Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Directions for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern ab initio quantum chemistry, a computational approach that solves the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles without empirical parameters.

Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Directions for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern ab initio quantum chemistry, a computational approach that solves the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles without empirical parameters. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational theories of electronic structure, including Hartree-Fock, post-Hartree-Fock methods, and Density Functional Theory. The scope extends to practical applications in drug design, materials science, and catalysis, while also addressing computational challenges, optimization strategies, and the critical validation of results against experimental data. Finally, it explores emerging trends such as the integration of machine learning and quantum computing, highlighting their potential to revolutionize computational modeling in biomedical research.

From First Principles: The Quantum Mechanical Foundations of Ab Initio Chemistry

Ab initio quantum chemistry methods represent a class of computational techniques designed to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles, using only physical constants and the positions and number of electrons in the system as input [1]. This approach contrasts with computational methods that rely on empirical parameters or approximations. The solution to the electronic Schrödinger equation within the Born–Oppenheimer approximation provides the foundation for predicting molecular structures, energies, electron densities, and other chemical properties with high accuracy [1]. The significance of these methods is underscored by the awarding of the 1998 Nobel Prize to John Pople and Walter Kohn for their pioneering developments [1].

The central challenge in ab initio quantum chemistry is the many-electron problem. The electronic Schrödinger equation cannot be solved exactly for systems with more than one electron due to the complex electron-electron repulsion terms. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of ab initio quantum chemistry methods, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for understanding and applying these powerful computational tools in scientific and drug discovery research.

Theoretical Foundation

The Electronic Schrödinger Equation

The non-relativistic electronic Schrödinger equation, within the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, forms the cornerstone of ab initio quantum chemistry methods [1]. In this approximation, the nuclei are treated as fixed due to their significantly larger mass compared to electrons, leading to a Hamiltonian that depends solely on electronic coordinates:

ĤelΨel = EelΨel

Where Ĥel is the electronic Hamiltonian, Ψel is the many-electron wavefunction, and Eel is the electronic energy. The complete many-electron wavefunction is a function of the spatial and spin coordinates of all N electrons. The electronic Hamiltonian consists of several operator components: the kinetic energy operator for all electrons, the Coulomb attraction operator between electrons and nuclei, and the Coulomb repulsion operator between electrons.

The exact many-electron wavefunction is computationally intractable for all but the simplest systems. Ab initio methods address this challenge through a systematic approximation scheme: the many-electron wavefunction is expressed as a linear combination of many simpler electron functions, with the dominant function being the Hartree-Fock wavefunction. These simpler functions are then approximated using one-electron functions (molecular orbitals), which are subsequently expanded as a linear combination of a finite set of basis functions [1]. This approach can theoretically converge to the exact solution when the basis set approaches completeness and all possible electron configurations are included, a method known as "Full CI" [1].

The Variational Principle

The variational principle ensures that the energy computed from any approximate wavefunction is always greater than or equal to the exact ground state energy. This principle provides a crucial criterion for optimizing wavefunction parameters: the best approximation is obtained by minimizing the energy with respect to all parameters in the wavefunction. The Hartree-Fock method is a variational approach that produces energies that approach a limiting value called the Hartree-Fock limit as the basis set size increases [1].

Computational Methodology

Hierarchy of Ab Initio Methods

Ab initio electronic structure methods can be categorized into several classes based on their treatment of electron correlation and computational approach. The table below summarizes the main classes of methods, their theoretical description, and key characteristics.

Table 1: Classification of Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method Class | Theoretical Description | Treatment of Electron Correlation | Computational Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Approximates the many-electron wavefunction as a single Slater determinant | Neglects instantaneous electron correlation; includes only average electron-electron repulsion | N⁴ (nominally), ~N³ with integral screening [1] |

| Post-Hartree-Fock Methods | Builds upon the HF reference wavefunction to include electron correlation | Accounts for electron correlation beyond the mean-field approximation | Varies by method (see Table 2) |

| Multi-Reference Methods | Uses multiple determinant reference wavefunctions | Essential for systems with significant static correlation (e.g., bond breaking) | High computational cost, system-dependent |

| Valence Bond (VB) Methods | Uses localized electron-pair bonds as fundamental building blocks | Provides alternative conceptual framework to molecular orbital theory | Generally ab initio, though semi-empirical versions exist [1] |

| Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) | Uses stochastic integration and explicitly correlated wavefunctions | Avoids variational overestimation of HF; treats correlation explicitly | Computationally intensive; accuracy depends on wavefunction guess [1] |

Key Methodologies in Detail

Hartree-Fock Method

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method represents the simplest ab initio electronic structure approach [1]. In this scheme, each electron experiences the average field of all other electrons, neglecting instantaneous electron-electron repulsion. The HF method is variational, meaning the obtained approximate energies are always equal to or greater than the exact energy [1]. The HF equations are self-consistent field (SCF) equations that must be solved iteratively until the solutions become consistent with the potential field they generate.

The primary limitation of the HF method is its neglect of electron correlation, leading to systematic errors in energy calculations. This limitation motivates the development of post-Hartree-Fock methods that incorporate electron correlation effects.

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

Post-Hartree-Fock methods correct for electron-electron repulsion, referred to as electronic correlation [1]. These methods begin with a Hartree-Fock calculation and subsequently add correlation effects. The most prominent post-HF methods include:

Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MPn): This approach treats electron correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. The second-order correction (MP2) provides a good balance between accuracy and computational cost, scaling as N⁴. Higher orders (MP3, MP4) scale less favorably (N⁶, N⁷ respectively) but provide improved accuracy [1].

Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory: This method uses an exponential ansatz for the wavefunction (êᴺ) applied to the HF reference. The CCSD method includes singles and doubles excitations and scales as N⁶. The CCSD(T) method adds a perturbative treatment of triple excitations and is often considered the "gold standard" for single-reference correlation methods, scaling as N⁷ for the non-iterative triple-excitation correction [1].

Configuration Interaction (CI): The CI method constructs the wavefunction as a linear combination of the HF determinant and excited determinants. Full CI, which includes all possible excitations, is exact within the given basis set but is computationally feasible only for very small systems.

For bond breaking processes, the single-determinant HF reference is often inadequate. In such cases, multi-configurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) methods, which use multiple determinant references, provide a more appropriate starting point for correlation methods [1].

Table 2: Computational Scaling of Selected Ab Initio Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Typical Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | N⁴ (nominal), ~N³ (practical) | Initial calculation for most workflows; suitable for large systems | No electron correlation; tends to overestimate bond lengths |

| MP2 | N⁵ | Moderate-sized systems; initial geometry optimization | Accounts for ~80-90% of correlation energy; good for non-covalent interactions |

| MP3 | N⁶ | Smaller systems; refinement of MP2 results | Improved accuracy over MP2 but more expensive |

| MP4 | N⁷ | Small systems requiring high accuracy | Includes singles, doubles, triples, and quadruples excitations |

| CCSD | N⁶ | High-accuracy calculations for small to medium systems | Includes all single and double excitations |

| CCSD(T) | N⁷ (due to (T) part) | Benchmark-quality calculations | "Gold standard" for single-reference systems; high accuracy |

Density Functional Theory (DFT)

Although not strictly ab initio in the wavefunction-based sense, density functional theory (DFT) has become enormously popular in computational chemistry due to its favorable accuracy-to-cost ratio [2]. DFT begins with the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, which states that all ground-state properties are functionals of the electronic density [2]:

ρ(r) = Σgᵢ|ψᵢ(r)|²

In the Kohn-Sham (KS) formulation of DFT, the energy functional contains four terms: (1) the external potential (typically electron-nuclei interaction), (2) the kinetic energy of a noninteracting reference system, (3) the electron-electron Coulombic energy, and (4) the exchange-correlation (XC) energy, which contains all the many-body effects [2]. The accuracy of DFT depends critically on the approximation used for the unknown XC functional.

Basis Sets

The one-electron molecular orbitals are expanded as linear combinations of basis functions. The choice of basis set significantly impacts the accuracy and computational cost of ab initio calculations. Common basis set types include:

- Slater-type orbitals (STOs): Exponential decay similar to atomic orbitals but computationally challenging for integral evaluation.

- Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs): Products of Gaussian functions; computationally efficient due to the Gaussian product theorem.

- Plane waves: Particularly useful for periodic systems in solid-state physics [2].

- Real-space grids: Emerging approach for large-scale calculations [2].

Basis sets are characterized by their size and flexibility, ranging from minimal basis sets with one function per atomic orbital to correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVXZ) designed to systematically approach the complete basis set limit.

Advanced Computational Considerations

Linear Scaling Approaches

The computational expense of traditional ab initio methods can be alleviated through simplification schemes [1]:

Density Fitting (DF): Reduces the four-index integrals used to describe electron pair interactions to simpler two- or three-index integrals by treating charge densities in a simplified way. Methods using this scheme are denoted by the prefix "df-", such as df-MP2 [1].

Local Approximation: Molecular orbitals are first localized by a unitary rotation, after which interactions of distant pairs of localized orbitals are neglected in correlation calculations. This sharply reduces scaling with molecular size, addressing a major challenge in treating biologically-sized molecules [1]. Methods employing this scheme are denoted by the prefix "L", such as LMP2 [1].

Both schemes can be combined, as demonstrated in df-LMP2 and df-LCCSD(T0) methods, with df-LMP2 calculations being faster than df-Hartree-Fock calculations [1].

Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD)

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) bridges molecular dynamics with quantum mechanics by simulating systems using Newtonian mechanics while computing forces from quantum-mechanical principles [2]. In AIMD, finite-temperature dynamical trajectories are generated using forces obtained directly from electronic structure calculations performed "on the fly" [2].

The fundamental equation of motion in AIMD is:

Mᵢ∂²Rᵢ/∂t² = -∇ᵢ[ε₀(R) + Vₙₙ(R)], (i=1,...,Nₙ)

where Mᵢ and Rᵢ refer to nuclear masses and coordinates, ε₀(R) is the ground-state energy at nuclear configuration R, and Vₙₙ(R) is the nuclear-nuclear repulsion [2].

AIMD is particularly valuable for studying chemical reactions, enzymatic processes, and systems where bond formation and breaking occur [2]. Popular implementations include Car-Parrinello molecular dynamics (CPMD) and path-integral molecular dynamics [2]. The main limitation of AIMD is the computational expense, which typically restricts applications to small systems (tens of atoms) and short timescales (10⁻¹¹ seconds) [2].

The Quantum Nearsightedness Principle and Linear-Scaling Algorithms

The quantum nearsightedness principle (QNP) enables the development of linear-scaling O(N) methods, where computational cost grows only linearly with system size by exploiting the locality of electronic interactions [2]. This principle states that local electronic properties depend significantly only on the immediate environment of each point in space. Various real-space basis sets, including finite differences, B-splines, spherical waves, and wavelets, have been developed to leverage the QNP [2].

The embedded divide-and-conquer (EDC) scheme is one implementation of this principle, where the system is partitioned into local areas (groups of atoms or single atoms), and local density is computed directly from a density functional without invoking Kohn-Sham orbitals [2]. This approach, combined with hierarchical grids and parallel computing, enables the application of AIMD simulations to increasingly large systems, with benchmark tests having included thousands of atoms [2].

Applications and Case Studies

Molecular Structure Prediction

Ab initio methods excel at predicting molecular structures that are challenging to determine experimentally. A representative example is the investigation of disilyne (Si₂H₂) to determine whether its bonding situation resembles that of acetylene (C₂H₂) [1]. Early post-Hartree-Fock studies, particularly configuration interaction (CI) and coupled cluster (CC) calculations, revealed that linear Si₂H₂ is a transition structure between two equivalent trans-bent structures, with the ground state predicted to be a four-membered ring bent in a "butterfly" structure with hydrogen atoms bridged between silicon atoms [1].

Subsequent investigations predicted additional isomers, including a vinylidene-like structure (Si=SiH₂) and a planar structure with one bridging hydrogen atom and one terminal hydrogen atom cis to the bridging atom [1]. The latter isomer required post-Hartree-Fock methods to obtain a local minimum, as it does not exist on the Hartree-Fock energy hypersurface [1]. These theoretical predictions were later confirmed experimentally through matrix isolation spectroscopy, demonstrating the predictive power of ab initio methods [1].

Applications in Polymer Science and Biology

Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations have been successfully applied to diverse problems in polymer physics and chemistry [2]:

Polyethylene systems: Prediction of Young's modulus for crystalline material, strain energy storage, chain rupture under tensile load, spontaneous appearance of "trans-gauche" defects near melting temperature, and influence of knots on polymer strength [2].

Conducting polymers: Vibration and soliton dynamics in neutral and charged polyacetylene chains, electronic and structural properties of polyanilines, and charge localization in doped polypyrrole [2].

Biological systems: AIMD simulations are increasingly applied to biomolecular systems, including enzymatic reactions using model systems based on active-site structures [2]. These simulations provide atomic-level insights into reaction mechanisms that are difficult to obtain experimentally.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ab Initio Calculations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | Gaussian, GAMESS, NWChem, ORCA, CFOUR, Molpro, Q-Chem | Implements various ab initio methods and algorithms | Varying capabilities for different method classes; license requirements |

| Basis Set Libraries | Basis Set Exchange, EMSL Basis Set Library | Provides standardized basis sets for all elements | Completeness, optimization for specific methods or properties |

| Molecular Visualization | GaussView, Avogadro, ChemCraft, Jmol | Model building, input preparation, and results analysis | Integration with computational codes; visualization capabilities |

| AIMD Packages | CP2K, CPMD, Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP | Performs ab initio molecular dynamics simulations | Plane wave vs. localized basis sets; scalability to large systems |

| Analysis Tools | Multiwfn, VMD, Jmol | Processes computational outputs for specific properties | Specialized analysis (bond orders, spectra, charge distribution) |

| High-Performance Computing | Local clusters, national supercomputing centers | Provides computational resources for demanding calculations | Parallel efficiency, storage capacity, job scheduling systems |

Ab initio quantum chemistry methods provide a powerful framework for solving the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles. These methods form a hierarchical structure, from the basic Hartree-Fock approach to sophisticated correlated methods like coupled cluster theory, each with characteristic trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost. The ongoing development of linear-scaling algorithms, density fitting schemes, and local correlation methods continues to expand the applicability of ab initio methods to larger and more complex systems.

The integration of ab initio quantum chemistry with molecular dynamics in AIMD approaches enables the study of dynamic processes with quantum mechanical accuracy, opening new avenues for investigating chemical reactions, materials properties, and biological systems. As computational power increases and algorithms become more efficient, ab initio quantum chemistry methods will continue to provide invaluable insights into molecular structure and behavior, playing an increasingly important role in scientific research and drug development.

In computational physics and chemistry, the Hartree–Fock (HF) method serves as a fundamental approximation technique for determining the wave function and energy of a quantum many-body system in a stationary state [3]. As a cornerstone of ab initio (first-principles) quantum chemistry, it provides the starting point for most more accurate methods that describe many-electron systems. The method's core assumption is that the complex many-electron wave function can be represented by a single Slater determinant (for fermions) or permanent (for bosons), effectively modeling electron interactions through a mean-field approach [3]. Despite its age—dating back to the end of the 1920s—the Hartree-Fock method remains deeply embedded in modern computational chemistry workflows, particularly in pharmaceutical research where it offers a balance between computational cost and reliability for initial electronic structure characterization.

Theoretical Foundation of the Hartree-Fock Method

Historical Development and Theoretical Evolution

The Hartree-Fock method's development traces back to foundational work in the late 1920s and early 1930s [3]. In 1927, Douglas Hartree introduced his "self-consistent field" (SCF) method to calculate approximate wave functions and energies for atoms and ions, though his initial approach (the Hartree method) treated electrons without proper antisymmetry [3]. The critical theoretical advancement came in 1930 when Slater and Fock independently recognized that the Hartree method violated the Pauli exclusion principle's requirement for antisymmetric wave functions [3]. This insight led to reformulating the method using Slater determinants, which automatically enforce the antisymmetric property required for fermions. By 1935, Hartree had refined the approach into a more computationally practical form, creating what we now recognize as the standard Hartree-Fock method [3].

Core Theoretical Principles

The Hartree-Fock method operates on several key theoretical approximations:

- The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is inherently assumed, separating nuclear and electronic motions [3].

- Relativistic effects are typically completely neglected [3].

- The wave function is approximated by a single Slater determinant of N spin-orbitals [3].

- A mean-field approximation replaces explicit electron-electron interactions with an average field [3].

- The variational solution employs a finite basis set to expand the molecular orbitals [3].

The method applies the variational principle, which states that any trial wave function will have an energy expectation value greater than or equal to the true ground-state energy [3]. This makes the Hartree-Fock energy an upper bound to the true ground-state energy, with the best possible solution referred to as the "Hartree-Fock limit"—achieved as the basis set approaches completeness [3].

The central equation in Hartree-Fock theory is the Fock equation, which defines an effective one-electron Hamiltonian operator (the Fock operator) that consists of kinetic energy operators, internuclear repulsion energy, nuclear-electronic attraction terms, and electron-electron repulsion terms described in a mean-field manner [3]. The nonlinear nature of these equations necessitates an iterative solution process, giving rise to the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure where the Fock operator depends on its own eigenfunctions [3].

Computational Implementation and Methodology

The Hartree-Fock Algorithm

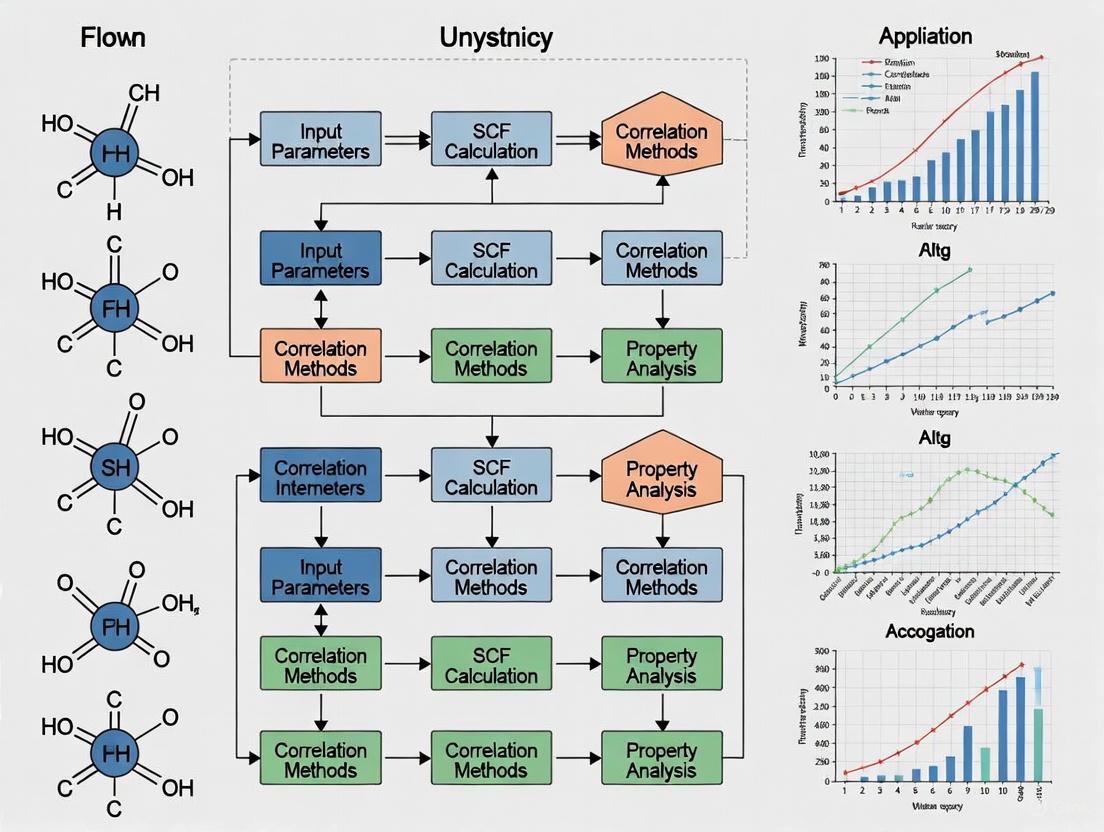

The Hartree-Fock algorithm implements an iterative self-consistent field approach to solve the quantum mechanical equations numerically. The workflow begins with an initial guess for the molecular orbitals, typically constructed as a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO), and proceeds through a series of steps that are repeated until convergence criteria are satisfied.

The following diagram illustrates the iterative SCF procedure:

Key Computational Approximations

The Hartree-Fock method implements several critical approximations to make the many-electron problem computationally tractable:

- Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: The method assumes fixed nuclear positions, separating nuclear and electronic motions [3].

- Non-Relativistic Treatment: The momentum operator is purely non-relativistic, neglecting relativistic effects that become important for heavy elements [3].

- Finite Basis Set Expansion: The molecular orbitals are expanded as linear combinations of a finite number of basis functions, typically chosen to be orthogonal [3].

- Single Determinant Wavefunction: The complex many-electron wavefunction is approximated by a single Slater determinant [3].

- Mean-Field Electron Correlation: Electron-electron repulsion is treated in an average manner, neglecting instantaneous electron correlations [3].

Exploiting Molecular Symmetry

Modern computational chemistry programs recognize and exploit molecular symmetry to significantly accelerate Hartree-Fock calculations [4]. For symmetric molecules, the number of unique integrals that must be evaluated is substantially reduced compared to asymmetric molecules [4]. For example, calculations on neopentane (with Td point group symmetry) complete faster and require less computational resources than equivalent calculations on artificially distorted, asymmetric structures (with C1 point group) [4]. Properly symmetrized input structures are therefore essential for computational efficiency, and most molecular editors provide tools for geometry symmetrization [4].

Table: Computational Efficiency Gains Through Symmetry Exploitation in Neopentane Calculations

| Point Group | Calculation Time | Final Energy (Hartree) | Unique Integrals |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 (Asymmetric) | Longer | Higher (less optimal) | More |

| Td (Symmetric) | Shorter | Lower (more optimal) | Fewer |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table: Essential Software Tools for Hartree-Fock Calculations in Research

| Software Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Jaguar [4] | Ab initio electronic structure program | Single point energy evaluations, geometry optimizations, transition state localization |

| Maestro [4] | Graphical user interface | Molecular building, geometry symmetrization, visualization of results |

| Gaussian [4] | Computational chemistry program | Energy calculations, property predictions, frequency analysis |

| MOLDEN [4] | Molecular visualization program | Building symmetric molecules from fragments, visualization of molecular orbitals |

| PC GAMESS [4] | Quantum chemistry package | Electronic structure calculations with excellent computational speed |

Limitations of the Hartree-Fock Method

Theoretical Limitations and Electron Correlation Problem

Despite its foundational importance, the Hartree-Fock method possesses significant limitations that affect its predictive accuracy:

Electron Correlation Neglect: The most significant limitation is the method's treatment of electron-electron interactions. While Hartree-Fock fully accounts for Fermi correlation (electron exchange through the antisymmetric wavefunction), it completely neglects Coulomb correlation—the correlated motion of electrons due to their mutual repulsion [3]. This correlation error typically accounts for only ~0.3-1% of the total energy but can dominate in processes involving bond breaking, dispersion interactions, and systems with near-degenerate states.

Static Correlation Failure: The single-determinant approximation fails completely for systems with significant static (non-dynamic) correlation, where multiple electronic configurations contribute substantially to the ground state [5]. Examples include transition metal complexes, bond-breaking processes, molecules with near-degenerate electronic states, and magnetic systems [5].

London Dispersion Forces: Hartree-Fock cannot capture London dispersion forces, which are entirely correlation effects arising from instantaneous multipole interactions [3]. This makes the method unsuitable for studying van der Waals complexes, π-π stacking in drug-receptor interactions, and other dispersion-bound systems.

Quantitative Assessment of Limitations

Table: Quantitative Limitations of the Hartree-Fock Method

| Limitation Category | Specific Deficiency | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Correlation | Neglect of Coulomb correlation | ~0.3-1% total energy error, but dominates binding energies |

| Bond Dissociation | Incorrect description of bond breaking | Yields unrealistic potential energy surfaces |

| Dispersion Interactions | Inability to describe London dispersion | Complete failure for van der Waals complexes |

| Transition Metals | Poor treatment of near-degenerate states | Inaccurate electronic structures for d- and f-block elements |

| Band Gaps | Underestimation of semiconductor band gaps | Fundamental gap error due to lack of derivative discontinuity |

Modern Advances and Extensions

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods

To address the limitations of the basic Hartree-Fock approach, numerous post-Hartree-Fock methods have been developed:

Multiconfigurational Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT): This hybrid approach combines multiconfigurational wavefunction theory with density functional theory to handle both weakly and strongly correlated systems [5]. MC-PDFT calculates total energy by splitting it into classical energy (from the multiconfigurational wavefunction) and nonclassical energy (approximated using a density functional) [5].

Recent MC23 Functional: A significant advancement in MC-PDFT is the MC23 functional, which incorporates kinetic energy density to enable more accurate description of electron correlation [5]. This functional has demonstrated improved performance for spin splitting, bond energies, and multiconfigurational systems compared to previous MC-PDFT and Kohn-Sham DFT functionals [5].

Integration with Emerging Computational Technologies

Contemporary research focuses on integrating Hartree-Fock theory with cutting-edge computational approaches:

Quantum Computing: Researchers are working to integrate quantum computing with electron propagator methods to address larger and more complex molecules [6].

Machine Learning Enhancement: Machine learning techniques are being combined with bootstrap embedding—a technique that simplifies quantum chemistry calculations by dividing large molecules into smaller, overlapping fragments [6].

Parameter-Free Methods: Recent developments include parameter-free electron propagation methods that simulate how electrons bind to or detach from molecules without empirical parameter tuning, increasing accuracy while reducing computational power requirements [6].

The following diagram illustrates the methodological landscape showing Hartree-Fock's relationship with other quantum chemical methods:

The Hartree-Fock method remains a cornerstone of computational quantum chemistry nearly a century after its initial development. Its enduring value lies in providing a qualitatively correct description of electronic structure at relatively low computational cost, serving as the reference wavefunction for more sophisticated correlation methods. While its limitations—particularly the neglect of electron correlation—restrict its quantitative accuracy for many chemical applications, ongoing methodological developments continue to extend its utility. The integration of Hartree-Fock theory with emerging computational paradigms like quantum computing, machine learning, and advanced density functional theories ensures this foundational approach will continue to play a vital role in ab initio methodology for the foreseeable future, particularly in pharmaceutical research where understanding electronic behavior is essential for drug design and development.

Ab initio quantum chemistry, meaning "from first principles," aims to predict the properties of atoms and molecules by solving the Schrödinger equation using the fundamental laws of quantum mechanics, without relying on empirical data. The core challenge lies in solving the electronic Schrödinger equation for many-body systems, a task that is analytically intractable for all but the simplest atoms. The accuracy of these solutions hinges on three interdependent pillars: the choice of basis sets, the form of the wavefunction, and the treatment of electron correlation. The convergence of improved algorithms for solving and analyzing electronic structure, modern machine learning methods, and comprehensive benchmark datasets is poised to realize the full potential of quantum mechanics in driving future applications, notably in structure-based drug discovery [7].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core concepts, framing them within the context of modern computational methodology and its application to cutting-edge research, including drug design and materials science.

Basis Sets

Definition and Role in Electronic Structure Calculations

In computational chemistry, a basis set is a set of mathematical functions, typically centered on atomic nuclei, used to construct the molecular orbitals of a system. Since the exact forms of molecular orbitals are unknown, they are expanded as linear combinations of these basis functions (the LCAO approach). The choice of basis set directly controls the flexibility of the orbitals and, consequently, the accuracy of the calculation. The primary types of functions used are:

- Slater-type Orbitals (STOs): Exponential decay, physically accurate but computationally expensive.

- Gaussian-type Orbitals (GTOs): Gaussian decay, less physically accurate but computationally efficient; multiple GTOs are combined to approximate a single STO.

The Conundrum of Diffuse Basis Sets

Diffuse basis functions, characterized by their slow exponential decay and extended spatial range, are essential for an accurate description of molecular properties such as non-covalent interactions (NCIs), electron affinities, and excited states [8]. However, they present a significant computational challenge known as the "conundrum of diffuse basis sets": they are a blessing for accuracy yet a curse for sparsity [8].

The addition of diffuse functions drastically reduces the sparsity of the one-particle density matrix (1-PDM), a property essential for linear-scaling electronic structure algorithms. As illustrated in a study of a 1052-atom DNA fragment, while a minimal STO-3G basis yields a highly sparse 1-PDM, a medium-sized diffuse basis set (def2-TZVPPD) removes nearly all usable sparsity, making sparse matrix techniques ineffective [8]. This occurs because the inverse of the overlap matrix (𝐒⁻¹), which defines the contravariant basis, becomes significantly less local than the original covariant basis, propagating non-locality throughout the system [8].

Table 1: The Impact of Basis Set Augmentation on Accuracy and Computational Cost (RMSD values relative to aug-cc-pV6Z for ωB97X-V functional on the ASCDB benchmark) [8].

| Basis Set | NCI RMSD (M+B) (kJ/mol) | Time for DNA Fragment (s) |

|---|---|---|

| def2-SVP | 31.51 | 151 |

| def2-TZVP | 8.20 | 481 |

| def2-TZVPPD | 2.45 | 1440 |

| aug-cc-pVTZ | 2.50 | 2706 |

| cc-pV6Z | 2.47 | 15265 |

As shown in Table 1, diffuse-augmented basis sets like def2-TZVPPD and aug-cc-pVTZ are necessary to achieve chemically accurate results for NCIs, a feat unattainable by even very large unaugmented basis sets. This underscores their indispensability despite the substantial increase in computational cost.

Basis Set Selection and Recommendations

Selecting an appropriate basis set requires balancing accuracy and computational expense. The following hierarchy provides a general guide:

- Minimal Basis Sets (e.g., STO-3G): Suitable for qualitative studies of very large systems.

- Pople-style Split-Valence (e.g., 6-31G(d)): Good for geometry optimizations and frequency calculations. The inclusion of polarization functions (e.g., "d" on heavy atoms) is crucial.

- Karlsruhe Basis Sets (e.g., def2-SVP, def2-TZVP): Efficient and widely used for general-purpose calculations.

- Dunning's Correlation-Consistent (e.g., cc-pVXZ): Designed for systematic convergence to the basis set limit with electron correlation methods. The "aug-" (augmented) versions include diffuse functions.

- Recommendation: For high-accuracy studies involving NCIs, aug-cc-pVTZ or def2-TZVPPD are often the minimal acceptable choice. For geometry optimizations, cc-pVTZ or def2-TZVP can provide excellent results without diffuse functions [8] [9].

Wavefunctions

The Wavefunction Ansatz and the Hartree-Fock Method

The wavefunction, Ψ, contains all information about a quantum system. The fundamental challenge is to find a computationally tractable yet physically accurate form for Ψ. The simplest ab initio wavefunction is the Hartree-Fock (HF) Slater determinant: [ \Psi{\text{HF}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{N!}} \begin{vmatrix} \phi1(\mathbf{x}1) & \phi2(\mathbf{x}1) & \cdots & \phiN(\mathbf{x}1) \ \phi1(\mathbf{x}2) & \phi2(\mathbf{x}2) & \cdots & \phiN(\mathbf{x}2) \ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \ \phi1(\mathbf{x}N) & \phi2(\mathbf{x}N) & \cdots & \phiN(\mathbf{x}N) \end{vmatrix} ] where the molecular orbitals {ϕi} are optimized to minimize the energy. The HF method approximates each electron as moving in an average field of the others, but it completely neglects electron correlation, leading to energies that can be significantly in error.

Correlated Wavefunction Methods: Beyond Hartree-Fock

To achieve chemical accuracy, the electron correlation error must be corrected. This is done by constructing a wavefunction that is more complex than a single Slater determinant. A powerful and expressive form for a correlated wavefunction is [10]: [ \Psi{\text{corr}}(x,t) = \det \left[ \varphi{\mu}^{BF}(\mathbf{r}_i, x, t) \right] e^{J(x,t)} ] This ansatz incorporates two key features:

- Jastrow Factor (eJ(x,t)): A symmetric, explicit function of electron-electron distances that introduces dynamic correlation by allowing electrons to avoid one another, thereby lowering the energy.

- Backflow Transformation (φμBF(ri, x, t)): A transformation of the orbitals that makes them dependent on the positions of all other electrons. This changes the nodal surface of the wavefunction (which is fixed at the HF level), allowing for the description of static correlation.

This variational approach, especially when enhanced with neural network parameterizations, has demonstrated a superior ability to capture many-body correlations in systems like quenched quantum dots and molecules in intense laser fields, surpassing the capabilities of mean-field methods [10].

Table 2: Hierarchy of Wavefunction-Based Electronic Structure Methods.

| Method | Key Features | Scaling | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Single determinant, mean-field | N³ - N⁴ | Inexpensive, reference for correlated methods | Neglects electron correlation |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation (MP2, MP4) | Adds correlation via perturbation theory | MP2: N⁵, MP4: N⁷ | Size-consistent, good for weak correlation | Non-variational, poor convergence for some systems [9] |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD, CCSD(T)) | Exponential ansatz for correlation | CCSD: N⁶, (T): N⁷ | Gold standard for single-reference systems; size-consistent [9] | High cost for large systems |

| Configuration Interaction (CISD, FCI) | Linear combination of determinants | FCI: N! | FCI is exact within basis set; intuitive | CISD is not size-consistent; FCI is prohibitively expensive [9] |

| Variational Monte Carlo (VMC) with Jastrow/Backflow | Stochastic evaluation of integrals; expressive ansatz | Depends on ansatz | Can handle continuous space, high accuracy [10] | Stochastic error, optimization can be challenging |

Electron Correlation

The Concept and Types of Electron Correlation

Electron correlation is the energy difference between the exact solution of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation and the Hartree-Fock solution. It arises from the HF method's failure to account for the instantaneous Coulomb repulsion between electrons. There are two main types:

- Dynamic Correlation: The tendency of electrons to avoid one another due to their Coulomb repulsion. This is a short-range effect and is present in all systems.

- Static (or Non-Dynamic) Correlation: Occurs in systems with degenerate or near-degenerate electronic configurations (e.g., bond breaking, diradicals). A single Slater determinant is a poor starting point, and multiple determinants are required for a qualitatively correct description.

Methodologies for Capturing Electron Correlation

A variety of post-Hartree-Fock methods have been developed to recover correlation energy.

Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory

This is an economical way to partially correct for the lack of dynamic electron correlation [9]. The second-order correction (MP2) is the most popular, offering a good balance of cost and accuracy. It is particularly valuable for describing van der Waals forces. However, the perturbation series can diverge for systems with a poor HF reference, and the method is non-variational [9]. Local MP2 approximations can reduce the formal N⁵ scaling to nearly linear for large molecules [9].

Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory

Coupled cluster theory provides a more robust and accurate description of electron correlation than perturbation theory [9]. The CCSD(T) method—including singles, doubles, and a perturbative estimate of triples—is often called the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for its ability to deliver high accuracy for single-reference systems. Its primary disadvantage is the high computational cost, which limits application to smaller molecules, though local approximations are also being developed for CC methods.

Configuration Interaction (CI)

The Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) method expands the wavefunction as a linear combination of all possible Slater determinants within a given basis set, providing the exact solution for that basis. It is, however, prohibitively expensive for all but the smallest systems. Truncated CI methods, like CISD (including single and double excitations), are not size-consistent, meaning their error increases with system size, limiting their utility [9].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Workflows

This section provides detailed methodologies for key computational experiments that illustrate the application of the concepts discussed above.

Protocol 1: High-Accuracy Structure Determination of Carbon Monoxide

Objective: To determine the equilibrium bond length and dipole moment of carbon monoxide (CO) using high-level electron correlation methods and systematically converge towards the basis set limit [9].

Computational Details:

- Software: Gaussian, Dalton, or other ab initio packages.

- Methods: HF, MP2, CCSD, CCSD(T).

- Basis Sets: cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ (Dunning's correlation-consistent series).

- Coordinate Input: Molecular geometry can be specified via Z-matrix or XYZ format.

- Key Keywords: For property calculation, ensure the

Densitykeyword is included to compute the dipole moment from the correlated density.

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Construct an input file for CO. Specify the method, basis set, and requested properties (optimization and dipole moment).

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a series of geometry optimizations, varying the level of theory and basis set.

- Data Extraction: From the output of each calculation, extract the optimized C–O bond length (in Å) and the dipole moment (in Debye).

- Analysis: Plot the bond length versus the level of theory for a fixed basis set (e.g., cc-pVTZ) to show the effect of electron correlation. Then, plot the bond length versus basis set for the CCSD(T) method to demonstrate basis set convergence. Compare final results with experimental values (R_e = 1.1283 Å, μ = -0.112 D).

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Diffuse Functions on Non-Covalent Interactions

Objective: To quantify the critical role of diffuse basis functions in accurately calculating the binding energies of non-covalent complexes (e.g., hydrogen bonds, π-stacking) [8].

Computational Details:

- Software: Any ab initio code with a range-separated hybrid functional (e.g., ωB97X-V).

- Systems: Select a benchmark set like the ASCDB, which includes various non-covalent interaction types.

- Basis Sets: def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, def2-SVPD, def2-TZVPPD, aug-cc-pVDZ, aug-cc-pVTZ.

Procedure:

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: For each complex and its monomers in the benchmark set, perform a single-point energy calculation using the ωB97X-V functional and the series of basis sets listed.

- Binding Energy Calculation: Compute the interaction energy for each complex as ΔE = E(complex) - ΣE(monomers). (Note: For production work, counterpoise correction should be applied to correct for basis set superposition error).

- Error Analysis: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the binding energies for each basis set relative to the reference (e.g., aug-cc-pV6Z) across the entire benchmark and for the NCI subset.

- Sparsity Analysis: For a large system (e.g., a DNA fragment), compute the 1-PDM with different basis sets and analyze the number of elements below a chosen threshold to illustrate the sparsity "curse."

Workflow Diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for Ab Initio Electronic Structure Calculations.

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dunning's cc-pVXZ | Basis Set | Systematic convergence to the basis set limit for correlated methods. | High-accuracy thermochemistry and spectroscopy [9]. |

| Karlsruhe def2-SVP/TZVP | Basis Set | Efficient, general-purpose basis sets for geometry optimizations. | Initial scanning of molecular conformers and reaction pathways. |

| Diffuse/Augmented Functions | Basis Set | Accurate description of electron density tails and non-covalent interactions. | Modeling protein-ligand binding, anion stability, and excited states [8]. |

| Jastrow Factor | Wavefunction Ansatz | Explicitly introduces dynamic electron correlation by modeling electron-electron distances. | Improving variational energy in QMC and neural wavefunction calculations [10]. |

| Backflow Transformation | Wavefunction Ansatz | Introduces many-body dependence into orbitals, improving nodal surface. | Accurately describing strongly correlated systems and bond dissociation [10]. |

| Local MP2/CC Algorithms | Computational Method | Reduces formal scaling of correlated methods by exploiting sparsity of interactions. | Applying correlated methods to large molecules like pharmaceuticals (e.g., Taxol) [9]. |

| CABS Singles Correction | Correction Method | Amends basis set incompleteness error, particularly with compact basis sets. | Mitigating the "curse of sparsity" from diffuse functions while maintaining accuracy [8]. |

| Quantum Computing Simulators (e.g., BlueQubit) | Hardware/Software Platform | Emulates quantum algorithms for molecular simulation on classical hardware. | Exploring quantum approaches to electronic structure in the NISQ era [11] [12]. |

Historical Context and the Nobel Prize-Winning Work of Pople and Kohn

The 1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded jointly to Walter Kohn and John A. Pople, marked a monumental recognition of a fundamental shift in how chemical problems are solved. Kohn was honored for his development of the density-functional theory (DFT), while Pople was recognized for his development of computational methods in quantum chemistry [13] [14]. Their pioneering work provided chemists with powerful tools to theoretically study the properties of molecules and the chemical processes in which they are involved, effectively creating a new branch of chemistry where calculation and experimentation work in tandem [14]. This revolution was rooted in the application of quantum mechanics to chemical problems, a challenge that had been notoriously difficult since the physicist Dirac noted in 1929 that the underlying laws were fully known, but the resulting equations were simply too complex to be solved [14]. The advent of computers and the methodologies developed by Kohn and Pople finally provided a practicable path forward, enabling researchers to probe the electronic structure of matter with unprecedented accuracy and detail.

Historical and Scientific Context

The Quantum Mechanical Challenge in Chemistry

The growth of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century opened new possibilities for understanding chemical bonds and molecular behavior. However, for decades, applications in chemistry remained limited because the complicated mathematical equations of quantum mechanics could not be practically handled for complex molecular systems [14]. The central problem revolved around describing the motion and interaction of every single electron in a system, a task of prohibitive computational complexity for all but the simplest molecules.

The Computational Catalyst

The situation began to change significantly in the 1960s with the advent of computers, which could be employed to solve the intricate equations of quantum chemistry [14]. This technological advancement provided the necessary catalyst for the field to emerge as a distinct and valuable branch of chemistry. As noted by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the consequences of this development have been revolutionary, transforming the entire discipline of chemistry by the close of the 1990s [14]. Walter Kohn and John Pople emerged as the foremost figures in this transformative process, each attacking the core problem from a different, complementary angle.

Walter Kohn and Density-Functional Theory

Foundational Principles of DFT

Walter Kohn's transformative contribution was the development of density-functional theory, which offered a computationally simpler approach to the quantum mechanical description of electronic structure. Kohn demonstrated that it was not necessary to consider the motion of each individual electron. Instead, it sufficed to know the average number of electrons located at any one point in space—the electron density [14] [15]. This profound insight dramatically reduced the computational complexity of the problem.

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests on two fundamental theorems, known as the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, developed with Pierre Hohenberg in 1964 [15] [16]:

- The ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density.

- A universal functional for the energy exists in terms of the electron density, and the correct ground-state density minimizes this functional.

The Kohn-Sham Equations

In 1965, Kohn, in collaboration with Lu Jeu Sham, provided a practical methodology for applying DFT through the Kohn-Sham equations [15]. These equations map the complex many-body problem of interacting electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that generate the same density. This approach decomposes the total energy into tractable components:

[ E[\rho] = Ts[\rho] + E{ext}[\rho] + EH[\rho] + E{xc}[\rho] ]

Where:

- ( T_s[\rho] ) is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons

- ( E_{ext}[\rho] ) is the external potential energy

- ( E_H[\rho] ) is the classical electron-electron repulsion (Hartree energy)

- ( E_{xc}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation energy, which encapsulates all quantum mechanical many-body effects

Table: Key Components of the Kohn-Sham DFT Energy Functional

| Energy Component | Physical Significance | Treatment in DFT |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Energy (Tₛ) | Energy from motion of electrons | Calculated exactly for non-interacting system |

| External Potential (Eₑₓₜ) | Electron-nucleus attraction | Calculated exactly |

| Hartree Energy (E_H) | Classical electron-electron repulsion | Calculated exactly |

| Exchange-Correlation (Eₓ₈) | Quantum mechanical many-body effects | Approximated; determines accuracy |

The simplicity of the DFT method makes it possible to study very large molecules, including enzymatic reactions, and it has become one of the most widely used approaches in quantum chemistry today [14]. It took more than three decades for a large community of researchers to render these calculations fully practicable, but the method is now indispensable across materials science, condensed-phase physics, and the chemical physics of atoms and molecules [15].

John Pople and Computational Quantum Chemistry

Development of Computational Methodologies

John Pople's contribution to the field was the systematic development of a comprehensive suite of computational methods for theoretical studies of molecules, their properties, and their interactions in chemical reactions [14] [17]. His approaches were firmly rooted in the fundamental laws of quantum mechanics. Pople recognized early that for theoretical methods to gain significance within chemistry, researchers needed to know the accuracy of the results in any given case, and the methods had to be accessible and not overly demanding of computational resources [14].

Pople's scientific journey in computational chemistry progressed through several important stages:

- Semi-empirical methods: Development of the Pariser-Parr-Pople method for pi-electron systems, followed by Complete Neglect of Differential Overlap (CNDO) and Intermediate Neglect of Differential Overlap (INDO) for three-dimensional molecules [17].

- Ab initio electronic structure theory: Pioneered the use of basis sets of Slater type orbitals or Gaussian orbitals to model wavefunctions, leading to increasingly accurate calculations [17] [1].

- Composite methods: Developed Gaussian-1 (G1) and Gaussian-2 (G2) methods for high-accuracy energy calculations [17].

The GAUSSIAN Program and Model Chemistry

Pople's most impactful practical contribution was the creation of the GAUSSIAN computer program, first published in 1970 as Gaussian-70 [14] [17]. This program was designed to make computational techniques easily accessible to researchers worldwide. A user would input details of a molecule or chemical reaction, and the program would output a description of the properties or reaction pathway [14].

A key conceptual advance introduced by Pople was the notion of a "model chemistry"—a well-defined theoretical procedure capable of calculating molecular properties with predictable accuracy across a range of chemical systems [17] [18]. This framework allowed for the systematic improvement and validation of computational methods. In the 1990s, Pople successfully integrated Kohn's density-functional theory into this model chemistry framework, opening new possibilities for analyzing increasingly complex molecules [14].

Table: Evolution of Key Computational Methods in Quantum Chemistry

| Method Class | Theoretical Basis | Scaling with System Size | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Approximates electron interaction via mean field | N⁴ (becomes N³ with optimizations) | Initial molecular structure, orbitals |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density instead of wavefunction | N³ (can be lower with approximations) | Large molecules, solids, materials design |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation (MP2, MP4) | Adds electron correlation corrections via perturbation theory | MP2: N⁵, MP4: N⁷ | Non-covalent interactions, thermochemistry |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD, CCSD(T)) | High-accuracy treatment of electron correlation | CCSD: N⁶, CCSD(T): N⁷ | Benchmark calculations, spectroscopic accuracy |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Fundamental Theoretical Framework

The work of both Kohn and Pople is grounded in solving the electronic Schrödinger equation within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates the motion of electrons and nuclei [1]. The fundamental challenge lies in the electron-electron interaction term that makes the equation unsolvable exactly for many-electron systems.

Table: Comparison of Fundamental Approaches to the Quantum Chemical Problem

| Feature | Wavefunction Methods (Pople) | Density Functional Theory (Kohn) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Variable | Many-electron wavefunction, Ψ(r₁,r₂,...,r_N) | Electron density, ρ(r) |

| Computational Scaling | Typically N⁵ to N⁷ for correlated methods | Typically N³ to N⁴ |

| System Size Limit | Dozens of atoms | Hundreds to thousands of atoms |

| Treatment of Correlation | Systematic improvement possible (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T)) | Approximated via exchange-correlation functional |

| Key Advantage | Systematic improvability, high accuracy for small systems | Favorable scaling, good accuracy for large systems |

Workflow for Quantum Chemical Calculations

A standard quantum chemical calculation, as enabled by Pople's GAUSSIAN program and Kohn's DFT, follows a systematic protocol:

The specific steps involve:

System Definition: The researcher defines the molecular system by specifying atomic coordinates (from experimental data or preliminary modeling), molecular charge, and spin multiplicity [14].

Basis Set Selection: Choosing an appropriate set of mathematical functions (basis functions) to represent the molecular orbitals. Pople's contributions included developing standardized basis sets (such as the Pople-style basis sets like 6-31G*) that balanced accuracy and computational cost [17] [1].

Theoretical Method Selection: Deciding on the level of theory, which could range from Hartree-Fock to various post-Hartree-Fock methods (MP2, CCSD(T)) or Kohn's DFT with a specific exchange-correlation functional [1] [16].

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Procedure: An iterative process that continues until the energy and electron distribution converge to a consistent solution [14] [1].

Property Calculation: Once convergence is achieved, the program calculates desired molecular properties, including total energy, molecular structure, vibrational frequencies, and electronic properties [14].

Result Analysis: Interpretation of the computational results, often with visualization of molecular orbitals, electron densities, or simulated spectra for comparison with experimental data [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Essential Computational "Reagents" in Quantum Chemistry

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions to represent atomic and molecular orbitals | Pople-style (6-31G*), Dunning's correlation-consistent (cc-pVDZ) |

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | Approximate the quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects in DFT | LDA, GGA (PBE), Hybrid (B3LYP, PBE0) |

| Pseudopotentials | Represent core electrons to reduce computational cost, especially for heavy atoms | Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) |

| Geometry Optimization Algorithms | Find minimum energy structures through iterative updates of nuclear coordinates | Berny algorithm, quasi-Newton methods |

| SCF Convergence Accelerators | Ensure stable convergence to self-consistent solution | Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace (DIIS) |

| Molecular Properties Codes | Calculate derived properties from wavefunction or density | NMR chemical shifts, IR frequencies, excitation energies |

Applications and Impact

Revolutionizing Chemical Research

The methodologies developed by Kohn and Pople have found applications across virtually all branches of chemistry and molecular physics [14]. They provide not only quantitative information on molecules and their interactions but also afford deeper understanding of molecular processes that cannot be obtained from experiments alone [14]. Key application areas include:

Atmospheric Chemistry: Understanding the destruction of ozone molecules by freons (CF₂Cl₂) in the upper atmosphere. Quantum-chemical calculations can describe these reactions in detail, helping to understand environmental threats and guide regulatory policies [14].

Astrochemistry: Determining the composition of interstellar matter by comparing calculated radio emission frequencies with data collected by radio telescopes. This approach is particularly valuable since many interstellar molecules cannot be easily produced in the laboratory for comparative studies [14].

Biochemical Systems: Studying enzymatic reactions and protein-substrate interactions, including applications in pharmaceutical research where computational methods can predict how drug molecules interact with their biological targets [14].

Materials Science: Designing new materials with tailored electronic, optical, or mechanical properties by calculating their electronic structure and predicting their behavior before synthesis [16].

Case Study: The Disilyne (Si₂H₂) Problem

A representative example of how these computational methods have resolved chemical questions is the investigation of disilyne (Si₂H₂) structure. For over 20 years, a series of ab initio studies using post-Hartree-Fock methods addressed whether Si₂H₂ had the same structure as acetylene (C₂H₂) [1]. Computational results revealed that:

- Linear Si₂H₂ is a transition structure between two equivalent trans-bent structures

- The ground state is a four-membered ring with a 'butterfly' structure where hydrogen atoms bridge the two silicon atoms

- A vinylidene-like structure (Si=SiH₂) exists as a higher-energy isomer

- A previously unpredicted planar structure with one bridging and one terminal hydrogen atom was discovered computationally before being confirmed experimentally [1]

This case illustrates the power of computational chemistry to predict new molecular structures and explain chemical bonding in systems that challenge traditional chemical intuition.

Integration and Legacy

Complementary Nature of the Approaches

While Kohn's DFT and Pople's ab initio methods represent different philosophical approaches to the electronic structure problem, they have converged in modern computational chemistry. Pople's GAUSSIAN program eventually incorporated Kohn's density-functional theory, creating a comprehensive computational environment where researchers can select the most appropriate method for their specific problem [14] [17]. The two approaches are now understood as complementary rather than competing:

- DFT excels for larger systems where its favorable scaling (typically N³) makes calculations feasible, and for properties that depend strongly on electron density [14] [15].

- Ab initio wavefunction methods provide higher accuracy for smaller systems and offer systematically improvable results, making them valuable for benchmark calculations and parameter development [1] [16].

Current Status and Future Directions

The legacy of Kohn and Pople's work continues to evolve. Current research focuses on:

- Developing more accurate and efficient exchange-correlation functionals for DFT

- Reducing the computational scaling of correlated wavefunction methods

- Combining quantum mechanical methods with classical approaches (QM/MM) for large biological systems

- Integrating machine learning techniques with traditional quantum chemistry

- Expanding applications to complex materials and catalytic systems

As of 2024, their methodologies remain foundational to computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, with thousands of researchers building upon their work to push the boundaries of what can be calculated and predicted from first principles.

A Practical Guide to Ab Initio Methods and Their Real-World Impact

The predictive power of computational chemistry, biochemistry, and materials science hinges on solving the electronic Schrödinger equation, a task that grows exponentially in complexity with the number of electrons [19]. For decades, scientists have navigated a fundamental trade-off: the balance between the computational cost of a quantum chemical method and its accuracy in predicting experimental outcomes. This whitepaper examines this critical hierarchy, focusing on three pivotal methods: Density Functional Theory (DFT), Second-Order Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2), and the "gold-standard" Coupled Cluster theory with Single, Double, and perturbative Triple excitations (CCSD(T)). While DFT offers a computationally efficient, scalable framework with versatile applications, its accuracy is fundamentally limited by the approximate nature of the unknown exchange-correlation functional [19] [20]. In contrast, CCSD(T) provides high accuracy for a broad range of molecular properties but at a prohibitive computational cost that limits its application to small systems [21] [22]. MP2 occupies a middle ground, offering a more affordable, though less reliable, post-Hartree-Fock treatment of electron correlation [23] [21]. Understanding this landscape is crucial for researchers, particularly in drug development, where inaccuracies of a few kcal/mol can determine the success or failure of a candidate molecule [19].

Theoretical Foundations of KeyAb InitioMethods

Density Functional Theory (DFT): The Workhorse

DFT revolutionized quantum chemistry by recasting the intractable many-electron problem into a manageable problem of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential [20]. The theory is based on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which prove that the ground-state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density, n(r) [20]. The Kohn-Sham equations then provide a practical framework for calculations:

Here, Tₛ[n] is the kinetic energy of the non-interacting system, E_H[n] is the classical Hartree energy, E_ext[n] is the energy from the external potential, and E_XC[n] is the exchange-correlation functional, which encapsulates all non-trivial many-body effects [20]. The central challenge in DFT is the unknown exact form of E_XC[n], leading to a "zoo" of hundreds of approximate functionals [19]. The accuracy of a DFT calculation is almost entirely dictated by the choice of functional, with errors in atomization energies typically 3-30 times larger than the desired chemical accuracy of 1 kcal/mol [19].

Wavefunction-Based Methods: MP2 and CCSD(T)

Wavefunction-based methods approach the many-electron problem differently, by constructing increasingly accurate approximations to the full wavefunction.

- MP2: As the simplest correlated method beyond Hartree-Fock, MP2 is a non-iterative,

O(N⁵)scaling method that provides a good description of dispersion interactions. However, it can be unreliable for systems with significant static correlation [23] [21]. - CCSD(T): This method is often considered the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its excellent accuracy across diverse chemical systems [21] [22]. It uses an exponential wavefunction ansatz,

Ψ_CC = e^(T) Φ₀, whereTis the cluster operator creating single (T₁), double (T₂), and perturbative triple (T₃) excitations from the reference wavefunctionΦ₀. The computational cost scales asO(N⁷), making it prohibitively expensive for large systems [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Electronic Structure Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Scaling | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT | Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, Kohn-Sham equations [20] | O(N³) |

Versatile, efficient for large systems; good for geometries [19] [20] | Unknown exact functional; accuracy depends on choice of functional; poor for dispersion, charge transfer [19] [20] |

| MP2 | Rayleigh-Schrödinger Perturbation Theory [23] | O(N⁵) |

Good for dispersion interactions; more systematic than DFT [23] [21] | Can overbind; unreliable for metals and strongly correlated systems [23] |

| CCSD(T) | Exponential cluster ansatz [22] | O(N⁷) |

High accuracy across diverse chemistry; reliable benchmark method [21] [22] | Prohibitive cost for large systems; complex implementation [21] [22] |

Quantitative Accuracy and Cost Comparison

The choice of method often hinges on a quantitative understanding of its performance for specific properties versus its computational demand.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Resource Requirements

| Method | Typical Accuracy (vs. Experiment) | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Computational Cost (Relative) | Example Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (GGA/Meta-GGA) | 5-15 kcal/mol for atomization energies [19] | 100s - 1000s | 1x (Baseline) | Over-structures liquid water RDF [21] |

| DFT (Hybrid) | 3-10 kcal/mol [19] | 10s - 100s | 10-100x higher than GGA [19] | M06, MN15 MAE ~1.2 kcal/mol for organodichalcogenides [24] |

| MP2 | ~0.5 eV for CEBEs [22] | 10s - 100s | ~100x higher than DFT [21] | DLPNO-MP2 used for training data for water MLPs [21] |

| CCSD(T) | ~0.1-0.2 eV for CEBEs; chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol) for main-group thermochemistry [22] | < 50 (canonical) | ~1000x higher than DFT; 2.4 hrs vs. 1 min for MP2 in a large basis [22] | MAE of 0.123 eV for 94 CEBEs [22] |

A critical illustration of the cost-accuracy trade-off comes from core-electron binding energy (CEBE) calculations [22]. Achieving experimental accuracy requires methods like ΔCCSD(T) in a large basis set, which can take hours for a single calculation. However, a Δ-learning strategy can achieve nearly identical accuracy at a fraction of the cost by combining an inexpensive large-basis ΔMP2 calculation with a small-basis ΔCCSD correction [22].

Advanced Protocols and Hybrid Strategies

Protocol for Δ-Learning in Condensed Phase Simulation

The Δ-learning strategy is a powerful hybrid approach to elevate a cheaper method to gold-standard accuracy [21]. A recent protocol for simulating liquid water with CCSD(T) accuracy exemplifies this:

- Baseline Machine Learning Potential (MLP): Train a neural network potential (

MLP_DFT) on energies and forces from periodic DFT calculations of water. This baseline reliably handles long-range interactions and constant-pressure simulations [21]. - Generate Cluster Training Set: Extract thousands of snapshots of water clusters (e.g., 16-64 molecules) from equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations run with

MLP_DFT[21]. - Compute Δ-Values: For each cluster, compute the energy difference

ΔE = E_CCSD(T) - E_DFTusing local approximations (e.g., DLPNO or LNO) to make the CCSD(T) calculation tractable for the clusters. Note that forces are not required for this step [21]. - Train Δ-MLP: Train a second machine learning potential (

Δ-MLP) to predict theΔEcorrection based on the cluster geometry [21]. - Production Simulation: The final CCSD(T)-level model is the sum:

MLP_CCSD(T) = MLP_DFT + Δ-MLP. This composite model can then be used for extended molecular dynamics simulations under constant pressure, predicting properties like the density maximum of water in agreement with experiment [21].

Protocol for Local Correlation Methods in Molecular Systems

Local correlation approximations, such as Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbitals (DLPNO), are essential for applying wavefunction methods to larger systems [23] [21]. An optimized workflow for local MP2 demonstrates key steps:

- Orbital Localization: Transform the canonical Hartree-Fock orbitals into localized orbitals for both occupied and virtual spaces. This step is crucial for exploiting the nearsightedness of electron correlation [23].

- Domain Construction: For each localized occupied orbital, define a correlation domain of significant virtual orbitals using sparse maps and a numerical threshold (

ε) [23]. - Amplitude Calculation: Solve the MP2 amplitude equations iteratively. Key optimizations include [23]:

- A novel embedding correction for discarded integrals.

- A modified set of occupied orbitals to increase diagonal dominance in the Fock operator.

- On-the-fly selection of matrix multiplication kernels (BLAS-2/BLAS-3) in conjugate gradient iterations.

- Energy Evaluation: Calculate the final LMP2 correlation energy. Recent optimizations have been shown to provide an order-of-magnitude improvement in accuracy for a given computational time compared to other local methods like DLPNO-MP2 [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

In computational chemistry, the "reagents" are the software, algorithms, and data that enable research. The following table details key solutions for achieving high-accuracy results efficiently.

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Electronic Structure Calculations

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Local Correlation Approximations (DLPNO, LNO) | Drastically reduce the computational cost and scaling of MP2 and CCSD(T) by exploiting the local nature of electron correlation [23] [21]. | Enabling CCSD(T) calculations on water clusters of 64 molecules for training MLPs [21]. |

| Δ-Learning / Multi-Level MLPs | A machine-learning strategy to correct a cheap, baseline model (e.g., DFT-MLP) to a high-level of theory (e.g., CCSD(T)) using only energy differences from molecular clusters [21]. | Achieving CCSD(T)-accurate simulation of liquid water's density and structure without explicit periodic CCSD(T) calculations [21]. |

| Embedding Corrections | In local correlation methods, this correction accounts for the effect of integrals that are evaluated but discarded as below a threshold, improving accuracy [23]. | Used in optimized LMP2 to provide an order-of-magnitude improvement in accuracy for non-covalent interaction benchmarks [23]. |

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets (cc-pVXZ) | A systematic hierarchy of basis sets (X=D, T, Q, 5) that allows for controlled convergence to the complete basis set (CBS) limit via extrapolation [21] [22]. | Critical for benchmarking and in the Δ-CEBE method to recover CBS-limit CCSD(T) results from finite-basis calculations [22]. |

| High-Accuracy Wavefunction Benchmark Data | Large, diverse datasets of molecular energies and properties computed with high-level wavefunction methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) to train and validate new models [19] [24]. | Used to train the Skala deep-learned functional and to benchmark DFT functional performance for organodichalcogenides [19] [24]. |

The hierarchy of electronic structure methods, from the affordable but approximate DFT to the accurate but costly CCSD(T), defines the landscape of modern computational chemistry. MP2 occupies a crucial middle ground. The future of the field lies not in the discovery of a single perfect method, but in the intelligent combination of these approaches through advanced algorithms. Δ-learning and local correlation approximations are powerful exemplars of this trend, creating hybrid strategies that deliver high accuracy for manageable computational cost [23] [21] [22]. Furthermore, the integration of deep learning, as demonstrated by the Skala functional, shows promise in breaking long-standing accuracy barriers in DFT by learning the exchange-correlation functional directly from vast, high-quality wavefunction data [19]. As these methodologies mature and become more routine, they will profoundly shift the balance in molecular and materials design from laboratory-driven experimentation to computationally driven prediction, accelerating discovery across pharmaceuticals, catalysis, and materials science [19].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, representing the most widely used quantum mechanical method for electronic structure calculations. This prevalence stems from its unique position at the intersection of computational efficiency and quantum accuracy. The fundamental theorem of DFT, the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, establishes that all properties of a multi-electron system are uniquely determined by its electron density, thereby simplifying the complex many-electron wavefunction problem into a more tractable functional of the density [25]. In practice, this is implemented through the Kohn-Sham equations, which construct a system of non-interacting electrons that reproduces the same density as the true interacting system [25] [5].

The central challenge in applying DFT to scientifically relevant systems lies in balancing the competing demands of accuracy and computational efficiency. While DFT dramatically reduces computational cost compared to wave function-based methods like coupled cluster theory, its accuracy depends critically on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional—the term that encapsulates all quantum mechanical effects not described by the classical electrostatic interactions [25] [5]. For large systems such as biomolecules, complex materials, and catalytic systems, this balance becomes increasingly difficult to maintain. The computational cost of traditional DFT calculations scales approximately as O(N^3), where N represents the number of atoms, making simulations of systems with hundreds of atoms prohibitively expensive for most research settings [26]. This review examines the recent methodological advances that address this fundamental challenge, enabling researchers to achieve high accuracy while maintaining practical computational efficiency for large-scale systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Current Methodological Challenges

The Accuracy Frontier: Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The accuracy of DFT calculations is primarily determined by the choice of exchange-correlation functional, which has evolved through several generations of increasing sophistication. The Local Density Approximation (LDA), the simplest functional, works reasonably well for metallic systems but inadequately describes weak interactions like hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces [25]. The Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) incorporates density gradient corrections, making it suitable for biomolecular systems, while meta-GGA functionals further improve accuracy by including the kinetic energy density [25]. For systems requiring high precision, hybrid functionals like B3LYP and PBE0 incorporate exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory but at significantly increased computational cost [25].