Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of cross-validation and bootstrapping for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of cross-validation and bootstrapping for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both internal validation techniques, their methodological applications in clinical prediction models, and practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization with real-world biomedical data. A detailed, evidence-based comparative analysis guides the selection of the appropriate technique based on dataset size, outcome characteristics, and modeling goals, with a focus on enhancing the reliability and generalizability of predictive models in healthcare.

Core Concepts: Understanding Internal Validation and the Problem of Optimism

The Critical Need for Internal Validation in Clinical Prediction Models

The development of clinical prediction models (CPMs) has seen exponential growth across all medical fields, with an estimated nearly 250,000 articles reporting the development of CPMs published to date [1]. This proliferation underscores the critical role predictive analytics plays in modern healthcare, from prognosis in oncology to estimating osteopenia risk. However, this abundance also highlights concerns about research waste and the limited application of many models in clinical practice. The chasm between development and implementation exists largely because the generalizability of predictive algorithms often goes untested, leaving the community in the dark regarding their real-world accuracy and safety [2].

Internal validation serves as the essential first step in addressing this challenge, providing optimism-corrected estimates of model performance within the development dataset. Without rigorous internal validation, researchers cannot determine whether their model has learned robust statistical relationships or has simply memorized noise in the training data—a phenomenon known as overfitting. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the two predominant internal validation methodologies—cross-validation and bootstrapping—examining their theoretical foundations, experimental performance, and optimal applications in clinical prediction research.

Internal Validation Fundamentals: Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping

Methodological Frameworks

Internal validation aims to assess the reproducibility of algorithm performance in data distinct from the development data but derived from the same underlying population [2]. Cross-validation and bootstrapping represent the two most recommended approaches for this purpose, each with distinct mechanistic philosophies.

Cross-validation operates on a data-splitting principle. The most common implementation, k-fold cross-validation, partitions the dataset into k equal parts (typically 5 or 10). The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining holdout fold. This process rotates until each fold has served as the validation set, with performance metrics averaged across all iterations [3] [2]. Nested cross-validation extends this approach by incorporating an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop for hyperparameter tuning, further reducing optimism bias [3].

Bootstrapping employs a resampling-based strategy, drawing multiple random samples from the original dataset with replacement (typically 500-2000 iterations) [2]. Each bootstrap sample is used to train a model, with performance evaluated on the out-of-bag (OOB) observations not included in the resample [4]. Several variants exist, including the optimism bootstrap (Efron-Gong method), the .632 bootstrap which adjusts for the bias that approximately 63.2% of unique observations are represented in each bootstrap sample, and the .632+ bootstrap which further corrects for situations with high overfitting [5].

Comparative Workflows

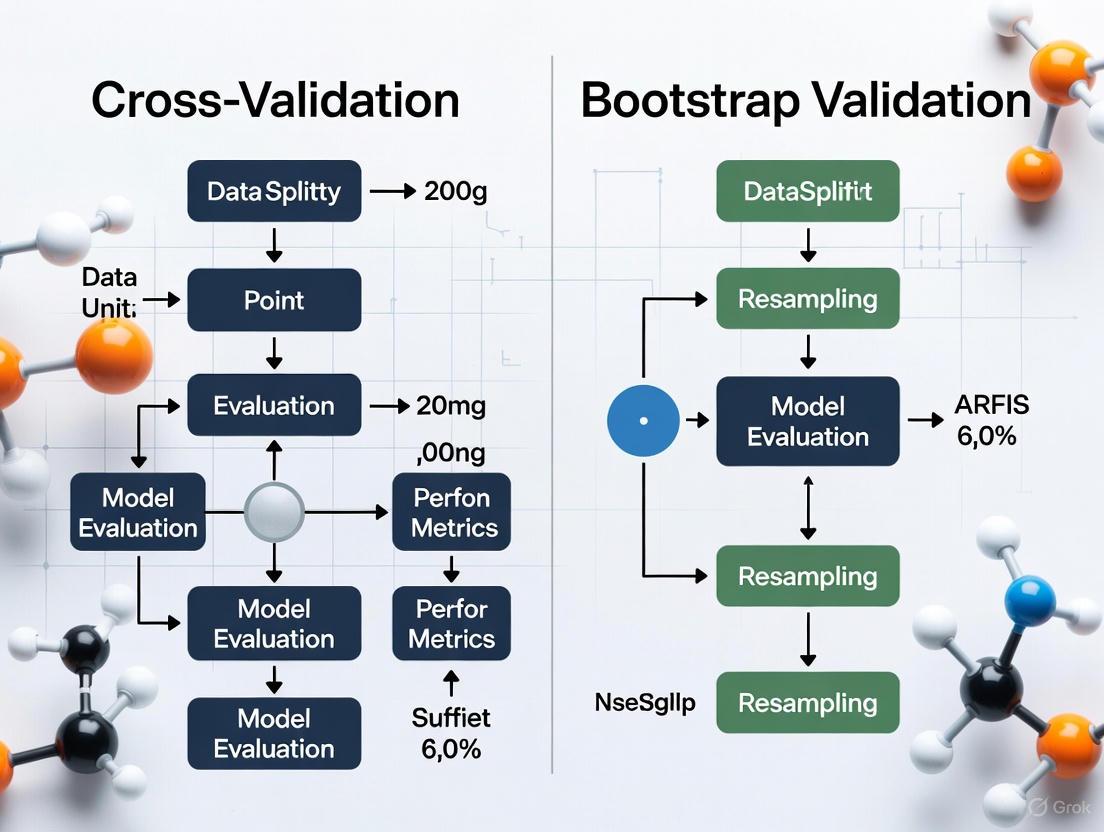

The fundamental differences between these methodologies can be visualized through their operational workflows:

Experimental Performance Comparison

Quantitative Findings from Simulation Studies

Recent benchmark studies have provided empirical evidence comparing these validation strategies. A comprehensive simulation study focused on high-dimensional prognosis models using transcriptomic data from head and neck tumors offers particularly insightful results [5] [6] [7]. The study evaluated performance across multiple sample sizes (n=50 to n=1000) using time-dependent AUC and integrated Brier Score as metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Internal Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Sample Size | Discrimination | Calibration | Overall Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train-Test Split | All sizes | Unstable | Unstable | Poor |

| Conventional Bootstrap | n=50-100 | Over-optimistic | Moderate | Moderate |

| 0.632+ Bootstrap | n=50-100 | Overly pessimistic | Moderate | Moderate |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | n=50-100 | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | n=500-1000 | Good | Good | Excellent |

| Nested Cross-Validation | n=50-100 | Good (varies) | Good (varies) | Moderate |

| Nested Cross-Validation | n=500-1000 | Excellent | Excellent | Good |

The findings demonstrate that k-fold cross-validation and nested cross-validation showed improved performance with larger sample sizes, with k-fold cross-validation demonstrating greater stability [6]. Conventional bootstrap methods tended to be over-optimistic in their performance estimates, while the 0.632+ bootstrap correction could swing to overly pessimistic, particularly with small samples (n=50 to n=100) [5] [6].

Context-Dependent Recommendations

The optimal choice between cross-validation and bootstrapping depends on specific research contexts:

Small sample sizes (n < 200): Bootstrapping is often preferred due to its stability and utility for uncertainty estimation [8], though the 0.632+ variant may require careful interpretation of potentially pessimistic bias [5].

High-dimensional data (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics): K-fold cross-validation is recommended as bootstrapping can overfit due to repeated sampling of the same individuals [5] [8] [6].

Time-to-event endpoints: K-fold and nested cross-validation show superior performance for Cox penalized models [5] [6].

Computational constraints: Repeated k-fold cross-validation requires 50-100 repetitions for sufficient precision, making bootstrap (with 300-1000 repetitions) sometimes faster [4].

Implementation Protocols

Cross-Validation Protocol

For researchers implementing k-fold cross-validation, the following detailed protocol is recommended:

Data Preparation: Handle missing data, outliers, and ensure appropriate feature scaling. For clinical data with repeated measures, implement subject-wise splitting to prevent data leakage [3].

Stratification: For classification problems with imbalanced outcomes, use stratified cross-validation to maintain consistent outcome rates across folds [3].

Fold Selection: Choose an appropriate k-value based on sample size. The common choices are 5-fold or 10-fold cross-validation [2].

Model Training: For each training fold, include hyperparameter tuning if needed. For nested cross-validation, this occurs in an inner loop [3].

Performance Aggregation: Calculate performance metrics (discrimination, calibration) for each test fold and aggregate using appropriate averaging methods [3].

Stability Enhancement: Repeat the entire k-fold procedure multiple times (e.g., 10×10-fold cross-validation) for more stable estimates [2].

Bootstrap Validation Protocol

For bootstrap validation implementations:

Resampling Scheme: Generate B bootstrap samples (typically 100-2000) by sampling with replacement from the original dataset [2].

Model Training: Train a model on each bootstrap sample [4].

Out-of-Bag Testing: Evaluate performance on the observations not selected in each bootstrap sample (approximately 36.8% of the original data) [4].

Optimism Calculation: For the optimism bootstrap, calculate the difference between bootstrap performance and performance on the original dataset [4].

Bias Correction: Apply appropriate corrections (.632 or .632+) based on the degree of overfitting [5].

Performance Estimation: Derive the final optimism-corrected performance estimate [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Internal Validation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Computing | R Software (version 4.4.0) [5] | Primary platform for implementing validation algorithms and analysis |

| Simulation Frameworks | Custom R scripts [6] | Generate synthetic datasets with known properties for method validation |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel processing clusters [3] | Handle computational demands of repeated resampling (100-2000 iterations) |

| Data Repositories | MIMIC-III [3], SCANDARE [5] | Provide real-world clinical datasets for validation experiments |

| Specialized Algorithms | Cox Penalized Regression [5] [6] | Reference models for high-dimensional time-to-event data validation |

| Performance Metrics | Time-dependent AUC, C-index, Integrated Brier Score [5] | Quantify discrimination and calibration for time-to-event outcomes |

The critical need for internal validation in clinical prediction models cannot be overstated. As the proliferation of new models continues, rigorous validation becomes increasingly essential to distinguish truly predictive algorithms from those that merely fit noise. The experimental evidence demonstrates that both cross-validation and bootstrapping offer distinct advantages, with k-fold cross-validation generally providing more stable performance estimates, particularly in high-dimensional settings, while bootstrap methods offer valuable insights into uncertainty.

Researchers must select their validation strategy based on their specific context—considering sample size, data dimensionality, outcome type, and computational resources. Regardless of the method chosen, comprehensive internal validation represents the essential foundation upon which clinically useful prediction models are built, serving as the critical bridge between development and meaningful clinical implementation.

In machine learning, overfitting occurs when a model fits too closely or even exactly to its training data, learning the "noise" or irrelevant information within the dataset, rather than the underlying pattern [9]. This creates a dangerous illusion: a model that appears to perform exceptionally during training but fails to generalize to new, unseen data [9]. For researchers and scientists in critical fields like drug development, this deception can have serious consequences, leading to incorrect conclusions based on models that will not hold up in real-world validation. The core of the problem lies in the model's inability to establish the dominant trend within the data, instead memorizing the training set [9]. This article, framed within a broader thesis on validation techniques, will objectively compare two fundamental methods for detecting and preventing this issue: cross-validation and bootstrap validation.

Unmasking the Deception: What is Overfitting?

A model is considered overfitted when it demonstrates low error rates on its training data but high error rates on test data it has never seen before [9]. This signals that the model has mastered the training data but cannot apply its "knowledge" broadly. The opposite problem, underfitting, occurs when a model has not trained for enough time or lacks sufficient complexity to capture the meaningful relationships in the data [9]. The goal of any model fitting process is to find the "sweet spot" between these two extremes, creating a model that generalizes well [9].

Quantifying this phenomenon is an active area of research. Recent work has introduced the Overfitting Index (OI), a novel metric designed to quantitatively assess a model's tendency to overfit, providing an objective lens to gauge this risk [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrap Validation

To combat overfitting, researchers rely on robust validation techniques. The following table details the key "research reagents" – the methodological solutions – essential for this task.

| Research Reagent / Method | Primary Function | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [11] | Partitions data into 'k' subsets for iterative training and validation. | Provides a good bias-variance tradeoff; excellent for model selection and hyperparameter tuning [11]. |

| Stratified K-Fold [11] | A variant that preserves the target variable's distribution in each fold. | Crucial for imbalanced datasets, ensuring representative folds [11]. |

| Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) [11] | Uses a single observation as the test set and the rest for training. | Provides an almost unbiased estimate but is computationally expensive [11]. |

| Bootstrap Validation [11] | Creates multiple training sets by sampling data with replacement. | Effective for small datasets and provides an estimate of performance metric variability [11]. |

| Out-of-Bag (OOB) Error [11] | Uses data points not selected in a bootstrap sample for validation. | Provides a built-in validation mechanism without a separate holdout set [4]. |

| Early Stopping [9] | Halts the training process before the model begins to learn noise. | A simple yet effective regularization technique to prevent overtraining. |

| Regularization (e.g., Dropout) [12] | Applies penalties to model parameters or randomly drops neurons during training. | Reduces model complexity and dependency on specific neurons, combating overfitting [9] [12]. |

Methodological Deep Dive: Core Protocols

Cross-Validation Protocol

The standard k-fold cross-validation methodology involves several key steps [11]:

- Data Partitioning: Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into

kmutually exclusive folds of approximately equal size. - Iterative Training and Validation: For each of the

kiterations:- Designate one fold as the validation (test) set.

- Combine the remaining

k-1folds to form the training set. - Train the model on the training set.

- Evaluate the model on the validation set and record the performance score (e.g., accuracy, R²).

- Performance Aggregation: Calculate the final model performance estimate by averaging the scores from all

kiterations.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Bootstrap Validation Protocol

The bootstrap methodology follows a distinct resampling approach [11] [4]:

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: For

Biterations (typically 1000 or more), draw a random sample of sizenfrom the original dataset with replacement. This is a single bootstrap sample. - Model Training and OOB Evaluation:

- Train the model on the bootstrap sample.

- Use the out-of-bag (OOB) data—the data points not included in the bootstrap sample—as a validation set.

- Evaluate the model on the OOB data and record the performance score.

- Result Aggregation: Average the results from all

Bbootstrap iterations to produce an overall performance estimate. The variability of these scores also provides an estimate of the model's stability.

The workflow for bootstrap validation is captured in the diagram below:

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Data and Performance

The choice between cross-validation and bootstrapping is not one-size-fits-all. It depends on the dataset size, the model's characteristics, and the goal of the validation. The table below summarizes experimental insights from comparative studies.

| Aspect | Cross-Validation | Bootstrap Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | Splits data into mutually exclusive 'k' folds [11]. | Samples data with replacement to create multiple bootstrap datasets [11]. |

| Bias & Variance | Tends to have lower variance but may have higher bias with small 'k' [11]. | Can provide a lower bias estimate but may have higher variance due to resampling [11] [4]. |

| Ideal Use Cases | Model comparison, hyperparameter tuning, and with large, balanced datasets [11]. | Small datasets, variance estimation, and scenarios with significant data noise or uncertainty [11]. |

| Computational Load | Computationally intensive for large 'k' or large datasets [11]. | Also computationally demanding, especially for a large number of bootstrap samples (B) [11]. |

| Performance Findings | Repeated 5 or 10-fold CV is often recommended for a good balance [4]. The .632+ bootstrap method is effective, particularly for smaller samples [4]. | Out-of-bag bootstrap error rates tend to have less uncertainty/variance than k-fold CV, but may have a bias similar to 2-fold CV [4]. |

For the researcher in drug development, where predictive accuracy is paramount, understanding the deceptive nature of apparent performance is non-negotiable. Overfitting poses a persistent threat that can only be countered by rigorous validation practices. Both k-fold cross-validation and bootstrap validation are powerful, essential tools in the modern scientist's arsenal. Cross-validation, particularly repeated 5 or 10-fold, offers a robust and widely trusted standard for model selection and tuning in many scenarios. In contrast, bootstrap methods, especially the .632+ variant, provide a critical alternative for smaller datasets or when an estimate of performance variability is needed. The ongoing research into metrics like the Overfitting Index [10] and the nuanced "double descent" risk curve [9] highlights that the field continues to evolve. Ultimately, the informed application of these validation protocols is our best defense against the siren song of a model that looks too good to be true.

Cross-validation is a fundamental statistical technique used to evaluate the performance and generalizability of predictive models. In an era where machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly applied to critical domains such as drug development and biomedical research, proper model validation has become paramount. Cross-validation addresses a crucial challenge in predictive modeling: the need to assess how well a model trained on available data will perform on unseen future data. This assessment helps prevent overoptimistic expectations that can arise when models are evaluated on the same data used for training, a phenomenon known as overfitting [13].

The core principle of cross-validation involves systematically partitioning a dataset into complementary subsets, performing model training on one subset (training set), and validating the model on the other subset (validation or test set). This process is repeated multiple times with different partitions, and the results are aggregated to produce a more robust performance estimate. Unlike single holdout validation, which uses a one-time split of the data, cross-validation maximizes data utility by allowing each data point to be used for both training and validation across different iterations [14] [3].

Within the broader context of validation methodologies, cross-validation serves as a cornerstone technique alongside resampling methods like bootstrap validation. While bootstrap validation involves drawing repeated random samples with replacement from the original dataset, cross-validation employs structured partitioning without replacement. This tutorial focuses specifically on two prominent cross-validation approaches—k-fold and leave-one-out cross-validation—comparing their methodological foundations, statistical properties, and practical applications in scientific research and drug development.

Understanding k-Fold Cross-Validation

Conceptual Foundation and Workflow

K-fold cross-validation is one of the most widely used cross-validation techniques in machine learning and statistical modeling. In this approach, the dataset is randomly partitioned into k approximately equal-sized subsets or "folds." The model training and validation process is then repeated k times, with each fold serving exactly once as the validation set while the remaining k-1 folds are used for training [15] [14]. This systematic rotation through all folds ensures that every observation in the dataset is used for both training and validation, just in different iterations.

The k-fold cross-validation process follows a specific workflow. First, the entire dataset is shuffled and divided into k folds of roughly equal size. For each iteration (from 1 to k), one fold is designated as the test set, and the remaining k-1 folds form the training set. A model is trained on the training set and its performance is evaluated on the test set. The performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, mean squared error) from all k iterations are then averaged to produce a single estimation of model performance [14]. This averaged result represents the cross-validation estimate of how the model is expected to perform on unseen data.

Implementation Considerations

The choice of k in k-fold cross-validation represents a critical decision that balances statistical properties with computational requirements. Common values for k are 5 and 10, though the optimal choice depends on dataset size and characteristics [14] [13]. With k=5, the model is trained on 80% of the data and tested on the remaining 20% in each iteration, while with k=10, the split becomes 90%-10%. Lower values of k (e.g., 2-5) result in more computationally efficient processes but with higher bias in the performance estimate, as the training sets are substantially smaller than the full dataset [16].

For datasets with imbalanced class distributions, stratified k-fold cross-validation is recommended. This variant ensures that each fold maintains approximately the same class proportion as the complete dataset, preventing situations where certain folds contain insufficient representation of minority classes [14]. This is particularly important in biomedical applications where outcomes of interest (e.g., rare diseases) may be naturally underrepresented in the dataset.

The computational intensity of k-fold cross-validation scales linearly with the chosen k value, as the model must be trained and evaluated k separate times. While this can be computationally expensive for complex models, the process is highly parallelizable since each fold can be processed independently. From a statistical perspective, k-fold cross-validation provides a good balance between bias and variance in performance estimation, particularly with k values between 5 and 10 [17] [16].

Understanding Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV)

Conceptual Foundation and Workflow

Leave-one-out cross-validation represents an extreme case of k-fold cross-validation where k equals the total number of observations (n) in the dataset. In LOOCV, the model is trained n times, each time using n-1 observations as the training set and the single remaining observation as the test set [15] [14]. This approach maximizes the training set size in each iteration, using nearly the entire dataset for model building while reserving only one sample for validation.

The LOOCV process follows a meticulous iterative workflow. For a dataset with n observations, the procedure cycles through each observation sequentially. In iteration i, the model is trained on all observations except the i-th one, which is held out as the test case. The trained model then predicts the outcome for this single excluded observation, and the prediction error is recorded. After cycling through all n observations, the performance metric is computed by averaging the prediction errors across all n iterations [15] [17]. This comprehensive process ensures that each data point contributes individually to the validation process while participating in the training phase for all other iterations.

Implementation Considerations

LOOCV offers the significant advantage of being almost unbiased as an estimator of model performance, since each training set contains n-1 observations, making it virtually identical to the full dataset [17]. This property is particularly valuable with small datasets, where reserving a substantial portion of data for testing (as in standard k-fold with low k) would severely limit the training information. The minimal reduction in training set size (just one observation) means that LOOCV provides the closest possible approximation to training on the entire available dataset.

However, LOOCV comes with substantial computational costs, as it requires fitting the model n times, once for each observation in the dataset. For large datasets, this process can become computationally prohibitive, especially with complex models that have lengthy training times [15] [14]. Fortunately, for certain model families such as linear regression, mathematical optimizations exist that allow LOOCV scores to be computed without explicitly refitting the model n times.

A more nuanced consideration with LOOCV is its variance properties. While initially counterintuitive, LOOCV can produce higher variance in performance estimation compared to k-fold with lower k values because the training sets across iterations are highly correlated—they share n-2 observations in common [18] [17]. This high overlap means that the model outputs across iterations are not independent, which can increase the variance of the averaged performance estimate, particularly for unstable models or datasets with influential outliers.

Comparative Analysis: k-Fold vs. LOOCV

Theoretical Comparison of Statistical Properties

The choice between k-fold cross-validation and LOOCV involves important trade-offs between bias and variance in performance estimation. LOOCV is approximately unbiased because each training set used in the iterations contains n-1 observations, nearly the entire dataset [17]. This makes it particularly valuable for small datasets where holding out a substantial portion of data for testing would significantly change the learning problem. In contrast, k-fold cross-validation with small k values (e.g., 5) introduces more bias because models are trained on substantially smaller datasets (e.g., 80% of the data for k=5), which may not fully represent the complexity achievable with the complete dataset.

The variance properties of these methods present a more complex picture. While intuition might suggest that LOOCV would have lower variance due to the extensive overlap between training sets, the high correlation between these training sets can actually result in higher variance for the performance estimate [18] [17]. Each LOOCV iteration produces a test error estimate based on a single observation, and these single-point estimates tend to be highly variable. In k-fold cross-validation, each test set contains multiple observations, producing more stable error estimates for each fold and potentially lower overall variance in the final averaged result, particularly with appropriate choice of k.

The relationship between the number of folds and the bias-variance tradeoff follows a generally consistent pattern. As k increases from 2 to n (LOOCV), the bias of the performance estimate decreases because each training set more closely resembles the full dataset [16]. However, the variance may follow a U-shaped curve, initially decreasing but then increasing again as k approaches n due to the increasing correlation between training sets. The optimal k value for minimizing total error (bias² + variance) typically falls between 5 and 20, depending on dataset size and model stability [18].

Empirical Comparison and Experimental Data

Empirical studies comparing k-fold and LOOCV have yielded insights into their practical performance characteristics. Simulation experiments on polynomial regression with small datasets (n=40) have demonstrated that increasing k from 2 to approximately 10 significantly improves both bias and variance, with minimal additional benefit beyond k=10 [18]. For larger datasets (n=200), the choice of k has less impact on both bias and variance, as even with k=10, the training set contains 90% of the data, closely approximating the full dataset.

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Validation Methods Across Dataset Sizes

| Characteristic | Small Dataset (n=40) | Large Dataset (n=2000) |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended Method | LOOCV or k=10 | k=5 or k=10 |

| Bias Concern | High with low k | Minimal with k≥5 |

| Variance Concern | Moderate with LOOCV | Low with k=5-10 |

| Computational Time | Manageable with LOOCV | Prohibitive with LOOCV |

| Stability of Estimate | Lower with LOOCV | Higher with k-fold |

In classification tasks using real-world neuroimaging data, research has shown that the statistical significance of model comparisons can be sensitive to the cross-validation configuration [19]. Studies comparing classifiers with identical predictive power found that higher k values in repeated cross-validation increased the likelihood of detecting statistically significant but spurious differences between models. This highlights the importance of selecting appropriate cross-validation schemes that align with both dataset characteristics and research goals.

The performance of these methods also depends on model stability. For stable models (e.g., linear regression with strong regularization), LOOCV typically performs well with low variance. For unstable models (e.g., complex decision trees or models sensitive to outliers), k-fold with moderate k (5-10) often provides more reliable performance estimates due to lower variance [18]. In healthcare applications using electronic health record data, subject-wise cross-validation (where all records from an individual are kept in the same fold) is particularly important to prevent data leakage and overoptimistic performance estimates [3].

Practical Application Guidelines

Selecting between k-fold and LOOCV requires careful consideration of multiple factors. For small datasets (typically n<100), LOOCV is generally preferred due to its lower bias, as it uses nearly all available data for training in each iteration [15] [17]. The computational burden remains manageable with small n, and the variance concerns are less pronounced than with larger datasets. For large datasets (n>1000), k-fold with k=5 or 10 provides the best balance, offering computational efficiency while maintaining low bias and variance in performance estimation [15] [14].

The nature of the research question should also guide method selection. For model selection and hyperparameter tuning, where the absolute performance estimate is less critical than identifying the best-performing configuration, k-fold with k=5-10 is typically sufficient and more computationally efficient [13] [3]. For final performance estimation of a selected model, particularly in contexts requiring precise error measurement (e.g., clinical prediction models), LOOCV or k-fold with higher k (10-20) may be warranted despite the computational cost.

Table 2: Cross-Validation Method Selection Guide

| Criterion | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Leave-One-Out CV |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Dataset Size | Medium to large (n>100) | Small (n<100) |

| Computational Efficiency | Higher (especially k=5-10) | Lower (trains n models) |

| Bias | Moderate (higher with small k) | Low |

| Variance | Moderate (depends on k) | Potentially higher |

| Model Stability | Better for unstable models | Better for stable models |

| Common Applications | Hyperparameter tuning, algorithm selection | Final performance estimation, small samples |

Domain-specific considerations further refine these guidelines. In healthcare applications with correlated data (e.g., multiple measurements from the same patient), subject-wise splitting is essential regardless of the chosen k value [3]. For imbalanced classification problems, stratified approaches that preserve class distributions across folds are recommended. In drug development contexts, where datasets may be small and costly to obtain, LOOCV often provides the most rigorous performance evaluation [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Evaluation Protocol for Cross-Validation Comparison

To empirically compare k-fold and LOOCV methodologies, researchers can implement a standardized evaluation protocol using publicly available datasets. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach suitable for classification tasks:

Dataset Selection and Preparation: Select a dataset with known ground truth labels, such as the Iris dataset (150 samples, 3 classes) [14]. Preprocess the data by shuffling and normalizing features to ensure comparability.

Model Selection: Choose a classification algorithm with potential for overfitting, such as Support Vector Machine with non-linear kernel or complex decision tree, to highlight differences between validation methods.

Cross-Validation Implementation:

- Implement k-fold cross-validation with k values of 5 and 10

- Implement LOOCV (k=n)

- For each method, ensure stratified sampling for classification problems

Performance Metrics: Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for each iteration. Compute mean and standard deviation across all iterations.

Statistical Analysis: Perform paired statistical tests (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA) to compare performance metrics across methods, accounting for multiple comparisons.

Bias-Variance Decomposition: Where possible, decompose the error into bias and variance components to quantitatively compare the trade-offs.

This protocol can be enhanced through repetition with different random seeds to assess the stability of results, and by testing with multiple datasets of varying sizes and characteristics to establish generalizable conclusions.

Computational Implementation Framework

Implementing a robust cross-validation framework requires attention to several technical considerations. The following Python code snippet illustrates the core implementation using scikit-learn:

For comprehensive experiments, researchers should incorporate the following elements:

- Multiple classification algorithms (e.g., logistic regression, random forests, neural networks)

- Varied dataset sizes through progressive sampling

- Multiple evaluation metrics appropriate to the domain

- Computation time tracking

- Statistical significance testing

Essential Computational Tools

Implementing rigorous cross-validation requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools. The following table outlines essential resources for researchers implementing cross-validation studies:

Table 3: Essential Tools for Cross-Validation Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Python ML library with CV implementations | KFold, LeaveOneOut, cross_val_score |

| Stratified Sampling | Maintains class distribution in folds | StratifiedKFold for classification problems |

| Parallel Processing | Accelerates k-fold computation | n_jobs=-1 in scikit-learn functions |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies model performance | Accuracy, F1-score, AUC-ROC, MSE, MAE |

| Statistical Tests | Compares CV results across methods | Paired t-test, McNemar's test, ANOVA |

Specialized Methodologies for Domain-Specific Applications

Different scientific domains require adaptations of standard cross-validation approaches:

Healthcare and Biomedical Research: Subject-wise cross-validation is essential when dealing with multiple measurements from the same patient to prevent data leakage [3]. Temporal splitting is necessary for longitudinal studies, where past data trains the model and future data tests it.

Drug Development: For bioanalytical method validation, cross-validation establishes equivalence between two measurement techniques by comparing results from incurred samples across the applicable concentration range [20]. The 90% confidence interval of the mean percent difference should fall within ±30% to demonstrate equivalence.

Neuroimaging and Biomedical Data: Given the high-dimensional nature of neuroimaging data (where features often exceed samples), nested cross-validation is recommended to prevent overfitting during both feature selection and model training [19]. The inner loop performs model selection while the outer loop provides performance estimation.

Cross-validation represents an essential methodology in the researcher's toolkit, providing robust assessment of model performance without requiring separate validation datasets. Through this comprehensive comparison of k-fold and leave-one-out cross-validation, we have elucidated their distinct characteristics, appropriate applications, and implementation considerations.

The choice between these methods hinges on the interplay between dataset size, computational resources, and the desired balance between bias and variance in performance estimation. K-fold cross-validation with k=5 or 10 offers a practical balance for most applications, particularly with medium to large datasets. Leave-one-out cross-validation provides nearly unbiased estimation for small datasets, despite potential variance concerns and computational costs.

Within the broader context of validation methodologies, both k-fold and LOOCV offer distinct advantages over bootstrap methods and single holdout validation, particularly through their structured approach to data partitioning and comprehensive usage of available samples. As artificial intelligence and machine learning continue to advance in scientific research and drug development, appropriate application of these cross-validation techniques will remain crucial for developing reliable, generalizable models that can truly deliver on their promise in critical applications.

Researchers should view cross-validation not as a one-size-fits-all procedure, but as a flexible framework requiring thoughtful implementation tailored to specific dataset characteristics, domain constraints, and research objectives. By applying the principles and guidelines outlined in this review, scientists can make informed decisions about validation strategies that enhance the reliability and interpretability of their predictive models.

In the pursuit of robust predictive models in drug development and scientific research, accurately evaluating model performance is paramount. Two foundational techniques for this purpose are cross-validation and bootstrapping. While both methods aim to provide a reliable measure of a model's generalizability, their methodologies, philosophical underpinnings, and optimal applications differ significantly. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two powerful resampling techniques, detailing their protocols, performance, and practical utility in research settings.

Conceptual Breakdown: Two Approaches to Resampling

At their core, both methods seek to estimate how a model trained on a finite dataset will perform on unseen data. They achieve this by creating multiple resamples from the original dataset, but their sampling strategies are fundamentally distinct.

Cross-Validation partitions the data into complementary subsets to systematically rotate which subset is used for validation [14] [21]. The most common implementation is k-Fold Cross-Validation, where the dataset is split into k equal-sized folds. The model is trained on k-1 folds and tested on the remaining fold, a process repeated k times so that each fold serves as the test set once [11]. The final performance metric is the average of the results from all k iterations.

Bootstrapping, in contrast, is a resampling technique that estimates the sampling distribution of a statistic by drawing samples with replacement from the original data [22] [23]. Each "bootstrap sample" is typically the same size as the original dataset. However, because sampling is done with replacement, any single bootstrap sample contains duplicates of some original data points and omits others [24]. The Out-of-Bag (OOB) data—the observations not selected in a bootstrap sample—can serve as a natural validation set [11].

The workflows for these two methods are illustrated below.

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Protocols

The conceptual differences lead to distinct experimental protocols and performance outcomes, which are summarized in the following table.

| Aspect | Cross-Validation | Bootstrapping |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Splits data into k subsets (folds) for training and validation [11]. | Samples data with replacement to create multiple bootstrap datasets [11]. |

| Primary Purpose | Estimate model performance and generalize to unseen data [11]. | Estimate the variability (e.g., standard error, confidence interval) of a statistic or model performance [22] [11]. |

| Key Advantage | Reduces overfitting by validating on unseen data; beneficial for model selection and tuning [11]. | Captures uncertainty in estimates; useful for assessing bias and variance; effective with small datasets [11] [24]. |

| Key Disadvantage | Computationally intensive for large k or large datasets [11]. | Can overestimate performance due to sample similarity; computationally demanding [11]. |

| Ideal Sample Size | Small to medium datasets [11]. | Particularly effective for small datasets [11]. |

| Bias-Variance Profile | Typically provides a lower-variance estimate [11]. | Can provide a lower-bias estimate as it uses a large portion of the data for each fit [11]. |

To ensure reliable and reproducible results, follow these structured protocols for each method.

Protocol 1: k-Fold Cross-Validation

- Partitioning: Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into k mutually exclusive folds of approximately equal size. For stratified k-fold, ensure the class distribution in each fold mirrors the entire dataset [14].

- Iterative Training & Validation: For each of the k iterations:

- Designate one fold as the validation set and the remaining k-1 folds as the training set.

- Train your predictive model (e.g., a classifier or regressor) on the training set.

- Use the trained model to make predictions on the validation set and compute the desired performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score).

- Performance Estimation: Calculate the final model performance estimate by averaging the performance metrics from all k iterations. The standard deviation of these metrics can inform performance stability [21].

Protocol 2: Bootstrapping for Model Evaluation

- Bootstrap Sample Generation: Generate B bootstrap samples (a common value for B is 1,000 or 10,000) by randomly drawing n observations from the original dataset of size n with replacement [23] [24].

- Model Fitting and OOB Evaluation: For each bootstrap sample:

- Train your model on the bootstrap sample.

- Identify the Out-of-Bag (OOB) data points—those not included in the bootstrap sample.

- Use the OOB data as a validation set to compute the model's performance metric.

- Aggregation and Inference: Aggregate the performance metrics from all B bootstrap samples. The mean of these metrics provides an estimate of model performance, while their standard deviation estimates the variability (standard error) of the performance estimate [11]. A confidence interval can be derived by taking the percentiles (e.g., 2.5th and 97.5th for a 95% interval) of the bootstrap distribution [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing these methods in practice requires a set of computational "reagents." The following table details key solutions for implementing cross-validation and bootstrapping in a Python environment, using libraries like scikit-learn.

| Research Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

sklearn.model_selection.train_test_split |

Quickly splits data into initial training and testing sets, forming the basis for a holdout validation method [21]. |

sklearn.model_selection.KFold |

Creates the k non-overlapping folds required for the k-Fold Cross-Validation protocol [14] [21]. |

sklearn.model_selection.cross_val_score |

Automates the entire k-Fold Cross-Validation workflow, from splitting and training to scoring, returning the performance score for each fold [14] [21]. |

sklearn.utils.resample |

A fundamental function for generating bootstrap samples by drawing random samples from a dataset with replacement [25]. |

numpy.random.choice |

Can be used to generate indices for bootstrap samples, providing fine-grained control over the resampling process. |

Interpretation Guidelines and Decision Framework

Choosing between cross-validation and bootstrapping depends on the research goal, dataset characteristics, and computational resources. The following diagram outlines a decision pathway to help select the appropriate method.

Key Considerations for Your Research:

For Model Selection and Tuning: Cross-validation is generally the preferred method. It provides a reliable and straightforward way to compare different models or hyperparameter configurations, especially when dealing with balanced datasets of small to medium size [11]. Its structured approach to using all data for validation minimizes the risk of a misleading evaluation due to an unfortunate single data split.

For Uncertainty Quantification: Bootstrapping is unparalleled when the research objective is to understand the stability and variability of a model's performance or an estimated parameter [22] [11]. It is particularly valuable in small-sample studies common in early-stage drug development, where collecting more data is difficult. A bootstrapped confidence interval offers a data-driven, non-parametric way to communicate the precision of your findings.

Understanding Limitations: No method is a panacea. Cross-validation can be computationally expensive for large k or complex models [11]. Bootstrapping does not create new information; it only simulates the sampling process [26]. If the original sample is small or biased, the bootstrap estimates will also be biased, as it treats the sample as a proxy for the population [22] [26].

In the development of clinical prediction models, whether for disease diagnosis, patient risk stratification, or treatment response prediction, two fundamental aspects of performance must be evaluated: discrimination and calibration [27]. Discrimination refers to a model's ability to differentiate between positive and negative cases, typically quantified by the C-statistic or Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) [27]. Calibration, often termed the "Achilles heel" of predictive analytics, measures how well predicted probabilities align with actual observed probabilities [28]. Within the broader framework of comparing cross-validation and bootstrap validation methods, understanding these metrics and their proper assessment is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to build reliable, clinically applicable models.

The C-statistic represents the probability that a randomly selected patient who experienced an event has a higher predicted risk than a patient who did not experience the event [29]. It ranges from 0.5 (no better than random chance) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) [27]. Calibration performance ensures that a predicted probability of 20% corresponds to an actual event rate of approximately 20% within a subgroup of patients [28]. These metrics complement each other, as a model can have excellent discrimination but poor calibration, potentially leading to harmful clinical decisions if implemented without proper validation [28].

Theoretical Foundations of Discrimination and Calibration

The C-Statistic/AUC: Concept and Interpretation

The C-statistic, equivalent to the AUC, is a rank-based measure that evaluates how well a model's predictions order patients by their risk [29]. In practical terms, an AUC of 0.8 means that for 80% of all possible pairs of patients where one experienced the event and the other did not, the model assigned a higher risk to the patient with the event [27]. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve visualizes this relationship by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity) across all possible classification thresholds [27].

While valuable, the AUC has important limitations. It may overestimate performance in imbalanced datasets where true negatives substantially outnumber true positives [27]. Additionally, AUC measures discrimination but provides no information about calibration [30]. In clinical contexts where absolute risk estimates drive decision-making, this limitation becomes particularly significant, as models with similar AUC values may have dramatically different calibration performance [28].

Calibration: Levels and Assessment Methods

Calibration performance exists at multiple levels of stringency, from mean calibration to strong calibration [28]. Mean calibration (or calibration-in-the-large) compares the average predicted risk with the overall event rate. Weak calibration assesses whether the model neither over- nor underestimates risk on average and whether risk estimates are appropriately extreme, typically evaluated through the calibration intercept (target value: 0) and slope (target value: 1) [28]. Moderate calibration means that estimated risks correspond to observed proportions across the risk spectrum, visualized through calibration curves [28]. Strong calibration, requiring perfect correspondence for every predictor combination, is considered a utopic goal in practice [28].

Calibration curves plot predicted probabilities against observed event proportions, with points falling along the diagonal indicating perfect calibration [30]. These curves are typically created by grouping patients into risk bins (e.g., 0-10%, 10-20%, etc.) and calculating the observed event rate within each bin [27]. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test, while historically used for calibration assessment, has numerous drawbacks including artificial grouping, uninformative P values, and low statistical power, leading experts to recommend against its use [28].

Relationship Between Discrimination and Calibration

Discrimination and calibration represent distinct aspects of model performance that do not necessarily correlate [30]. A model can have excellent discrimination but poor calibration, particularly when overfitting occurs during development [28]. Similarly, a model with moderate discrimination might have superior calibration, potentially making it more clinically useful than a competitor with higher AUC but poor calibration [28].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Discrimination and Calibration

| Aspect | Discrimination | Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Ability to differentiate positives from negatives | Agreement between predicted and observed probabilities |

| Primary Metric | C-statistic/AUC | Calibration slope and intercept |

| Visualization | ROC curve | Calibration curve |

| Clinical Importance | Identifying high-risk patients | Accurate risk estimation for decision-making |

| Target Value | 1.0 | Slope=1, Intercept=0 |

Resampling Methods for Metric Validation

Cross-Validation Approaches

Cross-validation is a widely used technique for assessing model performance while correcting for the optimism bias that occurs when models are evaluated on the same data used for training [31]. In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is randomly divided into k subsets of approximately equal size. The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. The performance estimates from the k validation folds are then averaged to produce a more robust assessment of how the model might perform on external data [32].

Repeated cross-validation, which performs k-fold cross-validation multiple times with different random splits, reduces variance in the performance estimates while maintaining low bias [32]. Leave-one-out cross-validation represents an extreme case where k equals the sample size, but this approach tends to be overoptimistic, particularly with smaller datasets [32]. The primary advantage of cross-validation is its relatively low bias, though k-fold methods can have substantial variance, especially with smaller datasets [32].

Bootstrap Validation Methods

Bootstrap validation involves repeatedly resampling the original dataset with replacement to create multiple bootstrap samples [33]. The model is fitted on each bootstrap sample and evaluated on both the bootstrap sample and the original dataset [29]. The difference between these performance estimates represents the "optimism" of the model, which can be subtracted from the apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected estimate [33].

Three main bootstrap-based bias correction methods exist: Harrell's bias correction, the .632 estimator, and the .632+ estimator [29]. These methods vary in their approach to addressing the optimism bias, with the .632+ method specifically designed to perform better in small sample settings and with complex models [29]. Bootstrap methods tend to drastically reduce variance compared to cross-validation but can produce more pessimistic estimates, though advanced variants like the .632 and .632+ rules address this bias [32].

Comparative Performance of Resampling Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Cross-Validation and Bootstrap Validation Methods

| Characteristic | Cross-Validation | Bootstrap Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Bias | Lower bias | Higher bias (pessimistic) |

| Variance | Higher variance (especially k-fold) | Lower variance |

| Computational Cost | Moderate to high (depends on k and repeats) | High (typically 200+ replicates) |

| Small Sample Performance | Problematic due to data splitting | Better, but requires bias correction |

| Recommended Variants | Repeated k-fold | .632+ bootstrap |

| Primary Use Case | Model selection | Error estimation for final model |

Under relatively large sample settings (typically events per variable ≥ 10), the three bootstrap-based methods (Harrell's, .632, and .632+) perform comparably well [29]. However, in small sample settings, all methods exhibit biases, with Harrell's and .632 methods showing overestimation biases when event fraction becomes larger, while the .632+ method demonstrates slight underestimation bias when event fraction is very small [29]. Although the bias of the .632+ estimator is relatively small, its root mean squared error is sometimes larger than the other methods, particularly when regularized estimation methods are used [29].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Assessment

Workflow for Bootstrap Validation of Discrimination and Calibration

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for bootstrap validation of both discrimination and calibration metrics:

Detailed Bootstrap Algorithm for Performance Assessment

The standard bootstrap validation protocol follows these specific steps, typically implemented with 200 or more bootstrap replicates [33]:

- Resample the Data: Draw a bootstrap sample of size n (where n is the original sample size) from the original dataset with replacement [33].

- Fit the Model: Refit the entire model development process (including any variable selection or hyperparameter tuning) using the bootstrap sample [29].

- Evaluate Training Performance: Calculate the performance metrics (both discrimination and calibration) of the refit model on the bootstrap sample itself [33]. For discrimination, this might include Somers' D or the C-statistic; for calibration, this could include the calibration slope or Brier score.

- Evaluate Test Performance: Calculate the performance metrics of the same refit model on the original dataset [33].

- Calculate Optimism: Compute the difference between the training and test performance estimates for each metric [33].

- Repeat Process: Repeat steps 1-5 a large number of times (typically 200 or more) to build a distribution of optimism estimates [33].

- Calculate Bias-Corrected Estimates: Average the optimism estimates across all bootstrap replicates and subtract this average from the apparent performance (performance of the original model on the original data) to obtain bias-corrected performance estimates [33].

Cross-Validation Protocol for Comparative Assessment

For k-fold cross-validation assessment of discrimination and calibration:

- Randomly Partition Data: Split the dataset into k subsets (folds) of approximately equal size.

- Iterative Training and Validation: For each fold i (i = 1 to k): a. Retain fold i as the validation data, and use the remaining k-1 folds as training data. b. Fit the model development process (including variable selection and hyperparameter tuning) using only the training data. c. Calculate discrimination and calibration metrics on the validation data (fold i).

- Aggregate Performance Estimates: Average the performance metrics across all k folds to obtain the cross-validated performance estimate.

- Repeat for Stability: For increased stability, repeat the entire process multiple times with different random partitions (repeated cross-validation) and average the results.

Quantitative Comparison of Validation Methods

Performance Under Varying Sample Sizes

Simulation studies comparing resampling methods across different sample sizes and data conditions provide crucial insights for method selection. A comprehensive re-evaluation of bootstrap methods examined their performance across various model-building strategies, including conventional logistic regression, stepwise selection, Firth's penalized likelihood, ridge, lasso, and elastic-net regression [29].

Table 3: Performance of Bootstrap Methods by Sample Size and Event Fraction

| Condition | Harrell's Method | .632 Method | .632+ Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Samples (EPV ≥ 10) | Low bias, good performance | Low bias, good performance | Low bias, good performance |

| Small Samples with Large Event Fraction | Overestimation bias | Overestimation bias | Small bias |

| Small Samples with Small Event Fraction | Moderate overestimation | Moderate overestimation | Slight underestimation |

| With Regularized Methods (All Samples) | Good RMSE | Good RMSE | Larger RMSE |

Empirical Results from Clinical Datasets

In practical applications using real clinical data, bootstrap validation typically produces slightly lower, more conservative performance estimates compared to apparent performance. For example, in a study predicting low infant birth weight using logistic regression with three predictors, the apparent Somers' D was 0.438, while the bootstrap-corrected estimate was 0.425, representing a modest but important reduction in estimated performance [33].

Similar patterns emerge for calibration metrics, where bootstrap validation often reveals stronger miscalibration than apparent performance assessments, particularly for models developed using complex algorithms with limited events per variable. This bias correction becomes increasingly important as model complexity rises relative to sample size.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Tools for Discrimination and Calibration Assessment

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Primary platform for analysis | Comprehensive statistical capabilities and specialized packages |

| rms Package (R) | Regression modeling strategies | Implements bootstrap validation via validate() function |

| glmnet Package (R) | Regularized regression | Ridge, lasso, and elastic-net with built-in cross-validation |

| Hmisc Package (R) | Statistical analysis | somers2() function for Somers' D and C-statistic |

| boot Package (R) | Bootstrap methods | General bootstrap functionality with boot() function |

| CalibratedClassifierCV (Python) | Probability calibration | Platt scaling and isotonic regression for calibration |

| PROC LOGISTIC (SAS) | Logistic regression | Offers bootstrapping and cross-validation options |

Recommendations for Practice and Reporting

Method Selection Guidelines

Based on comprehensive simulation studies and empirical evaluations, the following recommendations emerge for selecting validation approaches:

- For Model Selection and Comparison: Use repeated k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5- or 10-fold repeated 5-10 times) due to its lower bias, which is crucial when comparing competing modeling approaches [32].

- For Final Model Assessment: Once a final model is selected, apply bootstrap validation (preferably the .632+ method) to obtain the least biased estimates of future performance, particularly for discrimination metrics like the C-statistic [29].

- For Small Samples: The .632+ bootstrap method generally performs best with small samples, except when regularized estimation methods are used, where Harrell's method may be preferable [29].

- For Calibration Assessment: Always report both apparent and bootstrap-corrected calibration curves, along with calibration slope and intercept, as calibration is particularly vulnerable to overoptimism [28].

Comprehensive Reporting Standards

No single metric sufficiently captures model performance, particularly for clinical applications [27]. The Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) guidelines recommend reporting both discrimination and calibration measures with appropriate uncertainty estimates [28]. When presenting model performance, researchers should include:

- Discrimination Metrics: Report both apparent and optimism-corrected C-statistics with confidence intervals.

- Calibration Metrics: Include calibration slope, intercept, and visualization through calibration curves.

- Validation Method: Clearly specify the resampling method used (bootstrap or cross-validation), including the number of replicates or folds and any specific variants employed.

- Clinical Utility: When possible, include decision curve analysis to demonstrate the net benefit of the model across clinically relevant risk thresholds [27].

The combination of proper performance metrics with appropriate validation methods provides the foundation for developing reliable clinical prediction models that can genuinely enhance patient care and drug development processes.

Practical Implementation: Applying Techniques to Clinical and Omics Data

Implementing k-Fold and Stratified Cross-Validation for Imbalanced Datasets

In the field of machine learning, particularly in scientific domains such as drug development, accurately evaluating model performance is paramount. This challenge becomes particularly acute when working with imbalanced datasets, where class distributions are significantly skewed. In such scenarios, standard validation techniques can yield misleading results, potentially compromising scientific conclusions. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of k-fold and stratified cross-validation methods for imbalanced datasets, contextualized within broader research comparing cross-validation versus bootstrap validation approaches.

The fundamental problem with imbalanced data—where one class significantly outnumbers others—is that standard k-fold cross-validation often creates unrepresentative folds. Some folds may contain few or no examples from the minority class, leading to unreliable performance estimates [34]. This issue is especially prevalent in real-world applications like fraud detection, medical diagnostics, and rare disease identification [35] [36]. Stratified k-fold cross-validation addresses this limitation by preserving the original class distribution in each fold, ensuring more reliable model evaluation [14] [37].

Theoretical Foundations: k-Fold vs. Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation

Standard k-Fold Cross-Validation

K-fold cross-validation is a fundamental resampling technique used to assess model generalization. The procedure involves:

- Randomly dividing the dataset into k equal-sized folds

- Using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for testing

- Repeating this process k times, with each fold serving as the test set once

- Averaging the results across all k iterations to produce a final performance estimate [11] [14]

While this approach generally provides a more robust performance estimate than a single train-test split, it assumes that random partitioning creates representative subsets—an assumption that often fails with imbalanced data [34].

Stratified k-Fold Cross-Validation

Stratified k-fold cross-validation modifies the standard approach by ensuring that each fold maintains approximately the same percentage of samples for each class as the complete dataset [14] [37]. Mathematically, this means that for each fold F_i and class c, the proportion of class c in fold i should approximate the overall class proportion in the dataset [35]:

P(fold_i ∈ c) ≈ P(dataset ∈ c)

This preservation of class distribution addresses the critical weakness of standard k-fold cross-validation when applied to imbalanced datasets, particularly preventing scenarios where some folds contain no representatives of minority classes [38] [34].

Methodological Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the key differences in how standard k-fold and stratified k-fold cross-validation create data partitions:

Comparative Theoretical Properties

Table 1: Theoretical comparison of standard k-fold and stratified k-fold cross-validation

| Aspect | Standard k-Fold CV | Stratified k-Fold CV |

|---|---|---|

| Partitioning Strategy | Random division without regard to class labels | Preserves original class distribution in each fold |

| Handling Imbalance | Poor; can create folds with missing minority classes | Excellent; ensures minority class representation |

| Bias-Variance Tradeoff | Higher bias with severe imbalance | More balanced bias-variance profile |

| Performance Estimate Reliability | Unreliable with imbalance due to fold variability | More stable and reliable across runs |

| Computational Complexity | Same computational overhead as stratified approach | Identical to standard k-fold [39] |

| Data Requirements | Requires large datasets to ensure minority representation | Effective even with small minority classes |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Experimental Design for Method Evaluation

To objectively compare standard k-fold versus stratified k-fold cross-validation for imbalanced datasets, researchers should implement the following experimental protocol:

Dataset Selection: Utilize multiple datasets with varying degrees of class imbalance, from moderately skewed (e.g., 70:30) to highly imbalanced (e.g., 99:1) distributions [36] [34].

Classifier Variety: Employ diverse classification algorithms including Decision Trees (DTree), k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) to ensure generalizable conclusions [36].

Evaluation Metrics: Beyond accuracy, calculate metrics sensitive to imbalance: precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) [35] [36].

Cross-Validation Configuration: Implement both standard and stratified k-fold cross-validation with consistent fold numbers (typically k=5 or k=10) for direct comparison.

Statistical Analysis: Perform multiple runs with different random seeds and use statistical tests to determine significance of observed differences.

Implementation Framework

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for comparing validation strategies:

Experimental Results and Performance Metrics

A comprehensive study comparing SCV and Distribution Optimally Balanced SCV (DOB-SCV) across 420 datasets provides compelling evidence for stratification benefits [36]. The research involved several sampling methods and multiple classifiers (DTree, kNN, SVM, and MLP).

Table 2: Performance comparison (F1 scores) between standard and stratified cross-validation across classifier types

| Classifier | Standard k-Fold CV | Stratified k-Fold CV | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree (DTree) | 0.72 ± 0.15 | 0.78 ± 0.11 | +8.3% |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | 0.68 ± 0.18 | 0.74 ± 0.13 | +8.8% |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 0.71 ± 0.16 | 0.76 ± 0.12 | +7.0% |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 0.79 ± 0.10 | +8.2% |

Table 3: Impact of stratification on evaluation metric stability (lower standard deviation indicates better reliability)

| Evaluation Metric | Standard k-Fold CV | Stratified k-Fold CV | Reduction in Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.9200 ± 0.0214 | 0.9200 ± 0.0084 | 60.7% |

| Precision | 0.6635 ± 0.1420 | 0.6635 ± 0.0880 | 38.0% |

| Recall | 0.4657 ± 0.1212 | 0.4657 ± 0.0712 | 41.3% |

| F1-Score | 0.5431 ± 0.1109 | 0.5431 ± 0.0609 | 45.1% |

| AUC | 0.8510 ± 0.0350 | 0.8510 ± 0.0190 | 45.7% |

The experimental results demonstrate that stratified k-fold cross-validation not only maintains comparable accuracy to standard approaches but also significantly reduces variance in performance estimates across folds [35] [36]. This increased reliability is particularly valuable in research settings where consistent evaluation is crucial for model selection.

Computational Tools and Libraries

Table 4: Essential research reagents and computational tools for cross-validation experiments

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| StratifiedKFold | Python class (scikit-learn) | Creates stratified folds preserving class distribution | from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedKFold |

| crossvalscore | Python function (scikit-learn) | Performs cross-validation with scoring | scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=stratified_kfold) |

| Precision, Recall, F1 | Evaluation metrics | Performance assessment beyond accuracy | from sklearn.metrics import precision_score, recall_score, f1_score |

| StratifiedShuffleSplit | Python class (scikit-learn) | Creates stratified train/test splits | from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedShuffleSplit |

| Imbalanced-learn | Python library | Specialized algorithms for imbalanced data | from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE |

Implementation Protocol

For researchers implementing stratified cross-validation, the following code framework demonstrates the practical application:

This implementation highlights how stratified cross-validation provides more stable performance estimates—the standard deviation of metrics is typically significantly reduced compared to standard k-fold cross-validation [35].

Contextualizing Within Broader Validation Research: Cross-Validation vs. Bootstrapping

Bootstrap Validation Methods

Bootstrapping represents an alternative approach to model validation, particularly relevant for imbalanced datasets. This technique involves:

- Drawing multiple bootstrap samples (typically B > 1000) from the original dataset with replacement

- Training a model on each bootstrap sample

- Evaluating performance on out-of-bag (OOB) observations not included in the bootstrap sample

- Aggregating results across all bootstrap samples [11] [4]

Advanced bootstrap variants like the .632+ bootstrap method have been developed specifically to address bias in performance estimation, potentially offering advantages for small sample sizes or severe imbalance [4].

Comparative Analysis of Resampling Methods

Table 5: Cross-validation versus bootstrapping for imbalanced data validation

| Characteristic | k-Fold Cross-Validation | Stratified k-Fold CV | Bootstrap Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Partitioning | Mutually exclusive folds | Mutually exclusive folds with stratification | Sampling with replacement |

| Handling Imbalance | Poor without stratification | Excellent | Moderate with stratified variants |

| Bias-Variance Profile | Lower variance, potential bias with imbalance | Balanced bias-variance | Lower bias, potentially higher variance |

| Computational Load | Trains k models | Trains k models | Trains B models (typically B=1000+) |

| Performance Estimate | Average across folds | Average across stratified folds | Average across bootstrap samples |

| Optimal Use Case | Balanced datasets or large samples | Imbalanced datasets of any size | Small datasets or variance estimation |

Research indicates that no single validation method dominates all scenarios. While stratified k-fold cross-validation generally performs well for imbalanced classification problems, the .632+ bootstrap method may be superior in situations with very small sample sizes or when estimating performance variance is prioritized [4].

Based on comprehensive experimental evidence and theoretical analysis, stratified k-fold cross-validation represents the superior approach for evaluating classifiers on imbalanced datasets across most research scenarios, particularly in scientific fields like drug development.

The key advantages of stratified k-fold cross-validation include:

More Reliable Performance Estimates: By preserving class distributions across folds, stratification provides more consistent and trustworthy evaluation metrics [36] [34].

Reduced Variance: Experimental results demonstrate significantly lower standard deviations in performance metrics with stratified approaches compared to standard k-fold cross-validation [35] [36].

Practical Implementation: Stratified k-fold cross-validation requires no additional computational resources compared to standard k-fold approaches while offering substantially improved reliability [39] [37].

For researchers working with severely imbalanced datasets or very small sample sizes, bootstrap methods (particularly the .632+ variant) may warrant consideration as complementary validation approaches [4]. However, for most imbalanced classification scenarios in scientific research, stratified k-fold cross-validation should be regarded as the gold standard for model evaluation and selection.

In the broader research on model validation techniques, the debate between cross-validation and bootstrap validation centers on their approaches to estimating true model performance. While cross-validation systematically partitions data into training and testing folds, bootstrap methods resample with replacement from the original dataset to create multiple simulated datasets. Within bootstrap validation, three specialized variants have emerged as particularly effective for correcting the optimism bias (the tendency for models to perform better on training data than on new data): Harrell's bootstrap optimism correction, the .632 bootstrap, and the .632+ bootstrap [40] [41]. These methods are especially valuable in drug development and clinical research where dataset sizes may be limited and accurate performance estimation is critical for regulatory decision-making [42].

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Mechanisms

Core Bootstrap Principles

Bootstrap validation operates on the principle that the observed dataset represents the best available approximation of the underlying population. By repeatedly sampling with replacement from the original data, bootstrap methods create multiple simulated datasets that capture the variability inherent in the sampling process [43]. The fundamental insight is that the empirical distribution of the observed data can serve as a proxy for the true population distribution, allowing researchers to estimate how model performance might vary across different samples from the same population [41].

A key mathematical property underpinning these methods is that each bootstrap sample contains approximately 63.2% of the unique observations from the original dataset. This occurs because when sampling n observations with replacement, the probability that any specific observation is included in a bootstrap sample is approximately 1 - (1 - 1/n)^n ≈ 1 - e^(-1) ≈ 0.632 [41]. This property directly informs the .632 and .632+ estimators and their attempts to balance between overly optimistic and pessimistic performance estimates.

Method-Specific Algorithms

Harrell's Bootstrap Optimism Correction follows a structured approach to estimate and correct for optimism [40]. First, fit the model to the original dataset and calculate the apparent performance (e.g., C-statistic). Then, for each bootstrap sample, fit the model to the bootstrap sample, calculate performance on the bootstrap sample, and calculate performance on the original dataset. The optimism is defined as the difference between bootstrap performance and original data performance. The optimism-corrected performance equals the original apparent performance minus the average optimism across all bootstrap samples.

The .632 Bootstrap Estimator addresses the upward bias in Harrell's method by combining information from both the training and out-of-bag samples [41]. This method calculates the bootstrap out-of-sample error (mean error when applied to out-of-bag samples) and the in-sample error (error on the original training set). The final .632 estimate is a weighted average: 0.632 × bootstrap out-of-sample error + 0.368 × in-sample error.