Benchmark Datasets for Computational Chemistry: A Guide for Drug Development and AI Model Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to benchmark datasets for computational chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Benchmark Datasets for Computational Chemistry: A Guide for Drug Development and AI Model Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to benchmark datasets for computational chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational role of these datasets in validating quantum chemistry methods and accelerating AI model development. The scope covers key datasets, their applications in force field parameterization and machine learning potential training, common challenges in implementation, and robust frameworks for comparative model evaluation. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select appropriate benchmarks, improve predictive accuracy, and ultimately streamline the discovery of new therapeutics and materials.

The Foundation: Understanding Benchmark Datasets and Their Role in Computational Chemistry

What Are Benchmark Datasets and Why Do They Matter?

In the field of computational chemistry, where new algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) models are developed at a rapid pace, benchmark datasets are standardized collections of data used to objectively evaluate, compare, and validate the performance of computational methods. They serve as a common ground, ensuring that comparisons between different tools are fair, reproducible, and meaningful [1] [2].

Their importance cannot be overstated. Much like the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) challenge provided a community-driven framework that accelerated progress in protein structure prediction—a feat recognized by a Nobel Prize—benchmarking is now seen as essential for advancing areas like small-molecule drug discovery [1]. They help the scientific community cut through the hype surrounding new AI tools, providing concrete evidence of performance and limitations [2].

Key Benchmark Datasets in Computational Chemistry

The table below summarizes some of the prominent benchmark datasets available to researchers, highlighting their primary focus and scale.

Table 1: Overview of Computational Chemistry Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset Name | Primary Focus | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [3] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | - Over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots.- DFT-level data on systems up to 350 atoms.- Chemically diverse, including heavy elements and metals. |

| nablaDFT [4] | Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | - Nearly 2 million drug-like molecules with conformations.- Properties calculated at ωB97X-D/def2-SVP level.- Includes energies, Hamiltonian matrices, and wavefunction files. |

| QCBench [5] | Large Language Models (LLMs) | - 350 quantitative chemistry problems.- Covers 7 chemistry subfields and three difficulty levels.- Designed to test step-by-step numerical reasoning. |

| NIST CCCBDB [6] | Quantum Chemical Methods | - Experimental and ab initio thermochemical data for gas-phase molecules.- A long-standing resource for method comparison. |

| MoleculeNet [7] | General Molecular Machine Learning | - A collection of 16 datasets.- Includes quantum mechanics, physical, and biophysical chemistry tasks. (Note: Known to have some documented flaws). |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

A robust benchmarking study goes beyond simply running software on a dataset. It involves a structured methodology to ensure results are reliable and trustworthy.

Dataset Curation and Validation

The foundation of any benchmark is high-quality data. The process typically involves:

- Data Collection and Standardization: Data is gathered from various sources like literature, patents, or public databases. Chemical structures, often provided as SMILES strings, are standardized using toolkits like RDKit to ensure consistent representation (e.g., neutralizing salts, handling tautomers) [8].

- Curation and Error-Checking: This critical step involves identifying and removing invalid structures (e.g., SMILES that cannot be parsed), correcting charges, and handling stereochemistry. It also involves detecting and resolving duplicate entries and experimental outliers [7] [8]. For example, one analysis found duplicates with conflicting labels in a widely used blood-brain barrier penetration dataset [7].

- Defining Data Splits: The dataset is systematically divided into training, validation, and test sets. To prevent over-optimistic performance, the test set is often constructed using scaffold splitting, which ensures that molecules with core structures not seen during training are used for the final evaluation [7] [4].

Model Training and Evaluation

- Training MLIPs and NNPs: For forcefield models, the process involves training neural networks on high-quality quantum mechanical data, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. The model learns to predict system energy and atomic forces for a given molecular configuration with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost [3] [2].

- Evaluating LLMs: For large language models, benchmarks like QCBench present problems in textual form. The model's reasoning and final answer are assessed, often using verification tools that can handle numerical tolerances common in chemistry [5].

- Performance Metrics: The choice of metric depends on the task. Common metrics include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression tasks (e.g., predicting energy) [4] and accuracy or balanced accuracy for classification tasks (e.g., predicting toxicity) [8]. A crucial aspect is evaluating performance inside the model's Applicability Domain (AD), which gives confidence in predictions for molecules that are structurally similar to those in the training data [8].

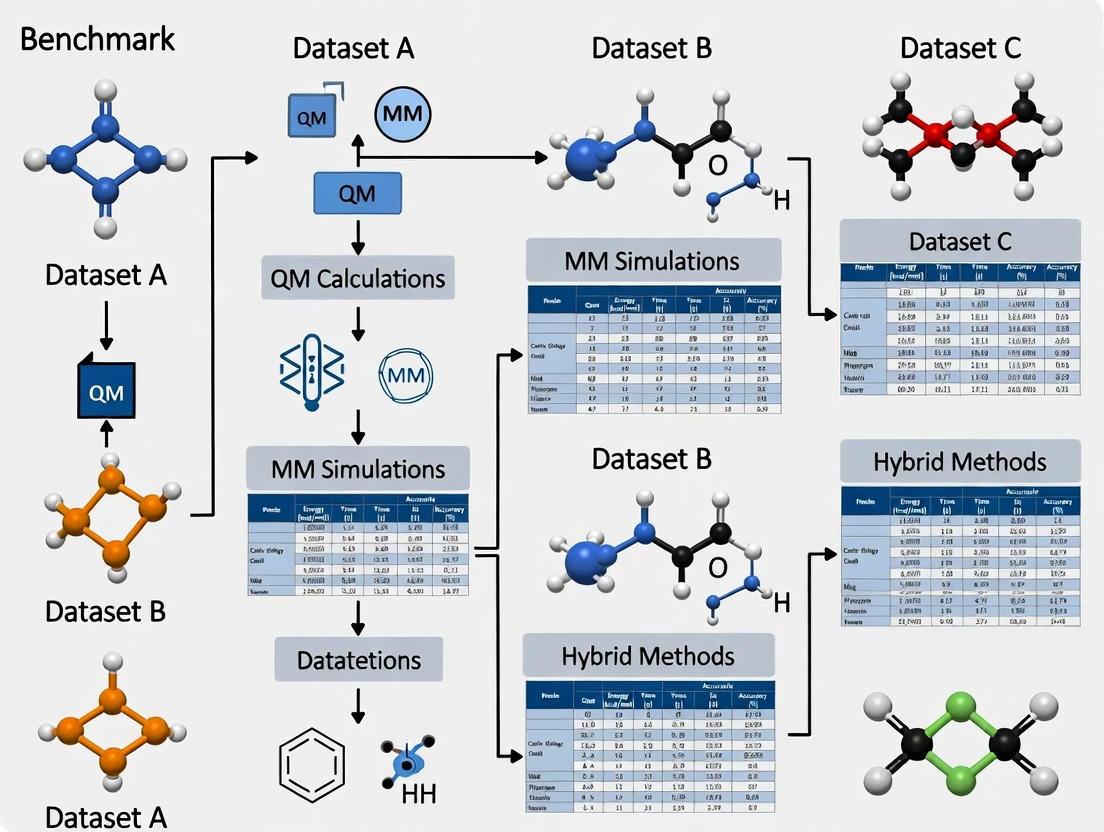

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for developing and using a benchmark dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key computational tools and resources that function as the "research reagents" in the field of computational chemistry benchmarking.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Computational Chemistry Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [8] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, used for standardizing chemical structures, calculating molecular descriptors, and handling data curation. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [3] | Computational Method | A quantum mechanical method used to generate high-quality training data for electronic properties, energies, and forces. |

| Psi4 [4] | Quantum Chemistry Package | An open-source software used for computing quantum chemical properties on molecules, such as energies and wavefunctions. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [2] | Machine Learning Architecture | A type of neural network that operates directly on graph representations of molecules, making them well-suited for predicting molecular properties. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) [8] | Modeling Concept | A defined chemical space where a QSAR model is considered to be reliable; used to identify when a prediction for a new molecule is trustworthy. |

Benchmark datasets are the bedrock of progress in computational chemistry. They transform subjective claims about a model's capability into objective, quantifiable facts. As the field continues to evolve, driven by AI and machine learning, the community's commitment to developing more rigorous, diverse, and carefully curated benchmarks will be paramount. This commitment, as seen in initiatives like OMol25 and the call for ongoing benchmarking in drug discovery, is what will allow researchers to reliably identify the best tools, accelerate scientific discovery, and ultimately design new medicines and materials with greater confidence [3] [1].

In computational chemistry, the accurate prediction of molecular properties is fundamental to advancements in materials science, drug discovery, and catalysis. Among the myriad of electronic structure methods available, the coupled-cluster singles, doubles, and perturbative triples (CCSD(T)) method and Density Functional Theory (DFT) represent two pivotal approaches with complementary strengths and limitations. DFT balances computational efficiency with reasonable accuracy for many systems, while CCSD(T) is often regarded as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for its high accuracy, though at a significantly higher computational cost [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, framing the discussion within the critical context of benchmark datasets that validate and drive methodological research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this methodological landscape is crucial for selecting appropriate tools for predicting molecular properties, reaction energies, and interaction strengths in complex biological and chemical systems.

The development of reliable benchmark datasets has profoundly shaped modern computational chemistry. These datasets typically comprise highly accurate experimental data or high-level theoretical results against which more approximate methods are validated. For example, the 3dMLBE20 database containing bond energies of 3d transition metal-containing diatomic molecules has been instrumental in testing both CCSD(T) and DFT methods [10]. Similarly, specialized benchmarks for biologically relevant catecholic systems have enabled systematic evaluation of computational methods for pharmaceutical applications [11] [12]. Within this framework of benchmark-driven validation, we explore the technical capabilities, performance, and appropriate applications of both CCSD(T) and DFT.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Density Functional Theory (DFT)

DFT is a computational quantum mechanical approach that determines the total energy of a molecular system through its electron density distribution (ρ(r)), rather than the more complex many-electron wavefunction [13]. This method is grounded in the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that the ground-state energy is uniquely determined by the electron density. The practical implementation of DFT uses the Kohn-Sham scheme, which introduces a system of non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the interacting system. The total energy functional in Kohn-Sham DFT is expressed as:

[E[\rho] = Ts[\rho] + V{ext}[\rho] + J[\rho] + E_{xc}[\rho]]

where (Ts[\rho]) represents the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, (V{ext}[\rho]) is the external potential energy, (J[\rho]) is the classical Coulomb energy, and (E{xc}[\rho]) is the exchange-correlation functional that incorporates all quantum many-body effects [13]. The accuracy of DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for (E{xc}[\rho]), whose exact form remains unknown.

The development of exchange-correlation functionals has followed an evolutionary path often described as "Jacob's Ladder" or "Charlotte's Web," reflecting the complex interconnectedness of different approaches [13]. These include:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Models the electron density as a uniform electron gas, providing simple but limited accuracy.

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates the gradient of the electron density ((\nabla\rho)) to account for inhomogeneities, offering improved accuracy for molecular geometries.

- meta-GGA (mGGA): Includes the kinetic energy density ((\tau(r))) for better energetics.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix a fraction of Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange to address self-interaction error, significantly improving accuracy.

- Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH): Employ distance-dependent mixing of Hartree-Fock and DFT exchange for better performance with charge-transfer species and excited states [13].

Coupled-Cluster Theory (CCSD(T))

The CCSD(T) method represents a highly accurate wavefunction-based approach to solving the electronic Schrödinger equation. Often called the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry [9], it systematically accounts for electron correlation effects through a sophisticated treatment of electronic excitations. The method includes all single and double excitations (CCSD) exactly, and incorporates an estimate of connected triple excitations ((T)) through perturbation theory. This combination provides exceptional accuracy for molecular energies and properties, typically approaching chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol) for many systems.

The primary limitation of CCSD(T) is its computational cost, which scales as the seventh power of the system size ((O(N^7))). As MIT Professor Ju Li notes, "If you double the number of electrons in the system, the computations become 100 times more expensive" [9]. This steep scaling has traditionally restricted CCSD(T) applications to molecules with approximately 10 atoms or fewer, though recent advances in machine learning and computational hardware are progressively expanding these limits.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CCSD(T) and DFT

| Feature | CCSD(T) | DFT |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Wavefunction theory | Electron density |

| Computational Scaling | (O(N^7)) | (O(N^3)) to (O(N^4)) |

| System Size Limit | Traditionally ~10 atoms, expanding with new methods | Hundreds to thousands of atoms |

| Typical Accuracy | 1-5 kcal/mol for thermochemistry | Varies widely (3-20 kcal/mol) depending on functional |

| Treatment of Electron Correlation | Systematic inclusion via excitation hierarchy | Approximated through exchange-correlation functional |

| Cost-Benefit Trade-off | High accuracy, high cost | Variable accuracy, lower cost |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Benchmarking Against Experimental Data

Rigorous evaluation of CCSD(T) and DFT performance requires comparison against reliable experimental data or highly accurate theoretical references. One comprehensive study compared these methods for bond dissociation energies in 3d transition metal-containing diatomic molecules using the 3dMLBE20 database [10]. The protocol involved:

- System Selection: 20 diatomic molecules containing 3d transition metals with high-quality experimental bond energies.

- Method Application: Calculation of bond energies using 42 different exchange-correlation functionals and CCSD(T) with extended basis sets.

- Error Analysis: Computation of mean unsigned deviations (MUD) from experimental values for quantitative accuracy assessment.

- Diagnostic Evaluation: Application of T1, M, and B1 diagnostics to identify systems with potential multi-reference character where single-reference methods might fail [10].

This study revealed that while CCSD(T) generally showed smaller average errors than most functionals, the improvement was less than one standard deviation of the mean unsigned deviation. Surprisingly, nearly half of the tested functionals performed closer to experiment than CCSD(T) for the same molecules with the same basis sets [10].

CCSD(T) as a Theoretical Benchmark

When experimental data is limited or unreliable, CCSD(T) with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation often serves as the reference method for evaluating DFT performance. A representative study of biologically relevant catecholic systems employed this protocol [11] [12]:

- System Selection: 32 complexes containing catechol, dinitrocatechol, dopamine, and DOPAC with various counter-molecules, representing metal-coordination, hydrogen-bonding, and π-stacking interactions.

- Reference Calculations: Optimization at CCSD/cc-pVDZ or MP2/cc-pVDZ levels, followed by CCSD(T)/CBS calculations for complexation energies.

- DFT Evaluation: Comparison of 21 DFT functionals with triple and quadruple-ζ basis sets against the CCSD(T)/CBS benchmarks.

- Performance Ranking: Identification of top-performing functionals (MN15, M06-2X-D3, ωB97XD, ωB97M-V, and CAM-B3LYP-D3) based on deviation from CCSD(T) references [12].

Similar protocols have been applied to aluminum clusters [14] and zirconocene polymerization catalysts [15], demonstrating the versatility of CCSD(T) benchmarking across diverse chemical systems.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Accuracy Across Chemical Systems

The relative performance of CCSD(T) and DFT varies significantly across different chemical systems and properties. Comprehensive benchmarking reveals several important patterns:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Chemical Systems

| System Type | CCSD(T) Performance | Top-Performing DFT Functionals | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3d Transition Metal Bonds [10] | MUD = ~4.7 kcal/mol | B97-1 (MUD = 4.5 kcal/mol), PW6B95 (MUD = 4.9 kcal/mol) | Bond dissociation energies vs. experiment |

| Biologically Relevant Catechols [12] | Serves as reference standard | MN15, M06-2X-D3, ωB97XD, ωB97M-V, CAM-B3LYP-D3 | Complexation energies vs. CCSD(T)/CBS |

| Aluminum Clusters [14] | Close agreement with experiment for IP/EA | PBE0 (errors 0.14-0.15 eV for IP/EA) | Ionization potentials (IP) and electron affinities (EA) |

| Zirconocene Catalysts [15] | Suggests revision of experimental BDEs | Varies; some functionals accurate for redox potentials | Redox potentials, bond dissociation energies (BDEs) |

For aluminum clusters (Alₙ, n=2-9), CCSD(T) and specific functionals like PBE0 show remarkable accuracy for ionization potentials and electron affinities, with average errors of only 0.11-0.15 eV compared to experimental data [14]. In zirconocene catalysis research, CCSD(T) calculations suggested that experimental bond dissociation enthalpies might require revision, highlighting its role not just in validation but in potentially correcting experimental measurements [15].

Limitations and Systematic Errors

Both methods exhibit specific limitations that researchers must consider:

CCSD(T) Limitations:

- Computational Cost: The steep scaling limits application to large systems, though machine learning approaches are addressing this [9].

- Transition Metal Challenges: For 3d transition metal systems, CCSD(T) does not consistently outperform all DFT functionals, with some studies showing multiple functionals achieving comparable or better accuracy [10].

- Multi-Reference Systems: Single-reference CCSD(T) struggles with systems exhibiting strong static correlation, such as bond dissociation or diradicals.

DFT Limitations:

- Functional Dependence: Accuracy varies dramatically across functionals, with no universal functional optimal for all systems.

- Self-Interaction Error: Pure functionals incorrectly model electron self-repulsion, affecting reaction barriers and charge-transfer states.

- Density-Driven Errors: Approximate functionals can yield inaccurate electron densities, propagating errors to computed properties [16].

- Dispersion Interactions: Standard functionals poorly describe van der Waals forces, requiring empirical corrections (-D3, -D4) for accurate non-covalent interactions.

Recent Advances and Future Directions

Machine Learning Accelerations

Recent breakthroughs in machine learning (ML) are dramatically expanding the applicability of high-accuracy quantum chemical methods. MIT researchers have developed a novel neural network architecture called "Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network" (MEHnet) that leverages CCSD(T) calculations as training data [9] [17]. This approach:

- Extends System Size: Enables CCSD(T)-level accuracy for thousands of atoms, far beyond the traditional 10-atom limit.

- Multi-Property Prediction: Uses a single model to evaluate multiple electronic properties simultaneously, including dipole moments, polarizability, and excitation gaps.

- Accelerates Calculations: After training, the neural network performs calculations much faster than conventional CCSD(T) while maintaining high accuracy [9].

This ML framework demonstrates particular strength in predicting excited state properties and infrared absorption spectra, traditionally challenging for computational methods [9]. Similar approaches like DeepH show promise in learning the DFT Hamiltonian to accelerate electronic structure calculations [17].

Functional Development and Density-Corrected DFT

DFT development continues to advance, with researchers addressing fundamental limitations:

- Density-Corrected DFT (DC-DFT): This approach separates errors into functional-driven and density-driven components, often using Hartree-Fock densities instead of self-consistent DFT densities to reduce errors [16].

- Range-Separated Hybrids: Improved treatment of long-range interactions benefits charge-transfer systems and excited states.

- System-Specific Optimization: Benchmarks drive the identification of optimal functionals for specific chemical systems, such as the recommended functionals for catechol-protein interactions [12].

The field continues to debate whether DFT is approaching the limit of general-purpose accuracy [17], though specialized functionals for specific applications continue to emerge.

Computational Toolkit for Researchers

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources and Their Applications

| Tool/Resource | Function/Role | Representative Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Coupled-Cluster Theory | High-accuracy reference calculations | Benchmarking, small system validation [9] |

| Hybrid DFT Functionals | Balance of accuracy and efficiency | Geometry optimization, medium-sized systems [13] |

| Range-Separated Hybrids | Accurate charge-transfer and excited states | Spectroscopy, reaction barriers [13] |

| Empirical Dispersion Corrections | Account for van der Waals interactions | Non-covalent complexes, supramolecular chemistry [12] |

| Local CCSD(T) Methods (e.g., DPLNO) | Reduced computational cost for correlation methods | Larger systems with correlation treatment [12] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Acceleration of ab initio calculations | Large systems, molecular dynamics [9] [17] |

Selection Guidelines for Computational Studies

Choosing between CCSD(T) and DFT involves careful consideration of multiple factors:

- System Size: For small molecules (<20 atoms) where highest accuracy is critical, CCSD(T) is preferred if computationally feasible. For larger systems, DFT becomes necessary.

- Property Type: Energetics and spectroscopic properties often benefit from CCSD(T) accuracy, while geometries can be well-described by appropriate DFT functionals.

- Chemical System: Transition metals and systems with potential multi-reference character require careful method selection, preferably based on existing benchmarks for similar compounds.

- Resource Constraints: Consider computational resources, with DFT being more accessible for high-throughput screening.

For biological systems involving catecholamines, the recommended functionals (MN15, M06-2X-D3, ωB97XD, ωB97M-V, CAM-B3LYP-D3) provide the best balance of accuracy and efficiency based on CCSD(T) benchmarks [12].

The complementary roles of CCSD(T) and DFT in computational chemistry continue to evolve through rigorous benchmarking and methodological innovations. CCSD(T) remains the uncontested gold standard for accurate thermochemical calculations, particularly for systems where experimental data is limited or questionable. Its role in generating benchmark datasets for functional evaluation is indispensable. Meanwhile, DFT offers remarkable versatility and efficiency for diverse applications across chemistry, biology, and materials science, though with accuracy that varies significantly across functional choices.

Future advancements will likely blur the boundaries between these approaches, with machine learning methods leveraging CCSD(T) accuracy for larger systems [9] and DFT development addressing fundamental limitations like self-interaction error and density-driven inaccuracies [16]. For researchers in drug development and materials design, this evolving landscape offers increasingly reliable tools for molecular property prediction, guided by comprehensive benchmarks that critically evaluate performance across chemical space. The continued synergy between high-accuracy wavefunction methods, efficient density functionals, and emerging machine learning approaches promises to expand the frontiers of computational chemistry, enabling more accurate predictions and novel discoveries across scientific disciplines.

In the rigorous fields of computational chemistry and machine learning, benchmark datasets provide the foundational ground truth for validating new methods, comparing algorithmic performance, and ensuring scientific reproducibility. These repositories move research beyond abstract claims to quantifiable, comparable results. Within computational chemistry, the NIST Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database (CCCBDB) has long served as a fundamental resource for validating thermochemical calculations [18]. In the broader ecosystem of graph-based machine learning, the Open Graph Benchmark (OGB) offers a standardized platform for evaluating models on realistic and diverse graph-structured data [19]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these and other key repositories, framing them within the workflow of a computational chemistry researcher. It presents structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows to assist scientists in selecting the appropriate benchmarks for their specific research and development goals, particularly in drug discovery and materials science.

Detailed Repository Profiles

NIST CCCBDB: Maintained by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, this database is a curated collection of experimental and ab initio thermochemical properties for a selected set of gas-phase molecules [6] [18]. Its primary goal is to provide benchmark data for evaluating computational methods, allowing direct comparison between different ab initio methods and experimental data. It contains data for 580 neutral gas-phase species, focusing on properties such as vibrational frequencies, bond energies, and enthalpies of formation [18]. A key feature includes vibrational scaling factors for calibrating calculated spectra against experimental data [20].

Open Graph Benchmark (OGB): A community-driven initiative providing realistic, large-scale, and diverse benchmark datasets for machine learning on graphs [19]. OGB is not specific to chemistry but provides a flexible framework for benchmarking graph neural networks (GNNs) on tasks such as molecular property prediction, link prediction, and graph classification. It features automated data loaders, standardized dataset splits, and unified evaluators to ensure fair and reproducible model comparison [19].

Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25): A recent, massive-scale dataset from Meta's FAIR team, comprising over 100 million high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory [21]. It covers an unprecedented diversity of chemical structures, with special focus on biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes. OMol25 is 10–100 times larger than previous state-of-the-art molecular datasets and is designed to train and benchmark advanced neural network potentials (NNPs) [21].

OGDOS (Open Graph Dataset Organized by Scales): This dataset addresses a specific gap by organizing 470 graphs explicitly by node count (100 to 200,000) and edge-to-node ratio (1 to 10) [22]. It combines scale-aligned real-world and synthetic graphs, providing a versatile resource for evaluating graph algorithms' scalability and computational complexity, which can be pertinent for method development in chemical informatics [22].

Quantitative Comparison of Key Repositories

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Benchmark Repositories for Computational Chemistry

| Repository Name | Primary Focus | Data Type | Data Scale | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST CCCBDB | Thermochemistry & Spectroscopy [18] | Energetic, structural & vibrational properties [20] | ~580 gas-phase molecules [18] | Method validation, vibrational scaling factors [20] |

| OGB | General graph ML benchmarks [19] | Molecular & non-molecular graphs [19] | Multiple large-scale datasets [19] | Benchmarking GNNs on molecular property prediction [19] |

| Meta OMol25 | High-throughput quantum chemistry [21] | Molecular structures & energies [21] | >100 million calculations [21] | Training & benchmarking Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [21] |

| OGDOS | Graph algorithm scalability [22] | Scale-standardized graphs [22] | 470 pre-defined scale levels [22] | Testing scalability of graph algorithms [22] |

Table 2: Detailed Comparison for Computational Chemistry Applications

| Feature | NIST CCCBDB | OGB | Meta OMol25 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Levels | Multiple (e.g., G2, DFT, MP2) [18] | Not Specified (varies by source dataset) | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD (uniform) [21] |

| Property Types | Enthalpy, vibration, geometry, energy [20] | Molecular properties, node/link attributes [19] | Molecular energies & forces [21] |

| Evaluation Rigor | High (NIST standard, experimental comparison) [6] | High (unified evaluators, leaderboards) [19] | High (uniform high-level theory) [21] |

| Ease of Use | Web interface, downloadable data [18] | Automated data loaders (PyTorch/DGL) [19] | Pre-trained models, HuggingFace [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Workflows

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Computational Chemistry Method using NIST CCCBDB

This protocol describes how to use the NIST CCCBDB to validate the accuracy of a quantum chemistry method for predicting molecular enthalpies of formation.

- Step 1: Define the Benchmark Set. Select a relevant set of molecules from the CCCBDB. The selection can be based on molecular size, presence of specific functional groups, or elements of interest to match the intended application domain of the method being tested [18].

- Step 2: Calculate Target Properties. Perform quantum chemical calculations for all molecules in the benchmark set using the method under evaluation. The primary calculation is the molecular energy for each species at its optimized geometry.

- Step 3: Derive Thermodynamic Properties. Convert the calculated electronic energies to the target thermodynamic property, such as the enthalpy of formation at 298K. This often involves calculating vibrational frequencies to determine zero-point energies and thermal corrections, and applying atom equivalents [20].

- Step 4: Compare and Analyze. Retrieve the corresponding experimental and/or high-level theoretical values from the CCCBDB. Calculate error metrics (e.g., Mean Absolute Error, Root Mean Square Error) between the calculated values and the benchmark data to quantify the method's accuracy [18] [20].

Figure 1: Workflow for benchmarking a computational method with NIST CCCBDB.

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Graph Neural Network using OGB

This protocol outlines the process of using the Open Graph Benchmark to evaluate the performance of a Graph Neural Network on a molecular property prediction task.

- Step 1: Select an OGB Dataset. Choose an OGB dataset relevant to the research question, such as

ogbg-molhivorogbg-molpcba, which are designed for predicting molecular properties from graph structure [19]. - Step 2: Utilize Data Loader. Use the OGB data loader to download the dataset and obtain a standardized data split (training, validation, test). The data loader automatically provides the graph data in a format compatible with popular deep learning frameworks like PyTorch Geometric and DGL [19].

- Step 3: Train the Model. Train the GNN model using the training set. Perform model selection and hyperparameter tuning based on the performance on the provided validation set.

- Step 4: Evaluate on Test Set. Use the OGB Evaluator to assess the final model's performance on the held-out test set. The evaluator ensures standardized and comparable metrics (e.g., ROC-AUC), which can be submitted to the public leaderboard [19].

Figure 2: Workflow for evaluating a Graph Neural Network with OGB.

Table 3: Key Tools and Resources for Computational Benchmarking

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code (e.g., Gaussian, GAMESS) | Performs ab initio calculations to compute molecular energies and properties. | Generating data for method validation against CCCBDB or OMol25. |

| Graph Neural Network Library (e.g., DGL, PyTorch Geometric) | Provides building blocks for implementing and training GNNs. | Developing models for molecular property prediction on OGB datasets [19]. |

| OGB Data Loader & Evaluator | Automates dataset access and ensures standardized evaluation. | Guaranteeing fair and reproducible benchmarking on OGB tasks [19]. |

| Neural Network Potential (e.g., eSEN, UMA) | Fast, accurate model for molecular energy surfaces. | Leveraging pre-trained models from OMol25 for molecular dynamics [21]. |

| Vibrational Scaling Factors (from CCCBDB) | Calibrates computed vibrational frequencies to match experiment. | Correcting systematic errors in DFT frequency calculations [20]. |

The landscape of benchmark repositories is evolving to meet the demands of increasingly complex computational methods. Established resources like the NIST CCCBDB remain indispensable for fundamental validation of quantum chemical methods, providing trusted reference data critical for method development [18]. Meanwhile, newer, large-scale initiatives like Meta's OMol25 are shifting the paradigm, providing massive, high-quality datasets that enable the training of powerful AI-driven models, such as neural network potentials, which are poised to dramatically accelerate molecular simulation [21]. Frameworks like the Open Graph Benchmark provide the standardized playground necessary for the rigorous and fair comparison of these emerging machine learning approaches on graph-structured molecular data [19].

The trend is clear: the future of benchmarking in computational chemistry involves a blend of high-accuracy reference data, large-scale diverse datasets for training data-hungry models, and robust, community-adopted evaluation platforms. As these resources mature and become more integrated, they will continue to be the bedrock upon which reliable, reproducible, and impactful computational research in chemistry and drug discovery is built.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three landmark datasets—OMol25, MSR-ACC/TAE25, and nablaDFT—that are shaping the development of computational chemistry methods. For researchers in drug development and materials science, these resources represent critical infrastructure for training and benchmarking machine learning potentials and quantum chemical methods.

The table below summarizes the core attributes of the three datasets, highlighting their distinct design goals and technical specifications.

| Feature | OMol25 (Open Molecules 2025) | MSR-ACC/TAE25 (Microsoft Research) | nablaDFT / ∇²DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Content | Molecular energies, forces, and properties for diverse molecular systems [23] [21] | Total Atomization Energies (TAEs) for small molecules [24] [25] | Conformational energies, forces, Hamiltonian matrices, and molecular properties for drug-like molecules [26] [27] |

| Reference Method | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD (Density Functional Theory) [21] | CCSD(T)/CBS (Coupled-Cluster) via W1-F12 protocol [24] [25] | ωB97X-D/def2-SVP (Density Functional Theory) [27] |

| Chemical Space Focus | Extreme breadth: biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes, 83 elements, systems up to 350 atoms [23] [21] | Broad, fundamental chemical space for elements up to argon [24] [25] | Drug-like molecules [26] [27] |

| Key Differentiator | Unprecedented size and chemical diversity, includes solvation, variable charge/spin states [21] [3] | High-accuracy "sub-chemical accuracy" (±1 kcal/mol) reference data [24] [25] | Includes relaxation trajectories and wavefunction-related properties for a substantial number of molecules [27] |

| Dataset Size | >100 million calculations [23] [21] | 76,879 TAEs [24] [25] | Large-scale; based on and expands the original nablaDFT dataset [26] [27] |

Performance Benchmarking

The utility of a dataset is ultimately proven by the performance of models trained on it. The following table summarizes quantitative benchmarks for models derived from these datasets compared to traditional computational methods.

| Method / Model | Dataset / Theory | Benchmark Task | Performance Metrics | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN-S, UMA-S, UMA-M [28] | OMol25 | Experimental Reduction Potentials (Organometallic Set) [28] | MAE: 0.262-0.365 V (Best: UMA-S) [28] | As accurate or better than low-cost DFT (B97-3c, MAE: 0.414 V) and SQM (GFN2-xTB, MAE: 0.733 V) for organometallics. [28] |

| eSEN-S, UMA-S, UMA-M [28] | OMol25 | Experimental Reduction Potentials (Main-Group Set) [28] | MAE: 0.261-0.505 V (Best: UMA-S) [28] | Less accurate than low-cost DFT (B97-3c, MAE: 0.260 V) for main-group molecules. [28] |

| OMol25-trained Models [21] | OMol25 | Molecular Energy Accuracy (GMTKN55 WTMAD-2, filtered) [21] | Near-perfect performance [21] | Exceeds previous state-of-the-art neural network potentials and matches high-accuracy DFT. [21] |

| Skala Functional [24] | MSR-ACC (Training) | Atomization Energies (Experimental Accuracy) [24] | Reaches experimental accuracy [24] | Demonstrates use of high-accuracy dataset to develop a machine-learned exchange-correlation functional. [24] |

| nablaDFT-based Models [26] | nablaDFT | Multi-molecule Property Estimation [26] | Significant accuracy drop in multi-molecule vs. single-molecule setting [26] | Highlights the need for diverse datasets and robust benchmarks to test generalization. [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

A typical workflow for benchmarking computational models against experimental data involves several key stages, from data preparation to quantitative analysis. The diagram below illustrates this process for evaluating reduction potentials and electron affinities.

Detailed Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: The process begins with acquiring a curated experimental dataset, such as the one compiled by Neugebauer et al. for reduction potentials, which provides the initial 3D geometries of molecules in their non-reduced and reduced states [28].

- Geometry Optimization: The initial structures are optimized using the computational method being evaluated (e.g., a Neural Network Potential or a DFT functional). This is typically done using energy minimization algorithms to find the lowest-energy conformation [28].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: A more precise, single-point energy calculation is performed on the optimized geometry. For properties like reduction potential that occur in solvent, an implicit solvation model (e.g., CPCM-X) is applied at this stage to correct the electronic energy for solvent effects [28].

- Property Calculation: The target property is computed from the calculated energies. For electron affinity, this is the gas-phase energy difference between the neutral and anionic species. For reduction potential, it is the difference in solvent-corrected electronic energy between the reduced and non-reduced structures, converted to volts [28].

- Statistical Comparison: The final step involves comparing the computationally predicted values to the experimental data using standard statistical metrics, including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R²) to quantify accuracy and precision [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key software and computational tools that are essential for working with these benchmark datasets and conducting related research.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Datasets |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [29] [21] | Machine learning models trained on quantum chemical data to predict molecular energies and forces at a fraction of the cost of full calculations. [29] [21] | Primary models trained on and evaluated with these datasets (e.g., eSEN, UMA models on OMol25). [21] [28] |

| Implicit Solvation Models (e.g., CPCM-X) [28] | A computational method to approximate the effects of a solvent environment on a molecule's energy and properties without explicitly modeling solvent molecules. [28] | Critical for accurately predicting solution-phase properties like reduction potential when benchmarking against experimental data. [28] |

| Geometry Optimization Libraries (e.g., geomeTRIC) [28] | Software libraries that implement algorithms to find molecular geometries that correspond to local energy minima on the potential energy surface. [28] | Used in the standard workflow to relax initial molecular structures before calculating single-point energies for property prediction. [28] |

| Coupled-Cluster Theory (CCSD(T)) [24] [25] | A high-level, computationally expensive quantum chemistry method often considered the "gold standard" for achieving high accuracy, especially for main-group elements. [24] [25] | Serves as the high-accuracy reference method for the MSR-ACC/TAE25 dataset, providing benchmark-quality data. [24] [25] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [24] [21] | A widely used computational method for electronic structure calculations that balances cost and accuracy. Serves as the source of data for OMol25 and nablaDFT. [24] [21] | The source theory for the OMol25 and nablaDFT datasets. Also used as a baseline for comparing the accuracy of new ML models. [21] [28] |

| Dataset Curation Tools (e.g., MEHC-Curation) [30] | Software frameworks designed to automate the process of validating, cleaning, and normalizing molecular datasets (e.g., removing invalid structures and duplicates). [30] | Ensures the high quality of input data for training and benchmarking, which is vital for model reliability and performance. [30] |

The concept of "chemical space"—the theoretical multidimensional space encompassing all possible molecules and compounds—serves as a core principle in cheminformatics and molecular design [31]. For researchers in computational chemistry and drug development, assessing and maximizing the coverage of this vast space is critical for the discovery of novel biologically active small molecules [32]. The structural and functional diversity of a molecular library directly correlates with its potential to modulate a wide range of biological targets, including those traditionally considered "undruggable" [32]. This guide objectively compares contemporary approaches and benchmark datasets used to quantify and expand diversity in elements and molecular systems, providing a foundational resource for methods research in computational chemistry.

Defining and Quantifying Diversity in Chemical Space

Dimensions of Chemical Diversity

The structural diversity of a molecular library is not a monolithic concept but is composed of several distinct components [32]:

- Skeletal (Scaffold) Diversity: The presence of distinct molecular skeletons or core structures. This is considered one of the most crucial factors for functional diversity, as different scaffolds present chemical information in different three-dimensional arrangements.

- Appendage Diversity: Variation in structural moieties or building blocks attached to a common molecular scaffold.

- Functional Group Diversity: Variation in the reactive chemical functional groups present within the molecules.

- Stereochemical Diversity: Variation in the three-dimensional orientation of atoms and potential macromolecule-interacting elements.

- Elemental Diversity: The inclusion of atoms from across the periodic table, which is particularly important for covering inorganic complexes and organometallic species.

Methodologies for Assessing Diversity

Cheminformatic Approaches

Traditional approaches to quantifying molecular diversity often rely on molecular fingerprints and similarity indices. The iSIM framework provides an efficient method for calculating the intrinsic similarity of large compound libraries with O(N) complexity, bypassing the steep O(N²) computational cost of traditional pairwise comparisons [31]. This method calculates the average of all distinct pairwise Tanimoto comparisons (iT), where lower iT values indicate a more diverse collection [31].

Complementary to this global diversity measure, the concept of complementary similarity helps identify regions within the chemical space. Molecules with low complementary similarity are central ("medoid-like") to the library, while those with high values are peripheral outliers [31]. The BitBIRCH clustering algorithm further enables granular analysis of chemical space by efficiently grouping compounds based on structural similarity, adapting the BIRCH algorithm for binary fingerprints and Tanimoto similarity [31].

Linguistic Analysis of Chemical Space

An innovative approach applies computational linguistic analysis to chemistry by treating maximum common substructures (MCS) as "chemical words" [33]. The distribution of these MCS "words" in molecular collections follows Zipfian power laws similar to natural language [33].

Linguistic metrics adapted for chemical analysis include:

- Type-Token Ratio (TTR): The ratio of unique MCS "words" to the total number of MCS "words" in a collection. Natural products show greater TTR (0.2051) than approved drugs (0.1469) or random molecule samples (0.1058), indicating higher linguistic richness [33].

- Moving Window TTR (MWTTR): Addresses TTR's sensitivity to text length by calculating TTR within sliding windows across the "text" of chemical words [33].

- Vocabulary Growth Curves: Plot the accumulation of new MCS "words" as more molecules are added to a collection, following Herdan's law (V_R(n) = Kn^β) [33].

These linguistic measures provide chemically intuitive insights into diversity, as MCS often represent recognizable structural motifs like steroid frameworks or penicillin cores that chemists use for categorization [33].

Comparative Analysis of Diversity-Oriented Strategies

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS)

Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) aims to efficiently generate structural diversity, particularly scaffold diversity, through chemical synthesis [32]. Unlike traditional combinatorial chemistry that focuses on appendage diversity around a common core, DOS deliberately incorporates strategies to generate multiple distinct molecular scaffolds. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring underrepresented regions of chemical space and identifying novel bioactive compounds, especially for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions [32].

Combined Computational and Empirical Screening

A hybrid approach combining computational docking with empirical fragment screening demonstrates how to maximize chemotype coverage. In a study against AmpC β-lactamase [34]:

- A 1,281-fragment NMR screen identified 9 inhibitory fragments with high topological novelty (average Tanimoto coefficient 0.21 to known inhibitors).

- Subsequent docking of 290,000 commercially available fragments identified additional inhibitors (KI values 0.03-1.0 mM) that filled "chemotype holes" in the empirical library.

- Crystallography confirmed novel binding modes for the docking-derived fragments, validating this complementary approach.

This strategy addresses the fundamental limitation that even diverse fragment libraries cannot fully represent chemical space; calculations suggest representing the fragment substructures of known biogenic molecules would require a library of over 32,000 fragments [34].

Benchmark Datasets for Chemical Space Coverage

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Molecular Datasets

| Dataset | Size | Element Coverage | Structural Diversity Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 [3] [35] | >100 million DFT calculations | 83 elements, including heavy metals | Biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes; 2-350 atoms per snapshot; charges -10 to +10 | Training MLIPs for materials science, drug discovery, energy technologies |

| ChEMBL [31] | >20 million bioactivities; >2.4 million compounds | Primarily drug-like organic compounds | Bioactive small molecules with target annotations | Drug discovery, bioactivity prediction, cheminformatics |

| PubChem [31] | Not specified in results | Broad organic coverage | Diverse small molecules with biological properties | Chemical biology, virtual screening |

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

Table 2: Performance of OMol25-Trained Models on Charge-Related Properties

| Method | Dataset | MAE (V) | RMSE (V) | R² | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c (DFT) [28] | Main-group (OROP) | 0.260 | 0.366 | 0.943 | Traditional DFT performs well on main-group compounds |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.414 | 0.520 | 0.800 | Reduced accuracy for organometallics | |

| GFN2-xTB (SQM) [28] | Main-group (OROP) | 0.303 | 0.407 | 0.940 | Competitive on main-group systems |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.733 | 0.938 | 0.528 | Poor performance on organometallics | |

| UMA-S (OMol25) [28] | Main-group (OROP) | 0.261 | 0.596 | 0.878 | Comparable to DFT for main-group |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.262 | 0.375 | 0.896 | Superior for organometallics | |

| eSEN-S (OMol25) [28] | Main-group (OROP) | 0.505 | 1.488 | 0.477 | Lower accuracy for main-group |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.312 | 0.446 | 0.845 | Good organometallic performance |

Experimental Protocols for Diversity Assessment

Protocol 1: iSIM Framework for Library Diversity Quantification

Objective: Quantify the intrinsic diversity of large molecular libraries using linear-scaling computational methods [31].

Workflow:

- Molecular Representation: Encode all molecular structures in the library as finite bit-string fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, Morgan fingerprints).

- Matrix Construction: Arrange all fingerprints into a matrix where rows represent compounds and columns represent structural features.

- Column Sum Calculation: For each column (feature) in the fingerprint matrix, calculate the number of "on" bits (k_i).

- iT Calculation: Compute the intrinsic Tanimoto similarity (iT) using the formula:

iT = Σ[k_i(k_i-1)/2] / Σ[k_i(k_i-1)/2 + k_i(N-k_i)]where N is the number of molecules in the library. - Diversity Interpretation: Lower iT values indicate greater library diversity. This global measure can be supplemented with complementary similarity analysis to identify central and outlier regions of the chemical space.

Protocol 2: Linguistic Analysis of Chemical Collections

Objective: Apply computational linguistics methods to quantify the diversity of molecular libraries using maximum common substructures (MCS) as "chemical words" [33].

Workflow:

- Pairwise MCS Calculation: For all molecule pairs in the collection (or a representative sample for large libraries), compute the maximum common substructures using algorithms available in toolkits like RDKit.

- Vocabulary Construction: Compile all unique MCS "words" from the pairwise comparisons, creating the chemical "vocabulary" for the library.

- Frequency-Rank Distribution: Plot the frequency of each MCS word against its popularity rank. Chemically diverse libraries typically show Zipfian power law distributions.

- Type-Token Ratio Calculation: Calculate TTR as the ratio of unique MCS words to total MCS words for the collection. For more robust analysis, use Moving Window TTR (MWTTR) with fixed window sizes.

- Vocabulary Growth Analysis: Plot the accumulation of new MCS words as more molecules are added to the collection, fitting to Herdan's law (V_R(n) = Kn^β) to characterize diversity scaling.

Protocol 3: BitBIRCH Clustering for Chemical Space Navigation

Objective: Efficiently cluster large molecular libraries to identify natural groupings and assess coverage of chemical space [31].

Workflow:

- Fingerprint Generation: Convert all molecular structures to binary fingerprints.

- Tree Construction: Build a clustering tree where each node represents a potential cluster of similar molecules based on fingerprint similarity.

- Incremental Clustering: Process molecules through the tree structure, updating cluster features at each node without requiring all pairwise comparisons.

- Cluster Extraction: From the final tree, extract clusters of molecules with high internal similarity using the Tanimoto coefficient as the distance metric.

- Diversity Assessment: Analyze the distribution of cluster sizes and inter-cluster distances. A more diverse library will typically show more clusters with greater separation between them.

Visualization of Chemical Space Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for comprehensive chemical space coverage assessment, combining the experimental protocols detailed in this guide:

Table 3: Key Resources for Chemical Space Analysis

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [3] [35] | Computational Dataset | Training machine learning interatomic potentials with DFT-level accuracy | Predicting molecular properties across diverse elements and systems |

| iSIM Framework [31] | Computational Algorithm | O(N) calculation of intrinsic molecular similarity | Diversity quantification of large compound libraries |

| BitBIRCH Algorithm [31] | Clustering Tool | Efficient clustering of large molecular libraries using fingerprints | Identifying natural groupings and gaps in chemical space |

| MCS-based Linguistic Tools [33] | Analytical Framework | Applying natural language processing to chemical structures | Chemically intuitive diversity assessment and library comparison |

| ChEMBL Database [31] | Chemical Database | Manually curated bioactive molecules with target annotations | Drug discovery, bioactivity modeling, focused library design |

| DOS Libraries [32] | Synthetic Compounds | Collections with high scaffold diversity using diversity-oriented synthesis | Targeting underexplored biological targets and protein-protein interactions |

The comprehensive assessment of chemical space coverage requires a multifaceted approach combining diverse methodologies. As evidenced by the comparative data, newer strategies like the OMol25 dataset demonstrate particular strength in modeling complex organometallic systems, while traditional DFT maintains advantages for main-group compounds [28]. The integration of cheminformatic approaches like iSIM and BitBIRCH with innovative linguistic analyses provides robust tools for quantifying library diversity [31] [33]. For researchers pursuing novel biological probes and therapeutics, particularly against challenging targets, strategies that maximize scaffold diversity—such as DOS and combined computational/empirical screening—offer enhanced coverage of bioactive chemical space [34] [32]. The continued development and benchmarking of these approaches against standardized datasets will remain crucial for advancing computational chemistry methods and accelerating drug discovery.

From Data to Discovery: Applying Benchmark Datasets in Method Development and AI Training

Training Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) for Faster-than-DFT Simulations

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) have emerged as a transformative tool in computational chemistry and materials science, offering to replace computationally expensive quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) with accelerated simulations while maintaining near-quantum accuracy. The core promise of MLPs lies in their ability to learn the intricate relationship between atomic configurations and potential energy from existing DFT data, then generalize to predict energies and forces for new, unseen structures at a fraction of the computational cost. Recent advances have demonstrated speed improvements of up to 10,000 times compared to conventional DFT calculations while preserving high accuracy, enabling previously infeasible simulations of complex molecular systems and extended timescales [3].

The performance and generalizability of any MLP are fundamentally constrained by the quality, breadth, and chemical diversity of the datasets used for its training. This creates an intrinsic link between benchmark dataset development and progress in the MLP field. Historically, MLP development was hampered by limited datasets covering narrow chemical spaces. The recent release of unprecedented resources like the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset, with over 100 million molecular snapshots, represents a paradigm shift, providing the comprehensive data foundation needed to develop truly generalizable MLPs [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary MLP approaches, their performance against DFT and experimental benchmarks, and the experimental protocols defining their capabilities within this new data-rich environment.

A Comparative Analysis of Modern Machine Learning Potentials

Taxonomy and Architectural Trade-offs

MLPs can be categorized by their underlying machine learning algorithm and the type of descriptor used to represent atomic environments. The choice of architecture involves significant trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency, data requirements, and transferability to unseen chemical spaces [36].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major MLP Architectures

| Category | Description | Representative Examples | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM-GD (Kernel Method with Global Descriptor) | Uses kernel-based learning (e.g., KRR, GPR) with a descriptor representing the entire molecule [36]. | Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) with Coulomb Matrix (CM) or Bag-of-Bonds (BoB) [36] [37]. | High accuracy for small, rigid molecules; strong performance in data-efficient regimes [38]. | Poor scalability to large systems; limited generalizability due to global representation [36] [37]. |

| KM-fLD (Kernel Method with fixed Local Descriptor) | Employs kernel methods with descriptors that represent the local chemical environment of each atom [36]. | Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) with Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [37]. | More transferable than KM-GD; better for systems with varying molecular sizes. | Computationally intensive for training on very large datasets. |

| NN-fLD (Neural Network with fixed Local Descriptor) | Uses neural networks with hand-crafted local atomic environment descriptors [36]. | ANI (ANI-1, ANI-2x) [37], Behler-Parrinello Neural Network Potentials. | High accuracy; faster inference than kernel methods for large systems. | Descriptor design can limit physical generality. |

| NN-lLD (Neural Network with learned Local Descriptor) | Employs deep neural networks that automatically learn optimal feature representations from atomic coordinates [36]. | SchNet [37], Deep Potential (DP) [39], Equivariant Networks (eSEN) [28]. | Excellent accuracy and scalability; superior generalizability with sufficient data. | High data requirements; computationally expensive training. |

Performance Benchmarking Against DFT and Experiment

Quantitative benchmarking is essential for evaluating MLP performance. Key metrics include the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energies and forces compared to reference DFT calculations, as well as accuracy in predicting experimentally measurable properties.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Select MLPs on Public and Application-Specific Datasets

| MLP Model | Training Dataset | Target System/Property | Reported Accuracy (vs. DFT) | Reported Accuracy (vs. Experiment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SchNet [37] | QM9 (133k small organic molecules) | Internal energy (U_0) of molecules. | MAE = 0.32 kcal/mol (≈ 0.014 eV/atom) [37]. | Not Reported. |

| ANI-nr [39] | Custom dataset for CHNO systems. | Condensed-phase organic reaction energies. | "Excellent agreement" with DFT and traditional quantum methods [39]. | "Excellent agreement" with experimental results [39]. |

| PhysNet [37] | QM9 | Internal energy (U_0) of molecules. | MAE = 0.14 kcal/mol (≈ 0.006 eV/atom) [37]. | Not Reported. |

| EMFF-2025 [39] | Custom dataset via transfer learning. | Energetic Materials (CHNO); Energy and Forces. | Energy MAE < 0.1 eV/atom; Force MAE < 2 eV/Å [39]. | Validated against experimental crystal structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition behaviors of 20 HEMs [39]. |

| OMol25-trained UMA-S [28] | OMol25 (100M+ snapshots) | Reduction Potentials (Organometallics). | Not Reported. | MAE = 0.262 V (outperformed B97-3c/GFN2-xTB DFT) [28]. |

| OMol25-trained eSEN-S [28] | OMol25 | Reduction Potentials (Organometallics). | Not Reported. | MAE = 0.312 V (outperformed GFN2-xTB) [28]. |

The data shows that modern MLPs, particularly NN-lLD models, can achieve chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol ≈ 0.043 eV/atom) on well-curated datasets like QM9. Furthermore, models trained on extensive datasets like OMol25 demonstrate remarkable performance in predicting complex electronic properties like reduction potentials, sometimes surpassing lower-rung DFT methods [28]. The application-specific potential EMFF-2025 highlights how MLPs can achieve DFT-level accuracy for energy and force predictions while successfully replicating experimental observables for a targeted class of materials [39].

Experimental Protocols for MLP Development and Validation

Workflow for Robust MLP Construction

A standardized workflow is critical for developing reliable MLPs. The process involves dataset curation, model training, validation, and deployment for simulation. The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative protocol that incorporates active learning.

Diagram 1: Workflow for constructing and validating MLPs, featuring an active learning loop.

Key Methodologies in Practice

Dataset Curation and Initial Sampling: The process begins by defining the target chemical space. Foundational datasets like QM9 (focused on small organic molecules) and the massive OMol25 (spanning biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes) serve as starting points [3] [37]. For specific applications, initial structures are sampled from relevant molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories or crystal structures. A key consideration is chemical diversity; studies show that models trained on combinatorially generated datasets (e.g., QM9) can suffer in generalizability when applied to real-world molecules (e.g., from PubChemQC), underscoring the need for diverse training data [37].

Active Learning and Uncertainty Sampling: This iterative strategy is crucial for efficient model development. A preliminary MLP (often a Gaussian Process Regression model for its native uncertainty quantification) is trained on a small initial DFT set [40]. This model then predicts energies for a vast pool of unsampled configurations, and the structures where the model is most uncertain are selected for subsequent DFT calculations [40]. These new data points are added to the training set, and the model is retrained. This loop continues until model performance converges, ensuring robust coverage of the relevant configurational space with minimal DFT cost.

Validation and Benchmarking Protocols: A final model is validated against a held-out test set of DFT calculations, reporting MAE for energies and forces. The true test is its performance in downstream MD simulations. Key validations include:

- Stability: Running multi-nanosecond MD simulations without unphysical energy drift or bond breaking.

- Property Prediction: Calculating thermodynamic, mechanical, or spectroscopic properties for comparison with experiment (e.g., crystal parameters, elastic moduli, reduction potentials) [39] [28].

- Reaction Modeling: Using methods like Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) with MLP-calculated energies to identify reaction pathways and barriers, as demonstrated in automated workflows for identifying slip pathways in materials [40].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Datasets for MLP Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to MLP Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 (Open Molecules 2025) [3] | Dataset | Provides over 100 million DFT-calculated 3D molecular snapshots. | A foundational training resource for developing general-purpose MLPs; offers unprecedented chemical diversity. |

| QM9 [37] | Dataset | A benchmark dataset of ~134k small organic molecules with up to 9 heavy atoms (C, N, O, F). | A standard benchmark for initial model testing and comparison due to its homogeneity and widespread use. |

| DP-GEN (Deep Potential Generator) [39] | Software | An automated active learning workflow for generating general-purpose MLPs. | Streamlines the process of sampling configurations, running DFT, and training robust Deep Potential models. |

| MLatom [36] | Software Package | A unified platform for running various MLP models and workflows. | Facilitates benchmarking of different MLP architectures (KM, NN) on a common platform, promoting reproducibility. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) [40] | Algorithm | A method for finding the minimum energy path (MEP) and transition state between two known stable states. | Critical for using trained MLPs to study reaction mechanisms, such as chemical reactions or material deformation pathways. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [40] | ML Algorithm | A non-parametric kernel-based probabilistic model. | Often used in active learning loops due to its inherent ability to quantify prediction uncertainty. |

The field of Machine Learning Potentials is rapidly evolving from specialized tools for narrow chemical domains toward general-purpose solutions, driven significantly by the creation of large-scale, chemically diverse benchmark datasets like OMol25. Performance comparisons consistently show that modern NN-lLD architectures, when trained on sufficient and high-quality data, can achieve accuracy on par with DFT for energy and force predictions while being orders of magnitude faster, enabling previously intractable simulations.

Future development will likely focus on improving the physical fidelity of models, particularly for long-range interactions and explicit charge/spin effects, which remain a challenge [28]. Furthermore, the integration of active learning and automated workflows will make robust MLP development accessible for a broader range of chemical systems. As these tools become more accurate and trustworthy, they are poised to become an indispensable component of the computational researcher's toolkit, accelerating discovery in materials science, catalysis, and drug development.

Parameterizing and Validating Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics

In computational chemistry, force fields form the mathematical foundation for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling the study of dynamical behaviors and physical properties of molecular systems at an atomic level [41]. The rapid expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space, particularly in drug discovery, necessitates force fields with both broad coverage and high accuracy [41]. The parameterization and validation of these force fields are critically dependent on high-quality, expansive benchmark datasets. These datasets, derived from quantum mechanics (QM) calculations and experimental data, provide the essential reference points for developing force fields that can reliably predict molecular behavior. This guide compares modern data-driven approaches with traditional force fields, providing researchers with a framework for selecting and validating methodologies based on current benchmark datasets and their performance across diverse chemical spaces.

Modern Data-Driven Parameterization Approaches

Traditional force fields often rely on look-up tables for specific chemical motifs, facing significant challenges in covering the vastness of modern chemical space. Data-driven approaches using machine learning (ML) now present a powerful alternative for generating transferable and accurate force field parameters.

Graph Neural Networks for End-to-End Parameterization

The ByteFF force field exemplifies a modern data-driven approach. It employs an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network (GNN) to predict all bonded and non-bonded molecular mechanics parameters simultaneously [41]. This method directly addresses key physical constraints: permutational invariance, chemical symmetry equivalence, and charge conservation [41].

Key Dataset and Methodology for ByteFF:

- Dataset Construction: 2.4 million unique molecular fragments were generated from the ChEMBL and ZINC20 databases, selected for diversity using criteria like aromatic rings, polar surface area, and drug-likeness (QED) [41].

- Quantum Chemistry Level: All data was generated at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level of theory, balancing accuracy and computational cost [41].

- Data Content: The training dataset includes 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries with analytical Hessian matrices and 3.2 million torsion profiles, ensuring comprehensive coverage of conformational space [41].

- Training Strategy: A carefully optimized training strategy incorporates a differentiable partial Hessian loss to improve the accuracy of vibrational parameter predictions.

Universal Models Trained on Massive-Scale Datasets

The recent Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset marks a significant shift in scale and diversity for training machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). This dataset enables the training of universal models like the Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) and eSEN models.

Key Dataset and Methodology for OMol25:

- Unprecedented Scale: OMol25 contains over 100 million quantum chemical calculations, consuming 6 billion CPU hours, which is over ten times larger than previous state-of-the-art datasets [3] [21].

- High-Quality Electronic Structure: Calculations were performed at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, a high-level density functional that avoids pathologies of earlier functionals [21].

- Expansive Chemical Coverage: The dataset specifically focuses on biomolecules (from RCSB PDB and BioLiP2), electrolytes, and metal complexes, and incorporates existing community datasets to ensure broad coverage [21].

- Architectural Innovation (UMA): The Universal Model for Atoms uses a Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) architecture, allowing it to be trained effectively on multiple datasets computed with different levels of theory and basis sets, facilitating knowledge transfer across chemical domains [21].

Fusing Simulation and Experimental Data for Enhanced Accuracy

A fused data learning strategy, which incorporates both Density Functional Theory (DFT) data and experimental measurements, can correct for known inaccuracies in DFT functionals and produce ML potentials of higher fidelity.

Key Methodology for Data Fusion:

- Dual Training Pipeline: Training alternates between a DFT trainer (a standard regression loss on energies, forces, and virial stress) and an EXP trainer (which optimizes parameters so that ML-driven simulation trajectories match experimental values) [42].

- Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe): This technique enables gradient-based optimization against experimental data without backpropagating through the entire MD simulation, making the training process computationally feasible [42].

- Target Experimental Properties: This approach has been successfully used to train a GNN potential for titanium, targeting temperature-dependent elastic constants and lattice parameters, thereby ensuring the model agrees with key thermodynamic observables [42].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this fused data learning strategy.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Force Fields

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics of modern data-driven force fields and traditional benchmarks, based on recent studies and dataset evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Modern Data-Driven Force Fields

| Force Field / Model | Training Dataset | Key Architectural Features | Reported Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| ByteFF [41] | 2.4M optimized fragments, 3.2M torsions (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) | Edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving GNN | State-of-the-art performance on relaxed geometries, torsional profiles, and conformational energies/forces for drug-like molecules. |

| eSEN (OMol25) [21] | Open Molecules 2025 (100M+ calculations, ωB97M-V) | Transformer-style, equivariant spherical harmonics | Conservative-force models outperform direct-force models. Achieves essentially perfect performance on Wiggle150 and molecular energy benchmarks. |

| UMA (OMol25) [21] | OMol25 + OC20, ODAC23, OMat24 datasets | Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) | Outperforms single-task models, demonstrating knowledge transfer across disparate datasets. |

| Fused GNN (Ti) [42] | 5704 DFT samples + Experimental elastic constants & lattice parameters | Graph Neural Network + DiffTRe | Concurrently satisfies DFT and experimental targets. Improves agreement with experiment vs. DFT-only model. |

Table 2: Performance of Traditional Force Fields for Liquid Membrane Simulations (DIPE Example) [43]

| Force Field | Density (kg/m³) at 298 K | Shear Viscosity (mPa·s) at 298 K | Key Strengths & Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | ~712 | ~0.30 | Accurate density and viscosity; recommended for thermodynamic properties of ethers. |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | ~713 | ~0.29 | Accurate density and viscosity; comparable to GAFF for ether systems. |

| CHARMM36 | ~730 | ~0.20 | Overestimates density, underestimates viscosity; less accurate for transport properties. |

| COMPASS | ~750 | ~0.17 | Significantly overestimates density, underestimates viscosity; poor for DIPE properties. |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

This section catalogs key datasets, software, and metrics that form the modern toolkit for force field parameterization and validation.

Table 3: Key Benchmark Datasets and Research Reagents

| Resource Name | Type | Key Features | Primary Application in Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [3] [21] | Quantum Chemical Dataset | 100M+ calculations, ωB97M-V level, broad coverage (biomolecules, electrolytes, metals) | Training large-scale MLIPs (e.g., UMA, eSEN) for universal chemical space coverage. |

| ByteFF Dataset [41] | Quantum Chemical Dataset | 2.4M optimized geometries, 3.2M torsion profiles (B3LYP-D3(BJ)) for drug-like molecules | Parameterizing specialized, Amber-compatible force fields for drug discovery. |

| DiffTRe [42] | Computational Method | Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting; enables gradient-based optimization vs. experimental data. | Top-down training or fine-tuning of ML potentials to match experimental observables. |

| geomeTRIC [41] | Software Library | Geometry optimization code with internal coordinates and analytical Hessians. | Generating optimized molecular structures and vibrational data for QM datasets. |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

Robust validation is paramount. Beyond comparing QM energies and forces, force fields must be evaluated against experimentally measurable macroscopic properties.

Protocol for Validating Thermodynamic and Transport Properties

This protocol, derived from a study on diisopropyl ether (DIPE), outlines how to assess force field accuracy for liquid-phase simulations [43].

System Preparation:

- Build the System: Create a cubic unit cell containing a large number of molecules (e.g., 3375 DIPE molecules) to minimize finite-size effects for properties like viscosity [43].

- Equilibration: Perform an initial equilibration run in the NpT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble at the target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 bar) to relax the density of the system.

Production Simulation:

- Switch Ensemble: Conduct a production simulation in the NVT (canonical) ensemble, using the average density obtained from the NpT equilibration [43].

- Simulation Length: Ensure the simulation is sufficiently long to achieve convergence for the properties of interest. For viscosity calculations, this typically requires trajectories of tens to hundreds of nanoseconds.

Property Calculation:

- Density: Calculate as the average mass per volume during the NVT production run.

- Shear Viscosity: Compute using the Green-Kubo relation, which relates the viscosity to the time integral of the stress-tensor autocorrelation function sampled during the NVT trajectory [43].

- Other Properties: The same simulation trajectory can be analyzed for other properties like mutual solubility, interfacial tension, and partition coefficients by setting up appropriate system geometries and applying relevant statistical mechanical formulas.

Protocol for Benchmarking Torsional and Conformational Accuracy

This protocol is essential for validating force fields intended for drug discovery, where conformational sampling is critical.

Dataset Curation:

- Select a diverse set of molecules and molecular fragments that represent the chemical space of interest (e.g., drug-like molecules from ChEMBL) [41].

- For each molecule, generate multiple low-energy conformers.

Reference Data Generation:

- Torsion Scans: Perform constrained QM calculations (e.g., at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level) for key dihedral angles, rotating in increments to obtain a torsional energy profile [41].