Building a High-Performance Molecular Property Predictor: A Practical Guide to Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for researchers and drug development professionals on constructing a robust molecular property predictor by integrating Morgan fingerprints with the XGBoost algorithm.

Building a High-Performance Molecular Property Predictor: A Practical Guide to Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for researchers and drug development professionals on constructing a robust molecular property predictor by integrating Morgan fingerprints with the XGBoost algorithm. It covers the foundational theory behind these techniques, details their practical implementation, and addresses common challenges like data scarcity and hyperparameter tuning. The guide also presents a rigorous framework for model validation and benchmarking against alternative methods, empowering scientists to leverage this powerful, non-deep-learning approach for accelerated drug discovery and materials design.

Understanding the Core Components: Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

The Central Role of Molecular Representation

In the field of cheminformatics and drug discovery, molecular representation refers to the process of converting the complex structural information of a chemical compound into a numerical format that machine learning algorithms can process. The fundamental principle, known as the Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), posits that a molecule's structure determines its properties and biological activity [1]. The choice of representation directly influences a model's ability to capture these structure-property relationships, thereby determining the success of any predictive pipeline.

Molecular representations bridge the gap between chemical structures and machine learning models. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting an optimal representation is crucial for building accurate predictors for properties such as toxicity, solubility, binding affinity, and odor perception [2] [1]. This document, framed within a broader thesis on building molecular property predictors, details why molecular representation forms the foundational step and provides a detailed protocol for implementing a predictor using the powerful combination of Morgan Fingerprints and the XGBoost algorithm.

Key Molecular Representation Methods

Several molecular representation schemes have been developed, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below summarizes the most prominent types used in machine learning applications.

Table 1: Key Molecular Representation Methods for Machine Learning

| Representation Type | Description | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP) [2] [1] | Circular topological fingerprints that capture atomic neighborhoods and substructures up to a specified radius. | Captures local structural features invariant to atom numbering; highly effective for similarity search and QSAR. | Drug-target interaction, property prediction, virtual screening. |

| Molecular Descriptors [2] | 1D or 2D numerical values representing physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polar surface area). | Direct physical meaning; often easily interpretable. | Preliminary screening, models requiring direct physicochemical insight. |

| Functional Group (FG) Fingerprints [2] | Binary vectors indicating the presence or absence of predefined functional groups or substructures. | Simple and interpretable; directly links known chemical features to activity. | Toxicity prediction, metabolic stability. |

| Data-Driven (Deep Learning) Fingerprints [3] [1] | Continuous vector representations learned by deep learning models (e.g., Autoencoders, Transformers) from molecular data. | Can capture complex, non-obvious patterns without manual feature engineering; often high-dimensional. | State-of-the-art property prediction, de novo molecular design. |

| 3D Geometric Representations [4] | Encodes the three-dimensional spatial conformation of a molecule, including atomic coordinates and distances. | Captures stereochemistry and spatial interactions critical for binding affinity. | Protein-ligand docking, binding affinity prediction. |

Among these, Morgan Fingerprints remain one of the most widely used and effective representations, particularly when combined with powerful ensemble tree models like XGBoost [5] [2]. Their success lies in their ability to systematically and comprehensively encode the topological structure of a molecule into a fixed-length bit vector, providing a rich feature set for machine learning algorithms.

Morgan Fingerprints: A Closer Look

The Morgan algorithm, also known as the Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) generation algorithm, operates by iteratively characterizing the environment around each non-hydrogen atom in a molecule [1]. The process can be visualized as a series of circular layers expanding around each atom.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key parameter choices for generating a Morgan Fingerprint.

The process involves two critical parameters:

- Radius (N): This defines the diameter of the atomic environment considered. A radius of 1 includes the immediate neighbors of an atom, while a radius of 2 includes neighbors of neighbors, capturing larger substructures. Common choices are 2 or 3 [1].

- Fingerprint Length: The size of the final bit vector (e.g., 1024, 2048). A longer vector reduces the chance of hash collisions but increases computational load.

The XGBoost Advantage for Molecular Property Prediction

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is a highly optimized implementation of the gradient-boosted decision trees algorithm. Its popularity in machine learning competitions and industrial applications stems from its superior performance, speed, and robustness [6] [7].

In the context of molecular property prediction, the high-dimensional, sparse feature vectors produced by Morgan Fingerprints are an excellent match for XGBoost's strengths. The algorithm works by sequentially building decision trees, where each new tree is trained to correct the errors made by the previous ensemble of trees [7].

Key features that make XGBoost particularly effective for this domain include:

- Handling of Sarse Data: It efficiently handles the sparse binary vectors generated by fingerprinting algorithms [6].

- Regularization: Built-in L1 and L2 regularization helps to prevent overfitting, which is a common risk with high-dimensional fingerprint data [5] [7].

- Feature Importance: XGBoost provides built-in tools to calculate feature importance, offering insights into which molecular substructures may be driving the prediction, adding a layer of interpretability [7].

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Morgan Fingerprints with XGBoost

| Task / Dataset | Representation - Model | Performance Metric | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor Prediction | Morgan Fingerprint - XGBoost | AUROC | 0.828 | [2] |

| (Multi-label, 8,681 compounds) | Molecular Descriptors - XGBoost | AUROC | 0.802 | [2] |

| Functional Group - XGBoost | AUROC | 0.753 | [2] | |

| Critical Temperature Prediction | Mol2Vec Embedding - XGBoost | R² | 0.93 | [8] |

| (CRC Handbook Dataset) | VICGAE Embedding - XGBoost | R² | Comparable | [8] |

| Embedded Morgan (eMFP) | eMFP (q=16/32/64) - Multiple Models | Regression Performance | Outperformed standard MFP | [5] |

| (RedDB, NFA, QM9 Databases) |

As evidenced in the table above, the combination of Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost consistently delivers high performance across diverse molecular property prediction tasks, from complex sensory attributes like odor to fundamental physical properties.

Experimental Protocol: Building a MorganFP-XGBoost Predictor

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for building a molecular property predictor using Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Essential Tools and Libraries for Implementation

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used for reading molecules, generating Morgan fingerprints, and calculating molecular descriptors. Essential for the protocol [2] [8] [1]. |

| XGBoost Library | Python/R/Julia library implementing the XGBoost algorithm. | Provides the XGBRegressor and XGBClassifier for model building. Optimized for performance [6] [7]. |

| Scikit-learn | Machine learning library in Python. | Used for data splitting, preprocessing, cross-validation, and performance metric calculation. |

| Python/Pandas/NumPy | Programming language and data manipulation libraries. | The core environment for scripting the data pipeline and analysis. |

| Molecular Dataset | Curated set of molecules with associated property data. | Public sources: DrugBank, ChEMBL, PubChem, CRC Handbook [8]. Requires SMILES strings and target property values. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

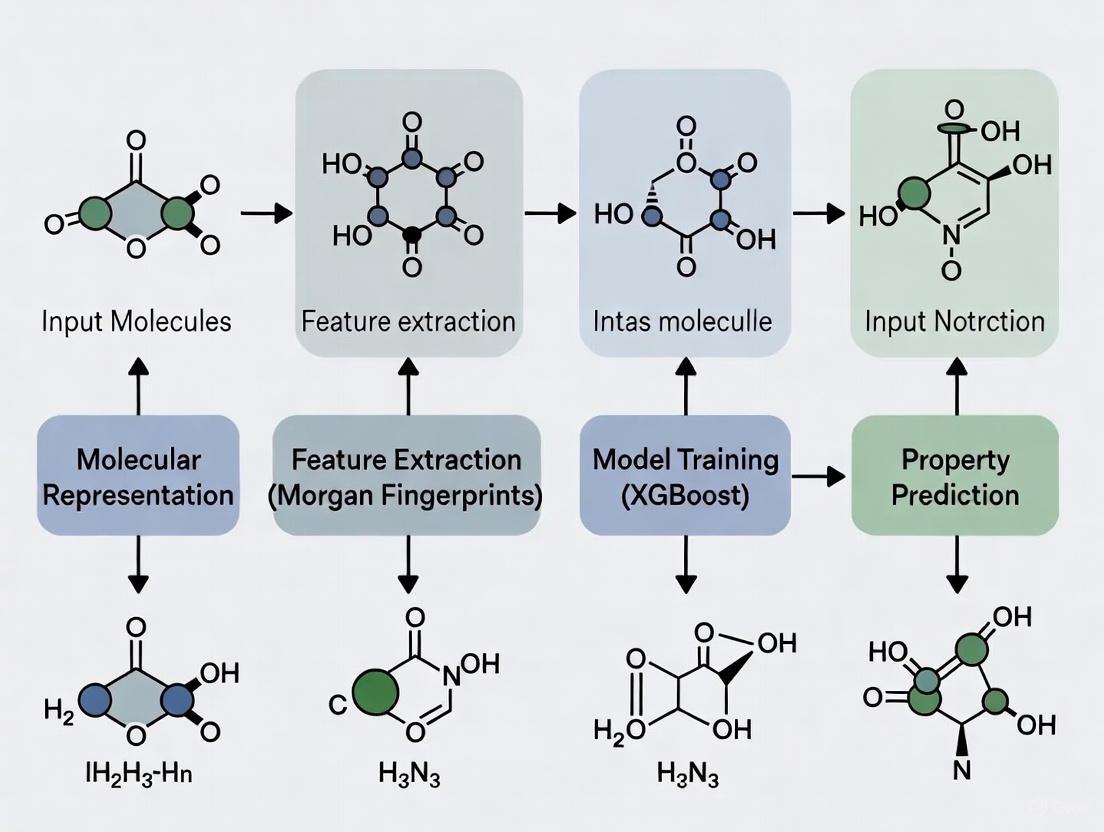

The following diagram outlines the complete machine learning pipeline, from raw data to a trained and validated predictive model.

Protocol Steps:

Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Input: A dataset containing canonical SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings and the corresponding target property values (e.g., boiling point, toxicity label) [8].

- Action: Standardize the molecules using RDKit. This includes sanitizing the molecular graph, removing salts, and generating canonical SMILES. Handle missing values and outliers in the target property.

Generate Morgan Fingerprints

- Action: Use the RDKit's

GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVectfunction to convert each SMILES string into a fixed-length binary bit vector. - Critical Parameters:

radius: Typically set to 2 or 3. This controls the level of structural detail captured.nBits: The length of the fingerprint vector. A value of 1024 or 2048 is commonly used to balance specificity and computational cost [3].

- Action: Use the RDKit's

Split Data

- Action: Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets. A scaffold split, which separates molecules based on their core Bemis-Murcko scaffolds, is recommended to rigorously test the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes [4]. A typical ratio is 80/10/10.

Hyperparameter Tuning

- Action: Use the training set to train XGBoost models and the validation set to guide hyperparameter optimization. Employ frameworks like Optuna or GridSearchCV for an efficient search [8].

- Key XGBoost Hyperparameters:

max_depth: Maximum depth of a tree (e.g., 3-10). Controls model complexity.learning_rate(eta): Shrinks the contribution of each tree (e.g., 0.01-0.3).n_estimators: Number of boosting rounds. Useearly_stopping_roundsto prevent overfitting.subsample: Fraction of samples used for training each tree.colsample_bytree: Fraction of features (fingerprint bits) used per tree.

Train Final Model

- Action: Using the best-found hyperparameters, train the final XGBoost model on the combined training and validation data.

Evaluate Model

- Action: Make predictions on the held-out test set, which was not used during training or tuning. Report standard performance metrics:

- Regression (e.g., for boiling point): R², Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE).

- Classification (e.g., for toxicity): AUC-ROC, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score.

- Action: Make predictions on the held-out test set, which was not used during training or tuning. Report standard performance metrics:

Analyze Feature Importance

- Action: Use XGBoost's built-in

feature_importance_attribute (e.g.,gaintype) to identify the fingerprint bits (and by extension, the molecular substructures) that were most influential in the model's predictions. This can provide valuable chemical insights.

- Action: Use XGBoost's built-in

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

As the field advances, several techniques are being developed to enhance the basic Morgan-XGBoost pipeline:

- Embedded Morgan Fingerprints (eMFP): This method applies dimensionality reduction to standard Morgan fingerprints, creating a lower-dimensional, continuous representation. eMFP has been shown to mitigate overfitting and can outperform standard MFP, especially with regression models [5].

- Deep Learning Representations: Methods like FP-BERT treat fingerprint substructures as words in a sentence and use transformer-based models to learn contextualized molecular representations in a self-supervised manner before fine-tuning on specific tasks [1]. Other advanced models like SCAGE incorporate 3D conformational information and functional group knowledge through multi-task pre-training, leading to improved generalization and interpretability on challenging structure-activity cliffs [4].

In conclusion, molecular representation is the indispensable first step in any computational prediction of molecular properties. The robust and interpretable combination of Morgan Fingerprints for feature extraction and XGBoost for model building provides a powerful, reliable, and accessible pipeline for researchers. This protocol offers a solid foundation, while emerging techniques in dimensionality reduction and deep learning promise to further push the boundaries of predictive accuracy and chemical insight.

Molecular fingerprints are essential cheminformatics tools that encode the structural features of a molecule into a fixed-length vector, enabling quantitative similarity comparisons and machine learning applications in drug discovery [9] [10]. Among the various types of fingerprints, the Morgan fingerprint, also known as the Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP), stands out for its effectiveness in capturing circular atom neighborhoods within molecular structures [11]. These fingerprints operate on the fundamental principle that molecules with similar substructures often exhibit similar biological activities or physicochemical properties, making them invaluable for quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and virtual screening [9].

The Morgan algorithm, originally developed to tackle graph isomorphism problems, provides the theoretical foundation for these fingerprints [12] [11]. Unlike predefined structural keys (e.g., MACCS keys) that test for the presence of specific expert-defined substructures, Morgan fingerprints are molecule-directed and generated systematically from the molecular graph itself without requiring a predefined fragment library [11] [10]. This allows them to capture a vast and relevant set of chemical features directly from the data, which is particularly advantageous for predicting complex molecular properties when combined with powerful machine learning algorithms like XGBoost [2] [12].

Theoretical Foundation and Generation Algorithm

Core Conceptual Framework

The Morgan fingerprint generation process employs a circular topology approach that systematically captures information about the neighborhood around each non-hydrogen atom in a molecule [11]. The algorithm is rooted in the concept of circular atom environments, which represent the substructures within a progressively increasing radius around each atom. This approach allows the fingerprint to encode molecular features at multiple levels of granularity, from individual atomic properties to larger functional groupings [13] [11].

A key advantage of this circular approach is its alignment invariance - unlike 3D structural representations that require molecular alignment for comparison, Morgan fingerprints derive directly from the 2D molecular graph, enabling rapid similarity calculations without spatial orientation concerns [13]. Additionally, the representation is deterministic, meaning the same molecule will always generate the same fingerprint, ensuring reproducibility in chemical informatics workflows [11].

Step-by-Step Generation Process

The Morgan fingerprint generation follows a systematic iterative process:

Initial Atom Identifier Assignment: The algorithm begins by assigning an initial integer identifier to each non-hydrogen atom in the molecule. This identifier encapsulates key local atom properties, typically including: atomic number, number of heavy (non-hydrogen) neighbors, number of attached hydrogens (both implicit and explicit), formal charge, and whether the atom is part of a ring [11]. These properties are hashed into a single integer value using a hash function.

Iterative Identifier Updating: The algorithm then performs a series of iterations to capture progressively larger circular neighborhoods around each atom. At each iteration, the current identifier for an atom is updated by combining it with the identifiers of its directly connected neighbors. This combined information is then hashed to produce a new integer identifier representing a larger substructure [11] [14]. The number of iterations determines the maximum diameter of the captured circular neighborhoods.

Feature Collection and Duplicate Removal: All unique integer identifiers generated throughout the iterations (including the initial ones) are collected into a set. Each identifier represents a distinct circular substructure present in the molecule. By default, duplicate occurrences of the same substructure are recorded only once, though the algorithm can be configured to keep count frequencies (resulting in ECFC - Extended Connectivity Fingerprint Count) [11].

Fingerprint Folding (Optional): The final set of integer identifiers can be used directly as a variable-length fingerprint. However, for easier storage and comparison, it is commonly "folded" into a fixed-length bit vector (e.g., 1024 or 2048 bits) using a modulo operation [13] [11]. This step makes the fingerprint more compact but may introduce bit collisions, where different substructures map to the same bit position.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Morgan Fingerprint Generation

| Parameter | Description | Typical Values | Impact on Fingerprint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | Maximum diameter of circular neighborhoods | 2, 4, 6 | Larger values capture larger substructures, increasing specificity |

| Length | Size of folded bit vector | 512, 1024, 2048 | Longer vectors reduce bit collisions and information loss |

| Atom Features | Properties encoded in initial identifier | Atomic number, connectivity, charge, etc. | Determines the chemical features represented |

| Counts | Whether to record feature frequencies | Yes/No | Count fingerprints may capture additional information |

Figure 1: Morgan Fingerprint Generation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the systematic process of generating Morgan fingerprints from 2D molecular structures through iterative neighborhood expansion.

Integration with Machine Learning (XGBoost) for Property Prediction

Synergy Between Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

The combination of Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) has emerged as a powerful framework for molecular property prediction in modern cheminformatics [2] [12]. This synergy leverages the complementary strengths of both technologies: Morgan fingerprints effectively capture relevant chemical structures in a numerically encoded format, while XGBoost efficiently learns complex, non-linear patterns from these high-dimensional, sparse encodings [2]. The gradient-boosting approach of XGBoast is particularly well-suited to handle the sparse, binary nature of fingerprint vectors, with built-in regularization that helps prevent overfitting even when using high-dimensional feature spaces [2] [12].

Recent benchmark studies have demonstrated the exceptional performance of this combination across diverse prediction tasks. In odor perception prediction, a Morgan-fingerprint-based XGBoost model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.828 and an area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) of 0.237, outperforming both descriptor-based models and other machine learning algorithms [2]. Similarly, in ADME-Tox (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) prediction, this combination delivered competitive performance across multiple endpoints including Ames mutagenicity, P-glycoprotein inhibition, and hERG inhibition [12].

Protocol: Building a Molecular Property Predictor

Protocol 1: Molecular Property Prediction Using Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

Purpose: To construct a robust machine learning model for predicting molecular properties using Morgan fingerprints as features and XGBoost as the learning algorithm.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Chemical Dataset: Curated set of molecules with associated property/activity data (e.g., from ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Cheminformatics Library: RDKit (for fingerprint generation and molecular processing)

- Machine Learning Library: XGBoost package

- Computational Environment: Python with standard data science libraries (pandas, numpy, scikit-learn)

Procedure:

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Obtain molecular structures in SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) format with associated target property values.

- Apply standard chemical curation: remove duplicates, strip salts, and filter by element composition (typically C, H, N, O, S, P, F, Cl, Br, I) [12].

- For unbalanced datasets, consider applying techniques such as oversampling or undersampling to balance class distributions [12].

Feature Generation (Fingerprinting):

- Generate Morgan fingerprints for each molecule using RDKit's

GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVectfunction. - Use a diameter of 4 (equivalent to radius 2) and a fingerprint length of 1024 bits as starting parameters [11].

- Consider testing alternative parameters (diameter of 2 or 6, lengths of 512 or 2048) to optimize for specific applications.

- Convert the fingerprints into a feature matrix where each row represents a molecule and each column represents a bit position.

- Generate Morgan fingerprints for each molecule using RDKit's

Model Training and Validation:

- Split the dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) sets, maintaining class distribution through stratified sampling [2].

- Implement 5-fold cross-validation on the training set for robust hyperparameter tuning and model selection.

- Configure XGBoost with appropriate parameters for the task (binary classification, multiclass, or regression).

- Train the XGBoost model on the fingerprint feature matrix, using the target property as the response variable.

Model Evaluation and Interpretation:

- Evaluate model performance on the held-out test set using task-appropriate metrics: AUROC and AUPRC for classification; RMSE and R² for regression.

- Analyze feature importance scores provided by XGBoost to identify which structural features most strongly influence predictions.

- Validate model applicability domain by assessing performance consistency across diverse chemical scaffolds.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If model performance is poor, consider increasing fingerprint diameter to capture larger substructures or adjusting XGBoost hyperparameters (learning rate, maximum depth, number of estimators).

- For datasets with strong class imbalance, adjust XGBoost's

scale_pos_weightparameter or employ specialized sampling techniques. - If overfitting occurs, increase regularization parameters (lambda, alpha) or reduce model complexity.

Performance Benchmarking and Applications

Quantitative Performance Across Domains

Morgan fingerprints have demonstrated competitive performance across diverse chemical informatics applications. The following table summarizes benchmark results from recent studies:

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Morgan Fingerprints in Various Applications

| Application Domain | Dataset | Performance Metrics | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odor Perception | 8,681 compounds from 10 expert sources [2] | AUROC: 0.828, AUPRC: 0.237 [2] | Superior to functional group and molecular descriptor approaches [2] |

| ADME-Tox Prediction | 6 binary classification targets (1,000-6,500 molecules each) [12] | Competitive across multiple endpoints [12] | Comparable or superior to other fingerprint types (MACCS, Atompairs) [12] |

| Drug Target Prediction | ChEMBL20 database [13] | Higher precision-recall than 3D fingerprints (E3FP) in some cases [13] | Complementary to 3D structural information [13] |

| Virtual Screening | Multiple benchmark studies [11] | Among best performing for similarity searching [11] | Typically outperforms path-based fingerprints for similarity searching [11] |

Application Notes in Drug Discovery

Application Note 1: Scaffold Hopping and Bioactivity Prediction

Morgan fingerprints excel in identifying structurally diverse compounds with similar bioactivity - a process known as scaffold hopping. Their circular substructure representation captures pharmacophoric features essential for binding without being constrained by molecular backbone identity [11]. When implementing scaffold hopping:

- Use a shorter fingerprint diameter (2-4) to focus on key pharmacophoric elements rather than complete scaffold structures

- Combine similarity searching with machine learning by training XGBoost models on known actives and inactives

- Apply similarity thresholds (Tanimoto coefficient > 0.4-0.6) to identify promising candidates from virtual screens [11]

Application Note 2: ADME-Tox Optimization in Lead Series

In lead optimization, Morgan fingerprints facilitate the prediction of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME-Tox) properties [12] [11]. Implementation guidelines include:

- Train separate XGBoost models for specific ADME-Tox endpoints (e.g., hERG inhibition, CYP450 interactions)

- Use larger fingerprint diameters (4-6) to capture complex structural features influencing metabolic stability

- Interpret feature importance to guide structural modifications that improve safety profiles while maintaining potency

- Integrate multiple property predictions into multi-parameter optimization workflows [12]

Figure 2: Integrated Workflow for Molecular Property Prediction - This diagram outlines the complete pipeline from molecular structure input to property prediction, highlighting key application domains where Morgan fingerprints combined with XGBoost deliver strong performance.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Implementing Morgan Fingerprint-Based Predictions

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Key Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit [12] [14] | Open-source toolkit for fingerprint generation and molecular processing | Provides GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVect function with configurable parameters |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | XGBoost [2] [12] | Gradient boosting library for building predictive models | Handles sparse fingerprint data efficiently with built-in regularization |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [13] [3], PubChem [2] | Sources of curated molecular structures with bioactivity data | Provide standardized datasets for model training and validation |

| Specialized Fingerprints | E3FP (3D fingerprints) [13] | 3D structural fingerprints for specific applications | Complementary to Morgan fingerprints for certain target classes |

| Similarity Metrics | Tanimoto coefficient [9] | Measure fingerprint similarity for virtual screening | Default similarity metric for binary fingerprint comparisons |

| Model Validation | Scikit-learn [2] | Machine learning utilities for model evaluation | Provides cross-validation and performance metric implementations |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

Despite their widespread success, Morgan fingerprints have limitations that researchers should consider in advanced applications. Their 2D topological nature means they cannot directly capture molecular shape, conformation, or stereochemical features that may critically influence biological activity [13]. For targets where 3D structure is crucial, consider complementary approaches such as:

- E3FP (Extended Three-Dimensional FingerPrint): A 3D extension of Morgan fingerprints that captures stereochemistry and spatial relationships [13]

- Structural Interaction Fingerprints: Encode protein-ligand interaction patterns from 3D complex structures [9]

- Hybrid representations: Combine Morgan fingerprints with molecular descriptors or 3D information for enhanced predictive capability [15]

Additionally, the dependence on hashing functions means that different implementations may produce varying results, and the folding process can introduce bit collisions that reduce discriminative power [11]. For large-scale applications, consider using unfolded fingerprints or increased vector lengths (2048+ bits) to minimize collisions.

Emerging Trends and Methodological Advances

The field of molecular representation continues to evolve with several promising directions:

- Hybrid fingerprint-graph models: Recent approaches like Fingerprint-Enhanced Hierarchical Molecular Graph Neural Networks (FH-GNN) integrate Morgan fingerprints with graph neural networks to capture both local functional groups and global molecular topology [15]

- Multi-task learning: Training single models on multiple related endpoints using Morgan fingerprints as common input features [3]

- Universal fingerprints: Development of representations like MAP4 (MinHashed Atom-Pair fingerprint) that aim to perform well across diverse molecule types, from small drugs to biomacromolecules [16]

- Interpretability advances: Improved methods for mapping important fingerprint bits back to chemically meaningful substructures, enhancing model trustworthiness in decision-critical applications [9] [15]

As these advances mature, Morgan fingerprints remain a fundamental tool in the cheminformatics toolbox, providing a robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient foundation for molecular machine learning that continues to deliver state-of-the-art performance across diverse applications in drug discovery and chemical informatics.

In the field of computational chemistry and drug discovery, accurately predicting molecular properties from chemical structure is a fundamental challenge. The combination of Morgan fingerprints for molecular representation and the XGBoost algorithm for model building has emerged as a particularly powerful and popular approach. This synergy provides researchers with a robust framework for building predictive models that can accelerate virtual screening and compound optimization [2].

Morgan fingerprints, also known as circular fingerprints, capture molecular structure by encoding the presence of specific substructures and atomic environments within a molecule. When paired with XGBoost, an advanced gradient boosting implementation known for its computational efficiency and predictive performance, they form a potent combination for tackling quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) and quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) tasks [2] [5].

This protocol outlines the application of these tools for building molecular property predictors, providing a structured guide from data preparation to model deployment, supported by recent benchmarking studies demonstrating their effectiveness.

Key Evidence: Performance Benchmarks

Recent comparative studies have quantitatively demonstrated the superiority of XGBoost models utilizing Morgan fingerprints across various molecular prediction tasks.

Table 1: Performance comparison of feature representation and algorithm combinations for odor prediction [2]

| Feature Set | Algorithm | AUROC | AUPRC | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | XGBoost | 0.828 | 0.237 | 97.8 | 41.9 | 16.3 |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | LightGBM | 0.810 | 0.228 | - | - | - |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | Random Forest | 0.784 | 0.216 | - | - | - |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | XGBoost | 0.802 | 0.200 | - | - | - |

| Functional Group (FG) | XGBoost | 0.753 | 0.088 | - | - | - |

This comprehensive study analyzed 8,681 compounds with 200 odor descriptors, revealing that the Morgan-fingerprint-based XGBoost model achieved the highest discrimination performance, consistently outperforming both descriptor-based models and other algorithmic approaches [2].

Table 2: Performance of XGBoost across different domains

| Application Domain | Dataset/Setting | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Nodule Malignancy Prediction | Clinical & ultrasound features (n=2,014) | AUC: 0.928, Accuracy: 85.1%, Sensitivity: 93.3% | [17] |

| Physical Fitness Classification | 20,452 student records | Accuracy, Recall, F1: 3.5-7.9% improvement over baselines | [18] |

| STAT3 Inhibitor Prediction | FPG model with fingerprint integration | Average AUC: 0.897 on test set | [19] |

Technical Synergy: Why XGBoost and Morgan Fingerprints Work Well Together

Complementary Strengths

The effectiveness of this combination stems from how well the strengths of Morgan fingerprints align with the capabilities of the XGBoost algorithm:

High-Dimensional Sparse Data Handling: Morgan fingerprints typically generate high-dimensional binary vectors (often 1,024 to 2,048 dimensions) where most bits are zero. XGBoost efficiently handles such sparse data structures through its built-in sparsity-aware split finding algorithm [2] [20].

Non-Linear Relationship Capture: Molecular properties often depend on complex, non-linear interactions between structural features. XGBoost's sequential tree building with gradient optimization excels at detecting these patterns, outperforming linear models and single decision trees [2].

Robustness and Regularization: The molecular space is diverse, with potential for overfitting. XGBoost incorporates L1 and L2 regularization directly into its objective function, preventing overfitting on the high-dimensional fingerprint data [2] [18].

Computational Efficiency: For medium-sized molecular datasets (typically thousands to tens of thousands of compounds), XGBoost provides faster training times compared to deep learning approaches while maintaining competitive performance [20].

Recent Methodological Advances

Recent research has further optimized this partnership:

Embedded Morgan Fingerprints (eMFP): A novel dimensionality reduction technique that compresses standard Morgan fingerprints while preserving key structural information. This approach has demonstrated improved performance in regression models across multiple databases including RedDB, NFA, and QM9 [5].

Hybrid Architectures: New frameworks like MaxQsaring automate the selection of optimal feature combinations, including molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and deep-learning pretrained representations, with XGBoost frequently emerging as the top performer for prediction tasks [21].

Integration with Graph Neural Networks: Fingerprint-enhanced graph neural networks (e.g., FPG models) concatenate learned graph representations with traditional fingerprint vectors, with XGBoost often serving as the final prediction layer in such architectures [19].

Application Notes & Protocols: Building a Molecular Property Predictor

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for building a molecular property predictor using Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost:

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Morgan Fingerprint Generation

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 3: Essential software tools and libraries

| Tool/Library | Purpose | Installation Command |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Chemical informatics and fingerprint generation | conda install -c conda-forge rdkit |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting model implementation | pip install xgboost |

| Pandas & NumPy | Data manipulation and numerical operations | pip install pandas numpy |

| Scikit-learn | Data splitting, preprocessing, and evaluation metrics | pip install scikit-learn |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Collection and Standardization

- Obtain molecular structures in SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) format from databases such as PubChem, ChEMBL, or in-house collections.

- Standardize SMILES representation using RDKit's

Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles(smile))to ensure consistency. - Curate associated molecular property data (e.g., activity labels, solubility values, toxicity measurements).

Morgan Fingerprint Generation

- Use RDKit to compute Morgan fingerprints with a radius of 2 (equivalent to ECFP4) and 1024-bit length:

- For larger datasets (>10,000 compounds), consider using embedded Morgan fingerprints (eMFP) with compression sizes of q=16, 32, or 64 to reduce dimensionality while preserving structural information [5].

Data Splitting

- Implement scaffold splitting using RDKit's

ScaffoldSplitterto ensure training and test sets contain distinct molecular scaffolds, providing a more realistic assessment of generalization ability. - Standard alternative: Use random 80/20 split for training/test sets with stratification for classification tasks to maintain class distribution.

- Implement scaffold splitting using RDKit's

Protocol 2: XGBoost Model Development and Optimization

Materials and Software Requirements

- Python 3.7+ environment with xgboost package (v1.7+)

- Hyperparameter optimization library (Optuna, Scikit-optimize, or GridSearchCV)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Base Model Configuration

- Initialize XGBoost with parameters suitable for molecular data:

Hyperparameter Optimization

- Employ differential evolution (DE) for global parameter optimization, which has shown superior performance for XGBoost tuning on high-dimensional data [18].

- Key hyperparameters to optimize:

max_depth(3-10): Tree complexity balancelearning_rate(0.01-0.3): Step size shrinkagesubsample(0.6-1.0): Data sampling ratioreg_alphaandreg_lambda(0-1): Regularization strengthsn_estimators(50-500): Number of boosting rounds

Model Training with Cross-Validation

- Implement stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5 or 10) to robustly estimate performance.

- Use early stopping to prevent overfitting:

eval_set=[(X_test, y_test)],early_stopping_rounds=50.

Protocol 3: Model Evaluation and Interpretation

Materials and Software Requirements

- Model evaluation metrics (AUROC, AUPRC, accuracy, precision, recall)

- SHAP library for model interpretation

- Matplotlib/Seaborn for visualization

Step-by-Step Procedure

Performance Assessment

- Calculate standard metrics: Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), accuracy, precision, and recall.

- Generate calibration curves to assess prediction reliability.

- Perform decision curve analysis to evaluate clinical utility where applicable [17].

Model Interpretation

- Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify which molecular substructures (fingerprint bits) most strongly influence predictions.

- Analyze feature importance scores generated by XGBoost's built-in method.

- Visualize key molecular fragments associated with activity using RDKit's chemical visualization capabilities.

Model Deployment

- Serialize the trained model using

pickleorjoblibfor production use. - For web applications, deploy using frameworks like Flask or FastAPI, or create R Shiny applications for non-programming users [17].

- Serialize the trained model using

Table 4: Key resources for building molecular predictors with Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost

| Resource | Type | Purpose/Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Chemical informatics and fingerprint generation | Open-source (BSD license) |

| PyRfume | Data Resource | Curated olfactory dataset with 8,681 compounds | GitHub: pyrfume/pyrfume-data [2] |

| PubChem PUG-REST | API | SMILES retrieval and molecular data access | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [2] |

| XGBoost | Software Library | Gradient boosting model implementation | Open-source (Apache License 2.0) |

| Therapeutics Data Commons (TDC) | Benchmark Platform | Standardized datasets for fair model comparison | https://tdc.ai/ [21] |

| SHAP Library | Interpretation Tool | Model explanation and feature importance | Open-source (MIT License) |

Technical Considerations and Advanced Applications

Addressing Limitations

While powerful, the Morgan fingerprint + XGBoost approach has limitations:

Activity Cliffs: Subtle structural changes causing dramatic property changes may be better captured by 3D molecular representations or graph neural networks incorporating spatial information [4].

Novel Scaffolds: Performance may decrease for entirely novel molecular scaffolds not represented in training data. Consider transfer learning or multitask learning approaches.

High-Dimensionality Challenges: For extremely high-dimensional fingerprints, consider embedded Morgan fingerprints (eMFP) which offer compressed representations while maintaining performance [5].

Emerging Hybrid Approaches

Recent research demonstrates promising directions combining the strengths of this approach with advanced deep learning:

Fingerprint-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: Architectures that simultaneously process graph representations and traditional fingerprints, with XGBoost sometimes used as the final predictor [15] [19].

Multimodal Representations: Integrating Morgan fingerprints with additional molecular representations (descriptors, pretrained deep learning representations) in frameworks like MaxQsaring, which automatically select optimal feature combinations [21].

Self-Conformation-Aware Models: Approaches like SCAGE that incorporate 3D conformational information while maintaining interpretability through attention mechanisms [4].

The combination of Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost represents a robust, interpretable, and high-performing approach for molecular property prediction that continues to deliver state-of-the-art results across diverse applications. While newer deep learning methods offer promise for specific challenges, the simplicity, computational efficiency, and proven performance of this established methodology make it an essential tool in computational chemistry and drug discovery. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this powerful approach in their molecular prediction workflows.

Accurate molecular property prediction is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to identify promising compounds while reducing the costs and risks associated with experimental trials [22]. In this context, the selection of an optimal molecular representation and machine learning algorithm is paramount. This application note synthesizes recent evidence demonstrating that the combination of Morgan Fingerprints (MFP) as molecular descriptors with the XGBoost algorithm constitutes a particularly powerful and efficient approach for building predictive models in cheminformatics. While novel deep learning methods have garnered significant attention, systematic evaluations reveal that traditional machine learning methods, when paired with high-quality engineered features like Morgan Fingerprints, often deliver superior or highly competitive performance with greater computational efficiency [23] [22]. We present quantitative benchmarks, detailed protocols, and practical resources to empower researchers to implement this robust methodology in their molecular property prediction workflows.

Performance Evidence and Comparative Analysis

Recent comprehensive studies provide strong empirical support for the Morgan Fingerprint and XGBoost combination across diverse molecular property prediction tasks.

Systematic Benchmarking on Molecular Datasets

A large-scale systematic study evaluated numerous representation learning models and fixed representations across MoleculeNet datasets and opioids-related datasets. After training over 62,000 models, the study concluded that representation learning models exhibit limited performance in most molecular property prediction datasets and highlighted that dataset size is crucial for model success [23]. This finding underscores the advantage of using robust traditional methods like XGBoost with Morgan Fingerprints, especially in lower-data regimes common in early-stage drug discovery.

Table 1: Performance of Fingerprint-Based Methods in Recent Studies

| Study | Dataset(s) | Key Finding | Implication for MFP+XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| He et al. (2025) [24] | ChEMBL 34 (FDA-approved drugs) | MolTarPred using Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores was the most effective target prediction method. | Validates Morgan fingerprints as a superior choice for ligand-centric prediction tasks. |

| Embedded MFP (2025) [5] | RedDB, NFA, QM9 | Embedded Morgan Fingerprints (eMFP) outperformed standard MFP in multiple regression models, including Gradient Booster Regressor. | Suggests potential for dimensionality-reduced MFP to further enhance tree-based models. |

| Deng et al. (2023) [23] | MoleculeNet, Opioids datasets | Representation learning models showed limited performance; fixed representations like fingerprints remain highly competitive. | Affirms that advanced feature engineering (e.g., MFP) with classical ML is a robust strategy. |

| FH-GNN (2025) [22] | 8 MoleculeNet datasets | Integrating fingerprints with graph models (FH-GNN) boosted performance, showing fingerprints provide complementary information. | Highlights the strong predictive priors encoded in fingerprints, which XGBoost can effectively leverage. |

Enhanced Morgan Fingerprints for Improved Performance

A novel approach termed Embedded Morgan Fingerprints (eMFP) has been developed to address challenges of high-dimensionality in standard MFP. eMFP applies dimensionality reduction to the Morgan Fingerprint while preserving key structural information, resulting in an improved data representation that mitigates overfitting and enhances model performance [5]. This method demonstrated superior performance over standard MFP across several regression models, including Random Forest and Gradient Booster Regressor, on three different databases (RedDB, NFA, and QM9), with optimal compression sizes of 16, 32, and 64 [5]. The success of eMFP with gradient-boosted models directly reinforces the potential of the MFP-XGBoost combination.

Critical Role in State-of-the-Art Prediction Methods

In a precise 2025 comparison of seven molecular target prediction methods, MolTarPred emerged as the most effective method. A key finding was that its performance was optimized when using Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores, which outperformed the alternative MACCS fingerprints with Dice scores [24]. This result provides direct, recent evidence for the superiority of Morgan fingerprints in a critical, practical application—target prediction for drug repurposing.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Baseline MFP-XGBoost Predictor

This protocol details the steps to construct a molecular property predictor using standard Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost.

Workflow Diagram: Baseline MFP-XGBoost Predictor

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Input Data Preparation: Begin with a dataset of molecules represented as canonical SMILES strings and their associated property values (e.g., IC50, solubility) [24].

- Fingerprint Generation: Using a cheminformatics toolkit like RDKit, generate the Morgan Fingerprint (also known as ECFP, Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint) for each molecule. Standard parameters are a radius of 2 (equivalent to ECFP4) and a bit vector length of 2048 [23] [24].

- Code Snippet (RDKit):

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20 split). For robust performance estimation, implement a k-fold cross-validation strategy (e.g., 5-fold).

- Model Instantiation: Instantiate an XGBoost regressor or classifier, depending on the nature of the prediction task (continuous or categorical).

- Code Snippet (XGBoost):

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Perform a grid or random search to optimize key hyperparameters. Critical parameters for XGBoost include:

n_estimators: Number of boosting rounds (e.g., 100-1000).max_depth: Maximum tree depth (e.g., 3-10).learning_rate: Shrinks the feature weights to prevent overfitting (e.g., 0.01-0.3).subsample: Fraction of samples used for fitting trees (e.g., 0.8-1.0).

- Model Training: Train the tuned XGBoost model on the entire training set.

- Prediction and Evaluation: Use the trained model to make predictions on the held-out test set. Evaluate performance using relevant metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression, and ROC-AUC for classification [23].

Protocol 2: Advanced Protocol with Embedded MFP

This protocol leverages the enhanced version of Morgan Fingerprints for potentially superior performance, especially with large datasets.

Workflow Diagram: Advanced Protocol with eMFP

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Generate Standard MFP: As in Protocol 1, generate the high-dimensional standard Morgan Fingerprint.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply a dimensionality reduction technique to create the Embedded Morgan Fingerprint (eMFP). This can be achieved via autoencoders or other compression algorithms. The goal is to reduce the bit vector (e.g., from 2048 bits) to a smaller, dense vector representation (e.g., 16, 32, or 64 dimensions), which preserves the essential structural information while mitigating the curse of dimensionality [5].

- Model Training with eMFP: Use the resulting eMFP vectors as features for the XGBoost model. Follow the same steps for data splitting, hyperparameter tuning, and training as outlined in Protocol 1.

- Performance Comparison: Benchmark the performance of the eMFP-XGBoost model against the baseline MFP-XGBoost model to validate the improvement in predictive accuracy and training efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Data Resources for MFP-XGBoost Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Workflow | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Generates canonical SMILES from structural files and computes Morgan Fingerprints. | [23] [22] |

| XGBoost Library | Machine Learning Library | Provides the scalable and efficient implementation of the Gradient Boosting algorithm. | [22] |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Provides a large, curated source of bioactive molecules, targets, and properties for model training and validation. | [23] [24] |

| MoleculeNet | Benchmark Suite | Offers a standardized collection of molecular property prediction datasets for fair model comparison. | [23] [22] |

| Morgan/ECFP Fingerprint | Molecular Representation | Encodes molecular structure into a fixed-length bit vector that captures circular substructures. | [23] [5] [24] |

The accumulated evidence from recent, rigorous comparisons makes a compelling case for the combination of Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost as a robust and often superior framework for molecular property prediction. This approach consistently delivers high performance, challenging the assumption that more complex deep learning models are invariably better [23]. The robustness of Morgan Fingerprints is further validated by their role in enhancing state-of-the-art graph neural networks [22] and their critical contribution to the top-performing target prediction method, MolTarPred [24].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this combination offers a pragmatic and powerful path forward. It balances predictive accuracy with computational efficiency and model interpretability. The protocols provided herein offer a clear roadmap for implementation, from a baseline model to an advanced variant using embedded MFP. By leveraging this winning combination, scientists can accelerate their cheminformatics workflows and make more reliable predictions to guide the discovery of new therapeutic candidates.

Molecular property prediction is a critical task in drug discovery and chemical sciences, enabling the rapid screening of compounds and accelerating the identification of promising candidates [25] [8]. The core challenge lies in transforming molecular structures into numerical representations that machine learning algorithms can process. The choice of molecular representation significantly influences the predictive performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency of the resulting models [26] [2]. This application note provides a comparative overview of three dominant representation paradigms: expert-crafted descriptors and fingerprints, learned graph-based representations, and features extracted from large language models (LLMs). Framed within the context of building a molecular property predictor using the established Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost pipeline, we detail protocols, benchmark performance, and provide practical toolkits for implementation.

Molecular Representation Paradigms: A Technical Comparison

The transformation of molecular structures into a numerical vector is a fundamental step in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling. We examine three primary approaches, summarizing their key characteristics, advantages, and limitations in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Approaches

| Representation Type | Key Examples | Generation Process | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert-Crafted Features | Morgan Fingerprints (ECFPs) [27], Molecular Descriptors [25] | Pre-defined algorithms or calculations based on chemical rules. | High interpretability, computational efficiency, works well on small datasets [26] [2]. | Limited to existing human knowledge, may miss novel complex patterns [25]. |

| Graph-Based Representations | Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) [26], Directed MPNN (D-MPNN) [26] | Learned end-to-end from molecular graph structure via neural networks. | No need for feature engineering; can capture complex, non-linear structure-property relationships [26]. | High computational cost; requires large amounts of data; less interpretable [26]. |

| Language Model-Based Features | LLM4SD [25], Knowledge fusion from GPT-4o, DeepSeek-R1 [25] | Generated by prompting LLMs to provide knowledge or code for molecular vectorization. | Leverages vast prior knowledge from human corpora; can infer beyond structural data [25]. | Susceptible to knowledge gaps and hallucinations; performance varies for less-studied properties [25]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Empirical evaluations across diverse chemical endpoints reveal the relative performance of these representations when paired with powerful machine learning models. The following table summarizes key benchmark results from recent literature, highlighting the consistent competitiveness of the Morgan fingerprint and XGBoost pipeline.

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance Across Representations and Models

| Representation | Model | Dataset / Task | Key Performance Metrics | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints | XGBoost | 16 classification & regression datasets (94 endpoints) | Generally achieved the best predictive performance among gradient boosting implementations [28]. | [28] |

| Morgan Fingerprints | XGBoost | Odor prediction (10 sources, 8681 compounds) | AUROC: 0.828, AUPRC: 0.237; outperformed descriptor-based models [2]. | [2] |

| Graph Convolutions (D-MPNN) | Hybrid (Graph + Descriptors) | 19 public & 16 proprietary industry datasets | Matched or outperformed fixed fingerprints and previous GNNs; strong on large datasets [26]. | [26] |

| LLM-Generated Features | Random Forest | Molecular property prediction (MPP) tasks | Outperformed GNN-based methods on several tasks, demonstrating knowledge utility [25]. | [25] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Random Forest, SVM | General QSAR | Performance highly dependent on descriptor selection and quality [25]. | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Molecular Property Predictor with Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

This protocol provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for constructing a high-performance predictive model using the robust Morgan fingerprint and XGBoost pipeline [27] [28] [2].

Workflow Diagram: Morgan Fingerprint to XGBoost Model

Materials and Reagents

- Software: Python 3.7+, RDKit, scikit-learn, XGBoost, pandas, NumPy.

- Data: A collection of molecular structures in SMILES format and their associated property or activity values.

Procedure

- Process Molecular Structures:

- Input molecular structures as canonical SMILES strings (e.g.,

'C(C[C@@H](C(=O)O)N)CNC(=N)N'for arginine) [27]. - Use the RDKit library to convert SMILES strings into molecule objects.

- Input molecular structures as canonical SMILES strings (e.g.,

Generate Morgan Fingerprints:

- Using the RDKit library, generate the circular (Morgan) fingerprints as bit vectors.

- Key parameters to define:

nBits: The length of the fingerprint vector (e.g., 1024, 2048). A longer vector reduces collisions at the cost of higher dimensionality [27].radius: The maximum bond radius for the circular neighborhood around each atom (e.g., 2 or 3). A larger radius captures larger, more complex substructures [27].useChirality: Set toTrueto include stereochemical information.

Convert and Prepare Data:

- Convert the fingerprint object into a NumPy array for compatibility with machine learning libraries.

- Split the dataset into training and testing sets, using methods like random or scaffold split to assess generalization [26].

Train and Optimize the XGBoost Model:

- Initialize the XGBoost classifier or regressor.

- Conduct hyperparameter optimization to maximize predictive performance. Key hyperparameters to tune include [28]:

n_estimators: The number of boosting rounds.max_depth: The maximum depth of the trees.learning_rate: The step size shrinkage.subsample: The fraction of samples used for training each tree.colsample_bytree: The fraction of features used for training each tree.

- Use a framework like Optuna or scikit-learn's

GridSearchCVfor systematic optimization [28].

Evaluate Model Performance:

- Apply the trained model to the held-out test set.

- Report relevant metrics such as Accuracy, AUROC, AUPRC, RMSE, or R², depending on the task (classification or regression) [2].

Protocol 2: Integrating Large Language Model Knowledge with Structural Features

This protocol outlines a novel approach to enhance molecular property prediction by fusing knowledge extracted from LLMs with structural molecular representations [25].

Workflow Diagram: LLM Knowledge Fusion Framework

Materials and Reagents

- Software: Access to state-of-the-art LLMs (e.g., GPT-4o, GPT-4.1, DeepSeek-R1), a pre-trained molecular graph model.

- Data: A dataset of molecules (SMILES) and their target properties.

Procedure

- Knowledge Extraction via LLM Prompting:

- For a given property prediction task, design prompts for an LLM to generate relevant domain knowledge and executable code snippets.

- The LLM is prompted to provide insights and functions that can be used to vectorize molecules based on the target property [25].

Generate Knowledge-Based Features:

- Execute the generated code to produce a set of numerical features for each molecule in the dataset, resulting in a "knowledge feature" vector [25].

Extract Structural Features:

- In parallel, process the molecular graphs using a pre-trained graph neural network (GNN) to obtain a structural representation vector that captures topological information [25].

Feature Fusion and Model Training:

- Concatenate the knowledge-based feature vector and the structural feature vector to create a fused molecular representation.

- Use this combined representation to train a final predictor model, such as a Random Forest or a neural network, for the target property [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details the key computational tools and their specific functions required to implement the protocols described in this note.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Property Prediction

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [27] [2] | Cheminformatics Library | Converts SMILES to molecular objects; calculates molecular descriptors and generates Morgan fingerprints. |

| XGBoost [29] [28] [2] | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting framework used to train high-performance models on fingerprint and descriptor data. |

| LightGBM [28] [2] | Machine Learning Library | Alternative gradient boosting framework offering faster training times on large datasets. |

| scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Provides data splitting, preprocessing, baseline models, and hyperparameter tuning utilities. |

| Optuna [28] | Hyperparameter Optimization Framework | Enables efficient and automated tuning of model hyperparameters. |

| Large Language Models (e.g., GPT-4o, DeepSeek) [25] | Knowledge Extraction Engine | Generates task-relevant knowledge and code for creating knowledge-based molecular features. |

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) [26] | Graph Neural Network Architecture | Learns molecular representations directly from the graph structure of molecules. |

A Step-by-Step Pipeline: From SMILES Strings to Predictions

The accuracy of a molecular property predictor is contingent upon the quality and consistency of its underlying data. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, building a robust predictor using Morgan fingerprints and XGBoost requires a foundation of meticulously curated and preprocessed molecular datasets. This application note provides detailed protocols for sourcing, standardizing, and featurizing chemical data to enable the development of high-performance models, directly supporting a broader thesis on constructing effective molecular property predictors. We demonstrate that proper data curation is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of model success, with one comparative study showing that a Morgan-fingerprint-based XGBoost model achieved superior discrimination (AUROC 0.828) in odor prediction tasks [2].

Data Sourcing and Collection

The initial phase involves assembling a comprehensive and reliable dataset from expert-curated sources.

Protocol: Data Identification and Aggregation

Objective: To unify molecular structures and their associated properties from multiple public databases into a non-redundant dataset keyed by a unique compound identifier.

Materials:

- Data Sources: Public repositories such as PubChem, ChEMBL, DrugBank, and specialized databases like those listed in Table 1.

- Computational Tools: A scripting environment (e.g., Python) with libraries such as

pyrfumefor accessing archived olfactory data [2] orRDKitfor general cheminformatics. - Identifier: PubChem Compound ID (CID) for standardizing molecular records.

Procedure:

- Source Selection: Identify and select relevant data sources for your target molecular property (e.g., solubility, bioactivity, odor perception).

- Data Retrieval: Programmatically access and download datasets. For example, the

pyrfume-dataGitHub archive provides a unified starting point for olfactory data [2]. - Initial Merging: Combine the source data into a single table using the PubChem CID as the primary key. For CIDs lacking structural information, use PubChem's PUG-REST API to retrieve the canonical Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) string [2].

- Descriptor Labeling: Compile all raw property descriptors (e.g., "Floral," "Spicy," "Potent") associated with each molecule. This creates an initial, non-standardized list of labels for each compound.

Data Source Examples

Table 1: Exemplar Data Sources for Molecular Datasets

| Source Name | Description | Content Focus |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem | A public repository of chemical molecules and their activities | Massive collection of structures, bioactivities, and more |

| ChEMBL | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Drug discovery, ADMET properties |

| TGSC | The Good Scents Company Information System | Fragrance and flavor compounds |

| IFRA | International Fragrance Association Fragrance Ingredient Glossary | Expert-curated fragrance ingredients |

| MoleculeNet | A benchmark collection of datasets for molecular machine learning | Various properties (e.g., Solubility, Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration) |

Data Standardization and Curation

Raw, aggregated data is often inconsistent and contains errors. Standardization transforms this raw data into a clean, analysis-ready format.

Protocol: Molecular Standardization and Sanitization

Objective: To convert diverse molecular representations into a consistent, canonical, and chemically valid form using a structured preprocessing pipeline.

Materials:

- Software/Libraries:

RDKitordatamol(a wrapper simplifying RDKit operations) [30]. - Input: List of raw SMILES strings from the aggregation phase.

Procedure: Execute the following steps for each SMILES string in the dataset:

- Conversion to Mol Object: Convert the SMILES string into a molecular object

dm.to_mol(row[smiles_column], ordered=True)[30]. - Error Fixing: Attempt to fix common errors in the molecular structure

dm.fix_mol(mol)[30]. - Sanitization: Ensure the molecule is chemically realistic. This includes:

- Standardization: Apply a series of transformations to generate a canonical representation.

- Normalization: Correct drawing errors and standardize functional groups

normalize=True[30]. - Reionization: Ensure the correct protonation state of acidic/basic groups

reionize=True[30]. - Stereochemistry: Reassign stereochemical information if missing

stereo=True[30]. - Metal Disconnection: Remove associated metallic ions and salts

disconnect_metals=False(Enable if salts are not relevant) [30] [31].

- Normalization: Correct drawing errors and standardize functional groups

- Canonical SMILES Generation: Convert the standardized molecule back to a canonical SMILES string

dm.standardize_smiles(dm.to_smiles(mol))[30]. This ensures each unique molecule has a single, unique string representation.

The following workflow diagrams the complete data curation and featurization pipeline:

Protocol: Odor Descriptor Curation

Objective: To map inconsistent, raw odor descriptors from multiple sources to a controlled, standardized vocabulary.

Procedure:

- Define a Controlled Vocabulary: Establish a predefined set of odor labels (e.g., 200 labels plus an "Others" category) guided by domain experts and trusted sources like the IFRA Fragrance Ingredient Glossary [2].

- Label Standardization: Map every raw descriptor from the unified dataset to one of the controlled labels. This process involves:

- Correcting typographical errors and removing leading/trailing whitespace.

- Resolving subjective or language-variant terms (e.g., "rose" vs. "rosy" vs. "rose-like") to a single canonical label.

- Binarization for Multi-label Classification: Encode the standardized odor labels for each molecule into a binary vector using a

MultiLabelBinarizer, where each bit represents the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific odor descriptor [2]. This format is essential for training the multi-label classification model.

Feature Engineering: Molecular Representations

The curated and standardized SMILES strings are converted into numerical features suitable for machine learning.

Protocol: Generating Morgan Fingerprints

Objective: To create a numerical representation of a molecule's structure that encodes the presence of specific substructural patterns within a local radius.

Materials:

- Software/Libraries:

RDKit. - Input: Curated, canonical SMILES strings.

Procedure:

- Convert SMILES to Mol Object: Load the standardized SMILES string into an RDKit molecular object.

- Generate Fingerprint: Use the

GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVectfunction. Key parameters are: - Output: A fixed-length bit vector (e.g., 2048-dimensional) where each bit indicates the presence or absence of a specific circular substructure in the molecule.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Model Performance

This protocol outlines the steps to benchmark the performance of a molecular property predictor using the curated data and engineered features.

Protocol: Model Training and Evaluation with XGBoost

Objective: To train and evaluate an XGBoost model on Morgan fingerprints for multi-label property prediction, providing a benchmark for performance.

Materials:

- Software/Libraries: Python with

scikit-learnandXGBoostlibraries. - Input: The dataset of Morgan fingerprints and binarized property labels.

Procedure:

- Data Partitioning: Split the dataset into training (80%) and test (20%) sets. Use stratified splitting to maintain the distribution of positive and negative examples for each label across splits [2].

- Model Training:

- For each odor or property label in the multi-label set, train a separate binary XGBoost classifier in a one-vs-all fashion.

- Use the Morgan fingerprints as the feature matrix (X) and the binarized label for the specific property as the target (y) for each classifier.

- Hyperparameters: Utilize XGBoost's second-order gradient optimization and L1/L2 regularization, which are particularly effective for high-dimensional, sparse fingerprint data [2].

- Model Validation: Perform stratified 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to tune hyperparameters and obtain robust performance estimates.

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set. Record key metrics including:

- Accuracy: The fraction of correctly classified instances.

- AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes.

- AUPRC (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve): More informative than AUROC for imbalanced datasets.

- Precision and Recall: The proportion of positive predictions that are correct and the proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified, respectively [2].

Performance Benchmarking

The following table summarizes the expected performance of different feature and model combinations, as demonstrated in a comparative study on odor decoding [2].

Table 2: Benchmarking Model Performance on a Molecular Property Prediction Task [2]

| Feature Set | Model | AUROC | AUPRC | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | XGBoost | 0.828 | 0.237 | 97.8 | 41.9 | 16.3 |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | LightGBM | 0.810 | 0.228 | - | - | - |

| Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | Random Forest | 0.784 | 0.216 | - | - | - |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | XGBoost | 0.802 | 0.200 | - | - | - |

| Functional Groups (FG) | XGBoost | 0.753 | 0.088 | - | - | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit for manipulating molecules and calculating descriptors. | Core library for SMILES conversion, standardization, sanitization, and Morgan fingerprint generation. |

| datamol | A user-friendly wrapper around RDKit to simplify common molecular processing tasks. | Used to streamline the multi-step standardization and sanitization pipeline [30]. |

| XGBoost | An optimized gradient boosting library designed for efficiency and high performance. | The machine learning algorithm of choice for training the final molecular property predictor on fingerprint data [2]. |

| PubChem PUG-REST API | A programmatic interface to retrieve chemical structures and properties from PubChem. | Fetching canonical SMILES strings for compounds identified by their PubChem CID during data sourcing [2]. |

| pyrfume-data | A project providing unified access to multiple human olfactory perception datasets. | Serves as a primary data source for assembling a curated dataset of odorants [2]. |

| Scikit-learn | A core machine learning library for data mining and analysis. | Used for data splitting, binarizing labels, and evaluating model performance. |

In modern computational chemistry and drug discovery, the quantitative representation of molecular structures is a foundational step for building predictive models. Molecular fingerprints, particularly Morgan fingerprints (also known as ECFP-type fingerprints), serve as a powerful technique for converting chemical structures into fixed-length numerical vectors that encode key molecular features. These fingerprints capture essential structural patterns, functional groups, and atomic environments within molecules, enabling machine learning algorithms to learn complex structure-property relationships.

Framed within the broader objective of constructing a high-performance molecular property predictor, this protocol details the practical generation of Morgan fingerprints from SMILES notation using the RDKit cheminformatics toolkit. Subsequent integration with XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting), a leading ensemble machine learning algorithm, creates a robust pipeline for predicting critical molecular properties such as biological activity, solubility, or toxicity. Recent research demonstrates that Morgan fingerprints contribute significantly to improved performance in structure-based virtual screening, with one study reporting an increase in the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPR) from 0.59 to 0.72 when Morgan fingerprints were incorporated into the FRAGSITEcomb method [32]. This combination of sophisticated molecular representation and advanced machine learning provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for accelerating drug discovery and materials development.

Theoretical Foundation: Morgan Fingerprints and XGBoost

Morgan Fingerprints (ECFPs)

The Morgan algorithm provides a circular topological fingerprint that systematically captures molecular substructures and atomic environments. The algorithm operates by iteratively updating atomic identifiers based on connectivity information from neighboring atoms within a specified radius [33]. This process generates identifiers for circular substructures that represent molecular features crucial for structure-activity relationships.

Key Algorithm Parameters:

- Radius: Determines the diameter of the circular environment considered around each atom (typically radius=2, equivalent to ECFP4).

- FP Size: The length of the bit vector representation (commonly 1024, 2048, or 4096 bits).

- Invariants: Atom features used in the initial algorithm iteration (atomic number, connectivity, etc.).

Unlike fragment-based fingerprints, Morgan fingerprints incorporate connectivity information between functional groups, providing a more nuanced representation of molecular structure [32]. This characteristic makes them particularly valuable for similarity searching and machine learning applications in chemoinformatics.

XGBoost for Molecular Property Prediction

XGBoost has emerged as a dominant algorithm in machine learning competitions and scientific applications due to its computational efficiency, handling of missing values, and regularization capabilities that prevent overfitting. In molecular property prediction, XGBoost excels at learning complex, non-linear relationships between fingerprint-encoded structural features and target properties.

Recent studies demonstrate XGBoost's effectiveness in chemical applications. In predicting Minimum Miscibility Pressure (MMP) for CO₂ flooding, an XGBoost model achieved an R² of 0.9845 on testing sets, significantly outperforming traditional methods [34]. Similarly, in hERG blockage prediction, XGBoost models successfully identified interpretable molecular features aligned with empirical optimization strategies [21]. The algorithm's ability to provide feature importance scores further enhances model interpretability, allowing researchers to identify which molecular substructures most significantly influence the predicted property.

Experimental Protocol: From SMILES to Predictive Model

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Component | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Version 2022.09 or later | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for fingerprint generation [35] |

| Python | Version 3.7+ | Programming language environment |

| XGBoost | Version 1.5+ | Gradient boosting library for model building [34] |

| Pandas | Version 1.3+ | Data manipulation and analysis |

| NumPy | Version 1.21+ | Numerical computing operations |

Step-by-Step Workflow