Active Learning Molecular Dynamics: A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Materials Design

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of active learning (AL) frameworks integrated with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a cutting-edge approach that is transforming computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Active Learning Molecular Dynamics: A Revolutionary Framework for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Materials Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of active learning (AL) frameworks integrated with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a cutting-edge approach that is transforming computational chemistry and drug discovery. We cover the foundational principles of how AL iteratively improves machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) by selectively querying the most informative data, thereby overcoming the prohibitive cost of exhaustive quantum mechanical calculations. The article delves into diverse methodological implementations, from enhancing infrared spectra predictions to de novo drug design, and offers practical guidance on troubleshooting and optimizing AL-MD workflows. Finally, we present rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses that demonstrate the significant accuracy gains and computational efficiency of AL-enhanced simulations over traditional methods, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to implement these powerful techniques in their own work.

Demystifying Active Learning MD: Core Principles and the Quest for Data Efficiency

Traditional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are powerful tools for exploring atomic-scale phenomena but face a critical data bottleneck. The process of generating sufficient reference data, typically from expensive ab initio calculations, to train accurate machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) is computationally prohibitive and often wasteful. This article details how active learning (AL) strategies are solving this fundamental challenge by making data generation for MD simulations intelligent, efficient, and targeted. Framed within a broader thesis on active learning MD simulation frameworks, this note provides the quantitative evidence, standardized protocols, and essential toolkits for researchers to adopt these transformative methods.

The Quantitative Advantage of Active Learning

Active learning frameworks achieve orders-of-magnitude improvements in computational efficiency by strategically selecting the most informative data points for reference calculations, thereby avoiding redundant sampling.

Table 1: Quantitative Efficiency Gains from Active Learning Implementations

| Application / System | Key AL Efficiency Metric | Traditional Approach Comparison | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Coronavirus Inhibitor Identification | Experimental candidates reduced to <20; Computational cost cut by ~29-fold. | Brute-force virtual screening is "very wasteful." | [1] |

| Small-Cell MLIP Training (K & NaK) | Cost savings up to 100x; Training required as little as 120 core-hours. | Large-cell (54-atom) training is far more computationally expensive. | [2] |

| Coarse-Grained Protein Dynamics (Chignolin) | 33.05% improvement in the W1 metric in TICA space. | Models degrade when simulations reach under-sampled conformations. | [3] [4] |

| Infrared Spectra Prediction (PALIRS) | Accurate IR spectra at a fraction of the cost of AIMD. | Ab-initio MD is computationally expensive, limiting tractable system size. | [5] |

Table 2: Core Components of an AL-MD Framework for Drug Discovery [1]

| Framework Component | Description | Role in Overcoming Data Bottleneck |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Ensemble | 20 snapshots from a ~100 µs MD simulation of the target protein. | Accounts for protein flexibility and increases likelihood of docking to binding-competent structures. |

| Target-Specific Score (h-score) | An empirical score rewarding occlusion of the active site and key feature distances. | More accurately models inhibition than generic docking scores, reducing false positives/negatives. |

| Active Learning Cycle | Iterative candidate ranking and selection from a chemical library. | Drastically reduces the number of compounds requiring computational and experimental testing. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines specific methodologies for implementing active learning in molecular simulations, providing a practical guide for researchers.

Protocol: Simple (MD) Active Learning with M3GNet

This protocol, based on the Amsterdam Modeling Suite, details how to fine-tune a universal potential for a specific system [6].

- Initial Setup: In AMSinput, select the

MD Active Learningpanel. The five required inputs are: initial structure, reference engine settings, MD settings, ML model settings, and active learning settings. - Initial Structure: Import a reasonable initial structure (e.g., via SMILES string

OCC=O). While geometry optimization is not mandatory, initial forces should not be excessively high to prevent uncontrolled temperature rises. - Reference Engine: In the

Enginedropdown, select a reference engine (e.g.,Force Field→UFFfor speed, orADF/DFTBfor higher accuracy). It is critical to verify the engine's reliability for the system beforehand. - Molecular Dynamics Settings: Configure the MD parameters. Set

TasktoMolecularDynamicswithNumber of steps = 10000and aTime step = 0.5 fs. Configure the thermostat (e.g.,NHCatTemperature = 300 Kwith aDamping constant = 10-200 fs). - Machine Learning Model: Set the

Machine learning backendtoM3GNet. For transfer learning, setModeltoUniversal PotentialandMax epochs = 200. ACommittee sizeof 1 is sufficient when fine-tuning. - Active Learning Settings:

- Step Sequence: Set

Step sequence type = GeometricwithStart = 10andNum steps = 5. This divides the MD into 5 segments, with the first being 10 frames. - Success Criteria: Use the default thresholds for energy and force errors between the ML model and reference engine. If the error is too high, the model retrains.

- Reasonable Simulation Criteria: Set safety limits, such as a maximum allowed temperature and a minimum interatomic distance, to discard unphysical frames.

- Step Sequence: Set

- Execution and Analysis: Run the job and monitor the

.logfile for active learning progress, retraining events, and final timings. The production-ready MLIP is saved and can be used for subsequent simulations.

Protocol: Active Learning for Reactive MLIPs with Metadynamics

This protocol combines AL with metadynamics to efficiently sample transition states and reaction pathways with minimal initial data [7].

- Objective: To train an accurate MLIP for chemical reactions, requiring sampling of high-energy transition states, using only 5-10 initial configurations and no prior knowledge of the transition state.

- Workflow Integration: The fully automated workflow iterates between:

- MLIP-Driven Exploration: Running MD simulations using the current MLIP.

- Biased Sampling with Metadynamics: Using well-tempered metadynamics to push the simulation into new, high-energy regions of the potential energy surface.

- Active Learning Query: Identifying configurations with high predictive uncertainty or high energy.

- Oracle Calculation & Retraining: Performing ab initio calculations on the queried configurations and adding them to the training set to refine the MLIP.

- Key Outcome: This strategy generates accurate and stable MLIPs for complex reactions (e.g., glycosylation in explicit solvent) by ensuring the training data encompasses both metastable states and the critical transitions between them.

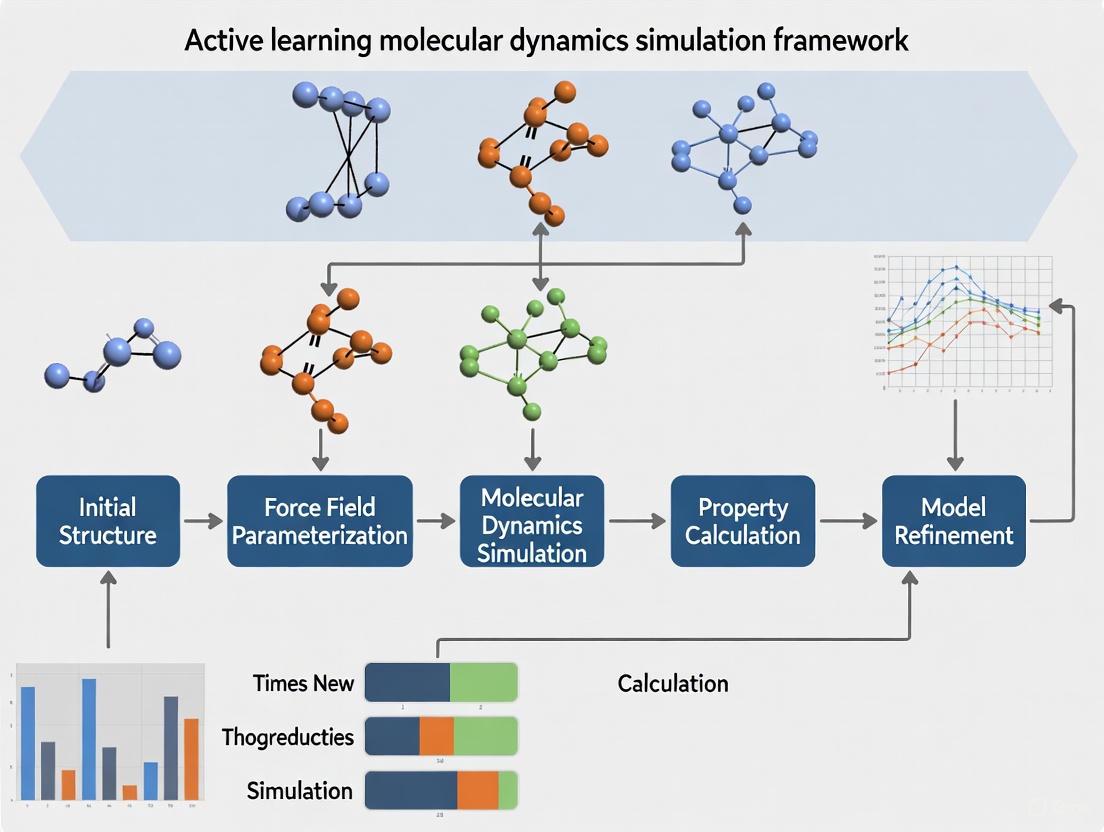

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical structure of standard and advanced active learning workflows for molecular dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing an active learning framework for molecular dynamics requires a combination of software, computational tools, and strategic methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Active Learning MD

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet Universal Potential [6] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | A pre-trained, general-purpose MLIP that serves as a foundation for transfer learning via active learning. | Fine-tuning for a specific organic molecule in the "Simple (MD) Active Learning" protocol. |

| MACE [5] | MLIP Architecture (Neural Network) | A highly accurate neural network potential; an ensemble of MACE models can be used for uncertainty quantification. | Predicting IR spectra in the PALIRS framework, where uncertainty estimation drives active learning. |

| Moment Tensor Potential (MTP) [8] | MLIP Architecture | An efficient potential that uses a tensor formalism to describe atomic environments; well-suited for active learning. | Modeling complex amorphous materials like Sb₂S₃, achieving high R² values for DFT-level properties. |

| CGSchNet [3] [4] | Coarse-Grained (CG) Neural Network Potential | A graph neural network that learns a CG potential from all-atom data, accelerating biomolecular simulations. | Exploring the conformational landscape of the Chignolin protein with a 33% improvement in accuracy. |

| Metadynamics [7] | Enhanced Sampling Method | Accelerates the exploration of free energy surfaces and rare events, such as chemical reactions. | Integrated with active learning to automatically discover and sample transition states for reactive MLIPs. |

| Receptor Ensemble [1] | Computational Strategy | A collection of protein snapshots from MD simulations used for docking, accounting for flexibility. | Enabling the identification of broad coronavirus inhibitors by docking to multiple binding-competent states. |

| Small-Cell Training Set [2] | Data Generation Strategy | A training set composed of configurations from DFT calculations on very small unit cells (1-8 atoms). | Achieving 100x cost savings for training MLIPs for potassium and sodium-potassium systems. |

The integration of active learning into molecular dynamics simulations represents a paradigm shift, directly addressing the critical data bottleneck that has long constrained the field. By moving from exhaustive, brute-force data generation to intelligent, targeted querying, these frameworks achieve unprecedented computational efficiencies, as demonstrated by the order-of-magnitude cost reductions and improved hit rates in drug discovery. The standardized protocols and toolkits detailed herein provide a clear roadmap for researchers to implement these powerful methods. As a core component of a modern molecular simulation thesis, active learning is not merely an optional optimization but a foundational capability for enabling accurate, large-scale, and predictive atomic-scale modeling across chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

The exploration of potential energy surfaces (PES) is fundamental to understanding molecular dynamics, chemical reaction pathways, and material properties at the atomistic scale. A PES describes the potential energy of a system, especially a collection of atoms, in terms of certain parameters, normally the positions of the atoms [9]. Traditionally, constructing accurate PES models required exhaustive quantum mechanical calculations across configuration space, presenting a prohibitive computational bottleneck for complex systems. Active learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm that iteratively extends training data to enhance model performance while minimizing data acquisition costs [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for developing machine-learned potentials (MLPs), which enable molecular dynamics simulations with quantum mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [11] [12]. By autonomously identifying the most informative configurations for quantum mechanical labeling, active learning workflows can efficiently build comprehensive datasets that capture the complex topography of multidimensional PES, including rare events and transition states that are critical for understanding chemical reactivity [12] [10].

Key Frameworks and Performance Benchmarks

Quantitative Performance of Active Learning Approaches

Recent implementations of active learning frameworks have demonstrated significant acceleration in mapping potential energy surfaces across diverse chemical systems. The following table summarizes key performance metrics reported for various frameworks and applications:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Active Learning Frameworks for PES Exploration

| Framework | System Studied | Key Performance Metrics | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| autoplex [11] | Elemental Silicon (allotropes) | Target accuracy (0.01 eV/atom) achieved with ≈500 DFT single-point evaluations for diamond- and β-tin-type structures | Fully automated workflow requiring minimal human intervention |

| autoplex [11] | TiO₂ polymorphs | Prediction error reduced to few tens of meV/atom for rutile, anatase, and TiO₂-B structures | More complex polymorphs require additional iterations (thousands of evaluations) |

| autoplex [11] | Binary Ti-O system | Accurate description of multiple stoichiometries (Ti₂O₃, TiO, Ti₂O) achieved with expanded training | Requires broader configuration sampling but similar workflow to single-composition systems |

| AL-accelerated AIMD [12] | Pericyclic reactions | 2000x acceleration of ab initio molecular dynamics vs conventional DFT-MD | Enables treatment of dynamical effects with same cost as transition state theory approaches |

| CGSchNet AL [4] | Chignolin protein | 33.05% improvement in Wasserstein-1 metric in TICA space | Preserves coarse-grained efficiency while correcting model at identified coverage gaps |

The Active Learning Loop Protocol

The following section provides a detailed experimental protocol for implementing an active learning loop for PES exploration, synthesizing methodologies from multiple frameworks.

Initial Dataset Generation and Model Pretraining

Procedure:

- System Definition: Define the chemical system of interest, including elemental composition and relevant phase space (e.g., gaseous, condensed phase, interfaces).

- Initial Configuration Sampling: Generate an initial set of diverse atomic configurations using methods such as Random Structure Searching (RSS) [11], normal mode sampling, or high-temperature molecular dynamics. For the autoplex framework, initial RSS generates structures with random atomic positions within defined composition constraints [11].

- Reference Calculations: Perform ab initio calculations (typically Density Functional Theory) on the initial configurations to obtain reference energies and forces. The autoplex framework utilizes approximately 100-200 initial DFT single-point evaluations to bootstrap the process [11].

- Initial MLP Training: Train an initial machine-learned potential (such as Gaussian Approximation Potential or neural network potential) on the reference data. The model should include uncertainty quantification capabilities, such as committee models or built-in uncertainty metrics [10].

Iterative Active Learning Phase

Procedure:

- Configuration Exploration: Run molecular dynamics simulations or other sampling methods (e.g., metadynamics, replica exchange) using the current MLP to explore new regions of configuration space.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Monitor the uncertainty of MLP predictions during exploration. The controller kernel in PAL implements this centrally, calculating standard deviations from committee models or other uncertainty metrics [10].

- Informative Sample Selection: When uncertainty exceeds a predefined threshold, flag configurations for ab initio labeling. The PAL framework allows configurable "patience" parameters, permitting trajectories to continue in uncertain regions for a set number of steps before restarting [10].

- Oracle Consultation: Submit selected configurations for ab initio calculation (the "oracle") to obtain accurate energy and force labels. The PAL oracle kernel manages multiple concurrent DFT calculations efficiently [10].

- Dataset Augmentation and Retraining: Add the newly labeled data to the training set and retrain the MLP. In parallel frameworks like PAL, the prediction kernel updates periodically with weights from the training kernel to minimize disruption to ongoing simulations [10].

- Convergence Checking: Evaluate model performance on held-out test sets or monitor error metrics across iterations. Continue the cycle until target accuracy is achieved across relevant regions of the PES.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the parallelized active learning workflow implemented in frameworks like PAL, showing the interaction between different computational components:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential software tools and computational methods used in active learning for potential energy surfaces:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Active Learning on PES

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Frameworks | PAL (Parallel Active Learning) [10], autoplex [11] | Orchestrates the complete AL workflow, manages parallelism, and coordinates between components |

| Machine-Learned Potentials | Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) [11], SchNet [10] [4], NequIP, Allegro, MACE [10] | ML models that predict energies and forces from atomic configurations; core of the prediction kernel |

| Quantum Chemical Oracles | Density Functional Theory codes (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Provide reference-quality energy and force labels for training data via electronic structure calculations |

| Configuration Generators | Molecular Dynamics engines, Random Structure Searching (RSS) [11], enhanced sampling methods | Explore the configuration space and propose new structures for labeling |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Committee models, built-in uncertainty metrics [10] | Identify regions of configuration space where MLP predictions are unreliable |

| Δ-Machine Learning | PIP-NN with analytical baselines [13] | Cost-effective approach to create high-level PES from low-level data with corrections |

Advanced Application Notes

Protocol for Reactive Energy Surface Exploration

For studying chemical reactions with complex bifurcating potential energy surfaces, the following specialized protocol has been demonstrated effective [12]:

Procedure:

- Reaction Coordinate Identification: Identify 2-3 key reaction coordinates describing bond formation/cleavage using preliminary calculations or chemical intuition.

- High-Throughput Transition State Sampling: Use the neural nudged-elastic band method or similar approaches to locate multiple transition states and reaction pathways.

- Targeted Active Learning: Focus AL sampling around identified transition states and potential energy minima, with particular attention to regions where dynamical effects may dominate.

- AIMD Validation: Run extensive ab initio molecular dynamics using the trained MLP to validate reaction mechanisms and identify potential bifurcations.

- Solvation Effects: For condensed-phase reactions, employ QM/MM approaches or implicit solvation models to generate the reference data, ensuring the PES includes solvent effects.

Protocol for Multi-Component Systems

Exploring complex binary and ternary systems requires modifications to the standard AL loop [11]:

Procedure:

- Composition Space Definition: Define the range of stoichiometries to be included in the exploration phase.

- Biased RSS: Implement composition-biased random structure searching to ensure adequate sampling across different stoichiometric ratios.

- Stoichiometry-Aware Uncertainty: Extend uncertainty quantification to include composition space, not just configuration space.

- Transfer Learning: Leverage pre-trained elemental models or use Δ-machine learning approaches to accelerate convergence [13].

- Phase Space Validation: Explicitly validate the model on known polymorphs across different compositions to ensure balanced performance.

The implementation of these protocols has been shown to successfully map complex PES landscapes, from elemental systems like silicon allotropes to binary metal oxides like TiO₂ and complex biomolecular systems, achieving quantum mechanical accuracy with dramatically reduced computational cost [11] [4] [12].

Uncertainty Quantification, Acquisition Strategies, and Oracles

Active Learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm for developing reliable Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and conducting efficient molecular simulations. By iteratively selecting the most informative data for labeling, AL minimizes the number of expensive quantum mechanical calculations while maximizing model accuracy and robustness across configurational space. This application note details the core components—Uncertainty Quantification, Acquisition Strategies, and Oracles—within an AL-driven Molecular Dynamics (MD) framework, providing structured protocols and resources for researchers in computational chemistry and drug development.

Uncertainty Quantification in Machine-Learned Potentials

Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) provides critical estimates of the reliability of MLIP predictions, serving as the primary trigger for data acquisition within the AL cycle. Accurate UQ is essential for identifying extrapolative regions and rare events, ensuring the generation of uniformly accurate potentials.

Methods for Uncertainty Quantification

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Uncertainty Quantification Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble (Query-by-Committee) | Variance in predictions from multiple models with different initializations or data splits [14] | High (proportional to number of models) | Robust performance, high correlation with error [14] | Conformational sampling of glycine and proton transfer in acetylacetone [14] |

| Sparse Gaussian Process (SGP) | Bayesian inference using representative atomic environments from training set [15] | Moderate (scales with sparse set size) | Principled Bayesian uncertainty, mapping to constant-cost models possible [15] | Phase transformations in SiC [15] |

| Gradient-Based Uncertainty | Sensitivity of model output to parameter changes [16] | Low (ensemble-free) | Computational efficiency, comparable performance to ensembles [16] | Exploration of alanine dipeptide and MIL-53(Al) [16] |

| Latent Distance Metrics | Distance to training set in model's latent representation [17] | Low | No ensembles required, identifies novel configurations [17] | Active learning benchmarks across materials systems [17] |

Uncertainty Calibration with Conformal Prediction

Raw uncertainty estimates from MLIPs are often poorly calibrated, frequently underestimating actual errors and potentially leading to exploration of unphysical configurations [16]. Conformal Prediction (CP) provides a statistical framework for calibrating these uncertainties to ensure they maintain valid probabilistic interpretations.

The CP procedure utilizes a calibration set to compute a rescaling factor that aligns predicted uncertainties with actual errors [16]. For a chosen confidence level (1 - \alpha), CP ensures that the probability of underestimating the error is at most (\alpha) on data drawn from the same distribution as the calibration set. This calibration is particularly crucial for atomic force uncertainties, as miscalibrated forces can cause MD simulations to explore unphysical regions with extremely large errors, potentially causing convergence issues in reference calculations [16].

Table 2: Uncertainty Calibration Performance for MIL-53(Al) at 600K [16]

| Uncertainty Type | Calibration Confidence (1-α) | Correlation with Max Force RMSE | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Based | 0.5 (Lower) | Moderate | Transparent visualization |

| Gradient-Based | 0.95 (Higher) | Strong | Opaque, better calibrated |

| Ensemble-Based | 0.5 (Lower) | Moderate | Transparent visualization |

| Ensemble-Based | 0.95 (Higher) | Strong | Opaque, better calibrated |

Protocol: Implementing Conformal Prediction for Uncertainty Calibration

Objective: Calibrate force uncertainties to prevent exploration of unphysical regions during AL-MD simulations.

Materials:

- Pre-trained MLIP (any architecture with uncertainty estimation capability)

- Calibration set of 100-500 diverse configurations with reference DFT forces

- Test set for validation

- Python libraries: numpy, scikit-learn

Procedure:

- Generate Uncertainty Predictions: For each atomic configuration (i) in the calibration set, compute the maximum atom-based uncertainty (u_i) using your chosen UQ method (ensemble, gradient-based, etc.)

- Calculate Force Errors: For each configuration (i), compute the actual maximum atomic force RMSE: [ \text{max RMSE}i = \max\limits{j} \sqrt{\frac{1}{3}\sum{k=1}^{3}(\Delta F{j,k})^{2}} ] where (\Delta F_{j,k}) is the force error for atom (j) in direction (k) [16]

- Compute Scaling Factor: Calculate the (\alpha)-quantile (q{\alpha}) of the ratios ({\text{max RMSE}i / u_i}) across the calibration set

- Apply Calibration: Multiply all future uncertainty predictions by (q_{\alpha}) to obtain calibrated uncertainties

- Validation: Verify on test set that the probability of (\text{max RMSE} > \text{calibrated } u) is approximately (\alpha)

Technical Notes:

- For α=0.05, approximately 5% of test points may have errors exceeding their calibrated uncertainties [16]

- Regularly update the calibration set as new configurations are acquired during AL

- Monitor calibration quality as the MLIP evolves to maintain reliability

Acquisition Strategies for Configurational Sampling

Acquisition strategies determine how MD simulations explore configurational space to identify regions where the MLIP would benefit from additional training data. Effective strategies balance exploration of novel regions with exploitation of known important areas.

Uncertainty-Biased Molecular Dynamics

Uncertainty-biased MD modifies the potential energy surface to actively drive simulations toward high-uncertainty regions, dramatically accelerating the discovery of extrapolative configurations and rare events [16] [14].

The core approach adds a bias potential (E{\text{bias}}) that is directly proportional to the MLIP's uncertainty metric [14]: [ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{MLIP}} + w \cdot E{\text{bias}}(\sigmaE^2) ] where (w) is a weighting factor and (\sigmaE^2) is the energy uncertainty variance, typically computed as: [ \sigmaE^2 = \frac{1}{2} \sumi^{NM} (\hat{Ei} - \bar{E})^2 ] for an ensemble of (N_M) models [14].

This approach simultaneously captures extrapolative regions and rare events, which is crucial for developing uniformly accurate MLIPs [16]. By exploiting automatic differentiation, bias forces can be enhanced with the concept of bias stress, enabling efficient exploration in isothermal-isobaric (NpT) ensembles [16].

Uncertainty-Biased Dynamics Workflow: This diagram illustrates the active learning cycle where molecular dynamics is biased toward high-uncertainty regions to efficiently acquire new training data.

RMSD-Based Frame Selection

For coarse-grained (CG) neural network potentials, root mean squared deviation (RMSD) between configurations provides an effective acquisition metric that identifies coverage gaps in conformational space [4] [3].

The RMSD-based approach selects frames with the largest structural discrepancies from the training dataset, targeting the least-explored configurations [3]. This method is particularly valuable for biomolecular systems where preserving CG-level efficiency while correcting model deficiencies is essential.

Protocol: Implementing Uncertainty-Biased MD for Rare Event Sampling

Objective: Accelerate exploration of rare events and extrapolative regions in conformational space using uncertainty-biased dynamics.

Materials:

- MLIP with ensemble or gradient-based uncertainty capability

- MD engine with modified dynamics capability (e.g., LAMMPS with PLUMED)

- Initial training data covering basic configurations

- Access to DFT oracle for reference calculations

Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Begin with MD simulation using current MLIP forces

- Set bias strength parameter (w) (start with 0.1-0.5 eV for energy uncertainties)

- Define uncertainty threshold for triggering DFT calls

Bias Force Calculation:

- Compute uncertainty (\sigma_E) for current configuration using ensemble or gradient-based method

- Calculate bias force: (F{\text{bias}} = -w \cdot \nabla \sigmaE^2)

- For NpT simulations, compute bias stress: (\tau{\text{bias}} = -w \cdot \frac{\partial \sigmaE^2}{\partial \epsilon}) where (\epsilon) is the strain tensor [16]

Dynamics Propagation:

- Apply total force: (F{\text{total}} = F{\text{MLIP}} + F_{\text{bias}})

- Integrate equations of motion using modified forces

- For NVT ensemble, use standard thermostating

- For NpT ensemble, apply barostat using modified stress tensor

Uncertainty Monitoring:

- Monitor maximum atomic uncertainty at each step

- When (\max(u_i)) exceeds threshold, pause simulation and:

- Extract current configuration

- Submit to DFT oracle for energy, forces, and stress calculation

- Add labeled data to training set

Model Update:

- Retrain MLIP with augmented dataset

- Resume biased MD with updated model

- Continue until uncertainty remains below threshold throughout target simulation time

Technical Notes:

- Adjust bias strength (w) to balance exploration efficiency and physical relevance

- For temperature-sensitive molecules, UDD enables efficient sampling at low-T conditions where regular MD would be trapped [14]

- The bias potential acts similarly to metadynamics but without requiring manual selection of collective variables [14]

Oracle Implementations and Data Generation

Oracles provide the ground-truth labels that form the foundation of AL training data. In molecular simulations, these typically involve quantum mechanical calculations, though experimental data can also serve as oracles in certain contexts.

Quantum Mechanical Oracles

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations serve as the most common oracle in MLIP development, providing accurate energies, forces, and stresses for atomic configurations [18]. The key challenge is balancing computational cost with accuracy requirements.

Table 3: Oracle Implementation Strategies

| Oracle Type | Accuracy Level | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Planewave/Pseudopotential) | High | Very High | Final production data, small systems |

| DFT (Tight-Binding) | Medium | Moderate | Large systems, high-throughput screening |

| Quantum Chemistry (CCSD(T)) | Very High | Extremely High | Benchmarking, small molecule reference |

| Projected All-Atom (for CG) | Medium (Mapping Dependent) | Low (after AA simulation) | Coarse-grained active learning [3] |

Advanced Oracle Strategies: Receptor Ensembles in Drug Discovery

In virtual screening applications, MD-generated receptor ensembles significantly enhance oracle effectiveness by accounting for protein flexibility and multiple conformational states [1].

The ensemble approach involves:

- Generating ≈100µs MD simulation of the target protein

- Selecting 20+ representative snapshots as docking targets

- Docking candidates to each structure in the ensemble

- Using consensus scoring across the ensemble [1]

This strategy dramatically improves hit rates compared to single-structure docking. For TMPRSS2 inhibitor screening, using a receptor ensemble reduced the number of compounds requiring computational screening from 2230.4 to 262.4 while improving known inhibitor ranking from top 709.0 to top 5.6 positions [1].

Protocol: Implementing Parallel Oracle Queries with PAL

Objective: Efficiently manage oracle queries in parallel AL workflows using the PAL (Parallel Active Learning) framework [18].

Materials:

- PAL library (MPI-based Python framework)

- High-performance computing cluster

- Quantum chemistry software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, etc.)

- Configuration database

Procedure:

- PAL Architecture Setup:

- Deploy five core kernels: Prediction, Generator, Training, Oracle, and Controller

- Establish MPI communication between kernels

- Configure resource allocation for each kernel type

Oracle Kernel Configuration:

- Implement DFT calculation workflows within Oracle processes

- Set up point-to-point communication with Controller kernel

- Configure input/output handling for atomic configurations and labels

Parallel Execution:

- Controller identifies high-uncertainty configurations requiring labeling

- Controller distributes labeling tasks to available Oracle processes

- Multiple DFT calculations proceed simultaneously

- Completed labels are returned to Controller and distributed to Training kernel

Dynamic Workflow Management:

- Training kernel updates ML models with new data

- Prediction kernel replicates updated model weights periodically

- Generator kernel continues exploration while training occurs

- Process continues until uncertainty thresholds are met consistently

Technical Notes:

- PAL achieves significant speed-ups through asynchronous parallelization on CPU and GPU hardware [18]

- The framework minimizes disruptions in data generation and inference caused by time-consuming labeling and training processes [18]

- Modular design allows customization for specific scientific applications beyond atomistic simulations

Integrated Workflows and Research Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for AL-MD Implementation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLARE | Bayesian Force Field | GP-based MLIP with built-in UQ | Autonomous AL for materials [15] |

| PAL | AL Framework | Parallel active learning workflow management | High-throughput AL on HPC systems [18] |

| CGSchNet | Neural Network Potential | Coarse-grained molecular modeling | Biomolecular AL with AA backmapping [3] |

| DP-GEN | AL Framework | Deep potential generator | Materials discovery [3] |

| ANI | Neural Network Potential | Transferable MLIP for organic molecules | Conformational sampling [14] |

| LAMMPS | MD Engine | Molecular dynamics simulations | Production MD with MLIPs [15] |

Complete Integrated AL-MD Workflow

Integrated AL-MD Framework: Complete workflow showing the interaction between uncertainty quantification, acquisition strategies, and oracle queries in an active learning molecular dynamics simulation.

Protocol: End-to-End AL-MD for Drug Target Screening

Objective: Implement a complete AL-MD workflow for virtual screening of drug candidates against a protein target.

Materials:

- Target protein structure (experimental or homology model)

- Compound library for screening

- MD simulation software with enhanced sampling capabilities

- Docking software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, etc.)

- MLIP training framework (FLARE, PANNA, etc.)

Procedure:

- Initial Receptor Ensemble Generation:

- Run 100+ µs MD simulation of target protein

- Cluster trajectories to identify representative conformations

- Select 20+ structures for docking ensemble

Active Learning Virtual Screening:

- Start with 1% random sample from compound library

- Dock candidates to receptor ensemble

- Compute target-specific inhibition score (e.g., h-score for TMPRSS2) [1]

- Select top candidates for MD refinement

Binding Affinity Refinement:

- Run multiple short MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes

- Compute dynamic binding scores from trajectories

- Use uncertainty estimates to identify candidates for free energy calculations

Iterative AL Cycle:

- Retrain scoring function based on new data

- Select next batch of compounds focusing on high-uncertainty regions

- Continue until convergence or experimental validation

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize or acquire top-ranked candidates

- Perform in vitro binding assays

- Use results to further refine AL model

Technical Notes:

- For TMPRSS2 screening, this approach identified BMS-262084 (IC50 = 1.82 nM) with less than 20 candidates requiring experimental testing [1]

- The combination of receptor ensemble and target-specific scoring reduced computational costs by ~29-fold compared to brute-force approaches [1]

- Dynamic scoring from MD simulations increases sensitivity from 0.5 to 0.88 for classifying true inhibitors [1]

The integration of robust Uncertainty Quantification, targeted Acquisition Strategies, and efficient Oracle implementations creates a powerful framework for accelerating molecular simulations and materials discovery. The protocols and reagents detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical tools for implementing AL-MD in diverse contexts, from materials phase transformations to drug discovery. As these methods continue to mature, they promise to significantly reduce the computational cost and human effort required for reliable molecular simulations while improving accuracy and predictive power across scientific domains.

Synergy with Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

The integration of active learning (AL) with machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) is revolutionizing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. This synergy addresses a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and materials science: achieving the accuracy of quantum mechanical methods like density functional theory (DFT) at a fraction of the computational cost. MLIPs are data-driven surrogates that learn the potential energy surface (PES) from ab initio data, enabling large-scale and long-time-scale MD simulations [19]. However, their accuracy and reliability are contingent on the quality and comprehensiveness of their training data.

Active learning resolves this by implementing an intelligent, iterative data selection process. Instead of relying on exhaustive, pre-computed datasets, AL frameworks strategically query an oracle—typically a high-fidelity but computationally expensive method like DFT—to label new atomic configurations only when the MLIP exhibits high uncertainty [20] [18]. This creates a self-improving loop where the MLIP guides its own data acquisition, leading to highly accurate and robust models with minimal computational effort. This application note details the protocols and reagent solutions for implementing this powerful synergy, framed within a broader active learning MD simulation framework.

Key Applications and Quantitative Performance

The AL-MLIP paradigm has been successfully applied across diverse domains, from material science to drug discovery. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of AL-MLIP Frameworks in Various Applications

| Application Area | AL Framework / Model | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrared Spectra Prediction | PALIRS (MACE MLIP) | Accurately reproduces IR spectra from ab initio MD at a fraction of the computational cost. | [5] | |

| Virtual Drug Screening | Target-Specific Score + MD | Reduced compounds for experimental testing from ~1299 to ~8 (a >200-fold reduction). | [21] | |

| Virtual Drug Screening | Target-Specific Score + MD | Reduced computational cost by ~29-fold. | [21] | |

| Coarse-Grained MD | CGSchNet with AL | 33.05% improvement in the W1 metric in TICA space for protein dynamics. | [3] | |

| Dataset Generation | Strategic Configuration Sampling (SCS) | Enables automated, high-throughput generation of compact, comprehensive MLIP training datasets. | [20] | |

| Workflow Efficiency | PAL (Parallel AL) | Achieved significant speed-ups through asynchronous parallelization on CPU and GPU hardware. | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing an active learning loop for MLIPs, drawing from established frameworks like PALIRS [5] and SCS [20].

Protocol: Iterative Active Learning for MLIP Refinement

Objective: To construct a accurate and reliable MLIP through an iterative cycle of uncertainty-driven data generation.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the core active learning loop for MLIP development.

Materials:

- Initial Data: A small set of atomic configurations (e.g., from normal mode sampling or short AIMD runs) with reference energies and forces from DFT.

- Software: An AL framework (e.g., PALIRS, SCS, PAL), MLIP code (e.g., MACE, DeePMD-kit), MD engine (e.g., LAMMPS, ASE), and DFT code (e.g., FHI-aims, Quantum ESPRESSO).

Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Initial Data Generation: Begin with a small, diverse set of atomic configurations. For molecular systems, sample along normal vibrational modes or run a short, high-temperature AIMD simulation to capture anharmonicities [5].

- Oracle Calculation: Perform single-point DFT calculations on these configurations to obtain reference energies and forces.

- Initial MLIP Training: Train an initial MLIP model (or an ensemble of models) on this dataset. Using an ensemble of models enables uncertainty quantification through their prediction variance [20].

Exploration and Sampling (Generator Kernel):

- Machine Learning-assisted MD (MLMD): Use the current MLIP to run an MD simulation. To thoroughly explore the configurational space, run simulations at multiple temperatures (e.g., 300 K, 500 K, 700 K) [5]. Frameworks like SCS can automate the setup of complex exploration workflows, including "collaging" to build complex geometries from previous runs [20].

- Uncertainty Quantification: During the MLMD trajectory, calculate the uncertainty of the MLIP predictions. For an ensemble, this is typically the standard deviation of the predicted forces on each atom:

σ²(F_i,α) = (1/M) Σ (F_i,α^j - ⟨F_i,α⟩)², whereMis the number of models, andF_i,α^jis the force on atomiin directionαpredicted by modelj[20]. - Configuration Selection: Sample frames from the trajectory that exhibit the highest uncertainty. To ensure diversity and avoid redundancy, select only the highest-uncertainty frame from equal-time windows along the trajectory [20].

Oracle Query and Retraining (Oracle & Training Kernels):

- High-Fidelity Labeling: Submit the selected high-uncertainty configurations to the oracle (DFT) for accurate calculation of energies and forces [18].

- Data Validation and Filtering: Filter out configurations with unphysical properties (e.g., extreme atomic forces > 30 eV/Å) that could destabilize training [20].

- Dataset Augmentation and Retraining: Add the newly labeled, cleaned data to the training dataset. Retrain the MLIP ensemble on this augmented dataset [5] [18].

Iteration and Convergence:

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the MLIP's uncertainty on new MLMD trajectories falls below a predefined threshold, indicating robust performance across the relevant configurational space [18].

Protocol: Active Learning for IR Spectra Prediction (PALIRS)

Objective: To efficiently predict accurate infrared (IR) spectra of organic molecules using an AL-enhanced MLIP.

Workflow Overview: The PALIRS framework extends the general AL-MLIP workflow by adding a dedicated model for dipole moment prediction, which is crucial for calculating IR spectra [5].

Materials:

- The materials from Protocol 3.1 are required.

- Additionally, reference dipole moments from DFT calculations are needed for training the dipole model.

Procedure:

- Follow Protocol 3.1 to train a general-purpose MLIP for accurate energy and force predictions.

- Train a Dipole Moment Model: Using the final dataset generated by the AL cycle, train a separate ML model (e.g., a MACE model) to predict the molecular dipole moment vector for any given atomic configuration [5].

- Production MLMD for IR Spectra:

- Using the finalized MLIP, run a long, well-converged MLMD simulation at the desired temperature.

- For every configuration in the trajectory, use the dipole moment model to predict the dipole vector.

- Compute the IR Spectrum:

- Calculate the dipole moment autocorrelation function from the trajectory.

- The Fourier transform of this autocorrelation function yields the IR absorption spectrum, which includes anharmonic effects naturally captured by the dynamics [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of an AL-MLIP framework relies on a suite of software tools and computational resources. The following table catalogs the key components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AL-MLIP

| Tool Category | Specific Software / Resource | Function and Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Frameworks | PALIRS [5], SCS (Strategic Configuration Sampling) [20], PAL (Parallel Active Learning) [18] | Orchestrates the entire AL cycle: manages data flow, launches simulations, handles uncertainty-based sampling, and triggers retraining. |

| MLIP Architectures | MACE [5] [20], DeePMD-kit (Deep Potential) [19] [20], NequIP [19], Allegro [19] [18] | Machine learning models that serve as the fast, surrogate potential. They predict energies and forces given atomic coordinates. |

| Ab Initio Oracle | FHI-aims [5], Quantum ESPRESSO [20], Gaussian, VASP | Provides high-fidelity ground truth data (energies, forces, dipole moments) for training and active learning queries. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | LAMMPS [20], ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [20] | Performs the molecular dynamics simulations using the MLIP for force evaluations. |

| System Preparation & Sampling | Packmol [20] | Automates the construction of initial molecular and interfacial systems for simulation. |

| Benchmark Datasets | MD17, MD22 [19], QM9 [19] | Publicly available datasets for training and benchmarking MLIPs on specific molecular systems. |

Workflow Visualization: PAL Framework Architecture

For large-scale simulations, parallelization is critical. The PAL framework exemplifies a modern, scalable architecture that decouples AL components for efficient execution on high-performance computing resources [18].

Exploring Chemical and Conformational Space with Active Learning

The process of drug discovery has traditionally been characterized as a "needle-in-a-haystack" problem, requiring the identification of a few effective molecular inhibitors from vast libraries of potential candidates [1]. Conventional large-scale experimental screens are prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, while brute-force virtual screening approaches often trade computational efficiency for experimental accuracy [1]. In recent years, active learning (AL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm that strategically combines machine learning with molecular simulations to navigate chemical space efficiently. This methodology closely mimics the iterative design-make-test-analyze cycle of laboratory experiments, intelligently selecting the most informative molecular structures for evaluation in each cycle [22]. By prioritizing computational resources on promising regions of chemical space, active learning frameworks dramatically reduce both computational overhead and experimental validation requirements, enabling accelerated molecular discovery and optimization [1] [22].

The integration of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with active learning represents a particularly powerful approach for exploring both chemical and conformational space [1]. MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions, binding mechanisms, and conformational changes that are critical for understanding biological function and inhibition [23]. When coupled with active learning cycles, these simulations enable intelligent exploration of complex biomolecular landscapes, guiding the discovery process toward regions with high probability of success [3]. This review presents application notes and protocols for implementing active learning molecular dynamics frameworks, with specific examples from recent successful applications in drug discovery.

Active Learning Molecular Dynamics Framework

Core Framework Components

The active learning molecular dynamics framework comprises several interconnected components that work in concert to enable efficient exploration of chemical and conformational space. The foundational elements include molecular dynamics simulations for conformational sampling, machine learning models for prediction and guidance, and experimental validation to close the learning loop [1] [22].

Table 1: Core Components of Active Learning Molecular Dynamics Frameworks

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Ensemble Generation | Captures protein flexibility and multiple conformational states | ≈100-µs MD simulation of apo receptor; 20 snapshots for docking [1] |

| Target-Specific Scoring | Evaluates potential inhibitors based on structural features | Empirical score rewarding S1 pocket occlusion and reactive feature distances [1] |

| Active Learning Cycle | Intelligently selects compounds for subsequent evaluation | Iterative batch selection based on scoring function rankings [1] [22] |

| Molecular Dynamics Validation | Refines docking poses and eliminates false positives | 10-ns simulations of protein-ligand complexes; 100 ns per ligand [1] |

Quantitative Performance Advantages

Recent implementations of active learning frameworks have demonstrated significant improvements in efficiency and effectiveness compared to traditional virtual screening approaches. The quantitative advantages are substantial across multiple metrics relevant to drug discovery pipelines.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Screening Approaches

| Metric | Traditional Docking Score | Active Learning with Target-Specific Score | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Screening | 2,755.2 compounds | 262.4 compounds | ~10.5x reduction |

| Simulation Time | 15,612.8 hours | 1,486.9 hours | ~10.5x reduction |

| Experimental Screening | Top 1,299.4 compounds | Top 5.6 compounds | ~232x reduction |

| Known Inhibitor Ranking | Correlation of 0.2 | Correlation of 1.0 | 5x improvement |

The performance advantages extend beyond simple efficiency metrics. In one implementation, the active learning approach reduced computational costs by approximately 29-fold while maintaining high accuracy in identifying true inhibitors [1]. This dramatic improvement stems from the framework's ability to focus resources on chemically relevant regions and avoid wasteful exploration of unproductive chemical space.

Application Notes: Case Studies

TMPRSS2 Inhibitor Discovery

A notable application of active learning molecular dynamics led to the identification of BMS-262084 as a potent inhibitor of TMPRSS2, with an experimental IC50 of 1.82 nM [1]. This discovery exemplifies the power of combining MD simulations with active learning for efficient navigation of chemical space.

Experimental Protocol:

- Receptor Ensemble Preparation: Generated a ≈100-µs MD simulation of TMPRSS2 and selected 20 snapshots representing conformational diversity [1]

- Initial Library Screening: Conducted molecular docking of 1% of the DrugBank library against the receptor ensemble

- Target-Specific Scoring: Implemented an empirical scoring function that rewarded occlusion of the S1 pocket and adjacent hydrophobic patch, with short distances for reactive and recognition states [1]

- Active Learning Cycles: Iteratively selected extension sets of compounds based on the target-specific score, with each set comprising 1% of the library

- Dynamic Validation: Performed 10-ns MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes for top-ranking candidates (totaling 100 ns per ligand) to eliminate false positives [1]

- Experimental Verification: Conducted cell-based assays confirming BMS-262084's efficacy in blocking entry of various SARS-CoV-2 variants and other coronaviruses [1]

The target-specific score was critical to the success of this approach, significantly outperforming conventional docking scores with a sensitivity of 0.5 compared to 0.38 [1]. When combined with MD-based validation, the sensitivity increased further to 0.88, demonstrating the value of incorporating protein flexibility and dynamic information [1].

Generative Active Learning for 3CLpro and TNKS2

A second case study employed a generative active learning protocol combining REINVENT (a generative molecular AI) with precise binding free energy ranking simulations using ESMACS [22]. This approach discovered new ligands for two different target proteins: 3CLpro and TNKS2.

Experimental Protocol:

- Generative Design: Used REINVENT to generate novel molecular structures based on initial training data [22]

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Employed ESMACS for absolute binding free energy calculations via molecular dynamics simulations [22]

- Active Learning Cycle: Selected batches of molecules for free energy assessment based on generative model predictions

- Batch Size Optimization: Varied batch sizes in each GAL cycle to determine optimal values for different scenarios [22]

- Chemical Space Analysis: Evaluated discovered ligands for chemical diversity and novelty compared to baseline compounds [22]

This implementation demonstrated the protocol's capability to discover higher-scoring molecules compared to baseline approaches, with the found ligands occupying distinct chemical spaces from known compounds [22]. The deployment on Frontier, the world's only exascale machine, enabled unprecedented sampling of chemical space through the combination of physics-based and AI methods [22].

Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

Active Learning Molecular Dynamics Workflow

Active Learning MD Screening Process

Coarse-Grained Active Learning Framework

CG to AA Active Learning Cycle

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of active learning molecular dynamics requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in the framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Active Learning MD

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Ensemble | Multiple protein conformations for docking | 20 snapshots from ≈100-µs MD simulation; critical for capturing binding-competent states [1] |

| Target-Specific Score | Empirical or learned scoring function | For TMPRSS2: rewards S1 pocket occlusion; for trypsin-domain proteins: random forest regressor with ∆SASA features [1] |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | All-atom simulation capability | Enables 10-100 ns validation simulations; requires ≈818 µs total for 8180 ligands [1] |

| Active Learning Selector | Intelligent batch compound selection | Reduces experimental testing to <20 compounds; cuts computational costs by ~29-fold [1] |

| Coarse-Grained Neural Network | CGSchNet for accelerated sampling | Graph neural network using continuous filter convolutions; enables longer timescales [3] |

| All-Atom Oracle | High-accuracy reference calculations | OpenMM simulations for ground-truth forces; queried selectively via active learning [3] |

Implementation Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Active Learning Screening

This protocol details the implementation of a structure-based active learning framework for molecular discovery, optimized for targets with known structural information.

Step 1: Receptor Preparation and Ensemble Generation

- Conduct extensive MD simulations (≈100 µs) of the apo receptor to sample conformational diversity [1]

- Select 20 representative snapshots that capture distinct binding-competent states

- Validate ensemble diversity through RMSD clustering and binding site analysis

Step 2: Initial Library Docking and Scoring

- Dock a small initial set (1% of library) to all receptor conformations

- Apply target-specific scoring function (static h-score) to rank compounds

- For TMPRSS2-like targets: use empirical score based on S1 pocket occlusion and hydrophobic patch interactions [1]

- For general trypsin-domain proteins: implement learned score using random forest regressor trained on ∆SASA values and residue distances [1]

Step 3: Active Learning Cycle Implementation

- Select top-ranking compounds for MD validation (10-ns simulations per complex)

- Compute dynamic h-scores from MD trajectories to eliminate false positives

- Choose subsequent batch based on consensus ranking from multiple scoring approaches

- Continue iterations until convergence (typically 4-6 cycles) or identification of high-confidence hits

Step 4: Experimental Validation

- Synthesize or source top-ranked compounds for experimental testing

- Conduct biochemical assays to determine IC50 values

- Validate cellular efficacy in relevant disease models [1]

Protocol 2: Generative Active Learning with Coarse-Graining

This protocol implements a generative active learning approach combining AI-driven molecular design with coarse-grained molecular dynamics for enhanced efficiency.

Step 1: Initial Data Generation and Model Training

- Generate initial all-atom MD dataset for target system

- Train CGSchNet neural network potential via force matching:

- Use continuous filter convolutions based on inter-bead distances

- Minimize force matching loss: ℒℱℳ(θ) = (1/T)∑‖𝐅θ(𝐑) - 𝐅CG‖² [3]

- Ensure rotational and translational invariance in energy predictions

Step 2: Active Learning with Uncertainty Sampling

- Run CG MD simulations using trained neural network potential

- Calculate RMSD between simulation frames and training dataset

- Select frames with largest RMSD values (greatest conformational differences)

- Backmap selected frames to all-atom resolution using projection operators [3]

Step 3: Oracle Query and Dataset Expansion

- Query all-atom oracle (OpenMM) for selected configurations to obtain reference forces [3]

- Project all-atom forces back to CG space using force projection operator: 𝐅CG = ΞF𝐟AA [3]

- Append new data to training dataset with emphasis on coverage gaps

Step 4: Model Retraining and Validation

- Retrain CGSchNet on expanded dataset

- Validate using TICA (Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis) and free-energy metrics [3]

- Target >30% improvement in Wasserstein-1 metric in TICA space compared to baseline [3]

- Repeat active learning cycles until performance convergence

Discussion and Outlook

The integration of active learning with molecular dynamics simulations represents a paradigm shift in computational molecular discovery. By strategically guiding computational and experimental resources, these frameworks achieve unprecedented efficiency in navigating complex chemical and conformational spaces. The case studies presented demonstrate tangible successes, from the discovery of potent nanomolar inhibitors to the generation of novel chemical entities with desired binding properties.

Future developments in active learning molecular dynamics will likely focus on several key areas. Multiscale simulation methodologies will bridge wider temporal and spatial scales, while high-performance computing technologies like exascale computing will enable more comprehensive sampling [22] [23]. The integration of experimental and simulation data through automated platforms will create closed-loop discovery systems, and increased emphasis on environmental impact will drive the development of greener molecular solutions [23]. As these technologies mature, active learning molecular dynamics frameworks will become increasingly central to molecular design and optimization across pharmaceutical, materials, and chemical industries.

The protocols and application notes provided herein offer researchers practical guidance for implementing these powerful methodologies, with specific examples demonstrating their effectiveness in real-world discovery campaigns.

Implementing Active Learning MD: From Spectra Prediction to Drug Design

The development of machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) has become a cornerstone of modern atomistic simulation, enabling large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) with quantum-mechanical accuracy. A significant bottleneck in this process remains the manual generation and curation of high-quality training data. This challenge has spurred the creation of automated software frameworks that leverage active learning to efficiently explore potential-energy surfaces and construct robust MLIPs. Within the broader thesis on active learning molecular dynamics simulation frameworks, this application note provides a detailed examination of two key open-source frameworks, PALIRS and autoplex, and contextualizes them alongside established commercial modeling suites. We present structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential workflow visualizations to guide researchers and drug development professionals in implementing these powerful tools.

The autoplex Framework

autoplex ("automatic potential-landscape explorer") is an openly available software package designed to automate the exploration of potential-energy surfaces and the fitting of MLIPs [11] [24]. Its core innovation lies in automating iterative random structure searching (RSS) and model training, significantly reducing the human effort required to develop MLIPs from scratch. The framework is modular and interoperable with existing computational materials science infrastructures, notably building upon the atomate2 workflow system that underpins the Materials Project [11] [25]. A key application of autoplex is its integration with Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP), leveraging their data efficiency for tasks ranging from modeling elemental systems like silicon to complex binary systems such as titanium-oxygen [11] [24].

The PALIRS Framework

PALIRS (Python-based Active Learning Code for Infrared Spectroscopy) is an open-source active learning framework specifically designed for the efficient prediction of IR spectra using MLIPs [5]. It addresses the computational expense of ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) for IR spectroscopy by training MLIPs on strategically selected data. The framework employs an active learning cycle to iteratively improve a neural network-based MLIP (e.g., MACE models), and separately trains a model for molecular dipole moment prediction, which is crucial for calculating IR spectra from MD trajectories [5].

Commercial Modeling Suites

Commercial software suites provide integrated, user-friendly environments for multiscale materials modeling. These platforms often combine various simulation engines, analysis tools, and workflow automation capabilities.

- MedeA (Materials Design, Inc.): An environment that integrates multiple simulation engines (e.g., VASP, LAMMPS, Gaussian) for property prediction and materials discovery. Its high-throughput modules, HT-Launchpad and HT-Descriptors, facilitate the generation of large, consistent datasets for screening and optimizing materials, creating input for machine learning procedures [26].

- Materials Studio (BIOVIA): A comprehensive modeling environment that includes quantum, atomistic, mesoscale, and statistical tools. Its integration with the Pipeline Pilot platform allows for the automation of routine calculations and the deployment of complex, multistep workflows as reusable "protocols," including for polymer informatics [26].

- CULGI: A software suite covering quantum mechanics to coarse-grained modeling and informatics. It features scripted workflows and a multiscale approach, enabling the building and simulation of complex systems, such as creating coarse-grained polymer structures and then reverse-mapping them to all-atom representations for further MD study [26].

Table 1: Key Features of Software Frameworks for Atomistic Modeling

| Framework | Primary Focus | Core Methodology | Key Automation Feature | Reported Output/Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| autoplex [11] [24] | General-purpose MLIP development | Random Structure Searching (RSS) & iterative fitting | Automated workflow for exploration, data assembly, and fitting | Energy RMSE of ~0.01 eV/atom for Si allotropes [11] |

| PALIRS [5] | Infrared spectra prediction | Active learning for MLIP & dipole moment training | Iterative data selection based on uncertainty in forces | Accurate IR peak positions/amplitudes vs. AIMD/experiment [5] |

| MedeA [26] | Integrated multiscale materials engineering | High-throughput computation & workflow management | HT-Launchpad for automated high-throughput screening | Enables generation of descriptors for machine learning [26] |

| Materials Studio [26] | Integrated multiscale materials science | Multiscale simulation & informatics | Pipeline Pilot for protocol creation and workflow automation | Streamlines polymer property prediction and catalyst design [26] |

| CULGI [26] | Complex chemical systems, formulations | Multiscale modeling (QM to mesoscale) | Scripted workflows for cross-scale simulation | Calibrates coarse-grained models using COSMO-RS thermodynamics [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Automated MLIP Development with autoplex

The following methodology outlines the procedure for developing a robust MLIP using the autoplex framework, as demonstrated for the titanium-oxygen system [11] [24].

Initialization and System Definition:

- Define the chemical system (e.g., elemental, binary like Ti-O) and set the initial RSS parameters. This includes specifying the composition space to be explored.

- Configure the computational parameters for the underlying density-functional theory (DFT) calculations that will serve as the reference data source.

Iterative Exploration and Training Cycle:

- Step 1: Structure Generation. Generate a batch (e.g., 100) of random initial atomic structures within the defined chemical system.

- Step 2: MLIP Relaxation. Relax these generated structures using the current, best-available MLIP (initially, this may be a very simple model or non-existent, requiring the first iteration to use DFT).

- Step 3: DFT Single-Point Calculations. Perform single-point DFT energy and force calculations on the MLIP-relaxed structures. This step provides the quantum-mechanical reference data without the cost of full DFT molecular dynamics.

- Step 4: Dataset Expansion. Add the new structures and their DFT-calculated energies and forces to the training dataset.

- Step 5: MLIP Refitting. Retrain the MLIP (e.g., a GAP model) on the expanded training dataset to create an improved potential.

- Step 6: Error Evaluation. Evaluate the new model's accuracy on a set of known reference structures (e.g., crystalline polymorphs) by calculating the root mean square error (RMSE) of energies. The cycle (Steps 1-6) is repeated until the energy RMSE for key phases falls below a target threshold (e.g., 0.01 eV/atom) [11].

Validation and Production Simulation:

- Validate the final MLIP by comparing its predictions for properties (e.g., lattice parameters, relative phase energies) against pure DFT calculations or experimental data.

- Use the validated MLIP for large-scale or long-time MD simulations to investigate target phenomena.

Protocol for IR Spectra Prediction with PALIRS

This protocol details the four-step workflow for predicting accurate IR spectra of small organic molecules using the PALIRS framework [5].

Initial Data Preparation and MLIP Training:

- Step 1: Initial Dataset. For the target molecules, generate an initial set of molecular geometries by sampling along their normal vibrational modes. Compute reference energies and forces for these geometries using DFT.

- Step 2: Initial MLIP Training. Train an initial ensemble of MLIPs (e.g., MACE models) on this small dataset. An ensemble is used to estimate the uncertainty of force predictions.

Active Learning Cycle for MLIP Refinement:

- Step 3: ML-Driven MD (MLMD). Perform molecular dynamics simulations using the current MLIP at multiple temperatures (e.g., 300 K, 500 K, 700 K) to explore a broad configurational space.

- Step 4: Uncertainty-Based Acquisition. From the MLMD trajectories, select molecular configurations where the MLIP ensemble shows the highest uncertainty in its force predictions.

- Step 5: Oracle Query. Perform DFT calculations on the acquired structures to obtain accurate energies and forces.

- Step 6: Dataset Expansion and Retraining. Add these new data points to the training set and retrain the MLIP. Iterate Steps 3-6 until the model's performance on a validation set (e.g., harmonic frequencies) converges.

Dipole Moment Model Training and IR Spectra Calculation:

- Step 7: Dipole Model Training. Using the final, converged active learning dataset, train a separate ML model (e.g., a MACE model configured for dipole prediction) to predict the molecular dipole moment for any given atomic configuration.

- Step 8: Production MLMD for Spectra. Run a final, long MLMD production simulation using the refined MLIP (for energies and forces) and the dipole model.

- Step 9: IR Spectra Generation. Compute the IR spectrum by calculating the autocorrelation function of the dipole moment time series recorded during the production MLMD trajectory.

Key Reagents and Computational Materials

The following table details the essential software, tools, and computational "reagents" required to implement the protocols described for the autoplex and PALIRS frameworks.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Active Learning MD

| Item Name | Type | Function in Protocol | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | Software Engine | Serves as the "oracle" for generating reference quantum-mechanical data (energies, forces) during training [11] [5]. | FHI-aims [5]; VASP is also commonly used. |

| MLIP Architecture | Core Model | Machine-learning model that learns the interatomic potential from DFT data. | Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) [11]; MACE [5]. |

| Active Learning Scheduler | Software Module | Manages the iterative workflow: launches searches/MD, queries oracle, and triggers retraining [11] [5]. | Built into autoplex and PALIRS. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Software Engine | Propagates the dynamics of the atomic system using forces from the MLIP. | Can be an internal engine or link to external codes like LAMMPS. |

| Uncertainty Quantifier | Algorithmic Method | Identifies regions of configurational space where the MLIP is uncertain, guiding data acquisition [5]. | Ensemble of MACE models [5]; intrinsic variance in GAP [11]. |

| Structure Generator | Algorithmic Method | Creates diverse initial atomic configurations for exploration. | Random Structure Searching (RSS) in autoplex [11]. |

| Dipole Moment Predictor | Machine Learning Model | Predicts the electronic dipole moment of a configuration for IR intensity calculation [5]. | A separately trained MACE model in PALIRS [5]. |

Results and Performance Data

The performance of the autoplex and PALIRS frameworks is demonstrated through quantitative benchmarks on representative systems.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks for the autoplex Framework on Material Systems [11] [24]

| Material System | Tested Structure/Phase | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Silicon (Si) | Diamond-type | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | ~0.01 eV/atom after ~500 DFT single-points [11] |

| β-tin-type | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | ~0.01 eV/atom after ~500 DFT single-points [11] | |

| oS24 allotrope | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | ~0.01 eV/atom after a few thousand DFT single-points [11] | |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Anatase | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | ~0.1 meV/atom (GAP-RSS on TiO₂ only) [24] |

| Brookite | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | ~10 meV/atom (GAP-RSS on TiO₂ only) [24] | |

| Full Ti-O System | Rocksalt-type TiO | Energy RMSE (eV/atom) | Achieved target accuracy, requiring more iterations [11] |

Table 4: Performance Outcomes for the PALIRS Framework [5]

| Assessment Aspect | Metric | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Active Learning Efficacy | Model improvement on test set of harmonic frequencies | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) reduced through iterative active learning cycles [5]. |

| IR Spectra Accuracy | Comparison of peak positions and amplitudes | Agreement with both AIMD references and available experimental data [5]. |

| Computational Efficiency | Speedup vs. AIMD | MLIP-based MD simulations reported to be orders of magnitude faster than AIMD [5]. |

| Dataset Efficiency | Final dataset size for 24 organic molecules | ~16,067 structures after 40 active learning iterations (~600-800 structures/molecule) [5]. |

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy serves as a pivotal analytical tool across chemistry, biology, and materials science, providing real-time molecular insight into material structures and enabling the observation of reaction intermediates in situ. [5] However, interpreting experimental IR spectra is challenging due to peak shifts and intensity variations caused by molecular interactions and spectral congestion. [5] Traditional theoretical methods like density functional theory (DFT)-based ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) provide higher-fidelity simulations that include anharmonic effects but are computationally prohibitive for large systems and high-throughput screening. [5]

The integration of machine learning (ML) with molecular dynamics (MD) offers a promising path to overcome these limitations. This case study explores the Python-based Active Learning Code for Infrared Spectroscopy (PALIRS) framework, which leverages an active learning-enhanced machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP) to efficiently and accurately predict the IR spectra of small, catalytically relevant organic molecules. [5] By demonstrating accuracy comparable to AIMD at a fraction of the computational cost, PALIRS enables the exploration of larger catalytic systems and aids in identifying novel reaction pathways. [5]

The PALIRS framework implements a novel four-step approach designed to efficiently construct training datasets and predict IR spectra. [5] Its core innovation lies in using an active learning strategy to train a machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP), which is then used for molecular dynamics simulations to calculate IR spectra. [5]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the PALIRS computational process:

Core Components of the PALIRS Workflow

Step 1: Active Learning for MLIP Training: PALIRS initiates with an initial dataset of molecular geometries sampled along normal vibrational modes from DFT calculations. [5] An initial MLIP based on the MACE (Message Passing with Equivariant Representations) architecture is trained on this data. [5] This model is then refined through an active learning loop where MLMD simulations are run at different temperatures (300 K, 500 K, and 700 K) to explore configurational space. [5] Structures with the highest uncertainty in force predictions are selected to augment the training set, progressively improving the model's accuracy and generalizability. [5] After approximately 40 iterations, the final dataset comprises about 16,000 structures. [5]

Step 2: Dipole Moment Model Training: A separate ML model, also based on MACE, is specifically trained to predict molecular dipole moments, which are crucial for computing the IR absorption intensity. [5] This specialization ensures accurate prediction of both peak positions and amplitudes in the final spectrum. [5]

Step 3: Machine Learning-Assisted Molecular Dynamics (MLMD): The refined MLIP from Step 1 is used to run extensive MD simulations, generating trajectories that naturally include anharmonic effects. [5] These simulations are orders of magnitude faster than comparable AIMD. [5]

Step 4: IR Spectrum Calculation: Dipole moments are predicted for each structure along the MLMD trajectory using the model from Step 2. [5] The IR spectrum is then derived by computing the Fourier transform of the dipole moment autocorrelation function. [5]

Active Learning Methodology

The active learning cycle is the cornerstone of the PALIRS framework, ensuring computational efficiency and model robustness.

Active Learning Algorithm and Implementation

The active learning process strategically selects the most informative data points for DFT labeling, minimizing computational cost while maximizing model performance. [5] The detailed logical flow of this cycle is as follows: