Ensemble Methods vs. Single Models: A Comprehensive Validation Framework for Robust Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate ensemble learning methods against single-model approaches.

Ensemble Methods vs. Single Models: A Comprehensive Validation Framework for Robust Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate ensemble learning methods against single-model approaches. It covers the foundational principles of ensemble learning, explores its specific methodologies and applications in biomedical research, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents rigorous, comparative validation techniques. By synthesizing these core intents, the article serves as a practical guide for implementing ensemble strategies to enhance the predictive accuracy, robustness, and generalizability of machine learning models in critical areas such as drug-target interaction prediction and drug repurposing, ultimately aiming to accelerate and de-risk the drug development pipeline.

Ensemble Learning Fundamentals: Core Principles and the Case for Aggregation in Biomedical Research

Ensemble learning is a machine learning paradigm that combines multiple models, known as base learners or weak learners, to produce a single, more accurate, and robust strong collective model. The foundational principle is derived from the "wisdom of the crowds," where aggregating the predictions of multiple models leads to better overall performance than any single constituent model could achieve [1]. This approach mitigates the individual weaknesses and variances of base models, resulting in enhanced predictive accuracy, reduced overfitting, and greater stability across diverse datasets and problem domains.

In both theoretical and practical terms, ensemble methods have proven exceptionally effective. The formal theory distinguishes between weak learners—models that perform only slightly better than random guessing—and strong learners, which achieve arbitrarily high accuracy [2]. A landmark finding in computational learning theory demonstrated that weak learners can be combined to form a strong learner, providing the theoretical foundation for popular ensemble techniques like boosting [2]. Today, ensemble methods are indispensable tools in fields requiring high-precision predictions, including healthcare, business analytics, and drug development, where they consistently outperform single-model approaches in benchmark studies [3] [1].

Core Concepts: Weak Learners, Strong Learners, and Ensemble Architectures

Weak Learners vs. Strong Learners

The architecture of any ensemble model hinges on the relationship between its constituent parts and their collective output.

- Weak Learner: A weak learner is a model that performs just slightly better than random guessing. For binary classification, this means achieving an accuracy marginally above 50% [2]. These models are computationally inexpensive and easy to train but are not desirable for final predictions due to their low individual skill. A common example is a decision stump—a decision tree with only one split [2].

- Strong Learner: A strong learner is a model that can achieve arbitrarily high accuracy, making it the ultimate goal of most predictive modeling tasks [2]. However, creating a single, highly complex strong learner directly can be challenging due to overfitting, computational costs, and the difficulty of capturing all patterns within the data.

The power of ensemble learning lies in its ability to transform a collection of the former into the latter. Techniques like boosting explicitly focus on "converting weak learners to strong learners" by sequentially building models that correct the errors of their predecessors [2].

A Taxonomy of Ensemble Methods

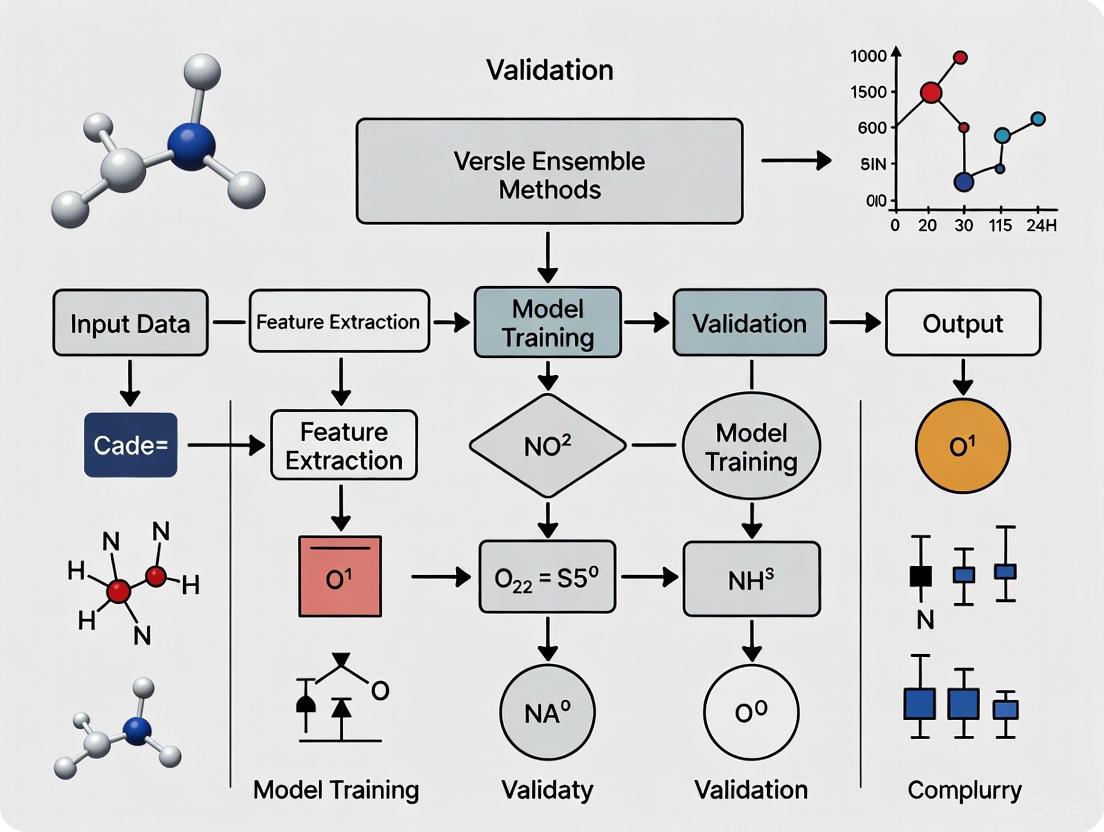

Ensemble methods can be categorized based on their underlying mechanics and how they integrate base learners. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the main ensemble architectures and how they combine weak learners to form a strong collective model.

The primary ensemble strategies include:

- Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): This method builds multiple weak learners in parallel, each trained on a different random subset (bootstrap sample) of the original training data. The final prediction is determined by averaging (regression) or majority voting (classification) the predictions of all individual models [1]. Random Forest is a quintessential bagging algorithm that combines the predictions of numerous decision trees [4] [5].

- Boosting: This method constructs weak learners sequentially. Each new model is trained to correct the residual errors made by the previous ones, focusing increasingly on harder-to-predict instances [2] [4]. Algorithms like AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM), are prominent examples that often achieve very high predictive accuracy [2] [6].

- Stacking (Stacked Generalization): This advanced technique combines multiple strong learners (or different types of models) using a meta-learner. The predictions of the base models (level-0) serve as input features for a meta-model (level-1), which is trained to make the final prediction [2] [6]. This approach can leverage the unique strengths of diverse algorithms.

Comparative Analysis of Key Ensemble Methods

While all ensemble methods aim to improve performance, their underlying mechanisms lead to different strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases. The table below provides a structured comparison of two of the most popular ensemble techniques: Random Forest (bagging) and Gradient Boosting (boosting).

Table 1: Comparison of Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Ensemble Methods

| Feature | Random Forest (Bagging) | Gradient Boosting (Boosting) |

|---|---|---|

| Model Building | Parallel, trees built independently [5]. | Sequential, trees built one after another to correct errors [5]. |

| Bias-Variance Trade-off | Lower variance, less prone to overfitting [4] [5]. | Lower bias, but can be more prone to overfitting, especially with noisy data [5]. |

| Training Time | Faster due to parallel training [5]. | Slower due to sequential nature [5]. |

| Robustness to Noise | Generally more robust to noisy data and outliers [5]. | More sensitive to outliers and noise [5]. |

| Hyperparameter Sensitivity | Less sensitive, easier to tune [4] [5]. | Highly sensitive, requires careful tuning (e.g., learning rate, trees) [4] [5]. |

| Interpretability | More interpretable; provides straightforward feature importance [5]. | Generally less interpretable due to sequential complexity [5]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Large, noisy datasets; need for robustness and faster training [4] [5]. | High-accuracy needs on complex, cleaner datasets; time for tuning is available [4] [5]. |

Experimental Validation: Ensemble Methods vs. Single Models

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Empirical validation is crucial for establishing the superiority of ensemble methods. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for a comparative study, as implemented in various research contexts [3] [6] [7].

Key methodological steps include:

- Data Preparation: Utilizing real-world datasets (e.g., from NHANES for health, Moodle for education) with comprehensive feature engineering and cleaning. Techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) are often applied to address class imbalance [3] [6].

- Model Training: Training a diverse set of single models (e.g., Logistic Regression, Single Decision Tree, SVM) and ensemble models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Stacking) on the same data splits. Cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold stratified) is essential for robust hyperparameter tuning and performance estimation [6].

- Performance Evaluation: Comparing models using metrics relevant to the task, such as:

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): For binary classification and mortality prediction [3] [6].

- Concordance Index (C-index): For time-to-event (survival) analysis [7].

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): For regression tasks, like predicting biological age [3].

- F1-Score: For classification tasks with imbalanced data [6].

- Interpretability and Fairness Analysis: Using tools like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret model predictions and ensure fairness across demographic groups [3] [6].

Numerous studies across different domains have systematically benchmarked ensemble methods against single models. The table below synthesizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Ensemble vs. Single Models

| Application Domain | Best Performing Model(s) | Reported Metric & Performance | Comparison to Single Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Age & Mortality Prediction [3] | Deep Biological Age (DNN), Ensemble Biological Age (EnBA) | AUC: 0.896 (DBA), 0.889 (EnBA)MAE: 2.98 (DBA), 3.58 (EnBA) years | Outperformed classical PhenoAge model. SHAP identified key predictors. |

| Academic Performance Prediction [6] | LightGBM (Gradient Boosting) | AUC: 0.953, F1: 0.950 | Ensemble methods (LightGBM, XGBoost, RF) consistently outperformed traditional algorithms (e.g., SVM). |

| Time-to-Event Analysis [7] | Ensemble of Cox PH, RSF, GBoost | Best Integrated Brier Score and C-index | The proposed ensemble method improved prediction accuracy and enhanced robustness across diverse datasets. |

| Sulphate Level Prediction [8] | Stacking Ensemble (SE-ML) | R²: 0.9997, MAE: 0.002617 | Ensemble learning (bagging, boosting, stacking) outperformed all individual methods. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

The experimental protocols rely on several key "research reagents"—software tools and algorithmic solutions—that are essential for replicating these studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ensemble Learning Experiments

| Item | Category | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| SMOTE | Data Preprocessing | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. Generates synthetic samples for minority classes to handle imbalanced datasets, crucial for fairness and accuracy [6]. |

| LASSO | Feature Selection | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator. Regularization technique for selecting the most predictive features from a large pool, improving model generalizability [3]. |

| XGBoost / LightGBM | Ensemble Algorithm | Highly optimized gradient boosting frameworks. Often achieve state-of-the-art results on tabular data and are widely used in benchmark studies [6] [1]. |

| Random Survival Forest | Ensemble Algorithm | Adaptation of Random Forest for time-to-event (survival) data, capable of handling censored observations [7]. |

| SHAP | Model Interpretation | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of any machine learning model, providing consistent and interpretable feature importance values [3] [6]. |

| Cross-Validation | Evaluation Protocol | A resampling procedure (e.g., 5-fold) used to assess how a model will generalize to an independent dataset, preventing overfitting during performance estimation [6]. |

The empirical evidence is clear: ensemble learning provides a powerful framework for developing strong collective models from weaker base learners, consistently delivering superior performance across diverse and challenging real-world problems. While Gradient Boosting often achieves the highest raw accuracy on complex, clean datasets, Random Forest offers exceptional robustness and faster training, making it an excellent choice for noisier data or for building strong baseline models [4] [5]. The choice between methods should be guided by the specific problem constraints, including dataset size, noise level, computational resources, and the need for interpretability.

Future research in ensemble learning is moving beyond pure predictive accuracy. Key frontiers include enhancing interpretability and fairness using tools like SHAP [3] [6], developing cost-sensitive ensembles tailored to business and operational objectives [1], and exploring the interface between ensemble methods and deep learning. For researchers and professionals in fields like drug development, where predictions impact critical decisions, mastering ensemble methods is no longer optional but essential for leveraging the full potential of machine learning.

Ensemble learning is a machine learning technique that combines multiple individual models, known as "base learners" or "weak learners," to produce better predictions than could be obtained from any of the constituent learning algorithms alone [9]. This approach transforms a collection of high-bias, high-variance models into a single, high-performing, accurate, and low-variance model [9]. The core philosophy underpinning ensemble methods is that by aggregating diverse predictive models, the ensemble can compensate for individual errors, capture different aspects of complex patterns, and ultimately achieve superior predictive performance and robustness.

The theoretical foundation for ensemble learning rests on the diversity principle, which states that ensembles tend to yield better results when there is significant diversity among the models [9]. This diversity can be quantified and measured using various statistical approaches [10], and its importance can be explained through a geometric framework where each classifier's output is viewed as a point in multidimensional space, with the ideal target representing the perfect prediction [9]. From a practical perspective, ensemble methods address the fundamental bias-variance trade-off in machine learning by combining multiple models that may individually have high bias or high variance but together create a more balanced and robust predictive system [11].

In fields such as drug discovery, where accurate predictions can significantly reduce costs and development time, ensemble methods have demonstrated remarkable success. For instance, in drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, ensemble models have outperformed single-algorithm approaches, with one study reporting that an AdaBoost classifier enhanced prediction accuracy by 2.74%, precision by 1.98%, and AUC by 1.14% over existing methods [12]. This performance advantage makes ensemble learning particularly valuable for real-world applications where predictive reliability is crucial.

The Theoretical Underpinnings of Diversity

The Geometric Framework of Ensemble Learning

Ensemble learning can be effectively explained using a geometric framework that provides intuitive insights into why diversity improves predictive performance [9]. Within this framework, the output of each individual classifier or regressor for an entire dataset is represented as a point in a multi-dimensional space. The target or ideal result is likewise represented as a point in this space, referred to as the "ideal point." The Euclidean distance serves as the metric to measure both the performance of a single model (the distance between its point and the ideal point) and the dissimilarity between two models (the distance between their respective points).

This geometric perspective reveals two fundamental principles. First, averaging the outputs of all base classifiers or regressors can lead to equal or better results than the average performance of all individual models. Second, with an optimal weighting scheme, a weighted averaging approach can potentially outperform any of the individual classifiers that make up the ensemble, or at least perform as well as the best individual model [9]. This mathematical foundation explains why properly constructed ensembles almost always outperform single-model approaches, provided sufficient diversity exists among the constituent models.

Measuring and Quantifying Diversity

The effectiveness of an ensemble depends critically on the diversity of its component models, which can be measured using various statistical approaches [10]. These measures generally fall into two categories: pairwise measures, which compute diversity for every pair of models, and global measures, which compute a single diversity value for the entire ensemble.

- Disagreement: This straightforward pairwise metric calculates how often predictions differ between two models, divided by the total number of predictions. Disagreement values range from 0 (no differing predictions) to 1 (every prediction differs) [10].

- Yule's Q: This pairwise statistic provides additional information about the nature of diversity, with positive values indicating that models correctly classify the same objects, and negative values suggesting models are wrong on different objects. A value of 0 indicates independent predictions [10].

- Entropy: A global diversity measure based on the concept that maximum disagreement occurs when half the predictions are correct and half are incorrect across the ensemble [10].

These quantification methods enable researchers to objectively assess and optimize ensemble composition, moving beyond intuitive notions of diversity to precise mathematical characterization.

Methodological Approaches to Generating Diversity

Fundamental Ensemble Strategies

Several core methodologies have been developed to systematically introduce diversity into ensemble construction, each with distinct mechanisms for promoting model variation:

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating): This parallel ensemble method creates diversity by training multiple instances of the same base algorithm on different random subsets of the training data, sampled with replacement [9] [11]. The final prediction typically aggregates predictions through averaging (for regression) or majority voting (for classification). Random Forests represent an extension of bagging that further promotes diversity by randomizing feature selection at each split [10].

Boosting: This sequential approach builds diversity by iteratively training models that focus on previously misclassified examples. Each new model assigns higher weights to instances that previous models got wrong, forcing subsequent models to pay more attention to difficult cases [9] [11]. This results in an additive model where each component addresses the weaknesses of its predecessors.

Stacking (Stacked Generalization): This heterogeneous ensemble method introduces diversity by combining different types of algorithms into a single meta-model. The base models make predictions independently, and a meta-learner then uses these predictions as features to generate the final prediction [11] [13]. Stacking leverages the complementary strengths of diverse algorithmic approaches.

Voting: As one of the simplest ensemble techniques, voting combines predictions from multiple models through either majority voting (hard voting) or weighted voting based on model performance or confidence (soft voting) [11].

Technical Implementation of Diversity

Beyond these broad strategies, several technical approaches can further enhance ensemble diversity:

- Training on different feature subsets: Ensembles can be trained using different combinations of available features or different transformations of original features, helping to capture different aspects of the data [10].

- Utilizing different algorithm types: Heterogeneous ensembles combine fundamentally different algorithm families (e.g., decision trees, support vector machines, neural networks) that inherently capture different patterns in the data and make different types of errors [10] [11].

- Incorporating diversity explicitly in error functions: Some advanced ensemble models directly incorporate diversity-promoting terms, such as negative correlation or squared Pearson correlation, into their error functions alongside the standard accuracy terms [13].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and diversity generation mechanisms for the three major ensemble learning approaches:

Distinguishing Between Beneficial and Detrimental Diversity

Not all diversity improves ensemble performance. Research distinguishes between "good diversity" (disagreement where the ensemble is correct) and "bad diversity" (disagreement where the ensemble is incorrect) [10]. In a majority vote ensemble, wasted votes occur when multiple models agree on a correct prediction beyond what is necessary, or when models disagree on an incorrect prediction. Maximizing ensemble efficiency requires increasing good diversity while decreasing bad diversity by reducing wasted votes [10].

A practical example illustrates this distinction: if a decision tree excels at identifying dogs but struggles with cats, while a logistic regression model excels with cats but struggles with dogs, their combination creates beneficial diversity. However, adding a third model that performs poorly on both categories would increase diversity without bringing benefits, representing detrimental diversity [10].

Experimental Validation and Comparative Performance

Quantitative Evidence from Benchmark Studies

Rigorous experimental studies across multiple domains provide compelling evidence for the performance advantages of diverse ensembles. The following table summarizes key findings from recent research:

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of Ensemble Methods vs. Single Models

| Domain/Application | Ensemble Method | Performance Metrics | Single Model Comparison | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance Prediction | LightGBM (Gradient Boosting) | AUC = 0.953, F1 = 0.950 | Outperformed traditional algorithms and Random Forest | [14] |

| Drug-Target Interaction Prediction | AdaBoost Classifier | Accuracy: +2.74%, Precision: +1.98%, AUC: +1.14% | Superior to existing single-model methods | [12] |

| MNIST Classification | Boosting (200 learners) | Accuracy: 0.961 | Showed improvement over Bagging (0.933) but with higher computational cost | [15] |

| Regression Tasks | Global and Diverse Ensemble Methods (GDEM) | Significant improvement on 45 datasets | Outperformed individual base learners and traditional ensembles | [13] |

| Customer Churn Prediction | Voting Classifier (Heterogeneous Ensemble) | Higher AUC scores | Superior to individual logistic regression model | [11] |

Computational Trade-offs: Performance vs. Cost

While ensemble methods consistently demonstrate superior predictive performance, this advantage comes with increased computational costs. A comparative analysis of Bagging versus Boosting revealed significant differences in this trade-off:

Table 2: Computational Cost Comparison: Bagging vs. Boosting

| Aspect | Bagging | Boosting | Experimental Context | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Time | Reference baseline | ~14x longer at 200 base learners | MNIST classification task | [15] |

| Performance Trajectory | Steady improvement then plateaus | Rapid improvement then potential overfitting | As ensemble complexity increases | [15] |

| Scalability with Ensemble Size | Near-constant time cost | Sharply rising time cost | With increasing base learners | [15] |

| Resource Consumption | Grows linearly | Grows quadratically | With ensemble complexity | [15] |

| Recommended Use Case | Complex datasets, high-performance devices | Simpler datasets, average-performing devices | Based on data complexity and hardware | [15] |

These findings highlight the importance of considering both performance gains and computational costs when selecting ensemble methods for practical applications. The concept of "algorithmic profit" – defined as performance minus cost – provides a useful framework for decision-makers balancing these competing factors [15].

Case Study: Ensemble Methods in Drug Discovery

Application to Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

The pharmaceutical domain provides compelling real-world evidence of ensemble methods' superiority, particularly in drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, where accurate predictions can significantly reduce drug development costs and time [12] [16]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that ensemble approaches consistently outperform single-model methods in this critical application.

The HEnsem_DTIs framework, a heterogeneous ensemble model configured with reinforcement learning, exemplifies this advantage. When evaluated on six benchmark datasets, this approach achieved sensitivity of 0.896, specificity of 0.954, and AUC of 0.930, outperforming baseline methods including decision trees, random forests, and support vector machines [16]. Similarly, another DTI prediction study utilizing an AdaBoost classifier reported improvements of 2.74% in accuracy, 1.98% in precision, and 1.14% in AUC over existing methods [12].

These ensemble systems typically address two major challenges in DTI prediction: high-dimensional feature space (handled through dimensionality reduction techniques) and class imbalance (addressed through improved under-sampling approaches) [16]. The success of ensembles in this domain stems from their ability to integrate complementary predictive patterns from multiple algorithms, each capturing different aspects of the complex relationships between drug characteristics and target properties.

Ensemble Transfer Learning for Drug Response Prediction

Beyond DTI prediction, ensemble methods have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in anti-cancer drug response prediction through ensemble transfer learning (ETL) [17]. This approach transfers patterns learned on source datasets (e.g., large-scale drug screening databases) to related target datasets with limited data, extending the classic transfer learning scheme through ensemble prediction.

In one comprehensive study, ETL was tested on four public in vitro drug screening datasets (CTRP, GDSC, CCLE, GCSI) using three representative prediction algorithms (LightGBM and two deep neural networks). The framework consistently improved prediction performance across three critical drug response applications: drug repurposing (identifying new uses for existing drugs), precision oncology (matching drugs to individual cancer cases), and new drug development (predicting response to novel compounds) [17].

The experimental workflow for validating ensemble transfer learning in drug response prediction typically follows this structured approach:

Essential Research Reagents for Ensemble DTI Prediction

Implementing effective ensemble methods for drug-target interaction prediction requires specific computational "research reagents" – tools, datasets, and algorithms that enable comprehensive experimental analysis:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ensemble Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Ensemble DTI Prediction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Features | Morgan fingerprints, Constitutional descriptors, Topological descriptors | Represent chemical structures as feature vectors for machine learning | [12] |

| Target Protein Features | Amino acid composition, Dipeptide composition, Pseudoamino acid composition | Encode protein sequences as machine-readable features | [12] |

| Class Imbalance Handling | SVM one-class classifier, SMOTE, Recommender systems | Address data imbalance between interacting and non-interacting pairs | [12] [16] |

| Base Classifiers | Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM, Neural Networks | Provide diverse predictive patterns for ensemble combination | [16] [14] |

| Validation Frameworks | 10-fold cross-validation, Hold-out validation, Stratified sampling | Ensure robust performance estimation and prevent overfitting | [12] [14] |

| Performance Metrics | AUC, Accuracy, Precision, F-score, MCC | Quantify predictive performance across multiple dimensions | [12] [16] |

The theoretical foundations and extensive experimental evidence consistently demonstrate that model diversity serves as the core mechanism behind the superior predictive performance and robustness of ensemble methods. By combining multiple weak learners that exhibit different error patterns, ensembles can compensate for individual deficiencies and produce more accurate, stable predictions than any single model could achieve alone.

The success of ensemble methods across diverse domains – from drug discovery to educational analytics – underscores the universal value of this approach. However, practitioners must carefully consider the trade-offs involved, particularly between predictive accuracy and computational costs, when selecting appropriate ensemble strategies for specific applications. As computational resources continue to improve and novel diversity-promoting techniques emerge, ensemble methods are poised to remain at the forefront of machine learning applications where predictive reliability is paramount.

The continuing evolution of ensemble methodologies – including automated ensemble configuration through reinforcement learning [16], advanced diversity measures [13], and sophisticated transfer learning frameworks [17] – promises to further enhance our ability to harness the power of diversity for solving increasingly complex predictive challenges in science and industry.

The bias-variance tradeoff represents a fundamental concept in machine learning that governs a model's predictive performance and its ability to generalize to unseen data. This tradeoff describes the tension between two sources of error: bias, which arises from overly simplistic model assumptions leading to underfitting, and variance, which results from excessive sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training data, causing overfitting [18] [19]. In supervised learning, the total prediction error can be decomposed into three components: bias², variance, and irreducible error, formally expressed as: Total Error = Bias² + Variance + Irreducible Error [20]. The irreducible error represents the inherent noise in the data that cannot be reduced by any model.

Ensemble learning methods provide a powerful framework for navigating this tradeoff by combining multiple individual models to create a collective intelligence that outperforms any single constituent model [21]. These methods have gained significant prominence in operational research and business analytics, with recent surveys indicating that 78% of organizations now deploy artificial intelligence in at least one business function [1]. By strategically leveraging diverse models, ensemble techniques can effectively manage the bias-variance tradeoff, reducing both sources of error simultaneously and creating more robust predictive systems capable of handling complex, real-world data patterns.

Theoretical Framework: Ensemble Methods as a Balancing Mechanism

The Statistical Foundation of Ensemble Learning

Ensemble learning operates on the principle that multiple weak learners can be combined to create a strong learner, a concept grounded in statistical theory, computational mathematics, and the fundamental nature of machine learning itself [21]. The mathematical elegance of ensemble learning becomes apparent when examining its error decomposition properties. For regression problems, the expected error of an ensemble can be expressed in terms of the average error of individual models minus the diversity among them [21]. This relationship demonstrates why diversity is crucial—without it, ensemble learning provides minimal benefit. For classification, ensemble accuracy is determined by individual accuracies and the correlation between their errors, with negatively correlated errors potentially enabling performance that dramatically exceeds that of the best individual model [21].

The effectiveness of ensemble methods stems from their ability to expand the hypothesis space, where ensembles can represent more complex functions than any single model could capture independently [21]. Each base model in the ensemble explores a different region of possible solutions, and the combination mechanism synthesizes these explorations into a more robust final hypothesis. This approach is particularly valuable for complex, high-dimensional problems where no single model architecture can adequately capture the full complexity of the underlying relationships.

Algorithmic Approaches to Bias-Variance Management

Different ensemble techniques address the bias-variance tradeoff through distinct mechanisms. Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) primarily reduces variance by training multiple models on different bootstrap samples of the data and aggregating their predictions [21] [22]. The statistical foundation of bagging lies in its ability to reduce variance without significantly increasing bias [21]. In contrast, boosting primarily reduces bias by sequentially training models where each new model focuses on instances that previous models misclassified [21] [22]. The theoretical foundation of boosting connects to several deep concepts in statistical learning theory, including margin maximization and stagewise additive modeling [21].

Stacking (stacked generalization) represents a more sophisticated approach that combines predictions from multiple diverse models using a meta-learner that learns the optimal weighting scheme based on the data [21] [22]. This approach recognizes that different models may perform better on different subsets of the feature space or under different conditions, and a smart combination should leverage these complementary strengths [21]. The theoretical justification for stacking comes from the concept of model selection and combination uncertainty, preserving valuable information from multiple models that might perform well on certain types of examples [21].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations of Major Ensemble Techniques

| Ensemble Method | Primary Error Reduction | Core Mechanism | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | Variance | Parallel training on bootstrap samples with aggregation | Variance reduction through averaging of unstable estimators |

| Boosting | Bias | Sequential error correction with instance reweighting | Stagewise additive modeling; margin maximization |

| Stacking | Both bias and variance | Meta-learning optimal combinations of diverse models | Model combination uncertainty reduction |

Experimental Validation: Quantitative Comparisons

Performance and Computational Tradeoffs

Recent experimental studies provide compelling empirical evidence regarding the performance and computational characteristics of different ensemble methods. A comprehensive 2025 study published in Scientific Reports conducted a comparative analysis of bagging and boosting approaches across multiple datasets with varying complexity, including MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and IMDB [15]. The researchers developed a theoretical model to compare these techniques in terms of performance, computational costs, and ensemble complexity, validated through extensive experimentation.

The results demonstrated that as ensemble complexity increases (measured by the number of base learners), bagging and boosting exhibit distinct performance patterns. For the MNIST dataset, as ensemble complexity increased from 20 to 200 base learners, bagging's performance improved from 0.932 to 0.933 before plateauing, while boosting improved from 0.930 to 0.961 before showing signs of overfitting [15]. This pattern confirms the theoretical expectation that boosting achieves higher peak performance but becomes more susceptible to overfitting at higher complexities.

A critical finding concerns computational requirements: at an ensemble complexity of 200 base learners, boosting required approximately 14 times more computational time than bagging, indicating substantially higher computational costs [15]. Similar patterns were observed across all four datasets, confirming the generality of these findings and revealing consistent trade-offs between performance and computational costs.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Dataset Complexities

| Dataset | Ensemble Method | Performance (20 learners) | Performance (200 learners) | Relative Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNIST | Bagging | 0.932 | 0.933 | 1x (baseline) |

| Boosting | 0.930 | 0.961 | ~14x | |

| CIFAR-10 | Bagging | 0.723 | 0.728 | 1x (baseline) |

| Boosting | 0.718 | 0.752 | ~12x | |

| CIFAR-100 | Bagging | 0.512 | 0.519 | 1x (baseline) |

| Boosting | 0.508 | 0.537 | ~15x | |

| IMDB | Bagging | 0.881 | 0.884 | 1x (baseline) |

| Boosting | 0.879 | 0.903 | ~13x |

Methodological Protocols for Experimental Validation

The experimental validation of ensemble methods requires carefully designed methodologies to ensure reliable and reproducible comparisons. The referenced study employed standardized protocols across datasets to enable meaningful comparisons [15]. For each dataset, researchers established baseline performance metrics using standard implementations of bagging and boosting algorithms. The ensemble complexity was systematically varied from 20 to 200 base learners to analyze scaling properties, with performance measured on held-out test sets to ensure generalization assessment.

Computational costs were quantified using wall-clock time measurements under controlled hardware conditions, with all experiments conducted on standardized computing infrastructure to ensure comparability [15]. The evaluation incorporated multiple runs with different random seeds to account for variability, with reported results representing averaged performance across these runs. This methodological rigor ensures that the observed performance differences reflect true algorithmic characteristics rather than experimental artifacts.

For the MNIST dataset, the experimental protocol involved training on 60,000 images and testing on 10,000 images, with performance measured using classification accuracy [15]. Similar standardized train-test splits were employed for the other datasets, with CIFAR-10 using 50,000 training and 10,000 test images, CIFAR-100 using 50,000 training and 10,000 test images, and the IMDB sentiment dataset using a standardized 25,000 review training set and 25,000 review test set.

Research Reagents and Experimental Toolkit

Implementing rigorous experiments in ensemble learning requires specific computational tools and methodological approaches. The following table details essential "research reagents" for conducting comparative studies of ensemble methods for bias-variance tradeoff management.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ensemble Learning Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | Provides standardized testing environments for fair algorithm comparison | MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, IMDB, OpenML-CC18 benchmarks |

| Ensemble Algorithms | Core implementations of ensemble methods | Scikit-learn Bagging/Stacking classifiers, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, Random Forests |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies predictive accuracy and generalization capability | Classification Accuracy, AUC-ROC, F1-Score, Log Loss, Balanced Accuracy |

| Computational Profiling Tools | Measures resource utilization and scalability | Python time/timeit modules, memory_profiler, specialized benchmarking suites |

| Model Interpretation Frameworks | Provides insights into model decisions and bias-variance characteristics | SHAP, LIME, partial dependence plots, learning curves, validation curves |

Implementation Workflows and Methodological Processes

The experimental comparison of ensemble methods follows structured workflows that ensure methodological rigor and reproducible results. The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for evaluating bias-variance tradeoffs in ensemble methods:

Advanced Ensemble Architecture

Recent research has introduced innovative ensemble architectures that further optimize the bias-variance tradeoff. The Hellsemble framework represents a novel approach that leverages dataset complexity during both training and inference [23]. This method incrementally partitions the dataset into "circles of difficulty" by iteratively passing misclassified instances from simpler models to subsequent ones, forming a committee of specialized base learners. Each model is trained on increasingly challenging subsets, while a separate router model learns to assign new instances to the most suitable base model based on inferred difficulty [23].

The following diagram illustrates this sophisticated ensemble architecture:

Experimental results demonstrate that Hellsemble achieves competitive performance with classical machine learning models on benchmark datasets from OpenML-CC18 and Tabzilla, often outperforming them in terms of classification accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency and interpretability [23]. This approach exemplifies the ongoing innovation in ensemble architectures that specifically target optimal bias-variance management.

The theoretical and experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that ensemble methods provide powerful mechanisms for managing the bias-variance tradeoff in machine learning. The choice between bagging, boosting, and stacking involves fundamental tradeoffs between performance, computational requirements, and implementation complexity. Bagging offers computational efficiency and stability, making it suitable for resource-constrained environments or when working with complex datasets on high-performing hardware [15]. Boosting typically achieves higher peak performance but at substantially higher computational cost and with greater risk of overfitting at high ensemble complexities [15]. Stacking provides flexibility by leveraging diverse models but introduces additional complexity in training the meta-learner.

For researchers and practitioners in drug development and scientific fields, these findings offer strategic guidance for selecting ensemble approaches based on specific project requirements. When computational resources are limited or when working with particularly complex datasets, bagging methods often provide the most practical solution. When maximizing predictive accuracy is the primary objective and computational resources are available, boosting approaches typically yield superior performance. Stacking offers a compelling middle ground, potentially capturing the diverse strengths of multiple modeling approaches while maintaining robust performance across varied data characteristics.

Future research directions in ensemble learning include deeper integration with neural networks and deep learning architectures, developing more interpretable ensemble methods to address the growing importance of explainable AI, and creating more tailored applications that shift from error-based to cost-sensitive or profit-driven learning [1]. As ensemble methods continue to evolve, they will likely play an increasingly important role in solving complex predictive modeling challenges across scientific domains, including drug discovery, clinical development, and biomedical research.

Ensemble learning is a foundational methodology in machine learning that combines multiple base models to produce a single, superior predictive model. The core premise is that a collection of weak learners, when appropriately combined, can form a strong learner, mitigating the individual errors and biases of its constituents [24] [25]. This approach has proven dominant in many machine learning competitions and real-world applications, from healthcare and materials science to education [15] [26] [6]. The technique is particularly valuable for its ability to address the perennial bias-variance trade-off, with different ensemble strategies targeting different components of a model's error [27].

This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of the three major ensemble paradigms: Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking. It is framed within the broader thesis of validating ensemble methods against single models, a critical consideration for researchers and professionals in data-intensive fields like drug development who require robust, reliable predictive performance. We synthesize current experimental data and detailed methodologies from recent research across various scientific domains to offer a clear, evidence-based analysis of these powerful techniques.

Core Paradigms: Mechanisms and Workflows

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating)

Mechanism: Bagging, short for Bootstrap Aggregating, is a parallel ensemble technique designed primarily to reduce model variance and prevent overfitting. It operates by creating multiple bootstrap samples (random subsets with replacement) from the original training dataset [24] [25]. A base learner, typically a high-variance model like a decision tree, is trained independently on each of these subsets. The final prediction is generated by aggregating the predictions of all individual models; this is done through majority voting for classification tasks or averaging for regression tasks [24] [27].

Key Algorithms: Random Forest is the most prominent example of bagging applied to decision trees, introducing an additional layer of randomness by selecting a random subset of features at each split [25].

Boosting

Mechanism: Boosting is a sequential ensemble technique that focuses on reducing bias. Instead of training models in parallel, boosting trains base learners one after the other, with each new model aiming to correct the errors made by the previous ones [24] [25]. The algorithm assigns weights to both the data instances and the individual models. Instances that were misclassified by earlier models are given higher weights, forcing subsequent learners to focus more on these difficult cases [25]. The final model is a weighted sum (or weighted vote) of all the weak learners, where more accurate models are assigned a higher weight in the final prediction [25] [27].

Key Algorithms: Popular boosting algorithms include AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting, and its advanced derivatives like Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and LightGBM [6] [27].

Stacking (Stacked Generalization)

Mechanism: Stacking is a more flexible, heterogeneous ensemble method. It combines multiple different types of base models (level-0 models) by training a meta-model (level-1 model) to learn how to best integrate their predictions [24] [28]. The base models, which can be any machine learning algorithm (e.g., decision trees, SVMs, neural networks), are first trained on the original training data. Their predictions on a validation set (or from cross-validation) are then used as input features to train the meta-model, which learns to produce the final prediction [25] [28]. This process allows stacking to leverage the unique strengths and inductive biases of diverse model types.

Recent Variants: Innovations like Data Stacking have been proposed, which feed the original input data alongside the base learners' predictions to the meta-model. This approach has been shown to provide superior forecasting performance, refining results even when weak base algorithms are used [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical structure and data flow of each ensemble method, highlighting their parallel or sequential nature and how predictions are combined.

Comparative Experimental Performance

Empirical evidence from recent scientific studies consistently demonstrates that ensemble methods can significantly outperform single models. The following tables summarize quantitative results from diverse, real-world research applications, providing a basis for objective comparison.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Material Science and Concrete Strength Prediction

| Model Type | Specific Model | R² Score (G*) | R² Score (δ) | Dataset / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking Ensemble | Bayesian Ridge Meta-Learner | 0.9727 | 0.9990 | Predicting Rheological Properties of Modified Asphalt [29] |

| Boosting Ensemble | XGBoost | 0.983 (CS) | - | Predicting Concrete Strength with Foundry Sand & Coal Bottom Ash [30] |

| Single Models | KNN, Decision Tree, etc. | Lower | Lower | Predicting Rheological Properties of Modified Asphalt [29] |

Table 2: Performance and Computational Trade-offs (MNIST Dataset)

| Ensemble Method | Ensemble Complexity (Base Learners) | Performance (Accuracy) | Relative Computational Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | 20 | 0.932 | 1x (Baseline) |

| Bagging | 200 | 0.933 (plateau) | ~1x |

| Boosting | 20 | 0.930 | ~14x |

| Boosting | 200 | 0.961 (pre-overfit) | ~14x |

Note: Data adapted from a comparative analysis of Bagging vs. Boosting. Ensemble complexity refers to the number of base learners. Computational time for Boosting is substantially higher due to its sequential nature [15].

Table 3: Performance in Multi-Omics Clinical Outcome Prediction and Education

| Application Domain | Best Performing Model(s) | Key Performance Metric | Runner-Up Model(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Cancer Prediction | PB-MVBoost, AdaBoost (Soft Vote) | High AUC (Up to 0.85) | Other Ensemble Methods [26] |

| Student Performance Prediction | LightGBM (Boosting) | AUC = 0.953, F1 = 0.950 | Stacking Ensemble (AUC = 0.835) [6] |

Analysis of Experimental Findings

The aggregated data leads to several key conclusions:

- Superiority over Single Models: Across domains, from materials science (asphalt, concrete) to bioinformatics, ensemble methods consistently and significantly outperform single machine learning models [29] [30].

- The Accuracy-Cost Trade-off: Boosting algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) frequently achieve the highest raw accuracy and AUC scores, as seen in concrete strength prediction and educational analytics [30] [6]. However, this comes at a substantial computational cost, with boosting requiring approximately 14 times more computational time than bagging at similar ensemble complexity [15].

- Diminishing Returns and Stability: Bagging methods like Random Forest show more stable performance growth, with accuracy plateauing as more base learners are added. They are less prone to overfitting on complex datasets and offer a favorable profile when computational efficiency is a priority [15].

- Context-Dependent Stacking Performance: While stacking is a powerful and flexible framework, it does not always guarantee superiority. In some studies, well-tuned boosting models still outperformed stacking ensembles [6]. Its success heavily depends on the diversity of the base learners and the choice of an appropriate meta-learner.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of the results cited in this guide, this section outlines the standard methodologies employed in the referenced studies.

General Workflow for Benchmarking Ensemble Models

A typical experimental protocol for comparing ensemble methods involves the following stages, which are also visualized in the workflow diagram below:

- Data Compilation & Preprocessing: A dataset is compiled from experimental results or existing benchmarks. Preprocessing includes handling missing values, detecting outliers (e.g., using Local Outlier Factor - LOF), and often normalizing or standardizing features [29] [30].

- Feature Selection: Identifying the most relevant input variables is critical. This can be done through domain knowledge or automated feature selection techniques to reduce dimensionality and improve model generalizability [28].

- Data Splitting & Resampling: The dataset is split into training and testing sets. To handle class imbalance, especially in clinical or educational data, techniques like Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) are frequently applied to the training set only to avoid data leakage [6].

- Model Training with Tuning: Base models and ensemble frameworks are trained. Hyperparameter tuning is essential and is commonly performed using K-fold cross-validation (often with K=5) combined with optimization techniques like Bayesian optimization [29] [30].

- Validation & Performance Evaluation: The tuned models are evaluated on the held-out test set. Common metrics include Accuracy, Area Under the Curve (AUC), F1-score, R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [30] [6].

- Interpretability & Fairness Analysis (Optional but Important): For high-stakes fields like healthcare and education, models are analyzed for interpretability and fairness using tools like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to identify influential features and check for biases across demographic groups [29] [6].

Specific Protocol for Novel Stacking Variants

The protocol for developing and validating a novel Stacking variant, such as Data Stacking [28], involves specific modifications:

- Base Learner Diversity: A wide array of structurally diverse base learners is selected (e.g., Decision Trees, SVMs, Neural Networks, Gradient Boosting).

- Data Stacking Architecture: The meta-model is trained not only on the predictions of the base learners but also on the original input features. This concatenation of base learner predictions and original data provides the meta-learner with more context to make a final decision.

- Comparative Benchmarking: The proposed variant is rigorously compared against single models, classical Stacking, and other existing ensemble variants using multiple error metrics (MAE, nRMSE) and statistical tests to confirm superior performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

In the context of computational research, "research reagents" translate to the essential software tools, algorithms, and data processing techniques required to implement and validate ensemble methods.

Table 4: Essential Tools for Ensemble Method Research

| Tool / Solution | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost / LightGBM | Boosting Algorithm | High-performance gradient boosting framework; reduces bias and often achieves state-of-the-art accuracy. | Predicting concrete compressive strength [30] or student academic risk [6]. |

| Random Forest | Bagging Algorithm | Creates a robust ensemble of decision trees via bootstrapping and feature randomness; reduces variance. | Baseline model for high-dimensional data; providing diverse base learners for a stacking ensemble. |

| Scikit-learn | Python Library | Provides implementations for Bagging, Boosting (AdaBoost), Voting, and tools for model tuning and evaluation. | Building and benchmarking standard ensemble models and preprocessing data. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Interpretability Tool | Explains the output of any ML model by quantifying the contribution of each feature to the prediction. | Identifying key predictive factors in asphalt rheology [29] or ensuring fairness in educational models [6]. |

| SMOTE | Data Preprocessing Technique | Synthetically generates samples for the minority class to address class imbalance and mitigate model bias. | Balancing datasets in clinical outcome prediction [26] or student performance forecasting [6]. |

| Bayesian Optimizer | Hyperparameter Tuning Tool | Efficiently navigates the hyperparameter space to find the optimal configuration for a model, minimizing validation error. | Tuning the number of estimators, learning rate, and tree depth in boosting models [29]. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Model Validation Protocol | Robustly estimates model performance by rotating the validation set across the data, reducing overfitting. | Standard practice during model training and tuning in almost all cited studies [29] [30]. |

The validation of ensemble methods against single models is a cornerstone of modern predictive analytics. The evidence from recent scientific literature firmly establishes that Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking offer significant performance improvements across a wide array of challenging domains.

- Bagging is the go-to choice for stabilizing high-variance models and is highly effective when computational efficiency and robustness are primary concerns.

- Boosting often delivers the highest predictive accuracy at the cost of greater computational resources and a higher risk of overfitting if not carefully controlled. It excels in tasks where maximizing performance is critical.

- Stacking provides a flexible framework for leveraging model diversity. While its performance can be unmatched with careful design, it introduces complexity and is not an automatic guarantee of success.

The choice between these paradigms is not a matter of which is universally "best," but rather which is most appropriate for the specific research problem, data characteristics, and operational constraints. The ongoing innovation in ensemble methods, such as novel Stacking variants, continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in machine learning, offering powerful tools for researchers and professionals in drug development and other scientific fields.

The Critical Need for Enhanced ML Models in Drug Discovery and Development

The traditional drug discovery pipeline is notoriously lengthy and expensive, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a single new drug to market [31]. In this high-stakes environment, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool, promising to accelerate target identification, compound design, and efficacy prediction. However, a significant limitation persists: reliance on single-model approaches often struggles with the profound complexity and multi-scale nature of biological and chemical data. These standalone models—whether Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, or decision trees—frequently exhibit limitations in generalization, robustness, and predictive accuracy when faced with heterogeneous, sparse biomedical datasets [32] [33].

This review posits that ensemble learning methods represent a critical advancement over single-model paradigms. By strategically combining multiple models, ensemble methods mitigate the weaknesses of individual learners, resulting in enhanced predictive performance, greater stability, and superior generalization. The integration of these methods is not merely an incremental improvement but a necessary evolution to fully leverage artificial intelligence in creating more efficient and reliable drug discovery pipelines. Evidence from recent studies, detailed in the following sections, demonstrates that ensemble approaches consistently outperform state-of-the-art single models across key tasks, including pharmacokinetic prediction and drug solubility estimation, thereby validating their central role in modern computational drug discovery.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Ensemble Methods vs. Single Models

Experimental data from recent studies provides compelling evidence for the superiority of ensemble methods. The table below summarizes a direct performance comparison across critical drug discovery applications, highlighting the measurable advantages of ensemble strategies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ensemble vs. Single Model Approaches in Drug Discovery Tasks

| Application Area | Specific Task | Best Single Model (Performance) | Ensemble Method (Performance) | Key Performance Metric | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK/ADME Prediction [34] | Predicting pharmacokinetic parameters | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Stacking Ensemble (GNN, Transformer, etc.) | R² = 0.90 [34] | R² = 0.92 [34] |

| Transformer | Stacking Ensemble | R² = 0.89 [34] | R² = 0.92 [34] | ||

| Drug Formulation [35] | Predicting drug solubility in polymers | Decision Tree (DT) | AdaBoost with DT (ADA-DT) | R² = 0.9738 [35] | R² = 0.9738 [35] |

| Predicting activity coefficient (γ) | K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | AdaBoost with KNN (ADA-KNN) | R² = 0.9545 [35] | R² = 0.9545 [35] | |

| Association Prediction [33] | Predicting drug-gene-disease triples | Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) | R-GCN + XGBoost Ensemble | AUC ~0.92 [33] | AUC ~0.92 [33] |

The data unequivocally shows that ensemble methods achieve top-tier performance. In PK prediction, the Stacking Ensemble model's R² of 0.92 indicates it explains a greater proportion of variance in the data than any single model [34]. Similarly, in formulation development, ensemble methods like AdaBoost enhanced base models to achieve exceptionally high R² values, above 0.95 [35]. For complex association predictions, integrating a graph network with an ensemble classifier (XGBoost) achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92, demonstrating strong predictive power for potential drug targets and mechanisms [33].

Experimental Protocols for Ensemble Model Validation

The superior performance of ensemble models is underpinned by rigorous and domain-appropriate experimental methodologies. The following protocols detail how leading studies train, validate, and benchmark these models.

Protocol for Stacking Ensemble in PK Prediction

This protocol is derived from a study that benchmarked a Stacking Ensemble model against GNNs and Transformers for predicting pharmacokinetic parameters [34].

- Data Curation: A large dataset of over 10,000 bioactive compounds was sourced from the ChEMBL database. Critical pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) were the prediction targets.

- Base Model Selection: A diverse set of base learners was chosen to create a strong ensemble, including:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): To natively model molecular graph structure.

- Transformers: To capture long-range dependencies within molecular sequences.

- Traditional ML models: Such as Random Forest and XGBoost.

- Ensemble Strategy - Stacking: The predictions of the base models were used as input features for a final meta-learner. The meta-learner was trained to optimally combine these predictions to produce the final, enhanced output.

- Validation & Benchmarking: Model performance was evaluated using robust metrics like R-squared (R²) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Hyperparameters for all models were meticulously tuned using Bayesian optimization to ensure a fair comparison. The Stacking Ensemble was validated against each base model to demonstrate its superior accuracy [34].

Protocol for AdaBoost in Drug Solubility Prediction

This protocol outlines the use of the AdaBoost ensemble to predict drug solubility and activity coefficients in polymers, a key task in formulation development [35].

- Data Preprocessing: A dataset of over 12,000 entries with 24 molecular descriptor input features was utilized. Outliers were identified and removed using Cook's distance to ensure model stability. Features were normalized using Min-Max scaling to a [0, 1] range.

- Base Model Preparation: Three weak learners were selected for their complementary strengths:

- Decision Trees (DT)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

- Ensemble Strategy - AdaBoost: The AdaBoost algorithm was applied to each base model sequentially. It works by fitting a base model (e.g., a Decision Tree) to the data, then identifying the data points it predicted incorrectly. Subsequent models are then forced to focus on these hard-to-predict instances by increasing their weight. The process repeats, and the final prediction is a weighted majority vote of all sequential models.

- Optimization: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) was used for feature selection. The Harmony Search (HS) algorithm was employed for hyperparameter tuning, optimizing both the base models and the ensemble itself [35].

Protocol for Hybrid Graph & Ensemble Association Prediction

This protocol describes a sophisticated hybrid approach for predicting associations between drugs, genes, and diseases, which is crucial for target identification and drug repurposing [33].

- Heterogeneous Graph Construction: A knowledge graph was built containing three node types (drugs, genes, diseases) and multiple relationship types (e.g., "binds-to," "causes," "treats").

- Feature Embedding with R-GCN: A Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) was used to learn vector representations (embeddings) for each node in the graph. The R-GCN aggregates information from a node's neighbors, respecting the different types of relationships, to generate high-quality, context-aware embeddings.

- Ensemble Strategy - Hybrid Classifier: The embedded features of drug-gene-disease triples were extracted and used as input features for a powerful ensemble classifier, XGBoost. This model was then trained to classify whether a potential association exists.

- Evaluation: The model was evaluated using standard classification metrics like AUC and F1-score, demonstrating its strong ability to uncover hidden relationships in complex biological networks [33].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the core hybrid protocol combining graph networks with ensemble learning.

Diagram 1: Hybrid graph ensemble prediction workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The development and validation of advanced ML models in drug discovery rely on a foundation of specific data, software, and computational resources. The table below details key "research reagents" essential for work in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ML-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent / Solution | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [34] | Bioactivity Database | Provides a large, structured repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for training and benchmarking ML models. | Sourcing over 10,000 compound structures and associated PK data for model training [34]. |

| Molecular Descriptors [35] | Computed Chemical Features | Quantitative representations of molecular structure (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) that serve as input features for ML models. | 24 input descriptors used to predict drug solubility in polymers [35]. |

| Heterogeneous Knowledge Graph [33] | Structured Data Network | Integrates multi-source data (drugs, genes, diseases) into a unified graph to model complex biological relationships for pattern discovery. | Constructing a graph with drug, gene, disease nodes and their relationships for association prediction [33]. |

| XGBoost [33] | Ensemble ML Software | A powerful, scalable implementation of gradient-boosted decision trees, often used as a standalone model or as a meta-learner in stacking ensembles. | Acting as the final classifier on top of graph-based embeddings to predict drug-gene-disease triples [33]. |

| Bayesian Optimization [34] | Computational Algorithm | An efficient strategy for the global optimization of black-box functions, used to automate and improve the hyperparameter tuning process for ML models. | Fine-tuning the hyperparameters of a Stacking Ensemble model to maximize predictive R² [34]. |

| Harmony Search (HS) Algorithm [35] | Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm | A melody-based search algorithm used to find optimal or near-optimal solutions, applied to hyperparameter tuning in complex ML workflows. | Optimizing parameters for AdaBoost and its base models in solubility prediction [35]. |

The empirical evidence and methodological comparisons presented in this guide compellingly validate the thesis that ensemble methods represent a critical enhancement over single-model approaches in drug discovery. The consistent pattern of superior performance—whether through stacking, boosting, or hybrid graph-ensemble architectures—demonstrates that these methods are uniquely capable of handling the data sparsity, complexity, and heterogeneity of biomedical data [34] [35] [33]. As the field progresses towards more integrated and holistic AI platforms [36], the principles of ensemble learning will be foundational. For researchers and drug development professionals, prioritizing the development and adoption of these robust, validated modeling strategies is not just an technical choice, but a necessary step to shorten development timelines, reduce costs, and ultimately deliver new therapeutics to patients more efficiently.

Implementing Ensemble Methods: Techniques and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

In the pursuit of developing more accurate and robust predictive models, machine learning researchers and practitioners have increasingly turned to ensemble methods, which combine multiple base models to produce a single, superior predictive model. This approach validates the fundamental thesis that ensemble methods consistently outperform single models across diverse domains and data types. Among ensemble techniques, boosting algorithms have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness by sequentially combining weak learners to create a strong learner with significantly reduced bias and enhanced predictive accuracy. The core principle behind boosting aligns with the concept of the "wisdom of crowds," where collective decision-making surpasses individual expert judgment [37].

This comparative guide provides an objective analysis of two pioneering boosting algorithms: Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) and Gradient Boosting. We examine their mechanistic differences, performance characteristics, and practical applications within the framework of ensemble method validation, with particular relevance for researchers and professionals in data-intensive fields such as drug development and biomedical research. Through experimental data and methodological comparisons, we demonstrate how these algorithms address the limitations of single-model approaches while highlighting their distinct strengths and implementation considerations.

Fundamental Concepts: How Boosting Algorithms Work

The Boosting Framework

Boosting is an ensemble learning technique that converts weak learners into strong learners through a sequential, iterative process. Unlike bagging methods that train models in parallel, boosting trains models sequentially, with each subsequent model focusing on the errors of its predecessors [22] [37]. This approach enables the algorithm to progressively minimize both bias and variance, although the primary strength of boosting lies in its exceptional bias reduction capabilities.

The term "weak learner" refers to a model that performs slightly better than random guessing, such as a shallow decision tree (often called a "decision stump" when containing only one split) [38] [39]. By combining multiple such weak learners, boosting algorithms create a composite model with substantially improved predictive power. The two most prominent boosting variants—AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting—diverge in their specific approaches to error correction and model combination, which we explore in the subsequent sections.

Algorithmic Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows for AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting, highlighting their sequential learning processes and key differentiating mechanisms.

AdaBoost Sequential Learning Process: AdaBoost iteratively adjusts sample weights to focus on misclassified instances, combining weak learners through weighted voting [38] [39].

Gradient Boosting Sequential Learning Process: Gradient Boosting builds models sequentially on the residuals of previous models, gradually minimizing errors through gradient descent [40] [41].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Across Domains

Geotechnical Engineering Applications

A comprehensive study published in Scientific Reports evaluated six machine learning algorithms for predicting the ultimate bearing capacity (UBC) of shallow foundations on granular soils, using a dataset of 169 experimental results [42]. The performance metrics across multiple algorithms provide valuable insights into the relative effectiveness of different ensemble methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms in Geotechnical Engineering

| Algorithm | Training R² | Testing R² | Overall Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| AdaBoost | 0.939 | 0.881 | 1 |

| k-Nearest Neighbors | 0.922 | 0.874 | 2 |

| Random Forest | 0.937 | 0.869 | 3 |

| XGBoost | 0.931 | 0.865 | 4 |

| Neural Network | 0.912 | 0.847 | 5 |

| Stochastic Gradient Descent | 0.843 | 0.801 | 6 |

In this study, AdaBoost demonstrated superior performance with the highest R² values on both training (0.939) and testing (0.881) sets, earning the top ranking among all evaluated models [42]. The researchers employed a consistent evaluation framework using multiple metrics including Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R²), ensuring a fair comparison. The input features included foundation width (B), depth (D), length-to-width ratio (L/B), soil unit weight (γ), and angle of internal friction (φ), with model interpretability enhanced through SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs).

Financial Market Predictions

A study published in Scientific African compared ensemble learning algorithms for high-frequency trading on the Casablanca Stock Exchange, utilizing a dataset of 311,812 transactions at millisecond precision [43]. The research evaluated performance using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) across daily, monthly, and annual prediction horizons.

Table 2: Ensemble Algorithm Performance in High-Frequency Trading

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Stacking | Leverages multiple diverse learners; creates robust meta-model | Best overall forecasting performance across different periods |

| Boosting (AdaBoost, XGBoost) | High predictive accuracy; effective bias reduction | Strong performance, particularly on structured tabular data |

| Bagging (Random Forest) | Reduces variance; parallel training capability | Good performance with high-variance base learners |

While stacking ensemble methods achieved the best performance in this financial application, both AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting demonstrated strong predictive capabilities [43]. The study highlighted boosting's particular effectiveness on structured data, consistent with findings from other domains.

Pavement Engineering Applications

Recent research in Scientific Reports developed novel ensemble learning models for predicting asphalt volumetric properties using approximately 200 experimental samples [44]. The study implemented XGBoost (an optimized Gradient Boosting variant) and LightGBM, enhanced with ensemble techniques and hyperparameter optimization using Artificial Protozoa Optimizer (APO) and Greylag Goose Optimization (GGO). XGBoost demonstrated excellent R² and RMSE values across all output variables, with further improvements achieved through ensemble and optimization techniques.

Methodological Deep Dive: Algorithmic Mechanisms

AdaBoost: Adaptive Weight Adjustment

AdaBoost operates by maintaining a set of weights over the training samples and adaptively adjusting these weights after each iteration [38]. The algorithm follows this methodological protocol:

Initialization: Assign equal weights to all training samples: ( w_i = \frac{1}{N} ) for ( i = 1,2,...,N )

Iterative Training: For each iteration ( t = 1,2,...,T ):

- Train a weak learner (typically a decision stump) using the current sample weights

- Calculate the weighted error rate: ( \epsilont = \sum{i=1}^N wi \cdot I(yi \neq \hat{y}_i) )

- Compute the classifier weight: ( \alphat = \frac{1}{2} \ln \left( \frac{1-\epsilont}{\epsilon_t} \right) )

- Update sample weights: ( wi \leftarrow wi \cdot \exp(-\alphat \cdot yi \cdot \hat{y}_i) )

- Renormalize weights so they sum to 1

Final Prediction: Combine all weak learners through weighted majority vote: ( H(x) = \text{sign}\left( \sum{t=1}^T \alphat h_t(x) \right) )

The algorithm focuses increasingly on difficult cases by raising the weights of misclassified samples after each iteration [38] [39]. Each weak learner is assigned a weight (( \alpha_t )) in the final prediction based on its accuracy, giving more influence to more competent classifiers.

Gradient Boosting: Residual Error Optimization

Gradient Boosting employs a different approach, building models sequentially on the residual errors of previous models using gradient descent [40] [41]. The methodological protocol involves:

Initialize Model: With a constant value: ( F0(x) = \arg\min\gamma \sum{i=1}^N L(yi, \gamma) )

- For regression with MSE loss, this is typically the mean of the target values

Iterative Residual Modeling: For ( m = 1 ) to ( M ):

- Compute pseudo-residuals: ( r{im} = -\left[ \frac{\partial L(yi, F(xi))}{\partial F(xi)} \right]{F(x)=F{m-1}(x)} )

- Fit a weak learner ( h_m(x) ) to the pseudo-residuals

- Compute multiplier ( \gammam = \arg\min\gamma \sum{i=1}^N L(yi, F{m-1}(xi) + \gamma hm(xi)) )

- Update the model: ( Fm(x) = F{m-1}(x) + \nu \cdot \gammam hm(x) )

- where ( \nu ) is the learning rate

Final Model: Output ( F_M(x) ) after ( M ) iterations

Unlike AdaBoost, which adjusts sample weights, Gradient Boosting directly fits new models to the residual errors, with each step moving in the negative gradient direction to minimize the loss function [40] [41]. The learning rate parameter (( \nu )) controls the contribution of each tree, helping to prevent overfitting.

Technical Comparison: Key Differences and Similarities

Algorithmic Distinctions

Table 3: Technical Comparison of AdaBoost and Gradient Boosting

| Characteristic | AdaBoost | Gradient Boosting |

|---|---|---|

| Error Correction Mechanism | Adjusts sample weights to focus on misclassified instances | Fits new models to residual errors of previous models |

| Base Learner Structure | Typically uses decision stumps (one-split trees) | Usually employs trees with 8-32 terminal nodes |

| Model Combination | Weighted majority vote based on classifier performance | Equally weighted models with predictive capacity restricted by learning rate |