Bayesian Validation Metrics for Computational Models: A Practical Guide for Robust Inference in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian validation metrics for researchers and professionals developing computational models in psychology, neuroscience, and drug development.

Bayesian Validation Metrics for Computational Models: A Practical Guide for Robust Inference in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian validation metrics for researchers and professionals developing computational models in psychology, neuroscience, and drug development. It covers foundational principles of Bayesian model assessment, practical methodologies for application, strategies for troubleshooting common issues like low statistical power and model misspecification, and frameworks for comparative model evaluation. By synthesizing modern Bayesian workflow practices with real-world case studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools necessary to ensure their computational models are reliable, interpretable, and fit for purpose in critical biomedical applications.

Core Principles: Why Bayesian Validation is Essential for Robust Computational Modeling

The Critical Role of Validation in the Computational Workflow

Validation is a cornerstone of robust scientific research, ensuring that computational models and workflows produce reliable, accurate, and interpretable results. Within Bayesian statistics, where models often incorporate complex hierarchical structures and are applied to high-stakes decision-making, rigorous validation is not merely beneficial but essential. It provides the critical link between abstract mathematical models and their real-world applications, establishing credibility for research findings. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, implementing a systematic validation strategy is fundamental to confirming that a computational workflow is performing as intended and that its outputs can be trusted for scientific inference and policy decisions.

The need for thorough validation is particularly acute when considering the unique challenges of Bayesian methods. These models involve intricate assumptions about priors, likelihoods, and dependence structures, and they often rely on sophisticated computational algorithms like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for inference. Without systematic validation, it is impossible to determine whether a model has been correctly implemented, whether it adequately captures the underlying data-generating process, or whether the computational sampling has converged to the true posterior distribution [1]. This article outlines a structured framework and practical protocols for validating computational workflows, with a specific emphasis on Bayesian validation metrics, providing researchers with the tools necessary to build confidence in their computational results.

Core Principles of Workflow Validation

Validation of computational workflows extends beyond simple code verification to encompass the entire analytical process. A workflow is a formal specification of data flow and execution control between components, and its instantiation with specific inputs and parameters constitutes a workflow run [2]. Validating this complex digital object requires a multi-faceted approach.

The FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) offer a foundational framework for enhancing the validation and reusability of computational workflows. Applying these principles ensures that workflows are documented, versioned, and structured in a way that facilitates independent validation and replication by other researchers [2]. For a workflow to be truly valid, it must demonstrate several key characteristics:

- Computational Correctness: The workflow executes without technical errors and produces numerically stable results.

- Statistical Robustness: The model's outputs are insensitive to minor changes in priors, initializations, or sampling procedures.

- Predictive Accuracy: The model generates predictions that correspond well with observed or held-out data.

- Domain Relevance: The workflow's outputs are interpretable and meaningful within their specific scientific context.

Adopting a Bayesian workflow perspective, where model building, inference, and criticism form an iterative cycle, is crucial for robust statistical analysis. This approach emphasizes continuous validation throughout the model development process rather than treating it as a final step before publication [3].

Key Bayesian Validation Metrics and Protocols

Validating Bayesian models requires specialized metrics and protocols that address the probabilistic nature of their outputs. The following sections detail core validation methodologies, presenting quantitative benchmarks and experimental protocols.

Coverage Diagnostics

Coverage diagnostics assess the reliability of uncertainty quantification from a Bayesian model. This metric evaluates whether posterior credible intervals contain the true parameter values at the advertised rate across repeated sampling.

Table 1: Interpretation of Coverage Diagnostic Results

| Coverage Probability | Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| ≈ Nominal Level (e.g., 0.95) | Well-calibrated uncertainty quantification | None required; model uncertainty is accurate |

| > Nominal Level | Overly conservative uncertainty intervals | Investigate prior specifications; may be too diffuse |

| < Nominal Level | Overconfident intervals; uncertainty is underestimated | Check model misspecification, likelihood, or computational convergence |

Experimental Protocol for Coverage Diagnostics:

- Data Simulation: Generate multiple synthetic datasets (e.g., N=500) from the model's data-generating process using known ground-truth parameter values.

- Model Fitting: Fit the Bayesian model to each simulated dataset, obtaining posterior distributions for all parameters of interest.

- Interval Calculation: For each parameter in each simulation, compute a 95% posterior credible interval from the quantiles of the posterior samples.

- Coverage Computation: Calculate the empirical coverage probability as the proportion of simulations in which the true parameter value falls within its calculated credible interval.

- Diagnostic Assessment: Compare the empirical coverage to the nominal level (e.g., 0.95). Significant deviations indicate issues with model specification or inference [1].

Posterior Predictive Checks

Posterior predictive checks (PPCs) evaluate how well a model's predictions match the observed data, helping to identify systematic discrepancies between the model and reality.

Table 2: Posterior Predictive Check Implementation

| Check Type | Test Quantity | Implementation Guideline | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphical Check | Visual comparison of data histograms | Overlay observed data with predictive distributions | Look for systematic differences in shape, spread, or tails |

| Numerical Discrepancy | Test statistic T(y) such as mean, variance, or extreme values | Calculate Bayesian p-value: p = Pr(T(y_rep) ≥ T(y) ∣ y) | p-values near 0.5 indicate good fit; extreme values (0.05) suggest misfit |

| Multivariate Check | Relationship between variables | Compare correlation structures in y and y_rep | Identifies missing dependencies in the model |

Experimental Protocol for Posterior Predictive Checks:

- Model Fitting: Generate posterior samples from the model using the observed data.

- Replicated Data Generation: For each posterior sample, simulate a new replicated dataset y_rep from the posterior predictive distribution.

- Discrepancy Measure Selection: Choose test quantities T(y) that capture essential features of the data relevant to the scientific question.

- Distribution Comparison: Compare the distribution of T(y_rep) to the observed T(y), using graphical methods or numerical summaries.

- Model Criticism: Identify specific aspects where simulated data systematically differ from observed data, informing model revisions [3].

MCMC Convergence Diagnostics

For models using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods, validating that sampling algorithms have converged to the target posterior distribution is essential.

Experimental Protocol for MCMC Diagnostics:

- Multiple Chain Initialization: Run multiple MCMC chains (typically 4) from dispersed starting points to assess convergence to the same distribution.

- Diagnostic Computation: Calculate the potential scale reduction factor (R̂) for all parameters of interest. R̂ should be close to 1 (typically <1.01) to indicate convergence.

- Effective Sample Size Check: Compute the effective sample size (ESS) for key parameters to ensure sufficient independent draws from the posterior (ESS > 400 per chain is often recommended).

- Trace and Autocorrelation Inspection: Visually examine trace plots for good mixing and stationarity, and check that autocorrelation drops off sufficiently fast.

- Divergence Monitoring: For Hamiltonian Monte Carlo samplers, check for divergent transitions that may indicate regions of poor approximation in the posterior [1].

Application Notes: Validation in Practice

Case Study: Validation of Organ Dose Estimation

A recent study on estimating radiation organ doses from plutonium inhalation provides a compelling example of rigorous Bayesian model validation. Researchers faced the challenge of validating dose estimates without knowing true doses, a common limitation in many applied settings. Their innovative approach used post-mortem tissue measurements as surrogate "true" values to validate probabilistic predictions from a Bayesian biokinetic model [4].

Experimental Protocol for Dose Validation:

- Data Collection: Gather historical urine bioassay data and post-mortem measurements of 239Pu in liver, skeleton, and respiratory tract tissues from former nuclear workers.

- Model Implementation: Develop a Bayesian model that incorporates parameter uncertainty in the human respiratory tract model, varying parameters like rapidly dissolved fraction (fr) and slow dissolution rate (ss) using Latin hypercube sampling.

- Intake Estimation: For each parameter realization, estimate intake using maximum likelihood fitting of the urine bioassay data.

- Prediction Generation: Predict distributions of 239Pu organ activities based on the estimated intakes.

- Validation Assessment: Compare the predicted distributions to the actual post-mortem measurements, calculating coverage probabilities for the empirical data [4].

The results were revealing: the predicted distributions failed to cover the measured values in 75% of cases for the liver and 90% for the skeleton, indicating significant model misspecification despite the sophisticated Bayesian approach. This case highlights how validation against empirical benchmarks can reveal critical limitations in even well-developed computational workflows [4].

Case Study: Validation in Computational Psychiatry

In computational psychiatry, researchers have demonstrated how Bayesian workflow validation ensures robust parameter identification in models of cognition. When fitting Hierarchical Gaussian Filter (HGF) models to behavioral data, they addressed the challenge of limited information in typical binary response data by developing novel response models that simultaneously leverage multiple data streams [3].

Experimental Protocol for Model Identifiability Validation:

- Data Simulation: Generate synthetic datasets with known ground-truth parameter values from the proposed model.

- Model Recovery: Fit the model to simulated data and assess the correlation between true and recovered parameters.

- Multivariate Extension: Develop response models that incorporate both binary choices and continuous response times to increase identifiability.

- Empirical Application: Apply the validated model to empirical data from a speed-incentivised associative reward learning (SPIRL) task.

- Predictive Validation: Verify that the model captures meaningful psychological relationships, such as the predicted linear relationship between log-transformed response times and participants' uncertainty about outcomes [3].

This approach illustrates how comprehensive validation, combining simulation-based calibration with empirical checks, can overcome methodological challenges specific to a scientific domain.

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing robust validation protocols requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for Bayesian workflow validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bayesian Workflow Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data Generators | Create datasets with known properties for model validation | Simulate from prior predictive distribution; use domain-specific data generators |

| Probabilistic Programming Languages | Implement and fit Bayesian models with MCMC or variational inference | Stan, PyMC, NumPyro, Turing.jl |

| Workflow Management Systems | Automate, document, and reproduce computational workflows | Nextflow, Galaxy, Snakemake [5] [2] |

| MCMC Diagnostic Suites | Assess convergence and sampling efficiency | ArViz, CODA, shinystan |

| Containerization Platforms | Ensure computational environment reproducibility | Docker, Singularity, Podman [2] |

| Bayesian Validation Modules | Implement coverage tests, posterior predictive checks | bayesplot, simhelpers, custom functions in R/Python |

Integrated Validation Workflow

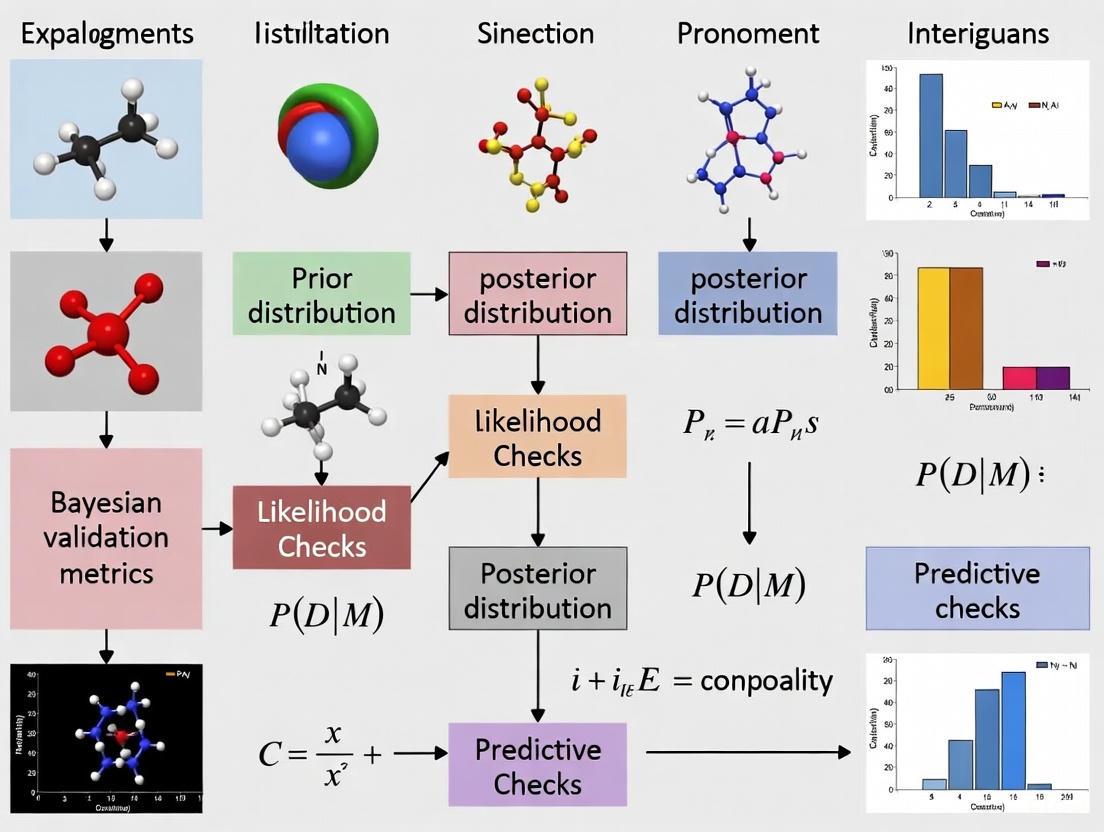

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive validation workflow that integrates the various metrics and protocols discussed, providing a structured approach for validating Bayesian computational workflows:

Bayesian Validation Workflow Diagram

The validation process begins with model specification and proceeds through multiple diagnostic stages, with failures triggering model revisions in an iterative refinement cycle.

Specialized Protocol: Coverage Diagnostic Implementation

For researchers implementing coverage diagnostics, the following detailed protocol provides a step-by-step guide:

Coverage Diagnostics Protocol Diagram

This protocol emphasizes the critical process of using simulation-based calibration to validate whether a Bayesian model's uncertainty quantification is accurate, following established practices for validating Bayesian model implementations [1].

Validation constitutes an indispensable component of the computational workflow, particularly within Bayesian modeling where complexity and uncertainty are inherent. The protocols and metrics outlined here—including coverage diagnostics, posterior predictive checks, and MCMC convergence assessments—provide a structured framework for establishing the credibility of computational results. The case studies from radiation dosimetry and computational psychiatry demonstrate how these validation techniques identify model weaknesses and strengthen scientific conclusions.

As computational methods continue to advance, embracing a comprehensive validation mindset remains fundamental to scientific progress. By implementing rigorous, iterative validation protocols and adhering to FAIR principles for workflow management, researchers across disciplines can ensure their computational workflows produce not just results, but trustworthy, reproducible, and scientifically meaningful insights.

The validation of computational models is a critical step in ensuring their reliability for scientific research and decision-making. Within a Bayesian framework, validation moves beyond simple goodness-of-fit measures to a comprehensive assessment of how well models integrate existing knowledge with new evidence to make accurate predictions. This approach is particularly valuable in fields like drug development and computational psychiatry, where models must often inform high-stakes decisions despite complex, noisy data and inherent uncertainties [6] [3]. Bayesian validation specifically evaluates the posterior distribution, which combines prior knowledge with observed data through Bayes' Theorem, and focuses on a model's predictive accuracy for new observations, rather than just its fit to existing data [7] [8]. This paradigm shift toward predictive performance is fundamental, as a model that accurately represents the underlying problem is crucial to avoid significant repercussions in decision-making processes [7]. The core concepts of model evidence, posterior distributions, and predictive accuracy provide a robust foundation for assessing model quality, quantifying uncertainty, and ultimately determining whether a model is trustworthy enough for real-world application.

Core Theoretical Concepts

Model Evidence and Posterior Distributions

In Bayesian statistics, the posterior distribution is the cornerstone of all inference. It represents the updated beliefs about a model's parameters after considering the observed data. The mathematical mechanism for this update is Bayes' Theorem:

Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior

This formula succinctly captures the Bayesian learning process: the prior distribution encapsulates existing knowledge or uncertainty about the parameters before observing new data [8]. The likelihood quantifies the probability of the observed data under different parameter values [8]. The posterior distribution synthesizes these two elements, forming a complete probabilistic description that is proportional to their product [8]. The normalizing constant required to make this a true probability distribution is the model evidence (also known as the marginal likelihood), which is the probability of the observed data given the entire model [7]. This evidence is crucial for model comparison, as it automatically enforces Occam's razor, penalizing unnecessarily complex models.

For complex models, the posterior distribution is often analytically intractable and must be approximated using computational techniques. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling is a fundamental computational tool for this purpose, allowing researchers to generate samples from the posterior distribution even when its exact form is unknown [8]. This method, along with other advances in computational algorithms, has been instrumental in the popularization of Bayesian methods for realistic and complex models [8].

Predictive Accuracy and Distributions

While the posterior distribution informs us about model parameters, the predictive distribution is the key to assessing a model's practical utility for forecasting new observations [7]. This distribution describes what future data points are expected to look like, given the model and all observed data so far. In the Bayesian framework, predictive accuracy is not merely about a model's fit to the data it was trained on, but its capacity to generalize to new, unseen data [7].

The posterior predictive distribution is formally obtained by averaging the likelihood of new data over the posterior distribution of the parameters. This process naturally accounts for parameter uncertainty, as it integrates over the entire posterior distribution rather than relying on a single point estimate. This integration makes Bayesian predictive distributions inherently probabilistic and better calibrated for uncertainty quantification than frequentist counterparts. Evaluating a model based on its predictive performance aligns with the philosophical perspective that models should be judged by their empirical predictions rather than solely by their internal structure or fit to existing data [7].

Table 1: Key Components of Bayesian Inference and Their Role in Model Validation

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Role in Model Validation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Distribution | P(θ) |

Encapsulates pre-existing knowledge or uncertainty about model parameters before data collection [8]. | |||

| Likelihood | `P(D | θ)` | Quantifies how probable the observed data D is under different parameter values θ [8]. |

||

| Posterior Distribution | `P(θ | D) ∝ P(D | θ)P(θ)` | Represents updated knowledge about parameters after considering the data; the basis for all Bayesian inference [8]. | |

| Model Evidence | `P(D) = ∫P(D | θ)P(θ)dθ` | The probability of data under the model; used for model comparison and selection [7]. | ||

| Predictive Distribution | `P(new D | D) = ∫P(new D | θ)P(θ | D)dθ` | Forecasts new observations; the primary distribution for assessing predictive accuracy [7] [8]. |

Quantitative Metrics for Model Validation

Metrics for Predictive Accuracy

A straightforward and intuitive metric for predictive accuracy, proposed in recent literature, is the measure Δ (Delta) [7]. This measure evaluates the proportion of correct predictions from a leave-one-out (LOO) procedure against the expected coverage probability of a credible interval. The calculation involves the following steps:

- For each observation

iin a dataset of sizen, compute a credible intervalC_ifor the predicted value using a model fitted without that observation. - Determine if the observed value

y_ifalls within this predicted interval, recording a correct prediction (u_i = 1) or an error (u_i = 0). - Calculate the proportion of correct predictions:

κ = (Σu_i)/n. - Compute the accuracy measure: Δ = κ - γ, where

γis the credible level of the interval [7].

The value of Δ ranges from -γ to 1-γ. A value of Δ = 0 indicates good model accuracy, meaning the model's empirical coverage matches its nominal credibility. A significantly negative Δ suggests the model is overconfident and provides poor predictive coverage, while a positive Δ may indicate that the predictive intervals are imprecise or too conservative [7]. This metric can be formalized through a Bayesian hypothesis test to objectively determine if there is evidence that the model lacks good predictive capability [7].

Comprehensive Metrics for Model Performance and Uncertainty

Beyond Δ, a suite of metrics exists for a more comprehensive evaluation of Bayesian models, particularly Bayesian networks. The table below summarizes key metrics for different aspects of model evaluation [9].

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating Performance and Uncertainty of Bayesian Models [9]

| Evaluation Aspect | Metric | Brief Description and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction Performance | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) | Measures the ability to classify binary outcomes. An AUC of 0.5 is no better than random, while 1.0 represents perfect discrimination. |

| Confusion Table Metrics (e.g., True Skill Statistic, Cohen's Kappa) | Assess classification accuracy against a known truth, correcting for chance agreement. | |

| K-fold Cross-Validation | Estimates how the model will generalize to an independent dataset by partitioning data into training and validation sets. | |

| Model Selection & Comparison | Schwarz’ Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Balances model fit against complexity; lower values indicate a better model. |

| Log Pseudo Marginal Likelihood (LPML) | Assesses model predictive performance for model comparison [7]. | |

| Uncertainty of Posterior Outputs | Bayesian Credible Interval | An interval within which an unobserved parameter falls with a specified probability, given the observed data. |

| Gini Coefficient | Measures the "concentration" or inequality of a posterior probability distribution. A value of 0 indicates certainty (one state has probability 1), while higher values indicate more uncertainty spread across states [9]. | |

| Posterior Probability Certainty Index | A measure of the certainty or sharpness of the posterior distribution. |

Application Notes and Protocols

General Workflow for Bayesian Model Validation

The following protocol outlines a standardized workflow for validating Bayesian computational models, synthesizing principles from statistical literature and applied fields like drug development and computational psychiatry [7] [3] [8].

Protocol 1: Workflow for Bayesian Model Validation

Objective: To provide a systematic procedure for evaluating the predictive accuracy and overall validity of a Bayesian computational model.

Materials and Software:

- Computational environment (e.g., R, Python, Stan, PyMC).

- Dataset for model training and testing.

- Bayesian inference software (e.g., JAGS, WinBUGS, Netica for Bayesian networks).

Procedure:

Model and Prior Specification:

- Define the full probabilistic model, including the likelihood function and prior distributions for all parameters.

- Justify prior choices based on literature, expert elicitation, or preliminary data. In regulatory settings like medical device trials, prior information is often based on empirical evidence from previous studies or historical control data [8].

Posterior Computation:

- Use appropriate computational algorithms (e.g., MCMC, Variational Inference) to generate samples from the joint posterior distribution,

P(θ|D)[8]. - Confirm convergence of sampling algorithms using diagnostics (e.g., Gelman-Rubin statistic, trace plots).

- Use appropriate computational algorithms (e.g., MCMC, Variational Inference) to generate samples from the joint posterior distribution,

Posterior Predictive Checking:

- Generate the posterior predictive distribution by simulating new data sets

y_repfrom the model using the posterior samples. - Compare these simulated datasets to the observed data

yusing test quantities or graphical displays. Significant discrepancies indicate potential model failures [7].

- Generate the posterior predictive distribution by simulating new data sets

Quantitative Metric Calculation:

- Predictive Accuracy (Δ):

- Implement a leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation routine [7].

- For each

i, fit the model to dataD_{-i}and construct aγ × 100%credible intervalC_ifor the prediction ofy_i. - Calculate

κand subsequentlyΔ = κ - γ[7]. - Use the Full Bayesian Significance Test (FBST) to test the hypothesis that

κ = γand determine if the model should be rejected [7].

- Comprehensive Metrics:

- Predictive Accuracy (Δ):

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Assess the robustness of posterior inferences and key validation metrics to changes in the prior distributions and model structure [8].

- This is a critical step, especially when prior information is influential, to understand how assumptions impact conclusions.

Decision and Reporting:

- Based on the collected evidence from the validation metrics, decide whether the model has sufficient predictive accuracy for its intended purpose.

- Document all steps, including prior justifications, convergence diagnostics, calculated metrics, and sensitivity analyses, to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Case Study Protocol: Validating a Computational Psychiatry Model

This protocol details a specific application of the Bayesian workflow for validating models of behavior, as demonstrated in computational psychiatry (TN/CP) research [3].

Protocol 2: Validation of a Hierarchical Bayesian Model for Behavioral Analysis

Objective: To ensure robust statistical inference for a Hierarchical Gaussian Filter (HGF) model, a generative model for hierarchical Bayesian belief updating, fitted to multivariate behavioral data (e.g., binary choices and response times) [3].

Background: Behavioral data in cognitive tasks are often univariate (e.g., only binary choices) and contain limited information, posing challenges for reliable inference. Using multivariate data streams (e.g., both choices and response times) can enhance robustness and identifiability [3].

Materials:

- Data: Empirical data from a behavioral task (e.g., the speed-incentivised associative reward learning - SPIRL - task) [3].

- Software: Computational modeling software such as the TAPAS toolbox in MATLAB, which implements the HGF.

Procedure:

Model Specification:

- Define the perceptual model (e.g., the HGF) that describes how an agent updates beliefs about the environment in response to stimuli.

- Define a multivariate response model that simultaneously describes two observed behavioral variables: a) the agent's binary decisions, and b) the continuous response times (RT). This joint modeling approach helps ensure parameter identifiability [3].

Prior Elicitation:

- Set priors for all model parameters (e.g., perceptual learning rates, response model parameters). These can be weakly informative based on the literature or previous, similar experiments.

Bayesian Inference:

- Use MCMC sampling to approximate the joint posterior distribution over all model parameters, given the observed behavioral data.

Validation and Identifiability Checks:

- Parameter Recovery (Simulation):

- Simulate synthetic behavioral data using the generative model with known parameter values.

- Fit the model to this synthetic data and assess the correlation between the true and recovered parameters. High correlations indicate that the model and data can reliably identify the parameters.

- Predictive Accuracy on Empirical Data:

- Apply the LOO-based Δ metric to assess the model's ability to predict both choice and response time outcomes.

- Evaluate if the model captures known behavioral phenomena, such as the linear relationship between log-transformed response times and a participant's inferred uncertainty about the outcome [3].

- Parameter Recovery (Simulation):

Interpretation:

- Once validated, the model's posterior distributions can be interpreted to make inferences about the latent cognitive processes (e.g., belief updating) underlying the observed behavior.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Model Validation

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function and Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software & Libraries | R (with packages like rstan, loo, bayesplot), Python (with PyMC, ArviZ, TensorFlow Probability), Stan |

Core computational environments for specifying Bayesian models, performing MCMC sampling, and calculating validation metrics. |

| Bayesian Network Software | Hugin, Netica, WinBUGS/OpenBUGS | User-friendly modeling shells specifically designed for building and evaluating Bayesian networks, facilitating the integration of heterogeneous data [10] [9]. |

| Model Comparison Metrics | Watanabe-Akaike Information Criterion (WAIC), Log Pseudo Marginal Likelihood (LPML), Bayes Factor | Metrics used to compare and select among multiple competing models based on their estimated predictive performance [7] [11]. |

| Computational Algorithms | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (No-U-Turn Sampler), Variational Inference | Advanced sampling and approximation algorithms that enable Bayesian inference for complex, high-dimensional models that are analytically intractable [8]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Prior-posterior overlap, Bayesian R² |

Methods to quantify the influence of the prior and check the robustness of the model's conclusions to its assumptions [8]. |

Within the framework of Bayesian validation metrics for computational models, the selection between fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models constitutes a critical decision point with profound implications for the generalizability of research findings. This protocol provides a structured methodology for model selection, emphasizing its operationalization within drug development and computational biology. We delineate explicit criteria for choosing between FE and RE models, detail procedures for implementing statistical tests to guide selection, and demonstrate how this choice directly influences the extent to which inferences can be generalized beyond the observed sample. The guidelines are designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a reproducible workflow for strengthening the validity and applicability of their computational models.

In computational model validation, particularly within Bayesian frameworks, the treatment of unobserved heterogeneity is a fundamental concern. Fixed effects models operate under the assumption that the entity-specific error term is correlated with the independent variables, effectively controlling for all time-invariant characteristics within the observed entities [12]. This approach yields consistent estimators by removing the influence of time-invariant confounders, but at the cost of being unable to make inferences beyond the specific entities studied. In contrast, random effects models assume that the entity-specific error term is uncorrelated with the predictors, treating individual differences as random variations drawn from a larger population [13] [12]. This assumption enables broader generalization but risks biased estimates if the assumption is violated.

The selection between these models directly impacts the generalizability of findings—a core consideration in drug development where extrapolation from clinical trials to broader patient populations is routine. This document establishes formal protocols for this selection process, situating it within the broader context of Bayesian validation where prior knowledge and uncertainty quantification play pivotal roles.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Model Formulations

The foundational difference between FE and RE models can be expressed mathematically. For a panel data structure with entities (i) and time periods (t), the general model formulation is:

[ y{it} = \beta0 + \beta1x{it} + \alphai + \varepsilon{it} ]

where (y{it}) is the dependent variable, (x{it}) represents independent variables, and (\varepsilon{it}) is the idiosyncratic error term [12]. The treatment of (\alphai) distinguishes the two models:

- Fixed Effects Model: (\alphai) is treated as a group-specific constant term, potentially correlated with (x{it}). This model uses within-group variation, effectively asking "how do changes in (x) within an entity affect changes in (y)?" [12]

- Random Effects Model: (\alphai) is treated as a group-specific disturbance, assumed to be uncorrelated with (x{it}). The model incorporates both between-group and within-group variation, asking "how does (x) affect (y), accounting for entity-level variance?" [13] [12]

Implications for Generalizability

The choice between FE and RE models directly determines the scope of inference:

- Fixed Effects: Inference is limited to the entities in the sample. In drug development, this might correspond to conclusions applicable only to the specific clinical trial participants or studied cell lines, with limited extrapolation to broader populations [12].

- Random Effects: Inference extends to the entire population from which entities are drawn. This supports broader claims about drug efficacy across patient populations, assuming the study sample represents the target population [13] [12].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Fixed and Random Effects Models

| Aspect | Fixed Effects Model | Random Effects Model |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Assumption | Entity-specific effect (\alpha_i) correlates with independent variables | Entity-specific effect (\alpha_i) uncorrelated with independent variables |

| Scope of Inference | Conditional on entities in the sample | Applicable to the entire population of entities |

| Key Advantage | Controls for all time-invariant confounders | More efficient estimates; can include time-invariant variables |

| Primary Limitation | Cannot estimate effects of time-invariant variables; limited generalizability | Potential bias if correlation assumption is violated |

| Data Usage | Uses within-entity variation only | Uses both within- and between-entity variation |

Statistical Protocol for Model Selection

Formal Hypothesis Testing

The Hausman test provides a statistical framework for choosing between FE and RE models [14]. This test evaluates the null hypothesis that the preferred model is random effects against the alternative of fixed effects. Essentially, it tests whether the unique errors ((u_i)) are correlated with the regressors.

Procedure:

- Estimate both FE and RE models

- Compute the test statistic: (H = (\beta{FE} - \beta{RE})'[\text{Var}(\beta{FE}) - \text{Var}(\beta{RE})]^{-1}(\beta{FE} - \beta{RE}))

- Under the null hypothesis, (H) follows a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of regressors

- Rejection of the null hypothesis (p < 0.05) suggests that FE is preferred; failure to reject suggests RE may be appropriate

Implementation in Stata:

The test is implemented with the sigmamore option to reduce the possibility of negative variance differences in the test statistic calculation [14].

Additional Diagnostic Procedures

Beyond the Hausman test, researchers should conduct supplementary analyses:

- Breusch-Pagan Lagrangian Multiplier Test: Helps decide between random effects and simple pooled OLS regression [14].

- F-test for Fixed Effects: Evaluates whether the fixed effects model significantly improves upon the pooled OLS model [14].

- Contextual Considerations: In drug development, consider whether the studied sites (e.g., clinical centers) represent the entire population of interest or constitute the entire relevant universe.

Table 2: Decision Framework for Model Selection

| Scenario | Recommended Model | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Small number of entities (N < 20-30) | Fixed Effects | Limited degrees of freedom concern; focus on specific entities [15] |

| Entities represent entire population of interest | Fixed Effects | Generalization beyond studied entities is not relevant [12] |

| Entities represent random sample from larger population | Random Effects | Enables inference to broader population [13] [12] |

| Time-invariant variables of theoretical importance | Random Effects | Fixed effects cannot estimate coefficients of time-invariant variables |

| Hausman test significant (p < 0.05) | Fixed Effects | Suggests correlation between α_i and regressors [14] |

| Hausman test not significant (p > 0.05) | Random Effects | Suggests no correlation between α_i and regressors [14] |

Application in Drug Development

Clinical Trial Applications

In clinical trial design and analysis, the choice between FE and RE models has direct implications for regulatory decisions and patient care:

- Multi-site Clinical Trials: When analyzing data from multiple clinical sites, RE models are typically preferred if sites are considered a random sample from all potential treatment locations, allowing generalization to future implementation sites [16].

- Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies: RE models are standard in meta-analyses of drug efficacy because they account for between-study heterogeneity, providing more conservative and generalizable effect size estimates [13].

- Longitudinal Patient Data: When analyzing repeated measurements from patients, FE models can control for all time-invariant patient characteristics, providing robust estimates of treatment effects within the studied cohort [16].

Exposure-Response Analysis

In exposure-response (E-R) modeling, a critical component of drug development, the model selection choice affects dose selection and labeling recommendations:

"E-R analysis is a powerful tool in the trial planning stage to optimize design to detect and quantify signals of interest based on current quantitative information about the compound and/or drug class." [16]

For E-R analyses that pool data from multiple trials, RE models appropriately account for between-trial heterogeneity, supporting more generalizable conclusions about dose-response relationships across diverse populations.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision process for selecting between fixed and random effects models:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Model Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Implementation | Application in Model Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Stata xtreg, hausman commands [14] |

Primary estimation and hypothesis testing for FE vs. RE |

| Specialized Packages | R lme4, plm packages [15] |

Alternative implementation of mixed effects models |

| Data Management Tools | Panel data declaration (xtset in Stata) [14] |

Ensuring proper data structure for panel analysis |

| Visualization Packages | Graphviz DOT language | Creating reproducible decision flowcharts (as in Section 5) |

| Bayesian Modeling Tools | Stan, PyMC3, BUGS | Implementing hierarchical Bayesian models with informed priors |

Bayesian Validation Considerations

Within Bayesian validation frameworks, the FE/RE distinction maps onto prior specification for hierarchical models:

- Fixed Effects Approach: Equivalent to using non-informative or flat priors on entity-specific parameters with no pooling across entities

- Random Effects Approach: Implemented through hierarchical priors where entity-specific parameters are modeled as draws from a common population distribution

The Bayesian paradigm offers particular advantages through Bayesian model averaging, which acknowledges model uncertainty by weighting predictions from both FE and RE specifications according to their posterior model probabilities. This approach is especially valuable in drug development contexts where decisions must incorporate multiple sources of uncertainty.

For computational model validation, Bayesian cross-validation techniques can compare the predictive performance of FE and RE specifications on held-out data, providing a principled approach to evaluating generalizability.

The selection between fixed and random effects models represents more than a statistical technicality—it is a fundamental decision that determines the scope and generalizability of research findings. In drug development and computational modeling, where extrapolation from limited samples to broader populations is essential, this choice demands careful theoretical and empirical justification. The protocols outlined herein provide a structured approach to this decision, emphasizing how model selection either constrains or expands the inferential target. By explicitly connecting statistical modeling decisions to their implications for generalizability, researchers can more transparently communicate the validity and applicability of their findings.

The Underappreciated Challenge of Low Statistical Power in Model Selection

In computational model research, particularly in psychology, neuroscience, and drug development, Bayesian model selection (BMS) has become a cornerstone method for discriminating between competing hypotheses about the mechanisms that generate observed data [17] [18]. However, the validity of inferences drawn from BMS is critically dependent on a largely underappreciated factor: statistical power. Low power in model selection not only reduces the chance of correctly identifying the true model (increasing Type II errors) but also diminishes the likelihood that a statistically significant finding reflects a true effect (increasing Type I errors) [17]. This challenge is exacerbated in studies that compare many candidate models, where the expansion of the model space itself can drastically reduce power, a factor often overlooked during experimental design [17]. This document frames these challenges within the context of Bayesian validation metrics, providing application notes and protocols to diagnose, understand, and overcome low statistical power in model selection.

Quantitative Evidence of the Power Deficiency

A recent narrative review of the literature reveals that the field suffers from critically low statistical power for model selection [17]. The analysis demonstrates that power is a function of both sample size and the size of the model space under consideration.

Table 1: Empirical Findings on Statistical Power in Model Selection

| Field of Study | Number of Studies Reviewed | Studies with Power < 80% | Primary Method of Model Selection | Key Factor Reducing Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology & Human Neuroscience | 52 | 41 (79%) | Fixed Effects BMS | Large model space (number of competing models) |

| General Computational Modelling | Not Specified | Widespread | Random Effects BMS (increasingly) | Inadequate sample size for given model space |

The central insight is that statistical power for model selection increases with sample size but decreases as more models are considered [17]. Intuitively, distinguishing the single best option from among many plausible candidates requires substantially more evidence (data) than choosing between two.

Figure 1: The relationship between sample size, model space size, and statistical power in model selection.

Methodological Pitfalls: Fixed Effects vs. Random Effects

A critical methodological issue contributing to the power problem is the prevalent use of fixed effects model selection in psychological and cognitive sciences [17]. This approach assumes that a single model is the true underlying model for all subjects in a study, effectively concatenating data across participants and ignoring between-subject variability.

Table 2: Comparison of Model Selection Approaches

| Characteristic | Fixed Effects BMS | Random Effects BMS |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | One model generates data for all subjects [17]. | Different subjects' data can be generated by different models [17] [18]. |

| Account for Heterogeneity | No | Yes |

| Sensitivity to Outliers | Pronounced sensitivity; a single outlier can skew results [17]. | Highly robust to outliers [18]. |

| False Positive Rate | Unreasonably high [17]. | Controlled. |

| Appropriate Inference | Inference about the specific sample tested. | Inference about the population from which the sample was drawn [17]. |

The fixed effects approach is considered statistically implausible for group studies in neuroscience and psychology because it disregards meaningful between-subject variability [17] [18]. It has been shown to lack specificity, leading to high false positive rates, and is extremely sensitive to outliers. The field is increasingly moving towards random effects BMS, which explicitly models the possibility that different individuals are best described by different models and estimates the probability of each model being expressed across the population [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols for Power Analysis & Model Selection

Protocol 1: Power Analysis for Bayesian Model Selection

Objective: To determine the necessary sample size to achieve a desired level of statistical power (e.g., 80%) for a model selection study, given a specific model space.

Materials: Pilot data, statistical software (e.g., R, Python).

Procedure:

- Define Model Space: Enumerate all K candidate models to be compared [17].

- Specify Data-Generating Model: Choose one model from the space to serve as the hypothetical "true" data-generating model.

- Simulate Synthetic Data: Use the "true" model to generate synthetic datasets for a range of sample sizes (e.g., N=20, 50, 100, 200). This requires specifying prior distributions for model parameters based on pilot data or literature estimates [19].

- Perform Model Selection: For each synthetic dataset and sample size, perform random effects BMS (see Protocol 2) to compute the posterior model probabilities.

- Calculate Power: Over a large number of iterations (e.g., 1000), compute the proportion of times the true data-generating model is correctly identified as the most probable. Power is this proportion.

- Establish Sample Size: Identify the sample size at which power meets or exceeds the desired threshold (e.g., 80%).

Protocol 2: Implementing Random Effects Bayesian Model Selection

Objective: To perform robust group-level model selection that accounts for between-subject variability.

Materials: Log-model evidence for each model and each subject (e.g., approximated by AIC, BIC, or negative free-energy [18]), software for random effects BMS (e.g., SPM, custom code in R/Python).

Procedure:

- Model Inversion: For each subject n and each candidate model k, compute the log-model evidence, ℓnk = p(Xn ∣ Mk) [17] [18]. This step marginalizes over the model parameters and can be approximated using methods like Variational Bayes or sampling.

- Specify Hierarchical Model: Assume that the model responsible for generating each subject's data is drawn from a multinomial distribution, itself governed by a Dirichlet prior distribution over the model probabilities [17] [18].

- Infer Posterior Distribution: Estimate the posterior distribution over the model probabilities. This distribution describes the probability that any model generated the data of a randomly chosen subject [18].

- Report Key Metrics:

- Expected Model Frequencies: The mean of the posterior Dirichlet distribution, indicating the probability of each model being the data-generating model in the population.

- Exceedance Probabilities: The probability that a given model is more likely than any other model in the set [18].

Figure 2: Workflow for conducting Random Effects Bayesian Model Selection at the group level.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Bayesian Model Selection and Power Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | An approximation of log-model evidence that balances model fit and complexity [20] [18]. | Best used for model comparison relative to other models; sensitive to sample size [20]. |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Another approximation of log-model evidence with a heavier penalty for model complexity than AIC [20] [18]. | Useful for model comparison; assumes a "true model" is in the candidate set. |

| Variational Bayes (VB) | An analytical method for approximating intractable posterior distributions and model evidence [18]. | More computationally efficient than sampling methods; provides a lower bound on the model evidence. |

| Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) | A Bayesian measure of model fit and complexity, useful for comparing models in a hierarchical setting [21]. | Commonly used for comparing complex hierarchical models (e.g., GLMMs). |

| Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA) | A computational method for Bayesian inference on latent Gaussian models [21]. | Highly efficient for a large class of models (e.g., spatial, longitudinal); provides direct computation of predictive distributions. |

| Simulation-Based Power Analysis | A computational method to estimate statistical power by repeatedly generating and analyzing synthetic data [19]. | Versatile and applicable to complex designs where closed-form power equations are not feasible. |

Bayesian workflow represents a comprehensive, iterative framework for conducting robust data analysis, emphasizing model building, inference, model checking, and improvement [22]. Within computational model research, this workflow provides a structured approach for model validation under uncertainty—a critical process for determining whether computational models accurately represent physical systems before deployment in real-world applications [23]. The Bayesian approach to validation offers distinct advantages over classical methods by focusing on model acceptance rather than rejection and providing a natural mechanism for incorporating prior knowledge while quantifying uncertainty in all observations, model parameters, and model structure [22] [24] [23].

The integration of Bayesian validation metrics within this workflow enables researchers to move beyond binary pass/fail decisions by providing continuous measures of model adequacy that account for both available data and prior knowledge [23]. This framework is particularly valuable in fields like drug development and computational modeling, where decisions must be made despite imperfect information and where the consequences of model inaccuracies can be significant [24] [23].

Bayesian Validation Metrics: Theoretical Foundation

Core Principles of Bayesian Model Validation

Bayesian validation metrics provide a probabilistic framework for assessing computational model accuracy by comparing model predictions with experimental observations. Unlike classical hypothesis testing that focuses on model rejection, Bayesian approaches quantify the evidence supporting a model through posterior probabilities [23]. The fundamental theorem underlying Bayesian methods is Bayes' rule, which in the context of model validation can be expressed as:

$$ P(Hi|Y) = \frac{P(Y|Hi)P(H_i)}{P(Y)} $$

Where $Hi$ represents a hypothesis about model accuracy, $Y$ represents observed data, $P(Hi)$ is the prior probability of the hypothesis, $P(Y|Hi)$ is the likelihood of observing the data under the hypothesis, and $P(Hi|Y)$ is the posterior probability of the hypothesis given the data [24] [23].

This approach allows for sequential learning, where prior knowledge is formally combined with newly acquired data to update beliefs about model validity [24]. The Bayesian validation metric thus provides a quantitative measure of agreement between model predictions and experimental observations that evolves as additional evidence becomes available [23].

Decision-Theoretic Framework for Validation

A key advancement in Bayesian validation metrics incorporates explicit decision theory, recognizing that validation ultimately supports decision-making under uncertainty [23]. This Bayesian risk-based decision method considers the consequences of incorrect validation decisions through a loss function that accounts for the cost of Type I errors (rejecting a valid model) and Type II errors (accepting an invalid model) [23].

The Bayes risk criterion minimizes the expected loss or cost function defined as:

$$ R = C{00}P(H0|Y)P(d0|H0) + C{01}P(H0|Y)P(d1|H0) + C{10}P(H1|Y)P(d0|H1) + C{11}P(H1|Y)P(d1|H1) $$

Where $C{ij}$ represents the cost of deciding $di$ when $Hj$ is true, $P(Hj|Y)$ is the posterior probability of hypothesis $Hj$, and $P(di|Hj)$ is the probability of deciding $di$ when $H_j$ is true [23]. This framework enables validation decisions that consider not just statistical evidence but also the practical consequences of potential errors.

Application Notes: Implementing Bayesian Workflow

End-to-End Bayesian Workflow for Computational Models

Implementing a complete Bayesian workflow for computational model validation involves multiple interconnected phases that form an iterative, non-linear process [22] [25]. The workflow begins with clearly defining the driving question that the model must address, as this question influences all subsequent decisions about data collection, model structure, validation approach, and interpretation of results [25]. Subsequent phases include model building, inference, model checking and improvement, and model comparison, with iteration between phases as understanding improves [22].

Table 1: Phases of Bayesian Workflow for Computational Model Validation

| Phase | Key Activities | Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Definition | Define driving question; identify stakeholders; establish decision context | Clearly articulated validation objectives; decision criteria |

| Data Collection | Design validation experiments; gather observational data; assess data quality | Structured datasets for model calibration and validation |

| Model Building | Specify model structure; establish prior distributions; encode domain knowledge | Probabilistic model with specified priors and likelihood |

| Inference | Perform posterior computation; address computational challenges | Posterior distributions of model parameters and predictions |

| Model Checking | Evaluate model fit; assess predictive performance; identify discrepancies | Diagnostic measures; identified model weaknesses |

| Model Improvement | Revise model structure; adjust priors; expand data collection | Refined models addressing identified limitations |

| Validation Decision | Compute validation metrics; assess decision risks; make accept/reject decision | Quantitative validation measure; decision recommendation |

This workflow emphasizes continuous model refinement through comparison of multiple candidate models, with the goal of developing a comprehensive understanding of model strengths and limitations rather than simply selecting a single "best" model [22] [25].

Bayesian Validation Metrics in Practice

The implementation of Bayesian validation metrics varies based on the type of available validation data. Two common scenarios in reliability modeling include:

Case 1: Multiple Pass/Fail Tests - When validation involves multiple binary outcomes (success/failure), the Bayesian validation metric incorporates both the number of observed failures and the prior knowledge about model reliability [23]. For a series of $n$ tests with $x$ failures, the posterior distribution of the reliability parameter $R$ can be derived using conjugate Beta-Binomial analysis.

Case 2: System Response Measurement - When validation involves continuous system responses, the validation metric quantifies the agreement between model predictions and observed data using probabilistic measures [23]. This typically involves defining a discrepancy function between predictions and observations and evaluating this function under the posterior predictive distribution.

Table 2: Bayesian Validation Metrics for Different Data Types

| Data Type | Validation Metric | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pass/Fail Tests | Posterior reliability distribution | Choice of Beta prior parameters; number of tests required |

| System Response Measurements | Posterior predictive checks; Bayes factor | Definition of acceptable discrepancy; computational demands |

| Model Comparison | Bayes factor; posterior model probabilities | Sensitivity to prior specifications; interpretation guidelines |

| Risk-Based Decision | Bayes risk; expected loss | Estimation of decision costs; minimization approach |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian Risk-Based Validation for Computational Models

This protocol outlines the procedure for applying Bayesian risk-based decision methods to computational model validation, following the methodology developed by Jiang and Mahadevan [23].

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Bayesian Validation

| Item | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Model | Mathematical representation of physical system | Should include uncertainty quantification |

| Validation Dataset | Experimental observations for comparison | Should represent system conditions of interest |

| Bayesian Inference Software | Platform for posterior computation | Options: Stan, PyMC, JAGS, or custom MCMC |

| Prior Information | Domain knowledge and previous studies | May be informative or weakly informative |

| Decision Cost Parameters | Quantified consequences of validation errors | Should reflect practical impact of decisions |

Procedure

Define Validation Hypotheses

- Formulate null hypothesis ($H_0$): model is adequate for intended use

- Formulate alternative hypothesis ($H_1$): model is inadequate

- Establish quantitative criteria for model adequacy based on intended applications

Specify Prior Distributions

- Encode existing knowledge about model parameters through prior distributions

- For risk-based approach, specify prior probabilities for hypotheses $P(H0)$ and $P(H1)$

- Conduct sensitivity analysis to assess prior influence

Collect Validation Data

- Design validation experiments to stress model under conditions relevant to decision context

- Record system responses and associated measurement uncertainties

- Document experimental conditions thoroughly

Compute Bayesian Validation Metric

- Calculate likelihood ratio (Bayes factor) comparing evidence for $H0$ versus $H1$

- Update prior probabilities to obtain posterior probabilities $P(H0|Y)$ and $P(H1|Y)$

- For complex models, use Bayesian networks and MCMC techniques to compute likelihoods

Determine Decision Threshold

- Quantify costs of Type I ($C{01}$) and Type II ($C{10}$) errors

- Calculate threshold $T = \frac{(C{01} - C{11})P(H0)}{(C{10} - C{00})P(H1)}$

- Accept model if Bayes factor exceeds threshold $T$

Minimize Bayes Risk

- Compute expected risk for both acceptance and rejection decisions

- Select decision that minimizes expected risk

- For optimal experimental design, determine data collection strategy that minimizes expected posterior risk

Protocol 2: Bayesian Workflow Implementation for Model Development

This protocol provides a structured approach for implementing the complete Bayesian workflow in computational model development and validation projects [22] [25].

Procedure

Problem Formulation

- Engage stakeholders to define the driving question and decision context

- Identify key model outputs relevant to decisions

- Establish criteria for model validation and acceptance

Data Collection and Preparation

- Identify relevant existing data sources

- Design targeted experiments to fill knowledge gaps

- Clean and format data for analysis

- Document data provenance thoroughly

Initial Model Specification

- Develop conceptual model based on domain knowledge

- Specify probabilistic model with prior distributions

- Encode existing knowledge and uncertainties through priors

- Develop computational implementation of model

Initial Model Fitting

- Perform posterior computation using appropriate algorithms

- Assess computational convergence

- Check for identifiability issues

Model Checking and Evaluation

- Conduct posterior predictive checks

- Compare predictions to empirical data

- Identify systematic discrepancies

- Assess model adequacy for intended purposes

Model Refinement

- Expand model to address identified limitations

- Adjust prior distributions based on initial results

- Consider alternative model structures

- Collect additional data if needed

Model Comparison and Selection

- Compare multiple models using appropriate metrics

- Evaluate trade-offs between model complexity and performance

- Select model(s) for final validation

Validation and Decision

- Apply Bayesian validation metrics to assess model adequacy

- Quantify uncertainty in validation conclusions

- Make risk-informed decision about model acceptance

- Document entire workflow for transparency

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Trials

Bayesian workflow and validation metrics offer significant advantages in drug development, where decisions must be made despite limited data and substantial uncertainties [24]. The Bayesian framework aligns naturally with clinical practice, as it supports sequential learning and provides probabilistic statements about treatment effects that are more intuitive for decision-makers than p-values from classical statistics [24] [26].

In clinical trials, Bayesian methods enable continuous learning as data accumulate, allowing for more adaptive trial designs and more nuanced interpretations of results [24]. For example, the Bayesian approach allows calculation of the probability that a treatment exceeds a clinically meaningful effect size, providing directly actionable information for regulators and clinicians [24]. This contrasts with traditional hypothesis testing, which provides only a binary decision based on arbitrary significance thresholds.

The BASIE (Bayesian Interpretation of Estimates) framework developed by Mathematica represents an innovative application of Bayesian thinking to impact evaluation, providing more useful interpretations of evidence for decision-makers [26]. This approach has been successfully applied to evaluate educational interventions, health care programs, and other social policies, demonstrating the practical utility of Bayesian methods for evidence-based decision making [26].

Bayesian workflow provides a comprehensive framework for transparent and reproducible research, with Bayesian validation metrics offering principled approaches for assessing computational model adequacy under uncertainty. The integration of decision theory with Bayesian statistics enables risk-informed validation decisions that account for both statistical evidence and practical consequences. Implementation of structured protocols for Bayesian workflow and validation ensures rigorous model development and evaluation, ultimately leading to more reliable computational models for scientific research and decision support.

The iterative nature of Bayesian workflow, with its emphasis on model checking, refinement, and comparison, fosters deeper understanding of models and their limitations. As computational models continue to play increasingly important roles in fields ranging from drug development to engineering design, the adoption of Bayesian workflow and validation metrics will support more transparent, reproducible, and decision-relevant model-based research.

A Practical Toolkit: Essential Bayesian Metrics and Diagnostic Methods

Posterior Predictive Checks (PPCs) are a foundational technique in Bayesian data analysis used to validate a model's fit to observed data. The core idea is simple: if a model is a good fit, then data generated from it should look similar to the data we actually observed [27]. This is operationalized by generating replicated datasets from the posterior predictive distribution - the distribution of the outcome variable implied by a model after updating our beliefs about unknown parameters θ using observed data y [28].

The posterior predictive distribution for new observation ỹ is mathematically expressed as:

p(ỹ | y) = ∫ p(ỹ | θ) p(θ | y) dθ

In practice, for each parameter draw θ(s) from the posterior distribution, we generate an entire vector of N outcomes ỹ(s) from the data model conditional on θ(s). This results in an S × N matrix of simulations, where S is the number of posterior draws and N is the number of data points in y [28]. Each row of this matrix represents a replicated dataset (yrep) that can be compared directly to the observed data y [27].

PPCs analyze the degree to which data generated from the model deviates from data generated from the true underlying distribution. This process provides both a quantitative and qualitative "sense check" of model adequacy and serves as a powerful tool for explaining model performance to collaborators and stakeholders [29].

Theoretical Framework and Implementation Protocol

Workflow for Conducting Posterior Predictive Checks

The following diagram illustrates the complete PPC workflow, from model specification to diagnostic interpretation:

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: Basic PPC Implementation

This protocol provides the fundamental steps for performing posterior predictive checks in a Bayesian modeling workflow.

- Objective: Assess overall model adequacy by comparing observed data to data simulated from the posterior predictive distribution.

- Materials:

- Observed data vector

y - Fitted Bayesian model with posterior samples

- Statistical software with Bayesian modeling capabilities (e.g., PyMC, Stan)

- Observed data vector

- Procedure:

- Model Specification: Define the full Bayesian model, including likelihood function, prior distributions, and any hierarchical structure.

- Posterior Sampling: Draw

Ssamples from the posterior distribution of model parametersθusing MCMC or variational inference methods. - Replicated Data Generation: For each posterior sample

θ(s), simulate a new datasetyrep(s)from the likelihoodp(y | θ(s))using the same predictor values as the original data. - Test Statistic Selection: Choose one or more test statistics

T()that capture relevant features of the data (e.g., mean, variance, proportion of zeros, maximum value). - Distribution Comparison: Calculate

T(y)for observed data andT(yrep(s))for each replicated dataset, then compare their distributions graphically or numerically.

- Quality Control: Ensure MCMC convergence (R-hat ≈ 1.0, sufficient effective sample size) before generating

yrepto avoid misleading results based on poor posterior approximations.

Protocol 2: Prior Predictive Checking

Prior predictive checks assess the reasonableness of prior specifications before observing data [29].

- Objective: Evaluate whether prior distributions incorporate appropriate scientific knowledge and generate plausible outcome values.

- Materials:

- Specified prior distributions for all model parameters

- Model structure without observed data

- Procedure:

- Prior Sampling: Draw samples directly from prior distributions without conditioning on data.

- Data Simulation: Generate datasets from the sampling distribution using prior samples.

- Plausibility Assessment: Examine whether simulated data fall within scientifically reasonable ranges.

- Prior Refinement: Adjust priors if generated data include implausible values (e.g., negative counts, probabilities outside [0,1]).

- Quality Control: Use weakly informative priors that regularize estimates without overly constraining parameter space.

Quantitative Assessment of Model Fit

Test Statistics for PPCs

The choice of test statistic depends on the model type and specific aspects of fit under investigation. The table below summarizes common test statistics used in PPCs:

Table 1: Test Statistics for Posterior Predictive Checks

| Model Type | Test Statistic | Formula | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Linear Models | Proportion of Zeros | T(y) = mean(y == 0) |

Assess zero-inflation [28] |

| All Models | Mean | T(y) = Σy_i/n |

Check central tendency |

| All Models | Standard Deviation | T(y) = √[Σ(y_i-ȳ)²/(n-1)] |

Check dispersion |

| All Models | Maximum | T(y) = max(y) |

Check extreme values |

| All Models | Skewness | T(y) = [Σ(y_i-ȳ)³/n] / [Σ(y_i-ȳ)²/n]^(3/2) |

Check asymmetry |

| Regression Models | R-squared | T(y) = 1 - (SS_res/SS_tot) |

Assess explanatory power |

Case Study: Poisson vs. Negative-Binomial Regression

A comparative analysis of Poisson and negative-binomial models for roach count data demonstrates the application of PPCs [28]. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons:

Table 2: Model Comparison Using Posterior Predictive Checks

| Assessment Metric | Poisson Model | Negative-Binomial Model | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of Zeros | Underestimated observed 35.9% | Appropriately captured observed proportion | Negative-binomial better accounts for zero-inflation |

| Extreme Value Prediction | Reasonable range | Occasional over-prediction of large values | Poisson more conservative for extreme counts |

| Dispersion Fit | Systematically underfitted variance | Adequately captured data dispersion | Negative-binomial accounts for over-dispersion |

| Visual PPC Assessment | Poor density matching, especially near zero | Good overall distributional match | Negative-binomial provides superior fit |

Advanced Applications and Diagnostic Tools

Specialized PPCs for Specific Model Types

Different model classes require specialized diagnostic approaches:

- Item Response Theory Models: PPCs can detect extreme response styles (ERS) by comparing observed and expected proportions of extreme category responses at both group and individual levels [30].

- Count Data Models: Rootograms and binned error plots provide enhanced visualization of distributional fit beyond standard density comparisons.

- Censored Data Models: Specialized PPCs assess fit to censoring mechanisms and truncated distributions.

Graphical PPC Diagnostics

The bayesplot package provides comprehensive graphical diagnostics for PPCs [28] [27]. The diagram below illustrates the process of creating and interpreting these diagnostic visualizations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Bayesian Model Checking

| Tool Name | Application Context | Key Functionality | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyMC | General Bayesian modeling | Prior/posterior predictive sampling, MCMC diagnostics | pm.sample_posterior_predictive(idata, extend_inferencedata=True) [29] |

| bayesplot | PPC visualization | Comprehensive graphical checks, ggplot2 integration | ppc_dens_overlay(y, yrep[1:50, ]) [28] |

| ArviZ | Bayesian model diagnostics | PPC visualization, model comparison, MCMC diagnostics | az.plot_ppc(idata, num_pp_samples=100) [29] |

| Stan | Advanced Bayesian modeling | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, generated quantities block for yrep | generated quantities { vector[N] y_rep; } [27] |

| RStanArm | Regression modeling | Precompiled regression models, convenient posterior_predict() method |

yrep_poisson <- posterior_predict(fit_poisson, draws = 500) [28] |

Comparative Analysis of PPC Methods

Performance Metrics for PPC Assessment

The table below summarizes quantitative criteria for evaluating PPC results across different model types and application contexts:

Table 4: Performance Metrics for PPC Assessment

| Evaluation Dimension | Assessment Method | Acceptance Criterion | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distributional Fit | Overlaid density plots | Visual alignment across distribution | Ignoring tails or specific regions (e.g., zeros) |

| Statistical Consistency | Posterior predictive p-values | 0.05 < PPP < 0.95 for key statistics |

Focusing only on extreme PPP values |

| Predictive Accuracy | Interval coverage | ~95% of observations within 95% PPI | Systematic under/over-coverage patterns |

| Feature Capture | Discrepancy measures | No systematic patterns in errors | Over-interpreting minor discrepancies |

| Computational Efficiency | Sampling time | Reasonable runtime for model complexity | Inadequate posterior sampling affecting yrep quality |

Protocol 3: PPCs for Extreme Response Style Detection

This specialized protocol adapts PPCs for detecting extreme response styles in psychometric models [30].

- Objective: Identify participant tendency to select extreme response categories independent of item content.

- Materials:

- Item response data with Likert-type scales

- Fitted unidimensional IRT model (e.g., Generalized Partial Credit Model)

- Procedure:

- Model Fitting: Estimate person and item parameters using Bayesian IRT model.

- Replicated Data Generation: Simulate item responses from posterior predictive distribution.

- ERS Discrepancy Measures: Calculate proportion of extreme responses for each participant in both observed and replicated datasets.

- Individual-Level Comparison: Identify participants with observed extreme responses consistently exceeding replicated values.

- Group-Level Assessment: Compare overall distribution of extreme responses between observed and replicated data.

- Quality Control: Use person-specific fit statistics to avoid conflating high trait levels with response style.

Within the framework of Bayesian statistics, the validation and selection of computational models are critical steps in ensuring that inferences are robust and predictive. Traditional metrics like AIC and DIC have been widely used, but they come with limitations, particularly in their handling of model complexity and full posterior information. This has led to the adoption of more advanced information-theoretic metrics, namely the Widely Applicable Information Criterion (WAIC) and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO-CV) [31]. These methods provide a more principled approach for estimating a model's out-of-sample predictive accuracy by fully utilizing the posterior distribution [32]. For researchers in fields like drug development, where predictive performance can directly impact decision-making, understanding and applying these metrics is essential. This note details the theoretical foundations, computation, and practical application of WAIC and LOO for evaluating Bayesian models.

Theoretical Foundations

The Goal of Predictive Model Assessment

The primary goal of model evaluation in a Bayesian context is often to assess the model's predictive performance on new, unseen data. Both WAIC and LOO are designed to approximate the model's expected log predictive density (elpd), a measure of how likely the model is to predict new data points effectively [31] [33]. Unlike methods that only assess fit to the observed data, this focus on predictive accuracy helps guard against overfitting.

WAIC (Widely Applicable Information Criterion)

WAIC, as a fully Bayesian generalization of AIC, computes the log-pointwise-predictive-density (lppd) adjusted for the effective number of parameters in the model [33]. It is calculated as follows:

- Log-pointwise-predictive-density (lppd): This is the sum of the log of the average predictive density for each observed data point across all posterior samples.