Computational Chemistry in Drug Design: Accelerating Discovery from Target to Clinic

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of computational chemistry in modern drug discovery, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Computational Chemistry in Drug Design: Accelerating Discovery from Target to Clinic

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the transformative role of computational chemistry in modern drug discovery, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. The article covers foundational principles of computer-aided drug design (CADD), detailed methodologies including structure-based and ligand-based approaches, troubleshooting for common computational challenges, and validation through real-world case studies. By synthesizing current literature and emerging trends, we demonstrate how computational techniques dramatically reduce development timelines and costs while improving success rates, with particular focus on the integration of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and multiscale modeling approaches that are reshaping pharmaceutical research paradigms.

The Computational Revolution in Drug Discovery: Core Principles and Historical Evolution

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) represents a transformative force in modern pharmaceuticals, constituting a multidisciplinary field that integrates computational chemistry, biology, and informatics to rationalize and accelerate drug discovery [1]. CADD employs computational methods to simulate drug-target interactions, predicting molecular behavior, binding affinity, and pharmacological properties before synthetic efforts commence [2]. The core premise of CADD is the application of computer algorithms to chemical and biological data to understand and predict how drug molecules interact with biological targets, typically proteins or nucleic acids, within a biological system [1] [3].

The historical evolution of CADD parallels advancements in structural biology and computational power, transitioning drug discovery from serendipitous findings and trial-and-error approaches to a targeted, rational process [1] [4]. Early successes like the anti-influenza drug Zanamivir demonstrated CADD's potential to significantly truncate drug discovery timelines [1] [4]. CADD methodologies are broadly categorized into two complementary approaches: Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD), which leverages three-dimensional structural information of biological targets, and Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD), which utilizes knowledge of known active compounds [1] [3] [2]. This methodological framework enables researchers to minimize extensive chemical synthesis and biological testing by focusing computational resources on the most promising candidates, thereby reducing costs and development cycles [2] [5].

Key Methodological Frameworks and Computational Approaches

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD relies on knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the biological target, obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy, or through computational techniques like homology modeling when experimental structures are unavailable [3] [6]. The foundational steps of SBDD involve target structure preparation, binding site identification, and molecular docking to predict how small molecules interact with the target [5].

Molecular Docking is a cornerstone SBDD technique that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) within a target's binding site [1]. Docking algorithms sample possible conformational states of the ligand-protein complex and employ scoring functions to rank these poses based on estimated binding energy [1]. Virtual Screening (VS) extends this concept by computationally evaluating massive libraries of compounds (often millions) to identify potential hits, dramatically increasing screening efficiency compared to traditional high-throughput physical screening [1] [3].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations provide a dynamic view of biomolecular systems by calculating the time-dependent behavior of proteins and ligands, capturing conformational changes, binding pathways, and stability interactions that static structures cannot reveal [1] [3]. MD simulations, performed with software like GROMACS, NAMD, CHARMM, and AMBER, are crucial for understanding the flexibility and thermodynamic properties influencing drug binding [1] [3].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

When three-dimensional structural information of the biological target is unavailable, LBDD approaches provide powerful alternatives by exploiting knowledge derived from known active ligands [3] [2]. The fundamental hypothesis underpinning LBDD is that similar molecules often exhibit similar biological activities [6].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling establishes statistical correlations between quantitatively described molecular structures (descriptors) and their biological activities [1] [4]. Once a reliable QSAR model is developed and validated, it can predict the activity of novel compounds, guiding the optimization of lead compounds by suggesting structural modifications likely to enhance potency [1] [4].

Pharmacophore Modeling entails identifying the essential molecular features and their spatial arrangements necessary for biological activity [3] [5]. A pharmacophore model typically includes features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups, and aromatic rings. This model serves as a three-dimensional query for virtual screening of compound databases to retrieve new chemical entities possessing the critical features required for binding [5].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols in CADD

Protocol for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for identifying novel hit compounds through structure-based virtual screening, suitable for implementation by computational researchers and drug discovery scientists.

- Objective: To identify potential small-molecule inhibitors of a target protein from a large commercial or in-house compound library.

- Prerequisites: Three-dimensional structure of the target protein (from PDB or homology modeling) and a database of small molecules in 3D format (e.g., ZINC, Enamine).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or via homology modeling using tools like SWISS-MODEL or MODELLER [3] [5].

- Using molecular modeling software (e.g., Schrödinger Maestro, Discovery Studio), add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states for ionizable residues (Asp, Glu, His, Lys), and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

- Perform energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and geometric strain using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER).

Binding Site Identification and Grid Generation:

- Define the binding site coordinates based on known co-crystallized ligands or using cavity detection programs like CASTp or Q-SiteFinder [5].

- Generate a grid box encompassing the binding site to define the search space for docking algorithms. The box should be large enough to accommodate diverse ligands.

Ligand Database Preparation:

- Download or curate a database of compounds (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house library) [3].

- Prepare ligands by generating likely tautomeric states and protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., pH 7.4 ± 0.5).

- Generate multiple low-energy 3D conformations for each ligand to account for flexibility.

Molecular Docking and Virtual Screening:

- Select a docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD, DOCK) and configure its parameters [1] [3].

- Execute the virtual screening job, which docks each compound from the prepared library into the target's binding site.

- Collect the top-ranked compounds based on the docking score (estimated binding affinity).

Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Selection:

- Visually inspect the predicted binding modes of the top-scoring compounds. Prioritize those forming key interactions with the target (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges).

- Cluster hits based on chemical scaffolds to ensure structural diversity.

- Apply additional filters based on drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and synthetic accessibility.

Experimental Validation:

- Procure or synthesize the selected hit compounds.

- Subject them to in vitro biological assays to experimentally confirm binding affinity and functional activity.

Protocol for 3D-QSAR Model Development

This protocol describes the creation and validation of a 3D-QSAR model for lead optimization, a core technique in ligand-based drug design.

- Objective: To develop a predictive 3D-QSAR model that correlates the three-dimensional molecular fields of a congeneric series of compounds with their biological activity.

- Prerequisites: A set of 20+ compounds with known, quantitative biological activity values (e.g., IC50, Ki) measured in the same assay.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Data Set Compilation and Curation:

- Collect structures and corresponding biological activities for a series of analogous compounds.

- Divide the data set into a training set (~70-80%) for model generation and a test set (~20-30%) for external validation.

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Alignment:

- Build 3D molecular models of all compounds.

- Identify a common core structure (scaffold) shared by all molecules.

- For each compound, generate a low-energy conformation believed to be the bioactive conformation. A common method is to align all compounds to the structure of a known high-affinity ligand.

Molecular Field Calculation:

- Place each aligned molecule within a 3D grid.

- Calculate interaction energies between a probe atom and each molecule at every grid point. Typical probes include:

- A steric probe (e.g., an sp³ carbon atom) to map van der Waals interactions.

- An electrostatic probe (e.g., a proton) to map Coulombic potentials.

- Software like CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis) or CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) within packages like SYBYL is typically used.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis:

- The calculated steric and electrostatic field values for the training set molecules serve as independent variables (X), and the biological activity data serve as dependent variables (Y).

- PLS regression is used to derive the 3D-QSAR model, which relates the molecular field variations to the observed biological activity.

Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Assess the model's predictive power for the training set using cross-validation techniques (e.g., leave-one-out). The key metric is the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²), which should typically be >0.5.

- External Validation: Use the model to predict the activities of the test set molecules, which were not used in model building. The predictive correlation coefficient (r²_pred) should be >0.6.

Model Interpretation and Application:

- Visualize the 3D-QSAR coefficients as contour maps around representative molecules.

- Green contours indicate regions where increased steric bulk is favorable for activity; red contours indicate unfavorable regions.

- Blue contours indicate regions where positive charge is favorable; red contours indicate where negative charge is favorable.

- Use these maps to guide the design of new analogs with predicted higher potency.

- Visualize the 3D-QSAR coefficients as contour maps around representative molecules.

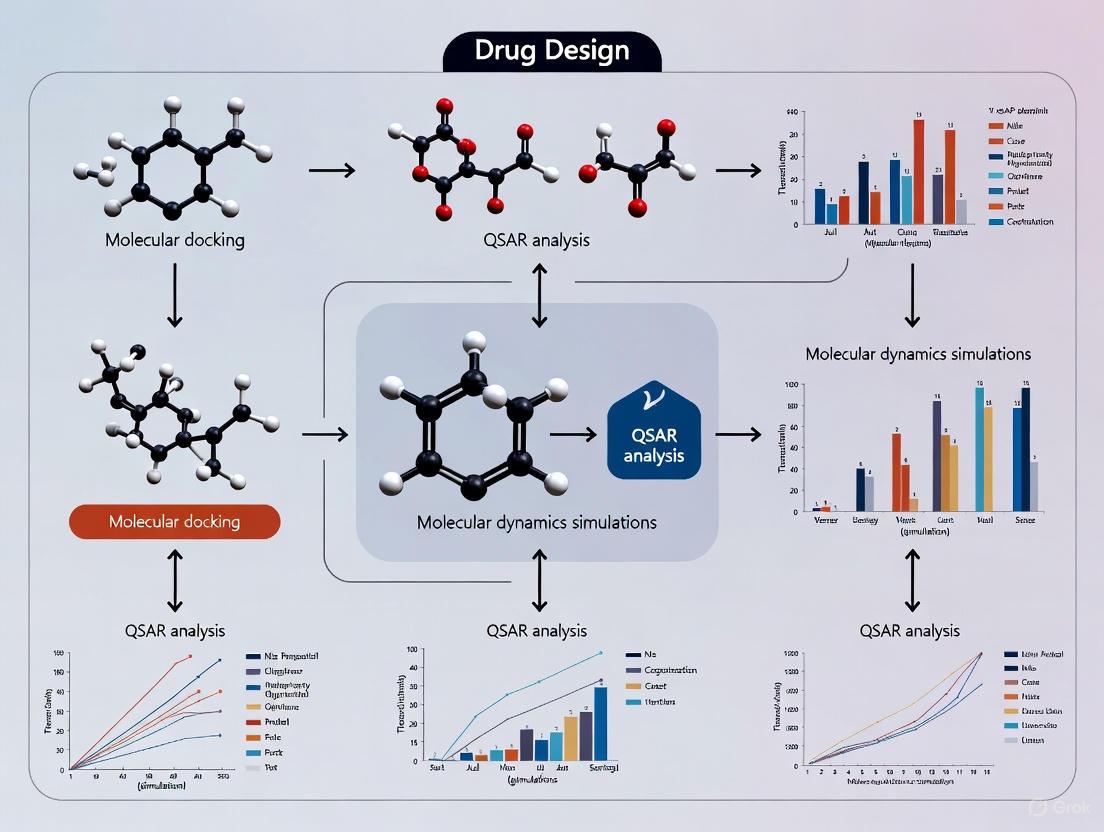

Visualization of CADD Workflows

CADD Methodology Pathway

Molecular Docking Process

The following table details key resources required for executing CADD protocols, encompassing software, databases, and computational tools.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for CADD

| Category | Resource Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling & Dynamics | GROMACS, NAMD, CHARMM, AMBER [1] [3] | Performs molecular dynamics simulations to study protein-ligand complex stability, conformational changes, and free energy calculations. |

| Homology Modeling | SWISS-MODEL, MODELLER, I-TASSER [1] [3] [5] | Predicts the 3D structure of a target protein based on the known structure of a homologous template protein. |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock Vina, Glide (Schrödinger), GOLD, DOCK [1] [3] [5] | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule ligand within a protein's binding site. |

| Virtual Screening | DOCK, Pharmer, ZINCPharmer [1] [3] [5] | Rapidly screens large virtual compound libraries to identify potential hits that bind to a biological target. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout, Phase (Schrödinger) [5] | Identifies and models the essential 3D features responsible for a ligand's biological activity, used for database searching. |

| QSAR Analysis | Various open-source and commercial packages (e.g., in KNIME, Python/R libraries) | Develops statistical models linking chemical structure descriptors to biological activity for predictive design. |

| Compound Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem [3] [5] | Provides access to millions of commercially available or bioactive compounds for virtual screening and lead discovery. |

| Protein Data Bank | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3] | Central repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies. |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, CGenFF [3] | Provides the mathematical functions and parameters needed to calculate the potential energy of a molecular system for simulations. |

| ADMET Prediction | admetSAR, QikProp, SwissADME [5] | Predicts absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties of drug candidates in silico. |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The trajectory of CADD is marked by rapid integration with emerging technologies. The confluence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is substantially amplifying predictive capabilities in target identification, molecular generation, and property prediction [1] [7] [8]. Deep learning models, particularly AlphaFold2 and its successors, have revolutionized protein structure prediction, providing high-accuracy models for targets with previously unknown structures [1] [7]. Furthermore, quantum computing holds future promise for solving intricate molecular simulations and optimization problems currently intractable for classical computers [7].

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. Ensuring predictive accuracy, addressing biases in AI/ML models, incorporating sustainability metrics, and developing robust ethical frameworks remain critical frontiers [1] [8]. The field must also navigate the "hype cycle" associated with new methodologies, emphasizing proper validation, education, and collaborative efforts to translate computational predictions into clinically successful therapeutics [8]. As CADD continues to evolve, its synergy with experimental validation will be paramount in shaping a more efficient, cost-effective, and innovative future for drug discovery, ultimately bridging the realms of biology and technology to deliver novel therapeutic solutions [1] [2].

The field of computational chemistry has undergone a revolutionary transformation in its application to drug design research, evolving from foundational physics-based molecular mechanics to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-driven discovery platforms. This paradigm shift has fundamentally redefined the entire pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) workflow, enabling unprecedented acceleration in identifying therapeutic targets, generating novel molecular entities, and optimizing lead compounds. Where traditional computational approaches operated within constrained parameters and limited datasets, modern AI systems integrate multimodal biological data to model disease complexity with holistic precision [9]. This article traces critical historical milestones in this evolution, provides detailed experimental protocols for key methodologies, and presents quantitative analyses of performance metrics that demonstrate the dramatic efficiency gains achieved in computational drug discovery. By examining both the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of these technologies, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive insights into the current state and future trajectory of computational chemistry in pharmaceutical sciences.

Historical Evolution of Computational Methods

The journey from molecular mechanics to AI-driven discovery represents a series of conceptual and technological breakthroughs that have progressively expanded our capacity to explore chemical space and predict biological activity.

Foundations in Molecular Mechanics and Structure-Based Design

The theoretical foundations of computational drug discovery were established with the development of molecular mechanics approaches based on classical Newtonian physics. These methods employ force fields to calculate the potential energy of molecular systems by accounting for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, and non-bonded interactions [10]. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for "the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems" recognized the fundamental importance of these computational approaches [10]. Structure-based drug design emerged as a dominant paradigm, relying on known three-dimensional structures of target proteins obtained through X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or homology modeling [10]. These structures enabled virtual screening of compound libraries through molecular docking, where computational algorithms predict how small molecules bind to protein targets and estimate binding affinity [10].

Traditional computer-aided drug design (CADD) encompassed ligand-based, structure-based, and systems-based approaches that provided a rational framework for hit finding and lead optimization [11]. These tools excelled at exploring how candidate molecules might interact with specific targets but were inherently limited by library size, scoring biases, and a narrow view of biological context [11]. The quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) paradigm, developed as a ligand-based approach, established statistical correlations between molecular descriptors and biological activity to guide chemical optimization [10] [12]. While these methods represented significant advances over purely empirical approaches, they operated primarily within a reductionist framework that examined drug-target interactions in isolation rather than considering the complexity of biological systems [9].

The Rise of AI and Machine Learning

The past decade has witnessed a fundamental shift from physics-driven and knowledge-driven approaches to data-centric methodologies powered by machine learning and deep learning [11]. This transition has scaled pattern discovery across expansive chemical and biological spaces, elevating predictive modeling from local heuristics to global signals [11]. The expansion of large-scale open data repositories containing chemical and pharmacological datasets has been instrumental in this transformation, with resources like PubChem and ZINC databases providing tens of millions of compounds for analysis [13].

A critical development in this evolution has been the emergence of generative AI models for de novo molecular design. Unlike virtual screening which searches existing chemical libraries, these systems actively generate novel molecular structures optimized for specific therapeutic objectives [9]. Companies like Insilico Medicine pioneered the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning for multi-objective optimization of drug candidates, balancing parameters such as potency, selectivity, and metabolic stability [9]. This approach represents a fundamental shift from searching chemical space to creatively exploring it.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Milestones in Computational Drug Discovery

| Time Period | Technological Paradigm | Key Methodologies | Representative Advances |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s | Molecular Mechanics | Force field development, Molecular dynamics | Implementation of classical physics for biomolecular simulation |

| 1990s-2000s | Structure-Based Design | Molecular docking, QSAR, Virtual screening | First automated docking algorithms, Lipinski's Rule of 5 |

| 2000s-2010s | Multiscale Biomolecular Simulations | QM/MM, Enhanced sampling MD | Nobel Prize 2013 for multiscale models, FBDD yields FDA-approved drugs |

| 2010s-2020s | Machine Learning & Deep Learning | Neural networks, Predictive modeling | AI-designed drug candidates enter clinical trials (e.g., DSP-1181) |

| 2020s-Present | Generative AI & Holistic Biology | Generative models, Knowledge graphs, Transformer architectures | First fully digital drug development cycle (Monash University), Quantum-AI integration |

Contemporary AI-Driven Discovery Platforms

By 2025, AI-driven drug discovery has matured into an integrated discipline characterized by holistic modeling of biological complexity [9]. Leading platforms exemplify this paradigm through their ability to represent multimodal data—including chemical structures, omics profiles, phenotypic readouts, and clinical information—within unified computational frameworks [9]. For instance, Recursion's OS Platform leverages approximately 65 petabytes of proprietary data to map trillions of biological, chemical, and patient-centric relationships, utilizing advanced models like Phenom-2 (a 1.9 billion-parameter vision transformer) to extract insights from biological images [9].

The year 2025 has been identified as an inflection point where hybrid quantum computing and AI converge to create breakthrough capabilities in drug discovery [14]. Quantum computing applications have demonstrated over 20-fold improvement in time-to-solution for fundamental chemical processes like the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, achieving chemical accuracy levels (<1 kcal/mol) impossible with classical approximations alone [14]. This convergence represents the current frontier in computational chemistry, enabling precise simulation of complex electronic properties and reaction mechanisms that underlie drug-target interactions.

Quantitative Impact Assessment

The evolution from molecular mechanics to AI-driven approaches has produced measurable improvements in drug discovery efficiency and effectiveness. The pharmaceutical industry is witnessing unprecedented acceleration in R&D timelines, with AI enabling reductions of up to 50% in early discovery phases [15]. By analyzing comparative performance metrics across different eras of computational methodology, we can quantitatively assess the transformative impact of these technological advances.

Performance Metrics Across Methodological Eras

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Computational Drug Discovery Methods

| Methodology | Time to Lead Identification | Compounds Synthesized | Success Rate | Representative Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Medicinal Chemistry | 4-6 years | Thousands | <10% | Conventional HTS campaigns |

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening | 12-24 months | Hundreds | 10-15% | Docking-based lead identification |

| Fragment-Based Drug Design | 18-36 months | Dozens | 20-30% | Vemurafenib discovery |

| AI-Driven De Novo Design | 3-12 months | <150 | >30% | Exscientia's CDK7 inhibitor (136 compounds) |

| Generative AI with Quantum Computing | 3-6 months | Computational generation | Not yet established | Quantum-AI platform for NDM-1 inhibitors |

The efficiency gains demonstrated in Table 2 highlight the progressive optimization of the drug discovery process. Exscientia's achievement in identifying a clinical candidate CDK7 inhibitor after synthesizing only 136 compounds stands in stark contrast to traditional programs that often require thousands of synthesized compounds [16]. Similarly, Insilico Medicine's generative AI-discovered drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, compared to the traditional 4-6 year timeline [16]. These accelerated timelines represent not merely incremental improvements but fundamental paradigm shifts in pharmaceutical R&D.

Market Validation and Clinical Translation

The quantitative impact of AI-driven discovery is further evidenced by market growth and clinical advancement. The AI in drug discovery market, valued at $1.72 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $8.53 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 30.59% that signals robust adoption and validation of these technologies [14]. By mid-2025, over 75 AI-derived molecules had reached clinical stages, with the number growing exponentially from early examples around 2018-2020 [16]. This rapid clinical translation demonstrates that AI-discovered candidates can successfully navigate the transition from in silico predictions to human testing.

Despite these advances, important quantitative distinctions remain between accelerated discovery and demonstrated clinical efficacy. As of 2025, no AI-discovered drug has received full regulatory approval, with most programs remaining in early-stage trials [16]. This underscores that while AI dramatically compresses early discovery timelines, the fundamental requirements for demonstrating safety and efficacy in human trials remain unchanged. The true test of AI-driven discovery will be whether these computationally generated compounds demonstrate superior clinical outcomes or success rates compared to conventionally discovered drugs [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides detailed protocols for key methodologies that exemplify the integration of computational approaches across the drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to lead optimization.

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Target Identification Using Knowledge Graphs

Principle: This protocol leverages multimodal biological data to systematically identify and prioritize novel therapeutic targets based on their inferred role in disease mechanisms [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological Databases: OMIM, DisGeNET, GTEx, TCGA for disease-gene associations and expression profiles

- Literature Corpus: PubMed, PubMed Central, patent databases (40+ million documents)

- Omics Data Sources: RNA sequencing datasets, proteomics data from 10+ million biological samples

- Computational Tools: Natural language processing (NLP) models, graph neural networks, embedding algorithms

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation and Graph Construction: Compile approximately 1.9 trillion data points from genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and literature sources into a unified knowledge graph [9].

- Relationship Extraction: Apply NLP and transformer-based models to extract entity-relationship-entity triples from textual sources, establishing connections between genes, diseases, compounds, and biological processes.

- Graph Embedding Generation: Encode biological entities and relationships into low-dimensional vector spaces using knowledge graph embedding algorithms, preserving topological and semantic relationships.

- Target Prioritization Scoring: Implement multi-parameter optimization scoring that incorporates genetic evidence, tractability, novelty, and commercial potential to rank candidate targets.

- Biological Validation Planning: Design experimental validation workflows using CRISPR screening, transcriptomic profiling, or phenotypic assays to confirm target-disease association.

Technical Notes: Effective implementation requires distributed computing infrastructure for processing trillion-scale data points. Attention-based neural architectures can refine hypotheses by focusing on biologically relevant subgraphs [9].

Protocol 2: Generative Molecular Design with Multi-Objective Optimization

Principle: This protocol employs deep generative models to design novel molecular structures optimized for multiple drug-like properties simultaneously [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical Databases: ChEMBL, DrugBank, ZINC, proprietary compound libraries

- Generative Models: Generative adversarial networks (GANs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), or transformer architectures

- Property Prediction Tools: ADMET prediction models, molecular dynamics simulation packages

- Synthetic Accessibility Assessment: Retrosynthesis tools, reaction databases

Procedure:

- Model Pretraining: Train generative models on 10+ million known chemical structures to learn fundamental principles of chemical validity and stability.

- Reward Function Definition: Establish multi-objective reward functions balancing potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, solubility, and synthetic accessibility.

- Reinforcement Learning Cycle: Implement policy-gradient-based reinforcement learning to optimize generated structures against the multi-parameter reward function.

- Structural Refinement: Apply transfer learning to fine-tune generated molecules for specific target classes or binding pockets.

- In Silico Validation: Execute molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability and free energy calculations (MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA) to predict binding affinity.

Technical Notes: Chemistry-aware representation methods like SELFIES encoding guarantee 100% valid molecular generation, overcoming limitations of traditional SMILES-based approaches [14]. Distributed training frameworks such as DeepSpeed with ZeRO optimizer partitioning can reduce memory requirements by 50% while enabling linear scaling across multiple GPUs [14].

Protocol 3: Quantum-Enhanced Binding Affinity Calculation

Principle: This protocol utilizes hybrid quantum-classical algorithms to achieve chemical accuracy in predicting drug-target binding energetics, particularly for challenging targets with metal coordination or complex electronic properties [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Quantum Computing Access: Cloud-based quantum processing units (QPUs) via AWS Braket, Azure Quantum, or similar services

- Classical Computing Resources: High-performance computing clusters with GPU acceleration

- Molecular Preparation Tools: Protein preparation software, quantum chemistry packages for initial structure optimization

Procedure:

- System Partitioning: Divide the molecular system into quantum mechanical (QM) region (active site with ligand and key residues) and molecular mechanical (MM) region (remaining protein and solvent).

- Hamiltonian Formulation: Construct the molecular Hamiltonian for the QM region, incorporating electronic degrees of freedom.

- Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Execution: Run VQE algorithms on quantum hardware to compute ground state energy of the ligand-target complex with chemical accuracy (<1 kcal/mol error) [14].

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Combine quantum mechanical energies with classical force field contributions using MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA approaches.

- Ensemble Averaging: Perform molecular dynamics sampling to generate multiple conformational snapshots, with quantum calculations on representative structures.

Technical Notes: This approach is particularly valuable for metalloenzyme targets like NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase, where classical force fields struggle to accurately model zinc coordination chemistry [14]. Current implementations typically utilize hybrid quantum-classical algorithms due to limitations in quantum hardware coherence times.

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and architectural frameworks described in the protocols, generated using Graphviz DOT language with adherence to the specified color palette and contrast requirements.

AI-Driven Drug Discovery Pipeline

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Drug Discovery Pipeline

Quantum-Classical Computational Workflow

Diagram 2: Quantum-Classical Computational Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools, data resources, and platform components that constitute the modern researcher's toolkit for AI-driven drug discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative AI Platforms | Insilico Medicine Pharma.AI, Iambic Therapeutics Platform | De novo molecular design with multi-parameter optimization | Commercial licensing |

| Knowledge Graph Systems | Recursion OS Knowledge Graph, PandaOmics | Target identification through biological relationship mapping | Commercial platforms |

| Quantum Computing Access | AWS Braket, Azure Quantum | High-accuracy molecular simulation via quantum processors | Cloud-based services |

| Specialized AI Models | NeuralPLexer (Iambic), Phenom-2 (Recursion) | Protein-ligand complex prediction, Phenotypic screening analysis | Integrated within platforms |

| Data Resources | PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL, GDB-17 | Chemical libraries for training and validation | Public access |

| Validation Tools | Molecular dynamics packages, ADMET prediction models | In silico assessment of compound properties | Open source and commercial |

The historical progression from molecular mechanics to AI-driven discovery represents a fundamental transformation in computational chemistry's role in drug design research. What began as specialized tools for simulating molecular interactions has evolved into comprehensive platforms capable of representing biological complexity holistically and generating novel therapeutic candidates with optimized properties. The quantitative evidence demonstrates unambiguous acceleration in early discovery timelines, with AI-driven approaches compressing years of work into months while reducing the number of compounds requiring synthesis and testing. As we look toward the future, the convergence of AI with quantum computing and automated experimental validation promises to further redefine the boundaries of computational drug discovery. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these methodological advances and their practical implementation through detailed protocols provides critical insights for leveraging these technologies in the pursuit of novel therapeutics. The ongoing challenge remains the translation of computational efficiency gains into demonstrated clinical success, which will ultimately validate the transformative potential of AI-driven discovery approaches.

Computational chemistry provides the essential tools to understand molecular interactions at an atomic level, forming a critical foundation for modern drug discovery and development. The process of bringing a new drug to market is notoriously time-consuming and expensive, often taking 12–16 years of exhaustive research and clinical trials [17]. In this context, computational methods offer powerful approaches to accelerate discovery timelines and reduce costly late-stage failures. Among these methods, three complementary paradigms have emerged as particularly transformative: Quantum Mechanics (QM), Molecular Mechanics (MM), and Multiscale Modeling that strategically integrates both approaches [18] [19].

These techniques enable researchers to probe drug-target interactions with varying degrees of accuracy and computational efficiency, creating a versatile toolkit for addressing different challenges in structure-based drug design. The pharmaceutical industry increasingly relies on these computational approaches to elucidate complex biological mechanisms, predict binding affinities, and optimize lead compounds with greater precision than traditional experimental methods alone can provide [17] [18].

Theoretical Foundations

Quantum Mechanics (QM)

Quantum Mechanics methods apply the fundamental laws of quantum physics to approximate molecular wave functions and solve the Schrödinger equation for molecular systems [17]. Unlike simpler approaches, QM explicitly treats electrons, providing detailed information about electron distribution, bonding characteristics, and chemical reactivity. This makes QM particularly valuable for studying chemical reactions, charge transfer processes, and spectroscopic properties [17] [19].

The fundamental time-independent Schrödinger equation is represented as:

HΨ = EΨ

Where H is the Hamiltonian operator, Ψ is the wave function, and E is the energy of the system [17]. While exact solutions are only possible for one-electron systems, modern computational implementations employ sophisticated approximations that bring QM accuracy to increasingly complex biomolecular systems relevant to drug design [17] [20].

Molecular Mechanics (MM)

Molecular Mechanics approaches biomolecular systems through classical mechanics, treating atoms as spheres and bonds as springs. This simplification allows MM to handle much larger systems than QM, including entire proteins in their physiological environments [17]. MM describes the total potential energy of a system using a combination of bonded and non-bonded terms:

Etot = Estr + Ebend + Etor + Evdw + Eelec [17]

Where the components represent bond stretching (Estr), angle bending (Ebend), torsional angles (Etor), van der Waals interactions (Evdw), and electrostatic forces (Eelec) [17]. The efficiency of MM force fields enables molecular dynamics simulations that can explore microsecond to millisecond timescales, providing crucial insights into protein flexibility, ligand binding pathways, and conformational changes [18].

Multiscale Modeling (QM/MM)

Multiscale QM/MM methods combine the accuracy of QM for describing reactive regions with the efficiency of MM for treating the surrounding environment [21] [19]. This hybrid approach was pioneered by Warshel and Levitt in 1976 and recognized with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [18]. QM/MM simulations partition the system into two regions: a QM region (typically the active site with substrate) where chemical bonds are formed and broken, and an MM region (protein scaffold and solvent) that provides a realistic environmental context [19].

Recent advances have extended QM/MM to massively parallel implementations capable of strong scaling with ~70% parallel efficiency on more than 80,000 cores, opening the door to simulating increasingly complex biological processes with quantum accuracy [21]. Furthermore, the incorporation of machine learning potentials (MLPs) has accelerated these methods to approach coupled-cluster accuracy while dramatically reducing computational costs [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Computational Chemistry Methods

| Parameter | Quantum Mechanics (QM) | Molecular Mechanics (MM) | Multiscale QM/MM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Quantum physics, Schrödinger equation | Classical mechanics, Newton's laws | Combined quantum-classical |

| System Treatment | Electrons and nuclei explicitly treated | Atoms as spheres, bonds as springs | QM: Electronic structure; MM: Classical atoms |

| Computational Cost | Very high (O(N³) to O(eⁿ)) | Low to moderate | High, but less than full QM |

| System Size Limit | Small (typically <500 atoms) | Very large (>1,000,000 atoms) | Medium to large |

| Accuracy for Reactions | High | Poor | High in QM region |

| Typical Applications | Chemical reactions, spectroscopy, excitation states | Protein dynamics, conformational sampling, binding | Enzyme mechanisms, catalytic pathways, drug binding |

| Recent Advances | Machine learning potentials [20] | Enhanced sampling, free energy calculations [22] | Exascale computing, ML-aided sampling [21] [22] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for MLP Methods in Drug Structure Optimization (QR50 Dataset) [20]

| Method | Bond Distance MAD (Å) | Angle MAD (°) | Rotatable Dihedral MAD (°) | Applicable Elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ωB97X-D/6-31G(d) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Essentially all |

| AIQM1 | 0.005 | 0.6 | 11.2 | C, H, O, N |

| ANI-2x | 0.008 | 0.9 | 16.1 | C, H, O, N, F, Cl, S |

| GFN2-xTB | 0.008 | 0.9 | 16.1 | Essentially all |

Application Notes for Drug Design

Quantum Refinement of Protein-Drug Complexes

Quantum refinement (QR) methods employ QM calculations during the crystallographic refinement process to improve the structural quality of protein-drug complexes [20]. Standard refinement based on molecular mechanics force fields struggles with the enormous diversity of chemical space occupied by drug molecules, particularly for systems with complex electronic effects such as conjugation and delocalization [20]. QR methods overcome these limitations by providing a more reliable description of the electronic structure of bound ligands.

A landmark application of QR involved the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (MPro) in complex with the FDA-approved drug nirmatrelvir. Through QR approaches, researchers obtained computational evidence for the coexistence of both bonded and nonbonded forms of the drug within the same crystal structure [20]. This atomic-level insight provides valuable information for designing improved antiviral agents with optimized binding characteristics.

The integration of machine learning potentials with multiscale ONIOM schemes has dramatically accelerated QR applications. Novel methods such as ONIOM3(MLP-CC:MLP-DFT:MM) and ONIOM4(MLP-CC:MLP-DFT:SE:MM) achieve coupled-cluster quality results while maintaining computational efficiency sufficient for routine application to protein-drug systems [20].

Binding Affinity Prediction with QM/MM

Accurate prediction of binding free energies remains a central challenge in structure-based drug design. Traditional MM-based approaches, while computationally efficient, often lack the precision required for reliable lead optimization due to their simplified treatment of electronic effects and non-covalent interactions [22]. QM/MM methods address this limitation by providing a more physical description of critical interactions such as hydrogen bonding, charge transfer, and polarization effects.

Combining QM/MM with free energy perturbation techniques and machine learning-enhanced sampling algorithms represents a promising frontier in drug design [22]. This integrated approach allows researchers to map binding energy landscapes with quantum accuracy while accessing biologically relevant timescales. The implementation of these methods on exascale computing architectures further extends their applicability to pharmaceutically relevant targets [21] [22].

Successful applications of QM/MM in binding affinity prediction include studies of acetylcholinesterase with the anti-Alzheimer drug donepezil and serine proteases with benzamidinium-based inhibitors [20]. These implementations demonstrate the potential of QM/MM to deliver both qualitative insights into binding mechanisms and quantitative predictions of binding affinities.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantum Refinement of Protein-Ligand Complex

Objective: Improve the structural quality of a crystallographic protein-ligand complex using quantum refinement techniques.

Materials and Software:

- Initial protein-ligand structure (PDB format)

- Crystallographic structure factor data

- Quantum chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA)

- Molecular dynamics package with QM/MM capability

- Machine learning potential implementation (e.g., ANI-2x, AIQM1)

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Extract the ligand and active site residues from the PDB file

- Add hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH

- Define the QM region (typically the ligand and key catalytic residues)

- Set up the MM region (remaining protein and solvent environment)

Multiscale Setup:

- Apply the ONIOM (Our own N-layered Integrated molecular Orbital and molecular Mechanics) scheme

- Implement the electrostatic embedding to account for polarization effects

- Define the boundary between QM and MM regions using link atoms

Geometry Optimization:

- Perform initial optimization with DFT method (e.g., ωB97X-D/6-31G(d))

- Compare results with MLP methods (AIQM1 or ANI-2x for eligible elements)

- Calculate final energies with higher-level theory if needed

Refinement Validation:

- Analyze geometric parameters (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals)

- Calculate R and Rfree factors against experimental data

- Compare electron density maps before and after refinement

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For charged ligand systems, verify the performance of MLP methods on similar chemical motifs

- If convergence issues occur, consider increasing the QM region size or adjusting optimization algorithms

- Validate results against multiple DFT functionals when possible [20]

Protocol 2: QM/MM Molecular Dynamics with Enhanced Sampling

Objective: Characterize the binding pathway and mechanism of a drug candidate to its protein target.

Materials and Software:

- High-performance computing cluster (CPU/GPU hybrid)

- QM/MM-enabled MD software (e.g., AMBER, CP2K, MiMiC)

- Machine learning-enhanced sampling plugins (e.g., PLUMED, SSAGES)

- Visualization tools (VMD, PyMOL)

Procedure:

- System Initialization:

- Prepare the solvated protein-ligand system with appropriate ion concentration

- Define the QM region to include the ligand and binding site residues

- Select appropriate QM method (DFT for accuracy, semiempirical for efficiency)

- Apply MM force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) to the remainder

Equilibration Phase:

- Perform MM-only minimization and heating (0-300K)

- Switch to QM/MM dynamics with constrained protein backbone

- Gradually release constraints while monitoring system stability

Enhanced Sampling Production:

- Implement machine learning-aided sampling algorithm

- For binding free energy calculations, employ metadynamics or adaptive sampling

- Run multiple independent replicas (≥3) to ensure statistical significance

- Collect aggregate simulation time of ≥100 ns per replica

Data Analysis:

- Identify key binding intermediates and transition states

- Calculate binding free energy and decomposition

- Map interaction networks and evolution over time [22]

Advanced Applications:

- For large systems, leverage massively parallel implementations (e.g., MiMiC framework)

- Incorporate experimental data as constraints during simulation

- Use Markov state models to analyze kinetics from multiple trajectories [21]

Visualization and Workflow

Diagram 1: Integrated QM/MM Drug Design Workflow. This workflow illustrates the strategic integration of molecular mechanics, quantum mechanics, and multiscale approaches in structure-based drug design.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | License | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avogadro | Molecular Editor | Molecule building/visualization | Free open-source, GPL | Cross-platform, flexible rendering, Python extensibility [23] [24] |

| VMD | Visualization & Analysis | Molecular dynamics analysis | Free for noncommercial use | Extensive trajectory analysis, Tcl/Python scripting [23] |

| Molden | Visualization | Quantum chemical results | Proprietary, free academic use | Molecular orbitals, vibrations, multiple formats [23] |

| Jmol | Viewer | Structure visualization | Free open-source | Java-based, advanced capabilities, symmetry [23] |

| PyMOL | Visualization | Publication-quality images | Open-source | Python integration, scripting capabilities [25] |

| MiMiC | QM/MM Framework | Multiscale simulations | Not specified | Massively parallel, exascale-ready [21] |

| ANI-2x | Machine Learning Potential | Accelerated QM calculations | Not specified | DFT accuracy for C,H,O,N,F,Cl,S [20] |

| AIQM1 | Machine Learning Potential | Coupled-cluster level accuracy | Not specified | Approach CC accuracy for organic molecules [20] |

The integration of Quantum Mechanics, Molecular Mechanics, and Multiscale Modeling represents a paradigm shift in computational chemistry's application to drug design. These complementary approaches enable researchers to navigate the complex landscape of molecular interactions with an unprecedented combination of accuracy and efficiency. The continuing evolution of these methods—driven by advances in exascale computing, machine learning algorithms, and multiscale methodologies—promises to further transform pharmaceutical development.

As these computational techniques become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they offer the potential to address long-standing challenges in drug discovery, including the prediction of off-target effects, the design of covalent inhibitors, and the characterization of allosteric binding mechanisms. The convergence of physical simulation methods with data-driven approaches establishes a powerful framework for accelerating the development of novel therapeutics, ultimately contributing to improved human health and more efficient pharmaceutical research pipelines.

Modern drug discovery is a complex, costly, and time-intensive endeavor. The integration of computational chemistry has revolutionized this process, enhancing efficiency and precision across the entire pipeline. From initial target identification to lead optimization, computational methods provide powerful tools for predicting molecular behavior, optimizing drug-like properties, and reducing experimental failure rates. This application note details specific computational methodologies, complete with quantitative benchmarks and experimental protocols, to guide researchers in leveraging these technologies for accelerated therapeutic development [26] [27].

The drug discovery pipeline has evolved from serendipitous findings to a rational, system-based design. Early methods often relied on accidental discoveries, such as penicillin, but advances in molecular cloning, X-ray crystallography, and robotics now enable targeted drug design [27]. Computational approaches are indispensable in this modern framework, allowing researchers to navigate vast chemical and biological spaces that would be impractical to explore through traditional experimental means alone [26]. These methods are broadly classified into structure-based and ligand-based design, each with distinct applications and advantages depending on the available biological and chemical information [28] [27].

Core Computational Strategies and Their Quantitative Impact

Computational methods create value by providing predictive models and enabling virtual screening of immense compound libraries. The following strategies represent the most impactful applications in the current drug discovery landscape.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) utilizes three-dimensional structural information about a biological target, typically from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy. The primary advantage of SBDD is its ability to design novel compounds that are shape-complementary to the target's active site, facilitating optimal interactions [27]. Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) is employed when the target structure is unknown or difficult to obtain. This approach extracts essential chemical features from known active compounds to predict the biological properties of new molecules [27]. The underlying principle is that structurally similar molecules likely exhibit similar biological activities [27].

Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) represents a paradigm shift from traditional inhibition to degradation. This approach employs small molecules, such as PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs), to tag undruggable proteins for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system [26]. DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) combine combinatorial chemistry with molecular biology, allowing for the high-throughput screening of millions to billions of compounds by using DNA barcodes to record synthetic history [26]. Click Chemistry provides highly efficient and selective reactions, such as the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), to rapidly synthesize diverse compound libraries and complex structures like PROTACs [26].

Table 1: Key Computational Strategies in Drug Discovery

| Strategy | Primary Application | Data Requirements | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Design (SBDD) [28] [27] | De novo drug design, lead optimization | Target protein structure (X-ray, Cryo-EM, Homology Model) | Up to 10-fold reduction in candidate synthesis vs. HTS [27] |

| Ligand-Based Design (LBDD) [28] [27] | Hit finding, lead optimization, toxicity prediction | Known active ligand(s) and their bioactivity data | >80% accurate target prediction via similarity methods [27] |

| Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) [26] | Addressing "undruggable" targets (e.g., scaffolding proteins) | Ligand for E3 ligase + ligand for target protein | Enabled degradation of ~600 disease targets previously considered undruggable [26] |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) [26] | Ultra-high-throughput screening | Library construction with DNA barcodes | Screening of >10^8 compounds in a single experiment [26] |

| Click Chemistry [26] | Library synthesis, PROTAC assembly, bioconjugation | Azide and alkyne-functionalized precursors | Reaction yields often >95% with minimal byproducts [26] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for identifying novel hit compounds through molecular docking against a protein target of known structure [28] [27].

Step 1: Target Preparation

- Isolate the protein structure from a protein data bank (PDB) file.

- Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, except for crucial structural waters or cofactors.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM).

- Define the binding site as a 3D grid, typically centered on the native ligand's location or a known active site.

Step 2: Ligand Library Preparation

- Acquire a small molecule library in a standard format (e.g., SDF, SMILES).

- Generate plausible 3D conformations for each compound.

- Assign correct protonation states at physiological pH (7.4) and minimize energy.

Step 3: Molecular Docking

- Select a docking algorithm (e.g., Glide, AutoDock Vina, GOLD).

- Execute the docking run, allowing ligands to flex within the rigid or semi-flexible protein binding site.

- Generate multiple pose predictions per ligand.

Step 4: Post-Docking Analysis and Scoring

- Rank all docked poses using a scoring function to estimate binding affinity.

- Visually inspect the top-ranking poses (e.g., top 100-500) to assess binding mode rationality, key interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking), and chemical sensibility.

- Select a diverse subset of high-ranking compounds (50-200) for in vitro experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Similarity Search and SAR Analysis

This protocol is used when a known active compound exists but the 3D structure of the target is unavailable [27].

Step 1: Query Compound and Fingerprint Selection

- Select the known active compound as the query.

- Choose an appropriate chemical fingerprinting method:

- Path-based (e.g., Daylight): Encodes all possible molecular paths of specified lengths. Offers high specificity.

- Substructure-based (e.g., MACCS keys): Encodes the presence/absence of a predefined set of chemical substructures. Better for "scaffold hopping."

Step 2: Database Search and Similarity Calculation

- Search a large chemical database (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house library) using the query fingerprint.

- Calculate pairwise similarity using the Tanimoto coefficient:

- T(A,B) = (Number of common bits in A and B) / (Total number of bits in A or B)

- Compounds with a Tanimoto score > 0.7 - 0.8 are generally considered highly similar.

Step 3: Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis

- Cluster the similar compounds based on their core scaffolds.

- Correlate structural variations (e.g., addition of a methyl group, change from -OH to -NH₂) with changes in biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki).

- Use this SAR to guide the design of new analogs with predicted improved potency or selectivity.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Protocols

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary source of 3D protein structures for target preparation [27]. |

| ZINC/ChEMBL Database | Database | Publicly available repositories of purchasable and bioactive compounds for virtual screening [27]. |

| Daylight/MACCS Fingerprints | Computational Descriptor | Mathematical representation of molecular structure for similarity searching and machine learning [27]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | Algorithm | Quantitative metric (0-1) for calculating chemical similarity between two molecular fingerprints [27]. |

| Homology Modeling Tool (e.g., MODELLER) | Software | Generates a 3D protein model from its amino acid sequence when an experimental structure is unavailable [28]. |

| E3 Ligase Ligand (e.g., for VHL) | Chemical Probe | Critical component for designing PROTACs in Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) campaigns [26]. |

Emerging Frontiers: AI and Automation

The next frontier of computational drug discovery lies in the synergistic application of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation. Machine learning (ML) models, particularly deep learning, are now being used to extract maximum knowledge from existing chemical and biological data [26] [29]. These models can predict complex molecular properties, design novel compounds with desired attributes de novo, and even forecast clinical trial outcomes.

A key development is the integration of machine learning with physics-based computational chemistry [29]. This hybrid approach leverages the predictive power of AI while grounding it in the physical laws that govern molecular interactions. For instance, AI can be used to rapidly pre-screen millions of compounds, while more computationally intensive, physics-based free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculations provide highly accurate binding affinity predictions for a much smaller, prioritized subset [29]. This combined strategy dramatically accelerates the lead optimization cycle. The role of computational chemists is evolving into that of "drug hunters" who must understand and apply this expanding toolbox to make efficient and effective decisions in therapeutic development [30].

In the modern drug discovery pipeline, computational chemistry serves as a critical foundation for reducing the immense costs and high attrition rates associated with bringing new therapeutics to market. With the estimated cost of drug development exceeding $2 billion per approved drug, efficient navigation of the initial discovery phases through computational approaches provides a significant strategic advantage [31]. Central to these approaches are publicly accessible chemical and biological databases that provide the structural and bioactivity data necessary for informed decision-making.

This application note details the essential characteristics and practical applications of four cornerstone databases: the Protein Data Bank (PDB), ZINC, ChEMBL, and BindingDB. Each database occupies a distinct niche within the computational workflow, from providing three-dimensional structural blueprints of biological macromolecules to offering vast libraries of purchasable compounds and curated bioactivity data. By understanding their complementary strengths, researchers can strategically leverage these resources to streamline the journey from target identification to lead compound optimization, thereby de-risking the early stages of drug development [31].

Database Comparative Analysis

The table below provides a quantitative summary and comparative overview of the four core databases, highlighting their primary functions, content focus, and key access mechanisms.

Table 1: Essential Databases for Computational Drug Discovery

| Database | Primary Function | Key Content | Data Volume (Approx.) | Unique Features & Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB [32] | 3D structural repository for macromolecules | Experimentally-determined structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes | >200,000 experimental structures | Provides visualization & analysis tools; integrates with AlphaFold DB CSMs |

| ZINC [33] [34] | Curated library of commercially available compounds | "Ready-to-dock" small molecules for virtual screening | ~1.4 billion compounds | Features SmallWorld for similarity search & Arthor for substructure search |

| ChEMBL [35] | Manually curated bioactivity database | Drug-like molecules, ADMET properties, and bioassay data | Millions of bioactivities | Open, FAIR data; includes curated data for SARS-CoV-2 screens |

| BindingDB [36] | Focused binding affinity database | Measured binding affinities (e.g., IC50, Ki) for protein-ligand pairs | ~1.1 million binding data points | Supports queries by chemical structure, protein sequence, and affinity range |

Database-Specific Application Notes

Protein Data Bank (PDB)

Overview and Strategic Value: The Protein Data Bank serves as the universal archive for three-dimensional structural data of biological macromolecules, determined through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and Cryo-Electron Microscopy [32]. Its strategic value lies in providing atomic-level insights into drug targets, enabling researchers to understand active sites, binding pockets, and molecular mechanisms of action, which form the basis for structure-based drug design.

Key Applications:

- Target Identification and Validation: Researchers can explore structures of potential drug targets, including their native state and complexes with natural ligands or other proteins, to assess their "druggability" [31].

- Structure-Based Drug Design: The 3D structural coordinates from the PDB are used to model ligand docking, identify key interactions, and guide the rational optimization of lead compounds [37].

- Comparative Analysis: By examining multiple structures of the same target with different ligands, scientists can derive critical structure-activity relationships (SAR) to inform chemical modifications.

Protocol 1.1: Retrieving and Preparing a Protein Structure for Molecular Docking

- Structure Retrieval: Navigate to the RCSB PDB website (https://www.rcsb.org) [32]. Search for your target protein using its name or PDB ID. From the search results, select the most appropriate structure based on resolution (prioritize lower numbers, e.g., <2.0 Å for X-ray structures), the presence of a relevant ligand or co-crystalized inhibitor, and the absence of major mutations.

- Structure Analysis: On the structure summary page, use the integrated 3D viewer to visually inspect the binding site of interest. Review the accompanying publication to understand the biological context of the structure.

- Data Preparation: Download the PDB file. Using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, Chimera), remove water molecules, heteroatoms, and original ligands not relevant to your study. Add necessary hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states to key residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His) in the binding site. Finally, minimize the energy of the prepared structure to relieve any steric clashes.

ZINC Database

Overview and Strategic Value: ZINC is a meticulously curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds optimized for virtual screening [33] [34]. Its primary strategic value is in bridging computational predictions and experimental validation by providing a source of tangible molecules that can be purchased for biological testing shortly after computational prioritization.

Key Applications:

- Virtual High-Throughput Screening (vHTS): ZINC's "ready-to-dock" molecular formats and pre-filtered libraries (e.g., by drug-likeness, lead-likeness) enable rapid in silico screening of billions of compounds against a target structure [33].

- Hit Identification and Expansion: Researchers can use ZINC's integrated tools, like the SmallWorld graph-based similarity search, to find close structural analogs of a weak hit compound, thereby exploring the local chemical space to improve potency or other properties [33].

Protocol 1.2: Conducting a Large-Scale Virtual Screen with ZINC20

- Library Selection: Access the ZINC20 website and navigate to the "Subsets" section. Based on your target and screening goals (e.g., lead discovery vs. fragment-based screening), select a pre-defined subset such as "ZINC22 Lead-Like," "ZINC22 Drug-Like," or a target-focused library.

- Compound Download: Use the provided filters to specify desired properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, number of rotatable bonds). Download the resulting library in a suitable format for your docking software (e.g., SDF, MOL2).

- Virtual Screening Execution: Prepare the downloaded library by adding charges and energy minimizing if required. Perform molecular docking against your prepared protein target (from Protocol 1.1) using software like AutoDock Vina or DOCK. Rank the results based on the docking score or predicted binding affinity.

- Hit Procurement: For the top-ranking compounds, use the provided ZINC vendor information and catalog IDs to purchase the physical samples for subsequent experimental validation in biochemical or cellular assays.

ChEMBL Database

Overview and Strategic Value: ChEMBL is a large-scale, open-source database manually curated from the scientific literature to contain bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [35]. Its strategic value lies in its extensive collection of annotated bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki), which allows researchers to perform robust SAR analyses, predict potential off-target effects, and gain insights into ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties early in the discovery process [31] [35].

Key Applications:

- Lead Optimization: By querying ChEMBL for a lead compound's close analogs and their associated bioactivity data, medicinal chemists can make data-driven decisions on which chemical groups to modify to enhance potency or selectivity.

- Drug Repurposing: Systematic screening of ChEMBL's bioactivity data for approved drugs can reveal novel activities against different therapeutic targets, identifying new indications for existing drugs [35].

- Bioactivity Profiling: Before investing in a new chemical series, researchers can search ChEMBL to check for any reported activities on other targets, helping to assess the potential for adverse effects.

Protocol 1.3: Mining Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) in ChEMBL

- Query Input: Access the ChEMBL web interface (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/) [35]. Input the SMILES string or chemical structure of your lead compound using the chemical search tool.

- Data Retrieval and Filtering: Execute the search and navigate to the compound report card. Review the list of associated bioassays and target information. Use filters to select data for your specific target of interest and a consistent activity type (e.g., IC50).

- SAR Analysis: Export the activity data for the compound and its analogs. In a spreadsheet or chemoinformatics tool, organize the data by chemical scaffold and R-group substitutions. Correlate specific structural changes with changes in potency to generate hypotheses for the next round of chemical synthesis.

BindingDB Database

Overview and Strategic Value: BindingDB focuses specifically on providing measured binding affinities, primarily for protein targets considered relevant to drug discovery [36]. It complements ChEMBL by offering a concentrated resource of quantitative interaction data, which is crucial for developing and validating predictive computational models.

Key Applications:

- Benchmarking Docking Algorithms: The high-quality, experimentally determined binding affinities in BindingDB are used as "ground truth" to calibrate and assess the performance of scoring functions in molecular docking software [36].

- Predictive Model Training: The database serves as a key data source for training machine learning models to predict the binding strength of novel compounds.

- Chemical Probe Identification: Researchers can quickly identify the most potent known ligands for a protein target of interest to use as chemical probes in functional studies.

Protocol 1.4: Validating a Docking Pose and Scoring Function with BindingDB

- Identify a Benchmark Set: Query BindingDB using the advanced search option. Specify your target protein (by name or UniProt ID) and set a filter for high-affinity ligands (e.g., Ki < 100 nM) with available PDB structures of their complexes.

- Data Compilation: Download the 3D structures of the protein-ligand complexes from the PDB. From BindingDB, export the corresponding binding affinity data for these complexes.

- Docking and Correlation: Using your chosen docking software, re-dock each ligand into its respective protein structure. Calculate the correlation between the docking scores generated by the software and the experimental binding affinities from BindingDB. A strong correlation increases confidence in the docking protocol's ability to rank novel compounds correctly.

Integrated Workflow for Lead Identification

The true power of these databases is realized when they are used in a coordinated, sequential workflow. The following diagram and protocol outline a typical pathway for computational lead identification and optimization.

Diagram: Integrated computational workflow for lead identification.

Protocol 1.5: Integrated Workflow for Structure-Based Lead Discovery

- Target Selection and Structure Acquisition: Begin with a genetically validated therapeutic target (e.g., a kinase). Search the PDB for a high-resolution crystal structure of the target, preferably in a complex with an active-site inhibitor [32].

- Virtual Screening Library Preparation: Prepare the protein structure as in Protocol 1.1. Simultaneously, download a relevant, filtered subset (e.g., "drug-like") of several million compounds from the ZINC database [33].

- High-Throughput Docking and Hit Selection: Perform molecular docking of the ZINC library against the prepared target. From the millions of docked poses, select a few hundred top-ranking compounds based on docking score and binding pose quality.

- In Silico Bioactivity Profiling: Interrogate ChEMBL and BindingDB with the structures of the putative hits [35] [36]. This step checks for any known undesirable off-target activities or, conversely, may reveal additional therapeutic potential. It also helps prioritize compounds with structural similarities to known active molecules.

- Procurement and Experimental Testing: Purchase the top 20-50 prioritized compounds from commercial vendors via their ZINC IDs. Subject these compounds to experimental assays to confirm binding and functional activity, thus initiating the cycle of lead optimization.

The following table lists key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for executing the protocols described in this document.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Computational Drug Discovery

| Category | Item/Resource | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Molecular Visualization Software | Visualizes 3D structures from PDB; prepares structures for docking. | PyMOL, UCSF Chimera |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts how small molecules bind to a protein target. | AutoDock Vina, Glide, DOCK | |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Manipulates chemical structures, handles file formats, calculates descriptors. | RDKit, Open Babel | |

| Data Resources | Protein Target Sequence | Uniquely identifies the protein target for database searches. | UniProt Knowledgebase |

| Canonical SMILES | Text-based representation of a molecule's structure for database queries. | Generated via RDKit or from PubChem | |

| Commercial Compound Vendor | Source for physical samples of computationally identified hits. | Suppliers listed in ZINC (e.g., Enamine, Sigma-Aldrich) | |

| Experimental Reagents | Purified Target Protein | Required for experimental validation of binding (e.g., SPR, ITC). | Recombinant expression |

| Biochemical/Cellular Assay | Measures the functional activity of hit compounds. | Target-specific activity assay |

The strategic integration of PDB, ZINC, ChEMBL, and BindingDB creates a powerful, synergistic ecosystem for computational drug discovery. Each database fills a critical niche: PDB provides the structural blueprints, ZINC offers the chemical matter, while ChEMBL and BindingDB deliver the essential bioactivity context. By adhering to the application notes and detailed protocols outlined in this document, researchers can construct a robust and efficient workflow. This approach systematically transitions from a biological target to experimentally validated lead compounds, thereby accelerating the early drug discovery pipeline and enhancing the probability of technical success.

Computational Methodologies in Action: Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Approaches

Molecular docking is a fundamental computational technique in structural biology and computer-aided drug design (CADD) used to predict the preferred orientation and binding mode of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a protein target [38]. This method is essential for understanding biochemical processes, elucidating molecular recognition, and designing novel therapeutic agents [39]. By predicting ligand-receptor interactions, docking facilitates hit identification, lead optimization, and the rational design of compounds with improved affinity and specificity [38] [27].

The docking process involves two key components: pose prediction, which generates plausible binding conformations, and scoring, which ranks these poses based on estimated binding affinity [40]. Successful docking can reproduce experimental binding modes, typically validated by calculating the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between predicted and crystallographic poses, with values less than 2.0 Å indicating satisfactory prediction [40].

Principles of Protein-Ligand Interactions

The binding of a ligand to its protein target is governed by complementary non-covalent interactions. Understanding these principles is crucial for interpreting docking results and designing effective drugs [38].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in a molecular docking experiment:

Key Interaction Types

- Shape Complementarity: The ligand must sterically fit into the binding pocket of the protein [38].

- Electrostatic Interactions: Include hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions (salt bridges), crucial for binding specificity and affinity [38].

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Occur between non-polar regions of the ligand and protein, contributing significantly to binding energy through the hydrophobic effect [38].

- Van der Waals Forces: Encompass both attractive (dispersion) and repulsive components, playing an important role in close-range interactions [38].

- π-π Stacking: Interactions between aromatic rings in the ligand and protein, often involving pi orbitals [38].

Energetic Considerations

The binding process involves a complex balance of energy components. Desolvation energy, required to displace water molecules from the binding site, is a critical factor influencing the final binding affinity [38]. The overall binding free energy (ΔG) determines the stability of the protein-ligand complex and can be estimated using scoring functions with the general form:

[ \Delta G = \sum{i=1}^{N} wi \times f_i ]

where (wi) represents weights and (fi) represents individual energy terms [38].

Docking Algorithms and Scoring Functions

Various docking algorithms have been developed, each employing different search strategies and scoring functions to predict ligand binding.

Popular Docking Algorithms

Table 1: Comparison of Popular Molecular Docking Software

| Docking Algorithm | Search Protocol | Scoring Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock | Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm | AutoDock4 Scoring Function | Widely used, robust protocol [38] |

| Glide | Hierarchical Search Protocol | GlideScore | High accuracy, hierarchical filters [38] |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm | GoldScore, ChemScore | Handles large ligands, robust performance [38] |

| FlexX | Incremental Construction | Various | Efficient fragment-based approach [40] |

| Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) | Evolutionary Algorithm | MolDock Score | Integrated visualization environment [40] |

Performance Benchmarking

A comprehensive study evaluating five docking programs for predicting binding modes of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors demonstrated varying performance levels [40]. The Glide program correctly predicted binding poses (RMSD < 2Å) for all studied co-crystallized ligands of COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, achieving 100% success rate. Other programs showed performance between 59-82% in pose prediction [40].