Capturing Motion: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Conformational Changes in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for capturing the conformational changes of proteins and other biomolecules, which are critical...

Capturing Motion: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Conformational Changes in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for capturing the conformational changes of proteins and other biomolecules, which are critical for understanding their function. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of MD, detail key methodological approaches and their direct applications in virtual screening and lead optimization, address common challenges and cutting-edge solutions for enhancing sampling and accuracy, and finally, discuss rigorous validation through integration with experimental data. By synthesizing insights across these four intents, this review highlights the transformative role of MD in driving forward modern, dynamic structure-based drug design.

The Atomic Movie: Understanding Biomolecular Motion Through MD Simulations

The central paradigm of structural biology has evolved dramatically from the classical view that a protein's 3D-fold is statically encoded in its sequence. It is now clear that proteins behave as dynamic entities, constantly changing across temporal and spatial scales spanning several orders of magnitude: from local loop fluctuations in enzyme active sites to large-scale allosteric motions in transmembrane receptors [1]. These large-scale conformational changes are intrinsically encoded in the overall 3D-shape, with external stimuli such as ligand binding, post-translational modifications, and electrochemical gradients serving to drive these natural motions to trigger functional responses [1]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide the computational framework to bridge this gap between static structures and dynamic behavior, enabling researchers to study atomic and molecular motion over time through numerical integration of classical equations of motion [2].

The fundamental challenge that MD addresses lies in the fact that protein function emerges from dynamics—signal transduction, membrane transport, and synaptic communication all rely on molecular switches that cycle between distinct states to enable biological regulation [1]. While experimental techniques like cryo-electron microscopy, X-ray crystallography, and NMR spectroscopy can capture multiple structural snapshots, they often miss the transitional pathways and intermediate states that define mechanistic understanding. MD simulations fill this critical gap by providing atomic-level insight into the temporal evolution of molecular systems, transforming static snapshots into dynamic ensembles that represent the complete conformational landscape of biomolecules [1].

Theoretical Foundations of Molecular Dynamics

Basic Principles and Algorithms

Molecular dynamics simulations are founded on the principles of classical mechanics, treating atoms as point masses interacting through defined force fields [2]. The core computational approach involves numerically solving Newton's equations of motion to determine the trajectories of all atoms in a system over time. The forces acting on each atom are derived from the gradient of the potential energy function, which describes both bonded interactions (bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic forces) [2].

The choice of integration algorithm critically affects simulation stability, accuracy, and efficiency. The most common methods are based on finite difference approximations:

- Verlet Algorithm: Calculates positions at the next time step using current positions, velocities, and accelerations [2]

- Leapfrog Algorithm: A variation that updates positions and velocities at half-time steps, providing better energy conservation and stability [2]

These methods typically employ time steps of 1-2 femtoseconds to accurately capture atomic vibrations while maintaining reasonable computational cost.

Force Fields and Potential Energy Functions

Force fields represent parameterized sets of equations and associated constants used to calculate potential energy and forces in MD simulations [2]. These mathematical models balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy, incorporating terms for both bonded and non-bonded interactions:

- Bonded terms: Include bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional dihedral potentials

- Non-bonded terms: Comprise van der Waals interactions (modeled with Lennard-Jones potentials) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law) [2]

Common force fields like CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OPLS are optimized for different biomolecular systems, with ongoing development efforts focused on improving accuracy for specific applications such as membrane proteins, nucleic acids, and post-translational modifications.

Table 1: Common Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Force Field | Best Suited For | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | Proteins, lipids | Polarizable force fields available |

| AMBER | Proteins, nucleic acids | Good for DNA/RNA simulations |

| GROMOS | Biomolecules in solution | Unified atom approach |

| OPLS | Organic molecules, proteins | Optimized for liquid properties |

Thermodynamic Ensembles in MD Simulations

Thermodynamic ensembles define the macroscopic conditions under which MD simulations are performed, each characterized by the conservation of specific thermodynamic quantities [3] [2]. The choice of ensemble depends on the system of interest and the experimental conditions being mimicked:

Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE): Maintains constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy, representing an isolated system with no energy or particle exchange with the environment [3] [2]. While conceptually simple, NVE simulations may not represent realistic experimental conditions where temperature and pressure fluctuations occur.

Canonical Ensemble (NVT): Maintains constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature using thermostat algorithms (Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen) to control temperature and mimic system contact with a heat bath [3] [2]. This ensemble is commonly used in equilibration and production runs to study systems at fixed temperature.

Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble (NPT): Maintains constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature using both thermostat and barostat algorithms (Parrinello-Rahman, Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston) [3] [2]. This ensemble closely mimics standard laboratory conditions and is often used for studying phase transitions or calculating density properties.

Grand Canonical Ensemble (μVT): Maintains constant chemical Potential (μ), Volume, and Temperature, allowing particle exchange with a reservoir [3]. This ensemble is particularly useful for studying adsorption processes or ion channel permeation but is less commonly implemented in standard MD software.

Practical Implementation of Ensembles

In practice, MD simulations typically employ multiple ensembles throughout different stages of the simulation protocol [3]. A standard approach begins with energy minimization to remove unfavorable atomic clashes, followed by an NVT simulation to bring the system to the desired temperature (equilibration), then an NPT simulation to achieve the correct density and pressure (further equilibration), and finally a production run in the NPT ensemble to collect data for analysis [3].

Table 2: Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | Physical Interpretation | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles, Volume, Energy | Isolated system | Studying intrinsic dynamics; conserved quantities |

| NVT | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | System in thermal contact with heat bath | Equilibration; fixed-temperature studies |

| NPT | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | System in thermal and mechanical contact with environment | Mimicking laboratory conditions; density calculations |

| μVT | Chemical potential, Volume, Temperature | Open system exchanging particles with reservoir | Adsorption studies; membrane permeation |

Thermostats and barostats implement these ensembles by applying corrective algorithms to atomic velocities (for temperature control) or simulation box dimensions (for pressure control), ensuring that the system samples the appropriate thermodynamic state while maintaining numerical stability throughout the simulation [3].

Enhanced Sampling Methods for Conformational Changes

Overcoming Timescale Limitations

A fundamental challenge in conventional MD is the timescale limitation—many biologically relevant conformational changes occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales or longer, while typical atomistic simulations reach only nanosecond to microsecond durations [1] [4]. This discrepancy arises because functional transitions often involve crossing high energy barriers, making them rare events in simulation timeframes [4]. Enhanced sampling methods have been developed to address this limitation by accelerating the exploration of configuration space and facilitating barrier crossing.

Key Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD): This method applies a continuous bias potential that raises energy wells below a certain threshold, reducing energy barriers and increasing the frequency of transitions between states [4]. aMD does not require predefinition of reaction coordinates and converges to the proper canonical distribution, making it particularly valuable for exploring complex conformational landscapes without advanced knowledge of the system's dynamics.

Umbrella Sampling: This technique employs a series of biasing potentials along a chosen reaction coordinate to enhance sampling of high-energy regions [2]. The biased simulations are subsequently reweighted using methods like the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile along the coordinate of interest.

Metadynamics: This approach gradually builds a history-dependent potential as a sum of Gaussian functions deposited along selected collective variables (CVs) [2]. As the simulation progresses, the biasing potential fills energy minima, encouraging the system to escape local traps and explore new regions of conformational space.

Replica Exchange: Also known as parallel tempering, this method simultaneously runs multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures or Hamiltonians [2]. Periodic configuration swaps between replicas according to the Metropolis criterion allow enhanced sampling of conformational space, particularly for systems with rugged energy landscapes.

Table 3: Enhanced Sampling Methods for Studying Conformational Changes

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated MD | Applies continuous bias potential to reduce energy barriers | No need for predefined reaction coordinates; good for unknown landscapes | Can be challenging to extract accurate kinetics |

| Umbrella Sampling | Biasing potential along a reaction coordinate | Provides free energy profiles along specific coordinates | Requires prior knowledge of relevant coordinates |

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias using Gaussian potentials | Adaptively explores configuration space | Choice of collective variables critical for success |

| Replica Exchange | Parallel simulations at different temperatures | Effectively samples rugged energy landscapes | Computationally expensive; many replicas needed |

Practical Implementation and Protocol

System Setup and Equilibration

Proper system preparation is crucial for obtaining physically meaningful results from MD simulations. The process typically begins with obtaining initial coordinates from experimental structures (X-ray crystallography, NMR) or computational models, followed by solvation in an explicit solvent box, addition of ions to achieve physiological concentration and neutrality, and careful energy minimization to remove atomic clashes [2].

The equilibration phase allows the system to relax and reach a stable state before production data collection. This typically involves a multi-stage process beginning with NVT simulation to reach the target temperature (often 300K for biological systems), followed by NPT simulation to achieve the correct density and pressure [3] [2]. During equilibration, system properties (temperature, pressure, energy) are monitored to ensure they fluctuate around stable target values before proceeding to production runs.

Boundary Conditions and Long-Range Interactions

Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are commonly employed to mimic infinite systems and eliminate surface effects [2]. In PBC, the simulation box is replicated in all directions, with atoms that exit one side re-entering from the opposite side, maintaining a constant number of particles. For electrostatic interactions, special techniques like Ewald summation, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), or Particle-Particle Particle-Mesh (PPPM) methods are used to handle long-range forces accurately and efficiently in periodic systems [2].

Analysis of MD Trajectories

Extracting Structural and Dynamical Information

The analysis of MD trajectories involves extracting meaningful information from simulated atomic positions and velocities over time. Key structural properties include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability and convergence

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible protein regions

- Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs): Characterizes solvent and ion structure around solutes

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Quantifies stability of specific interactions

Important dynamical properties include:

- Mean Square Displacement (MSD): Used to calculate diffusion coefficients

- Velocity Autocorrelation Functions: Provide information about vibrational modes

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies collective motions dominating conformational changes [1]

Quantifying Conformational Changes

Advanced analysis techniques can identify and quantify functionally relevant conformational transitions. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces the dimensionality of trajectory data to reveal the essential dynamics and collective motions responsible for large-scale conformational changes [1]. By projecting trajectories onto principal components derived from experimental structures or simulation data, researchers can visualize pathways between functional states and identify intermediate conformations.

Free energy calculations from enhanced sampling methods provide quantitative measures of the thermodynamic stability of different conformational states and the energy barriers between them [2] [4]. These calculations enable researchers to connect atomic-level interactions with macroscopic thermodynamic properties, offering deep insight into the determinants of conformational equilibria.

Table 4: Essential Software and Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM | Perform the numerical integration of equations of motion |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins | PLUMED, COLVARS | Implement advanced sampling methods |

| System Setup Tools | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL, tleap | Prepare initial structures and simulation boxes |

| Visualization Software | VMD, Chimera, PyMOL | Visualize trajectories and analyze structural features |

| Analysis Packages | MDAnalysis, MDTraj, Bio3D | Process trajectories and calculate properties |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GROMOS | Provide parameters for potential energy calculations |

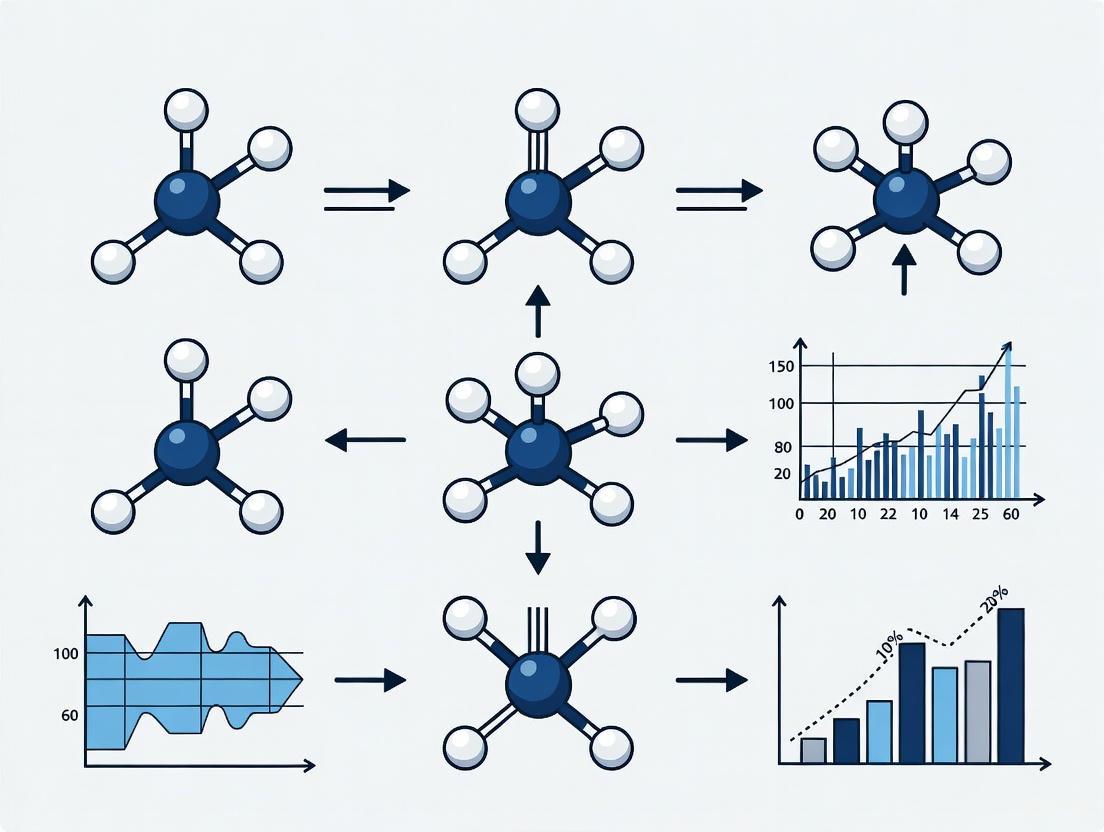

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Standard MD Simulation Workflow

Molecular dynamics simulations have fundamentally transformed our approach to understanding biological molecules by bridging the gap between static structural snapshots and dynamic functional ensembles. The core principle of MD—that biological function emerges from molecular motion—has driven methodological advances that now enable researchers to simulate complex conformational changes relevant to cellular processes. As sampling algorithms, force fields, and computational hardware continue to improve, MD simulations will play an increasingly central role in connecting atomic-level interactions with physiological function, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and biomolecular engineering. The integration of MD with experimental structural biology has already begun to break the barriers between in silico, in vitro, and in vivo worlds, shedding new light onto complex biological problems that were previously inaccessible [1].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation functions as a computational microscope, allowing researchers to observe the intricate jiggling and wiggling of atoms that underpin biological function. For researchers and drug development professionals, MD provides an atomic-resolution view of processes that are often impossible to capture through experimental methods alone—particularly the large-scale conformational changes essential to protein function, signal transduction, and molecular recognition [5]. The predictive power of this computational framework rests on two foundational pillars: the empirical parameters of force fields that describe atomic interactions, and the deterministic laws of Newtonian mechanics that propagate these interactions through time. This primer examines the integration of these components, focusing specifically on their application in elucidating protein conformational changes—a phenomenon central to rational drug design and understanding disease mechanisms.

Newtonian Mechanics: The Motion Engine

Fundamental Laws Governing Atomic Motion

At the heart of every MD simulation lies Newtonian mechanics, which provides the mathematical formalism for predicting how atomic positions evolve over time. The framework is built upon Newton's laws of motion, adapted for microscopic systems [6]:

- Law of Inertia: A particle remains at rest or in uniform motion unless acted upon by a net external force. This principle establishes that any change in a particle's velocity must result from forces described by the force field.

- Equation of Motion: The time rate of change of a particle's momentum equals the force acting upon it, expressed as ( \mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a} ) for constant mass, where ( \mathbf{F} ) is the force vector, ( m ) is mass, and ( \mathbf{a} ) is the acceleration vector [7] [6].

- Action and Reaction: The mutual forces between two particles are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. In MD applications, this typically follows the strong form where forces are also central—acting along the line connecting the particles [6].

These laws are applied within an inertial frame of reference, where the equations of motion assume their simplest form [8]. For a system of N particles, the equation of motion for each particle ( i ) is given by: [ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i ] where ( \mathbf{r}i ) is the position vector of particle ( i ), and ( \mathbf{F}i ) is the total force acting upon it, obtained from the negative gradient of the potential energy function: ( \mathbf{F}i = -\nabla{\mathbf{r}i} U ) [6].

Numerical Integration and Sampling

While Newton's laws provide the theoretical foundation, their practical implementation requires numerical integration due to the analytical intractability of solving for all atomic coordinates in complex biomolecular systems. Simulation software uses algorithms like Verlet's method to propagate the system through discrete time steps, typically on the femtosecond scale [9]: [ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) \approx 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}(t)}{m} \Delta t^2 ] This numerical approach allows MD to track atomic trajectories, but a significant challenge emerges: the timescales of functional protein transitions (microseconds to milliseconds) often exceed what conventional MD can readily simulate [5]. This sampling problem has driven the development of enhanced methods like Markov State Models (MSMs), which combine many short simulations to predict long-timescale dynamics, and machine learning approaches that can identify transition paths between conformational states [5] [10].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Newtonian Mechanics for MD

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Role in MD Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Equation of Motion | ( \mathbf{F} = m\frac{d^2\mathbf{r}}{dt^2} ) | Determines atomic acceleration from force |

| Linear Momentum | ( \mathbf{p} = m\mathbf{v} ) | Conserved in the absence of external forces |

| Numerical Integration | ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) \approx 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}(t)}{m}\Delta t^2 ) | Advances the system in discrete time steps |

| Center of Mass Motion | ( M\ddot{\mathbf{X}}_G = \mathbf{F}^{(e)} ) | Describes overall movement of the molecular system |

Force Fields: The Interaction Potential

Energy Functions and Parameters

Force fields provide the empirical potential energy functions that quantify the forces acting on each atom. These functions represent the potential energy surface upon which atoms move according to Newton's laws. In classical MD, the total potential energy ( U ) is decomposed into bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [11] [9] [12].

The bonded interactions maintain structural integrity and include:

- Bond Stretching: Energy required to stretch or compress bonds from their equilibrium length, modeled as a harmonic spring: ( V{\text{bond}} = Kb(b - b_0)^2 ) [11]

- Angle Bending: Energy associated with bending between three connected atoms from their equilibrium angle: ( V{\text{angle}} = K{\theta}(\theta - \theta_0)^2 ) [11]

- Torsional Rotation: Energy for rotation around a central bond, described by a periodic function: ( V{\text{dihedral}} = K{\phi}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) [11]

The non-bonded interactions describe intermolecular forces and interactions between non-bonded atoms:

- van der Waals Forces: Modeled using the Lennard-Jones potential to account for attractive and repulsive forces: ( V{\text{vdW}} = \epsilon\left[\left(\frac{R{\text{min}}}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{R_{\text{min}}}{r}\right)^6\right] ) [11]

- Electrostatic Interactions: Described by Coulomb's law between partial atomic charges: ( V{\text{elec}} = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r} ) [11]

Table 2: Force Field Energy Terms and Typical Parameters

| Energy Term | Functional Form | Example Parameters | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( Kb(b - b0)^2 ) | ( Kb ): 100-400 kcal/mol/Ų( b0 ): 1.2-1.5 Š| Atomic connectivity |

| Angle Bending | ( K{\theta}(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | ( K_{\theta} ): softer than bond terms | Molecular geometry |

| Dihedral Torsion | ( K_{\phi}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) | ( K_{\phi}, n, \delta ): variable | Electron orbital effects |

| van der Waals | ( \epsilon\left[\left(\frac{R{\text{min}}}{r}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{R{\text{min}}}{r}\right)^6\right] ) | ( \epsilon ): well depth( R_{\text{min}} ): vdW radius | Transient charge fluctuations |

| Electrostatic | ( \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r} ) | ( qi, qj ): partial charges | Permanent charge distribution |

Force Field Classifications and Development

Force fields are categorized into classes based on their complexity and the physical effects they incorporate:

- Class I: Includes basic bonded terms and simple non-bonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and fixed point charges). Examples include AMBER, CHARMM, GAFF, and OPLS, which are widely used for biomolecular simulations [9].

- Class II: Incorporates additional cross-terms such as bond-bond and bond-angle couplings to better represent energy distributions, exemplified by PCFF [9].

- Class III: Includes polarizable force fields like AMOEBA that account for electronic polarization effects by allowing charges to respond to their local environment [9].

Recent developments have expanded force field capabilities:

- Reactive Force Fields: Methods like ReaxFF enable bond formation and breaking during simulations by using bond-order formalism [9].

- Machine Learning Force Fields: ML-based approaches (e.g., DeepMD) learn potential energy surfaces from quantum mechanical data, offering near-quantum accuracy with reduced computational cost [9].

Parameterization involves deriving atomic charges through methods like fitting to electrostatic potentials (ESP/RESP), while bond and angle parameters often come from vibrational spectroscopy or quantum mechanical calculations [11]. Transferable force fields allow parameters from small molecules to be applied to larger systems, with new molecules broken down into recognizable fragments for parameter assignment [11].

Investigating Conformational Changes: Methodologies

Sampling Large-Scale Protein Motions

The study of conformational changes—such as those occurring in membrane transporters, ion channels, and signaling proteins—presents unique challenges due to the large spatial scales (up to 10² Å) and long temporal scales (microseconds to milliseconds) involved [5]. Several computational strategies have been developed to address these challenges:

- Coarse-Grained Methods: Models like Elastic Network Models (ENMs) simplify atomic representation to focus on collective motions, often predicting conformational pathways accurately from protein shape alone [5].

- Markov State Models: MSMs combine many short MD simulations to model kinetics and identify metastable states, though they traditionally struggle to characterize transition states at energy barriers [10].

- Enhanced Sampling: Techniques like metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and transition path sampling (TPS) accelerate rare events by biasing simulations or focusing on reactive trajectories [10].

Recent advances include deep learning frameworks like TS-DAR (Transition State identification via Dispersion and vAriational principle Regularized neural networks), which treats transition states as out-of-distribution data points in a hyperspherical latent space, enabling simultaneous identification of all transition states between multiple free energy minima [10].

Experimental Protocols for Transition State Analysis

Protocol: Identifying Transition States with TS-DAR

Input Data Preparation: Collect multiple short MD simulations of the protein system, ensuring coverage of different conformational basins. The dataset should include transition pairs of molecular conformations [10].

Model Architecture Setup: Implement a neural network with an L2-norm/scale layer at the penultimate position. This layer normalizes feature vectors and rescales them by a factor ( \gamma ), projecting conformations onto a hypersphere of radius ( \gamma ) [10].

Loss Function Optimization: Train the model using a combined loss function:

- VAMP-2 Loss: Maximizes the kinetic variance captured by the model, effectively compacting conformations within the same metastable state in the latent space [10].

- Dispersion Loss: Ensures uniform distribution of metastable state centers across the hypersphere, creating separation between energy basins [10].

Transition State Identification: Detect transition states as conformations lying between metastable state centers in the hyperspherical latent space, characterized by high Shannon entropy or specific cosine similarity thresholds to multiple state centers [10].

Validation: Compare identified transition states with those from traditional methods like committor analysis, where a true transition state should have approximately equal probability (0.5) of reaching either connected basin [10].

Figure 1: TS-DAR Workflow for identifying protein conformational transition states from MD simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Studies of Conformational Changes

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM Force Field | Provides parameters for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids; includes Class I energy terms with optimized Lennard-Jones parameters [11]. | Simulating protein-nucleic acid complexes; membrane protein systems [11]. |

| AMBER/GAFF | Class I force fields for organic molecules and biomolecules; widely used for drug-binding studies [9]. | Ligand-receptor interactions; protein folding simulations. |

| ReaxFF | Reactive force field enabling bond formation/breaking during simulations [9]. | Chemical reactions; enzyme catalysis; material degradation. |

| Machine Learning Force Fields | High-accuracy potentials trained on quantum mechanical data; balance between cost and precision [9]. | Systems where electronic effects are crucial; transition metal complexes. |

| Markov State Model Builders | Construct kinetic models from ensemble MD simulations; identify metastable states and transition rates [10]. | Mapping conformational landscapes; predicting folding mechanisms. |

| TS-DAR Framework | Deep learning approach for identifying transition states as out-of-distribution events in latent space [10]. | Pinpointing transient states in allosteric proteins; enzyme conformational pathways. |

| Water Models (TIP3P, SPC/E) | Explicit solvent representations with specific non-bonded parameters; treated as rigid bodies in most implementations [9]. | Solvated biomolecular systems; hydration dynamics. |

Cross-Validation and Integration with Experiments

Validating computational predictions of conformational changes remains essential for establishing biological relevance. Several strategies enable effective cross-validation:

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy: The rapid advancement in cryo-EM resolution allows direct comparison of simulated conformational states with experimental density maps, particularly for large complexes like ribosomes or viral capsids [5].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Residual dipolar couplings and chemical shift perturbations provide constraints on protein dynamics that can validate MD-predicted ensembles [5].

- Single-Molecule FRET: Distance distributions from smFRET experiments offer quantitative metrics for comparing with distance fluctuations observed in simulations [5].

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange: Protection factors from HDX experiments report on solvent accessibility, correlating with simulated structural dynamics [5].

A compelling example of integration is found in studies of the Ribose Binding Protein (RBP), where computational methods like eBDIMS predicted transition pathways that closely matched intermediates observed in crystallographic studies [5]. Similarly, deep learning approaches like TS-DAR have successfully identified transition states in DNA motor proteins that correlate with functional mutagenesis studies [10].

Figure 2: Conformational free energy landscape showing transition states between metastable states.

The synergy between Newtonian mechanics and empirical force fields creates the physics engine that drives molecular dynamics simulations, enabling unprecedented access to protein conformational changes at atomic resolution. As force fields evolve to incorporate more sophisticated physical models like polarizability and chemical reactivity, and as sampling methods overcome temporal barriers through machine learning and enhanced algorithms, the capacity to simulate biologically relevant timescales and mechanisms continues to expand. For researchers in drug development, these advances translate to an enhanced ability to visualize allosteric mechanisms, identify cryptic binding pockets, and rationally design therapeutics that target specific conformational states. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation establishes a powerful cycle of hypothesis generation and testing, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of biomolecular function and creating new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Proteins are not static, rigid structures but exist as dynamic molecules that undergo crucial conformational changes induced by post-translational modifications, binding of cofactors, or interactions with other molecules [13]. The characterization of these conformational changes and their relation to protein function represents a central goal of structural biology [13]. Traditionally, the structure-function paradigm has been deeply rooted in Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis, which posits that a protein's specific biological function is inherently linked to its unique, stable three-dimensional structure [14]. However, this classical view has been challenged by intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and protein regions (IDPRs) that exist as highly dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations rather than adopting a single, stable structural state under physiological conditions [14].

The dynamic nature of proteins is fundamental to their functional repertoire, particularly in cellular processes requiring molecular flexibility and promiscuous interactions [14]. Allostery, one of the most important regulatory mechanisms in biology, describes how effector binding at a distal site changes the functional activity at the active site [15]. While most allosteric studies have historically focused on thermodynamic properties, particularly substrate binding affinity, contemporary research increasingly recognizes that changes in substrate binding affinity by allosteric effectors are mediated by conformational transitions or by changes in the broadness of the free energy basin of the protein conformational state [15]. When effector binding alters the free energy landscape of a protein in conformational space, these changes affect not only thermodynamic properties but also dynamic properties, including the amplitudes of motions on different time scales and rates of conformational transitions [15].

Allosteric Regulation Through Conformational Dynamics

Fundamental Mechanisms of Allostery

Allostery represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism in biological systems where effector binding at one site influences functional activity at a distant active site [15]. This regulation occurs through two primary mechanisms that involve significant conformational changes:

- Conformational Selection: The protein exists in an equilibrium of multiple conformations, and the effector selectively stabilizes one conformation that has different functional properties.

- Induced Fit: The binding of the effector induces a conformational change that alters the protein's functional activity.

The functions of many proteins are regulated through allostery, whereby effector binding at a distal site changes the functional activity, such as substrate binding affinity or catalytic efficiency, at the active site [15]. Most allosteric studies have focused on thermodynamic properties, in particular, substrate binding affinity [15]. Changes in substrate binding affinity by allosteric effectors have generally been thought to be mediated by conformational transitions of the proteins or, alternatively, by changes in the broadness of the free energy basin of the protein conformational state without shifting the basin minimum position [15].

Allosteric Communication Pathways

Allosteric regulation relies on communication pathways that transmit signals from the effector binding site to the functional active site. These pathways can be understood through several theoretical frameworks:

Table 1: Theoretical Models of Allosteric Regulation

| Model | Key Principle | Structural Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) | Proteins exist in pre-equilibrium between tense (T) and relaxed (R) states | Concerted conformational shifts across the protein structure |

| Koshland-Némethy-Filmer (KNF) | Sequential induced fit during ligand binding | Progressive conformational changes induced by binding |

| Conformational Selection | Ligands select from existing conformational ensembles | Population shift among pre-existing states |

| Allostery Without Conformational Change | Changes in dynamics without major structural rearrangement | Alterations in vibrational entropy and dynamics |

The roles of conformational dynamics in allosteric regulation can be investigated through complementary approaches, including NMR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation, which help identify residues involved in allosteric communication [15]. Contentious issues remain in the field, particularly regarding the relationship between picosecond-nanosecond local and microsecond-millisecond conformational exchange dynamics [15].

Methodologies for Studying Conformational Changes

Experimental Approaches

Conventional methods to obtain structural information often lack the temporal resolution to provide comprehensive information on protein dynamics [13]. Several specialized techniques have been developed to characterize protein conformation and dynamics:

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Studying Conformational Dynamics

| Method | Information Provided | Timescale Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) Mass Spectrometry | Solvent accessibility and dynamics | Milliseconds to hours | Protein folding, allosteric mechanisms |

| Limited Proteolysis | Surface accessibility and flexibility | N/A | Domain boundaries, disordered regions |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Atomic-level dynamics and structure | Picoseconds to seconds | Allosteric pathways, conformational exchange |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Global shape and dimensions | Milliseconds | Ensemble properties of IDPs |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | High-resolution structures of complexes | N/A | Large macromolecular machines |

Mass spectrometry-based approaches, such as limited proteolysis, hydrogen-deuterium exchange, and stable-isotope labeling, are frequently used to characterize protein conformation and dynamics [13]. Tools like PepShell allow interactive data analysis of mass spectrometry-based conformational proteomics studies by visualization of the identified peptides both at the sequence and structure levels [13]. Moreover, PepShell enables the comparison of experiments under different conditions, including different proteolysis times or binding of the protein to different substrates or inhibitors [13].

Computational Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has been a fundamental tool in computational structural biology for decades, allowing researchers to explore atomic-level motions of proteins and other biomolecules over time [14] [16]. However, when applied to complex systems like intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), MD faces several inherent limitations. The primary challenge is the sheer size and complexity of the conformational space that IDPs can explore [14]. IDPs, by definition, do not adopt a single, well-defined structure; instead, they exist as an ensemble of interconverting conformations [14]. Capturing this diversity requires simulations that span long timescales—often microseconds (μs) to milliseconds (ms)—to adequately sample the full range of possible states [14].

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow for Conformational Sampling. This diagram outlines the key steps in conventional and enhanced MD simulations used to study protein dynamics.

To overcome timescale limitations, various accelerated MD (aMD) schemes have been developed over the past few decades [16]. The bond-boost method (BBM) is one such aMD scheme that expedites escape events from energy basins by adding a bias potential based on changes in bond length [16]. Recent modifications to BBM construct bias potential using dihedral angles and hydrogen bonds, which are more suitable variables to monitor conformational changes in proteins [16]. These methods have been validated through studies of conformational changes in ribose binding protein and adenylate kinase by comparing conventional and accelerated MD simulation results [16].

Artificial intelligence (AI) offers a transformative alternative to traditional MD, with deep learning (DL) enabling efficient and scalable conformational sampling [14]. DL methods leverage large-scale datasets to learn complex, non-linear, sequence-to-structure relationships, allowing for the modeling of conformational ensembles in IDPs without the constraints of traditional physics-based approaches [14]. Such DL approaches have been shown to outperform MD in generating diverse ensembles with comparable accuracy [14]. Most models rely primarily on simulated data for training, while experimental data serves a critical role in validation, aligning the generated conformational ensembles with observable physical and biochemical properties [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Conformational Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Solvent for HDX-MS; enables deuterium incorporation | Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry |

| Protease Enzymes (Trypsin, Pepsin) | Limited proteolysis; cleaves accessible protein regions | Conformational proteomics, epitope mapping |

| Isotope-labeled Compounds (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | NMR active isotopes for resonance assignment | Protein dynamics studies via NMR spectroscopy |

| Molecular Biology Grade Buffers | Maintain physiological pH and ionic strength | All experimental protocols |

| Cryo-electron Microscopy Grids | Support for vitrified samples | Single-particle analysis of macromolecular complexes |

| MD Simulation Software (LAMMPS, GROMACS) | Molecular dynamics engines | Computational studies of conformational dynamics |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Accelerate barrier crossing in simulations | aMD, GaMD, metadynamics |

| AI/Deep Learning Frameworks | Neural network training for conformational prediction | Deep learning-based structure prediction |

Case Studies: Conformational Dynamics in Biological Systems

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)

Intrinsically disordered proteins challenge traditional structure-function paradigms by existing as dynamic ensembles rather than stable tertiary structures [14]. The intrinsic disorder observed in IDPs is a consequence of their distinctive amino acid compositions—typically enriched in polar and charged residues and depleted in hydrophobic residues [14]. This structural plasticity allows IDPs to explore a wide conformational landscape, enabling functional versatility and adaptability [14].

A notable example of MD-based conformational ensemble exploration is the study of ArkA, a proline-rich IDP from yeast actin patch kinase Ark1p, which regulates actin cytoskeleton assembly [14]. Using Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD), researchers captured proline isomerization events, revealing that all five prolines in Ark1p significantly sample the cis conformation [14]. This led to a more compact ensemble with reduced polyproline II (PPII) helix content, aligning better with in-vitro circular dichroism (CD) data [14]. Biologically, proline isomerization may act as a switch, regulating ArkA's binding to the SH3 domain of Actin Binding Protein 1 (Abp1p) [14]. Since SH3 domains prefer PPII helices, the cis state may slow or modulate binding, affecting signal transduction and actin dynamics, highlighting a broader IDP regulatory mechanism where conformational switching influences protein interactions [14].

Allosteric Proteins

Allosteric proteins demonstrate how conformational changes transmit signals from effector binding sites to active sites. The conformational dynamics of these proteins can be investigated through accelerated MD studies, such as those examining ribose binding protein and adenylate kinase [16]. Based on accelerated MD results, the characteristics of these proteins can be investigated by monitoring conformational transition pathways [16]. The free energy landscape calculated using umbrella sampling confirms that all states identified by accelerated MD simulation represent free energy minima, and the system makes transitions following the path indicated by the free energy landscape [16].

Figure 2: Allosteric Regulation via Conformational Selection. This diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism by which effector binding induces conformational changes that alter protein function.

Future Directions and Challenges

The field of conformational dynamics continues to evolve with several promising research directions and persistent challenges:

Methodological Advancements

Future methodological developments will likely focus on hybrid approaches that integrate multiple techniques. Combining AI-based methods with physical constraints represents a particularly promising direction [14]. Hybrid approaches combining AI and MD can bridge the gaps by integrating statistical learning with thermodynamic feasibility [14]. Future directions include incorporating physics-based constraints and learning experimental observables into deep learning frameworks to refine predictions and enhance applicability [14].

Accelerated molecular dynamics methods continue to be refined for investigating transition pathways in a wide range of protein simulations [16]. Efficient approaches are expected to play a key role in investigating transition pathways in protein simulations, with methods like the modified bond-boost method offering compatibility with popular simulation packages like LAMMPS [16].

Persistent Challenges

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the study of conformational changes:

- Sampling Limitations: Even with enhanced sampling methods, capturing rare events and fully exploring conformational landscapes remains computationally challenging [14].

- Force Field Accuracy: The accuracy of force fields, particularly for intrinsically disordered proteins and non-standard residues, continues to be refined [14].

- Integration of Multi-scale Data: Combining data from different experimental and computational sources into unified models presents both technical and conceptual challenges.

- Biological Interpretation: Connecting observed dynamics to biological function requires careful experimentation and analysis beyond structure determination alone.

AI-driven methods hold significant promise in IDP research, offering novel insights into protein dynamics and therapeutic targeting while overcoming the limitations of traditional MD simulations [14]. As these methods continue to develop, they will undoubtedly provide deeper insights into the fundamental mechanisms of allostery, binding, and function that govern cellular processes.

The study of conformational changes in biomolecules is fundamental to advancing research in molecular dynamics and drug development. These structural rearrangements occur as molecules transition between different stable states on a multidimensional surface known as the energy landscape [17]. For proteins and nucleic acids, these landscapes are characterized by deep wells corresponding to stable conformational states and higher-energy barriers representing transition states between them. The sampling challenge arises from the vastness and complexity of these landscapes, where biologically relevant transitions occur on timescales often far exceeding what is computationally feasible to simulate directly. Understanding these landscapes is particularly crucial for investigating conformational diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, where protein misfolding and aggregation play a central pathophysiological role [17].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a primary tool for studying these phenomena, bridging the gap between static structures from X-ray crystallography or NMR and the dynamic mechanisms that underlie biological function and dysfunction [18]. In pharmaceutical research, the ability to adequately sample conformational space directly impacts the accuracy of predicting drug-target interactions, understanding allosteric mechanisms, and designing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at stabilizing native folds or disrupting pathogenic aggregates [17] [19].

Computational Methodologies for Enhanced Sampling

Fundamental Molecular Dynamics Protocol

A typical MD simulation follows a structured protocol to ensure physical accuracy and numerical stability. The atomic potential energy functions in packages like AMBER describe the system using bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (electrostatic and van der Waals) [18]:

[

V{\text{Amber}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} kr(r - r{eq})^2 + \sum{\text{angles}} k\theta(\theta - \theta{eq})^2 + \sum{\text{dihedrals}} \frac{Vn}{2}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)] + \sum{i

The general workflow for MD simulations involves multiple critical stages [18]:

- System Preparation: Initial structures from experimental data or computational modeling are prepared, including adding missing atoms and determining protonation states.

- Force Field Selection: Appropriate parameters are chosen to describe atomic interactions.

- Solvation and Ion Addition: The biomolecule is immersed in explicit solvent molecules, and ions are added to achieve physiological concentration and neutrality.

- Energy Minimization: Steric clashes are resolved through gradient-based minimization to relieve structural strain.

- System Equilibration: The solvent and ions are relaxed around the biomolecule while restraining heavy atoms, followed by full system equilibration to the target temperature and pressure.

- Production Simulation: Unrestrained MD is performed to collect trajectory data for analysis.

- Analysis: Trajectories are analyzed for structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties.

Table: Essential Software Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Application in Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Amber MD Package [18] | MD simulations with specific force fields | Production simulations and analysis of biomolecules |

| Gaussian [18] | Electronic structure modeling | Partial charge calculation for novel molecules |

| Discovery Studio Visualizer [18] | Molecular visualization and editing | Initial model building and manipulation |

| Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) [18] | Trajectory visualization and analysis | Visualization of conformational changes and measurement of distances, angles, RMSD |

| antechamber [18] | Force field parameter generation | Creates parameters for molecules not in standard libraries |

Advanced Sampling Techniques

To address the sampling challenge directly, several enhanced sampling methods have been developed that effectively reduce energy barriers or modify the potential energy surface to accelerate transitions:

- Metadynamics: This technique enhances sampling by adding a history-dependent bias potential along selected collective variables (CVs) to discourage the system from revisiting previously explored states. The bias is constructed as a sum of Gaussian functions deposited along the trajectory in CV space, effectively "filling" the free energy minima and pushing the system to explore new regions.

- Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD): Also known as parallel tempering, this approach runs multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures simultaneously. Periodic attempts to exchange configurations between adjacent temperatures allow the system to overcome high energy barriers at high temperatures while sampling the Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature.

- Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD): This method adds a non-negative bias potential to the system's potential energy when it falls below a certain threshold, effectively reducing the energy barriers between states while preserving the relative ordering of low-energy minima.

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for selecting an appropriate sampling strategy based on the specific research problem:

Experimental Approaches for Validation

While computational methods generate atomic-level hypotheses about conformational dynamics, experimental validation remains crucial. Several biophysical techniques provide complementary information about structural changes and population distributions.

Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D) is particularly valuable as it enables real-time screening of interactions and detection of conformational changes in proteins and cells by monitoring changes in energy dissipation [20]. For example, QCM-D has been used to study:

- Conformational changes in plasminogen induced by lysine analogues, detected through changes in the protein's tertiary structure [20].

- HIV-1 envelope protein interactions with various compounds, where dissipation changes revealed conformational events [20].

- Amyloid-beta peptide oligomerization in Alzheimer's disease research, where QCM-D measurements showed that oligomers are softer than monomers, potentially relating to their toxicity [20].

Other key experimental methods include:

- Time-resolved X-ray crystallography for visualizing structural changes at atomic resolution

- Single-molecule FRET for observing population distributions and dynamics

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance for characterizing conformational equilibria and dynamics in solution

Table: Experimental Techniques for Validating Conformational States

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Timescale Sensitivity | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| QCM-D [20] | Energy dissipation, structural softness | Milliseconds to hours | Protein misfolding, cell-surface interactions |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, relaxation rates | Picoseconds to seconds | Protein folding dynamics, allosteric mechanisms |

| Single-Molecule FRET | Inter-dye distances, subpopulation distributions | Microseconds to minutes | Conformational heterogeneity in nucleic acids |

| Stopped-Flow | Optical signals, fluorescence | Milliseconds to seconds | Fast folding/unfolding kinetics |

Case Study: Sampling in Conformational Diseases and Drug Design

Protein Misfolding and Amyloid Formation

In conformational diseases, proteins misfold and aggregate into amyloid structures containing "steric zippers" - β-sheet strands that interact through dense hydrogen-bond networks [17]. Sampling these aggregation pathways is challenging due to the slow, stochastic nature of nucleation events. Research on Alzheimer's disease-associated β-amyloid protein (Aβ) and type 2 diabetes-linked Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (hIAPP) reveals that these proteins form polymorphic aggregates including toxic oligomers, protofilaments, and fibers [17].

Novel chemical chaperones represent a therapeutic strategy targeting these aggregation processes. These small molecules can bind to various polymorphic aggregates, inhibiting their development by [17]:

- Stabilizing the native state of proteins

- Destabilizing oligomeric states and protofilaments

- Stabilizing fibrillar structures to decrease toxic oligomers

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for studying these chaperones using integrated computational and experimental approaches:

Research Reagent Solutions for Conformational Disease Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Protein Aggregation and Inhibition

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [17] | Model protein for studying aggregation; shares common meta-structure with IAPP and amyloid fragments | Comparative studies of ligandability when human proteins are cost-prohibitive |

| Novel Chemical Chaperone Family (NCHCHF) [17] | Small molecules that bind to polymorphic aggregates to prevent protein aggregation | Compounds A, B, D, E, F, G with naphthyl groups that interact with aggregation-prone species |

| hIAPP20–29 Fragment [17] | Amyloidogenic decapeptide (SNFFGAILSS) representing the fibrillating core of hIAPP | Study of aggregation mechanisms and screening of anti-aggregation compounds |

| Cerebellar Granule Cells (CGC) [17] | Primary neuronal cell model for cytotoxicity assessment | Evaluation of protection from cytotoxicity induced by hIAPP20–29 or low potassium medium |

| Plasmonic Hybrid Nanogels [19] | Light-responsive drug carriers with gold nanoparticles and thermo-responsive polymers | Spatiotemporally controlled drug delivery via photothermally driven conformational change |

Binding Free Energy Calculations

The Molecular Mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-PB(GB)SA method provides an approach to calculate binding free energies from MD simulations, which is crucial for rational drug design [18]. This method estimates the free energy of binding using the following thermodynamic cycle:

[ \Delta G{\text{bind}} = G{\text{complex}} - (G{\text{receptor}} + G{\text{ligand}}) ]

Where each term is calculated as:

[ G = E{\text{MM}} + G{\text{solv}} - TS ]

The enthalpic component includes molecular mechanics energy (EMM) and solvation free energy (Gsolv), while the entropic contribution (-TS) is often estimated through normal mode analysis or quasi-harmonic approximations. These calculations are particularly valuable for ranking the binding affinities of novel chemical chaperones to amyloid aggregates or native protein structures [17] [18].

The sampling challenge in exploring vast energy landscapes remains a significant bottleneck in molecular dynamics simulations, particularly for studying conformational changes relevant to disease mechanisms and drug development. While advanced sampling algorithms and increasing computational power have expanded accessible timescales, the field continues to develop more efficient methods to bridge the gap between simulation and experimental timescales.

Future directions include the integration of machine learning approaches to identify relevant collective variables, the development of multi-scale methods that combine quantum mechanical with molecular mechanical treatments, and enhanced algorithms for extracting kinetic information from biased simulations. Furthermore, closer integration between computational sampling and experimental validation through techniques like QCM-D will be essential for validating predictions and building quantitative models of conformational dynamics. As these methods mature, they will increasingly impact drug discovery pipelines, enabling the rational design of therapeutics targeting conformational diseases by precisely modulating energy landscapes.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) represent a significant yet challenging frontier in structural biology. Lacking a fixed three-dimensional structure, they exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations, playing critical roles in cellular signaling, regulation, and disease. This whitepaper examines how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for elucidating the conformational landscapes and functional mechanisms of IDPs. We detail advanced MD methodologies that overcome traditional limitations, provide quantitative validation against experimental data, and demonstrate applications in predicting pathogenic variant effects. For researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current protocols, data interpretation frameworks, and emerging opportunities for targeting IDPs therapeutically.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) are ubiquitous functional components of the proteome that perform essential biological roles without folding into stable three-dimensional structures [21]. They are highly abundant in eukaryotes, with an estimated 30-40% of all residues in the eukaryotic proteome located in disordered regions, and approximately 70% of proteins containing either disordered tails or flexible linkers [21]. Their dynamic nature enables critical functions in cell signaling, transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling, and liquid-liquid phase separation – processes where structural plasticity provides functional advantages [21] [22].

The structural characterization of IDPs presents formidable challenges for conventional structural biology methods. Their inherent flexibility makes them resistant to crystallization, rendering X-ray crystallography of limited use [23]. While Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can provide valuable insights, it captures ensemble-averaged data from rapidly interconverting conformations, making it difficult to resolve individual states [24] [23]. Similarly, techniques like small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) provide low-resolution structural information but lack atomic-level detail [24].

Molecular Dynamics simulations effectively bridge this resolution gap by providing atomic-level, time-resolved trajectories of IDP conformational ensembles [24]. With advancements in sampling algorithms and force field accuracy, MD has emerged as a prime computational technique for investigating the structure-function relationship of IDPs, offering insights that complement and extend experimental observations.

The Computational Challenge of Simulating Disorder

Sampling and Force Field Limitations

Simulating IDPs presents two fundamental computational challenges: adequate sampling of the vast conformational space and force field accuracy in modeling disordered states. Standard MD simulations often suffer from insufficient sampling due to the high flexibility of IDPs and the long timescales required to observe biologically relevant transitions [24]. Force fields parameterized primarily using folded proteins may introduce bias toward overly compact or structured states, failing to accurately reproduce the ensemble properties of IDPs [24].

Enhanced Sampling Methodologies

To address these limitations, advanced sampling techniques have been developed:

Hamiltonian Replica-Exchange MD (HREMD): This method enhances conformational sampling by running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) with scaled Hamiltonians, allowing systems to overcome energy barriers through exchange between replicas. HREMD has demonstrated remarkable success in generating unbiased ensembles consistent with SAXS, SANS, and NMR data for IDPs of varying lengths and sequence complexities [24].

Coarse-Grained Simulations: By reducing the number of degrees of freedom, coarse-grained models enable longer timescale simulations while preserving essential biophysical properties. The MDmis method utilizes coarse-grained MD simulations to extract biophysical features for predicting variant pathogenicity in IDRs [25].

Table 1: Comparison of MD Sampling Approaches for IDPs

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard MD | Unbiased Newtonian dynamics | Simple implementation; Physical trajectory | Limited by computational cost; Sampling challenges | Short timescale dynamics; Local fluctuations |

| HREMD | Scaled Hamiltonians enable barrier crossing | Enhanced sampling efficiency; Generates accurate ensembles | Increased computational cost; Complex setup | Full ensemble generation for 24-95 residue IDPs [24] |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Reduced representation of system | Longer timescales accessible; Efficient for large systems | Loss of atomic detail; Parameterization challenges | Proteome-wide variant effect prediction (MDmis) [25] |

Experimental Protocols for MD Validation

Integrated MD-Experimental Workflow for IDP Ensemble Validation

Accurate characterization of IDPs requires integration of MD simulations with multiple experimental validation techniques. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive protocol for generating and validating IDP ensembles:

Protocol 1: HREMD for Unbiased Ensemble Generation

This protocol describes the implementation of Hamiltonian Replica-Exchange MD to generate accurate structural ensembles of IDPs, as validated in recent studies [24].

System Setup

- Obtain the IDP amino acid sequence and generate an extended initial conformation.

- Solvate the protein in a cubic water box with a minimum 15 Å padding between the protein and box edges.

- Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Select appropriate force fields optimized for IDPs (e.g., Amber ff03ws with TIP4P/2005s or Amber ff99SB-disp with TIP4P-D).

Simulation Parameters

- Set up 24-64 replicas with scaling factors exponentially distributed between 1.0 (unmodified) and modified Hamiltonians.

- Use an exchange attempt frequency of 1-2 ps.

- Run each replica for 500 ns (for IDPs up to 100 residues) using a 2-fs integration time step.

- Maintain constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 bar) using appropriate thermostats and barostats.

Validation Metrics

- Calculate theoretical SAXS/SANS profiles from the ensemble and compare to experimental data using χ² statistics.

- Compute NMR chemical shifts (using tools like SHIFTX2) and compare to experimental values via root-mean-square error.

- Assess convergence through replica exchange statistics and time-evolution of ensemble properties (Rg, secondary structure).

Protocol 2: Biophysical Feature Extraction for Pathogenicity Prediction (MDmis)

The MDmis workflow leverages MD simulations to predict pathogenic missense variants in IDRs [25].

Simulation Setup

- Run coarse-grained MD simulations of wild-type and variant IDR sequences.

- Simulate sufficient duration to capture transient structural elements (typically 1-10 μs).

- Employ solvation models appropriate for the chosen coarse-grained force field.

Feature Extraction

- Calculate Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) - mean and standard deviation over trajectory.

- Compute Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF) - normalized by mean fluctuation.

- Determine secondary structure assignments - proportion of frames in each state.

- Extract chi, phi, and psi angles - distribution percentiles across trajectory.

- Identify bonding interactions - count interactions persisting >40% of trajectory.

- Calculate residue movement covariance - z-scored mean values.

Machine Learning Integration

- Train Random Forest classifiers using a window around mutation sites.

- Combine MD-derived features with evolutionary features (sequence entropy, charge patterning).

- Validate predictions against known pathogenic and benign variants from ClinVar and PrimateAI.

Quantitative Data and Validation

Performance Benchmarks of MD Approaches

Validation against experimental data is crucial for assessing the accuracy of MD simulations. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different MD methodologies:

Table 2: Validation Metrics for IDP MD Simulations

| Method | Force Field | IDP System | NMR Chemical Shift RMS Error | SAXS χ² | Convergence Time | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HREMD [24] | a99SB-disp | SH4UD (95 residues) | Cα: 0.52 ppm, Cβ: 0.52 ppm | 1.2 | ~400 ns | SAXS, SANS, NMR chemical shifts |

| HREMD [24] | a03ws | Sic1 (92 residues) | Cα: 0.58 ppm, Cβ: 0.55 ppm | 1.8 | ~300 ns | SAXS, SANS, NMR chemical shifts |

| HREMD [24] | a99SB-disp | Histatin5 (24 residues) | Cα: 0.48 ppm, Cβ: 0.49 ppm | 0.9 | ~100 ns | SAXS, SANS, NMR chemical shifts |

| Standard MD [24] | a99SB-disp | SH4UD (95 residues) | Cα: 0.53 ppm, Cβ: 0.53 ppm | 15.6 | >5 μs (inconvergent) | NMR chemical shifts only |

| MDmis [25] | Coarse-grained | Long IDRs (>100 residues) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pathogenicity prediction (AUROC-0.1: 0.29-0.61) |

Key Biophysical Features for Pathogenicity Prediction

Analysis of pathogenic variants in IDRs reveals distinct biophysical manifestations based on region length:

Table 3: MD-Derived Features Discriminating Pathogenic Variants in IDRs

| Feature Category | Specific Metrics | Long IDR Pathogenic Variants | Short IDR Pathergic Variants | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transient Structure | Secondary structure propensity | Increased disorder-to-order transition | Minimal change | DSSP from MD trajectories [25] |

| Solvent Access | SASA (mean, standard deviation) | Depleted solvent accessibility | Minimal change | SASA calculation [25] |

| Dynamic Fluctuation | RMSF (normalized) | Altered fluctuation patterns | Weak signal | Cα atomic positions [25] |

| Bonding Interactions | H-bonds, salt bridges | Altered interaction persistence (>40% trajectory) | PTM site enrichment | Contact analysis [25] |

| Chain Statistics | Persistence length, Rg | Modified global dimensions | Weak signal | Polymer physics models [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful MD analysis of IDPs requires integration of specialized computational tools and experimental methods. The following table catalogues essential resources mentioned in recent literature:

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IDP-MD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Function in IDP Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Force Fields | Amber ff99SB-disp [24] | Optimized for disordered proteins; improved water interactions | Accurate ensemble generation for Sic1, SH4UD [24] |

| MD Force Fields | CHARMM c36m [26] | Modified to reflect residual flexibility in IDPs | Nvjp-1 monomer and dimer simulations [26] |

| Enhanced Sampling | HREMD Pluggins [24] | Hamiltonian replica-exchange for enhanced conformational sampling | Unbiased ensemble generation [24] |

| Analysis Software | MDTraj, MDAnalysis [25] | Trajectory analysis for SASA, RMSF, secondary structure | Feature extraction in MDmis [25] |

| Experimental Validation | NMR Chemical Shifts [24] | Validation of local structural propensities | Force field optimization [24] |

| Experimental Validation | SAXS/SANS [24] | Validation of global chain dimensions | Ensemble validation against scattering data [24] |

| Specialized MS | Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange MS [23] | Probing solvent accessibility and dynamics | Conformational ensemble characterization [23] |

| Specialized MS | Native Mass Spectrometry [23] | Assessing structural preferences and stoichiometry | Charge state distribution analysis [23] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Hamiltonian Replica-Exchange [24] | Improved configuration space sampling | Accurate IDP ensembles [24] |

IDP Dynamics in Biomolecular Condensates

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) represents a critical functional context for many IDPs, particularly in membrane-less organelles and signaling condensates. MD simulations provide unique insights into how conformational dynamics regulate condensate formation and properties.

Dynamics Across Timescales

The diagram below illustrates the hierarchical dynamics of IDPs within biomolecular condensates and appropriate techniques for their study:

Upon phase separation, IDPs experience restricted translational diffusion and modulated internal dynamics due to increased viscosity and intermolecular interactions within condensates [27]. MD simulations reveal that these changes affect timescales from picosecond sidechain motions to microsecond reconfiguration of the entire chain. The interplay between transient secondary structures and chain solvation emerges as a key determinant of condensate stability and dynamics, with pathogenic mutations often perturbing this delicate balance [25] [27].

Molecular Dynamics simulations have transformed our ability to study Intrinsically Disordered Proteins, moving from static structural depictions to dynamic ensemble-based understanding. The integration of enhanced sampling methods with optimized force fields now enables accurate prediction of IDP conformational landscapes and their functional implications. As MD methodologies continue to advance, we anticipate increased application in drug discovery targeting IDPs [22] [28], predictive pathology of variants in disordered regions [25], and multiscale modeling of biomolecular condensates [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, MD analysis of IDPs represents not just a computational tool, but an essential component of the integrated structural biology toolkit for targeting this challenging class of proteins.

From Theory to Therapy: MD Methods Driving Drug Discovery

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful computational microscope, enabling researchers to study protein dynamics and conformational changes at atomic resolution. These conformational changes are often intimately connected to protein function and are critical targets for therapeutic intervention in drug discovery [29] [30]. However, simulating biologically relevant timescales with conventional MD remains challenging due to computational limitations. This has spurred the development of enhanced sampling methods and, more recently, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) approaches to more efficiently explore complex conformational landscapes [14]. This technical guide provides a comparative analysis of key methodological approaches for studying conformational changes in biological systems, with particular emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Methodological Approaches

| Method Category | Specific Approach | Key Principles | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path-Based Enhanced Sampling | Path Collective Variables (PCVs) with meta-eABF [29] | Defines a reaction coordinate (path) between known conformations; uses hybrid metadynamics/adaptive biasing force to enhance sampling along the path. | Large-scale conformational changes in proteins (e.g., allosteric modulation, activation) [29]. | Guides sampling along a biologically relevant pathway; can use all-atom representations. | Requires some a priori knowledge of the endpoints or path. |

| Biasing Potential Methods | Accelerated MD (aMD) [4] | Applies a non-negative bias potential to the true energy landscape, lowering energy barriers and accelerating transitions. | Exploring conformational landscapes without predefined coordinates; accessing hidden conformations [4]. | Does not require pre-defined Collective Variables; improves sampling of rare events. | The boost potential must be carefully selected to avoid distorting the landscape. |

| Ligand-Biased Sampling | Ligand-induced Biasing Force [31] | Applies a biasing force based on non-bonded interactions between a ligand and the protein. | Studying ligand-induced conformational changes, such as domain closure upon binding [31]. | Requires only a single input structure (no end state needed); no Collective Variables required. | At high bias values, may suppress important protein-protein interactions [31]. |

| AI & Deep Learning Integration | Deep Learning on MD Trajectories [32] | Uses convolutional neural networks to analyze inter-residue distance maps from MD trajectories and predict functional impacts of mutations. | Predicting effects of point mutations on infectivity and immune evasion (e.g., in SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein) [32]. | Efficiently identifies subtle, non-trivial conformational patterns; can predict binding affinity changes. | Dependent on quality and quantity of training data; limited interpretability of models [14]. |

| Hybrid AI-Structure Prediction | ML/MD Pipeline (e.g., trRosetta/AWSEM) [33] | Combines deep learning-based distance predictions from co-evolutionary data with physics-based force fields (AWSEM) for structure ensemble generation. | Investigating protein conformational ensembles; predicting multiple biologically relevant states [33]. | Can predict multiple conformations from sequence; leverages evolutionary information. | Hardware and data storage requirements can be intensive [33]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Path Collective Variable (PCV) Simulations with Meta-eABF

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating conformational changes in proteins of pharmaceutical interest, such as the STING protein and JAK2 pseudokinase domain [29].

A. System Preparation

- Initial Structures: Obtain starting protein structures from experimental data (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM) or computational predictions. For path-based methods, endpoint structures are beneficial.

- Solvation and Ions: Solvate the protein in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P-EW) using software such as GROMACS or AMBER. Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration [30].

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate all-atom force field (e.g., AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36) [30].

B. Path Collective Variable Construction

- Define the Path: Generate a minimum potential energy path (MPEP) connecting the initial and final conformational states. This can be achieved using a Smooth Anisotropic Network Model (SANM) [29].

- Refine with MD Frames: Refine the initial path using selected frames from all-atom MD simulations to create a more realistic all-atom PCV [29].

- Path Variables: Calculate the progress along the path (s) and the distance from the path (z) as the primary collective variables for the enhanced sampling simulation [29].

C. Enhanced Sampling Simulation (meta-eABF)