Benchmarking DFT for Transition Metal Complexes: A Guide to Accurate Calculations in Catalysis and Drug Design

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is indispensable for studying transition metal complexes in catalysis and pharmaceutical development, but achieving accurate results is notoriously challenging.

Benchmarking DFT for Transition Metal Complexes: A Guide to Accurate Calculations in Catalysis and Drug Design

Abstract

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is indispensable for studying transition metal complexes in catalysis and pharmaceutical development, but achieving accurate results is notoriously challenging. This article provides a comprehensive benchmark and practical guide for researchers. It explores the fundamental complexities of 3d metals, evaluates the performance of modern functionals and basis sets for properties like hydricity and spin states, outlines strategies for troubleshooting common optimization issues, and establishes validation protocols against experimental data. By synthesizing recent methodological advances and validation studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to reliably apply DFT for the rational design of transition metal complexes.

Why Transition Metals Challenge DFT: Navigating Spin States and Electronic Complexity

The Computational Conundrum of 3d Electrons and Near-Degeneracy

Transition metal complexes (TMCs) are fundamental to advancements in catalysis, renewable energy, and medicinal chemistry. Their versatile activity stems from a vast chemical space characterized by unique electronic structures, most notably the behavior of 3d electrons [1]. However, this same electronic complexity presents a major challenge for computational chemists. The near-degeneracy of 3d orbitals leads to multiple accessible spin states with very small energy separations, creating a computational conundrum where predicted energies are strongly method-dependent [2] [1]. Accurate prediction of spin-state energetics is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for modeling catalytic reaction mechanisms and computationally discovering new materials [2]. For researchers in drug development, where metalloenzymes and metal-based therapeutics are prevalent, the choice of an inaccurate computational protocol can lead to flawed predictions of reactivity and binding. This guide objectively compares the performance of various quantum chemistry methods, providing a benchmarked framework for selecting the right tool to tackle the challenges posed by 3d electrons.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Credible reference data for TMCs are scarce, making conclusive computational studies difficult. A 2024 benchmark set (SSE17), derived from experimental data of 17 first-row TMCs, provides a rare opportunity for objective comparison [2]. The following tables summarize the performance of different method classes for calculating spin-state energetics.

Table 1: Overall Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods on the SSE17 Benchmark Set [2]

| Method Category | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error (kcal mol⁻¹) | Maximum Error (kcal mol⁻¹) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled-Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 | Highest-accuracy benchmark studies |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 | Accurate spin-state energetics |

| B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 | Accurate spin-state energetics | |

| Hybrid DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 | Not recommended for spin states |

| TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 | General use with caution for spin states | |

| Multireference WFT | CASPT2 | > 1.5 | > -3.5 | Multireference systems |

| MRCI+Q | > 1.5 | > -3.5 | Multireference systems |

Table 2: Performance on Excited-State Properties (UV-vis-nIR Spectra) [3]

| Method | Basis Set | Solvation Model | Application | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD-DFT (ωB97xd) | def2SVP | SMD (Acetone) | Excitation spectra | First 30 excited states, wavelengths, oscillator strengths |

| DFT/CIS (CAM-B3LYP) | def2-TZVPD | Implicit | L-edge XAS spectroscopy | Semiquantitative spectra with modest empirical shifts |

The benchmark data reveals a clear hierarchy. The coupled-cluster method CCSD(T) stands out as a top performer, demonstrating high accuracy with a mean absolute error (MAE) of just 1.5 kcal mol⁻¹, outperforming all tested multireference methods [2]. For practical applications on larger systems, double-hybrid density functionals like PWPB95-D3(BJ) and B2PLYP-D3(BJ) offer the best balance of accuracy and computational cost, achieving MAEs below 3 kcal mol⁻¹. Notably, popular hybrid functionals like B3LYP and TPSSh, often recommended for general use on TMCs, perform significantly worse for spin-state energetics, with MAEs of 5–7 kcal mol⁻¹ and maximum errors exceeding 10 kcal mol⁻¹ [2]. For excited-state properties, the ωB97xd functional is a common choice, as seen in the tmQMg* dataset for modeling UV-vis-nIR spectra [3].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

The SSE17 Benchmarking Protocol

The SSE17 benchmark study established a rigorous protocol for assessing method performance on spin-state energetics [2]:

- Reference Data Curation: The set comprises 17 first-row TMCs (FeII, FeIII, CoII, CoIII, MnII, NiII) with chemically diverse ligands. Reference values for adiabatic or vertical spin-splitting are derived from experimental spin-crossover enthalpies or energies of spin-forbidden absorption bands.

- Data Correction: The raw experimental data is carefully back-corrected for vibrational and environmental effects to provide reliable quantum-chemical reference energies.

- Method Testing: A wide range of methods, including density functional theory (DFT), coupled-cluster, and multireference wave function theory, are evaluated against these reference values. Key metrics are the mean absolute error (MAE) and maximum error, which gauge both average reliability and worst-case performance.

Workflow for Spectroscopic Property Calculation

The computation of core-level spectra, such as L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), requires specialized protocols to account for spin-orbit coupling and electron correlation.

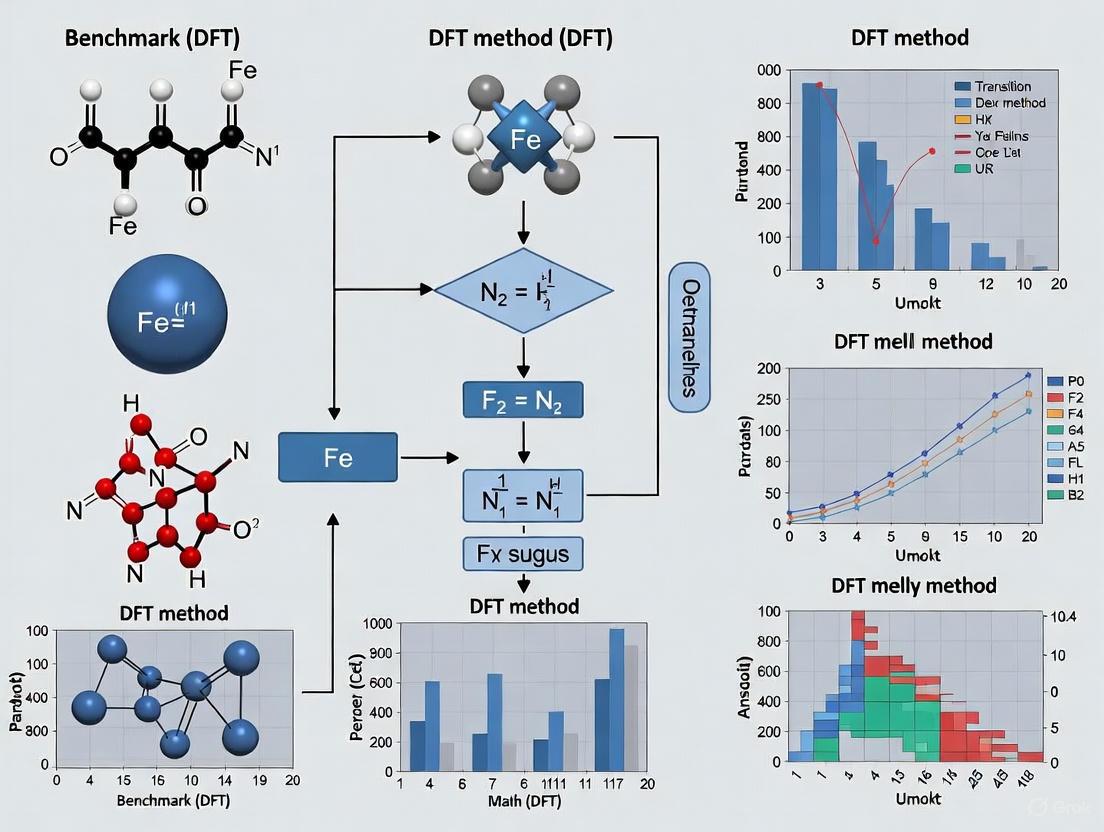

Diagram: Workflow for Simulating L-Edge XAS Spectra

For example, the DFT/CIS method tackles the challenge of simulating L-edge spectra by combining a spin–orbit mean-field description with nonrelativistic excited states computed using a semi-empirical density-functional theory configuration-interaction singles approach [4]. This method incorporates a semi-empirical correction (Δεi) to core orbital energies to reduce the self-interaction error that typically plagues traditional TD-DFT calculations, which often require ad hoc shifts of ~20 eV to match experimental L-edge spectra [4].

Navigating the computational landscape for TMCs requires a suite of reliable methods, datasets, and tools. The table below details key resources for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Computational TMC Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSE17 Benchmark Set [2] | Dataset | Method validation | 17 TMCs with experimental spin-state energetics |

| OMol25 Dataset [5] | Dataset | ML training/baselining | 83M systems, ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level, includes TMCs |

| tmQMg* Dataset [3] | Dataset | Photochemistry ML | Excited states for 74k TMCs at TD-ωB97xd/def2SVP level |

| CCSD(T) [2] | Method | High-accuracy benchmarking | "Gold standard"; MAE of 1.5 kcal mol⁻¹ on SSE17 |

| Double-Hybrid DFT (e.g., PWPB95) [2] | Method | Accurate spin-state calculations | Best-performing DFT class for spin-state energetics |

| DFT/CIS Method [4] | Method | Core-level spectroscopy | Computes L-edge spectra with reduced empirical shifting |

| molSimplify [1] | Software | Automated TMC construction | Rapid building and screening of TMC geometries |

The computational conundrum of 3d electrons and near-degeneracy demands a careful, evidence-based approach to method selection. Benchmark studies clearly show that while popular hybrid functionals like B3LYP are convenient, they introduce significant errors in predicting the spin-state energetics that govern the reactivity of transition metal complexes. For ground-state properties, CCSD(T) remains the benchmark for accuracy, with double-hybrid DFT functionals representing the most accurate practical choice for DFT. For spectroscopic properties, methods like DFT/CIS and range-separated hybrids like ωB97xd offer improved performance for modeling challenging spectroscopies like L-edge XAS and UV-vis-nIR excitations.

The field is moving toward larger, more diverse benchmark sets and the integration of machine learning with quantum chemistry to traverse the vast design space of TMCs [1] [5] [3]. The development of robust, multi-level protocols that leverage the strengths of high-accuracy wavefunction methods for calibration and efficient DFT or machine learning potentials for exploration is key to future progress. For researchers in drug development and materials science, adhering to these benchmarked best practices is essential for generating reliable, predictive computational models of transition metal complex chemistry.

Accurately Predicting Hydricity, Redox Potentials, and Spin-State Ordering

Computational chemistry provides indispensable tools for studying transition metal complexes, which are pivotal in catalysis, bioinorganic chemistry, and materials science. The rational design of these complexes relies on the accurate prediction of key electronic properties. However, transition metals present unique challenges for quantum chemical methods due to their complex electronic structures, with closely spaced energy levels and significant electron correlation effects. This guide objectively benchmarks the performance of various density functional theory (DFT) methods and advanced wave function theories against experimental data for three critical properties: hydricity, redox potentials, and spin-state energetics. The findings provide actionable recommendations for researchers, enabling informed methodological selections for specific target properties.

Performance Comparison of Quantum Chemical Methods

Hydricity Prediction

Hydricity, defined as the heterolytic bond dissociation energy of a metal hydride to a metal cation and hydride (MH ⇌ M⁺ + H⁻), is a critical thermodynamic parameter in hydrogenation and energy-related catalysis. The performance of various DFT methodologies for predicting this property has been systematically evaluated.

Table 1: Benchmarking DFT Methods for Hydricity Prediction

| Computational Protocol | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) | Key Findings | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP (Geometry) + PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP (Single-point) [6] | 1.4 kcal/mol | Excellent agreement with experimental hydricity values for three first-row TM hydride complexes [6]. | High-accuracy hydricity calculation for 3d transition metal complexes. |

| B3PW91 with various basis sets [6] | Not specified | Historically used based on performance in earlier studies on 3d, 4d, and 5d metal complexes [6]. | General transition metal chemistry (historical context). |

| M06 with various basis sets [6] | Not specified | Selected by some groups as computed barrier heights were closest to the average value across multiple functionals [6]. | Balanced treatment for multi-step transformations. |

Experimental Protocol for Hydricity Benchmarking: The benchmark is constructed from experimentally determined metal-hydride bond strengths. Geometry optimizations are typically performed at the GGA level (e.g., RI-BP86-D3) with a moderate basis set (e.g., def2-SVP), incorporating empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., Grimme's D3) and an implicit solvation model (e.g., IEF-PCM). The final energies are then obtained from single-point calculations on the optimized geometries using a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0) and a larger triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP). The nature of the located minima is confirmed via harmonic frequency calculations [6].

Spin-State Energetics Prediction

The accurate description of spin-state energetics is one of the most significant challenges in transition metal computational chemistry, with major implications for understanding reactivity and magnetic properties. Recent large-scale benchmarking has provided clear guidance.

Table 2: Benchmarking Quantum Chemistry Methods for Spin-State Energetics (SSE17 Benchmark Set)

| Method Class | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Maximum Error | Performance Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave Function Theory | CCSD(T) [7] [8] | 1.5 kcal/mol | -3.5 kcal/mol | Gold standard; highest accuracy [7] [8]. |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ), B2PLYP-D3(BJ) [7] [8] | < 3.0 kcal/mol | < 6.0 kcal/mol | Best-performing DFT class; recommended for production calculations [7] [8]. |

| Meta-GGA/Hybrid DFT | M06-L, MN15-L, r2SCANh [9] | ~10-15 kcal/mol (on Por21) | Not specified | Top-performing local/hybrid functionals for complex systems like porphyrins [9]. |

| Commonly Used DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ), TPSSh-D3(BJ) [7] [8] | 5–7 kcal/mol | > 10 kcal/mol | Suboptimal performance; use with caution for spin states [7] [8]. |

Experimental Protocol for Spin-State Benchmarking (SSE17): The SSE17 benchmark set derives reference values from two types of experimental data for 17 first-row transition metal complexes (Fe(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Co(III), Mn(II), Ni(II)) [7] [8]:

- Spin-Crossover Enthalpies: For 9 complexes, adiabatic energy differences are derived from experimental spin-crossover enthalpies.

- Spin-Forbidden d-d Transitions: For 8 complexes, vertical energy differences are derived from energies of spin-forbidden absorption bands in reflectance spectra. These experimental data are carefully back-corrected for vibrational and environmental effects (e.g., solvation, crystal lattice) to provide electronic energy differences directly comparable with quantum chemistry computations [7] [8].

Redox Potential Prediction

Redox potentials are critical for understanding electron transfer processes in catalytic cycles and biological systems. Predicting them accurately requires a sophisticated treatment of both electronic structure and solvation effects.

Table 3: Performance of Computational Approaches for Redox Properties

| Methodological Aspect | Key Finding | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Method | DLPNO-CCSD(T) provides high-accuracy reference energies [10]. | Achievable accuracy for redox potentials is ~0.13 V on average with a robust protocol [10]. |

| Explicit Solvation Shell | Including a second solvation sphere explicitly is essential, even when using continuum models [10]. | Neglecting the second shell introduces significant error; explicit treatment drastically improves accuracy [10]. |

| Solvation Model | CPCM implemented at the DLPNO-CC level can be used self-consistently [10]. | Allows for computation of standard redox potentials directly at the coupled cluster level [10]. |

| Multilayer Approaches | DLPNO-CCSD(T) for the first sphere with a lower-level method for the second sphere is a promising strategy [10]. | Enables cost-effective treatment of larger, more realistic solvation models [10]. |

Computational Protocol for Redox Potential Calculation: A reliable protocol involves building a cluster model that includes the metal ion and at least two explicit hydration shells (e.g., [M(H₂O)₁₈]ⁿ⁺). The electronic energy change for the redox process is computed at a high level of theory, such as DLPNO-CCSD(T), with careful attention to convergence settings. This energy is then combined with the solvation free energy change, computed using a continuum model like CPCM applied self-consistently at the coupled cluster level. The inclusion of the second explicit solvation shell is non-negotiable for accuracy, as continuum models alone cannot capture the specific hydrogen-bonding interactions that change between oxidation states [10].

Visualizing Computational Workflows

Workflow for Property Prediction

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for accurate prediction of transition metal complex properties, showing the sequence from system definition through geometry optimization, frequency validation, high-level energy calculation, and final property computation.

Solvation Model Strategy

Figure 2: Hybrid solvation model strategy for transition metal complexes, combining essential explicit solvent molecules for specific interactions (particularly for redox potential calculations) with a continuum model representing the bulk solvent environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Transition Metal Complex Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| SSE17 Benchmark Set [7] [8] | A curated set of experimental spin-state energetics for 17 transition metal complexes. | Method validation and benchmarking for spin-state ordering predictions. |

| Double-Hybrid Density Functionals [7] [8] | DFT functionals incorporating a second-order perturbation theory correction. | High-accuracy production calculations for spin-state energetics (e.g., PWPB95-D3(BJ)). |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) Method [10] | A highly accurate, computationally efficient coupled cluster approach. | Generating benchmark-quality energies for redox processes and spin-states. |

| Def2 Basis Set Family [6] | Systematically defined Gaussian-type basis sets for quantum chemistry. | Balanced accuracy/efficiency for geometry (def2-SVP) and energy (def2-TZVP) calculations. |

| Grimme's D3 Dispersion Correction [6] | An empirical correction for London dispersion interactions. | Improving geometric and energetic accuracy, especially for non-covalent interactions. |

| Continuum Solvation Models (PCM/CPCM/SMD) [6] [10] | Implicit models for describing solvation effects. | Accounting for bulk solvent effects in energy and property calculations. |

| Catalytic Hydricity Data [6] | Experimentally determined metal-hydride bond strengths. | Benchmarking and validating computational protocols for hydricity prediction. |

This comparison guide demonstrates that the accurate prediction of key properties for transition metal complexes is highly method-dependent. For hydricity, the two-step protocol of RI-BP86-D3/def2-SVP geometry optimization followed by PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP single-point calculations is recommended. For spin-state energetics, the double-hybrid functionals PWPB95-D3(BJ) and B2PLYP-D3(BJ) emerge as the best DFT-based options, while CCSD(T) remains the gold standard for the highest accuracy. For redox potentials, a combination of DLPNO-CCSD(T) electronic energies with a solvation model that includes an explicit second shell is crucial. By selecting methods benchmarked for the specific property of interest, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their computational studies on transition metal systems.

In the computational modeling of transition metal complexes (TMCs), density functional theory (DFT) serves as a cornerstone for predicting structure, reactivity, and electronic properties. However, the predictive power of any computational method is only as reliable as the experimental data against which it is validated. For TMCs—characterized by complex electronic structures, diverse spin states, and significant electron correlation effects—the choice of density functional approximation (DFA) profoundly influences computed energetics, spin-state ordering, and reaction barriers. Without rigorous benchmarking against high-quality experimental data, computational predictions can be misleading, potentially derailing experimental efforts in catalysis and drug development. This guide objectively compares the performance of various quantum chemistry methods, highlighting the critical importance of robust experimental validation data sets in guiding functional selection for TMC research.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking of Computational Methods

Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods on Key Benchmark Sets

Table 1: Performance of DFT and Wave Function Methods on the SSE17 Benchmark Set for Spin-State Energetics (Mean Absolute Error, kcal mol⁻¹)

| Method Class | Specific Method | MAE (kcal mol⁻¹) | Max Error (kcal mol⁻¹) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 | Includes perturbative doubles excitation; often requires larger basis sets [2] |

| B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 | ||

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 | Considered a "gold standard"; high computational cost [2] |

| Multireference WFT | CASPT2 / MRCI+Q | > 1.5 | > -3.5 | Can be accurate but performance varies; no consistent improvement over CCSD(T) [2] |

| Popular Hybrid DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 | Previously recommended for spin states; performance less robust on stringent benchmarks [2] |

| TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 |

Table 2: Functional Performance on the MME55 Metalloenzyme Model Set and Broader Databases

| Functional | Class | Performance on MME55 | Performance on GSCDB137 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOS0-PBE0-2-D3(BJ) | Double-Hybrid | Most Accurate | High Accuracy | Excellent for enzymatic energetics [11] |

| revDOD-PBEP86-D4 | Double-Hybrid | Most Accurate | High Accuracy | Excellent for enzymatic energetics [11] |

| ωB97M-V | Range-Separated Hybrid | Strong Performer | Most Balanced Hybrid Meta-GGA | Reliable compromise of accuracy and efficiency [11] [12] |

| ωB97X-V | Range-Separated Hybrid | Strong Performer | Most Balanced Hybrid GGA | Reliable compromise of accuracy and efficiency [11] [12] |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Not a Strong Performer | Not Top Tier | Popular but discouraged for enzyme energetics; sensitive to spin-state errors [11] |

| B97M-V | Meta-GGA | N/A | Leads Meta-GGA class | Top non-hybrid functional on broad tests [12] |

| revPBE-D4 | GGA | N/A | Leads GGA class | Top GGA on broad tests [12] |

Machine Learning vs. Traditional Quantum Chemistry

Table 3: Comparison of Machine Learning and Traditional Quantum Methods for Charge-Related Properties

| Method | Type | MAE on Main-Group Redox (V) | MAE on Organometallic Redox (V) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c | DFT Functional | 0.260 | 0.414 | More accurate for main-group species [13] |

| GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical | 0.303 | 0.733 | Poor performance on organometallics [13] |

| UMA-S (OMol25) | Neural Network Potential | 0.261 | 0.262 | Balanced accuracy; outperforms DFT on organometallics [13] |

| eSEN-S (OMol25) | Neural Network Potential | 0.505 | 0.312 | Excellent for organometallics; weaker on main-group [13] |

| ANN (Kulik Group) | Neural Network | ~3 kcal/mol (Spin-State Splitting) | N/A | Predicts spin-state splitting vs. HF exchange; uses tailored descriptors [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The SSE17 Benchmark Set: From Experimental Data to Reference Energetics

The SSE17 benchmark set provides adiabatic or vertical spin-state splittings for 17 first-row TMCs (Fe, Co, Mn, Ni) derived from experimental data [2].

- Data Sourcing: Reference energies are obtained from two primary experimental sources:

- Spin Crossover Enthalpies: Measured from variable-temperature studies of spin crossover phenomena.

- Spin-Forbidden Absorption Bands: Energies derived from electronic spectroscopy.

- Vibrational/Environmental Correction: The raw experimental data are carefully back-corrected to isolate the electronic contribution to the energy difference, removing vibrational and solvent/environmental effects. This yields a set of electronic spin-state splitting energies suitable for benchmarking gas-phase quantum chemistry calculations.

- Methodology Benchmarking: High-level wave function methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) and a range of DFAs are tested against these reference values. The performance is assessed using statistical metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and maximum error [2].

The MME55 set focuses on reaction energies and barrier heights for models of metalloenzyme active sites [11].

- System Selection: The set contains 55 data points across 10 different enzymes, incorporating eight different transition metals, both open- and closed-shell systems, with model sizes up to 116 atoms.

- Reference Calculations:

- Geometry Optimization: All structures are optimized at the PBEh-3c level of theory, which includes dispersion and basis set superposition error corrections.

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: Reference energies are computed using DLPNO–CCSD(T) (Domain-based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster with Singles, Doubles, and Perturbative Triples).

- Basis Set Extrapolation: Calculations are performed with triple- and quadruple-zeta basis sets (def2-TZVPP and def2-QZVPP) and extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) limit to ensure high accuracy [11].

- Functional Testing: A wide range of DFAs are evaluated against these "gold-standard" DLPNO–CCSD(T)/CBS references.

Workflow for Creating and Using a Benchmark Set

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for developing a benchmark set and using it to validate computational methods, as exemplified by SSE17 and MME55.

Table 4: Key Benchmarking Resources and Computational Tools

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to TMC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSE17 | Benchmark Data Set | Provides experimental spin-state energetics for 17 TMCs. | Validates method accuracy for spin splitting, critical for catalysis [2]. |

| MME55 | Benchmark Data Set | Provides CCSD(T)-level reaction energies/barriers for metalloenzyme models. | Tests functional performance on biologically relevant TMC reactions [11]. |

| GSCDB137 | Benchmark Database | Curated database of 137 sets covering diverse chemistry, including TMCs. | Offers a comprehensive platform for stringent DFA validation [12]. |

| DLPNO–CCSD(T) | Quantum Chemistry Method | Provides near-chemical accuracy for large systems with lower cost. | Generates reliable reference energies for benchmark sets like MME55 [11]. |

| ωB97M-V / ωB97X-V | Density Functional | Robust, range-separated hybrid functionals. | Recommended as a reliable compromise between accuracy and computational cost [11] [12]. |

| Double-Hybrid Functionals | Density Functional | Include a perturbative correlation correction. | Top performers for accurate spin-state and reaction energetics [11] [2]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine Learning Model | Learns from QM data to predict energies/properties rapidly. | Can achieve DFT-level accuracy for specific properties like redox potentials [13]. |

Rigorous benchmarking against high-quality experimental and theoretical reference data is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for reliable computational research on transition metal complexes. Benchmark sets like SSE17 and MME55 reveal that functional performance is highly variable, with double-hybrid and carefully selected range-separated hybrid functionals (e.g., ωB97M-V) generally providing superior accuracy for spin-state and reaction energetics. In contrast, popular historical choices like B3LYP often show significant errors. The emergence of machine-learned potentials offers a promising path for rapid screening, but their performance is intrinsically tied to the quality of the underlying quantum mechanical data on which they are trained. As the field advances, the continued development and use of curated, chemically diverse benchmark sets will be critical for validating new methods, guiding functional selection, and ensuring that computational predictions accurately guide experimental discovery in catalysis and drug development.

Choosing Your Tools: A Benchmark of DFT Functionals, Basis Sets, and Solvation Models

The accurate prediction of electronic properties and energetics in transition metal complexes represents a compelling challenge in computational chemistry, with profound implications for catalysis, molecular magnetism, and materials design. Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the predominant quantum chemical method for such investigations, primarily due to its favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy. The framework of "Jacob's Ladder" classifies DFT functionals in ascending order of sophistication and expected accuracy: from the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) on the first rung, to meta-GGAs, hybrid GGAs, and finally, double-hybrid functionals at the highest rung. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of GGA, hybrid, and double-hybrid functionals for key properties of transition metal complexes, drawing upon recent benchmark studies and experimental data. The analysis is framed within the broader context of developing reliable computational protocols for transition metal research in inorganic chemistry and drug development.

Theoretical Background and Methodology

The Rungs of Jacob's Ladder

Jacob's Ladder organizes density functionals based on the ingredients used in the exchange-correlation functional:

- GGA (First Rung): Utilizes the electron density and its gradient (e.g., PBE, BP86). It offers good computational efficiency but is prone to systematic errors, such as the self-interaction error.

- Meta-GGA (Second Rung): Incorporates the kinetic energy density in addition to the GGA ingredients (e.g., SCAN, TPSS). This improves the description of inhomogeneous electron systems.

- Hybrid GGA (Third Rung): Mixes a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with GGA exchange (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0). This admixture helps correct for the self-interaction error.

- Double-Hybrid (Fourth Rung): Incorporates both exact exchange and a perturbative correlation contribution (e.g., B2-PLYP, DSD-BLYP). The general form of the exchange-correlation energy in a double-hybrid functional is given by:

E_XC^DH = (1 - α_X) E_X^DFA + α_X E_X^HF + (1 - α_C) E_C^DFA + α_C E_C^PT2whereE_X^DFAandE_C^DFAare the semilocal exchange and correlation energies from a lower-rung functional,E_X^HFis the Hartree-Fock exchange energy, andE_C^PT2is the correlation energy from second-order perturbation theory (PT2) [15] [16].

Benchmarking Strategy and Experimental Data

Credible benchmarking requires comparison against reliable reference data. Recent studies have made significant strides by deriving benchmarks from experimental sources. For instance, the SSE17 benchmark set provides spin-state energetics for 17 first-row transition metal complexes, derived from experimental spin crossover enthalpies or energies of spin-forbidden absorption bands, back-corrected for vibrational and environmental effects [2]. Furthermore, the GSCDB138 database offers a gold-standard compilation of 138 datasets, including transition-metal reaction energies and barrier heights, with reference values from high-level coupled-cluster theory [17]. These robust datasets allow for a conclusive assessment of functional performance.

Performance Comparison of Density Functionals

Spin-State Energetics

The accurate prediction of spin-state energy splittings is crucial for modeling catalytic mechanisms involving transition metals. The performance of various functional types for this property is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Performance of DFT Functionals for Spin-State Energetics (SSE17 Benchmark)

| Functional Type | Example Functional(s) | Mean Absolute Error (kcal mol⁻¹) | Maximum Error (kcal mol⁻¹) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrid | PWPB95-D3(BJ), B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 | Most accurate class for spin-state energetics [2]. |

| Hybrid | B3LYP*-D3(BJ), TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 | Performance is much worse than double-hybrids [2]. |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN | Varies | - | Can outperform some hybrids but is less systematic than double-hybrids [17]. |

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 | Outperforms all tested multireference and DFT methods [2]. |

As evidenced by the SSE17 benchmark, double-hybrid functionals significantly outperform the hybrid functionals traditionally recommended for spin-state energetics. The best-performing hybrids, such as B3LYP* and TPSSh, exhibit mean absolute errors nearly double that of leading double-hybrids, with maximum deviations exceeding 10 kcal mol⁻¹, which is chemically significant [2].

Magnetic Exchange Coupling Constants

The magnetic exchange coupling constant (J) quantifies the interaction between unpaired electrons in different metal centers. Table 2 compares functional performance for this property.

Table 2: Performance of DFT Functionals for Magnetic Exchange Coupling

| Functional Type | Example Functional(s) | Performance for J-Coupling | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range-Separated Hybrid | Scuseria functionals (moderate HFX) | Good | Perform better than functionals with high Hartree-Fock exchange in the long-range [18]. |

| Hybrid meta-GGA | TPSSh | Good | Surpasses double-hybrids for Mn dinuclear complexes; a robust choice [15]. |

| Double-Hybrid | B2-PLYP, reparametrized DHDFs | Variable / Poor | More uniform but fail to deliver improved accuracy or reliability for Mn complexes [15]. |

| Hybrid GGA | B3LYP | Moderate | Often used, but TPSSh generally performs better for manganese systems [15]. |

| GGA | PBE, BP86 | Poor | Tend to over-stabilize delocalized states, yielding too large antiferromagnetic couplings [15]. |

For magnetic coupling in manganese complexes, the hybrid-meta-GGA TPSSh (with 10% HF exchange) has been identified as a top performer, surpassing even double-hybrid functionals [15]. This demonstrates that the "highest rung" is not universally superior; the optimal functional depends strongly on the specific chemical property and system.

Electronic Properties and Thermochemistry

The accuracy of functionals extends to other key properties, such as band gaps, reaction energies, and non-covalent interactions.

Table 3: Performance for Other Key Properties

| Property | Best Performing Functional Types | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Band Gaps (e.g., MoS₂) | Hybrid (HSE06) | HSE06 significantly improves band gap prediction over GGA (PBE), which severely underestimates it [19] [20]. |

| Formation Energies | Hybrid (HSE06) | HSE06 provides lower and generally more accurate formation energies compared to GGA (PBEsol) [19]. |

| General Thermochemistry & Kinetics | Double-Hybrids (DSD variants), Balanced Hybrids (ωB97M-V, ωB97X-V) | Double-hybrids lower mean errors by ~25% vs. the best hybrids. B97M-V and revPBE-D4 lead the meta-GGA and GGA classes, respectively [17]. |

| Non-Covalent Interactions | Double-Hybrids with Dispersion Correction | Empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., D3, D4) are critical for accuracy [16]. |

| Hydricity of TM Hydrides | Hybrid (PBE0-D3) | PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP//RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP yields a mean absolute deviation of 1.4 kcal/mol from experiment [6]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General Benchmarking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a standardized protocol for benchmarking density functionals, as employed in recent high-quality studies.

Protocol for Spin-State Energetics (SSE17)

A specific protocol for benchmarking spin-state energetics, as derived from the SSE17 study, is detailed below [2].

- Reference Data Curation: Compile experimental data from spin crossover enthalpies or spin-forbidden absorption bands. Critically, these data must be back-corrected for vibrational and environmental effects to derive electronic spin-state splittings (

ΔE) as reference values. - Computational Model: For each complex in the benchmark set, compute the electronic energies for the relevant spin states (e.g., high-spin and low-spin).

- Methodology:

- Wave Function Reference: Employ the coupled-cluster CCSD(T) method as a high-accuracy reference standard.

- DFT Calculations: Perform single-point energy calculations on consistent molecular geometries using a range of functionals from GGA to double-hybrids. Dispersion corrections (e.g., D3(BJ)) and solvation models (e.g., PCM) should be applied consistently.

- Error Analysis: Calculate the difference between the computed adiabatic spin-state energy difference and the reference value for each complex. Compute aggregate statistics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and maximum error across the entire set.

Protocol for Magnetic Exchange Coupling

The Broken-Symmetry DFT (BS-DFT) approach is the standard method for calculating the magnetic exchange coupling constant (J) [15].

- System Preparation: Construct model structures from crystallographic data for dinuclear (or polynuclear) transition metal complexes.

- Energy Calculations:

- Calculate the energy of the high-spin (HS) state (

E_HS), typically a spin-polarized calculation. - Calculate the energy of the broken-symmetry (BS) state (

E_BS), which is a single-determinantal approximation to the low-spin state.

- Calculate the energy of the high-spin (HS) state (

- Spin-Projection: Use the Yamaguchi relation or similar spin-projection techniques to estimate the J-value from the calculated energies. For a dinuclear system with metal spins S_A and S_B, the Yamaguchi formula is:

J = (E_BS - E_HS) / [2 S_A S_B + (S_A + S_B)]. - Validation: Compare the computed J-values against experimentally determined coupling constants from magnetic susceptibility measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential computational reagents and resources used in the featured studies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DFT Benchmarking

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSE17 Benchmark Set [2] | Experimental Dataset | Provides gold-standard reference data for spin-state energetics of 17 first-row TM complexes. | Benchmarking functional performance for catalytic and (bio)inorganic systems. |

| GSCDB138 Database [17] | Composite Benchmark Library | Offers a comprehensive set of 8383 gold-standard data points for validating functionals across diverse properties. | Stringent validation of new or existing density functionals. |

| FHI-aims [19] | Software Package | An all-electron, NAO-based code for high-throughput DFT calculations, enabling hybrid functional studies on thousands of materials. | Generating reliable reference data for materials databases. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [20] | Software Package | A plane-wave, pseudopotential-based suite for electronic structure calculations and materials modeling. | Simulating periodic systems like solids and surfaces (e.g., MoS₂). |

| HSE06 Functional [19] [20] | Hybrid Functional | A range-separated hybrid functional that mixes HF exchange with GGA exchange, improving electronic property predictions. | Calculating accurate band gaps and formation energies for solids. |

| D3/D4 Dispersion Correction [17] [6] | Empirical Correction | Accounts for long-range dispersion interactions not captured by standard semilocal functionals. | Essential for accurate thermochemistry, especially non-covalent interactions. |

| def2 Basis Sets [6] | Gaussian Basis Sets | A systematically convergent family of basis sets for accurate molecular calculations across the periodic table. | Standard choice for molecular quantum chemistry with DFT and wave function methods. |

The performance of density functionals is highly property-dependent, reinforcing the need for systematic benchmarking. The following decision diagram synthesizes the findings to guide functional selection for transition metal complexes.

In conclusion, while double-hybrid functionals generally set the benchmark for main-group and some transition-metal thermochemistry (like spin-state energetics), they are not a panacea. For specific properties like magnetic coupling in manganese complexes, lower-rung hybrids like TPSSh can be superior. For solid-state properties, hybrids like HSE06 are indispensable. Therefore, the selection of a functional must be guided by the specific chemical problem, the property of interest, and the available benchmark data for that particular domain.

Within transition metal chemistry, the hydricity of a metal complex—defined as the Gibbs free energy change for the heterolytic cleavage of a metal-hydride bond to yield a proton and a hydride anion ((MH \rightleftharpoons M^+ + H^-))—is a crucial thermodynamic property for understanding and designing catalysts, particularly for hydrogenation and energy conversion reactions [21]. The accurate prediction of hydricity using Density Functional Theory (DFT) is notoriously challenging due to the complex electronic structures of 3d transition metals, which can exhibit multi-reference character and strong correlation effects [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of the recommended methodology, RI-BP86-D3 for geometry optimization combined with PBE0-D3 for single-point energy calculations, against other common DFT functionals, providing benchmarking data and detailed protocols for researchers in drug development and catalytic materials science.

Recommended Methodology: A Dual-Level Approach

Extensive benchmarking against experimental hydricity values has identified a specific dual-level approach that provides an optimal balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for 3d transition metal complexes [21].

- Geometry Optimization: The RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP level of theory is recommended. This method utilizes the BP86 generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional, combined with Grimme's D3 empirical dispersion correction and the Resolution of Identity (RI) approximation for accelerated computation. Geometries are optimized within a Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) to simulate the solvation environment (e.g., acetonitrile). The def2-SVP basis set provides a balanced description of the metal and ligand atoms at this stage [21].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: On the optimized geometries, a more accurate single-point energy calculation is performed using the PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP level. This employs the hybrid PBE0 functional, which incorporates a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, again with D3 dispersion correction and PCM solvation. The larger def2-TZVP basis set provides a more complete description of the electron correlation energy critical for accurate thermodynamic predictions [21].

This protocol was benchmarked against experimentally determined metal-hydride bond strengths for first-row transition metal hydride complexes, achieving a mean absolute deviation (MAD) of 1.4 kcal/mol from experimental values, a notably high accuracy for such systems [21].

Performance Comparison of DFT Functionals for Hydricity and Related Properties

The performance of various density functionals was evaluated quantitatively against high-level theoretical or experimental reference data. The following tables summarize key benchmarking results for hydricity and other critical reaction energies involving transition metals.

Table 1: Benchmarking DFT Functionals for Transition Metal Complex Properties

| Functional | Class | Test Property | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI-BP86-D3 (geom) / PBE0-D3 (energy) | Hybrid GGA (Dual-Level) | Hydricity of 3d TM Complexes | 1.4 kcal/mol | Experimental [21] |

| PBE0-D3 | Hybrid GGA | Activation Energies (Pd/Ni catalysts) | 1.1 kcal/mol | CCSD(T)/CBS [22] |

| B3LYP-D3 | Hybrid GGA | Activation Energies (Pd/Ni catalysts) | 1.9 kcal/mol | CCSD(T)/CBS [22] |

| PW6B95-D3 | Hybrid GGA | Activation Energies (Pd/Ni catalysts) | 1.9 kcal/mol | CCSD(T)/CBS [22] |

| M06-2X | Hybrid meta-GGA | Activation Energies (Pd/Ni catalysts) | 6.3 kcal/mol | CCSD(T)/CBS [22] |

| B3LYP (no dispersion) | Hybrid GGA | General Main-Group Thermochemistry (GMTKN55) | Not Recommended | High-Level Ab Initio [23] |

Table 2: General Recommended DFT Functionals from Broad Benchmarking (GMTKN55 Database)

| Functional | Class | Primary Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ), DSD-PBEP86-D3(BJ) | Double-Hybrid | Most reliable for thermochemistry and noncovalent interactions [23] |

| ωB97X-V, M052X-D3(0), ωB97X-D | Hybrid | Best hybrid functionals [23] |

| PW6B95-D3(BJ) | Hybrid | Best conventional global hybrid; robust with few technical issues [23] |

| SCAN-D3(BJ) | meta-GGA | Recommended at the meta-GGA level [23] |

| revPBE-D3(BJ), B97-D3(BJ) | GGA | Competitive with and often superior to many meta-GGAs [23] |

The data reveals several key insights:

- PBE0-D3 consistently demonstrates high accuracy. Its top performance for both activation barriers of catalytic bond activations [22] and its selection in the dual-level hydricity protocol [21] underscores its robustness for transition metal chemistry.

- Dispersion corrections are non-negotiable. The inclusion of Grimme's D3 correction is critical for achieving quantitative accuracy across multiple properties and functional classes [23].

- Popular methods like standard B3LYP are not recommended. The widespread B3LYP functional, especially without dispersion corrections, shows poor performance for reaction energies and is not advised for benchmarking studies [23]. Its performance is significantly improved with the -D3 correction [22].

- Double-hybrid functionals offer the highest accuracy but at a greatly increased computational cost, making them less practical for large systems or high-throughput screening [23].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Detailed Protocol for Hydricity Calculation

The following workflow outlines the steps for calculating hydricity using the recommended dual-level method.

Diagram 1: Hydricity calculation workflow.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Initial Geometry: Use X-ray crystal structures of closely related systems or construct a reasonable model as a starting point for optimization [21].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular structure of the metal hydride and its conjugate acid using the RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP level. The RI (Resolution of Identity) approximation speeds up the calculation. The implicit solvation model (PCM with parameters for acetonitrile, ε = 35.688) is essential [21].

- Frequency Analysis: Perform a frequency calculation at the same level of theory as the optimization on the optimized structure. This serves two purposes:

- Verify Minima: Confirm that the structure is a true minimum on the potential energy surface by ensuring the absence of imaginary frequencies.

- Obtain Thermodynamic Corrections: Extract the zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) and thermal corrections to enthalpy and Gibbs free energy at the specified temperature and pressure (e.g., 298.15 K and 468 atm to mimic bulk acetonitrile) [21].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Perform a more accurate single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry using the PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP level. An ultrafine integration grid (e.g., 99 radial shells with 590 angular points) is recommended for numerical stability [21].

- Compute Hydricity: The thermodynamic hydricity (( \Delta G^{\circ}_{H^{-}} )) is calculated indirectly via a thermochemical cycle to avoid direct computation of charged species [21]:

- Calculate the free energy change for the protonation reaction: ( MH + H^+ \rightleftharpoons M^+ + H2 ) (( \Delta G^{\circ}{1} )) using the single-point energies and thermodynamic corrections.

- Combine this with the experimental free energy for the heterolysis of ( H2 ): ( H2 \rightleftharpoons H^+ + H^{-} ) (( \Delta G^{\circ}{H{2}} = 76.0 \text{ kcal/mol} )).

- The hydricity is then: ( \Delta G^{\circ}{H^{-}} = \Delta G^{\circ}{1} - \Delta G^{\circ}{H{2}} ).

Key Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DFT Benchmarking

| Item / Method | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PBE0 Functional | Hybrid GGA functional with 25% HF exchange; balances accuracy and cost. | Accurate single-point energies for transition metal complexes [22] [21]. |

| BP86 Functional | GGA functional; efficient for geometry optimizations. | Generating reliable initial structures for higher-level energy calculation [21]. |

| D3 Dispersion Correction | Empirical correction for London dispersion interactions. | Essential for accurate reaction energies and noncovalent interactions [23]. |

| def2-SVP / def2-TZVP | Ahlrichs-type Gaussian-type orbital basis sets. | Balanced (SVP) and high-accuracy (TZVP) descriptions of electron density [21]. |

| PCM Solvation Model | Implicit solvation model to simulate solvent effects. | Modeling reactions in solution (e.g., acetonitrile) [21]. |

| Resolution of Identity (RI) | Approximation to accelerate computation of two-electron integrals. | Speeding up calculations with pure GGA functionals like BP86 [21]. |

Benchmarking studies consistently show that no single density functional is universally superior, but carefully validated protocols can deliver chemical accuracy. The dual-level approach of RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP for geometries and PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP for energies has been experimentally validated for predicting the hydricity of 3d transition metal complexes with a high degree of accuracy (MAD = 1.4 kcal/mol) [21]. This methodology, along with other top-performing hybrid functionals like PW6B95-D3, provides a reliable foundation for computational investigations in transition metal chemistry and catalyst design. Researchers are advised to always use dispersion corrections and to be cautious of the known limitations of popular but less accurate methods like B3LYP for quantitative thermodynamic predictions [22] [23].

The accurate prediction of spin-state energetics in transition metal complexes (TMCs) represents one of the most compelling challenges in computational quantum chemistry. This capability is fundamental to modeling catalytic reaction mechanisms in industrial processes and drug development, and for the computational discovery of new materials [1]. Among TMCs, iron porphyrins are of particular importance due to their ubiquitous presence in biological systems—serving as the active sites in hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome P450 enzymes—and their broad applicability as biomimetic catalysts [9]. The presence of the iron metal center makes these systems exceptionally challenging for electronic structure calculations due to several low-lying, nearly degenerate spin states [9].

Density functional theory (DFT) has emerged as the most widely used computational tool for studying these systems, offering a reasonable balance between computational cost and accuracy [1]. However, the reliability of DFT predictions is severely dependent on the choice of the exchange-correlation functional approximation [9]. Standard functionals can produce dramatically different results for spin-state energy splittings, leading to incorrect ground-state predictions and unreliable mechanistic conclusions. This review, situated within the broader context of benchmarking DFT methods for transition metal complexes, demonstrates through comprehensive experimental and theoretical benchmarks that double-hybrid density functionals consistently outperform other classes of DFT approximations for predicting spin-state energetics in iron porphyrins and related TMCs.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

The SSCIP6 Benchmark for Crystalline Iron Porphyrins

A recent high-level assessment of DFT methods focused on predicting spin states for six Fe(III) or Fe(II) porphyrin complexes experimentally characterized in the solid state [24]. This study created the SSCIP6 benchmark set (Spin States for Crystalline Iron Porphyrins) by quantifying the effects of porphyrin side substituents, crystal packing, and thermodynamic corrections. The results demonstrated the superior accuracy of double-hybrid functionals.

Table 1: Performance of DFT Functional Types on the SSCIP6 Benchmark

| Functional Type | Representative Examples | Performance for Iron Porphyrins | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrid (DH) | B2PLYP-D3, DSD-PBEB95-D3 [24] | Highest accuracy; correct ground-state predictions [24] | High computational cost; O(n⁵) scaling [25] |

| Hybrid (Reduced Exact Exchange) | B3LYP*-D3, TPSSh-D3 [24] | Considerably overstabilizes intermediate spin; can lead to incorrect ground-state predictions [24] [2] | Systematic error for Fe(III) porphyrins [24] |

| Local (Semilocal) | M06-L, MN15-L, r²SCAN [9] | Moderate performance for spin states and binding energies [9] | Tendency to stabilize low/intermediate spin states [9] |

| Hybrid (High Exact Exchange) | Various (>10% exact exchange) [9] | Catastrophic failures for some systems (e.g., ferrocene) [26] | Severe over-stabilization of high-spin states [9] |

The SSE17 Benchmark from Experimental Data

A groundbreaking 2024 study introduced the SSE17 benchmark set, derived from experimental data of 17 first-row TMCs, providing some of the most credible reference data to date [2]. The benchmark includes complexes of Fe(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Co(III), Mn(II), and Ni(II) with chemically diverse ligands. The results offer a stark comparison between functional classes.

Table 2: Quantitative Errors in Spin-State Energetics from the SSE17 Benchmark (in kcal/mol)

| Method Type | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Maximum Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 | < 6.0 |

| Hybrid DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 |

| Hybrid DFT | TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5 - 7 | > 10 |

The data reveals that the best-performing DFT methods are double-hybrids, which achieve mean absolute errors below 3 kcal/mol—approaching the accuracy of the highly-regarded CCSD(T) wavefunction method (1.5 kcal/mol MAE) [2]. In contrast, hybrid DFT methods previously recommended for spin-state energetics (B3LYP*-D3(BJ) and TPSSh-D3(BJ)) perform significantly worse, with MAEs of 5-7 kcal/mol and maximum errors exceeding 10 kcal/mol [2].

Performance for Mössbauer Properties and Binding Energies

The superiority of double-hybrid functionals extends beyond spin-state energetics to other key spectroscopic and binding properties. For predicting ⁵⁷Fe Mössbauer nuclear quadrupole splittings (NQS), the double-hybrid functional PBE-0DH demonstrated superior performance with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.20 mm/s compared to experimental values [26]. Notably, for ferrocene—a system with strong static correlations—all hybrid functionals incorporating more than 10% exact exchange failed, while several double-hybrid functionals continued to deliver reliable results [26].

For binding energies of iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins, assessments against the Por21 database of high-level CASPT2 reference energies show that most functionals fail to achieve chemical accuracy (1.0 kcal/mol) by a significant margin [9]. The best-performing methods achieve MUEs of approximately 15.0 kcal/mol, with more modern approximations typically performing better than older functionals [9].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Deriving Benchmark Reference Data from Experiment

The SSE17 benchmark set established reference values for spin-state energetics through careful processing of experimental data, employing two primary approaches [2]:

From Spin Crossover Enthalpies: For complexes exhibiting spin-crossover behavior, the adiabatic spin-state energy splitting (ΔE₍S₁-S₂₎) was derived from the relationship ΔE₍S₁-S₂₎ ≈ ΔH₍S₁→S₂₎ - RT, where ΔH₍S₁→S₂₎ is the enthalpy change for the spin transition obtained from van't Hoff plots of magnetic susceptibility or calorimetric data.

From Spin-Forbidden Absorption Bands: For complexes that do not undergo spin crossover, vertical spin-state splittings were estimated from the energies of spin-forbidden ligand-field absorption bands, carefully identifying the crossing point between potential energy surfaces of different spin states.

In both cases, the raw experimental data were back-corrected for vibrational contributions (zero-point energy and thermal corrections) and environmental effects (solvent or crystal packing) to isolate the electronic energy differences that serve as the benchmark for quantum chemistry methods [2].

Accounting for Crystal Packing Effects in Solid-State Systems

For the SSCIP6 benchmark focused on crystalline iron porphyrins, researchers proposed partitioning the total crystal packing effect (CPE) into additive components [24]:

Direct CPE: The effect of the electrostatic and dispersion interactions between the porphyrin complex and its crystalline environment.

Structural CPE: The effect of the crystal field in modifying the geometry of the porphyrin complex compared to its isolated structure.

This approach enabled the researchers to employ experimental ground-state information to derive quantitative constraints on the electronic energy difference for simplified model systems, creating a robust benchmark for assessing functional accuracy [24].

Computational Workflow for Double-Hybrid Calculations

The typical computational protocol for applying double-hybrid functionals to transition metal complexes involves several key steps, which can be visualized in the following workflow:

Workflow Title: Double-Hybrid Functional Calculation Process

The double-hybrid functional methodology incorporates both DFT and wavefunction components [25]:

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: An initial hybrid Kohn-Sham calculation is performed mixing Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange and correlation: EₓC = (1 - αₓ)Eₓᴅꜰᵀ + αₓEₓᴴᶠ + αCEcᴅꜰᵀ.

MP2 Correlation Energy Calculation: The SCF energy is augmented with a second-order Møller-Plesset (MP2) correlation energy term evaluated using the Kohn-Sham orbitals: Ecᴹᴾ² = -∑ᵢⱼₐբ (ia|jb)[2(ia|jb) - (ib|ja)]/(εₐ + εբ - εᵢ - εⱼ).

Computational Acceleration: To address the O(n⁵) computational scaling of MP2, efficiency improvements include:

Essential Computational Tools for Transition Metal Chemistry

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for TMC Simulation

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| molSimplify [1] | Automated TMC construction | Rapid building and screening of transition metal complexes with various geometries |

| QChASM [1] | Quantum Chemical Assembly | Template-based automated construction of TMCs for high-throughput screening |

| GAMESS [25] | Quantum Chemistry Software Package | Implementation of dual-basis double-hybrid DFT methods with RI approximation |

| tmQM Dataset [1] | Curated Computational Database | Quantum geometries and properties of 86k transition metal complexes for benchmarking |

| SSCIP6 & SSE17 [24] [2] | Benchmark Sets | High-confidence reference data for validating spin-state energetics methods |

Addressing Challenges in Strongly Correlated Systems

Despite their general superiority, double-hybrid functionals—like all single-determinant DFT methods—face limitations for systems with strong static (multireference) correlation. Notably, for particularly challenging species such as [Fe(H₂O)₅NO]²⁺ and FeO₂⁻⁻-porphyrin, none of the tested density functionals yielded satisfactory results [26]. For such systems, it is imperative to explore large-scale multi-configurational methods, as DFT is inherently a single-determinant approach [26].

The comprehensive benchmarking of quantum chemical methods for transition metal complexes provides compelling evidence for the superiority of double-hybrid density functionals in predicting spin-state energetics of iron porphyrins. Through rigorous assessment against experimental reference data, double-hybrids such as B2PLYP-D3, DSD-PBEB95-D3, and PWPB95-D3 consistently achieve higher accuracy than hybrid, meta-hybrid, and semilocal functionals, with mean absolute errors approaching chemical accuracy (< 3 kcal/mol). While their higher computational cost remains a consideration, methodological advances including resolution-of-the-identity approximations and dual-basis techniques are making these methods increasingly applicable to larger, biologically relevant systems. For researchers and drug development professionals investigating heme proteins, biomimetic catalysts, or transition metal-based materials, double-hybrid functionals should be considered the method of choice for reliable spin-state energetics, particularly when correlated with experimental benchmarks for the specific system of interest.

Accurate computational modeling of transition metal complexes (TMCs) is crucial for advancements in catalysis, drug development, and materials science. However, the predictive power of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations for these systems is heavily influenced by two critical factors: the treatment of dispersion interactions and the inclusion of solvation effects. Dispersion corrections account for weak, non-covalent interactions that standard density functionals often miss, while solvation models describe the critical influence of a solvent environment on molecular structure, stability, and reactivity. For TMCs, which frequently operate in solution and exhibit complex electronic structures, neglecting these effects can lead to qualitatively incorrect results. This guide objectively compares the performance of different solvation and dispersion approaches within the context of benchmarking DFT methods for TMC research, providing experimental data and protocols to inform method selection.

Theoretical Background and Key Concepts

Implicit Solvation Models

Implicit solvation models offer a computationally efficient way to approximate solvent effects by representing the solvent as a continuous medium, characterized primarily by its dielectric constant, rather than modeling individual solvent molecules. The solute is placed within a cavity, and the model calculates the stabilization energy resulting from the polarization of the medium by the solute's charge distribution.

The two most prevalent models in quantum chemistry packages like ORCA are the Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) and the Universal Solvation Model (SMD) [27]. In CPCM, the solvation energy is decomposed into an electrostatic component (ΔGENP) and a cavity-dispersion-solvent-structure term (ΔGCDS). The electrostatic contribution is included directly in the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) calculation, leading to "solvated" orbitals. A critical consideration for calculating solution-phase thermodynamics is the inclusion of a concentration correction term (ΔG°_conc = 1.89 kcal/mol) when converting from a gas-phase standard state (1 atm) to a solution standard state (1 mol/L) [27].

The SMD model is considered an advancement over CPCM, as it uses the full solute electron density to compute the non-electrostatic CDS contribution, rather than relying solely on surface-area-based approaches [27]. This makes SMD potentially more accurate but also requires a larger set of solvent-specific parameters. A recent development is the DRACO model, which introduces environment-adaptive atomic radii for constructing the solute cavity, improving the description of charged systems by accounting for variations in local electron density [27].

Dispersion Corrections

Dispersion interactions are long-range electron correlation effects that are not captured by standard local and semi-local DFT approximations. Empirical dispersion corrections, such as the -D3 and -D4 methods developed by Grimme and coworkers, are widely used to address this deficiency. These corrections add a posteriori an energy term (E_disp) to the DFT total energy, based on atom-pairwise potentials that depend on the interatomic distances and element-specific parameters. The inclusion of these corrections has been shown to be critical for accurate predictions, such as reduction potentials, where they consistently improve agreement with experimental benchmarks [28].

Performance Comparison of Methodologies

Benchmarking Solvation Models for Redox Properties

The accuracy of solvation models is highly system-dependent. A study on predicting the aqueous reduction potential of the carbonate radical anion demonstrated that pure implicit solvation methods significantly underperform, capturing only about one-third of the measured potential [28]. This highlights the limitation of implicit models for species with strong, specific solvent interactions.

Table 1: Performance of Solvation Approaches for Carbonate Radical Anion Reduction Potential

| Computational Level | Solvation Model | Key Findings | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ωB97xD/6-311++G(2d,2p) | Implicit Only | Captured only ~1/3 of measured potential | Poor |

| ωB97xD/6-311++G(2d,2p) | Explicit (18 H₂O) + Implicit | Accurate results matching literature | Excellent |

| M06-2X/6-311++G(2d,2p) | Explicit (9 H₂O) + Implicit | Accurate results matching literature | Excellent |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(2d,2p) | Explicit Solvation | Showed improvement but failed to match benchmark | Moderate |

The data shows that a hybrid explicit-implicit approach is necessary for systems with extensive solvent interactions. The number of required explicit water molecules and the final result's accuracy are also functional-dependent [28].

Benchmarking Density Functionals with Dispersion for Spin-State Energetics

The choice of density functional approximation, particularly when paired with dispersion corrections, dramatically impacts the accuracy of calculated spin-state energetics in TMCs. A comprehensive benchmark study (Por21) of 250 electronic structure methods for iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins revealed that most functionals fail to achieve chemical accuracy (1.0 kcal/mol) [29]. Another recent benchmark (SSE17) derived from experimental data of 17 TMCs provides a clear hierarchy of functional performance.

Table 2: Functional Performance for Transition Metal Complex Spin-State Energetics (SSE17 Benchmark)

| Functional Class | Example Functionals | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrids | PWPB95-D3(BJ), B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | < 3.0 kcal/mol | Best performers for spin-state energetics |

| Local Meta-GGAs | GAM, r2SCAN, revM06-L, M06-L | ~15.0 kcal/mol (Por21) [29] | Good compromise for general properties and porphyrins |

| Common Hybrids | B3LYP*-D3(BJ), TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5-7 kcal/mol | Previously recommended, now outperformed |

| High-Exact-Exchange | M06-2X, M06-HF, range-separated | Catastrophic failures (Por21) [29] | Severe over-stabilization of high-spin states |

The best-performing DFT methods for spin-state energetics are double-hybrid functionals like PWPB95-D3(BJ) and B2PLYP-D3(BJ), which outperform the previously recommended functionals like B3LYP* and TPSSh by a significant margin [2]. It is noteworthy that for specific properties, such as the geometry optimization of iron complexes, the meta-hybrid functional TPSSh(D4) has been shown to deliver the best performance [30].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow for Benchmarking Solvation and Dispersion Methods

Adopting a systematic workflow is essential for reliable results. The following diagram outlines a robust protocol for benchmarking computational methods for TMCs in solution.

Detailed Protocol for Single-Point Energy Calculation with CPCM/SMD in ORCA

This protocol is adapted from standard procedures for running implicit solvation calculations in the ORCA software package [27].

Input File Setup: The solvation model is specified directly in the method line of the ORCA input file.

- For CPCM: Use the keyword

!CPCM(solvent), e.g.,!B97M-V DEF2-SVP CPCM(WATER). - For SMD: Use the keyword

!SMD(solvent), e.g.,!B97M-V DEF2-SVP SMD(WATER). - A full list of predefined solvents is available in the ORCA manual. For non-standard solvents, dielectric constant (EPSILON) and refractive index (REFRAC) can be specified manually in the

%CPCMblock.

- For CPCM: Use the keyword

Geometry Specification: The molecular geometry is provided in a separate

.xyzfile referenced in the input, e.g.,* XYZFILE 0 1 aspirin.xyz.Output Analysis: Upon completion, the ORCA output file provides a detailed breakdown of the solvation energy.

- The

CPCM Dielectricterm corresponds to the electrostatic component (ΔG_ENP). - The

SMD CDS (Gcds)orFree-energy (cav+disp)term corresponds to the non-electrostatic component (ΔG_CDS). - The

FINAL SINGLE POINT ENERGYalready includes the ΔGENP term. For SMD, the ΔGCDS term is also included. For CPCM, the cavity term may need to be added separately if calculated.

- The

Concentration Correction: For solution-phase thermodynamics, remember to add the concentration correction term (ΔG°_conc = 1.89 kcal/mol) to the final free energy when converting from a gas-phase reference state [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Modeling TMCs

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Relevance to TMCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSCDB138 [17] | Benchmark Database | Provides gold-standard reference data for validating density functionals. | Contains extensive data on transition-metal reaction energies, enabling rigorous testing. |

| SSE17 [2] | Experimental Benchmark Set | Offers reference spin-state energetics for 17 TMCs derived from experimental data. | Crucial for assessing method performance on a key, challenging property of TMCs. |

| Por21 [29] | Computational Database | High-level (CASPT2) reference energies for spin states and binding in metalloporphyrins. | Useful for benchmarking biologically relevant systems like heme analogs. |

| CPCM/SMD [27] | Implicit Solvation Models | Approximates bulk solvent effects efficiently within SCF calculations. | Essential for modeling TMCs in solution, as required for catalysis and drug binding. |

| D3/D4 Corrections [28] | Empirical Dispersion | Corrects for missing long-range van der Waals interactions in DFT. | Critical for accurate interaction energies, structural prediction, and redox potentials. |

| r2SCAN [29] [17] | Meta-GGA Functional | A modern, non-empirical functional showing strong all-around performance. | Ranked highly for general properties and porphyrin chemistry [29]. Good balance of cost/accuracy. |

| Double-Hybrids (PWPB95) [2] | Double-Hybrid Functional | Incorporates MP2 correlation for high accuracy. | Top performer for spin-state energetics, though computationally expensive [2]. |

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Choosing the right combination of functional, dispersion correction, and solvation model depends on the target property and available computational resources. The following decision diagram provides a guided path for method selection.

This guide has provided a comparative analysis of strategies for modeling solvation and dispersion effects in DFT calculations of transition metal complexes. The key findings indicate that no single functional is universally best, but clear leaders emerge for specific properties: double-hybrid functionals for spin-state energetics, TPSSh for geometries, and modern meta-GGAs like r2SCAN for a balanced cost-to-accuracy profile. Critically, the inclusion of empirical dispersion corrections is non-negotiable for quantitative accuracy. For solvation, while implicit models like CPCM and SMD are essential workhorses, their limitations necessitate hybrid explicit-implicit approaches for properties involving strong, specific solute-solvent interactions. By leveraging benchmark datasets like GSCDB138 and SSE17, and adhering to the detailed protocols and decision framework provided, researchers can make informed, justified choices in their computational models, thereby enhancing the reliability of their predictions in drug development and materials design.

Overcoming Practical Hurdles: Strategies for Robust Geometry Optimization and Active Learning

The Profound Impact of Initial Configuration on Optimization Success

In computational chemistry, the "initial configuration"—the choice of methods and parameters at the outset of a study—profoundly determines the success and reliability of research outcomes, particularly for challenging systems like transition metal complexes. This configuration encompasses the selection of density functional theory (DFT) functionals, basis sets, solvation models, and computational protocols. For researchers investigating catalysis, drug development, and materials design, these initial choices dictate whether calculations yield chemically accurate predictions or misleading results. The challenging electronic structure of transition metals, with their complex spin-state energetics and multi-configurational character, makes them particularly sensitive to methodological choices [21] [7]. Without proper benchmarking and initial configuration, computational studies may produce results that diverge significantly from experimental observations, potentially leading research programs in unproductive directions.

This guide provides an objective comparison of DFT method performance for transition metal complexes, drawing upon recent benchmarking studies that leverage experimental data as reference points. By synthesizing quantitative performance metrics across multiple studies, we aim to equip researchers with evidence-based recommendations for selecting computational methods that balance accuracy with computational efficiency, thereby optimizing the success of their investigative workflows.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparison of Quantum Chemistry Methods

Spin-State Energetics Performance (SSE17 Benchmark Set)

Table 1: Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods for Spin-State Energetics of Transition Metal Complexes

| Method Category | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Maximum Error (kcal/mol) | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 | Highest accuracy reference |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ) | <3.0 | <6.0 | High-accuracy applications |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | <3.0 | <6.0 | High-accuracy applications |

| Traditional Hybrid DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ) | 5-7 | >10 | Not recommended for spin states |

| Traditional Hybrid DFT | TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5-7 | >10 | Not recommended for spin states |

| Meta-Hybrid DFT | TPSSh | Satisfactory* | Satisfactory* | Excited-state dynamics |

Note: CCSD(T) demonstrates the highest accuracy for spin-state energetics, outperforming all tested multireference methods [2] [7]. The TPSSh functional shows satisfactory performance for excited-state dynamics simulations specifically, despite its poorer performance for general spin-state energetics [31].

Performance for Specific Transition Metal Properties

Table 2: Specialized DFT Performance Across Different Transition Metal Properties

| Property | Optimal Method | Performance Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydricity | PBE0-D3(PCM)/def2-TZVP | MAD = 1.4 kcal/mol | Fe and Co hydride complexes [21] |

| Magnetic Exchange Coupling | Scuseria-type RSH | Moderate HF exchange | Di-nuclear complexes [18] |

| Excited-State Dynamics | B3LYP* | Best balanced MLCT-MC energetics | Fe(II) complexes [31] |

| Excited-State Dynamics | TPSSh | Best balanced MLCT-MC energetics | Fe(II) complexes [31] |

| Geometries | RI-BP86-D3(PCM)/def2-SVP | Sufficiently accurate | General 3d TM complexes [21] |

The benchmarking data reveals that double-hybrid functionals (PWPB95-D3(BJ) and B2PLYP-D3(BJ)) achieve remarkable accuracy for spin-state energetics, with mean absolute errors below 3 kcal/mol, rivaling the performance of the more computationally expensive CCSD(T) method for many applications [2]. Conversely, traditionally recommended functionals like B3LYP* and TPSSh demonstrate significantly larger errors (5-7 kcal/mol MAE) in the SSE17 benchmark, highlighting the risk of relying on historical preferences without contemporary benchmarking [7].

For excited-state dynamics, however, B3LYP* and TPSSh emerge as the only functionals that satisfactorily reproduce experimental dynamics for Fe(II) complexes, signaling that the optimal functional depends critically on the specific property under investigation [31]. This underscores the necessity of matching methodological choices to specific research questions rather than seeking universal functionals.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Benchmarking Studies

Benchmarking Spin-State Energetics (SSE17 Protocol)

The SSE17 benchmark set derives reference values from experimental data of 17 first-row transition metal complexes containing Fe(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Co(III), Mn(II), and Ni(II) with chemically diverse ligands [7]. The experimental reference values are obtained from two sources: (1) spin-crossover enthalpies for 9 complexes, and (2) energies of spin-forbidden absorption bands in reflectance spectra for 8 complexes. These experimental values are carefully back-corrected for vibrational and environmental effects (solvation or crystal lattice) to provide electronic energy differences directly comparable with quantum chemistry computations. All DFT and wave function theory calculations are performed on experimentally determined or optimized geometries, with consistent treatment of solvation effects (typically using PCM for homogeneous systems) and dispersion corrections (generally D3 with Becke-Johnson damping) [2] [7].

For property-specific benchmarks, specialized protocols are employed: