Active Learning for Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide to Accelerating Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the foundations and applications of active learning (AL) in structure-based virtual screening (VS) for drug discovery.

Active Learning for Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide to Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the foundations and applications of active learning (AL) in structure-based virtual screening (VS) for drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles that make AL a powerful tool for navigating ultra-large chemical libraries, reducing computational costs by over an order of magnitude. The scope covers fundamental AL workflows, key methodological choices including surrogate models and acquisition functions, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous validation through benchmark studies and real-world case studies. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide serves as a roadmap for integrating AL into VS campaigns to achieve higher hit rates and accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic compounds.

The 'Why' Behind the Shift: How Active Learning is Revolutionizing Virtual Screening

Addressing the Computational Bottleneck in Ultra-Large Library Screening

The fundamental challenge in modern virtual screening is the astronomical size of drug-like chemical space, which contains trillions of potential compounds, far surpassing the screening capabilities of traditional computational methods [1]. Conventional virtual screening techniques have been limited to evaluating libraries of just millions of compounds, assessing less than 0.1% of available chemical space and leaving valuable potential drugs undiscovered [2]. This limitation represents a critical computational bottleneck that has constrained drug discovery efforts for decades. As the chemical libraries have expanded to billions of compounds, traditional brute-force docking methods that require massive computational resources have become increasingly impractical, creating an urgent need for more intelligent and efficient screening methodologies [2] [3].

The emergence of ultra-large commercial chemical libraries such as Enamine REAL, which contain billions of synthesizable compounds, has further exacerbated this computational challenge [3]. In Schrödinger's experience, traditional virtual screening approaches typically yield hit rates of only 1-2%, meaning that 100 compounds would need to be synthesized and assayed for just 1-2 hits to be identified [3]. This inefficiency wastes substantial wet-lab resources and prolongs drug development timelines. The core of the problem lies in two key factors: the inaccuracy of traditional scoring methods for rank-ordering ligands, and the computational intractability of comprehensively screening ultra-large libraries using conventional docking approaches [3].

Active Learning as a Foundational Solution

Active learning (AL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning strategy to address the computational bottleneck in ultra-large library screening. AL is an iterative feedback process that efficiently identifies valuable data within vast chemical spaces, even with limited labeled data [4]. This characteristic makes it particularly valuable for addressing the ongoing challenges in drug discovery, such as the ever-expanding exploration space and limitations of labeled data [4]. In the context of virtual screening, AL protocols work by selectively prioritizing the most informative compounds for evaluation, thereby reducing the number of computational expensive calculations required to identify high-potency binders.

The application of active learning in drug discovery has gained significant prominence across multiple stages, including compound-target interaction prediction, virtual screening, molecular generation and optimization, and molecular properties prediction [4]. Systematic benchmarking of AL protocols for ligand-binding affinity prediction has demonstrated their effectiveness in identifying top binders from vast molecular libraries [5]. These protocols use metrics describing both the overall predictive power of the model (R², Spearman rank, RMSE) and the accurate identification of top binders (Recall, F1 score) to optimize performance [5].

Key Parameters for Effective Active Learning Implementation

Research has identified several critical parameters that influence the effectiveness of active learning protocols:

- Initial batch size: A larger initial batch size, especially on diverse datasets, increases the recall of both Gaussian Process and Chemprop models, as well as overall correlation metrics [5].

- Subsequent batch sizes: For active learning cycles after the initial batch, smaller batch sizes of 20 or 30 compounds prove more desirable for efficient optimization [5].

- Model selection: Gaussian Process models tend to surpass Chemprop models when training data are sparse, though both show comparable recall of top binders on larger datasets [5].

- Noise tolerance: The addition of artificial Gaussian noise up to a certain threshold still allows models to identify clusters with top-scoring compounds, though excessive noise (<1σ) impacts predictive and exploitative capabilities [5].

Cutting-Edge Methodologies and Protocols

The APEX Protocol: Approximate-but-Exhaustive Search

Numerion Labs has developed the APEX (Approximate-but-Exhaustive Search) protocol, a computational approach that enables exhaustive evaluation of 10 billion virtual compounds in under 30 seconds on a single NVIDIA GPU [2]. This represents a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional methods that required months to analyze libraries of this scale. APEX works by pairing deep learning surrogates with GPU-accelerated enumeration over structured chemical spaces, allowing it to virtually evaluate billions of potential starting points in seconds [2].

A key innovation in the APEX protocol is its leverage of COSMOS – Numerion's structure-based, generative pre-trained foundation model trained to predict molecular binding and function [2]. Unlike traditional methods that focus on compound similarity or physicochemical filters, COSMOS enables APEX to prioritize compounds with genuine biological relevance by predicting binding affinity and optimal drug-like properties [2]. In benchmark tests, APEX successfully retrieved the top one million biologically promising compounds from a 10-billion-compound library in under 30 seconds, demonstrating its capability to identify high-scoring compounds that meet key drug-like property constraints across diverse protein targets including kinases, GPCRs, proteases, and nuclear receptors [2].

Schrödinger's Active Learning Glide Workflow

Schrödinger has developed a modern virtual screening workflow that leverages machine learning-enhanced docking and absolute binding free energy calculations to screen ultralarge libraries of up to several billion purchasable compounds with improved accuracy [3]. Their approach uses Active Learning Glide (AL-Glide), which combines machine learning with docking to apply enrichment to libraries of billions of compounds while only docking a fraction of the library [3].

Table 1: Schrödinger's Modern Virtual Screening Workflow Components

| Component | Function | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Glide (AL-Glide) | ML-guided docking that iteratively trains a model to proxy docking | Reduces computational cost by docking only a fraction of the library |

| Glide WS | Advanced docking using explicit water information | Improves pose prediction and reduces false positives |

| Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) | Calculates binding free energies between bound and unbound states | Accurately scores diverse chemotypes without a reference compound |

| Solubility FEP+ | Estimates fragment solubility at predicted potency | Enables identification of potent, soluble fragments |

The AL-Glide process begins with a manageable batch of compounds selected from the complete dataset and docked. These compounds are added to the training set, and the model iteratively improves as it becomes a better proxy for the docking method [3]. While typical docking with Glide might take a few seconds per compound, the ML model can evaluate predictions significantly faster, leading to a dramatic increase in throughput [3]. After the AL-Glide screen, full docking calculations are performed on the best-scored compounds (typically 10-100 million compounds), which are then rescored using Glide WS to leverage explicit water information in the binding site [3]. The most promising compounds then undergo rigorous rescoring with Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+), which accurately calculates binding free energies and can evaluate diverse chemotypes without requiring a similar, experimentally measured reference compound [3].

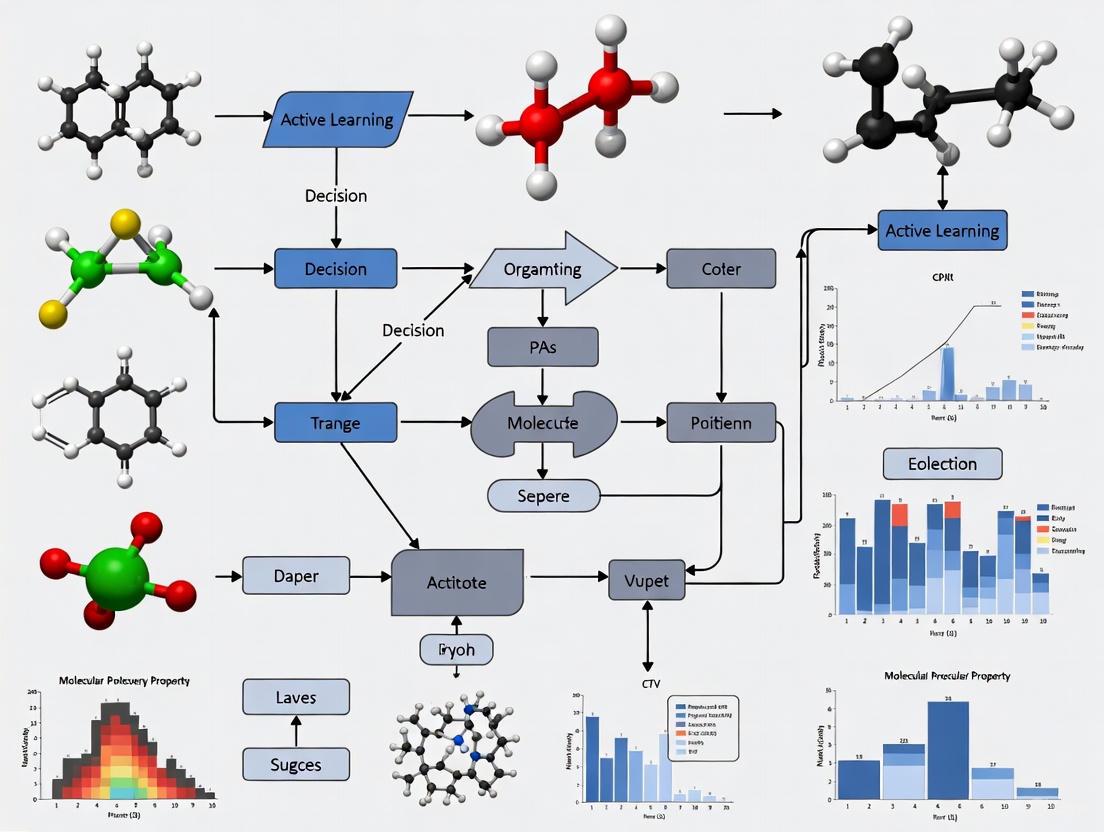

Diagram 1: Modern Virtual Screening Workflow. This illustrates the multi-stage computational pipeline for efficiently screening ultra-large compound libraries, from initial filtering to experimental validation.

iScore: Machine Learning-Based Scoring Functions

Anyo Labs has developed iScore, a machine learning-based scoring function that predicts the binding affinity of protein-ligand complexes with unprecedented speed and precision [1]. Unlike traditional methods that rely heavily on explicit knowledge of protein-ligand interactions and extensive atomic contact data, iScore leverages a unique set of ligand and binding pocket descriptors [1]. This innovative approach bypasses the time-consuming conformational sampling stage, enabling rapid screening of vast molecular libraries [1].

The development of iScore employed three distinct machine learning methodologies: deep neural networks (iScore-DNN), random forest (iScore-RF), and extreme gradient boosting (iScore-XGB) [1]. In practice, Anyo Labs used these methods to screen two large commercial libraries totaling 46 million compounds against the therapeutic target Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase in just a few hours [1]. From the top 20,000 prioritized compounds, post-processing filters for solubility, structural diversity, and pharmacokinetic properties reduced the set to 32 representative compounds for experimental testing [1]. Of these, two compounds demonstrated low nanomolar inhibitory activity and four exhibited low micromolar potency, validating the speed and predictive power of this AI-driven drug discovery pipeline [1].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Performance Comparison of Screening Methods

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Advanced Screening Methodologies

| Methodology | Library Size | Screening Time | Hit Rate | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Virtual Screening [3] | Hundreds of thousands to few million | Days to weeks | 1-2% | Established methods, simpler implementation |

| APEX Protocol [2] | 10 billion compounds | <30 seconds | Not specified | GPU-accelerated, exhaustive search of chemical space |

| Schrödinger AL-Glide [3] | Several billion compounds | Not specified | Double-digit percentages | Combines ML docking with FEP+ validation |

| Anyo Labs iScore [1] | 46 million compounds | Few hours | 6.25% (2/32 nanomolar) | Rapid screening with high precision |

The performance advantages of these modern approaches are substantial. Schrödinger's modern virtual screening workflow has enabled their Therapeutics Group to consistently achieve double-digit hit rates across a broad range of targets, a significant improvement over traditional 1-2% hit rates [3]. This dramatically reduces the number of compounds that need to be synthesized and tested to reach a project's lead candidate, substantially lowering overall costs and compressing project timelines [3].

Active Learning Protocol Optimization

Benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated how different active learning parameters influence performance in ligand-binding affinity prediction [5]. This research used four affinity datasets for different targets (TYK2, USP7, D2R, Mpro) to evaluate machine learning models and sampling strategies:

Table 3: Active Learning Parameter Optimization

| Parameter | Optimal Setting | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Batch Size | Larger batches | Increases recall of top binders and correlation metrics, especially on diverse datasets |

| Subsequent Batch Sizes | 20-30 compounds | Provides desirable balance between exploration and exploitation |

| Model Selection for Sparse Data | Gaussian Process models | Superior to Chemprop models when training data are limited |

| Noise Tolerance | Up to 1σ threshold | Maintains ability to identify top-scoring compound clusters |

These parameter optimizations enable researchers to design more effective active learning protocols for their specific virtual screening challenges, particularly when dealing with the sparse data environments common in early drug discovery.

Implementation Framework

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Ultra-Large Library Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| COSMOS Foundation Model [2] | AI/ML Model | Structure-based prediction of molecular binding and function | Biological relevance prioritization in APEX protocol |

| iScore (DNN, RF, XGB) [1] | ML Scoring Function | Predicts protein-ligand binding affinity with high speed | Replacement for traditional scoring functions |

| Active Learning Glide (AL-Glide) [3] | ML-Enhanced Docking | Combines machine learning with molecular docking | Efficient screening of billion-compound libraries |

| Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) [3] | Physics-Based Calculation | Computes absolute binding free energies | High-accuracy rescoring of top candidates |

| Ultra-Large Libraries (Enamine REAL, etc.) [3] | Compound Database | Provides billions of synthesizable compounds | Chemical space for virtual screening |

Integrated Workflow for Optimal Screening

The most effective approach to addressing the computational bottleneck combines multiple advanced methodologies into an integrated workflow. The diagram below illustrates how these components interact in a comprehensive screening pipeline:

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Screening Pipeline. This comprehensive workflow shows the integration of rapid AI pre-screening with high-accuracy validation and active learning feedback.

The computational bottleneck in ultra-large library screening, once a fundamental constraint on drug discovery progress, is being effectively addressed through the integration of active learning methodologies, AI-native screening protocols, and advanced scoring functions. These approaches enable researchers to comprehensively explore chemical spaces containing billions of compounds in practical timeframes, moving from assessing less than 0.1% of available compounds to conducting exhaustive searches that dramatically improve hit rates and scaffold diversity [2] [3].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging trends including the integration of AI-driven in silico design with automated robotics for synthesis and validation, enabling iterative model refinement that compresses drug discovery timelines exponentially [6]. As these technologies mature, they hold the potential to fundamentally reshape pharmaceutical development, potentially replacing certain preclinical requirements and animal tests with AI methods that can perform the same functions with a fraction of the resources [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these advanced computational approaches is no longer optional but essential for remaining competitive in the increasingly AI-driven landscape of modern drug discovery.

Active learning (AL) is a supervised machine learning strategy designed to optimize the process of data selection and model training by iteratively selecting the most informative data points for labeling. In the context of virtual screening for drug discovery, this approach has become a critical tool for efficiently navigating the vastness of modern chemical libraries, which can contain billions of compounds [7] [8]. The core premise of an active learning workflow is the iterative feedback loop, a cycle that strategically selects compounds for computationally expensive evaluation to maximize the discovery of hits while minimizing resource consumption [9]. This methodology is particularly valuable when dealing with ultra-large chemical spaces, where exhaustive screening is computationally intractable [10] [11]. By framing the search within a broader thesis on the foundations of active learning, this guide details the core components that constitute a robust AL workflow for virtual screening, providing researchers and scientists with a blueprint for its implementation.

The Active Learning Feedback Loop: A Core Architecture

The active learning workflow is architected around a self-improving cycle that creates a feedback loop between a machine learning model and an oracle—typically a human expert or a high-fidelity scoring function. This loop allows the model to selectively query the oracle for the most valuable information, thereby learning more efficiently than passive approaches [12] [8]. The fundamental cycle can be broken down into five key stages, which are visualized in the diagram below.

Diagram Title: Core Active Learning Iterative Feedback Loop

The process begins with a small, initial set of labeled data used to train a preliminary surrogate model. The model then interacts with a large pool of unlabeled data, employing a query strategy to select the most promising candidates for evaluation by the oracle. The newly acquired labels are added to the training set, and the model is retrained, thus completing one iteration of the loop. This cycle repeats, with the model becoming progressively more adept at identifying high-value compounds [12] [8] [9]. This iterative method stands in stark contrast to passive learning, where a model is trained on a static, pre-defined dataset. The active approach dynamically guides the exploration of chemical space, leading to significant reductions in the number of compounds that require expensive computational or experimental assessment [12] [11].

Core Components of the Workflow

A functional active learning system for virtual screening is built upon several interconnected components, each playing a critical role in the efficiency and success of the campaign.

The Initial Labeled Dataset

The process is initialized with a small but critical set of labeled compounds. This "seed" data is used to train the first instance of the surrogate model. The composition of this initial set can influence the early direction of the search, and it can be derived from known actives, a random sampling of the library, or pre-existing screening data [8] [9].

The Surrogate Model

The surrogate model is a machine learning model that learns a structure-property relationship to predict the performance of unscreened compounds. Its role is to approximate the output of the expensive oracle, thus enabling the prioritization of the unlabeled pool. Architectures can vary, including models like Directed-Message Passing Neural Networks, which have demonstrated high performance in navigating large molecular libraries [11].

The Query Strategy

The query strategy is the algorithm that decides which compounds from the unlabeled pool should be evaluated next. Its selection is the primary driver of efficiency in the AL cycle. Common strategies include:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Selects compounds for which the model's prediction is most uncertain, effectively targeting the decision boundaries of the model [12] [8].

- Diversity Sampling: Aims to select a batch of compounds that are diverse from each other and from the existing training set, ensuring broad exploration of the chemical space and preventing over-concentration in specific regions [12] [8].

- Expected Improvement: Selects compounds that are expected to provide the greatest improvement to the model's performance or the highest probability of being a top-scoring hit, often balancing exploration and exploitation [11].

The Oracle

In virtual screening, the oracle is the high-cost, high-fidelity evaluation method used to score the selected compounds. This is typically a computational method such as molecular docking with a tool like Glide or AutoDock Vina, or a more rigorous physics-based method like Absolute Binding Free Energy Perturbation (ABFEP) [7] [10]. The labels provided by the oracle (e.g., docking scores, binding free energies) form the ground truth used to update the surrogate model.

The Stopping Criteria

A predefined stopping criterion determines when to terminate the iterative loop. This could be a performance threshold (e.g., identification of a certain number of high-affinity hits), a computational budget (e.g., a maximum number of oracle evaluations), or a performance plateau where additional iterations no longer yield significant improvements [8].

Quantitative Performance of Active Learning

The effectiveness of active learning is demonstrated by its ability to identify a high proportion of top-performing compounds after evaluating only a small fraction of a virtual library. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of Active Learning in Virtual Screening

| Study / Protocol | Virtual Library Size | Key Performance Metric | Computational Cost Reduction | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vina-MolPAL | Not Specified | Achieved the highest top-1% recovery rate in benchmarking. | Significant reduction vs. exhaustive screening. | [7] |

| Directed-Message Passing NN | 100 million compounds | Identified 94.8% of the top-50,000 ligands. | Evaluation of only 2.4% of the library. | [11] |

| SILCS-MolPAL | Not Specified | Reached comparable accuracy and recovery to other protocols. | Effective at larger batch sizes. | [7] |

| FEgrow-AL (SARS-CoV-2 Mpro) | Combinatorial R-group/linker space | Identified novel designs with weak activity; generated compounds highly similar to known hits. | Enabled fully automated, structure-based prioritization for purchase. | [9] |

These results underscore a consistent theme: active learning protocols can achieve enrichment levels comparable to exhaustive screening at a fraction of the computational cost. For instance, one study demonstrated the capability to find nearly 95% of the best hits from a 100-million-compound library by docking less than 2.5% of its contents [11]. This makes AL a powerful strategy for practical drug discovery campaigns against targets like the SARS-CoV-2 main protease, where it can guide the selection of compounds for synthesis and testing from ultra-large libraries [9].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Implementing an active learning workflow requires careful design of the experimental protocol. Below is a detailed methodology based on a prospective study targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro), which serves as an excellent template.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Software for an AL Workflow

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in the Workflow | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein & Ligand Structures | Starting Data | Provides the structural basis for growing and docking compounds. | PDB structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with a fragment hit [9]. |

| FEgrow Software | Modeling Software | Builds and optimizes ligand conformations in the protein binding pocket using hybrid ML/MM. | https://github.com/cole-group/FEgrow [9]. |

| R-group & Linker Libraries | Chemical Libraries | Defines the combinatorial chemical space for virtual compound generation. | User-defined or provided libraries (e.g., 500 R-groups, 2000 linkers) [9]. |

| Scoring Function (Oracle) | Evaluation Software | Provides the primary label (e.g., docking score, binding affinity) for the surrogate model. | gnina (CNN scoring), PLIP interactions, custom functions [9]. |

| Machine Learning Library | Software Library | Implements the surrogate model and the active learning query strategies. | Python libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, DeepChem) [12] [11]. |

| On-Demand Compound Database | Chemical Database | "Seeds" the workflow with synthetically accessible compounds for prospective testing. | Enamine REAL database [9]. |

Workflow Initialization:

- Input: Begin with a receptor structure (e.g., from a crystal structure) and a defined ligand core with a growth vector. This core is typically derived from a known fragment hit.

- Chemical Space Definition: Define the virtual library by supplying libraries of linkers and R-groups. The FEgrow package includes a library of 2000 common linkers and ~500 R-groups, but users can supply their own.

Compound Building and Oracle Evaluation:

- Growing: FEgrow automatically merges the core, linker, and R-group to generate a new compound.

- Conformational Sampling: An ensemble of ligand conformations is generated using the ETKDG algorithm, with the core atoms restrained to their input positions.

- Pose Optimization: The ligand conformers are optimized within the rigid protein binding pocket using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., AMBER FF14SB in OpenMM) or a more advanced hybrid ML/MM potential.

- Scoring: The optimized poses are scored using an oracle function, such as the gnina convolutional neural network scoring function or a function that incorporates protein-ligand interaction profiles (PLIP).

Active Learning Cycle:

- An initial subset of the combinatorial library is built and scored to create a starting labeled dataset.

- A machine learning surrogate model (e.g., a random forest or neural network) is trained on this data to predict the oracle score from molecular features.

- The trained model predicts the scores for the entire unscreened virtual library.

- A query strategy (e.g., uncertainty sampling, expected improvement) selects the next batch of promising linkers and R-groups for evaluation.

- This batch is built, scored by the FEgrow oracle, and the results are added to the training set.

- The model is retrained, and the loop repeats for a set number of iterations or until convergence.

Prospective Validation:

- The final prioritized compounds can be cross-referenced with on-demand chemical libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) to select synthetically accessible molecules for purchase and experimental testing in a biochemical assay (e.g., a fluorescence-based Mpro activity assay).

This protocol's workflow, integrating the core components, is illustrated below.

Diagram Title: FEgrow Active Learning Workflow Integration

The iterative feedback loop is the foundational engine of an active learning workflow for virtual screening. Its core components—the surrogate model, the query strategy, and the oracle—work in concert to create an efficient, self-improving system for navigating massive chemical spaces. As virtual screening libraries continue to expand into the billions of compounds, the adoption of such intelligent, adaptive workflows is transitioning from an advantageous option to a practical necessity. The quantitative benchmarks and detailed experimental protocols outlined in this guide provide a solid foundation for researchers to implement and adapt these powerful methods, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

Modern drug discovery faces an unprecedented challenge: efficiently searching exponentially growing chemical libraries that now contain billions of synthesizable compounds [13]. Traditional physics-based virtual screening methods like molecular docking become computationally prohibitive at this scale, with estimated processing times stretching to hundreds of thousands of hours for comprehensive library screening [13]. This computational bottleneck has catalyzed the adoption of active learning frameworks that strategically guide exploration of the chemical search space by combining surrogate models with intelligent acquisition functions. This technical guide examines the core terminology and methodologies underpinning this paradigm shift, providing researchers with the conceptual foundation needed to implement efficient AI-accelerated virtual screening pipelines.

Core Terminology and Concepts

Surrogate Models: Approximating Complex Physical Simulations

Surrogate models are machine learning systems trained to approximate the outcome of computationally expensive simulations, dramatically accelerating the screening process while maintaining reasonable accuracy [13]. In virtual screening, these models learn the relationship between molecular representations and target properties—typically binding affinity or binding classification—without performing explicit physical simulations [13].

These models operate through two primary approaches:

- Classification Surrogates: Predict whether a given ligand will bind to a target protein, achieving up to 80× increased throughput compared to traditional docking when trained on just 10% of a dataset [13].

- Regression Surrogates: Predict continuous binding affinity scores for ligand-protein pairs, providing a 20% throughput increase over docking when trained on 40% of available data with a Spearman rank correlation of 0.693 [13].

Implementation typically employs random forest algorithms due to their reduced overfitting, high accuracy, and efficiency compared to deep learning models, with molecular descriptors generated by tools like RDKit's Descriptor module providing the feature representation [13].

Acquisition Functions: The Decision Engine of Active Learning

Acquisition functions are mathematical criteria that determine which compounds should be selected for expensive evaluation (e.g., docking or experimental testing) in each iteration of an active learning cycle [14]. These functions balance the exploration of uncertain regions of chemical space with the exploitation of promising areas known to contain high-affinity compounds.

The most common acquisition strategies include:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Selects compounds where the surrogate model exhibits highest prediction uncertainty, often measured through entropy: (H(p) = -\sum pi \log2(p_i)) [14].

- Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement (BALD): Maximizes the mutual information between model parameters and predictions, identifying compounds where model ensembles disagree most [14].

- Expected Improvement: Favors compounds with the highest potential improvement over the current best candidate [15].

- Upper Confidence Bound: Selects compounds using (\mu(x) + \beta\sigma(x)), balancing mean prediction (\mu(x)) and uncertainty (\sigma(x)) [15].

Chemical Search Space: The Frontier of Discoverable Compounds

The chemical search space represents the universe of synthetically feasible molecules that can be screened against a biological target. Modern libraries like Enamine's REAL Compounds space contain over 48 billion make-on-demand compounds, creating both opportunity and computational challenge [13]. This space is characterized by its:

- Immense dimensionality with structural diversity spanning vast regions of possible molecular structures [16].

- Synthetically accessible regions constrained by reaction rules and available building blocks [17].

- Optimization landscapes with complex topology containing multiple local optima and sparse global optima [17].

Efficient navigation of this space requires specialized algorithms like Chemical Space Annealing (CSA) that combine global optimization with fragment-based virtual synthesis to rapidly identify promising regions [17].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Surrogate Models Versus Traditional Docking

| Method | Throughput (Molecules/Time Unit) | Accuracy Metric | Training Data Required | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Surrogate | 80× higher than smina [13] | Binary binding classification [13] | 10% of dataset [13] | Initial library triage |

| Regression Surrogate | 20% higher than smina [13] | Spearman ρ = 0.693 [13] | 40% of dataset [13] | Affinity ranking |

| Physics-Based Docking (smina) | Baseline (∼30 sec/molecule) [13] | Enrichment factor varies by target [18] | N/A | Final validation |

| RosettaVS | Not specified | EF1% = 16.72 (CASF2016) [18] | N/A | High-precision screening |

Table 2: Chemical Search Space Characteristics and Screening Efficiency

| Method | Chemical Space Size | Computational Efficiency | Synthesizability | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Library Screening | 10^6-10^9 compounds [13] | Low (full enumeration) | High (pre-synthesized) | Comprehensive coverage |

| CSearch | Optimized subspace [17] | 300-400× more efficient [17] | High (fragment-based) | Global optimization |

| Active Learning Platforms | Multi-billion compounds [18] | 7 days for screening [18] | Variable | Intelligent selection |

| Fragment-Based Space | 192,498 fragments [17] | High (combinatorial) | Very high | BRICS rules |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Surrogate Model Training Protocol

Benchmarking Set Preparation The DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) benchmarking set provides the foundation for model training and validation, containing diverse active binders and decoys for multiple targets [13]. The protocol involves:

- Target Selection: Choose 10+ targets from the DUD-E diverse subset (e.g., ADRB1, AKT1, AMPC, CDK2) [13].

- Data Splitting: Partition data into training (70%), validation (10%), and test (20%) sets, maintaining class balance [17].

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate molecular descriptors using RDKit's Descriptor module, capturing physicochemical properties including molecular weight, surface area, logP, and topological indices [13].

- Model Training: Implement random forest classifier/regressor using scikit-learn with default hyperparameters, training separate models for each target [13].

- Performance Validation: Assess using area under the curve (AUC) for classification and Spearman correlation for regression tasks [13].

Key Consideration: Training set size significantly impacts performance, with 10% sufficient for classification and 40% needed for regression tasks [13].

Active Learning Workflow for Virtual Screening

OpenVS Platform Protocol The OpenVS platform implements an active learning cycle for ultra-large library screening [18]:

Active Learning Screening Workflow

- Initialization: Select a random subset (0.1-1%) from the multi-billion compound library [18].

- Docking: Process initial subset using high-speed docking modes (e.g., RosettaVS VSX) [18].

- Model Training: Train target-specific neural network on docking results to predict binding scores [18].

- Compound Selection: Apply acquisition functions (e.g., uncertainty sampling, expected improvement) to select the most informative next batch [18].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for 10-50 cycles or until convergence [18].

- Validation: Subject top-ranked compounds to high-precision docking (e.g., RosettaVS VSH) and experimental verification [18].

Key Innovation: This approach screens billions of compounds by docking only 1-5% of the library, completing in under 7 days versus months for exhaustive screening [18].

Chemical Space Navigation Protocol

Chemical Space Annealing (CSA) Methodology CSearch implements a global optimization algorithm for navigating synthesizable chemical space [17]:

- Initialization: Create a diverse bank of 60 seed molecules from drug-like chemical space [17].

- Fragment Database: Curate 192,498 non-redundant fragments from commercial collections with maximum Tanimoto similarity of 0.7 [17].

- Virtual Synthesis: Generate trial compounds using BRICS reaction rules, combining fragments from seed molecules with partner fragments from the database [17].

- Selection: Replace bank members with trial compounds that show improved objective values or increased diversity [17].

- Annealing: Gradually reduce diversity radius (Rcut) from initial 0.425 to 40% over 20 cycles, transitioning from exploration to exploitation [17].

Performance: CSearch demonstrates 300-400× higher computational efficiency than virtual library screening while maintaining synthesizability and diversity comparable to known ligands [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for Active Learning-Based Virtual Screening

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | Molecular descriptor calculation and fingerprint generation [13] | Open source |

| scikit-learn | Machine learning library | Implementation of random forest and other surrogate models [13] | Open source |

| smina/AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking | Physics-based binding affinity calculation for training data [13] | Open source |

| DUD-E dataset | Benchmarking set | Curated actives and decoys for model training and validation [13] | Free academic access |

| BRICS rules | Reaction framework | Fragment-based virtual synthesis for chemical space exploration [17] | Implemented in RDKit |

| RosettaVS | Docking suite | High-precision pose prediction and scoring for validation [18] | Open source |

| Enamine REAL Space | Compound library | 48B+ synthesizable compounds for ultra-large screening [13] | Commercial |

| OpenVS platform | Active learning system | Integrated workflow for AI-accelerated virtual screening [18] | Open source |

Integration and Workflow Diagram

Virtual Screening System Integration

This integrated framework demonstrates how the three core components interact to form a complete active learning system for drug discovery. The surrogate model rapidly approximates the chemical landscape, the acquisition function intelligently guides exploration, and the chemical search space defines the boundaries of discoverable therapeutics. Together, they enable researchers to navigate billion-compound libraries with unprecedented efficiency, transforming virtual screening from a computational bottleneck into a discovery accelerator.

In the computational domain of drug discovery, active learning has emerged as a pivotal strategy for navigating the vast search spaces of ultralarge compound libraries. This machine learning paradigm operates through an iterative cycle where a surrogate model selects the most informative data points from a pool of unlabeled candidates to be labeled by an expensive computational or physical experiment [19]. At the heart of every active learning strategy lies a critical decision: the exploration-exploitation trade-off. This trade-off compels the algorithm to choose between exploration—selecting samples from uncertain regions of the chemical space to improve the model's general understanding—and exploitation—focusing on regions already predicted to be high-performing to maximize immediate gains [20] [21]. The effective balance of this trade-off directly dictates the efficiency of virtual screening campaigns, influencing the speed and cost of identifying hit candidates from libraries containing billions of molecules [22].

Quantitative Foundations: Measuring Trade-off Efficacy

The performance of active learning strategies, and thus the success of their exploration-exploitation balance, is quantitatively evaluated using specific metrics. The following table summarizes the key performance indicators from recent virtual screening studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Active Learning in Drug Discovery Applications

| Application Domain | Key Result | Efficiency Gain | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening (99.5M library) | Identified 94.8% of top-50k compounds | After screening only 0.6% of the library (vs. 2.4% with previous methods) | [22] [20] |

| Synergistic Drug Combination Screening | Discovered 60% of synergistic pairs | After exploring only 10% of the combinatorial space | [21] |

| Small-Molecule Virtual Screening (50k library) | 78.36% top-500 retrieval rate | After 5 iterations (6% of library screened) using a pretrained model | [22] |

The enrichment factor (EF) is another crucial metric, defined as the ratio of the percentage of top-k molecules retrieved by active learning to the percentage retrieved by random selection [20] [22]. For example, a random forest model with a greedy acquisition strategy achieved an EF of 9.2 on a 10k compound library, meaning it was 9.2 times more efficient at finding top-scoring ligands than a brute-force search [20].

Algorithmic Frameworks for Managing the Trade-off

Acquisition Functions: The Decision Engine

The balance between exploration and exploitation is algorithmically managed by acquisition functions. These functions use the predictions of the surrogate model to score and prioritize unlabeled compounds. The choice of acquisition function is a primary method for controlling the trade-off.

Table 2: Common Acquisition Functions and Their Role in the Trade-off

| Acquisition Function | Mechanism | Bias | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy | Selects compounds with the best-predicted score (e.g., lowest docking score) | Pure Exploitation | High-performance, focused search; can get stuck in local optima [20] [22] |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Selects compounds based on predicted score + β * uncertainty | Balanced | Balances finding good compounds with learning about uncertain regions; β controls balance [20] [22] |

| Thompson Sampling (TS) | Selects compounds using a random draw from the posterior predictive distribution | Balanced | Probabilistic exploration; performance can be sensitive to model miscalibration [20] |

| Uncertainty Sampling | Selects compounds where the model is most uncertain | Pure Exploration | Ideal for improving the global model accuracy [23] |

The Impact of Batch Size

The acquisition batch size—the number of compounds selected and evaluated in each active learning iteration—is a critical hyperparameter. Smaller batch sizes allow for more frequent model updates and a more dynamic, adaptive balance of the trade-off. In synergistic drug combination screening, the synergy yield ratio was observed to be higher with smaller batch sizes [21]. Furthermore, dynamic tuning of the exploration-exploitation strategy during the campaign can lead to enhanced performance [21].

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Screening

Implementing an active learning framework for virtual screening requires a structured protocol. The following workflow, common to pool-based active learning, outlines the core steps.

Active Learning Workflow for Virtual Screening

Protocol Steps

- Initialization: Begin with a large virtual library of unlabeled compounds (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL). An initial batch of compounds is selected at random for labeling. This initial random sampling is crucial for bootstrapping the model [20] [23].

- Objective Function Evaluation: The selected compounds are passed to the objective function. In structure-based virtual screening, this is typically computational docking using tools like AutoDock Vina, which scores protein-ligand interactions [20] [22]. In ligand-based screening, this could be a 3D similarity calculation to a known active compound [22].

- Surrogate Model Training: A machine learning model (the surrogate) is trained on the accumulated data of compounds and their corresponding scores. Common architectures include Directed-Message Passing Neural Networks (D-MPNN), Random Forests (RF), and pretrained transformers (MoLFormer) or graph neural networks (MolCLR) [20] [22].

- Acquisition and Iteration: The trained surrogate model predicts the docking scores and uncertainties for all remaining compounds in the pool. A pre-defined acquisition function (e.g., Greedy, UCB) uses these predictions to select the next, most informative batch of compounds to evaluate. The process returns to Step 2 [20].

- Termination: The cycle continues until a stopping criterion is met, such as a fixed budget of docking calculations, a target number of hits identified, or performance convergence. The top-scoring compounds identified through this process are reported as virtual hits [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential computational "reagents" required to implement an active learning framework for virtual screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Active Learning-driven Virtual Screening

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in the Workflow | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Compound Library | Data | The search space of candidate molecules. | ZINC, Enamine REAL (Billions of compounds) [22] |

| Docking Software | Software | The objective function; scores protein-ligand binding. | AutoDock Vina [20] |

| Surrogate Model | Algorithm | Predicts docking scores; guides compound selection. | D-MPNN, Pretrained MoLFormer, Random Forest [20] [22] |

| Acquisition Function | Algorithm | Balances exploration vs. exploitation to select the next batch. | Greedy, UCB, Thompson Sampling [20] |

| Active Learning Platform | Software Framework | Integrates components and manages the iterative learning cycle. | MolPAL [20] [22] |

| Cellular/Genomic Features | Data | Provides context for the target; can improve prediction accuracy. | Gene expression profiles from GDSC database [21] |

Advanced Strategies and Future Directions

Hybrid and Uncertainty-Based Strategies

Beyond standard acquisition functions, advanced strategies are being benchmarked, particularly in materials science, with high relevance to drug discovery. These include uncertainty-driven methods (like LCMD and Tree-based-R) and diversity-hybrid methods (like RD-GS), which have been shown to outperform random sampling and geometry-only heuristics, especially in the early, data-scarce phases of a campaign [23]. The integration of these strategies with Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) presents a promising avenue for maintaining robust performance even as the underlying surrogate model evolves [23].

The Role of Pretraining and Representation

The sample efficiency of active learning is profoundly influenced by the choice of the surrogate model. Pretrained deep learning models, such as the molecular language model MoLFormer or the graph neural network MolCLR, learn powerful molecular representations from large, unlabeled datasets. These models have demonstrated a consistent 8% improvement in hit recovery rate over strong baselines, as they can form better generalizations from limited labeled data, thereby making more informed decisions in the exploration-exploitation trade-off from the very first iterations [22].

Visualizing the Trade-off Decision Logic

The core logic an acquisition function uses to balance exploration and exploitation, particularly the UCB strategy, can be visualized as a decision process based on predicted score and model uncertainty.

Exploration vs. Exploitation Decision

Building Your Pipeline: A Practical Guide to Active Learning Workflows and Components

In the modern drug discovery pipeline, virtual screening (VS) stands as a critical computational technique for identifying promising therapeutic candidates from vast chemical libraries. Despite its advantages in time and cost savings over traditional high-throughput methods, conventional VS has yielded fewer than twenty marketed drugs to date, indicating a significant need for improvement [24]. The integration of active learning frameworks, which iteratively select the most informative data points for model training, is revolutionizing this field by maximizing the efficiency of resource-intensive experimental validations.

Central to this paradigm is the choice of a surrogate model—a machine learning model that approximates the behavior of a complex, computationally expensive simulation or experimental assay. Within the context of virtual screening, an effective surrogate model predicts key molecular properties, such as biological activity or binding affinity, guiding the iterative sample selection in an active learning cycle. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of three prominent surrogate models—Random Forests (RF), standard Neural Networks (NNs), and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)—evaluating their applicability, performance, and implementation for active learning in virtual screening.

Surrogate Model Architectures: A Technical Comparison

Random Forests (RF)

Random Forests are an ensemble learning method that operates by constructing a multitude of decision trees at training time. For virtual screening, RF models typically use molecular descriptors or fingerprints as input features. Their predictions are made by aggregating the outputs of individual trees, which helps to reduce overfitting—a common issue with single decision trees.

- Key Advantages: A primary strength of RF is its computational efficiency. Studies have shown that RF and XGBoost (a gradient-boosting variant) are among the most efficient algorithms, requiring only seconds to train a model even on large datasets [25]. Furthermore, RF models offer excellent interpretability; techniques like SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) can be used to explore established domain knowledge by highlighting the importance of specific molecular descriptors [25].

Neural Networks (NNs) and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs)

Neural Networks, particularly Deep Neural Networks, consist of multiple layers of interconnected neurons that can learn hierarchical representations from input data. In descriptor-based DNN models, traditional molecular descriptors and fingerprints serve as the input, and the network learns to map these features to molecular properties.

- Performance and Role: While DNNs are powerful, their performance as standalone descriptor-based models can be surpassed by other methods for certain tasks. For instance, Support Vector Machines (SVM) often achieve the best predictions for regression tasks, and RF or XGBoost are highly reliable for classification tasks [25]. However, NNs remain a foundational architecture and are frequently used as the readout function in more complex models like GNNs.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs represent a specialized deep-learning architecture designed to operate directly on graph-structured data. In drug discovery, a molecule is naturally represented as a graph, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [25]. The core operation of a GNN is message passing, where information (node features and edge features) is iteratively exchanged and aggregated between neighboring nodes [26]. This allows the GNN to learn rich representations that encode both the intrinsic features of atoms and the intricate topological relationships between them.

Several GNN architectures have been developed, including:

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN): Update a node's representation by aggregating feature information from its neighbors [26].

- Graph Attention Networks (GAT): Assign different attention weights to neighbors, allowing the model to focus on more relevant nodes during aggregation [26].

- Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN): A general framework that iteratively passes messages between neighboring nodes to update node representations [26].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The selection of an optimal surrogate model requires a clear understanding of its predictive performance across diverse chemical endpoints. The following tables summarize key benchmarking results from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Surrogate Models on Various Property Prediction Tasks [25]

| Model Category | Example Algorithms | Average Performance (Regression) | Average Performance (Classification) | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor-Based | SVM, XGBoost, RF, DNN | SVM generally best for regression | RF & XGBoost reliable classifiers | XGBoost & RF most efficient (seconds for training) |

| Graph-Based | GCN, GAT, MPNN, Attentive FP | Variable; can be outperformed by descriptor-based models | Can excel on larger/multi-task datasets (e.g., Attentive FP) | Computational cost "far less" than graph-based models |

Table 2: Specialized GNN Model Performance on Specific Virtual Screening Tasks

| GNN Model | Application / Target | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network | Target-specific scoring for cGAS & kRAS | Significant superiority over generic scoring functions; remarkable robustness & accuracy | [27] |

| VirtuDockDL Pipeline (GNN) | VP35 protein (Marburg virus), HER2, TEM-1, CYP51 | 99% accuracy, F1=0.992, AUC=0.99 (HER2); surpasses DeepChem & AutoDock Vina | [28] |

| GNNSeq (Hybrid GNN+RF+XGBoost) | Protein-ligand binding affinity (PDBbind) | PCC=0.784 (refined set), AUC=0.74 (DUDE-Z); trains on 5000+ complexes in ~1.5 hours | [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Implementation

Data Preparation and Molecular Representation

The foundation of any effective surrogate model is high-quality, consistently represented data.

- Descriptor-Based Models (RF/NN): Input is typically a combination of:

- Molecular Descriptors: 1-D and 2-D descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, topological polar surface area) calculated using tools like RDKit or MOE software [25].

- Molecular Fingerprints: Binary vectors representing the presence or absence of specific substructures (e.g., PubChem fingerprints, ECFP) [25].

- Graph-Based Models (GNN): Input is a molecular graph where:

GNN Architecture Specification (VirtuDockDL Example)

A state-of-the-art GNN pipeline for virtual screening can be implemented as follows [28]:

- Graph Convolution Layer: Employ specialized GNN layers (e.g., GCN, ARMAConv) to process molecular graphs. The core operation involves a linear transformation of node features followed by batch normalization:

h'_v = W · h_vandh''_v = max(0, BatchNorm(h'_v))[28]. - Residual Connections & Dropout: Incorporate residual connections for layers with matching input/output dimensions to mitigate vanishing gradients:

h'''_v = h_v + h''_v. Apply dropout for regularization [28]. - Feature Fusion: Fuse graph-derived features with engineered molecular descriptors and fingerprints by concatenation:

f_combined = ReLU(W_combine · [h_agg ; f_eng] + b_combine)[28]. - Readout/Prediction Layer: The final molecular representation is passed through a fully connected neural network layer to produce a prediction (e.g., activity score, binding affinity).

Model Training and Active Learning Integration

- Training Loop: For each active learning iteration:

- Query Strategy: Use the current surrogate model to select the most informative unlabeled data points (e.g., those with highest uncertainty or predicted improvement).

- Experimental Oracle: Send the selected candidates for experimental validation or high-fidelity simulation (e.g., molecular docking).

- Model Update: Augment the training set with the new labeled data and retrain the surrogate model.

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Regression (Affinity/Potency): Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root MSE (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Pearson Correlation Coefficient (R) [26].

- Classification (Active/Inactive): Accuracy, F1-Score, ROC-AUC, Precision-Recall AUC (AUPRC) [26] [28].

- Generation (De Novo Design): Validity, Uniqueness, Novelty, Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential datasets and software tools that form the "research reagents" for building surrogate models in virtual screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Surrogate Model Development

| Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Access / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoleculeNet Benchmarks | Curated Datasets | Standardized benchmark for training and evaluating molecular property prediction models | https://molemunet.org/datasets-1 [26] |

| PDBbind Database | Curated Dataset | Provides experimentally measured protein-ligand binding affinities for training binding prediction models like GNNSeq | [29] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for processing SMILES, calculating molecular descriptors, generating fingerprints, and creating molecular graphs | [25] [28] |

| PyTorch Geometric | Deep Learning Library | A library built upon PyTorch specifically for developing and training GNN models. | [28] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interpretation Tool | Explains the output of machine learning models, crucial for interpreting descriptor-based models like RF. | [25] |

Decision Framework and Signaling Pathways for Model Selection

The choice between RF, NN, and GNN is not a one-size-fits-all decision but should be guided by the specific constraints and goals of the virtual screening campaign. The following diagram and decision logic provide a structured selection pathway.

Model Selection Decision Pathway

The internal workflow of a GNN surrogate model within an active learning cycle for virtual screening can be visualized as follows.

GNN Workflow in Active Learning for Virtual Screening

The strategic selection of a surrogate model is a cornerstone for building an efficient active learning pipeline in virtual screening. As evidenced by recent benchmarking studies, Random Forests offer an compelling combination of computational speed, robustness, and interpretability, making them an excellent initial choice, particularly for descriptor-based projects with limited data or computational resources [25]. Standard Neural Networks provide a flexible, powerful framework, especially when used as part of a descriptor-based DNN or as a component in larger architectures.

However, for the complex challenge of molecular property prediction, Graph Neural Networks represent the cutting edge. Their innate ability to learn directly from the graph topology of a molecule allows them to capture nuanced structure-property relationships that other models may miss [24] [26]. When sufficient data is available, GNNs have demonstrated superior accuracy in critical tasks like target-specific scoring and binding affinity prediction [27] [28] [29]. The emergence of hybrid models, which integrate GNNs with other powerful algorithms like XGBoost and Random Forest, further pushes the boundaries of predictive performance and generalizability [29].

Ultimately, the choice is not static. An active learning framework allows for model re-evaluation and potential switching as the project evolves and more data is collected. By grounding the decision in a clear understanding of each model's strengths and weaknesses, as outlined in this guide, researchers can strategically leverage these powerful tools to significantly accelerate the discovery of new therapeutic agents.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on the foundations of active learning for virtual screening research, the selection of an acquisition function is a critical strategic decision. As virtual chemical libraries expand into the billions of compounds, exhaustive screening becomes computationally prohibitive [30]. Active learning, specifically Bayesian optimization, mitigates this by iteratively selecting the most promising compounds for expensive computational evaluation (e.g., molecular docking) based on a surrogate model [30] [18]. The acquisition function is the algorithm within this framework that balances the exploration of uncertain regions of the chemical space with the exploitation of known promising areas, thereby guiding the search for high-affinity ligands with maximal efficiency. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the predominant acquisition functions—Greedy, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), Thompson Sampling (TS), and Expected Improvement (EI)—synthesizing recent performance data and experimental protocols to inform their application in drug discovery.

Core Principles of Acquisition Functions

In a typical pool-based active learning setup for virtual screening, a surrogate model is trained on an initial set of docked molecules. This model predicts the docking score (and its uncertainty) for every molecule in the vast, unlabeled virtual library. The acquisition function uses these predictions to score and rank all unlabeled compounds. The top-ranked compounds are then "acquired," meaning they are selected for the computationally expensive docking calculation. The results of these new docking experiments are added to the training set, and the surrogate model is retrained, creating an iterative cycle [30] [31].

The diagram below illustrates this core workflow and the role of the acquisition function.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance of acquisition functions can vary significantly depending on the surrogate model architecture, the size of the virtual library, and the specific target. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent virtual screening studies to facilitate comparison.

Table 1: Performance on Small Virtual Libraries (~10,000 compounds). Data adapted from Graff et al., showing the percentage of the true top-100 ligands found after evaluating only 6% of the library [30].

| Acquisition Function | Random Forest Surrogate | Neural Network Surrogate | Message Passing NN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy | 51.6% | 66.8% | 68.0% |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | 43.2% | 62.4% | 65.2% |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | 49.2% | 56.0% | 63.6% |

| Thompson Sampling (TS) | 27.6% | 58.8% | 62.8% |

Table 2: Performance on an Ultra-Large Library (100 Million compounds). Data showing the fraction of the top-50,000 ligands identified with a Directed-Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN) surrogate model [30].

| Acquisition Function | % of Library Tested | % of Top-50k Found |

|---|---|---|

| Greedy | 2.4% | 89.3% |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | 2.4% | 94.8% |

Key Takeaways from Quantitative Data:

- Greedy and UCB Are Top Performers: In both small and ultra-large virtual screens, Greedy (also referred to as "probability of improvement") and UCB strategies consistently deliver high performance, often identifying over 85% of top hits after evaluating less than 3% of the library [30].

- Surrogate Model Choice Matters: The performance of an acquisition function is tied to the surrogate model. Neural network-based models (standard and message-passing) generally outperform random forest models, leading to significant efficiency gains across all acquisition functions [30].

- Thompson Sampling Can Be Unreliable: In some contexts, particularly with simpler surrogate models like Random Forest that yield high uncertainty, Thompson Sampling can perform poorly, behaving almost randomly. However, its performance improves markedly with more accurate surrogate models [30]. Enhanced versions of TS, such as those using roulette wheel selection, have shown better performance in complex, combinatorial libraries [32].

- Simplicity Can Be Effective: A comprehensive reality check on deep active learning found that under many general settings, the simple Maximum Entropy acquisition function "outperforms all the other methods" and can be a robust baseline [33].

Detailed Function Methodologies

Greedy (a.k.a. Probability of Improvement)

This strategy is purely exploitative. It selects the candidates that the surrogate model predicts will have the best score, with no explicit mechanism for exploration.

- Mathematical Formulation: (x{next} = \arg\min{x \in U} \mu(x)) where ( \mu(x) ) is the surrogate model's predicted mean docking score for molecule (x), and (U) is the pool of unlabeled molecules [30].

- Experimental Context: In a virtual screen of a 100-million compound library, a Greedy strategy using a D-MPNN surrogate found 89.3% of the top-50,000 ligands after docking only 2.4% of the total library, demonstrating its high efficiency in exploitation [30].

- Best Use Cases: When the surrogate model is highly accurate and the chemical space is relatively smooth, allowing a greedy search to quickly converge on optimal regions.

Upper Confidence Bound (UCB)

UCB balances exploration and exploration by selecting candidates that maximize a weighted sum of the predicted score (exploitation) and the prediction uncertainty (exploration).

- Mathematical Formulation: (x{next} = \arg\min{x \in U} \left( \mu(x) - \beta \cdot \sigma(x) \right)) where ( \sigma(x) ) is the predicted standard deviation (uncertainty) for molecule (x), and ( \beta ) is a tunable parameter that controls the trade-off [30] [31].

- Experimental Context: Using the same setup as the Greedy strategy, UCB achieved a slightly higher performance, recovering 94.8% of the top-50,000 ligands, highlighting the benefit of its explicit exploration component in ultra-large spaces [30].

- Best Use Cases: Highly effective in large, diverse chemical spaces where balancing exploration and exploitation is crucial to avoid local optima.

Thompson Sampling (TS)

A probabilistic strategy that selects candidates by sampling from the posterior distribution of the surrogate model. Molecules are chosen with a probability equal to them being the optimal candidate.

- Methodology: For each candidate molecule, a score is sampled from its posterior predictive distribution (e.g., ( \tilde{y} \sim N(\mu(x), \sigma^2(x)) )). The molecule with the best sampled score is selected [32].

- Experimental Context: Performance is highly dependent on the surrogate model. With a Random Forest model on a small library, it found only 27.6% of top hits, but with a Neural Network, this jumped to 58.8% [30]. Recent enhancements, such as Roulette Wheel Selection, have improved its performance in multi-component combinatorial libraries [32].

- Best Use Cases: Particularly well-suited for combinatorial libraries where search is conducted in reagent space rather than product space, and for parallelized batch selection.

Expected Improvement (EI)

EI selects the candidate that is expected to provide the greatest improvement over the current best-observed score.

- Mathematical Formulation: (x{next} = \arg\max{x \in U} \mathbb{E} [ \max(0, g^* - g(x)) ]) where ( g^* ) is the current best-observed score, and ( g(x) ) is the unknown true score of candidate (x). The expectation is taken over the posterior of the surrogate model [31].

- Experimental Context: In benchmarking across multiple materials science domains, EI was a common and reliable choice when paired with Gaussian Process or Random Forest surrogate models [31]. In virtual screening, its performance was solid but often trailed behind Greedy and UCB [30].

- Best Use Cases: A general-purpose, well-balanced acquisition function suitable for a wide range of optimization problems, including virtual screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and methodologies referenced in the studies cited herein, which are essential for implementing active learning for virtual screening.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Active Learning-Driven Virtual Screening

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Provides the "black-box" objective function by predicting protein-ligand binding affinity [30]. | The primary evaluation function in many benchmarking studies; its score is what the active learning loop aims to optimize. |

| MolPAL | Active Learning Software | An open-source Python package specifically designed for molecular pool-based active learning [30]. | The software used in the foundational study to benchmark acquisition functions and surrogate models. |

| RosettaVS | Virtual Screening Platform | A physics-based docking and virtual screening method that can be integrated with active learning protocols [18]. | Used in an AI-accelerated platform to screen billion-compound libraries, demonstrating the practical application of these methods. |

| D-MPNN | Surrogate Model | A graph neural network architecture that learns directly from molecular graph structures [30]. | Consistently a top-performing surrogate model architecture, leading to high efficiency across various acquisition functions. |

| ROCS | 3D Shape Similarity Tool | Performs shape-based virtual screening using 3D molecular overlays [32]. | Used in studies benchmarking Thompson sampling and other acquisition functions on ultralarge combinatorial libraries. |

Integrated Experimental Workflow

Implementing an active learning campaign for virtual screening requires a structured protocol. The following diagram and detailed steps outline a robust methodology based on successful implementations in the literature.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Define the primary goal, e.g., "identify the top 50,000 scoring compounds from a 100M compound library against protein target PDB:4UNN" [30].

- Library Preparation: Curate the virtual library in a standardized format (e.g., SMILES) and prepare 3D conformers if required by the docking software.

Initialization (Warm Start):

Iterative Active Learning Cycle:

- Surrogate Model Training: Train the chosen model (e.g., D-MPNN) on all currently available (docked) data. Use molecular graphs or fingerprints as input and docking scores as the regression target [30].

- Acquisition and Selection: Use the trained surrogate model to predict scores and uncertainties for the entire remaining pool. Apply the chosen acquisition function (e.g., UCB) to rank all molecules. Select the top

Bmolecules (the "batch" or "acquisition size") for docking. Typical batch sizes can range from 100 to several thousand compounds per cycle [30]. - Evaluation and Retraining: Dock the newly selected molecules to obtain their true scores. Add this new data to the training set. Monitor performance metrics such as the cumulative number of top-k hits found versus the number of docking experiments performed.

Termination and Analysis:

- Stopping Criteria: Terminate the cycle when a pre-defined computational budget is exhausted (e.g., after 2.4% of the library is docked) or when the rate of new hit discovery plateaus [30].

- Hit Validation: The final list of top-scoring compounds identified through the active learning process should be considered for further experimental validation (e.g., synthesis and binding assays) [18].

The selection of an acquisition function is a nuanced decision that can dramatically impact the efficiency of a virtual screening campaign. While Greedy and Upper Confidence Bound strategies have demonstrated superior performance in large-scale virtual screens, the optimal choice is context-dependent. Researchers must consider the characteristics of their chemical library, the accuracy of the chosen surrogate model, and the available computational budget. The experimental protocols and benchmarking data presented here provide a foundation for making an informed decision. As the field progresses, the integration of more sophisticated surrogate models and the development of robust, open-source platforms like MolPAL and OpenVS will make these active learning strategies increasingly accessible, empowering researchers to navigate the vast chemical space of modern drug discovery with unprecedented efficiency.

The field of computational drug discovery is undergoing a paradigm shift driven by the exponential growth of commercially available chemical compounds, with libraries now containing billions of molecules. Traditional virtual screening methods, which rely on exhaustively docking every compound in a library, have become computationally prohibitive at this scale. Active learning (AL) has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this challenge by creating intelligent, iterative screening pipelines that dramatically reduce the number of docking calculations required. These protocols use machine learning models to prioritize compounds for docking based on their predicted potential, continuously refining their selection criteria as more data is generated. The integration of AL with molecular docking engines represents a foundational advancement for modern virtual screening research, enabling the efficient exploration of ultra-large chemical spaces with limited computational resources. This technical guide examines the integration of active learning methodologies with three prominent docking engines: the widely used open-source tool AutoDock Vina, the industry-leading commercial solution Schrödinger Glide, and the high-accuracy flexible protocol RosettaVS. We provide a comprehensive analysis of their respective performance characteristics, implementation protocols, and practical applications in contemporary drug discovery campaigns.

Docking Engines: Capabilities and Performance Profiles

AutoDock Vina

AutoDock Vina is one of the most widely used open-source docking engines, renowned for its ease of use and computational efficiency. Its design philosophy emphasizes simplicity, requiring minimal user input and parameter adjustment while delivering rapid docking results. Vina utilizes a scoring function that combines gaussian terms for van der Waals interactions, a hydrogen bonding term, and a hydrophobic term, but notably lacks explicit electrostatic components [34]. Recent advancements in Vina 1.2.0 have significantly expanded its capabilities, including support for macrocyclic flexibility, explicit water molecules through hydrated docking, and the implementation of the AutoDock4.2 scoring function [34]. These developments, coupled with new Python bindings for workflow automation, make Vina particularly amenable to integration into large-scale active learning pipelines. Performance benchmarks indicate that Vina achieves approximately 82% accuracy in binding pose prediction on standard datasets, positioning it as a robust and accessible tool for high-throughput virtual screening [35].

Schrödinger Glide

Schrödinger Glide represents the industry standard for commercial docking solutions, offering high accuracy across diverse receptor types including small molecules, peptides, and macrocycles. The platform provides multiple specialized workflows: Glide SP (Standard Precision) is optimized for high-throughput virtual screening, while Glide XP (Extra Precision) offers enhanced accuracy for smaller compound sets, and Glide WS incorporates explicit water thermodynamics from WaterMap calculations to improve pose prediction and reduce false positives [36]. A key advantage of Glide is its integration with active learning protocols specifically designed for screening ultra-large libraries (>1 billion compounds), enabling significant computational savings through intelligent compound prioritization [36]. The software also offers extensive customization options through docking constraints to focus on specific chemical spaces or interaction patterns.

RosettaVS and Flexible Docking Protocols

RosettaVS is an open-source virtual screening method built upon the Rosetta molecular modeling suite, distinguished by its sophisticated treatment of receptor flexibility through full side-chain and limited backbone movement during docking simulations [18]. This approach employs a physics-based force field (RosettaGenFF-VS) that combines enthalpy calculations (ΔH) with entropy estimates (ΔS) for improved binding affinity ranking [18]. The protocol operates in two specialized modes: Virtual Screening Express (VSX) for rapid initial screening, and Virtual Screening High-precision (VSH) for final ranking of top hits with full receptor flexibility. Benchmarking studies demonstrate that RosettaVS achieves state-of-the-art performance, with a top 1% enrichment factor of 16.72 on the CASF-2016 dataset, significantly outperforming other methods [18]. This high accuracy comes at increased computational cost, making it particularly well-suited for integration with active learning approaches that can minimize unnecessary calculations.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Docking Engines

| Docking Engine | Docking Accuracy | Top 1% Enrichment Factor | Receptor Flexibility | Key Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | 82% [35] | Not Reported | Limited side-chain | Open-source, rapid execution, hydrated docking |

| Schrödinger Glide | High (industry standard) | Not Reported | Limited | WaterMap integration, extensive constraints |

| RosettaVS | Superior to Vina [18] | 16.72 [18] | Full side-chain, limited backbone | Physics-based force field, entropy modeling |

Active Learning Integration Methodologies

Core Active Learning Concepts for Virtual Screening

Active learning frameworks for virtual screening operate through an iterative cycle of selection, evaluation, and model refinement. Unlike traditional screening that tests all compounds, AL employs a surrogate model that predicts the likely docking scores of undocked compounds, selecting only the most promising candidates for actual docking calculations. This approach typically requires only 1-10% of the computational resources of exhaustive screening while maintaining similar hit discovery rates [7] [37]. The key challenge in batch active learning is selecting a diverse set of informative compounds that collectively improve the model, rather than simply choosing the top individual predictions. Advanced AL methods address this by maximizing the joint entropy of selected batches, which considers both the uncertainty of individual predictions and the diversity between them within the chemical space [38].

Implementation with Specific Docking Engines