A Comprehensive Guide to Input-Output Transformation Validation Methods for Robust Drug Development

This article provides a complete framework for validating input-output transformations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

A Comprehensive Guide to Input-Output Transformation Validation Methods for Robust Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for validating input-output transformations, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational principles, practical methodologies for application, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous validation and comparative techniques. The content is designed to help scientific teams ensure the accuracy, reliability, and regulatory compliance of their data pipelines and AI models, which are critical for accelerating discovery and securing regulatory approval.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Regulatory Imperatives for Data Validation

Defining Input-Output Validation in the Drug Development Context

Input-output validation is a critical process in drug development that ensures computational and experimental systems reliably transform input data into accurate, meaningful outputs. This process provides the foundational confidence in the data and models that drive decision-making, from early discovery to clinical application. It confirms that a system, whether a biochemical assay, a AI model, or a physiological simulation, performs as intended within its specific context of use [1] [2].

The pharmaceutical industry faces a pressing need for robust validation frameworks. Despite technological advancements, drug development remains hampered by high attrition rates, often linked to irreproducible data and a lack of standardized validation practices. It is reported that 80-90% of published biomedical literature may be unreproducible, contributing to program delays and failures [2]. Input-output validation serves as a crucial countermeasure to this problem, establishing a framework for generating reliable, actionable evidence.

Theoretical Foundations and Regulatory Framework

Core Principles of Input-Output Validation

At its core, input-output validation is the experimental confirmation that an analytical or computational procedure consistently provides reliable information about the object of analysis [1]. This involves a comprehensive assessment of multiple performance characteristics, which together ensure the system's outputs are a faithful representation of the underlying biological or chemical reality.

The validation process is governed by a "learn and confirm" paradigm, where experimental findings are systematically integrated to generate testable hypotheses, which are then refined through further experimentation [3]. This iterative process ensures models and methods remain grounded in empirical evidence throughout the drug development pipeline.

Key Validation Parameters

Guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), USP, and other regulatory bodies specify essential validation parameters that must be evaluated for analytical procedures [1]. The specific parameters required depend on the type of test being validated, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Validation Parameters for Different Types of Analytical Procedures

| Validation Parameter | Identification | Testing for Impurities | Assay (Quantification) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | - | Yes | Yes |

| Precision | - | Yes | Yes |

| Specificity | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Detection Limit | - | Yes | - |

| Quantitation Limit | - | Yes | - |

| Linearity | - | Yes | Yes |

| Range | - | Yes | Yes |

| Robustness | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Source: Adapted from ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, as referenced in [1]

Accuracy represents the closeness between the test result and the true value, indicating freedom from systematic error (bias). Precision describes the scatter of results around the average value and is assessed at three levels: repeatability (same conditions), intermediate precision (different days, analysts, equipment), and reproducibility (between laboratories) [1].

Specificity is the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components, while Linearity and Range establish that the method produces results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a specified range. Robustness measures the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in procedural parameters [1].

Validation Approaches Across the Drug Development Pipeline

Traditional Analytical Method Validation

In pharmaceutical quality control, validation of analytical procedures is mandatory according to pharmacopoeial and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) requirements. All quantitative tests must be validated, including assays and impurity tests, while identification tests require validation specifically for specificity [1].

The validation process involves extensive experimental testing against recognized standards. For accuracy assessment, this typically involves analysis using Reference Standards (RS) or model mixtures with known quantities of the drug substance. The procedure is considered accurate if the conventionally true values fall within the confidence intervals of the results obtained by the method [1].

Revalidation is required when changes occur in the drug manufacturing process, composition, or the analytical procedure itself. This ensures the validated state is maintained throughout the product lifecycle [1].

AI and Computational Model Validation

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in drug discovery has introduced new dimensions to input-output validation. A systematic review of AI validation methods identified four primary approaches: trials, simulations, model-centred validation, and expert opinion [4].

For AI systems, validation must ensure the model reliably transforms input data into accurate predictions or decisions. This is particularly challenging given the "black box" nature of some complex algorithms. The taxonomy of AI validation methods includes failure monitors, safety channels, redundancy, voting, and input and output restrictions to continuously validate systems after deployment [4].

A notable example is the development of an autonomous AI agent for clinical decision-making in oncology. The system integrated GPT-4 with specialized precision oncology tools, including vision transformers for detecting microsatellite instability and KRAS/BRAF mutations from histopathology slides, MedSAM for radiological image segmentation, and access to knowledge bases including OncoKB and PubMed [5]. The validation process evaluated the system's ability to autonomously select and use appropriate tools (87.5% accuracy), reach correct clinical conclusions (91.0% of cases), and cite relevant oncology guidelines (75.5% accuracy) [5].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Validated AI Systems in Drug Development

| AI System/Application | Validation Metric | Performance Result | Comparison Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology AI Agent [5] | Correct clinical conclusions | 91.0% | - |

| Oncology AI Agent [5] | Appropriate tool use | 87.5% | - |

| Oncology AI Agent [5] | Guideline citation accuracy | 75.5% | - |

| Oncology AI Agent [5] | Treatment plan completeness | 87.2% | GPT-4 alone: 30.3% |

| In-silico Trials [6] | Resource requirements | ~33% of conventional trial | - |

| In-silico Trials [6] | Development timeline | 1.75 years vs. 4 years | Conventional trial: 4 years |

The validation demonstrated that integrating language models with precision oncology tools substantially enhanced clinical accuracy compared to GPT-4 alone, which achieved only 30.3% completeness in treatment planning [5].

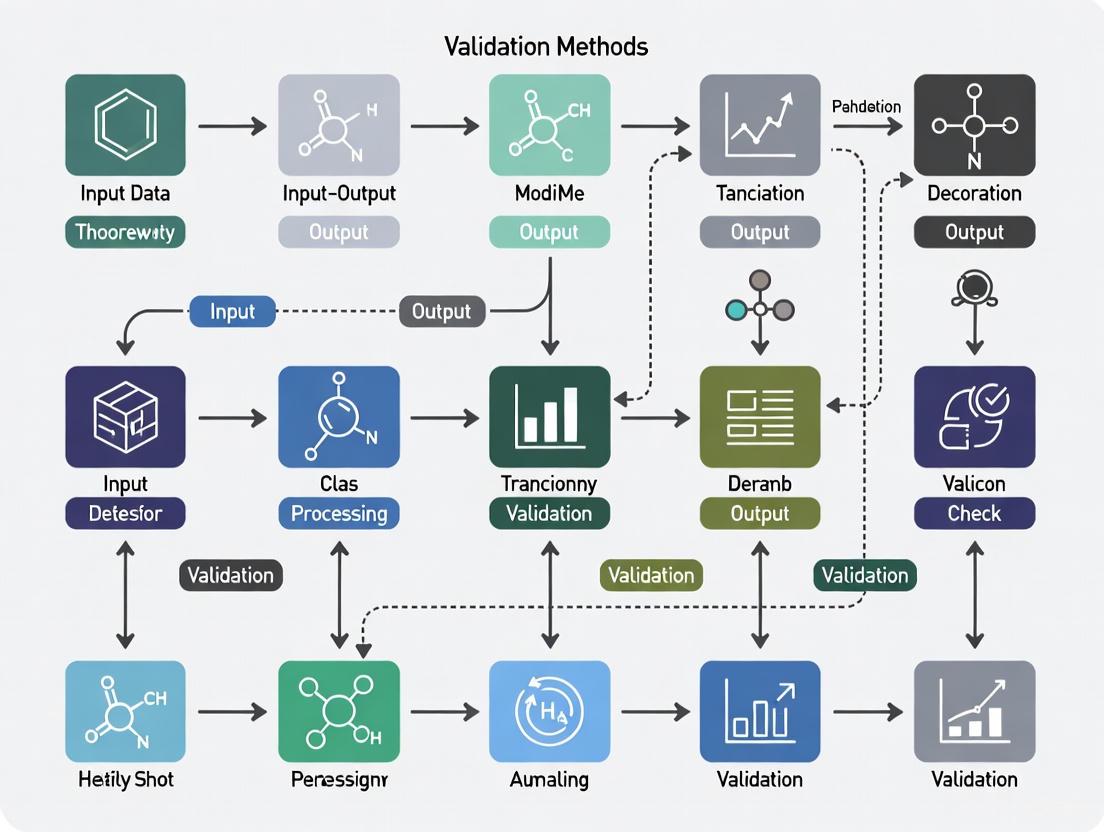

Figure 1: Input-Output Validation Framework for Clinical AI Systems in Oncology, demonstrating the transformation of multimodal medical data into validated clinical decisions through specialized tool integration [5].

In-silico Trial and Virtual Cohort Validation

In-silico trials using virtual cohorts represent another frontier where input-output validation is crucial. These computer simulations are used in the development and regulatory evaluation of medicinal products, devices, or interventions [6]. The European Union's SIMCor project developed a comprehensive framework for validating cardiovascular virtual cohorts, resulting in an open-source statistical web application for validation and analysis [6].

The SIMCor validation environment implements statistical techniques to compare virtual cohorts with real datasets, supporting both the validation of virtual cohorts and the application of validated cohorts in in-silico trials [6]. This approach demonstrates how input-output validation enables the acceptance of in-silico methods as reliable alternatives to traditional clinical trials, with reported potential to reduce development time from 4 years to 1.75 years while requiring approximately one-third of the resources [6].

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Validating an Autonomous AI Clinical Agent

The development and validation of the autonomous AI agent for oncology decision-making followed a rigorous protocol [5]:

Step 1: System Architecture Integration

- Base LLM (GPT-4) integrated with specialized unimodal deep learning models

- Tool suite implementation: vision transformers for histopathology analysis, MedSAM for radiological image segmentation, knowledge search tools (OncoKB, PubMed, Google), and calculator functions

- Compilation of evidence repository with ~6,800 medical documents and clinical scores from six oncology-specific sources

Step 2: Benchmark Development

- Creation of 20 realistic, multimodal patient cases focusing on gastrointestinal oncology

- Each case included clinical vignettes with corresponding questions requiring tool use and evidence retrieval

- Simulation of complete patient journeys with multimodal data integration

Step 3: Validation Methodology

- Two-stage process: autonomous tool selection and application followed by document retrieval for evidence-based responses

- Blinded manual evaluation by four human experts across three domains: tool use effectiveness, quality and completeness of textual outputs, and precision of relevant citations

- Evaluation against 109 predefined statements for treatment plan completeness across the 20 cases

Step 4: Performance Benchmarking

- Comparison against GPT-4 alone and other state-of-the-art models (Llama-3 70B, Mixtral 8x7B)

- Quantitative assessment of tool invocation success rate (56 of 64 required tools correctly used)

- Evaluation of sequential tool chaining capability for multistep reasoning

Protocol for Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Model Validation

Quantitative and Systems Pharmacology employs a distinct validation approach for its mathematical models [3]:

Step 1: Project Objective and Scope Definition

- Define clear context of use and model purpose

- Establish minimal physiological aspects necessary to achieve goals

- Identify crucial "states" to be tracked (e.g., plasma insulin, glucose in diabetes models)

Step 2: Biological Mechanism Formalization

- Develop diagrams visualizing relationships between different biological states

- Translate biological knowledge into mathematical representations (typically Ordinary Differential Equations)

- Integrate "top-down" clinical perspective with "bottom-up" physiological mechanisms

Step 3: Model Calibration and Verification

- Implement "learn and confirm" paradigm integrating experimental findings

- Calibrate parameters using available preclinical and clinical data

- Verify mathematical consistency and numerical stability

Step 4: Predictive Capability Assessment

- Execute "what-if" experiments to predict clinical trial outcomes

- Determine optimal minimum effective dosage based on preclinical data

- Evaluate combination therapies with different mechanisms of action

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Input-Output Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards (RS) [1] | Provide conventionally true values for accuracy assessment | Analytical method validation for drug quantification |

| Model Mixtures [1] | Simulate complex biological matrices for specificity testing | Impurity testing, method selectivity validation |

| Virtual Cohort Datasets [6] | Serve as reference for in-silico model validation | Cardiovascular device development, physiological simulations |

| Validated Histopathology Slides [5] | Ground truth for AI vision model validation | Oncology AI agent for MSI, KRAS, BRAF detection |

| Radiological Image Archives [5] | Reference standard for image segmentation algorithms | MedSAM tool validation in clinical AI systems |

| OncoKB Database [5] | Curated knowledge base for clinical decision validation | Precision oncology AI agent benchmarking |

| Clinical Data Repositories [2] | Provide real-world data for model benchmarking | FAIR data principles implementation, AI/ML training |

Data Standards and FAIR Principles

The critical importance of data standards in input-output validation cannot be overstated. The value of data generated from physiologically relevant cell-based assays and AI/ML approaches is limited without properly implemented data standards [2]. The FAIR Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) provide a guiding framework for standardization efforts.

The biomedical community's lack of standardized experimental processes creates significant obstacles. For example, the development of microphysiological systems (MPS) as advanced in vitro models has been hampered by insufficient harmonized characterization and validation between different technologies, creating uncertainty about their added value [2].

Successful standardization requires attention to three main areas: (1) experimental standards to establish scientific relevance and clinical predictability; (2) information standards to ensure dataset comparability across institutions; and (3) dissemination standards to enable proper data communication and reuse [2].

Figure 2: Comprehensive Data Standardization Framework for Input-Output Validation, showing the three pillars of standardization guided by FAIR principles to ensure reliable and reproducible results in drug development [2].

Input-output validation represents a cornerstone of modern drug development, ensuring the reliability of data and models that drive critical decisions from discovery through clinical application. As the field increasingly adopts complex AI systems, in-silico trials, and sophisticated analytical methods, robust validation frameworks become increasingly essential.

The protocols and examples presented demonstrate that successful validation requires meticulous attention to defined performance parameters, appropriate statistical methodologies, and adherence to standardized practices. The integration of FAIR data principles throughout the validation process further enhances reproducibility and reliability.

As drug development continues to evolve toward more computational and AI-driven approaches, input-output validation will play an increasingly central role in ensuring these advanced methods generate trustworthy, actionable evidence. This will require ongoing refinement of validation methodologies, development of new standards, and cross-disciplinary collaboration among researchers, regulators, and technology developers.

In research and development, particularly in regulated industries like pharmaceuticals, the integrity of data and processes is paramount. Validation serves as the foundational layer ensuring that all inputs to a system and the resulting outputs are correct, consistent, and secure. It is defined as the confirmation by objective evidence that the previously established requirements for a specific intended use are met [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, robust validation protocols are not merely a regulatory checkbox but a critical scientific discipline that underpins the trustworthiness of all experimental data and subsequent decisions [8]. A failure in validation can lead to catastrophic outcomes, including compromised product quality, erroneous research conclusions, and significant security vulnerabilities [9] [10].

This document frames validation within the broader context of input-output transformation methods, providing a detailed examination of its role as the first line of defense. We will explore essential data validation techniques, present experimental protocols for method validation, and outline the lifecycle approach for process validation, all tailored to the needs of scientific research.

Essential Data Validation Techniques

Data validation encompasses a suite of techniques designed to check data for correctness, meaningfulness, and security before it is processed [10]. Implementing these techniques at the point of entry prevents erroneous data from contaminating systems and ensures the integrity of downstream analysis.

The following table summarizes the core data validation techniques critical for research data integrity:

Table 1: Core Data Validation Techniques for Scientific Data Integrity

| Technique | Core Function | Common Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Type Validation [11] [10] | Verifies data matches the expected type (integer, float, string, date). | Ensuring instrument readings are numeric before statistical analysis; confirming date formats in patient data. |

| Range & Constraint Validation [11] [10] | Confirms data falls within a predefined minimum/maximum range or meets a logical constraint. | Checking pH values are between 0-14; verifying patient age in a clinical trial is plausible (e.g., 18-120). |

| Format & Pattern Validation [11] [10] | Ensures data adheres to a specific structural pattern, often using regular expressions. | Validating email addresses, sample IDs against a naming convention, or genomic sequences against an expected pattern. |

| Constraint & Business Logic Validation [11] | Enforces complex rules and relationships between different data points. | Ensuring a clinical trial's end date does not precede its start date; preventing duplicate patient enrollments (uniqueness check). |

| Code & Cross-Reference Validation [10] | Verifies data against a known list of allowed values or external reference data. | Ensuring a provided country code is valid; confirming a reagent lot number exists in an inventory database. |

| Consistency Validation [10] | Ensures data is logically consistent across related fields or systems. | Prohibiting a sample's analysis date from preceding its collection date. |

The Critical Role of Output Validation

While input validation is often emphasized, output validation is an equally critical defense mechanism. It involves sanitizing data before it leaves an API or system to prevent accidental exposure of sensitive information [9]. This includes:

- Preventing Data Leakage: Removing sensitive internal metadata, debugging information, or Personally Identifiable Information (PII) from API responses [9].

- Ensuring Response Consistency: Applying data minimization principles to return only necessary information to the client, using standardized and secure response formats [9].

Validating the Validator: Test Method Validation (TMV)

In medical device and pharmaceutical development, the integrity of test data depends on a fundamental principle—the test method itself must be validated [8]. Test Method Validation (TMV) ensures that both hardware and software test methods produce accurate, consistent, and reproducible results, independent of the operator, location, or time of execution [8].

TMV Experimental Protocol Framework

The following protocol provides a generalized framework for validating a test method, adaptable for both hardware and software contexts in a research environment.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Test Method Validation

| Protocol Step | Objective | Key Activities & Measured Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Define Objective | To clearly state the purpose of the test method and what it intends to measure. | Define the Measurement Variable (e.g., bond strength, concentration, software response time). Document acceptance criteria based on regulatory standards and product requirements [8]. |

| 2. Develop Method | To establish a detailed, reproducible test procedure. | Select and calibrate equipment. Write a step-by-step test procedure. For software, this includes developing automated test scripts [8]. |

| 3. Perform Gage R&R (Hardware Focus) | To quantify the measurement system's variation (repeatability and reproducibility). | Multiple operators repeatedly measure a set of representative samples. Calculate %GR&R; a value below 10% is generally considered acceptable, indicating the method is capable [8]. |

| 4. Verify Test Code (Software Focus) | To ensure automated test scripts are functionally correct and maintainable. | Perform code review. Establish traceability from test scripts to software requirements (e.g., via a Requirements Traceability Matrix). Validate script output for known inputs [8]. |

| 5. Assess Accuracy & Linearity | To evaluate the method's trueness (bias) and performance across the operating range. | Measure certified reference materials across the intended range. Calculate bias and linear regression statistics (R², slope) [12] [8]. |

| 6. Evaluate Robustness | To determine the method's resilience to small, deliberate changes in parameters. | Vary key parameters (e.g., temperature, humidity, input voltage) within a expected operating range and monitor the impact on results [8]. |

| 7. Document & Approve | To generate objective evidence that the method is fit for its intended use. | Compile a TMV Report including protocol, raw data, analysis, and conclusion. Obtain formal approval before releasing the method for use [8]. |

The workflow for establishing a validated test method, from definition to documentation, is systematized as follows:

The Validation Lifecycle: Process Validation in Six Sigma

For processes that are consistently executed, such as manufacturing a drug substance, a lifecycle approach to validation is required. Process validation is defined as the collection and evaluation of data, from the process design stage through commercial production, which establishes scientific evidence that a process is capable of consistently delivering a quality product [13]. This aligns with the FDA's guidance and is effectively implemented using the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) framework from Six Sigma [13].

The Three Stages of Process Validation

The lifecycle model consists of three integrated stages:

- Process Design: Building quality into the process through development and scale-up. Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) are identified. Tools like Design of Experiments (DOE) and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) are used to understand and mitigate risks [13].

- Process Qualification: Confirming the process design is effective during commercial manufacturing. This includes equipment qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ) and Process Performance Qualification (PPQ) to demonstrate consistency [13].

- Continued Process Verification: Maintaining the validated state through ongoing monitoring. Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts are used to detect process shifts, ensuring long-term control and enabling continuous improvement [13].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected, lifecycle nature of process validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential "reagents" or tools in the validation scientist's toolkit, which are critical for executing the protocols and techniques described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

| Tool / Solution | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GAMP 5 Framework [7] | A risk-based framework for classifying and validating computerized systems, crucial for regulatory compliance. | Categorizing software from infrastructure (Cat. 1) to custom (Cat. 5) and defining appropriate validation rigor for each [7]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., JMP, R) | Used for conducting Gage R&R studies, regression analysis, capability analysis (Cp, Cpk), and creating control charts. | Analyzing measurement system variation in TMV and monitoring process performance in Continued Process Verification [13] [12]. |

| JSON Schema / XML Schema | A declarative language for defining the expected structure, data types, and constraints of data payloads. | Implementing automated input validation for APIs and web services to ensure data quality and security [9]. |

| Validation Manager Software [12] | A specialized platform for planning, executing, and documenting analytical method comparisons and instrument verifications. | Automating data management and report generation for quantitative comparisons, such as bias estimation using Bland-Altman plots [12]. |

| Pydantic / Joi Libraries [9] | Programming libraries for implementing type and constraint validation logic within application code. | Ensuring data integrity in Python (Pydantic) or Node.js (Joi) applications by validating data types, ranges, and custom business rules [9]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | A system for digitally capturing and managing experimental data and metadata, supporting data integrity principles. | Providing an audit trail for TMV protocols and storing raw validation data, ensuring ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate) [7]. |

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into healthcare is transforming drug development, medical device innovation, and patient care. These technologies can derive novel insights from the vast amounts of data generated daily within healthcare systems [14]. However, their adaptive, complex, and often opaque nature challenges traditional regulatory paradigms. Consequently, major regulatory bodies, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), have developed specific frameworks and guidelines to ensure that AI/ML technologies used in medical products and drug development are safe, effective, and reliable [14] [15]. For researchers and scientists, understanding these perspectives is crucial for navigating the path from innovation to regulatory approval. This document outlines the core regulatory principles, summarizes them for easy comparison, and provides actionable experimental protocols for validating AI systems within this evolving landscape, with a specific focus on input-output transformation validation methods.

United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approach

The FDA's approach to AI has evolved significantly, moving from a traditional medical device regulatory model to one that accommodates the unique lifecycle of AI/ML technologies. The agency recognizes that the greatest potential of AI lies in its ability to learn from real-world use and improve its performance over time [14]. A key development was the 2019 discussion paper and subsequent "Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan" published in January 2021, which laid the groundwork for a more adaptive regulatory pathway [14].

The FDA's current strategy is articulated through several key guidance documents and principles:

- Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP): The FDA, in collaboration with other partners, has outlined guiding principles for Good Machine Learning Practice in medical device development [14].

- Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCP): A pivotal concept introduced by the FDA is the Predetermined Change Control Plan, which allows manufacturers to pre-specify certain types of modifications to an AI-enabled device—such as performance enhancements or bias mitigation—and the protocols for implementing them, without necessitating a new marketing submission for each change [14] [16]. A final guidance on marketing submission recommendations for a PCCP was issued in December 2024 [14].

- Lifecycle Management: In January 2025, the FDA released a draft guidance titled "Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Device Software Functions: Lifecycle Management and Marketing Submission Recommendations." This document provides comprehensive recommendations for the total product life cycle of AI-enabled devices, from pre-market development to post-market monitoring [14] [16]. It emphasizes a risk-based approach, transparency, and the management of issues like bias and data drift [16].

- Cross-Center Coordination: The FDA has adopted a coordinated approach across its centers—CBER, CDER, CDRH, and OCP—to drive alignment and share learnings on AI applicable to all medical products [14] [17].

For drug development specifically, the FDA's CDER has established a CDER AI Council to oversee and coordinate activities related to AI, reflecting the significant increase in drug application submissions using AI components [17]. In January 2025, the FDA also released a separate draft guidance, "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products," which provides a risk-based credibility assessment framework for AI models used in this context [18] [17].

European Medicines Agency (EMA) Approach

The EMA views AI as a key tool for leveraging large volumes of health data to encourage research, innovation, and support regulatory decision-making [15]. The agency's strategy is articulated through the workplan of the Network Data Steering Group for 2025-2028, which focuses on four key AI-related areas: guidance and policy, tools and technology, collaboration and change management, and structured experimentation [15].

Key EMA outputs include:

- Reflection Paper on AI: In September 2024, the CHMP and CVMP adopted a reflection paper on the use of AI in the medicinal product lifecycle. This paper provides considerations for medicine developers to use AI and ML in a safe and effective way at different stages of a medicine's life [15].

- Annex 22 on AI in GxP: In a landmark move in July 2025, the EMA, via the GMDP Inspectors Working Group, published a draft of Annex 22 as part of the updates to EudraLex Volume 4. This is the first dedicated GxP framework for AI and ML systems used in the manufacture of active substances and medicinal products [19] [20]. Annex 22 sets clear expectations for intended use documentation, performance validation, independent testing, explainability, and qualified human oversight [19]. It explicitly excludes dynamic or generative AI models from critical applications, emphasizing consistency and accountability [19].

- Large Language Model (LLM) Guiding Principles: The EMA and HMA have also published guiding principles for the use of large language models by regulatory network staff, promoting safe, responsible, and effective use of this technology [15].

- AI Observatory: The EMA has established an AI Observatory to capture and share experiences and trends in AI, which includes horizon scanning and an annual report [15].

The EMA's approach, particularly with Annex 22, integrates AI regulation into the existing GxP framework, requiring that AI systems be governed by the same principles of quality, validation, and accountable human oversight that apply to other computerized systems and processes [19] [20].

Comparative Analysis of FDA and EMA Guidelines

The following tables provide a structured comparison of the regulatory approaches and technical requirements of the FDA and EMA regarding AI in healthcare and drug development.

Table 1: Core Regulatory Focus and Application Scope

| Aspect | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | European Medicines Agency (EMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Safety & effectiveness of AI as a medical product or tool supporting drug development [14] [18]. | Use of AI within the medicinal product lifecycle & GxP processes [15] [20]. |

| Governing Documents | AI/ML SaMD Action Plan; Good MLP Principles; Draft & Final Guidances on PCCP & Lifecycle Management (2023-2025) [14] [16]. | Reflection Paper on AI (2024); Draft Annex 22 to GMP (2025); Revised Annex 11 & Chapter 4 [15] [19] [20]. |

| Regulatory Scope | AI-enabled medical devices (SaMD, SiMD); AI to support regulatory decisions for drugs & biologics [14] [18]. | AI used in drug manufacturing (GxP environments); AI in the broader medicinal product lifecycle [15] [20]. |

| Core Paradigm | Risk-based, Total Product Life Cycle (TPLC) approach [16]. | Risk-based, integrated within existing GxP quality systems [19] [20]. |

| Key Mechanism for Adaptation | Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) [14] [16]. | Formal change control under quality management system (QMS) [20]. |

Table 2: Technical and Validation Requirements for Input-Output Transformation

| Requirement | FDA Perspective | EMA Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Validation | Confirmation through objective evidence that device meets intended use [16]. Must reflect real-world conditions [21]. | Validation against predefined metrics; integrated into computerized system validation [19] [20]. |

| Data Management | Data diversity & representativeness; prevention of data leakage; ALCOA+ principles for data integrity [21] [16]. | GxP standards for data accuracy, integrity, and traceability [19] [20]. |

| Transparency & Explainability | Critical information must be understandable/accessible; "black-box" nature must be addressed [16]. | Decisions must be subject to qualified human review; explainability required [19] [20]. |

| Bias Control & Management | Address throughout lifecycle; ensure data reflects intended population; proactive identification of disparities [16]. | Implied through requirements for data quality, representativeness, and validation [19]. |

| Lifecycle Monitoring | Ongoing performance monitoring for drift; continuous validation [21] [16]. | Continuous oversight to detect performance drift; formal change control for updates [20]. |

| Human Oversight | "Human-AI team" performance evaluation encouraged (e.g., reader studies) [16]. | Qualified human review mandatory for critical decisions; accountability cannot be transferred to AI [19] [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Regulatory Validation

This section provides detailed methodological protocols for key experiments and studies required to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of AI systems, aligning with FDA and EMA expectations for input-output transformation validation.

Protocol 1: Model Validation and Performance Benchmarking

1. Objective: To rigorously assess the performance, robustness, and generalizability of an AI model using independent datasets, ensuring it meets predefined performance criteria for its intended use.

2. Background: Regulatory agencies require that AI models be validated on datasets that are independent from the training data to provide an unbiased estimate of real-world performance and to ensure the model is generalizable across relevant patient demographics and clinical settings [16].

3. Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AI Validation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Curated Training Dataset | Used for initial model development and parameter tuning. Must be well-characterized and documented. |

| Independent Validation Dataset | A held-aside dataset used for unbiased performance estimation. Must be statistically independent from the training set. |

| External Test Dataset | Data collected from a different source or site than the training data, used to assess generalizability. |

| Data Annotation Protocol | Standardized procedure for labeling data, ensuring consistency and quality of ground truth labels. |

| Performance Metric Suite | A set of quantitative measures (e.g., AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score) to evaluate model performance. |

4. Methodology:

- 4.1. Data Segmentation: Partition available data into three distinct sets: Training Set (~70%), Validation Set (~15%), and Hold-out Test Set (~15%). Ensure stratification to maintain distribution of key variables (e.g., disease severity, demographics) across sets.

- 4.2. Subgroup Analysis: Define and analyze performance metrics for critical subgroups based on age, sex, ethnicity, disease subtype, and imaging equipment to identify potential performance disparities and bias [16].

- 4.3. Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate all predefined performance metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Perform statistical significance testing (e.g., McNemar's test) to compare model performance against a baseline or comparator, if applicable.

- For diagnostic tools, conduct a reader study to evaluate the "human-AI team" performance compared to either alone [16].

5. Data Analysis: The model is deemed to have passed validation if all primary performance metrics meet or exceed the pre-specified success criteria on the independent test set and across all major subgroups, demonstrating robustness and lack of significant bias.

Protocol 2: Monitoring for Data and Concept Drift

1. Objective: To establish a continuous, post-market surveillance system for detecting and quantifying data drift and concept drift that may degrade AI model performance in real-world use.

2. Background: AI models are sensitive to changes in input data distribution (data drift) and changes in the relationship between input and output data (concept drift) [22] [16]. The FDA and EMA expect ongoing lifecycle monitoring to ensure sustained safety and effectiveness [22] [21].

3. Materials and Reagents:

- Incoming Real-World Data Stream: Data from the deployed clinical environment.

- Baseline Data Statistical Profile: The statistical properties (e.g., mean, variance, distribution) of the data used for model training and initial validation.

- Automated Monitoring Dashboard: A tool for visualizing key drift metrics and triggering alerts.

4. Methodology:

- 4.1. Establish Baseline: Characterize the reference training data by calculating feature distributions, summary statistics, and correlation matrices to create a baseline profile.

- 4.2. Define Drift Thresholds: Set statistically driven thresholds for triggering alerts. For example, a significant change in a feature's distribution using the Population Stability Index (PSI) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test.

- 4.3. Implement Monitoring:

- 4.4. Root Cause Analysis: Upon triggering a drift alert, initiate an investigation to identify the cause (e.g., change in clinical protocol, new patient population, shift in data acquisition hardware/software).

5. Data Analysis: Regularly report drift metrics and performance KPIs. A confirmed, significant drift that negatively impacts performance should trigger the model's retraining protocol, which is governed by the Predetermined Change Control Plan (for FDA) or formal change control process (for EMA) [16] [20].

Protocol 3: Human Factors and Usability Validation

1. Objective: To evaluate the usability of the AI system's interface and ensure that the intended users can interact with the system safely and effectively to achieve the intended clinical outcome.

2. Background: The FDA requires human factors and usability studies for medical devices to minimize use errors [16]. The EMA's Annex 22 mandates that decisions made or proposed by AI must be subject to qualified human review, making the human-AI interaction critical [20].

3. Methodology:

- 4.1. Formative Studies: Conduct early-stage testing with a small group of representative users (e.g., clinicians, radiologists) to identify and rectify usability issues in the design phase.

- 4.2. Summative Validation Study: Perform a simulated-use study with a larger group of participants. Provide them with realistic clinical tasks that involve using the AI system's output to make a decision.

- 4.3. Data Collection: Record all use errors, near misses, and subjective feedback. Measure task success rate, time-on-task, and the user's mental workload (e.g., using NASA-TLX scale).

- 4.4. "Human-AI Team" Performance Assessment: As encouraged by the FDA, compare the diagnostic or decision-making accuracy of the user alone, the AI system alone, and the user assisted by the AI system [16].

5. Data Analysis: The validation is successful if all critical tasks are completed without recurring, unmitigated use errors that could harm the patient, and the "human-AI team" demonstrates non-inferiority or superiority to the human alone.

Visualization of Regulatory Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for navigating the FDA and EMA regulatory pathways for AI-enabled technologies, highlighting the parallel processes and key decision points.

Diagram 1: AI Regulatory Pathways

Diagram 2: AI Validation Lifecycle

In pharmaceutical research and development, the principles of verification and validation (V&V) are foundational to ensuring product quality and regulatory compliance. These processes represent a systematic approach to input-output transformation, where user needs are transformed into a final product that is both high-quality and fit for its intended use. Verification confirms that each transformation step correctly implements the specified inputs, while validation demonstrates that the final output meets the original user needs and intended uses in a real-world environment [23] [24]. This framework is crucial for drug development professionals who must navigate complex regulatory landscapes while bringing safe and effective products to market.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Verification: Building it Right

Design verification is defined as "confirmation by examination and provision of objective evidence that specified requirements have been fulfilled" [23] [24]. In essence, verification answers the question: "Did we build the product right?" by ensuring that design outputs match the design inputs specified during development [24]. This process involves checking whether the product conforms to technical specifications, standards, and regulations through rigorous testing at the subsystem level.

Verification activities typically include:

- Reviewing design documents and specifications

- Conducting technical inspections

- Performing bench testing and static analysis

- Executing component-level functional tests [24]

Validation: Building the Right Thing

Design validation is defined as "establishing by objective evidence that device specifications conform with user needs and intended use(s)" [23] [24]. Validation answers the question: "Did we build the right product?" by demonstrating that the final product meets the user requirements and is suitable for its intended purpose in actual use conditions [24]. This process focuses on the user's interaction with the complete system in real-world environments.

Validation activities typically include:

- Conducting functional and performance testing

- Executing usability studies and clinical evaluations

- Performing real-world environment testing

- Assessing biocompatibility and safety [24]

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Verification and Validation

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | Did we build it right? | Did we build the right thing? |

| Focus | Design outputs vs. design inputs | Device specifications vs. user needs |

| Timing | During development | Typically at development completion |

| Methods | Reviews, inspections, bench testing | Real-world testing, clinical trials, usability studies |

| Scope | Sub-system level components | Complete system in operational environment |

| Output | Review reports, inspection records | Test reports, acceptance documentation [23] [24] |

Regulatory Context in Pharmaceutical Development

Analytical Methodology Framework

In pharmaceutical development, the V&V framework extends to analytical methods with precise regulatory definitions:

Validation: Formal demonstration that an analytical method is suitable for its intended use, producing reliable, accurate, and reproducible results across a defined range. Required for methods used in routine quality control testing of drug substances, raw materials, or finished products [25].

Verification: Confirmation that a previously validated method works as expected in a new laboratory or under modified conditions. This is typically required for compendial methods (USP, Ph. Eur.) adopted by a new facility [25].

Qualification: Early-stage evaluation of an analytical method's performance during development phases (preclinical or Phase I trials) to demonstrate the method is likely reliable before full validation [25].

FDA and ICH Requirements

Regulatory bodies including the FDA and EMA require well-documented V&V plans, test protocols, and results to ensure devices meet requirements and are fit for use [23]. For analytical methods, the ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides the definitive framework for validation parameters, which must be thoroughly documented to support regulatory submissions and internal audits [25].

Table 2: Analytical Method V&V Approaches in Pharmaceutical Development

| Approach | When Used | Key Parameters | Regulatory Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method Validation | For release testing, stability studies, batch quality assessment | Accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range, LOD, LOQ, robustness | ICH Q2(R1), FDA requirements for decision-making |

| Method Verification | Adopting established methods in new labs or for similar products | Limited assessment of accuracy, precision, specificity | Confirmation of compendial method performance |

| Method Qualification | Early development when full validation not yet required | Specificity, linearity, precision optimization | Supports development decisions before validation |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Design Verification Process

Objective: To confirm that design outputs meet all specified design input requirements.

Materials and Reagents:

- Complete set of design input specifications

- Design history file including all outputs

- Verification test equipment and instrumentation

- Documented verification protocol

Methodology:

- Requirements Mapping: Trace each design input to corresponding design outputs

- Inspection Protocol: Examine components against technical specifications

- Bench Testing: Perform functional tests on subsystems

- Analysis: Compare test results against acceptance criteria

- Documentation: Record all verification activities and results

Acceptance Criteria: All design outputs must conform to design input requirements with objective evidence documented for each requirement [24].

Protocol 2: Design Validation Process

Objective: To establish by objective evidence that device specifications conform to user needs and intended uses.

Materials and Reagents:

- Defined user needs and intended use statements

- Final device specification document

- Validation test protocol approved by quality unit

- Real-world simulated use environment

Methodology:

- User Needs Assessment: Confirm traceability from user needs to design specifications

- Real-World Testing: Evaluate device in simulated use environment

- Performance Testing: Assess device under actual use conditions

- Usability Evaluation: Conduct studies with intended users

- Data Analysis: Compare results against user need requirements

Acceptance Criteria: Device must perform as intended for its defined use with all user needs met under actual use conditions [24].

Protocol 3: Analytical Method Verification

Objective: To verify that a compendial method performs as expected when implemented in a new laboratory.

Materials and Reagents:

- Reference standards with documented purity

- Compendial method documentation (USP, Ph. Eur.)

- Qualified instrumentation and equipment

- Appropriate chemical reagents and solvents

Methodology:

- System Suitability: Confirm the system meets compendial requirements

- Precision Assessment: Perform six replicate injections of standard preparation

- Accuracy Evaluation: Spike placebo with known analyte quantities (80%, 100%, 120%)

- Specificity Verification: Demonstrate analytical response is from analyte alone

- Report Results: Compare obtained values against acceptance criteria

Acceptance Criteria: Method performance must meet predefined acceptance criteria for accuracy, precision, and specificity as defined in the verification protocol [25].

Visualization of V&V Workflows

Input-Output Transformation Model

Input-Output Transformation V&V Model: This diagram illustrates the sequential transformation from user needs to final product, with verification and validation checkpoints ensuring correctness and appropriateness at each stage.

Pharmaceutical Analytical Method Decision Framework

Analytical Method Decision Framework: This workflow provides a systematic approach for drug development professionals to determine the appropriate methodology pathway based on method novelty, regulatory status, and development phase.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for V&V Activities

| Material/Reagent | Function in V&V | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provide known purity materials for method accuracy determination | Analytical method validation and verification |

| System Suitability Test Materials | Verify chromatographic system performance before analysis | HPLC/UPLC method validation and verification |

| Placebo Formulation | Assess method specificity and interference | Analytical method validation for drug products |

| Certified Calibration Equipment | Ensure measurement accuracy and traceability | Device performance verification |

| Biocompatibility Test Materials | Evaluate biological safety of device materials | Medical device validation for regulatory submission |

| Stability Study Materials | Assess method and product stability under various conditions | Forced degradation and shelf-life studies |

The distinction between verification and validation is fundamental to successful pharmaceutical development and regulatory compliance. Verification ensures that products are built correctly according to specifications, while validation confirms that the right product has been built to meet user needs. The input-output transformation framework provides a systematic approach for researchers and drug development professionals to implement these processes effectively throughout the product lifecycle. By adhering to the detailed protocols and decision frameworks outlined in these application notes, organizations can enhance product quality, reduce development risks, and streamline regulatory approvals.

In the landscape of modern drug development, the validation of input-output transformations is a cornerstone of scientific and regulatory credibility. This process ensures that the data entering analytical systems emerges as reliable, actionable knowledge. At the heart of this validation lie three critical data quality dimensions: Completeness, Consistency, and Integrity. These are not isolated attributes but interconnected pillars that collectively determine whether a dataset is fit-for-purpose, especially within highly regulated pharmaceutical research and development [26] [27]. For researchers and scientists, mastering these dimensions is fundamental to reconstructing the data lineage from raw inputs to polished outputs, thereby safeguarding patient safety and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions [28].

The consequences of neglecting data quality are severe, ranging from financial losses and regulatory actions to direct risks to patient safety [27]. Furthermore, with the increasing integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in drug discovery and manufacturing, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" becomes ever more critical. The efficacy of AI models is entirely contingent on the quality of the data on which they are trained and operated, making rigorous data quality practices a prerequisite for trustworthy AI-driven innovation [29]. This application note details the protocols and best practices for ensuring these foundational data quality dimensions within the context of input-output transformation validation.

Core Data Quality Dimensions in Pharmaceutical Research

For data to be considered high-quality in a regulatory and research context, it must excel across multiple dimensions. The following table summarizes the six core dimensions of data quality, with a focus on the three pillars of this discussion [27]:

Table 1: Core Data Quality Dimensions for Drug Development

| Dimension | Definition | Impact on Drug Development & Research |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness | The presence of all necessary data required to address the study question, design, and analysis [26]. | Prevents bias in study populations and outcomes; ensures sufficient data for robust statistical analysis [26]. |

| Consistency | The stability and uniformity of data across sites, over time, and across linked datasets [26]. | Ensures that analytics correctly capture the value of data; discrepancies can indicate systemic errors [27]. |

| Integrity | The maintenance of accuracy, consistency, and traceability of data over its entire lifecycle, including correct attribute relationships across systems [28] [27]. | Ensures that all enterprise data can be traced and connected; foundational for audit trails and regulatory compliance [28]. |

| Accuracy | The level to which data correctly represents the real-world scenario it is intended to depict and confirms to a verifiable source [27]. | Powers factually correct reporting and trusted business decisions; critical for patient safety and dosing [27]. |

| Uniqueness | A measure that the data represents a single, non-duplicated instance within a dataset [27]. | Ensures no duplication or overlaps, which is critical for accurate patient counts and inventory management. |

| Validity | The degree to which data conforms to the specific syntax (format, type, range) of its definition [27]. | Guarantees that data values align with the expected domain, such as valid ZIP codes or standard medical terminologies. |

The ALCOA+ framework, mandated by regulators, provides a practical set of principles for achieving data integrity, which encompasses completeness, consistency, and accuracy. It stipulates that data must be Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate, with the "plus" adding that it must also be Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [28] [30]. Adherence to ALCOA+ is a primary method for ensuring data quality throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Experimental Protocols for Data Quality Validation

Validating data quality requires a multi-layered testing strategy. The following protocols can be integrated into data pipeline development to verify and validate transformations.

Protocol for Schema and Metadata Validation

This protocol ensures the structural integrity of data before and after transformations.

- Objective: To enforce that incoming and transformed data conform to expected schemas, data types, and constraints [31].

- Materials:

- JSON Schema or Apache Avro: For defining and enforcing expected data structures.

- Validation Framework: Such as Great Expectations or Pydantic in Python.

- Business Rules Document: A pre-defined list of domain-specific constraints (e.g., value ranges, mandatory fields).

- Methodology:

- Schema Definition: Formally define the expected schema for input data, including data types (string, integer), formats (email, date), and nullability.

- Validation Checkpoint: Implement a validation step early in the data pipeline, ideally as middleware or a pre-processing hook [9].

- Rule Execution: The system checks all incoming data against the defined schema and business rules.

- Exception Handling: Data that fails validation is routed to a quarantine area for review, and an error is logged. The process should not proceed until the data is corrected or its rejection is confirmed [9].

- Output: A validation report detailing the number of records processed, records failed, and specific errors for each failed record (e.g., "Field 'patient_age': value '-5' is less than minimum (0)") [9].

Protocol for Unit and Integration Testing of Data Transformations

This protocol verifies the correctness of the transformation logic itself.

- Objective: To validate specific transformation functions (unit tests) and several transformations working together (integration tests) using known input-output pairs [31].

- Materials:

- Testing Framework: PyTest (Python), JUnit (Java).

- Test Harness: A controlled environment, potentially using Docker, to mimic pipeline steps.

- Golden Datasets: Small, curated datasets with known inputs and expected outputs.

- Methodology:

- Unit Test Creation: For each discrete transformation function (e.g., a function that normalizes laboratory unit names), write tests with known inputs and expected outputs.

- Parameterized Testing: Use the testing framework to run the same test logic with multiple input-output pairs from the golden dataset.

- Integration Test Creation: Construct tests that execute a sequence of transformations, simulating a segment of the full pipeline.

- Test Execution and Regression: Integrate tests into a continuous integration (CI) system to run automatically, ensuring that new code changes do not break existing transformation logic (regression testing) [31].

- Output: A test execution report showing pass/fail status for all tests. Failed tests indicate a logic error in the transformation code that must be investigated.

Protocol for Data Integrity and Consistency Auditing

This protocol ensures the ongoing integrity and consistency of data throughout its lifecycle.

- Objective: To verify that data remains accurate, consistent, and traceable after storage and across systems, in line with ALCOA+ principles [28].

- Materials:

- Automated Audit Trail System: A secure, time-stamped electronic record that tracks the creation, modification, or deletion of any data [28].

- Data Comparison Tools: Scripts or software (e.g., custom Python/R scripts, Diff utilities) to compare data across systems.

- Access to Source Systems: The ability to trace data back to its original source.

- Methodology:

- Audit Trail Review: Periodically sample records and use the audit trail to reconstruct their entire history, verifying that all changes are attributable and justified.

- Cross-System Consistency Check: For data stored in multiple locations (e.g., a clinical database and a data warehouse), run scripts to compare key records and ensure values match.

- Traceability Verification: Select a final analysis result (output) and trace it backward through the transformation pipelines to the original source data (input), ensuring no breaks in lineage.

- Output: An audit report confirming data integrity or highlighting discrepancies found in the audit trail, cross-system checks, or traceability verification.

The logical workflow for implementing these validation protocols is summarized in the following diagram:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Data Quality

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Data Quality Assurance

| Category / Tool | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Schema Enforcement | JSON Schema, Apache Avro, XML Schema | Defines the expected structure, format, and data types for input and output data, enabling automated validation of completeness and validity [9] [31]. |

| Testing Frameworks | PyTest (Python), JUnit (Java), NUnit (.NET) | Provides the infrastructure to build and run unit and integration tests, verifying the correctness of data transformation logic against known inputs and outputs [31]. |

| Data Profiling & Validation | Great Expectations, Pandas Profiling, Deequ | Libraries that automatically profile datasets to generate summaries and validate data against defined expectations, checking for accuracy, consistency, and uniqueness [31]. |

| Audit Trail Systems | Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) systems, Database triggers, Version control (e.g., Git) | Creates a secure, time-stamped record of all data-related actions, ensuring integrity by making data changes attributable and traceable, a core requirement of ALCOA+ [28]. |

| Reference Data | Golden Datasets, Standardized terminologies (e.g., CDISC, IDMP) | A trusted, curated set of data used as a baseline to compare transformation outputs, serving as a benchmark for accuracy and a tool for regression testing [31]. |

In the rigorous world of drug development, where decisions directly impact human health, there is no room for ambiguous or unreliable data. The principles of Completeness, Consistency, and Integrity form an indissoluble chain that protects the validity of input-output transformations from the laboratory bench to regulatory submission. By implementing the structured protocols and tools outlined in this application note—from schema validation and unit testing to comprehensive integrity auditing—researchers and scientists can build a robust defense against data corruption and bias.

This disciplined approach to data quality is the bedrock upon which trustworthy analytics, credible AI models, and ultimately, safe and effective medicines are built. As regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA increasingly focus on data governance, mastering these fundamentals is not just a scientific best practice but a regulatory imperative for bringing new therapies to market [29] [32].

From Theory to Pipeline: A Practical Toolkit for Implementation

In the context of input-output transformation validation methods research, structural validation refers to the systematic enforcement of predefined rules governing the organization, format, and relationships within data. This process ensures that data adheres to consistent structural patterns, which is a critical prerequisite for reliable data transformation and analysis. For researchers and scientists, particularly in drug development where data integrity is paramount, implementing robust structural validation frameworks guarantees that input data quality is maintained throughout complex processing pipelines, leading to trustworthy, reproducible outputs.

Structural metadata serves as the foundational blueprint for this validation process. It defines the organizational elements that describe how data is structured within a dataset or system, including data relationships, formats, hierarchical organization, and integrity constraints [33]. In scientific computing and data analysis, this translates to enforcing consistent structures in instrument data outputs, experimental metadata, and clinical trial data, ensuring all downstream consumers—whether automated algorithms or research professionals—can correctly interpret and utilize the information.

Core Principles of Structural Validation

Schema Validation Fundamentals

Schema validation ensures incoming data structures match expected patterns before processing. Using JSON Schema, XML Schema, or Protocol Buffer schemas, researchers can define exact specifications for their API communications or data file formats [9]. This preemptive validation prevents malformed data from entering analytical systems, protecting the integrity of scientific computations.

A typical JSON schema for an experimental metadata might define:

Type Checking and Data Coercion

Type checking verifies data matches expected formats, preventing critical errors such as numerical calculations on string data or inserting text into numeric database fields [9]. In scientific contexts, where data may originate from multiple instrument sources, explicit type validation with clear error messages is essential for maintaining data quality.

Content Validation Strategies

Content validation ensures actual data values are acceptable through:

- Pattern matching (using regular expressions for identifier formats)

- Format validation (ensuring dates, numerical values fall within expected ranges)

- Range checking (verifying numerical values adhere to physiological or instrument limits)

- Business logic validation (ensuring data relationships make scientific sense)

The most effective approach is whitelisting (allowlisting), which defines exactly what's permitted and rejects everything else, as recommended by OWASP security guidelines [9].

Contextual and Semantic Validation

Contextual validation applies domain-specific business logic rules beyond basic syntax checking. In drug development, this might include verifying that clinical trial start dates precede end dates, that dosage values fall within established safety ranges, or that patient identifier codes follow institutional formatting standards [9].

Validation Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol Buffer Schema Validation

For high-performance scientific data exchange, Protocol Buffer schema validation ensures encoded messages conform to expected structures. The validation process follows a rigorous methodology [34]:

- Message Descriptor Lookup: The schema registry retrieves Key and Value message descriptors by name

- Record Iteration: Each record in a data batch undergoes validation

- Key Validation: Validates key bytes against the key descriptor if present

- Value Validation: Validates value bytes against the value descriptor if present

- Deserialization: Uses

CodedInputStreamto parse bytes into message instances - Error Handling: Any deserialization failure returns

ErrorCode::InvalidRecord

Table 1: Protocol Buffer Validation Behavior Matrix

| Scenario | Key Schema | Value Schema | Record Key | Record Value | Validation Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete validation | Present | Present | Must match | Must match | Validated |

| Value-only validation | Absent | Present | Any bytes | Must match | Validated |

| Key-only validation | Present | Absent | Must match | Any bytes | Validated |

| No schema defined | Absent | Absent | Any bytes | Any bytes | Passes (no-op) |

| Missing required key | Present | - | None | - | InvalidRecord |

| Corrupted value data | - | Present | - | Invalid | InvalidRecord |

Implementation code for Protocol Buffer validation follows this pattern [34]:

JSON Schema Validation Protocol

For research data management, JSON schema validation enforces consistent structure for experimental metadata. The implementation protocol involves [35]:

- Schema Definition: Create a JSON schema defining required metadata structure

- Schema Registration: Apply the schema to the project or data system

- Validation Enforcement: Configure data upload processes to validate against schema

- Error Handling: Capture and report validation failures with specific field-level details

A typical experimental workflow implements this as:

Input/Output Validation Security Protocol

Input/output validation serves as a critical security measure in research data pipelines, protecting against data corruption and injection attacks. The security validation protocol includes [9]:

- Schema Validation: Apply JSON Schema or similar validation early in request processing

- Type Checking: Verify data types match expected formats

- Size and Range Validation: Prevent resource exhaustion attacks with appropriate limits

- Content Sanitization: Remove or escape potentially harmful content

- Output Encoding: Ensure safe data rendering in outputs

Table 2: Input Validation Techniques for Scientific Data Systems

| Technique | Implementation | Security Benefit | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schema Validation | JSON Schema, Protobuf | Rejects malformed data | Ensures instrument data conformity |

| Type Checking | Runtime type verification | Prevents type confusion errors | Maintains data type integrity |

| Range Checking | Minimum/maximum values | Prevents logical errors | Validates physiologically plausible values |

| Content Whitelisting | Allow-only approach | Blocks unexpected formats | Ensures data domain compliance |

| Output Encoding | Context-aware escaping | Prevents injection attacks | Secures data visualization |

Quantitative Validation Metrics and Performance

Validation systems require comprehensive metrics and observability to ensure performance and reliability. The Tansu validation framework implements these key metrics [34]:

registry_validation_duration: Histogram tracking latency of validation operations in millisecondsregistry_validation_error: Counter tracking validation failures with reason labels

Table 3: Validation Performance Metrics

| Metric Name | Type | Unit | Labels | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| validation_duration | Histogram | milliseconds | topic, schema_type | Latency of validation operations |

| validation_success | Counter | count | topic, schema_type | Count of successful validations |

| validation_error | Counter | count | topic, reason | Count of validation failures by cause |

| batch_size | Histogram | records | topic | Distribution of validated batch sizes |

Performance optimization strategies include:

- Schema Caching: Reduces latency by caching compiled schemas in memory [35]

- Batch Validation: Processes multiple records simultaneously for throughput [34]

- Early Rejection: Fails fast on first validation error to conserve resources [9]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Validation Methodology Implementation

| Reagent Solution | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| JSON Schema Validator | Validates JSON document structure against schema definitions | ajv (JavaScript), jsonschema (Python) [9] |

| Protocol Buffer Compiler | Generates data access classes from .proto definitions | protoc with language-specific plugins [36] |

| Avro Schema Validator | Validates binary Avro data against JSON-defined schemas | Apache Avro library for JVM/Python/C++ [34] |

| XML Schema Processor | Validates XML documents against W3C XSD schemas | Xerces (C++/Java), lxml (Python) |

| Data Type Enforcement Library | Runtime type checking for dynamic languages | Joi (JavaScript), Pydantic (Python) [9] |

Validation Workflow Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the complete validation workflow for scientific data processing, from input through transformation to output:

Scientific Data Validation Workflow

Error Handling and Quality Assurance

Robust error handling is essential for maintaining research data quality. Validation failures should be reported through standardized error systems with specific error codes [34]:

InvalidRecord: Message fails schema validationSchemaValidation: Generic validation failureProtobufJsonMapping: JSON-to-Protobuf conversion failsAvro: Avro schema or encoding error

Error responses should follow consistent formats that help researchers identify and resolve issues without exposing system internals [9]:

Quality assurance protocols for validation systems include:

- Schema Versioning: Track changes to validation rules over time

- Backward Compatibility Testing: Ensure new schemas don't break existing valid data

- Validation Test Coverage: Verify validation rules with comprehensive test suites

- Performance Monitoring: Track validation latency and failure rates

- Error Analytics: Categorize and analyze validation failures to improve data quality

Schema and metadata validation provides the critical foundation for ensuring structural consistency in scientific data systems. By implementing the methodologies and protocols outlined in this document, research organizations can establish robust frameworks for maintaining data quality throughout complex input-output transformation pipelines. The rigorous application of structural validation principles enables drug development professionals and researchers to trust their analytical outputs, supporting reproducible science and regulatory compliance while preventing data corruption and misinterpretation. As research data systems grow in complexity and scale, these validation methodologies will become increasingly essential components of the scientific computing infrastructure.

Unit and Integration Testing for Isolated and Combined Transformation Logic

In the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, the validation of input-output transformation logic is a critical pillar of quality assurance. This process ensures that every unit operation, whether examined in isolation or as part of an integrated system, consistently produces outputs that meet predetermined specifications and quality attributes. The methodology is foundational to demonstrating that manufacturing processes consistently deliver products that are safe, effective, and of high quality, thereby satisfying stringent regulatory requirements from bodies like the FDA and EMA [13] [37]. The approach is bifurcated: unit testing verifies the logic of individual components in isolation, while integration testing confirms that these components interact correctly to transform inputs into the desired final output [38] [39]. Adopting this structured, layered testing strategy is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a scientific imperative for building quality into products from the ground up [40].

Quantitative Comparison of Testing Methodologies

A clear understanding of the distinct yet complementary roles of unit and integration testing is essential for designing a robust validation strategy. The following table summarizes their key characteristics, providing a framework for their strategic application.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Unit and Integration Testing for Transformation Logic

| Characteristic | Unit Testing | Integration Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Scope & Objective | Individual components/functions in isolation; validates internal logic and algorithmic correctness [38] [41]. | Multiple connected components; validates data flow, interfaces, and collaborative behavior [42] [38]. |

| Dependencies | Uses mocked or stubbed dependencies to achieve complete isolation of the unit under test [38] [39]. | Uses actual dependencies (e.g., databases, APIs) or highly realistic simulations [38] [41]. |

| Primary Focus | Functional accuracy of a single unit, including edge cases and error handling [39]. | Interaction defects, data format mismatches, and communication failures between modules [43] [39]. |

| Execution Speed | Very fast (milliseconds per test), enabling a rapid developer feedback loop [39] [41]. | Slower (seconds to minutes) due to the overhead of coordinating multiple components and systems [38] [39]. |

| Error Detection | Catches logic errors, boundary value issues, and algorithmic flaws within a single component [39]. | Identifies interface incompatibilities, data corruption in flow, and misconfigured service connections [43] [38]. |

| Ideal Proportion in Test Suite | ~70% (Forms the broad base of the test pyramid) [41]. | ~20% (The supportive middle layer of the test pyramid) [41]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

This section delineates the detailed, actionable protocols for implementing unit and integration tests, providing a clear roadmap for researchers and validation scientists.

Protocol for Unit Testing

Objective: To verify the internal transformation logic of a single, isolated function or method, ensuring it produces the correct output for a given set of inputs, independent of any external systems [39].

Methodology: The unit testing protocol follows a precise, multi-stage process to ensure thoroughness and reliability.

Table 2: Unit Testing Protocol Steps and Requirements

| Step | Description | Requirements & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Test Identification | Identify the smallest testable unit (e.g., a pure function for dose calculation, a method for column clearance modeling) [39]. | A uniquely identified unit with defined input parameters and an expected output. |

| 2. Environment Setup | Create an isolated test environment. All external dependencies (database calls, API calls, file I/O) must be replaced with mocks or stubs [38] [39]. | A testing framework (e.g., pytest, JUnit) and mocking library (e.g., unittest.mock). Verification that no real external systems are called. |

| 3. Input Definition | Define test input data, including standard use cases, boundary values, and invalid inputs designed to trigger error conditions [42]. | Documented input sets covering valid and invalid ranges. Boundary values must include minimum, maximum, and just beyond these limits. |

| 4. Test Execution | Execute the unit with the predefined inputs. | The test harness runs the unit and captures the output. |