Active Learning in Drug Discovery: Current Applications, Methodological Advances, and Future Outlook

This comprehensive review examines the transformative role of active learning (AL) in modern drug discovery.

Active Learning in Drug Discovery: Current Applications, Methodological Advances, and Future Outlook

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the transformative role of active learning (AL) in modern drug discovery. As a subfield of artificial intelligence, AL employs iterative feedback processes to select the most informative data for labeling, thereby addressing key challenges such as the vastness of chemical space and the limited availability of labeled experimental data. This article systematically explores AL's foundational principles and its practical applications across critical stages of drug discovery, including virtual screening, molecular generation and optimization, prediction of compound-target interactions, and ADMET property forecasting. It further delves into methodological innovations, troubleshooting common implementation challenges, and validating AL's effectiveness through comparative analysis and real-world case studies. By synthesizing the latest research and applications, this review provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with actionable insights for integrating AL into their workflows, ultimately highlighting its potential to significantly accelerate and enhance the efficiency of the drug discovery pipeline.

Understanding Active Learning: Core Principles and Its Rising Importance in Modern Drug Discovery

Active learning represents a paradigm shift in machine learning, moving beyond passive training on static datasets to an interactive, iterative process of intelligent data selection. This guided exploration of the chemical space is particularly transformative for drug discovery, where it strategically selects the most informative compounds for experimental testing, thereby accelerating the identification of promising drug candidates. By framing the selection of data points as an experimental design problem, active learning creates a feedback loop where machine learning models guide the acquisition of new knowledge, which in turn refines the models. This whitepaper examines the core mechanisms of active learning, details its implementation through various query strategies, and presents its groundbreaking applications across the drug discovery pipeline, from virtual screening to molecular optimization.

The Core Concepts of Active Learning

Fundamental Principles

Active learning is a supervised machine learning approach that strategically selects data points for labeling to optimize the learning process [1]. Its primary objective is to minimize the amount of labeled data required for training while maximizing model performance [1] [2]. This is achieved through an iterative feedback process where the learning algorithm actively queries an information source (often a human expert or an oracle) to label the most valuable data points from a pool of unlabeled instances [3] [2].

In traditional supervised learning, models are trained on a static, pre-labeled dataset—an approach often termed passive learning. In contrast, active learning dynamically interacts with the data selection process, prioritizing informative samples that are expected to provide the most significant improvements to model performance [1] [4]. This characteristic renders it exceptionally valuable for domains like drug discovery, where obtaining labeled data through experiments is costly, time-consuming, and resource-intensive [3].

The Active Learning Workflow

The active learning process operates through a structured, cyclical workflow [1] [5] [4]:

- Initialization: The process begins with a small, initial set of labeled data points.

- Model Training: A machine learning model is trained on the current labeled dataset.

- Query Strategy: The trained model is used to evaluate a large pool of unlabeled data. A predefined query strategy selects the most informative subset for labeling.

- Human/Oracle Annotation: The selected data points are presented to an expert or oracle (e.g., through wet-lab experiments) for labeling.

- Model Update: The newly labeled data is incorporated into the training set, and the model is retrained.

- Iterative Loop: Steps 3 through 5 are repeated until a stopping criterion is met, such as performance convergence or exhaustion of resources.

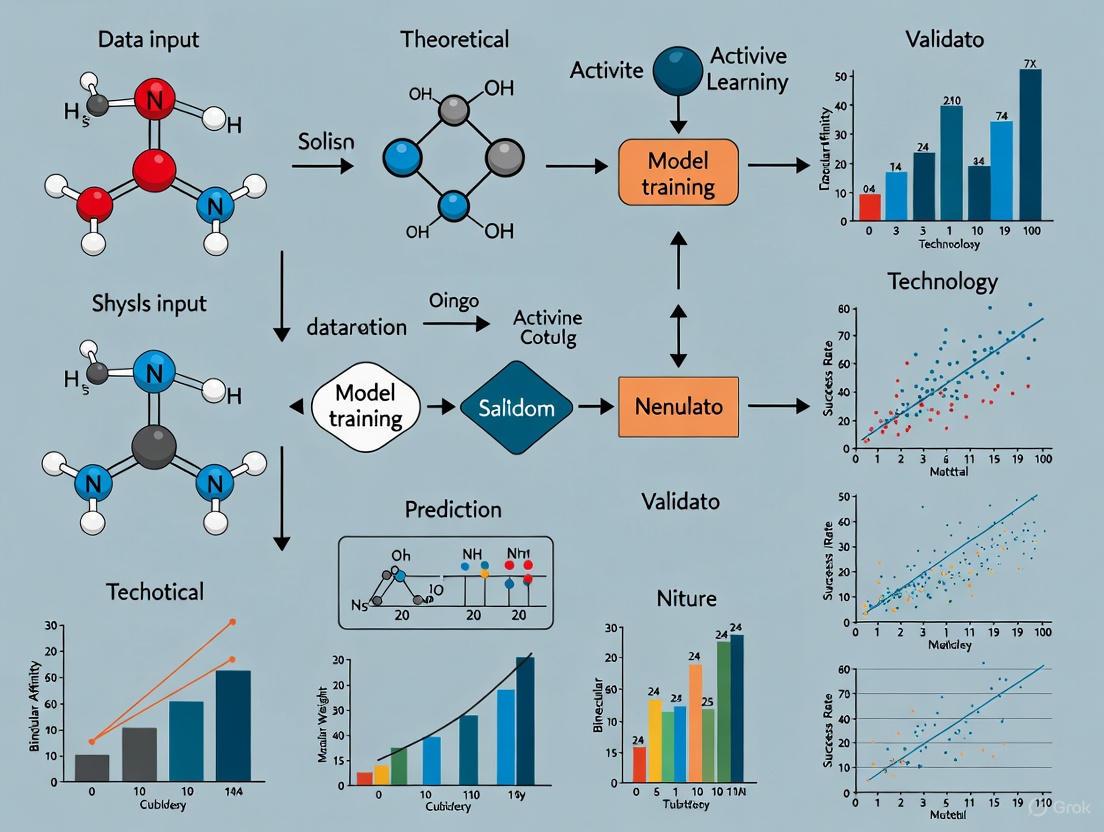

This workflow can be visualized as a continuous cycle of learning and selection, as depicted in the following diagram.

Query Strategies: The Intelligence Engine

The "intelligence" in active learning is driven by its query strategy, the algorithm that decides which unlabeled instances are most valuable for labeling. These strategies balance the exploration of the data space with the exploitation of the model's current weaknesses.

Sampling Frameworks

The operational context determines how unlabeled data is presented and selected, leading to three primary sampling frameworks [2] [5] [4]:

- Pool-based Sampling: The most common scenario, where the algorithm evaluates the entire pool of unlabeled data to select the most informative batch of samples for labeling [2]. This is memory-intensive but highly effective for curated datasets.

- Stream-based Selective Sampling: Data is presented sequentially in a stream, and the model must decide in real-time whether to query the label for each instance, typically based on an uncertainty threshold [1] [5]. This is suitable for continuous data generation but may lack a global view of the data distribution.

- Membership Query Synthesis: The algorithm generates new, synthetic data instances for labeling rather than selecting from an existing pool [2]. This is powerful when data is scarce but risks generating unrealistic or unrepresentative samples if the underlying data distribution is not well-modeled.

Core Query Algorithms

Within these frameworks, specific algorithms quantify the "informativeness" of data points. The following table summarizes the most prevalent strategies.

Table 1: Core Active Learning Query Strategies and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

| Strategy | Core Principle | Mechanism | Drug Discovery Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling [1] [5] | Selects data points where the model's prediction is least confident. | Measures uncertainty via entropy, least confidence, or margin sampling. | Identifying compounds with borderline predicted activity for a target protein. |

| Diversity Sampling [1] [5] | Selects a representative set of data points covering the input space. | Uses clustering (e.g., k-means) or similarity measures to maximize coverage. | Ensuring a screened compound library represents diverse chemical scaffolds. |

| Query By Committee [2] | Selects data points where a committee of models disagrees the most. | Uses measures like vote entropy to find instances with high model disagreement. | Resolving conflicting predictions from multiple QSAR models for a new compound. |

| Expected Model Change [2] | Selects data points that would cause the greatest change to the current model. | Calculates the gradient of the loss function or other impact metrics. | Prioritizing compounds that would most significantly update a property prediction model. |

| Expected Error Reduction [2] | Selects data points expected to most reduce the model's generalization error. | Estimates future error on the unlabeled pool after retraining with the new point. | Optimizing the long-term predictive accuracy of a toxicity endpoint model. |

Recent advancements have introduced more sophisticated batch selection methods. For instance, COVDROP and COVLAP are novel methods designed for deep batch active learning that select batches by maximizing the joint entropy—the log-determinant of the epistemic covariance of the batch predictions [6]. This approach explicitly balances uncertainty (variance of predictions) and diversity (covariance between predictions), leading to more informative batches and significant potential savings in the number of experiments required [6].

Active Learning in Drug Discovery: Experimental Protocols and Applications

Drug discovery is characterized by a vast chemical space to explore and expensive, low-throughput experimental labeling. This makes it an ideal domain for active learning, which has been applied across virtually all stages of the pipeline [3].

Key Application Areas and Protocols

Table 2: Active Learning Applications and Experimental Protocols in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Experimental Protocol / Workflow | Key Challenge Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening & Compound-Target Interaction Prediction [3] | 1. Train initial QSAR model on known active/inactive compounds.2. Use AL to prioritize unlabeled compounds for in silico or experimental screening.3. Iteratively retrain model with new data to guide subsequent screening cycles. | Compensates for shortcomings of high-throughput and structure-based virtual screening by focusing resources on the most promising chemical space [3]. |

| Molecular Generation & Optimization [3] [7] | 1. A generative model (e.g., RL agent) proposes new molecules.2. A property predictor (QSPR/QSAR) scores them for target properties.3. AL (e.g., using EPIG) selects generated molecules with high predictive uncertainty for expert/oracle feedback.4. The predictor is refined, guiding subsequent generation cycles. | Prevents "hallucination" where generators exploit model weaknesses to create molecules with artificially high predicted properties that fail experimentally [7]. |

| Molecular Property Prediction [3] [6] | 1. Start with a small dataset of compounds with measured properties (e.g., solubility, permeability).2. The AL model selects subsequent batches of compounds for experimental testing.3. The model is updated, improving its accuracy and applicability domain with each cycle. | Improves model accuracy and expands the model's reliable prediction domain (applicability domain) with fewer labeled data points [3]. |

Quantitative studies demonstrate the efficacy of this approach. For example, in benchmarking experiments on ADMET and affinity datasets, active learning methods like COVDROP achieved comparable or superior performance to random sampling with significantly less data, leading to a substantial reduction in the number of experiments needed [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing an active learning loop in drug discovery relies on a suite of computational and experimental "reagents."

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Active Learning in Drug Discovery

| Tool / Reagent | Function in the Active Learning Workflow |

|---|---|

| Initial Labeled Dataset (𝒟₀) | The small, trusted set of compound-property data used to bootstrap the initial model. Serves as the foundation of knowledge. |

| Machine Learning Model (fᵩ) | The predictive model (e.g., Graph Neural Network, Random Forest) that estimates molecular properties. Its uncertainty is the driver for data selection. |

| Query Strategy Algorithm | The core "intelligence" that calculates the utility of unlabeled compounds (e.g., uncertainty, diversity metrics). |

| Chemical Oracle / Expert | The source of ground-truth labels. This can be a high-throughput screening assay, a physics-based simulation, or a human expert providing feedback [7]. |

| Generative Model | In goal-oriented generation, this agent (e.g., an RL agent or variational autoencoder) explores the chemical space and proposes new candidate molecules. |

| Representation (Fingerprint) | A numerical representation of a molecule's structure (e.g., ECFP, count fingerprints) that enables computational analysis [7]. |

The integration of these components into a cohesive, automated, or semi-automated platform is crucial for the efficient operation of the active learning loop in a modern drug discovery setting.

Active learning represents a fundamental shift towards more efficient and intelligent scientific discovery. By implementing an iterative feedback loop for data selection, it directly addresses one of the most significant bottlenecks in drug discovery: the cost and time associated with experimental labeling. The core of this methodology lies in its diverse and powerful query strategies, which enable models to guide their own learning process by identifying the most valuable experiments to perform next. As the field progresses, the integration of active learning with advanced techniques like human-in-the-loop systems and sophisticated batch selection methods will further enhance its ability to navigate the vast complexity of biology and chemistry, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutics.

In modern drug discovery, active learning (AL) represents a paradigm shift from traditional, resource-intensive experimental processes to efficient, data-driven workflows. This machine learning subfield addresses a fundamental challenge: optimizing complex molecular properties while minimizing costly laboratory experiments. Active learning algorithms intelligently select the most informative data points for experimental testing, creating a virtuous cycle of model improvement and discovery acceleration. Within the pharmaceutical industry, this approach is transforming the multi-parameter optimization process required for drug development, particularly for ADMET properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) and binding affinity predictions that determine a compound's therapeutic potential [6].

The core value proposition of active learning lies in its strategic approach to data acquisition. Unlike traditional methods that rely on exhaustive testing or random selection, active learning systems quantify uncertainty and diversity within chemical space to prioritize compounds that will most improve model performance when tested. This is particularly valuable in drug discovery, where experimental resources are limited and chemical space is virtually infinite. By focusing resources on the most informative compounds, organizations can significantly compress discovery timelines and reduce costs while maintaining—or even improving—the quality of resulting candidates [6] [8].

Core Active Learning Workflow

The active learning workflow operates as an iterative, closed-loop system that integrates computational predictions with experimental validation. This cycle systematically expands the model's knowledge while focusing experimental resources on the most valuable data points. The process can be decomposed into four interconnected stages that form a continuous improvement loop.

The following diagram illustrates the complete active learning cycle in drug discovery:

Stage Descriptions

Initial Model Development: The process begins with an initial limited dataset of compounds with experimentally validated properties. This seed data trains the first predictive model, which might use neural networks, graph neural networks, or other deep learning architectures tailored to molecular data [6]. The quality and diversity of this initial dataset significantly influences how quickly the active learning system can identify promising regions of chemical space.

Query Strategy and Compound Selection: The trained model screens a vast library of untested compounds, applying selection strategies to identify the most valuable candidates for experimental testing. Rather than simply choosing compounds with predicted optimal properties, the system prioritizes based on uncertainty metrics and diversity factors. Advanced methods like COVDROP and COVLAP use Monte Carlo dropout and Laplace approximation to estimate model uncertainty and maximize the information content of each batch [6].

Experimental Testing and Data Generation: Selected compounds undergo synthesis and experimental validation using relevant biological assays. This represents the most resource-intensive phase of the cycle. The resulting experimental data provides ground-truth labels for the previously predicted properties. This stage transforms computational predictions into empirically verified data, creating the foundation for model improvement [6] [9].

Model Updating and Iteration: Newly acquired experimental data is incorporated into the training set, and the model is retrained with this expanded dataset. This updating process enhances the model's predictive accuracy and reduces uncertainty in previously ambiguous regions of chemical space. The updated model then begins the next cycle of compound selection, continuing until predefined performance criteria are met or resources are exhausted [6] [10].

Quantitative Performance of Active Learning Methods

Performance Metrics Across Dataset Types

Extensive benchmarking studies reveal significant performance advantages for advanced active learning methods compared to traditional approaches. The following table summarizes results across diverse molecular property prediction tasks:

Table 1: Performance comparison of active learning methods across public benchmark datasets

| Dataset Type | Dataset Name | Size | Best Performing Method | Key Performance Metric | Comparative Advantage vs. Random |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Aqueous Solubility [6] | 9,982 compounds | COVDROP | Rapid error reduction | Reaches target accuracy with 30-40% fewer experiments |

| Permeability | Caco-2 Cell Permeability [6] | 906 drugs | COVDROP | Model accuracy | 2x faster convergence to optimal predictions |

| Lipophilicity | Lipophilicity [6] | 1,200 compounds | COVLAP | Prediction precision | 50% reduction in required training data for same performance |

| Protein Binding | PPBR [6] | Not specified | BAIT | Handling of imbalanced data | Maintains stability with highly skewed distributions |

| Affinity Prediction | 10 ChEMBL & Internal Sets [6] | Varies by target | COVDROP | Affinity prediction accuracy | Identifies high-affinity compounds with 70% less testing |

Batch Selection Efficiency

A critical advantage of advanced active learning methods lies in their batch selection efficiency. The following table compares performance across methods when selecting batches of 30 compounds per iteration:

Table 2: Batch active learning method performance metrics (batch size = 30 compounds)

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Strength | Computational Complexity | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVDROP [6] | Monte Carlo dropout uncertainty estimation | Joint entropy maximization | Medium | ADMET optimization with neural networks |

| COVLAP [6] | Laplace approximation of posterior | Covariance matrix optimization | High | Small-molecule affinity prediction |

| BAIT [6] | Fisher information maximization | Parameter uncertainty reduction | Medium-high | Imbalanced dataset environments |

| k-Means [6] | Diversity-based clustering | Chemical space exploration | Low | Initial exploration of uncharted chemical space |

| Random [6] | No strategic selection | Baseline comparison | None | Control for method evaluation |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: ADMET Property Optimization

Objective: Efficiently optimize absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties for lead compounds using active learning.

Initial Setup:

- Data Requirements: Begin with 200-500 compounds with experimentally measured ADMET endpoints [6]

- Model Architecture: Implement graph neural networks or transformer-based models for molecular representation [6]

- Unlabeled Pool: Compile 50,000-5,000,000 virtual compounds from enumeratable chemical space

Procedure:

- Initial Training: Train initial model on seed data using stratified sampling to ensure representation across property ranges

- Uncertainty Quantification: For each iteration, apply Monte Carlo dropout (100 forward passes) to estimate predictive uncertainty for all compounds in unlabeled pool [6]

- Batch Selection: Use greedy determinant maximization to select 30 compounds that maximize joint entropy and diversity

- Experimental Validation: Perform high-throughput screening for relevant ADMET properties (e.g., solubility, metabolic stability)

- Model Updating: Retrain model with expanded dataset, applying transfer learning from pre-trained models when available

- Termination: Continue iterations until model performance plateaus or target accuracy is achieved (typically 10-15 cycles)

Validation: Evaluate using holdout test set with 20% of original data. Success criterion: 30% reduction in experimental requirements compared to random selection while maintaining prediction accuracy (R² > 0.7) [6].

Protocol 2: Ultra-Large Library Screening

Objective: Identify potent hits from billion-compound libraries using active learning-enhanced docking.

Initial Setup:

- Library Preparation: Prepare ultra-large library (1-10 billion compounds) in appropriate format for docking simulations

- Initial Sampling: Randomly select 5,000 compounds for initial docking using Glide or similar platform [11]

- Model Architecture: Implement Bayesian neural networks or random forests trained on docking scores

Procedure:

- Initial Screening: Dock initial random subset to generate training data

- Model Training: Train machine learning model to predict docking scores from molecular descriptors

- Prediction Phase: Apply trained model to entire library to identify high-scoring candidates

- Diversity Selection: Select 1,000 compounds from top predictions, ensuring structural diversity

- Validation Docking: Perform actual docking on selected compounds to verify predictions

- Iterative Refinement: Retrain model with new data, repeating process for 3-5 cycles

Performance Metrics: Successful implementation recovers ~70% of top-scoring hits identified through exhaustive docking while using only 0.1% of computational resources [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of active learning requires both computational tools and experimental resources. The following table details key components of the active learning infrastructure:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for active learning implementation

| Category | Item/Platform | Specific Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Platforms | DeepChem [6] | Open-source deep learning toolkit for drug discovery | Provides foundational architectures for molecular ML models |

| Schrödinger Active Learning Applications [11] | ML-enhanced molecular docking and FEP+ predictions | Screens billion-compound libraries with reduced computational cost | |

| Recursion OS [12] [13] | Integrated phenomics and chemistry platform | Maps biological relationships using phenotypic screening data | |

| Experimental Assays | CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [9] | Target engagement validation in intact cells | Confirms compound-target interactions in physiological conditions |

| High-Content Imaging [12] | Phenotypic screening at cellular level | Generates rich data for training phenotypic prediction models | |

| Automated Synthesis [14] | Robotic compound synthesis and testing | Enables rapid experimental validation of AI-designed compounds | |

| Data Management | Labguru/Titian Mosaic [14] | Sample management and data integration | Connects experimental data with AI models for continuous learning |

| Sonrai Discovery Platform [14] | Multi-omics data integration and analysis | Layers imaging, genomic, and clinical data for biomarker discovery |

Platform Integration and Industry Applications

Leading Platform Implementations

Major pharmaceutical companies and specialized technology providers have developed integrated platforms that implement active learning at scale:

Schrödinger's Active Learning Applications: This commercial implementation combines physics-based simulations with machine learning to accelerate key discovery stages. The platform offers two primary workflows: Active Learning Glide for ultra-large library screening and Active Learning FEP+ for lead optimization. In practice, this approach enables researchers to screen billions of compounds using only 0.1% of the computational resources required for exhaustive docking while recovering approximately 70% of top-performing hits [11]. The system employs Bayesian optimization techniques to select compounds that balance exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of known high-scoring regions.

Genentech's "Lab in the Loop": This strategic framework creates a tight integration between experimental and computational scientists. The approach establishes "a virtuous, iterative cycle" where computational models generate predictions that are experimentally tested, with results feeding back to refine the models [10]. This continuous feedback loop has been particularly effective in personalized cancer vaccine development, where models trained on data from previous patients improve neoantigen selection for new patients. The implementation demonstrates how active learning creates self-improving systems that enhance their predictive capabilities with each iteration.

Sanofi's Advanced Batch Methods: Sanofi's research team developed novel batch active learning methods specifically addressing drug discovery challenges. Their COVDROP and COVLAP approaches use sophisticated uncertainty quantification to select diverse, informative compound batches [6]. These methods have demonstrated particular value in ADMET optimization, where they achieve target prediction accuracy with 30-40% fewer experiments compared to traditional approaches. Implementation requires integration between their computational infrastructure and high-throughput experimental screening capabilities.

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The application of active learning in drug discovery continues to evolve with several promising emerging directions:

Generative Chemistry Integration: Active learning is increasingly combined with generative AI models that design novel molecular structures. Companies like Insilico Medicine use reinforcement learning in which active learning selects which generated compounds to synthesize and test, creating a closed-loop system that both designs and optimizes compounds [12] [13]. This integration represents a significant advancement beyond conventional virtual screening of static compound libraries.

Clinical Trial Optimization: Beyond preclinical discovery, active learning approaches are being applied to clinical development. Platforms like Insilico Medicine's inClinico use predictive models trained on historical trial data to optimize patient selection, endpoint selection, and trial design [13]. This application demonstrates how the active learning paradigm can extend throughout the entire drug development pipeline.

Cross-Modal Learning: Next-generation platforms like Recursion OS integrate diverse data types—including microscopy images, genomic data, and chemical structures—within their active learning frameworks [13]. This approach enables the identification of complex patterns that would be invisible when analyzing single data modalities, potentially uncovering novel biological mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

The fundamental workflow of initial model creation, iterative querying, and model updating represents a transformative approach to drug discovery. By strategically selecting the most informative experiments, active learning systems dramatically increase the efficiency of molecular optimization while reducing resource requirements. The quantitative evidence demonstrates that advanced methods like COVDROP and COVLAP can achieve equivalent or superior performance to traditional approaches while requiring 30-70% fewer experimental iterations [6].

Implementation success depends on effectively integrating computational and experimental workflows. Platforms that establish tight coupling between AI prediction and laboratory validation—such as Genentech's "Lab in the Loop" and Schrödinger's Active Learning Applications—demonstrate the practical potential of this approach [10] [11]. As the field advances, active learning methodologies will increasingly become foundational components of modern drug discovery infrastructure, enabling more rapid identification of novel therapeutics with enhanced probability of clinical success.

For researchers implementing these systems, success factors include: (1) investing in high-quality initial datasets that broadly represent chemical space, (2) establishing robust automated workflows for rapid experimental validation, and (3) selecting appropriate active learning strategies aligned with specific optimization objectives. With these elements in place, organizations can fully leverage the power of iterative learning to transform their drug discovery pipelines.

The primary objective of drug discovery is to identify specific target molecules with desirable characteristics within an enormous chemical space. However, the rapid expansion of this chemical space has rendered the traditional approach of identifying target molecules through exhaustive experimentation practically impossible. The effective application of machine learning (ML) in this domain is significantly hindered by the limited availability of accurately labeled data and the resource-intensive nature of obtaining such data [15]. Furthermore, challenges such as data imbalance and redundancy within labeled datasets further impede the application of ML methods [15]. In this context, active learning has emerged as a powerful computational strategy to address these fundamental challenges.

Active learning represents a subfield of artificial intelligence that encompasses an iterative feedback process designed to select the most informative data points for labeling based on model-generated hypotheses [15]. This approach uses the newly acquired labeled data to iteratively enhance the model's performance in a closed-loop system. The fundamental focus of AL research revolves around creating well-motivated functions that guide data selection, enabling the identification of the most valuable data in extensive databases [15]. This facilitates the construction of high-quality ML models or the discovery of more desirable molecules with significantly fewer labeled experiments.

The advantages of AL-guided data selection align exceptionally well with the challenges faced in drug discovery, particularly the exponential expansion of exploration space and issues with flawed labeled datasets [16] [15]. Consequently, AL has found extensive applications throughout the drug discovery pipeline, including compound-target interaction prediction, virtual screening, molecular generation and optimization, and molecular property prediction [16]. This technical guide explores the current state of AL in drug discovery, providing detailed methodologies, performance comparisons, and practical implementation frameworks to navigate vast chemical spaces with limited labeled data.

Fundamental Principles of Active Learning

Core Workflow and Operational Mechanism

Active learning operates through a dynamic, iterative feedback process that begins with creating an initial model using a limited set of labeled training data. The system then iteratively selects the most informative data points for labeling from a larger unlabeled dataset based on model-generated hypotheses and a well-defined query strategy [15]. The model is subsequently updated by integrating these newly labeled data points into the training set during each iteration. This AL process continues until it reaches a suitable stopping criterion, ensuring an efficient and targeted approach to data acquisition and model improvement [15].

The AL workflow typically involves these critical stages:

- Initialization: Training a preliminary model on a small labeled dataset

- Query Selection: Identifying the most valuable unlabeled instances using acquisition functions

- Labeling: Obtaining labels for selected instances through experimentation or simulation

- Model Update: Retraining the model with the expanded labeled dataset

- Convergence Check: Determining whether stopping criteria are met or returning to step 2

Key Query Strategies for Drug Discovery

Different query strategies have been developed to address various challenges in drug discovery applications:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Selects instances where the model exhibits highest prediction uncertainty, particularly valuable for refining decision boundaries in molecular property prediction [15].

- Diversity Sampling: Ensures selected batches represent diverse chemical space coverage, preventing redundancy and improving model generalizability [6].

- Expected Model Change: Prioritizes instances that would cause the most significant change to the current model parameters if their labels were known.

- Query-by-Committee: Utilizes an ensemble of models to select instances with the greatest disagreement among committee members.

Table 1: Active Learning Query Strategies and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

| Query Strategy | Mechanism | Primary Drug Discovery Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling | Selects instances with highest prediction uncertainty | Molecular property prediction, ADMET optimization | Rapidly improves model confidence in ambiguous regions |

| Diversity Sampling | Maximizes chemical diversity in selected batches | Virtual screening, hit identification | Broad exploration of chemical space, prevents redundancy |

| Expected Model Change | Prioritizes instances that would most alter current model | Lead optimization, QSAR modeling | Efficiently directs resources to most informative experiments |

| Query-by-Committee | Uses ensemble disagreement to select instances | Compound-target interaction prediction | Reduces model bias, improves generalization |

Applications in Drug Discovery Pipelines

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Virtual screening represents one of the most established applications of AL in drug discovery. Traditional virtual screening methods fall into two categories: structure-based approaches that require 3D structural information of targets, and ligand-based approaches that rely on known active compounds [15]. Both methods face significant limitations when dealing with ultra-large chemical libraries containing billions of compounds. Active learning effectively compensates for the shortcomings of both approaches by intelligently selecting the most promising compounds for evaluation [15].

Industry implementations demonstrate remarkable efficiency improvements. For example, Schrödinger's Active Learning Glide application can screen billions of compounds and recover approximately 70% of the same top-scoring hits that would be found through exhaustive docking, at just 0.1% of the computational cost [11]. This represents a 1000-fold reduction in resource requirements while maintaining high recall of promising candidates.

The application of novel batch AL methods has shown particularly strong performance in virtual screening scenarios. Methods like COVDROP and COVLAP utilize innovative sampling strategies to compute covariance matrices between predictions on unlabeled samples, then select subsets that maximize joint entropy [6]. This approach considers both uncertainty and diversity, rejecting highly correlated batches and ensuring broad exploration of chemical space.

Compound-Target Interaction Prediction

Predicting interactions between compounds and their biological targets represents a fundamental challenge in early drug discovery. AL approaches have demonstrated significant utility in this domain by efficiently guiding experimental testing to refine interaction models [15]. These methods are particularly valuable when dealing with emerging targets or target families with limited labeled data.

Advanced AL frameworks for compound-target interaction prediction often incorporate multi-task learning, transfer learning, and specialized sampling strategies to address the high class imbalance typically encountered in these problems [15]. The BE-DTI framework exemplifies this approach, combining ensemble methods with dimensionality reduction and active learning to efficiently map compound-target interaction spaces [15].

Molecular Optimization and Property Prediction

During lead optimization phases, AL guides the exploration of structural analogs to improve multiple properties simultaneously while maintaining potency. This multi-parameter optimization challenge is particularly well-suited to AL approaches, as they can efficiently navigate the high-dimensional chemical space to identify regions that satisfy multiple constraints [15].

In molecular property prediction, AL has demonstrated exceptional capability in addressing data quality issues. A case study on predicting drug oral plasma exposure implemented a two-phase AL pipeline that successfully sampled informative data from noisy datasets [8]. The AL-based model used only 30% of the training data to achieve a prediction accuracy of 0.856 on an independent test set [8]. In the second phase, the model explored a large diverse chemical space (855K samples) for experimental testing and feedback, resulting in improved accuracy and 50K new highly confident predictions, significantly expanding the model's applicability domain [8].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Active Learning in Drug Discovery Applications

| Application Domain | Dataset/Context | Performance Improvement | Resource Savings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening | Ultra-large libraries (billions) | Recovers ~70% of top hits [11] | 99.9% cost reduction [11] |

| Synergistic Drug Combinations | Oneil dataset (15,117 measurements) | Discovers 60% of synergies with 10% exploration [17] | 82% reduction in experiments [17] |

| Solubility Prediction | Aqueous solubility (9,982 molecules) | Faster convergence to target accuracy [6] | Reduced labeling requirements by 40-60% |

| Plasma Exposure Prediction | Oral drug plasma exposure | Accuracy of 0.856 with 30% of training data [8] | Expanded applicability to 50K new predictions |

| Affinity Optimization | TYK2 Kinase binding | Improved binding free energy predictions [6] | Reduced free energy calculations by 70% |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation Framework for Batch Active Learning

Batch active learning methods are particularly relevant for drug discovery applications where experimental testing typically occurs in batches rather than sequentially. Recent advances have introduced sophisticated approaches specifically designed for deep learning models commonly used in molecular property prediction.

The COVDROP and COVLAP methods represent innovative batch AL selection approaches that quantify uncertainty over multiple samples [6]. These methods compute a covariance matrix between predictions on unlabeled samples, then select the subset of samples with maximal joint entropy (information content) [6]. The algorithmic procedure follows these steps:

- Uncertainty Estimation: Use multiple methods (Monte Carlo dropout or Laplace approximation) to compute a covariance matrix C between predictions on unlabeled samples 𝒱

- Greedy Selection: Employ an iterative greedy approach to select a submatrix C_B of size B×B from C with maximal determinant

- Batch Diversity: The determinant maximization naturally enforces batch diversity by rejecting highly correlated batches

- Model Update: Incorporate the newly labeled batch into training data and update the model

This approach has been validated on several public drug design datasets, including cell permeability (906 drugs), aqueous solubility (9,982 molecules), and lipophilicity (1,200 compounds), demonstrating consistent outperformance over previous batch selection methods [6].

Active Learning for Synergistic Drug Combination Discovery

The application of AL to synergistic drug combination discovery requires specialized methodologies to address the unique challenges of this domain. Recent research has provided detailed guidance on implementing AL frameworks for identifying synergistic drug pairs [17].

The experimental protocol typically involves:

Data Preparation:

- Utilize synergy datasets (e.g., Oneil with 15,117 measurements, 38 drugs, 29 cell lines)

- Define synergistic pairs using established thresholds (e.g., LOEWE synergy score >10)

- Encode molecular features using Morgan fingerprints or other representations

- Incorporate cellular context through gene expression profiles from databases like GDSC

Model Selection and Training:

- Implement neural network architecture with combination operations (Sum, Max, Bilinear)

- Pre-train on existing synergy data when available

- Use appropriate evaluation metrics (PR-AUC for imbalanced synergy classification)

Active Learning Cycle:

- Start with initial batch of experimentally tested combinations

- Use selection criteria (e.g., uncertainty, diversity) to choose next batch

- Iteratively test, update model, and select subsequent batches

- Implement dynamic tuning of exploration-exploitation balance

This methodology has demonstrated the ability to discover 60% of synergistic drug pairs with only 10% exploration of the combinatorial space, representing an 82% reduction in experimental requirements [17].

Diagram 1: Active Learning Iterative Workflow in Drug Discovery

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools and Datasets

Successful implementation of active learning in drug discovery requires access to appropriate computational tools, datasets, and infrastructure. The following table summarizes key resources mentioned in recent literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Active Learning in Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Features/Capabilities | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | DeepChem [6], Schrödinger Active Learning Applications [11], ChemML [6] | Integration with deep learning models, batch selection algorithms, scalable chemistry-aware ML | General drug discovery pipelines, virtual screening |

| Molecular Representations | Morgan Fingerprints [17], MAP4 [17], MACCS [17], ChemBERTa [17] | Molecular encoding for ML models, capturing structural and functional properties | Compound characterization, similarity assessment |

| Cellular Context Features | GDSC Gene Expression [17], Single-cell Expression Profiles | Cellular environment representation, context-specific prediction | Synergistic drug combination prediction |

| Specialized Algorithms | COVDROP & COVLAP [6], BAIT [6], RECOVER [17] | Batch selection methods, uncertainty quantification, synergy prediction | Specific AL implementations for drug discovery |

| Benchmark Datasets | Oneil [17], ALMANAC [17], ChEMBL [6], Tox24 [18] | Experimental data for training and validation, standardized benchmarks | Method development and comparison |

Technical Considerations and Implementation Challenges

Optimization of Machine Learning Integration

Research has unequivocally demonstrated that the performance of combined ML models significantly influences the effectiveness of AL [15]. Several advanced ML algorithms, including reinforcement learning (RL) and transfer learning (TL), coupled with automated ML algorithm selection tools, have been seamlessly integrated into AL with promising results [15]. However, not all integrations of AL with advanced ML approaches have proven successful in drug discovery contexts, as observed with multitask learning where negative transfer can occur [15].

Key considerations for optimizing ML integration include:

- Model Architecture Selection: Choosing appropriate neural network architectures (GCN, GAT, transformers) based on data characteristics and task requirements [17]

- Uncertainty Quantification: Implementing robust uncertainty estimation methods (MC dropout, Laplace approximation, ensemble methods) for reliable query selection [6]

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Developing efficient hyperparameter tuning strategies that avoid overfitting, particularly in low-data regimes [18]

- Transfer Learning: Leveraging pre-trained models on large chemical databases to improve performance in data-scarce scenarios [6]

Addressing Data Imbalance and Quality Issues

Drug discovery datasets frequently suffer from severe class imbalance, particularly for rare properties like synergy (typically 1.5-3.5% prevalence) or toxicity endpoints (0.7-3.3% for assay interference) [17] [18]. AL strategies must incorporate techniques to address these imbalances, such as:

- Stratified Sampling: Ensuring representation of minority classes in selected batches

- Cost-sensitive Learning: Assigning appropriate misclassification costs to different classes

- Artificial Data Augmentation: Generating synthetic examples of rare classes to balance training data [18]

- Focal Loss Implementation: Using specialized loss functions that focus learning on difficult-to-classify examples [18]

Data quality issues, including experimental noise and measurement errors, present additional challenges. The two-phase AL pipeline demonstrated for plasma exposure prediction shows how AL can effectively sample informative data from noisy datasets, achieving high performance with reduced data requirements [8].

Diagram 2: Active Learning Framework Components and Applications in Drug Discovery

Active learning has emerged as a transformative approach for addressing fundamental challenges in drug discovery, particularly the navigation of vast chemical spaces with limited labeled data. The advantages of AL-guided data selection align exceptionally well with the requirements of modern drug discovery pipelines, enabling significant reductions in experimental costs (up to 99.9% in virtual screening) while accelerating the identification of promising candidates [11].

The applications of AL span the entire drug discovery continuum, from initial target identification and virtual screening through lead optimization and property prediction. Quantitative benchmarks demonstrate that AL methods can discover 60% of synergistic drug pairs with only 10% exploration of combinatorial space [17], achieve accuracy of 0.856 with 30% of training data for plasma exposure prediction [8], and recover 70% of top hits with 0.1% of computational resources in virtual screening [11].

Future developments in AL for drug discovery will likely focus on several key areas: improved integration with advanced ML algorithms, development of more sophisticated batch selection methods that better account for molecular diversity and synthetic accessibility, enhanced uncertainty quantification in deep learning models, and more effective strategies for multi-objective optimization. Additionally, the incorporation of human expert knowledge through interactive AL systems represents a promising direction for combining computational efficiency with medicinal chemistry expertise [18].

As the field continues to evolve, AL is poised to become an increasingly essential component of drug discovery pipelines, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and accelerating the development of novel therapeutics. The methodological foundations and implementation frameworks described in this technical guide provide researchers with the necessary tools to leverage AL in addressing the persistent challenge of navigating vast chemical spaces with limited labeled data.

The process of drug discovery is notoriously complex, costly, and time-consuming, often requiring over a decade and substantial financial investment to bring a single new medicine to market [19]. This inefficiency is compounded by the vastness of chemical space, which is estimated to encompass over 10^60 potential molecules, making the identification of viable drug candidates akin to finding a needle in a haystack [20]. Within this challenging landscape, active learning (AL)—a subfield of artificial intelligence characterized by an iterative feedback process that selects the most informative data points for labeling—has emerged as a powerful strategy to accelerate discovery and reduce costs [3]. By enabling more efficient exploration of the chemical space and minimizing the number of resource-intensive experiments required, AL addresses the core challenges of modern drug discovery: the explosion of the exploration space and the critical limitations of labeled data [3]. This review traces the evolution of AL from its early theoretical foundations to its current status as an integrated component of the drug discovery pipeline, highlighting its methodologies, applications, and future potential.

The Historical Trajectory of Active Learning

The conceptual foundation of active learning has existed for nearly four decades, but its journey into the mainstream of drug discovery has been gradual and marked by key technological shifts [3].

Table 1: Evolution of Active Learning in Drug Discovery

| Era | Key Developments and Paradigms | Typical Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Concepts (Pre-2000s) | - Theoretical formulation of AL algorithms [3].- Introduction into drug discovery (~2 decades ago) [3].- Early tools like QSAR (1960s) and molecular docking (1980s) laid groundwork [19]. | - Limited research applications.- Simple query strategies for QSAR models. | - Incompatibility with the rigid infrastructure of high-throughput screening (HTS) [3].- Limited computational power and data availability. |

| Initial Applications (2000-2010s) | - AL applied to sequential and batch mode sample selection [6].- Focus on "query by committee" and uncertainty sampling [3].- Used with traditional machine learning models (e.g., Support Vector Machines) [3]. | - Virtual screening to prioritize compounds for testing [3].- Predicting compound-target interactions [3]. | - Batch selection was computationally challenging [6].- Not widely applied with advanced deep learning models. |

| Modern Integration (2020s-Present) | - Rise of deep batch AL for neural networks (e.g., COVDROP, COVLAP) [6].- Integration with generative AI and automated laboratory platforms [21] [22].- Frameworks like BAIT and GeneDisco emerge [6]. | - De novo molecular design and optimization [21] [3].- ADMET property prediction and affinity optimization [6].- Multi-parameter optimization in closed-loop systems. | - Need for robust benchmarks and standardized protocols.- Balancing exploration with exploitation in molecular generation. |

The initial application of AL in drug discovery approximately two decades ago was relatively limited, primarily due to an incompatibility between its flexible, iterative infrastructure and the rigid, linear protocols of high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms that dominated the era [3]. Early AL research focused on sequential modes where samples were labeled one at a time. However, the more realistic and cost-effective approach for drug discovery is batch mode, where a set of compounds is selected for testing in each cycle [6]. This presented a significant computational challenge, as it required selecting a set of samples that were collectively informative, rather than just individually optimal, to avoid redundancy [6]. The past decade, however, has witnessed a transformative shift. Advances in automation technology for HTS and dramatic improvements in the accuracy and capability of machine learning algorithms, particularly deep learning, have created an environment where AL can thrive [3]. This has led to the development of sophisticated deep batch AL methods, such as COVDROP and COVLAP, which are specifically designed to work with advanced neural network models, enabling their application to complex property prediction tasks like ADMET and affinity optimization [6].

Core Methodologies: How Active Learning Works in Practice

The Fundamental Active Learning Workflow

The AL process is a dynamic cycle that can be broken down into a series of key steps, which together form a powerful, self-improving system for molecular discovery [3].

Active Learning Cycle

As shown in the workflow above, the process begins with the creation of a predictive model using a small, initial set of labeled training data [3]. This model is then used to screen a much larger pool of unlabeled data. A query strategy is applied to this pool to identify the most "informative" data points based on model-generated hypotheses. Common strategies include selecting samples where the model is most uncertain, or those that are most diverse from the already labeled set [3]. These selected compounds are then presented to an oracle—which in a drug discovery context is typically an experimental assay (e.g., to measure binding affinity) or a high-fidelity computational simulation (e.g., molecular docking or binding free energy calculations) [6] [21]. The newly acquired labels from the oracle are added to the training set, and the model is retrained, thereby enhancing its predictive performance and domain knowledge. This iterative feedback loop continues until a predefined stopping criterion is met, such as the achievement of a target model accuracy or the exhaustion of a experimental budget [3].

Advanced Architectures: Nested AL Cycles for Molecular Generation

Recent research has pushed the boundaries of AL beyond simple prediction towards generative design. One advanced architecture integrates a generative model (GM), specifically a Variational Autoencoder (VAE), within a framework of two nested AL cycles [21]. This sophisticated workflow is designed to generate novel, drug-like molecules with high predicted affinity for a specific target.

Nested AL Cycles for Molecular Generation

In this integrated GM-AL workflow, the VAE is first trained on general and target-specific molecular data to learn the principles of viable chemistry and initial target engagement [21]. The model then generates new molecules. In the inner AL cycle, these molecules are evaluated by a chemoinformatics oracle that filters for drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility (SA), and novelty compared to known molecules [21]. Molecules passing this filter are used to fine-tune the VAE, pushing it to generate compounds with more desirable properties. After a set number of inner cycles, an outer AL cycle is triggered. Here, the accumulated molecules are evaluated by an affinity oracle—typically physics-based molecular modeling like docking simulations—to predict their binding strength to the target [21]. High-scoring molecules are added to a permanent set used for VAE fine-tuning, directly steering the generative process towards high-affinity candidates. This nested structure allows for simultaneous optimization of multiple objectives, culminating in the selection of top candidates for more rigorous validation, such as absolute binding free energy simulations and ultimately, synthesis and biological testing [21].

Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

A Representative Protocol: Deep Batch Active Learning for ADMET Optimization

A landmark study demonstrating modern AL application developed two novel batch selection methods, COVDROP and COVLAP, for optimizing ADMET and affinity properties [6]. The following provides a detailed methodology.

Objective: To significantly reduce the number of experiments needed to build accurate predictive models for key drug properties like solubility, permeability, and lipophilicity [6].

Experimental Workflow:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a relevant dataset (e.g., 9,982 compounds for aqueous solubility [6]) and split it into an initial small training set and a large unlabeled pool.

- Model Setup: A graph neural network model is initialized and trained on the initial labeled set.

- Uncertainty Estimation: For the unlabeled pool, model uncertainty is quantified using innovative sampling strategies:

- Batch Selection: A covariance matrix is computed between the predictions on the unlabeled samples. The method then uses a greedy iterative approach to select a batch (e.g., 30 molecules) where the submatrix of the covariance has a maximal determinant. This approach maximizes the joint entropy (information content) of the batch, ensuring both high uncertainty (high variance) and high diversity (low covariance, i.e., non-redundant samples) [6].

- Iterative Loop: The selected batch is "labeled" (in a retrospective study, the values are retrieved from the dataset; in a real-world scenario, they would be determined by experiment). The model is then retrained on the updated, enlarged training set.

- Evaluation: Model performance (e.g., Root Mean Square Error - RMSE) is tracked against the number of cycles or total samples labeled. The efficiency of the AL method is benchmarked against other selection strategies (e.g., random selection, k-means, BAIT) [6].

Key Findings: The study demonstrated that these AL methods could achieve the same model performance with far fewer experiments compared to random selection or older methods, leading to "significant potential saving in the number of experiments needed" [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AL-Driven Discovery

| Item / Solution | Function in AL Workflow | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Public & Proprietary Bioactivity Datasets | Serves as the foundational data for initial model training and as the "oracle" in retrospective validation. | ChEMBL, cell permeability datasets [6], aqueous solubility datasets [6], internal corporate compound libraries. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Provides the programming environment to build, train, and deploy the predictive models used in the AL loop. | TensorFlow, PyTorch, DeepChem [23] [6]. |

| Cheminformatics Tools & Oracle | Validates chemical structures, calculates molecular descriptors, and filters for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility (SA) in generative AL cycles [21]. | RDKit, SA score predictors, filters for Lipinski's Rule of 5. |

| Molecular Modeling & Affinity Oracle | Provides physics-based evaluation of generated or selected compounds, predicting binding affinity and mode. Replaces or prioritizes experimental assays [21]. | Molecular docking software (AutoDock, GOLD), molecular dynamics simulations (GROMACS [19], CHARMM [19]), free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations. |

| Automated Laboratory Equipment | Acts as the physical "oracle" by experimentally testing the batches of compounds selected by the AL algorithm, closing the loop in fully automated systems. | High-throughput synthesizers, automated liquid handlers, plate readers. |

Current Applications and Impact on the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Active learning has moved from a niche technique to a valuable tool across multiple stages of the drug discovery pipeline. Its ability to make efficient decisions with limited data makes it particularly suited to the field's most pressing challenges.

Virtual Screening and Compound-Target Interaction (CTI) Prediction: AL compensates for the shortcomings of both structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening methods. By iteratively selecting the most informative compounds for docking or testing, it achieves higher hit rates than random screening and helps explore broader chemical spaces without being constrained by a single starting point [3]. For CTI prediction, AL strategies help select which compound-target pairs to test experimentally, efficiently building accurate predictive models and uncovering novel interactions [3].

De Novo Molecular Generation and Optimization: As detailed in the nested AL architecture, AL is now deeply integrated with generative AI. It guides the generation process towards molecules that are not only novel and synthetically accessible but also exhibit strong target engagement [21]. This application was successfully demonstrated in campaigns for CDK2 and KRAS targets, where the AL-guided GM workflow generated novel scaffolds, leading to the synthesis of several active compounds, including one with nanomolar potency for CDK2 [21].

Molecular Property Prediction (ADMET): Optimizing the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile of a lead compound is a critical and resource-intensive phase. Deep batch AL methods have been directly applied to build accurate predictive models for properties like solubility, permeability, and lipophilicity with far fewer virtual or experimental assays, significantly accelerating lead optimization [6].

The impact of AL is quantifiable. Studies have shown that in some optimization tasks, such as discovering synergistic drug combinations, AL can achieve 5–10 times higher hit rates than random selection [3]. Furthermore, in ADMET and affinity prediction, the implementation of modern AL algorithms has led to a drastic reduction in the number of experiments needed to reach a desired model performance, translating directly into saved time and resources [6].

The evolution of active learning from an early conceptual framework to a deeply integrated component of modern drug discovery marks a significant paradigm shift. By embracing an iterative, data-centric approach, AL directly confronts the core inefficiencies of the traditional linear pipeline. Its power lies in its fundamental alignment with the needs of the field: to navigate an exponentially growing chemical space and to make the most of every piece of costly experimental data [3]. The integration of AL with other advanced technologies—particularly generative AI, automated synthesis, and high-throughput experimentation—is paving the way for fully automated, closed-loop discovery systems that can learn and optimize with minimal human intervention [21] [22].

Despite its promising trajectory, the widespread adoption of AL faces several challenges. There is a need for more robust benchmarking standards and accessible, user-friendly tools to facilitate its use by medicinal chemists and biologists, not just computational experts [3]. Furthermore, developing AL strategies that can seamlessly handle multi-objective optimization—simultaneously balancing potency, selectivity, ADMET, and synthetic feasibility—remains an area of active research [3]. As these hurdles are overcome, and with the continuous growth of high-quality biological and chemical data, active learning is poised to become an indispensable pillar of pharmaceutical R&D, fundamentally accelerating the delivery of new therapeutics to patients.

Why Now? The Convergence of Automation, Improved ML Accuracy, and High-Throughput Screening

The field of drug discovery is currently experiencing a paradigm shift, driven by the simultaneous maturation of three critical technologies: advanced automation, more reliable machine learning (ML) models, and sophisticated high-throughput screening (HTS). This convergence marks a transition from isolated technological demonstrations to integrated, practical workflows that are actively compressing drug development timelines and enhancing the quality of therapeutic candidates. Framed within the broader context of active learning in drug discovery, this whitepaper examines the technical advances in each domain, details the experimental protocols enabling their integration, and presents quantitative data illustrating their collective impact on modern pharmaceutical research and development.

The traditional drug discovery process is notoriously lengthy, costly, and prone to failure, often taking over a decade and costing billions of dollars to bring a single new drug to market [24] [25]. For years, automation, machine learning, and screening technologies have been developing on parallel tracks. The pivotal change occurring now is their convergence into a cohesive, iterative cycle that closely aligns with the principles of active learning. This framework involves a closed-loop system where computational models propose experiments, automated platforms execute them and generate high-quality data, and the results are used to refine the models, thereby accelerating the entire discovery pipeline [14] [12]. The atmosphere at recent industry conferences, such as ELRIG's Drug Discovery 2025, has been notably focused on this practical integration, moving beyond grandiose claims to tangible progress in creating tools that help scientists work smarter [14].

The Pillars of Convergence

The Rise of Practical and Accessible Automation

Automation in the lab has evolved from bulky, inflexible systems to modular, user-centric tools designed for seamless integration into existing workflows. The current focus is on usability and reproducibility, empowering scientists rather than replacing them.

Key Advancements:

- Ergonomic and Accessible Design: New automation tools are built with the scientist in mind. For instance, Eppendorf's Research 3 neo pipette was developed from extensive surveys of working scientists, featuring a lighter frame, shorter travel distance, and a larger plunger to reduce physical strain over long periods [14]. The goal is to make automation confidently usable, saving time for analysis and thinking.

- Modular and Scalable Systems: The automation landscape is branching into two complementary paths: simple, accessible benchtop systems for widespread use (e.g., Tecan's Veya liquid handler) and large, unattended multi-robot workflows for maximum throughput [14]. This flexibility allows labs to scale their automation capabilities according to their needs.

- Biology-First Automation: Automation is increasingly applied to complex biological models to enhance their relevance and reproducibility. Companies like mo:re have developed fully automated platforms, such as the MO:BOT, which standardizes 3D cell culture by automating seeding, media exchange, and quality control. This produces consistent, human-derived tissue models that provide more predictive safety and efficacy data, reducing the reliance on animal models [14].

Overcoming the Machine Learning Generalizability Gap

A significant historical roadblock for ML in drug discovery has been its unpredictable failure when encountering chemical structures outside its training data. Recent research has directly addressed this generalizability gap, paving the way for more reliable and trustworthy AI tools.

Key Advancements:

- Task-Specific Model Architectures: Instead of learning from entire 3D structures of proteins and drug molecules, which can lead to learning spurious structural shortcuts, new models are intentionally restricted. They learn only from a representation of the protein-ligand interaction space, which captures the distance-dependent physicochemical interactions between atom pairs. This forces the model to learn the transferable principles of molecular binding [26].

- Rigorous and Realistic Benchmarking: The development of more stringent evaluation protocols is critical. To simulate real-world scenarios, models are now tested by training them on a set of protein families and then evaluating them on entirely excluded superfamilies. This practice reveals that contemporary models which perform well on standard benchmarks can show a significant performance drop when faced with novel protein families, highlighting the need for these more rigorous validation methods [26].

- Transparent and Explainable AI: As AI is integrated into critical decision-making, transparency becomes paramount. Companies like Sonrai Analytics emphasize completely open workflows within trusted research environments, allowing clients to verify every input and output. This builds confidence with both partners and regulators, which is essential for clinical adoption [14].

The Evolution of High-Throughput Screening

HTS has long been a staple of early drug discovery for rapidly testing thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds. Its evolution into ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) and its integration with AI-driven data analysis have dramatically increased its power and value.

Key Advancements:

- Ultra-High-Throughput and Miniaturization: uHTS can achieve throughputs of over 300,000 compounds per day, a significant leap from traditional HTS. This is enabled by advances in microfluidics and the use of high-density microwell plates (e.g., 1536-well formats) with volumes as low as 1–2 µL [27].

- Advanced Detection Technologies: The move beyond simple fluorescence-based assays to more sophisticated methods like mass spectrometry (MS) and differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) provides richer data and helps reduce false positives resulting from assay interference [27].

- AI-Powered Data Triage: The massive datasets generated by HTS/uHTS are now managed using machine learning models trained on historical HTS data. These models help rank output into categories of success probability, effectively identifying and filtering false positives caused by chemical reactivity, autofluorescence, or colloidal aggregation [27].

Quantitative Analysis of Technological Impact

| Attribute | HTS | uHTS | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (assays/day) | < 100,000 | >300,000 | uHTS offers a significant speed advantage. |

| Complexity & Cost | Lower | Significantly Greater | uHTS requires more sophisticated instrumentation and infrastructure. |

| Data Analysis Needs | High | Very High | uHTS necessitates faster processing, often requiring AI. |

| Ability to Monitor Multiple Analytes | Limited | Enhanced | uHTS benefits from miniaturized, multiplexed sensor systems. |

| False Positive/Negative Bias | Present | Present | Sophisticated cheminformatics and AI triage are required for both. |

| Segment | Leading Category (Market Share) | High-Growth Category (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|

| Application Stage | Lead Optimization (~30%) | Clinical Trial Design & Recruitment |

| Algorithm Type | Supervised Learning (~40%) | Deep Learning |

| Deployment Mode | Cloud-Based (~70%) | Hybrid Deployment |

| Therapeutic Area | Oncology (~45%) | Neurological Disorders |

| End User | Pharmaceutical Companies (~50%) | AI-Focused Startups |

| Region | North America (48%) | Asia Pacific |

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Workflows

The true power of the current convergence is realized when these pillars are combined into a single, active learning-driven workflow. The following protocols detail how this is achieved in practice.

Protocol: AI-Driven de novo Molecular Design and Validation

This protocol, exemplified by companies like Schrödinger and Exscientia, leverages ML and physics-based models to rapidly explore vast chemical spaces [12] [28].

1. Problem Formulation & Target Profiling:

- Define the target product profile (TPP), including potency, selectivity, ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties, and the structure of the target protein [12] [25].

2. Generative Molecular Design:

- Use generative models (e.g., generative adversarial networks, reinforcement learning) to create novel molecular structures predicted to satisfy the TPP.

- Example: Schrödinger's large-scale de novo design workflow explored 23 billion molecular designs for an EGFR inhibitor project in just six days, identifying four novel scaffolds [28].

3. In Silico Affinity and Selectivity Screening:

- Employ rigorous ML and physics-based scoring functions to rank generated compounds.

- Methodology: Use a generalizable deep learning framework focused on the protein-ligand interaction space to predict binding affinity, avoiding over-reliance on training data structural biases [26].

- Apply free energy perturbation (FEP+) calculations, potentially optimized by active learning (e.g., FEP+ Protocol Builder), for highly accurate binding affinity predictions [28].

4. Automated Synthesis and Testing (Make-Test):

- Transfer top-ranking compound designs to an automated synthesis platform.

- Example: Exscientia's "AutomationStudio" uses state-of-the-art robotics to synthesize and test candidate molecules, closing the design-make-test-learn loop [12].

- Validate predictions using automated, miniaturized biochemical or cell-based assays (see Section 4.2).

5. Model Refinement:

- Feed the experimental results from the automated testing back into the ML models to refine their predictions, initiating the next, more informed design cycle [12].

Protocol: High-Content Screening with AI-Driven Analysis

This protocol combines automated biology, high-content imaging, and AI to extract complex, phenotypic information from cell-based assays.

1. Development of Biologically Relevant Assay Systems:

- Prepare standardized, biomimetic assay platforms. This can involve protein micropatterning to create consistent cellular microenvironments or the use of 3D cell cultures and organoids [29].

- Automation: Use platforms like the MO:BOT to automate the seeding and maintenance of 3D organoids, ensuring reproducibility and rejecting sub-standard cultures before screening [14].

2. Automated Staining and Imaging:

- Use robotic liquid handlers to process assays in microplates (96- to 1536-well format).

- Acquire high-content images using automated microscopy systems.

3. AI-Powered Image and Data Analysis:

- Process the multiplexed imaging data using foundation models trained on thousands of histopathology and multiplex imaging slides.

- Methodology: Use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or similar deep learning architectures to identify complex morphological features and biomarkers that are not apparent to the human eye [14] [24].

- Integrate the imaging data with other omics datasets (e.g., genomic, proteomic) within a single analytical framework to uncover links between molecular features and disease mechanisms [14].

4. Insight Generation and Validation:

- The AI analysis generates directly interpretable biological insights, such as new biomarker candidates or hypotheses on disease mechanisms, which are then forwarded for further validation in downstream experiments [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Convergent Discovery

| Item | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handlers (e.g., Tecan Veya) | Provide precise, nanoliter-scale dispensing for assay setup and reagent addition in HTS/uHTS, ensuring robustness and reproducibility [14] [27]. |

| 3D Cell Culture Systems (e.g., mo:re MO:BOT) | Generate human-relevant tissue models in a standardized, automated fashion, improving the translational predictive power of screening data [14]. |

| Cartridge-Based Protein Expression (e.g., Nuclera eProtein) | Automate protein production from DNA to purified protein in under 48 hours, providing high-quality targets for screening and structural studies [14]. |

| Validated Assay Kits (e.g., Agilent SureSelect) | Provide robust, off-the-shelf biochemistry (e.g., for library prep) that is optimized for integration with automated platforms, ensuring data reliability [14]. |

| Cloud-Based Data Platforms (e.g., Cenevo/Labguru) | Unite sample management, experimental data, and instrument outputs, creating structured, AI-ready data lakes that are essential for model training and insight generation [14]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram synthesizes the components discussed above into a single, integrated active learning cycle for modern drug discovery.

Diagram 1: Integrated Active Learning Cycle in Drug Discovery

The question "Why Now?" is answered by the simultaneous arrival of a critical mass of maturity in automation, machine learning, and screening technologies. This is not a hypothetical future but a present-day reality, as evidenced by AI-designed molecules entering clinical trials and fully automated discovery platforms coming online. The convergence is creating a new, more efficient paradigm grounded in the principles of active learning, where predictive models and automated experiments exist in a tight, iterative loop. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this integrated landscape is no longer optional but essential for driving the next generation of therapeutic innovation. The tools are now here—ergonomic, reliable, and connected—to empower scientists to work smarter, explore broader chemical and biological spaces, and ultimately, translate discoveries to patients faster.

AL in Action: Key Methodologies and Transformative Applications Across the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Virtual screening and hit identification represent the foundational stage in the modern drug discovery pipeline, where vast chemical libraries are computationally interrogated to find promising starting points for drug development [30]. This process serves as the first major decision gate, narrowing millions or even billions of potential compounds to a manageable set of experimentally validated "hits" – small molecules with confirmed, reproducible activity against a biological target [30]. The acceleration of this phase through advanced computational methods, particularly artificial intelligence and active learning, has dramatically transformed early drug discovery from a labor-intensive, time-consuming process to a precision-guided, efficient workflow [24].