Coupled Cluster vs. DFT: A Practical Guide to Accuracy, Cost, and Application in Computational Chemistry and Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Coupled Cluster (CC) theory, particularly CCSD(T), the 'gold standard' of quantum chemistry, and the more computationally efficient Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Coupled Cluster vs. DFT: A Practical Guide to Accuracy, Cost, and Application in Computational Chemistry and Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between Coupled Cluster (CC) theory, particularly CCSD(T), the 'gold standard' of quantum chemistry, and the more computationally efficient Density Functional Theory (DFT). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of both methods, practical applications, strategies for balancing cost and accuracy, and rigorous validation benchmarks. We highlight emerging trends, including machine learning potentials and local correlation methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T), which are bridging the accuracy-speed gap and enabling high-fidelity simulations for biomolecular systems.

Coupled Cluster and DFT Explained: Understanding Quantum Chemistry's Accuracy Benchmarks

In the quest for predictive computational chemistry, the coupled-cluster method with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations, known as CCSD(T), has established itself as the undisputed "gold standard" for calculating molecular energies and properties. This prestigious status stems from its systematic approach to solving the Schrödinger equation and its renowned ability to achieve chemical accuracy—defined as an error margin of approximately 1 kcal/mol (or 0.05 eV) relative to experimental values. While Density Functional Theory (DFT) remains the workhorse for routine calculations on large systems due to its favorable computational cost, its accuracy is inherently limited by approximations in the exchange-correlation functional. In contrast, CCSD(T) provides a more rigorous, wavefunction-based framework whose accuracy can be systematically improved in a non-empirical manner, making it the benchmark against which other quantum chemical methods are measured [1] [2].

The critical importance of CCSD(T) extends across numerous scientific domains. In drug development, accurate prediction of binding energies and molecular properties can significantly accelerate the design of novel pharmaceuticals. In materials science, it enables the reliable prediction of properties for new energy storage materials and catalysts. Furthermore, CCSD(T) naturally incorporates long-range van der Waals (vdW) interactions, which are crucial for understanding molecular crystals, supramolecular chemistry, and many biological processes—interactions that often remain challenging for standard DFT functionals [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CCSD(T) versus alternative computational methods, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and development professionals in their selection of computational protocols.

Theoretical Background: CCSD(T) and Alternative Methods

The Quantum Chemical Hierarchy

Computational quantum chemistry methods form a hierarchy of increasing accuracy and computational cost, with CCSD(T) occupying the top tier for single-reference systems.

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Theory: Serves as the starting point for more advanced methods. It considers electron exchange but neglects electron correlation entirely, leading to typically large errors in energy predictions.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Incorporates electron correlation approximately via an exchange-correlation functional. Its popularity stems from its favorable cost-to-accuracy ratio, but results are highly dependent on the chosen functional, and there is no systematic path to improve accuracy to the CCSD(T) level [3].

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2): An ab initio method that includes electron correlation through second-order perturbation theory. It is less expensive than CCSD(T) but can be unreliable for systems with significant static correlation.

- Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory: A sophisticated wavefunction-based method that systematically accounts for electron correlation. The cluster operator is expressed as ( T = T1 + T2 + T3 + \cdots ), where ( T1 ), ( T2 ), and ( T3 ) represent single, double, and triple excitations, respectively. The CCSD method includes all single and double excitations.

- CCSD(T): The "gold standard" method that builds upon CCSD by adding a perturbative treatment of connected triple excitations, denoted by (T). This addition is crucial for achieving high accuracy, particularly for reaction energies, barrier heights, and non-covalent interactions. The formal computational cost of canonical CCSD(T) scales as ( O(N^7) ), where ( N ) is the number of orbitals, making it prohibitively expensive for large systems [1] [2].

The Concept of Chemical Accuracy

The term "chemical accuracy" (≈1 kcal/mol or 0.05 eV) is not arbitrary; it represents an energy threshold that allows for the quantitative prediction of chemical phenomena. Achieving this accuracy enables researchers to:

- Reliably compute reaction enthalpies and activation barriers.

- Predict accurate binding affinities for drug design.

- Calculate spectroscopic constants that match experimental observations. CCSD(T) is one of the few methods that can consistently deliver this level of precision across a wide range of chemical systems, provided adequate basis sets are used and the system's electronic structure is well-described by a single reference determinant [1].

Performance Comparison: CCSD(T) vs. DFT and Other Methods

Quantitative benchmarks against accurate experimental data or high-level theoretical references consistently demonstrate the superior performance of CCSD(T).

Benchmarking Dipole Moments and Molecular Properties

A 2023 benchmark study on diatomic molecules revealed that while CCSD(T) generally yields accurate dipole moments, disagreements with experiment in some cases could not be satisfactorily explained by relativistic or multi-reference effects. This finding underscores a critical point: accurate prediction of energy and geometry does not automatically guarantee equivalent accuracy for other electron density-derived properties, highlighting the need for specific property benchmarks [4].

Benchmarking Binding Strengths in Metal-Nucleic Acid Complexes

A comprehensive 2023 study generated a complete CCSD(T)/CBS (complete basis set) data set for the binding energies of 64 complexes involving group I metals and nucleic acid components. This data set was used to assess the performance of 61 different DFT functionals.

Table 1: Performance of Select DFT Functionals vs. CCSD(T)/CBS for Metal-Nucleic Acid Binding Energies [5]

| Functional Type | Specific Functional | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrid | mPW2-PLYP | < 1.0 kcal/mol | Best overall performance |

| Range-Separated Hybrid (RSH) | ωB97M-V | < 1.0 kcal/mol | Top-tier performance, robust |

| Meta-GGA | TPSS, revTPSS | ~1.0 kcal/mol | Recommended computationally efficient alternatives |

| Popular Hybrid | B3LYP (no dispersion correction) | Not among top performers | Performance ambiguous for these systems |

The study concluded that the best-performing functionals, such as mPW2-PLYP and ωB97M-V, could approach CCSD(T) accuracy with errors below 1.0 kcal/mol. However, functional performance was dependent on the metal identity and nucleic acid binding site, with errors generally increasing for heavier metals [5].

Benchmarking Ionization Potentials

A 2024 benchmark study on 230 ionized states in 70 molecules (including small organics, organic acceptors, and nucleobases) highlighted the critical role of triple excitations. The study found that while pCCD-based methods are efficient, the absence of dynamical correlation led to unacceptably large errors of approximately 1.5 eV in ionization potentials (IPs). Incorporating dynamical correlation via frozen-pair coupled cluster methods brought errors within chemical accuracy, underscoring the necessity of the correlation treatment inherent in methods like CCSD(T) for properties like IPs [6].

General Performance Trends

The table below summarizes the typical performance of various quantum chemical methods across different chemical properties, as evidenced by multiple benchmark studies.

Table 2: Overall Performance Summary of Quantum Chemical Methods

| Method | Typical Cost Scaling | Typical Performance & Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | ( O(N^7) ) | "Gold Standard." Achieves chemical accuracy for energies of single-reference systems. Prohibitively expensive for large systems. |

| DFT | ( O(N^3)-O(N^4) ) | Highly variable. Performance depends critically on the functional. Can approach CCSD(T) accuracy for some properties with top-tier functionals (e.g., ωB97M-V), but can fail systematically for others (e.g., dispersion, bond breaking). |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | ( O(N^5) ) or higher | Often among the best DFT methods, sometimes approaching CCSD(T) accuracy, but with significantly increased cost. |

| Local CCSD(T) | ~( O(N^1) ) | Retains most of the accuracy of canonical CCSD(T) for large systems. Errors can grow with system size but can be mitigated with extrapolation techniques [7]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials | ~( O(N^1) ) | Can reproduce CCSD(T) accuracy at force-field speed after training. Requires extensive training data. |

Methodological Protocols: Achieving Reliable CCSD(T) Results

Standard CCSD(T) Protocol for Molecular Systems

To obtain benchmark-quality results, a rigorous computational protocol must be followed.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular structure at a lower level of theory, such as DFT with a medium-sized basis set (e.g., def2-SVP).

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Perform a CCSD(T) energy calculation on the optimized geometry. The key is to combine it with a large basis set to minimize basis set superposition error (BSSE).

- Basis Set Selection: Use a correlation-consistent basis set (e.g., cc-pVXZ, where X=D,T,Q,...). To approximate the complete basis set (CBS) limit, a common strategy is to perform calculations with two consecutive basis sets (e.g., cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ) and extrapolate the energy to the CBS limit [5].

- Accounting for Triple Excitations: Ensure the (T) correction is included. Calculations show that this perturbative triple excitation contribution is essential for achieving chemical accuracy [6].

Advanced Protocols: Local Correlation and Extrapolation

For larger systems, canonical CCSD(T) is not feasible. Local approximations like DLPNO-CCSD(T) (Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital) enable linear-scaling calculations.

- DLPNO-CCSD(T) Workflow: This method, as implemented in programs like ORCA, uses thresholds (e.g.,

TCutPNO) to truncate the correlation space for each electron pair, dramatically reducing cost [7]. - CPS Extrapolation: A two-point extrapolation scheme (e.g., CPS(6/7)) can be used to approach the complete PNO space limit, drastically reducing the local approximation error. This is particularly important for large systems where the absolute error can grow, ensuring benchmark-quality relative energies [7]. The formula for extrapolation is:

( E{CPS(X/Y)} = \frac{10^{-Y} EX - 10^{-X} EY}{10^{-Y} - 10^{-X}} )

where ( EX ) and ( E_Y ) are correlation energies obtained with

TCutPNO = 10^-Xand10^-Y(Y = X+1), respectively.

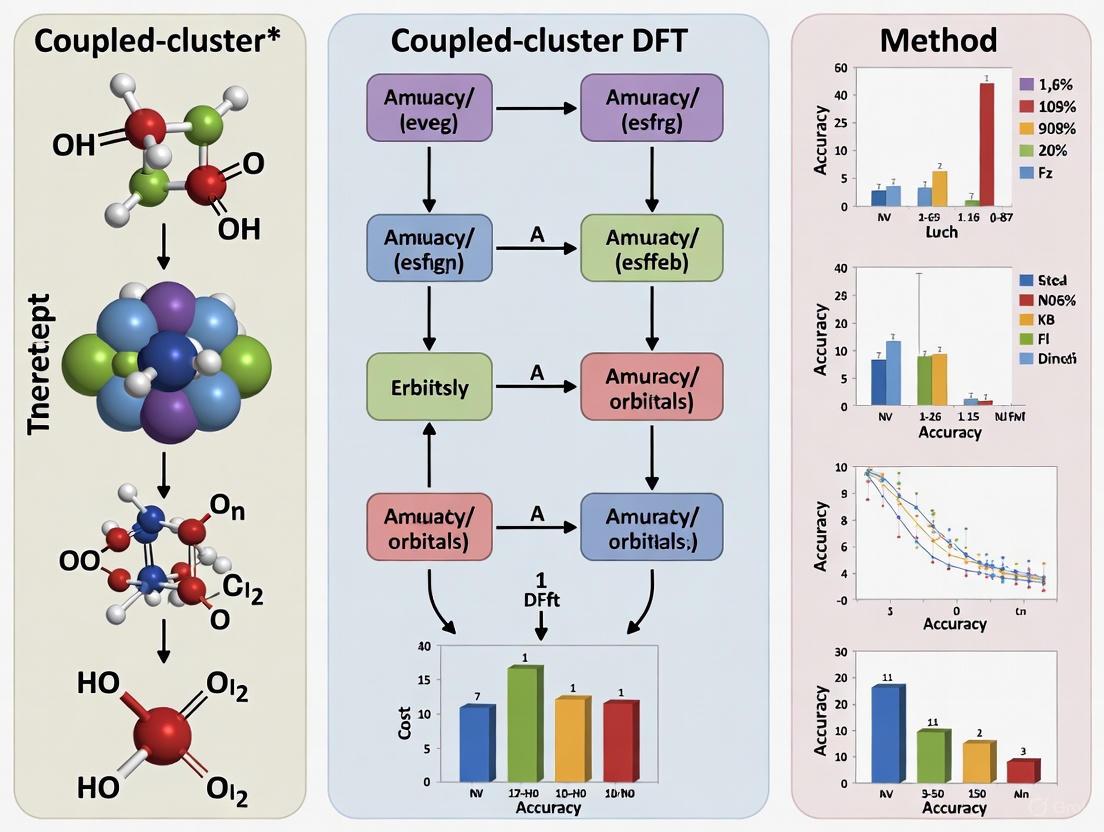

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these protocols and their role in achieving high accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

This section details key software, methods, and computational "reagents" essential for performing high-accuracy coupled-cluster and DFT calculations.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for High-Accuracy Quantum Chemistry

| Tool / Solution | Category | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA | Software Package | A versatile quantum chemistry package with robust implementations of both DFT and highly correlated methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T). [8] [7] | Performing single-point energy calculations and geometry optimizations for systems of varying sizes. |

| MOLPRO | Software Package | A comprehensive quantum chemistry program specializing in high-accuracy ab initio methods, including local CCSD(T)-F12. [2] | Generating benchmark CCSD(T) reference data for training machine learning potentials. |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Reference Method | Provides benchmark-quality energies by combining CCSD(T) with a complete basis set extrapolation. Serves as the reference for evaluating other methods. [5] | Creating trusted data sets for assessing DFT functional performance, as in metal-nucleic acid studies. |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | Approximate Method | A local approximation to CCSD(T) that enables the application of coupled-cluster accuracy to large systems (hundreds of atoms). [7] | Calculating accurate interaction energies in protein-ligand complexes or large water clusters. |

| ANI-1ccx | Machine Learning Potential | A neural network potential trained to approach CCSD(T)/CBS accuracy, billions of times faster than the direct quantum calculation. [1] | Running long molecular dynamics simulations with coupled-cluster fidelity for drug-like molecules. |

| ωB97M-V | DFT Functional | A robust range-separated hybrid meta-GGA functional that often ranks among the top DFT methods in benchmarks. [5] | A reliable DFT choice for geometry optimizations or single-point energies when CCSD(T) is infeasible. |

| def2 Basis Sets | Basis Set | A family of efficient, widely-used Gaussian-type basis sets (e.g., def2-SVP, def2-TZVPP) for quantum chemical calculations. [5] [8] | Standard choice for DFT and correlated calculations, offering a balance of accuracy and cost. |

CCSD(T) rightfully maintains its status as the gold standard of quantum chemistry due to its non-empirical formulation and demonstrated ability to achieve chemical accuracy for a wide range of molecular properties. While its computational expense limits its direct application to large systems, the development of local correlation methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T) and powerful extrapolation techniques are progressively extending its reach. Furthermore, the emergence of machine-learning potentials trained on CCSD(T) data, such as ANI-1ccx, represents a paradigm shift, offering the prospect of CCSD(T) accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [1] [2].

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the practical path forward involves a multi-level approach. CCSD(T) should be employed to generate benchmark data for key model systems and to validate the performance of more efficient methods like DFT for specific chemical problems of interest. For high-throughput screening or studies of very large systems, top-performing DFT functionals (e.g., ωB97M-V, mPW2-PLYP) or machine-learning potentials offer the best compromise between accuracy and computational feasibility. As these technologies continue to mature, the gold standard of CCSD(T) will become increasingly accessible, empowering scientists to design and discover new molecules and materials with unprecedented precision and confidence.

Predicting the behavior of electrons in molecules and materials represents one of the most fundamental challenges in computational chemistry and physics. Two dominant theoretical frameworks have emerged to solve the quantum many-body problem: density functional theory (DFT) and coupled cluster (CC) theory. While DFT leverages the electron density as its fundamental variable, coupled cluster theory employs a sophisticated wavefunction-based approach centered on an exponential ansatz that guarantees size extensivity—a critical property ensuring energy scales correctly with system size. The mathematical formulation of this ansatz, ( |\Psi\rangle = e^{T}|\Phi0\rangle ), where ( T ) is the cluster operator and ( |\Phi0\rangle ) is the reference wavefunction, represents the cornerstone of CC theory's theoretical elegance and accuracy [9].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing specifically on their performance characteristics, accuracy limitations, and practical applicability across various chemical systems. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding the precise capabilities and trade-offs between these methods is crucial for selecting appropriate computational tools for predicting molecular properties, binding affinities, and reaction mechanisms. We present experimental data from recent benchmark studies to illuminate the conditions under which each method excels or falls short, providing a evidence-based foundation for methodological selection in scientific research.

Mathematical Foundations of Coupled Cluster Theory

The Exponential Ansatz and Cluster Operators

The coupled cluster wavefunction is built upon a sophisticated exponential operator acting on a reference wavefunction (typically Hartree-Fock): ( |\Psi{CC}\rangle = e^{T}|\Phi0\rangle ) [9]. This exponential form guarantees the size extensivity of the method, meaning the energy scales correctly with the number of particles, unlike truncated configuration interaction approaches [9].

The cluster operator ( T ) is expanded as a sum of excitation operators: ( T = T1 + T2 + T3 + \cdots ), where ( T1 ) represents all single excitations, ( T_2 ) all double excitations, and so forth [9]. The expansion can be written as:

- ( T1 = \sum{i}\sum{a}t{a}^{i}\hat{a}^{a}\hat{a}_{i} )

- ( T2 = \frac{1}{4}\sum{i,j}\sum{a,b}t{ab}^{ij}\hat{a}^{a}\hat{a}^{b}\hat{a}{j}\hat{a}{i} )

- ( Tn = \frac{1}{(n!)^{2}}\sum{i1,i2,\ldots,in}\sum{a1,a2,\ldots,an}t{a1,a2,\ldots,an}^{i1,i2,\ldots,in}\hat{a}^{a1}\hat{a}^{a2}\ldots\hat{a}^{an}\hat{a}{in}\ldots\hat{a}{i2}\hat{a}{i_1} )

Here, ( t ) amplitudes are unknown parameters determined by solving the coupled cluster equations, ( \hat{a}^{a} ) and ( \hat{a}_{i} ) are creation and annihilation operators, and indices ( i,j,\ldots ) (( a,b,\ldots )) refer to occupied (unoccupied) orbitals in the reference wavefunction [9].

The exponential operator ( e^{T} ) can be expanded as a Taylor series: ( e^{T} = 1 + T + \frac{1}{2!}T^2 + \frac{1}{3!}T^3 + \cdots ), which introduces connected excitations of various orders [9]. In practice, the cluster operator must be truncated to make computations feasible.

Common Truncation Schemes and Computational Scaling

The following table summarizes the most common truncation levels in coupled cluster theory and their computational scaling:

Table 1: Coupled cluster methods and their computational characteristics

| Method | Excitation Level | Included Excitations | Computational Scaling | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD | Singles & Doubles | ( T1 + T2 ) | ( O(N^6) ) | Small molecules, initial wavefunction refinement |

| CCSD(T) | Singles, Doubles & perturbative Triples | ( T1 + T2 + \text{(perturbative } T_3\text{)} ) | ( O(N^7) ) | "Gold standard" for chemical accuracy in small systems |

| CCSDT | Singles, Doubles & Triples | ( T1 + T2 + T_3 ) | ( O(N^8) ) | High-accuracy studies of electronic degeneracies |

| CCSDTQ | Up to Quadruples | ( T1 + T2 + T3 + T4 ) | ( O(N^{10}) ) | Ultra-high accuracy for small systems |

The computational scaling illustrates why CCSD(T) represents the best compromise between accuracy and computational cost for many applications, earning its designation as the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry [10] [11]. However, even CCSD(T) becomes prohibitively expensive for systems exceeding approximately 50 atoms, necessitating approximations for larger biological systems [3] [10].

Diagram 1: The coupled cluster ansatz and common truncation schemes. The exponential operator generates excitations of various orders, which are typically truncated to make computations feasible. CCSD(T) represents the best compromise between accuracy and computational cost.

Density Functional Theory: A Practical Alternative

Fundamental Principles and Approximations

Density functional theory takes a fundamentally different approach by using the electron density ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) as the basic variable, rather than the many-electron wavefunction [12]. This approach is justified by the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all molecular properties [12].

The practical implementation of DFT occurs through the Kohn-Sham equations, which introduce a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that produces the same density as the real interacting system [13] [12]. The critical challenge in DFT is the exchange-correlation functional, for which exact forms are unknown, necessitating approximations:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Uses the exchange-correlation energy of a uniform electron gas.

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates both the local density and its gradient.

- Meta-GGA: Adds the kinetic energy density for improved accuracy.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange.

- Double Hybrids: Incorporate both Hartree-Fock exchange and perturbative correlation contributions.

The computational scaling of DFT is typically ( O(N^3) ) for local and semi-local functionals, though hybrid functionals have increased computational demands [3]. This favorable scaling enables applications to systems containing thousands of atoms, far beyond the practical limits of coupled cluster methods [13].

Comparative Benchmark Studies: Methodological Performance

Hydrogen Bonding Interactions

Hydrogen bonding represents a critical interaction in biological systems and supramolecular chemistry, posing challenges for computational methods due to its mixed electrostatic and dispersion character. Recent benchmark studies provide rigorous comparisons between CC and DFT approaches:

Table 2: Performance of quantum chemical methods for hydrogen bonding interactions

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T)/CBS, CCSDT(Q) | 0.1-0.3 (reference) | Very High | Small systems, benchmark generation |

| Double Hybrid DFT | DSD-BLYP, B2PLYP | 0.2-0.5 | High | Medium-sized systems requiring high accuracy |

| Meta-Hybrid DFT | M06-2X | 0.2-0.4 | Medium | Large systems with diverse interactions |

| Hybrid DFT | ωB97X-V, B3LYP-D3(BJ) | 0.3-0.8 | Medium | Routine applications on complex systems |

| GGA DFT | BLYP-D3(BJ), BLYP-D4 | 0.4-1.0 | Low | Preliminary screening, very large systems |

A 2025 benchmark study on hydrogen bonds employed focal point analyses (FPA) extrapolating to the ab initio limit using correlated wavefunction methods up to CCSDT(Q) [14]. The resulting reference data demonstrated that the meta-hybrid M06-2X provided the best overall performance for both hydrogen bond energies and geometries among the 60 density functionals tested [14]. The dispersion-corrected GGAs BLYP-D3(BJ) and BLYP-D4 also yielded accurate hydrogen-bond data, serving as cost-effective choices for studying large and complex systems [14].

Another 2025 benchmark focusing specifically on quadruple hydrogen bonds found that the top-performing density functionals were dominated by variants of the Berkeley functionals, both with and without dispersion corrections [15]. The B97M-V functional with empirical D3BJ dispersion correction performed particularly well for these challenging interactions [15].

Non-Covalent Interactions in Biological Systems

Non-covalent interactions (NCIs) play crucial roles in biological recognition and drug binding. The 2025 QUID (QUantum Interacting Dimer) benchmark framework addresses the critical need for accurate reference data in biologically relevant systems [10]. This comprehensive study employed complementary CC and quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) methods to establish robust binding energies for 170 non-covalent systems modeling ligand-pocket interactions [10] [11].

The key findings revealed that several dispersion-inclusive density functional approximations provide accurate energy predictions, though their atomic van der Waals forces differ in magnitude and orientation, which could influence ligand binding dynamics [10]. The study established a "platinum standard" through tight agreement (0.3-0.5 kcal/mol) between LNO-CCSD(T) and FN-DMC methods, largely reducing uncertainty in highest-level QM calculations [10] [11].

Diagram 2: Benchmark validation workflow for establishing accurate reference data. Modern benchmarks employ multiple high-level methods to minimize uncertainty in reference values.

Electronic Properties: Dipole Moments and Polarizabilities

The performance differences between CC and DFT methods extend beyond energies to electronic properties such as dipole moments and polarizabilities. A systematic comparison study calculated these properties for 16 different molecules using both CCSD and auxiliary density functional theory (ADFT) [16].

The results demonstrated that for dipole moments and polarizabilities, ADFT and CCSD results showed very good agreement [16]. However, significant discrepancies emerged for first hyperpolarizabilities, particularly in conjugated systems where DFT tends to overestimate these properties due to incorrect asymptotic behavior of the exchange functional [16].

This systematic comparison highlights that DFT failures to correctly predict molecular polarizabilities and hyperpolarizabilities are not single-sourced but depend on the electronic characteristics of the system under investigation [16].

Domain-Specific Applications and Limitations

Materials Science and Drug Development Contexts

The choice between coupled cluster and density functional theory depends critically on the specific application domain and the properties of interest:

Table 3: Domain-specific applicability of CC and DFT methods

| Application Domain | Recommended Method | Rationale | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Electronics | Double-hybrid DFT | Balanced treatment of conjugation and dispersion | CC too expensive for relevant system sizes |

| Polymers | Hybrid DFT with dispersion correction | Scalable to large chains with diverse interactions | Challenging for π-conjugated systems |

| Drug Development | Hybrid/meta-hybrid DFT for screening, LNO-CCSD(T) for validation | QUID benchmarks show several DFAs perform well | Force fields require improvement for non-equilibrium geometries [10] |

| Catalysis/Reactive Systems | CCSD(T) for mechanism validation, DFA for screening | Need for accurate barrier heights | CCSD(T) limited to ~50 atoms [3] |

| Metals/Alloys/Ceramics | DFT with appropriate XC functional | Periodic boundary conditions well-implemented | CC implementations for periodic systems challenging [3] |

| Energy Capture/Storage | DFT for materials screening | Required system sizes too large for CC | Accuracy limitations for charge transfer states |

For materials science applications involving periodic systems, CC implementations remain challenging and computationally expensive [3]. As noted in benchmark discussions, "coupled cluster is also difficult to implement and costly for periodic systems and remains an active area of research" [3]. This limitation makes DFT the preferred method for most materials modeling applications, particularly for metals, alloys, and ceramics.

In drug development, the QUID benchmark study demonstrates that several dispersion-inclusive density functional approximations provide accurate energy predictions for ligand-pocket interactions [10]. However, the study also found that semiempirical methods and empirical force fields require improvements in capturing non-covalent interactions for out-of-equilibrium geometries [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential computational methods and resources for electronic structure research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localized Natural Orbital CC | Wavefunction Method | High-accuracy energies for large systems | Ligand-pocket interactions, non-covalent complexes [10] |

| Dispersion-Corrected DFAs | Density Functional | Efficient inclusion of dispersion forces | Biomolecular systems, supramolecular chemistry [15] [14] |

| Focal Point Analysis | Computational Protocol | Hierarchical approach to complete basis set limit | Benchmark generation, method validation [14] |

| Auxiliary Density DFT | Efficient DFT Implementation | Reduced computational cost for properties | Large molecules, property calculations [16] |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | Alternative High-Accuracy Method | Validation of CC results, independent benchmark | Complex systems where CC is questionable [10] [11] |

The comparative analysis of coupled cluster theory and density functional theory reveals a complex landscape where methodological selection must balance accuracy requirements against computational constraints. The exponential ansatz of coupled cluster theory provides a mathematically elegant framework that, when carried to sufficiently high excitation levels, approaches the exact solution to the Schrödinger equation [9]. However, the prohibitive computational scaling of these methods limits their application to small and medium-sized molecules [3].

Density functional theory offers a practical alternative with dramatically better computational scaling, enabling applications to systems containing thousands of atoms [13] [12]. Modern density functional approximations, particularly meta-hybrids and double hybrids with dispersion corrections, can achieve impressive accuracy for many chemical properties [15] [14]. The recent QUID benchmark demonstrates that carefully selected DFAs can reliably model even challenging biological ligand-pocket interactions [10].

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the evidence suggests a strategic approach: employ accurate DFT methods for screening and exploration, reserving high-level coupled cluster calculations for validation of key intermediates, transition states, and benchmark systems. This hybrid methodology leverages the respective strengths of both approaches while mitigating their weaknesses, providing a balanced pathway to reliable computational predictions in scientific research.

Density functional theory (DFT) stands as the undisputed workhorse of computational chemistry, physics, and materials science, enabling researchers to simulate and predict the electronic structure and properties of atoms, molecules, and materials with a compelling balance of computational efficiency and accuracy. The foundation of modern DFT rests upon the Kohn-Sham (KS) approach, which, in principle, represents an exact theory but requires approximations for the exchange-correlation (XC) energy functional in practical implementations. Over the past six decades, hundreds of density functional approximations (DFAs) have been developed, presenting varying levels of complexity and accuracy. Among these, the progression from the Local Density Approximation (LDA) to Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) and finally to hybrid functionals represents the evolutionary path that has cemented DFT's dominant position in computational research, particularly for systems where higher-level quantum chemical methods remain computationally prohibitive.

This guide examines the practical dominance of DFT methods within the broader context of comparing coupled-cluster versus DFT accuracy research. While coupled cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T), is widely recognized as a gold standard for achieving high accuracy in quantum chemical calculations, its computational expense and unfavorable scaling often render it impractical for systems beyond a few dozen atoms. In contrast, DFT methods offer a computationally feasible alternative for studying practically relevant system sizes and timescales, from catalytic reactions to biological molecules and solid-state materials, making them indispensable tools across scientific disciplines.

The Theoretical Spectrum: From LDA to Hybrid Functionals

The Foundation: Local Density Approximation (LDA)

The Local Density Approximation represents the simplest and historically first practical implementation of DFT. LDA operates on the fundamental assumption that the exchange-correlation energy at any point in space depends only on the electron density at that specific point, effectively treating the electron distribution as a uniform electron gas. Common implementations include the VWN (Vosko-Wilk-Nusair) functional, which incorporates correlation effects, and the PW92 (Perdew-Wang 1992) parametrization. While LDA provides a reasonable starting point and surprisingly accurate results for some metallic systems, it suffers from systematic underestimation of band gaps, overbinding of molecules and solids, and poor description of weakly bound systems, limitations that spurred the development of more sophisticated approximations.

Accounting for Inhomogeneity: Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA)

Recognizing the limitations of LDA, the Generalized Gradient Approximation introduced a crucial refinement by incorporating the gradient of the electron density in addition to its local value. This allows GGA functionals to account for inhomogeneities in the electron distribution, leading to significant improvements across various chemical properties. Popular GGA functionals include:

- BP86: Combines Becke's 1988 exchange functional with Perdew's 1986 correlation functional

- BLYP: Utilizes Becke exchange with Lee-Yang-Parr correlation

- PBE: Employs the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange and correlation functionals, known for its general reliability without empirical parameters

GGA functionals generally improve molecular geometries and bond energies compared to LDA but tend to overcorrect for lattice constants in solids and still struggle with accurate prediction of reaction barriers and properties sensitive van der Waals interactions without additional corrections.

The State-of-the-Art: Hybrid Functionals

Hybrid functionals represent the current pinnacle of widely applicable DFAs, systematically blending a fraction of the exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange energy with semilocal exchange and correlation functionals (typically at the GGA or meta-GGA levels). Introduced by Axel Becke in 1993, hybrid functionals find theoretical justification through the adiabatic connection formula and the generalized KS framework. Their popularity stems from several advantageous features: systematically higher predictive accuracy for numerous properties, reduction of self-interaction errors, partial addressing of the derivative discontinuity problem, and improved treatment of band gaps and charge-transfer excitations.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Hybrid Density Functionals

| Functional Type | Key Components | Representative Examples | Typical HF Exchange % | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Hybrid | Fixed mixture of HF + GGA/mGGA | B3LYP, PBE0 | 20-25% | Balanced accuracy for diverse properties |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | HF in long-range, DFT in short-range | ωB97 series | Varies with distance | Improved charge-transfer excitations |

| Meta-Hybrid | Includes kinetic energy density | TPSSh | 10% | Improved for metallic systems |

| Double-Hybrid | Adds perturbative correlation | B2PLYP | ~50% HF + MP2 correlation | Higher accuracy, increased cost |

The essential formulation of a hybrid functional can be represented as: E^HYBXC = αE^HFX + (1-α)E^DFTX + E^DFTC where α represents the fraction of Hartree-Fock exact exchange mixed with the DFT exchange component, while E^DFT_C denotes the correlation component from DFT.

Comparative Accuracy: DFT Versus Coupled Cluster Benchmarks

The Gold Standard: Coupled Cluster Theory

Coupled cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T) which considers single, double, and perturbative triple excitations, systematically approaches the exact solution to the Schrödinger equation and is considered the gold standard for many quantum chemistry applications. When CCSD(T) calculations are combined with an extrapolation to the complete basis set (CBS) limit, even challenging non-covalent and intermolecular interactions can be computed quantitatively. The fundamental limitation of coupled cluster methods lies in their computational cost, which scales combinatorically with the number of electrons and basis functions, effectively restricting routine application to systems with approximately 10-20 non-hydrogen atoms. For larger systems, such as those relevant to drug discovery, materials science, and biological simulations, CCSD(T) becomes computationally prohibitive, creating the practical niche that DFT occupies.

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Recent comprehensive evaluations have quantified the performance gaps between DFT approximations and coupled cluster accuracy. A critical evaluation of 155 hybrid DFAs available in the LIBXC library tested these functionals against CCSD(T) and full CI (FCI) references for fundamental properties including total energies, electron densities, and ionization potentials. The study found that functionals with a large mixture of Hartree-Fock exchange generally produced more accurate KS XC potentials, which directly impacted the quality of ionization potentials computed as -ε_HOMO.

Table 2: Accuracy Benchmarks of Computational Methods (Mean Absolute Deviations)

| Method | Computational Scaling | Typical System Size | Reaction Energy Error (kcal/mol) | Barrier Height Error (kcal/mol) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T)/CBS | N^7 | 10-20 atoms | 0.1-0.5 | 0.1-0.5 | [17] |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | N^5-N^7 | 20-50 atoms | 1-2 | 1-3 | [18] |

| Hybrid DFT (ωB97X) | N^3-N^4 | 50-200 atoms | 2-4 | 2-5 | [19] |

| GGA DFT (PBE) | N^3 | 100-1000 atoms | 5-10 | 5-10 | [18] |

| LDA | N^3 | 100-1000 atoms | 10-20 | 10-20 | [18] |

The breakthrough AIQM2 method represents a significant advancement, demonstrating that AI-enhanced quantum mechanical methods can approach coupled cluster accuracy while maintaining computational costs orders of magnitude lower than conventional DFT. In extensive reaction dynamics studies, AIQM2 achieved accuracy at least at the level of quality DFT functionals and often approaching the gold-standard coupled cluster accuracy, revising previously reported mechanisms and product distributions for bifurcating pericyclic reactions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking DFT Performance

The assessment of DFT accuracy follows rigorous benchmarking protocols employing high-quality reference data. Standard methodologies include:

- Reference Data Generation: Using CCSD(T)/CBS or FCI calculations for small molecular systems (typically up to 10 non-hydrogen atoms) to establish reference values for reaction energies, barrier heights, and molecular properties.

- Error Metrics Calculation: Employing mean absolute deviations (MAD), root mean squared deviations (RMSD), and relative errors for properties including total energies, electron densities, and ionization potentials.

- Systematic Testing Sets: Utilizing standardized benchmark sets like the GMTKN55 database, which encompasses diverse chemical problems including reaction energies, non-covalent interactions, and spectroscopic properties.

For example, in the evaluation of hybrid functionals, the methodology involves calculating the XC potential by inverting the KS electron densities obtained from self-consistent hybrid generalized KS calculations. The quality assessment then employs error measurements such as:

Δvxc = ∥δvxc∥L2 / ∥v^refxc∥_L2

where δvxc = v^refxc - v_xc is computed at every grid point, and the L2 norm provides a quantitative measure of deviation from reference data.

Force and Dynamics Accuracy Assessment

The accuracy of DFT-computed forces is particularly crucial for molecular dynamics simulations and geometry optimizations. Recent investigations have revealed significant uncertainties in DFT forces across several popular molecular datasets (SPICE, Transition1x, ANI-1x) used for training machine learning interatomic potentials. The assessment protocol involves:

- Net Force Analysis: Evaluating the magnitude of nonzero net forces, which should theoretically be zero in the absence of external fields and serve as indicators of numerical errors.

- Force Component Comparison: Recomputing forces using tightly converged DFT settings at the same level of theory to quantify errors in individual force components.

- Convergence Testing: Identifying optimal computational parameters (integration grids, SCF convergence thresholds, RI approximations) to minimize numerical errors without prohibitive computational cost.

Studies have found that errors in DFT force components can average from 1.7 meV/Å in well-converged datasets to 33.2 meV/Å in datasets with suboptimal settings, highlighting the critical importance of computational parameters in obtaining reliable DFT data for benchmarking and applications.

Domain-Specific Applications and Performance

Materials Science and Solid-State Chemistry

DFT methods dominate computational materials science due to their favorable scaling with system size and ability to handle periodic boundary conditions. In the study of perovskite materials like SmAsO3 for optoelectronic applications, DFT enables comprehensive investigation of structural, electronic, mechanical, optical, and thermodynamic properties that would be prohibitively expensive with coupled cluster methods. GGA and hybrid functionals successfully predict stable orthorhombic structures, formation energies, and mechanical stability, though band gaps often require more sophisticated treatments (e.g., GW approximation) for quantitative accuracy with experimental measurements.

Reaction Mechanism Elucidation

DFT's practical dominance is particularly evident in the study of reaction mechanisms, where it enables location of transition states, computation of reaction barriers, and exploration of potential energy surfaces for systems of synthetic and biological relevance. The AIQM2 method exemplifies recent progress, demonstrating the capability to revise previously reported mechanisms for complex organic reactions like bifurcating pericyclic reactions through extensive reaction dynamics studies performed overnight - a task that would be impossible with coupled cluster methods for systems of this size.

Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Simulations

In pharmaceutical research, DFT provides crucial insights into ligand-protein interactions, reaction mechanisms of enzymatic processes, and spectroscopic properties of drug molecules. While classical force fields handle large-scale biomolecular simulations, DFT remains indispensable for studying electronic processes, reaction mechanisms, and properties requiring quantum mechanical treatment in systems up to several hundred atoms. Hybrid functionals with dispersion corrections offer the best compromise for non-covalent interactions prevalent in biological systems.

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Machine Learning Enhanced Quantum Chemistry

The integration of machine learning with traditional quantum chemistry methods represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and chemistry. Methods like ANI-1ccx demonstrate how neural network potentials can approach coupled cluster accuracy while being billions of times faster through transfer learning techniques. These approaches begin with training on large DFT datasets then retraining on smaller, intelligently selected CCSD(T)/CBS datasets, achieving accuracy that outperforms standard DFT while maintaining transferability across chemical space.

Advanced Functional Development

Ongoing development of density functionals continues to address systematic deficiencies in existing approximations. Research directions include:

- Nonlocal Correlation Functionals: Improved description of van der Waals interactions without empirical corrections

- Double-Hybrid Functionals: Incorporating perturbative correlation for improved accuracy with manageable computational cost increases

- Systematic Improvability: Developing functionals with clear pathways to exactness through inclusion of additional physical constraints

These developments gradually narrow the accuracy gap between practical DFT methods and coupled cluster theory while maintaining the computational efficiency that underpins DFT's dominant position in computational chemistry.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes | VASP, ORCA, Gaussian, ADF, FHI-aims | Solve Kohn-Sham equations | Energy, force, property calculations |

| Wavefunction Codes | CFOUR, MRCC, Psi4 | High-level electron correlation | Coupled cluster reference calculations |

| Basis Sets | def2-TZVPP, 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ | Mathematical basis for orbital expansion | Balance between accuracy and cost |

| Analysis Tools | Multiwfn, VMD, Jmol | Visualization and property analysis | Interpret computational results |

| Benchmark Sets | GMTKN55, S22, DBH24 | Standardized performance assessment | Functional testing and validation |

Diagram 1: The Evolutionary Path of DFT Approximations Toward Higher Accuracy

DFT's practical dominance from LDA and GGA to hybrid functionals stems from its unparalleled ability to balance computational efficiency with quantitative accuracy across diverse chemical systems and properties. While coupled cluster theory remains the gold standard for achievable accuracy in quantum chemistry, its computational prohibitions for systems of practical interest in materials science, drug discovery, and biochemistry cement DFT's position as the indispensable tool for computational research. The ongoing development of hybrid functionals, machine learning potentials, and advanced approximations continues to narrow the accuracy gap between practical DFT methods and coupled cluster theory, ensuring DFT's continued dominance while progressively expanding the frontiers of computational chemistry.

In computational chemistry, the choice of method is governed by a fundamental trade-off: the balance between the accuracy of a calculation and its computational cost. For decades, high-accuracy wave function methods, like coupled-cluster theory, and more efficient Density Functional Theory (DFT) have occupied opposite ends of this spectrum. This guide objectively compares these approaches, focusing on recent research that aims to reconcile this dilemma through innovative methods and machine learning.

The predictive power of computational chemistry is vital for accelerating scientific discovery in areas like drug and battery design. However, this power is constrained by a core trade-off. On one end, coupled-cluster methods, often considered the "gold standard," offer high accuracy but at a computational cost that scales exponentially with the number of electrons, making them prohibitive for large systems [20]. On the other end, Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides an extraordinary reduction in computational cost, scaling polynomially and enabling the study of practically valuable systems [20]. Yet, its accuracy is limited by the unknown exact form of the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, a crucial term that describes how electrons interact [20].

The quest for chemical accuracy (around 1 kcal/mol for many chemical processes) drives methodological development. While current DFT approximations typically have errors 3 to 30 times larger than this threshold [20], recent advances are reshaping the accuracy-cost landscape. The following sections compare the traditional and emerging paradigms, providing quantitative data and methodological details.

Traditional Paradigm: Coupled-Cluster vs. Standard DFT

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these established methods.

Table 1: Traditional Methods in the Accuracy-Cost Landscape

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Typical Accuracy | Computational Scaling | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled-Cluster (e.g., CCSD) | Wave Function Theory; models electron correlation explicitly. | Very High (sub-chemical accuracy achievable) [21] | Exponential (O(N⁷) for CCSD(T)) [20] | Small molecules, benchmark studies, final high-accuracy checks. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density; relies on approximate exchange-correlation functionals. | Moderate (errors 3-30x chemical accuracy) [20] | Polynomial (O(N³)) [20] | Large systems (hundreds of atoms), trend analysis, initial screening. |

The primary advantage of coupled-cluster theory is its high accuracy and systematic improvability. However, its direct application to bulk materials or large molecular ensembles has been largely out of reach due to prohibitive costs [21]. DFT, in contrast, is computationally feasible but suffers from systematic errors due to approximations in the XC functional, which can lead to qualitative failures in describing subtle phenomena like polymorphism or certain liquid-phase properties [21].

Breaking the Paradigm: Emerging Strategies and Performance Data

Recent research has introduced innovative strategies to circumvent the traditional trade-off. These can be broadly categorized into two approaches: (1) reducing the cost of high-accuracy wave function methods, and (2) enhancing the accuracy of DFT through machine learning.

Cost Reduction in Wave Function Theories

New methods are being developed to make coupled-cluster theory more accessible for larger systems and excited states.

Table 2: Emerging Methods for Cost-Effective High Accuracy

| Method | Innovation | Performance Gain | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| State-Specific Frozen Natural Orbital (SS-FNO) [22] | Truncates virtual orbital spaces systematically using state-specific natural orbitals. | Reduces cost while maintaining high accuracy (mean absolute deviation <0.02 eV vs. canonical method) [22]. | Excited state calculations (valence, Rydberg, charge-transfer). |

| Nested Aufbau Suppressed Coupled Cluster [23] | Nests a small coupled-cluster treatment inside a lower-cost perturbation theory. | Drops formal cost from iterative N⁶ to non-iterative N⁵; charge transfer energy errors typically <0.1 eV [23]. | Charge transfer excitations in medium to large molecules. |

| Fragment-based Ab Initio Monte Carlo (FrAMonC) [21] | Uses a many-body expansion scheme to apply coupled-cluster theory to bulk amorphous materials. | Enables coupled-cluster level simulation of liquids and glasses; predicts liquid-phase densities with high accuracy [21]. | Thermodynamic properties of amorphous molecular materials (liquids, glasses). |

Accuracy Enhancement in DFT via Machine Learning

Instead of using hand-designed approximations for the XC functional, machine learning (ML) models are now trained on highly accurate data to learn the functional directly.

- Microsoft's Skalea Functional: This deep-learning-based XC functional was trained on an unprecedented dataset of diverse molecular structures, with atomization energies computed using high-accuracy wavefunction methods [20]. Within the chemical space of its training data, Skalea reaches chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol), a key threshold for reliably predicting experimental outcomes [20]. Its computational cost is significantly lower than standard hybrid functionals, being about 10% of their cost [20].

- Potential-Informed ML Models: A team from the University of Michigan demonstrated that training ML models not just on interaction energies but also on the potentials that describe how that energy changes in space leads to more universal XC functionals [24]. Their model, trained on a compact dataset of five atoms and two simple molecules, outperformed or matched widely used XC approximations while keeping computational costs low [24].

Performance Benchmarking on Charge-Related Properties

The table below benchmarks the performance of new ML-potentials against traditional DFT and semi-empirical methods on the challenging task of predicting reduction potentials, a property sensitive to charge and spin [25].

Table 3: Benchmarking Reduction Potential Prediction (Mean Absolute Error in Volts) [25]

| Method | Main-Group Species (OROP) | Organometallic Species (OMROP) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c (DFT) | 0.260 | 0.414 | Traditional DFT functional |

| GFN2-xTB (SQM) | 0.303 | 0.733 | Semi-empirical method |

| UMA-S (OMol25 NNP) | 0.261 | 0.262 | Machine Learning Potential; more accurate for organometallics |

| UMA-M (OMol25 NNP) | 0.407 | 0.365 | Machine Learning Potential |

This data reveals a surprising trend: despite not explicitly considering charge-based physics, the OMol25-trained neural network potential (UMA-S) performed on par with DFT for main-group molecules and was significantly more accurate for organometallic species [25].

Experimental Protocols in Focus

To ensure reproducibility and clarity, this section details the methodologies behind key experiments cited in this guide.

- Data Generation: A scalable pipeline generated a highly diverse set of molecular structures. Substantial high-performance computing (Azure) resources were used.

- Reference Energy Calculation: In collaboration with a domain expert (Prof. Amir Karton), high-accuracy wavefunction methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) were applied to these structures to compute atomization energies, creating a dataset two orders of magnitude larger than previous efforts.

- Model Training: A dedicated deep-learning architecture ("Skala") was designed to learn the XC functional from the electron density. The model was trained to predict the XC energy from the input density.

- Validation: The model's performance was assessed on the well-known W4-17 benchmark dataset, demonstrating generalization to unseen molecules and achieving chemical accuracy.

- Orbital Generation: Initial guesses for excited states are generated using lower-level methods like CIS(D) or ADC(2).

- Natural Orbital Construction: State-specific natural orbitals (SS-FNOs) are constructed from these initial guesses.

- Virtual Space Truncation: The virtual orbital space is systematically truncated based on the occupation numbers of the SS-FNOs, significantly reducing the problem size.

- CCSD Calculation & Correction: The Equation-of-Motion Coupled-Cluster (EE-EOM-CCSD) calculation is performed in the truncated space. A perturbative correction is added to compensate for the truncation error.

- Benchmarking: Results are validated against canonical (full) EE-EOM-CCSD results to ensure deviations are minimal.

Visualizing the Evolving Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the shifting paradigms in computational chemistry, from the traditional trade-off to the new, converging pathways enabled by recent research.

This table details essential computational tools and datasets referenced in the featured research.

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skalea Functional [20] | Machine-Learned XC Functional | Provides DFT calculations at chemical accuracy for a known chemical space. | Enables highly accurate, cost-effective DFT simulations for molecule and material design. |

| OMol25 Dataset [25] | Quantum Chemistry Dataset | A massive dataset of >100M calculations (ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) for training ML potentials. | Serves as a foundational training resource for general-purpose neural network potentials (NNPs). |

| State-Specific FNO Framework [22] | Computational Algorithm | Systematically truncates virtual orbital space in coupled-cluster calculations. | Reduces the computational cost of excited-state coupled-cluster calculations while preserving accuracy. |

| Fragment-based Ab Initio Monte Carlo (FrAMonC) [21] | Simulation Methodology | Enables thermodynamic simulation of amorphous materials using high-level ab initio methods. | Allows the application of coupled-cluster theory to bulk liquids and glasses, previously infeasible. |

| W4-17 Benchmark [20] | Benchmark Dataset | A well-known set of molecular data for evaluating the accuracy of computational methods. | Used to validate the experimental predictive power of new methods like the Skalea functional. |

The landscape of computational chemistry is undergoing a significant transformation. The long-standing trade-off between accuracy and computational cost is being actively dismantled. Through two complementary paths—reducing the cost of gold-standard coupled-cluster methods and infusing DFT with the predictive power of machine learning—researchers are converging on a new ideal. The emergence of methods like fragment-based coupled-cluster, cost-reduced orbital frameworks, and deep-learned functionals demonstrates a clear trend: the community is steadily overcoming fundamental barriers, promising to shift the balance of scientific discovery from the lab to the computer.

Applying CC and DFT in Practice: From Single Molecules to Drug Discovery

Coupled-cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) has earned its reputation as the "gold standard" of quantum chemistry for its exceptional accuracy in predicting molecular properties and reaction energetics [26] [27]. This high-level wavefunction-based method systematically approaches the exact solution to the Schrödinger equation, providing benchmark-quality results that can be as trustworthy as experimental data [28]. However, this exceptional accuracy comes with substantial computational cost, scaling as O(N⁷) with system size, where N represents the number of electrons [28] [26]. This severe scaling naturally restricts routine CCSD(T) applications to relatively small molecular systems, typically containing up to approximately 10 atoms, beyond which calculations become prohibitively expensive [28].

In contrast, density functional theory (DFT) offers a more computationally efficient alternative, with broader applicability to larger systems including those relevant to drug discovery and materials science. The trade-off, however, involves variable accuracy that depends heavily on the selected exchange-correlation functional, sometimes yielding unreliable results [28] [27]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between canonical CCSD(T) and DFT methodologies, specifically focusing on their performance for small molecular systems where CCSD(T) calculations remain computationally feasible. We present objective experimental data, detailed protocols, and practical guidance to help researchers make informed decisions about when the CCSD(T) gold standard is warranted despite its computational demands.

Theoretical Background and Computational Approaches

The CCSD(T) Methodology

The CCSD(T) method combines a coupled-cluster treatment of single and double excitations with a perturbative correction for connected triple excitations. This specific combination is crucial for achieving chemical accuracy (approximately 1 kcal/mol error) for many molecular properties [27]. The method's precision is often maximized when combined with a complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation, a combination denoted as CCSD(T)/CBS, which effectively eliminates basis set truncation errors [29] [26]. For noncovalent interactions, reaction energies, and barrier heights, CCSD(T)/CBS is widely recognized as the most reliable theoretical reference value when experimental data is unavailable or uncertain [29] [30].

Density Functional Theory Alternatives

DFT employs a fundamentally different approach, determining the total energy of a molecular system from its electron density distribution rather than a many-electron wavefunction [28]. While computationally efficient and scalable to large systems, DFT results are inherently dependent on the choice of exchange-correlation functional. This introduces a degree of empiricism and functional transferability issues that can compromise predictive reliability [27]. Numerous DFT functionals have been developed, including the PBE0, M05-class, and M06-class functionals, each with varying performance across different chemical systems and properties [31].

Performance Comparison: CCSD(T) vs. DFT for Small Systems

Accuracy Benchmarks for Molecular Properties

Table 1: Comparison of CCSD(T) and DFT Performance for Aluminum Clusters (Alₙ, n=2-7)

| Property | Experimental Value | PBE0/aug-cc-pVTZ Error (eV) | CCSD(T)/CBS Error (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Affinities | Reference Data | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Ionization Potentials | Reference Data | 0.15 | 0.13 |

Source: [31]

Independent benchmarks demonstrate the superior accuracy of CCSD(T) for predicting electronic properties of small clusters. For aluminum clusters (Alₙ, n=2-7), CCSD(T) at the complete basis set (CBS) limit achieves smaller average errors for both electron affinities and ionization potentials compared to PBE0 DFT [31]. The CCSD(T)/CBS approach shows remarkable consistency across various molecular properties, including those critical for understanding chemical reactivity and stability.

Table 2: Performance for Zirconocene Catalysis-Related Properties

| Property | DFT Performance | CCSD(T) Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Potentials | Well reproduced | Not Applicable (Used as Benchmark) |

| Fourth Ionization Potential (Zr) | Well reproduced | Used for benchmark refinement |

| Bond Dissociation Enthalpies (BDEs) | Large deviations from experiment | Suggests experimental values need revision |

| Source: [30] |

In studies of zirconocene polymerization catalysts, DFT generally performs well for ionization and redox potentials but shows significant deviations for bond dissociation enthalpies (BDEs) [30]. CCSD(T) calculations in this context provided such reliable results that they suggested the need for re-evaluation of experimental BDE values, highlighting the method's benchmark status [30].

Reaction Energies and Barrier Heights

For hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions—crucial processes in atmospheric, biological, and industrial chemistry—CCSD(T)/CBS provides highly accurate barrier heights and reaction energies [26]. These reactions are particularly challenging for computational methods due to the precise determination of correlation energy required for modeling hydrogen bond strength [26]. DFT performance for these systems can be inconsistent, with accuracy heavily dependent on the chosen functional, while CCSD(T) maintains reliable performance across diverse reaction types.

The exceptional accuracy of CCSD(T) extends to noncovalent interactions, which are essential determinants of molecular recognition, solvation effects, and biomolecular structure [29]. For the development of force fields and machine learning potentials, CCSD(T) interaction energies serve as indispensable benchmark references [29] [27].

Practical Protocols for CCSD(T) Application

Recommended Workflow for Small Systems

The following diagram illustrates a recommended decision workflow for applying CCSD(T) to small chemical systems:

Basis Set Selection Strategy

Achieving CCSD(T)/CBS accuracy requires careful basis set selection:

- For ultimate accuracy: Employ a hierarchical approach with correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVDZ, aug-cc-pVTZ, aug-cc-pVQZ) followed by extrapolation to the CBS limit [29] [26].

- For balanced efficiency: The aug-cc-pVTZ basis often provides an excellent compromise between accuracy and computational cost for small systems [31].

- For specific properties: Augmented basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVXZ) are essential for properties involving electron density tails such as electron affinities and noncovalent interactions [31].

Overcoming Computational Limitations

For systems at the upper size limit for CCSD(T), consider these approaches:

- Local Correlation Methods: Approximations like DLPNO-CCSD(T) (Domain-based Local Pair Natural Orbital) maintain much of the accuracy of canonical CCSD(T) while significantly reducing computational cost [26]. Testing has shown that with TightPNO settings, DLPNO-CCSD(T) can achieve standard deviations as low as 0.06 kcal/mol for reaction energies compared to canonical CCSD(T) [26].

- Focal Point Methods: Combine lower-level CCSD(T) calculations with large basis set MP2 computations to approximate CCSD(T)/CBS results.

- Hybrid Schemes: Apply CCSD(T) corrections to DFT energies for specific molecular fragments or reaction centers.

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

Machine Learning Enhancement

Machine learning (ML) approaches are revolutionizing computational chemistry by leveraging CCSD(T) accuracy while bypassing its computational cost. Neural network potentials like ANI-1ccx are trained on CCSD(T)/CBS data and can achieve coupled-cluster accuracy with a computational efficiency billions of times faster than direct CCSD(T) calculations [27]. These ML models can predict energies, forces, and multiple electronic properties simultaneously, extending the effective reach of CCSD(T) accuracy to much larger systems [28] [27].

The MIT-developed MEHnet (Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network) represents a significant advancement, utilizing CCSD(T) training data to predict multiple electronic properties—including dipole and quadrupole moments, electronic polarizability, and optical excitation gaps—from a single model [28]. This multi-task approach could eventually enable CCSD(T)-level accuracy for systems containing thousands of atoms, far beyond the current limits of direct CCSD(T) calculations [28].

Large-scale benchmark databases are increasingly important for method development and validation. The DES370K database, for instance, provides CCSD(T)/CBS interaction energies for over 370,000 dimer geometries, serving as a valuable resource for developing and testing more efficient computational methods [29]. Such databases help amortize the high computational cost of CCSD(T) calculations across the broader research community, accelerating advances in computational chemistry.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for CCSD(T) and DFT Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Q-Chem, ORCA, MOLPRO, Gaussian | Perform CCSD(T) and DFT electronic structure calculations |

| Benchmark Databases | DES370K, DES15K, DES5M | Provide gold-standard reference data for method development and validation |

| Machine Learning Potentials | ANI-1ccx, MEHnet | Achieve CCSD(T)-level accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost |

| Local Correlation Methods | DLPNO-CCSD(T) in ORCA | Extend CCSD(T) applicability to larger systems while maintaining accuracy |

| Basis Sets | aug-cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q), correlation-consistent series | Systematic approach to reaching complete basis set limit |

Canonical CCSD(T) remains the undisputed gold standard for quantum chemical calculations on small molecular systems where its exceptional accuracy justifies substantial computational costs. It is particularly recommended for final benchmark calculations when chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal/mol) is critical, for resolving discrepancies between DFT results and experimental data, and for generating reference data for method development [31] [30].

For routine applications on small systems, DFT with carefully selected functionals (e.g., PBE0) often provides satisfactory results at far lower computational cost [31]. However, emerging machine learning approaches trained on CCSD(T) data promise to revolutionize the field, potentially making CCSD(T)-level accuracy routinely accessible for large-scale molecular simulations in drug discovery and materials science [28] [27]. As these technologies mature, the distinctive line between high-accuracy methods for small systems and efficient methods for large systems may gradually disappear, ushering in a new era of predictive computational chemistry.

For decades, computational chemists have faced a fundamental trade-off between accuracy and system size in quantum chemical simulations. While coupled cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) has rightfully earned its reputation as the "gold standard" for computational chemistry, its astronomical computational cost—scaling as the seventh power of system size—severely limited practical applications to small molecules containing typically 20-30 atoms [32]. This restriction forced researchers studying larger systems, such as drug-like molecules or complex molecular assemblies, to rely predominantly on density functional theory (DFT), which offers greater speed but unpredictable accuracy due to its functional dependence.

The development of Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) represents a paradigm shift in this landscape. By leveraging the local nature of electron correlation, this innovative approach preserves the accuracy of conventional CCSD(T) while reducing computational scaling to near-linear, thereby extending the reach of gold standard quantum chemistry to systems containing hundreds of atoms [32]. This comparison guide examines how DLPNO-CCSD(T) achieves this breakthrough, objectively assesses its performance against alternatives, and provides the experimental data needed for researchers to evaluate its applicability to their scientific challenges.

Methodological Framework and Computational Workflow

Core Theoretical Principles

The DLPNO-CCSD(T) method achieves its remarkable efficiency through three interconnected theoretical advances that exploit the physical nature of electron correlation:

- Local Correlation Approximation: This principle recognizes that electron correlation is predominantly short-range, allowing the treatment of electron pairs to be restricted to those in spatial proximity [32].

- Domain Construction: Molecular orbitals are localized, and for each electron pair, a local domain is constructed containing the orbitals most important for describing correlation effects [32].

- Pair Natural Orbitals (PNOs): Within each pair domain, a compact set of virtual orbitals is generated specifically for that electron pair, dramatically reducing the number of variables needed for accurate correlation energy calculation [32].

These approximations are systematically improvable—tightening the thresholds controlling domain construction and PNO generation increases both accuracy and computational cost, eventually recovering conventional CCSD(T) results [32].

Standardized Calculation Workflow

The typical DLPNO-CCSD(T) computational protocol follows a well-defined sequence:

Diagram 1: Standard DLPNO computational workflow for thermodynamic properties.

This workflow illustrates the multi-step process for calculating experimentally comparable thermodynamic properties. The initial stages involve geometry optimization and frequency calculations at the RI-MP2 level with triple-zeta basis sets, providing the structural framework and zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) corrections. The critical step is the high-level DLPNO-CCSD(T) single-point energy calculation with a larger quadruple-zeta basis set, which captures the electronic energy with near-exact accuracy. Finally, these components are combined with element-specific empirical corrections to compute formation enthalpies, which are validated against critically-evaluated experimental data [33].

Performance Comparison: DLPNO-CCSD(T) vs Alternative Methods

Accuracy Assessment Against Experimental Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Enthalpies of Formation (kJ·mol⁻¹)

| Method Category | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Deviation | Expanded Uncertainty | Maximum System Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local CC Methods | DLPNO-CCSD(T) (TightPNO) | ~1.5-2.0 | ~3.0 | ~100+ atoms | [33] |

| Composite Methods | G4 | ~3.5-4.5 | N/R | ~10-15 atoms | [33] |

| Local CC Methods | LNO-CCSD(T) | ~0.8-1.2 | ~1.5-2.0 | ~1000 atoms | [32] |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | FN-DMC | ~3.3-4.5 | N/R | Medium-large systems | [34] |

In a rigorous validation against 45 critically-evaluated experimental formation enthalpies for molecules containing up to 12 heavy atoms, the DLPNO-CCSD(T) method demonstrated an expanded uncertainty of approximately 3 kJ·mol⁻¹, making it competitive with typical calorimetric measurements [33]. This performance surpassed the widely-used G4 composite method, which showed significantly larger deviations [33]. The study employed carefully optimized empirical atomic constants to convert electronic energies to formation enthalpies, following the equation: ΔfH° = E + ZPVE + Δ₀ᴛH - Σnᵢhᵢ, where the final term represents element-specific corrections [33].

Comparison with Other Local Coupled Cluster Methods

Table 2: Local CCSD(T) Method Capabilities Comparison

| Performance Metric | DLPNO-CCSD(T) | LNO-CCSD(T) | Conventional CCSD(T) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Scaling | Near-linear | Near-linear | N⁷ (steep) |

| Typical Accuracy Error | 1-3 kJ·mol⁻¹ | 0.8-1.2 kJ·mol⁻¹ | Exact (reference) |

| Maximum Practical System Size | Hundreds of atoms | Up to 1000 atoms | 20-30 atoms |

| Memory Requirements | Moderate (10-100 GB) | Moderate (10-100 GB) | Very high |

| Typical Wall Time | Days | Days | Weeks or impossible |

| Systematic Imrovability | Available | Advanced | Native |

| Robust Error Estimation | Limited | Available | Not applicable |

While both DLPNO-CCSD(T) and Local Natural Orbital (LNO) CCSD(T) methods exploit local correlation, recent comprehensive assessments indicate that LNO-CCSD(T) generally provides slightly higher accuracy, with average errors below 0.5 kcal·mol⁻¹ (∼2 kJ·mol⁻¹) compared to conventional CCSD(T) references [32]. The LNO approach also demonstrates more systematic convergence properties and robust error estimation capabilities [32]. However, DLPNO-CCSD(T) remains the most widely known and implemented local correlation method, with extensive benchmarking and user-friendly implementations in popular quantum chemistry packages like ORCA [32].

Direct Comparison with Density Functional Theory

The fundamental advantage of DLPNO-CCSD(T) over DFT lies in its systematic improvability and predictable accuracy. Unlike DFT, where results depend heavily on the chosen functional and may yield unpredictable errors for new systems, DLPNO-CCSD(T) provides consistently reliable results across diverse chemical systems. While DFT with hybrid functionals typically requires hours to days for systems of 100+ atoms, DLPNO-CCSD(T) calculations typically require days on a single CPU, but with 1-2 orders of magnitude higher cost yielding substantially improved accuracy [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Gold-Standard Chemistry

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DLPNO-CCSD(T) Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | ORCA | Implements DLPNO-CCSD(T) with user-friendly interface | Most widely used platform for DLPNO methods |

| Software Packages | MRCC | Implements LNO-CCSD(T) alternatives | Provides advanced error estimation capabilities |

| Basis Sets | def2-TZVP | Geometry optimization and frequency calculations | Balanced accuracy/efficiency for initial steps |

| Basis Sets | def2-QZVP | Final DLPNO-CCSD(T) single-point energy | Higher accuracy for final energy evaluation |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | Corresponding RI/JK sets | Accelerate calculations via density fitting | Must match primary basis set for accuracy |

| Accuracy Settings | TightPNO | Controls PNO truncation thresholds | Essential for ∼1 kcal·mol⁻¹ accuracy |

| Accuracy Settings | NormalPNO | Default PNO settings | Higher throughput but reduced accuracy |

Application Case Studies Across Chemical Domains

Thermochemical Predictions for Organic Compounds

In the foundational validation study, researchers applied DLPNO-CCSD(T) to predict gas-phase enthalpies of formation for 45 closed-shell organic compounds containing C, H, O, and N atoms [33]. The computational protocol employed RI-MP2/def2-TZVP for geometry optimization and frequency calculations, followed by DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-QZVP single-point energies with TightPNO settings [33]. The results demonstrated the method's ability to achieve experimental-level accuracy while extending the reach of CCSD(T) to molecules significantly larger than previously possible with conventional approaches.

Biomolecular Systems and Drug Discovery Applications

The near-linear scaling of DLPNO-CCSD(T) has opened unprecedented opportunities for applying gold-standard quantum chemistry to biologically relevant systems. Researchers have successfully computed interaction energies for protein-ligand complexes, enzymatic reaction mechanisms, and spectroscopic properties of large biomolecules that were previously far beyond the reach of conventional CCSD(T) [32]. These applications provide crucial benchmarks for validating more approximate methods and offer unique atomistic insights into complex biological processes.

Catalysis and Transition Metal Chemistry