Bridging the Digital and the Physical: A Framework for Validating Computational Predictions with Experimental Data in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of comparing computational predictions with experimental data.

Bridging the Digital and the Physical: A Framework for Validating Computational Predictions with Experimental Data in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of comparing computational predictions with experimental data. As computational methods like AI and machine learning become central to accelerating discovery, establishing their credibility through rigorous validation is paramount. We explore the foundational principles of verification and validation (V&V) in computational biology, detail advanced methodological frameworks for integration, address common challenges and optimization strategies, and present comparative analysis techniques for robust model assessment. By synthesizing insights from recent case studies and emerging trends, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more reliable, interpretable, and impactful computational tools that successfully transition from in-silico insights to real-world applications.

The Critical Imperative: Why Validating Computational Models is Non-Negotiable in Modern Science

Verification and Validation (V&V) are foundational processes in scientific and engineering disciplines, serving as critical pillars for establishing the credibility of computational models and systems. Within the context of research that compares computational predictions with experimental data, these processes ensure that models are both technically correct and scientifically relevant. The core distinction is elegantly summarized by the enduring questions: Verification asks, "Are we solving the equations right?" while Validation asks, "Are we solving the right equations?" [1]. In other words, verification checks the computational accuracy of the model implementation, and validation assesses the model's accuracy in representing real-world phenomena [2] [3].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these two concepts, detailing their methodologies, applications, and roles in the research workflow.

Core Conceptual Differences

The following table summarizes the fundamental distinctions between verification and validation, which are often conducted as sequential, complementary activities [3].

| Aspect | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | "Are we building the product right?" [4] [5] [6] or "Are we solving the equations right?" [1] | "Are we building the right product?" [4] [5] [6] or "Are we solving the right equations?" [1] |

| Objective | Confirm that a product, service, or system complies with a regulation, requirement, specification, or imposed condition [2] [7]. It ensures the model is built correctly. | Confirm that a product, service, or system meets the needs of the customer and other identified stakeholders [2]. It ensures the right model has been built for its intended purpose. |

| Primary Focus | Internal consistency: Alignment with specifications, design documents, and mathematical models [4] [5]. | External accuracy: Fitness for purpose and agreement with experimental data [4] [5] [8]. |

| Timing in Workflow | Typically occurs earlier in the development lifecycle, often before validation [4] [6]. It can begin as soon as there are artifacts (e.g., documents, code) to review [5]. | Typically occurs later in the lifecycle, after verification, when there is a working product or prototype to test [4] [5]. |

| Methods & Techniques | Static techniques such as reviews, walkthroughs, inspections, and static code analysis [4] [5] [6]. | Dynamic techniques such as testing the product in real or simulated environments, user acceptance testing, and clinical evaluations [4] [5] [8]. |

| Error Focus | Prevention of errors by finding bugs early in the development stage [4] [6]. | Detection of errors or gaps in meeting user needs and intended uses [6]. |

| Basis of Evaluation | Against specified design requirements and specifications (subjective to the documented rules) [2] [7]. | Against experimental data and intended use in the real world (objective, empirical evidence) [2] [1] [8]. |

The Logical Relationship and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical sequence and primary focus of V&V activities within a research and development lifecycle.

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

A robust V&V plan is integral to the study design from its inception [1]. The protocols below outline standard methodologies for both processes.

Verification Protocols

Verification employs static techniques to assess artifacts without executing the code or model [5]. Its goal is to identify numerical errors, such as discretization error and code mistakes, ensuring the mathematical equations are solved correctly [1].

- Requirements Reviews: A systematic analysis of requirement documents for clarity, completeness, feasibility, and testability. This often involves peer reviews and the creation of traceability matrices [9] [5].

- Design & Code Walkthroughs: A structured, step-by-step presentation and discussion of design documents or source code by the author to a group of reviewers. The goal is to detect errors, validate logic, and ensure adherence to standards [9] [5].

- Code Inspections: A more formal and rigorous peer review process than a walkthrough. It uses checklists to search for specific types of errors (e.g., security vulnerabilities, logic flaws, standards non-compliance) in code or design artifacts [9] [5].

- Static Code Analysis: The use of automated tools (e.g., SonarCube, LINTing) to analyze source code for patterns indicative of bugs, security weaknesses, or code "smells" without actually executing the program [5].

- Unit Testing: The process of testing individual units or components of code in isolation to verify that each part performs as intended [9] [5].

Validation Protocols

Validation uses dynamic techniques that involve running the software or model and comparing its behavior to empirical data. It assesses modeling errors arising from assumptions in the mathematical representation of the physical problem (e.g., in geometry, boundary conditions, or material properties) [1].

- Validation Testing Plan: The process begins with defining a plan that specifies the experimental data ("gold standard") used for comparison, the conditions under which comparisons will be made, and the metrics or tolerances for determining "acceptable agreement" [1].

- Benchmarking Against Experimental Data: The core of validation involves executing the computational model under defined conditions and systematically comparing its outputs with results from physical experiments [1] [3]. This is often done for multiple cases, including normal and extreme operating conditions [3].

- User Acceptance Testing (UAT): In software contexts, this involves having end-users test the software in a realistic environment to confirm it meets their needs and is fit for its intended purpose [4] [9].

- Clinical Evaluation: For medical devices and drug development, this is a critical validation activity. It involves generating objective evidence through clinical investigations and literature reviews to confirm that the device or product achieves its intended purpose safely and effectively in the target population [8].

- Usability Validation (Summative Usability Testing): This test evaluates whether specified users can achieve the intended purpose of a product safely and effectively in its specified use context [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions in conducting verification and validation, particularly in computationally driven research.

| Item | Primary Function in V&V |

|---|---|

| Static Code Analysis Tools (e.g., SonarCube, LINTing) [5] | Automated software tools that scan source code to identify potential bugs, vulnerabilities, and compliance with coding standards, crucial for the verification process. |

| Unit Testing Frameworks (e.g., NUnit, MSTest) [5] | Software libraries that allow developers to write and run automated tests on small, isolated units of code to verify their correctness. |

| Experimental Datasets ("Gold Standard") [1] | Empirical data collected from well-controlled physical experiments, which serve as the benchmark for validating computational model predictions. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Computational tools used to simulate physical phenomena. The models created require rigorous V&V against experimental data to establish credibility [1]. |

| System Modeling & Simulation Platforms | Software environments for building and executing computational models of complex systems, which are the primary subjects of the V&V process. |

| Reference (Validation) Prototypes | Physical artifacts or well-documented standard cases used to provide comparative data for validating specific aspects of a computational model's output. |

| Requirements Management Tools | Software that helps maintain traceability between requirements, design specifications, test cases, and defects, which is essential for both verification and auditability [5]. |

| 2-cyano-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)acetamide | 2-cyano-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)acetamide, CAS:15029-40-0, MF:C5H8N2O2, MW:128.13 g/mol |

| 4-(Aminomethyl)-3-methylbenzonitrile | 4-(Aminomethyl)-3-methylbenzonitrile, MF:C9H10N2, MW:146.19 g/mol |

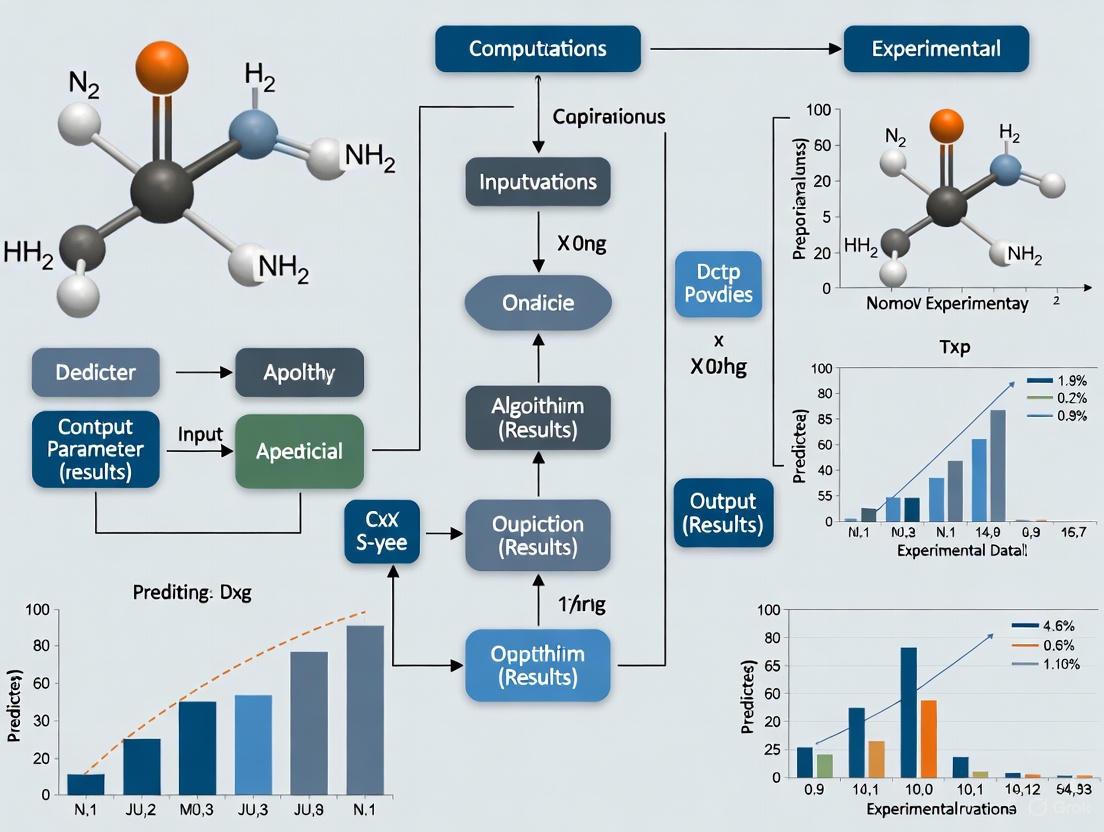

Visualizing the Integrated V&V Process

A comprehensive research study tightly couples V&V with the overall experimental design [1]. The following diagram maps this integrated process, highlighting how verification and validation activities interact with computational and experimental workstreams to assess different types of error.

Verification and Validation are distinct but inseparable processes that form the bedrock of credible computational research. For scientists and drug development professionals, a rigorous application of V&V is not optional but a mandatory practice to ensure that models and simulations provide accurate, reliable, and meaningful predictions. By systematically verifying that equations are solved correctly and validating that the right equations are being solved against robust experimental data, researchers can bridge the critical gap between computational theory and practical, real-world application, thereby enabling confident decision-making.

The process of bringing a new drug to market is notoriously complex, time-consuming, and costly, with an average timeline of 10–13 years and a cost ranging from $1–2.3 billion for a single successful candidate [10]. This high attrition rate, coupled with a decline in return-on-investment from 10.1% in 2010 to 1.8% in 2019, has driven the industry to seek more efficient and reliable methods [10]. In response, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative forces, compressing early-stage research timelines and expanding the chemical and biological search spaces for novel drug candidates [11].

These computational approaches promise to bridge the critical gap between basic scientific research and successful patient outcomes by improving the predictivity of every stage in the drug discovery pipeline. However, the ultimate value of these sophisticated predictions hinges on their rigorous experimental validation and demonstrated ability to generalize to real-world scenarios. This guide provides an objective comparison of computational prediction methodologies and their experimental validation frameworks, offering drug development professionals a clear overview of the tools and protocols defining modern R&D.

The Evolving Landscape of AI in Drug Discovery

The global machine learning in drug discovery market is experiencing significant expansion, driven by the growing incidence of chronic diseases and the rising demand for personalized medicine [12]. The market is segmented by application, technology, and geography, with key trends outlined below.

Table 1: Key Market Trends and Performance Metrics in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Segment | Dominant Trend | Key Metric | Emerging/Fastest-Growing Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application Stage | Lead Optimization | ~30% market share (2024) [12] | Clinical Trial Design & Recruitment [12] |

| Algorithm Type | Supervised Learning | 40% market share (2024) [12] | Deep Learning [12] |

| Deployment Mode | Cloud-Based | ~70% revenue share (2024) [12] | Hybrid Deployment [12] |

| Therapeutic Area | Oncology | ~45% market share (2024) [12] | Neurological Disorders [12] |

| End User | Pharmaceutical Companies | 50% revenue share (2024) [12] | AI-Focused Startups [12] |

| Region | North America | 48% revenue share (2024) [12] | Asia Pacific [12] |

Several AI-driven platforms have successfully transitioned from theoretical promise to tangible impact, advancing novel candidates into clinical trials. The approaches and achievements of leading platforms are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms (2025 Landscape)

| Company/Platform | Core AI Approach | Key Clinical-Stage Achievements | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI for small-molecule design; "Centaur Chemist" model integrating human expertise [11]. | First AI-designed drug (DSP-1181 for OCD) to Phase I (2020); multiple candidates in oncology and inflammation [11]. | Design cycles ~70% faster, requiring 10x fewer synthesized compounds; a CDK7 inhibitor candidate achieved with only 136 compounds synthesized [11]. |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI for target discovery and molecular design [11]. | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug candidate progressed from target discovery to Phase I in 18 months [11]. | Demonstrated radical compression of traditional 5-year discovery and preclinical timelines [11]. |

| Recursion | AI-driven phenotypic screening and analysis of cellular images [11]. | Pipeline of candidates from its platform, leading to merger with Exscientia in 2024 [11]. | Combines high-throughput wet-lab data with AI analysis for biological validation [11]. |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge-graph-driven target discovery [11]. | Advanced candidates from its target identification platform into clinical stages [11]. | Uses AI to mine scientific literature and data for novel target hypotheses [11]. |

| Schrödinger | Physics-based simulations combined with ML [11]. | Multiple partnered and internal programs advancing through clinical development [11]. | Leverages first-principles physics for high-accuracy molecular modeling [11]. |

Critical Need: Bridging the Computational-Experimental Gap

Despite the promising acceleration, a significant challenge remains: the generalizability gap of ML models. As noted in recent research, "current ML methods can unpredictably fail when they encounter chemical structures that they were not exposed to during their training, which limits their usefulness for real-world drug discovery" [13]. This underscores the non-negotiable role of experimental validation in confirming the biological activity, safety, and efficacy of computationally derived candidates [14].

Validation moves beyond simple graphical comparisons and requires quantitative validation metrics that account for numerical solution errors, experimental uncertainties, and the statistical character of data [15]. The integration of computational and experimental domains creates a synergistic cycle: computational models generate testable hypotheses and prioritize candidates, while experimental data provides ground-truth validation and feeds back into refining and retraining the models for improved accuracy [14] [16].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Tools & Validation Protocols

Predictive Tools for Physicochemical and Toxicokinetic Properties

Ensuring the safety and efficacy of chemicals requires the assessment of critical physicochemical (PC) and toxicokinetic (TK) properties, which dictate a compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profile [17]. Computational methods are vital for predicting these properties, especially with trends reducing experimental approaches.

A comprehensive 2024 benchmarking study evaluated twelve software tools implementing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models against 41 curated validation datasets [17]. The study emphasized the models' performance within their defined applicability domain (AD).

Table 3: Benchmarking Results of PC and TK Prediction Tools [17]

| Property Category | Representative Properties | Overall Predictive Performance | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical (PC) | LogP, Water Solubility, pKa | R² average = 0.717 [17] | Models for PC properties generally outperformed those for TK properties. |

| Toxicokinetic (TK) | Metabolic Stability, CYP Inhibition, Bioavailability | R² average = 0.639 (Regression); Balanced Accuracy = 0.780 (Classification) [17] | Several tools exhibited good predictivity across different properties and were identified as recurring optimal choices. |

The study concluded that the best-performing models offer robust tools for the high-throughput assessment of chemical properties, providing valuable guidance to researchers and regulators [17].

A Rigorous Protocol for Evaluating Generalizability in Binding Affinity Prediction

A key challenge in structure-based drug design is accurately and rapidly estimating the strength of protein-ligand interactions. A 2025 study from Vanderbilt University addressed the "generalizability gap" of ML models through a targeted model architecture and a rigorous evaluation protocol [13].

Experimental Protocol for Generalizability Assessment [13]:

- Model Architecture: A task-specific model was designed to learn not from the entire 3D structure of the protein and ligand, but from a simplified representation of their interaction space, capturing the distance-dependent physicochemical interactions between atom pairs. This forces the model to learn transferable principles of molecular binding.

- Validation Benchmark: To simulate a real-world scenario, the training and testing sets were structured to answer: "If a novel protein family were discovered tomorrow, would our model be able to make effective predictions for it?" This was achieved by leaving out entire protein superfamilies and all their associated chemical data from the training set, creating a challenging and realistic test of the model's ability to generalize.

This protocol revealed that contemporary ML models performing well on standard benchmarks can show a significant performance drop when faced with novel protein families, highlighting the need for more stringent evaluation practices in the field [13].

Integrative Validation: A Case Study on Piperlongumine for Colorectal Cancer

The following case study on Piperlongumine (PIP), a natural compound, illustrates a multi-tiered framework for integrating computational predictions with experimental validation to identify and validate therapeutic agents [16].

Diagram 1: Integrative validation workflow for a therapeutic agent.

Detailed Experimental Protocols from the PIP Case Study [16]:

Computational Target Identification:

- Dataset Mining: Three independent colorectal cancer (CRC) transcriptomic datasets (GSE33113, GSE49355, GSE200427) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

- DEG Identification: Differential gene expression analysis was performed using GEO2R with criteria set at absolute log│FC│ > 1 and p-value < 0.05 to identify deregulated genes between tumor and normal samples.

- Hub-Gene Prioritization: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed from the DEGs using the STRING database, and hub genes (TP53, CCND1, AKT1, CTNNB1, IL1B) were identified using CytoHubba in Cytoscape.

- Molecular Docking: The binding affinities of PIP to the protein products of the hub genes were evaluated using AutoDock Vina to validate potential direct interactions.

In Vitro Experimental Validation:

- Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity (MTT) Assay: Human colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116 and HT-29) were cultured in recommended media. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates, treated with varying concentrations of PIP for 24-72 hours. MTT reagent was added, and after solubilization, the absorbance was measured at 570 nm to determine cell viability and IC50 values.

- Wound Healing/Scratch Migration Assay: Cells were grown to confluence in culture plates. A sterile pipette tip was used to create a scratch. Cells were washed and treated with PIP. Images of the scratch were taken at 0, 24, and 48 hours to measure migration inhibition.

- Apoptosis Analysis by Flow Cytometry: PIP-treated and untreated cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) using an apoptosis detection kit. The stained cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer to distinguish between live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations.

- Gene Expression Validation (qRT-PCR): Total RNA was extracted from treated and control cells using TRIzol reagent. cDNA was synthesized, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed with gene-specific primers for the hub genes. Expression levels were normalized to a housekeeping gene (e.g., GAPDH) and analyzed using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method.

This integrative study demonstrated that PIP targets key CRC-related pathways by upregulating TP53 and downregulating CCND1, AKT1, CTNNB1, and IL1B, resulting in dose-dependent cytotoxicity, inhibition of migration, and induction of apoptosis [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the experimental validation protocols described in this field.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines (e.g., HCT116, HT-29) | In vitro models for evaluating compound efficacy, cytotoxicity, and mechanism of action. | Testing dose-dependent cytotoxicity of Piperlongumine [16]. |

| MTT Assay Kit | Colorimetric assay to measure cell metabolic activity, used as a proxy for cell viability and proliferation. | Determining IC50 values of drug candidates [16]. |

| Annexin V-FITC / PI Apoptosis Kit | Flow cytometry-based staining to detect and quantify apoptotic and necrotic cell populations. | Confirming induction of apoptosis by a drug candidate [16]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents (Primers, Reverse Transcriptase, SYBR Green) | Quantitative measurement of gene expression changes in response to treatment. | Validating the effect of a compound on hub-gene expression (e.g., TP53, AKT1) [16]. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Method for validating direct target engagement of a drug within intact cells or tissues. | Confirming dose-dependent stabilization of a target protein (e.g., DPP9) in a physiological context [18]. |

| 3-Amino-5-(methylsulfonyl)benzoic acid | 3-Amino-5-(methylsulfonyl)benzoic Acid | 3-Amino-5-(methylsulfonyl)benzoic acid is a high-purity benzoic acid derivative for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-Benzyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)piperidin-4-ol | 1-Benzyl-3-(trifluoromethyl)piperidin-4-ol, CAS:373603-87-3, MF:C13H16F3NO, MW:259.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The integration of computational and experimental domains is being further accelerated by several key trends. There is a growing emphasis on using real-world data (RWD) from electronic health records, wearable devices, and patient registries to complement traditional clinical trials [10] [19]. When analyzed with causal machine learning (CML) techniques, RWD can help estimate drug effects in broader populations, identify responders, and support adaptive trial designs [10]. Experts predict a significant shift towards hybrid clinical trials, which combine traditional site-based visits with decentralized elements, facilitated by AI-driven protocol optimization and patient recruitment tools [19].

Furthermore, the field is moving towards more rigorous biomarker development, particularly in complex areas like psychiatry, where objective measures like event-related potentials are being validated as interpretable biomarkers for clinical trials [19]. Finally, as demonstrated in the Vanderbilt study, the focus is shifting from pure predictive accuracy to building generalizable and dependable AI models that do not fail unpredictably when faced with novel chemical or biological spaces [13]. This evolution points to a future where computational predictions are not only faster but also more robust, interpretable, and tightly coupled with clinical and experimental evidence.

{ dropcap}TThe scientific method is being augmented by AI systems that can learn from diverse data sources, plan experiments, and learn from the results. The CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists) platform, for instance, uses multimodal information—from scientific literature and chemical compositions to microstructural images—to optimize materials recipes and plan experiments conducted by robotic equipment [20]. This represents a move away from traditional, sequential research workflows towards a more integrated, AI-driven cycle.

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow of such a closed-loop, AI-driven discovery system.

{ dropcap}TThis new paradigm creates a critical bottleneck: the need to validate AI-generated predictions and discoveries with robust experimental data. As one analysis notes, "AI will generate knowledge faster than humans can validate it," highlighting a central challenge in modern computational-experimental research [21]. Furthermore, studies show that early decisions in data preparation and model selection interact in complex ways, meaning suboptimal choices can lead to models that fail to generalize to real-world experimental conditions [22]. The following section details the protocols for such validation.

Protocols for Validating AI-Driven Discoveries

Validating an AI system's predictions requires a rigorous, multi-stage process. The goal is to move beyond simple in-silico accuracy and ensure the finding holds up under physical experimentation. The methodology for the CRESt system provides a template for this process [20]. The validation must be data-centric, recognizing that over 50% of model inaccuracies can stem from data errors [23].

1. High-Throughput Experimental Feedback Loop:

- Objective: To physically test AI-proposed material recipes and feed results back to improve the model.

- Methodology: The AI system suggests a batch of material chemistries. A liquid-handling robot and a carbothermal shock system synthesize the proposed materials. An automated electrochemical workstation then tests their performance (e.g., as a fuel cell catalyst). Characterization equipment, including electron microscopy, analyzes the resulting material's structure [20].

- Validation Cue: The system uses computer vision to monitor experiments, detect issues like sample misplacement, and suggest corrections, directly addressing reproducibility challenges [20].

2. Data-Centric Model Validation and Performance Benchmarking:

- Objective: To ensure the AI model generalizes well and is not overfitted to its training data.

- Methodology: This involves techniques like K-Fold Cross-Validation, where the data is partitioned into multiple folds, each used as a validation set. Stratified K-Fold is used for classification to preserve class distribution. For temporal data, a Time Series Split is essential to maintain chronological order [24] [25].

- Key Metrics: Beyond accuracy, metrics like precision (minimizing false positives), recall (minimizing false negatives), and the F1 score (their harmonic mean) are critical. The ROC-AUC score evaluates the model's ability to distinguish between classes [24] [25].

3. Real-World Stress Testing and Robustness Analysis:

- Objective: To expose the AI-discovered material to edge cases and stressful conditions that mimic real-world application.

- Methodology: This includes noise injection (adding random variations to inputs), testing with edge cases, evaluating performance with missing data, and checking for consistency in repeated predictions [25]. This simulates real-world imperfections and ensures the discovery is robust.

Comparative Performance: AI-Driven vs. Traditional Workflows

The quantitative output from platforms like CRESt demonstrates the tangible advantage of integrating AI directly into the experimental loop. The following table summarizes a comparative analysis of key performance indicators.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Research Methodologies in Materials Science

| Performance Metric | AI-Driven Discovery (e.g., CRESt) | Traditional Human-Led Research | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | High-throughput, robotic automation. | Manual, low-to-medium throughput. | CRESt explored >900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests in 3 months [20]. |

| Search Space Efficiency | Active learning optimizes the path to a solution. | Relies on researcher intuition and literature surveys. | CRESt uses Bayesian optimization in a knowledge-informed reduced space for efficient exploration [20]. |

| Discovery Output | Can identify novel, multi-element solutions. | Often focuses on incremental improvements. | Discovered an 8-element catalyst with a 9.3x improvement in power density per dollar over pure palladium [20]. |

| Reproducibility | Computer vision monitors for procedural deviations. | Prone to manual error and subtle environmental variations. | The system hypothesizes sources of irreproducibility and suggests corrections [20]. |

| Key Validation Metric | Power Density / Cost | Power Density / Cost | Record power density achieved with 1/4 the precious metals of previous devices [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for AI-Experimental Research

Bridging the digital and physical worlds requires a specific set of tools. This table details key solutions and their functions in a modern, AI-augmented lab.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Experimentation

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in AI-Driven Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Liquid-Handling Robot | Automates the precise mixing of precursor chemicals for high-throughput synthesis of AI-proposed material recipes [20]. |

| Carbothermal Shock System | Enables rapid synthesis of materials by subjecting precursor mixtures to very high temperatures for short durations, speeding up iteration [20]. |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | Systematically tests the performance of synthesized materials (e.g., as catalysts or battery components) without manual intervention [20]. |

| Automated Electron Microscope | Provides high-resolution microstructural images of new materials, which are fed back to the AI model for analysis and hypothesis generation [20]. |

| DataPerf Benchmark | A benchmark suite for data-centric AI development, helping researchers focus on improving dataset quality rather than just model architecture [26]. |

| Synthetic Data Pipelines | Generates artificial data to supplement real datasets when data is scarce, costly, or private, helping to overcome data scarcity for training AI models [24] [27]. |

| 1-Cyclopentylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid | 1-Cyclopentylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid, CAS:897094-32-5, MF:C11H19NO2, MW:197.27 g/mol |

| 2-(2-Azabicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-yl)ethanol | 2-(2-Azabicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-yl)ethanol, CAS:116585-72-9, MF:C8H15NO, MW:141.21 g/mol |

{ dropcap}TThe integration of AI into the scientific process is creating a new research paradigm where computational prediction and experimental validation are tightly coupled. Systems like CRESt demonstrate the immense potential, achieving discoveries at a scale and efficiency beyond traditional methods. The central challenge moving forward is not just building more powerful AIs, but establishing robust, standardized validation frameworks that can keep pace with AI-generated knowledge. Success will depend on a synergistic approach—leveraging AI's computational power and relentless throughput while relying on refined experimental protocols and irreplaceable human expertise to separate true discovery from mere digital promise.

In the rapidly evolving field of computational drug discovery, the transition from promising algorithm to peer-accepted tool hinges upon a single critical process: rigorous validation. As artificial intelligence and machine learning models demonstrate increasingly sophisticated capabilities, the scientific community's acceptance of these tools is contingent upon demonstrable evidence that they can accurately predict real-world biological outcomes. This comparative analysis examines how emerging computational platforms establish credibility through multi-faceted validation frameworks, contrasting their predictive performance against experimental data across diverse contexts.

The fundamental challenge facing computational researchers lies in bridging the gap between algorithmic performance on benchmark datasets and genuine scientific utility in biological systems. While impressive performance metrics on standardized tests may generate initial interest, sustained adoption by research scientists and drug development professionals requires confidence that in silico predictions will translate to in vitro and in vivo results [28] [29]. This analysis explores the validation methodologies that underpin credibility, focusing specifically on how comparative performance data against established methods and experimental verification creates the foundation for peer acceptance.

Methodological Frameworks for Computational Validation

Benchmarking Against Established Tools

Rigorous benchmarking against established computational methods represents the initial validation step for new tools. The DeepTarget algorithm, for instance, underwent systematic evaluation across eight distinct datasets of high-confidence drug-target pairs, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing tools such as RoseTTAFold All-Atom and Chai-1 in seven of eight test pairs [30]. This head-to-head comparison provides researchers with tangible performance metrics that contextualize a tool's capabilities within the existing technological landscape.

However, benchmark performance alone proves insufficient for establishing scientific credibility. The phenomenon of "benchmark saturation" occurs when leading models achieve near-perfect scores on standardized tests, eliminating meaningful differentiation [28]. Similarly, "data contamination" can artificially inflate performance metrics when training data inadvertently includes test questions, creating an illusion of capability that evaporates in novel production scenarios [28]. These limitations necessitate more sophisticated validation frameworks that extend beyond standardized benchmarks.

Experimental Validation Protocols

True credibility emerges from validation against experimental data, which typically follows a structured protocol:

- Computational Prediction: Researchers generate target predictions using the computational tool based on existing biological data.

- Experimental Design: Appropriate experimental systems are selected to test the computational predictions (e.g., cell-based assays, animal models).

- Hypothesis Testing: Specific, falsifiable hypotheses derived from computational predictions are tested experimentally.

- Result Comparison: Experimental outcomes are quantitatively compared against computational predictions.

- Iterative Refinement: Discrepancies between prediction and experiment inform model refinement.

This validation cycle transforms computational tools from black boxes into hypothesis-generating engines that drive experimental discovery. As observed in the DeepTarget case studies, this approach enabled researchers to experimentally validate that the antiparasitic agent pyrimethamine affects cellular viability by modulating mitochondrial function in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway—a finding initially generated computationally [30].

Prospective Validation in Real-World Contexts

The most rigorous form of validation involves prospective testing in real-world research contexts. This approach moves beyond retrospective analysis of existing datasets to evaluate how tools perform when making forward-looking predictions in complex, uncontrolled environments [29]. The gold standard for such validation is the randomized controlled trial (RCT), which applies the same rigorous methodology used to evaluate therapeutic interventions to the assessment of computational tools [29].

A recent RCT examining AI tools in software development yielded surprising results: experienced developers actually took 19% longer to complete tasks when using AI assistance compared to working without it, despite believing the tools made them faster [31]. This disconnect between perception and reality underscores the critical importance of prospective validation and highlights how anecdotal reports can dramatically overestimate practical utility in specialized domains.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Computational Drug Discovery Tools

| Tool/Method | Validation Approach | Performance Outcome | Experimental Confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepTarget [30] | Benchmark against 8 drug-target datasets; experimental case studies | Outperformed existing tools in 7/8 tests | Pyrimethamine mechanism confirmed via mitochondrial function assays |

| AI-HTS Integration [18] | Comparison of hit enrichment rates | 50-fold improvement in hit enrichment vs. traditional methods | Confirmed via high-throughput screening |

| MIDD Approaches [32] | Quantitative prediction accuracy for PK/PD parameters | Improved prediction accuracy for FIH dose selection | Clinical trial data confirmation |

| CETSA [18] | Target engagement quantification in intact cells | Quantitative measurement of drug-target engagement | Validation in rat tissue ex vivo and in vivo |

Case Study: DeepTarget Validation Methodology

Experimental Protocol for Predictive Validation

The validation of DeepTarget exemplifies a comprehensive approach to establishing computational credibility. The methodology employed in the published study involved multiple validation tiers [30]:

1. Benchmarking Phase:

- Eight distinct datasets of high-confidence drug-target pairs were utilized

- Performance was quantified using standardized accuracy metrics

- Comparisons were made against state-of-the-art tools (RoseTTAFold All-Atom, Chai-1)

2. Experimental Validation Phase:

- Two focused case studies were selected for experimental confirmation

- Pyrimethamine was evaluated for mechanisms beyond its known antiparasitic activity

- Ibrutinib was tested in BTK-negative solid tumors with EGFR T790 mutations

- Cellular viability assays and molecular profiling confirmed computational predictions

3. Predictive Expansion:

- The validated framework was applied to predict target profiles for 1,500 cancer drugs

- 33,000 natural product extracts were screened in silico

- Predictions were generated for mutation-specific drug sensitivities

This multi-layered approach demonstrates how computational tools can transition from benchmark performance to biologically relevant prediction systems. The pyrimethamine case study is particularly instructive: DeepTarget predicted previously unrecognized activity in mitochondrial function, which was subsequently confirmed experimentally, revealing new repurposing opportunities for an existing drug [30].

Signaling Pathways for Drug-Target Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow and biological pathways integrated in the DeepTarget approach for identifying primary and secondary drug targets:

Diagram 1: DeepTarget prediction workflow. This diagram illustrates the integration of diverse data types and the prediction of both primary and secondary targets that are subsequently validated experimentally.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Establishing credibility requires transparent reporting of quantitative performance metrics compared to existing alternatives. The following table summarizes key comparative data for computational drug discovery tools:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Computational Drug Discovery Methods

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Correlation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Target Prediction | DeepTarget [30] | 7/8 benchmark wins vs. competitors; predicts primary & secondary targets | High (mechanistically validated in case studies) | Requires diverse omics data for optimal performance |

| Structure-Based Screening | Molecular Docking (AutoDock) [18] | Binding affinity predictions; 50-fold hit enrichment improvement [18] | Moderate (varies by system) | Limited by structural data availability |

| AI-HTS Integration | Deep graph networks [18] | 4,500-fold potency improvement in optimized inhibitors | High (confirmed via synthesis & testing) | Requires substantial training data |

| Cellular Target Engagement | CETSA [18] | Quantitative binding measurements in intact cells | High (direct physical measurement) | Limited to detectable binding events |

| Model-Informed Drug Development | PBPK, QSP, ER modeling [32] | Improved FIH dose prediction accuracy | Moderate to High (clinical confirmation) | Complex model validation requirements |

Contextual Performance Factors

Tool performance varies significantly based on application context and biological system. The DeepTarget developers noted that their tool's superior performance in real-world scenarios likely stemmed from its ability to mirror actual drug mechanisms where "cellular context and pathway-level effects often play crucial roles beyond direct binding interactions" [30]. This contextual sensitivity highlights why multi-faceted validation across diverse scenarios proves essential for establishing generalizable utility.

Performance evaluation must also consider practical implementation factors. A study examining AI tools in open-source software development found that despite impressive benchmark performance, these tools actually slowed down experienced developers by 19% when working on complex, real-world coding tasks [31]. This performance-reality gap underscores how specialized domain expertise, high-quality standards, and implicit requirements can dramatically impact practical utility—considerations equally relevant to computational drug discovery.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Platforms

Successful implementation and validation of computational predictions requires specialized research tools and platforms. The following table details key solutions employed in the featured studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Provider/Type | Primary Function | Validation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| CETSA [18] | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay | Measure target engagement in intact cells | Confirm computational predictions of drug-target binding |

| DeepTarget Algorithm [30] | Open-source computational tool | Predict primary & secondary drug targets | Generate testable hypotheses for experimental validation |

| AutoDock [18] | Molecular docking simulation | Predict ligand-receptor binding interactions | Virtual screening prior to experimental testing |

| High-Content Screening Systems | Automated microscopy platforms | Multiparametric cellular phenotype assessment | Evaluate compound effects predicted computationally |

| Patient-Derived Models [29] | Xenografts/organoids | Maintain tumor microenvironment context | Test context-specific predictions in relevant biological systems |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms [18] | Proteomic analysis | Quantify protein expression and modification | Verify predicted proteomic changes from treatment |

| 1-(4-Aminophenyl)pyridin-1-ium chloride | 1-(4-Aminophenyl)pyridin-1-ium chloride|CAS 78427-26-6 | High-purity 1-(4-Aminophenyl)pyridin-1-ium chloride (CAS 78427-26-6) for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Benzyl 2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-phenylacetimidate | Benzyl 2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-phenylacetimidate, CAS:952057-61-3, MF:C15H12F3NO, MW:279.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways in Computational Validation

The validation of computational predictions frequently involves examining compound effects on key biological pathways. The following diagram illustrates a pathway validation workflow confirmed in the DeepTarget case studies:

Diagram 2: Pathway validation workflow. This diagram maps the pathway-level effects discovered through DeepTarget predictions and confirmed experimentally, demonstrating how computational tools can reveal previously unrecognized drug mechanisms.

Discussion: Toward Credible Computational Prediction

Synthesis of Validation Evidence

The establishment of credibility for computational tools in drug discovery emerges from the convergence of multiple validation approaches. Benchmark performance provides the initial evidence of technical capability, but must be supplemented with experimental confirmation in biologically relevant systems. The most compelling tools demonstrate utility across the discovery pipeline, from target identification through mechanism elucidation, with each successful prediction strengthening the case for broader adoption.

The evolving regulatory landscape further emphasizes the importance of robust validation frameworks. Initiatives like the FDA's INFORMED program represent efforts to create regulatory pathways for advanced computational approaches, while Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) frameworks provide structured approaches for integrating modeling and simulation into drug development and regulatory decision-making [32] [29]. These developments signal growing recognition of computational tools' potential, provided they meet evidence standards commensurate with their intended use.

Future Directions in Computational Validation

As computational methods continue to advance, validation frameworks must similarly evolve. Key challenges include:

- Addressing model scalability across diverse biological contexts and disease models

- Developing standardized validation protocols that enable meaningful cross-study comparisons

- Creating adaptive validation frameworks that accommodate rapidly evolving algorithms

- Establishing prospective validation cohorts to assess real-world predictive performance

The integration of artificial intelligence with experimental validation represents a particularly promising direction. As noted by researchers, "Improving treatment options for cancer and for related and even more complex conditions like aging will depend on us improving both our ways to understand the biology as well as ways to modulate it with therapies" [30]. This synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation will ultimately determine how computational tools transition from technical curiosities to essential components of the drug discovery toolkit.

For computational researchers seeking peer acceptance, the path forward is clear: rigorous benchmarking, transparent reporting, experimental collaboration, and prospective validation provide the foundation for credibility. By demonstrating consistent predictive performance across multiple contexts and linking computational insights to biological outcomes, new tools can establish the evidentiary foundation necessary for scientific acceptance and widespread adoption.

From Code to Lab Bench: Methodological Frameworks for Integrating Computation and Experimentation

In the field of data-driven science, particularly within biological and materials research, the integration of diverse data streams has become a critical methodology for accelerating discovery. The fundamental challenge lies in effectively combining multiple sources of information—from genomic data to scientific literature—to form coherent insights that outpace traditional single-modality approaches. Researchers currently face a strategic decision when designing their workflows: whether to allow algorithms to process data sources independently, to guide this process with human expertise and predefined rules, or to employ a selective search across possible integration methods. Each approach carries distinct advantages and limitations that impact the validity, efficiency, and translational potential of research outcomes, especially in high-stakes fields like drug development and materials science.

The core thesis of this comparison centers on evaluating how these integration strategies perform when computational predictions are ultimately validated against experimental data. This critical bridge between digital prediction and physical verification represents the ultimate test for any integration methodology. As computational methods grow more sophisticated, understanding the performance characteristics of each integration approach becomes essential for researchers allocating scarce laboratory resources and time. This guide objectively examines three strategic approaches to integration through the lens of experimental validation, providing comparative data and methodological details to inform research design decisions across scientific domains.

Comparative Framework: Three Integration Strategies

Defining the Integration Spectrum

The landscape of data integration strategies can be categorized into three distinct paradigms based on their operational philosophy and implementation. Independent Integration refers to approaches where different data types are processed separately according to their inherent structures before final integration, preserving the unique characteristics of each data modality throughout much of the analytical process. This approach often employs statistical frameworks that identify latent factors across datasets without imposing strong prior assumptions about relationships between data types.

In contrast, Guided Integration incorporates domain knowledge, experimental feedback, or predefined biological/materials principles directly into the integration process, creating a more directed discovery pathway that mirrors the hypothesis-driven scientific method. This approach often utilizes iterative cycles where computational predictions inform subsequent experiments, whose results then refine the computational models. Finally, Search-and-Select Integration involves systematically evaluating multiple integration methodologies or data combinations against performance criteria to identify the optimal strategy for a specific research question. This meta-integration approach acknowledges that no single method universally outperforms others across all datasets and research contexts.

Methodological Comparison

The three integration strategies differ fundamentally in their implementation requirements and analytical workflows. Independent integration methods typically employ dimensionality reduction techniques applied to each data type separately, followed by concatenation or similarity network fusion. These methods, such as MOFA+ and Similarity Network Fusion (SNF), require minimal prior knowledge but substantial computational resources for processing each data stream independently [33]. Guided integration approaches, exemplified by systems like CRESt (Copilot for Real-world Experimental Scientists), incorporate active learning frameworks where multimodal feedback—including literature insights, experimental results, and human expertise—continuously refines the search space and experimental design [20]. This creates a collaborative human-AI partnership where natural language communication enables real-time adjustment of research trajectories.

Search-and-select integration implements a benchmarking framework where multiple integration methods are systematically evaluated using standardized metrics across representative datasets. This approach requires creating comprehensive evaluation pipelines that assess methods based on clustering accuracy, clinical significance, robustness, and computational efficiency [33] [34]. The selection process may involve training multiple models with different loss functions and regularization strategies, then comparing their performance on validation metrics relevant to the specific research goals, such as biological conservation in single-cell data or power density in materials optimization [34].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Metrics Across Domains

Integration Performance in Cancer Subtyping

Independent integration methods have demonstrated particular strength in genomic classification tasks where preserving data-type-specific signals is crucial. In breast cancer subtyping, the statistical-based independent integration method MOFA+ achieved an F1 score of 0.75 when identifying cancer subtypes using a nonlinear classification model, outperforming other approaches in feature selection efficacy [35]. This performance advantage translated into biological insights, with MOFA+ identifying 121 relevant pathways compared to 100 pathways identified by deep learning-based methods, highlighting its ability to capture meaningful biological signals from complex multi-omics data [35].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Integration Methods in Cancer Subtyping

| Integration Method | Strategy Type | F1 Score (Nonlinear Model) | Pathways Identified | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ | Independent | 0.75 | 121 | Superior feature selection, biological interpretability |

| MOGCN | Independent | Lower than MOFA+ | 100 | Handles nonlinear relationships, captures complex patterns |

| SNF | Independent | Varies by cancer type | Not specified | Effective with clinical data integration, preserves data geometry |

| PINS | Search-and-Select | Varies by cancer type | Not specified | Robust to noise, handles data perturbations effectively |

The calibration of integration performance depends heavily on appropriate metric selection. For cancer subtyping, the Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) and Calinski-Harabasz Index (CHI) provide complementary assessments of cluster quality, with lower DBI values and higher CHI values indicating better separation of biologically distinct subtypes [35]. These metrics should be considered alongside clinical relevance measures, such as survival analysis significance and differential drug response correlations, to ensure computational findings translate to therapeutic insights.

Performance in Materials Discovery and Experimental Validation

Guided integration demonstrates distinct advantages in experimental sciences where physical synthesis and characterization create feedback loops for iterative improvement. In materials discovery applications, the CRESt system explored over 900 chemistries and conducted 3,500 electrochemical tests, discovering a catalyst material that delivered record power density in a fuel cell with just one-fourth the precious metals of previous devices [20]. This accelerated discovery—achieved within three months—showcased how guided integration can rapidly traverse complex experimental parameter spaces by incorporating robotic synthesis, characterization, and multimodal feedback into an active learning framework.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Guided Integration in Materials Science

| Performance Metric | Guided Integration (CRESt) | Traditional Methods | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistries explored | 900+ in 3 months | Significantly fewer | Not quantified |

| Electrochemical tests | 3,500 | Fewer due to time constraints | Not quantified |

| Power density per dollar | 9.3x improvement over pure Pd | Baseline | 9.3-fold |

| Precious metal content | 25% of previous devices | 100% (baseline) | 4x reduction |

The critical advantage of guided integration emerges in its reproducibility and debugging capabilities. By incorporating computer vision and visual language models, these systems can monitor experiments, detect procedural deviations, and suggest corrections—addressing the critical challenge of experimental irreproducibility that often plagues materials science research [20]. This capacity for real-time course correction creates a more robust discovery pipeline than what is typically achievable through purely computational approaches without experimental feedback.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Independent Integration in Cancer Subtyping

Implementing independent integration for genomic classification requires a systematic approach to data processing, integration, and validation. The following protocol outlines the key steps for applying independent integration methods like MOFA+ to cancer subtyping:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Obtain multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, epigenomics, microbiomics) from curated sources such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Perform batch effect correction using methods like ComBat or Harman to remove technical variations. Filter features, discarding those with zero expression in more than 50% of samples to reduce noise [35]. For the breast cancer analysis referenced, this resulted in 20,531 transcriptomic features, 1,406 microbiomic features, and 22,601 epigenomic features retained for analysis.

Model Training and Feature Selection: Implement MOFA+ using appropriate software packages (R v4.3.2 for referenced study). Train the model over 400,000 iterations with a convergence threshold to ensure stability. Select latent factors explaining a minimum of 5% variance in at least one data type. Extract feature loadings from the latent factor explaining the highest shared variance across all omics layers. Select top features based on absolute loadings (typically 100 features per omics layer) for downstream analysis [35].

Validation and Biological Interpretation: Evaluate the selected features using both linear (Support Vector Classifier with linear kernel) and nonlinear (Logistic Regression) models with five-fold cross-validation. Use F1 scores as the primary evaluation metric to account for imbalanced subtype distributions. Perform pathway enrichment analysis on transcriptomic features to assess biological relevance. Validate clinical associations by correlating feature expression with tumor stage, lymph node involvement, and survival outcomes using curated databases like OncoDB [35].

Protocol for Guided Integration in Materials Science

Guided integration combines computational prediction with experimental validation in an iterative cycle. The following protocol details the implementation of guided integration for materials discovery, based on the CRESt platform:

System Setup and Knowledge Base Construction: Deploy robotic equipment including liquid-handling robots, carbothermal shock synthesizers, automated electrochemical workstations, and characterization tools (electron microscopy, optical microscopy). Implement natural language interfaces to allow researcher interaction without coding. Construct a knowledge base by processing scientific literature to create embeddings of materials recipes and properties, then perform principal component analysis to define a reduced search space capturing most performance variability [20].

Active Learning Loop Implementation: Initialize with researcher-defined objectives (e.g., "find high-activity catalyst with reduced precious metals"). Use Bayesian optimization within the reduced knowledge space to suggest initial experimental candidates. Execute robotic synthesis and characterization according to predicted promising compositions. Incorporate multimodal feedback including literature correlations, microstructural images, and electrochemical performance data. Employ computer vision systems to monitor experiments and detect anomalies. Update models with new experimental results and researcher feedback to refine subsequent experimental designs [20].

Validation and Optimization: Conduct high-throughput testing of optimized materials (e.g., 3,500 electrochemical tests for fuel cell catalysts). Compare performance against benchmark materials and literature values. Perform characterization of optimal materials to understand structural basis for performance. Execute reproducibility assessments by comparing multiple synthesis batches and testing conditions [20].

Protocol for Search-and-Select Integration in Single-Cell Analysis

Search-and-select integration involves benchmarking multiple methods to identify the optimal approach for a specific dataset. The following protocol outlines this process for single-cell data integration:

Benchmarking Framework Establishment: Select diverse integration methods representing different strategies (similarity-based, dimensionality reduction, deep learning). Define evaluation metrics addressing both batch correction (e.g., batch ASW, iLISI) and biological conservation (e.g., cell-type ASW, cLISI, cell-type clustering metrics). Implement unified preprocessing pipelines to ensure fair comparisons [34].

Method Evaluation and Selection: Train each method with standardized hyperparameter optimization procedures (e.g., using Ray Tune framework). Evaluate methods across multiple datasets with varying complexities (e.g., immune cells, pancreas cells, bone marrow mononuclear cells). Visualize integrated embeddings using UMAP to qualitatively assess batch mixing and cell-type separation. Quantify performance using the selected metrics across all datasets. Rank methods based on composite scores weighted toward analysis priorities (e.g., prioritizing biological conservation over batch removal for exploratory studies) [34].

Validation and Implementation: Apply top-performing methods to the target dataset. Assess robustness through sensitivity analyses. Validate biological findings through differential expression analysis, trajectory inference, or other domain-specific validation techniques. Document the selected method and parameters for reproducibility [34].

Visualizing Integration Strategies: Workflows and Pathways

Independent Integration Workflow

Guided Integration Workflow

Search-and-Select Integration Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integration Methods

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Compatible Strategy | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ Software | Statistical integration of multi-omics data | Independent | Identifies latent factors across omics datasets [35] |

| CRESt Platform | Human-AI collaborative materials discovery | Guided | Integrates literature, synthesis, and testing [20] |

| scIB Benchmarking Suite | Quantitative evaluation of integration methods | Search-and-Select | Scores batch correction and biological conservation [34] |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automated materials synthesis and preparation | Guided | Enables high-throughput experimental iteration [20] |

| Automated Electrochemical Workstation | Materials performance testing | Guided | Provides quantitative performance data for feedback loops [20] |

| TCGA Data Portal | Source of curated multi-omics cancer data | Independent | Provides standardized datasets for method validation [33] [35] |

| scVI/scANVI Framework | Deep learning-based single-cell integration | Search-and-Select | Unifies variational autoencoders with multiple loss functions [34] |

| Computer Vision Systems | Experimental monitoring and anomaly detection | Guided | Identifies reproducibility issues in real-time [20] |

| 4-((1H-Pyrrol-1-yl)methyl)piperidine | 4-((1H-Pyrrol-1-yl)methyl)piperidine|CAS 614746-07-5 | 4-((1H-Pyrrol-1-yl)methyl)piperidine (CAS 614746-07-5) is a high-purity piperidine building block for pharmaceutical and chemical research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,2-Bis(4-nitrobenzyl)malonic acid | 2,2-Bis(4-nitrobenzyl)malonic acid, CAS:653306-99-1, MF:C17H14N2O8, MW:374.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis of integration strategies reveals a context-dependent performance landscape where no single approach universally outperforms others across all research domains. Independent integration methods demonstrate superior performance in biological discovery tasks where preserving data-type-specific signals is paramount and where comprehensive prior knowledge is limited. Guided integration excels in experimental sciences where iterative feedback between computation and physical synthesis can dramatically accelerate materials optimization and discovery. Search-and-select integration provides a robust framework for method selection in rapidly evolving fields where multiple viable approaches exist, and optimal strategy depends on specific dataset characteristics and research objectives.

The critical differentiator among these approaches lies in their relationship to experimental validation. Independent integration typically concludes with experimental verification of computational predictions, creating a linear discovery pipeline. Guided integration embeds experimentation within the analytical loop, creating a recursive refinement process that more closely mimics human scientific reasoning. Search-and-select integration optimizes the connection between computational method and experimental outcome through empirical testing of multiple approaches, acknowledging the imperfect theoretical understanding of which methods will perform best in novel research contexts. As integration methodologies continue to evolve, the most impactful research will likely emerge from teams that strategically match integration strategies to their specific validation paradigms and research goals, rather than relying on one-size-fits-all approaches to complex scientific data.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into pharmaceutical research has catalyzed a revolutionary shift, enabling the rapid prediction of critical drug properties such as binding affinity, efficacy, and toxicity [36]. These AI-powered predictive models are transforming the drug discovery pipeline from a traditionally lengthy, high-attrition process to a more efficient, data-driven enterprise. By comparing computational predictions with experimental data, researchers can now prioritize the most promising drug candidates with greater confidence, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new therapeutics to market [36] [37]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance, methodologies, and applications of contemporary AI models across key domains of drug discovery, offering a framework for scientists to evaluate these tools against experimental benchmarks.

The foundational paradigm leverages various AI approaches, from conventional machine learning to advanced deep learning, to analyze complex biological and chemical data [36] [37]. These models learn from large-scale datasets encompassing protein structures, compound libraries, and toxicity endpoints to predict how potential drug molecules will interact with biological systems. The following sections delve into specific applications, compare model performance with experimental validation, and detail the experimental protocols that underpin this technological advancement.

AI in Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction

Methodological Approaches and Comparative Performance

Protein-ligand binding affinity (PLA) prediction is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery, guiding hit identification and lead optimization by quantifying the strength of interaction between a potential drug molecule and its target protein [37]. The methodologies for predicting PLA have evolved from conventional physics-based calculations to machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models that offer improved accuracy and scalability [37] [38]. Conventional methods, often rooted in molecular dynamics or empirical scoring functions, provide a theoretical basis but can be rigid and limited to specific protein families [37]. Traditional ML models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests (RF), utilize human-engineered features from complex structures and have demonstrated competitive performance, particularly in scoring and ranking tasks [37] [39]. In recent years, however, deep learning has emerged as a dominant approach, capable of automatically learning relevant features from raw input data like sequences and 3D structures, thereby capturing more complex, non-linear relationships [38].

Advanced deep learning models are increasingly adopting multi-modal fusion strategies to integrate complementary information. For instance, the DeepLIP model employs an early fusion strategy, combining descriptor-based information of ligands and protein binding pockets with graph-based representations of their interactions [38]. This integration of multiple data modalities has been shown to enhance predictive performance by providing a more holistic view of the protein-ligand complex. The table below summarizes the performance of various AI approaches on the widely recognized PDBbind benchmark dataset, illustrating the progressive improvement in predictive accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models for Binding Affinity Prediction on the PDBbind Core Set

| Model / Approach | Type | PCC | MAE | RMSE | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLIP [38] | Deep Learning (Multi-modal) | 0.856 | 1.128 | 1.503 | Fuses ligand, pocket, and interaction graph descriptors. |

| SIGN [38] | Deep Learning (Structure-based) | 0.835 | 1.190 | 1.550 | Structure-aware interactive graph neural network. |

| FAST [38] | Deep Learning (Fusion) | 0.847 | 1.150 | 1.520 | Combines 3D CNN and spatial graph neural networks. |

| Random Forest [37] [39] | Traditional Machine Learning | ~0.800 | - | - | Relies on human-engineered features. |

| Support Vector Machine [37] [39] | Traditional Machine Learning | ~0.790 | - | - | Competitive with deep learning in some benchmarks. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Training and Validation

The development and validation of robust PLA prediction models follow a standardized protocol centered on curated datasets and specific evaluation metrics. The PDBbind database is the most commonly used benchmark, typically divided into a refined set for training and validation and a core set (e.g., CASF-2016) for external testing [37] [38]. This ensures models are evaluated on high-quality, non-overlapping data.

A standard experimental workflow involves:

- Dataset Preparation: The refined set of PDBbind (e.g., v2016 with ~3,772 samples) is used for training. A portion (e.g., 20%) is randomly held out as a validation set for hyperparameter optimization. The core set (285 samples) serves as the final external test benchmark [38].

- Input Representation:

- Proteins: The binding pocket is represented by its amino acid sequence or 3D atomic coordinates, from which descriptors (e.g., Composition, Transition, Distribution) or graph structures are computed [38].

- Ligands: The small molecule is represented by its SMILES string or 3D structure, which is then used to calculate chemical descriptors or molecular fingerprints [38].

- Interactions: The complex is often modeled as a spatial graph where nodes are protein and ligand atoms, and edges represent intermolecular forces or distances [38].

- Model Training: Deep learning models are implemented using frameworks like PyTorch and optimized with algorithms like Adam. The regression task typically uses loss functions like SmoothL1Loss to minimize the difference between predicted and experimental binding affinities (often expressed as pKd, pKi, or pIC50) [38].

- Evaluation: Model performance is rigorously assessed on the held-out test set using metrics that evaluate different aspects of predictive power:

Diagram 1: AI Binding Affinity Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the multi-modal data processing pipeline, from input representation to final evaluation, used in modern deep learning models like DeepLIP.

AI Models for Drug Toxicity Prediction

Predictive Models for Toxicity Endpoints

The prediction of drug toxicity is a critical application of AI, aimed at addressing the high attrition rates in drug development caused by safety failures [40]. AI models, particularly machine learning and deep learning, leverage large toxicity databases to predict a wide range of endpoints, including acute toxicity, carcinogenicity, and organ-specific toxicity (e.g., hepatotoxicity, cardiotoxicity) [40]. These models learn from the structural and physicochemical properties of compounds to identify patterns associated with adverse effects. The transition from traditional quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to more sophisticated AI-based approaches has led to significant improvements in prediction accuracy and applicability domains [40].

The performance of these models is heavily dependent on the quality and scope of the underlying data. Numerous public and proprietary databases provide the experimental data necessary for training. The table below outlines key toxicity databases and their applications in AI model development.

Table 2: Key Databases for AI-Powered Drug Toxicity Prediction

| Database | Data Content and Scale | Primary Application in AI Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| TOXRIC [40] | Comprehensive toxicity data (acute, chronic, carcinogenicity) across species. | Provides rich training data for various toxicity endpoint classifiers. |

| ChEMBL [40] | Manually curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and ADMET data. | Used for model training on bioactivity and toxicity profiles. |

| PubChem [40] | Massive database of chemical structures, bioassays, and toxicity information. | Serves as a key data source for feature extraction and model training. |

| DrugBank [40] | Detailed drug data including adverse reactions and drug interactions. | Useful for validating toxicity predictions against clinical data. |

| ICE [40] | Integrates chemical information and toxicity data (e.g., LD50, IC50) from multiple sources. | Supports the development of models for acute toxicity prediction. |

| FAERS [40] | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System with post-market surveillance data. | Enables models linking drug features to real-world clinical adverse events. |

Experimental Framework for Toxicity Model Validation

The validation of AI-based toxicity predictors requires a rigorous framework to ensure their reliability for regulatory and decision-making purposes. The experimental protocol often involves:

- Data Curation and Featurization: Data is sourced from multiple databases (see Table 2). Chemical structures (e.g., SMILES strings) are converted into numerical descriptors or fingerprints that encode structural and electronic properties [40].

- Model Building and Training: Various ML/DL algorithms are applied. Traditional models like SVM and RF are common, but deep neural networks are increasingly used for complex endpoint prediction. The dataset is typically split into training, validation, and test sets, often using a scaffold split to assess generalization to novel chemotypes [39] [40].

- Evaluation Metrics: For classification tasks (e.g., toxic vs. non-toxic), metrics such as the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUC-PR) are used. The AUC-PR is particularly informative for imbalanced datasets where non-toxic compounds may dominate [39] [40]. The move towards explainable AI (XAI) is also critical, using techniques like feature importance analysis to interpret model predictions and build trust [40] [41].

AI in Drug Efficacy and Phenotypic Screening

Beyond single-target binding, AI models are powerful tools for predicting broader drug efficacy and cellular phenotypic responses. This approach often utilizes high-content screening (HCS) data, such as cellular images, to predict a compound's functional effect on a biological system [42]. Companies like Recursion Pharmaceuticals generate massive, standardized biological datasets by treating cells with genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR knockouts) and small molecules, then imaging them with microscopy [42]. AI models, particularly deep learning-based computer vision algorithms, are trained to analyze these images and extract features that correlate with therapeutic efficacy or mechanism of action.

This phenotypic approach can bypass the need for a predefined molecular target, potentially identifying novel therapeutic pathways. The release of public datasets like RxRx3-core, which contains over 222,000 labeled cellular images, provides a benchmark for the community to develop and validate models for tasks like zero-shot drug-target interaction prediction directly from HCS data [42] [43]. The experimental protocol involves training convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or vision transformers on these image datasets to predict treatment outcomes or match the phenotypic signature of a new compound to known bio-active molecules.

Integrated Benchmarking and Performance Challenges

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance