Beyond Statistical Significance: A Practical Guide to Equivalence Testing for Model Performance in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to equivalence testing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Beyond Statistical Significance: A Practical Guide to Equivalence Testing for Model Performance in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to equivalence testing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Moving beyond traditional null hypothesis significance testing, we explore the foundational concepts of proving similarity rather than difference. The content covers core methodological approaches like the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure and Bayesian methods, alongside practical implementation strategies for comparing machine learning classifiers and regression models. We address common pitfalls in model selection, the impact of model misspecification, and optimization techniques such as model averaging. The guide also delves into validation frameworks and comparative analyses of frequentist versus Bayesian paradigms, equipping practitioners with the statistical tools to robustly demonstrate model equivalence in clinical and biomedical applications.

Why Prove Sameness? The Critical Shift from Difference to Equivalence in Biomedical Models

In scientific research, particularly in fields like drug development and machine learning, a common and critical error is to interpret a non-significant result from a null hypothesis significance test (NHST) as evidence for the absence of an effect or difference. This misinterpretation stems from a fundamental logical flaw in the structure of traditional hypothesis testing. A failure to reject a null hypothesis (e.g., obtaining a p-value > 0.05) merely indicates that the data do not provide strong enough evidence to conclude a difference exists; it does not affirm that the two groups are equivalent [1] [2]. This distinction is paramount when the research goal is to positively demonstrate similarity, such as proving a new generic drug delivers the same physiological effect as its brand-name counterpart, or that a simplified machine learning model performs as well as a more complex one.

The persistence of this fallacy is a significant contributor to the ongoing replication crisis in many scientific fields, as it leads to underpowered studies and unsubstantiated claims of "no difference" [3]. This article will delineate the limitations of traditional NHST for equivalence testing, introduce robust statistical methodologies designed specifically for proving equivalence, and provide practical guidance for researchers and drug development professionals on their correct application.

How Traditional Null Hypothesis Significance Testing Fails Equivalence

The Logical Structure and Its Shortcomings

Traditional NHST is designed to test for the presence of a difference. Its structure is ill-suited for testing equivalence.

Standard NHST (Difference Testing): The null hypothesis (H₀) states that there is no difference between groups (the "nil" null hypothesis). A statistically significant p-value allows researchers to reject H₀ and conclude that a difference exists [1]. However, a non-significant p-value (p > α) only leads to a failure to reject H₀. This is an inconclusive result; it does not allow the researcher to accept H₀ and claim the groups are identical [2]. As one analysis notes, "a ‘not guilty’ verdict ... does not necessarily imply that the jury believes the accused is innocent. Rather, it means that the evidence presented was insufficient to conclude the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt" [1].

The Goal of Equivalence Testing: Here, the researcher wants to positively confirm the absence of a meaningful difference. This requires an inversion of the usual hypotheses. In equivalence testing, the null hypothesis becomes that a meaningful difference does exist, and the goal is to reject this hypothesis in favor of the alternative, which states that the difference is smaller than a pre-defined, clinically or practically important threshold [1] [2] [4].

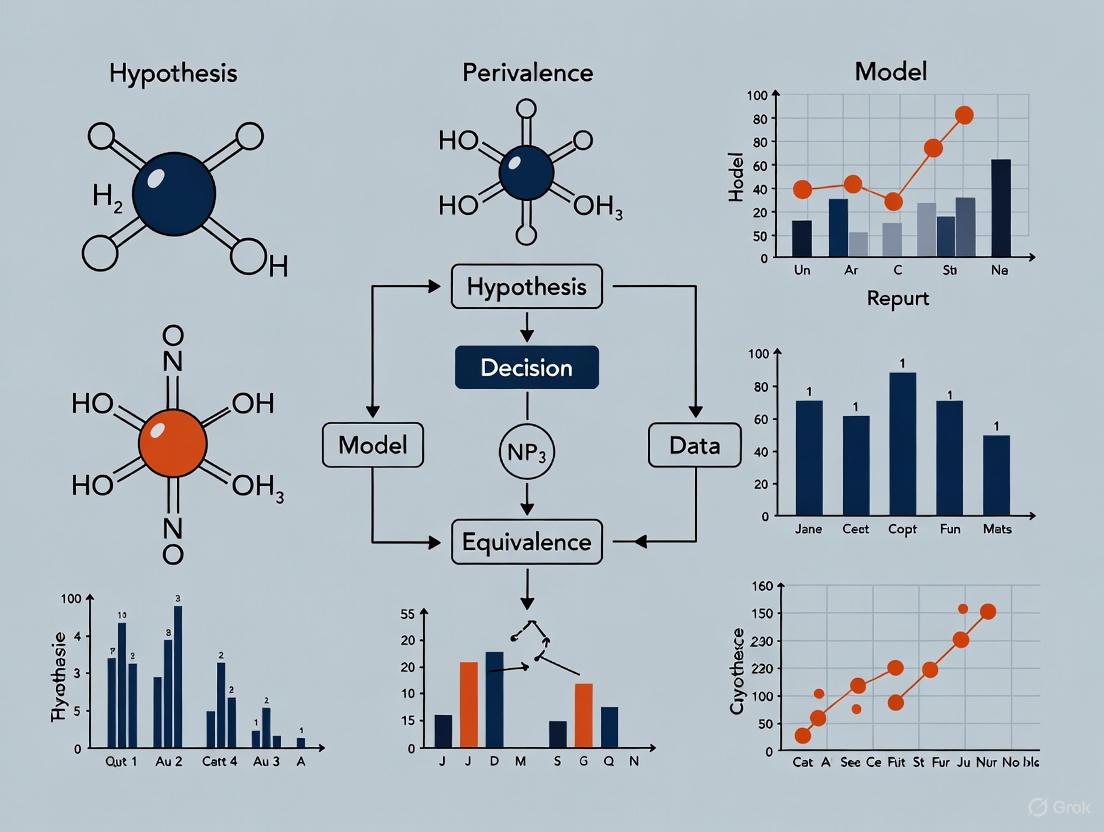

The confusion arising from traditional NHST is visually and logically summarized in the diagram below.

The Perils of Misinterpretation in Practice

Relying on a non-significant NHST result to claim equivalence is fraught with risk. The most common danger is an underpowered study [3]. A small sample size or highly variable data can easily lead to a large p-value, even if a substantial, clinically important difference truly exists. Concluding equivalence based on this result could lead to grave consequences, such as approving a less effective drug or deploying an inferior analytical model.

Furthermore, in correlational fields like the social sciences, an effect of zero is often improbable due to numerous latent variables (the "crud factor") [2]. Therefore, rejecting a nil null hypothesis is not a rigorous test, as it is likely to succeed even for theoretically uninteresting associations. This undermines the validity of claims built on this foundation.

A Robust Alternative: Equivalence Testing and the TOST Procedure

The Core Framework of Equivalence Testing

Equivalence testing directly addresses the logical flaw of NHST by inverting the null and alternative hypotheses. The core of this framework is the definition of an equivalence interval (EI), also known as the region of practical equivalence (ROPE) [1] [2]. The EI is a range of values, centered on zero, that represents differences deemed too small to be of any practical or clinical importance. Establishing this interval a priori is a critical step that requires domain-specific knowledge [2].

The formal hypotheses for a two-sided equivalence test are [1]:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The true difference between the groups is outside the equivalence interval (i.e., Δ ≤ -EI or Δ ≥ EI).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The true difference between the groups is inside the equivalence interval (i.e., -EI < Δ < EI).

The goal of the statistical test is to reject H₀, thereby providing statistical evidence that the difference is negligibly small and the groups are practically equivalent.

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) Methodology

The most common and straightforward method for conducting an equivalence test is the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure [2] [4]. Instead of one test, it employs two simultaneous one-sided tests to rule out effects at both ends of the equivalence interval.

The procedure tests two sets of hypotheses:

- Test 1: H₀₁: Δ ≤ -EI vs. H₁₁: Δ > -EI

- Test 2: H₀₂: Δ ≥ EI vs. H₁₂: Δ < EI

Equivalence is concluded at a significance level α only if both null hypotheses are rejected [1]. This is equivalent to showing that the entire (1 - 2α)% confidence interval for the difference lies completely within the equivalence interval [-EI, EI] [4]. The workflow and decision logic of TOST is illustrated below.

Practical Application: A Case Study in Drug Development

Scenario: Establishing Bioequivalence

A canonical application of equivalence testing is in pharmacokinetics for establishing bioequivalence between a generic and a brand-name drug [4]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA require evidence that the generic product has equivalent absorption to the brand-name product, typically measured by parameters like AUC (area under the curve) and Cmax (maximum concentration) [4].

Suppose a study aims to prove that a new synthetic fiber has equivalent breaking strength to a natural fiber. The researchers define, based on engineering requirements, that a mean difference in strength within ±20 kg is practically irrelevant. The equivalence interval is thus set at [-20, 20] [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Design: A randomized, controlled study is conducted.

- Data Collection: 15 samples of natural fiber and 12 samples of synthetic fiber are tested for breaking strength.

- Descriptive Statistics:

- Natural fiber: Mean = 530 kg, StDev = 40 kg

- Synthetic fiber: Mean = 513 kg, StDev = 20 kg

- Observed difference: 17 kg

- Analysis: A two-sample equivalence test (TOST procedure) is performed with an equivalence interval of ±20 kg and α = 0.05.

Results and Interpretation: The test yields two p-values: one for testing against the lower bound (p = 0.007) and one for testing against the upper bound (p = 0.253) [1]. Because only one of the two tests is statistically significant (p < 0.05), the null hypothesis of non-equivalence cannot be rejected. The 95% confidence interval for the difference (-8.36, 32.36) extends beyond the upper equivalence limit, visually confirming this conclusion [1]. In this case, the researchers correctly determine that equivalence has not been demonstrated, despite the observed difference of 17 kg being within the ±20 kg window, due to the uncertainty (confidence interval) around the estimate.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Equivalence Studies

Table 1: Key Reagents and Tools for Equivalence Testing in Experimental Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Executes TOST procedures, calculates confidence intervals, and generates plots. | Essential for all quantitative fields (e.g., pharmacology, data science) for data analysis. |

| Equivalence Interval (EI) | Defines the margin of practically insignificant difference; the critical benchmark for the test. | Required for any equivalence study design (e.g., setting Δ for bioequivalence in drug studies). |

| Power Analysis Software | Determines the minimum sample size required to detect equivalence with high probability. | Used in the design phase of experiments (clinical trials, model validation) to avoid underpowered studies. |

| Selenium WebDriver | Automates web browser interaction for consistent, repeated performance measurement. | Used in data science for A/B testing webpage load times or UI interactions [5]. |

| MLxtend Library | Provides implementations of specialized statistical tests for comparing machine learning models. | Used in data science for pairedttest5x2cv to compare algorithm performance robustly [6]. |

Comparing Statistical Approaches: NHST vs. Equivalence Testing

The following table provides a consolidated comparison of the two methodologies, highlighting their distinct goals, interpretations, and risks.

Table 2: A Comparative Overview of NHST and Equivalence Testing

| Feature | Traditional NHST (for Difference) | Equivalence Testing (TOST) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Detect the presence of a difference. | Confirm the absence of a meaningful difference. |

| Null Hypothesis (H₀) | No difference exists (Effect = 0). | A meaningful difference exists (Effect ≤ -EI or Effect ≥ EI). |

| Interpretation of a Significant Result (p < α) | Reject H₀; conclude a difference exists. | Reject H₀; conclude equivalence (difference is within [-EI, EI]). |

| Interpretation of a Non-Significant Result (p ≥ α) | Fail to reject H₀; cannot conclude a difference exists. (Inconclusive) | Fail to reject H₀; cannot conclude equivalence. (Inconclusive) |

| Key Risk | Mistaking "no significant difference" for "evidence of no difference" (Type II error). | Failing to claim equivalence when it is true (often due to low power). |

| Confidence Interval Interpretation | If the 95% CI includes 0, the result is not statistically significant. | If the 90% CI* falls entirely within [-EI, EI], equivalence is concluded. |

| Common Application | Exploratory research: Discovering if an effect is present. | Validation research: Proving two treatments/products are similar. |

Note: A 90% confidence interval is used in TOST to correspond to a two-test procedure each at α=0.05, maintaining an overall Type I error rate of 5%.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Bayesian Alternatives and Multivariate Extensions

While the frequentist TOST procedure is the most established method, modern alternatives offer additional flexibility. The Bayesian Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE) allows researchers to make direct probability statements about the parameter lying within the equivalence interval, which can be more intuitive than the dichotomous reject/fail-to-reject decision of NHST [7].

Furthermore, many real-world problems, such as demonstrating bioequivalence for multiple pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC, Cmax, tmax) simultaneously, require multivariate equivalence testing [4]. Standard TOST procedures can become overly conservative when applied to multiple correlated outcomes. Recent methodological research focuses on developing adjusted TOST procedures (e.g., the multivariate α*-TOST) that account for the dependence between outcomes to improve statistical power while maintaining the prescribed Type I error rate [4].

The Critical Role of Power and Sample Size

A fundamental tenet of any statistical analysis, especially equivalence testing, is ensuring the study has adequate power. Power is the probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false. In equivalence testing, this translates to the likelihood of successfully demonstrating equivalence when the groups are truly equivalent [1]. An underpowered equivalence study is highly likely to fail to demonstrate equivalence, even if it truly exists, wasting resources and potentially leading to the abandonment of promising treatments or technologies. Therefore, a power analysis conducted during the study design phase to determine the necessary sample size is not just good practice—it is essential for a meaningful and reliable conclusion.

In the rigorous fields of preclinical research and drug development, the traditional statistical question of "Is there an effect?" is being superseded by the more nuanced and practical inquiry: "Is the effect large enough to matter?" This paradigm shift moves research beyond mere statistical significance toward assessing practical relevance, a critical consideration when deciding which drug candidates warrant progression to costly clinical trials. Two methodological frameworks have emerged to address this question: the Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE), a Bayesian approach, and the Smallest Effect Size of Interest (SESOI), often utilized within frequentist equivalence testing. Both concepts share a common goal—to define a range of effect sizes that are considered practically or clinically irrelevant—but they operationalize this goal through different statistical philosophies and decision rules. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, detailing their protocols, applications, and performance in the context of hypothesis testing model performance equivalence research.

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE)

The ROPE is a Bayesian statistical concept that defines an interval around a null value, typically zero, where parameter values are considered practically equivalent to the null. Unlike significance testing which examines differences from a point null, the ROPE framework acknowledges that trivially small effects, even if technically non-zero, are scientifically meaningless [8].

- Core Principle: The fundamental question in ROPE analysis is whether the entire credible interval of a parameter's posterior distribution lies outside the ROPE (indicating a meaningful effect), inside the ROPE (indicating practical equivalence to the null), or overlaps the ROPE (indicating uncertainty) [8].

- Decision Rule: The standard "HDI+ROPE decision rule" assesses the percentage of the Highest Density Interval (HDI)—a Bayesian credible interval—that falls within the ROPE. A common practice is to use the 89% or 95% HDI for this assessment [8].

Smallest Effect Size of Interest (SESOI)

The SESOI, also known as the Minimum Effect of Interest (MEI) or Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID), is the smallest true effect size that a researcher deems theoretically meaningful or clinically valuable in the context of their research [9] [10] [11].

- Core Principle: The SESOI is established prior to data collection and is used to design studies with sufficient statistical power to detect this specific effect. It reframes the alternative hypothesis ((H_1)) from a vague "effect exists" to a specific "effect is at least as large as the SESOI" [10].

- Anchor-Based Methods: One established approach for determining the SESOI, particularly in clinical and health research, uses an "anchor," often a global rating of change question. This method quantifies the smallest change in an outcome measure that individuals consider meaningful enough in their subjective experience to rate themselves as "feeling different" [9].

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Protocols

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of ROPE and SESOI, highlighting their philosophical and procedural differences.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of ROPE and SESOI

| Feature | Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE) | Smallest Effect Size of Interest (SESOI) |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Paradigm | Bayesian Estimation [8] | Frequentist Equivalence Testing (e.g., TOST) [12] |

| Primary Question | Is the most credible parameter range practically equivalent to the null? [8] | Can we reject effect sizes as large or larger than the SESOI? [9] |

| Key Input | A pre-defined equivalence region around the null value. | A single pre-defined minimum interesting effect size. |

| Core Output/Decision Metric | Percentage of the posterior distribution or Highest Density Interval (HDI) within the ROPE [8]. | p-values from two one-sided tests (TOST) against the SESOI bounds [12]. |

| Interval Used | 89% or 95% Highest Density Interval (HDI) [8]. | 90% Confidence Interval (CI) for a 5% alpha level [12]. |

| Interpretation of Result | Accept Null: Full HDI inside ROPE.Reject Null: Full HDI outside ROPE.Uncertain: HDI overlaps ROPE [8]. | Equivalent: 90% CI falls entirely within [-SESOI, +SESOI].Not Equivalent: CI includes values outside the bounds. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for ROPE

The ROPE procedure is implemented within a Bayesian estimation framework, typically involving the following workflow.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define the ROPE Range: The most critical step is to specify the upper and lower bounds of the ROPE based on domain knowledge. For a standardized mean difference (e.g., Cohen's d), a default range of -0.1 to 0.1 is sometimes used, representing a negligible effect size according to Cohen's conventions [8]. In preclinical drug development, this range should be grounded in the Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID), representing the smallest treatment benefit that would justify the costs and risks of a new therapy [11].

- Specify the Prior Distribution: Elicit a prior distribution that represents plausible parameter values before seeing the data. In the absence of strong prior information, a broad or weakly informative prior (e.g., a Cauchy or normal distribution with a large variance) can be used [8].

- Compute the Posterior Distribution: Using computational methods (e.g., Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling in software like

Stan,JAGS, or thebayestestRpackage in R), compute the posterior distribution of the parameter of interest (e.g., a mean difference or regression coefficient). This distribution combines the prior with the likelihood of the observed data [8]. - Calculate the Highest Density Interval (HDI): From the posterior distribution, compute the 89% or 95% HDI. This is the interval that spans the most credible values of the parameter and has the property that all points inside the interval have a higher probability density than points outside it [8].

- Apply the HDI+ROPE Decision Rule:

- If the entire HDI falls within the ROPE, conclude that the parameter is practically equivalent to the null and "accept" the null for practical purposes.

- If the entire HDI falls outside the ROPE, reject the null value and conclude a practically significant effect.

- If the HDI overlaps the ROPE, the data are deemed inconclusive, and no firm decision can be made [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SESOI via Equivalence Testing

The SESOI is typically deployed using frequentist equivalence testing, most commonly the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure. The workflow is as follows.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define the SESOI (Δ): Before data collection, rigorously define the smallest effect size that would be considered practically or clinically important. In research involving subjective experience, anchor-based methods can be used. This involves correlating changes in the primary outcome with an external "anchor," such as a patient's global rating of change, to identify the threshold for a subjectively experienced difference [9].

- Formulate Hypotheses: The TOST procedure reformulates the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The true effect is outside the equivalence interval (i.e., Effect ≤ -Δ or Effect ≥ Δ).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The true effect is within the equivalence interval (i.e., -Δ < Effect < Δ) [12].

- Perform Two One-Sided Tests: Conduct two separate statistical tests.

- Test 1: Check if the effect is significantly greater than the lower bound (-Δ).

- Test 2: Check if the effect is significantly less than the upper bound (+Δ).

- Each test is performed at a significance level of α (e.g., 0.05) [12].

- Construct a Confidence Interval: As a more intuitive equivalent to TOST, compute a 90% Confidence Interval for the effect size. Using a 90% CI (rather than 95%) corresponds to the two tests each being run at α = 0.05, controlling the overall Type I error rate at 5% [12].

- Decision Rule:

- If the entire 90% CI lies within the interval [-Δ, +Δ], you reject the null hypothesis and conclude equivalence (i.e., the effect is practically insignificant).

- If the 90% CI extends outside the [-Δ, +Δ] interval, you fail to conclude equivalence [12].

Performance and Application in Preclinical Research

A key application of these methods is in improving the reliability of preclinical animal research, which serves as a funnel for clinical trials. Simulation studies have compared research pipelines based on traditional Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST), SESOI-based equivalence testing, and Bayesian decision criteria like ROPE [11].

Table 2: Simulated Performance in a Preclinical Research Pipeline (Exploratory + Confirmatory Study)

| Research Pipeline | False Discovery Rate (FDR) | False Omission Rate (FOR) | Key Assumptions & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional NHST | Higher (Baseline) | Lower | Uses two-sample t-test at α=0.025. Prone to declaring trivial effects as "significant." [11] |

| SESOI (Equivalence Test) | Reduced | Comparable | Uses TOST procedure. Explicitly incorporates MCID, filtering out trivial effects and reducing false positives. [11] |

| ROPE (Bayesian) | Reduced | Comparable | Uses 95% HDI and ROPE based on MCID. Provides similar FDR reduction as SESOI/TOST while allowing for incorporation of prior knowledge. [11] |

Supporting Experimental Data from Simulation Studies:

- A 2023 simulation study modeling preclinical research (exploratory animal study followed by a confirmatory study) found that pipelines incorporating the SESOI or ROPE substantially reduced the False Discovery Rate (FDR) compared to a pipeline based solely on traditional NHST (p-values) [11].

- This FDR reduction was achieved without a substantial increase in the False Omission Rate (FOR), meaning truly effective treatments were not incorrectly filtered out at a higher rate [11].

- The study concluded that both Bayesian statistical decision criteria (like ROPE) and methods that explicitly incorporate the SESOI can improve the reliability of preclinical animal research by reducing the number of false-positive findings that transition to costly confirmatory studies [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of these statistical methods relies on both conceptual understanding and the use of robust software tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Equivalence Testing

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Analysis Package | Performs Bayesian estimation, computes posterior distributions, HDIs, and ROPE percentages. | bayestestR R package [8] |

| Equivalence Testing Package | Conducts TOST procedures for various statistical tests (t-tests, correlations, meta-analyses). | TOSTER R package (or equivalent in Python, SAS) [12] |

| Power Analysis Software | Calculates required sample size to achieve sufficient statistical power for a given SESOI/ROPE. | BEST R package for Bayesian power analysis; pwr or TOSTER for frequentist power analysis [12] |

| Meta-Analysis Tool | Synthesizes effect sizes across multiple studies to establish evidence-based SESOI/ROPE ranges. | metafor R package; RevMan (Cochrane) |

| Anchor-Based Analysis Scripts | Custom scripts to analyze the relationship between an anchor variable (e.g., patient global rating) and the primary outcome to define the SESOI. | Custom R/Python/SAS scripts implementing methods from Anvari et al. [9] |

Critical Considerations for Implementation

- Sensitivity to Scale: The correct interpretation of the ROPE is highly dependent on the scale of the parameters. A change in the unit of measurement (e.g., from days to years in a growth model) can drastically alter the proportion of the posterior distribution inside the ROPE, leading to different conclusions. It is crucial to define the ROPE in a contextually meaningful way for your specific data [8].

- Impact of Multicollinearity: In models with multiple correlated parameters (multicollinearity), the joint posterior distributions can be misleading. The ROPE procedure applied to univariate marginal distributions may be invalid under strong correlations, as the probabilities are conditional on independence. In such cases, checking for pairwise correlations and investigating more sophisticated methods like projection predictive variable selection is advised [8].

- Power and Sample Size: For both SESOI and ROPE, a priori sample size justification is critical. Power analysis for TOST is based on closed-form functions and is computationally fast. Power analysis for ROPE can be performed via simulation (e.g., using the

BESTpackage), which is more computationally intensive but allows for the incorporation of prior distributions [12]. - Choice of Interval: The ROPE procedure commonly uses a 95% HDI for decision-making, while the TOST procedure uses a 90% CI. This makes the frequentist equivalence test more powerful by default, as it uses a narrower interval. However, one could also choose to use a 90% HDI for the ROPE decision rule to make the procedures more comparable [12].

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical development, demonstrating equivalence—rather than superiority—is a fundamental requirement across multiple critical domains. Equivalence testing provides a structured statistical framework for proving that a new product, method, or model performs comparably to an established standard. For researchers and drug development professionals, this methodology is indispensable in three key applications: approving generic drugs through bioequivalence studies, validating novel clinical trial models and sites, and establishing analytical method equivalence for quality control.

This guide objectively compares the performance of established regulatory pathways, emerging in-silico techniques, and advanced statistical tools used in equivalence research. The comparative analysis is framed within the broader thesis of hypothesis testing model performance, examining how varied methodological approaches meet the stringent evidence requirements of regulatory science. The following sections provide a detailed comparison of experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and the essential toolkit for implementing these approaches in practice.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Equivalence Applications

The table below summarizes the core performance metrics, regulatory contexts, and primary statistical outputs for the three major applications of equivalence testing in drug development.

Table 1: Performance and Application Comparison of Equivalence Testing Frameworks

| Application Area | Primary Objective | Key Performance Metrics & Statistical Outputs | Regulatory/Standardization Framework | Typical Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic Drug Bioequivalence | Demonstrate therapeutic equivalence to a Reference Listed Drug (RLD) [13] [14]. | • 90% Confidence Intervals for PK parameters (AUC, C~max~) within 80.00%-125.00% [13].• P-value for statistical testing [15]. | Hatch-Waxman Act, FDA ANDA pathway [13] [14]. | Clinical study in healthy volunteers or patients. |

| Clinical Trial Model & Site Validation | Ensure operational quality and reliability of trial sites and in-silico models [16] [17]. | • Factor correlations (e.g., from Confirmatory Factor Analysis) [18].• R² statistics from regression models [18].• Site Performance Scores (e.g., CT-SPM domains) [16]. | ICH guidelines, V3+ framework for digital measures [18]. | Multicenter study for site metrics; computational validation for in-silico models [16] [17]. |

| Analytical Method Equivalence | Prove that a new or modified analytical procedure yields equivalent results to an established method [19]. | • Mean, Standard Deviation, Pooled Standard Deviation [19].• Equivalence intervals based on pre-defined acceptance criteria [19]. | ICH Q2(R2), ICH Q14, USP <1010> [19]. | Laboratory study comparing method outputs for the same samples. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Equivalence Methodologies

Protocol for Establishing Bioequivalence

The gold-standard protocol for establishing bioequivalence for a generic oral drug is a single-dose, two-treatment, two-period, two-sequence crossover study in healthy human subjects [13].

- Subject Selection & Randomization: A cohort of healthy volunteers is recruited and randomly assigned to one of two sequence groups. The sample size is justified by a power calculation to ensure high probability (often 80-90%) of demonstrating equivalence if it exists.

- Dosing and Blood Collection: In the first period, one group receives the generic Test product (T), and the other receives the Reference Listed Drug (R). After a washout period (typically >5 half-lives of the drug) sufficient to eliminate the first dose, the groups switch treatments in the second period.

- Bioanalysis: Serial blood samples are collected from each subject over a time period adequate to define the concentration-time profile. Plasma concentrations of the active pharmaceutical ingredient are determined using a validated analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

- Pharmacokinetic (PK) Analysis: The concentration-time data for each subject are used to calculate key PK parameters, including:

- AUC~0-t~: Area under the concentration-time curve from zero to the last measurable time point, representing total exposure.

- AUC~0-∞~: Area under the curve from zero to infinity.

- C~max~: The maximum observed concentration.

- Statistical Analysis for Equivalence: An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is performed on the log-transformed AUC and C~max~ data. The critical step is the calculation of the 90% confidence intervals (CI) for the geometric mean ratio (T/R) of these parameters. Bioequivalence is concluded if the 90% CIs for both AUC and C~max~ fall entirely within the acceptance range of 80.00% to 125.00% [13].

Protocol for Validating a Virtual Cohort for an In-Silico Trial

The validation of a computationally generated virtual cohort against a real-world patient cohort involves assessing how well the virtual population reflects the real one across key characteristics [17].

- Cohort Definition and Generation: Define the target patient population for the in-silico trial (e.g., patients with moderate aortic stenosis). A virtual cohort is then generated using computational models, often based on real clinical data, to simulate individuals with the same distribution of clinical parameters (e.g., age, anatomy, disease severity).

- Real-World Dataset Selection: Identify a suitable real-world dataset (e.g., from a clinical registry or a previous clinical trial) that represents the target population.

- Comparison of Distributions: Statistically compare the distributions of predefined key parameters between the virtual and real cohorts. These parameters are chosen based on their clinical relevance to the trial's context and often include:

- Demographics: Age, sex, weight.

- Disease-Specific Measures: Anatomical dimensions, lab values, functional status.

- Comorbidities.

- Statistical Validation:

- Use Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to estimate the correlation between the underlying constructs (e.g., "disease severity") measured in the virtual and real cohorts. A high factor correlation indicates strong construct validity [18].

- Apply multiple linear regression (MLR) with several real-world parameters as independent variables and the corresponding virtual parameter as the dependent variable. A high adjusted R² statistic indicates that the virtual cohort's characteristics can be well-predicted by the real-world data patterns [18].

- Assess the similarity of distributions using statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov) and visualization tools (e.g., Q-Q plots).

- Acceptance Criteria: The virtual cohort is considered validated for use in an in-silico trial when the statistical analyses (e.g., factor correlations from CFA) demonstrate a pre-specified threshold for agreement, showing it is a sufficiently accurate representation of the real-world population for the intended purpose [17].

Protocol for Demonstrating Analytical Method Equivalence

This protocol is used to demonstrate that a new, modified, or alternative analytical method (e.g., for drug potency assay) is equivalent to an existing, validated method [19].

- Experimental Design: Select a representative set of samples (e.g., drug product batches with varying potency) that cover the expected specification range. The same set of samples is analyzed using both the established (Reference) method and the proposed (Test) method.

- Execution and Data Collection: The analysis should be performed under conditions of intermediate precision, meaning different analysts, on different days, and potentially using different instruments, to capture expected routine variability. Each sample is typically tested in multiple replicates by each method.

- Data Analysis and Comparison:

- Descriptive Statistics: Calculate the mean and standard deviation for the results generated by each method for each sample [19].

- Comparison of Means and Variability: Use statistical tools (e.g., a t-test for means, an F-test for variances) or pre-set acceptance criteria (e.g., the difference between means for each sample is less than a pre-defined value) to compare the outputs of the two methods.

- Equivalence Evaluation: The primary criterion for equivalence is that the results from the two methods lead to the same "accept/reject" decision for the sample, based on the product's specification limits [19]. A simple approach is to compare the data against approved specifications and historical data to ensure consistency in decision-making [19].

- Advanced Statistical Tools: For more complex methods, equivalence can be formally evaluated using an equivalence interval approach, as discussed in USP <1010>, where the confidence interval for the difference between methods must fall entirely within a pre-defined equivalence margin [19].

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

Bioequivalence Study Workflow

Hypothesis Testing Logic for Model Equivalence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Equivalence Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Equivalence Research |

|---|---|

| Validated Bioanalytical Method (e.g., LC-MS/MS) | Quantifies active drug concentrations in biological matrices (e.g., plasma) for bioequivalence studies with high specificity and sensitivity [13]. |

| Reference Listed Drug (RLD) | The approved brand-name drug product that serves as the clinical and bioequivalence benchmark for the development of a generic drug [13] [14]. |

| Certified Reference Standard (API) | A highly characterized sample of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient with known purity, essential for accurate calibration of analytical methods in bioanalysis and quality control [19]. |

| Statistical Analysis Software (e.g., R, SAS) | Performs complex statistical calculations required for equivalence testing, including ANOVA for bioequivalence, Confirmatory Factor Analysis for model validation, and equivalence interval testing [16] [17] [18]. |

| In-Silico Trial Platform / Virtual Cohort Generator | Creates simulated patient populations for computational trials, allowing for model validation against real-world data before use in regulatory decision-making [17]. |

| Electronic Data Capture (EDC) System | Securely captures and manages clinical trial data from investigational sites in real-time, providing the high-quality, traceable data necessary for robust statistical analysis [20]. |

In the realm of hypothesis testing for model performance evaluation, a fundamental shift occurs when moving from traditional superiority trials to equivalence and non-inferiority research designs. Traditional hypothesis testing, often termed "superiority testing," employs a null hypothesis (H₀) that states no difference exists between treatments or models, while the alternative hypothesis (H₁) states that a significant difference does exist [21] [22]. The conventional statistical approach focuses on rejecting H₀ to demonstrate that one intervention is superior to another [23]. However, this framework becomes inadequate when the research objective shifts to demonstrating that a new model performs "as well as" or "not unacceptably worse than" an established standard—a common scenario in diagnostic tool validation, algorithm comparison, and therapeutic development.

Equivalence and non-inferiority testing represent a formal inversion of this traditional hypothesis structure, requiring researchers to pre-specify a margin (Δ) that defines the maximum clinically or practically acceptable difference between comparators [23] [24]. This margin represents the largest difference in effect that would still be considered indicative of equivalence or non-inferiority, and its determination should be informed by both empirical evidence and clinical judgment [23]. Within this framework, the statistical goal changes from proving difference to demonstrating similarity within predetermined bounds, making these approaches particularly valuable when evaluating new methodologies that offer secondary advantages such as reduced cost, decreased complexity, or improved safety profiles [23] [24].

Fundamental Concepts: Margin-Based Hypothesis Testing

The Equivalence and Non-Inferiority Margin (Δ)

The cornerstone of both equivalence and non-inferiority testing is the pre-specification of the margin (Δ), which quantifies the largest difference between interventions that would still be considered clinically or practically irrelevant [23]. This margin must be established prior to data collection and should be justified based on clinical reasoning, historical data, and stakeholder input [23] [24]. For example, when comparing a new computational diagnostic method to an established standard, researchers might define Δ as the minimum difference in accuracy that would change patient management decisions. The determination of this margin has profound implications for trial design, sample size requirements, and the ultimate interpretation of results [24].

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines both recommend that a 95% two-sided confidence interval typically be used for assessing non-inferiority [24]. This means that not only must the point estimate of the difference between treatments favor equivalence or non-inferiority, but the entire confidence interval must lie within the pre-specified boundary to support the conclusion. This stringent requirement ensures that with high confidence (usually 95%), the new intervention is not substantially worse than the standard comparison [24].

Distinguishing Between Equivalence and Non-Inferiority Designs

While equivalence and non-inferiority trials share methodological similarities, their objectives and hypothesis structures differ fundamentally:

Equivalence Trials: Aim to demonstrate that a new intervention is neither superior nor inferior to a comparator, with the difference between them lying within a predefined equivalence range (-Δ to +Δ) [23]. These are appropriate when the goal is to show that two interventions are clinically interchangeable.

Non-Inferiority Trials: Seek to confirm that a new intervention is not unacceptably worse than a comparator, with the difference not exceeding a predefined non-inferiority margin (+Δ) in the direction favoring the standard [23] [24]. These designs are commonly employed when a new treatment offers secondary advantages (e.g., reduced cost, improved safety, or easier administration) that might justify its use even with a minor efficacy trade-off.

The fundamental rationale for these designs stems from a limitation of traditional null hypothesis significance testing: the inability to confirm the absence of a meaningful effect [23] [25]. In conventional testing, failing to reject the null hypothesis does not prove equivalence, as this outcome could simply reflect insufficient statistical power [23]. Equivalence and non-inferiority testing directly address this limitation by providing a formal framework for concluding that differences are small enough to be unimportant.

Hypothesis Formulation: The Structural Inversion

Traditional Superiority Testing Framework

In conventional hypothesis testing for superiority, the structure follows a well-established pattern [21] [22]:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): No difference exists between interventions (e.g., θ₁ = θ₂ or θ₁ - θ₂ = 0)

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): A difference exists between interventions (e.g., θ₁ ≠ θ₂ or θ₁ - θ₂ ≠ 0)

The analysis aims to reject H₀ in favor of H₁, typically using a threshold of p < 0.05 to declare statistical significance [21] [26]. Within this framework, failing to reject H₀ only indicates insufficient evidence for a difference, not evidence of equivalence [23] [25].

Equivalence Testing Framework

Equivalence testing formally inverts the traditional hypothesis structure [23] [25]:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The difference between interventions is greater than the equivalence margin (e.g., |θ₁ - θ₂| ≥ Δ)

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The difference between interventions is less than the equivalence margin (e.g., |θ₁ - θ₂| < Δ)

In this structure, rejecting H₀ provides statistical support for equivalence, as it indicates that the observed difference is smaller than the predefined margin of clinical indifference. The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure operationalizes this approach by testing whether the confidence interval for the difference lies entirely within the equivalence bounds (-Δ to +Δ) [25].

Non-Inferiority Testing Framework

Non-inferiority testing employs a one-sided version of this inverted structure [23] [24]:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The new intervention is inferior to the comparator by at least the margin Δ (e.g., θ₁ - θ₂ ≤ -Δ)

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The new intervention is not inferior to the comparator (e.g., θ₁ - θ₂ > -Δ)

Here, rejecting H₀ supports the conclusion that the new intervention is not unacceptably worse than the standard. This framework is particularly useful when the new intervention offers practical advantages and some efficacy trade-off might be acceptable.

Table 1: Comparison of Hypothesis Testing Frameworks

| Testing Framework | Null Hypothesis (H₀) | Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) | Interpretation of Rejecting H₀ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superiority | No difference exists: θ₁ - θ₂ = 0 | A difference exists: θ₁ - θ₂ ≠ 0 | Interventions are statistically different |

| Equivalence | Difference exceeds margin: |θ₁ - θ₂| ≥ Δ | Difference within margin: |θ₁ - θ₂| < Δ | Interventions are clinically equivalent |

| Non-Inferiority | New is inferior: θ₁ - θ₂ ≤ -Δ | New is not inferior: θ₁ - θ₂ > -Δ | New intervention is not unacceptably worse |

Methodological Implementation and Experimental Protocols

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) Procedure for Equivalence

The TOST procedure provides a straightforward method for testing equivalence [25]. This approach involves performing two separate one-sided tests against the lower and upper equivalence bounds:

- Test 1: H₀¹: θ₁ - θ₂ ≤ -Δ vs. H₁¹: θ₁ - θ₂ > -Δ

- Test 2: H₀²: θ₁ - θ₂ ≥ Δ vs. H₁²: θ₁ - θ₂ < Δ

If both null hypotheses can be rejected at the prescribed significance level (typically α = 0.05), then equivalence can be concluded. The TOST procedure is conceptually equivalent to determining whether a 90% confidence interval for the difference falls entirely within the equivalence range (-Δ, Δ) [25]. For a 95% confidence level, corresponding to a two-sided test with α = 0.05, a 90% confidence interval is used because each one-sided test is performed at α = 0.05.

Statistical Analysis Plan for Non-Inferiority Trials

Non-inferiority testing follows a structured analytical approach [23] [24]:

Pre-specification of the non-inferiority margin (Δ): This margin should be justified based on clinical reasoning, historical data, and regulatory guidelines.

Primary analysis using confidence intervals: A 95% confidence interval for the difference between interventions is constructed. If the entire interval lies above -Δ, non-inferiority is established.

Supplementary superiority testing: If non-inferiority is confirmed, additional testing may determine whether the new intervention is actually superior to the standard.

Sensitivity analyses: Both intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol analyses should be conducted, as protocol violations can artificially make treatments appear more similar in non-inferiority trials [24].

The diagram below illustrates the key decision points in designing, executing, and interpreting equivalence and non-inferiority trials:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for equivalence and non-inferiority trials

Analytical Considerations for Different Data Types

The appropriate statistical test for equivalence or non-inferiority depends on the type of data being analyzed [27]:

- Continuous data: T-tests (or non-parametric alternatives like Wilcoxon tests for non-normal distributions)

- Binary data: Chi-square tests or tests for proportions

- Time-to-event data: Survival analysis methods such as Cox proportional hazards models

- Multiple groups: Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post-hoc comparisons

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Different Variable Types in Equivalence/Non-Inferiority Research

| Variable Type | Example | Appropriate Statistical Test | Equivalence Bound Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Accuracy scores, Processing times | TOST with t-test, Mann-Whitney U test | Raw difference (e.g., 5% accuracy) or standardized effect (e.g., Cohen's d = 0.3) |

| Binary | Success/Failure rates, Positive/Negative classifications | TOST with z-test for proportions, Chi-square test | Absolute risk difference (e.g., 10%) or relative risk ratio |

| Ordinal | Likert scales, Severity ratings | TOST with Wilcoxon signed-rank test | Raw score difference or percentile ranks |

| Time-to-event | Survival analysis, Time to failure | Cox proportional hazards model | Hazard ratio bounds (e.g., 0.8 to 1.25) |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Successful implementation of equivalence and non-inferiority studies requires careful attention to several methodological components that constitute the essential research toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Equivalence and Non-Inferiority Studies

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Equivalence/Non-Inferiority Margin (Δ) | Defines the maximum acceptable difference between interventions | Should be established a priori based on clinical relevance, historical data, and stakeholder input [23] [24] |

| Sample Size Calculation | Ensures adequate statistical power | Power analysis for equivalence tests requires larger samples than conventional tests for the same effect size [25] |

| Statistical Software | Performs specialized equivalence testing | R (equivalence package), SPSS, SAS, and specialized online calculators can implement TOST procedures [25] |

| Historical Control Database | Provides context for margin justification | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of previous studies establish the expected effect of standard interventions [24] |

| Randomization Protocol | Minimizes selection bias | Should follow established randomization procedures appropriate for the research context [23] |

| Blinding Procedures | Reduces performance and detection bias | Particularly important in subjective outcome assessments to prevent biased results [23] |

Interpretation of Results and Common Pitfalls

Interpreting Confidence Intervals in Margin-Based Testing

The interpretation of equivalence and non-inferiority trials relies heavily on confidence interval analysis rather than simple p-value thresholds [24]. The following scenarios illustrate possible outcomes:

- Established equivalence: The entire 90% confidence interval lies within the equivalence bounds (-Δ to +Δ)

- Established non-inferiority: The entire 95% confidence interval lies above the non-inferiority bound (-Δ)

- Inconclusive results: The confidence interval crosses the equivalence or non-inferiority boundary

- Established superiority: In non-inferiority testing, the confidence interval may lie entirely above zero, indicating the new intervention is actually superior

A particularly counterintuitive scenario can occur when a treatment shows traditional statistical superiority while also demonstrating equivalence, or when a treatment shows traditional statistical inferiority while still meeting non-inferiority criteria [23] [24]. This highlights the distinction between statistical significance and clinical relevance—a treatment meeting non-inferiority criteria may be statistically inferior to the standard, but not to a degree considered clinically important [24].

Threats to Validity and Methodological Challenges

Several unique methodological challenges threaten the validity of equivalence and non-inferiority studies [23]:

- The "biocreep" phenomenon: Sequential non-inferiority trials with marginally effective interventions can gradually erode treatment standards over time

- Poor intervention delivery: Inadequate implementation of either intervention can reduce observable differences, creating false equivalence

- Rhetorical "spin" in reporting: Inconclusive findings may be misinterpreted or misrepresented as demonstrating equivalence

- Assay sensitivity: The inability of a trial to distinguish effective from ineffective treatments undermines non-inferiority conclusions

- Historical constancy assumption: Non-inferiority trials assume that the effect of the standard treatment versus placebo would be similar in the current trial population as in historical trials

To mitigate these threats, researchers should [23] [24]:

- Choose a conservative, well-established comparator as the standard

- Justify the equivalence margin with empirical evidence and clinical rationale

- Report both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses

- Clearly acknowledge the limitations of historical comparisons

- Avoid overinterpreting inconclusive results

Equivalence and non-inferiority testing represent a fundamental restructuring of traditional hypothesis testing that enables researchers to formally assess similarity rather than difference. By pre-specifying a clinically meaningful margin (Δ) and inverting the conventional null hypothesis, these approaches provide a methodological framework for demonstrating that a new intervention, model, or diagnostic tool performs sufficiently similarly to an established standard to be considered interchangeable or acceptable. The proper implementation of these designs requires careful attention to margin justification, appropriate statistical procedures like the TOST method, and nuanced interpretation of confidence intervals in relation to pre-defined boundaries. As comparative performance evaluation becomes increasingly important across scientific domains, the principled application of equivalence and non-inferiority testing will continue to grow in relevance and importance for researchers, clinicians, and drug development professionals.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing TOST, Bayesian Tests, and Model Averaging

In scientific research, particularly in fields like drug development and computational modeling, there is an increasing need to demonstrate that two methods or models produce equivalent results rather than to prove that one is superior to the other. Traditional null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is designed to detect differences, making it fundamentally unsuited for this task. A non-significant result in NHST (p > 0.05) is often misinterpreted as evidence of no effect or equivalence, but this is a logical fallacy; absence of evidence is not evidence of absence [25] [2]. The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure addresses this need directly, providing a statistically rigorous framework for testing equivalence.

TOST allows researchers to test whether an effect size—such as the difference between a model's output and real-world measurements—is within a pre-specified range considered practically insignificant [28]. This guide details the TOST procedure's theoretical foundation, provides step-by-step protocols for implementation, and illustrates its application through concrete examples, empowering researchers to robustly validate model means against experimental or observational data.

Conceptual Foundation of the TOST Procedure

The Logic of Two One-Sided Tests

The TOST procedure operates on a straightforward yet powerful logic: it tests whether the true effect size is outside a pre-defined equivalence range, and if both tests show the effect is inside this range, equivalence can be concluded [28]. The procedure specifies an equivalence margin (( \Delta )), which represents the smallest effect size of practical interest. For a difference between two means, this margin is a positive value, creating an interval from (-\Delta) to (+\Delta) within which effects are deemed practically equivalent to zero [2].

The TOST procedure tests two complementary one-sided hypotheses [28] [29]:

- First one-sided test: ( H{01}: \theta \leq -\Delta ) vs ( H{a1}: \theta > -\Delta )

- Second one-sided test: ( H{02}: \theta \geq \Delta ) vs ( H{a2}: \theta < \Delta )

If both null hypotheses are rejected, there is statistical evidence to conclude that (-\Delta < \theta < \Delta), and the two means are considered practically equivalent [28]. The overall p-value for the equivalence test is the larger of the two p-values from the one-sided tests [30].

Defining the Equivalence Margin

The most critical step in planning a TOST analysis is specifying the equivalence margin (( \Delta )). This margin must be determined based on domain knowledge, practical considerations, or regulatory guidelines, not statistical criteria [2] [30]. In bioequivalence studies, regulatory agencies often provide specific margins [28]. In psychological research, bounds might be set based on standardized effect sizes (e.g., Cohen's d = 0.3 or 0.5) [25]. For comparing model means against real measurements, the margin should reflect the maximum acceptable difference that would still render the model outputs practically useful.

TOST Workflow and Statistical Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete TOST workflow, from study design to interpretation of results.

Relationship Between TOST and Confidence Intervals

An intuitive way to perform and interpret TOST is through confidence intervals. If the 90% confidence interval for the difference between means falls entirely within the equivalence bounds ([-\Delta, \Delta]), then the TOST procedure will conclude equivalence at the 5% significance level [28] [30]. This relationship provides a valuable visual representation of the test results, as illustrated in the scenarios below.

Statistical Formulations for Different Study Designs

The TOST procedure can be adapted to various experimental designs, each with specific statistical formulations. The following table summarizes the key parameters for common testing scenarios.

Table 1: TOST Formulations for Different Experimental Designs

| Design Type | Test Statistic Formulas | Degrees of Freedom | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Sample | ( tL = \frac{\overline{M} - \mu0 + \Delta}{s/\sqrt{n}} ), ( tU = \frac{\overline{M} - \mu0 - \Delta}{s/\sqrt{n}} ) | ( n-1 ) | Compares sample mean to theoretical value ( \mu_0 ) |

| Independent Samples | ( tL = \frac{(\overline{M1} - \overline{M2}) + \Delta}{sp\sqrt{\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2}}} ),( tU = \frac{(\overline{M1} - \overline{M2}) - \Delta}{sp\sqrt{\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2}}} ) | ( n1 + n2 - 2 ) | Uses pooled standard deviation ( s_p ) |

| Paired Samples | ( tL = \frac{\overline{Md} + \Delta}{sd/\sqrt{n}} ), ( tU = \frac{\overline{Md} - \Delta}{sd/\sqrt{n}} ) | ( n-1 ) | Uses mean of differences ( \overline{Md} ) and their SD ( sd ) |

For independent samples with potential variance heterogeneity, the Welch-Satterthwaite adjustment for degrees of freedom is recommended: ( df = \frac{(s1^2/n1 + s2^2/n2)^2}{(s1^2/n1)^2/(n1-1) + (s2^2/n2)^2/(n2-1)} ) [31].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Practical Implementation Guide

Step 1: Define the Equivalence Margin

Establish the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI) before data collection. For example:

- In bioequivalence studies: ( \Delta ) might represent 20% difference in bioavailability [28]

- In model validation: ( \Delta ) could be the maximum acceptable difference between predicted and observed values that still has practical utility [32]

- Using standardized effect sizes: Cohen's d = 0.2, 0.5, or 0.8 for small, medium, or large effects, converted to raw scale using known variability [25]

Step 2: Determine Sample Size

Conduct a power analysis to ensure adequate sensitivity. Power analysis for TOST requires:

- Significance level (typically α = 0.05)

- Desired power (typically 80% or 90%)

- Expected effect size (often assumed to be 0 for perfect equivalence)

- Equivalence margin

- Standard deviation estimate

For example, with ( \Delta = 0.5 ), SD = 1, α = 0.05, and 80% power, approximately 34 participants per group are needed for an independent t-test [25]. Specialized software like R's TOSTER package or simulation approaches in Excel can calculate precise sample size requirements [31].

Step 3: Execute the TOST Procedure

- Collect data according to the experimental design

- Calculate descriptive statistics: means, standard deviations, sample sizes

- Compute test statistics for both one-sided tests using the appropriate formula from Table 1

- Determine p-values using the t-distribution with appropriate degrees of freedom

- Compare both p-values to the significance level (α = 0.05)

Step 4: Interpret Results

- If both p-values < 0.05: Conclude statistical equivalence

- If one or both p-values ≥ 0.05: Cannot conclude equivalence

- Report the 90% confidence interval for the difference and assess whether it falls completely within the equivalence bounds [28] [30]

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Tools for TOST Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R with TOSTER package | Comprehensive equivalence testing | Free download |

| SAS PROC TTEST | Equivalence testing with FDA acceptance | Licensed | |

| Python statsmodels | General statistical modeling | Free download | |

| Specialized Spreadsheets | Lakens' TOST spreadsheet | Simple t-test equivalence | Download template |

| Real Statistics Excel Resource | TOST examples and formulas | Website resource [30] | |

| Calculation Aids | G*Power | Sample size calculation | Free download |

| Online SMD calculators | Effect size conversion | Web-based tools |

Comparative Analysis: TOST vs. Traditional Testing

Philosophical and Practical Differences

TOST represents a paradigm shift from traditional hypothesis testing, with fundamental differences in logic and application as shown in the following comparison.

Table 3: TOST vs. Traditional Null Hypothesis Significance Testing

| Feature | Traditional NHST | TOST Equivalence Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis | ( H_0 ): No effect (( \theta = 0 )) | ( H_0 ): Effect is outside equivalence bounds (( \theta \leq -\Delta ) or ( \theta \geq \Delta )) |

| Alternative Hypothesis | ( H_a ): There is an effect (( \theta \neq 0 )) | ( H_a ): Effect is within equivalence bounds (( -\Delta < \theta < \Delta )) |

| Goal | Detect a difference | Establish similarity |

| p-value Interpretation | Small p: evidence for an effect | Small p: evidence for equivalence |

| Interpretation of Nonsignificance | Cannot reject null (inconclusive) | Cannot claim equivalence |

| Proper Conclusion | "There is a difference" or "We failed to find a difference" | "The effects are equivalent" or "We failed to demonstrate equivalence" |

Advantages of TOST for Model Comparison

TOST offers several distinct advantages for researchers comparing model means:

Avoids Misinterpretation of Non-Significance: Traditional NHST failing to reject ( H_0 ) is often incorrectly interpreted as evidence for no effect. TOST provides a statistically sound framework for actually testing this proposition [28] [25].

Aligns with Confidence Interval Interpretation: TOST conclusions are consistent with confidence interval-based reasoning, making results more intuitive [28].

Regulatory Acceptance: TOST is widely accepted by regulatory agencies like the FDA for bioequivalence trials, establishing its credibility [28] [31].

Flexibility: The procedure can be applied to various statistical parameters including means, correlations, regression coefficients, and more [28] [33].

Practical Application Example

Case Study: Validating Soil Water Content Model

Consider a researcher comparing soil water content measurements from a mathematical model against field observations [32]. The equivalence margin is set at Δ = 0.05, representing the maximum acceptable difference for practical applications.

After collecting seven paired measurements, the analysis proceeds as follows:

Calculate descriptive statistics:

- Mean difference: ( \overline{M_d} = 0.0157 )

- Standard deviation of differences: ( s_d = 0.0278 )

- Sample size: n = 7

Compute test statistics (using paired TOST formulas):

- ( t_L = \frac{0.0157 + 0.05}{0.0278/\sqrt{7}} = \frac{0.0657}{0.0105} = 6.257 )

- ( t_U = \frac{0.0157 - 0.05}{0.0278/\sqrt{7}} = \frac{-0.0343}{0.0105} = -3.267 )

Determine p-values (df = 6):

- p-value (lower test) = 0.0004

- p-value (upper test) = 0.0085

Interpret results:

- Both p-values (0.0004 and 0.0085) are less than 0.05

- Conclusion: The model outputs and field measurements are statistically equivalent within the ±0.05 margin

The 90% confidence interval for the mean difference is [-0.007, 0.038], which falls completely within the equivalence bounds of [-0.05, 0.05], visually confirming equivalence.

The TOST procedure provides a statistically rigorous framework for establishing equivalence between model means and experimental measurements. By testing against a pre-specified margin of practical significance, TOST addresses a critical limitation of traditional hypothesis testing and enables researchers to make meaningful claims about similarity rather than just differences. As model validation becomes increasingly important across scientific disciplines, mastery of equivalence testing techniques like TOST will empower researchers to demonstrate that their models produce outputs equivalent to real-world observations within practically acceptable limits.

In biomedical research and drug development, the traditional paradigm of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is often inadequate for demonstrating the absence of meaningful effects. NHST focuses on rejecting a precise null hypothesis of exactly zero difference, which becomes increasingly likely with large sample sizes even for trivial effects that lack practical significance [34]. This limitation has fueled interest in equivalence testing, which flips the conventional statistical perspective by testing an interval hypothesis to demonstrate that differences between treatments or processes are small enough to be practically unimportant [35].

Within this framework, Bayesian equivalence testing offers a probabilistic approach that aligns more naturally with scientific reasoning. By combining the Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE) with Bayesian credible intervals, researchers can make direct probabilistic statements about parameter values falling within a range of practical equivalence [8] [7]. This approach provides several advantages for drug development professionals and researchers, including the ability to incorporate prior knowledge, intuitive interpretation of results, and freedom from fixed-sample-size constraints [34] [7].

Fundamental Concepts: ROPE and Credible Intervals

The Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE)

The ROPE is a critical concept in Bayesian equivalence testing. It defines a range of parameter values around a null point (typically zero) that are considered practically equivalent to the null value for scientific or clinical purposes [8]. For example, when comparing two formulations of a drug, a difference in bioavailability of ±5% might be considered clinically irrelevant, thus defining the ROPE boundaries.

The determination of ROPE boundaries should be based on domain knowledge, clinical relevance, and risk assessment [36] [8]. In pharmaceutical applications, higher-risk scenarios typically warrant narrower equivalence margins. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter <1033> recommends a risk-based approach where high-risk parameters might use equivalence margins of 5-10%, medium-risk 11-25%, and low-risk 26-50% [36].

Bayesian Credible Intervals

In Bayesian statistics, a credible interval (CI) provides a probability statement about parameter values given the observed data. A 95% credible interval contains the true parameter value with 95% probability, which aligns more intuitively with how researchers often misinterpret frequentist confidence intervals [34] [8].

The Highest Density Interval (HDI) is a special type of credible interval that contains the most credible values—those with highest posterior density. The 95% HDI encompasses 95% of the posterior distribution while spanning the narrowest possible parameter range [8] [12].

Methodological Framework: The ROPE Decision Rule

The core methodology of Bayesian equivalence testing involves comparing the credible interval of a parameter to its predefined ROPE. The decision rule follows these principles [8]:

- If the 95% HDI falls completely within the ROPE, the parameter is accepted as practically equivalent to the null value.

- If the 95% HDI falls completely outside the ROPE, the parameter is rejected as practically different.

- If the 95% HDI overlaps the ROPE, evidence is indeterminate regarding practical equivalence.

An alternative approach uses the full posterior distribution rather than the HDI, calculating the proportion of the posterior distribution within the ROPE. In this case, if more than 97.5% of the posterior falls within the ROPE, practical equivalence is accepted; if less than 2.5%, it is rejected [8].

The diagram below illustrates this decision-making workflow:

Comparative Analysis: Bayesian vs. Frequentist Approaches

The Frequentist TOST Procedure

The predominant frequentist method for equivalence testing is the Two One-Sided Test (TOST) procedure. TOST operates by testing two simultaneous hypotheses: whether the parameter is significantly greater than the lower equivalence bound and significantly less than the upper equivalence bound [36] [37].

In TOST, the null hypothesis states that differences between means are at least as large as the equivalence margin (non-equivalence), while the alternative hypothesis states that differences are smaller than the equivalence margin (equivalence) [35] [37]. Equivalence is established if the 90% confidence interval for the parameter difference falls entirely within the equivalence bounds [12].

Philosophical and Practical Differences

The table below summarizes key differences between Bayesian and frequentist approaches to equivalence testing:

| Aspect | Bayesian ROPE Approach | Frequentist TOST Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretation | Direct probability statements about parameters (e.g., "95% probability that δ is within ROPE") [8] | Long-run error rate control (e.g., "95% confidence that interval contains true parameter") [34] |

| Basis for Decision | Position of HDI relative to ROPE or proportion of posterior in ROPE [8] | Position of confidence interval relative to equivalence bounds [37] |

| Interval Used | 95% Highest Density Interval [8] | 90% Confidence Interval [12] |

| Prior Information | Can incorporate prior knowledge through prior distributions [38] | No incorporation of prior knowledge [34] |

| Sample Size Flexibility | No minimum sample size requirement; applicable to small samples [7] | Requires sufficient sample size for adequate power [37] |

| Multi-group Extensions | Naturally extends to multiple comparisons using joint posterior distributions [38] | Requires complex adjustments for multiplicity [38] |

| Stopping Rules | Independent of testing intentions; allows optional stopping [34] | Results depend on sampling plan; violates likelihood principle [34] |

Practical Implementation and Considerations

Defining the ROPE

The appropriate ROPE specification depends on the parameter scale and research context. For standardized effect sizes, a ROPE of -0.1 to 0.1 is commonly recommended, representing a negligible effect according to Cohen's conventions [8]. For raw parameters, the ROPE should be defined as a fraction of the response variable's standard deviation (e.g., ±0.1×SDʸ) [8].

In pharmaceutical applications, regulatory guidelines and risk-based approaches should inform ROPE selection. For critical quality attributes with significant clinical impact, narrower equivalence margins are warranted [36] [37].

Sensitivity to Parameter Scale

The ROPE procedure is sensitive to the scale of parameters, requiring careful consideration of measurement units. A coefficient expressed in different units (e.g., days vs. years) will have different magnitudes and thus different relationships to the same ROPE [8]. This underscores the importance of thoughtful parameterization and ROPE specification aligned with practical significance in the specific research context.

Addressing Multicollinearity

When parameters exhibit strong correlations, the ROPE procedure based on univariate marginal distributions may be inappropriate. Correlations can distort the joint parameter distribution, potentially inflating or deflating the apparent evidence for equivalence [8]. In such cases, multivariate approaches or projection predictive methods should be considered [8].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Bayesian equivalence testing has found numerous applications in drug development and manufacturing:

Process Comparability Studies

During biopharmaceutical development and scale-up, equivalence tests assess the impact of changes in manufacturing processes, equipment, or facilities on product quality attributes [37]. The Bayesian approach is particularly valuable for comparing multiple production sites simultaneously, providing a more nuanced understanding of similarity than frequentist methods [38].

Analytical Method Validation

The United States Pharmacopeia recommends equivalence testing over significance testing for demonstrating that analytical methods conform to expectations [36]. Bayesian methods offer natural probabilistic statements about method equivalence that align with quality-by-design principles.

Bioequivalence Assessment

While traditional bioequivalence studies rely on frequentist TOST procedures, Bayesian approaches provide enhanced flexibility for adaptive designs and incorporating historical data [34] [38].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential components for implementing Bayesian equivalence testing in pharmaceutical research:

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Bayesian model estimation and visualization | R with packages (bayestestR, rstanarm, BEST) or Stan for custom models [8] |

| Prior Distributions | Incorporate existing knowledge while controlling influence | Non-informative priors for novel applications; weakly informative priors based on historical data [38] [39] |

| Equivalence Margin | Define practically important difference | Based on risk assessment, clinical relevance, and regulatory guidance [36] [37] |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo Algorithm | Sample from posterior distributions | Requires convergence diagnostics (e.g., R-hat, effective sample size) [39] |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Assess robustness to prior specifications | Systematically vary prior distributions and report impact on conclusions [39] |

Methodological Workflow

The experimental protocol for conducting Bayesian equivalence testing involves these key steps:

Define Equivalence Boundaries: Establish ROPE boundaries based on risk assessment and practical significance before data collection [36] [8].

Specify Prior Distributions: Justify prior selections based on existing knowledge or use default non-informative priors [39].

Estimate Posterior Distribution: Use MCMC sampling to obtain the joint posterior distribution of all model parameters [38].

Check Convergence: Verify MCMC algorithm convergence using diagnostic measures like R-hat and effective sample size [39].

Calculate HDIs: Compute highest density intervals for target parameters [8].

Apply ROPE Decision Rule: Compare HDIs to predefined ROPE and interpret results [8].

Conduct Sensitivity Analysis: Assess how conclusions change under alternative prior specifications [39].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for a typical equivalence study in pharmaceutical development:

Advantages and Limitations

Benefits of Bayesian Equivalence Testing

The Bayesian ROPE approach offers several distinct advantages for equivalence testing:

- Intuitive Interpretation: Provides direct probabilistic statements about parameters being within practically equivalent ranges [8] [7]

- Flexible Sample Sizes: Applicable to small samples without minimum sample size requirements [7]

- Optional Stopping: Allows interim analyses without statistical penalty, aligning with ethical considerations in clinical research [34]

- Multi-group Extensions: Naturally extends to complex scenarios with multiple groups or sites [38]

- Prior Incorporation: Enables inclusion of relevant historical data or expert knowledge [38]

Challenges and Considerations

Researchers should also be aware of certain limitations:

- Computational Complexity: Requires MCMC sampling and convergence diagnostics [39]

- Subjectivity Concerns: Potential criticism regarding prior specification choices [39]

- Scale Sensitivity: Results depend on parameterization and measurement units [8]

- Reporting Requirements: Need for comprehensive documentation including prior justification and sensitivity analyses [39]

Bayesian equivalence testing using credible intervals and the ROPE provides a powerful framework for demonstrating practical equivalence in pharmaceutical research and drug development. This approach addresses fundamental limitations of traditional significance testing by focusing on practically important effect sizes rather than statistical significance alone.

The direct probabilistic interpretation of Bayesian results offers more intuitive communication of findings to diverse stakeholders, while the flexibility to incorporate prior knowledge and handle complex multi-group scenarios makes it particularly valuable for modern drug development challenges. As the field moves toward more personalized and adaptive research designs, Bayesian equivalence testing is poised to play an increasingly important role in establishing therapeutic equivalence and manufacturing comparability.