipulation. Essential for implementing custom validation workflows. |

| Data Profiling & Quality Tools | OvalEdge [30], Monte Carlo [33], custom SQL/Python scripts | Automate the assessment of data quality dimensions like completeness (missing values), uniqueness (duplicates), and validity. Generate reports to baseline data quality before model development. |

| Validation-Specific Software | Snorkel Flow [36], MLflow | Support continuous model validation [36], track experiment metrics, and manage model versions. Crucial for maintaining model reliability post-deployment in dynamic environments. |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Libraries | Python (PyMC3, TensorFlow Probability, UQpy) |

Implement Bayesian methods and other statistical techniques to quantify epistemic (model) and aleatoric (data) uncertainty [31], providing confidence bounds for predictions. |

| Data Validation Frameworks | Great Expectations, Amazon Deequ, JSON Schema [34] | Define and enforce "constraint validation" [34] rules (e.g., value ranges, allowed categories) programmatically, ensuring data validity and consistency throughout the data pipeline. |

The path to reliable, clinically relevant insights in drug development and precision medicine is a function of both sophisticated models and high-quality data. Key validation metrics like MAE, RMSE, and R² provide the quantitative rigor needed to assess model performance, while data quality dimensions—accuracy, completeness, consistency, validity, and timeliness—form the essential foundation upon which these metrics can be trusted. As the field advances with technologies like digital twins for precision medicine, the integrated framework of Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) highlighted by the National Academies [31] becomes increasingly critical. By adopting the experimental protocols and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure their work on continuous variables is not only statistically sound but also built upon a trustworthy data base, ultimately accelerating the translation of data-driven models into safe and effective patient therapies.

The validation landscape in regulated industries, particularly pharmaceuticals and medical devices, is undergoing a fundamental transformation. By 2025, digital validation has moved from an emerging trend to a mainstream practice, with 58% of organizations now using digital validation systems—a significant increase from just 30% the previous year [37]. This shift is driven by the need for greater efficiency, enhanced data integrity, and sustained audit readiness in an increasingly complex regulatory environment. The transformation extends beyond mere technology adoption to encompass new methodologies, skill requirements, and strategic approaches that are reshaping how organizations approach compliance and quality assurance.

This guide examines the current state of digital validation practices, comparing traditional versus modern approaches, analyzing implementation challenges, and exploring emerging technologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these trends is crucial for building robust validation frameworks that meet both current and future regulatory expectations while accelerating product development timelines.

Current State Analysis: Digital Validation Adoption and ROI

The 2025 validation landscape demonstrates significant digital maturation, yet reveals critical implementation gaps that affect return on investment (ROI) and operational efficiency.

Table 1: Digital Validation Adoption Metrics (2025)

| Metric | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Organizations using digital validation systems | 58% | 28% increase since 2024, indicating rapid sector-wide transformation [37] |

| Organizations meeting/exceeding ROI expectations | 63% | Majority of adopters achieving tangible financial benefits [38] |

| Digital systems integrated with other tools | 13% | Significant integration gap limiting potential value [37] |

| Teams reporting workload increases | 66% | Persistent resource constraints despite technology adoption [38] |

| Organizations outsourcing validation work | 70% | Strategic reliance on external expertise [39] |

Digital Validation ROI and Performance Metrics

Recent industry data demonstrates that digital validation is delivering measurable value. According to the 2025 State of Validation Report, 98% of respondents indicate their digital validation systems met, exceeded, or were on track to meet expectations, with only 2% reporting significant disappointment in ROI [37]. Organizations implementing comprehensive digital validation frameworks report performance improvements including:

- 50-70% faster cycle times for validation protocols [40] [38]

- Near-zero audit deviations due to traceable documentation [40]

- Up to 90% reduction in labor costs for documentation management [40]

However, the full potential of digital validation remains unrealized for many organizations due to integration challenges. Nearly 70% of organizations report their digital validation systems operate in silos, disconnected from project management, data analytics, or Turn Over Package (TOP) systems [37]. This integration gap creates unnecessary manual effort and limits visibility across the validation lifecycle.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Digital Validation Models

The transition from document-centric to data-centric validation represents a paradigm shift in how regulated industries approach compliance.

Table 2: Document-Centric vs. Data-Centric Validation Models

| Aspect | Document-Centric Model | Data-Centric Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Artifact | PDF/Word Documents | Structured Data Objects [38] |

| Change Management | Manual Version Control | Git-like Branching/Merging [38] |

| Audit Readiness | Weeks of Preparation | Real-Time Dashboard Access [38] |

| Traceability | Manual Matrix Maintenance | Automated API-Driven Links [38] |

| AI Compatibility | Limited (OCR-Dependent) | Native Integration [38] |

The Data-Centric Validation Framework

Progressive organizations are moving beyond "paper-on-glass" approaches—where digital systems simply replicate paper-based workflows—toward truly data-centric validation models. This transition enables four critical capabilities:

Unified Data Layer Architecture: Replacing fragmented document-centric models with centralized repositories enables real-time traceability and automated compliance with ALCOA++ principles [38].

Dynamic Protocol Generation: AI-driven systems can analyze historical protocols and regulatory guidelines to auto-generate context-aware test scripts, though regulatory acceptance remains a barrier [38].

Continuous Process Verification (CPV): IoT sensors and real-time analytics enable proactive quality management by feeding live data from manufacturing equipment into validation platforms [38].

Validation as Code: Representing validation requirements as machine-executable code enables automated regression testing during system updates and Git-like version control for protocols [38].

Figure 1: Evolution from traditional to data-centric validation approaches, highlighting key characteristics and limitations at each stage.

Workforce and Resource Challenges in Digital Validation

Despite technological advancements, human factors remain significant challenges in digital validation implementation.

Table 3: 2025 Validation Workforce Composition and Challenges

| Workforce Metric | Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Teams with 1-3 dedicated staff | 39% | Lean resourcing constraining digital transformation initiatives [39] |

| Professionals with 6-15 years experience | 42% | Mid-career dominance creating experience gaps as senior experts retire [38] |

| Organizations citing resistance to change | 45% | Cultural and organizational barriers outweigh technical challenges [37] |

| Teams reporting complexity challenges | 49% | Validation complexity remains primary implementation hurdle [37] |

Strategic Responses to Workforce Challenges

Forward-thinking organizations are addressing these workforce challenges through several key strategies:

Targeted Outsourcing: With 70% of firms now outsourcing part of their validation workload, organizations are building hybrid internal-external team models that balance cost control with specialized expertise [39].

Digital Champions Programs: Identifying and empowering enthusiastic employees within each department to act as local experts and advocates for digital validation tools, providing peer support and driving adoption [41].

Cross-Functional Training: Developing data fluency across validation, quality, and technical teams to bridge the gap between domain expertise and digital implementation capabilities [38].

The 2025 State of Validation Report notes that the most commonly reported implementation challenges aren't technical—they're cultural and organizational, with 45% of organizations struggling with resistance to change and 38% having trouble ensuring user adoption [37].

AI and Emerging Technologies in Validation

Artificial intelligence adoption in validation remains in early stages but shows significant potential for transforming traditional approaches.

Table 4: AI Adoption in Validation (2025)

| AI Application | Adoption Rate | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Protocol Generation | 12% | 40% faster drafting through NLP analysis of historical protocols [38] |

| Risk Assessment Automation | 9% | 30% reduction in deviations through predictive risk modeling [38] |

| Predictive Analytics | 5% | 25% improvement in audit readiness through pattern recognition [38] |

| Anomaly Detection | 7% | Early identification of validation drift and non-conformance patterns [40] |

AI Implementation Framework for Validation

While AI adoption rates remain modest, leading organizations are building foundational capabilities for AI integration:

Data Quality Foundation: AI effectiveness in validation depends heavily on underlying data quality, with metrics including freshness (how current the data is), bias (representation balance), and completeness (absence of critical gaps) being essential prerequisites [42].

Computer Software Assurance (CSA) Adoption: Despite regulatory encouragement, only 16% of organizations have fully adopted CSA, which provides a risk-based approach to software validation that aligns well with AI-assisted methodologies [39].

Staged Implementation Approach: Successful organizations typically begin AI integration with low-risk applications such as document review and compliance checking before progressing to higher-impact areas like predictive analytics and automated protocol generation [38].

According to industry analysis, "AI is something to consider for the future rather than immediate implementation, as we still need to fully understand how it functions. There are substantial concerns regarding the validation of AI systems that the industry must address" [38].

Global Regulatory Initiatives and Standards

Digital transformation in validation is occurring within an evolving global regulatory framework that increasingly emphasizes data integrity and digital compliance.

China's Pharmaceutical Digitization Initiative

China's recent "Pharmaceutical Industry Digital Transformation Implementation Plan (2025-2030)" outlines ambitious digital transformation goals, including:

- Developing 30+ pharmaceutical industry digital technology standards by 2027 [43]

- Creating 100+ digital technology application scenarios covering R&D, production, and quality management [43]

- Establishing 10+ pharmaceutical large model innovation platforms and digital technology application verification platforms [43]

- Achieving comprehensive digital transformation coverage for scale pharmaceutical enterprises by 2030 [43]

This initiative emphasizes computerized system validation (CSV) guidelines specifically addressing process control, quality control, and material management systems [43].

Integrated Validation Framework Implementation

The AAA Framework (Audit, Automate, Accelerate) exemplifies the integrated approach organizations are taking to digital validation:

Audit Phase: Comprehensive assessment of processes, data readiness, and regulatory conformance to establish a quantified baseline for digital validation implementation [40].

Automate Phase: Workflow redesign incorporating AI agents, digital twins, and human-in-the-loop validation cycles with continuous documentation trails [40].

Accelerate Phase: Implementation of governance dashboards, feedback loops, and reusable blueprints to scale validated systems across organizations [40].

Organizations implementing such frameworks report moving from reactive compliance to building "always-ready" systems that maintain continuous audit readiness through proactive risk mitigation and self-correcting workflows [38].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Validation

Implementing effective digital validation requires specific technological components and methodological approaches.

Table 5: Digital Validation Research Reagent Solutions

| Solution Category | Specific Technologies | Function in Validation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Validation Platforms | Kneat, ValGenesis, SAS | Electronic management of validation lifecycle, protocol execution, and deviation management [37] |

| Data Integrity Tools | Blockchain-based audit trails, Electronic signatures, Version control systems | Ensure ALCOA++ compliance, prevent data tampering, maintain complete revision history [43] |

| Integration Frameworks | RESTful APIs, ESB, Middleware | Connect validation systems with manufacturing equipment, LIMS, and ERP systems [37] |

| Analytics and Monitoring | Process mining, Statistical process control, Real-time dashboards | Continuous monitoring of validation parameters, early anomaly detection [38] |

| AI/ML Research Tools | Natural Language Processing, Computer vision, Predictive algorithms | Automated document review, visual inspection verification, risk prediction [38] |

The digital transformation of validation practices in 2025 represents both a challenge and opportunity for researchers and drug development professionals. Organizations that successfully navigate this transition are those treating validation as a strategic capability rather than a compliance obligation. The most successful organizations embed validation and governance into their operating models from the outset, with high performers treating "validation as a design layer, not a delay" [40].

As global regulatory frameworks evolve to accommodate digital approaches, professionals who develop expertise in data-centric validation, AI-assisted compliance, and integrated quality systems will be well-positioned to lead in an increasingly digital pharmaceutical landscape. The organizations that thrive will be those that view digital validation not as a cost center, but as a strategic asset capable of accelerating development timelines while enhancing product quality and patient safety.

From Theory to Practice: Essential Methods and Real-World Applications

In the realm of research, particularly in fields such as drug development and clinical studies, the validation of continuous variables against meaningful benchmarks is paramount. The t-test family provides foundational statistical methods for comparing means when population standard deviations are unknown, making these tests particularly valuable for analyzing sample data from larger populations [44] [45]. These parametric tests enable researchers to determine whether observed differences in continuous data—such as blood pressure measurements, laboratory values, or clinical assessment scores—represent statistically significant effects or merely random variation [2].

T-tests occupy a crucial position in hypothesis testing for continuous data, serving as a bridge between descriptive statistics and more complex analytical methods. Their relative simplicity, computational efficiency, and interpretability have made them a staple in research protocols across scientific disciplines [46]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the proper application, assumptions, and limitations of each t-test type is essential for designing robust studies and drawing valid conclusions from experimental data.

Fundamental Concepts and Assumptions

Core Principles of T-Testing

All t-tests share fundamental principles despite their different applications. At their core, t-tests evaluate whether the difference between group means is statistically significant by calculating a t-statistic, which represents the ratio of the difference between means to the variability within the groups [47]. This test statistic is then compared to a critical value from the t-distribution—a probability distribution that accounts for the additional uncertainty introduced when estimating population parameters from sample data [45].

The t-distribution resembles the normal distribution but has heavier tails, especially with smaller sample sizes. As sample sizes increase, the t-distribution approaches the normal distribution [48]. This relationship makes t-tests particularly valuable for small samples (typically n < 30), where the z-test would be inappropriate [45] [46].

Key Assumptions for Parametric T-Tests

For t-tests to yield valid results, several assumptions must be met:

- Continuous data: The dependent variable should be measured on an interval or ratio scale [44] [2].

- Independence of observations: Data points must not influence each other, except in the case of paired designs where the pairing is the focus [47] [46].

- Approximate normality: The data should follow a normal distribution, though t-tests are reasonably robust to minor violations of this assumption, especially with larger sample sizes (n > 30) due to the Central Limit Theorem [2] [48].

- Homogeneity of variance: For independent samples t-tests, the variances in both groups should be approximately equal [44] [47].

When these assumptions are severely violated, researchers may need to consider non-parametric alternatives such as the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test or data transformation techniques [47] [2].

One-Tailed vs. Two-Tailed Tests

An important consideration in t-test selection is whether to use a one-tailed or two-tailed test:

- Two-tailed tests examine whether means are different in either direction and are appropriate when research questions simply ask if a difference exists [44] [45].

- One-tailed tests examine whether one mean is specifically greater or less than another and should only be used when there is a strong prior directional hypothesis before data collection [44] [46].

Table 1: Comparison of One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Tests

| Feature | One-Tailed Test | Two-Tailed Test |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of Interest | Specific direction | Either direction |

| Alternative Hypothesis | Specifies direction | No direction specified |

| Critical Region | One tail | Both tails |

| Statistical Power | Higher for specified direction | Lower, but detects effects in both directions |

| When to Use | Strong prior direction belief | Any difference is of interest |

The t-test family comprises three primary tests, each designed for specific research scenarios and data structures. Understanding the distinctions between these tests is crucial for selecting the appropriate analytical approach.

One-Sample T-Test

The one-sample t-test compares the mean of a single group to a known or hypothesized population value [44] [49]. This test answers the question: "Does our sample come from a population with a specific mean?"

Independent Samples T-Test

Also known as the two-sample t-test or unpaired t-test, the independent samples t-test compares means between two unrelated groups [44] [47]. This test determines whether there is a statistically significant difference between the means of two independent groups.

Paired T-Test

The paired t-test (also called dependent samples t-test) compares means between two related groups [44] [50]. This test is appropriate when measurements are naturally paired or matched, such as pre-test/post-test designs or matched case-control studies.

Table 2: Comparison of T-Test Types

| Test Type | Number of Variables | Purpose | Example Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Sample | One continuous variable | Decide if population mean equals a specific value | Is the mean heart rate of a group equal to 65? |

| Independent Samples | One continuous and one categorical variable (2 groups) | Decide if population means for two independent groups are equal | Do mean heart rates differ between men and women? |

| Paired Samples | Two continuous measurements from matched pairs | Decide if mean difference between paired measurements is zero | Is there a difference in blood pressure before and after treatment? |

Decision Workflow for T-Test Selection

Selecting the appropriate t-test requires careful consideration of your research design, data structure, and hypothesis. The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to t-test selection:

Figure 1: T-Test Selection Workflow

One-Sample T-Test

Methodology and Applications

The one-sample t-test evaluates whether the mean of a single sample differs significantly from a specified value [44]. This test is particularly useful in quality control, method validation, and when comparing study results to established standards.

The test statistic for the one-sample t-test is calculated as:

[ t = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{s/\sqrt{n}} ]

Where (\bar{x}) is the sample mean, (\mu_0) is the hypothesized population mean, (s) is the sample standard deviation, and (n) is the sample size [2] [48].

Experimental Protocol

Research Scenario: A pharmaceutical company wants to validate that the average dissolution time of a new generic drug formulation meets the standard reference value of 30 minutes established by the regulatory agency.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Define hypotheses:

- Null hypothesis (H₀): The mean dissolution time equals 30 minutes ((\mu = 30))

- Alternative hypothesis (H₁): The mean dissolution time differs from 30 minutes ((\mu \ne 30))

Set significance level: Typically α = 0.05 [2]

Collect data: Randomly select 25 tablets from production and measure dissolution time for each

Check assumptions:

- Independence: Ensure tablets are randomly selected

- Normality: Assess using histogram, Q-Q plot, or Shapiro-Wilk test [2]

Calculate test statistic using the formula above

Determine critical value from t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom

Compare test statistic to critical value and make decision regarding H₀

Interpret results in context of research question

Real-World Application Example

In manufacturing, an engineer might use a one-sample t-test to determine if products created using a new process have a different mean battery life from the current standard of 100 hours [51]. After testing 50 products, if the analysis shows a statistically significant difference, this would provide evidence that the new process affects battery life.

Independent Samples T-Test

Methodology and Applications

The independent samples t-test (also called unpaired t-test) compares means between two unrelated groups [47] [48]. This test is widely used in randomized controlled trials, A/B testing, and any research design with two independent experimental groups.

The test statistic for the independent samples t-test is calculated as:

[ t = \frac{\bar{x1} - \bar{x2}}{sp \sqrt{\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n_2}}} ]

Where (\bar{x1}) and (\bar{x2}) are the sample means, (n1) and (n2) are the sample sizes, and (s_p) is the pooled standard deviation [2].

Experimental Protocol

Research Scenario: A research team is comparing the efficacy of two different diets (A and B) on weight loss in a randomized controlled trial.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Define hypotheses:

- H₀: Mean weight loss is the same for both diets ((\mu1 = \mu2))

- H₁: Mean weight loss differs between diets ((\mu1 \ne \mu2))

Set significance level: α = 0.05

Design study: Randomly assign 20 subjects to Diet A and 20 subjects to Diet B [51]

Collect data: Measure weight loss for each subject after one month

Check assumptions:

- Independence: Ensure random assignment and no communication between groups

- Normality: Check distribution of weight loss in each group

- Homogeneity of variance: Assess using Levene's test or similar method [48]

Calculate test statistic and degrees of freedom

Determine critical value from t-distribution

Compare test statistic to critical value and make decision

Calculate confidence interval for the mean difference

Interpret results in context of clinical significance

Experimental Design Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental design for an independent samples t-test:

Figure 2: Independent Samples T-Test Experimental Design

Real-World Application Example

In education research, a professor might use an independent samples t-test to compare exam scores between students who used two different studying techniques [51]. By randomly assigning students to each technique and ensuring no interaction between groups, the professor can attribute any statistically significant difference in means to the studying technique rather than confounding variables.

Paired Samples T-Test

Methodology and Applications

The paired samples t-test (also called dependent samples t-test) compares means between two related measurements [50]. This test is appropriate for pre-test/post-test designs, matched case-control studies, repeated measures, or any scenario where observations naturally form pairs.

The test statistic for the paired samples t-test is calculated as:

[ t = \frac{\bar{d}}{s_d/\sqrt{n}} ]

Where (\bar{d}) is the mean of the differences between paired observations, (s_d) is the standard deviation of these differences, and (n) is the number of pairs [2] [50].

Experimental Protocol

Research Scenario: A clinical research team is evaluating the effectiveness of a new blood pressure medication by comparing patients' blood pressure before and after treatment.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Define hypotheses:

- H₀: The mean difference in blood pressure is zero ((\mu_d = 0))

- H₁: The mean difference in blood pressure is not zero ((\mu_d \ne 0))

Set significance level: α = 0.05

Design study: Recruit 15 patients with hypertension and measure blood pressure before and after a 4-week treatment period [51]

Collect data: Record paired measurements for each subject

Check assumptions:

- Independence: Differences between pairs should be independent

- Normality: The distribution of differences should be approximately normal [50]

Calculate differences for each pair of observations

Compute mean and standard deviation of the differences

Calculate test statistic using the formula above

Determine critical value from t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom

Compare test statistic to critical value

Interpret results including both statistical and clinical significance

Experimental Design Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental design for a paired samples t-test:

Figure 3: Paired Samples T-Test Experimental Design

Real-World Application Example

In pharmaceutical research, a paired t-test might be used to evaluate a new fuel treatment by measuring miles per gallon for 11 cars with and without the treatment [51]. Since each car serves as its own control, the paired design eliminates variability between different vehicles, providing a more powerful test for detecting the treatment effect.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Comprehensive Comparison of T-Test Results

When reporting t-test results, researchers should include key elements that allow for proper interpretation and replication. The following table summarizes essential components for each t-test type:

Table 3: Key Reporting Elements for Each T-Test Type

| Test Element | One-Sample T-Test | Independent Samples | Paired Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | n | n₁, n₂ | n (number of pairs) |

| Mean(s) | Sample mean ((\bar{x})) | Group means ((\bar{x1}), (\bar{x2})) | Mean of differences ((\bar{d})) |

| Standard Deviation | Sample SD (s) | Group SDs (s₁, s₂) or pooled SD | SD of differences (s_d) |

| Test Statistic | t-value | t-value | t-value |

| Degrees of Freedom | n - 1 | n₁ + n₂ - 2 | n - 1 |

| P-value | p-value | p-value | p-value |

| Confidence Interval | CI for population mean | CI for difference between means | CI for mean difference |

Interpretation Guidelines

Proper interpretation of t-test results extends beyond statistical significance to consider practical importance:

Statistical significance: If p < α, reject the null hypothesis and conclude there is a statistically significant difference [2]

Effect size: Calculate measures such as Cohen's d to assess the magnitude of the effect, not just its statistical significance

Confidence intervals: Examine the range of plausible values for the population parameter

Practical significance: Consider whether the observed difference is meaningful in the real-world context

Assumption checks: Report any violations of assumptions and how they were addressed

For example, in a paired t-test analysis of exam scores, researchers found a mean difference of 1.31 with a t-statistic of 0.75 and p-value > 0.05, leading to the conclusion that there was no statistically significant difference between the exams [50].