Computational Spectroscopy: Bridging Theory and Experiment for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Analysis

This article explores the integration of computational models with spectroscopy to understand molecular properties, a field revolutionizing drug development and materials science.

Computational Spectroscopy: Bridging Theory and Experiment for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Analysis

Abstract

This article explores the integration of computational models with spectroscopy to understand molecular properties, a field revolutionizing drug development and materials science. It covers the foundational principles of computational spectroscopy, detailing how quantum chemistry and machine learning (ML) interpret complex spectral data. The methodological section examines practical applications, from predicting electronic properties to automating spectral analysis. We address key challenges like data scarcity and model generalization, offering optimization strategies from current research. Finally, the article provides a framework for validating computational predictions against experimental results, highlighting transformative case studies in biomedical research. This guide equips scientists with the knowledge to leverage computational spectroscopy for accelerated and more reliable research outcomes.

The Fundamentals of Computational Spectroscopy: From Quantum Chemistry to AI

The interaction between light and matter provides a non-destructive window into molecular architecture. Spectral signatures—the unique patterns of absorption, emission, or scattering of electromagnetic radiation—are direct manifestations of a molecule's internal structure, dynamics, and environment [1]. The core principle underpinning this relationship is that molecular structure dictates energy levels, which in turn govern how a molecule interacts with specific wavelengths of light [2].

Computational spectroscopy has emerged as an indispensable bridge, connecting theoretical models of molecular structure with empirical spectral data. By solving the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics for target systems, computational models can simulate spectra, interpret complex spectral features, and predict the spectroscopic behavior of molecules, thereby transforming spectral data into structural insight [3] [2]. This synergy is particularly critical in fields like drug development, where understanding the intricate structure-property relationships of bioactive molecules can accelerate and refine the discovery process.

Quantum Mechanical Foundations

The theoretical basis for linking structure to spectral signatures rests on the principles of quantum mechanics. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is a cornerstone, allowing for the separation of electronic and nuclear motions [2] [4]. This simplification is vital because it permits the calculation of the electronic energy of a molecule for a fixed nuclear configuration, leading to the concept of the potential energy surface.

- Energy Level Quantization: Molecules possess discrete rotational, vibrational, and electronic energy levels. Transitions between these levels, induced by photon absorption or emission, occur at specific frequencies that are characteristic of the molecule's structure [1].

- The Hamiltonian Operator: The total energy of a molecular system is described by its Hamiltonian operator. Solving the Schrödinger equation with this Hamiltonian, ( \hat{H}\psi = E\psi ), yields the wavefunctions (ψ) and energies (E) that define the system's quantum states [2]. The molecular Hamiltonian encapsulates contributions from electrons and nuclei, including their kinetic energies and all Coulombic interactions.

- Transition Intensities: The intensity of a spectral line is proportional to the square of the transition moment integral, ( \langle \psii | \hat{\mu} | \psif \rangle ), where ( \hat{\mu} ) is the dipole moment operator [2]. This means that not only must the energy difference match the photon's energy, but the interaction must also induce a change in the molecule's charge distribution to be observed.

These quantum-resolved calculations allow for the ab initio prediction of spectra, providing a direct link from a posited molecular structure to its expected spectroscopic profile [4].

Decoding Spectral Regions and Their Structural Correlates

Different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum probe distinct types of molecular energy transitions. A comprehensive understanding requires correlating spectral ranges with specific structural information.

Table 1: Spectroscopic Regions and Their Structural Information

| Spectroscopic Region | Wavelength Range | Energy Transition | Key Structural Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave | 1 mm - 10 cm | Rotational | Bond lengths, bond angles, molecular mass distribution [5] |

| Infrared (IR) | 780 nm - 1 mm | Vibrational (Fundamental) | Functional groups, bond force constants, molecular symmetry [1] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) | 780 nm - 2500 nm | Vibrational (Overtone/Combination) | Molecular anharmonicities, quantitative analysis of complex matrices [1] |

| Raman | Varies with laser | Vibrational (Inelastic Scattering) | Functional groups, symmetry, crystallinity, molecular environment [6] |

| Visible/Ultraviolet (UV-Vis) | 190 nm - 780 nm | Electronic | Conjugated systems, chromophores, electronic structure [1] |

Vibrational Spectroscopy: IR and Raman

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy measures the absorption of light that directly excites molecules to higher vibrational energy levels. A photon is absorbed only if its frequency matches a vibrational frequency of the molecule and the vibration induces a change in the dipole moment [1]. Key IR absorptions include:

- O-H Stretch: A broad band around 3200-3600 cm⁻¹, indicative of alcohols and carboxylic acids.

- C=O Stretch: A strong, sharp band around 1700 cm⁻¹, a hallmark of carbonyl groups in ketones, aldehydes, and esters [1].

- N-H Stretch: A sharp or broad band around 3300 cm⁻¹, characteristic of amines and amides.

Raman Spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. The energy shift (Raman shift) between the incident and scattered photons corresponds to the vibrational energies of the molecule [6]. In contrast to IR, a vibration is Raman-active if it induces a change in the polarizability of the molecule. This makes Raman and IR complementary:

- Raman-Sensitive Motions: It is particularly effective for probing symmetrical vibrations, such as:

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for acquiring and interpreting a vibrational spectrum, highlighting the parallel experimental and computational paths that lead to structural assignment.

Diagram 1: Workflow for vibrational spectral analysis.

Electronic Spectroscopy: UV-Vis

UV-Vis spectroscopy probes electronic transitions from the ground state to an excited state. The energy of these transitions provides information about the extent of conjugation and the presence of specific chromophores [1]. For instance:

- A simple alkene (C=C) absorbs around 175 nm.

- A carbonyl (C=O) exhibits an n→π* transition around 280 nm.

- Increasing conjugation, as in polyenes or aromatic systems, shifts the absorption to longer wavelengths (lower energies), a phenomenon known as a bathochromic shift.

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Computational spectroscopy involves a multi-step process to translate a molecular structure into a predicted spectrum. The accuracy of the final result is highly dependent on the choices made at each stage.

Workflow for Calculating Vibrational Frequencies

A robust protocol for simulating IR or Raman spectra involves the following key steps [2]:

Geometry Optimization

- Objective: Find the minimum energy structure on the potential energy surface.

- Method: Typically performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a functional like B3LYP and a basis set such as 6-31G(d). The optimization is considered converged when the maximum force and root-mean-square (RMS) force fall below predefined thresholds (e.g., 0.00045 and 0.00030 Hartrees/Bohr, respectively).

Frequency Calculation

- Objective: Compute the second derivatives of the energy with respect to nuclear coordinates (the Hessian matrix) to obtain harmonic vibrational frequencies.

- Method: Performed at the same level of theory as the optimization. The output includes:

- Harmonic frequencies (in cm⁻¹).

- IR intensities (in km/mol).

- Raman activities (in Å⁴/amu).

- Anharmonic Corrections: For higher accuracy, especially for X-H stretches, anharmonic corrections using Vibrational Perturbation Theory (VPT2) can be applied [2].

Spectrum Simulation

- Objective: Generate a human- or machine-readable spectrum from the computed data.

- Method: Each vibrational frequency is typically represented by a Lorentzian or Gaussian function. A common linewidth (Full Width at Half Maximum, FWHM) of 4-10 cm⁻¹ is applied. The peaks are plotted as intensity (IR or Raman) versus wavenumber.

Key Databases for Validation

Validating computational results against experimental data is crucial. Several curated databases serve as essential resources [7] [8]:

- NIST Chemistry WebBook: Provides access to IR, mass, UV/Vis, and other spectroscopic data for thousands of compounds, serving as a primary reference [7].

- SDBS (Spectral Database for Organic Compounds): An integrated system that includes EI-MS, ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, FT-IR, and Raman spectra [7].

- Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB): A repository for NMR spectroscopic data of biological macromolecules [7].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Spectral Prediction

| Computational Method | Theoretical Cost | Typical Application | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Medium | IR, Raman, NMR, UV-Vis of medium-sized molecules | Good balance of accuracy and cost for many systems; handles electron correlation [2] | Performance depends on functional choice; can struggle with dispersion forces |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Low | Preliminary geometry optimizations | Fast calculation; conceptual foundation for more advanced methods | Neglects electron correlation; inaccurate for bond energies and frequencies |

| MP2 (Møller-Plesset Perturbation) | High | High-accuracy frequency calculations | More accurate than HF for many properties, including vibrational frequencies [2] | Significantly more computationally expensive than DFT |

| Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Very High | Benchmarking for small molecules | "Gold standard" for quantum chemistry; extremely high accuracy [2] | Prohibitively expensive for large systems |

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between a molecule's structure, its resulting energy levels, and the observed spectral signatures, illustrating the core thesis of this guide.

Diagram 2: Logic of structure-spectrum relationship.

For researchers embarking on spectroscopic analysis, a suite of computational tools, databases, and reagents is indispensable.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function / Purpose | Example Providers / Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Method | Predicts molecular geometries, energies, and spectroscopic parameters (frequencies, NMR shifts) [2] | B3LYP, ωB97X-D, M06-2X |

| Vibrational Perturbation Theory (VPT2) | Computational Method | Adds anharmonic corrections to vibrational frequencies, improving accuracy [2] | As implemented in Gaussian, CFOUR |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) | Computational Model | Simulates solvent effects on molecular structure and spectral properties [2] | As implemented in major quantum chemistry packages |

| SDBS Database | Spectral Database | Provides experimental reference spectra (IR, NMR, MS, Raman) for validation [7] | National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Japan |

| NIST WebBook | Spectral Database | Provides critically evaluated data on gas-phase IR, UV/Vis, and other spectra [7] | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CDCl₃) | Research Reagent | Provides an NMR-inactive environment for NMR spectroscopy to avoid signal interference | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Sigma-Aldrich |

| FT-IR Grade Solvents (e.g., CCl₄, CS₂) | Research Reagent | Provides windows in the IR spectrum with minimal absorption for liquid sample analysis [1] | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| LASER Source | Instrument Component | Provides monochromatic, high-intensity light to excite samples for Raman spectroscopy [6] | Nd:YAG (532 nm), diode (785 nm) |

Advanced Applications: Machine Learning and Biomolecules

The field of computational spectroscopy is rapidly evolving with the integration of machine learning (ML). ML models are now being trained on large datasets of molecular structures and their corresponding spectra, enabling near-instantaneous spectral prediction and the inverse design of molecules with desired spectroscopic properties [9]. This paradigm is particularly powerful for accelerating the analysis of complex biomolecular systems.

In drug development, computational spectroscopy provides critical insights:

- Protein-Ligand Interactions: FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy can detect subtle changes in protein secondary structure and ligand binding modes, which can be interpreted with the aid of molecular dynamics simulations and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations [10].

- Metabolite Identification: Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data, when combined with in silico spectral libraries, allows for the rapid identification of metabolites in complex biological fluids, a key task in pharmacokinetic studies [8].

The fundamental link between molecular structure and spectral signatures is both robust and richly informative. Through the principles of quantum mechanics, a molecule's unique architecture imprints itself upon its interaction with light. The advent and maturation of computational spectroscopy have solidified this connection, transforming spectroscopy from a primarily descriptive tool into a predictive and interpretative science. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these core principles is essential for leveraging the full power of spectroscopic data to uncover structural insights, validate molecular models, and drive innovation. The ongoing integration of machine learning and high-performance computing promises to further deepen this integration, making the link between the abstract molecular world and observable spectral data more powerful and accessible than ever.

Molecular spectroscopy, which measures transitions between discrete molecular energy levels, provides a non-invasive window into the structure and dynamics of matter across the natural sciences and engineering [11]. However, the growing sophistication of experimental techniques makes it increasingly difficult to interpret spectroscopic results without the aid of computational chemistry [12]. Computational molecular spectroscopy has thus evolved from a highly specialized branch of quantum chemistry into an essential general tool that supports and often leads innovation in spectral interpretation [11]. This partnership enables the decoding of structural information embedded within spectral data—whether for small organic molecules, biomolecules, or complex materials—through the application of quantum mechanics to calculate molecular states and transitions [11]. The integration of these computational methods has transformed spectroscopy from a technique requiring extensive expert interpretation to a more automated, powerful, and predictive scientific tool [13] [11].

Core Spectroscopic Techniques and Computational Integration

Each spectroscopic technique probes distinct molecular properties, providing complementary insights that, when combined with computational models, offer a comprehensive picture of molecular systems. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these fundamental techniques.

Table 1: Key Spectroscopic Techniques and Their Computational Counterparts

| Technique | Detection Principle | Structural Information | Common Computational Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| IR Spectroscopy [13] | Molecular vibration absorption | Functional groups with dipole moment changes [13] | DFT (e.g., B3LYP) for frequency calculation; vibrational perturbation theory [12] [14] |

| Raman Spectroscopy [13] | Inelastic light scattering | Symmetric bonds and polarizability changes [13] | DFT for predicting polarizability derivatives; similar anharmonic treatments as IR [12] |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy [13] | Electronic transitions | Conjugated systems, π-π* and n-π* transitions [13] | Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) for calculating excitation energies [11] [14] |

| NMR Spectroscopy [13] | Nuclear spin resonance | Atomic-level structure, connectivity, and chemical environment [15] | GIAO method with DFT for chemical shift prediction; molecular dynamics for conformational analysis [14] [16] |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) [13] | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) | Molecular weight and fragmentation patterns [13] | Machine learning (e.g., CNNs, Transformers) for spectrum-to-structure prediction [13] |

Infrared (IR) and Raman Spectroscopy

IR and Raman spectroscopy are vibrational techniques that provide complementary information about molecular symmetry and functional groups. While IR spectroscopy relies on absorption due to dipole moment changes, Raman spectroscopy measures inelastic scattering related to polarizability changes [13]. The computational characterization of these spectra often employs Density Functional Theory (DFT), typically with functionals like B3LYP and basis sets such as 6-311++G(d,p), to calculate vibrational wavenumbers [14]. A critical step involves scaling the theoretical wavenumbers (e.g., by a factor of 0.9614) to account for anharmonicity and basis set limitations, enabling direct comparison with experimental data [14]. For more accurate simulations, methods accounting for anharmonic effects, such as vibrational perturbation theory (VPT2), are employed to model overtones and combination bands, providing a more realistic spectrum [12].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy is a cornerstone technique for determining molecular structure, connectivity, and conformation in solution [15]. It provides atom-specific information through parameters like chemical shifts, coupling constants, and signal intensities [15]. Computationally, the Gauge-Including Atomic Orbital (GIAO) method combined with DFT is the prevailing approach for predicting NMR chemical shifts [14]. The methodology involves optimizing the molecular geometry at a suitable level of theory (e.g., DFT/B3LYP) and then calculating the magnetic shielding constants for each nucleus. These theoretical values are referenced against a standard (like TMS) to produce chemical shifts that can be validated against experimental measurements [14]. NMR's utility extends to studying protein-ligand interactions and protein conformational changes in biopharmaceutical formulation development, often complemented by molecular dynamics simulations [16].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy probes electronic transitions, typically involving the promotion of an electron from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) [11]. These transitions are highly sensitive to the environment and are crucial for reporting on chromophores in applications like solar cells and drug research [11]. The primary computational tool for modeling UV-Vis spectra is Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT), which calculates excitation energies and oscillator strengths [14]. The resulting simulated spectrum, which can be compared to experimental absorbance data, provides insights into the nature of electronic transitions and the frontier molecular orbitals involved, linking directly to the Fukui theory of chemical reactivity [11].

Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Mass spectrometry provides information on molecular weight and fragmentation patterns, making it indispensable for identifying unknown compounds [13]. Unlike the quantum-mechanical methods used for other techniques, computational approaches for MS have been revolutionized by machine learning and deep learning. Early models used convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to extract spectral features, while more recent transformer-based architectures frame spectral analysis as a sequence-to-sequence task, directly generating molecular structures (e.g., in SMILES format) from spectral inputs [13]. For instance, the SpectraLLM model employs a unified language-based architecture that accepts textual descriptions of spectral peaks and infers molecular structure through natural language reasoning, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in structure elucidation [13].

Integrated Computational Workflow

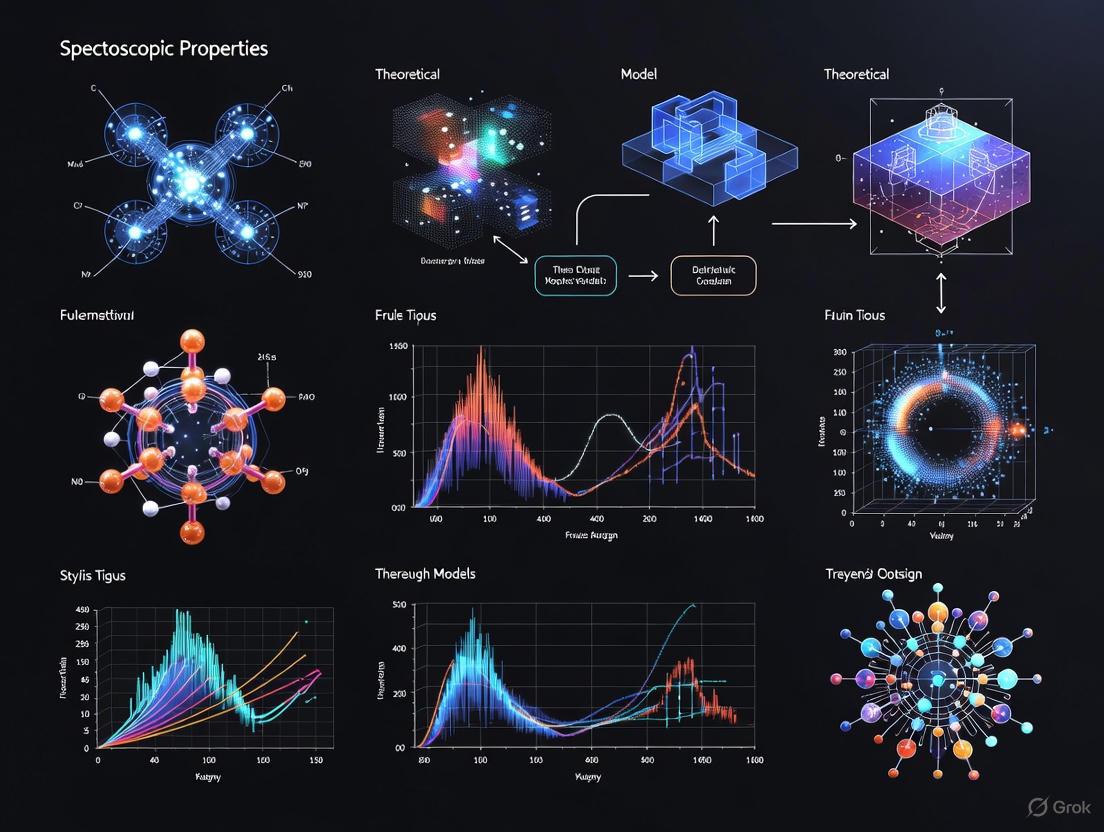

A powerful paradigm in modern research is the combination of multiple spectroscopic techniques within a unified computational framework. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for integrated spectroscopic analysis.

Diagram: Iterative Workflow for Computational Spectroscopy

This iterative process involves using an initial molecular structure as input for computational modeling (e.g., using DFT or molecular dynamics) to predict various spectra [14]. These predictions are systematically compared against collected experimental data. Discrepancies guide the refinement of the molecular model, and the cycle repeats until a consistent, validated molecular model is achieved [11] [14]. This approach is particularly effective for challenging structural elucidations, such as determining the configuration of natural products or characterizing novel synthetic compounds [11].

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Case Study

The following protocol, based on a published study of a chalcone derivative, outlines a typical integrated approach to spectroscopic characterization supported by computational validation [14].

Materials and Synthesis

- Starting Materials: 3-methoxy acetophenone and 4-cyanobenzaldehyde.

- Solvent: Ethanol (20 mL).

- Catalyst: Aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (2 mL, 40%).

- Procedure: Dissolve equimolar quantities of reactants in ethanol. Add the NaOH solution dropwise with stirring for 10 minutes. Continue stirring at room temperature for 5 hours. Monitor reaction completion by TLC (5% ethyl acetate in hexane). Quench the reaction in ice, filter the separated solid, and dry. Purify by recrystallization from a 10% ethyl acetate and hexane mixture to obtain yellow crystals [14].

Spectroscopic Data Acquisition

- FT-IR Spectrum: Acquire using a PerkinElmer spectrometer at room temperature (4000-400 cm⁻¹ range, 100 scans, 2.0 cm⁻¹ resolution) [14].

- FT-Raman Spectrum: Acquire using a BRUKER RFS 27 spectrometer (4000-100 cm⁻¹ range, 100 scans, 2 cm⁻¹ resolution) [14].

- NMR Spectra: Record ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra at 500 MHz in DMSO-d₆ using a JNM-ECZ4005 FT-NMR spectrometer. Use tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Report chemical shifts in δ (ppm) [14].

- UV-Vis Spectrum: Record the absorption spectrum using a spectrometer (e.g., Agilent Cary series) in the 900-100 nm region [14].

Computational Modeling and Analysis

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full optimization of the molecular structure using Gaussian 09w software with the DFT method, B3LYP functional, and 6-311++G(d,p) basis set to find the minimum energy conformation [14].

- Vibrational Analysis: Calculate theoretical vibrational wavenumbers at the same level of theory. Scale the computed wavenumbers by a factor of 0.9614. Assign vibrational modes to observed bands using Potential Energy Distribution (PED) analysis with VEDA 04 software [14].

- NMR Chemical Shift Calculation: Calculate ¹H and ¹³C NMR chemical shifts using the GIAO method with the same DFT functional and basis set. Compare theoretical and experimental shifts for validation [14].

- UV-Vis Spectrum Calculation: Calculate electronic transition energies and oscillator strengths using the TD-DFT method with the same functional and basis set [14].

- Advanced Analyses: Perform additional analyses as needed, including Natural Bond Orbital (NBO), Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO), Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP), and Non-Linear Optical (NLO) property calculations from the optimized structure [14].

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Spectroscopy

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09/16 [14] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Molecular geometry optimization, energy calculation, and spectral property prediction. | DFT calculation of IR vibrational frequencies and NMR chemical shifts [14]. |

| VEDA 04 [14] | Vibrational Analysis Tool | Potential Energy Distribution (PED) analysis for assigning vibrational modes. | Determining the contribution of internal coordinates to the observed FT-IR and Raman bands [14]. |

| Multiwfn [14] | Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer | Analyzing electronic structure properties (ELF, LOL, Fukui functions). | Studying chemical bonding and reactivity sites from the calculated wavefunction [14]. |

| GaussView [14] | Molecular Visualization | Building molecular structures and visualizing computational results. | Preparing input structures for Gaussian and viewing optimized geometries and molecular orbitals [14]. |

| SpectraLLM [13] | AI/Language Model | Multimodal spectroscopic joint reasoning for end-to-end structure elucidation. | Directly inferring molecular structure from single or multiple spectroscopic inputs using natural language prompts [13]. |

Computational molecular spectroscopy has fundamentally shifted from a supporting role in spectral interpretation to a leading force in innovation [11]. The future of this field lies in the deeper integration of experimental and computational methods, creating a digital twin of spectroscopic research that is fully programmable and automated [11]. Key trends shaping this future include the rise of multimodal AI models like SpectraLLM, which can jointly reason across multiple spectroscopic inputs in a shared semantic space, uncovering consistent substructural patterns that are difficult to identify from single techniques [13]. Furthermore, the development of engineered, Turing machine-like spectroscopic databases will enhance the reproducibility and interoperability of spectral data, facilitating machine learning and AI applications [11]. As high-resolution and synchrotron-sourced spectroscopy continue to advance, the tight coupling of measurement and computation will remain paramount for accelerating materials development and drug discovery, ultimately providing a more profound understanding of molecular systems [11].

The Role of Quantum Chemical Calculations in Spectral Prediction

Quantum chemical calculations have become an indispensable tool in the interpretation and prediction of spectroscopic data, creating the specialized field of computational molecular spectroscopy [17]. This field has evolved from a highly specialized branch of theoretical chemistry into a general tool routinely employed by experimental researchers. By solving the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics for molecular systems, these calculations provide a direct link between spectroscopic observables and the underlying electronic and structural properties of molecules. The growing sophistication of experimental spectroscopic techniques makes it increasingly complex to interpret results without the assistance of computational chemistry [17]. This technical guide examines the core methodologies, applications, and protocols that enable researchers to leverage quantum chemical calculations for accurate spectral predictions across various spectroscopic domains.

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Quantum Chemical Methods

The application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems relies on solving the Schrödinger equation, with the Born-Oppenheimer approximation providing the foundational framework that separates nuclear and electronic motions [17] [18]. This separation allows for the calculation of molecular electronic structure, which determines spectroscopic properties.

Table: Fundamental Quantum Chemical Methods for Spectral Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Description | Computational Scaling | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density rather than wavefunction; includes exchange-correlation functionals [19]. | O(N³) | IR, NMR, UV-Vis (via TD-DFT) for medium-sized systems [20] [21]. |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Approximates electron correlation via a single Slater determinant; foundation for correlated methods [19]. | O(N⁴) | Initial geometry optimizations; less used for final spectral prediction. |

| Coupled Cluster (CC) | Includes electron correlation via exponential excitation operators; CCSD(T) is "gold standard" [19]. | O(N⁷) for CCSD(T) | High-accuracy benchmark calculations for small molecules [19]. |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation (MP2) | 2nd-order perturbation treatment of electron correlation [18]. | O(N⁵) | Correction for dispersion interactions in vibrational spectroscopy [17]. |

The selection of an appropriate quantum chemical method involves balancing accuracy requirements with computational cost. For systems with dozens to hundreds of atoms, DFT represents the best compromise, while correlated wavefunction methods like CCSD(T) provide benchmark-quality results for smaller systems where chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal/mol) is essential [19].

Basis Set Considerations

Basis sets constitute a critical component in quantum chemical calculations, representing the mathematical functions used to describe molecular orbitals. The choice of basis set significantly impacts the accuracy of predicted spectroscopic properties [21]. Key considerations include:

- Polarization functions: Essential for accurately describing the deformation of electron density in chemical bonds, making them crucial for predicting vibrational frequencies and NMR chemical shifts [21].

- Diffuse functions: Important for systems with loosely bound electrons, such as anions, excited states, and properties like polarizabilities [21].

- System-specific requirements: Larger basis sets generally improve accuracy but increase computational cost exponentially. Core-valence correlation becomes important for inner-shell spectroscopy [21].

Computational Spectroscopy Methodologies

Vibrational Spectroscopy

The computational prediction of infrared (IR) spectra involves calculating the second derivatives of the energy with respect to nuclear coordinates (the Hessian matrix), which provides vibrational frequencies and normal modes within the harmonic approximation [17] [21]. The standard protocol incorporates:

- Geometry optimization to locate a minimum on the potential energy surface.

- Frequency calculation at the optimized geometry to obtain harmonic frequencies.

- Anharmonic corrections using vibrational perturbation theory (VPT2) for improved accuracy, especially for X-H stretching modes [17].

- Application of scaling factors (0.95-0.98 for DFT) to account for systematic errors from incomplete basis sets, approximate functionals, and the harmonic approximation [21].

The treatment of resonances represents a particular challenge in vibrational spectroscopy, requiring specialized effective Hamiltonian approaches for accurate simulation of experimental spectra [17].

Electronic Spectroscopy

Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) serves as the primary method for predicting UV-Vis spectra, calculating electronic excitation energies and oscillator strengths [21]. The methodology employs the vertical excitation approximation, assuming fixed nuclear positions during electronic transitions [21]. Key considerations include:

- Functional selection: The choice of exchange-correlation functional significantly impacts charge-transfer state accuracy.

- Solvent effects: Incorporation through polarizable continuum models (PCM) or explicit solvent molecules for specific interactions like hydrogen bonding [21].

- Limitations: TD-DFT may perform poorly for charge-transfer states and multi-reference systems, requiring more advanced methods such as complete active space (CAS) approaches [21].

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Quantum chemistry enables the prediction of NMR parameters through the calculation of shielding tensors, which describe the magnetic environment of nuclei [17] [21]. Standard protocols involve:

- Gauge-including atomic orbitals (GIAO) to ensure results are independent of coordinate system choice.

- Relativistic methods such as Zeroth-Order Regular Approximation (ZORA) for heavy elements, where relativistic effects significantly influence chemical shifts [21].

- Solvent incorporation through implicit solvation models or explicit quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) approaches for biomolecular systems [21].

For electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, calculations focus on g-tensors, hyperfine coupling constants, and zero-field splitting parameters, with particular attention to spin-orbit coupling effects in transition metal complexes [17].

Emerging Integration with Machine Learning

Recent advances demonstrate the powerful integration of machine learning (ML) with quantum chemistry to accelerate IR spectral predictions. ML models trained on datasets derived from high-quality quantum chemical calculations can predict key spectral features with significantly reduced computational costs [20]. This approach is particularly valuable for high-throughput screening in drug discovery and materials science, where traditional quantum mechanical methods remain computationally prohibitive for large molecular libraries [20].

Practical Protocols and Workflows

Standard Calculation Workflow

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for predicting spectroscopic properties:

Molecular Structure Preparation

- Generate initial 3D coordinates from chemical intuition or molecular building software.

- Perform preliminary conformational analysis to identify low-energy structures.

Geometry Optimization

- Select appropriate method (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G* for organic molecules).

- Optimize until convergence criteria are met (typical gradient < 10⁻⁵ a.u.).

- Verify stationary point through frequency calculation (no imaginary frequencies for minima).

Spectrum-Specific Property Calculation

- IR/Raman: Calculate harmonic frequencies and intensities; apply anharmonic corrections if needed.

- NMR: Compute shielding tensors using GIAO method; reference to standard compound (e.g., TMS for ¹H/¹³C).

- UV-Vis: Perform TD-DFT calculation with appropriate functional (e.g., ωB97X-D) and diffuse-containing basis set.

Boltzmann Averaging

- For flexible molecules, calculate spectra for all low-energy conformers (within ~3 kcal/mol).

- Apply Boltzmann weighting based on relative energies to produce final composite spectrum [22].

Spectrum Simulation

- Apply appropriate line broadening functions (Lorentzian/Gaussian) to discrete transitions.

- Apply method-specific scaling factors to improve agreement with experiment.

Specialized Protocols for Complex Systems

Table: Advanced Computational Protocols for Challenging Systems

| System Type | Challenge | Recommended Protocol | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Complexes | Multi-reference character, spin-state energetics | CASSCF/NEVPT2 for electronic spectra; DFT with 20% HF exchange for geometry | Include spin-orbit coupling for EPR and optical spectroscopy [17] [21]. |

| Extended Materials | Periodic boundary conditions, band structure | Plane-wave DFT with periodic boundary conditions; hybrid functionals for band gaps | Apply corrections for van der Waals interactions in layered materials [3]. |

| Biomolecules | Solvation effects, conformational flexibility | QM/MM with explicit solvation; conformational averaging | Use fragmentation approaches for NMR of large systems [17]. |

| Chiral Compounds | Vibrational optical activity (VCD, ROA) | Gauge-invariant atomic orbitals for magnetic properties | Ensure robust conformational searching as VCD signs are conformation-dependent [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software Solutions

Table: Key Computational Tools for Spectral Prediction

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Quantum Chemistry Package | General-purpose computational chemistry | Broad method support; user-friendly interface for spectroscopy [20]. |

| ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Package | Advanced electronic structure methods | Efficient DFT/correlated methods; extensive spectroscopy capabilities [22] [19]. |

| SpectroIBIS | Automation Tool | Automated data processing for multiconformer calculations | Boltzmann averaging; publication-ready tables; handles Gaussian/ORCA output [22]. |

| Colour | Python Library | Color science and spectral data processing | Spectral computations, colorimetric transformations, and visualization [23]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational "Reagents" for Spectral Prediction

| Computational Resource | Role/Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | Determine treatment of electron exchange and correlation | B3LYP (general), ωB97X-D (dispersion), PBE0 (solid-state) [19]. |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions for orbital representation | 6-31G* (medium), def2-TZVP (quality), cc-pVQZ (accuracy) [21]. |

| Solvation Models | Simulate solvent effects on molecular properties | PCM (bulk solvent), SMD (improved), COSMO (variants) [21]. |

| Scaling Factors | Correct systematic errors in calculated frequencies | Frequency scaling (0.96-0.98 for DFT), NMR scaling factors [21]. |

Quantum chemical calculations have fundamentally transformed the practice of spectral interpretation and prediction, enabling researchers to connect spectroscopic observables with molecular structure and properties. As methods continue to advance in efficiency and accuracy, and as integration with machine learning approaches matures, computational spectroscopy will play an increasingly central role in molecular characterization across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. The ongoing development of automated computational workflows and specialized software tools ensures that these powerful techniques will remain accessible to both theoretical and experimental researchers, further blurring the boundaries between computation and experiment in spectroscopic science.

The Rise of Machine Learning and AI in Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy, the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation, has entered a transformative era with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). This synergy is revolutionizing how researchers interpret complex spectral data, enabling breakthroughs across biomedical, pharmaceutical, and materials science domains. The intrinsic challenge of spectroscopy lies in extracting meaningful molecular-level information from often noisy, high-dimensional datasets. AI-guided Raman spectroscopy is now overcoming traditional limitations, enhancing accuracy, efficiency, and application scope in pharmaceutical analysis and clinical diagnostics [24]. This whitepaper examines the core computational frameworks, experimental protocols, and emerging applications defining this paradigm shift, providing researchers with a technical foundation for leveraging ML-enabled spectroscopic techniques.

Core ML Architectures in Spectroscopy

The application of ML in spectroscopy spans multiple algorithmic approaches, each suited to specific data characteristics and analytical goals.

Learning Paradigms

- Supervised Learning: Dominates spectral classification and regression tasks, mapping input spectra (X) to known outputs (Y) using functions optimized via loss functions like L1 and L2 norms. These models predict quantum chemical calculation outputs, from primary (e.g., wavefunctions) to secondary (e.g., energy, dipole moments) and tertiary properties (e.g., simulated spectra) [25].

- Unsupervised Learning: Employed for discovering hidden patterns without labeled data, using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction and k-means clustering for sample grouping [26] [25].

- Reinforcement Learning: Learns optimal data processing strategies through environmental interaction and reward feedback, though less commonly applied in spectroscopic analysis [25].

Deep Learning Models

Deep learning architectures automatically identify complex patterns in spectral data with minimal manual intervention [24].

Table 1: Key Deep Learning Architectures in Spectroscopy

| Architecture | Primary Function | Spectroscopic Application |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [24] [26] | Feature extraction from local patterns | Classification of XRD, Raman spectra; identifies edges, textures, and peak patterns [27]. |

| U-Net [26] | Semantic segmentation | Image denoising, hyperspectral data analysis; uses encoder-decoder structure with skip connections. |

| ResNet [26] | Very deep network training | Image segmentation, cell counting; solves vanishing gradient via "skip connections". |

| DenseNet [26] | Maximized feature propagation | Image segmentation, classification; each layer connects to all subsequent layers. |

| Transformers & Attention Mechanisms [24] | Modeling long-range dependencies | Interpretable spectral analysis; improves model transparency. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AI-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Objective: To employ AI-enhanced Raman for drug development, impurity detection, and quality control [24].

Materials:

- Raman spectrometer with laser source

- Pharmaceutical samples (e.g., active ingredients, final products)

- Computational resources for ML model training (e.g., GPU workstations)

- Software libraries (e.g., Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch, scikit-learn)

Procedure:

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra from drug compounds under consistent conditions. For hyperspectral imaging, acquire 5D datasets (X, Y, Z, time, vibrational energy) [26].

- Data Preprocessing: Perform baseline correction, normalize spectral intensities, and augment data to account for experimental variances like peak shifts and intensity fluctuations [27].

- Model Training:

- Train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) or Transformer model on preprocessed spectra.

- Use a synthetic dataset with ~500 unique classes, generating 50-60 training samples per class to simulate variations and prevent overfitting [27].

- The training loss function, typically L1 or L2 norm, is minimized to optimize model parameters [25].

- Model Validation: Test model performance on a blind test set not used during training. Evaluate accuracy in classifying spectra and detecting contaminants.

- Interpretation: Apply attention mechanisms to highlight spectral regions most influential to the model's decision, addressing the "black box" challenge [24].

Technical Note: For Raman spectroscopy, which has an intrinsically weak signal (approximately 1 in 10^6-7 incident photons), Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) using plasmonic nanoparticles or nanostructures can amplify the signal by a factor of 10^4 to 10^11 [28].

Machine Learning for Coherent Raman Scattering (CRS) Microscopy

Objective: To enable high-speed, label-free biomolecular tracking in living systems via CRS microscopy enhanced by ML [26].

Materials:

- Coherent Raman Scattering microscope (CARS or SRS configuration)

- Biological samples (cells, tissues)

- Plasmonic nanoparticles (for SERS applications) [28]

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Perform CRS microscopy (CARS or SRS) to generate hyperspectral, time-lapse, or volumetric datasets.

- Data Denoising: Input noisy CRS images into a U-Net model. The contracting path captures context, while the expanding path enables precise localization, effectively improving SNR without sacrificing imaging speed [26].

- Biomolecular Classification: Utilize a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or DenseNet to classify cells or tissues based on extracted spectroscopic features from denoised images [26].

- Quantitative Analysis: Apply clustering algorithms like k-means or density-based clustering to segment images based on spectral profiles, identifying distinct biomolecular distributions [26].

Computational Spectroscopy and Data Generation

Computational spectroscopy provides the essential link between theoretical simulation and experimental data interpretation, increasingly powered by ML.

Diagram 1: Computational spectroscopy workflow with ML integration.

The workflow illustrates three levels of computational output that can be learned by ML models. Learning secondary outputs (like dipole moments) is often preferred as it retains more physical information compared to learning tertiary outputs (spectra) directly [25]. This approach is vital for creating large, synthetic spectral datasets needed to train robust models, as collecting sufficient experimental data is often costly and time-consuming [27].

Table 2: Synthetic Data Generation for Spectroscopic ML

| Aspect | Traditional Experimental Data | ML-Enhanced Synthetic Data |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Physical measurements on samples | Algorithmic simulation; quantum chemical calculations [25] |

| Throughput | Low; time-consuming and costly | High; 30,000 patterns generated in <15 seconds [27] |

| Diversity & Control | Limited by physical availability; prone to artifacts | Direct manipulation of class features and variances (peaks, intensity, noise) [27] |

| Primary Use | Model validation in real-world conditions | Training robust, generalizable models; benchmarking architectures [27] |

Applications in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences

Precision Immunotherapy and Cancer Diagnostics

AI-enabled Raman spectroscopy acts as a unifying "Raman-omics" platform for precision cancer immunotherapy. It non-invasively probes the tumor immune microenvironment (TiME) by detecting molecular fingerprints of key biomarkers, including lipids, proteins, metabolites, and nucleic acids [28]. ML models analyze these complex Raman spectra to stratify cancer types, identify pathologic grades, and predict patient responses to immunotherapies, moving beyond the limitations of single-omics biomarkers [28].

Drug Development and Quality Control

In pharmaceutical analysis, AI-powered Raman spectroscopy enhances drug development pipelines. Deep learning algorithms automate the detection of complex patterns in noisy data, enabling real-time monitoring of chemical compositions, contaminant detection, and ensuring consistency across production batches to meet stringent regulatory standards [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for AI-Enhanced Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles (Au/Ag) [28] | Signal enhancement for SERS; create intensified electromagnetic fields. | Amplifying weak Raman signals from low-concentration analytes in biological samples [28]. |

| SERS-Active Substrates [28] | Provide consistent, enhanced Raman scattering surface. | Label-free cancer cell identification; fabricated via self-assembly or nanolithography [28]. |

| Synthetic Spectral Datasets [27] | Train and benchmark ML models; simulate experimental artifacts. | Validating neural network performance on spectra with overlapping peaks or noise [27]. |

| PicMan Software [29] | Image analysis for colorimetric and spectral data; extracts RGB, HSV, CIELAB. | Machine vision applications for quality control and color-based diagnostics [29]. |

| Deep Learning Models (CNN, U-Net) [24] [26] | Automated feature extraction and analysis from complex spectral data. | Denoising CRS images; classifying spectroscopic data for pharmaceutical QC [24] [26]. |

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, key challenges remain. Model interpretability is a critical concern, as deep learning models often function as "black boxes" [24]. Research into explainable AI (XAI), including attention mechanisms, is crucial for building trust, especially in clinical and regulatory decision-making [24]. Furthermore, bridging the gap between theoretical simulations and experimental data requires continued development of generalized, transferable ML models that can handle the inconsistencies and batch effects inherent in real-world experimental data [25]. The future will see tighter integration of Raman with other omics platforms, solidifying its role as a central, unifying analytical tool in biomedicine and materials science [28].

The integration of computational chemistry into molecular spectroscopy has revolutionized the way researchers interpret experimental data and design new molecules. For computational results to be actionable in fields like drug development, it is paramount to accurately quantify their uncertainty and understand their limitations. This guide addresses the critical role of error bars—representations of uncertainty or variability—in establishing the chemical interpretability of computational predictions. By framing this discussion within spectroscopic property research, we provide scientists with the methodologies to assess the reliability of their calculations and make informed scientific decisions.

Theoretical Foundations: Accuracy and Interpretability in Computational Spectroscopy

The Core Challenge

In computational spectroscopy, accuracy and interpretability are often seen as conflicting goals, and their reconciliation is a primary research aim [30]. Computational models, such as those based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), provide a powerful tool for interpreting complex experimental spectra and predicting molecular properties. However, these models inherently contain approximations, leading to uncertainties in their predictions. Error bars provide a quantitative measure of this uncertainty, directly influencing the chemical interpretability—the extent to which a result can be reliably used to draw meaningful chemical conclusions.

The Role of Error Bars in Data Interpretation

Error bars on graphs provide a visual representation of the uncertainty or variability of the data points [31]. They give a general idea of the precision of a measurement or computation, indicating how far the reported value might be from the true value.

Their role in chemical interpretability is twofold:

- Assessing Reliability: When comparing the results of different computational methods or experiments, the size of the error bars indicates which result is more reliable. A prediction with smaller error bars suggests a result that is less variable and potentially more precise [31].

- Statistical Significance: Error bars are crucial for making statistical conclusions. For instance, when comparing two computed spectroscopic properties (e.g., the binding energy of a drug candidate), if the error bars of the two data points overlap, the difference between them may not be statistically significant. Conversely, if the error bars do not overlap, the difference is more likely to be statistically significant [31].

It is critical to remember that error bars are a rough guide to reliability and do not provide a definitive answer about whether a particular result is 'correct' [31].

Quantitative Accuracy of Computational Methods

The choice of computational method and basis set directly determines the accuracy of predicted spectroscopic properties. The following tables summarize benchmarked performances of common methodologies, providing a reference for expected errors.

Table 1: Accuracy of Electronic Structure Methods for Spectroscopic Properties

| Method & Basis Set | Vibrational Frequencies (Avg. Error) | Rotational Constants | Anharmonic Corrections | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/pVDZ (B3) [30] | ~10-30 cm⁻¹ | Good | Requires VPT2 | Low | Medium/large molecules, initial screening |

| B2PLYP/pTZ (B2) [30] | ~10 cm⁻¹ [30] | High Accuracy [30] | Requires VPT2 | High | Benchmark quality for semi-rigid molecules |

| CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ [30] | ~10 cm⁻¹ | High Accuracy | Requires VPT2 | Very High | Gold standard for small molecules |

| Last-Generation Hybrid & Double-Hybrid [30] | Rivals B2/CCSD(T) | High Accuracy | Robust VPT2 implementation | Medium-High | General purpose for semi-rigid molecules |

Table 2: Error Ranges for Key Spectroscopic Predictions

| Spectroscopic Property | Computational Method | Typical Error Range | Primary Sources of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Vibrational Frequencies | B3LYP/pVDZ | 20-50 cm⁻¹ | Basis set truncation, incomplete electron correlation, harmonic approximation |

| Anharmonic Vibrational Frequencies (VPT2) | B2PLYP/pTZ | Within 10 cm⁻¹ [30] | Resonance identification, convergence of perturbation series |

| NMR Chemical Shifts | DFT (e.g., B3LYP) | 0.1-0.5 ppm (¹H), 5-10 ppm (¹³C) | Solvent effects, dynamics, relativistic effects (for heavy elements) |

| Rotational Constants | B2PLYP/pTZ | < 0.1% [30] | Equilibrium geometry accuracy, vibrational corrections |

| UV-Vis Excitation Energies | TD-DFT | 0.1-0.3 eV | Functional choice, charge-transfer state description, solvent models |

Methodologies for Uncertainty Quantification

Protocol for Error Bar Determination in Frequency Calculations

A robust methodology for determining error bars on computed vibrational frequencies involves a multi-step process that accounts for systematic and statistical errors.

System Selection and Geometry Optimization:

- Select a set of representative molecules with reliable experimental frequency data.

- Perform a geometry optimization for each molecule using a high-level method (e.g., B2PLYP/pTZ) until convergence criteria are met (e.g., rms force < 1x10⁻⁵ a.u.).

Frequency Calculation:

- Compute the harmonic force field and vibrational frequencies at the optimized geometry.

- Perform a VPT2 calculation to obtain anharmonic frequencies. Special attention must be paid to identifying and correctly handling Fermi resonances, which can be defined by the proximity of vibrational energy levels (e.g., |ωi - ωj - ω_k| < 50 cm⁻¹) and their coupling elements [30].

Error Calculation and Scaling:

- For each vibrational mode i, calculate the error: Errori = νcalc,i - ν_expt,i.

- Compute the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Standard Deviation (SD) across all modes/molecules. The MAE represents the systematic bias, while the SD represents the statistical uncertainty.

- Scaling factors are often applied to correct for systematic method errors. A scaling factor λ is derived from a linear regression of calculated vs. experimental frequencies for a benchmark set. The scaled frequency is νscaled = λ * νcalc.

Error Bar Assignment:

- The final error bar for a predicted frequency can be assigned as ± (MAE + k·SD), where k is a coverage factor (typically 1-2). For a new prediction, the error bar is ν_scaled ± U, where U is the expanded uncertainty.

Workflow for Computational Spectroscopy with Uncertainty

The following diagram visualizes the integrated workflow for predicting spectroscopic properties and quantifying their uncertainty.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Research Reagents

| Item | Function in Computational Spectroscopy |

|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, CFOUR) | Software environment to perform quantum chemical calculations for energy, geometry, and property computations. |

| Density Functionals (e.g., B3LYP, B2PLYP, ωB97X-D) | The "reagent" that approximates the exchange-correlation energy; choice critically impacts accuracy for different properties. |

| Basis Sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, aug-cc-pVTZ, def2-TZVP) | Sets of mathematical functions representing atomic orbitals; size and type (e.g., with diffuse/polarization functions) determine description quality. |

| Solvation Models (e.g., PCM, SMD) | Implicit models that simulate the effect of a solvent on the spectroscopic properties of a solute. |

| Vibrational Perturbation Theory (VPT2) | An algorithm that incorporates anharmonicity into vibrational frequency and intensity calculations, moving beyond the harmonic approximation. |

| Benchmark Datasets | Curated experimental or high-level computational data for specific molecular classes, used to validate methods and derive scaling factors. |

Visualizing Uncertainty in Spectral Predictions

Effectively communicating the uncertainty in a predicted spectrum is crucial for its chemical interpretation. The following diagram illustrates how error bars can be visually integrated into a spectral prediction.

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Hybrid Models and Machine Learning

For larger molecular systems, a practical route to accurate results is provided by hybrid QM/QM' models. These combine accurate quantum-mechanical calculations for "primary" properties (like molecular structures) with cheaper electronic structure approaches for "secondary" properties (like anharmonic effects) [30]. Furthermore, machine learning approaches are being developed to predict optimal scaling factors based on molecular features and to establish a feedback loop between computation and experiment, narrowing down the number of structures with high potential for record efficiency [32] [21].

Environmental and Relativistic Effects

Accounting for the molecular environment is critical. Solvent effects can be modeled using implicit continuum models (e.g., PCM) or by including explicit solvent molecules for specific interactions like hydrogen bonding [21]. For systems containing heavy elements, relativistic effects and spin-orbit coupling become significant and must be incorporated using methods like the Zeroth-Order Regular Approximation (ZORA) to achieve accurate predictions for properties like NMR chemical shifts [21].

Methods and Applications: Implementing Computational Spectroscopy in Research

Computational chemistry has revolutionized the way researchers interpret and predict spectroscopic properties, creating a virtuous cycle between theoretical modeling and experimental validation. This guide examines modern computational workflows that enable researchers to move from molecular structures to predicted spectra and back again, using spectral data to refine structural models. These approaches are particularly valuable in drug development and prebiotic chemistry, where understanding molecular behavior in different environments is crucial [33] [34]. The integration of machine learning with quantum mechanical methods has accelerated this process, making it possible to handle biologically relevant molecules with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency [34] [35]. This guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and practical implementations of these transformative computational approaches, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for spectroscopic property prediction.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Computational Methods

Computational prediction of spectroscopic properties relies on several well-established quantum mechanical methods, each with distinct strengths and limitations for different spectroscopic applications.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency for ground-state properties. It determines the total energy of a molecule or crystal by analyzing the electron density distribution [35]. DFT is particularly valuable for calculating NMR chemical shifts and vibrational frequencies when combined with appropriate basis sets and scaling factors [21]. The coupled-cluster theory (CCSD(T)) represents the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry, offering superior accuracy but at significantly higher computational cost that traditionally limited its application to small molecules [35].

Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) extends ground state DFT to handle excited states and is widely used for predicting UV-Vis spectra [34] [21]. TD-DFT employs linear response theory to compute excitation energies and oscillator strengths, typically under the vertical excitation approximation which assumes fixed nuclear positions during electronic transitions [21]. For more complex systems, machine learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) offer a powerful alternative, enabling the efficient sampling of potential energy surfaces for both ground and excited states with near-quantum accuracy [34].

Accounting for Environmental and Relativistic Effects

Accurate spectroscopic predictions must account for environmental influences, particularly for biological and pharmaceutical applications where solvation effects are significant. Implicit solvent models like the polarizable continuum model (PCM) simulate bulk solvent effects on electronic spectra, while explicit solvent molecules are necessary for modeling specific solute-solvent interactions such as hydrogen bonding [21]. For large biomolecular systems, QM/MM (quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics) simulations combine quantum mechanical treatment of the solute with classical treatment of the environment [21].

For systems containing heavy elements, relativistic effects and spin-orbit coupling become crucial considerations. The zeroth-order regular approximation (ZORA) incorporates scalar relativistic effects, while two-component relativistic methods account for spin-orbit coupling in electronic structure calculations, significantly influencing fine structure in atomic spectra and molecular multiplet splittings [21].

Table 1: Computational Methods for Spectroscopic Predictions

| Method | Best For | Key Considerations | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT | NMR chemical shifts, vibrational frequencies, ground state geometries | Choice of functional and basis set critical; systematic errors require scaling factors | Moderate |

| CCSD(T) | High-accuracy benchmark calculations | "Gold standard" but limited to small molecules (~10 atoms) | Very High |

| TD-DFT | UV-Vis spectra, excitation energies | Poor for charge transfer states; accuracy depends on functional | Moderate-High |

| MLIPs | Large systems, solvent effects, dynamics | Requires training data; efficient once trained | Low (after training) |

Computational Workflows and Methodologies

Unsupervised Workflow for Gas-Phase Molecules

For gas-phase molecules where intrinsic stereoelectronic effects can be disentangled from environmental influences, automated workflows provide reliable equilibrium geometries and vibrational corrections. The Pisa composite schemes (PCS) workflow integrates with standard computational chemistry packages like Gaussian and efficiently combines vibrational correction models including second-order vibrational perturbation theory (VPT2) [33].

This approach is particularly valuable for medium-sized molecules (up to 50 atoms) where relativistic and static correlation effects can be neglected. The workflow has been demonstrated on prebiotic and biologically relevant compounds, successfully handling both semi-rigid and flexible species, with proline serving as a representative flexible case [33]. For open-shell systems, the workflow has been validated against extensive isotopic experimental data using the phenyl radical as a prototype [33].

The following diagram illustrates this automated workflow:

MLIP Workflow for Solvated Systems

For solvated molecules like the fluorescent dye Nile Red, the Explicit Solvent Toolkit for Electronic Excitations of Molecules (ESTEEM) provides a comprehensive workflow that combines machine learning with quantum chemistry. This approach is particularly valuable for capturing specific solute-solvent interactions such as hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking that are beyond the capabilities of implicit solvent models [34].

The workflow employs iterative active learning techniques to efficiently generate MLIPs, balancing the competing demands of long timescales, high accuracy, and reasonable computational walltime. The methodology compares distinct MLIPs for each adiabatic state, ground state MLIPs with delta-ML for excitation energies, and multi-headed ML models [34]. By incorporating larger solvent systems into training data and using delta models to predict excitation energies, this approach enables accurate prediction of UV-Vis spectra with accuracy equivalent to time-dependent DFT at a fraction of the computational cost [34].

Multi-Task Electronic Hamiltonian Network (MEHnet)

The MEHnet architecture represents a significant advancement in computational efficiency by utilizing a single model to evaluate multiple electronic properties with CCSD(T)-level accuracy. This E(3)-equivariant graph neural network uses nodes to represent atoms and edges to represent bonds, with customized algorithms that incorporate physics principles directly into the model [35].

Unlike traditional approaches that require multiple models to assess different properties, MEHnet simultaneously predicts dipole and quadrupole moments, electronic polarizability, optical excitation gaps, and infrared absorption spectra. After training on small molecules, the model can be generalized to larger systems, potentially handling thousands of atoms compared to the traditional limits of hundreds of atoms with DFT and tens of atoms with CCSD(T) [35].

Table 2: Workflow Comparison and Applications

| Workflow | System Type | Key Features | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pisa Composite Scheme [33] | Gas-phase molecules (up to 50 atoms) | Unsupervised, automated, combines PCS with VPT2 | High-resolution rotational spectroscopy |

| ESTEEM/MLIP [34] | Solvated molecules | Active learning, explicit solvent, delta-ML for excitations | UV-Vis absorption/emission in multiple solvents |

| MEHnet [35] | Organic molecules, expanding to heavier elements | Multi-task learning, CCSD(T) accuracy, single model for multiple properties | Known hydrocarbon molecules vs experimental data |

Performance Analysis and Optimization

Accuracy and Efficiency Considerations

The performance of computational spectroscopy workflows depends critically on method selection and parameter optimization. For vibrational spectroscopy, scaling factors adjust calculated frequencies to account for systematic errors in computational methods, with different factors required for different levels of theory and basis sets [21]. Basis set selection significantly influences accuracy, with larger basis sets generally improving results but increasing computational cost. Polarization functions are crucial for describing electron distribution in chemical bonds, while diffuse functions are important for systems with loosely bound electrons such as anions and excited states [21].

For electronic spectroscopy, the incorporation of environmental effects can dramatically improve accuracy. Research has demonstrated that index transformations of spectral data, particularly three-band indices (TBI), can enhance predictive performance for soil properties, with R² values improving by up to 0.30 for pH prediction compared to unprocessed data [36]. Similar principles apply to molecular spectroscopy, where pre-processing and feature selection techniques can significantly improve model performance.

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Recent advances in quantum computing offer promising avenues for further accelerating spectroscopic predictions. New approaches to simulating molecular electrons on quantum computers utilize neutral atom platforms with multi-qubit gates that perform specific computations far more efficiently than traditional two-qubit gates [37]. While current error rates remain challenging, these approaches require only modest improvements in coherence times to become viable for practical applications [37].

For complex systems, feature selection approaches like recursive feature elimination (RFE) and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) help reduce data dimensionality and improve model reliability [36]. Calibration models using partial least squares regression (PLSR) and LASSO regression have demonstrated significant improvements in predicting molecular properties when combined with appropriate pre-processing techniques [36].

Implementation Tools and Protocols

Computational Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of computational spectroscopy workflows requires familiarity with a range of software tools and methodological approaches. The following table outlines essential components of the computational chemist's toolkit for spectroscopic predictions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Spectroscopy

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Packages | Gaussian, AMS/DFTB, PRIMME | Core quantum mechanical calculations for energies, geometries, and properties |

| Solvation Tools | AMBERtools, PackMol | System preparation, explicit solvation, molecular dynamics |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | ESTEEM, MEHnet | Training MLIPs, multi-property prediction, active learning |

| Analysis Methods | PLSR, LASSO, RFE | Feature selection, model calibration, dimensionality reduction |

| Specialized Techniques | Davidson diagonalization, VPT2, ZORA | Handling excited states, vibrational corrections, relativistic effects |

Experimental Protocol for Solvated System Spectroscopy

For researchers implementing the ESTEEM workflow for solvated systems, the following detailed protocol provides a methodological roadmap:

System Preparation Phase: Begin by obtaining initial geometries for solute and solvent molecules, either from user input or databases like PubChem [34]. Optimize these geometries first in vacuum, then in each solvent of interest using implicit solvent models at the specified level of theory (e.g., DFT with appropriate functional and basis set).

Explicit Solvation and Equilibration: Use tools like PackMol or AMBERtools to surround optimized solute geometries with explicit solvent molecules [34]. Perform a four-stage molecular dynamics equilibration: (1) constrained-bond heating to target temperature (NVT ensemble), (2) density equilibration (NPT ensemble), (3) unconstrained-bond equilibration (NVT ensemble), and (4) production MD with snapshot collection.

Active Learning Loop: From MD snapshots, generate clusters of appropriate size for quantum chemical calculations. Use these to initiate an active learning process where MLIPs are iteratively trained and evaluated, with new training points selected based on regions of high uncertainty or error [34].

Spectra Prediction and Validation: Use the trained MLIPs to predict absorption and emission spectra, comparing directly with experimental data where available. For the Nile Red system, this approach has demonstrated accuracy equivalent to TD-DFT with significantly reduced computational cost [34].

Workflow Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate computational workflow depends on the specific system and research question:

- For gas-phase molecules where intrinsic properties are of interest, the unsupervised Pisa composite scheme workflow provides excellent accuracy with minimal manual intervention [33].

- For solvated systems where specific solvent-solute interactions dominate, MLIP-based approaches like ESTEEM offer the best balance of accuracy and computational efficiency [34].

- For high-accuracy benchmark calculations on relatively small systems, MEHnet provides CCSD(T)-level accuracy for multiple properties simultaneously [35].

- For systems with heavy elements, methods incorporating relativistic corrections like ZORA are essential for accurate predictions [21].

As computational power grows and algorithms advance, researchers can increasingly tackle more complex systems, uncovering new insights into molecular properties and their spectroscopic signatures [21]. The integration of machine learning with quantum chemistry represents a particularly promising direction, potentially enabling the accurate treatment of entire periodic table at CCSD(T) level accuracy but with computational costs lower than current DFT approaches [35].

Spectroscopy, the investigation of matter through its interaction with electromagnetic radiation, is a cornerstone technique in diverse scientific fields, including biology, materials science, and drug development [38]. The analysis of spectroscopic data enables the qualitative and quantitative characterization of samples, making it indispensable for molecular structure elucidation and property prediction [39]. However, the interpretation of complex spectral data presents a significant challenge, traditionally requiring extensive expert knowledge and theoretical simulations.

The advent of machine learning (ML) has revolutionized this landscape. ML has not only enabled computationally efficient predictions of electronic properties but also facilitated high-throughput screening and the expansion of synthetic spectral libraries [38]. Among the various ML approaches, deep learning architectures—particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and Transformers—have emerged as powerful tools for tackling the unique challenges of spectroscopic data. These architectures are strengthening theoretical computational spectroscopy and beginning to show great promise in processing experimental data [38]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core architectures, framing them within the broader research objective of understanding spectroscopic properties with computational models.

Core Machine Learning Architectures in Spectroscopy

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs are a class of deep neural networks specifically designed to process data with a grid-like topology, such as 1D spectral signals or 2D spectral images. Their core operations are convolutional layers that apply sliding filters (kernels) to extract hierarchical local features.

- Architecture and Operation: A typical CNN for 1D spectroscopy consists of stacked convolutional layers that detect local patterns (e.g., peaks, slopes) from spectral inputs. Each layer is followed by a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU) and often a pooling operation to reduce dimensionality and create translational invariance. Final layers are typically fully connected for classification or regression tasks [26].

- Spectroscopic Applications: CNNs excel in tasks that involve recognizing local spectral patterns. In Coherent Raman Scattering (CRS) microscopy, CNN-based architectures like U-Net, ResNet, and DenseNet are employed for image segmentation, denoising, and classification tasks [26]. Their ability to learn hierarchical features directly from raw spectral data eliminates the need for manual feature engineering, which is a significant advantage over traditional multivariate methods [40].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs operate directly on graph-structured data, making them naturally suited for representing molecules, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Architecture and Operation: GNNs learn node representations through a message-passing mechanism, where nodes aggregate feature information from their local neighbors. This process is repeated over multiple layers, allowing nodes to capture information from increasingly larger receptive fields within the graph [41]. This is particularly powerful for capturing the topological structure of molecules.

- Spectroscopic Applications: GNNs have become a dominant architecture for predicting mass spectra from molecular structures (molecule-to-spectrum tasks). Models like FIORA, GRAFF-MS, and MassFormer leverage GNNs to predict fragmentation patterns and spectral properties by learning from molecular graphs [42]. Their inductive bias towards graph data allows them to model molecular substructures and their influence on spectral outcomes effectively. In medical image segmentation related to spectroscopy, pure GNN-based architectures like U-GNN have been shown to surpass Transformer-based models in segmenting complex tumor structures, achieving a 6% improvement in Dice Similarity Coefficient and an 18% reduction in Hausdorff Distance [43].

Transformers

Transformers, originally developed for natural language processing, utilize a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of all elements in a sequence when processing each element. This allows them to capture long-range dependencies and global context effectively.

- Architecture and Operation: The self-attention mechanism computes a weighted sum of values for each element in an input sequence, where the weights (attention scores) are derived from the compatibility between the element's query and the keys of all other elements. While powerful, the standard self-attention mechanism has quadratic computational complexity with respect to sequence length, which can be a limitation for long sequences [41].