Benchmarking Quantum Mechanical Methods for Reaction Pathway Prediction: A Guide for Computational Chemists and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantum mechanical (QM) methods for modeling chemical reaction pathways, a critical task in drug discovery and synthetic methodology development.

Benchmarking Quantum Mechanical Methods for Reaction Pathway Prediction: A Guide for Computational Chemists and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantum mechanical (QM) methods for modeling chemical reaction pathways, a critical task in drug discovery and synthetic methodology development. It explores the foundational theories, from semiempirical to ab initio and density functional theory (DFT), and details their practical application in locating transition states and elucidating mechanisms. The content further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, including the use of hybrid QM/MM and continuum solvation models. Finally, it offers a rigorous framework for validating and benchmarking these computational methods against experimental data and high-level theoretical references, empowering researchers to select the most accurate and efficient approaches for their projects.

Quantum Mechanics in Chemistry: Core Principles for Modeling Reaction Pathways

The Schrödinger equation is the fundamental partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system, forming the cornerstone of quantum chemistry and our understanding of molecular behavior [1]. Its discovery by Erwin Schrödinger in 1925 provided the crucial link between the wave-particle duality of matter and the stable, quantized states observed in atoms and molecules [1] [2]. Conceptually, it serves as the quantum counterpart to Newton's second law in classical mechanics, predicting the evolution of a system's quantum state over time where Newton's laws predict a physical path [1].

The time-independent, non-relativistic Schrödinger equation for a single particle is expressed as:

[ \hat{H}|\Psi\rangle = E|\Psi\rangle ]

where (\hat{H}) is the Hamiltonian operator, (E) is the energy eigenvalue, and (|\Psi\rangle) is the wave function of the system [1]. For chemical systems, solving this equation provides access to molecular structures, energies, reaction pathways, and spectroscopic properties.

However, obtaining exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation for systems with more than one electron is analytically impossible due to the complex nature of electron-electron correlations [3]. This intractability has driven the development of numerous computational approximations, each balancing accuracy against computational cost. These methods, ranging from highly accurate but expensive ab initio post-Hartree-Fock approaches to more efficient Density Functional Theory (DFT) and semi-empirical methods, form the essential toolkit for modern computational chemistry, enabling the study of complex chemical reactions and materials that would otherwise be beyond our analytical reach [3] [4] [5].

A Hierarchy of Computational Approximations

The landscape of computational quantum chemistry methods can be viewed as a hierarchy, where each level introduces specific approximations to the Schrödinger equation to make calculations feasible.

TheAb InitioSuite: From Hartree-Fock to Correlated Methods

Ab initio (Latin for "from the beginning") methods are a class of computational techniques based directly on quantum mechanics, using only physical constants and the positions and number of electrons in the system as input, without relying on empirical parameters [3].

Hartree-Fock (HF) Method: The simplest ab initio approach, where the instantaneous Coulombic electron-electron repulsion is not specifically taken into account; only its average effect (mean field) is included in the calculation. This provides a qualitatively correct but quantitatively inadequate description, as it completely misses electron correlation [3].

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: These methods correct for the electron correlation missing in the HF method. Key approaches include:

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: A hierarchical approach where MP2 (second-order) scales as N⁴, MP3 as N⁶, and MP4 as N⁷, with N being a relative measure of system size [3].

- Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory: A highly accurate method where CCSD scales as N⁶, and CCSD(T) – often called the "gold standard" for single-reference calculations – scales as N⁷ [3].

- Configuration Interaction (CI): A variational approach that converges to the exact solution when all possible configurations are included ("Full CI"), but is computationally prohibitive for all but the smallest systems [3].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Semi-Empirical Methods

Density Functional Theory: As discussed in the benchmarking study, DFT methods like B97-3c, r2SCAN-3c, and ωB97X-3c offer a different approach by expressing the energy as a functional of the electron density rather than the wave function, providing good accuracy with reduced computational cost compared to correlated ab initio methods [5].

Semi-Empirical Quantum Mechanical (SQM) Methods: Approaches like GFN2-xTB and g-xTB incorporate empirical parameters to further reduce computational cost, enabling the study of very large systems, though with potentially lower accuracy for certain properties [5].

Emerging Approaches: Neural Network Potentials and Quantum Computing

Recent advances have introduced novel computational paradigms:

Neural Network Potentials (NNPs): Models like the OMol25-trained NNPs (eSEN and UMA) learn the relationship between molecular structure and energy from large quantum chemistry datasets, offering potentially high speed while maintaining accuracy, even without explicitly considering charge-based physics in their architecture [5].

Quantum Computing Approaches: Variational quantum algorithms represent an emerging frontier, using adaptive quantum circuit evolution to solve electronic structure problems, with potential advantages for specific problem classes [6].

Comparative Performance Benchmarking

The true test of any computational method lies in its ability to reproduce experimental observables and high-level theoretical reference data. Recent comprehensive benchmarks provide critical insights into the performance hierarchy of these methods.

Accuracy in Predicting Reduction Potentials

Reduction potential quantifies the voltage at which a species gains an electron in solution, making it a sensitive probe of a method's ability to handle changes in charge and spin states. The following table compares the performance of various methods on main-group and organometallic datasets:

Table 1: Performance of computational methods for predicting reduction potentials (in Volts) [5]

| Method | System Type | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c | Main-group (OROP) | 0.260 | 0.366 | 0.943 |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.414 | 0.520 | 0.800 | |

| GFN2-xTB | Main-group (OROP) | 0.303 | 0.407 | 0.940 |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.733 | 0.938 | 0.528 | |

| UMA-S (NNP) | Main-group (OROP) | 0.261 | 0.596 | 0.878 |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.262 | 0.375 | 0.896 | |

| UMA-M (NNP) | Main-group (OROP) | 0.407 | 1.216 | 0.596 |

| Organometallic (OMROP) | 0.365 | 0.560 | 0.775 |

The data reveals that the B97-3c functional excels for main-group systems, while the UMA-S neural network potential shows remarkable consistency across both main-group and organometallic species, outperforming GFN2-xTB for organometallics. Interestingly, the neural network potentials demonstrate a reversed accuracy trend compared to traditional methods, performing better on organometallic species than on main-group compounds [5].

Performance in Calculating Electron Affinities

Electron affinity measures the energy change when a species gains an electron in the gas phase, providing another stringent test of methodological accuracy, particularly for charge-related properties.

Table 2: Performance of computational methods for predicting electron affinities (in eV) [5]

| Method | Main-Group Species (MAE) | Organometallic Species (MAE) |

|---|---|---|

| r2SCAN-3c | 0.087 | 0.234 |

| ωB97X-3c | 0.082 | 0.191* |

| g-xTB | 0.136 | 0.298 |

| GFN2-xTB | 0.178 | 0.330 |

| UMA-S (NNP) | 0.123 | 0.186 |

| UMA-M (NNP) | 0.160 | 0.252 |

Note: ωB97X-3c encountered convergence issues with some organometallic structures [5]

For electron affinities, DFT methods (r2SCAN-3c and ωB97X-3c) achieve the highest accuracy for main-group species, while the UMA-S neural network potential performs competitively for organometallic systems, surpassing even the DFT functionals for this challenging class of compounds [5].

Case Study: Mapping Reaction Pathways for RDX Decomposition

The thermal decomposition of the energetic material RDX (research department explosive) provides an excellent case study for comparing how different approximations to the Schrödinger equation handle complex reaction pathways with competing mechanisms.

Experimental Protocol and Computational Methodology

In a comprehensive quantum mechanics investigation of RDX decomposition, researchers employed both experimental and computational approaches [4]:

Experimental Technique: Confined Rapid Thermolysis (CRT) coupled with FTIR and Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (ToFMS) to identify decomposition products from approximately 0.5 mg samples heated to 515 K, with sensitivity to liquid-phase processes [4].

Computational Methods: Density functional theory (DFT) with the B3LYP functional and 6-311++G(d,p) basis set was used to optimize geometries and locate transition states. Solvent effects for the liquid phase were incorporated using the SMD solvation model, and final energies were refined using high-level ab initio methods like G3B3 and CCSD(T) [4].

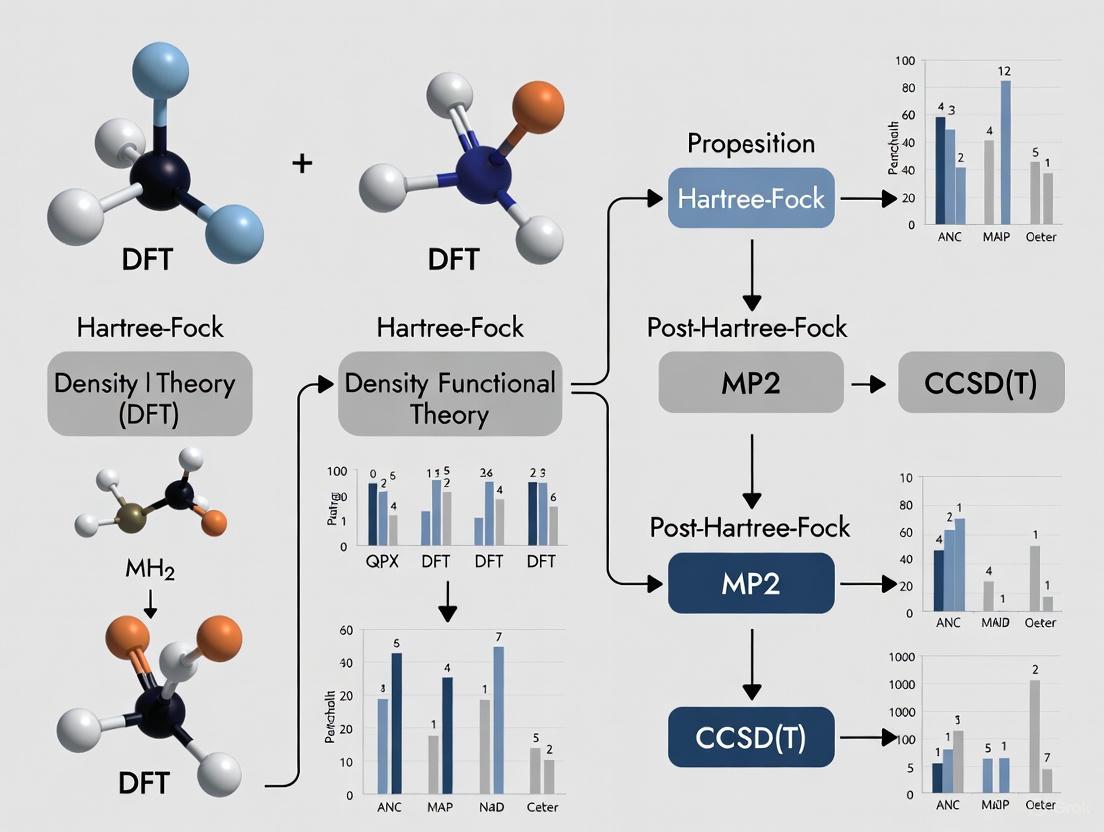

The relationship between the fundamental Schrödinger equation and the various computational approximations used in such investigations can be visualized as follows:

Competing Reaction Pathways Revealed Through Computational Chemistry

The study identified five competing initial reaction pathways for RDX decomposition, with barriers and energetics critically dependent on the computational method used [4]:

Table 3: Competing initial decomposition pathways for RDX in liquid phase [4]

| Pathway | Description | Key Products | Barrier (kcal/mol) | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | HONO elimination | INT175 + HONO | ~39.2 | B3LYP/SMD |

| P2 | N‑NO₂ homolysis | RDR + NO₂ | ~39.0 | B3LYP/SMD |

| P3 | Reaction with NO | ONDNTA | ~42.5 | B3LYP/SMD |

| P4 | Prompt oxidation | HONO/ONNO₂ adducts | ~35.2 | B3LYP/SMD |

| P5 | Hydrogen abstraction | Various radicals | ~41.8 | B3LYP/SMD |

The intricate network of these competing pathways and their subsequent ring-opening reactions can be mapped as:

The investigation revealed that early ring-opening reactions occur through multiple simultaneous pathways, with the dominant mechanism shifting depending on environmental conditions. Particularly important was the discovery that bimolecular reactions and autocatalytic pathways (P4 and P5) play crucial roles in liquid-phase decomposition, explaining previously unaccounted-for experimental observations such as the formation of highly oxidized carbon species [4].

Modern computational chemistry relies on a sophisticated ecosystem of software tools, methods, and theoretical approaches.

Table 4: Essential computational resources for quantum chemistry studies [3] [4] [5]

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | Gaussian 09, Psi4 | Quantum chemistry calculations | Method development, application studies |

| Density Functionals | B3LYP, B97-3c, ωB97X-3c | Electron correlation treatment | Balanced accuracy/cost studies |

| Basis Sets | 6-311++G(d,p), def2-TZVPD | Spatial resolution for orbitals | Systematic improvement of accuracy |

| Semi-empirical Methods | GFN2-xTB, g-xTB | Rapid geometry optimization | Large system screening, MD simulations |

| Neural Network Potentials | UMA-S, UMA-M, eSEN | Machine-learned energy prediction | High-throughput screening, dynamics |

| Solvation Models | SMD, CPCM-X | Implicit solvent effects | Solution-phase reaction modeling |

The Schrödinger equation remains the indispensable foundation of quantum chemistry, but its practical application requires carefully chosen approximations tailored to specific research questions. Our comparison reveals that:

For maximum accuracy in small systems, coupled cluster methods like CCSD(T) provide benchmark quality, but at computational costs that limit application to larger molecules [3].

For balanced performance across chemical space, modern density functionals like B97-3c and ωB97X-3c offer excellent accuracy for both energies and properties, explaining their widespread adoption [5].

For high-throughput screening and dynamics simulations of large systems, neural network potentials like UMA-S show remarkable promise, achieving competitive accuracy without explicit physical models of electron interaction [5].

For complex reaction networks like RDX decomposition, DFT methods with appropriate solvation models successfully unravel intricate competing pathways, demonstrating the crucial role of computational chemistry in elucidating mechanisms that are experimentally inaccessible [4].

The optimal approximation depends critically on the target system size, property of interest, and available computational resources. As method development continues, particularly in machine learning and quantum computing, the accessible chemical space will expand further, but the Schrödinger equation will remain the fundamental theory from which all these approximations derive their power and legitimacy.

In the field of computational chemistry, particularly for modeling reaction pathways in drug discovery and materials science, researchers navigate a hierarchical spectrum of quantum mechanical methods. This spectrum represents a fundamental trade-off between computational cost and accuracy, requiring scientists to match the method to the specific research question and available resources. Semiempirical methods, Density Functional Theory (DFT), and ab initio post-Hartree-Fock techniques form the core of this hierarchy, each with distinct capabilities and limitations for predicting molecular structures, energies, and reaction mechanisms [7] [8].

The choice of method is not merely technical but fundamentally influences research outcomes. For instance, in pharmaceutical research, accurately predicting drug-protein interaction energies or reaction barriers is essential for reducing costly late-stage failures [7]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these quantum mechanical methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers in selecting appropriate computational tools for reaction pathway analysis.

Theoretical Foundation and Method Hierarchies

The Accuracy-Cost Spectrum

Computational quantum methods exist along a continuous spectrum where increasing accuracy typically demands exponentially greater computational resources. At one end lie semiempirical methods which employ extensive approximations and parameterization to achieve computational speeds thousands of times faster than standard DFT [8]. In the middle range, Density Functional Theory offers a balance between accuracy and cost for many chemical systems, while ab initio post-Hartree-Fock methods (such as coupled-cluster theory) reside at the high-accuracy end, providing benchmark-quality results for smaller systems but becoming prohibitively expensive for large biomolecules [7] [9].

Fundamental Theoretical Differences

The mathematical foundations differentiate these methodological classes. Semiempirical methods simplify the quantum mechanical Hamiltonian by neglecting or approximating many electronic integrals, introducing parameters fitted to experimental data or higher-level computations [8]. For example, Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB), a semiempirical method derived from DFT, expands the total energy in a Taylor series around a reference density and truncates at different orders (DFTB1, DFTB2, DFTB3), with each level incorporating progressively more terms from the expansion [8].

In contrast, DFT methods compute the electron density directly using exchange-correlation functionals without empirical parameterization for specific elements, while ab initio post-Hartree-Fock methods systematically approximate the electron correlation energy missing in the Hartree-Fock method through mathematically rigorous approaches like perturbation theory (MP2, MP4) or coupled-cluster theory (CCSD(T)) [9]. These fundamental differences in approach directly impact their computational scaling: semiempirical methods typically scale as O(N²) to O(N³), DFT generally O(N³) to O(N⁴), and high-level ab initio methods can scale from O(N⁵) to O(N⁷) or worse, where N represents system size [8].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Accuracy Benchmarks for Isomerization Enthalpies

A comprehensive study evaluating gas-phase isomerization enthalpies for organic compounds provides critical benchmarking data across methodological classes. The research examined 562 isomerization reactions spanning pure hydrocarbons and nitrogen-, oxygen-, sulfur-, and halogen-substituted hydrocarbons using multiple theoretical methods [9]. The following table summarizes key performance metrics:

Table 1: Performance of quantum mechanical methods for calculating isomerization enthalpies

| Methodological Class | Specific Method | Basis Set | Mean Signed Error (MSE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semiempirical | AM1 | - | 2.93 kcal/mol | 3.58 kcal/mol |

| Semiempirical | PM3 | - | 2.37 kcal/mol | 2.96 kcal/mol |

| Semiempirical | PM6 | - | 1.51 kcal/mol | 2.14 kcal/mol |

| DFT | B3LYP | 6-31G(d) | 1.84 kcal/mol | 2.19 kcal/mol |

| DFT | B3LYP | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | 0.68 kcal/mol | 0.96 kcal/mol |

| DFT | M06-2X | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | 0.32 kcal/mol | 0.63 kcal/mol |

| Ab Initio Post-HF | G3(MP2) | - | 0.30 kcal/mol | 0.61 kcal/mol |

| Ab Initio Post-HF | G4 | - | 0.21 kcal/mol | 0.52 kcal/mol |

The data reveals clear hierarchical patterns. Semiempirical methods show the largest errors (MAEs of 2.14-3.58 kcal/mol), with PM6 performing best in this class. DFT methods demonstrate significantly improved accuracy, particularly with larger basis sets (MAEs of 0.63-2.19 kcal/mol), while ab initio post-Hartree-Fock composite methods (G3(MP2) and G4) deliver the highest accuracy, with MAEs below 1 kcal/mol, essential for precise reaction barrier predictions [9].

Computational Efficiency Comparison

The computational cost hierarchy presents the practical constraint in method selection. Quantitative assessments show that semiempirical methods like DFTB are approximately three orders of magnitude faster than DFT with medium-sized basis sets, while DFT is about three orders of magnitude faster than empirical force field methods (Molecular Mechanics) [8]. This efficiency enables molecular dynamics simulations on nanosecond timescales with DFTB compared to picosecond timescales with conventional DFT for comparable systems [8].

Table 2: Computational efficiency and typical application ranges

| Method Class | Relative Speed | Typical System Size | Time Scales for MD | Reaction Modeling Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semiempirical | 1000× faster than DFT | 100-10,000 atoms | Nanoseconds | Limited to parametrized reactions |

| DFT | Benchmark | 10-1000 atoms | Picoseconds | Broad, including bond breaking/formation |

| Ab Initio Post-HF | 10-1000× slower than DFT | 3-50 atoms | Not practical | High accuracy for small systems |

This efficiency hierarchy enables specific application ranges: semiempirical methods for large systems (e.g., proteins) and long timescales, DFT for medium-sized systems and reaction pathways, and ab initio methods for benchmark calculations on model systems [8].

Methodological Protocols and Workflows

Selecting Computational Methods: A Decision Hierarchy

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting quantum mechanical methods based on research objectives and constraints:

Reaction Pathway Analysis Protocol

For mapping reaction pathways, a multi-level computational approach provides both efficiency and accuracy:

Initial Conformational Sampling: Utilize semiempirical methods (PM7, DFTB) or molecular mechanics to explore potential energy surfaces and identify stable conformers and approximate transition states [8] [9].

Geometry Optimization: Refine molecular structures of reactants, products, and transition states using DFT with medium-sized basis sets (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G* or M06-2X/6-31G*) [9].

Energy Refinement: Perform single-point energy calculations on optimized geometries using higher-level methods (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP or G4) for thermochemical accuracy [9].

Solvation and Environmental Effects: Incorporate implicit solvation models (PCM, SMD) or explicit solvent molecules, potentially using QM/MM approaches for biological systems [8].

Thermochemical Corrections: Calculate zero-point energies, thermal corrections, and entropy contributions using frequency analyses at the optimization level to obtain Gibbs free energies [9].

This protocol balances computational efficiency with accuracy, leveraging the strengths of each methodological tier while mitigating their respective limitations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential computational tools for quantum mechanical calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semiempirical Software | MOPAC, DFTB+ | Fast geometry optimization, molecular dynamics | Large system preliminary screening, nanosecond MD |

| DFT Packages | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Electronic structure, reaction pathways, spectroscopy | Reaction mechanism studies, excitation energies |

| Ab Initio Packages | GAMESS, Molpro, NWChem | High-accuracy benchmark calculations | Small system thermochemistry, method validation |

| Composite Methods | Gaussian-n series, CBS | High-accuracy thermochemistry via approximation schemes | Benchmark reaction energies and barriers |

| Plane-Wave DFT | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Periodic boundary conditions, solid-state systems | Catalytic surfaces, materials science |

| Quantum/Molecular Mechanics | AMBER, CHARMM, QSimulate QUELO | Multi-scale modeling of biological systems | Enzyme catalysis, drug-protein interactions [10] |

| Visualization & Analysis | GaussView, VMD, Jmol | Molecular structure visualization, property analysis | Results interpretation, publication graphics |

| Force Field Packages | AMBER, CHARMM, OpenMM | Classical molecular dynamics | Conformational sampling of large biomolecules |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of computational quantum chemistry is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends bridging methodological hierarchies. Hybrid quantum-classical approaches are gaining prominence, particularly for drug discovery applications where companies like QSimulate are developing quantum-informed simulation tools that operate on classical computers but incorporate quantum mechanical principles for increased accuracy [10]. These approaches can provide speed improvements of up to 1000× compared to traditional methods, reducing processes that once took months to just hours [10].

Another significant trend involves integrating machine learning with quantum chemistry. For instance, Qubit Pharmaceuticals has introduced foundation models built entirely on synthetic quantum chemistry simulations, enabling reactive molecular dynamics at unprecedented scales while maintaining quantum accuracy [10]. Similarly, hierarchical quantum computing architectures are being developed to distribute quantum computations across multiple systems, potentially enabling more complex simulations as quantum hardware advances [11].

For reaction pathway research specifically, methodological development continues to address known limitations. DFT functionals are being refined for more accurate treatment of dispersion interactions and reaction barriers, while semiempirical methods are expanding parameterization to broader chemical spaces, including transition metals [8] [9]. These advances progressively narrow the accuracy gaps between methodological tiers while expanding their accessible application domains.

The study of chemical reaction mechanisms relies fundamentally on three interconnected concepts: the Potential Energy Surface (PES), Transition States (TS), and the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC). Together, these constructs provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how molecular systems evolve from reactants to products, enabling researchers to predict reaction rates, optimize catalysts, and design novel chemical entities in fields including pharmaceutical development. The PES represents the energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates, conceptually similar to a topographical map where valleys correspond to stable molecular geometries and mountain passes represent transition states between them [12]. First-order saddle points on this surface, the transition states, are characterized by having a zero gradient in all directions but exactly one negative eigenvalue in the Hessian matrix (the matrix of second derivatives), indicating precisely one direction of negative curvature [13]. The IRC, originally defined by Fukui, is the minimum energy pathway in mass-weighted coordinates connecting transition states to reactants and products, representing the path a molecule would follow with zero kinetic energy moving down the reactant and product valleys [14] [15] [16].

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

The Potential Energy Surface (PES)

The Potential Energy Surface is governed by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motion, allowing the electronic Schrödinger equation to be solved for fixed nuclear positions [17]. Mathematically, this enables the representation of the potential energy as ( V(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{electronic}}(\mathbf{R}) + \sum{i>j} \frac{Zi Zj e^2}{4\pi\epsilon0|\mathbf{R}i - \mathbf{R}j|} ), where ( \mathbf{R} ) represents nuclear coordinates, ( E{\text{electronic}} ) is the energy from solving the electronic Schrödinger equation, and the final term represents nuclear repulsion energy [17]. Critical points on the PES occur where the gradient vanishes (( \nabla V(\mathbf{R}) = 0 )), with their character determined by the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix [17].

- Local Minima: All eigenvalues are positive; represent stable reactant, product, or intermediate structures.

- First-Order Saddle Points (Transition States): Exactly one negative eigenvalue; represent the highest energy point along the minimum energy path between minima.

- Higher-Order Saddle Points: Multiple negative eigenvalues; generally less chemically relevant [17].

The PES can be classified as attractive (early-downhill) or repulsive (late-downhill) based on bond length extensions in the activated complex relative to reactants and products, which determines how reaction energy is distributed [12].

Transition State Theory

Transition states are defined as the highest energy point on the minimum energy path between reactants and products, characterized by a zero gradient in all directions and a single imaginary frequency (negative eigenvalue in the Hessian) [13]. In the words of Kenichi Fukui, transition states represent "the highest energy point on the lowest-energy path connecting reactants and products" [15]. Identifying these first-order saddle points is computationally challenging due to the high-dimensional space molecules inhabit, requiring specialized optimization algorithms that maximize energy along the reaction coordinate while minimizing energy along all other coordinates [13].

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Theory

The IRC provides a rigorous definition of the reaction pathway, essentially constituting a sequence of small, steepest-descent paths going downhill from the transition state [14]. Formally, the IRC path is defined in mass-weighted Cartesian coordinates, following the path of maximum instantaneous acceleration rather than simply the steepest descent direction, making it somewhat related to molecular dynamics methods [18]. The IRC can be calculated using various algorithms, with the Gonzalez-Schlegel method implementing a predictor-corrector approach where the calculation involves walking down the IRC in steps with fixed step size, each step involving a constrained optimization on a hypersphere to remain on the true reaction path [16].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Transition State Optimization Methods

Locating transition states requires specialized computational approaches, several of which are compared below:

Synchronous Transit Methods: These include Linear Synchronous Transit (LST), which naïvely interpolates between reactants and products to find the highest energy point, and Quadratic Synchronous Transit (QST), which uses quadratic interpolation to provide greater flexibility. QST3, which incorporates an initial TS guess, is particularly robust for recovering proper transition states even from poor initial guesses [13].

Elastic Band Methods: The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method places multiple images (nodes) along a guess pathway connected by spring forces. Forces are decomposed into tangent and normal components, with only the tangent component of the spring force and normal component of the gradient used to optimize nodes, preventing "corner-cutting." Climbing-Image NEB (CI-NEB) further improves this by allowing the highest energy image to climb up the gradient along the tangent while minimizing energy in other directions [13].

Channel Following Methods: The Dimer method estimates local curvature using a pair of geometries separated by a small distance (the "dimer"), avoiding explicit Hessian calculation. The dimer is rotated to find the direction of lowest curvature, then steps are taken uphill along this direction until a saddle point is reached [13].

Coordinate-Driven Methods: Constrained optimization involves guessing the local geometry of the transition state and fixing key coordinates (bonds, angles, dihedrals) involved in the transition mode while optimizing all other coordinates [13].

IRC Calculation Protocols

IRC calculations follow specific algorithmic procedures, typically involving nested loops with the outer loop running over IRC points and the inner loop performing geometry optimization at each point [18]. The Gonzalez-Schlegel method implements this through a specific workflow:

- Initialization: Starting from a verified transition state geometry with computed Hessian, determine the initial direction using the eigenvector corresponding to the imaginary frequency [14] [16].

- Step Construction: From point P1 on the path, construct an auxiliary point P' at a distance of step-size/2 along the tangent direction [16].

- Constrained Optimization: On a hypersphere of radius step-size/2 centered at P', search for the point of lowest energy P2 through constrained optimization, requiring multiple energy and gradient calculations [16].

- Convergence Check: Check if geometry convergence criteria are fulfilled along the pathway. If the angle between successive steps becomes smaller than 90 degrees, the calculation may switch to direct energy minimization [18].

- Path Completion: Repeat until maximum steps reached or minima identified, then perform in both forward and reverse directions from the TS [14] [18].

Different software packages implement IRC with specific parameters. For example, in Q-Chem, key $rem variables include RPATH_COORDS (coordinate system), RPATH_DIRECTION, RPATH_MAX_CYCLES, RPATH_MAX_STEPSIZE, and RPATH_TOL_DISPLACEMENT [14]. In Gaussian, the step size is specified via irc=(stepsize=n) in units of 0.01 amu⁻⁰·⁵Bohr, with typical values of 10 for normal systems or 3 for strongly curved paths [16].

Diagram 1: IRC Calculation Workflow. Illustrates the iterative predictor-corrector algorithm used in IRC path following.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

Electronic Structure Methods for PES Construction

The accuracy of PES, TS, and IRC calculations depends critically on the chosen electronic structure method. The following table compares popular quantum chemical methods used in computational chemistry:

Table 1: Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for Reaction Pathway Analysis

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wavefunction theory, mean-field approximation | Low | Fast calculations, systematic improvability | Lacks electron correlation, poor reaction barriers | Initial scanning, educational purposes |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron density functional | Moderate | Good accuracy/cost balance, includes electron correlation | Functional-dependent results | Routine reaction modeling, large systems |

| ωB97X-3c | Composite DFT with dispersion correction | Moderate-high | 5.2 kcal/mol MAE, good for halogens, comparable to quadruple-zeta [19] | More expensive than minimal basis DFT | Accurate benchmarking, halogen-containing systems |

| MP2 | Perturbation theory | High | Includes electron correlation, systematically improvable | Fails for diradicals, spin-contamination | When DFT unreliable, initial high-level guess |

| CCSD(T) | Coupled-cluster theory | Very high | "Gold standard" for single-reference systems | Prohibitively expensive for large systems | Final high-accuracy validation |

Recent benchmarking on the DIET test set shows that the ωB97X-3c composite method achieves a weighted mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.2 kcal/mol with a computational time of 115 minutes per calculation, representing an optimal compromise between accuracy and efficiency—delivering quadruple-zeta quality at significantly reduced cost [19]. In comparison, ωB97X-D4/def2-QZVPPD achieved the best accuracy (4.5 kcal/mol weighted MAE) but required 571 minutes per calculation, while ωB97X/6-31G(d) showed unacceptably high weighted MAEs of 15.2 kcal/mol [19].

IRC Algorithm Performance Characteristics

Different IRC algorithms exhibit distinct performance characteristics and limitations:

Table 2: Comparison of IRC Algorithms and Implementation

| Algorithm/Software | Methodology | Step Control | Convergence Behavior | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Chem (Schmidt et al.) | Predictor-corrector with gradient bisector and line search [14] | Fixed step size, default 0.15 a.u. [14] | Reduced "stitching" (zig-zag) behavior [14] | Improved stability over basic steepest descent |

| Gaussian (Gonzalez-Schlegel) | Hypersphere-based constrained optimization [16] | User-defined step size (default 10, ~0.1 amu⁻⁰·⁵Bohr) [16] | Requires proper convergence criteria setting [16] | Well-established, widely available |

| AMS | Mass-weighted coordinate following [18] | Adaptive step reduction for high curvature [18] | Automatic switching to minimization near endpoints [18] | Robust handling of path termination |

The predictor-corrector algorithm developed by Ishida et al. and improved by Schmidt et al. addresses the fundamental limitation of basic steepest-descent methods, which tend to "stitch" back and forth across the true reaction path [14]. This method involves a second gradient calculation after the initial steepest-descent step, followed by a line search along the gradient bisector to return to the correct path [14].

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Reaction Research

Drug Discovery Applications

The integration of PES, TS, and IRC analysis into pharmaceutical research enables more predictive modeling of drug-receptor interactions, metabolic pathways, and reactivity. Quantum-informed approaches are particularly valuable for modeling peptide drugs, covalent inhibitors, and halogen-containing compounds, which constitute approximately 25% of pharmaceuticals [19] [10]. For instance, hybrid quantum-classical approaches have been successfully applied to model prodrug activation and covalent inhibitors targeting the cancer-associated KRAS G12C mutation, providing more accurate predictions of molecular behavior, reaction pathways, and electronic properties than classical methods alone [10]. Companies like QSimulate have developed quantum-enabled platforms (QUELO) that claim to accelerate molecular modeling by up to 1000× compared to traditional methods, reducing processes that once took months to just hours [10].

Dataset Development for Machine Learning

Large-scale reaction pathway datasets are crucial for training machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that combine quantum accuracy with classical speed. The Halo8 dataset represents a significant advance, comprising approximately 20 million quantum chemical calculations from 19,000 unique reaction pathways incorporating fluorine, chlorine, and bromine chemistry [19]. This dataset, generated using a multi-level workflow achieving a 110-fold speedup over pure DFT approaches, provides diverse structural distortions and chemical environments essential for training reactive MLIPs applicable to pharmaceutical discovery [19]. Such datasets address the critical limitation of existing MLIPs trained predominantly on equilibrium structures with limited halogen coverage, enabling more accurate modeling of halogen-specific reactive phenomena like halogen bonding in transition states and polarizability changes during bond breaking [19].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Reaction Pathway Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Software package | Industry standard, comprehensive IRC implementation [16] | General reaction mechanism studies |

| Q-Chem | Software package | Advanced methods, efficient IRC with predictor-corrector [14] | High-accuracy reaction pathway mapping |

| ORCA | Software package | Free, efficient, user-friendly interface [19] | Accessible high-performance computation |

| AMS | Software package | IRC with automatic termination, robust restarts [18] | Complex reaction network exploration |

| Halo8 Dataset | Training data | 20M calculations, halogen chemistry coverage [19] | MLIP training for pharmaceutical applications |

| Transition1x | Training data | Large-scale reaction pathways (C, N, O) [19] | MLIP training for organic reactions |

| ωB97X-3c | DFT method | Optimal accuracy/cost for reaction barriers [19] | Benchmark studies of reaction pathways |

| Dandelion | Computational workflow | Automated reaction discovery, 110× speedup [19] | High-throughput reaction screening |

Diagram 2: PES Topology and IRC Path. Shows the relationship between reactants, transition state, products, and the intrinsic reaction coordinate on a potential energy surface.

The integrated framework of Potential Energy Surfaces, Transition States, and Intrinsic Reaction Coordinates provides an essential foundation for understanding and predicting chemical reactivity across diverse applications from fundamental chemistry to drug discovery. Current methodological advances focus on improving the accuracy and efficiency of these calculations through better density functionals (e.g., ωB97X-3c), robust algorithms for locating and verifying transition states, and sophisticated path-following techniques. The growing integration of quantum mechanical data with machine learning approaches promises to further revolutionize this field, enabling the exploration of complex reaction networks and the design of novel transformations with unprecedented precision. As hybrid quantum-classical methods mature and large-scale reaction datasets like Halo8 become available, researchers gain increasingly powerful tools to navigate chemical space and accelerate the discovery of new pharmaceuticals and materials.

The Critical Role of Basis Sets in Balancing Computational Cost and Accuracy

In computational chemistry, the prediction of reaction pathways is fundamental to advancements in pharmaceutical discovery and materials design. The accuracy of these quantum mechanical simulations hinges on a critical choice: the selection of an atomic orbital basis set. This choice dictates the trade-off between computational cost and the physical realism of the resulting model. Diffuse functions, while essential for modeling key interactions like halogen bonding and van der Waals forces, can drastically reduce the sparsity of the one-particle density matrix, creating a significant computational bottleneck [20]. This guide provides an objective comparison of popular basis sets, evaluating their performance and cost to help researchers make informed decisions for reaction pathway studies.

Quantitative Comparison of Basis Set Performance

The performance of a basis set is measured by its ability to reproduce accurate interaction energies, particularly for non-covalent interactions (NCIs), which are crucial in biochemical systems. The following table summarizes key metrics for selected standard and diffuse-augmented basis sets, using the ωB97X-V density functional and referenced to the high-level aug-cc-pV6Z basis set [20].

Table 1: Performance and Cost Metrics of Selected Basis Sets

| Basis Set | Type | Total RMSD (M+B) (kJ/mol) | NCI RMSD (M+B) (kJ/mol) | Relative Compute Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| def2-SVP | Standard | 33.32 | 31.51 | 151 |

| def2-TZVP | Standard | 17.36 | 8.20 | 481 |

| def2-QZVP | Standard | 16.53 | 2.98 | 1,935 |

| cc-pVDZ | Standard | 32.82 | 30.31 | 178 |

| cc-pVTZ | Standard | 18.52 | 12.73 | 573 |

| cc-pV5Z | Standard | 16.46 | 2.81 | 6,439 |

| def2-SVPD | Diffuse-Augmented | 26.50 | 7.53 | 521 |

| def2-TZVPPD | Diffuse-Augmented | 16.40 | 2.45 | 1,440 |

| aug-cc-pVDZ | Diffuse-Augmented | 26.75 | 4.83 | 975 |

| aug-cc-pVTZ | Diffuse-Augmented | 17.01 | 2.50 | 2,706 |

Key Insights from Performance Data:

- The Necessity of Diffuse Functions: The data shows that unaugmented basis sets, even large ones like def2-QZVP and cc-pV5Z, struggle to achieve high accuracy for non-covalent interactions (NCI RMSD > 2.8 kJ/mol). In contrast, medium-sized diffuse-augmented basis sets like def2-TZVPPD and aug-cc-pVTZ deliver excellent NCI accuracy (NCI RMSD ~2.5 kJ/mol) at a fraction of the cost of massive standard sets [20].

- The Onset of Sufficient Accuracy: For systems where NCIs are critical, def2-TZVPPD and aug-cc-pVTZ represent a "sweet spot," being the smallest basis sets where the combined method and basis set error is sufficiently converged [20].

- The Blessing and Curse of Diffuse Functions: While essential for accuracy, diffuse functions significantly increase computational time and reduce the sparsity of the one-particle density matrix. This "curse of sparsity" can push linear-scaling algorithms into impractical regimes, as even medium-sized diffuse basis sets can eliminate usable sparsity in large systems like DNA fragments [20].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

The quantitative data presented in Table 1 is derived from rigorous benchmarking protocols. Understanding these methodologies is critical for evaluating the results and designing new studies.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Basis Set Benchmarking

| Protocol Component | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Database | Use of the ASCDB benchmark, which contains a statistically relevant cross-section of relative energies for various chemical problems, including a dedicated subset for non-covalent interactions (NCI) [20]. | Provides a comprehensive and representative test set to ensure benchmarking results are generalizable beyond single-molecule cases. |

| Reference Method | Calculations are performed with a robust, modern density functional like ωB97X-V. The results are referenced against those obtained with a very large, near-complete basis set (e.g., aug-cc-pV6Z) [20]. | Establishes a reliable baseline for "truth," allowing for the quantification of errors from smaller basis sets. |

| Error Metric | Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of relative energies, calculated for the entire database and specifically for the NCI subset. No counterpoise corrections are applied in the cited data [20]. | Quantifies the average error magnitude, with a focus on the chemically critical domain of non-covalent interactions. |

| Cost Metric | Wall-clock time for a single SCF calculation on a standardized system (e.g., a 260-atom DNA fragment) [20]. | Provides a practical, empirical measure of computational expense that incorporates the basis set's impact on SCF convergence. |

Visualizing the Basis Set Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and trade-offs involved in selecting a basis set for reaction pathway studies, integrating the factors of accuracy, cost, and sparsity.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Reaction Pathway Studies

Beyond basis sets, modern computational studies of reaction pathways rely on a suite of tools and datasets. The following table details essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Datasets for Reaction Pathway Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Halo8 Dataset [19] | Quantum Chemical Dataset | Provides ~20 million quantum chemical calculations across 19,000 reaction pathways, incorporating fluorine, chlorine, and bromine chemistry to train machine learning interatomic potentials. |

| ωB97X-3c Composite Method [19] | Quantum Chemical Method | Offers an optimal balance of accuracy and cost for large datasets, providing near quadruple-zeta quality with a triple-zeta computational cost, including dispersion corrections. |

| Dandelion Pipeline [19] | Computational Workflow | An efficient multi-level (xTB/DFT) pipeline for reaction discovery and pathway characterization, achieving a 110-fold speedup over pure DFT approaches. |

| ARplorer [21] | Automated Reaction Exploration Program | Integrates QM methods with rule-based approaches and LLM-guided chemical logic to automate the exploration of potential energy surfaces and identify multistep reaction pathways. |

| FlowER [22] | Generative AI Reaction Model | Uses a bond-electron matrix to predict reaction outcomes while strictly adhering to physical constraints like conservation of mass and electrons. |

| Complementary Auxiliary Basis Set (CABS) [20] | Computational Correction | A proposed solution to the diffuse basis set conundrum, which can help recover accuracy with more compact basis sets by correcting for basis set incompleteness. |

The critical trade-off between computational cost and accuracy, governed by basis set selection, is a central challenge in simulating reaction pathways. For systems where non-covalent interactions, halogen chemistry, or high-accuracy reaction barriers are paramount, diffuse-augmented triple-zeta basis sets like def2-TZVPPD or aug-cc-pVTZ represent a scientifically justified and computationally feasible standard [19] [20]. However, for initial screening of very large systems or when such interactions are less critical, standard triple-zeta or double-zeta basis sets offer a pragmatic alternative. The emerging integration of these calculations with large-scale datasets and machine learning potentials further underscores the need for strategic basis set choices that ensure data quality without rendering computations prohibitively expensive [19] [10]. The ongoing development of methods like the CABS correction promises to help navigate this enduring conundrum [20].

Practical Application: Selecting and Applying QM Methods for Reaction Discovery

This guide provides an objective comparison of quantum mechanical methods for studying chemical reaction pathways, a critical task in fields like pharmaceutical development. It evaluates methods based on their theoretical foundations, computational cost, and performance on benchmark systems, supported by experimental data.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each method.

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Representative Cost (vs. DFT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | Multireference Wavefunction: Divides orbitals into inactive, active, and virtual spaces; performs full CI within the active space [23]. | Gold standard for multireference systems (e.g., bond breaking, diradicals, excited states); treats static correlation exactly within the active space [23]. | Exponential cost scaling with active space size; limited to ~18 electrons in 18 orbitals; requires expert selection of active space [23]. | Significantly higher (often 10-100x) |

| SAC-CI | Wavefunction-Based: Linked to cluster expansion theory; describes ground, excited, ionized, and electron-attached states [24]. | Accurate for various electron processes (excitation, ionization); size-consistent; good for molecular spectroscopy [24] [25]. | Higher computational cost than TD-DFT; performance can depend on the reference state and level of excitation [25]. | Higher (often 5-50x) |

| MP2 | Wavefunction-Based: Applies second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory to account for electron correlation [26]. | More accurate than HF for non-covalent interactions and many closed-shell systems; often a good cost/accuracy trade-off [26]. | Fails for multireference systems; can overestimate dispersion; performance depends on system [26]. | Moderate (2-10x) |

| TD-DFT | Density-Based: Computes excited states by linear response of the ground-state electron density. | Most common method for excited states; favorable cost/accuracy balance; applicable to large systems [25]. | Accuracy depends heavily on the functional; can fail for charge-transfer states, Rydberg states, and multireference systems [25]. | Low (1-3x) |

| CIS | Wavefunction-Based: Configuration Interaction with Single excitations from a Hartree-Fock reference. | Simple, inexpensive method for initial excited-state estimates; variational and size-consistent. | Neglects electron correlation; often overestimates excitation energies; inaccurate for quantitative work [23]. | Low (~1x) |

| ZINDO | Semi-Empirical: Approximates the Hartree-Fock equations using empirical parameters to fit experimental data. | Very fast; historically popular for spectroscopic properties of large molecules (e.g., organic chromophores). | Low accuracy due to approximations; limited transferability; largely superseded by more robust ab initio methods. | Minimal (0.001x) |

Workflow for Reaction Pathway Exploration

Selecting a method is only one part of a broader computational workflow for discovering and characterizing reaction pathways. The diagram below outlines a general strategy that incorporates these methods.

Workflow Description: Modern pathway exploration often uses a multi-level approach. Efficient, lower-level methods like semi-empirical GFN-xTB or DFT are used for initial pathway screening and transition state search (as in the IACTA or Dandelion workflows) [27] [28]. The geometries and pathways discovered are then refined using a higher-level method chosen based on the system's electronic structure. Finally, even higher-level single-point energy calculations (e.g., using composite methods like G3X or DLPNO-CCSD(T)) can be performed on the optimized structures for final validation and accurate barrier heights [26].

Benchmarking Studies and Experimental Data

Case Study 1: Oxidative Addition of SO₂ by OH Radical

This key atmospheric reaction tests a method's ability to locate a subtle transition state.

- Experimental Reference: Experimental enthalpy of reaction is -113.3 ± 6 kJ mol⁻¹ at 298 K [26].

- Computational Protocols:

- Geometries: Optimized using UMP2 (for OH and HOSO₂) and RMP2 (for SO₂) with the 6-31++G(2df,2p) basis set [26].

- Frequency Analysis: Calculated at the same level to confirm stationary points and obtain thermochemistry [26].

- Single-Point Energies: For higher accuracy, QCISD(T) single-point calculations were performed on MP2-optimized structures [26].

- Performance Data:

| Method | Basis Set | Barrier Height (kJ mol⁻¹) | Reaction Enthalpy (kJ mol⁻¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2=Full | 6-31++G(2df,2p) | 4.9 | -110.8 | Located a true transition state [26]. |

| B3LYP | 6-31++G(2df,2p) | Barrierless | -111.2 | Failed to locate a true transition state [26]. |

| QCISD(T)//MP2 | 6-311+G(2df,2p) | ~2.0 | - | Barrier height close to experimental suggestion [26]. |

| G3X//B3LYP | - | 0.5 | -109.3 | Very low barrier located [26]. |

Conclusion: MP2-based methods were successful in locating a transition state for this reaction, whereas B3LYP predicted a barrierless pathway. Higher-level corrections (e.g., QCISD(T) or G3X) are crucial for obtaining accurate barrier heights [26].

Case Study 2: Excited State Potential Energy Surfaces

The performance of excited-state methods was benchmarked for an excited-state proton transfer reaction.

- Computational Protocols:

- Reference Method: SAC-CI was used to generate benchmark potential energy surfaces [25].

- Comparison Method: Multiple TD-DFT functionals from different families (e.g., global hybrids) were tested [25].

- Solvation: Calculations were performed in both the gas phase and toluene (modeled as a polarizable continuum) [25].

- Key Finding: The study found that for excited states with varying polarity along the reaction path, TD-DFT's performance was highly functional-dependent. A "subtle compensation" between the functional's intrinsic error and solvent stabilization was needed for global hybrids with low exact exchange to correctly describe the reaction [25]. SAC-CI provided a more robust reference.

Case Study 3: Dataset Construction for Machine Learning

The creation of the Halo8 dataset highlights method selection for large-scale data generation.

- Goal: Generate ~20 million quantum chemical calculations for reaction pathways involving halogens to train machine learning interatomic potentials [27].

- Method Selected: ωB97X-3c [27].

- Benchmarking Result: On the DIET test set, ωB97X-3c achieved a weighted mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.2 kcal/mol, comparable to quadruple-zeta quality methods. In contrast, ωB97X/6-31G(d) showed an unacceptably high MAE of 15.2 kcal/mol [27].

- Rationale: ωB97X-3c was chosen as the optimal compromise between accuracy and computational cost, providing high accuracy for halogen-containing systems at a manageable cost for a dataset of this scale [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

The table below lists key software and computational models used in modern reaction pathway studies.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Reaction Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Dandelion Pipeline [27] | Computational Workflow | Automates reaction discovery and characterization (e.g., product search via SE-GSM, pathway refinement with NEB) using a multi-level (xTB/DFT) approach [27]. |

| IACTA (Imposed Activation) [28] | Exploration Method | Guides reaction discovery by activating a single user-selected coordinate (e.g., a bond length) combined with constrained conformer search [28]. |

| Effective Fragment Potential (EFP) [29] | Solvation Model | Describes solute-solvent interactions using effective potentials for discrete solvent molecules, useful for modeling explicit solvent shells [29]. |

| COSMO | Solvation Model | A polarizable continuum model (PCM) that treats the solvent as a dielectric continuum, accounting for bulk solvation effects [29]. |

| ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Software | A widely used package for ab init and DFT calculations; used for the Halo8 dataset [27]. |

| GFN-xTB | Semi-Empirical Method | Used for fast geometry optimizations, conformational searching, and initial pathway screening in multi-level workflows [27] [28]. |

Method Selection Guide

- For Organic Ground-State Reactions with Dynamic Correlation: DFT (with a validated functional) or MP2 are standard choices. MP2 can be more reliable for non-covalent interactions but should be checked for systematic errors [26].

- For Reactions Involving Bond Breaking/Forming in Multireference Systems: CASSCF is essential. Its results can be improved with perturbation theory (e.g., CASPT2) to account for dynamic correlation [23].

- For Excited-State Reactions and Spectroscopy: TD-DFT is efficient for large systems but requires functional benchmarking. SAC-CI is a more accurate but costly alternative, especially for challenging electronic states [25].

- For High-Throughput Data Generation: Composite methods like ωB97X-3c offer an excellent balance of accuracy and speed for generating large datasets for MLIP training [27].

- For Initial Exploration and Screening: Fast semi-empirical methods like GFN-xTB or force fields are invaluable in automated workflows (e.g., IACTA) to narrow down potential pathways before refinement with higher-level methods [28].

No single method is universally superior. A hierarchical strategy, combining the speed of low-level methods for sampling with the accuracy of high-level methods for validation, is the most effective approach for navigating the complex landscape of chemical reaction pathways.

In computational chemistry, a transition state (TS) is a first-order saddle point on the potential energy surface (PES)—the highest energy point on the minimum energy pathway (MEP) connecting reactant and product states [13]. The accurate location of transition states is fundamental to predicting reaction rates and understanding chemical mechanisms, as the energy barrier exponentially influences the reaction kinetics via the Eyring equation [30]. However, unlike local minima, saddle points are inherently more challenging to locate, requiring specialized optimization techniques that can navigate the complex, high-dimensional PES [31].

Transition state optimization methods can be broadly classified into single-ended and double-ended algorithms [32]. Single-ended methods, such as quasi-Newton and coordinate driving (or dimer methods), require only a single initial guess structure and explore the PES locally. In contrast, double-ended methods, including various interpolation approaches, utilize the known geometries of both reactants and products to constrain the search for the connecting saddle point [13] [32]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these dominant methodological families—quasi-Newton, coordinate driving, and interpolation approaches—focusing on their theoretical foundations, practical performance, and applicability in modern research settings, including drug development.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary classes of transition state optimization methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Transition State Optimization Methods

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Features | Computational Cost | Convergence Reliability | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpolation Methods | Linear Synchronous Transit (LST), Quadratic Synchronous Transit (QST), Nudged Elastic Band (NEB), Freezing String Method (FSM) | Uses reactant and product structures to define an initial path; optimizes nodes to find the MEP and TS [31] [13]. | High (scales with the number of nodes/images) [13] | Moderate to High (highly dependent on initial path quality) [31] | Reactions with known endpoints; complex paths with intermediates; automated workflows [31] [32]. |

| Quasi-Newton Methods | Partitioned Rational Function Optimization (P-RFO), BFGS-based updates (e.g., TS-BFGS) | Requires an initial TS guess and Hessian; uses iterative Hessian updates to converge on the saddle point [31] [30]. | Low to Moderate (avoids frequent Hessian calculation) [30] | High (with a good initial guess and Hessian) [31] | Well-understood reactions with a reasonable TS guess; often used as a final refinement step [31]. |

| Coordinate Driving (Dimer) Methods | Dimer Method, Improved Dimer Method | Locates saddle points by following low-curvature modes; requires only gradient evaluations, not the full Hessian [31] [13]. | Moderate (requires multiple gradient calculations per step) [31] | Moderate (can be misled by multiple low-energy modes) [13] | Large systems where Hessian is prohibitive; when the initial guess is poor and the reaction coordinate is unknown [31] [32]. |

Interpolation Approaches

Interpolation methods construct a series of structures (a "string" or "band") between reactants and products. The Freezing String Method (FSM) is an advanced interpolation algorithm implemented in Q-Chem. It starts with two string fragments representing the reactant and product, which are "grown" until they join, forming a complete reaction path [31]. Key parameters controlling its performance include FSM_NNODE (number of nodes, typically 10-20), FSM_NGRAD (number of perpendicular gradient steps per node, usually 2-6), and FSM_MODE (preferably LST interpolation) [31]. The highest-energy node on the final string provides an excellent guess for subsequent transition state optimization.

The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method and its variant, Climbing-Image NEB (CI-NEB), are other widely used double-ended methods. In standard NEB, multiple images are connected by spring forces and optimized simultaneously, but only the force component perpendicular to the path is used to push images toward the MEP ("nudging") [13]. CI-NEB enhances this by converting the highest-energy image into a TS optimizer—it climbs upwards along the tangent to the path while minimizing in all other directions, directly locating the saddle point [13].

Quasi-Newton Methods

Quasi-Newton methods, such as Partitioned Rational Function Optimization (P-RFO), are local surface-walking algorithms ideal for refining a good initial guess into an exact transition state [31]. Their primary advantage is avoiding the expensive calculation of the exact Hessian at every step. Instead, they begin with an initial Hessian estimate and update it iteratively using gradient information from subsequent steps (e.g., via the BFGS or SR1 update schemes) [30].

The performance of these methods is critically dependent on the quality of the initial guess and the initial Hessian. A poor initial Hessian can lead to slow convergence or convergence to the wrong saddle point. A powerful hybrid workflow combines the robustness of a double-ended method with the efficiency of a quasi-Newton method: the FSM provides a high-quality TS guess and an approximate Hessian (derived from the path tangent), which is then fed into a P-RFO calculation for final, precise optimization [31]. This "Hessian-free" approach can successfully locate transition states without performing a single exact Hessian calculation.

Coordinate Driving and the Dimer Method

The Dimer Method is a single-ended algorithm that locates saddle points by following reaction channels without requiring a pre-computed Hessian [31] [13]. It estimates the local curvature by using a pair of geometries (a "dimer") separated by a small distance. The method involves two key steps: rotating the dimer to find the direction of lowest curvature and then moving the dimer uphill along this direction [13]. This process is repeated until a saddle point is reached.

This method is particularly valuable for large systems where calculating the full Hessian is computationally prohibitive. It is also more robust than naive coordinate-following when the initial guess is poor and the reaction coordinate is not aligned with a simple vibrational mode [13]. However, it can struggle in systems with many low-frequency modes, as it may get lost on the complex PES [13].

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the real-world performance of different optimization algorithms. The following table synthesizes performance data from evaluations of various methods and software implementations.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Optimization Methods

| Method / Software | Test System | Success Rate | Average Steps to Convergence | Key Performance Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NewtonNet (ML Hessian) | 240 Organic Reactions | High (Robust) | 2-3x fewer than QN methods | Full analytical Hessians at every step; less reliant on initial guess. | [30] |

| Sella (Internal Coords) | 25 Drug-like Molecules (with OMol25 eSEN NNP) | 25/25 | ~15 | Efficient for transition state searches on neural network potentials. | [33] |

| L-BFGS | 25 Drug-like Molecules (with AIMNet2 NNP) | 25/25 | ~1.2 | Very fast convergence for local minima optimization on smooth PES. | [33] |

| geomeTRIC (TRIC) | 25 Drug-like Molecules (with GFN2-xTB) | 25/25 | ~103.5 | Reliable convergence using translation-rotation internal coordinates. | [33] |

| Quasi-Newton (DFT) | General Organic Reactions | Moderate | Baseline | Performance heavily dependent on initial Hessian guess quality. | [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Freezing String Method (FSM) with Subsequent P-RFO Refinement

This is a robust, two-step protocol for locating transition states when reactant and product geometries are known [31].

- FSM Setup: In the

$moleculesection of a Q-Chem input file, provide the optimized geometries of the reactant and product, separated by. The order of atoms must be consistent. - FSM $rem Settings: Set

JOBTYPE = fsm. Key parameters include:METHODandBASIS: Define the level of theory (e.g.,b3lyp/6-31g).FSM_NNODE = 18: A higher number of nodes is recommended for subsequent TS search.FSM_NGRAD = 3: Typically sufficient for most reaction paths.FSM_MODE = 2: Selects LST interpolation.FSM_OPT_MODE = 2: Uses the more efficient quasi-Newton optimizer.

- FSM Execution: The calculation outputs a

stringfile.txtcontaining the energy and geometry of each node. The highest-energy node is the TS guess. - P-RFO Refinement: A subsequent Q-Chem job is set up with

JOBTYPE = ts. The$moleculesection reads the guess geometry (read), and critical$remvariables includeGEOM_OPT_HESSIAN = read(to use the approximate Hessian from FSM) andSCF_GUESS = read[31].

Protocol 2: Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) Workflow

NEB is a standard method for mapping reaction pathways and providing TS guesses [13] [32].

- Endpoint Optimization: Fully optimize the reactant and product structures.

- Image Generation: Generate initial guesses for a series of images (typically 5-20) between the endpoints via linear interpolation.

- NEB Calculation: Run an NEB calculation where all images are optimized simultaneously. The key is to "nudge" the forces: only the component of the true force perpendicular to the path and the component of the spring force parallel to the path are used. This keeps images equally spaced while on the MEP.

- TS Identification: Upon convergence, the image with the highest energy is a good approximation of the TS. For greater accuracy, use the Climbing-Image (CI-NEB) variant, where this image is allowed to climb upwards along the path to the saddle point without being constrained by springs [13].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a hybrid computational workflow that integrates interpolation and quasi-Newton methods for robust transition state location, as described in the experimental protocols.

Hybrid TS Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Transition State Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Chem | Quantum Chemistry Software | Performs ab initio calculations and geometry optimizations. | FSM, P-RFO, Dimer Method [31] |

| Sella | Geometry Optimization Library | Specialized optimizer for minima and transition states. | Internal coordinate TS optimization [33] |

| geomeTRIC | Geometry Optimization Library | General-purpose optimizer with advanced internal coordinates. | L-BFGS with TRIC coordinates [33] |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Python Library | Atomistic simulations and integrations. | NEB, L-BFGS, FIRE optimizers [33] |

| NewtonNet | Differentiable Neural Network Potential | Machine-learned potential with analytical Hessians. | Full-Hessian TS optimization [30] |

| Transition-1X (T1x) | Dataset | Benchmark dataset of organic reaction pathways. | Training and validating ML models [30] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that no single transition state optimization method is universally superior. The choice of algorithm depends heavily on the specific problem, available computational resources, and prior knowledge of the reaction. Interpolation methods like FSM and NEB are powerful for exploratory studies where reactant and product structures are known, while quasi-Newton methods excel at the rapid refinement of good initial guesses. The Dimer method offers a compelling alternative for large systems or when Hessian information is unavailable.

A prominent trend is the move towards hybrid strategies that leverage the strengths of multiple approaches, such as using FSM to generate a high-quality guess and an approximate Hessian for a subsequent, highly efficient P-RFO search [31]. Furthermore, the field is being transformed by machine learning. The development of fully differentiable neural network potentials like NewtonNet, which can provide analytical Hessians at a fraction of the cost of DFT, promises to make robust, second-order TS optimization routines the new standard, drastically reducing the number of steps and reliance on expert intuition [30]. As these ML-based methods mature and are integrated into commercial and open-source software, they will significantly accelerate research in catalyst design, drug discovery, and materials science.

Hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) methodologies represent a cornerstone approach in computational chemistry and biology, enabling researchers to overcome the fundamental limitations of applying a full quantum mechanical treatment to extensive biomolecular systems. The inception of this multiscale concept can be traced to the visionary work of Arieh Warshel and Michael Levitt in their seminal study of enzymatic reactions, and it has since evolved into an indispensable tool for studying chemical reactivity in complex biological environments [34]. The core strength of QM/MM approaches lies in their strategic partitioning of the system: a chemically active region (where bond breaking/formation occurs) is treated with quantum mechanical accuracy, while the surrounding environment is modeled using computationally efficient molecular mechanics force fields [35] [36]. This dual-resolution strategy allows researchers to simulate systems comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms while maintaining quantum accuracy where it matters most, effectively bridging the gap between electronic structure details and biological complexity.

The recognition of QM/MM's transformative impact was underscored when Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2013 for "the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems" [36]. Today, QM/MM simulations have become a versatile tool applied to diverse challenges including enzymatic reaction mechanisms, ligand-protein interactions, crystal structure refinement, and the analysis of spectroscopic properties [37]. As the field progresses, these methods continue to evolve with enhancements in sampling algorithms, incorporation of polarizable force fields, and integration with machine learning approaches, pushing the boundaries of what can be simulated with atomic precision.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of QM Methods in QM/MM

Accuracy Benchmarking for Hydration Free Energies

Evaluating the performance of different quantum mechanical methods within QM/MM frameworks requires careful benchmarking against experimental observables. Hydration free energy (ΔGhyd) calculations provide a rigorous test case, as they quantify the free energy change of transferring a solute from gas phase to aqueous solution and are sensitive to the description of solute-solvent interactions [38]. A comprehensive study compared the performance of various QM methods when coupled with both fixed-charge and polarizable MM force fields for computing hydration free energies of twelve simple solutes [38].

Table 1: Performance of QM Methods in QM/MM Hydration Free Energy Calculations

| QM Method | MM Environment | Performance vs. Classical MM | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP2 | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| Hartree-Fock | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| BLYP | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| B3LYP | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| M06-2X | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| OM2 | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| AM1 | Fixed Charge | Inferior to classical | - |

| MP2 | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| Hartree-Fock | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| BLYP | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| B3LYP | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| M06-2X | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| OM2 | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

| AM1 | Drude Polarizable | Marginally better than fixed charge | - |

The results revealed a significant finding: across all tested QM methods, the QM/MM hydration free energies were inferior to purely classical molecular mechanics results [38]. Furthermore, the polarizable Drude force field provided only marginal improvements over fixed-charge models in QM/MM simulations [38]. This underscores a critical challenge in QM/MM implementations: the need for balanced interactions between the quantum and classical regions. The highly divergent results across different QM methods, with almost inverted trends for polarizable and fixed charge water models, highlight the importance of careful parameter matching between QM and MM components to avoid artifacts from biased solute-solvent interactions [38].

Method Selection for Reaction Pathway Prediction

Beyond hydration energies, the accuracy of QM methods is particularly crucial for predicting chemical reaction pathways. Recent advances have introduced physically-constrained generative AI approaches like FlowER (Flow matching for Electron Redistribution), which explicitly conserves atoms and electrons using a bond-electron matrix representation [22]. This method demonstrates how incorporating fundamental physical principles can enhance prediction reliability compared to conventional approaches that may violate conservation laws.

For biomolecular applications, the selection of an appropriate QM method involves balancing several factors. Density Functional Theory (DFT) remains the most popular choice due to its favorable accuracy-to-cost ratio, especially for QM regions containing hundreds of atoms [37]. However, different functionals show varying performance: the ωB97X-3c composite method has emerged as an optimal compromise, achieving 5.2 kcal/mol accuracy on benchmark tests while being five times faster than quadruple-zeta quality calculations [19]. This level of accuracy is essential for modeling halogen-containing systems prevalent in pharmaceutical compounds, where approximately 25% of small-molecule drugs contain fluorine [19].

Table 2: Accuracy and Efficiency Comparison of QM Methods for Reaction Pathways

| Method | Basis Set | Weighted MAE (kcal/mol) | Relative Computational Cost | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ωB97X-3c | Specially optimized | 5.2 | 1× (Reference) | General organic molecules, halogen-containing systems |

| ωB97X | 6-31G(d) | 15.2 | ~0.5× | Limited to elements with basis set parameters |

| ωB97X-D4 | def2-QZVPPD | 4.5 | 5× | High-accuracy reference calculations |

| DFTB3 | - | Varies | ~0.1× | Initial sampling, large QM regions |

| xTB | - | Varies | ~0.01× | Geometry optimization, initial pathway exploration |

Methodological Approaches and Embedding Schemes

QM/MM Implementation Frameworks

QM/MM methodologies can be implemented through different schemes, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The two primary approaches are subtractive and additive schemes [37]. In subtractive schemes (exemplified by ONIOM), three separate calculations are performed: (1) a QM calculation on the QM region, (2) an MM calculation on the entire system, and (3) an MM calculation on the QM region [37]. The total energy is then computed as E(QM/MM) = EQM(QM) + EMM(Full) - E_MM(QM). This approach ensures no double-counting of interactions and can be implemented with standard QM and MM software without code modifications [37].