Beyond Normality: A Practical Guide to Addressing Non-Normal Residuals in Biomedical Research

This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and addressing non-normal residuals in statistical models.

Beyond Normality: A Practical Guide to Addressing Non-Normal Residuals in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and addressing non-normal residuals in statistical models. Covering foundational concepts, diagnostic methods, robust statistical techniques, and validation strategies, the article synthesizes current best practices to ensure reliable inference in clinical trials and biomedical studies. Readers will learn to distinguish between common misconceptions and actual requirements, apply robust methods like HC standard errors and bootstrap techniques, and implement a structured workflow for handling non-normal data while maintaining statistical validity.

Demystifying Non-Normal Residuals: What They Are and Why They Matter

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the actual normality assumption in linear models? The core assumption is that the errors (ϵ), the unobservable differences between the true model and the observed data, are normally distributed. Since we cannot observe these errors directly, we use the residuals (e)—the differences between the observed and model-predicted values—as proxies to check this assumption [1] [2]. The assumption is not that the raw data (the outcome or predictor variables) themselves are normally distributed [2].

2. Why is checking residuals more important than checking raw data? A model can meet the normality assumption even when the raw outcome data is not normally distributed. The critical point is the distribution of the "noise" or what the model fails to explain. Examining residuals allows you to diagnose if this unexplained component is random and normal, which validates the statistical tests for your model's coefficients. Analyzing raw data does not provide this specific diagnostic information about model adequacy [2].

3. My residuals are not normal. Should I immediately abandon my linear model? Not necessarily. The Gaussian models used in regression and ANOVA are often robust to violations of the normality assumption, especially when the sample size is not small [3]. For large sample sizes, the Central Limit Theorem helps ensure that the sampling distribution of your estimates is approximately normal, even if the residuals are not [2] [4] [5]. You should be more concerned about violations of other assumptions, like linearity or homoscedasticity, or the presence of highly influential outliers [3].

4. When is non-normal residuals a critical problem? Non-normality becomes a more serious concern primarily in small sample sizes, as it can lead to inaccurate p-values and confidence intervals [2] [5]. If your residuals show a clear pattern because the relationship between a predictor and the outcome is non-linear, this is a more fundamental model misspecification that must be addressed [6] [7].

Diagnostic Guide: Checking for Normal Residuals

Follow this workflow to systematically diagnose the normality of your model's residuals.

Key Diagnostic Methods

1. Normal Q-Q Plot (Recommended) This is the primary tool for visually assessing normality [2] [7].

- Method: Plot the standardized residuals against the theoretical quantiles of a standard normal distribution.

- Interpretation: If the residuals are normally distributed, the points will fall approximately along the straight reference line. Systematic deviations from the line, especially in the tails, suggest non-normality [7].

- Implementation:

2. Histogram of Residuals A simple, complementary visual check.

- Method: Create a histogram of the residuals and overlay a normal distribution curve with the same mean and standard deviation.

- Interpretation: Compare the shape of the histogram to the normal curve. The closer the match, the more reasonable the normality assumption [2] [4].

3. Formal Statistical Tests (Use with Caution) Tests like the Shapiro-Wilk test provide a p-value for normality.

- Method: Execute the test on the residuals. The null hypothesis is that the data are normally distributed.

- Interpretation: A small p-value (e.g., < 0.05) provides evidence against normality. However, these tests are not recommended as a primary tool because they lack power in small samples (where normality matters most) and are overly sensitive to minor deviations in large samples (where normality matters less) [2] [5].

Troubleshooting Protocols for Non-Normal Residuals

If your diagnostics indicate non-normal residuals, follow this structured protocol to identify and implement a solution.

Protocol 1: Data Transformation

Transforming your outcome variable (Y) can address non-normality, non-linearity, and heteroscedasticity simultaneously [1] [2].

Methodology:

- Choose a Transformation: Common choices include:

- Logarithmic (

log(Y)): Useful for right-skewed data and when variance increases with the mean [1] [6]. - Square Root (

sqrt(Y)): Effective for data with counts and can handle zero values [2]. - Inverse (

1/Y) Can be powerful for severe skewness. - Box-Cox Transformation: A more sophisticated, data-driven method that finds the optimal power transformation parameter (

λ) [1].

- Logarithmic (

- Implement and Re-fit:

- Apply the transformation to your outcome variable.

- Re-fit the linear model using the transformed variable.

- Perform a new residual analysis on the updated model to check if the violation has been corrected.

Box-Cox Implementation in R:

Protocol 2: Use Alternative Modeling Approaches

If transformations are ineffective or inappropriate, consider a different class of models.

Methodology:

- Generalized Linear Models (GLMs): GLMs extend linear models to handle non-normal error distributions (e.g., Poisson for count data, Binomial for binary data) through a link function [4] [3].

- Nonparametric Tests: For simple group comparisons, tests like the Mann-Whitney U test (代替 two-sample t-test) or Kruskal-Wallis test (代替 one-way ANOVA) do not assume normality [4].

- Bootstrap Methods: Use resampling techniques to estimate the sampling distribution of your parameters, making no strict distributional assumptions [4].

Caution: These advanced methods have their own assumptions and pitfalls. For example, Poisson GLMs can be anticonservative if overdispersion is not accounted for [3].

Table 1: Key Software Packages for Residual Diagnostics

| Software/Package | Key Diagnostic Functions | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| R (with base stats) | plot(lm_object), qqnorm(), shapiro.test() |

Comprehensive, automated diagnostic plotting and formal testing [7]. |

| R (with AID package) | boxcoxfr() |

Performing Box-Cox transformation and checking normality/homogeneity of variance afterward [1]. |

| R (with MASS package) | boxcox() |

Finding the optimal λ for a Box-Cox transformation [1]. |

| SAS (PROC TRANSREG) | model boxcox(Y) = ... |

Implementing Box-Cox power transformation for regression [1]. |

| Minitab | Stat > Control Charts > Box-Cox Transformation | User-friendly GUI for performing Box-Cox analysis [1]. |

| Python (StatsModels) | qqplot(), het_breuschpagan() |

Generating Q-Q plots and conducting formal tests for heteroscedasticity within a Python workflow [8]. |

Table 2: Guide to Common Data Transformations

| Transformation | Formula (for Y) | Ideal For / Effect | Handles Zeros? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logarithmic | log(Y) |

Right-skewness; variance increasing with mean. | No (use log(Y+1)) [2]. |

| Square Root | sqrt(Y) |

Count data; moderate right-skewness. | Yes [2]. |

| Inverse | 1/Y or -1/Y |

Severe right-skewness; reverses data order. | No [2]. |

| Box-Cox | (Y^λ - 1)/λ |

Data-driven; finds the best power transformation. | No (for λ ≤ 0) [1]. |

In statistical research, particularly in fields like drug development, encountering non-normal data is the rule, not the exception. The distribution of residuals—the differences between observed and predicted values—often deviates from the ideal bell curve, potentially violating the assumptions of many standard statistical models. This is where the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) becomes an indispensable tool. The CLT states that the sampling distribution of the mean will approximate a normal distribution, regardless of the population's underlying distribution, as long as the sample size is sufficiently large [9] [10]. This theorem empowers researchers to draw valid inferences from their data, even when faced with skewness or outliers, by relying on the power of sample size to bring normality to the means.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common problems researchers face when dealing with non-normal residuals and how the CLT provides a pathway to robust conclusions.

FAQ 1: My model's residuals are not normally distributed. Are my analysis results completely invalid?

Not necessarily. While non-normal residuals can be a concern, the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) can often "save the day." The CLT assures that the sampling distribution of your parameter estimates (like the mean) will be approximately normal if your sample size is large enough, even if the underlying data or residuals are not [10] [11]. This means that for large samples, the p-values and confidence intervals for your mean estimates can still be reliable. For smaller samples from strongly non-normal populations, consider robust standard errors or bootstrapping to ensure your inferences are valid [11].

FAQ 2: How large does my sample size need to be for the CLT to apply?

There is no single magic number, but a common rule of thumb is that a sample size of at least 30 is often "sufficiently large" [9] [12]. However, the required size depends heavily on the shape of your original population:

- For moderately skewed distributions, a sample size of 40 might be adequate [10].

- For severely skewed distributions, you may need a much larger sample size (e.g., >80) for the sampling distribution to appear normal [10]. The key is that the more your population distribution differs from normality, the larger the sample size you will need.

FAQ 3: The CLT is about sample means, but my regression model's outcome variable itself is not normal. What should I do?

You are correct to focus on the residuals. The CLT's guarantee of normality applies to the sampling distribution of the mean, not the raw data itself [10]. For your regression model, the concern is whether the residuals are normal. If you have a large sample size, the CLT helps justify that the sampling distribution of your regression coefficients (which are a type of mean) will be approximately normal, making your tests and confidence intervals valid [11]. For inference on the coefficients, using OLS with robust (sandwich) estimators for standard errors is a good practice that does not require a normality assumption [11].

FAQ 4: Besides relying on the CLT, what are other valid approaches to handling non-normal residuals?

The CLT is one of several strategies. A taxonomy of common approaches includes [13]:

- Transforming the Data: Applying a non-linear function (e.g., log, square root) to the dependent variable to make the residuals more normal.

- Using Robust Estimators: Employing statistical techniques, like the Huber M-estimator, that are less sensitive to outliers and non-normality.

- Bootstrapping: Empirically constructing the sampling distribution of your statistic by resampling your data, which does not rely on normality assumptions.

- Non-Parametric Methods: Using rank-based tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test) that do not assume a specific distribution.

- Generalized Linear Models (GLMs): Switching to a different model family designed for non-normal error distributions (e.g., logistic for binomial, Poisson for count data).

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Verifying CLT Applicability for Your Dataset

This protocol provides a step-by-step method to empirically demonstrate how the CLT stabilizes parameter estimates from a non-normal population, a common scenario in drug development research.

1. Define Population and Parameter: Clearly describe the population of interest (e.g., all potential patients with a specific condition) and the parameter you wish to estimate (e.g., mean change in blood pressure).

2. Determine Sample Size and Replications:

- Select a range of sample sizes (n) to investigate (e.g., n = 5, 20, 40, 80, 100).

- Choose a large number of replications (e.g., 10,000) for each sample size to build a reliable sampling distribution [10].

3. Draw Repeated Samples and Calculate Statistics: For each sample size n, repeat the following process many times [9] [10]:

* Randomly select n observations from your population (or a simulated population that mirrors your data's non-normal distribution).

* Calculate and record the sample mean for that sample.

4. Analyze the Sampling Distributions: For each sample size, create a histogram of the recorded sample means.

- Result Interpretation: You will observe that as

nincreases, the distribution of the sample means becomes more symmetrical and bell-shaped, converging towards a normal distribution. The variability (standard deviation) of these means, known as the standard error, will also decrease [10] [12].

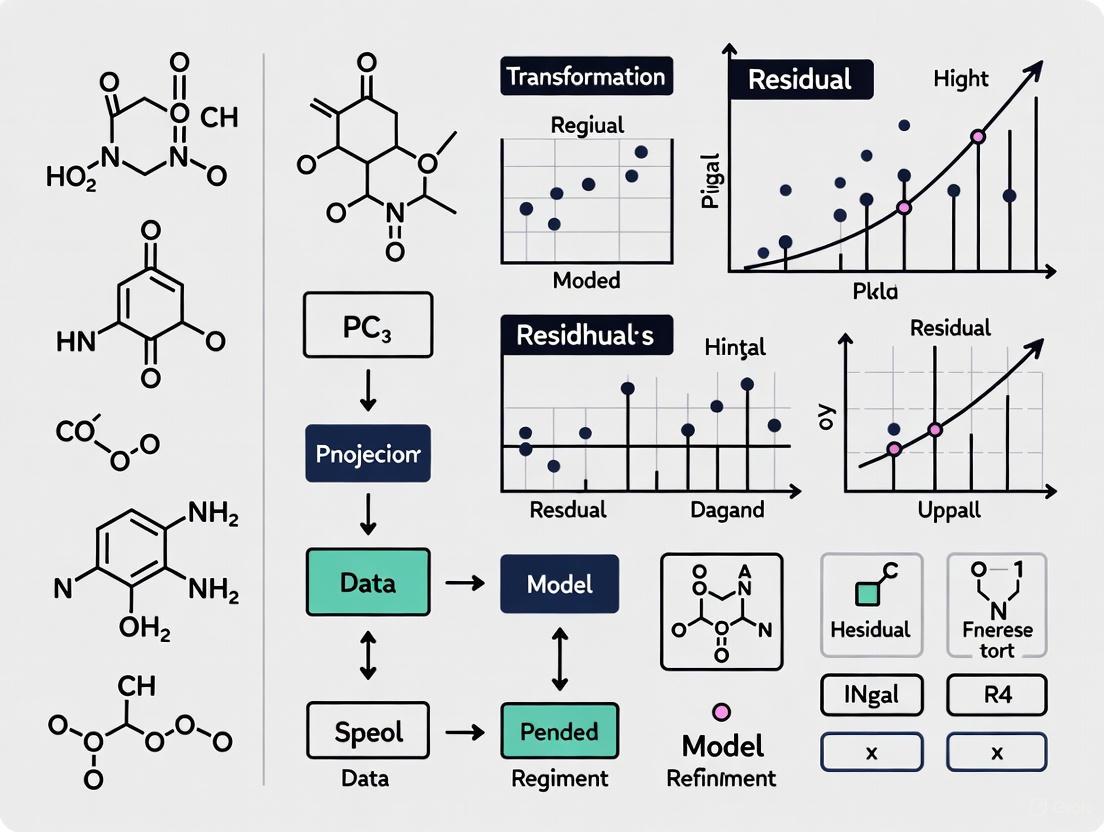

Protocol 2: Diagnostic Workflow for Non-Normal Residuals

Follow this structured workflow when your linear model diagnostics indicate non-normal residuals.

Data Presentation & Workflows

How Sample Size Influences the Sampling Distribution

The table below summarizes the core relationship between sample size and the sampling distribution of the mean, which is the foundation of the CLT [9] [10] [12].

Sample Size (n) |

Impact on Shape of Sampling Distribution | Impact on Standard Error (Spread) | Practical Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (n < 30) | May be non-normal; often resembles the population distribution. | High spread; less precise estimates. | CLT does not reliably apply. Use alternative methods (e.g., bootstrapping, non-parametric tests) [9]. |

| Sufficiently Large (n ≥ 30) | Approximates a normal distribution, even for non-normal populations. | Moderate spread; more precise. | CLT generally holds, justifying the use of inferential methods based on normality (e.g., t-tests, confidence intervals) [9] [12]. |

| Very Large (n >> 30) | Very close to a normal distribution. | Low spread; highly precise estimates. | CLT provides a strong foundation for inference. Estimates are very close to the true population parameter. |

Taxonomy of Approaches to Address Non-Normality

When faced with non-normal residuals, researchers have a toolbox of methods. The choice depends on your goal, sample size, and the nature of the non-normality [13].

| Method | Core Principle | Best Used When... |

|---|---|---|

| Increase Sample Size (CLT) | Leverages the CLT to achieve normality in the sampling distribution of the mean. | You have the resources to collect a large sample (n ≥ 30) and the population variance is finite [9] [10]. |

| Data Transformation | Applies a mathematical function (e.g., log) to the raw data to make the residual distribution more normal. | The data is skewed or has non-constant variance; interpretation of transformed results is still possible [13]. |

| Robust Statistics | Uses estimators and inference methods that are less sensitive to outliers and violations of normality. | The data contains outliers or has heavy tails; you want to avoid the influence of extreme values [13] [11]. |

| Bootstrap Methods | Empirically constructs the sampling distribution by repeatedly resampling the original data with replacement. | The sample size is moderate, and you want to avoid complex distributional assumptions [13] [11]. |

| Non-Parametric Tests | Uses ranks of the data rather than raw values, making no assumption about the underlying distribution. | The sample size is very small, or data is on an ordinal scale [13]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

This table lists key "reagents" — the conceptual and statistical tools needed to conduct a robust analysis in the face of non-normality.

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Central Limit Theorem (CLT) | The theoretical foundation that guarantees the normality of sample means from large samples, justifying parametric inference [9] [10]. |

| Robust Standard Errors | A modification to standard error calculations that makes them valid even when residuals are not normal or have non-constant variance [13] [11]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling | A computational method to estimate the sampling distribution of any statistic, providing reliable confidence intervals without normality assumptions [13] [11]. |

| Q-Q Plot (Normal Probability Plot) | A diagnostic graph used to visually assess the deviation of residuals from a normal distribution. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SPSS) | Platforms that provide built-in functions to calculate robust standard errors, perform bootstrapping, and generate diagnostic plots [14]. |

Solution Pathways Visualization

When your primary analysis is threatened by non-normal residuals, the following decision pathway can guide you toward a statistically sound solution. This integrates the CLT with other advanced methods.

In biomedical and clinical research, statistical analysis often relies on the assumption of normally distributed data. However, real-world data from these fields frequently violate this assumption. Understanding the common sources and characteristics of non-normality is crucial for selecting appropriate analytical methods and ensuring the validity of research conclusions. This guide provides a structured approach to identifying, diagnosing, and addressing non-normal data in biomedical contexts.

What are the most common non-normal distributions in health sciences research?

A systematic review of studies published between 2010 and 2015 identified the frequency of appearance of non-normal distributions in health, educational, and social sciences. The ranking below is based on 262 included abstracts, with 279 distributions considered in total [15].

Table 1: Frequency of Non-Normal Distributions in Health Sciences Research [15]

| Distribution | Frequency of Appearance (n) | Common Data Types/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gamma | 57 | Reaction times, response latency, healthcare costs, clinical assessment indexes |

| Negative Binomial | 51 | Count data, particularly with over-dispersion |

| Multinomial | 36 | Categorical outcomes with multiple levels |

| Binomial | 33 | Binary outcomes (e.g., success/failure, presence/absence) |

| Lognormal | 29 | Medical costs, survival data, physical and verbal violence measures |

| Exponential | 20 | Survival data from clinical trials |

| Beta | 5 | Proportions, percentages |

Why is non-normality so prevalent in clinical and psychological data?

Many variables measured in clinical, psychological, and mental health research are intrinsically non-normal by nature [16]. The assumption of a normal distribution is often a statistical convention rather than a reflection of reality.

Common Non-Normal Patterns in Psychological Data [16]:

- Right-Skewed Distributions: Occupational stress among call center workers often clusters toward the upper end of scales.

- Zero-Inflated and Skewed Distributions: Symptoms of anxiety, depression, or substance use in the general population, where most report minimal or no symptoms and a small subset experiences severe distress.

- Multimodal Distributions: Substance use behavior in community samples can show distinct groups of non-users, minimal users, and heavy users.

- Negatively Skewed Distributions: Self-reported measures of social desirability or personality traits, where scores cluster near the maximum due to response biases.

Inherent Data Structures: The pervasiveness of non-normality is also linked to the types of data generated in these fields [15] [16]:

- Bounded Data: Data from rating scales or percentages have inherent upper and lower limits.

- Discrete Data: Counts (e.g., number of episodes, hospital visits) and categorical outcomes (e.g., disease stage, treatment type) are not continuous.

- Skewed Continuous Data: Variables like healthcare costs, response times, and biological markers often have a natural lower bound of zero and no upper bound, leading to positive skew.

How do I diagnose non-normal residuals in my regression model?

Diagnosing non-normality involves both visual and statistical tests applied to the residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values), not necessarily the raw data itself [17] [18].

Table 2: Diagnostic Tools for Non-Normal Residuals

| Method | Type | What it Checks | Interpretation of Non-Normality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histogram | Visual | Shape of the residual distribution | A non-bell-shaped, asymmetric distribution indicates skewness [17]. |

| Q-Q Plot | Visual | Fit to a theoretical normal distribution | Points systematically deviating from the straight diagonal line indicate non-normality (e.g., S-shape for skewness) [17] [18]. |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | Statistical Test | Null hypothesis that data is normal | A p-value < 0.05 provides evidence to reject the null hypothesis of normality [17]. |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test | Statistical Test | Goodness-of-fit to a specified distribution | A p-value < 0.05 suggests the empirical distribution of residuals differs from a normal distribution [17]. |

| Anderson-Darling Test | Statistical Test | Goodness-of-fit, with emphasis on tails | A p-value < 0.05 indicates non-normality; more sensitive to deviations in the tails of the distribution [17]. |

The following workflow outlines a standard process for diagnosing non-normal residuals:

What are the practical consequences of ignoring non-normal residuals?

Using models that assume normality when the residuals are non-normal can compromise the validity of your research [16] [17].

- Inaccurate Inference: Hypothesis tests (e.g., t-tests, F-tests) and the construction of confidence intervals rely on the normality assumption. Violations can lead to:

- Inflated Type I Error Rate: Falsely detecting a significant effect when none exists.

- Inflated Type II Error Rate: Failing to detect a true effect.

- Inaccurate p-values that do not reflect the true error distribution [17].

- Biased Estimates: In the presence of non-normal errors, especially with outliers, parameter estimates (coefficients) can become biased or inefficient, affecting predictive accuracy [17].

- Unreliable Standard Errors: The estimates of variability (standard errors) for model coefficients may be incorrect, leading to misleading conclusions about the precision of the estimates [17].

What can I do to address non-normality in my analysis?

When non-normality is detected, researchers have a taxonomy of approaches to choose from, each with different motivations and implications [19].

Table 3: Approaches for Addressing Non-Normality

| Category | Method | Brief Description | Use Case Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change the Data | Data Transformation | Applies a mathematical function (e.g., log, square root) to the dependent variable to make its distribution more normal. | Log-transforming highly skewed healthcare cost data [17]. |

| Change the Data | Trimming / Winsorizing | Removes (trimming) or recodes (Winsorizing) extreme outliers. | Addressing a small number of extreme values unduly influencing the model [19]. |

| Change the Model | Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) | A flexible extension of linear models for non-normal data (e.g., gamma, negative binomial) without transforming the raw data. | Modeling count data with over-dispersion using a Negative Binomial regression [15]. |

| Change the Model | Non-parametric Tests | Uses rank-based methods (e.g., Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis) that do not assume normality. | Comparing two groups on a highly skewed outcome variable [16]. |

| Change the Inference | Robust Standard Errors | Uses heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors (HCCMs) to get reliable p-values and CIs even if errors are non-normal. | When the primary concern is valid inference in the presence of non-normal/heteroscedastic errors [19] [17]. |

| Change the Inference | Bootstrap Methods | Empirically constructs the sampling distribution of estimates by resampling the data, avoiding reliance on normality. | Creating confidence intervals for a statistic when the sampling distribution is unknown or non-normal [19] [17]. |

The following diagram helps guide the selection of an appropriate method based on your data and research goals:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 4: Essential Analytical Tools for Handling Non-Normal Data

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Platform/Library |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Provides the computational environment for implementing advanced models and diagnostics. | R, Python (with libraries), SAS, Stata |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | Formal statistical test for normality, particularly effective for small to moderate sample sizes. | shapiro.test() in R; scipy.stats.shapiro in Python |

| Q-Q Plot Function | Creates a visual diagnostic plot to compare the distribution of residuals to a normal distribution. | qqnorm() & qqline() in R; statsmodels.graphics.gofplots.qqplot in Python |

| Box-Cox Transformation | Identifies an optimal power transformation to reduce skewness and approximate normality. | MASS::boxcox() in R; scipy.stats.boxcox in Python |

| GLM Framework | Fits regression models for non-normal data (e.g., Gamma, Binomial, Negative Binomial). | glm() in R; statsmodels.formula.api.glm in Python |

| Bootstrap Routine | Implements resampling methods to derive robust confidence intervals without normality assumptions. | boot package in R; sklearn.utils.resample in Python |

Detection and Diagnosis: Tools for Identifying Non-Normal Residuals

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary regression assumptions these diagnostic plots help to check? These plots primarily help assess three key assumptions of linear regression [7] [20]:

- Residuals vs. Fitted Plot: Checks the linearity assumption and helps identify non-linear patterns.

- Normal Q-Q Plot: Checks the normality assumption of the residuals.

- Scale-Location Plot: Checks the homoscedasticity assumption (constant variance of residuals).

Q2: My Normal Q-Q plot has points that form an 'S'-curve. What does this indicate? An 'S'-curve pattern typically indicates that the tails of your residual distribution are either heavier or lighter than a true normal distribution [21]. When the ends of the line of points curve away from the reference line, it means you have more extreme values (heavier tails) than expected under normality [21].

Q3: The points in my Residuals vs. Fitted plot show a distinct U-shaped curve. What is the problem? A U-shaped pattern is a classic sign of non-linearity [7] [6]. It suggests that the relationship between your predictors and the outcome variable is not purely linear and that your model may be missing a non-linear component (e.g., a quadratic term) [7] [6].

Q4: My Scale-Location plot shows a funnel shape where the spread of residuals increases with the fitted values. What should I do? This funnel shape indicates heteroscedasticity—a violation of the constant variance assumption [7] [6]. A common solution is to apply a transformation to your dependent variable (e.g., log or square root transformation) [6] [22]. This can also sometimes be addressed by including a missing variable in your model [6].

Q5: How serious is a violation of the normality assumption in linear regression? With large sample sizes (e.g., where the number of observations per variable is >10), violations of normality often do not noticeably impact the results, particularly the estimates of the coefficients [13] [22]. The normality assumption is most critical for the unbiased estimation of standard errors, confidence intervals, and p-values [13]. However, assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and independence are influential even with large samples [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Interpreting Patterns in Q-Q Plots

The Normal Q-Q (Quantile-Quantile) plot assesses if the residuals are normally distributed. Ideally, points should closely follow the dashed reference line [7].

| Observed Pattern | Likely Interpretation | Recommended Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Points follow the line | Residuals are approximately normal. | No action required [7]. |

| Ends curve away from the line (S-shape) | Heavy-tailed distribution (more extreme values than expected) [21]. | Consider a transformation of the outcome variable; use robust regression methods; or, if the goal is inference and the sample size is large, the model may still be acceptable [13] [20] [22]. |

| Systematic deviation, especially at ends | Skewness (non-normality) in the residuals [7]. | Apply a transformation (e.g., log, square root) to the dependent variable [6] [20] [22]. |

Interpreting Patterns in Residuals vs. Fitted Plots

This plot helps identify non-linear patterns and outliers. In a well-behaved model, residuals should be randomly scattered around a horizontal line at zero without any discernible structure [7] [6].

| Observed Pattern | Likely Interpretation | Recommended Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Random scatter around zero | Linearity assumption appears met. Homoscedasticity may be present [7]. | No action needed. |

| U-shaped or inverted U-shaped curve | Unmodeled non-linearity [7] [6]. | Add polynomial terms (e.g., (X^2)) or other non-linear transformations of the predictors to the model [7] [22]. |

| Funnel or wedge shape | Heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance) [7] [6]. | Transform the dependent variable (e.g., log transformation); use weighted least squares; or use heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors (HCCM) [13] [6] [22]. |

Interpreting Patterns in Scale-Location Plots

Also called the Spread-Location plot, it directly checks the assumption of homoscedasticity. A horizontal line with randomly spread points indicates constant variance [7].

| Observed Pattern | Likely Interpretation | Recommended Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal line with random scatter | Constant variance (homoscedasticity) [7]. | Model assumption is satisfied. |

| Clear positive or negative slope | Heteroscedasticity is present; the spread of residuals changes with the fitted values [7] [6]. | Apply a variance-stabilizing transformation to the dependent variable; consider using a generalized linear model (GLM) or robust standard errors [13] [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Analysis

Protocol 1: Generating and Visualizing Diagnostic Plots in R This protocol details the standard method for creating the core diagnostic plots using base R.

- Fit Linear Model: Use the

lm()function to fit your regression model. - Generate Plots: Use the

plot()function on the model object to produce the diagnostic plots. - Interpretation: The four plots generated are: Residuals vs Fitted, Normal Q-Q, Scale-Location, and Residuals vs Leverage. Systematically check each against the patterns in the troubleshooting guides above [7].

Protocol 2: Addressing Heavy-Tailed Residuals via Transformation This protocol is triggered when a Q-Q plot indicates heavy-tailed residuals [21].

- Diagnosis: Confirm non-normality using the Q-Q plot and consider a statistical test like

shapiro.test(residuals(my_model))(though with large samples, the visual inspection is often sufficient) [22]. - Apply Transformation: Apply a transformation to the dependent variable. Common choices include:

- Refit and Re-diagnose: Refit the linear model using the transformed variable and generate new diagnostic plots to assess improvement [22].

Diagram 1: Workflow for diagnosing and addressing non-normal residuals via transformation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key methodological "reagents" for treating diagnosed problems in regression diagnostics.

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Data Transformation | Stabilizes variance and makes data distribution more normal. Applied to the dependent variable [6] [20] [22]. | Log transformation for positive skew; interpretation of coefficients changes. |

| Polynomial Terms | Captures non-linear relationships in the data, addressing patterns in Residuals vs. Fitted plots [7] [22]. | Adds terms like (X^2) or (X^3) to the model; beware of overfitting. |

| Robust Regression | Provides accurate parameter estimates when outliers or influential points are present, less sensitive to non-normal errors [13] [20]. | Methods include Theil-Sen or Huber regression; useful when data transformation is not desirable. |

| Heteroscedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix (HCCM) | Provides correct standard errors for coefficients even when homoscedasticity is violated, ensuring valid inference [13]. | Also known as "sandwich estimators"; does not change coefficient estimates, only their standard errors. |

| Quantile Regression | Models the relationship between predictors and specific quantiles (e.g., median) of the dependent variable, avoiding the normality assumption entirely [20]. | Provides a more complete view of the relationship, especially when the rate of change differs across the distribution. |

Diagram 2: Logical relationship between common diagnostic plot problems and their corresponding solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Which normality test is most powerful for detecting deviations in the tails of the distribution? The Anderson-Darling test is generally more powerful than the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for detecting deviations in the tails of a distribution, as it gives more weight to the observations in the tails [23] [24]. For a fully specified distribution, it is one of the most powerful tools for detecting departures from normality [23].

2. My dataset has over 5,000 points. Why is the Shapiro-Wilk test giving a warning? The Shapiro-Wilk test is most reliable for small sample sizes. For samples larger than 5,000, the test's underlying calculations can become less accurate, and statistical software (like SciPy in Python) may issue a warning that the p-value may not be reliable [25].

3. What is the key practical difference between the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Lilliefors tests? The standard Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assumes you know the true population mean and standard deviation. The Lilliefors test is a modification that is specifically designed for the more common situation where you have to estimate these parameters from your sample data [26]. Using the standard KS test with estimated parameters makes it overly conservative (less likely to reject the null hypothesis), so the Lilliefors test with its adjusted critical values is the correct choice for testing normality [26].

4. When testing for normality, what is the null hypothesis (H0) for these tests? For the Shapiro-Wilk, Anderson-Darling, and Lilliefors tests, the null hypothesis (H0) is that the data follow a normal distribution [26] [25]. A small p-value (typically < 0.05) provides evidence against the null hypothesis, leading you to reject the assumption of normality [26].

5. My data has many repeated/rounded values, like in clinical chemistry. Which test is less likely to falsely reject normality? The Lilliefors test can be extremely sensitive to the kind of rounded, narrowly distributed data typical in method performance studies. In such cases, a modified version of the Lilliefors test for rounded data is recommended to avoid excessive false positives (indicating non-normality when it may not be warranted) [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Problems

Problem 1: Inconsistent results between different normality tests. It is not uncommon for different tests to yield different results on the same dataset, as they have varying sensitivities to different types of deviations from normality [26].

- Solution: Do not rely on a single test.

- For general purpose use and small samples: Prioritize the Shapiro-Wilk test, which is known to be powerful for a wide range of deviations [25].

- For sensitivity in the tails: Use the Anderson-Darling test, especially if you are concerned about outliers or extreme values [23] [24].

- Always use visual aids: Supplement the tests with a Q-Q plot (quantile-quantile plot). If the data points roughly follow a straight line on the Q-Q plot, it supports the assumption of normality, even if a test is slightly significant [28].

Problem 2: My residuals are non-normal. What are my options for analysis? Finding non-normal residuals is a common experience in statistical practice [13]. You have several avenues to address this, depending on your goal.

- Solution A: Change the data.

- Solution B: Change the model.

- Use non-parametric tests: Switch to tests like the Mann-Whitney U test (instead of t-test) or Kruskal-Wallis H test (instead of ANOVA) that do not assume normality [29] [13].

- Use robust regression methods: Employ statistical techniques that are less sensitive to outliers and non-normality, such as models using Huber loss [30] [13].

- Solution C: Change the inference.

Comparison of Normality Tests

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three tests to help you select the most appropriate one.

Table 1: Comparison of Shapiro-Wilk, Anderson-Darling, and Lilliefors Tests

| Feature | Shapiro-Wilk (SW) | Anderson-Darling (AD) | Lilliefors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Good all-around power for small samples [25] | High power for detecting tail deviations [23] [24] | Corrected for estimated parameters [26] |

| Null Hypothesis (H₀) | Data is from a normal distribution [25] | Data is from a specified distribution (e.g., normal) [24] | Data is from a normal distribution (parameters estimated) [26] |

| Recommended Sample Size | Most reliable for small-to-moderate sizes (e.g., <5000) [25] | Effective across a wide range of sizes [23] | Suitable for various sizes, especially when parameters are unknown [26] |

| Key Limitation | Accuracy can decrease for N > 5000 [25] | Critical values are distribution-specific [24] | Less powerful than AD or SW for some alternatives [26] |

| Sensitivity | Sensitive to a wide range of departures from normality [25] | Particularly sensitive to deviations in the distribution tails [23] [24] | Sensitive to various departures, but may be less so than AD for tails [26] |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting Normality Tests

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for assessing normality using statistical tests, which is a critical step in validating the assumptions of many parametric models.

Diagram 1: Normality Assessment Workflow

When conducting normality tests as part of model validation, the following "research reagents" and tools are essential.

Table 2: Key Resources for Statistical Analysis and Normality Testing

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Provides the computational environment to execute tests and create visualizations. | R: shapiro.test(), nortest::ad.test(). Python: scipy.stats.shapiro, scipy.stats.anderson. |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | A powerful test for assessing normality, especially recommended for small sample sizes [25]. | Use as a first-line test for datasets with fewer than 5,000 observations [25]. |

| Anderson-Darling Test | A powerful test that is particularly sensitive to deviations from normality in the tails of the distribution [23] [24]. | Ideal when the concern is outlier influence or tail behavior in the data. |

| Q-Q Plot (Visual Tool) | A graphical tool for assessing if a dataset follows a theoretical distribution (e.g., normality). Points following a straight line suggest normality [28]. | Always use alongside formal tests for a comprehensive assessment. |

| Robust Regression Methods | Statistical techniques (e.g., using Huber loss) that provide reliable results even when normality or other standard assumptions are violated [30] [13]. | A key alternative when transformations fail or are unsuitable. |

| Non-Parametric Tests | Statistical tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis) that do not assume an underlying normal distribution for the data [29] [13]. | The primary alternative when normality is fundamentally violated and cannot be remedied. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why should I care if my model's residuals are not normally distributed? Many classical statistical tests and inference methods within the general linear model (e.g., t-tests, linear regression, ANOVA) rely on the assumption of normally distributed errors [31]. Violations of this assumption, often signaled by skewness or kurtosis, can lead to biased results, incorrect p-values, and unreliable conclusions [31] [32].

FAQ 2: How can I tell if the extreme values in my dataset are true outliers or just part of a skewed distribution? This is a critical diagnostic step. Outliers are observations that do not follow the pattern of the majority of the data, while skewness is a characteristic of the overall distribution's asymmetry [33] [34]. Use a boxplot to visualize the data; points marked as outliers beyond the whiskers in a roughly symmetrical distribution are likely true outliers. In a clearly skewed distribution, these points may be a natural part of the distribution's tail [34]. Statistical tests and robust methods can help formalize this diagnosis.

FAQ 3: What should I do if my data has high kurtosis? High kurtosis (leptokurtic) indicates heavy tails, meaning a higher probability of extreme values [33] [32]. This can unduly influence model parameters. Solutions include:

- Transformation: Apply transformations (e.g., log, Box-Cox) to reduce the impact of extreme values [32].

- Robust Models: Switch to statistical methods that are less sensitive to outliers, such as robust regression [31] [32].

- Investigate: Determine if the extreme values are data errors. If they are legitimate, your model needs to account for this inherent variability.

FAQ 4: Is it acceptable to automatically remove outliers from my dataset? Automatic removal is generally discouraged [34]. The decision to remove data should be based on subject-matter knowledge. An outlier could be a data entry error, a measurement error, or a genuine, scientifically important observation [34]. Always document any points removed and the justification for their removal.

A Troubleshooting Guide for Non-Normal Patterns

This guide provides a systematic approach to diagnose and address skewness, kurtosis, and outliers in your data.

Step 1: Compute Descriptive Statistics Begin by calculating key statistics for your variable or model residuals. The following table summarizes the measures to compute and their significance [35].

Table 1: Key Diagnostic Statistics and Their Interpretation

| Statistic | Purpose | Interpretation in a Normal Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Measures central tendency. | Close to median and mode. |

| Median | The middle value; robust to outliers. | Close to mean. |

| Skewness | Quantifies asymmetry [33]. | Value near 0. |

| Kurtosis | Measures "tailedness" and peakedness [33]. | Excess kurtosis value near 0 [33]. |

| Standard Deviation | Measures the average spread of data. | Provides context for the distance of potential outliers. |

Step 2: Visualize the Distribution Create a histogram and a boxplot of your data.

- Histogram: Lets you visually assess symmetry and the shape of the distribution.

- Boxplot: Helps identify potential outliers as points that fall beyond the "whiskers," typically calculated as 1.5 * the Interquartile Range (IQR) above the third quartile or below the first quartile [36].

Step 3: Differentiate Patterns and Apply Corrective Actions Use the flowchart below to diagnose the issue and select an appropriate remediation strategy.

Experimental Protocol: Handling Skewed Data with Suspected Outliers

Objective: To normalize a skewed dataset and manage outliers using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method, preparing the data for robust statistical modeling.

Materials & Reagents:

- Statistical Software: R, Python (with Pandas/NumPy/SciPy), SPSS, or similar.

- Dataset: Your research data or model residuals.

- IQR Method: A non-parametric approach for outlier detection [36].

Procedure:

- Calculate Descriptive Statistics: Compute the mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis for your dataset (see Table 1).

- Visual Inspection: Generate a histogram and a boxplot. The boxplot will provide a visual preliminary outlier detection.

- Apply IQR Outlier Filter: a. Calculate the first quartile (Q1, 25th percentile) and the third quartile (Q3, 75th percentile). b. Compute the Interquartile Range (IQR): ( \text{IQR} = Q3 - Q1 ) [36]. c. Establish the lower and upper bounds for "normal" data: * Lower Bound: ( Q1 - 1.5 \times \text{IQR} ) * Upper Bound: ( Q3 + 1.5 \times \text{IQR} ) [36] d. Flag any data point that falls below the lower bound or above the upper bound as a potential outlier.

- Apply Transformation (if needed): For a positively skewed distribution, a log transformation is often effective [36] [33]. For each data point ( x ), compute ( x_{\text{new}} = \log(x) ). For negative skews, reflect the data before applying a log, or consider a square root transformation.

- Re-evaluate: Recompute the descriptive statistics and generate new plots from the transformed data. Assess the improvement in skewness and kurtosis and note which observations were flagged as outliers.

Interpretation of Results: The following table compares quantitative rules of thumb for interpreting skewness and kurtosis coefficients, helping you document the improvement after the protocol [33].

Table 2: Guidelines for Interpreting Skewness and Kurtosis Coefficients

| Measure | Degree | Value | Typical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | Approximate Symmetry | -0.5 to 0.5 | Data is approximately symmetric. |

| Moderate Skew | -1.0 to -0.5 or 0.5 to 1.0 | Slightly skewed distribution. | |

| High Skew | < -1.0 or > 1.0 | Highly skewed distribution. | |

| Excess Kurtosis | Mesokurtic | ≈ 0 | Tails similar to a normal distribution. |

| Leptokurtic | > 0 | Heavy tails and a sharp peak (more outliers). | |

| Platykurtic | < 0 | Light tails and a flat peak (fewer outliers). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I analyze residuals if my model's R-squared seems good? A high R-squared does not guarantee your model meets all statistical assumptions. Residual analysis helps you verify that the model's errors are random and do not contain patterns, which is crucial for the validity of confidence intervals and p-values. It can reveal issues like non-linearity, heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance), and outliers that R-squared alone will not show [37].

Q2: Is it the raw data or the model residuals that need to be normally distributed? For a linear regression model, it is the residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values) that should be normally distributed, not necessarily the raw data itself. A common misconception is testing the raw data for normality, when the core assumption pertains to the model's errors [38].

Q3: My residuals are not perfectly normal. How concerned should I be? The level of concern depends on the severity and your research goals. Mild non-normality may not be a major issue, especially with large sample sizes where the Central Limit Theorem can help. However, severe skewness or heavy tails can affect the accuracy of confidence intervals and p-values. For inference (e.g., hypothesis testing), you should be more concerned than if you are only making predictions [39] [40].

Q4: What are the primary model assumptions checked by residual analysis? Residual analysis primarily checks four key assumptions of linear regression [37]:

- Linearity: The relationship between predictors and the outcome variable is linear.

- Independence: Residuals are independent of each other.

- Homoscedasticity: Residuals have constant variance across all levels of the predicted value.

- Normality: The residuals are approximately normally distributed.

Q5: Can I use a different model if residuals are severely non-normal? Yes. If transformations do not work, you can use models designed for non-normal errors. Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) allow you to specify a non-normal error distribution (e.g., Poisson for count data, Gamma for skewed continuous data) and a link function to handle the non-linearity [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Interpreting Common Residual Plots

Residual plots are powerful diagnostic tools. The table below summarizes common patterns and their implications.

Table 1: Diagnostic Guide for Residual Plots

| Plot Pattern | What You See | What It Suggests | Potential Remedies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Residuals | Points randomly scattered around zero with no discernible pattern [6]. | Model assumptions are likely met. | No action needed. |

| Non-Linearity | A curved pattern (e.g., U-shaped or inverted U) in the Residuals vs. Fitted plot [6]. | The relationship between a predictor and the outcome is not linear. | Add polynomial terms (e.g., X²) for the predictor; Use non-linear regression; Transform the variables. |

| Heteroscedasticity | A funnel or megaphone shape where the spread of residuals changes with the fitted values [37] [6]. | Non-constant variance (heteroscedasticity). This violates the homoscedasticity assumption. | Transform the dependent variable (e.g., log, square root); Use robust standard errors; Fit a Generalized Linear Model (GLM). |

| Outliers & Influential Points | One or a few points that fall far away from the majority of residuals in any plot [37]. | Potential outliers that can unduly influence the model results. | Investigate data points for recording errors; Use robust regression techniques; Calculate influence statistics (Cook's Distance) to assess impact [37]. |

A Workflow for Diagnosing and Addressing Non-Normal Residuals

Follow this structured workflow to systematically diagnose and address issues with your residual distributions.

Research Reagent Solutions: Statistical Tools for Model Diagnosis

Table 2: Essential Statistical Tools for Residual Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R-squared | Goodness-of-fit measure | Unlike R², it penalizes for adding unnecessary predictors, helping select a more parsimonious model [41]. |

| AIC / BIC | Model comparison | Information criteria used to select the "best" model from a set. Lower values are better. AIC is better for prediction, BIC for goodness-of-fit [41]. |

| Cook's Distance | Identify influential points | Measures the influence of a single data point on the entire regression model. Points with large values warrant investigation [37]. |

| Durbin-Watson Test | Check independence | Tests for autocorrelation in the residuals, which is crucial for time-series data [37]. |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | Test for normality | A formal statistical test for normality of the residuals. However, always complement with visual Q-Q plots [38]. |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Test for heteroscedasticity | A formal statistical test for non-constant variance (heteroscedasticity) in the residuals [37]. |

Practical Solutions: Robust Methods for Non-Normal Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My linear regression residuals are not normally distributed. What is the first thing I should check? The first step is not to automatically transform your data, but to verify that a linear model is appropriate for your dependent variable. Linear models require the errors (residuals) to be normally distributed, but this is often unattainable if the dependent variable itself is of a type that violates the model's core assumptions. Check if your dependent variable falls into one of these categories [42]:

- Binary, Categorical, or Ordinal: Such as "yes/no," Likert scale responses, or ranked data.

- Discrete Counts: Especially when bounded at zero and the mean is low (e.g., number of adverse events).

- Proportions or Percentages: Bounded at 0 and 1 (or 0% and 100%).

- Zero-Inflated: Where there is a large spike of values at zero.

If your dependent variable is one of these types, a different model (e.g., logistic, Poisson) is more appropriate than data transformation for a linear model [43] [42].

Q2: I've confirmed my dependent variable is continuous and suitable for a linear model, but the residuals are skewed. When should I use a Log transformation versus a Box-Cox transformation? The choice primarily depends on the presence of zero or negative values in your data [44] [45].

- Use a Log Transformation when your data contains only positive values and exhibits a right-skewed distribution. The log transformation is a specific case of the Box-Cox transformation (where λ = 0) [44].

- Use a Box-Cox Transformation when your data contains only positive values and you need a more flexible approach. Box-Cox automatically finds the optimal power parameter (λ) to achieve the best possible normality [46] [44].

- Use a Yeo-Johnson Transformation when your dataset includes zero or negative values. It is a versatile extension of the Box-Cox that handles these cases effectively [44] [45].

Q3: For my clinical trial data, the central limit theorem suggests my parameter estimates will be normal with a large enough sample. Is checking residuals still necessary? While the Central Limit Theorem does provide robustness for the sampling distribution of the mean with large sample sizes (often >30-50), making hypothesis tests on coefficients fairly reliable, checking residuals remains crucial [43]. Non-normal residuals can still indicate other problems like:

- Heteroscedasticity: Non-constant variance in errors, which can bias standard errors and confidence intervals.

- Model Misspecification: An missing variable, incorrect functional form, or interaction effect that the model has not captured [39] [43]. Therefore, even with a large sample, examining residuals is key to diagnosing a well-specified model.

Q4: After using a transformation, how do I interpret the coefficients of my regression model? Interpretation must be done on the back-transformed scale. A common example is the log transformation [47].

- For a Log-Transformed Dependent Variable: A one-unit increase in the independent variable is associated with a

(exp(β) - 1) * 100%change in the dependent variable, where β is the coefficient from the model. For instance, if β = 0.2, the change is(exp(0.2) - 1) * 100% ≈ 22.1%increase. - General Note: The interpretation shifts from an additive effect on the original scale to a multiplicative effect on the original scale after a log transformation. The specific back-transformation depends on the transformation used.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Normal Residuals in Pre-Clinical Biomarker Data

Problem: Analysis of urinary albumin concentration data (a potential biomarker) reveals strongly right-skewed residuals from a linear model, making confidence intervals for group comparisons unreliable [47].

Investigation & Solution Pathway: The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving non-normal residuals.

Methodology:

- Verify Data Structure: Ensure the dependent variable is a continuous, unbounded measurement. In the case of urinary albumin, the values are positive and continuous, making it a candidate for transformation [47].

- Apply Transformation: Since the data is positive-valued, the Box-Cox transformation is applicable. Using statistical software, compute the optimal λ value that maximizes the log-likelihood, which minimizes the skewness of the resulting data [46].

- Execute Statistical Test: Perform the desired statistical test (e.g., Welch's t-test) on the transformed data. The Welch's t-test is particularly suitable as it does not assume equal variances between groups [47].

- Back-Transform Results: For interpretability, key results like the group means must be back-transformed. For a log transformation (a special case of Box-Cox), the mean of the transformed data corresponds to the geometric mean on the original scale. The back-transformed mean is calculated as

10^mean(log10(data))for common logarithms [47].

Interpretation of Results: In a study of urine albumin, the geometric mean for males was back-transformed to 8.6 μg/mL and for females to 9.9 μg/mL from their log-transformed values. This is more representative of the central tendency for skewed data than the arithmetic mean [47].

Guide 2: Handling Outliers and Zero-Inflated Data in Patient Reported Outcomes

Problem: Data from patient-reported outcome surveys are often zero-inflated (many "no symptom" responses) and contain outliers, leading to a non-normal residual distribution that violates linear model assumptions.

Investigation & Solution Pathway:

Methodology:

- Diagnosis: Visualize the data distribution using a histogram. A zero-inflated distribution will show a large bar at zero. A Q-Q plot will show points deviating from the line at both ends [43].

- Model Selection:

- If the data is a count (e.g., number of episodes), a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a Poisson or Negative Binomial distribution is the most appropriate choice and should be used instead of transformation [42].

- If the data is continuous but plagued with outliers, consider alternative transformations.

- Alternative Transformations:

- Rank Transformation: Replaces each value with its rank (e.g., the smallest value becomes 1). This is excellent for reducing the influence of extreme outliers and is a non-parametric approach [45].

- Binning (Discretization): Groups continuous data into a smaller number of categories or bins. This simplifies the model and handles outliers by placing them into extreme bins. The number of bins can be determined by rules like Sturges' Rule:

k = log2(N) + 1, where N is the sample size [45].

The table below summarizes key transformation techniques to guide your selection.

| Transformation | Formula (Simplified) | Ideal Use Case | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log Transformation | y' = log(y) or y' = log(y + c) for y≥0 |

Right-skewed data with positive values. A special case of Box-Cox (λ=0). | Fails if y ≤ 0. Adding constant (c) can be arbitrary [47] [44]. |

| Box-Cox Transformation | y' = (y^λ - 1)/λ (λ≠0)y' = log(y) (λ=0) |

Right-skewed, strictly positive data. Automatically finds optimal λ for normality [46] [44]. | Cannot handle zero or negative values [44] [45]. |

| Yeo-Johnson Transformation | (Similar to Box-Cox but with cases for non-positive values) |

Flexible; handles both positive and negative values and zeros [44]. | Less interpretable than log. Requires numerical optimization [44]. |

| Reciprocal Transformation | y' = 1 / y |

For right-skewed data where large values are present. Can linearize decreasing relationships [45]. | Not defined for y=0. Sensitive to very small values [45]. |

| Rank Transformation | y' = rank(y) |

Data with severe outliers; non-parametric tests. Reduces influence of extreme values [45]. | Discards information about the original scale and magnitude of differences. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists key computational and statistical "reagents" for implementing data transformation strategies in a research environment.

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Platform for implementing transformations, calculating λ, and assessing normality (e.g., via scipy.stats.boxcox in Python or car::powerTransform in R) [46] [45]. |

| Normality Test (Shapiro-Wilk/Anderson-Darling) | Formal hypothesis tests to assess the normality of residuals. Use with caution, as they are sensitive to large sample sizes [43]. |

| Q-Q (Quantile-Quantile) Plot | A graphical tool for comparing two probability distributions. It is the most intuitive and reliable method to visually assess if residuals deviate from normality [43]. |

| Geometric Mean | The central tendency metric obtained after back-transforming the mean of log-transformed data. More appropriate than the arithmetic mean for skewed distributions [47]. |

| Optimal Lambda (λ) | The parameter estimated by the Box-Cox procedure that defines the power transformation which best normalizes the dataset [46]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers addressing non-normal residuals and outliers in statistical models, with a focus on applications in drug development and scientific research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My data contains several extreme outliers, causing my standard linear regression model to perform poorly. What robust technique should I use? For data with severe outliers, rank-based regression methods are highly effective. These methods use the ranks of observations rather than their raw values, making them much less sensitive to extreme values [48]. In simulation studies, when significant outliers were present, classic linear and semi-parametric models produced estimates greater than 10^5, while rank regression maintained stable performance [48].

Q2: I'm working with noisy data where I want to be sensitive to small errors but not overly influenced by large errors. What approach balances this? The Huber loss function is specifically designed for this scenario. It uses a quadratic loss (like MSE) for small errors within a threshold δ and a linear loss (like MAE) for larger errors, providing a balanced approach [49] [50]. This makes it ideal for financial modeling, time series forecasting, and experimental data with occasional extreme values [50].

Q3: In drug discovery research, our dose-response data often shows extreme responses. What robust method works well for estimating IC50 values? For dose-response curve estimation, penalized beta regression has demonstrated superior performance in handling extreme observations [51]. Implemented in the REAP-2 tool, this method provides more accurate potency estimates (like IC50) and more reliable confidence intervals compared to traditional linear regression approaches [51].

Q4: When should I consider quantile regression instead of mean-based regression methods? Quantile regression is particularly valuable when your outcome distribution is skewed, heavy-tailed, or heterogeneous [52]. Unlike mean-based methods that estimate the average outcome, quantile regression models conditional quantiles (e.g., the median), making it robust to outliers and more informative for skewed distributions common in clinical outcomes [52].

Q5: How do I determine if my robust regression results are significantly different from ordinary least squares results? Statistical tests exist for comparing least squares and robust regression coefficients. Two Wald-like tests using MM-estimators can detect significant differences, helping diagnose whether differences arise from inefficiency of OLS under fat-tailed distributions or from bias induced by outliers [53].

Comparison of Robust Regression Techniques

Table 1: Overview of Key Robust Regression Methods

| Method | Primary Use Case | Outlier Resistance | Implementation | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huber Loss | Moderate outliers, noisy data | Medium | Common in ML libraries | Blends MSE and MAE; smooth gradients for optimization [49] [50] |

| Rank-Based Regression | Severe outliers, non-normal errors | High | Specialized statistical packages | Uses ranks; highly efficient; distribution-free [48] [54] |

| Quantile Regression | Skewed distributions, heterogeneous variance | High | Major statistical software | Models conditional quantiles; complete distributional view [52] |

| MM-Estimators | Multiple outliers, high breakdown point | Very High | R, Python robust packages | Combines high breakdown value with good efficiency [55] [53] |

| Beta Regression | Dose-response, proportional data (0-1 range) | Medium-High | R (mgcv package) | Ideal for bounded responses; handles extreme observations well [51] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Simulation Studies

| Method | Normal Errors (No Outliers) | Normal Errors (With Outliers) | Non-Normal Errors | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least Squares | Optimal (BLUE) | Highly biased | Inefficient | Low |

| Huber Loss M-Estimation | Nearly efficient | Moderately biased | Robust | Low-Medium |

| Rank-Based Methods | ~95% efficiency | Minimal bias | Highly efficient | Medium |

| MM-Estimation | High efficiency | Very minimal bias | Highly efficient | Medium-High |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Huber Loss Regression

Objective: Fit a robust regression model using Huber loss to handle moderate outliers.

Materials and Software:

- R with

statspackage or Python withsklearn.linear_model.HuberRegressor - Dataset with continuous outcome and predictors

- Computational environment for model fitting

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Standardize all continuous predictors to mean 0 and variance 1

- Parameter Selection: Choose δ threshold parameter (typically 1.345 for 95% asymptotic efficiency under normal errors)

- Model Fitting: Implement iterative reweighted least squares algorithm:

- Initialize weights equally

- Calculate residuals from current fit

- Update weights: wi = 1 if |ri| ≤ δ, else wi = δ/|ri|

- Refit weighted least squares

- Repeat until coefficient convergence

- Model Validation: Check robustness by comparing with OLS results; examine weight distribution

Troubleshooting:

- If convergence issues occur: Reduce step size in weight updates

- If results remain sensitive to outliers: Consider smaller δ value or alternative methods

Protocol 2: Rank-Based Regression Implementation

Objective: Perform rank-based analysis for data with severe outliers or non-normal errors.

Materials and Software:

- R with

Rfitpackage or specialized robust regression software - Dataset with continuous outcome

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Check for tied values in response variable

- Score Function Selection: Choose appropriate score function (Wilcoxon, sign scores, or normal scores)

- Model Estimation:

- Convert observed responses to ranks: R(yi) = rank of yi among all observations

- Estimate parameters by minimizing dispersion of rank residuals

- Use numerical optimization techniques for estimation

- Inference: Calculate standard errors using appropriate asymptotic formulas

- Diagnostics: Check using rank-based residuals

Troubleshooting:

- For tied values: Use averaging approaches for ranks

- For small sample sizes: Consider permutation tests rather than asymptotic inference

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Decision Workflow for Selecting Robust Regression Techniques

Figure 2: Huber Loss Function Decision Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Robust Regression Analysis

| Tool/Package | Application | Key Functions | Implementation Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| R: MASS Package | Huber M-estimation | rlm() for robust linear models |

R Statistical Software |

| R: quantreg Package | Quantile regression | rq() for quantile regression |

R Statistical Software |

| R: Rfit Package | Rank-based estimation | rfit() for rank-based regression |

R Statistical Software |

| R: mgcv Package | Penalized beta regression | betar() for beta regression |

R Statistical Software |

| Python: sklearn | Huber loss implementation | HuberRegressor class |

Python |

| REAP-2 Shiny App | Dose-response analysis | Web-based beta regression | Online tool [51] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My linear regression residuals are not normal. What should I do? The first step is to diagnose the specific problem. You should check if the issue is related to the distribution of your outcome variable or a mis-specified model (e.g., missing a key variable or using an incorrect functional form) [39]. Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) are a direct solution, as they allow you to model data from the exponential family (e.g., binomial, Poisson, gamma) and handle non-constant variance [39].

Q2: Do my raw data need to be normally distributed? Not necessarily. For many models, including linear regression and ANOVA, the critical assumption is that the residuals (the differences between the observed and predicted values) are approximately normally distributed, not the raw data itself [56].

Q3: What are my options if transformations don't work? If transforming your data does not resolve the issue, you have several robust alternatives:

- Generalized Linear Models (GLMs): Link your outcome variable to the linear predictor using a non-identity link function (e.g., log, logit) and specify an appropriate error distribution [39].

- Non-Parametric Tests: Use tests like Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis that do not rely on distributional assumptions, though they often have less statistical power [56].

- Robust Inference Methods: For linear models, you can use heteroskedasticity-consistent (HC) standard errors (like HC3 or HC4) or bootstrap methods (like wild bootstrap) to obtain valid confidence intervals even when errors are non-normal or heteroskedastic [31].

Q4: Is a large sample size a fix for non-normal residuals? With a large sample size, the sampling distribution of parameters (like the regression coefficients) may approach normality due to the Central Limit Theorem. This can make confidence intervals and p-values more reliable, even if the residuals are not perfectly normal [39]. However, this does not address other issues like bias from a mis-specified model or heteroskedasticity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Addressing Non-Normal Residuals

The workflow below provides a structured path for investigating and resolving issues with non-normal residuals.

Step 1: Visual and Statistical Diagnosis

Before choosing a solution, properly diagnose the problem using both visual and statistical tests [56].

Visual Checks:

- Q-Q Plot (Quantile-Quantile Plot): Plot the residuals against the quantiles of a normal distribution. Data from a normal distribution will fall approximately along the straight reference line. Deviation from the line indicates non-normality [56].

- Histogram: Plot a frequency distribution (histogram) of the residuals and overlay a normal curve. This helps visualize skewness (asymmetry) or kurtosis (heavy or light tails) [56].

- Residuals vs. Fitted Plot: Plot the residuals against the model's predicted values. This is crucial for detecting other problems like non-linearity (a curved pattern) or heteroskedasticity (when the spread of residuals changes with the fitted values) [57] [39].

Statistical Tests: Common normality tests include Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, and D'Agostino-Pearson. A significant p-value (typically < 0.05) provides evidence that the residuals are not normally distributed [56].

Note: With large sample sizes, these tests can detect very slight, practically insignificant deviations from normality. Therefore, always prioritize visual inspection for a practical assessment [56].

Step 2: Select and Implement an Alternative Framework

The following table compares common solutions for non-normal residuals. GLMs are often the most principled approach for specific data types.

| Method | Best For / Data Type | Key Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Transformation | Moderate skewness; non-constant variance. | Applies a function (e.g., log, square root) to the outcome variable. | Simple to implement and can address both non-normality and heteroskedasticity [56]. |

| Generalized Linear Model (GLM) | Specific data types: Counts, proportions, positive-skewed continuous data. | Links the mean of the outcome to a linear predictor via a link function (e.g., log, logit) and uses a non-normal error distribution [39]. | Models the data according to its natural scale and distribution, providing more accurate inference [39]. |

| Non-Parametric Tests | When no distributional assumptions can be made; ordinal data. | Uses ranks of the data rather than raw values (e.g., Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis). | Does not rely on any distributional assumptions [56]. |

| Robust Standard Errors | When the model is correct but errors show heteroskedasticity. | Calculates standard errors for OLS coefficients that are consistent despite heteroskedasticity (e.g., HC3, HC4). | Allows you to keep the original model and scale while improving the validity of confidence intervals and p-values [31]. |

| Bootstrap Methods | Complex situations where theoretical formulas are unreliable. | Resamples the data to empirically approximate the sampling distribution of parameters. | A flexible, simulation-based method for obtaining confidence intervals without strict distributional assumptions [31]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key statistical "reagents" for diagnosing and modeling non-normal data.

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Q-Q Plot | A visual diagnostic tool to assess if a set of residuals deviates from a normal distribution. Points following the diagonal line suggest normality [56]. |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | A formal statistical test for normality. A low p-value indicates significant evidence that the data are not normally distributed [56]. |

| Link Function (in GLMs) | A function that connects the mean of the outcome variable to the linear predictor model. Examples: logit for probabilities, log for counts [39]. |

| HC3 Standard Errors | A type of robust standard error used in linear regression to provide valid inference when the assumption of constant error variance (homoskedasticity) is violated [31]. |

| Wild Bootstrap | A resampling technique particularly effective for creating confidence intervals in regression with heteroskedastic errors, without assuming normality [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a GLM for Count Data

This protocol outlines the steps to replace a standard linear regression with a Poisson GLM when your outcome variable is a count (e.g., number of cells, occurrences of an event).

Background: Standard linear regression assumes normally distributed residuals. When the outcome is a count, this assumption is often violated because counts are non-negative integers and their variance typically depends on the mean. A Poisson GLM directly models these properties [39].

Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Specify the model. For a Poisson GLM, the outcome Y is assumed to follow a Poisson distribution. The natural logarithm of its expected value (μ) is modeled as a linear combination of the predictors:

log(μ) = β₀ + β₁X₁ + ... + βₖXₖ. This is known as the log link function. - Parameter Estimation: Estimate the coefficients (βs) using the method of Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), which finds the parameter values that make the observed data most probable.

- Model Checking:

- Check for Overdispersion: A key check for Poisson models is to see if the residual deviance is much larger than the residual degrees of freedom. If so, the data is "overdispersed," meaning the variance is greater than the mean. In this case, a Quasi-Poisson or Negative Binomial GLM is more appropriate.

- Examine Residuals: Use diagnostic plots specific to GLMs (e.g., deviance residuals vs. fitted values) to check for patterns that suggest a poor fit.

Handling Influential Points and Outliers Without Compromising Validity

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between an outlier and an influential point? An outlier is an observation that has a response value (Y-value) that is very different from the value predicted by your model [58]. An influential point, on the other hand, is an observation that has a particularly unusual combination of predictor values (X-values). Its presence can significantly alter the model's parameters and conclusions [58]. A data point can be an outlier, influential, both, or neither.

I've identified a potential outlier. Should I remove it? Not necessarily. Removal is appropriate only if the point is a clear error (e.g., a data entry mistake or a measurement instrument failure) [59]. If the outlier is a genuine, though rare, occurrence, removing it would misrepresent the true population. In such cases, other methods like Winsorization (capping extreme values) or using robust statistical models are recommended [59].

My model violates the normality assumption due to a few outliers. What should I do? Several strategies can help: