Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Guide to Predictive Model Performance Metrics for Drug Development

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for evaluating predictive model performance.

Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Guide to Predictive Model Performance Metrics for Drug Development

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for evaluating predictive model performance. It covers foundational metrics, methodological application for clinical data, advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and robust validation and comparative analysis strategies. The content is tailored to address the unique challenges in biomedical research, such as handling imbalanced data for rare diseases and meeting regulatory requirements for transparent and reliable model reporting.

Core Principles: Understanding the Essential Metrics for Model Evaluation

The Critical Role of Evaluation Metrics in Robust Model Development

The development of predictive models in machine learning operates on a constructive feedback principle where models are built, evaluated using metrics, and improved iteratively until desired performance is achieved [1]. Evaluation metrics are not merely performance indicators but form the fundamental basis for discriminating between model results and making critical decisions about model deployment [1]. Within the context of predictive model performance metrics research, this whitepaper establishes that proper metric selection and interpretation constitute a scientific discipline in itself, particularly for high-stakes fields like pharmaceutical development and drug discovery.

The performance of machine learning models is fundamentally governed by their ability to generalize to unseen data [1] [2]. As noted in analytical literature, "The ground truth is building a predictive model is not your motive. It's about creating and selecting a model which gives a high accuracy score on out-of-sample data" [1]. This principle underscores why a systematic approach to model evaluation—rather than ad-hoc metric selection—proves essential for research integrity and practical application in scientific domains.

Classification of Evaluation Metrics

Evaluation metrics are broadly categorized based on model output type (classification vs. regression) and the specific aspect of performance being measured [1] [3]. Understanding these categories enables researchers to select metrics aligned with their model's operational context and the cost of potential errors.

Core Classification Metrics

Table 1: Fundamental Classification Metrics and Their Applications

| Metric | Formula | Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) [3] | Balanced datasets, equal error costs | Simple, intuitive interpretation | Misleading with class imbalance [2] |

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP) [3] | When false positives are costly (e.g., spam filtering) | Measures prediction quality | Does not account for false negatives |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP+FN) [3] | When false negatives are critical (e.g., medical diagnosis) | Identifies true positive coverage | Does not penalize false positives |

| F1-Score | 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall) [1] [3] | Imbalanced datasets, need for balance | Harmonic mean balances both concerns | May oversimplify in complex trade-offs |

| AUC-ROC | Area under ROC curve [2] | Model discrimination ability at various thresholds | Threshold-independent, comprehensive | Can be optimistic with severe imbalance |

Beyond these core metrics, the confusion matrix serves as the foundational table that visualizes all four possible prediction outcomes (True Positives, True Negatives, False Positives, False Negatives), enabling calculation of numerous derived metrics [1] [3]. For pharmaceutical applications, understanding the confusion matrix proves particularly valuable when different types of classification errors carry significantly different consequences.

Advanced Classification Assessment

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) chart measures the degree of separation between positive and negative distributions, with values ranging from 0-100, where higher values indicate better separation [1]. Meanwhile, Gain and Lift charts provide rank-ordering capabilities essential for campaign targeting problems, indicating which population segments to prioritize for intervention [1].

Regression Metrics and Their Applications

Regression models require distinct evaluation metrics focused on the magnitude and distribution of prediction errors. Different regression metrics capture varying aspects of error behavior, with selection depending on the specific application context and error tolerance.

Table 2: Key Regression Metrics and Characteristics

| Metric | Formula | Sensitivity to Outliers | Interpretation | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | (1/n)×∑|yi-ŷi| [3] | Robust | Average error magnitude | When all errors are equally important |

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | (1/n)×∑(yi-ŷi)² [3] | High | Average squared error | When large errors are particularly undesirable |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | √MSE [3] | High | Error in original units | When units matter and large errors are critical |

| R-squared (R²) | 1 - (SSE/SST) [3] | Moderate | Proportion of variance explained | Model explanatory power |

| Adjusted R-squared | 1 - [(1-R²)(n-1)/(n-k-1)] | Moderate | Variance explained adjusted for predictors | Comparing models with different predictors |

Recent research in wastewater quality prediction—a domain with parallels to pharmaceutical process optimization—suggests that "error metrics based on absolute differences are more favorable than squared ones" in noisy environments [4]. This finding has significant implications for drug development applications where sensor data and experimental measurements often contain substantial inherent variability.

Experimental Design and Validation Protocols

Robust model evaluation requires methodological rigor in experimental design beyond mere metric calculation. Proper validation techniques ensure that reported performance metrics reflect true generalization capability rather than idiosyncrasies of the data partitioning.

Holdout Validation

The dataset is split into two parts: a training set for model development and a test set for final evaluation [3]. This approach provides an unbiased assessment of model performance on unseen data. For example, in predicting customer subscription cancellations, a streaming company might use data from 800 customers for training and reserve 200 completely separate customers for testing [3].

Cross-Validation Techniques

k-Fold Cross-Validation divides the dataset into k equal parts (folds), using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for testing, repeating this process k times [3]. A financial institution predicting loan defaults might implement 5-fold cross-validation, ensuring the model's performance consistency across different data subsets [3]. The final performance is averaged across all folds:

Average Performance = (1/K) × ∑(Performance on Fold_i) [2]

For imbalanced datasets common in pharmaceutical applications (such as rare adverse event prediction), stratified cross-validation maintains the class distribution比例 in each fold, preventing biased evaluation [2].

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

The bias-variance tradeoff represents a fundamental concept in model evaluation, balancing underfitting (high bias) against overfitting (high variance) [3]. Simple models with high bias fail to capture data patterns, while overly complex models with high variance fit training noise rather than underlying relationships [3]. Optimal model selection explicitly acknowledges and manages this tradeoff.

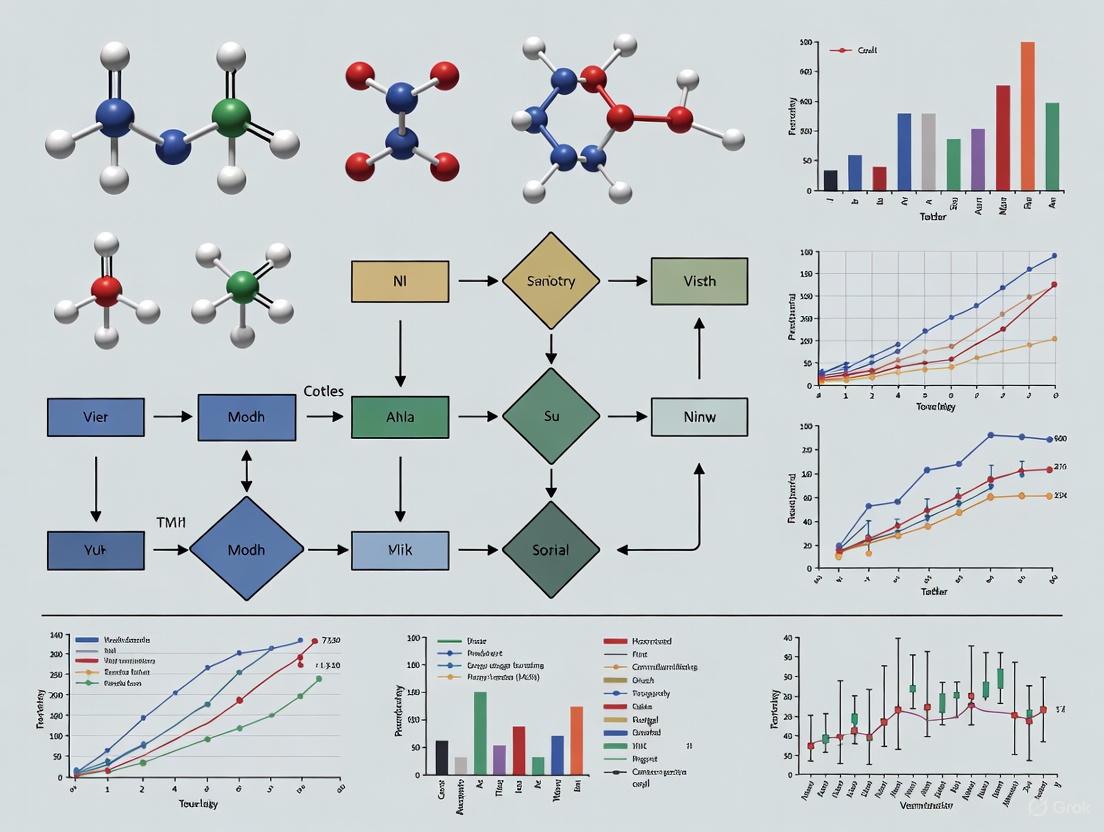

Methodological Workflows and Visualization

The process of model evaluation follows systematic workflows that ensure comprehensive assessment. The diagram below illustrates the integrated model validation workflow:

Integrated Model Validation Workflow

Selecting appropriate evaluation metrics requires understanding the research question and model objectives. The following diagram outlines the decision process for metric selection:

Metric Selection Decision Framework

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Model Evaluation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn Metrics Module | Provides implementation of key metrics [5] | General-purpose model evaluation |

| Strictly Consistent Scoring Functions | Aligns metric with target functional (e.g., mean, quantile) [5] | Probabilistic forecasting and decision making |

| Cross-Validation Implementations | k-Fold, Leave-One-Out, Stratified variants [3] | Robust performance estimation |

| Confusion Matrix Analysis | Detailed breakdown of classification results [1] [3] | Binary and multi-class classification |

| AUC-ROC Calculation | Threshold-agnostic model discrimination assessment [1] [2] | Classification model selection |

| Multiple Metric Evaluation | Simultaneous assessment of different performance aspects [2] | Comprehensive model validation |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The landscape of model evaluation continues to evolve with increasing sophistication in metric development and application. Current research indicates several emerging trends that will influence future predictive model assessment in scientific domains.

Metric Selection Frameworks

Research in specialized domains like wastewater treatment has led to the development of "practical, decision-guiding flowchart[s] to assist researchers in selecting appropriate evaluation metrics based on dataset characteristics, modeling objectives, and project constraints" [4]. Similar frameworks are increasingly necessary for pharmaceutical applications where regulatory compliance and model interpretability requirements impose additional constraints on metric selection.

Evaluation of Generative AI Models

As generative AI models become more prevalent in scientific discovery, including drug candidate generation and molecular design, traditional evaluation metrics prove insufficient [2]. These models require "a more nuanced approach" beyond conventional metrics, incorporating human evaluation, domain-specific benchmarks, and specialized quality assessments [2].

Continuous Performance Monitoring

The concept of model evaluation is expanding beyond pre-deployment assessment to include continuous monitoring in production environments [2]. This recognizes that "model performance can degrade over time as the underlying data distribution changes, a phenomenon known as data drift" [2]. For pharmaceutical applications with longitudinal data, establishing continuous evaluation protocols becomes essential for maintaining model validity throughout its lifecycle.

Evaluation metrics form the scientific foundation for robust model development in predictive analytics, particularly in high-stakes fields like pharmaceutical research and drug development. The selection of appropriate metrics must be guided by domain knowledge, error cost analysis, and operational requirements rather than convention or convenience. As the field advances, researchers must remain abreast of both theoretical developments in metric design and practical frameworks for comprehensive model assessment. The integration of rigorous evaluation protocols throughout the model lifecycle ensures that predictive models deliver reliable, actionable insights for scientific advancement and public health improvement.

Within the rigorous field of predictive modeling, the performance of a classification algorithm is paramount. For researchers and scientists, particularly in high-stakes domains like drug development, a model's output must be quantifiable, interpretable, and trustworthy. The confusion matrix serves as this fundamental diagnostic tool, providing a granular breakdown of a model's predictions versus actual outcomes and forming the basis for a suite of critical performance metrics [6] [7]. This technical guide deconstructs the confusion matrix into its core components—True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN)—and details the methodologies for deriving and interpreting key metrics essential for validating predictive models in scientific research.

Core Components of the Confusion Matrix

A confusion matrix is a specific table layout that allows for the visualization of a classification model's performance [7]. It compares the actual target values with those predicted by the machine learning model, creating a structured overview of its successes and failures.

The foundational structure for a binary classification problem is a 2x2 matrix, with rows representing the actual class and columns representing the predicted class [6] [8]. The four resulting quadrants are defined as follows:

- True Positive (TP): The model correctly predicts the positive class. In a medical context, this represents a patient with a disease who is correctly identified as having it [6] [9].

- True Negative (TN): The model correctly predicts the negative class. This represents a healthy patient correctly identified as not having the disease [6] [9].

- False Positive (FP): The model incorrectly predicts the positive class when the actual value is negative. Also known as a Type I error, this is a false alarm [6] [7]. For example, a diagnostic test incorrectly indicating that a healthy person has a disease [6].

- False Negative (FN): The model incorrectly predicts the negative class when the actual value is positive. Also known as a Type II error, this represents a missed detection [6] [7]. For example, a test failing to identify a sick person as having the disease [6].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these components and the process of creating a confusion matrix.

Metrics Derived from the Confusion Matrix

The raw counts of TP, TN, FP, and FN are used to calculate a suite of performance metrics, each offering a different perspective on model behavior [6] [7]. The choice of metric is critical and depends on the specific research objective and the cost associated with different types of errors.

Comprehensive Metric Formulae

The table below summarizes the key metrics derived from the confusion matrix, their formulas, and their core interpretation.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics Derived from the Confusion Matrix

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) [6] [10] | The overall proportion of correct predictions among the total predictions. |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) [6] [10] | The proportion of correctly identified positives among all instances predicted as positive. Measures the model's reliability when it predicts the positive class. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP / (TP + FN) [6] [10] | The proportion of actual positive cases that were correctly identified. Measures the model's ability to find all relevant positive cases. |

| Specificity | TN / (TN + FP) [6] | The proportion of actual negative cases that were correctly identified. |

| F1-Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) [6] [10] | The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both concerns. |

| False Positive Rate (FPR) | FP / (FP + TN) [10] | The proportion of actual negatives that were incorrectly classified as positive. Equal to 1 - Specificity. |

The Precision-Recall Trade-Off and Metric Selection

Precision and recall often have an inverse relationship; increasing one may decrease the other [10]. The F1-score is a single metric that balances this trade-off, but the choice to prioritize precision or recall is domain-specific.

- High-Recall Scenarios: Essential in contexts where the cost of missing a positive case is high. In medical diagnostics (e.g., cancer screening or identifying patients for drug trials), a false negative (missing a disease) is far more dangerous than a false positive (which can be ruled out by further tests) [10] [11]. Therefore, maximizing recall is the priority.

- High-Precision Scenarios: Critical when the cost of a false positive is high. For example, in spam email detection, incorrectly labeling a legitimate email as spam (false positive) is more problematic than letting a single spam email through (false negative) [6] [10].

- The Pitfall of Accuracy: For imbalanced datasets, where one class significantly outnumbers the other, accuracy can be a misleading metric [9] [10]. A model that simply predicts the majority class for all instances can achieve high accuracy while being useless for identifying the critical minority class (e.g., a rare disease).

Experimental Protocol for Model Evaluation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for evaluating a classification model and constructing its confusion matrix, using a publicly available clinical dataset as an example.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Tools and Software for Model Evaluation

| Item | Function | Example / Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Dataset | Serves as the ground truth for training and evaluating the model. Requires expert annotation. | The Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset [11] [8]. |

| Programming Language | Provides the environment for data manipulation, model training, and evaluation. | Python, with its extensive data science ecosystem (e.g., scikit-learn, pandas, NumPy) [6] [11]. |

| Computational Library | Offers pre-implemented functions for metrics calculation and matrix visualization. | Scikit-learn's metrics module (confusion_matrix, classification_report) [6] [11]. |

| Visualization Library | Enables the creation of clear, interpretable plots of the confusion matrix. | Seaborn and Matplotlib for generating heatmaps [6] [11]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram outlines the end-to-end experimental workflow for training a model and evaluating its performance using a confusion matrix.

1. Data Preparation and Model Training: A common dataset used in medical ML research is the Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset, which contains features computed from digitized images of fine-needle aspirates of breast masses, with the target variable being diagnosis (malignant or benign) [11] [8]. The dataset is first split into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a held-out test set (e.g., 20-30%) to ensure an unbiased evaluation [8]. A classification model, such as Logistic Regression or Support Vector Machine (SVM), is then trained on the training set [11] [8].

2. Prediction and Matrix Construction:

The trained model is used to predict labels for the test set. These predictions are compared against the ground truth labels. Using a function like confusion_matrix from scikit-learn, the counts for TP, TN, FP, and FN are computed [6].

Example Python Snippet:

3. Metric Derivation and Visualization: The counts from the confusion matrix are used to calculate the metrics outlined in Table 1. The matrix is best visualized as a heatmap to facilitate immediate interpretation.

Example Python Snippet for Visualization:

4. Threshold Tuning: The default threshold for classification is often 0.5. However, this threshold can be adjusted to better align with research goals [12] [11]. Lowering the classification threshold makes it easier to predict the positive class, which typically increases Recall (fewer false negatives) but decreases Precision (more false positives). Conversely, raising the threshold increases Precision but decreases Recall [11]. The optimal threshold is determined by analyzing metrics across a range of values, for instance, using ROC or Precision-Recall curves [12].

The confusion matrix is an indispensable, foundational tool in the evaluation of predictive models. Its components—TP, TN, FP, and FN—provide the raw data from which critical metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score are derived. For researchers in drug development and other scientific fields, a nuanced understanding of these metrics and the trade-offs between them is non-negotiable. It allows for the rigorous selection and deployment of models whose performance characteristics are aligned with the high-stakes costs of real-world decision-making, where a false negative or false positive can have significant consequences. Proper evaluation, as outlined in this guide, ensures that predictive models are not just mathematically sound but are also fit for their intended purpose.

In the rigorous field of predictive model performance metrics research, selecting appropriate evaluation criteria is paramount to validating a model's real-world utility. This is especially critical in high-stakes domains like drug development, where model performance directly impacts patient safety and therapeutic efficacy [13]. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score provide a multifaceted view of model behavior, each illuminating a different aspect of performance. Their definitions, interrelationships, and the trade-offs they represent form the foundation of robust model evaluation [10] [14]. This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of these core metrics, framing them within the specific context of pharmaceutical research and development to aid scientists and professionals in making informed, evidence-based decisions about their predictive models.

Core Metric Definitions and Mathematical Formulations

The evaluation of binary classification models is fundamentally based on four outcomes derived from the confusion matrix: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) [1] [15]. These outcomes represent the simplest agreement or disagreement between model predictions and actual values.

The Confusion Matrix: A Foundational Tool

The confusion matrix is a 2x2 table that provides a detailed breakdown of a model's predictions against actual outcomes [14]. It is the cornerstone for calculating all subsequent metrics and is indispensable for diagnosing specific error patterns.

- True Positive (TP): The model correctly predicts the positive class. In drug discovery, this represents correctly identifying a compound that truly has a therapeutic effect [14].

- True Negative (TN): The model correctly predicts the negative class. For example, correctly identifying a drug candidate that does not cause a specific adverse reaction [15].

- False Positive (FP) (Type I Error): The model incorrectly predicts the positive class. This is a "false alarm," such as wrongly flagging a safe drug as potentially causing a severe side effect [10] [14].

- False Negative (FN) (Type II Error): The model incorrectly predicts the negative class. This is a "miss," such as failing to identify a drug that actually causes an adverse reaction, a critical error in pharmacovigilance [10] [14].

Derivation of Primary Metrics

From these four building blocks, the primary evaluation metrics are derived. The formulas below provide a quantitative framework for assessment.

Accuracy

Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model across both positive and negative classes [10] [15].

Formula:

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) [10]

Precision

Precision, also known as Positive Predictive Value (PPV), measures the reliability of a model's positive predictions [10] [14]. It answers the question: "When the model predicts positive, how often is it correct?"

Formula:

Precision = TP / (TP + FP) [10]

Recall

Recall, also known as Sensitivity or True Positive Rate (TPR), measures a model's ability to identify all relevant positive instances [10] [14]. It answers the question: "Of all the actual positives, how many did the model successfully find?"

Formula:

Recall = TP / (TP + FN) [10]

F1-Score

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both concerns [10] [16]. It is particularly useful when a balanced view of both false positives and false negatives is needed.

Formula:

F1 = 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) = 2TP / (2TP + FP + FN) [10] [16]

Table 1: Summary of Core Evaluation Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) | Overall correctness of the model | All predictions |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) | Correctness when it predicts positive | False Positives (Type I Error) |

| Recall | TP / (TP + FN) | Ability to find all positive instances | False Negatives (Type II Error) |

| F1-Score | 2TP / (2TP + FP + FN) | Balanced mean of precision and recall | Both FP and FN |

The Critical Role of Class Balance and Metric Selection

The distribution of classes in a dataset—whether it is balanced or imbalanced—profoundly influences the interpretation and choice of these metrics [10] [15].

The Accuracy Paradox in Imbalanced Data

Accuracy can be a dangerously misleading metric when dealing with imbalanced datasets, which are common in healthcare and drug safety applications [15]. For instance, if only 1% of patients in a study experience a serious adverse drug reaction (ADR), a model that simply predicts "no ADR" for every patient would achieve 99% accuracy, despite being entirely useless for the task of identifying the critical positive cases [10] [15]. This phenomenon is known as the accuracy paradox [15].

Strategic Metric Selection for Drug Development

The choice of which metric to prioritize is not a purely technical decision; it must be guided by the specific clinical or research context and the cost associated with different types of errors [10] [13].

Table 2: Metric Selection Guide for Pharmaceutical Use Cases

| Use Case Scenario | Primary Metric | Rationale and Cost-Benefit Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Early-stage drug safety screening [13] | High Recall | Goal: Identify all potential ADRs.Cost of FN: Catastrophic. A missed toxic compound progresses, risking patient harm and costly late-stage trial failures.Cost of FP: Manageable. A safe compound flagged for further review incurs minor additional testing cost. |

| Validating a diagnostic assay | High Precision | Goal: Ensure positive test results are reliable.Cost of FP: High. A false diagnosis leads to patient anxiety, unnecessary confirmatory tests, and potential for incorrect treatment.Cost of FN: Lower but still important. A missed case may be caught through subsequent testing. |

| Post-market pharmacovigilance [17] | F1-Score | Goal: Balance the detection of true ADR signals with the operational cost of investigating false alerts.Context: Requires a balance; too many FPs overwhelm resources, while too many FNs mean missing safety signals. |

| Balanced dataset (e.g., drug-target interaction) [18] | Accuracy (with other metrics) | Goal: General model correctness.Context: When both classes are equally represented and important, accuracy provides a valid coarse-grained performance indicator. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

To illustrate the practical application of these metrics, consider a typical experimental protocol for evaluating a model designed to predict adverse drug reactions (ADRs) from clinical trial data [17].

Experimental Workflow for ADR Prediction

The following diagram outlines a standardized methodology for building and evaluating a predictive model in this context.

Benchmarking Model Performance

A study on AI-driven pharmacovigilance provides concrete results from such an evaluation, comparing multiple machine learning models [17]. The performance metrics offer a clear, quantitative basis for model selection.

Table 3: Model Performance Comparison for ADR Detection [17]

| Model | Reported Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression (Benchmark) | 78% | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| Support Vector Machine (Benchmark) | 80% | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 85% | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

Experimental Insight: The CNN model's superior accuracy suggests it is better at overall correct classification of ADRs versus non-ADRs [17]. However, for a full assessment, the precision and recall values are critical. A model with high accuracy but low recall would be unsuitable, as it would miss too many actual ADRs.

Another study on drug-target interactions reported an accuracy of 98.6% for their proposed CA-HACO-LF model, highlighting the high performance achievable on specific prediction tasks within drug discovery [18].

Advanced Considerations: The Precision-Recall Trade-Off and Fβ-Score

In practice, it is often impossible to simultaneously improve both precision and recall. This inherent tension is known as the precision-recall trade-off [10] [14].

Visualizing the Trade-Off

Adjusting the classification threshold of a model directly impacts this trade-off. A higher threshold makes the model more conservative, increasing precision but decreasing recall. A lower threshold makes the model more aggressive, increasing recall but decreasing precision [14]. This relationship is best visualized with a Precision-Recall (PR) curve.

The Fβ-Score: A Flexible Combined Metric

While the F1-score assigns equal weight to precision and recall, there are scenarios where one is more important than the other. The generalized Fβ-score allows for this flexibility [1] [16].

Formula:

Fβ = (1 + β²) * (Precision * Recall) / (β² * Precision + Recall) [16]

The β parameter controls the weighting:

β = 1: Equally weights precision and recall (standard F1-score).β > 1: Favors recall (e.g.,β=2for F2-score, recall is twice as important as precision).β < 1: Favors precision (e.g.,β=0.5, precision is twice as important as recall).

This is crucial in drug development. For a screening model to identify potentially toxic compounds, a high β value (e.g., 2) would be appropriate to heavily penalize false negatives. Conversely, for a final confirmatory test, a low β value might be chosen to ensure positive results are highly reliable and minimize false alarms [16].

Implementing and evaluating these metrics requires a suite of methodological and computational tools. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for scientists working in predictive model evaluation for drug development.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Technique | Function in Evaluation | Example Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Confusion Matrix [1] [14] | Foundational diagnostic tool visualizing TP, TN, FP, FN. | First-step analysis to understand the specific error profile of a model predicting drug-target interactions [18]. |

| Precision-Recall (PR) Curve [14] | Illustrates the trade-off between precision and recall across different classification thresholds. | Essential for evaluating models on imbalanced datasets, such as predicting rare but serious adverse drug reactions [17]. |

| Fβ-Score [16] | A single metric that allows for weighting precision vs. recall based on a specific β parameter. | Formally incorporates the relative cost of false positives vs. false negatives into model selection for a given clinical task. |

| Cosine Similarity & N-Grams [18] | Feature extraction techniques for textual or structural data to assess semantic and syntactic proximity. | Used to process and extract meaningful features from scientific literature or drug description datasets to improve context-aware models [18]. |

| Cross-Validation [1] | A resampling technique used to assess model generalizability and reduce overfitting. | Critical for providing a robust estimate of model performance (e.g., accuracy, F1) before deployment in clinical trial data analysis [1]. |

| Context-Aware Hybrid Models (e.g., CA-HACO-LF) [18] | Advanced models combining optimization algorithms with classifiers for improved prediction. | Used in state-of-the-art research to enhance the accuracy of predicting complex endpoints like drug-target interactions [18]. |

Within the broader context of predictive model performance metrics research, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under this Curve (AUC) stand as critical tools for evaluating binary classification models. These metrics are indispensable for assessing a model's discriminative power—its ability to separate positive and negative classes—across all possible classification thresholds. Unlike metrics such as accuracy, which provide a single-threshold snapshot, the AUC-ROC offers a comprehensive, threshold-independent evaluation, making it particularly valuable for imbalanced datasets common in medical research and drug development [19] [20]. This technical guide details the principles, interpretation, and methodological application of AUC-ROC, providing researchers with the framework necessary for robust model evaluation.

Core Concepts and Definitions

The ROC Curve

The ROC curve is a graphical plot that illustrates the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier system. It is created by plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) at various threshold settings [19] [21]. The curve visualizes the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, enabling researchers to select an optimal threshold based on the relative costs of false positives and false negatives in their specific application.

Underlying Metrics

The construction and interpretation of the ROC curve rely on fundamental classification metrics derived from the confusion matrix:

- True Positive Rate (TPR/Sensitivity/Recall): Proportion of actual positives correctly identified: ( TPR = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} ) [22] [23]

- False Positive Rate (FPR): Proportion of actual negatives incorrectly classified as positive: ( FPR = \frac{FP}{FP + TN} = 1 - Specificity ) [22] [23]

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): Proportion of actual negatives correctly identified: ( Specificity = \frac{TN}{TN + FP} ) [21] [24]

Table 1: Classification Metrics from Confusion Matrix

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity/Recall/TPR | ( \frac{TP}{TP + FN} ) | Ability to identify true positives |

| Specificity/TNR | ( \frac{TN}{TN + FP} ) | Ability to identify true negatives |

| False Positive Rate | ( \frac{FP}{FP + TN} ) | Proportion of false alarms |

| False Negative Rate | ( \frac{FN}{TP + FN} ) | Proportion of missed positives |

Area Under the Curve (AUC)

The AUC represents the probability that a randomly chosen positive example ranks higher than a randomly chosen negative example, based on the classifier's scoring function [19] [20]. This interpretation as a ranking metric is fundamental to understanding its value in model assessment. AUC values range from 0 to 1, where:

- AUC = 1.0: Perfect classifier that completely separates the classes

- AUC = 0.5: Classifier with no discriminative power (equivalent to random guessing)

- AUC < 0.5: Classifier performs worse than random guessing [19] [24]

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

In medical research and drug development, ROC analysis is extensively used to evaluate diagnostic tests, biomarkers, and predictive models. The curve helps determine the clinical utility of index tests—including serum markers, radiological imaging, or clinical decision rules—by quantifying their ability to distinguish between diseased and non-diseased individuals [21] [25].

Table 2: Clinical Interpretation Guidelines for AUC Values

| AUC Value | Diagnostic Performance | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| 0.9 - 1.0 | Excellent | High clinical utility |

| 0.8 - 0.9 | Considerable | Good clinical utility |

| 0.7 - 0.8 | Fair | Moderate clinical utility |

| 0.6 - 0.7 | Poor | Limited clinical utility |

| 0.5 - 0.6 | Fail | No clinical utility [25] |

When interpreting AUC values, researchers should always consider the 95% confidence interval. A narrow confidence interval indicates greater reliability of the AUC estimate, while a wide interval suggests uncertainty, potentially due to insufficient sample size [25].

Methodological Considerations

ROC Curve Types

ROC curves can be generated using different statistical approaches, each with distinct advantages:

- Nonparametric (Empirical) ROC Curves: Constructed directly from observed data without distributional assumptions. These curves typically have a jagged, staircase appearance but provide unbiased estimates of sensitivity and specificity [21].

- Parametric ROC Curves: Assume data follows a specific distribution (often normal). These produce smooth curves but may yield improper ROC curves if distributional assumptions are violated [21].

- Semiparametric ROC Curves: Combine elements of both approaches to overcome limitations of each method [21].

Table 3: Comparison of ROC Curve Methodologies

| Characteristic | Nonparametric | Parametric |

|---|---|---|

| Assumptions | No distributional assumptions | Assumes normal distribution |

| Curve Appearance | Jagged, staircase | Smooth |

| Data Usage | Uses all observed data | May discard actual data points |

| Computation | Simple | Complex |

| Bias Potential | Unbiased estimates | Possibly biased |

Optimal Cutoff Selection

While ROC analysis evaluates performance across all thresholds, practical application often requires selecting a single operating point. The Youden Index (( J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1 )) identifies the threshold that maximizes both sensitivity and specificity [25]. However, the optimal threshold ultimately depends on the clinical context and relative consequences of false positives versus false negatives [19] [21].

Performance Evaluation and Comparison with Other Metrics

Advantages of AUC-ROC

Research demonstrates that AUC provides the most consistent model evaluation across datasets with varying prevalence levels, maintaining stable performance when other metrics fluctuate significantly [20]. This stability arises because AUC evaluates the ranking capability of a model rather than its performance at a single threshold, making it particularly valuable for:

- Imbalanced datasets where positive and negative classes are unevenly distributed [20] [26]

- Threshold-independent evaluation of intrinsic model performance [20]

- Model comparison without presupposing a specific operating threshold [19] [20]

Limitations and Complementary Metrics

While powerful, AUC-ROC has limitations. In cases of extreme class imbalance, precision-recall curves may provide more meaningful evaluation [19] [22]. Additionally, AUC summarizes performance across all thresholds, which may include regions of little practical interest [20]. For comprehensive model assessment, researchers should consider AUC alongside metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score, particularly when the operational threshold is known.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

ROC Curve Generation Protocol

The following methodology details the process for generating and evaluating ROC curves:

- Model Training: Train binary classification model using standardized procedures

- Probability Prediction: Generate predicted probabilities for the positive class on validation data

- Threshold Selection: Define a series of classification thresholds (typically 0-1 in increments of 0.01)

- Performance Calculation: At each threshold, calculate TPR and FPR using the confusion matrix

- Curve Plotting: Graph TPR (y-axis) against FPR (x-axis) for all thresholds

- AUC Calculation: Compute the area under the plotted curve using numerical integration methods (e.g., trapezoidal rule) [22] [23]

Statistical Comparison of ROC Curves

When comparing two independent ROC curves, researchers can test for statistically significant differences in AUC using methods such as the DeLong test [25] [27]. This evaluation should consider both the magnitude of difference between AUC values and their associated confidence intervals to draw meaningful conclusions about comparative model performance.

Multiclass Classification Extension

For problems with more than two classes, the One-vs-Rest (OvR) approach extends ROC analysis by treating each class as the positive class once while grouping all others as negative [24]. This generates multiple ROC curves (one per class), with the macro-average AUC providing an overall performance measure.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for ROC Analysis in Research

| Tool/Category | Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python (scikit-learn), MedCalc, SPSS | Compute ROC curves, AUC, and confidence intervals |

| Programming Libraries | scikit-learn, pROC (R), statsmodels | Implement ROC analysis algorithms |

| Visualization Tools | matplotlib, ggplot2, seaborn | Generate publication-quality ROC curves |

| Statistical Tests | DeLong test, Hanley & McNeil method | Compare AUC values statistically |

Visualizations

ROC Curve Construction Logic

AUC Interpretation and Calculation

The AUC-ROC curve remains a fundamental tool for evaluating predictive model performance in research settings, particularly in medical science and drug development. Its capacity to measure discriminative power across all classification thresholds provides a comprehensive assessment of model quality that single-threshold metrics cannot match. While researchers should remain aware of its limitations—particularly in cases of extreme class imbalance—the AUC-ROC's consistency across varying prevalence levels and its intuitive interpretation as a ranking metric secure its position as an essential component of the model evaluation toolkit. Future work in predictive model performance metrics research should continue to refine ROC methodology while developing complementary approaches that address its limitations in specialized applications.

Gain, Lift, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) Charts for Model Selection

Within the rigorous framework of predictive model performance metrics research, selecting an optimal classification model extends beyond mere accuracy. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three pivotal diagnostic tools—Gain, Lift, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) charts—that empower researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate model efficacy based on probabilistic ranking and distributional separation. These metrics are particularly crucial in domains like pharmacovigilance and targeted therapy, where imbalanced data is prevalent and the cost of misclassification is high. By detailing their theoretical foundations, calculation methodologies, and interpretive protocols, this whitepaper establishes a standardized paradigm for model selection that prioritizes operational efficiency and robust discriminatory power.

The evaluation of predictive models in scientific research, particularly in drug development, necessitates metrics that align with strategic operational goals. While traditional metrics like accuracy and F1-score provide a snapshot of overall performance, they often fail to guide resource allocation efficiently [1] [2]. Gain, Lift, and K-S charts address this gap by focusing on the model's ability to rank-order instances by their probability of belonging to a target class, such as patients experiencing an adverse drug reaction or respondents to a specific treatment.

This approach is indispensable when dealing with imbalanced datasets, a common scenario in clinical trials and healthcare analytics, where the event of interest may be rare [28]. By quantifying the concentration of target events within top-ranked segments, these charts enable researchers to make data-driven decisions about where to apply a model's predictions for maximum impact, thereby optimizing experimental budgets and accelerating discovery cycles. This paper frames these tools within a broader thesis that advocates for context-sensitive, efficiency-oriented model evaluation.

Gain Chart: Quantifying Cumulative Model Effectiveness

Theoretical Foundation

A Gain Chart visualizes the effectiveness of a classification model by plotting the cumulative percentage of the target class captured against the cumulative percentage of the population sampled when sorted in descending order of predicted probability [28] [29]. Its core function is to answer the question: "If we target the top X% of a population based on the model's predictions, what percentage of all positive cases will we capture?" [30]. This makes it an invaluable tool for planning targeted interventions, such as identifying a sub-population for a high-cost therapeutic or selecting patients for a focused clinical study.

Construction Methodology

The construction of a Gain Chart follows a systematic protocol [28] [30]:

- Probability Prediction and Ranking: Use the model to assign a probability of being in the target class (e.g., "responder," "disease positive") to every instance in the validation dataset. Rank all instances from highest to lowest probability.

- Decile-Based Segmentation: Divide the ranked list into ten equal segments, or deciles (i.e., top 10%, next 10%, etc.).

- Cumulative Sum Calculation: For each decile, calculate the cumulative number of true positive instances (actual target class members) captured up to that point.

- Gain Calculation: The gain value for each decile is calculated as the ratio of the cumulative number of true positives up to that decile to the total number of true positives in the entire dataset [28].

- Plotting: The Gain Chart is plotted with the cumulative percentage of the population (deciles) on the X-axis and the cumulative percentage of true positives (Gain) on the Y-axis.

Table 1: Example Gain Chart Calculation for a Marketing Response Model (Total Positives = 3850)

| Decile | % Population | Number of Positives in Decile | Cumulative Positives | Gain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10% | 543 | 543 | 14.1% |

| 2 | 20% | 345 | 888 | 23.1% |

| 3 | 30% | 287 | 1175 | 30.5% |

| 4 | 40% | 222 | 1397 | 36.3% |

| 5 | 50% | 158 | 1555 | 40.4% |

| 6 | 60% | 127 | 1682 | 43.7% |

| 7 | 70% | 98 | 1780 | 46.2% |

| 8 | 80% | 75 | 1855 | 48.2% |

| 9 | 90% | 53 | 1908 | 49.6% |

| 10 | 100% | 42 | 1950 | 50.6% |

Interpretation and Analysis

The resulting chart features two key lines [29]:

- The Model Gain Curve: A curve that arches above the baseline. The steeper the initial ascent of this curve, the better the model is at concentrating positive cases at the top of the ranked list.

- The Baseline (Random Model): A diagonal line from (0,0) to (100,100), representing the expected performance if instances were selected randomly. For example, randomly selecting 20% of the population would be expected to capture 20% of the positive cases.

A superior model will show a gain curve that rises sharply towards the top-left corner. For instance, from Table 1, the model captures 36.3% of all positive cases by targeting only the top 40% of the population, a significant improvement over the 40% expected by random selection [30]. The point where the gain curve begins to flatten indicates the optimal operational cutoff for resource allocation.

Diagram 1: Workflow for constructing a Gain Chart

Lift Chart: Measuring Performance Improvement Over Random

Theoretical Foundation

While the Gain Chart shows cumulative coverage, the Lift Chart expresses the multiplicative improvement in target density achieved by using the model compared to a random selection [31] [29]. Lift answers the question: "How many times more likely are we to find a positive case by using the model compared to not using it?" A lift value of 3 at the top decile means the model is three times more effective than random selection in that segment. This metric is critical for communicating the tangible value and ROI of deploying a predictive model.

Construction Methodology

Lift is derived directly from the Gain Chart data [28] [30]:

- Calculate Cumulative Lift: For each decile, take the Gain value (the cumulative percentage of positives captured) and divide it by the cumulative percentage of the population sampled.

Cumulative Lift = (Cumulative % of Positives at Decile i) / (Cumulative % of Population at Decile i) - Plotting: The Lift Chart is plotted with the cumulative percentage of the population (deciles) on the X-axis and the Lift value on the Y-axis.

Table 2: Corresponding Lift Chart Calculations from Table 1 Data

| Decile | % Population | Gain (%) | Cumulative Lift |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10% | 14.1% | 1.41 |

| 2 | 20% | 23.1% | 1.16 |

| 3 | 30% | 30.5% | 1.02 |

| 4 | 40% | 36.3% | 0.91 |

| 5 | 50% | 40.4% | 0.81 |

| 6 | 60% | 43.7% | 0.73 |

| 7 | 70% | 46.2% | 0.66 |

| 8 | 80% | 48.2% | 0.60 |

| 9 | 90% | 49.6% | 0.55 |

| 10 | 100% | 50.6% | 0.51 |

Interpretation and Analysis

The Lift Chart also features two primary elements [32]:

- The Model Lift Curve: Typically starts high and decreases, showing that the model's superior performance is concentrated in the top deciles.

- The Baseline: A horizontal line at Lift = 1, which represents random performance.

A strong model will show a high lift (e.g., >3) in the first one or two deciles, indicating powerful discrimination at the top of the list [1]. The point where the lift curve drops to 1 is the point beyond which using the model provides no better than random performance, defining the practical limit of the model's utility. As shown in Table 2, the model's lift is 1.41 in the top decile, meaning it is 1.41 times better than random, but this lift quickly decays, a typical characteristic.

Diagram 2: Logical relationship for calculating Lift from Gain

Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) Chart: Evaluating Distribution Separation

Theoretical Foundation

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) chart is a powerful nonparametric tool used to measure the degree of separation between the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of two samples—typically the "positive" and "negative" classes as scored by a model [33] [1]. In model evaluation, the K-S statistic quantifies the maximum difference between the cumulative distributions of the two classes, providing a single value that indicates the model's discriminatory power. A higher K-S value (from 0 to 100) signifies a greater ability to distinguish between positive and negative events, which is fundamental for diagnostic and risk stratification models in healthcare.

Construction Methodology

The K-S statistic is calculated from the cumulative distributions of the two classes [33]:

- Score and Separate: Score all instances with the model and separate them into two groups based on their actual class: "Positive" and "Negative."

- Form Cumulative Distributions: For each possible score threshold, calculate the cumulative percentage of "Positive" instances that have a score at or above that threshold (Sensitivity) and the cumulative percentage of "Negative" instances that have a score at or above that threshold (1 - Specificity).

- Calculate K-S Statistic: The K-S statistic is the maximum vertical distance between these two cumulative distribution curves across all possible score thresholds [33] [34].

Table 3: Sample Data for K-S Statistic Calculation (Maximum Difference = 41.7%)

| Score Threshold | Cumulative % Positive | Cumulative % Negative | Difference (K-S) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 10% | 1% | 9% |

| 0.85 | 25% | 5% | 20% |

| 0.75 | 45% | 10% | 35% |

| 0.65 | 65% | 23.3% | 41.7% |

| 0.55 | 80% | 45% | 35% |

| 0.45 | 90% | 70% | 20% |

| 0.00 | 100% | 100% | 0% |

Interpretation and Analysis

The K-S chart plots the cumulative percentage of both positives and negatives against the model's score, visually highlighting the point of maximum separation.

- A high K-S statistic (e.g., >40) indicates that the model can effectively separate the two populations at an optimal cutoff, which is critical for applications like identifying high-risk patients [1].

- A K-S value of 0 suggests the model cannot differentiate between the two classes, while a value of 100 represents perfect separation.

- The optimal score cutoff for operational use is often the point where the K-S maximum occurs, as it balances the trade-off between correctly identifying positives and incorrectly classifying negatives [33].

It is crucial to note that the K-S test is distribution-free and robust to outliers, but it is most appropriate for continuous data and is more sensitive to differences near the center of the distribution than in the tails [33] [34].

Comparative Analysis and Application in Drug Development

Side-by-Side Metric Comparison

Table 4: Comparative Summary of Model Evaluation Charts

| Feature | Gain Chart | Lift Chart | K-S Chart |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Shows cumulative coverage of targets [28] [30]. | Shows performance improvement over random [31] [29]. | Measures maximum separation between class distributions [33] [1]. |

| Key Question | What % of all positives will I find if I target X% of the population? | How many times better is the model than random at a given point? | How well does the model distinguish between positive and negative classes? |

| Optimal Value | Curve close to top-left corner. | High initial lift (e.g., >3) in top deciles. | High K-S statistic (closer to 100). |

| Interpretation | Guides resource allocation depth (e.g., how many to contact). | Quantifies model value and efficiency. | Identifies model's overall discriminatory power and optimal cutoff. |

| Best Use Case | Planning campaign reach or patient screening depth. | Justifying model deployment and comparing initial performance. | Risk stratification and diagnostic test evaluation. |

Application to Drug Development: A Protocol for Model Selection

In drug development, these charts guide critical decisions. For instance, when building a model to predict patients at high risk of a severe adverse event (AE) from a new therapy, the protocol would be:

- Data Preparation: Use a labeled dataset from Phase II trials, where the target variable is the occurrence of the severe AE. Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring stratified sampling to preserve the imbalance of the AE rate [2].

- Model Training and Scoring: Train multiple candidate models (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on the training set. Use the validation set to generate predicted probabilities for the AE for each model.

- Chart Generation and Evaluation:

- Gain Analysis: For each model, generate a Gain Chart on the validation set. The model that captures the highest percentage of actual AE cases in the top two deciles (i.e., the top 20% of highest-risk patients) would be favored, as it allows for efficient monitoring of the most vulnerable subgroup.

- Lift Analysis: Compare the lift values of the models at the 10% population cutoff. A model with a lift of 4.0 means it is 4 times more effective at identifying AE cases in the top tier than random chart review, directly demonstrating resource efficiency.

- K-S Analysis: Calculate the K-S statistic for each model. A model with a higher K-S statistic (e.g., 60 vs. 45) demonstrates a superior ability to separate patients who will experience an AE from those who will not, which is fundamental for reliable risk stratification.

- Final Selection and Testing: The model that demonstrates a balanced excellence across all three charts—showing strong cumulative gain, high initial lift, and a high K-S statistic—is selected. Its performance is then conclusively validated on the held-out test set to ensure generalizability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation

Table 5: Key Computational Tools for Metric Implementation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | Python Library | Core machine learning model training, prediction, and probability calibration [1]. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Python Library | Data manipulation, ranking, and aggregation required for decile analysis and metric calculation [28]. |

| Matplotlib/Seaborn | Python Library | Visualization and plotting of Gain, Lift, and K-S charts for interpretation and reporting. |

| R Language | Statistical Software | Comprehensive statistical environment with native packages for nonparametric tests and advanced plotting [34]. |

| Minitab | Commercial Software | Provides built-in procedures for generating and interpreting Gain and Lift charts [32]. |

| DataRobot | AI Platform | Automated model evaluation with integrated cumulative charts for performance comparison [29]. |

Gain, Lift, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov charts form a critical triad of diagnostics for the sophisticated selection of predictive models in research and drug development. Moving beyond monolithic accuracy metrics, they provide a dynamic view of model performance that is directly tied to strategic operational efficiency and robust statistical separation. By following the detailed methodologies and interpretive frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can objectively compare models, identify the one that best concentrates the signal of interest, and justify its deployment with clear, quantitative evidence. Integrating these tools into the standard model selection workflow ensures that predictive analytics in high-stakes environments like drug development is not only statistically sound but also pragmatically optimal.

From Theory to Practice: Applying Metrics in Clinical and Biomarker Research

In the domain of supervised machine learning, the selection of an appropriate evaluation metric is a critical decision that extends far beyond technical implementation—it directly aligns model performance with fundamental research objectives and real-world consequences. This selection is primarily governed by the nature of the predictive task: classification for discrete outcomes and regression for continuous values [35] [36]. Within applied research fields such as drug development, this choice forms part of the "fit-for-purpose" modeling strategy, ensuring that quantitative tools are closely matched to the key questions of interest and the specific context of use [37].

The core distinction is intuitive: classification models predict discrete, categorical labels (such as "spam" or "not spam," "malignant" or "benign"), while regression models predict continuous, numerical values (such as house prices, patient survival time, or biochemical concentration levels) [35] [36]. This fundamental difference in output dictates not only the choice of algorithm but also the entire framework for evaluating model success. Despite the emergence of more complex AI methodologies, these foundational paradigms remain central to the practical application of machine learning in domains where interpretability, precision, and structured data are paramount [35].

This guide provides an in-depth examination of performance metrics for classification and regression, offering researchers a structured framework for selection based on problem type, data characteristics, and domain-specific costs of error.

Core Concepts: Classification vs. Regression

Problem Formalization and Objectives

In statistical learning theory, both classification and regression are framed as function approximation problems. The core assumption is that an underlying process maps input data X to outputs Y, expressed as Y = f(X) + ε, where f is the true function and ε represents irreducible error [35]. The machine learning model's goal is to learn a function f̂(X) that best approximates f.

- Classification is the task of learning a function that maps an input to a discrete categorical label [36]. The output is qualitative and can be binary (e.g., spam vs. non-spam), nominal (e.g., dog, cat, fish), or ordinal (e.g., low, medium, high risk) [35]. The model's goal is to find optimal decision boundaries that partition the feature space into distinct classes [36].

- Regression is the task of learning a function that maps an input to a continuous numerical value [36]. The output is quantitative, representing real-valued numbers like revenue, temperature, or drug concentration [35]. The model's objective is to find the best-fit line (or curve) that minimizes the discrepancy between predicted and actual values [36].

Illustrative Examples in Drug Development

The distinction becomes critically important in fields like pharmaceutical research, where the choice of model must align with the scientific question:

- A classification problem might involve diagnosing based on symptoms or predicting whether a compound will be toxic [35].

- A regression problem could involve predicting a continuous outcome like a patient's specific drug concentration level, the number of days a patient stays in hospital, or estimating disease risk [35].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Classification and Regression

| Feature | Classification | Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Output Type | Discrete categories (e.g., "spam", "not spam") [36] | Continuous numerical value (e.g., price, temperature) [36] |

| Core Objective | Predict class membership [36] | Predict a precise numerical quantity [36] |

| Model Output | Decision boundary [36] | Best-fit line or curve [36] |

| Example Algorithms | Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, SVM [36] | Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression, Ridge Regression [35] |

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting model type and evaluation metrics based on problem definition, data characteristics, and business goals.

Evaluation Metrics for Classification

Classification metrics are derived from the confusion matrix, a table that describes the performance of a classifier by comparing actual labels to predicted labels [10] [1]. The core components of a confusion matrix for binary classification are:

- True Positives (TP): Actual positives correctly identified.

- True Negatives (TN): Actual negatives correctly identified.

- False Positives (FP): Actual negatives incorrectly classified as positive (Type I error).

- False Negatives (FN): Actual positives incorrectly classified as negative (Type II error) [10] [15].

Key Metric Definitions and Interpretations

Accuracy: Measures the overall correctness of the model. It is the ratio of all correct predictions (both positive and negative) to the total number of predictions [10] [15]. Accuracy is a good initial metric for balanced datasets but becomes misleading when classes are imbalanced [10].

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)Precision (Positive Predictive Value): Measures the accuracy of positive predictions. It answers the question: "When the model predicts positive, how often is it correct?" [10] [15]. High precision is critical when the cost of a false positive is high.

Precision = TP / (TP + FP)Recall (Sensitivity or True Positive Rate): Measures the model's ability to identify all actual positive instances. It answers the question: "What fraction of all actual positives did the model find?" [10] [15]. High recall is vital when missing a positive case (false negative) is very costly.

Recall = TP / (TP + FN)F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both concerns [38] [10]. It is especially useful for imbalanced datasets where you need to find a trade-off between false positives and false negatives [10].

F1 Score = 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall)ROC AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve): Represents the model's ability to distinguish between classes across all possible classification thresholds. The AUC score is the probability that a randomly chosen positive instance is ranked higher than a randomly chosen negative instance [38]. It is ideal when you care about ranking and when positive and negative classes are equally important.

PR AUC (Precision-Recall AUC): The area under the Precision-Recall curve. This metric is more informative than ROC AUC for highly imbalanced datasets, as it focuses primarily on the model's performance on the positive class [38].

Strategic Metric Selection for Classification

The choice of classification metric should be driven by the research objective and the cost associated with different types of errors [10] [15].

Table 2: A Guide to Selecting Classification Metrics

| Research Context & Goal | Recommended Metric(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced Classes, Equal Cost of Errors | Accuracy [10] | Provides a simple, overall measure of correctness. |

| High Cost of False Positives (FP)(e.g., spam classification) | Precision [10] [15] | Ensures that when a positive prediction is made, it is highly reliable. |

| High Cost of False Negatives (FN)(e.g., disease screening, fraud detection) | Recall [10] [15] | Ensures that most actual positive cases are captured, minimizing misses. |

| Imbalanced Data & Need for Balance between FP and FN | F1 Score [38] [10] | Harmonizes precision and recall into a single score to find a balance. |

| Need for Ranking & Overall Performance View | ROC AUC [38] | Evaluates the model's ranking capability across all thresholds. |

| Highly Imbalanced Data, Focus on Positive Class | PR AUC (Average Precision) [38] | Provides a more realistic view of performance on the rare class. |

Diagram 2: Logical relationships between the confusion matrix and key classification metrics, showing how core components feed into different calculations.

Evaluation Metrics for Regression

Regression metrics quantify the difference between the continuous values predicted by a model and the actual observed values. These differences are known as residuals (residual = actual - prediction) [39]. Different metrics aggregate and interpret these residuals in various ways, each with specific sensitivities and use cases.

Key Metric Definitions and Interpretations

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The average of the absolute differences between predicted and actual values [39]. MAE is linear and provides an easy-to-interpret measure of average error magnitude in the original units of the target variable. It is robust to outliers [39].

MAE = (1/n) * Σ|actual - prediction|Mean Squared Error (MSE): The average of the squared differences between predicted and actual values [39]. By squaring the errors, MSE heavily penalizes larger errors. This property is useful for optimization (as it's differentiable) but makes it sensitive to outliers [39].

MSE = (1/n) * Σ(actual - prediction)²Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): The square root of the MSE [39]. This brings the error back to the original units of the target variable, improving interpretability. It retains the squaring property of MSE, meaning it also penalizes large errors more than small ones [39].

RMSE = √MSER-squared (R²) or Coefficient of Determination: A scale-independent metric that represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables [39]. It is a relative measure, often used to compare models on the same dataset. An R² of 1.0 indicates perfect prediction, while 0 indicates the model performs no better than predicting the mean [39].

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): The average of the absolute percentage differences between predicted and actual values [39]. It provides an intuitive, percentage-based measure of error, making it easy to communicate to business stakeholders. However, it is asymmetric and can be problematic when actual values are zero or very close to zero [39].

MAPE = (1/n) * Σ|(actual - prediction)/actual|

Strategic Metric Selection for Regression

The choice of a regression metric should be guided by the importance of large errors, the presence of outliers, and the need for interpretability [4] [39].

Table 3: A Guide to Selecting Regression Metrics

| Research Context & Goal | Recommended Metric(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| General Purpose, Interpretability, Robustness to Outliers | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [39] | Easy to understand; not overly penalized by occasional large errors. |

| Large Errors are Critical, Model Optimization | (Root) Mean Squared Error (MSE/RMSE) [39] | Heavily penalizes large errors, which is often desirable. RMSE is in the original units. |

| Comparing Model Performance, Explaining Variance | R-squared (R²) [39] | Provides a standardized, unitless measure of how well the model fits compared to a baseline mean model. |

| Communicating Results to Non-Technical Stakeholders | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [39] | Expresses error as a percentage, which is often intuitively understood. |

| Comparing Models Across Different Datasets/Scales | R-squared (R²), MAPE [39] | These normalized or scale-independent metrics allow for fair comparison. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

Protocol for Comparing Binary Classifiers

This protocol outlines a standard methodology for evaluating and selecting between multiple binary classification models, emphasizing robust metric calculation.

- Data Splitting and Preprocessing: Split the dataset into training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and test (e.g., 15%) sets. The validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning and threshold selection, while the test set is held back for the final, unbiased evaluation. Address class imbalance at this stage if necessary, using techniques like SMOTE on the training set only.

- Model Training and Prediction: Train each candidate model (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on the training set. Use the trained models to generate prediction scores (probabilities) for the validation set.

- Threshold Selection and Metric Calculation on Validation Set:

- For metrics that require a threshold (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1), generate a table or plot showing the metric values across a range of thresholds (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.9).

- Select the optimal threshold based on the research goal (e.g., maximize F1, achieve 95% recall).

- Apply the chosen threshold to convert prediction scores into class labels.

- Calculate the confusion matrix and all relevant metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1) [38] [10].

- Threshold-Independent Metric Calculation on Validation Set: Calculate threshold-independent metrics like ROC AUC and PR AUC directly from the prediction scores [38].

- Final Evaluation on Test Set: Apply the model and the threshold selected in Step 3 to the held-out test set. Report all final metrics calculated exclusively on the test set. This provides an unbiased estimate of model performance on unseen data.

- Statistical Significance Testing: Perform statistical tests (e.g., McNemar's test for paired classification results) to determine if the performance differences between the top-performing models are statistically significant.

Protocol for Evaluating Regression Models

This protocol provides a framework for assessing the performance of regression models, focusing on error distribution and model comparison.

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training and test sets, ensuring the test set remains untouched during model development. Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set for robust hyperparameter tuning.

- Model Training and Prediction: Train regression models (e.g., Linear Regression, Decision Tree Regressor, etc.) on the training set. Generate predictions for the test set.

- Residual Analysis:

- Calculate the residuals (actual - prediction) for each observation in the test set [39].

- Plot a histogram and a Q-Q plot of the residuals to check for normality. Many model assumptions rely on residuals being approximately normally distributed.

- Plot residuals against predicted values. A healthy model will show residuals randomly scattered around zero with constant variance (homoscedasticity). Any pattern (e.g., a funnel shape) indicates a model flaw (heteroscedasticity).

- Calculation of Multiple Error Metrics: Calculate a suite of error metrics on the test set predictions, including MAE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE [39]. Reporting multiple metrics provides a holistic view of model performance.

- Calculation of Goodness-of-Fit Metric: Calculate R-squared on the test set to understand the proportion of variance explained [39].

- Benchmarking: Compare the model's performance (e.g., using MAE or RMSE) against a simple baseline model, such as predicting the mean or median of the training target variable. This contextualizes the model's practical utility.

This section details key software tools and libraries that facilitate the implementation of the evaluation metrics and protocols discussed in this guide.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metric Implementation

| Tool / Library | Primary Function | Key Features for Metric Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn (Python) | General-purpose ML library | Provides comprehensive suite of functions: accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score, roc_auc_score, mean_absolute_error, mean_squared_error, r2_score. Essential for standard model evaluation [35] [38]. |

| Evidently AI (Python) | AI Observability and Evaluation | Specializes in model evaluation and monitoring. Offers interactive visualizations for metrics, data drift, and model performance reports, going beyond static calculations [15]. |

| Neptune.ai | ML Experiment Tracking | Logs, visualizes, and compares ML model metadata (parameters, metrics, curves) across multiple runs. Crucial for managing complex experiments and metric comparisons [38]. |

| LightGBM / XGBoost | Gradient Boosting Frameworks | High-performance algorithms for both classification and regression that provide native support for custom evaluation metrics and are widely used in competitive and industrial settings [38]. |

| TensorFlow / PyTorch | Deep Learning Frameworks | Offer low-level control for building custom model architectures (including neural networks for regression and classification) and implementing tailored loss functions that align with evaluation metrics [35]. |

Clinical prediction models are increasingly fundamental to precision medicine, providing data-driven estimates for individual patient diagnosis and prognosis. These models fall broadly into two categories: diagnostic models, which estimate the probability of a specific condition being present, and prognostic models, which estimate the probability of developing a specific health outcome over a defined time period [40]. In oncology and other medical fields, these models enable superior risk stratification compared to simpler classification systems by incorporating multiple predictors simultaneously to generate more precise, individualized risk estimates [40]. The advent of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly expanded the methodological toolkit available for model development, offering enhanced capabilities to handle complex, non-linear relationships in multimodal data [40] [41].

However, the development and implementation of robust, clinically useful models present substantial methodological challenges. Many published models suffer from poor design, methodological flaws, incomplete reporting, and high risk of bias, limiting their clinical implementation and potential impact on patient care [40] [42]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for the development, evaluation, and implementation of diagnostic and prognostic models within the context of predictive model performance metrics research, with specific considerations for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in advancing precision medicine.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

Diagnostic vs. Prognostic Prediction Models

Diagnostic Prediction Models: Estimate the probability of a specific disease or condition at the time of assessment. These models typically use cross-sectional data and are intended to support clinical decision-making regarding the presence or absence of a pathological state [40]. Example applications include models that distinguish malignant from benign lesions or predict the probability of bacterial infection.

Prognostic Prediction Models: Estimate the probability of developing a specific health outcome over a future time period. These models require longitudinal data and are used to forecast disease progression, treatment response, or survival outcomes [40]. Examples include models predicting overall survival in cancer patients or risk of disease recurrence following treatment.

Dynamic Prediction Models (DPMs)

Traditional prognostic models often rely on static baseline characteristics, which may become less accurate over time as patient conditions evolve. Dynamic Prediction Models address this limitation by incorporating time-varying predictors and repeated measurements to update risk estimates throughout a patient's clinical course [43]. These models are particularly valuable in chronic conditions and oncology, where disease trajectories and treatment responses can change substantially over time.

Table 1: Categories of Dynamic Prediction Models and Their Applications

| Model Category | Prevalence | Key Characteristics | Typical Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|