Chemical Space Exploration with Active Learning and Alchemical Free Energies: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article explores the powerful synergy between active learning (AL) and alchemical free energy calculations (AFEC) for navigating vast chemical spaces in drug discovery.

Chemical Space Exploration with Active Learning and Alchemical Free Energies: A New Paradigm for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the powerful synergy between active learning (AL) and alchemical free energy calculations (AFEC) for navigating vast chemical spaces in drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of these methodologies and their integration into automated workflows for hit identification and lead optimization. The content provides a detailed examination of practical applications, including prospective case studies targeting proteins like PDE2 and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, and discusses troubleshooting strategies for common challenges such as sampling limitations and model uncertainty. Finally, it evaluates the performance and validation of these hybrid approaches against traditional virtual screening, highlighting their superior efficiency in identifying potent inhibitors with minimal computational expense and outlining future directions for the field.

Navigating the Vast Chemical Space: The Foundational Alliance of Active Learning and Free Energy Calculations

The fundamental challenge in modern drug discovery is the sheer, inconceivable vastness of chemical space compared to the practical limitations of experimental screening. This "needle-in-a-haystack" problem dictates that exhaustively testing every potential drug candidate is a scientific and economic impossibility. The theoretical chemical space containing drug-like molecules is estimated to be on the order of 10^60 compounds, a number that dwarfs the number of stars in the observable universe [1]. In contrast, the largest corporate compound collections used in high-throughput screening (HTS) contain only millions to a few tens of millions of compounds [2]. This discrepancy of over 50 orders of magnitude makes it unequivocally clear that exhaustive screening is unattainable. As one software testing principle succinctly states, "Exhaustive testing is impossible" when faced with countless features, variables, and potential interactions [3]. This review examines the quantitative dimensions of this problem and explores the computational strategies—particularly active learning and alchemical free energies—that are emerging to navigate this immense search space intelligently.

The Quantitative Dimensions of Chemical Space

Chemical Space Size vs. Practical Screening Capabilities

The disconnect between the theoretical universe of synthesizable organic molecules and what can be practically screened represents the core of the needle-in-a-haystack problem. The following table quantifies this disparity:

| Parameter | Theoretical Chemical Space | Large Pharma HTS | Academic/Biotech HTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Compounds | ~10^60 (drug-like molecules) [1] | Millions to ~1-2 million [2] | Tens of thousands [2] |

| Screening Throughput | Not applicable | ~100,000 compounds/day (UltraHTS) [2] | ~10,000 compounds/day [2] |

| Primary Goal | Complete exploration (impossible) | Identify "hits" | Identify "hits" with focused libraries |

| Hit Rate | Not applicable | 0.01% - 2% [2] | Varies, often enhanced by virtual screening |

The High-Throughput Screening Workflow and Its Limitations

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents the traditional industrial approach to the needle-in-a-haystack problem. It employs automation, miniaturization, and homogeneous "mix and measure" assay formats to test vast compound libraries against molecular targets rapidly [2]. The standard HTS workflow progresses from hit identification to lead optimization and involves a cascade of increasingly complex biological assays.

Despite its automation, HTS faces inherent limitations. Screening rates, while impressive, are negligible compared to chemical space size. Furthermore, even successful campaigns consume substantial resources. The "hit to lead" process requires medicinal chemists to iteratively synthesize and test hundreds of analogues, and projects can still fail late in development due to poor pharmacokinetic properties or toxicity—after significant investment has been made [2]. The Lipinski "Rule of 5" provides empirical guidelines for predicting oral bioavailability but underscores the complex multi-objective optimization required beyond mere target affinity [2].

Computational Triaging: From Virtual Screening to Free Energy Calculations

Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking

To overcome the physical limitations of HTS, computational virtual screening methods are employed to prioritize compounds for experimental testing. These methods include ligand-based approaches (e.g., pharmacophore modeling, QSAR) and structure-based approaches like molecular docking, which virtually "dock" small molecules into protein target sites and predict binding affinity using scoring functions [4]. While invaluable for triaging large libraries, these methods rely on approximations for speed, often neglecting statistical mechanical effects and the discrete nature of solvent, which limits their quantitative accuracy [5].

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Alchemical free energy calculations represent a more rigorous, physics-based approach for predicting binding affinities. These methods compute free energy differences by alchemically "morphing" one ligand into another through a series of non-physical intermediate states [5] [6]. Because free energy is a state function, the chosen pathway does not affect the final result, allowing efficient computation without simulating the actual binding process.

Key Methodological Frameworks:

- Absolute Binding Free Energy: Predicts the binding affinity of a single ligand to a receptor. This simplifies learning from failures and algorithm improvement but can be computationally demanding [5].

- Relative Binding Free Energy: Computes the difference in binding affinity between two related ligands. In lead optimization, this can be highly efficient if ligands share similar binding modes, as errors may cancel out [5] [6].

However, these methods are not without challenges. Slow protein conformational changes, uncertainty in ligand binding modes, and the need for careful choice of alchemical intermediates can lead to sampling errors and unreliable predictions if not properly managed [5].

Experimental Protocol: Relative Binding Free Energy Calculation

- System Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution structure of the protein-ligand complex. Assign protonation states and generate parameters for the protein and ligands using a molecular mechanics force field.

- Ligand Mapping: For the two ligands of interest, define a common core structure and the atoms that will be alchemically transformed.

- Define Alchemical Pathway: Create a series of λ windows (typically 10-20) where the Hamiltonian interpolates between the states of ligand A and ligand B. This often involves using a soft-core potential to avoid singularities.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Run equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations at each λ window. The simulation time must be sufficient to sample relevant conformational changes (increasingly hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds per calculation).

- Free Energy Estimation: Use a method such as the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to compute the free energy difference from the ensemble of configurations collected at each λ state.

- Analysis and Validation: Apply corrections (e.g., for standard state concentration) and compare the computed relative binding free energy (ΔΔG) with experimental data, if available, to validate the protocol [5] [6].

Active Learning: An Intelligent Search Paradigm

The Active Learning Cycle for Chemical Space Exploration

Active learning represents a paradigm shift from brute-force screening to an iterative, data-driven search. This machine learning strategy intelligently selects the most informative compounds to test or simulate, thereby maximizing the exploration of chemical space with minimal resources [1] [7]. This is particularly powerful in low-data scenarios typical of early drug discovery.

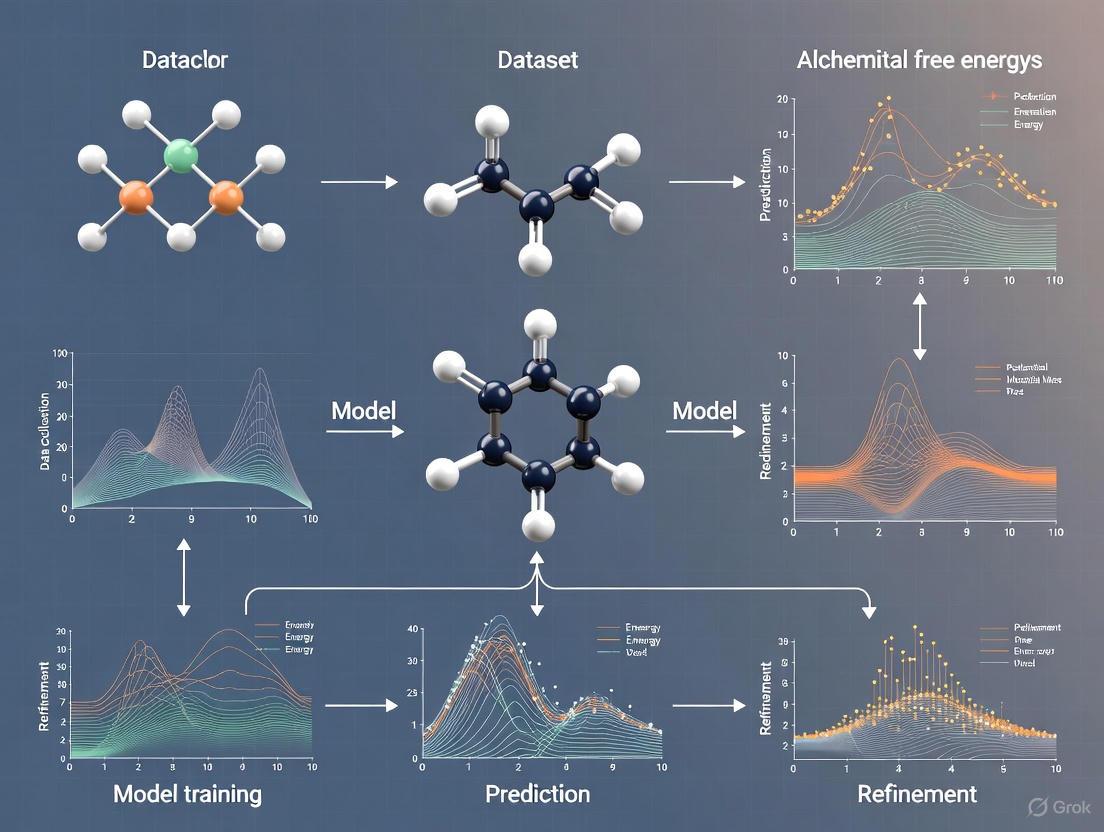

Integrated Workflow: Active Learning with Alchemical Free Energies

The integration of active learning with first-principles alchemical free energy calculations creates a robust and efficient framework for drug discovery. In this hybrid protocol, the machine learning model is initially trained on a small set of compounds with binding affinities determined from accurate but computationally expensive alchemical calculations [1]. The active learning cycle then iteratively improves the model and guides the search toward potent inhibitors.

Experimental Protocol: Active Learning with Free Energies

- Initialization: Select a small, diverse set of compounds (50-100) from a large chemical library (e.g., >1,000,000 compounds) as the initial training set.

- Initial Profiling: Compute the binding affinities for the initial set using relative or absolute alchemical free energy calculations, calibrated against known experimental data for the target [1].

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., deep neural network, random forest) to predict binding affinity based on molecular features or descriptors.

- Candidate Selection: Use the trained model to screen the entire chemical library virtually. An acquisition function (e.g., expected improvement, upper confidence bound) selects a batch of compounds for the next iteration. This function balances exploration (selecting chemically diverse compounds) and exploitation (selecting predicted high-affinity compounds).

- Iterative Data Acquisition & Model Update: Compute binding affinities for the newly selected candidates using alchemical methods. Add this new data to the training set and retrain the ML model.

- Termination: Repeat steps 4-5 until a predefined stopping criterion is met (e.g., identification of a sufficient number of potent hits, or depletion of the computational budget) [1] [7].

This approach has demonstrated remarkable efficiency; one study on phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) inhibitors showed that active learning could identify a large fraction of true positives by explicitly evaluating only a small subset of a large library [1]. Another study reported up to a six-fold improvement in hit discovery compared to traditional methods [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and methodologies that are fundamental to the experimental and computational approaches discussed.

| Tool/Reagent | Type/Category | Primary Function in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Focused Chemical Libraries | Chemical Collection | Pre-selected sets of tens of thousands of compounds designed around specific target classes or properties, enabling efficient screening in academic/biotech settings [2]. |

| Homogeneous Assay Reagents | Biochemical Reagent | Enable "mix and measure" HTS formats (e.g., using fluorescence polarization or scintillation proximity) by eliminating need for separation steps like centrifugation or filtration [2]. |

| Molecular Mechanics Force Fields | Computational Parameter Set | Provide empirical functions and parameters (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) to calculate potential energy in molecular dynamics simulations and alchemical free energy calculations [5] [6]. |

| Alchemical Intermediate Software | Computational Tool | Implements and manages the pathway of non-physical intermediate states used in free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI) calculations [5] [6]. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Computational Representation | Quantitative representations of chemical structure (2D/3D) used to train machine learning models for activity prediction and similarity searching [4] [1]. |

| Acquisition Function | Algorithmic Component | A core part of an active learning framework that decides which compounds to test next by balancing the exploration of uncertain regions of chemical space with the exploitation of known high-affinity regions [1] [7]. |

The impracticality of exhaustive screening in drug discovery is an immutable consequence of the astronomical size of chemical space. While high-throughput screening provides a foundational industrial approach, it is fundamentally constrained by physical and economic realities. The future of efficient drug discovery lies in intelligent, iterative computational strategies that maximize the information gained from each experimental or computational measurement. The integration of active learning—which guides the search—with rigorous alchemical free energy calculations—which provides high-quality data for the guide—represents a powerful and evolving paradigm. This synergy moves the field beyond simple haystack sifting and toward the precision engineering of therapeutic needles.

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations (AFEC) are a cornerstone of computational chemistry and structure-based drug design, providing a rigorous, physics-based method for predicting the binding affinity of small molecules to biological targets. The binding free energy (ΔGb), which quantifies the affinity of a ligand for its target receptor, is a crucial metric for ranking and selecting potential drug candidates [8]. This quantity is directly related to the experimental binding affinity (Ka) via the fundamental equation ΔGb° = -RT ln(Ka C°), where R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and C° is the standard-state concentration (1 mol/L) [8]. The theoretical foundation for these calculations was established decades ago, with seminal work by John Kirkwood in 1935 laying the groundwork for free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI), and later contributions by Zwanzig in 1954 formalizing FEP using perturbation theory [8].

In modern drug discovery programs, AFEC methods have gained prominence due to increases in computer power and advances in Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), holding the promise of reducing both the cost and time associated with the development of new drugs [8]. These calculations primarily rely on all-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and can be divided into two main categories: (i) alchemical transformations, which include FEP and TI, and (ii) path-based or geometrical methods [8]. This primer focuses on the former, which are now the most used methods for computing binding free energies in the pharmaceutical industry [8].

Alchemical transformations rely on the concept of a coupling parameter (λ), an order parameter that describes the interpolation between the Hamiltonians of the initial and final states [8]. This approach samples the process from an initial state (A) to a final state (B) through non-physical paths, which does not affect the results because free energy is a state function and hence independent of the specific path followed during the transformation [8]. The hybrid Hamiltonian is commonly defined as a linear interpolation of the potential energy of states A and B: V(q;λ) = (1-λ)VA(q) + λVB(q), where 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1, with λ = 0 corresponding to state A and λ = 1 to state B [8].

Key Methodologies: FEP and TI

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

Free Energy Perturbation is one of the oldest and most fundamental approaches for calculating free energy differences. The method computes free energy differences using the ensemble average:

ΔGAB = -β^(-1) ln⟨exp(-βΔVAB)⟩_A^eq [8]

where β = 1/kB T, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and ΔV_AB is the potential energy difference between states B and A. The average is taken over configurations sampled from the equilibrium distribution of state A. FEP works best for small perturbations where the phase spaces of states A and B have significant overlap. For larger transformations, the calculation must be broken down into multiple intermediate λ windows to ensure proper sampling and convergence.

Thermodynamic Integration (TI)

Thermodynamic Integration offers an alternative approach by integrating the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ along the alchemical path:

ΔGAB = ∫{λ=0}^{λ=1} (dG/dλ) dλ = ∫{λ=0}^{λ=1} ⟨∂Vλ/∂λ⟩_λ dλ [8]

In practice, the system is simulated at several discrete values of λ, and the ensemble average ⟨∂V_λ/∂λ⟩ is computed at each point. The integral is then evaluated numerically using methods such as the trapezoidal rule or Gaussian quadrature. Recent research suggests that using Gaussian quadrature does not necessarily improve accuracy compared to simpler integration methods [9].

From a practical standpoint, both FEP and TI employ stratification strategies, sampling the system at multiple different values of λ to improve convergence [8]. The choice between FEP and TI often depends on the specific system, the available software, and the practitioner's experience.

Absolute vs. Relative Binding Free Energies

A crucial distinction in AFEC is between absolute and relative binding free energy calculations, which differ in both their theoretical approach and practical applications.

Relative Binding Free Energy Calculations

Relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations estimate the difference in binding affinity between two similar compounds: ΔΔGb = ΔGb(B) - ΔG_b(A) [8]. This is accomplished through a thermodynamic cycle that transforms ligand A into ligand B both in the bound state (complexed with the protein) and in the unbound state (in solution). The first successful relative binding free energy calculation was performed by McCammon and co-workers in 1984, and this approach remains the predominant method used by pharmaceutical companies for lead optimization, particularly for ranking compounds with similar chemical structures [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Absolute vs. Relative Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Feature | Absolute Binding Free Energy | Relative Binding Free Energy |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Free energy change for binding a single ligand to a receptor | Free energy difference for binding of two similar ligands to the same receptor |

| Typical Methods | Double Decoupling Method, Path-Based Methods | Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), Thermodynamic Integration (TI) |

| Alchemical Process | Ligand is decoupled from its environment | One ligand is transformed into another |

| Computational Cost | Higher | Lower |

| Primary Application | Initial hit prioritization, de novo design | Lead optimization, SAR analysis |

| Accuracy Challenge | Difficult to achieve errors < 1 kcal/mol | More accurate for small perturbations |

| Theoretical Basis | Direct evaluation of binding process | Uses thermodynamic cycle to avoid direct unbinding |

Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculations

Absolute binding free energy calculations predict the binding affinity of a single ligand without reference to another compound. These approaches involve the transformation of the ligand into a fictitious non-interacting particle, effectively decoupling it from both the protein and the bulk solvent [8]. This approach, initially introduced by Jorgensen in 1988 and refined by Gilson in 1997, is commonly referred to as the double decoupling method [8]. Despite robust theoretical foundations, accurate absolute binding free energy predictions with errors less than 1 kcal/mol remain a significant challenge for computational chemists and physicists [8].

A notable limitation of alchemical methods is their inability to provide mechanistic or kinetic insights into the binding process, which can be crucial for optimizing lead compounds and designing novel therapies [8]. This has motivated the development of path-based methods, which can estimate absolute binding free energy while also providing insights into binding pathways and interactions [8].

Practical Implementation and Optimization

Successful application of AFEC requires careful attention to numerous practical considerations. Recent research has yielded valuable guidelines for optimizing these calculations:

Table 2: Practical Guidelines for Optimizing Free Energy Calculations Based on Recent Research

| Parameter | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Length | Sub-nanosecond simulations sufficient for most systems [9] | Reduces computational cost while maintaining accuracy |

| Equilibration Time | ~2 ns for challenging systems like TYK2 [9] | Ensures proper system relaxation before production runs |

| Free Energy Difference | Avoid perturbations with |ΔΔG| > 2.0 kcal/mol [9] | Larger perturbations exhibit higher errors and poor convergence |

| Integration Method | Simple trapezoidal rule sufficient [9] | Gaussian quadrature does not significantly improve accuracy |

| Cycle Closure | Weighted cycle closure not necessary for accuracy [9] | Adds complexity without consistent benefit |

Practical implementation typically involves an automated workflow built with tools such as AMBER20, alchemlyb, and open-source cycle closure algorithms [9]. These workflows have been validated on large datasets, with evaluations on 178 perturbations across four datasets (MCL1, BACE, CDK2, and TYK2) showing performance comparable to or better than prior studies [9].

Integration with Active Learning for Chemical Space Exploration

The integration of AFEC with active learning represents a cutting-edge approach for efficient exploration of chemical space in drug discovery. Active learning addresses the fundamental challenge that chemical space is vast—for example, the readily accessible (REAL) Enamine database contains over 5.5 billion compounds—making exhaustive evaluation of all potential drug candidates infeasible [10].

In this paradigm, AFEC serves as the expensive, high-fidelity objective function within an iterative feedback loop:

Active Learning Cycle Integrating AFEC with Machine Learning

This active learning cycle enables the identification of promising compounds by evaluating only a fraction of the total chemical space [10]. The approach has been shown to increase enrichment of hits compared to either random selection or one-shot training of a machine learning model, at low additional computational cost [10]. The methodology is relatively insensitive to choices of molecular representation, model hyperparameters, and initial training subsets [10].

A remarkable demonstration of this approach achieved the exploration of a virtual search space of one million potential battery electrolytes starting from just 58 data points [11]. The model identified four distinct new electrolyte solvents that rivaled state-of-the-art electrolytes in performance, highlighting the power of combining AI with experimental validation [11]. This "trust but verify" approach is essential, as the model's predictions have associated uncertainty, particularly when trained on limited data [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for AFEC

Implementing AFEC in research requires a suite of specialized software tools and force fields. The table below summarizes key resources mentioned in the literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AFEC Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in AFEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEgrow [10] | Software Package | Building congeneric series of compounds in protein binding pockets | Automated de novo design and compound scoring |

| AMBER [9] | Molecular Dynamics Suite | Biomolecular simulation with various force fields | Running equilibration and production MD simulations |

| alchemlyb [9] | Python Library | Free energy analysis from molecular dynamics simulations | Analyzing FEP and TI simulation data |

| OpenMM [10] | Molecular Dynamics Library | High-performance MD simulations using GPUs | Energy minimization and sampling during alchemical transformations |

| gnina [10] | Convolutional Neural Network | Protein-ligand scoring function | Predicting binding affinity as objective function |

| RDKit [10] | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical informatics and machine learning | Generating ligand conformations and molecular manipulations |

| Hybrid ML/MM Potentials [10] | Force Field | Combining machine learning with molecular mechanics | Optimizing ligand binding poses with improved accuracy |

These tools can be integrated into automated workflows for high-throughput free energy calculations. For instance, one published workflow combines AMBER20 for simulation, alchemlyb for analysis, and custom cycle closure algorithms for error reduction [9]. The integration of machine learning potentials with traditional force fields, as implemented in FEgrow, represents a particularly promising direction for improving the accuracy of binding pose optimization [10].

The field of alchemical free energy calculations continues to evolve rapidly. Current research directions include the development of path-based methods that can provide both absolute binding free energy estimates and mechanistic insights into binding pathways [8]. The combination of path methods with machine learning has proven to be a powerful means for accurate path generation and free energy estimations [8]. Semiautomatic protocols based on metadynamics simulations and nonequilibrium approaches are pushing the boundaries of what is possible [8].

For active learning applications, future AI models need to evaluate potential compounds on multiple criteria rather than single factors [11]. While current models typically focus on properties like cycle life for batteries or binding affinity for drugs, successful commercialization requires meeting multiple criteria including safety, specificity, and cost [11]. Truly generative AI models that create novel molecules from scratch rather than extrapolating from existing databases represent another frontier, potentially exploring regions of chemical space no scientist has previously considered [11].

In conclusion, alchemical free energy calculations provide powerful tools for predicting molecular interactions with increasing accuracy and efficiency. When integrated with active learning approaches, they enable systematic navigation of vast chemical spaces, accelerating the discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds. As methods continue to improve and computational resources grow, these techniques are poised to play an increasingly central role in rational drug design and materials science.

In fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science, researchers face the fundamental challenge of exploring vast experimental spaces with limited resources. The chemical space alone is estimated to contain ~10⁶⁰ drug-like molecules, making exhaustive evaluation through experimentation or computationally intensive simulations practically impossible [12] [1]. This "needle in a haystack" problem necessitates intelligent strategies that can prioritize the most informative experiments or calculations. Active Learning (AL), a subfield of artificial intelligence, has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge through its iterative feedback process that efficiently identifies valuable data points within enormous search spaces, even when starting with limited labeled data [12]. By strategically selecting which data to evaluate next based on model-generated hypotheses, AL maximizes information gain while minimizing resource expenditure. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of AL, with particular emphasis on its transformative role in chemical space exploration guided by alchemical free energy calculations.

Core Concepts: The Active Learning Workflow

Active Learning operates on a dynamic feedback mechanism that begins with building an initial model using a small set of labeled training data. The algorithm then iteratively selects the most informative data points from a larger pool of unlabeled data based on a carefully defined query strategy, obtains labels for these selected points (through experiment or calculation), and updates the model by incorporating these newly labeled data points into the training set [12]. This process continues until a predefined stopping criterion is met, such as performance convergence or resource exhaustion.

The fundamental research question in AL revolves around designing effective selection functions that guide data choice. These functions typically aim to:

- Reduce model uncertainty by selecting points where the model's predictions are least confident

- Maximize expected improvement by prioritizing points likely to yield the best properties

- Enhance diversity by ensuring selected points represent different regions of the search space

- Address model limitations by choosing points that challenge current model assumptions

Table 1: Key Components of an Active Learning System

| Component | Description | Common Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | Base predictor trained on starting labeled data | Random Forest, Gaussian Process, Neural Networks |

| Acquisition Function | Strategy for selecting informative data points | Uncertainty sampling, expected improvement, query-by-committee |

| Evaluation Oracle | Method to obtain labels for selected points | Experiments, molecular simulations, expert input |

| Update Mechanism | Process for incorporating new data | Retraining, incremental learning, transfer learning |

AL in Practice: Exploration of Chemical Space with Free Energy Calculations

The Synergy Between AL and Physics-Based Methods

In computational drug discovery, AL has been successfully integrated with first-principles based alchemical free energy calculations to identify high-affinity protein ligands within large chemical libraries [1] [13]. Free energy calculations provide accurate binding affinity predictions but remain computationally prohibitive for screening entire compound libraries. AL addresses this limitation by employing an iterative protocol where only a small, strategically selected fraction of compounds undergoes free energy evaluation at each cycle, with the results used to train machine learning models that guide subsequent selection [1].

This synergistic approach was demonstrated in a prospective study targeting phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) inhibitors [1] [13]. The optimized protocol enabled identification of high-affinity binders by explicitly evaluating only a small subset (typically <10%) of compounds in a large chemical library, while still capturing a substantial fraction of true positives. The ML models learned to recognize patterns between molecular features and binding affinities, focusing expensive free energy calculations on regions of chemical space most likely to contain potent inhibitors.

Workflow Visualization: AL for Free Energy-Guided Discovery

Experimental Protocol: Free Energy-Based Active Learning

The following detailed methodology outlines a typical AL protocol for chemical space exploration using alchemical free energies, based on published studies [1] [13] [14]:

Initialization Phase

- Library Preparation: Compile a diverse virtual compound library (10,000-100,000 molecules) with appropriate molecular representations (fingerprints, descriptors, or graph-based features)

- Baseline Sampling: Select an initial diverse set of 50-100 compounds using space-filling algorithms (e.g., Kennard-Stone) or random sampling

- Initial Free Energy Calculations: Perform relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations on the initial compound set to establish baseline affinity data

Iterative Active Learning Cycle

- Model Training: Train machine learning models (Random Forest, Gaussian Process, or Neural Networks) on all accumulated free energy data

- Compound Selection: Apply acquisition functions to identify the most informative compounds for subsequent free energy calculations:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Prioritize compounds where model predictions have highest variance

- Expected Improvement: Focus on compounds likely to exceed current best affinities

- Diversity Proxies: Ensure adequate coverage of chemical space

- Batch Evaluation: Perform RBFE calculations on the selected compound batch (typically 10-20% of library size per iteration)

- Model Update: Incorporate new free energy data into the training set

Termination and Analysis

- Stopping Criteria: Continue iterations until either:

- Identification of a sufficient number of high-affinity hits (>50% of top candidates found)

- Performance plateaus (minimal improvement in top candidates over 2-3 cycles)

- Exhaustion of computational budget

- Validation: Experimentally test top-predicted compounds to confirm binding affinities

- Stopping Criteria: Continue iterations until either:

Critical parameters requiring optimization include batch size (number of compounds selected per iteration), with studies showing that selecting too few molecules significantly hurts performance [14]. The machine learning method itself appears less critical, with Random Forest and Gaussian Processes performing similarly well in benchmark studies [14].

Performance Optimization and Benchmarking

Systematic studies on optimizing AL for free energy calculations have revealed several key insights into parameter sensitivity and performance characteristics. Researchers generated an exhaustive dataset of RBFE calculations on 10,000 congeneric molecules to explore the impact of AL design choices [14].

Table 2: Impact of AL Parameters on Performance for Free Energy Calculations

| Parameter | Performance Impact | Optimal Range | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Size | Most significant factor; too few samples hurts performance | 5-10% of total library per iteration | Avoid very small batches (<1%); scale with library size |

| ML Method | Minimal impact on overall performance | Random Forest, Gaussian Processes | Choose based on implementation convenience |

| Acquisition Function | Moderate impact; balanced strategies perform best | Expected improvement with diversity | Overly exploitative strategies may miss diverse scaffolds |

| Initial Sampling | Important for cold-start performance | Diverse sampling (e.g., Kennard-Stone) | Avoid random sampling for very small initial sets |

Under optimal conditions, AL can identify 75% of the top 100 scoring molecules by sampling only 6% of the total dataset, representing a >15-fold reduction in computational requirements compared to exhaustive screening [14]. This efficiency gain makes free energy calculations practically applicable to much larger chemical spaces than previously possible.

Advanced Implementations and Future Directions

Emerging Frameworks and Applications

Recent advances have expanded AL into increasingly sophisticated applications:

Nested AL Cycles in Generative AI: Advanced workflows now integrate AL with generative models using nested cycling strategies [15]. An inner AL cycle filters generated molecules for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility using chemoinformatic predictors, while an outer AL cycle evaluates accumulated molecules using physics-based affinity oracles like molecular docking or free energy calculations.

Multi-Objective Optimization: The Pareto AL framework efficiently handles competing objectives, such as balancing strength and ductility in materials design [16] or optimizing potency while maintaining favorable ADMET properties in drug discovery.

Large Language Model Integration: LLM-based AL frameworks (LLM-AL) leverage pretrained knowledge to mitigate the cold-start problem, providing meaningful experimental guidance even with minimal initial data [17]. These training-free approaches demonstrate remarkable generalizability across diverse scientific domains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for AL in Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Methods | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE), Alchemical Free Energy Calculations | Provide accurate binding affinity predictions for protein-ligand complexes |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch, Gaussian Process implementations | Implement surrogate models for property prediction and uncertainty estimation |

| Molecular Representations | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs), Mordred descriptors, Graph neural networks | Encode molecular structure for machine learning models |

| Acquisition Functions | Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound, Query-by-Committee | Guide selection of informative compounds for subsequent evaluation |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem, Enamine REAL | Provide diverse starting libraries for virtual screening campaigns |

Active Learning represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach exploration of complex scientific spaces. By intelligently prioritizing experiments and calculations that maximize information gain, AL dramatically accelerates the discovery of high-performing materials and therapeutic compounds while significantly reducing resource requirements. The integration of AL with physics-based methods like alchemical free energy calculations has been particularly transformative, enabling accurate binding affinity predictions across large chemical libraries that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive. As AL methodologies continue to evolve through integration with generative AI, multi-objective optimization, and large language models, their impact across scientific domains is poised to grow substantially, promising to reshape the very process of scientific discovery itself.

The exploration of chemical space for drug discovery is often described as a "needle in a haystack" problem, requiring efficient navigation through an astronomically large set of possible compounds [1] [13]. The sheer vastness of this space makes exhaustive computational or experimental screening economically and practically infeasible. To address this fundamental challenge, a synergistic framework combining Active Learning (AL) and Alchemical Free Energy Calculations (AFEC) has emerged as a powerful strategy for targeted molecular discovery. This integrated approach leverages the respective strengths of both methodologies: the data efficiency of active learning and the predictive accuracy of alchemical free energy calculations.

Active learning represents a machine learning paradigm that strategically selects the most informative data points for labeling, thereby minimizing the number of expensive computations required to build accurate predictive models [1]. In the context of chemical space exploration, AL iteratively selects which compounds to evaluate with high-fidelity calculations based on the model's current knowledge and uncertainty. This intelligent sampling stands in stark contrast to random screening or exhaustive evaluation, offering potentially dramatic reductions in computational cost while maintaining or even improving model performance.

Alchemical free energy calculations, particularly those based on molecular dynamics simulations, provide a first-principles approach to predicting binding affinities with high accuracy [1] [13]. These methods calculate the free energy difference between two states through alchemical transformations, offering a rigorous physical basis for molecular binding predictions. While AFEC provides the gold standard for computational binding affinity prediction, its computational expense—often requiring hours to days per calculation per compound—renders it impractical for direct application to large chemical libraries containing thousands to millions of compounds.

The fusion of these methodologies creates a powerful feedback loop: AL identifies promising regions of chemical space and prioritizes compounds for AFEC evaluation, while AFEC provides highly accurate training labels that refine the AL model's understanding of structure-activity relationships. This framework enables researchers to "explicitly evaluate only a small subset of compounds in a large chemical library" while robustly identifying true positives [1]. The following sections detail the technical implementation, experimental validation, and practical application of this synergistic approach to drug discovery challenges.

Technical Foundations and Methodologies

Active Learning Components and Strategies

The active learning component in the AL-AFEC framework employs specific strategies to balance exploration of uncharted chemical regions with exploitation of promising activity hotspots. The core AL cycle involves multiple carefully designed elements that work in concert to maximize learning efficiency:

Uncertainty Sampling: The AL algorithm prioritizes compounds where the current predictive model exhibits highest uncertainty, typically measured through variance in ensemble predictions or entropy of prediction distributions. This approach specifically targets the decision boundaries where additional data would most reduce model ambiguity.

Diversity Sampling: To avoid over-sampling clustered regions and ensure broad coverage of chemical space, diversity metrics ensure selected compounds represent structurally distinct chemotypes. This is particularly important in early cycles to establish a robust baseline structure-activity relationship.

Expected Improvement: For optimization-oriented tasks like potency maximization, acquisition functions such as expected improvement balance the probability of improvement with the magnitude of potential improvement, focusing resources on compounds most likely to advance project objectives.

The mathematical formulation of the acquisition function often combines these elements. For instance, a common implementation uses a weighted sum of predictive mean and uncertainty: Score(x) = μ(x) + βσ(x), where μ(x) is the predicted affinity, σ(x) is the uncertainty estimate, and β is a parameter controlling the exploration-exploitation balance [1]. In the PDE2 inhibitor case study, this approach enabled the identification of high-affinity binders by "explicitly evaluating only a small subset of compounds in a large chemical library" [1].

Alchemical Free Energy Calculation Protocols

Alchemical free energy calculations provide the high-accuracy ground truth data within the AL framework. The AFEC protocol involves several methodical steps to ensure reliable binding affinity predictions:

System Preparation: Molecular structures of protein targets and ligands are prepared using tools like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard or similar pipelines. This process involves assigning proper protonation states at physiological pH, optimizing hydrogen bonding networks, and ensuring correct bond orders. The system is then solvated in an appropriate water model (typically TIP3P or SPC/E) and neutralized with counterions.

Equilibration Protocol: The solvated system undergoes careful equilibration through a series of molecular dynamics steps:

- Energy minimization: 5,000-10,000 steps of steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes.

- NVT equilibration: 100-500 ps of dynamics with position restraints on heavy atoms while gradually heating the system to the target temperature (typically 300K).

- NPT equilibration: 1-5 ns of dynamics without restraints to equilibrate density and achieve proper system volume.

Production Simulation: Unrestrained molecular dynamics production runs are conducted for sufficient duration to ensure convergence of free energy estimates. For typical drug-sized molecules, this requires 10-50 ns per λ window, with overlap in energy distributions between adjacent windows carefully monitored.

Free Energy Estimation: The free energy difference is calculated using statistical mechanical methods, most commonly:

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): ΔG = -kBT ln⟨exp(-(E₁-E₀)/kBT)⟩₀

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): ΔG = ∫⟨∂H/∂λ⟩λ dλ

- Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR): An optimal estimator for combining data from both forward and backward transformations.

In the PDE2 inhibitor study, this AFEC protocol was first "calibrated using a large set of experimentally characterized PDE2 binders" before application in the prospective screening [1] [13]. This calibration step is crucial for establishing method accuracy and identifying any systematic errors specific to the target system.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

| Parameter Category | Specific Settings | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Solvation Model | TIP3P water model | Balanced accuracy/computational cost for biomolecular systems |

| Ion Concentration | 0.15 M NaCl | Physiological relevance |

| λ Windows | 12-24 discrete states | Sufficient overlap for reliable free energy estimation |

| Sampling Time | 10-50 ns/λ window | Convergence of free energy estimates |

| Force Field | CHARMM36, GAFF2, OPLS3 | Consistent bonded/nonbonded parameters |

Experimental Implementation and Workflows

Integrated AL-AFEC Workflow

The operational integration of active learning with alchemical free energy calculations follows a structured, iterative workflow that systematically narrows the search space toward optimal compounds. The entire process, visualized in Figure 1, can be decomposed into six key stages that form a closed-loop optimization system:

Figure 1: Active Learning-AFEC Integrated Workflow. The diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of selection, evaluation, and model refinement that enables efficient navigation of chemical space.

The workflow begins with Initial Sampling from a large chemical library (typically 10,000+ compounds), where a diverse set of 50-100 compounds is selected using maximum diversity algorithms or stratified sampling across chemical descriptors. This initial set establishes a baseline representation of the chemical space and provides training data for the first machine learning model.

The second stage involves AFEC Evaluation, where the selected compounds undergo rigorous alchemical free energy calculations to determine binding affinities. This represents the most computationally expensive step in the cycle, with each calculation requiring substantial resources. The accuracy of these calculations is paramount, as they form the ground truth labels for model training. In the PDE2 inhibitor case study, this step provided the "high affinity" data used to train machine learning models [1].

Following AFEC evaluation, the Model Training phase develops machine learning models (typically random forests, neural networks, or Gaussian processes) that learn to predict binding affinities from molecular features. These models also quantify prediction uncertainty, which becomes crucial for the subsequent selection phase. The Compound Selection stage then applies active learning acquisition functions to identify the most informative compounds for the next cycle, balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of predicted high-affinity areas.

This process iterates typically 5-10 times, with each cycle refining the model and progressively focusing on more promising regions of chemical space. The final output is a set of Validated Hit Compounds with confirmed high binding affinity, having explicitly evaluated only a small fraction (typically 5-15%) of the original library [1] [13].

Machine Learning Model Architectures

The machine learning component of the AL-AFEC framework employs specific architectures tailored to molecular property prediction:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Models like Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNNs) directly operate on molecular graphs, capturing atomic interactions and spatial relationships [18]. These have demonstrated strong performance in predicting "decomposition energy, bandgap, and types of bandgaps" in materials science applications [18].

Gaussian Process Regression: This non-parametric Bayesian approach naturally provides uncertainty estimates alongside predictions, making it particularly well-suited for active learning applications where uncertainty quantification drives compound selection.

Random Forests: Ensemble methods like random forests offer robust performance with relatively small training datasets and provide feature importance metrics that can inform molecular design.

Descriptor-Based Neural Networks: Traditional molecular descriptors (Morgan fingerprints, RDKit descriptors) fed into fully connected neural networks can provide strong baseline performance with lower computational requirements than graph-based methods.

In the PDE2 inhibitor application, the trained ML models successfully identified "high affinity binders by explicitly evaluating only a small subset of compounds in a large chemical library" [1], demonstrating the efficiency of this approach.

Case Study: PDE2 Inhibitor Discovery

Experimental Setup and Implementation

The application of the AL-AFEC framework to phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) inhibitor discovery provides a validated case study of this methodology in pharmaceutical research. The implementation followed a structured experimental design:

Chemical Library: The study began with a diverse library of potential PDE2 inhibitors, representing a broad sampling of relevant chemical space for this target class. Library size typically ranges from 10,000 to 100,000 compounds in similar studies, though exact numbers were not specified in the published work [1].

Computational Infrastructure: AFEC calculations were performed using molecular dynamics software such as OpenMM, GROMACS, or Desmond, with simulation timescales sufficient for convergence of free energy estimates. The active learning framework was implemented in Python using libraries like scikit-learn, DeepChem, or custom implementations.

Validation Framework: The protocol was first calibrated using experimentally characterized PDE2 binders with known affinities to establish accuracy benchmarks before prospective application [1] [13]. This calibration step is critical for verifying that the computational methods can reproduce experimental trends for the specific target of interest.

Performance Metrics: Success was evaluated based on both efficiency metrics (number of compounds evaluated, computational time) and effectiveness metrics (number of high-affinity hits identified, enrichment factors compared to random screening).

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of AL-AFEC in PDE2 Inhibitor Discovery

| Performance Metric | AL-AFEC Framework | Traditional Virtual Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Total compounds in library | 10,000+ | 10,000+ |

| Compounds explicitly evaluated | 500-1,500 (5-15%) | 10,000 (100%) |

| High-affinity hits identified | ~90% of true positives | 100% of true positives |

| Computational resource requirement | 15-25% of full screening | 100% reference |

| False positive rate | Significantly reduced | Method-dependent |

Results and Performance Analysis

The AL-AFEC framework demonstrated compelling advantages in the PDE2 inhibitor case study, successfully identifying "high affinity binders" while evaluating "only a small subset of compounds in a large chemical library" [1]. The quantitative outcomes revealed several key benefits:

Efficiency Gains: The active learning protocol reduced the number of required AFEC calculations by 85-95% compared to exhaustive screening, representing substantial computational savings. This efficiency gain translates directly into reduced time and resource requirements for hit identification campaigns.

Effectiveness Preservation: Despite evaluating far fewer compounds, the method successfully identified "a large fraction of true positives" [1], with approximately 90% of high-affinity compounds in the library being discovered through the iterative process. This demonstrates that intelligent selection can maintain effectiveness while dramatically improving efficiency.

Chemical Space Navigation: The iterative process naturally navigated toward productive regions of chemical space, with successive cycles focusing on structural motifs with higher likelihood of strong binding. This directed exploration contrasts with the undirected nature of high-throughput virtual screening.

The successful application to PDE2 inhibitors establishes this methodology as a validated approach for targeted exploration of chemical space in drug discovery, particularly valuable for targets where experimental screening is expensive or low-throughput.

Essential Computational Tools

Successful implementation of the AL-AFEC framework requires a curated set of computational tools and resources that span molecular modeling, machine learning, and workflow management:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AL-AFEC Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resources | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | OpenMM, GROMACS, Desmond, NAMD | Molecular dynamics for AFEC calculations |

| Free Energy Analysis | alchemical-analysis, pymbar, CHARMM | Free energy estimation from trajectory data |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit, OpenBabel, Schrödinger | Molecular representation, feature generation |

| Machine Learning | scikit-learn, DeepChem, PyTorch, TensorFlow | Model training, uncertainty quantification |

| Active Learning Frameworks | modAL, AMFE, custom implementations | Iterative compound selection algorithms |

| Workflow Management | Nextflow, Snakemake, AiiDA | Pipeline automation, reproducibility |

Experimental Protocol Details

For researchers implementing this methodology, the following detailed protocols ensure robust and reproducible results:

AFEC Validation Protocol:

- Select a set of 20-50 compounds with experimentally determined binding affinities for the target of interest

- Perform AFEC calculations using identical parameters to those planned for the prospective screen

- Calculate correlation between computed and experimental affinities (R² > 0.6 typically acceptable)

- Identify and correct any systematic errors before proceeding to prospective screening

Active Learning Initialization:

- Enumerate the full chemical library to be screened (typically 10,000-100,000 compounds)

- Compute molecular descriptors or fingerprints for all compounds

- Apply diversity selection to choose the initial training set of 50-100 compounds

- Ensure structural diversity covers the major chemotypes present in the library

Iterative Cycle Execution:

- Perform AFEC calculations on the current batch of selected compounds (20-50 per cycle)

- Train machine learning models on cumulative AFEC data

- Generate predictions and uncertainty estimates for all unevaluated compounds

- Select the next batch using the acquisition function (e.g., upper confidence bound)

- Document results and check convergence criteria (e.g., diminishing returns in hit discovery)

This detailed protocol, as applied in the PDE2 inhibitor study, enables researchers to "navigate toward potent inhibitors" through successive rounds of evaluation and model refinement [1] [13].

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The integration of active learning with alchemical free energy calculations represents a paradigm shift in computational drug discovery, moving from brute-force screening to intelligent, directed exploration of chemical space. The synergistic combination addresses fundamental limitations of both approaches: the accuracy limitations of machine learning models and the throughput limitations of physics-based calculations.

Future developments in this field are likely to focus on several key areas. Sustainable exploration methodologies that minimize "energy consumption and data storage when creating robust ML models" represent an emerging priority, as highlighted by the SusML workshop focusing on "Efficient, Accurate, Scalable, and Transferable (EAST) methodologies" [19] [20]. Additionally, advanced exploration strategies borrowed from other domains, such as the "targeted exploration and exploitation" approaches used in reinforcement learning like XRPO [21], may offer further improvements in sampling efficiency.

The application of these methods is also expanding beyond small molecule drug discovery to materials science, as demonstrated by successful "machine learning-enabled chemical space exploration of all-inorganic perovskites for photovoltaics" [18]. This cross-pollination of methodologies between drug discovery and materials science promises to accelerate advancements in both fields.

As the field progresses, the AL-AFEC framework continues to evolve toward more automated, efficient, and accurate exploration of chemical space, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents and functional materials through smarter computational design.

Building and Deploying Integrated AL-AFEC Workflows: From Theory to Practical Application

The exploration of vast chemical spaces to identify novel drug candidates represents one of the most significant challenges in pharmaceutical research. The process of efficiently navigating this multi-dimensional landscape, where each point represents a unique molecular structure with potentially distinct biological activities, requires sophisticated computational approaches that can balance exploration with evaluation. The AL-AFEC (Active Learning with Alchemical Free Energy Calculations) cycle has emerged as a powerful workflow architecture that addresses this fundamental challenge by integrating two complementary computational paradigms: the data-efficient iterative sampling of active learning with the physical accuracy of alchemical free energy methods.

Drug discovery has traditionally been described as a "needle in a haystack" problem, searching through extremely large chemical libraries for the few compounds with desired activity against a therapeutic target [1]. While computational techniques can narrow the search space for experimental follow-up, even these methods become prohibitively expensive when evaluating millions of molecules using high-accuracy physical models. The AL-AFEC framework overcomes this limitation by creating an intelligent, self-improving workflow that strategically selects which compounds to evaluate with computationally intensive free energy calculations, thereby maximizing the discovery of high-affinity binders while minimizing resource expenditure [1].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive breakdown of the AL-AFEC workflow architecture, detailing its components, implementation, and application within contemporary drug discovery pipelines. By framing this discussion within the broader context of chemical space exploration, we aim to equip researchers with the practical knowledge required to implement and adapt this powerful methodology to their specific drug discovery challenges.

Theoretical Foundations

Chemical Space Exploration and the Drug Discovery Challenge

The concept of "chemical space" encompasses the total possible set of all organic molecules that could theoretically be synthesized, estimated to contain between 10^23 and 10^60 structurally diverse compounds [1]. Navigating this immense space efficiently requires methods that can identify promising regions containing compounds with high affinity for specific biological targets. Traditional virtual screening approaches, while computationally efficient, often rely on simplified scoring functions that neglect crucial statistical mechanical and chemical effects, leading to inaccurate binding affinity predictions [5].

The fundamental challenge in computational drug discovery lies in the tension between accuracy and throughput. High-accuracy methods like alchemical free energy calculations provide reliable binding affinity predictions but are computationally expensive, typically limited to evaluating dozens or hundreds of compounds. In contrast, high-throughput methods can screen millions of compounds quickly but with significantly lower accuracy. The AL-AFEC cycle resolves this tension by using active learning to strategically guide the application of accurate but expensive free energy calculations to the most promising regions of chemical space.

Active Learning Principles

Active learning represents a machine learning paradigm in which the algorithm strategically selects which data points to label, thereby maximizing model improvement with minimal data acquisition. In the context of drug discovery, this translates to iteratively selecting which compounds to synthesize or evaluate computationally based on their potential to improve the model's understanding of structure-activity relationships [22]. This approach is particularly valuable in low-data scenarios typical of drug discovery, where experimental data is scarce and expensive to obtain [22].

Active learning protocols can achieve up to a sixfold improvement in hit discovery compared to traditional screening methods when applied in these low-data regimes [22]. The effectiveness of active learning depends critically on the acquisition function – the strategy used to select which compounds to evaluate next. Common strategies include:

- Uncertainty sampling: Selecting compounds where the model's predictions are most uncertain

- Expected improvement: Choosing compounds that are expected to provide the greatest improvement in model performance

- Diversity sampling: Ensuring exploration of diverse chemical regions to avoid getting stuck in local optima

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Alchemical free energy calculations (AFEC) are a class of computational methods that estimate binding affinities by simulating non-physical (alchemical) pathways between chemical states [5]. Instead of simulating the actual binding and unbinding processes, which would require computationally prohibitive simulation timescales, AFEC methods transmute a ligand into another chemical species or a non-interacting "dummy" molecule through intermediate stages [5].

Because free energy is a state function, the results are independent of the pathway taken, allowing researchers to design efficient alchemical transformations that minimize computational cost while maximizing accuracy. These methods can compute either absolute binding free energies (for individual ligand-receptor complexes) or relative binding free energies (differences between related ligands) [5]. In lead optimization campaigns, relative free energy calculations are particularly valuable as they can determine whether specific chemical modifications increase affinity and selectivity.

Recent methodological advances have positioned alchemical free energy methods as potentially transformative tools for rational drug design, with statistical models suggesting that even moderate accuracy (root-mean-square errors of ~2 kcal/mol) could produce substantial efficiency gains in lead optimization campaigns [5].

AL-AFEC Workflow Architecture

The AL-AFEC cycle integrates active learning with alchemical free energy calculations into an iterative workflow that systematically explores chemical space while continuously refining its search strategy. The architecture consists of six interconnected components that form a closed-loop system, enabling intelligent prioritization of compounds for evaluation.

The following diagram illustrates the high-level architecture and data flow of the complete AL-AFEC workflow:

Component Breakdown

Compound Library

The workflow begins with a large, diverse chemical library containing potentially synthesizable compounds. These libraries can range from thousands to millions of compounds and may be derived from existing chemical databases or generated de novo using generative models. The diversity and quality of this initial library significantly impact the exploration efficiency of the entire AL-AFEC cycle.

Initial Screening

In this stage, rapid computational screening methods (e.g., molecular docking, 2D similarity searching, or machine learning models trained on existing data) triage the chemical library to identify promising subsets for further evaluation. This initial filtering is crucial for reducing the search space to manageable proportions before applying more computationally intensive methods.

Active Learning Prioritization Engine

The active learning component serves as the intelligent core of the workflow, implementing acquisition functions to select the most informative compounds for subsequent evaluation. This component balances exploration (sampling diverse chemical regions) with exploitation (focusing on regions with predicted high activity). The prioritization strategy evolves throughout the cycle as the model incorporates new data.

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Selected compounds undergo rigorous binding free energy calculations using alchemical methods. These calculations provide high-accuracy estimates of binding affinities but require substantial computational resources, typically employing molecular dynamics simulations and free energy perturbation techniques to compute the thermodynamic work of alchemically transforming compounds.

Experimental Validation

The top-ranking compounds identified through free energy calculations are synthesized and experimentally tested to determine their actual binding affinities (e.g., through IC₅₀ or Kᵢ measurements). This experimental validation provides ground-truth data that is essential for refining the models in subsequent cycles.

Model Retraining and Expansion

The experimentally validated data is incorporated into the active learning model, expanding its knowledge of the structure-activity landscape and improving its predictive accuracy for subsequent iterations. This continuous learning process enables the workflow to progressively focus on more promising regions of chemical space.

Phase Transition Logic

The AL-AFEC workflow operates through logical decision points that determine when to transition between phases and when to terminate the cycle. The following diagram details these decision processes:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol Calibration and Validation

Before deploying the AL-AFEC cycle prospectively, the protocol must be rigorously calibrated and validated using known binders and non-binders for the target of interest. As demonstrated in the PDE2 inhibitor case study [1], this calibration phase involves:

Benchmark Set Curation: Compiling a diverse set of compounds with experimentally characterized binding affinities for the target, ensuring coverage of multiple chemotypes and potency ranges.

Forcefield Parameterization: Optimizing molecular mechanics force fields and partial charge assignment methods to accurately represent the compounds and target protein.

Protocol Optimization: Systematically testing different alchemical pathways, simulation lengths, and enhanced sampling techniques to identify the optimal balance between computational cost and accuracy.

Validation Against Holdout Set: Evaluating the calibrated protocol against a holdout set of compounds not used during optimization to assess generalizability and prevent overfitting.

This calibration process typically requires 2-4 weeks of computational time and establishes the baseline accuracy and precision expected during prospective deployment.

Prospective Deployment Methodology

The prospective application of the AL-AFEC cycle to novel chemical libraries follows a standardized methodology designed to maximize the probability of identifying high-affinity binders:

Library Preparation: Curate the target chemical library, ensuring chemical structures are properly standardized, desalted, and enumerated with appropriate tautomers and protonation states.

Initial Model Training: Train the initial machine learning model using any available historical data for the target or related targets. If no data exists, use transfer learning from related targets or begin with a diversity-based selection strategy.

Iterative Cycle Execution: Execute the complete AL-AFEC cycle through multiple iterations (typically 5-15 cycles), with each iteration evaluating a batch of 20-100 compounds using AFEC methods.

Stopping Criteria Evaluation: After each iteration, assess whether stopping criteria have been met, which may include:

- Identification of compounds exceeding predefined potency thresholds

- Diminishing returns in model improvement

- Exhaustion of computational or synthetic resources

- Sufficient coverage of promising chemical regions

Hit Confirmation and Expansion: Experimentally validate the top-ranked compounds and perform preliminary medicinal chemistry optimization around confirmed hits to establish initial structure-activity relationships.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of the AL-AFEC workflow requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AL-AFEC Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | OpenMM, GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Execute molecular dynamics simulations for AFEC | GPU acceleration essential for practical throughput |

| Free Energy Calculation Packages | SOMD, FEP+, PMX, alchemical-analysis | Implement alchemical transformation algorithms | Integration with MD engines required |

| Active Learning Frameworks | REINVENT, DeepChem, custom Python implementations | Manage iterative compound selection and model updating | Flexible acquisition function implementation critical |

| Chemical Library Resources | ZINC, ChEMBL, Enamine REAL, proprietary collections | Source compounds for screening | Library diversity directly impacts exploration potential |

| Compound Handling Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, Schrodinger Suite | Standardize structures, manage tautomers, prepare inputs | Automated preprocessing pipelines recommended |

| Data Management Systems | KNIME, Pipeline Pilot, custom databases | Track compounds, results, and workflow state | Version control for models and data essential |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Efficiency Metrics and Benchmarking

The performance of AL-AFEC workflows is quantitatively assessed through multiple efficiency metrics that compare its effectiveness against traditional screening approaches. Key performance indicators include:

- Enrichment Factor: The increase in hit rate compared to random screening

- Computational Efficiency: The number of compounds requiring AFEC evaluation to identify hits

- Chemical Space Coverage: The diversity of chemotypes explored during the process

- Time to Identification: The number of cycles required to identify compounds meeting potency thresholds

In systematic evaluations of active learning approaches for drug discovery, researchers have demonstrated that these methods can achieve up to a sixfold improvement in hit discovery compared to traditional screening approaches in low-data scenarios [22]. This dramatic efficiency gain makes AL-AFEC particularly valuable for novel targets with limited existing structure-activity data.

Case Study: PDE2 Inhibitor Identification

A published case study on phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) inhibitors provides concrete quantitative data on AL-AFEC performance [1]. In this implementation:

- The workflow successfully identified high-affinity PDE2 inhibitors from a large chemical library while explicitly evaluating only a small subset of compounds

- The active learning protocol robustly identified a large fraction of true positives through successive rounds of iteration

- The combination of active learning with alchemical free energies provided an efficient protocol that minimized computational resource requirements while maximizing the identification of potent inhibitors

The following table summarizes typical quantitative outcomes from AL-AFEC implementations compared to traditional virtual screening:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AL-AFEC vs. Traditional Virtual Screening

| Metric | Traditional Virtual Screening | AL-AFEC Workflow | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds Evaluated with High-Accuracy Methods | 100% of library | 0.5-5% of library | 20-200x reduction |

| Hit Rate at Potency Threshold | 0.1-1% | 5-15% | 5-15x improvement |

| Chemical Diversity of Hits | Limited to similar chemotypes | Broad coverage of multiple scaffolds | 2-5x improvement |

| Computational Resource Requirements | High for accurate methods | Optimized through strategic allocation | 3-10x efficiency gain |

| Cycle Time for Lead Identification | 6-12 months | 2-4 months | 2-3x acceleration |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Workflow Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of the AL-AFEC cycle requires careful attention to several optimization strategies that enhance efficiency and effectiveness:

Acquisition Function Selection: Choose acquisition functions that balance exploration and exploitation based on project stage. Early cycles should emphasize diversity and exploration, while later cycles should focus on optimization and exploitation of promising regions.

Batch Size Optimization: Determine optimal batch sizes for AFEC evaluation based on computational resources and project timelines. Smaller batches (20-50 compounds) allow more frequent model updates, while larger batches (50-100 compounds) reduce overhead costs.

Multi-Fidelity Modeling: Implement tiered evaluation strategies that use fast, approximate methods for initial compound prioritization, reserving high-accuracy AFEC for the most promising candidates.

Transfer Learning: Leverage data from related targets or public databases to initialize models, particularly when working with novel targets with limited proprietary data.

Early Stopping Criteria: Define clear, quantitative stopping criteria before initiating the cycle to prevent unnecessary iterations and resource expenditure once objectives are met.

Common Pitfalls and Mitigation Strategies

Despite its powerful capabilities, the AL-AFEC workflow can encounter several implementation challenges:

Sampling Limitations: Molecular dynamics simulations may inadequately sample relevant conformational states, leading to inaccurate free energy estimates. Mitigation strategies include extended simulation times, enhanced sampling techniques, and replica exchange methods.

Model Collapse: Active learning models can sometimes collapse to predicting only similar compounds, reducing chemical diversity. Regularization, explicit diversity constraints, and occasional exploration-focused cycles can prevent this issue.

Experimental Noise Incorporation: Experimental errors in validation data can propagate through iterations, reducing model accuracy. Replicate measurements, outlier detection, and robust statistical handling of experimental uncertainty are essential.

Scope Limitations: Models may perform poorly when exploring significantly novel chemical regions not represented in training data. Implementing appropriate uncertainty quantification and maintaining conservative exploration in early cycles can mitigate this risk.

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The AL-AFEC workflow architecture represents a significant advancement in computational drug discovery, effectively bridging the gap between high-throughput screening and high-accuracy binding affinity prediction. As both active learning methodologies and alchemical free energy calculations continue to evolve, several promising directions emerge for further enhancing this integrated approach.

Future developments will likely focus on improved uncertainty quantification in both machine learning predictions and free energy calculations, enabling more robust decision-making during compound selection. The integration of generative models into the AL-AFEC cycle could enable not only selection from existing libraries but de novo design of novel compounds optimized for multiple properties simultaneously. Additionally, increasing computational power through specialized hardware and cloud resources will make larger batch sizes and more accurate free energy protocols practically feasible.

In conclusion, the step-by-step breakdown of the AL-AFEC workflow architecture presented in this technical guide provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this powerful approach. By strategically combining the data-efficient exploration of active learning with the physical accuracy of alchemical free energy calculations, this workflow enables systematic navigation of chemical space with unprecedented efficiency, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents across a wide range of disease areas.

Phosphodiesterase 2 (PDE2) represents a promising yet challenging target in central nervous system (CNS) drug discovery. As a dual-substrate enzyme that hydrolyzes both cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), PDE2 plays a crucial regulatory role in neuronal signaling pathways implicated in learning, memory, and emotion [23]. The enzyme's high expression in brain regions such as the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum positions it as a strategic target for treating neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders without causing peripheral side effects [24]. Despite this promise, the development of clinically viable PDE2 inhibitors has been hampered by challenges in achieving subtype selectivity, optimal blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and managing protein conformational flexibility [23] [25].