Density Functional Theory for Catalyst Design: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in catalyst design and analysis, tailored for researchers and development professionals.

Density Functional Theory for Catalyst Design: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in catalyst design and analysis, tailored for researchers and development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of DFT for elucidating catalytic mechanisms and electronic structures. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications, including the integration of machine learning and generative models for accelerated discovery. The article also addresses critical challenges in computational efficiency and accuracy, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it covers validation frameworks that combine theoretical predictions with experimental data, establishing DFT as an indispensable tool for rational catalyst development in energy and biomedical applications.

Understanding the Core: How DFT Reveals Catalytic Mechanisms and Electronic Structures

Theoretical Foundations of Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a powerful first-principles computational method that has firmly established itself as a cornerstone in modern catalytic research due to its optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost [1] [2]. Unlike wavefunction-based theories that depend on 3N variables (where N is the number of electrons), DFT utilizes the electron density, ρ(r), which is a function of only three spatial coordinates, making it computationally feasible for studying large systems relevant to catalysis [2]. The entire field rests on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which state that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all properties of a system, including energy and wavefunction [2]. The practical implementation of DFT occurs through the Kohn-Sham equations, which map the complex interacting system of electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that generate the same density [1].

In the context of catalysis, DFT's significance stems from its ability to elucidate atomic-scale phenomena that are often difficult or impossible to probe experimentally [3] [2]. Computational modeling provides crucial insights into reaction mechanisms, active site characterization, and electronic structure information, which collectively inform rational catalyst design strategies [4] [5]. For electrocatalytic processes such as the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), and carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR), DFT enables the calculation of key descriptors including adsorption energies, activation energy barriers, and d-band centers, which correlate strongly with catalytic activity and selectivity [5] [6].

DFT Computational Protocols for Catalytic Systems

Method Selection and Functional Recommendations

The reliability of DFT results critically depends on the chosen methodological approximations. A best-practice approach involves careful selection of the exchange-correlation functional, basis set, and consideration of system-specific properties [1]. The following table summarizes recommended computational protocols for different catalytic applications:

Table 1: Recommended DFT Protocols for Catalytic Studies

| Application Focus | Recommended Functional | Recommended Basis Set | Key Considerations | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Catalysis (Structure, Reaction Energies) [1] | B97M-V, r²SCAN-3c | def2-SVPD | Include dispersion corrections (D3); Account for solvation effects | Homogeneous organometallic complexes, reaction mechanisms |

| Surface Adsorption & Reactivity [7] | M06-2X | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | Use for single-point energy calculations on optimized geometries | Adsorption energies, activation barriers on surfaces |

| Initial Geometry Optimization [7] | B3LYP | 6-31+G(d,p) | Often used as initial step in multi-level protocols; Apply counterpoise correction for BSSE | Pre-optimization of catalyst and adsorbate structures |

| Benchmarked LDPE System Protocol [7] | M06-2X/6-311+G(3df,2p)//B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | Validated against experimental hydrogen abstraction and monomer reactivity | Free radical polymerization, chain transfer agents |

For periodic systems such as extended surfaces, nanoparticles, and two-dimensional materials, plane-wave basis sets are typically employed in conjunction with projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials [4] [2]. A common setup includes a plane-wave energy cutoff of 400-500 eV and k-point sampling to ensure numerical convergence [4]. It is crucial to avoid outdated default methods such as B3LYP/6-31G*, which lack dispersion corrections and suffer from basis set superposition error, potentially leading to qualitatively incorrect results [1].

Workflow for Catalytic Property Calculation

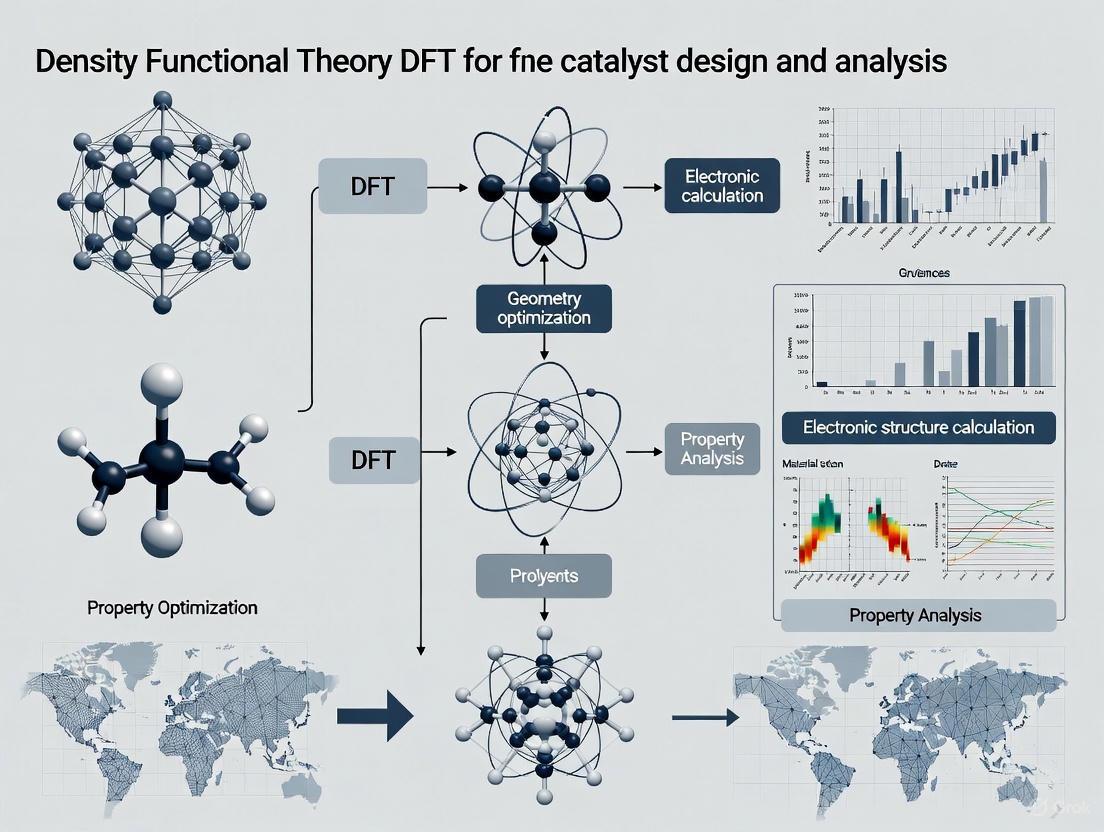

The process of evaluating catalytic properties involves a structured workflow that ensures reliability and computational efficiency. The diagram below illustrates a generalized DFT calculation protocol for catalysis:

This workflow underpins the calculation of key catalytic descriptors. For instance, the hydrogen adsorption energy (ΔEH), a critical descriptor for HER catalysts, is calculated as ΔEH = Ecatalyst+H - Ecatalyst - ½EH2, where E denotes the DFT-computed total energies [4] [6]. Similarly, activation energy barriers for reaction steps are determined through transition state optimization and validated by frequency analysis to ensure the presence of one imaginary frequency [2].

Advanced Integration: DFT with Machine Learning

The exploration of vast compositional spaces in multimetallic catalysts presents a formidable challenge for conventional DFT due to prohibitive computational costs [4] [8]. Active learning frameworks that synergistically combine DFT with machine learning (ML) have emerged as a transformative solution [4] [6] [9]. In this paradigm, a ML model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression) is trained on a limited set of DFT calculations and then used to predict properties across a much larger design space, while strategically selecting the most informative data points for subsequent DFT validation [4].

This approach was successfully demonstrated for Pt-Ru-Cu-Ni-Fe multimetallic HER catalysts, where an active learning framework navigating 390,625 possible binding sites required only 600 DFT calculations to identify optimal compositions, which were subsequently experimentally validated [4]. Similarly, for single-atom catalysts (SACs) on graphyne supports, ML models utilizing descriptors such as d-band center, metal binding height, and bond lengths can efficiently predict HER activity, guiding the discovery of candidates surpassing commercial Pt/C catalysts [9].

The integrated DFT-ML catalyst design workflow can be visualized as follows:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Table 2: Key Computational "Reagents" and Tools for DFT Catalysis Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Catalysis Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functional [1] [2] | Approximates quantum mechanical electron exchange and correlation effects; Critical for accuracy | M06-2X (metals, kinetics), B97M-V (general purpose), RPBE (surfaces) |

| Atomic Basis Set / Plane Waves [1] [2] | Mathematical functions to represent electron orbitals; Determines computational cost/accuracy balance | def2-series (molecules), Plane-wave + PAW (periodic surfaces) |

| Dispersion Correction [1] | Accounts for van der Waals forces, essential for adsorption phenomena | D3, D3(BJ), VV10 |

| Solvation Model [2] | Mimics solvent effects in electrochemical interfaces and homogeneous catalysis | PCM, SMD, VASPsol |

| Catalytic Descriptor [4] [6] [9] | Quantitative metric correlating with catalytic activity; Enables rapid screening | d-band center, adsorption energy, Bader charge, ICOHP |

Application in Catalyst Design: A Case Study on HER Catalysts

The practical application of DFT protocols is exemplified by the design of multimetallic HER catalysts. The standard computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model allows for the calculation of hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH) as an activity descriptor, where ΔGH ≈ 0 signifies optimal catalytic activity [4] [6]. Using the active learning framework described in Section 3, researchers identified specific high-performance compositions from a five-element (Pt, Ru, Cu, Ni, Fe) design space [4].

The experimental validation protocol involved synthesizing the predicted alloys via the carbothermal shock method, followed by electrochemical testing to measure HER activity [4]. The consistency between computational predictions and experimental results underscores the predictive power of a well-parameterized DFT protocol. This integrated approach demonstrates a significant reduction in both computational resource requirements and experimental development time, establishing a robust pathway for the rational design of complex catalytic materials.

Probing Reaction Pathways and Key Intermediates

The rational design of high-performance catalysts is a cornerstone of modern sustainable chemistry, crucial for processes ranging from renewable energy storage to greenhouse gas mitigation. A profound understanding of reaction mechanisms—specifically, the probing of reaction pathways and the characterization of key intermediates—is essential for this endeavor. While experimental techniques often struggle to directly observe transient species and transition states, Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as a powerful computational tool that provides atomic-level insights into these elusive aspects of catalytic cycles [2]. By calculating the energy landscape of reactions, DFT allows researchers to identify rate-determining steps, validate reaction mechanisms, and establish structure-activity relationships, thereby accelerating the development of more efficient and selective catalysts [10] [6]. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for using DFT to probe reaction pathways and key intermediates, framed within the broader context of catalyst design and analysis.

Theoretical Background and Key Concepts

DFT simplifies the many-body Schrödinger equation by using the electron density, ρ(r), as the fundamental variable, making computational studies of complex catalytic systems feasible [2]. The reliability of DFT results, however, depends critically on the chosen approximations and the model system.

In catalysis, a primary objective is mapping the Potential Energy Surface (PES), which describes the system's energy as a function of atomic coordinates. Key points on the PES include:

- Intermediates (IM): Local energy minima representing stable chemical species along the reaction coordinate.

- Transition States (TS): First-order saddle points on the PES that connect two intermediates and represent the highest energy point along the reaction pathway. The energy difference between the reactant and the transition state defines the activation energy barrier.

- Reaction Energy: The total energy change from reactants to products.

The Rate-Determining Step (RDS) is the elementary reaction with the highest activation energy barrier, which dictates the overall kinetics of the catalytic cycle. Identifying the RDS is a key outcome of probing reaction pathways.

Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing the Catalytic Model and Initial Setup

Objective: To construct a physically realistic and computationally efficient model of the catalytic system for subsequent analysis.

Model Selection: Choose an appropriate model for the active site.

- For homogeneous catalysis or Single-Atom Catalysts (SACs), use a molecular cluster model that adequately represents the coordination environment [2] [11].

- For heterogeneous catalysis, employ a periodic slab model. A supercell with sufficient vacuum space (typically > 10 Å) is required to prevent interactions between periodic images. The choice of crystal facet (e.g., (111), (110)) is critical, as reactivity is often facet-dependent [6].

Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the clean catalyst model and all isolated reactant molecules to their ground state. This provides a reference energy structure.

Adsorption Configuration Sampling: For each reaction intermediate, systematically explore potential adsorption configurations (e.g., atop, bridge, hollow sites on surfaces) on the catalyst model. Optimize each configuration to find the most stable adsorption geometry.

Protocol 2: Locating Intermediates and Transition States

Objective: To identify and characterize all stable intermediates and the transition states that connect them.

Intermediate Optimization: Using the most stable adsorption configurations from Protocol 1, perform full geometry optimizations to locate the local energy minima for all proposed intermediates (e.g., *HCOO, *COOH, *CO) along the reaction pathway [10].

Transition State Search: Employ specialized methods to locate the first-order saddle points between intermediates.

- Common Methods: The Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method and its dimer or climbing-image variants are widely used to approximate the reaction path and locate transition states [2].

- Verification: A true transition state must have exactly one imaginary vibrational frequency (confirmed by frequency analysis), and the atomic motion along this imaginary mode must correspond to the bond-breaking/forming process of the elementary step.

Reaction Pathway Verification: Perform Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculations from the optimized transition state geometry to confirm it correctly connects to the intended reactant and product intermediates [12].

Protocol 3: Energy Calculation and Pathway Analysis

Objective: To calculate accurate reaction energies and activation barriers, and to determine the dominant reaction pathway.

Single-Point Energy Calculations: For all optimized intermediates and transition states, perform a more accurate single-point energy calculation using a higher-level basis set or functional, if necessary.

Energy Profile Construction: Calculate the relative energy of each intermediate and transition state with respect to a chosen reference (e.g., clean catalyst and free reactants). Plot the reaction energy profile.

Rate-Determining Step Identification: Identify the elementary step with the highest activation energy barrier; this is the RDS [10].

Electronic Structure Analysis: To gain deeper insight into the mechanism, analyze the electronic structure.

- Perform Bader charge analysis or use Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis to understand charge transfer during adsorption and reaction [11].

- Calculate the d-band center for transition metal-based catalysts, a known descriptor for adsorption strength and catalytic activity [6] [11].

- Analyze the Projected Density of States (PDOS) to identify orbital interactions between the catalyst and adsorbates [11].

Advanced and High-Throughput Screening

Objective: To efficiently explore vast chemical spaces for novel catalyst materials.

Automated Pathway Exploration: Tools like ARplorer can be employed, which integrate quantum mechanics with rule-based methods and Large Language Model (LLM)-assisted chemical logic to automate the exploration of complex Potential Energy Surfaces (PES) for multi-step reactions [12].

Machine Learning Integration: Train machine learning models, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), on DFT-calculated descriptors (e.g., d-band features, adsorption energies) to rapidly predict catalytic activity (e.g., limiting potential) for thousands of candidate materials, significantly reducing computational cost [11].

Application Example: CO₂ Hydrogenation to Methanol on Cu-Based Catalysts

The following table summarizes the DFT-calculated reaction pathways and energetics for CO₂ hydrogenation on three different copper-based catalysts, demonstrating how the support material dictates the mechanism [10].

Table 1: Dominant Reaction Pathways and Energetics for CO₂ Hydrogenation on Cu-Based Catalysts [10]

| Catalyst | Dominant Pathway | Rate-Determining Step (RDS) | Activation Energy of RDS (eV) | Key Intermediate (Adsorption Energy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu/CeO₂ | HCOO (Formate) | HCOO* + H* → HCOOH* | 0.615 | HCOO* |

| Cu/Al₂O₃ | COOH (Carboxyl) | COH* + H* → HCOH* | 0.887 | COOH* |

| Cu/MgO | RWGS + CO-Hydrogenation | CO₂* → CO* + O* | 0.815 | H₂COOH* (-1.875 eV) |

This data illustrates the profound metal-support interaction, where the oxide support alters the electronic structure of the Cu active sites, steering the reaction through different mechanisms and leading to distinct activity descriptors [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Descriptors for Probing Reaction Pathways

| Item / Descriptor | Function / Significance | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Software (e.g., VASP, Gaussian, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs the core DFT calculations, including geometry optimization, transition state search, and electronic structure analysis. | Selection depends on system (periodic vs. molecular) and computational resources. |

| Catalyst Model (Slab, Cluster, SAC) | A physically realistic representation of the catalytic active site. | Accuracy of the entire study hinges on a representative model [2]. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional (e.g., PBE, RPBE, B3LYP) | Approximates the quantum mechanical exchange and correlation energy in DFT. | The choice of functional is critical and can significantly impact results like adsorption energies and barriers [2]. |

| d-Band Center (εd) | A descriptor for the adsorption strength of intermediates on transition metal surfaces. | A higher d-band center relative to the Fermi level typically correlates with stronger adsorbate binding [11]. |

| Activation Energy (Eₐ) | The energy barrier of an elementary step; the highest Eₐ defines the Rate-Determining Step. | Directly determines the reaction kinetics; used in microkinetic modeling [10]. |

| Adsorption Energy (ΔEₐds) | The strength with which a molecule binds to the catalyst surface. | A key descriptor in catalyst screening; often follows Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationships [2]. |

| Projected Density of States (PDOS) | Reveals the electronic orbital contributions of the catalyst and adsorbates. | Used to identify orbital hybridization and the nature of the catalyst-adsorbate bond [11]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for probing reaction pathways, from initial model setup to final analysis, incorporating both conventional and advanced machine-learning-assisted approaches.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Probing Reaction Pathways

The mechanistic landscape of a reaction like CO₂ hydrogenation can involve multiple competing pathways, as shown below.

Diagram 2: Competing Pathways in CO2 Hydrogenation

The rational design of catalysts requires a deep understanding of how electronic structure governs catalytic activity and selectivity. Within Density Functional Theory (DFT) for catalyst design and analysis, two complementary frameworks are paramount: d-band theory and Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) theory. d-band theory has established itself as a powerful model for predicting adsorption properties and reactivity trends on transition metal surfaces by focusing on the electronic states of the catalyst, particularly the energy and occupancy of the d-band center [13]. Simultaneously, FMO theory, a cornerstone of molecular reactivity, is experiencing a renaissance in heterogeneous catalysis, providing a unified model to describe both activity and stability of catalytic sites by examining the interactions between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the catalyst and reactants [14].

These theories provide the fundamental electronic principles that underpin catalyst performance. For instance, in single-atom catalysts (SACs), the frontier orbital interactions between the metal atom and the support directly determine both the stability of the anchored metal atom and its ability to interact with reactants [14]. This article details the practical application of these theories, providing protocols for computational analysis and experimental validation to guide researcher in catalyst development.

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Protocols

d-Band Theory: Core Principles and Workflow

d-Band theory posits that the reactivity of transition metal surfaces is dominated by the energy and shape of the d-band density of states. The primary descriptor is the d-band center (εd), which is the first moment of the d-band projected density of states (PDOS) relative to the Fermi level. A higher-lying d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) correlates with stronger adsorbate binding due to enhanced coupling between adsorbate states and metal d-states, following the Newns-Anderson chemisorption model.

Table 1: Key Descriptors in d-Band Theory Analysis

| Descriptor | Mathematical Definition | Chemical Interpretation | Common Calculation Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center (εd) | ( \epsilond = \frac{\int{-\infty}^{EF} E \cdot nd(E) dE}{\int{-\infty}^{EF} n_d(E) dE} ) | Average energy of d-states; predictor of adsorption strength. | Projected DOS (PDOS) calculation from DFT. | |||

| d-Band Width (Wd) | Second moment of the d-band PDOS. | Measure of covalent interactions between metal atoms. | PDOS analysis. | |||

| Projected Density of States (PDOS) | ( nd(E) = \sumi | \langle \psi_i | \phi_d \rangle | ^2 \delta(E - E_i) ) | Decomposition of electronic states into angular momentum components (s, p, d). | DFT calculation with plane-wave or atomic basis sets. |

The standard protocol for d-band analysis is as follows:

Protocol 1: Calculating the d-Band Center

- Structure Optimization: Relax the catalyst surface (e.g., a slab model) and any adsorbates until the residual forces on atoms are below 0.01 eV/Å.

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure to obtain the converged electron density. Use a finer k-point grid (e.g., 4x4x1 for surfaces) and a plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV or higher.

- Density of States (DOS) Calculation: Run a non-self-consistent calculation using the converged charge density from step 2. A higher k-point density is recommended for accurate DOS sampling.

- Projected DOS (PDOS) Analysis: Project the total DOS onto the d-orbitals of the relevant metal atoms (e.g., surface atoms or nanoparticles).

- d-Band Center Calculation: Calculate the first moment of the d-band PDOS from the Fermi level downwards (typically -10 eV to EF). This can be automated using scripting tools in materials science suites (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) or post-processing codes like p4vasp or VASPKIT.

Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory for Heterogeneous Systems

While d-band theory is powerful, FMO theory offers a complementary, molecule-like perspective for complex systems, including single-atom catalysts and nanoparticles. The core principle is that the interaction between the HOMO and LUMO of the catalyst and adsorbate dictates the reaction pathway. A recent groundbreaking study has successfully applied FMO theory to design single-atom catalysts, demonstrating that the energy gap between the support's LUMO and the metal atom's HOMO governs stability, while the LUMO of the anchored metal atom governs adsorbate interaction and activity [14].

Protocol 2: Frontier Orbital Analysis for Single-Atom Catalysts

- Cluster Model Construction: Create a cluster model of the support (e.g., a nanoscale metal oxide particle like ZnO or CoOx) with the single metal atom (e.g., Pd) anchored at the intended site.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the cluster model using DFT with implicit solvation models if needed for electrochemical systems [15].

- Orbital Energy Calculation: Perform an electronic structure calculation to compute the energies of the HOMO and LUMO. For periodic systems, the HOMO and LUMO correspond to the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM), which can be experimentally probed using ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and Mott-Schottky plots [14].

- Descriptor Extraction: Calculate the key FMO descriptors:

- HOMO-LUMO Gap of the support: Related to stability and tunability.

- Energy difference between support LUMO and metal HOMO (ΔE₁): A smaller ΔE₁ promotes stronger orbital hybridization for enhanced stability.

- Energy of the metal atom's LUMO (E₂): A higher-lying LUMO enhances back-donation to adsorbates, boosting activity for reactions like hydrogenation.

The logical workflow for FMO-guided catalyst design is summarized in the diagram below.

Integrated Computational Workflow for Catalyst Screening

Combining d-band and FMO analyses with active learning creates a powerful, high-throughput screening pipeline. This integrated approach was successfully used to discover Cu/Pd and Cu/Ag catalysts for selective acetate production, achieving Faradaic efficiencies of 50% and 47%, vastly superior to pure Cu (21%) [15].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Computational Catalyst Screening

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Catalyst Design | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Grand-Canonical DFT (GC-DFT) | Models electrified interfaces under constant potential, crucial for electrochemical reactions. | Calculating potential-dependent reaction barriers for CO electroreduction [15]. |

| Microkinetic Modeling (MKM) | Translates DFT energies into predicted reaction rates and selectivity under operational conditions. | Identifying CH* binding energy as key descriptor for acetate selectivity [15]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP) | Serves as a surrogate for DFT, enabling rapid evaluation of energies and forces for large systems or long timescales. | Accelerating structure search and reaction mechanism analysis [16]. |

| Active Learning Algorithms | Intelligently selects the most informative candidates for DFT calculation, optimizing the discovery process. | Guiding the search for optimal Cu/Pd and Cu/Ag ratios [15]. |

| Generative Models (e.g., Diffusion, Transformers) | Inverse design of catalyst structures with target properties by learning from large datasets. | Generating novel surface structures and alloy compositions for CO2 reduction [17]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these components are integrated into a cohesive catalyst design pipeline.

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Computational predictions must be rigorously validated experimentally. Key techniques include operando spectroscopy to monitor electronic states and kinetic measurements to assess activity.

Protocol 3: Operando XPS for Validating Electronic Structure

Objective: To correlate the electronic state of a catalyst under working conditions with computational predictions and measured activity [13].

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize the predicted catalyst (e.g., Pd₁/ZnO SAC). Confirm atomic dispersion using aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM.

- Operando AP-XPS Setup: Load the catalyst into an Ambient Pressure XPS system. Introduce reaction gases (e.g., 0.1 mbar CO + 0.3 mbar H₂O for WGS reaction).

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire survey and high-resolution spectra (e.g., Pt 4f, Ce 3d, or Pd 3d) at increasing temperatures (e.g., from 100°C to 300°C) and during cooling.

- Simultaneously monitor reaction products (e.g., H₂) using a mass spectrometer.

- Data Analysis:

- Deconvolve core-level spectra (e.g., Pt 4f) into components representing different sites: bulk/terrace atoms, low-coordinated atoms, and atomically dispersed ions [13].

- Track the evolution of these species with temperature and correlate their concentration with the onset of catalytic activity.

Case Study: Quantifying Electronic vs. Geometric Effects in Pt/CeO₂ A combined operando XPS and STEM study on Pt/CeO₂ for the water-gas shift reaction revealed that the intrinsic activity of low-coordinated corner Pt atoms on ~1-1.5 nm nanoparticles is three orders of magnitude higher than other sites. This was attributed to an electronic structure effect, specifically a shift in the Pt valence states, rather than a purely geometric effect [13]. This finding underscores the critical importance of electronic structure analysis for explaining dramatic activity enhancements.

Protocol 4: Zero-Gap Electrolyzer Validation for Electrocatalysts

Objective: To test computationally predicted catalysts in realistic electrochemical environments, such as for CO₂/CO electroreduction [15].

- Catalyst Ink Preparation: Disperse the catalyst powder (e.g., predicted Cu/Pd (2:1)) in a mixture of solvent (e.g., isopropanol) and Nafion ionomer, then sonicate.

- Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) Fabrication: Spray the catalyst ink onto a gas diffusion layer (GDL) to form the cathode. Assemble it with an anion exchange membrane and an anode.

- Electrochemical Testing: Place the MEA in a zero-gap electrolyzer cell. Feed CO gas to the cathode and an electrolyte (e.g., KOH) to the anode.

- Product Analysis:

- Quantify gaseous products (e.g., C₂H₄, CO) using online gas chromatography (GC).

- Quantify liquid products (e.g., acetate, ethanol) using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

- Performance Metric Calculation: Calculate the Faradaic efficiency (FE) for each product, which represents the selectivity of the catalyst. The experimental confirmation of Cu/Pd (2:1) achieving 50% FE for acetate validated the AI-driven multi-scale simulation framework [15].

The electrochemical transformation of industrial by-products such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and carbon dioxide (CO2) into value-added chemicals represents a cornerstone of sustainable chemical production. This application note details the integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) with advanced experimental methodologies to elucidate reaction mechanisms and guide the rational design of electrocatalysts for these critical reactions. The focus is placed on the electroreduction of NOx to ammonia (NH3) and the electrochemical conversion of CO2 to carbon monoxide (CO) and other C1 products, framing these processes within the context of a broader thesis on DFT for catalyst design and analysis. We provide a comprehensive framework that bridges theoretical predictions, utilizing descriptors such as adsorption energies and d-band centers, with practical experimental validation and protocol implementation [18] [2] [19].

Mechanistic Insights from Computational Studies

NOx Electroreduction (NOxRR) to Ammonia

The electrocatalytic reduction of NOx (including nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), and nitric oxide (NO)) to ammonia involves complex reaction networks with multiple possible intermediates and competing side reactions, notably the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [18].

- Key Intermediates and Descriptors: DFT studies have identified that the adsorption strengths of key nitrogenous intermediates, such as *NO and *NH2, are crucial activity descriptors. The efficiency of the overall process is determined by the catalyst's ability to facilitate the proton-electron transfer steps while suppressing the HER [18] [19].

- The Role of Active Hydrogen: The active hydrogen species (H) generated from water dissociation is a critical participant. Its optimal binding energy is essential for driving the hydrogenation steps in both NOxRR and CO2 reduction reactions. Excess H, however, leads to undesirable HER. Catalyst design strategies, therefore, often aim to control the availability and binding strength of H* [19].

Table 1: Key DFT-Calculated Descriptors for NOxRR and CO2RR Catalysts

| Reaction | Catalyst Material | Key Descriptor | Descriptor Function | Optimal Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx to NH3 | Transition Metal Catalysts | *NO & *NH2 Adsorption Energy | Determines activity & selectivity for NH3 production [18] | Moderate binding strength |

| CO2 to CO | Fe-N-C Single-Atom Catalysts | *COOH & *CO Adsorption Energy | Determines activity & selectivity for CO production [20] [21] | Weak *CO binding to avoid poisoning |

| CO2 to CO | Fe-Dual-Atom Catalysts | H Adsorption on Graphitic Edge | Suppresses competing HER, boosting CO selectivity [20] | Strong H binding on non-metal sites |

| HER | Multimetallic Alloys | H Adsorption Energy (ΔG_H*) | Primary descriptor for HER activity [22] | ΔG_H* ≈ 0 |

CO2 Electroreduction (CO2RR) to C1 Products

The selective reduction of CO2 to CO and other products is a widely studied pathway. For single-atom catalysts like M-N-C (metal-nitrogen-carbon), the local coordination environment profoundly influences the reaction mechanism and selectivity [20] [21].

- Reaction Pathways and Selectivity: On Fe-N-C sites, the CO2RR to CO typically proceeds through the formation of a COOH intermediate, followed by the desorption of *CO. The selectivity between CO production and the competing HER is directly governed by the relative binding strengths of *CO and *H on the active site. DFT and microkinetic modeling have shown that for Fe dual-atom catalysts (Fe-DACs) at graphitic edges, the edge sites themselves can bind H atoms more strongly than the Fe site, effectively sequestering H and breaking the linear scaling relationship between *CO and *H adsorption. This shifts the limiting potential for CO2RR below that of HER, favoring high CO selectivity [20].

- Effect of Coordination Environment: The number of coordinating nitrogen atoms and the identity of the metal center (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) in M-N-C catalysts significantly modulate the electronic structure (e.g., d-band center) of the active site. This modulation affects the binding strength of intermediates and the magnitude of the potential-limiting step, thereby influencing the overall activity and product selectivity [21].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Testing of a Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) Electrolyzer for NOxRR

Principle: This protocol describes the assembly and evaluation of a full-runner MEA electrolyzer (MEA-FR) designed to overcome mass transport limitations at industrial current densities for NOx− reduction to NH3 [23].

Materials:

- Catalyst-Inked Diffusion Layer: Cathode catalyst (e.g., nanostructured porous electrode) dispersed in ink and deposited on a gas diffusion layer (GDL).

- Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) or Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM).

- Anode Catalyst: Iridium oxide (IrO2) or similar for oxygen evolution reaction (OER).

- Titanium or Graphite Bipolar Plates: Featuring a full-runner flow field design (a streamlined slot) instead of a serpentine pattern.

- Electrolyte: NOx−-containing aqueous solution (e.g., KNO3 or NaNO3).

- Test Station: Potentiostat/Galvanostat, electrolyte pumps, gas collection system, and product quantification setup (e.g., ion chromatography for NH3 and NMR for N2H4).

Procedure:

- MEA Assembly: Sandwhich the PEM/AEM between the catalyst-coated cathode GDL and the anode. Assemble the cell by placing the MEA between two bipolar plates with gaskets to prevent leaks.

- System Setup: Connect the electrolyzer to the test station. Ensure all fluidic and electrical connections are secure.

- Electrolysis Operation:

- Pump the catholyte (NOx− solution) through the full-runner flow field, forcing convective flow through the porous cathode.

- Circulate an anolyte (e.g., dilute acid or alkaline solution) on the anode side.

- Apply a constant current density (e.g., 200-500 mA cm⁻²) using a galvanostat.

- Maintain a constant electrolyte flow rate and temperature.

- Product Analysis:

- Liquid Products: Collect aliquots of the catholyte at regular intervals. Quantify NH3 concentration using the indophenol blue method or ion chromatography. Quantify any by-product N2H4 using Watt and Chrisp method or NMR.

- Gas Products: Use online gas chromatography (GC) to analyze the cathode effluent for H2 and other gases.

- Performance Calculation:

- Faradaic Efficiency (FE): Calculate for NH3 using the formula: ( FE{NH3} (\%) = \frac{z \times F \times n{NH3}}{Q} \times 100 ), where ( z ) is the number of electrons transferred per NH3 molecule (8 for NO3− to NH3), ( F ) is the Faraday constant, ( n{NH3} ) is the moles of NH3 produced, and ( Q ) is the total charge passed.

- Report cell voltage and stability over time (e.g., >200 hours) [23].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking CO2 Reduction Performance for Industrial Implementation

Principle: This protocol outlines key performance metrics and procedures for evaluating CO2RR catalysts and systems under conditions relevant to industrial application [24].

Materials:

- Gas Diffusion Electrode (GDE): Integrated with the catalyst layer.

- Flow Cell or MEA Electrolyzer.

- Bipolar Membrane (BPM) or Cation Exchange Membrane.

- CO2 Source: High-purity CO2 or simulated industrial flue gas.

- Electrolyte: e.g., KHCO3 solution.

- Test Station: Potentiostat, mass flow controllers, gas chromatograph (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Procedure:

- Cell Assembly: Integrate the GDE-based cathode, membrane, and anode into a flow cell configuration to enable high current density operation.

- Operational Conditions:

- Apply current densities of >200 mA cm⁻².

- Maintain cell temperature between 60-90 °C for stress-testing.

- Use a stoichiometric excess (λ value) of CO2 to ensure sufficient reactant supply.

- Product Analysis and Key Metrics:

- Gas Products: Use online GC with a TCD and FID to quantify and determine Faradaic Efficiency for CO, C2H4, CH4, etc.

- Liquid Products: Use HPLC or NMR to quantify and determine Faradaic Efficiency for formate, alcohols, etc.

- Single-Pass Conversion (SPC): Calculate the percentage of CO2 converted from the inlet stream in a single pass. For C1 products in BPM-based systems, target SPC >70% [24].

- Stability Testing: Operate the system for extended periods (>1000 hours) and report voltage decay rates (<10 µV/h) and changes in Faradaic Efficiency (ΔFE/Δt < 0.1% per 1000 h).

- Full Cell Voltage: Report the total cell voltage at the target current density, with values <3.0 V at 300 mA cm⁻² being a suggested benchmark [24].

- Reporting: Document all critical parameters, including electrode structure, GDE composition, flow rates, and outlet stream composition, to ensure reproducibility [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and computational tools essential for research in NOxRR and CO2RR, as derived from the cited protocols and studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| M-N-C Single-Atom Catalysts | Active sites for CO2RR to CO; study of coordination environment effects [20] [21] | Fe-, Co-, Ni-, Cu- supported on N-doped graphene; tunable coordination number. |

| Multimetallic Alloy Nanoparticles | Exploration of HER and other electrocatalytic activities with unique binding sites [22] | Pt-, Ru-, Cu-, Ni-, Fe-based alloys; vast compositional space for screening. |

| Gas Diffusion Electrode (GDE) | Enables high current density operation by facilitating CO2 mass transport [24] | Porous carbon-based structure; often coated with catalyst layer. |

| Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) | Zero-gap configuration for efficient electrolysis (NOxRR, CO2RR) [23] | Integrates electrodes with a PEM, AEM, or BPM. |

| Full-Runner Flow Field | Electrolyzer component for enhanced mass transport and bubble removal [23] | Replaces serpentine channels with a slot; forces convection through electrode. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Modeling reaction mechanisms, adsorption energies, and predicting catalyst activity [18] [2] | Uses software like VASP; calculates descriptors (d-band center, ΔG_ads). |

| Active Learning Framework | Accelerates the discovery of optimal multimetallic catalyst compositions [22] | Combines machine learning (Gaussian Process Regressor) with DFT. |

Workflow and System Visualization

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Catalyst Design

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic cycle between theoretical computation and experimental validation in modern electrocatalyst development.

Integrated Catalyst Design Workflow: This flowchart outlines the iterative process of using DFT calculations to derive activity descriptors and screen potential catalysts, often accelerated by machine learning. Promising candidates are synthesized and experimentally validated, with the resulting performance data feeding back to refine computational models and generate new mechanistic insights [18] [2] [22].

Mass Transport in Electrolyzer Flow Field Designs

The diagram below contrasts mass transport mechanisms in different electrolyzer designs, a critical factor in achieving industrial current densities.

Electrolyzer Flow Field Comparison: This diagram compares the serpentine runner (MEA-SR) and full-runner (MEA-FR) electrolyzer designs. The MEA-SR's flow-by pattern leads to reactant concentration gradients and poor bubble management. In contrast, the MEA-FR's flow-through pattern ensures uniform reactant concentration and generates high shear forces for efficient bubble removal, directly enabling high Faradaic efficiency and stability at industrial current densities [23].

The Role of DFT in Replacing Trial-and-Error Approaches

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has fundamentally transformed the paradigm of catalyst design and analysis, shifting the research methodology from traditional trial-and-error experimental approaches to precise, prediction-driven computational screening. By enabling researchers to determine molecular structures, reaction energies, barrier heights, and spectroscopic properties at the quantum level, DFT provides profound atomic-level insights into catalytic mechanisms and structure-property relationships. This application note details how DFT methodologies, particularly when integrated with machine learning (ML) and high-throughput screening, are revolutionizing the development of catalysts for sustainable energy applications. We present structured protocols, quantitative data comparisons, and visual workflows to guide researchers in implementing DFT-based design strategies for various catalytic systems, including carbon-supported single-atom catalysts (CS-SACs) and electrocatalysts for energy conversion processes.

The traditional approach to catalyst development has relied heavily on experimental synthesis and testing—an often time-consuming and resource-intensive process. Density Functional Theory addresses this challenge by providing a computational framework to explore the atomic and electronic structures of materials, thereby predicting catalytic activity and stability before synthesis is ever attempted. For energy storage and conversion technologies, such as fuel cells and electrolyzers, DFT calculations elucidate critical reaction mechanisms, including the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), and CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR) [25] [6].

The predictive power of DFT is particularly valuable for designing single-atom catalysts (SACs), which feature isolated metal atoms on solid supports. These catalysts maximize atomic efficiency and exhibit unique electronic properties. For carbon-supported SACs (CS-SACs), DFT studies have been instrumental in guiding atomic-level regulation strategies such as coordination structure control, nonmetaxial elemental doping, and polymetallic active site construction to optimize performance [25]. This targeted approach, guided by computational insights, significantly accelerates the discovery and optimization of next-generation catalytic materials.

Key DFT Application Protocols in Catalyst Design

Best-Practice DFT Calculation Workflow

Adopting standardized protocols is essential for obtaining accurate, reproducible results in computational catalyst design. The following workflow provides a robust framework for typical DFT studies [26] [27]:

- System Preparation: Define the atomic structure of the catalytic system, including the active site and support material. For CS-SACs, this typically involves modeling graphene or other carbon allotropes with single metal atoms anchored at defect sites.

- Functional and Basis Set Selection: Choose an appropriate exchange-correlation functional and atomic orbital basis set based on the system and properties of interest (refer to Table 1 for guidance).

- Convergence Testing: Perform systematic tests to determine the necessary parameters for energy accuracy, including the plane-wave cutoff energy and k-point sampling for periodic systems. Convergence is typically achieved when total energy changes are less than 0.01 eV [28].

- Geometry Optimization: Relax the atomic structure until the forces on all atoms are minimized (typically below 0.01 eV/Å).

- Property Calculation: Compute the target electronic, energetic, or mechanical properties, such as adsorption energies, density of states, or elastic constants.

- Validation: Where possible, compare computational results with available experimental data to validate the methodological choices.

Protocol for Electrocatalytic Reaction Pathway Analysis

A common application of DFT in catalysis is the mechanistic study of electrocatalytic reactions. The following protocol outlines the key steps [6]:

- Model the Electrochemical Interface: Construct a slab model of the catalyst surface in contact with an implicit or explicit solvent environment.

- Identify Possible Reaction Intermediates: Use chemical intuition and literature to propose stable intermediate species adsorbed on the catalyst surface.

- Calculate Free Energies: Optimize the geometry of each intermediate and compute its electronic energy. Apply thermodynamic corrections to obtain Gibbs free energies at the desired temperature and potential.

- Construct the Free Energy Diagram: Plot the free energy of the system as a function of the reaction coordinate. The potential-determining step is identified as the step with the largest positive free energy change.

- Account for Electrode Potential: Use computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) or Grand-Canonical DFT approaches to model the effect of applied potential on the reaction energetics.

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for a DFT-based catalyst screening study.

Advanced Protocol: Integrating DFT with Machine Learning

The combination of DFT and machine learning (ML) creates a powerful paradigm for accelerated materials discovery [6] [29].

- DFT Data Generation: Use high-throughput DFT calculations to generate a diverse and reliable dataset of catalytic properties (e.g., adsorption energies, formation energies) for a training set of materials.

- Feature Selection: Identify meaningful descriptors (e.g., d-band center, coordination number, electronegativity, atomic radius) that correlate with the target catalytic properties.

- Model Training: Train ML models (e.g., neural networks, kernel ridge regression) on the DFT dataset to learn the mapping between material descriptors and target properties.

- Predictive Screening: Use the trained ML model to rapidly screen vast chemical spaces (thousands to millions of candidates) and identify promising catalyst candidates.

- DFT Validation: Perform rigorous DFT calculations on the ML-predicted leads to validate their predicted performance before experimental synthesis.

This multi-level approach achieves an optimal balance between computational accuracy and efficiency [26].

Quantitative Comparison of DFT Methods and Performance

The choice of computational methodology significantly impacts the accuracy and predictive power of DFT studies. The tables below summarize key considerations and representative results.

Table 1: Recommended DFT Functional and Basis Set Selection Matrix for Catalysis Research

| Computational Task | Recommended Functional(s) | Recommended Basis Set(s) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Optimization | PBE, RPBE, BEEF-vdW [6] [28] | Plane-wave (cutoff 60 Ry+) [28], def2-SVP [26] | PBE+U improves structural properties for systems with localized d-electrons [28]. |

| Reaction Energy/Barrier | B3LYP, M06-2X, ωB97X-D [26] | def2-TZVP, def2-QZVP [26] | Hybrid functionals often improve accuracy but increase computational cost. |

| Electronic Properties (Band Gap) | HSE06, PBE0, GW [28] | Plane-wave, localized basis sets | Standard PBE/LDA underestimates band gaps; hybrid functionals or advanced methods are required. |

| Mechanical/Thermal Properties | PBE+U, LDA [28] | Plane-wave (high cutoff) | PBE+U provided results for CdS/CdSe that best aligned with experimental data [28]. |

Table 2: Representative DFT-Predicted Properties for Catalyst Materials and Design Strategies

| Material System | DFT-Investigated Property | Key Finding/Performance | Reference Functional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc-blende CdS | Bulk Modulus (B) | 71.75 GPa (PBE+U) - Higher stiffness than CdSe [28] | PBE+U |

| Zinc-blende CdSe | Bulk Modulus (B) | 53.85 GPa (PBE+U) - Softer lattice [28] | PBE+U |

| CS-SACs (General) | Coordination Environment | Coordination number, non-metallic doping, and axial ligands tune activity [25] | Various |

| CS-SACs for Li-S batteries | Adsorption Energy of LiPS | Regulating coordination structure mitigates polysulfide shuttling [25] | Various |

| CdS / CdSe | Zero Thermal Expansion Point | 113.92 K (CdS) and 61.50 K (CdSe) predicted via QHA [28] | PBE+U |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful DFT-based catalyst design relies on a suite of software, computational tools, and conceptual "reagents."

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DFT-Based Catalyst Design

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Catalyst Design |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO [28] | Software Package | Plane-wave pseudopotential DFT code for periodic solid-state systems. |

| Hubbard U Correction [28] | Computational Method | Corrects for self-interaction error in systems with localized d/f electrons, improving band gaps. |

| Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) [28] | Pseudopotential | Treats core-valence electron interactions efficiently, improving computational accuracy. |

| van der Waals (vdW) Functionals | Computational Method | Accounts for dispersion forces, critical for physisorption and layered materials. |

| Catalytic Descriptor (e.g., d-band center) | Conceptual Tool | Electronic structure proxy for predicting adsorption strength and catalytic activity. |

| Machine Learning Potentials [6] [29] | Software/Method | Accelerates screening and dynamics simulations by learning from DFT data. |

Integrated Workflow: From DFT Prediction to Catalyst Design

The most significant advantage of DFT lies in its integration into a holistic design loop, which effectively replaces linear trial-and-error cycles. This integration is exemplified in the synergistic DFT-ML workflow, which dramatically accelerates the discovery process for materials such as carbon-supported single-atom catalysts [6] [29]. In this paradigm, DFT provides the fundamental, high-quality data on energies and electronic structures, while ML models rapidly extrapolate these relationships across vast compositional and structural spaces. This allows researchers to pre-screen thousands of candidate materials in silico before committing to synthesis.

The following diagram visualizes this integrated, cyclical approach to rational catalyst design.

This workflow has been successfully applied to optimize CS-SACs for reactions like the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and CO₂ reduction reaction (CO₂RR), where DFT simulations guide the atomic-level engineering of the metal center's coordination environment (e.g., M-N-C moieties) to enhance activity and selectivity [25]. Furthermore, for compound semiconductors like CdS and CdSe, DFT-guided design predicts not only electronic structure but also crucial mechanical and thermal properties (e.g., elastic constants, thermal expansion), ensuring functional stability under operating conditions [28].

Density Functional Theory has unequivocally established itself as a cornerstone technology in modern catalyst research, enabling a rational, principles-driven design framework that systematically displaces inefficient trial-and-error methodologies. By providing deep insights into reaction mechanisms, electronic structure, and structure-property relationships, DFT guides the atomic-level engineering of advanced materials such as carbon-supported single-atom catalysts and semiconductor compounds. The ongoing integration of DFT with machine learning and high-throughput computational screening is poised to further accelerate the discovery timeline, creating a powerful engine for innovation in sustainable energy technologies. Adherence to best-practice protocols for functional selection, convergence testing, and workflow design, as outlined in this application note, is critical for leveraging the full potential of DFT in the quest for next-generation catalysts.

Computational Workflows and Emerging AI Synergies in Catalyst Design

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the fundamental computational framework for modern catalyst design and analysis, enabling researchers to predict atomic-scale properties that govern catalytic performance. The accuracy of these predictions hinges critically on the choice of exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which approximates the complex quantum mechanical interactions between electrons. The scientific community has progressively developed increasingly sophisticated XC functionals, often conceptualized through "Jacob's Ladder," which ascends from simpler to more theoretically complete approximations. For researchers in catalysis, navigating this landscape—from Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGAs) to hybrid functionals like HSE06 and beyond—is essential for obtaining reliable data on catalytic surfaces, reaction pathways, and intermediate adsorption energies.

The limitations of standard GGA functionals, such as Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE), are particularly pronounced in catalytic systems involving transition metals, rare-earth elements, and oxides, where strongly correlated electrons and localized d- and f- orbitals play a decisive role in reactivity. These functionals suffer from self-interaction error (SIE) and systematically underestimate electronic band gaps, leading to inaccurate predictions of electronic structure, surface reactivity, and phase stability [30] [31]. Hybrid functionals, which incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, offer a path to greater accuracy, making them indispensable for predictive catalyst design. This application note provides a structured comparison of these methodologies and detailed protocols for their application in catalytic materials research.

Functional Performance: A Quantitative Comparison

The selection of an appropriate XC functional requires a clear understanding of its performance characteristics for different material properties. The table below summarizes key benchmarks for functionals relevant to catalytic materials.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Common DFT Functionals for Catalytic Materials

| Functional | Rung on Jacob's Ladder | Typical MAE in Formation Energy (eV/atom) | Typical MAE in Band Gap (eV) | Computational Cost (Relative to GGA) | Recommended for Catalytic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | ~0.1 - 0.2 | ~1.3 - 1.5 [30] | 1x | Preliminary structural screening, metals |

| PBEsol | GGA | Similar to PBE [30] | Similar to PBE [30] | ~1x | Accurate lattice constants of solids [30] |

| SCAN/r2SCAN | meta-GGA | Lower than GGA [31] | ~0.6 - 0.8 [31] | ~2-5x | Balanced accuracy/cost for REOs & oxides [31] |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | ~0.15 vs. PBEsol [30] | ~0.6 vs. experiment [30] | ~10-50x | Band gaps, electronic structure, defect chemistry [30] [32] |

| HSE06+U | Hybrid+U | System-dependent | System-dependent | >HSE06 | Systems with highly localized electrons (e.g., REO 4f states) [31] |

The quantitative data reveals a clear trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. For instance, while HSE06 reduces the mean absolute error (MAE) in band gaps by over 50% compared to PBE (from 1.35 eV to 0.62 eV for a set of 121 binary materials), it requires an order of magnitude more computational resources [30]. This makes HSE06 particularly valuable for properties sensitive to electronic structure, such as photocatalytic activity or the energy levels of active sites. The r2SCAN functional emerges as a promising compromise, offering meta-GGA accuracy for structural and energetic properties at a fraction of the cost of hybrid calculations [31].

Table 2: Functional-Specific Recommendations for Catalyst Systems

| Catalyst Type | Key Challenges | Recommended Functional(s) | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Oxides | Accurate band gaps, localized d-electrons, magnetic ordering | HSE06, SCAN/r2SCAN | HSE06 is superior for electronic properties; meta-GGAs offer good cost-accuracy balance [30] [31]. |

| Rare-Earth Oxides (REOs) | Strong correlation in 4f electrons, spin-orbit coupling | HSE06, r2SCAN+U, r2SCAN+U+SOC | +U and Spin-Orbit Coupling (SOC) corrections are often critical for qualitative accuracy [31]. |

| Carbon-Based (e.g., g-C3N4) | Defect engineering, adsorption strength, charge transfer | HSE06 (for band structure), PBE/HSE06 (for adsorption) | HSE06 validates band structure; GGA can screen defects, but adsorption may need hybrid verification [32]. |

| Binuclear TM Complexes | Magnetic exchange coupling | Range-separated hybrids (e.g., HSE06) | Functionals with moderate short-range HF exchange perform well for J-coupling constants [33]. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Workflow for Oxide Catalyst Stability Screening

This protocol, adapted from large-scale database construction efforts, is designed for assessing the thermodynamic and electrochemical stability of oxide catalysts [30].

Initial Structure Curation:

- Source: Query candidate crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Filtering: For compositions with multiple entries (polymorphs), select the structure with the lowest energy per atom according to a reference database (e.g., Materials Project). If no reference data exists, select the ICSD entry with the smallest unit cell.

Geometry Optimization:

- Software: All-electron code FHI-aims (can be adapted to VASP with PAW pseudopotentials).

- Functional: Use the PBEsol functional.

- Basis Set: In FHI-aims, use "light" numerical atom-centered orbital (NAO) basis sets for a favorable accuracy/efficiency trade-off.

- Convergence: Set force convergence criteria to at least 10⁻³ eV/Å.

- Spin: Employ spin-polarized calculations for all structures containing transition metals (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni) or those flagged as magnetic in reference databases.

Single-Point Energy & Electronic Structure Calculation:

- Functional: Use the HSE06 hybrid functional on the PBEsol-optimized structures.

- Settings: Use the same "light" basis sets and k-point grid as the optimization step. For systems with challenging convergence (e.g., those with 3d/4f elements), a denser k-point mesh may be required.

- Outputs: Compute the total energy, electronic density of states (DOS), band structure, and Hirshfeld charges.

Data Analysis for Catalysis:

- Formation Energy: Calculate using elemental solid phases as references, except for oxygen, where the O₂ molecule is used.

- Stability Assessment: Construct convex hull phase diagrams (CPDs) from the computed formation energies. Phases on the hull are thermodynamically stable; those above it are metastable or unstable, with the decomposition energy (ΔHd) quantifying their stability.

- Electronic Properties: Analyze the DOS and band structure to determine the band gap and character (direct/indirect), which are critical for photocatalytic applications.

Protocol 2: Defect Engineering Analysis in Carbon Nitride Photocatalysts

This protocol details a combined DFT and experimental validation workflow for designing defective carbon nitride catalysts, as demonstrated in recent research [32].

Model Construction:

- Build a monolayer model of tri-s-triazine-based g-C₃N₄.

- Generate defective models by creating atomic vacancies (e.g., carbon or nitrogen vacancies) or introducing other symmetry-breaking defects.

Computational Property Prediction:

- Geometry Optimization: Perform using a GGA functional (e.g., PBE) in VASP to relax the atomic coordinates and cell parameters.

- Electronic Structure: Calculate the accurate band structure using the HSE06 hybrid functional on the optimized geometry.

- Adsorption Energy Calculation: Compute the adsorption energy (E_ads) of key reaction intermediates (e.g., O₂ for H₂O₂ production) using:

E_ads = E_(catalyst+adsorbate) - E_catalyst - E_adsorbate. The functional used (PBE or HSE06) should be consistent and chosen based on the required accuracy.

Experimental Synthesis & Validation:

- Synthesis: Synthesize the modeled defective carbon nitride (DCN) samples via thermal polycondensation of precursors (e.g., melamine, urea) with controlled process conditions to induce the desired defects.

- Characterization: Use techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) to confirm the successful introduction of defects.

- Performance Testing: Evaluate photocatalytic performance in representative reactions such as organic pollutant degradation and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) production under visible light.

Theory-Experiment Correlation:

- Compare the computationally predicted trends in band gaps, charge transfer resistance, and adsorbate binding strengths with the experimentally measured photocatalytic activity rates to validate the models.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a hybrid computational-experimental study in catalyst design, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Catalyst DFT Studies

| Item / Software | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | A widely used plane-wave DFT code with PAW pseudopotentials. | Industry standard for periodic systems; supports GGA to hybrid functionals. [31] [32] |

| FHI-aims | An all-electron DFT code with numeric atom-centered orbitals. | Provides high accuracy without pseudopotentials; efficient for hybrid functionals. [30] |

| HSE06 Functional | A range-separated hybrid functional. | Critical for accurate band gaps and electronic structure; use for final single-point calculations. [30] [32] |

| PBEsol Functional | A GGA functional optimized for solids. | Excellent for initial geometry optimization, providing accurate lattice constants. [30] |

| r2SCAN Functional | A regularized meta-GGA functional. | Modern functional offering a good balance of accuracy and cost for challenging systems. [31] |

| Hubbard U Parameter | An empirical correction for localized electrons. | Essential for treating strong correlation in transition metal and rare-earth oxide 4f electrons. [31] |

| Spin-Orbit Coupling (SOC) | A relativistic correction for heavy elements. | Necessary for quantitatively accurate electronic structure of rare-earth elements. [31] |

| Taskblaster Framework | A workflow automation tool. | Manages high-throughput calculation sequences and data curation. [30] |

Within the framework of Density Functional Theory (DFT) for catalyst design and analysis, the efficient screening of catalyst libraries is a critical step in accelerating the development of new materials for energy conversion, sustainable chemistry, and drug development. DFT calculations provide a powerful means to understand catalytic mechanisms at the electronic level, which are often difficult to probe experimentally [3]. The core of this computational screening approach relies on identifying activity descriptors—computationally accessible properties that correlate with catalytic performance—which allow researchers to predict the efficacy of new catalysts without resorting to labor-intensive synthesis and testing [3] [34]. Among these descriptors, adsorption energies of key reaction intermediates are paramount, as they often dictate the catalytic activity according to the Sabatier principle [35] [2]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for using adsorption energies and other key descriptors in the high-throughput screening of catalyst libraries, integrating computational DFT approaches with experimental validation strategies to create a robust pipeline for catalyst discovery.

Theoretical Foundation: Key Descriptors in Catalyst Screening

The Role of Adsorption Energy

The adsorption energy ((E{ad})) of a molecule to a catalyst surface is a fundamental determinant in heterogeneous catalysis, governing the formation and breaking of chemical bonds during catalytic cycles [35]. Accurate prediction of (E{ad}) enables the computational screening of large material libraries by serving as a proxy for catalytic activity. According to the Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relation, the energy barriers of chemical reactions scale approximately linearly with the adsorption energies of molecules [2]. This linear scaling allows for the prediction of reaction kinetics from thermodynamic adsorption data, forming the basis for high-throughput catalyst screening.

Established Electronic and Geometric Descriptors

Several descriptors derived from DFT calculations have been established to predict adsorption strengths and catalytic activities:

- d-Band Center: For transition metal catalysts, the d-band center model has been particularly successful in elucidating trends in adsorption at surfaces. The d-band center (( \epsilon_d )) represents the average energy of electronic d-states projected onto a surface atom, which correlates with adsorption energy trends [35] [2].

- Generalized Coordination Number (( \overline{CN} )): This geometric descriptor accounts for the local environment of surface atoms. It is defined as the sum of the coordination numbers of the nearest neighbors of a surface atom, divided by the bulk coordination number. ( \overline{CN} ) effectively describes the geometric effect of pure metals for adsorption and catalysis [35].

- Valence and Electronegativity Descriptor (( \psi )): A combined electronic descriptor has been proposed that incorporates both the valence ((Sv)) and electronegativity ((\chi)) of surface atoms: ( \psi = Sv^2 \chi^\beta ), where (\beta) is an index determined by the role of d- and s-orbitals. This descriptor shows linear relationships with adsorption energies across various adsorbates [35].

Emerging Descriptors for Complex Systems

Recent advances have identified additional descriptors crucial for specific catalytic contexts:

Full Density of States (DOS) Similarity: For bimetallic catalysts, the similarity in electronic DOS patterns between an alloy and a known reference catalyst (e.g., Pd) can serve as an effective screening descriptor. The difference between two DOS patterns can be quantified using the equation:

[ \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ \int \left[ DOS2(E) - DOS_1(E) \right]^2 g(E;\sigma) dE \right}^{1/2} ]

where (g(E;\sigma)) is a Gaussian distribution function centered at the Fermi energy [34].

- Potential of Zero Charge (PZC): In electrocatalysis, the PZC has emerged as a critical descriptor that accounts for electric double layer effects. The PZC influences how surface charge density (( \sigma )) changes with applied potential ((U)): ( \sigma = C{gap} \cdot (U - U^{PZC}) ), where (C{gap}) is the Helmholtz capacitance. This descriptor is particularly important for electrochemical CO₂ reduction, where it affects intermediate stability and product selectivity [36].

Table 1: Key Descriptors for Catalyst Screening and Their Applications

| Descriptor | Definition | Catalytic Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Energy ((E_{ad})) | Energy released when a molecule adsorbs on a surface | Universal descriptor for catalytic activity | Direct relation to Sabatier principle |

| d-Band Center (( \epsilon_d )) | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | Transition metal surface reactions | Successful trend predictions for late TMs |

| Generalized Coordination Number (( \overline{CN} )) | Weighted sum of neighbors' coordination numbers | Structure-sensitive reactions | Accounts for local geometric effects |

| DOS Similarity (( \Delta DOS )) | Quantitative comparison of electronic structures | Bimetallic catalyst discovery | Enables replacement of precious metals |

| Potential of Zero Charge (PZC) | Electrode potential where surface charge is zero | Electrocatalysis | Accounts for electric double layer effects |

Computational-Experimental Screening Protocol

The following protocol outlines an integrated workflow for screening bimetallic catalysts, adapted from a successful demonstration that discovered Pd-substituting catalysts from 4350 candidate structures [34].

Diagram 1: High-throughput screening workflow for bimetallic catalyst discovery.

Protocol Steps

Step 1: Library Definition and Thermodynamic Screening

- Objective: Identify thermodynamically stable catalyst candidates from a large initial library.

- Procedure:

- Define the compositional space (e.g., 435 binary systems from 30 transition metals at 1:1 composition).

- Generate multiple ordered phases for each composition (e.g., 10 crystal structures per system: B1, B2, B3, etc.).

- Calculate formation energy (( \Delta Ef )) for each structure using DFT.

- Apply thermodynamic stability filter (( \Delta Ef < 0.1 ) eV) to identify feasible candidates.

- Outcome: In the referenced study, this step reduced the candidate pool from 4350 to 249 structures [34].

Step 2: Electronic Structure Analysis

- Objective: Calculate electronic properties to identify promising candidates with desired catalytic features.

- Procedure:

- For thermodynamically stable candidates, calculate the projected density of states (DOS) on close-packed surfaces.

- Include both d-states and sp-states in the analysis, as sp-states can play significant roles in adsorption processes.

- Compute DOS similarity (( \Delta DOS )) to a reference catalyst (e.g., Pd(111)) using the integral difference metric.

- Select candidates with lowest ( \Delta DOS ) values (e.g., < 2.0) for experimental validation.

- Notes: The inclusion of sp-states is crucial, as they significantly contribute to adsorption interactions in certain systems, such as O₂ adsorption on Ni₅₀Pt₅₀(111) [34].

Step 3: Experimental Validation

- Objective: Synthesize and test computationally predicted candidates.

- Procedure:

- Synthesize top candidates (e.g., 8 candidates from screening).

- Evaluate catalytic performance for target reaction (e.g., H₂O₂ direct synthesis).

- Compare performance metrics to reference catalyst (e.g., Pd).

- Identify hits with comparable or superior performance to reference.

- Outcome: In the referenced study, 4 of 8 candidates showed performance comparable to Pd, with Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ exhibiting 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [34].

Advanced Descriptor Implementation

For electrochemical systems, the protocol must be modified to account for the electrochemical interface. The adsorption energy in electrocatalysis should be calculated as [36]:

[ \Deltai \Omega(U,pH) = \Deltai E(\sigma(U)) + \Delta_i E^{T,S,ZPE,\circ} + eU + 0.0592 \cdot pH ]

where ( \sigma(U) = C{gap} \cdot (U - U^{PZC}) ), and ( \Deltai E(\sigma(U)) ) is the surface-charge dependent adsorption energy from DFT.

Table 2: Adsorption Energy Components in Electrocatalysis

| Term | Description | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|

| ( \Delta_i E(\sigma(U)) ) | Surface-charge dependent adsorption energy | DFT with implicit solvation |

| ( \Delta_i E^{T,S,ZPE,\circ} ) | Zero-point energy and finite temperature correction | DFT frequency calculations |

| ( eU ) | Applied potential contribution | Computational Hydrogen Electrode (CHE) |

| ( 0.0592 \cdot pH ) | pH-dependent term | Nernstian relationship |

Case Study: Bimetallic Catalyst Discovery for H₂O₂ Synthesis

Screening Implementation

A successful implementation of the screening protocol discovered bimetallic catalysts to replace Pd in H₂O₂ direct synthesis [34]:

- Initial Library: 4350 bimetallic alloy structures (435 binary systems × 10 crystal structures)

- Stability Screening: 249 alloys passed the thermodynamic stability filter (( \Delta E_f < 0.1 ) eV)

- DOS Similarity Screening: 17 candidates with ( \Delta DOS < 2.0 ) identified

- Synthetic Feasibility Evaluation: 8 candidates selected for experimental validation

- Experimental Results: 4 candidates confirmed with catalytic performance comparable to Pd

Performance Results

Table 3: Experimentally Validated Bimetallic Catalysts for H₂O₂ Synthesis

| Catalyst | DOS Similarity (( \Delta DOS )) | Performance vs. Pd | Cost-Normalized Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | 1.72 | Superior | 9.5× enhancement |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | 1.45 | Comparable | Similar to Pd |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | 1.38 | Comparable | Similar to Pd |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | 1.61 | Comparable | Similar to Pd |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational and Experimental Resources for Catalyst Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian | Electronic structure calculation of descriptors |

| Catalyst Libraries | Transition metal sets (30 elements), Bimetallic combinations | Source of candidate materials for screening |

| Descriptor Analysis | d-band center, DOS similarity, ( \overline{CN} ) calculators | Quantification of structure-activity relationships |

| Experimental Validation | Flow reactors, SPR biosensors, Characterization (TEM, XPS) | Synthesis and performance testing of predicted candidates |

| Machine Learning | Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNN) | Accelerated prediction of descriptors (e.g., BEO) |

Analysis Techniques and Data Interpretation

Descriptor-Activity Relationships

The relationship between descriptors and catalytic activity is often visualized using volcano plots, which illustrate the Sabatier principle. The following diagram shows how multiple descriptors contribute to the overall catalyst screening and optimization process:

Diagram 2: Descriptor-activity relationship framework for catalyst screening.

Machine Learning Integration

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with DFT to accelerate descriptor evaluation. For example, message passing neural networks (MPNN) can predict oxygen binding energies (BEO) on doped Mo₂C surfaces with a mean absolute error of 0.176 eV compared to DFT, while dramatically reducing computational cost [37]. This approach is particularly valuable for screening large material spaces where full DFT calculations would be prohibitively expensive.

The integration of DFT-derived adsorption energies and activity descriptors with experimental validation provides a powerful framework for efficient catalyst screening. The protocols outlined in this Application Note demonstrate how descriptor-based approaches can significantly accelerate the discovery of novel catalysts, from bimetallic alloys for chemical synthesis to electrocatalysts for energy conversion. As computational methods continue to advance, particularly through integration with machine learning, the efficiency and accuracy of catalyst screening protocols will further improve, enabling more rapid development of high-performance catalytic materials for sustainable technology and pharmaceutical applications.

Rational Design of Alloys, Chalcogenides, and High-Entropy Alloys (HEAs)

The relentless pursuit of advanced materials for catalysis and energy applications is increasingly shifting from serendipitous discovery to rational design. Central to this paradigm shift is Density Functional Theory (DFT), a computational approach that provides atomic- and electronic-level insights into material behavior, thereby accelerating the development of catalysts and functional materials [3]. DFT calculations have become indispensable for elucidating reaction mechanisms, predicting catalytic activity, and understanding the influence of electronic structures on performance, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional trial-and-error methodologies [6].