Advancing Scoring Functions in Molecular Docking: From Foundational Principles to Machine Learning and Robust Validation

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of structure-based drug design, yet the accuracy of its predictions hinges critically on the performance of scoring functions.

Advancing Scoring Functions in Molecular Docking: From Foundational Principles to Machine Learning and Robust Validation

Abstract

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of structure-based drug design, yet the accuracy of its predictions hinges critically on the performance of scoring functions. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state and emerging trends in improving these functions. We begin by exploring the foundational principles and inherent challenges of traditional scoring methods. The discussion then progresses to modern methodological advances, with a particular focus on the integration of machine learning and deep learning, which are revolutionizing the field by offering improved accuracy and robustness. We provide a practical guide for troubleshooting and optimization, addressing common pitfalls and strategies for system-specific refinement. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of classical and modern scoring functions, underscoring the critical importance of rigorous validation and consensus approaches for reliable application in drug discovery. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the predictive power of their computational workflows.

The Foundation of Scoring Functions: Principles, Types, and Core Challenges

The Core Concept: What is a Scoring Function?

In the fields of computational chemistry and molecular modelling, a scoring function is a mathematical function used to approximately predict the binding affinity between two molecules after they have been docked [1]. Most commonly, one molecule is a small organic compound (a drug candidate) and the other is its biological target, such as a protein receptor [1].

The primary goal of a scoring function is to score and rank different ligand poses. It does this by estimating a quantity related to the change in Gibbs free energy of binding (usually in kcal/mol), where a more negative score typically indicates a more favorable binding interaction [1] [2].

The Critical Role in Docking Accuracy

Scoring functions are the decision-making engine in molecular docking simulations, and their accuracy is critical for three key applications in structure-based drug design [2]:

- Binding Mode Prediction: Given a protein target, molecular docking generates hundreds of thousands of potential ligand binding orientations (poses). The scoring function evaluates the binding tightness of each complex and ranks them. An ideal function ranks the experimentally determined, correct binding mode the highest [2].

- Virtual Screening: This is perhaps the most important application in drug discovery. When searching a large database of ligands, a reliable scoring function must rank known binders highly to identify potential drug hits efficiently, saving enormous experimental time and cost [2] [3].

- Binding Affinity Prediction: During lead optimization, an accurate scoring function can predict the absolute binding affinity between a protein and modified ligands. This helps guide chemists to improve the tightness of binding before synthesizing compounds [2].

Without accurate and efficient scoring functions to differentiate between native and non-native binding complexes, the practical success of molecular docking cannot be guaranteed [3].

A Researcher's Toolkit: Classes of Scoring Functions

Scoring functions can be broadly grouped into four categories, each with its own foundations, strengths, and weaknesses [1] [4] [3]. The table below summarizes these key classes.

| Type | Foundation | Key Features | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force-Field-Based [1] [2] [4] | Principles of physics and classical mechanics. | Estimates affinity by summing intermolecular van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. Often includes strain energy and sometimes desolvation penalties. | DOCK, AutoDock, GOLD |

| Empirical [1] [2] [4] | Linear regression fitted to experimental binding affinity data. | Sums weighted energy terms counting hydrophobic contacts, hydrogen bonds, and rotatable bonds immobilized. | Glide, ChemScore, LUDI |

| Knowledge-Based [1] [4] [3] | Statistical analysis of intermolecular contacts in structural databases. | Derives "potentials of mean force" based on the frequency of atom-atom contacts compared to a random distribution. | ITScore, PMF, DrugScore |

| Machine-Learning-Based [1] [4] [3] | Algorithms that learn the relationship between complex structural features and binding affinity. | Does not assume a predetermined functional form; infers complex relationships directly from large datasets. | ΔVina RF20, NNScore, various deep learning models |

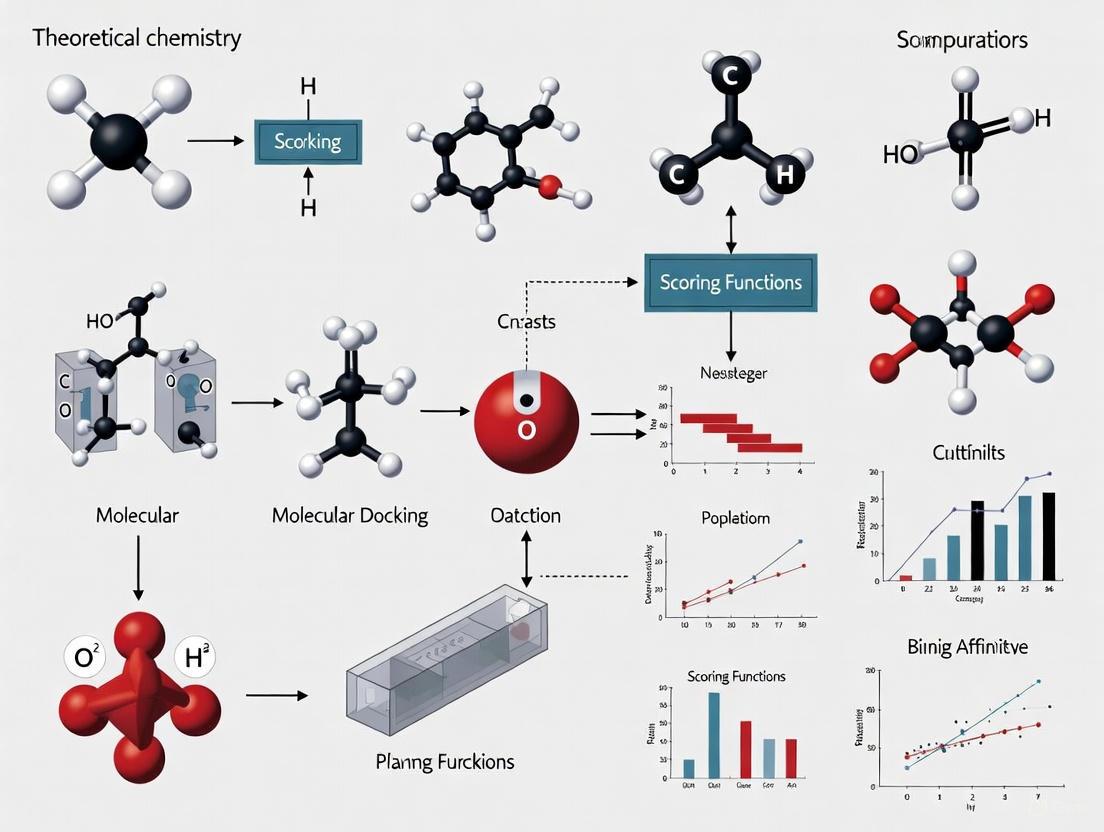

Workflow: How Scoring Integrates into Molecular Docking

The diagram below illustrates the typical docking workflow and where the scoring function plays its critical role. The process involves generating multiple potential binding poses and then using the scoring function to identify the most likely ones.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scoring Function Issues

Issue 1: Failure to Predict the Correct Binding Pose

- Problem: The top-ranked pose has a high Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) from the experimentally determined structure.

- Solution:

- Check for incomplete sampling: Ensure the docking algorithm generated a sufficient number of poses to cover the conformational space of the ligand.

- Try a consensus approach: Use multiple scoring functions from different classes (e.g., one force-field and one knowledge-based). If they all agree on a pose, confidence in that pose increases [1].

- Consider induced fit: If the protein binding site is rigid, it might not accommodate the ligand. Use an Induced Fit Docking (IFD) protocol, which allows side-chain and backbone flexibility to better fit the ligand [5].

Issue 2: Poor Correlation Between Score and Experimental Affinity

- Problem: The scoring function ranks a series of known ligands in an order that does not match their experimental binding affinities.

- Solution:

- Understand scoring function bias: Different functions have inherent biases. For example, force-field functions can be biased toward highly charged ligands if desolvation effects are not properly accounted for [2] [6].

- Use a target-specific function: If enough data is available, machine-learning scoring functions can be retrained or optimized for a specific protein target, often outperforming general-purpose functions [1] [7].

- Post-process with advanced methods: Re-score your top poses with more rigorous but computationally expensive methods like MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA, which better account for solvation effects [1] [2].

Issue 3: Ineffective Enrichment in Virtual Screening

- Problem: Known active compounds are not highly ranked when screening a large database mixed with decoys.

- Solution:

- Verify the function's suitability: Not all scoring functions are equally good for virtual screening. Consult benchmarks (like those in [3]) to choose a function known for good enrichment performance.

- Inspect the physical reasonableness of the top-ranked poses and hits. Ensure key interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic enclosure) are present [5].

- Apply constraints: Use docking constraints to require the formation of key interactions (e.g., a hydrogen bond to a specific residue) to ensure top-ranked hits make chemical sense [5].

| Resource Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools [2] [3] [5] | DOCK, AutoDock, Glide, GOLD | Molecular docking suites that integrate various sampling algorithms and scoring functions. |

| RosettaDock, HADDOCK, ZRANK2 | Specialized tools often used for protein-protein docking and scoring. | |

| Data & Benchmarks [2] [3] | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary source of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes for training and testing. |

| CASF Benchmarks | Curated datasets like CASF-2016 used to objectively evaluate the performance of scoring functions [6]. | |

| Computational Methods [1] [2] [5] | MM/GBSA, MM/PBSA | More advanced, post-docking methods to refine binding affinity predictions by estimating solvation energies. |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | A potentially more reliable but computationally very demanding alternative to scoring functions [1]. | |

| Induced Fit Docking (IFD) | Protocol that accounts for protein flexibility upon ligand binding. |

In the realm of computational drug discovery, molecular docking serves as a cornerstone technique for predicting how small molecules interact with biological targets. The accuracy of these simulations hinges critically on scoring functions—mathematical models used to predict the binding affinity between two molecules after they have been docked [1]. A perfect scoring function would precisely predict the binding free energy, allowing researchers to reliably identify potential drug candidates from thousands of compounds [8] [9]. Despite decades of development, creating a scoring function that is both accurate and efficient remains a significant challenge, directly impacting the success rate of structure-based drug design [8] [10]. This technical guide explores the taxonomy of modern scoring functions, providing researchers with a framework for selecting, troubleshooting, and applying these critical tools in their molecular docking experiments.

Classification of Scoring Functions

Scoring functions can be broadly categorized into four distinct classes based on their underlying methodology: physics-based, empirical, knowledge-based, and machine learning approaches [8] [1]. Each class operates on different principles and offers unique advantages and limitations.

Comparative Analysis of Scoring Function Classes

Table 1: Taxonomy and characteristics of major scoring function classes

| Class | Fundamental Principle | Key Components/Descriptors | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Based | Summation of non-covalent intermolecular forces [1] | Van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, implicit solvation models [8] [10] | Strong theoretical foundation, transferable across systems [1] | Computationally expensive, often requires explicit solvation for accuracy [8] |

| Empirical | Linear regression fitted to experimental binding data [1] | Hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, rotatable bonds, desolvation effects [8] [1] | Fast computation, simplified energy terms [8] [1] | Limited by training data quality, potential overfitting [1] |

| Knowledge-Based | Statistical potentials derived from structural databases [1] | Pairwise atom contact frequencies from PDB/CSD [9] [1] | Good balance of speed and accuracy, implicitly captures complex effects [8] [9] | Dependent on database completeness, less interpretable [1] |

| Machine Learning | Non-linear models trained on complex structural and interaction data [1] [10] | Fingerprints, structural features, energy terms, surface properties [9] [10] | Superior accuracy with sufficient data, can model complex relationships [1] [11] | Black box nature, data hunger, generalization concerns [8] [11] |

Scoring Function Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for selecting appropriate scoring functions based on research objectives and available resources:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Scoring Function Troubleshooting

Q1: Why does my docking simulation yield unrealistic binding poses with high scores?

This common issue often stems from limitations in the scoring function itself. Possible causes and solutions include:

- Insufficient electrostatics handling: Physics-based functions may poorly model polar interactions without explicit solvent. Consider switching to functions with better implicit solvation models or using molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) for refinement [1] [10].

- Inadequate entropy consideration: Many empirical functions underestimate the entropic penalty of immobilizing rotatable bonds. Look for functions that explicitly account for conformational entropy, such as DockTScore's improved torsional entropy term [10].

- Van der Waals over-penalization: Some functions are overly sensitive to minor atomic clashes. Knowledge-based functions like AP-PISA may offer more balanced treatment of steric interactions [8].

Q2: How can I improve binding affinity prediction when my current scoring function correlates poorly with experimental data?

Poor correlation with experimental binding affinities indicates a fundamental mismatch between the scoring function and your target system:

- Target-specific retraining: For machine learning functions, retrain on target-specific data if available. Studies show target-specific functions significantly outperform general ones for proteases and protein-protein interactions [10].

- Function combination: Implement consensus scoring by combining complementary functions. For example, pair a physics-based function (strong theoretical basis) with a knowledge-based function (implicit statistical knowledge) [1].

- Descriptor enhancement: Incorporate additional physicochemical descriptors. Recent research shows that adding ligand and protein fingerprints to knowledge-based potentials (PMF scores) improves correlation to R=0.79 [9].

Q3: What are the best practices for applying machine learning scoring functions to novel target classes?

ML functions face generalization challenges with novel targets. Mitigation strategies include:

- Feature engineering: Prioritize physics-inspired descriptors (solvation terms, lipophilic interactions) over purely structural features to improve transferability [10].

- Data augmentation: Incorporate synthetic training data or use transfer learning from larger, diverse datasets before fine-tuning on limited target-specific data [11].

- Hybrid approaches: Consider hybrid methods like Interformer that combine traditional conformational searches with AI-driven scoring to balance innovation with reliability [11].

- Validation rigor: Always validate on external test sets with adequate structural diversity, and use tools like PoseBusters to check physical plausibility beyond just RMSD metrics [11].

Q4: How do I address the computational expense of physics-based scoring functions for virtual screening?

While physics-based functions offer theoretical advantages, their computational cost can be prohibitive for large-scale screening:

- Multi-stage filtering: Implement a hierarchical protocol where fast empirical or knowledge-based functions pre-screen candidates before detailed physics-based evaluation [8].

- Implicit solvation: Replace explicit solvent models with generalized Born (GB) or Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) methods to maintain solvation effects at reduced cost [1].

- Hardware acceleration: Utilize GPU-accelerated molecular dynamics packages or specialized hardware to dramatically improve throughput [10].

Experimental Protocols: Implementation and Validation

Protocol: Benchmarking Scoring Function Performance

Purpose: Systematically evaluate and compare multiple scoring functions on specific target systems to identify the optimal function for a research project.

Materials and Methods:

Dataset Curation:

- Select 50-100 diverse protein-ligand complexes with experimentally determined binding affinities from PDBBind [10].

- Ensure structural diversity across different protein families and ligand chemotypes.

- Divide into training (75%) and test (25%) sets, maintaining representative affinity ranges in both sets.

Structure Preparation:

- Process protein structures using Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger) or similar tools: add hydrogens, assign protonation states using PROPKA, optimize hydrogen bonding, and remove crystallographic waters [10].

- Prepare ligands using standardized protocols: generate 3D coordinates, assign atomic charges (MMFF94S or AM1-BCC), and minimize structures [12] [13].

Docking and Scoring:

- Generate binding poses using multiple docking algorithms (Glide SP, AutoDock Vina, etc.) to decouple pose generation from scoring [11].

- Score each complex with at least two functions from each major class (physics-based, empirical, knowledge-based, ML).

- For ML functions, follow proper training protocols using only training set data.

Performance Metrics:

Protocol: Developing Target-Specific Machine Learning Scoring Functions

Purpose: Create customized scoring functions optimized for specific protein targets or families when general functions show limited performance.

Materials and Methods:

Feature Engineering:

- Compute physics-based descriptors: MMFF94S van der Waals and electrostatic energy terms [10].

- Calculate solvation and lipophilic interaction terms using GB/SA models [10].

- Generate ligand fingerprints (ECFP, MACCS keys) and protein fingerprints for structural binding site characterization [9].

- Include entropic terms accounting for rotatable bond immobilization [10].

Model Training:

- Employ multiple algorithms: Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) for interpretability, Support Vector Machine (SVM) for nonlinear patterns, and Random Forest/LightGBM for complex relationships [9] [10].

- Implement rigorous cross-validation (5-10 fold) to optimize hyperparameters and prevent overfitting.

- Use regularization techniques (LASSO) for feature selection in high-dimensional descriptor spaces [9].

Validation:

- Test on hold-out validation sets not used during training.

- Compare against established general scoring functions as baselines.

- Evaluate physical plausibility using PoseBusters or similar geometric validation tools [11].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential resources for scoring function development and application

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Functions | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Scoring Functions | FireDock, ZRANK2, PyDock, HADDOCK [8] | Protein-protein docking | Combination of energy terms, solvent accessibility, interface propensities |

| Machine Learning Platforms | DockTScore, KarmaDock, QuickBind [10] [11] | Binding affinity prediction | LightGBM, LASSO, SVM algorithms with physics-based descriptors |

| Benchmark Datasets | PDBBind, DUD-E, Astex Diverse Set [10] [11] | Method validation | Curated complexes with experimental affinities, decoy compounds |

| Structure Preparation | Protein Preparation Wizard, MzDOCK, AutoDock Tools [12] [13] | Pre-docking processing | Hydrogen addition, protonation state assignment, charge assignment |

| Validation Tools | PoseBusters, PLIP [13] [11] | Result assessment | Geometric plausibility, interaction profiling |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Machine Learning Scoring Function Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for developing and applying machine learning-based scoring functions:

Emerging Trends and Methodological Considerations

The field of scoring functions is rapidly evolving, with several promising directions:

Hybrid methodologies that combine the physical interpretability of classical approaches with the pattern recognition power of deep learning are showing particular promise. The DockTScore framework exemplifies this trend by integrating optimized MMFF94S force-field terms with machine learning regression [10].

Diffusion models for generative docking have demonstrated superior pose prediction accuracy (exceeding 70% success rates on benchmark sets), though they still struggle with physical plausibility in many cases [11].

Generalization challenges remain significant for all scoring function types, particularly when encountering novel protein binding pockets. Performance can drop substantially on "out-of-distribution" targets not represented in training data [8] [11].

Multi-objective optimization that simultaneously considers pose accuracy, physical plausibility, interaction recovery, and screening efficacy is becoming the standard for comprehensive evaluation, moving beyond single metrics like RMSD [11].

When selecting scoring functions for specific applications, researchers should consider the trade-offs between different approaches. Traditional physics-based and empirical methods generally offer greater physical plausibility and reliability (PB-valid rates >94% for Glide SP), while machine learning methods can provide superior screening enrichment when sufficient target-specific training data is available [1] [11]. The optimal choice ultimately depends on the specific research context, available computational resources, and validation capabilities.

Scoring functions are computational models at the heart of molecular docking. They predict the binding affinity between a ligand and a protein target, which is crucial for virtual screening in drug discovery [7] [14]. Despite their importance, accurately predicting true binding affinity remains a significant challenge, creating a gap between computational predictions and experimental results [14].

Categories of Scoring Functions

Scoring functions can be broadly divided into four main categories, each with distinct advantages and limitations [3].

Table 1: Categories of Scoring Functions in Molecular Docking

| Category | Description | Key Features | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Based | Calculate binding energy based on physical force fields. | Sum of Van der Waals, electrostatic interactions; can include solvation effects. High computational cost [3]. | Force Field methods [3] |

| Empirical-Based | Estimate binding affinity as a weighted sum of energy terms. | Trained on experimental data; faster computation than physics-based methods [3]. | Linear regression models, FireDock, RosettaDock, ZRANK2 [3] |

| Knowledge-Based | Use statistical potentials from known protein-ligand structures. | Distance-dependent atom-pair potentials; balance of accuracy and speed [14] [3]. | Statistical potential functions, AP-PISA, CP-PIE, SIPPER [3] |

| Machine Learning (ML)/Deep Learning (DL) | Learn complex mapping from structural/interface features to affinity. | Can model non-linear relationships; performance depends heavily on training data quality [15] [3]. | Dense Neural Networks, Convolutional NNs, Graph NNs, Random Forest [15] [3] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my docking software correctly identify the binding pose but fail to predict the accurate binding affinity?

This is a common issue stemming from the fundamental difference between "docking power" (identifying the correct pose) and "scoring power" (predicting binding affinity) [14]. Scoring functions are often optimized for pose identification and virtual screening rather than for providing a precise thermodynamic measurement of binding. The simplifications inherent in most scoring functions—such as treating the protein as rigid, providing a poor description of solvent effects, or neglecting true system dynamics—are key reasons for this failure in accurate affinity prediction [14].

Q2: What are "horizontal" vs. "vertical" tests, and why does my model's performance drop in vertical tests?

This performance drop highlights a critical challenge: the generalizability of scoring functions.

- Horizontal Tests: The model is trained and tested on different ligands for the same set of proteins. This is a less stringent benchmark [15].

- Vertical Tests: The model is evaluated on proteins that were not present in the training set [15].

A significant performance suppression when moving from horizontal to vertical tests indicates that the model has likely learned patterns specific to the proteins in the training set, rather than the underlying physical principles of binding. This is often a sign of overfitting or hidden biases in the training data [15].

Q3: How can I account for the role of water in my docking experiments?

Water plays a critical role in binding but is neglected by most docking programs due to its computational complexity [14]. To address this:

- Check for explicit water options: Some modern docking programs now allow for the inclusion of individual, key water molecules in the binding site during pose generation and evaluation [14].

- Post-docking analysis: Use more computationally intensive methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study the stability of the protein-ligand complex and its hydration network after docking [16]. For example, one study used MD simulations to validate the stability of complexes formed between curcumin-coated nanoparticles and mucin proteins [16].

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Docking and Scoring Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Poor correlation between predicted and experimental binding affinity | • Simplifications in scoring function (rigid protein, poor solvent model) [14].• Overfitting on training data [7].• Incorrect protonation/tautomeric states of ligand or protein [10]. | • Use ensemble docking to account for protein flexibility [14].• Apply post-processing with MD simulations [16].• Carefully prepare structures, assigning correct protonation states [10]. |

| Model performs well in training but poorly on new protein targets | • Lack of generalizability (model is too specific to training set proteins) [15].• Hidden biases in the training data [7]. | • Employ more stringent "vertical" testing during validation [15].• Explore hybrid or physics-based terms to improve transferability [7] [10].• Consider developing a target-specific scoring function if data is available [15]. |

| Inability to distinguish active binders from inactive compounds | • Limitations in the scoring function's "screening power" [14].• Inadequate pose generation [14]. | • Use a consensus scoring approach from different programs.• Ensure the docking protocol can successfully reproduce known experimental poses (e.g., from PDB) for your target. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for Developing a Machine Learning-Based Scoring Function

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating an ML-based SF, as explored in recent research [15] [10].

Data Curation

- Source your data: Obtain high-quality protein-ligand complexes from databases like PDBBind [10] or BindingDB [15]. For the PDBBind database, the "refined set" is often used for training, while the "core set" is reserved for final benchmarking [10].

- Curate structures: Manually check and prepare structures. This includes adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation and tautomeric states for binding site residues and ligands using tools like MOE or Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard, and removing structural inconsistencies [15] [10].

- Define the affinity value: Use experimental binding affinity data (e.g., Kd, Ki) and often convert it to pKd (pKd = -log10 Kd) for model training [15].

Feature Engineering

Model Training & Validation

- Split data strategically: Divide the dataset into training and test sets. Crucially, perform a vertical split, ensuring that all complexes of a given protein target are entirely contained within either the training or the test set. This tests the model's generalizability to new targets [15].

- Select ML algorithm: Train models such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SMOReg), or Dense Neural Networks (FCNN) to predict the binding affinity from the input features [15] [10].

- Evaluate performance: Use metrics like Pearson correlation coefficient (Rp) between predicted and experimental affinities. Assess different "powers": scoring power, ranking power, and screening power [14].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Scoring Function Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Database | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Repositories | PDBBind [15] [10] | A central database providing a large collection of protein-ligand complexes with experimentally measured binding affinity data, essential for training and testing scoring functions. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [15] [16] | The single worldwide repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, providing the initial coordinates for docking studies. | |

| BindingDB [15] | A public database of measured binding affinities, focusing primarily on interactions between drug-like molecules and protein targets. | |

| Software & Docking Engines | MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [15] | A software platform that provides an integrated suite of applications for molecular modeling, including structure preparation and docking capabilities (e.g., GOLD docking engine). |

| GOLD (Genetic Optimization for Ligand Docking) [15] | A widely used docking engine that employs a genetic algorithm to explore ligand conformational flexibility. | |

| Glide, AutoDock, Surflex-Dock [14] | Other popular molecular docking programs that use various sampling algorithms and scoring functions. | |

| Specialized Analysis & Simulation | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations [14] [16] | Used to study the stability and dynamics of docked complexes over time, providing insights that static docking cannot, such as the role of water and flexibility. |

| CABS-flex [16] | A tool for fast protein flexibility simulations, useful for analyzing dynamics and fluctuations in protein-ligand complexes. | |

| SwissADME, ProTox-III [16] | Web servers for predicting the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion (ADME) and toxicity properties of potential drug molecules. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my docking poses look correct but have a poor correlation with experimental binding affinity? This common issue often stems from the inadequate treatment of solvation and entropy in scoring functions. Many functions use simplified, static models for water and entropy, failing to capture the dynamic, energetic contributions of water displacement or the entropic penalty of restricting flexible ligands and protein side chains upon binding. This leads to accurate pose prediction but inaccurate affinity ranking [17] [18].

Q2: My docking run failed to reproduce a known binding pose from a crystal structure. What is the most likely cause? This is frequently a problem of receptor flexibility. If you are using an apo (unbound) structure or a receptor structure crystallized with a different ligand, the binding site geometry may be incompatible. This is known as the cross-docking problem [17] [19]. Critical side chains or backbone segments may be in a different conformation, blocking the correct binding mode.

Q3: What is the difference between induced fit and conformational selection, and why does it matter for docking? Both are models for how ligands bind to proteins. Induced fit suggests the ligand forces the protein into a new conformation upon binding. Conformational selection proposes the protein naturally samples multiple states, and the ligand selectively binds and stabilizes one of them [17] [20]. For docking, the practical implication is that you must ensure your computational method can either simulate the induced structural change or you provide an ensemble of protein structures that represents the various conformational states the protein can adopt [18].

Q4: How can I identify potential allosteric binding sites on my target protein? Allosteric sites are often transient or cryptic, meaning they are not visible in static crystal structures. To identify them, you need to account for full protein flexibility. Methods include:

- Running long molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to observe pocket opening dynamically [18].

- Using specialized algorithms like TRAPP or SWISH that analyze protein dynamics to predict transient pockets [20].

- Employing new deep learning tools like DynamicBind, which uses geometric diffusion networks to model backbone and sidechain flexibility and reveal cryptic pockets [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Receptor Flexibility

Problem: Docking fails when using a protein structure that is not pre-organized for the specific ligand (e.g., apo-state or cross-docking).

Solution: Utilize methods that incorporate protein flexibility.

Method A: Ensemble Docking

- Description: Dock your ligand library against a collection of multiple protein conformations instead of a single rigid structure [18].

- Protocol: The Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS)

- Generate an Ensemble: Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to sample the protein's conformational landscape. The protein can be simulated in its apo state or with a reference ligand bound.

- Cluster the Trajectory: Cluster the MD snapshots based on structural similarity (e.g., using RMSD of the binding site residues) to select a non-redundant set of representative conformations.

- Dock to the Ensemble: Perform docking calculations against each representative structure in the ensemble.

- Score the Results: Rank compounds based on their best score across the ensemble or a score weighted by the population of each conformation [18].

Method B: Induced Fit Docking (IFD)

- Description: A protocol that iteratively allows the protein binding site to adjust to the ligand.

- Protocol:

- Initial Docking: Dock the ligand into the rigid receptor with softened van der Waals potentials to allow minor clashes.

- Refinement: Select the top poses and use a more detailed method (e.g., energy minimization or side-chain prediction) to optimize the structure of the protein residues within a certain range of the ligand.

- Final Docking: Re-dock the ligand into the now-refined, flexible binding site to generate the final poses [18].

Method C: Deep Learning for Flexible Docking

- Description: Use emerging DL models that natively handle protein flexibility.

- Protocol:

- Model Selection: Choose a DL docking tool designed for flexibility, such as FlexPose (for end-to-end flexible modeling) or DynamicBind (for revealing cryptic pockets) [19].

- Input Preparation: Provide the protein structure (apo or holo) and ligand information.

- Pose Prediction: The model directly outputs the predicted complex structure, accounting for conformational changes in both molecules [19].

Performance Comparison of Docking Methods Handling Flexibility:

| Method Category | Example Software | Key Strength | Key Weakness | Typical Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2 Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Receptor | AutoDock Vina | Computationally fast, simple setup | Fails with major conformational changes | Varies widely (50-75% for simple cases) [17] |

| Ensurembling | RCS with MD | Accounts for full protein dynamics | Computationally very expensive | Highly dependent on ensemble quality [18] |

| Induced Fit | GLIDE IFD | Good for local sidechain adjustments | Limited for large backbone motions | Improved for cross-docking tasks [18] |

| Deep Learning | SurfDock, FlexPose | High speed, good pose accuracy | Can produce steric clashes; generalizability issues [11] | ~77% (PoseBusters set) [11] |

Issue 2: Incorporating Solvation and Entropy Effects

Problem: Scoring functions fail to rank compounds by their true binding affinity because they neglect the energetics of water and entropy.

Solution: Employ post-docking refinement and scoring with methods that explicitly or implicitly model these effects.

Method A: Explicit Solvent MD with Free Energy Calculations

- Description: The most rigorous but computationally demanding method. It involves running MD simulations of the complex, protein, and ligand in explicit water, then using methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to calculate binding free energies.

- Protocol:

- System Setup: Place the docked pose in a box of explicit water molecules and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Equilibration: Run MD simulations to equilibrate the temperature and pressure of the system.

- Production Run: Perform extensive MD sampling for the complex, ligand in solvent, and protein in solvent.

- Free Energy Analysis: Use FEP or TI to compute the binding free energy, which inherently includes entropic and solvation contributions [18].

Method B: Implicit Solvent Models and Enhanced Sampling

- Description: A faster alternative that replaces explicit water with a continuous dielectric medium. Combined with enhanced sampling algorithms, it can provide improved affinity estimates.

- Protocol:

- Refinement: Perform energy minimization or short MD simulations of the top docked poses using an implicit solvent model (e.g., Generalized Born).

- Enhanced Sampling: Apply techniques like Accelerated MD (aMD) to more efficiently sample conformational states and improve entropy estimates.

- Re-scoring: Calculate the binding energy using the MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA method, which approximates solvation and provides a better correlation with experiment than standard docking scores [18].

Quantitative Impact of Advanced Sampling on Binding Affinity Prediction:

| Computational Method | Solvation Treatment | Entropy Treatment | Computational Cost | Typical Correlation (R²) with Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Docking Score | Implicit or knowledge-based | Very limited (e.g., buried surface area) | Low | Low (0.0 - 0.4) [17] [21] |

| MM/GBSA | Implicit (Generalized Born) | Can be estimated via normal mode analysis | Medium | Medium ( ~0.5, system-dependent) |

| Explicit Solvent FEP/MD | Explicit water molecules | Included via full conformational sampling | Very High | High (can exceed 0.7-0.8 for congeneric series) [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms over time, used to generate conformational ensembles for ensemble docking or to run explicit solvent free energy calculations [18]. |

| Docking Software with Flexibility (e.g., GLIDE IFD, RosettaLigand, AutoDock) | Provides algorithms to account for protein side-chain or backbone flexibility during the docking process itself [18]. |

| Deep Learning Docking Models (e.g., DiffDock, FlexPose, DynamicBind) | Uses trained neural networks to predict the bound structure of protein-ligand complexes, with some models capable of handling protein flexibility directly [19] [11]. |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Software | Performs rigorous, physics-based calculations to predict relative binding free energies, directly accounting for solvation and entropy effects [18]. |

| MM/GBSA Scripts/Tools | Provides a post-docking method to re-score poses by estimating binding free energies using molecular mechanics combined with implicit solvation models [18]. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Flexible Docking Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: Solvation & Entropy Correction Protocol

Methodological Breakthroughs: Leveraging Machine Learning and Advanced Algorithms

The Rise of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Scoring Function Development

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of ML-based scoring functions over traditional methods? ML-based scoring functions learn complex, non-linear relationships between protein-ligand structural features and binding affinity from large datasets, moving beyond the simplified linear approximations often used in traditional empirical or physics-based functions [22]. This allows them to achieve superior performance in pose prediction and binding affinity ranking, often at a fraction of the computational cost of more rigorous methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [23].

FAQ 2: Why does my model perform well on benchmarks but poorly on my own congeneric series? This is a classic out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization problem [23]. Benchmarks like CASF often contain biases, and models can memorize ligand-specific features or protein-specific environments from their training data. When faced with a novel chemical series or protein conformation, their performance drops. Using benchmarks designed to penalize memorization and employing data augmentation strategies can improve real-world performance.

FAQ 3: My deep learning model predicts poses with incorrect bond lengths or angles. What is the issue? Early deep learning docking models like EquiBind were sometimes criticized for producing physically unrealistic structures [19]. This occurs when the model architecture or training data does not adequately incorporate physical constraints. Newer approaches, such as diffusion models (DiffDock) and methods that use molecular mechanics force fields for refinement, are explicitly designed to address this issue by generating more plausible molecular geometries [19].

FAQ 4: How can I account for protein flexibility with ML-based docking? Most traditional and early ML docking methods treat the protein as rigid, which is a significant limitation [19]. Emerging approaches are directly addressing this challenge. Methods like FlexPose enable end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes, while others, such as DynamicBind, use equivariant geometric diffusion networks to model backbone and sidechain flexibility, even revealing transient "cryptic" pockets [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Pose Prediction Accuracy on a New Target

Problem: After training a general-purpose model, you find its pose prediction accuracy is low for your specific protein target of interest.

Solution:

- Verify Data Quality: Ensure your input protein structure is prepared correctly. For apo-docking (using an unbound structure), be aware that performance may suffer due to induced fit effects [19].

- Employ a Hybrid Approach: Use a DL model for initial binding site identification or pose generation, then refine the top-ranked poses using a traditional docking scoring function with a more rigorous search algorithm [19]. This leverages the strengths of both approaches.

- Utilize Consensus Scoring: Rank poses based on the consensus of multiple scoring functions, including both ML-based and classical methods, to improve the robustness of predictions [24].

Issue 2: Model Fails to Rank Congeneric Ligands Correctly

Problem: Your model cannot correctly predict the relative binding affinity for a series of closely related ligands, a critical task in lead optimization.

Solution:

- Incorporate Augmented Data: Augment your training set with synthetically generated data. As demonstrated by AEV-PLIG, using data from template-based modeling or molecular docking can significantly improve ranking performance on congeneric series [23].

- Leverage FEP for Fine-Tuning: Use a small number of accurate but expensive FEP calculations on key compounds to validate and potentially fine-tune your ML model's predictions for your specific series, helping to bridge the accuracy gap [23].

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that your training and test sets are split by protein family or ligand scaffold to avoid artificial inflation of performance metrics and get a realistic estimate of your model's ranking power [25].

Issue 3: Data Scarcity for Training a Robust Model

Problem: You lack sufficient high-quality protein-ligand complex structures with binding affinity data to train your own model effectively.

Solution:

- Use Pre-trained Models: Start with models that have been pre-trained on large, public databases like PDBbind or BindingDB [23] [22]. Fine-tune these models on your smaller, target-specific dataset if available.

- Apply Transfer Learning: Pre-train your model on a related task with abundant data, such as predicting the likelihood of atom-atom contacts, before fine-tuning on the smaller binding affinity dataset [22].

- Explore Data Augmentation: As implemented in models like AI-Bind, use techniques from network science and unsupervised learning to generate meaningful negative examples and learn from broader chemical and protein structure spaces without relying solely on limited binding data [26].

Performance Benchmarks and Data

The table below summarizes the performance of various ML-based scoring functions on different docking tasks, as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected ML Docking Methods

| Method | Key Architecture | Docking Task | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnina 1.0 [22] | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Redocking (defined pocket) | 73% Top1 (< 2.0 Å) | Significantly outperforms AutoDock Vina; integrated docking pipeline. |

| DiffDock [19] | SE(3)-Equivariant Graph NN + Diffusion | Blind Docking | State-of-the-art on PDBBind | High accuracy with physically plausible structures. |

| AEV-PLIG [23] | Attention-based Graph NN | Out-of-Distribution Test | PCC: 0.59, Kendall's τ: 0.42 (on FEP benchmark) | Strong performance on congeneric series using augmented data. |

| EquiBind [19] | Equivariant Graph NN | Blind Docking | Fast inference speed | Direct, one-shot prediction of binding pose. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Data Augmentation Strategy for Improved Ranking

This protocol is based on the strategy used to enhance the performance of the AEV-PLIG model [23].

Objective: To improve the correlation and ranking of binding affinity predictions for a congeneric series of ligands.

Materials:

- A set of experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data (e.g., from PDBbind).

- A congeneric series of ligands with known structural relationships.

- Molecular docking software (e.g., Gnina, AutoDock Vina).

- Template-based ligand alignment algorithm [23].

Methodology:

- Base Dataset Preparation: Curate your initial training set of high-quality experimental structures.

- Generate Augmented Structures:

- Docking-Based Augmentation: For proteins with known active ligands, dock other ligands from the same family into the binding site to generate plausible, but computationally predicted, complex structures.

- Template-Based Augmentation: Use a template-based ligand alignment algorithm to model new protein-ligand complexes by aligning ligands to similar known co-crystal structures.

- Assign Affinity Labels: Use experimental binding affinities from related compounds or predicted affinities from a baseline model to label the augmented structures. The primary goal is to teach the model the structural relationships within a congeneric series.

- Combined Training: Train your ML scoring function on the combined set of experimental and augmented data.

- Validation: Rigorously test the model on a held-out test set of experimental data for your congeneric series, ensuring the split prevents data leakage.

Protocol 2: Deploying a Hybrid Docking and Refinement Workflow

This protocol addresses the need for high-accuracy pose prediction while mitigating the risk of physically unrealistic outputs from early DL models [19] [26].

Objective: To predict a ligand's binding pose with high accuracy by combining the speed of deep learning with the reliability of classical methods.

Materials:

- A deep learning docking tool capable of blind or pocket-based docking (e.g., DiffDock, EquiBind, Gnina).

- A traditional docking program with a robust search algorithm and scoring function (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD).

- A prepared protein structure and ligand(s) of interest.

Methodology:

- Initial Pose Generation: Use the DL docking tool to generate an initial set of ligand poses (e.g., 10-20 top-ranked poses).

- Pose Selection and Preparation: Select the top N poses based on the DL model's confidence score.

- Local Refinement: Using the traditional docking software, perform a local, high-resolution docking search. This is typically done by:

- Defining a small docking box centered on the predicted pose from step 2.

- Running the traditional docking calculation with exhaustive sampling parameters to refine the pose and score it with a classical scoring function.

- Consensus Analysis: Compare the refined poses from the traditional method with the original DL predictions. A consensus pose is often more reliable.

- (Optional) Molecular Dynamics (MD) Refinement: For critical candidates, further refine the final docked pose using short MD simulations in explicit solvent to relax the complex and account for induced fit effects [26].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

ML Scoring Function Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-Based Molecular Docking

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind [25] [23] | Database | A curated database of protein-ligand complexes with experimental binding affinities. | Primary dataset for training and benchmarking structure-based ML scoring functions. |

| Gnina [22] | Software | A molecular docking tool that uses CNNs for scoring; a fork of AutoDock Vina. | Integrated docking and scoring with state-of-the-art ML performance. |

| Schrödinger Glide [5] | Software | A widely used docking program with high-performance empirical scoring (GlideScore). | Useful for hybrid workflows (pose refinement) and as a benchmark against ML methods. |

| CASF Benchmark [23] [24] | Benchmark | The "Core Set" from PDBbind used for the Critical Assessment of Scoring Functions. | Standardized benchmark to evaluate the scoring power of new ML functions. |

| OOD Test Set [23] | Benchmark | A novel benchmark designed to test out-of-distribution generalization and penalize memorization. | A more realistic assessment of a model's performance in lead optimization scenarios. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My target-specific scoring function performs well on validation data but generalizes poorly to novel chemical structures. How can I improve its extrapolation capability?

A1: This is a common challenge where models overfit to the chemical space present in the training data. Implement a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) architecture, which has demonstrated superior generalization for target-specific scoring functions. GCNs improve extrapolation by learning complex patterns of molecular-protein binding that transfer better to heterogeneous data. For targets like cGAS and kRAS, GCN-based scoring functions showed significant superiority over generic scoring functions while maintaining remarkable robustness and accuracy in determining molecular activity [21]. Ensure your training data encompasses diverse chemical scaffolds to maximize the model's exposure to varied molecular patterns.

Q2: How can I drastically accelerate the virtual screening process without significant loss of accuracy?

A2: Consider implementing Fourier-based scoring functions that leverage Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) for rapid pose optimization. These methods define scoring as cross-correlation between protein and ligand scalar fields, enabling simultaneous evaluation of numerous ligand poses. This approach can achieve translational optimization in approximately 160μs and rotational optimization in 650μs per pose—orders of magnitude faster than traditional docking. The runtime is particularly favorable for virtual screening with a common binding pocket, where protein structure processing can be amortized across multiple ligands [27]. For miRNA-protein complexes, equivariant graph neural networks have demonstrated tens of thousands of times acceleration compared to traditional molecular docking with minimal accuracy loss [28].

Q3: What are the practical trade-offs between explicitly equivariant models and non-equivariant models with data augmentation?

A3: Explicitly equivariant models (e.g., SE(3)-equivariant GNNs) guarantee correct physical behavior under rotational and translational transformations but are often more complex, difficult to train, and scale poorly. Non-equivariant models (e.g., 3D CNNs) with rotation augmentations are more flexible and easier to scale but may learn inefficient, redundant representations. Research indicates that for denoising and property prediction tasks, CNNs with augmentation can learn equivariant behavior effectively, even with limited data. However, for generative tasks, larger models and more data are required to achieve consistent outputs across rotations [29]. For critical applications requiring precise geometric correctness, explicitly equivariant models remain preferable despite implementation challenges.

Q4: How can I address the problem of physically unrealistic molecular predictions in deep learning-based docking?

A4: Physically unrealistic predictions often stem from neglecting molecular feasibility constraints during generation. Implement diffusion models that concurrently generate both atoms and bonds through explicit bond diffusion, which maintains better geometric validity than methods that only generate atom positions and later infer bonds. The DiffGui model demonstrates that integrating bond diffusion with property guidance (binding affinity, drug-likeness) during training and sampling produces molecules with more realistic bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals while maintaining high binding affinity [30]. Additionally, ensure your training data includes diverse conformational information to help the model learn physically plausible molecular geometries.

Q5: What strategies can improve meta-generalization when applying graph neural processes to novel molecular targets?

A5: Meta-generalization to divergent test tasks remains challenging due to the heterogeneity of molecular functions. Implement fine-tuning strategies that adapt neural process parameters to novel tasks, which has been shown to substantially improve regression performance while maintaining well-calibrated uncertainty estimates. Graph neural processes on molecular graphs have demonstrated competitive few-shot learning performance for docking score prediction, outperforming traditional supervised learning baselines. For highly novel targets with limited structural similarity to training data, consider incorporating additional protein descriptors or interaction fingerprints to bridge the generalization gap [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Pose Prediction Accuracy Despite High Affinity Correlation

Symptoms: Your model accurately ranks compounds by binding affinity but fails to identify correct binding geometries.

Diagnosis: This indicates the model is learning ligand-based or protein-based patterns rather than genuine interaction physics—a known limitation called "memorization" in GNNs [32].

Solution: Implement pose ensemble graph neural networks that leverage multiple docking poses rather than single conformations.

Table 1: DBX2 Node Features for Pose Ensemble Modeling

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | Instance identifier | Encodes methodological bias |

| Energetic | Original docking score, Rescoring scores from multiple functions | Captures consensus energy information |

| Structural | Categorical pose descriptors | Represents conformational diversity |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Generate 100-140 diverse poses per compound using multiple docking programs (AutoDock, Vina, DOCK)

- Rescore all poses with multiple scoring functions (AutoDock, Vina, Gnina, DSX)

- Construct a graph where nodes represent individual poses with features from Table 1

- Implement a GraphSAGE architecture with node-level (pose likelihood) and graph-level (binding affinity) tasks

- Jointly train on both objectives using the PDBbind dataset [32]

This ensemble approach significantly improves both pose prediction and virtual screening accuracy compared to single-pose methods.

Issue 2: Inadequate Handling of Protein Flexibility

Symptoms: Model performance degrades significantly when docking to apo structures or across different conformational states.

Diagnosis: Traditional rigid docking assumptions fail to capture induced fit effects and protein dynamics [19].

Solution: Implement flexible docking approaches that model protein conformational changes.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Identify flexibility requirements: Determine if your application requires sidechain flexibility, backbone movement, or cryptic pocket prediction

- Select appropriate method:

- For local sidechain flexibility: Use coarse residue-level representations as in DiffDock

- For significant conformational changes: Implement FlexPose for end-to-end flexible modeling

- For cryptic pockets: Apply DynamicBind with equivariant geometric diffusion networks

- Training data strategy: Include both holo and apo structures in training when possible

- Cross-docking validation: Always evaluate performance on cross-docking benchmarks rather than just re-docking [19]

Table 2: Protein Flexibility Handling in Docking Tasks

| Docking Task | Description | Flexibility Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Re-docking | Dock ligand to holo conformation | Minimal; evaluates pose recovery |

| Flexible re-docking | Dock to holo with randomized sidechains | Moderate; tests robustness to local changes |

| Cross-docking | Dock to alternative conformations | High; simulates realistic docking scenarios |

| Apo-docking | Dock to unbound structures | Very high; requires induced fit modeling |

Issue 3: Low-Rate Identification of Active Compounds in Virtual Screening

Symptoms: High computational throughput but poor enrichment of true active compounds during virtual screening.

Diagnosis: Standard scoring functions may lack the precision needed to distinguish subtle interactions critical for specific targets.

Solution: Develop target-specific scoring functions using Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks (KA-GNNs).

Experimental Protocol for KA-GNN Implementation:

Data Preparation:

- Collect known active and inactive compounds for your target

- Generate 3D structures and compute molecular features

- Split data ensuring chemical diversity in training and test sets

KA-GNN Architecture:

- Replace standard MLP components in your GNN with Kolmogorov-Arnold networks

- Implement Fourier-based univariate functions in KAN layers to capture both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns

- Integrate KAN modules into all three GNN components: node embedding, message passing, and readout

Training Procedure:

- Use a multi-task loss combining pose prediction and affinity estimation

- Apply regularization techniques to prevent overfitting to limited target data

- Validate generalization on structurally diverse test compounds [33]

KA-GNNs have demonstrated consistent outperformance over conventional GNNs in both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency across multiple molecular benchmarks, with the additional benefit of improved interpretability through highlighting of chemically meaningful substructures.

Workflow Diagram: Troubleshooting Model Performance Issues

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Robust Scoring Functions

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE | Molecular representation learning | KA-GNN variants show superior performance [33] |

| Equivariant Models | SE(3)-GNN, EGNN | Geometric deep learning | Preferred for precise geometry tasks [29] |

| Ensemble Methods | Pose ensemble GNNs, DBX2 | Capturing conformational diversity | Requires multiple pose generation [32] |

| Diffusion Models | DiffDock, DiffGui | Generative pose prediction | Bond diffusion improves realism [30] |

| Scalar Field Methods | Equivariant Scalar Fields | Rapid FFT-based optimization | Ideal for high-throughput screening [27] |

| Meta-Learning | Graph Neural Processes | Few-shot learning for novel targets | Addresses data scarcity [31] |

| Benchmark Datasets | PDBbind, DOCKSTRING | Model training and validation | Ensure proper splitting to avoid bias [31] [32] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Explicit Water Handling

Problem: Inconsistent docking results when explicit water molecules are included in the binding site.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dramatic scoring changes with minimal protein movement | Over-reliance on a single, potentially unstable water molecule | Use MD simulations to identify conserved water molecules; retain only those with high occupancy [34]. |

| Ligand failing to bind in the correct pose | Critical bridging water molecule was removed during system preparation | Analyze holo crystal structures of similar complexes to identify functionally important water molecules [34]. |

| Poor correlation between computed score and experimental affinity | Scoring function misestimates the free energy cost/benefit of water displacement [34] | Employ computational methods that account for water thermodynamics, such as WaterMap or 3D-RISM [34]. |

Detailed Protocol: Identifying Conserved Water Molecules via MD Simulation

- Objective: To distinguish structurally conserved water molecules from transient ones to inform which should be included in docking.

- Procedure:

- System Setup: Place the apo protein structure in a solvation box with explicit water models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E) and neutralize the system with ions [35].

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization followed by equilibration under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles.

- Production Run: Execute an unbiased MD simulation for a sufficient timeframe (e.g., 10-100 ns) to sample water dynamics [35].

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate the occupancy of each water molecule within the binding site. Water molecules with high occupancy (e.g., >80%) over the simulation are considered conserved and strong candidates for explicit inclusion in docking [34].

Troubleshooting Ligand Conformation Stability

Problem: Predicted ligand poses exhibit unrealistic bond lengths, angles, or steric clashes.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Physically unrealistic bond lengths/angles | Deep learning model has not learned proper chemical constraints [19] | Use a hybrid approach: generate poses with a DL model (e.g., DiffDock), then refine with a physics-based method (e.g., AutoDock) [19]. |

| Ligand atom clashes with protein | Inadequate sampling of ligand's flexible torsions or protein sidechains [19] | For flexible ligands, increase the number of torsional degrees of freedom sampled during docking or use a more exhaustive search algorithm [36]. |

| Incorrect chiral center or stereochemistry | DL model generalizes poorly to unseen chemical scaffolds [19] | Always validate the stereochemistry and geometry of the top-ranked poses visually and with structure-validation tools. |

Detailed Protocol: Pose Refinement Using Physics-Based Scoring

- Objective: To improve the physical realism and geometric quality of a ligand pose generated by a fast, initial docking algorithm.

- Procedure:

- Pose Extraction: Select the top N poses (e.g., top 10) from the initial docking run, even if their geometry is imperfect.

- Local Refinement: Using a docking program with a physics-based or force-field scoring function (e.g., AutoDock Vina, GOLD), perform a local docking search. Restrict the search space to a small box around the initial predicted pose [36].

- Re-scoring: Score the refined poses using a more sophisticated, potentially slower scoring function (e.g., MM-GBSA) to obtain a better estimate of the binding affinity [34].

- Validation: Inspect the final refined pose for proper steric contacts, hydrogen bonding, and other key interactions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When is it absolutely necessary to include explicit water molecules in my docking simulation? It is critical when water molecules are known to act as bridging molecules between the protein and ligand, forming simultaneous hydrogen bonds with both. This is common in systems where ligands possess hydrogen bond donors/acceptors that perfectly match conserved water sites in the binding pocket. Displacing such a water can be energetically costly, while forming a new bridge can be beneficial [34].

Q2: My docking program has options for "flexible" sidechains. Should I use this to account for protein flexibility? While enabling sidechain flexibility can improve results, especially in cross-docking scenarios, it significantly increases computational cost and the risk of false positives. It is best used selectively. First, perform docking with a rigid protein. If the results are poor, identify sidechains near the binding site that are known to be flexible from experimental data or MD simulations and allow only those to be flexible [19].

Q3: What is the most common reason for a good-looking docked pose to have a very poor score? This often stems from a desolvation penalty. The scoring function may calculate that the energy required to displace several tightly bound water molecules from the binding site (or from the ligand) is greater than the energy gained from the new protein-ligand interactions. Check if the pose is burying polar groups that are not forming hydrogen bonds with the protein [34] [37].

Q4: How can I improve the accuracy of my virtual screening campaign for a protein target with a known flexible binding site? Consider moving beyond single-structure docking. Use an ensemble-docking approach. This involves docking your ligand library against multiple conformations of the target protein. These conformations can be sourced from:

- Multiple crystal structures (apo, holo, with different ligands).

- Snapshots from a Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation [35].

- Conformations generated by enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics [35].

Experimental Workflow & Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow that integrates the troubleshooting steps and strategies discussed above to improve scoring function performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Docking |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [35] | Software Package | A versatile package for performing Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to generate protein conformations and analyze water dynamics. |

| HADDOCK [35] | Web Server / Software | An information-driven docking platform that excels at incorporating experimental data and can handle flexibility. |

| AutoDock Vina [36] | Docking Program | A widely used, open-source docking program known for its speed and accuracy, suitable for initial pose generation. |

| PDBBind [19] | Database | A curated database of protein-ligand complexes with structural and binding affinity data, essential for training and validating scoring functions. |

| PLUMED [35] | Plugin / Library | A package that works with MD codes (like GROMACS) to implement enhanced sampling methods (e.g., metadynamics) for exploring complex conformational changes. |

| 3D-RISM [34] | Theory/Method | A statistical mechanical theory used to predict the distribution of water and ions around a solute, aiding in the identification of key hydration sites. |

| MM-GBSA/PBSA [34] | Post-Processing Method | End-point free energy calculation methods used to re-score and re-rank docked poses for a more reliable estimate of binding affinity. |

Molecular docking is a pivotal technique in computer-aided drug design that predicts how small molecule ligands interact with protein targets. The core component of any docking algorithm is its scoring function, which evaluates the quality of protein-ligand interactions to predict binding affinity and identify correct binding poses. Traditional scoring functions, such as the one implemented in AutoDock Vina, use a weighted sum of energy terms to achieve a balance between computational speed and predictive accuracy [38]. However, their performance as predictors of binding affinity is notoriously variable across different target proteins [39].

The emergence of machine learning (ML) approaches has revolutionized scoring function development. ML-based scoring functions, including those implemented in Gnina (a fork of AutoDock Vina with integrated deep learning capabilities), can capture complex, non-linear relationships in protein-ligand interaction data that traditional functions might miss [40]. This case study examines the performance of both traditional and ML-driven scoring functions, focusing on their application to both experimental crystal structures and computer-predicted poses, within the broader context of ongoing research to improve molecular docking accuracy for drug discovery.

Understanding Traditional vs. ML-Driven Scoring Functions

AutoDock Vina: The Traditional Workhorse

AutoDock Vina treats docking as a stochastic global optimization of its scoring function. Its algorithm involves multiple independent runs from random conformations, with each run comprising steps of random perturbation followed by local optimization [38]. Key characteristics of Vina's traditional scoring function include:

- United-Atom Model: The function primarily considers heavy atoms, with hydrogen positions being arbitrary in the output [38].

- Fixed Weights: The scoring function uses a common set of weights for all protein-ligand interactions [39].

- Ignored Partial Charges: Vina does not utilize user-supplied partial charges, instead handling electrostatic interactions through hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding terms [38].

Gnina and ML-Based Approaches: The New Generation

Gnina represents the evolution of docking software through integration of deep learning. As a fork of Vina's codebase, it retains Vina's search capabilities while augmenting scoring with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [40]. ML-based scoring functions fundamentally differ from traditional approaches:

- Non-Linear Modeling: ML functions can capture cooperative effects between non-covalent interactions that traditional linear models miss [39].

- Data-Driven Learning: Instead of pre-defined weights, ML models learn interaction patterns from large datasets of protein-ligand complexes [41].

- Complex Feature Representation: CNNs in Gnina can process 3D structural information directly from grid representations of protein-ligand complexes [40].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Traditional and ML-Driven Scoring Functions

| Characteristic | Traditional (AutoDock Vina) | ML-Driven (Gnina) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Empirical physical function | Data-driven patterns from complex structures |

| Interaction Model | Linear combination of terms | Non-linear, potentially capturing cooperativity |

| Adaptability | Fixed parameters | Can be retrained on new data or specific targets |

| Structural Input | Pre-calculated grid maps | 3D grid representations processed by CNNs |

| Performance Focus | Computational speed | Balanced accuracy and speed through CNN scoring tiers |

Performance Evaluation: Crystal vs. Predicted Structures

The Training Data Challenge

A critical limitation in developing robust ML scoring functions is the relatively small number of experimental protein-ligand structures compared to the data typically available in other ML domains. The PDBBind database provides only thousands of complex structures, whereas successful ML applications in other fields often utilize millions of training samples [41]. This data scarcity has prompted researchers to explore using computer-generated structures for training.

Recent studies have investigated whether ML-based scoring functions can be effectively trained using computer-generated complex structures created with docking software. These approaches can provide access to larger and more tunable databases, addressing the data scarcity problem [41].

Comparative Performance on Different Structure Types

Research directly comparing performance on experimental crystal structures versus computer-generated structures reveals important insights:

Similar Horizontal Test Performance: One study found that an artificial neural network achieved similar performance when trained on either experimental structures (from PDBBind) or computer-generated structures (created with the GOLD docking engine) [41].

Noticeable Vertical Test Suppression: The same study reported a "noticeable performance suppression" when ML scoring functions were tested on target proteins not included in the training data (vertical tests), as opposed to the less stringent horizontal tests where a protein might be present in both training and test sets [41].

Performance on Docked Poses: The

ΔLin_F9XGBscoring function, which uses a delta machine learning approach, demonstrated robust performance across different structure types, achieving Pearson correlation coefficients (R) of 0.853 for locally optimized poses, 0.839 for flexible re-docked poses, and 0.813 for ensemble docked poses [42].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Structure Types and Scoring Methods

| Scoring Function | Crystal Structures (R) | Locally Optimized Poses (R) | Flexible Re-docked Poses (R) | Ensemble Docked Poses (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Vina | Variable by target | Moderate performance | Moderate performance | Moderate performance |

| Gnina (CNN) | Improved pose prediction | Enhanced side-chain handling | Good flexibility accommodation | Dependent on training diversity |

| ΔLin_F9XGB | High correlation | 0.853 | 0.839 | 0.813 |

| Target-Specific ML | Potentially excellent | Good generalization | Varies by flexibility | Requires diverse conformational training |

Diagram 1: Performance hierarchy showing that both crystal and computer-generated structures perform well in horizontal tests, but all approaches show reduced performance in vertical tests on unseen protein targets.

Advanced ML Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Delta Machine Learning (Δ-Learning)

Delta machine learning has emerged as a powerful strategy to improve scoring function robustness. Instead of predicting absolute binding affinities directly, Δ-learning methods predict a correction term to a baseline scoring function:

- Implementation Approach: The

ΔVinaXGBandΔLin_F9XGBfunctions parameterize a correction term to the Vina or Lin_F9 scoring functions using machine learning [42]. - Advantages: This approach leverages the strengths of traditional physics-based functions while applying ML to learn the patterns that classical functions miss.

- Performance Gains: These Δ-learning scoring functions have demonstrated top-tier performance across all metrics of the CASF-2016 benchmark compared to classical scoring functions [42].

Target-Specific and Customized Scoring Functions

The performance variability of scoring functions across different protein targets has prompted development of target-specific approaches:

- The Customization Challenge: Standard scoring functions use a common set of weights for all targets, but optimal weights are actually gene family-dependent [39].

- Practical Implementation: Target-specific ML scoring functions can be trained on complexes including only one target protein, showing encouraging results depending on the protein type [41].

- Alternative Solutions: Knowledge-Guided Scoring (KGS) methods enhance performance by referencing similar complexes with known binding data, avoiding the need to build entirely new functions for each target [43].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Comparing Scoring Function Performance

To evaluate scoring function performance across different structure types, researchers have developed standardized protocols:

Data Set Curation:

Structure Preparation:

Performance Metrics:

Protocol for Developing Δ-ML Scoring Functions

The development of delta machine learning scoring functions follows a structured approach:

Training Set Construction:

Feature Engineering:

Model Training and Validation:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for developing and validating scoring functions, showing parallel processing of experimental and computer-generated structures through a shared validation pipeline against both traditional and ML scoring approaches.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Common Technical Issues and Solutions

Q: Why are my docking results different from tutorial examples even with the same structure?

A: The docking algorithm in Vina and Gnina is non-deterministic by design. Even with identical inputs, results may vary between runs due to the stochastic nature of the global optimization. For reproducible results, use the same random seed across calculations [38].

Q: Why do I get "can not open conf.txt" errors when the file exists?

A: File browsers often hide extensions, so "conf.txt" might actually be "conf.txt.txt". Check the actual filename and ensure the path is correct relative to your working directory [38].