Bootstrap Methods for Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to bootstrap methods for model validation, tailored specifically for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

Bootstrap Methods for Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to bootstrap methods for model validation, tailored specifically for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It covers foundational concepts of bootstrap resampling, detailed methodological implementation across various model types including clinical prediction models and nonlinear mixed-effects models, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like overfitting and small-sample bias, and comparative analysis of bootstrap against other validation techniques. The content synthesizes current evidence on advanced correction methods like .632+ estimators and addresses practical challenges in pharmacological and clinical research applications, empowering practitioners to robustly validate predictive models and enhance research reproducibility.

Understanding Bootstrap Validation: Core Concepts and Statistical Foundations

Bootstrapping is a powerful, computer-intensive resampling procedure used for estimating the distribution of an estimator by resampling with replacement from the original data. Introduced by Bradley Efron in 1979, this technique assigns measures of accuracy (such as bias, variance, confidence intervals, and prediction error) to sample estimates, allowing statistical inference without relying on strong parametric assumptions or complicated analytical formulas [1] [2]. The core concept is that inference about a population from sample data (sample → population) can be modeled by resampling the sample data and performing inference about a sample from resampled data (resampled → sample) [1]. The term "bootstrap" aptly derives from the expression "pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps," reflecting how the method generates all necessary statistical testing directly from the available data without external assumptions [2].

The fundamental operation involves creating numerous bootstrap samples, each obtained by random sampling with replacement from the original dataset. Each bootstrap sample is typically the same size as the original sample, and because sampling occurs with replacement, some original observations may appear multiple times while others may not appear at all in a given bootstrap sample [1] [2]. This process is repeated hundreds or thousands of times (typically 1,000-10,000), with the statistic of interest calculated for each bootstrap sample [1] [3]. The resulting collection of bootstrap statistics forms an empirical sampling distribution that provides estimates of standard errors, confidence intervals, and other properties of the statistic [3] [4].

Methodological Approaches

Nonparametric Bootstrap

The nonparametric bootstrap (also called resampling bootstrap) is the most common form of bootstrapping and makes the least assumptions about the underlying population distribution. It treats the original sample as an empirical representation of the population and resamples directly from the observed data values [3].

Protocol: Nonparametric Bootstrap for Confidence Intervals

- Original Sample: Begin with an observed sample of size (n): (X1, X2, ..., X_n) [3]

- Resampling: Generate a bootstrap sample (X^_1, X^2, ..., X^*n) by drawing (n) observations with replacement from the original sample [4]

- Statistic Calculation: Compute the statistic of interest (\hat{\theta}^*) (e.g., mean, median, correlation coefficient) from the bootstrap sample [3]

- Repetition: Repeat steps 2-3 (B) times (typically (B ≥ 1000)) to create a distribution of bootstrap statistics (\hat{\theta}^_1, \hat{\theta}^2, ..., \hat{\theta}^*B) [4]

- Distribution Analysis: Use the distribution of bootstrap statistics to calculate standard errors, confidence intervals, or bias estimates [4]

The percentile method for confidence intervals uses the (\alpha/2) and (1-\alpha/2) quantiles of the bootstrap distribution directly [3]. For a 95% confidence interval, this would be: ((\hat{\theta}^_{0.025}, \hat{\theta}^_{0.975})) [3].

Parametric Bootstrap

Parametric bootstrapping assumes the data comes from a known parametric distribution (e.g., Normal, Poisson, Gamma, Negative Binomial). Instead of resampling from the empirical distribution, parametric bootstrap samples are generated from the estimated parametric distribution [3].

Protocol: Parametric Bootstrap

- Distribution Assumption: Assume a parametric form for the population distribution (F(x|\theta)) [3]

- Parameter Estimation: Estimate parameter(s) (\hat{\theta}) from the original sample ((X1, X2, ..., X_n)) [3]

- Sample Generation: Generate bootstrap samples ((X^_1, X^2, ..., X^*n)) from the distribution (F(x|\hat{\theta})) [3]

- Statistic Calculation: Compute the statistic of interest from each bootstrap sample [3]

- Repetition: Repeat steps 3-4 (B) times [3]

- Analysis: Use the resulting distribution for inference as with nonparametric bootstrap [3]

Parametric bootstrap is particularly useful when the underlying distribution is known or when dealing with small sample sizes where nonparametric bootstrap may perform poorly [3].

Sampling Importance Resampling (SIR)

Sampling Importance Resampling (SIR) is an advanced bootstrap variant that uses importance weighting to improve efficiency, particularly valuable for complex nonlinear models [5]. SIR provides parameter uncertainty in the form of a defined number (m) of parameter vectors representative of the true parameter uncertainty distribution [5].

Protocol: Automated Iterative SIR

- Sampling: Sample (M) parameter vectors (where (M > m)) from a multivariate proposal distribution (e.g., covariance matrix or limited bootstrap) [5]

- Importance Weighting: Compute an importance ratio for each sampled parameter vector representing its probability in the true parameter uncertainty distribution [5]

- Resampling: Resample (m) parameter vectors from the pool of (M) vectors with probabilities proportional to their importance ratio [5]

- Iteration: Use resampled parameters as proposal distribution for next iteration, fitting a multivariate Box-Cox distribution to the resamples at each step [5]

- Convergence Check: Repeat until no changes occur between estimated uncertainty of consecutive iterations [5]

SIR has demonstrated particular utility in nonlinear mixed-effects models (NLMEM) common in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling, where it has been shown to be about 10 times faster than traditional bootstrap while providing appropriate results after approximately 3 iterations on average [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Bootstrap Methodologies

| Method | Key Assumptions | Best Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric Bootstrap | Sample represents population distribution | General purpose; distribution unknown | Minimal assumptions; simple implementation | May perform poorly with very small samples |

| Parametric Bootstrap | Specific distribution form known | Small samples; known distribution | More efficient when assumption correct | Vulnerable to model misspecification |

| Sampling Importance Resampling (SIR) | Proposal distribution approximates true uncertainty | Complex nonlinear models; NLMEM | Computational efficiency; handles complex models | Requires careful diagnostic checking |

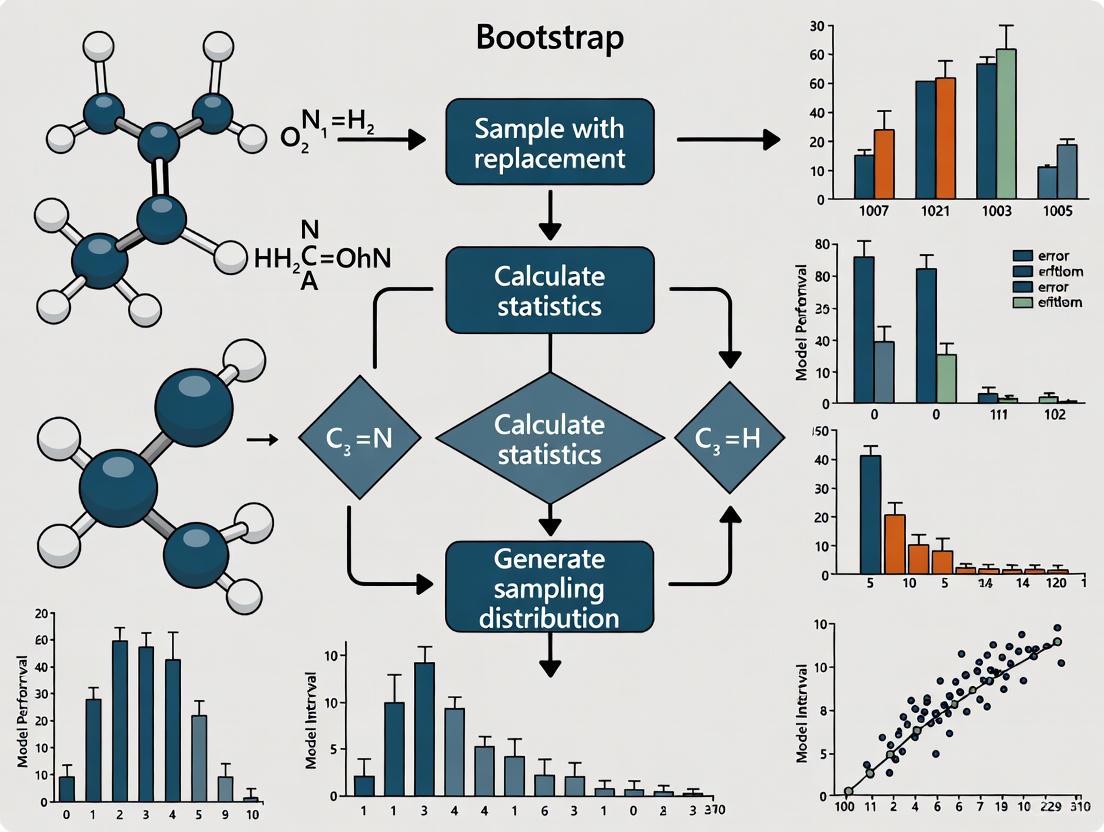

Bootstrap Workflow Diagram

Bootstrap Resampling Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of bootstrap resampling, beginning with the original sample and progressing through repeated resampling with replacement to build an empirical distribution for statistical inference.

Applications in Model Validation and Drug Development

Regression Model Validation

Bootstrap resampling provides robust methods for internal validation of regression models, particularly important in pharmaceutical research where model stability and reliability are critical for decision-making [2]. Traditional training-and-test split methods (e.g., 60% development, 40% validation) can be unstable due to random sampling variations, especially with moderate-sized datasets or rare outcomes [2].

Protocol: Bootstrap Validation of Regression Models

- Model Development: Develop regression model using entire dataset [2]

- Bootstrap Sampling: Draw random sample with replacement of same size as original dataset [2]

- Model Refitting: Perform regression analysis on bootstrap sample [2]

- Performance Assessment: Calculate model performance metrics [2]

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 1000+ times [2]

- Reliability Evaluation: Determine frequency of predictor significance across bootstrap samples (predictors significant in >50% of samples considered reliable) [2]

- Optimism Calculation: Estimate optimism by comparing performance in bootstrap samples versus original sample [2]

This approach allows use of the entire dataset for development while providing realistic estimates of model performance on new data, particularly valuable for mortality prediction models or other rare outcomes in clinical research [2].

Variable Selection in Multivariable Analysis

Bootstrap methods enhance variable selection processes in multivariable regression, addressing challenges of correlated predictors and selection bias [2].

Protocol: Bootstrap-Enhanced Variable Selection

- Univariable Screening: Identify candidate variables with predetermined P-value threshold (typically P<0.05 or P<0.1) [2]

- Correlation Assessment: Evaluate correlation between candidate variables [2]

- Bootstrap Testing: For highly correlated variables (r>0.5), repeat univariable analysis in 1000+ bootstrap samples [2]

- Frequency Evaluation: Count number of samples where each variable shows significance (P<0.05) [2]

- Variable Selection: Select variable with highest frequency of significance for inclusion in multivariable model [2]

This approach was successfully applied to select among correlated pulmonary function variables (FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC ratio, ppoFEV1) for predicting mortality after lung resection, demonstrating practical utility in clinical research [2].

Uncertainty Estimation in Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models

In drug development, nonlinear mixed-effects models (NLMEM) are essential for describing pharmacological processes, and quantifying parameter uncertainty is crucial for informed decision-making [5]. Bootstrap and SIR methods provide assumption-light approaches for uncertainty estimation in these complex models [5].

Protocol: Parameter Uncertainty Estimation with SIR

- Base Model Estimation: Obtain parameter estimates and covariance matrix using standard estimation algorithms [5]

- Proposal Distribution: Set initial proposal distribution to "sandwich" covariance matrix or limited bootstrap [5]

- Iterative SIR: Apply automated iterative SIR procedure with Box-Cox distribution fitting between iterations [5]

- Convergence Monitoring: Continue iterations until uncertainty estimates stabilize (typically 3-4 iterations) [5]

- Diagnostic Checking: Verify adequacy using dOFV plots and temporal trends diagnostics [5]

This approach has been validated across 25 real data examples covering pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic NLMEM with continuous and categorical endpoints, demonstrating robustness for models with up to 39 estimated parameters [5].

Table 2: Bootstrap Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

| Application Area | Protocol | Key Outcome Measures | Typical Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Model Validation | Bootstrap sampling with model refitting | Frequency of predictor significance, optimism correction | 1000 samples, >50% frequency threshold |

| Variable Selection | Univariable testing in bootstrap samples | Count of significant occurrences | 1000 samples, P<0.05 threshold |

| NLMEM Parameter Uncertainty | Sampling Importance Resampling (SIR) | Parameter confidence intervals, standard errors | 3-4 iterations, 1000 resamples |

| Particle Size Distribution Analysis | Nonparametric resampling of particle measurements | Confidence intervals for median size, percentiles | 10000 resamples, percentile CI method |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Bootstrap Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary platform for bootstrap implementation | Comprehensive statistical programming environment |

| boot Package (R) | Specialized bootstrap functions | boot(), boot.ci() for confidence intervals |

| Stata Bootstrap Module | Automated bootstrap sampling | bootstrap command with reps(1000) option |

| PsN Program | Pharmacometric tool with SIR implementation | Automated iterative SIR for NLMEM |

| NONMEM Software | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling | Parameter estimation for SIR procedure |

| Box-Cox Distribution | Flexible parametric distribution in SIR | Accommodates asymmetric uncertainty distributions |

| dOFV Diagnostic Plot | Assessment of SIR adequacy | Comparison to Chi-square distribution |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While bootstrap methods are powerful, they have limitations that researchers must consider. The bootstrap depends heavily on the representative nature of the original sample, and may not perform well with very small samples [1] [4]. For heavy-tailed distributions or populations lacking finite variance, the naive bootstrap may not converge properly [1]. Additionally, bootstrap methods are computationally intensive, though modern computing power has mitigated this concern for most applications [1].

Scholars recommend more bootstrap samples as computing power has increased, with evidence that numbers greater than 100 lead to negligible improvements in standard error estimation [1]. The original developer suggested that even 50 samples can provide fairly good standard error estimates, though 1000+ is common for confidence intervals [1].

When implementing bootstrap methods, careful attention should be paid to diagnostic checking. For SIR procedures, dOFV plots and temporal trends plots help verify adequacy of settings and convergence to the true uncertainty distribution [5]. For nonparametric bootstrap, examining the shape of the bootstrap distribution provides insights about potential biases or skewness [4].

Bootstrap methodology, particularly resampling with replacement, provides a flexible, assumption-light framework for statistical inference that has proven invaluable in model validation research and drug development. Through its various implementations—nonparametric, parametric, and advanced variants like SIR—bootstrap methods enable researchers to quantify uncertainty, validate models, select variables, and make informed decisions with greater confidence. The continued development of automated procedures and diagnostic tools has further enhanced the accessibility and reliability of bootstrap methods across diverse research applications in pharmaceutical science and beyond.

Bootstrap model validation operates on a powerful core philosophy: treating a single observed dataset as an empirical population from which we can resample to estimate how a predictive model would perform on future, unseen data [6]. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in statistical modeling—the optimistic bias that occurs when a model's performance is evaluated on the same data used for its training [7]. By creating multiple bootstrap samples (simulated datasets) through resampling with replacement, researchers can quantify this optimism and correct for it, producing performance estimates that more accurately reflect real-world application [8] [9].

In pharmaceutical development and biomedical research, this methodology has proven particularly valuable for validating risk prediction models, treatment effect estimation, and precision medicine strategies where data may be limited or expensive to obtain [8] [7]. The bootstrap validation framework allows researchers to make statistically rigorous inferences about model performance while fully utilizing all available data, unlike data-splitting approaches that reduce sample size for model development [6].

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

The Empirical Population Concept

The foundational principle of bootstrap validation is that the observed sample of data represents an empirical approximation of the true underlying population. Through resampling with replacement, we generate bootstrap samples that mimic the process of drawing new samples from this empirical population [9]. Each bootstrap sample serves as a training set for model development, while the original dataset functions as a test set for performance evaluation [6].

This approach enables researchers to measure what is known as "optimism"—the difference between a model's performance on the data it was trained on versus its performance on new data [8]. The average optimism across multiple bootstrap samples provides a bias correction that yields more realistic estimates of how the model will generalize [6].

Comparison of Resampling Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Model Validation Techniques

| Validation Method | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap Validation | Resampling with replacement from original dataset [9] | Uses full dataset for model development; Provides optimism correction [6] | Computational intensity; Can have slight pessimistic bias [9] |

| Data Splitting | Random division into training/test sets | Simple implementation; Clear separation of training and testing | Reduces sample size for model development; High variance based on split [6] |

| Cross-Validation | Resampling without replacement; k-fold partitioning [9] | More efficient use of data than simple splitting | May require more iterations; Can overestimate variance [7] |

| .632 Bootstrap | Weighted combination of bootstrap and apparent error | Reduced bias compared to standard bootstrap | Increased complexity; May still be optimistic with high overfitting [9] |

Application Notes: Implementation Protocols

Core Bootstrap Validation Protocol

The following detailed protocol implements bootstrap model validation for a logistic regression model predicting binary clinical outcomes, adaptable to other model types and research contexts.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bootstrap Validation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R) | Computational environment for resampling and model fitting [6] [10] | R statistical programming language |

| Resampling Algorithm | Mechanism for drawing bootstrap samples from empirical population [9] | boot package in R or custom implementation |

| Performance Metrics | Quantification of model discrimination and calibration [8] | Somers' D, c-statistic (AUC), calibration plots |

| Model Training Function | Procedure for fitting model to each bootstrap sample [6] | glm(), lrm(), or other model fitting functions |

| Validation Function | Calculation of optimism-corrected performance [6] | Custom function to compare training vs. test performance |

Procedure:

Define Performance Metric: Select an appropriate performance measure for your research question. For binary outcomes, Somers' D (rank correlation between predicted probabilities and observed responses) or the c-statistic (AUC) are common choices [6]. Calculate this metric on the full original dataset to obtain the apparent performance:

D_orig <- somers2(x = predict(m, type = "response"), y = d$low)Generate Bootstrap Samples: Create multiple (typically 200-500) bootstrap samples by resampling the original dataset with replacement while maintaining the same sample size [8] [6]. Random seed setting ensures reproducibility:

set.seed(222)i <- sample(nrow(d), size = nrow(d), replace = TRUE)Fit Bootstrap Models: Develop the model using each bootstrap sample, maintaining the same model structure and variable selection as the original model [6]:

m2 <- glm(low ~ ht + ptl + lwt, family = binomial, data = d[i,])Calculate Performance Differences: For each bootstrap model, compute two performance values: a. Performance on the bootstrap sample (training performance) b. Performance on the original dataset (test performance) The difference between these values represents the optimism for that iteration [6].

Compute Optimism-Corrected Performance: Average the optimism values across all bootstrap samples and subtract this from the original apparent performance to obtain the bias-corrected estimate [6]:

corrected_performance <- D_orig["Dxy"] - mean(sd.out$t)

Diagram 1: Bootstrap validation workflow with optimism correction. This process generates optimism-corrected performance estimates through iterative resampling.

Advanced Protocol: External Validation Framework

For regulatory applications or when assessing generalizability across populations, external validation using the bootstrap framework provides stronger evidence of model performance [8].

Procedure:

Cohort Specification: Define distinct development and validation cohorts, ensuring the validation cohort represents the target population for model application.

Bootstrap Internal Validation: Perform the core bootstrap validation protocol (Section 3.1) on the development cohort to generate optimism-corrected performance metrics.

External Validation Application: Apply the final model developed on the full development cohort to the independent validation cohort without any model refitting.

Performance Comparison: Compare model performance between the optimism-corrected estimates from the development cohort and the observed performance on the validation cohort. Substantial differences may indicate cohort differences or model overfitting [8].

Shrinkage Estimation: Calculate the heuristic shrinkage factor based on the model's log-likelihood ratio χ² statistic. Apply shrinkage to model coefficients if the factor is below 0.9 to reduce overfitting [8].

Results and Interpretation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Bootstrap-Validated Performance Metrics for Predictive Models

| Performance Measure | Calculation Method | Interpretation Guidelines | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism-Corrected R² | Original R² minus average optimism in R² across bootstrap samples [8] | Higher values indicate better explanatory power; Values close to apparent R² suggest minimal overfitting | Continuous outcome models |

| Optimism-Corrected C-Statistic | Original C-statistic minus average optimism in discrimination [8] | 0.5 = random discrimination; 0.7-0.8 = acceptable; 0.8-0.9 = excellent; >0.9 = outstanding [6] | Binary outcome models; Risk prediction |

| Somers' Dxy | Rank correlation between predicted probabilities and observed responses [6] | Ranges from -1 to 1; Values closer to 1 indicate better discrimination | Binary outcome models |

| Calibration Slope | Slope of predicted vs. observed outcomes [8] | Ideal value = 1; Values <1 indicate overfitting; Values >1 indicate underfitting | All prediction models |

Case Study: Clinical Prediction Model

In a practical implementation using the birthwt dataset predicting low infant birth weight, bootstrap validation demonstrated the method's value for correcting optimistic performance estimates:

Apparent Performance: The initial model showed Somers' D = 0.438 and c-statistic = 0.719 when evaluated on its own development data [6].

Bootstrap Correction: After 200 bootstrap iterations, the optimism-corrected Somers' D was 0.425, indicating that the original estimate was overly optimistic by approximately 3% [6].

Clinical Interpretation: The corrected performance metrics provide a more realistic assessment of how the model would perform when deployed in clinical practice, informing decisions about its implementation for risk stratification.

Diagram 2: Performance estimation and correction workflow. The bootstrap process quantifies optimism to produce realistic performance estimates for new data.

Discussion

Advantages and Limitations

The empirical population approach underlying bootstrap validation offers significant advantages over alternative validation methods. By using the entire dataset for both model development and validation, it maximizes statistical power—particularly valuable when sample sizes are limited, as often occurs in biomedical research and drug development [6]. The method provides not only a point estimate of corrected performance but also enables quantification of uncertainty through confidence intervals [7].

However, researchers must acknowledge several limitations. The computational demands of bootstrap validation can be substantial, particularly with complex models or large numbers of iterations [7] [9]. The approach assumes the original sample adequately represents the underlying population, which may not hold with small samples or rare outcomes. Some studies have noted that bootstrap validation can exhibit slight pessimistic bias compared to other resampling methods [9].

Regulatory and Application Context

In pharmaceutical statistics and medical device development, bootstrap validation has gained acceptance for supporting regulatory submissions by providing robust evidence of model performance and generalizability [8] [10]. The method aligns with the principles outlined in the SIMCor project for validating virtual cohorts and in-silico trials in cardiovascular medicine [10].

For precision medicine applications, including individualized treatment recommendation systems, bootstrap methods enable validation of complex strategies that identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific therapies [7]. This capability is particularly valuable for demonstrating treatment effect heterogeneity in clinical development programs.

Bootstrap model validation, grounded in the philosophy of using observed data as an empirical population, provides a robust framework for estimating how predictive models will perform on future data. Through systematic resampling and optimism correction, researchers in drug development and biomedical science can produce more realistic performance estimates while fully utilizing available data. The protocols outlined in this article provide implementable methodologies for applying these techniques across various research contexts, from clinical prediction models to treatment effect estimation. As the field advances, integrating bootstrap validation with emerging statistical approaches will continue to enhance the rigor and reliability of predictive modeling in healthcare.

Bootstrap methods, formally introduced by Bradley Efron in 1979, represent a fundamental advancement in statistical inference by providing a computationally-based approach to assessing the accuracy of sample statistics [1] [11]. The core principle of bootstrapping involves resampling the original dataset with replacement to create numerous simulated samples, thereby empirically approxim the sampling distribution of a statistic without relying on stringent parametric assumptions [12]. This approach has revolutionized statistical practice by enabling inference in situations where theoretical sampling distributions are unknown, mathematically intractable, or rely on assumptions that may not hold in practice.

In the context of model validation research, particularly in scientific fields such as drug development, bootstrap methods offer a powerful toolkit for quantifying uncertainty and assessing model robustness [13] [14]. Traditional parametric methods often depend on assumptions of normality and large sample sizes, which frequently prove untenable with complex real-world data [12]. Bootstrap methodology circumvents these limitations by treating the observed sample as a empirical representation of the population, using resampling techniques to estimate standard errors, construct confidence intervals, and evaluate potential bias in statistical estimates [1] [15]. This practical framework has become indispensable for researchers requiring reliable inference from limited data or complex models where conventional approaches fail.

The conceptual foundation of bootstrapping rests on the principle that repeated resampling from the observed data mimics the process of drawing multiple samples from the underlying population [15]. By generating thousands of resampled datasets and computing the statistic of interest for each, researchers can construct an empirical sampling distribution that reflects the variability inherent in the estimation process [11]. This distribution serves as the basis for calculating standard errors directly from the standard deviation of the bootstrap estimates and for constructing confidence intervals through various techniques including the percentile method or more advanced bias-corrected approaches [16] [14].

Fundamental Bootstrap Algorithms and Workflows

Core Resampling Mechanism

The non-parametric bootstrap algorithm operates through a systematic resampling process designed to empirically approximate the sampling distribution of a statistic. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for implementing the basic bootstrap method:

Original Sample Collection: Begin with an observed data set containing ( n ) independent and identically distributed observations: ( X = {x1, x2, \ldots, x_n} ). This sample serves as the empirical approximation to the underlying population [12] [15].

Bootstrap Sample Generation: Generate a bootstrap sample ( X^{b} = {x^{b}1, x^{*b}2, \ldots, x^{*b}_n} ) by randomly selecting ( n ) observations from ( X ) with replacement, where ( b ) indexes the bootstrap replication (( b = 1, 2, \ldots, B )). The "with replacement" aspect ensures each observation has probability ( 1/n ) of being selected in each draw, making bootstrap samples replicate the original sample size while potentially containing duplicates and omitting some original observations [1] [11].

Statistic Computation: Calculate the statistic of interest ( \hat{\theta}^{b} ) for each bootstrap sample ( X^{b} ). This statistic may represent a mean, median, regression coefficient, correlation, or any other estimand relevant to the research question [12] [15].

Repetition: Repeat steps 2-3 a large number of times (( B )), typically ( B ≥ 1000 ) for standard error estimation and ( B ≥ 2000 ) for confidence intervals, to build a collection of bootstrap estimates ( {\hat{\theta}^{1}, \hat{\theta}^{2}, \ldots, \hat{\theta}^{*B}} ) [1] [14].

Empirical Distribution Formation: Use the collection of bootstrap estimates to construct the empirical bootstrap distribution, which serves as an approximation to the true sampling distribution of ( \hat{\theta} ) [12] [15].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this resampling process:

Estimation of Standard Errors

The bootstrap estimate of the standard error for a statistic ( \hat{\theta} ) is calculated directly as the standard deviation of the empirical bootstrap distribution [1] [15]. This approach provides a computationally straightforward yet powerful method for assessing the variability of an estimator without deriving complex mathematical formulas.

The standard error estimation protocol proceeds as follows:

Bootstrap Distribution Construction: Implement the core resampling mechanism described in Section 2.1 to generate ( B ) bootstrap estimates of the statistic: ( {\hat{\theta}^{1}, \hat{\theta}^{2}, \ldots, \hat{\theta}^{*B}} ).

Standard Deviation Calculation: Compute the bootstrap standard error (( \widehat{SE}{boot} )) using the formula: [ \widehat{SE}{boot} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{B-1} \sum{b=1}^B \left( \hat{\theta}^{*b} - \bar{\hat{\theta}}^* \right)^2} ] where ( \bar{\hat{\theta}}^* = \frac{1}{B} \sum{b=1}^B \hat{\theta}^{*b} ) represents the mean of the bootstrap estimates [15].

Interpretation: The resulting ( \widehat{SE}_{boot} ) quantifies the variability of the estimator ( \hat{\theta} ) under repeated sampling from the empirical distribution, providing a reliable measure of precision that remains valid even when theoretical standard errors are unavailable or rely on questionable assumptions [1] [12].

This method applies universally to virtually any statistic, enabling standard error estimation for complex estimators such as mediation effects in path analysis, adjusted R² values, or percentile ratios where theoretical sampling distributions present significant analytical challenges [12] [14].

Advanced Bootstrap Confidence Interval Methods

Comparative Analysis of Confidence Interval Techniques

While the standard error provides a measure of precision, confidence intervals offer a range of plausible values for the population parameter. Bootstrap methods generate confidence intervals through several distinct approaches, each with specific properties and applicability conditions. The following table summarizes the primary bootstrap confidence interval methods:

Table 1: Bootstrap Confidence Interval Methods Comparison

| Method | Algorithm | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | Use α/2 and 1-α/2 percentiles of bootstrap distribution [16] [15] | Simple, intuitive, range-preserving [16] | Assumes bootstrap distribution is unbiased; first-order accurate [14] | General use with well-behaved statistics; initial analysis |

| Basic Bootstrap | CI = [2θ̂ - θ̂(1-α/2), 2θ̂ - θ̂(α/2)] where θ̂*(α) is α quantile of bootstrap distribution [16] | Simple transformation of percentile method [16] | Can produce impossible ranges; same accuracy as percentile [16] | Symmetric statistics; educational demonstrations |

| Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) | Adjusts percentiles using bias (z₀) and acceleration (a) correction factors [1] [14] | Second-order accurate; accounts for bias and skewness [14] | Computationally intensive; requires jackknife for acceleration [14] | Gold standard for complex models; publication-quality results |

| Studentized | Uses bootstrap t-distribution with estimated standard errors for each resample [16] | Higher-order accuracy; theoretically superior [16] | Computationally expensive; requires variance estimation for each resample [16] | Complex models with heterogeneous errors; small samples |

The relationship between these methods and their accuracy characteristics can be visualized as follows:

BCa Confidence Interval Protocol

The Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa) bootstrap confidence interval provides second-order accurate coverage that accounts for both bias and skewness in the sampling distribution [14]. The following protocol details its implementation:

Preliminary Bootstrap Analysis: Generate ( B ) bootstrap replicates (( B ≥ 2000 )) of the statistic ( \hat{\theta} ) using the standard resampling procedure described in Section 2.1.

Bias Correction Estimation:

- Calculate the proportion of bootstrap estimates less than the original estimate: ( p_0 = \frac{#{\hat{\theta}^{*b} < \hat{\theta}}}{B} )

- Compute the bias correction parameter: ( z0 = \Phi^{-1}(p0) ) where ( \Phi^{-1} ) is the inverse standard normal cumulative distribution function [14].

Acceleration Factor Estimation:

- Perform jackknife resampling: systematically omit each observation ( i ) and compute the statistic ( \hat{\theta}_{(-i)} ) on the remaining ( n-1 ) observations.

- Calculate the jackknife mean: ( \bar{\hat{\theta}}{(\cdot)} = \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^n \hat{\theta}_{(-i)} )

- Compute the acceleration parameter: [ a = \frac{\sum{i=1}^n (\bar{\hat{\theta}}{(\cdot)} - \hat{\theta}{(-i)})^3}{6[\sum{i=1}^n (\bar{\hat{\theta}}{(\cdot)} - \hat{\theta}{(-i)})^2]^{3/2}} ] [14]

Adjusted Percentiles Calculation:

- For a ( 100(1-\alpha)\% ) confidence interval, compute adjusted probabilities: [ \alpha1 = \Phi\left(z0 + \frac{z0 + z{\alpha/2}}{1 - a(z0 + z{\alpha/2})}\right) ] [ \alpha2 = \Phi\left(z0 + \frac{z0 + z{1-\alpha/2}}{1 - a(z0 + z{1-\alpha/2})}\right) ] where ( z_\alpha = \Phi^{-1}(\alpha) ) [14].

Confidence Interval Construction: Extract the ( \alpha1 ) and ( \alpha2 ) quantiles from the sorted bootstrap distribution to obtain the BCa confidence interval: ( [\hat{\theta}^{(\alpha_1)}, \hat{\theta}^{(\alpha_2)}] ) [14].

The BCa method automatically produces more accurate coverage than standard percentile intervals, particularly for skewed sampling distributions or biased estimators, making it particularly valuable for model validation research where accurate uncertainty quantification is essential [14].

Application in Model Validation Research

Bootstrap Protocol for Model Validation

In model validation research, particularly in drug development and clinical studies, bootstrap methods provide robust internal validation of predictive models by correcting for overoptimism and estimating expected performance on new data [13]. The following protocol implements the Efron-Gong optimism bootstrap for overfitting correction:

Model Fitting and Apparent Performance:

- Fit the model to the original dataset ( D = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2), \ldots, (xn, yn)} ).

- Calculate the apparent performance measure ( \theta_{app} ) (e.g., R², AUC, Brier score, calibration slope) using the same data for both fitting and evaluation [13].

Bootstrap Resampling and Optimism Estimation: For ( b = 1 ) to ( B ) (typically ( B ≥ 200 )):

- Draw a bootstrap sample ( D^{*b} ) from ( D ) with replacement.

- Fit the model to ( D^{b} ) and compute the performance measure ( \theta_b^{} ) on the bootstrap sample.

- Apply the bootstrap-fitted model to the original data ( D ) and compute the performance measure ( \theta_b ).

- Calculate the optimism estimate for this resample: ( \Deltab = \thetab^{*} - \theta_b ) [13].

Average Optimism Calculation: Compute the average optimism: ( \bar{\Delta} = \frac{1}{B} \sum{b=1}^B \Deltab ).

Overfitting-Corrected Performance: Calculate the optimism-corrected performance estimate: ( \theta{corrected} = \theta{app} - \bar{\Delta} ) [13].

Confidence Interval Estimation: Implement the BCa confidence interval protocol from Section 3.2 on the optimism-corrected estimates to quantify the uncertainty in the validated performance measure.

This approach directly estimates and corrects for the overfitting bias inherent in model development, providing a more realistic assessment of how the model will perform on future observations [13]. The method applies to various performance metrics including discrimination, calibration, and overall accuracy measures.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Bootstrap Inference

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Programming Environments | R, Python, Stata, SAS | Provides foundation for custom bootstrap implementation [16] | R offers comprehensive bootstrap packages; Python provides scikit-learn and scikit-bootstrap |

| Specialized R Packages | boot, bcaboot, rsample, infer |

Implement various bootstrap procedures with optimized algorithms [16] [14] | bcaboot provides automatic second-order accurate intervals; boot offers comprehensive method collection |

| Bootstrap Computation Management | Parallel processing, Cloud computing | Accelerates computation for large B or complex models [14] | Essential for B > 1000 with computationally intensive models; reduces practical implementation barriers |

| Visualization and Reporting | ggplot2, matplotlib, custom plotting | Documents bootstrap distributions and interval estimates [16] | Critical for diagnostic assessment of bootstrap distribution shape and identification of issues |

Bootstrap methods for confidence intervals and standard errors provide an essential framework for robust statistical inference in model validation research. Through resampling-based estimation of sampling distributions, these techniques enable reliable uncertainty quantification without relying on potentially untenable parametric assumptions. The BCa confidence interval method offers particular value for scientific applications requiring accurate coverage probabilities, while the optimism bootstrap addresses the critical need for overfitting correction in predictive model development.

For drug development professionals and researchers, implementing these bootstrap protocols ensures statistically rigorous model validation and inference, even with complex models, limited sample sizes, or non-standard estimators. The computational tools and methodologies outlined in these application notes provide a practical foundation for implementing bootstrap approaches that enhance the reliability and reproducibility of scientific research.

Why Bootstrap for Model Validation? Advantages Over Parametric Assumptions

Bootstrapping, formally introduced by Bradley Efron in 1979, represents a fundamental shift in statistical inference, moving from traditional algebraic approaches to modern computational methods [1] [12]. As a resampling technique, it empirically approximates the sampling distribution of a statistic by repeatedly drawing samples with replacement from the original observed data [1] [17]. This approach allows researchers to assess the variability and reliability of estimates without relying heavily on strict parametric assumptions about the underlying population distribution [12]. In the context of model validation, bootstrapping provides a robust framework for evaluating model performance, estimating parameters, and constructing confidence intervals, making it particularly valuable in drug development where data may be limited, complex, or non-normally distributed [18] [19].

The core principle of bootstrapping lies in treating the observed sample as a proxy for the population [12]. By generating numerous bootstrap samples (typically 1,000 or more) of the same size as the original dataset through sampling with replacement, researchers can create an empirical distribution of the statistic of interest [1] [17]. This distribution then serves as the basis for inference, enabling the estimation of standard errors, confidence intervals, and bias without requiring complex mathematical derivations or assuming a specific parametric form for the population [12] [19]. This methodological flexibility has positioned bootstrapping as a gold standard in many analytical scenarios, including mediation analysis in clinical trials and validation of predictive models in pharmaceutical research [12].

Theoretical Foundations: Bootstrap vs. Parametric Inference

The Parametric Paradigm and Its Limitations

Traditional parametric methods rely on specific assumptions about the underlying distribution of the population being studied, most commonly the normal distribution [20]. These methods estimate parameters (such as mean and variance) of this assumed distribution and derive inferences based on known theoretical sampling distributions like the z-distribution or t-distribution [12]. Common parametric tests include t-tests, ANOVA, and linear regression, which provide powerful inference when their assumptions are met [21] [20]. The primary advantage of parametric methods is their statistical power – when distributional assumptions hold, they are more likely to detect true effects with smaller sample sizes compared to non-parametric alternatives [21] [20].

However, parametric inference faces significant limitations in real-world research applications. When assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, or independence are violated, parametric tests can produce biased and misleading results [12] [20]. In pharmaceutical research, data often exhibit skewness, outliers, or complex correlation structures that violate these assumptions [21]. Furthermore, for complex statistics like indirect effects in mediation analysis or ratios of variance, the theoretical sampling distribution may be unknown or mathematically intractable, making parametric inference impossible or requiring complicated formulas for standard error calculation [1] [12].

The Bootstrap Alternative

Bootstrapping addresses these limitations by replacing theoretical derivations with computational empiricism [12]. Rather than assuming a specific population distribution, the bootstrap uses the empirical distribution of the observed data as an approximation of the population distribution [1]. The fundamental concept is that the relationship between the original sample and the population is analogous to the relationship between bootstrap resamples and the original sample [1]. This approach allows researchers to estimate the sampling distribution of virtually any statistic, regardless of its complexity [1] [12].

The theoretical justification for bootstrapping stems from the principle that the original sample distribution function approximates the population distribution function [1]. As sample size increases, this approximation improves, leading to consistent bootstrap estimates [18]. Importantly, bootstrap methods can be applied to a wide range of statistical operations including estimating standard errors, constructing confidence intervals, calculating bias, and performing hypothesis tests – all without the strict distributional requirements of parametric methods [1] [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Statistical Inference Approaches

| Feature | Parametric Methods | Bootstrap Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Theoretical sampling distributions | Empirical resampling [12] |

| Key Assumption | Data follows known distribution (e.g., normal) [20] | Sample represents population [1] |

| Implementation | Mathematical formulas | Computational algorithm [12] |

| Information Source | Population parameters | Observed sample [1] |

| Output | Parameter estimates with theoretical standard errors | Empirical sampling distribution [12] |

| Complexity Handling | Limited to known distributions | Applicable to virtually any statistic [1] |

Advantages of Bootstrap for Model Validation

Assumption Flexibility and Robustness

A primary advantage of bootstrapping in model validation is its minimal distributional assumptions [17] [19]. Unlike parametric methods that require data to follow specific distributions, bootstrap methods are "distribution-free," making them particularly valuable when analyzing real-world data that often deviates from theoretical ideals [12] [20]. This flexibility is crucial in pharmaceutical research where biological data frequently exhibit skewness, heavy tails, or outliers that violate parametric assumptions [21]. Bootstrap validation provides reliable inference even when data distribution is unknown or complex, ensuring robust model assessment across diverse experimental conditions [1] [19].

Applicability to Complex Estimators

Bootstrapping excels in situations requiring validation of complex models and estimators that lack known sampling distributions or straightforward standard error formulas [1] [12]. In drug development, this includes pharmacokinetic parameters, dose-response curves, mediator effects in clinical outcomes, and machine learning prediction models [12] [19]. The bootstrap approach consistently estimates sampling distributions for these complex statistics through resampling, whereas parametric methods would require extensive mathematical derivations or approximations that may not be statistically valid [1]. This capability makes bootstrap validation indispensable for modern analytical challenges in pharmaceutical research.

Performance with Limited Data

Bootstrap methods provide particular value in validation scenarios with limited sample sizes, a common challenge in early-stage drug development and rare disease research [12] [17]. While parametric tests require sufficient sample sizes to satisfy distributional assumptions (e.g., n > 15-20 per group for t-tests with nonnormal data), bootstrapping can generate reasonable inference even from modest samples by leveraging the available data more comprehensively [21]. However, scholars note that very small samples may still challenge bootstrap methods, as the original sample must adequately represent the population [18] [17].

Comprehensive Uncertainty Quantification

Bootstrap validation facilitates comprehensive uncertainty assessment through multiple approaches for confidence interval construction [12]. Beyond standard percentile methods, advanced techniques like bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) intervals can address skewness and non-sampling error in complex models [1]. This flexibility enables researchers to tailor uncertainty quantification to specific validation needs, providing more accurate coverage probabilities than parametric intervals when data violate standard assumptions [12]. Additionally, bootstrapping naturally accommodates the estimation of prediction error, model stability, and other validation metrics through resampling [19].

Table 2: Bootstrap Advantages for Specific Model Validation Scenarios

| Validation Scenario | Parametric Challenge | Bootstrap Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effects (Mediation) | Product of coefficients not normally distributed [12] | Empirical sampling distribution without normality assumption [12] |

| Small Pilot Studies | Insufficient power and unreliable normality tests [21] | Resampling-based inference without distributional requirements [12] |

| Machine Learning Models | Complex parameters without known distributions [19] | Empirical confidence intervals for any performance metric [19] |

| Skewed Clinical Outcomes | Biased mean estimates with influential outliers [21] | Robust median estimation or outlier-resistant resampling [21] |

| Time-to-Event Data | Complex censoring mechanisms | Custom resampling approaches preserving censoring structure |

Bootstrap Protocols for Model Validation

Non-Parametric Bootstrap Algorithm for Model Validation

The non-parametric bootstrap serves as the foundational approach for most model validation applications, creating resamples directly from the empirical distribution of the observed data [12]. This protocol is particularly suitable for validating predictive models, estimating confidence intervals for performance metrics, and assessing model stability.

Workflow Title: Non-Parametric Bootstrap Model Validation Protocol

Experimental Protocol:

- Original Sample Preparation: Begin with an original dataset containing n independent observations. For model validation, ensure the dataset includes both predictor variables and response variables. [1] [17]

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: Randomly select n observations from the original dataset with replacement. This constitutes one bootstrap sample. Some original observations will appear multiple times, while others may not appear at all. [1] [12]

- Model Fitting and Validation: Fit the model of interest to the bootstrap sample and calculate the validation metric(s) of interest (e.g., R², AUC, prediction error, coefficient estimates). [19]

- Result Storage: Store the calculated validation metric(s) from the current bootstrap sample. [17]

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 a large number of times (B). Scholars recommend B ≥ 1,000 for standard errors and B ≥ 10,000 for confidence intervals, though even B = 50 can provide reasonable estimates in many cases. [1]

- Distribution Analysis: Analyze the distribution of the B bootstrap estimates to calculate validation statistics:

Parametric Bootstrap for Distributional Models

The parametric bootstrap approach applies when a specific distributional form is assumed for the data generating process. This protocol is valuable for validating models based on theoretical distributions or when comparing parametric assumptions.

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Estimation: Fit the parametric model to the original dataset of size n, obtaining parameter estimates (e.g., μ̂, σ̂ for normal distribution). [1]

- Parametric Resampling: Generate B bootstrap samples by simulating n observations from the estimated parametric distribution with the fitted parameters.

- Model Refitting: For each bootstrap sample, refit the parametric model and extract the parameters of interest.

- Inference: Construct confidence intervals and standard errors from the distribution of bootstrap parameter estimates, similar to the non-parametric approach.

Bootstrap Hypothesis Testing for Model Comparison

Bootstrap methods provide robust approaches for hypothesis testing in model validation, particularly when comparing nested models or testing significant terms in complex models.

Experimental Protocol:

- Null Model Specification: Define the null hypothesis (H₀) corresponding to the reduced model.

- Resampling Under H₀: Generate bootstrap samples from the population model satisfying H₀. This may involve:

- Centering residuals for regression models

- Modifying parameter estimates to satisfy constraints

- Using the reduced model as the data generating process

- Test Statistic Calculation: For each bootstrap sample, calculate the test statistic comparing the full and reduced models (e.g., F-statistic, likelihood ratio, difference in AUC).

- P-value Estimation: Compute the proportion of bootstrap test statistics exceeding the observed test statistic from the original sample.

- Power Assessment: Estimate statistical power by calculating the proportion of bootstrap samples that correctly reject H₀ when applied to alternative hypothesis scenarios.

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Research

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Bootstrap Model Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Bootstrap Validation | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Comprehensive bootstrap implementation with multiple packages [22] | boot, bootstrap, gofreg packages [22] |

| Python Scientific Stack | Flexible bootstrap implementation for machine learning models | scikit-learn, numpy, scipy libraries [17] |

| Specialized Bootstrap Packages | Domain-specific bootstrap implementations | gofreg for goodness-of-fit testing [22] |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel processing for computationally intensive resampling | Cloud computing, cluster processing for B > 10,000 |

Case Study: Validating a Dose-Response Model

The following case study illustrates a complete bootstrap validation workflow for a pharmaceutical dose-response model, demonstrating the practical application of bootstrap protocols in drug development.

Workflow Title: Dose-Response Model Bootstrap Validation

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Collect experimental data measuring biological response across multiple dose levels, typically with replication at each dose.

- Model Specification: Select appropriate dose-response model (e.g., Emax model, sigmoidal model) based on biological mechanism.

- Bootstrap Implementation:

- Generate 10,000 bootstrap samples by resampling complete experimental units with replacement

- For each bootstrap sample, fit the dose-response model and extract key parameters (EC₅₀, Emax, Hill coefficient)

- Record goodness-of-fit statistics (R², RMSE) for each bootstrap fit

- Validation Metrics:

- Calculate 95% confidence intervals for each parameter using percentile method

- Assess parameter correlation through bootstrap scatterplot matrices

- Evaluate model stability by examining bootstrap distributions for multimodality or skewness

- Estimate precision of potency estimates (EC₅₀) through coefficient of variation

- Decision Framework:

- If bootstrap CIs for key parameters exclude clinically irrelevant values, model is validated

- If bootstrap distributions show instability, consider model simplification or additional data collection

Bootstrap Validation of Clinical Prediction Models

For clinical prediction models used in patient stratification or biomarker validation, bootstrapping provides robust assessment of model performance and generalizability.

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Development: Develop the clinical prediction model using the complete dataset.

- Bootstrap Validation:

- Generate 1,000 bootstrap samples

- For each bootstrap sample, refit the model and calculate performance metrics on both the bootstrap sample (apparent performance) and the original sample (test performance)

- Calculate the optimism for each performance metric (apparent minus test performance)

- Optimism Correction:

- Calculate average optimism across all bootstrap samples

- Subtract average optimism from apparent performance to obtain optimism-corrected performance estimates

- Performance Reporting:

- Report optimism-corrected performance metrics with bootstrap confidence intervals

- Compare performance across clinically relevant subgroups using bootstrap percentile methods

Limitations and Considerations

Despite its considerable advantages, bootstrap validation requires careful implementation and interpretation. Key limitations include:

Computational Intensity: Bootstrap methods can be computationally demanding, particularly with large datasets or complex models requiring extensive resampling [17] [19]. While modern computing resources have mitigated this concern for most applications, very intensive simulations may still require high-performance computing resources [12].

Small Sample Challenges: With very small samples (n < 10-20), bootstrap methods may perform poorly because the original sample may not adequately represent the population distribution [18] [17]. In such cases, the m-out-of-n bootstrap (resampling m < n observations) or parametric methods with strong assumptions may be preferable [18].

Dependence Structure Complications: Standard bootstrap methods assume independent observations and may perform poorly with correlated data, such as repeated measures, time series, or clustered designs [12]. Modified bootstrap procedures (block bootstrap, cluster bootstrap, residual bootstrap) must be employed for such data structures [12].

Extreme Value Estimation: Bootstrap methods struggle with estimating statistics that depend heavily on distribution tails (e.g., extreme quantiles, maximum values) because resampled datasets cannot contain values beyond the observed range [12]. For such applications, specialized extreme value methods or semi-parametric approaches may be necessary.

Representativeness Requirement: The fundamental requirement for valid bootstrap inference is that the original sample represents the population well [1] [12]. Biased samples will produce biased bootstrap distributions, potentially leading to incorrect inferences in model validation [18].

Bootstrap methods represent a paradigm shift in model validation, offering pharmaceutical researchers powerful tools for assessing model performance without restrictive parametric assumptions. The computational elegance of bootstrapping – replacing complex mathematical derivations with empirical resampling – has made robust statistical inference accessible for complex models common in drug development. As computational resources continue to expand and specialized bootstrap variants emerge for specific research applications, bootstrap validation will remain an essential component of rigorous pharmaceutical research methodology. By implementing the protocols and considerations outlined in this application note, researchers can enhance the reliability and interpretability of their models throughout the drug development pipeline.

The bootstrap is a computational procedure for estimating the sampling distribution of a statistic, thereby assigning measures of accuracy—such as bias, variance, and confidence intervals—to sample estimates. This powerful resampling technique allows researchers to perform statistical inference without relying on strong parametric assumptions, which often cannot be justified in practice. First formally proposed by Bradley Efron in 1979, the bootstrap has emerged as one of the most influential methods in modern statistical analysis, particularly valuable for complex estimators where traditional analytical formulas are unavailable or require complicated standard error calculations [12] [1].

At its core, the bootstrap uses the observed data as a stand-in for the population. By repeatedly resampling from the original dataset with replacement, it creates multiple simulated samples, enabling empirical approximation of the sampling distribution for virtually any statistic of interest. This approach transforms statistical inference from an algebraic problem dependent on normality assumptions to a computational one that relies on resampling principles. The method's flexibility has led to its adoption across numerous domains, including medical statistics, epidemiological research, and drug development, where it provides robust validation for predictive models and uncertainty quantification for parameter estimates [12] [6].

Theoretical Foundation

The Core Concept of Resampling

The fundamental principle underlying bootstrap methodology involves using the empirical distribution function of the observed data as an approximation of the true population distribution. The non-parametric bootstrap, the most common variant, operates on a simple premise: if the original sample is representative of the population, then resampling from this sample with replacement will produce bootstrap samples that mimic what we might obtain if we were to draw new samples from the population itself [12] [1].

The bootstrap procedure conceptually models inference about a population from sample data (sample → population) by resampling the sample data and performing inference about a sample from resampled data (resampled → sample). Since the actual population remains unknown, the true error in a sample statistic is similarly unknown. However, in bootstrap resamples, the 'population' is in fact the known sample, making the quality of inference from resampled data measurable [1]. The accuracy of inferences regarding the empirical distribution Ĵ using resampled data can be directly assessed, and if Ĵ constitutes a reasonable approximation of the true distribution J, then the quality of inference on J can be similarly inferred.

Contrast with Parametric Inference

Traditional parametric inference depends on specifying a model for the data-generating process and the concept of repeated sampling. For example, when estimating a mean, classical approaches typically assume data arise from a normal distribution or rely on the Central Limit Theorem for large sample sizes. The sample mean then follows a normal distribution with a standard error equal to the standard deviation divided by the square root of the sample size. Similar approaches extend to regression coefficients, which often assume normally distributed errors [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Parametric and Bootstrap Inference Approaches

| Feature | Parametric Inference | Bootstrap Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Assumptions | Requires strong distributional assumptions (e.g., normality, homoscedasticity) | Requires minimal assumptions; primarily that sample represents population |

| Computational Demand | Low; uses analytical formulas | High; requires repeated resampling and estimation |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple when formulas exist; impossible for complex statistics | Consistent approach applicable to virtually any statistic |

| Accuracy | Exact when assumptions hold; biased/misleading when assumptions violated | Often more accurate in finite samples; asymptotically consistent |

Parametric procedures work exceedingly well when their assumptions are met but can produce biased and misleading inferences when these assumptions are violated. The bootstrap circumvents these limitations by empirically estimating the sampling distribution without requiring strong parametric assumptions, making it particularly valuable in practical research situations where data may not conform to theoretical distributions [12].

The Bootstrap Algorithm: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Fundamental Resampling Process

The non-parametric bootstrap algorithm involves the following core steps, which can be implemented for virtually any statistical estimator [12] [1] [6]:

- Original Sample Collection: Draw a sample of size N from the population in the usual manner. This constitutes the original observed dataset.

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: Draw a bootstrap sample of size N from the original data by sampling with replacement. This critical step ensures that each observation from the original dataset may appear zero, one, or multiple times in the bootstrap sample.

- Model Fitting: Compute and retain the statistic of interest (e.g., mean, regression coefficient, mediated effect) using the bootstrap sample.

- Repetition: Repeat steps 2 and 3 a large number of times (typically 1,000 or more) to create an empirical distribution of the bootstrap estimates.

- Inference: Use this empirical bootstrap distribution to compute standard errors, confidence intervals, and bias estimates.

The following diagram illustrates this fundamental workflow:

Bootstrap Model Validation Protocol

For model validation, the bootstrap algorithm extends to evaluate predictive performance and correct for optimism bias. The following detailed protocol adapts the approach demonstrated in the birth weight prediction example [6]:

Table 2: Bootstrap Model Validation Protocol

| Step | Action | Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fit model M to original dataset D | Establish baseline performance | Use appropriate modeling technique for research question |

| 2 | Calculate performance metric θ on D | Measure apparent performance | Use relevant metric (e.g., Somers' D, AUC, R²) |

| 3 | Generate bootstrap sample Db by resampling D with replacement | Create training dataset | Maintain original sample size N in each bootstrap sample |

| 4 | Fit model Mb to bootstrap sample Db | Estimate model on resampled data | Use identical model structure as original model |

| 5 | Calculate performance metric θb train on Db | Measure performance on bootstrap training data | Use identical metric calculation method |

| 6 | Calculate performance metric θb test on original data D | Measure performance on original data | Assess degradation when applied to independent data |

| 7 | Compute optimism Ob = θb train - θb test | Quantify bootstrap optimism | Positive difference indicates overfitting |

| 8 | Repeat steps 3-7 B times (B ≥ 200) | Stabilize optimism estimate | Higher B reduces Monte Carlo variation |

| 9 | Calculate average optimism Ô = (1/B)ΣOb | Estimate expected optimism | Average across all bootstrap samples |

| 10 | Compute validated performance θval = θ - Ô | Correct for optimism | Produces bias-corrected performance estimate |

The following diagram visualizes this validation protocol, highlighting the crucial comparison between training and test performance:

Practical Implementation: A Case Study in Medical Research

Experimental Context and Dataset

To illustrate the bootstrap process in a clinically relevant context, we consider the birth weight prediction example from the UVA Library tutorial [6]. This study aims to develop a logistic regression model for predicting low infant birth weight (defined as < 2.5 kg) based on maternal characteristics. The dataset includes:

low: indicator of birth weight less than 2.5 kg (binary outcome)ht: history of maternal hypertension (binary predictor)ptl: previous premature labor (binary predictor)lwt: mother's weight in pounds at last menstrual period (continuous predictor)

The initial model appears statistically significant with multiple "significant" coefficients, but requires validation to assess its potential performance on future patients.

Application of Bootstrap Validation

Following the protocol outlined in Section 3.2, we implement bootstrap validation for the birth weight prediction model:

- The apparent performance (Somers' D = 0.438, c-index = 0.719) is calculated on the original data.

- After 200 bootstrap resamples, the average optimism is estimated to be 0.013.

- The bias-corrected performance is Somers' D = 0.438 - 0.013 = 0.425.

This validated performance measure indicates that the model's predictive ability, while still respectable, is approximately 3% lower than suggested by the apparent performance. This correction provides a more realistic expectation of how the model will perform in clinical practice [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Bootstrap Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary platform for statistical computing and graphics | Comprehensive bootstrap implementation via boot package |

boot Package |

Specialized R library for bootstrap methods | boot(data, statistic, R) function for efficient resampling |

| Custom Resampling Function | User-defined function calculating statistic of interest | Function specifying model fitting and performance calculation |

| Performance Metrics | Quantification of model discrimination/accuracy | Somers' D, c-index (AUC), R², prediction error |

| High-Performance Computing | Computational resources for intensive resampling | Parallel processing to reduce computation time for large B |

Advanced Considerations in Bootstrap Applications

Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

The bootstrap distribution enables construction of confidence intervals through several approaches, each with particular advantages [12]:

- Percentile Method: Directly uses appropriate percentiles (e.g., 2.5th and 97.5th for 95% CI) of the bootstrap distribution. This method is straightforward but may have coverage issues if the distribution is biased.

- Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCa): Adjusts for bias and skewness in the bootstrap distribution, providing more accurate coverage in many practical situations.

For the birth weight model, a percentile bootstrap confidence interval for the validated Somers' D would be constructed by identifying the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bias-corrected performance estimates across all bootstrap samples.

Addressing Dependent Data Structures

Standard bootstrap procedures assume independent observations, which is frequently violated in research designs with clustering or repeated measures. Specialized bootstrap variants address these limitations [12]:

- Cluster Bootstrap: Resamples entire clusters rather than individual observations to preserve within-cluster correlation structure.

- Block Bootstrap: Resamples blocks of consecutive observations to maintain time-dependent structure in time series data.

- Stratified Bootstrap: Conducts resampling within predefined strata to ensure representation across important subpopulations.

Discussion and Interpretation Guidelines

Advantages and Limitations

The bootstrap methodology offers significant advantages for model validation in research contexts [12] [1]:

- Distribution-free Inference: Does not require specifying a functional form for the population distribution, making it robust when normality assumptions are questionable.

- General Applicability: Works for a wide range of statistics, including complex estimands like indirect effects in mediation analysis or machine learning algorithm performance.

- Implementation Accessibility: With modern statistical software, implementation often requires just a few lines of code.

However, researchers must acknowledge important limitations:

- Sample Representativeness: The bootstrap treats the sample as a proxy for the population; any biases in the original sample will propagate through the bootstrap distribution.

- Computational Intensity: The procedure can be computationally demanding, especially for large datasets or complex models, though this is diminishing with advancing computing power.

- Small Sample Performance: In very small samples, the bootstrap may give misleading results due to limited sampling possibilities.

- Dependent Data: Naïve application to correlated data structures can underestimate variability unless modified approaches are used.

Reporting Standards for Bootstrap Analyses

When reporting bootstrap results in scientific publications, researchers should include:

- The specific bootstrap variant used (e.g., non-parametric case resampling)

- The number of bootstrap samples (B)

- The random seed for reproducibility

- The original sample size and any relevant data structure

- Both apparent and validated performance measures

- Bootstrap confidence intervals for key parameters

For the birth weight case study, appropriate reporting would state: "We validated the prediction model using 200 non-parametric bootstrap samples with random seed 222. The apparent Somers' D of 0.438 was optimism-corrected to 0.425, suggesting modest overfitting."

The bootstrap process of resampling, model fitting, and performance estimation represents a fundamental advancement in statistical practice, converting theoretical inference problems into computationally tractable solutions. Through empirical approximation of sampling distributions, the bootstrap enables robust model validation and accuracy assessment with minimal parametric assumptions. The method has proven particularly valuable in medical and pharmaceutical research contexts where data may be limited, models complex, and traditional assumptions questionable.

When implemented according to the protocols outlined in this document and interpreted with appropriate understanding of its limitations, bootstrap validation provides researchers with powerful tools for assessing model performance and quantifying uncertainty. As computational resources continue to expand, bootstrap methods will likely play an increasingly central role in ensuring the validity and reliability of statistical models in drug development and biomedical research.

The Concept of Optimism Bias in Model Performance and How Bootstrap Quantifies It

In statistical prediction models, optimism bias refers to the systematic overestimation of a model's performance when it is evaluated on the same data used for its training, compared to its actual performance on new, unseen data [23]. This overfitting phenomenon occurs because models can capture not only the underlying true relationship between predictors and outcome but also the random noise specific to the training sample. The "apparent" performance metrics, calculated on the training dataset, are therefore inherently optimistic and do not reflect how the model will generalize to future populations [23] [6]. In clinical prediction models, which are crucial for diagnosis and prognosis, this bias can lead to overconfident and potentially harmful decisions if not properly corrected [23].

The Bootstrap Principle for Quantifying Optimism

Bootstrap resampling provides a powerful internal validation method to estimate and correct for optimism bias without requiring a separate, held-out test dataset. The core idea is to use the original dataset as a stand-in for a future population [24]. By repeatedly resampling with replacement from the original data, the bootstrap process mimics the drawing of new samples from the same underlying population. The key insight of the optimism-adjusted bootstrap is that a model fitted on a bootstrap sample will overfit to that sample in a way analogous to how the original model overfits to the original dataset. The difference in performance between the bootstrap sample and the original dataset provides a direct, computable estimate of the optimism for each bootstrap replication [23] [6] [24]. The average of these optimism estimates across many replications is then subtracted from the original model's apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected estimate of future performance [6] [24].

Comparative Effectiveness of Bootstrap Methods

Several bootstrap-based bias correction methods exist, with the most common being Harrell's bias correction, the .632 estimator, and the .632+ estimator [23]. Their comparative performance varies depending on the sample size, event fraction, and model-building strategy.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bootstrap Optimism Correction Methods

| Method | Recommended Context | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harrell's Bias Correction | Relatively large samples (EPV ≥ 10); Conventional logistic regression [23] | Widely adopted and easily implementable (e.g., via rms package in R) [23] |

Can exhibit overestimation biases in small samples or with large event fractions [23] |

| .632 Estimator | Similar to Harrell's method in large sample settings [23] | - | Can exhibit overestimation biases in small samples or with large event fractions [23] |

| .632+ Estimator | Small sample settings; Rare event scenarios [23] | Performs relatively well under small sample settings; Bias is generally small [23] | Can have slight underestimation bias with very small event fractions; RMSE can be larger when used with regularized estimation methods (e.g., ridge, lasso) [23] |

Abbreviation: EPV, Events Per Variable.

Table 2: Impact of Model-Building Strategy on Bootstrap Correction

| Model Building Strategy | Impact on Bootstrap Optimism Correction |

|---|---|

| Conventional Logistic Regression (ML) | The three bootstrap methods are comparable with low bias when EPV ≥ 10 [23] |