From Coordination to Catalysis: The Organometallic Revolution in Drug Discovery and Chemical Biology

This article explores the paradigm shift from traditional coordination chemistry to the dynamic field of organometallic complexes in chemical and biomedical research.

From Coordination to Catalysis: The Organometallic Revolution in Drug Discovery and Chemical Biology

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift from traditional coordination chemistry to the dynamic field of organometallic complexes in chemical and biomedical research. It traces the foundational history and defining characteristics of organometallic compounds, detailing their unique covalent metal-carbon bonds that distinguish them from classical coordination complexes. The scope encompasses cutting-edge methodological applications, particularly in drug discovery, highlighting antimicrobial organoarsenicals, antimalarial and anticancer ferrocene-containing compounds, and catalytic organometallic drug candidates. The article also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including toxicity and synthetic hurdles, while providing a comparative validation of organometallic approaches against established therapeutic strategies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes historical context, current applications, and future directions for organometallic chemistry in advancing biomedical science.

Defining the Frontier: From Metal Coordination to Covalent Metal-Carbon Bonds

The field of organometallic chemistry, defined by the presence of direct, covalent metal-carbon bonds, represents a paradigm shift in chemical exploration. Its genesis can be traced to the early 19th century with the serendipitous discovery of Zeise's Salt by Danish pharmacist William Christoffer Zeise in the 1820s [1]. This compound, potassium trichloro(ethylene)platinate(II) hydrate (K[PtCl₃(C₂H₄)]·H₂O), is recognized historically as one of the first, if not the very first, organometallic compound [2] [1]. Its formation, initially observed from the reaction of platinum(IV) chloride with boiling ethanol, presented a structural enigma that persisted for over a century [1]. The correct characterization of its π-bonded ethylene ligand was only firmly established in the 1950s alongside the structural elucidation of ferrocene, marking the end of the proto-organometallic period—a time of empirical discovery without a theoretical framework [1]. This compound, with its platinum atom in a square planar geometry and an η²-ethylene ligand, became the foundational prototype upon which the principles of organometallic chemistry were built [1].

Zeise's Salt: Structure, Bonding, and Fundamental Properties

Structural Elucidation and Key Bonding Concepts

The long-standing mystery of Zeise's Salt's structure was resolved through X-ray crystallography, revealing a square planar platinum center coordinated to three chlorido ligands and one ethylene molecule [1]. The ethylene ligand is bound side-on to the platinum atom, with its C-C bond approximately perpendicular to the coordination plane [1]. This bonding is a hallmark of organometallic chemistry and is explained by the Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson model [1]. This model describes a synergistic interaction where:

- σ-Donation: The π-electrons of the ethylene's carbon-carbon double bond are donated to an empty d-orbital on the platinum atom.

- π-Backbonding: Electrons from a filled d-orbital of platinum are donated back into the empty π* antibonding orbital of the ethylene ligand [1].

This back-and-forth donation has measurable consequences: it reduces the carbon-carbon bond order, elongates the C-C distance, and lowers its vibrational frequency. In Zeise's Salt, the C-C bond stretching frequency is observed at 1516 cm⁻¹, a significant reduction from the 1623 cm⁻¹ found in free ethylene, indicating a bond order of approximately 1.54 [1]. The distance from the midpoint of the C-C double bond to the platinum center is about 2.015 Å, slightly shorter than in the original Zeise's Salt (2.022 Å), indicating a subtle tuning of the bond with different substituents [2].

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis and Characterization of Zeise's Salt and Derivatives

Synthesis of Zeise's Salt: The hydrate form is commonly prepared from K₂[PtCl₄] and ethylene in the presence of a catalytic amount of SnCl₂. The water of hydration can be removed under vacuum [1].

Synthesis of Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA) Derivatives (e.g., Pt-Propene-ASA): The modern synthesis of biologically active Zeise's Salt derivatives involves a multi-step process [2]:

- Ligand Synthesis (Steglich Esterification):

- Reagents: Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), the respective alkenol (e.g., 3-buten-1-ol for Pt-Propene-ASA), N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), dry dichloromethane.

- Procedure: ASA is activated with DCC in the presence of catalytic DMAP in dry dichloromethane at 0°C to form an active N-acyl species. This intermediate subsequently reacts with the alkenol, with the reaction mixture warmed to room temperature and stirred to form the ester ligand.

- Complexation:

- Reagents: Synthesized ester ligand, Zeise's salt, dry ethanol.

- Procedure: The ester ligand is complexed with Zeise's salt in dry ethanol by stirring at elevated temperature for approximately 3 hours. The final organometallic compounds are hygroscopic and light-sensitive, requiring storage in a desiccator protected from light [2].

Characterization Techniques:

- X-ray Crystallography: Determines precise molecular geometry, bond lengths, and angles [2].

- NMR Spectroscopy (¹H and ¹³C): Used for full molecular characterization. For dynamic studies, the stability of complexes in different media (water, physiological NaCl, phosphate-buffered saline) can be investigated using analytical methods like Capillary Electrophoresis [2].

- IR Spectroscopy: Confirms the reduced C-C bond stretching frequency of the coordinated ethylene ligand [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents in Organometallic Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Platinum Salts (K₂[PtCl₄], PtCl₄) | Starting material for synthesizing platinum-based organometallic complexes. |

| Zeise's Salt (K[PtCl₃(C₂H₄)]·H₂O) | Fundamental building block for creating new Zeise's Salt derivatives. |

| N,N'-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) | Coupling reagent used in Steglich esterification to activate carboxylic acids. |

| 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) | Acyl transfer catalyst that accelerates esterification reactions. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Solvents for NMR spectroscopy analysis; allows for structural elucidation. |

| SnCl₂ | Catalyst used in the modern preparation of Zeise's Salt from K₂[PtCl₄] and ethylene. |

The Evolutionary Leap: From Structural Curiosity to Medicinal Agent

Expanding the Organometallic Landscape

The confirmation of Zeise's Salt's structure opened the floodgates for organometallic chemistry. A pivotal milestone was the discovery and structural determination of ferrocene in 1952 [3]. This iron complex, with two cyclopentadienyl ligands in a sandwich structure, demonstrated the vast structural diversity and unique stability possible in organometallic compounds, far beyond the simple π-complex of Zeise's Salt [3]. This period saw the exploration of various classes of organometallics, including metallocenes, half-sandwich complexes, and metal carbonyls, each with distinct stereochemistry and reactivity profiles [3]. The field moved from studying a single curious compound to establishing general principles governing metal-carbon bonds, leveraging the unique physico-chemical properties of organometallics—such as structural diversity, ligand exchange, redox activity, and catalytic properties—for application-oriented goals [4].

Zeise's Salt Derivatives in Drug Discovery and Development

A prime example of this evolution is the rational design of Zeise's Salt derivatives as anticancer agents. This research is driven by the limitations of conventional platinum drugs like cisplatin, which suffer from dose-limiting side effects and drug resistance [2] [3]. Modern bioorganometallic chemistry aims to overcome these disadvantages by designing compounds that target biological sites other than DNA [2].

A key strategy involves conjugating the Zeise's Salt moiety with bioactive molecules. Researchers have synthesized a homologous series of compounds where the trichloro(ethylene)platinate(II) unit is linked to acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin) via alkyl spacers of varying lengths (n = 1–4) [2]. These compounds, such as Pt-Propene-ASA (1a), were designed to inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, particularly the COX-2 isoform, which is overexpressed in various cancers [2].

Table 2: Biological Activity Data of Zeise's Salt Derivatives with ASA Substructure [2]

| Compound | Alkyl Spacer (n) | COX Inhibition Potency | Antiproliferative Activity (IC₅₀ in μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeise's Salt | N/A | Moderate | Inactive at tested concentrations |

| ASA (Aspirin) | N/A | Reference COX inhibitor | Inactive at tested concentrations |

| Pt-Propene-ASA (1a) | 1 | Enhanced vs. Zeise's Salt | ~30 - 50 (vs. HT-29 & MCF-7 cells) |

| Pt-Butene-ASA (2a) | 2 | Higher than n=1 | ~30 - 50 (vs. HT-29 & MCF-7 cells) |

| Pt-Pentene-ASA (3a) | 3 | Generally higher with longer chain | ~30 - 50 (vs. HT-29 & MCF-7 cells) |

| Pt-Hexene-ASA (4a) | 4 | Highest in series | ~30 - 50 (vs. HT-29 & MCF-7 cells) |

The biological evaluation of these derivatives reveals a promising profile [2]:

- Dual Mechanism of Action: They function as both COX inhibitors and antiproliferative agents, unlike Zeise's salt or ASA alone.

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR): The length of the alkyl spacer influences biological activity; complexes with longer chains typically cause higher COX inhibition.

- Enhanced Cytotoxicity: The derivatives exhibit potent growth inhibitory effects against colon carcinoma (HT-29) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines, with IC₅₀ values in the 30–50 µM range, whereas Zeise's Salt and ASA alone show no such activity at the concentrations tested.

This exemplifies the modern organometallic regime: using fundamental understanding to rationally design complexes with tailored stability, specificity, and multi-targeting mechanisms of action for improved therapeutic outcomes.

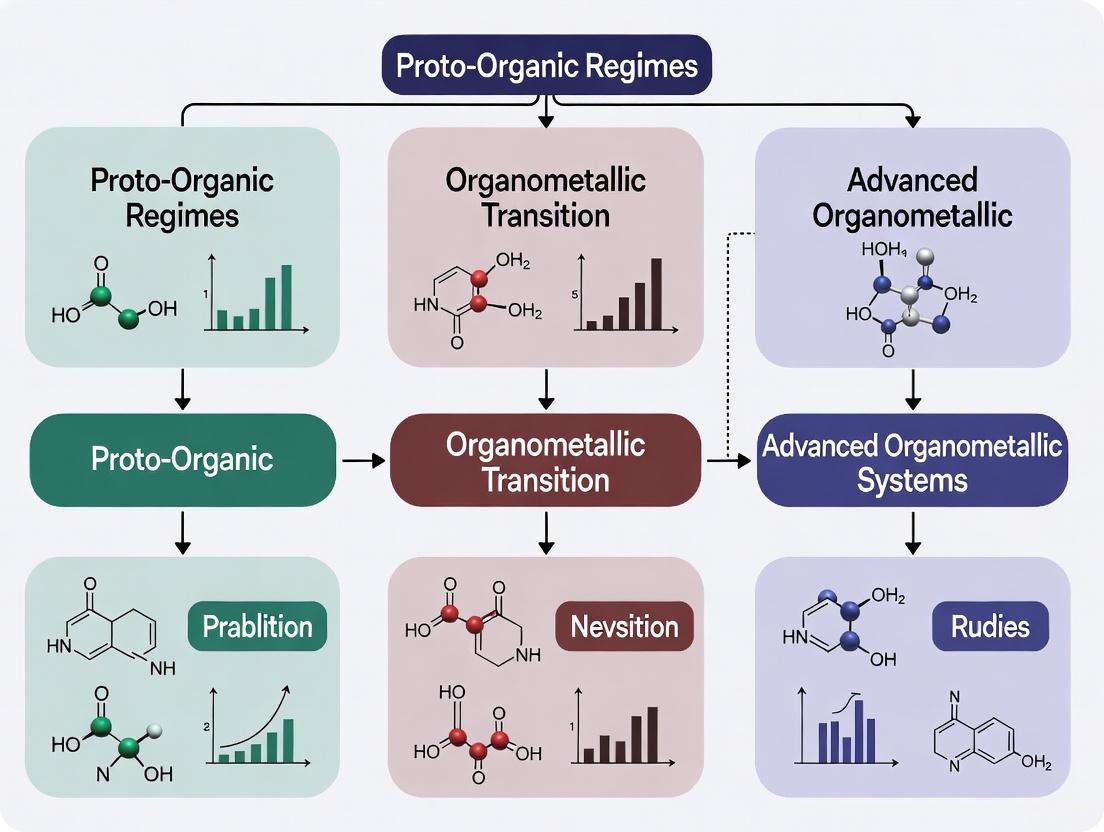

Visualization of Evolution and Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the key evolutionary pathway from Zeise's Salt to modern drug candidates and their proposed mechanism of action.

Figure 1: The evolution from the discovery of foundational organometallic compounds to the rational design of modern therapeutic agents.

The journey from Zeise's Salt to modern organometallics encapsulates the evolution of chemical research from proto-organic serendipity to a disciplined organometallic regime. What began with a single, poorly understood yellow crystal has matured into a sophisticated field capable of tailoring metal-carbon complexes for specific biological functions. The development of Zeise's Salt derivatives as cytotoxic COX inhibitors exemplifies this transition, demonstrating how historical milestones provide the foundational knowledge for contemporary drug discovery. This ongoing research, leveraging unique organometallic properties—structural diversity, redox activity, and ligand exchange kinetics—continues to offer promising avenues for overcoming the limitations of traditional chemotherapeutics, firmly establishing organometallic chemistry as a vital frontier in medicinal science.

In the landscape of inorganic chemistry, the distinction between organometallic complexes and classical coordination compounds represents a fundamental divide that correlates with distinct bonding models, reactivity paradigms, and applications in research and industry. This division is central to understanding the transition from proto-organic to organometallic regimes in chemical exploration, marking an evolutionary shift in how chemists manipulate metal-ligand interactions for synthetic purposes. While both classes involve a central metal atom or ion surrounded by ligands, the defining criterion rests on the nature of the metal-ligand bond, particularly the presence or absence of direct metal-carbon bonds [5]. This distinction is not merely taxonomic; it carries profound implications for electronic structure, spectroscopic properties, and functional behavior in applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to materials science. For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding this boundary is essential for rational design of catalytic systems, metal-based therapeutics, and novel materials with tailored properties.

Core Definitions and Fundamental Distinctions

Defining Characteristics

The classification of chemical compounds containing metals and organic components follows a hierarchical structure based on bonding interactions:

Organometallic Complexes: Chemical compounds containing at least one direct, covalent bond between a metal atom and a carbon atom of an organic molecule or fragment [5] [6]. The metal component can include transition metals, alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, lanthanides, actinides, and metalloids such as boron, silicon, and selenium [5]. The carbon-metal bond in these compounds is generally highly covalent, though the degree of ionic character varies considerably across the periodic table [5].

Classical Coordination Compounds: Complex ions or molecules in which ions or molecules (ligands) are bound to a central metal atom or ion typically through donor atoms with lone pairs (most commonly N, O, S, or halogens) [7] [8]. These complexes are formed via Lewis acid-base interactions where the metal acts as an electron pair acceptor and ligands act as electron pair donors [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Definitions and Characteristics

| Feature | Organometallic Complexes | Classical Coordination Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Bonding | Direct metal-carbon covalent bonds | Coordinate covalent bonds through heteroatoms (N, O, S, halogens) |

| Metal Centers | Transition metals, main group metals, lanthanides, actinides | Predominantly transition metals |

| Carbon Interaction | Direct bonding to metal center | Carbon atoms may be present in organic ligands but not directly bonded to metal |

| Typical Ligands | CO, alkenes, alkyls, cyclopentadienyl, carbenes | H₂O, NH₃, CN⁻, EDTA, halides |

| Electron Counting | Often follows 18-electron rule | Often follows 18-electron rule with different donor models |

The Bonding Criterion in Practice

The presence of a direct metal-carbon bond establishes the organometallic classification, but several nuanced scenarios require careful consideration:

Borderline Cases: Compounds where canonical anions share negative charge between carbon and a more electronegative atom (e.g., enolates) require structural evidence of a direct metal-carbon bond for organometallic classification. For example, lithium enolates typically contain only Li-O bonds and are not considered organometallic, whereas zinc enolates (Reformatsky reagents) contain both Zn-O and Zn-C bonds, qualifying as organometallic [5].

Special Carbon Ligands: Compounds containing "inorganic" carbon ligands such as carbon monoxide (metal carbonyls), cyanide, and carbide are generally considered organometallic despite their inorganic character [5].

Metalorganic Compounds: Some chemists use the term "metalorganic" to describe coordination compounds containing organic ligands regardless of direct M-C bonds, creating potential ambiguity in classification [5].

Structural and Electronic Differences

Bonding Models and Electronic Structure

The electronic structure and bonding models provide theoretical frameworks for understanding the behavior of both classes of compounds:

Ligand Field Theory (LFT) Applications: LFT describes the bonding, orbital arrangement, and electronic characteristics of coordination complexes [9]. It represents an application of molecular orbital theory to transition metal complexes and explains crucial phenomena including color, magnetic properties, and stability trends [9] [10]. For organometallic complexes, additional considerations for π-backbonding with carbon-based ligands become essential for understanding their unique electronic structures.

π-Backbonding in Organometallics: A distinctive feature of many organometallic complexes is metal-to-ligand π-bonding (π-backbonding), particularly with ligands such as CO and alkenes [9]. This occurs when electrons from filled metal d-orbitals are donated into empty π* anti-bonding orbitals of the ligand, creating a synergic effect that strengthens the metal-ligand bond [9] [10]. This bonding modality is rarely significant in classical coordination compounds.

Ligand Classification: Ligands can be classified according to their donor and acceptor abilities [10]:

- σ donors only (e.g., NH₃): No orbitals with appropriate symmetry for π bonding

- π donors (e.g., F⁻, Cl⁻): Possess filled p orbitals that can donate electrons to metal orbitals

- π acceptors (e.g., CO, CN⁻): Possess vacant π* or d orbitals that can accept electron density from metal d-orbitals

Table 2: Electronic Structure and Bonding Characteristics

| Parameter | Organometallic Complexes | Classical Coordination Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Bonding Model | Covalent M-C bonds with possible π-backbonding | Coordinate covalent bonds with electrostatic contributions |

| Typical Ligand Field | Often strong field (large Δ) due to π-acceptor ligands | Variable depending on ligand position in spectrochemical series |

| Carbon Electronic Character | Nucleophilic (partial negative charge) | Not applicable (no direct M-C bond) |

| Metal Oxidation States | Often low oxidation states stabilized by π-acceptor ligands | Full range of oxidation states, with higher states stabilized by O/N-donor ligands |

| Synergic Bonding | Common with π-acceptor ligands (e.g., CO, alkenes) | Rare |

Geometric Considerations and Coordination Numbers

Both organometallic and coordination compounds exhibit diverse geometries determined by metal electronic configuration, ligand steric demands, and metal-ligand bonding requirements:

Common Coordination Geometries: Octahedral, tetrahedral, and square planar geometries occur in both compound classes, though specific preferences emerge based on metal identity and oxidation state [8].

Hapticity Considerations: Organometallic chemistry introduces the concept of hapticity (η), which describes how contiguous atoms of a π-system coordinate to a metal center [5]. For example, ferrocene features two η⁵-cyclopentadienyl ligands where all five carbon atoms bond to the iron center [5].

Chelation Effects: Both classes of compounds exhibit chelation, where multidentate ligands form more stable complexes than their monodentate analogs [8]. The chelate effect operates similarly in both domains, though organometallic chelators often employ carbon-based binding modes.

Identification Workflow for Compound Classification

Experimental Characterization and Differentiation

Analytical Techniques for Distinction

Differentiating between organometallic complexes and classical coordination compounds requires a multifaceted analytical approach. The following experimental protocols provide definitive evidence for classification:

X-ray Crystallography: This is the most definitive technique for establishing the presence or absence of direct metal-carbon bonds [5]. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction can precisely locate atomic positions and measure M-C bond distances, providing unambiguous structural evidence. The experimental protocol involves growing high-quality single crystals, mounting them on a diffractometer, collecting reflection data, and solving the phase problem to determine electron density maps.

Infrared Spectroscopy: IR spectroscopy is particularly diagnostic for identifying carbonyl (CO) ligands in organometallic complexes [5]. The C-O stretching frequency (νCO) provides information about the bonding mode:

- Terminal CO: 1850-2125 cm⁻¹

- Bridging CO: 1750-1850 cm⁻¹

- The position and number of CO stretches indicate the coordination geometry and electron density at the metal center

- Lower νCO frequencies indicate greater π-backbonding into CO π* orbitals

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: NMR is essential for characterizing organometallic compounds in solution [5]:

- ¹³C NMR directly probes carbon atoms bound to metals, with chemical shifts characteristic of metal-carbon bonding

- ¹H NMR of ligands (e.g., cyclopentadienyl, alkyl groups) provides structural information

- Dynamic NMR can study fluxional processes common in organometallic complexes

Elemental Analysis and Mass Spectrometry: Combustion analysis establishes empirical formulas, while mass spectrometry (especially ESI and MALDI) provides molecular weight confirmation and fragmentation patterns characteristic of metal-carbon bonds [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, C₆D₆, DMSO-d₆) | NMR spectroscopy for structural elucidation | Must be rigorously dried and degassed for air-sensitive compounds |

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Identification of functional groups and bonding modes | ATR accessory useful for air-sensitive solids; solution cells for liquids |

| Single Crystal X-ray Diffractometer | Definitive structural determination | Requires high-quality single crystals; low-temperature capability beneficial |

| Schlenk Line/Glovebox | Air-free manipulation of sensitive compounds | Essential for most organometallic and many coordination compounds |

| Silica Gel/TLC Plates | Monitoring reaction progress and purity | Various mesh sizes for column chromatography; TLC with UV/chemical visualization |

| Elemental Analyzer | Determination of C, H, N composition | Requires pure, dry samples; compares experimental and theoretical percentages |

Air-Free Techniques and Special Handling

A significant practical distinction between many organometallic complexes and classical coordination compounds lies in their air and moisture sensitivity:

Organometallic Handling: Many organometallic compounds are air-sensitive and require specialized handling techniques [5]. This typically involves the use of Schlenk lines or gloveboxes for manipulation under inert atmosphere (argon or nitrogen) [5]. Some organometallics, such as triethylaluminum, are pyrophoric and will ignite spontaneously upon exposure to air [5].

Coordination Compound Stability: Classical coordination compounds generally exhibit greater stability toward air and moisture, though exceptions exist (e.g., some low-valent metal complexes).

Analytical Techniques for Compound Characterization

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The distinction between organometallic complexes and classical coordination compounds carries significant implications for research methodologies and applications in pharmaceutical development:

Reactivity and Synthetic Applications

Nucleophilic Character: Organometallic complexes typically feature nucleophilic carbon centers due to the lower electronegativity of metals compared to carbon [6]. This imparts fundamentally different reactivity compared to classical coordination compounds, making organometallics invaluable as catalysts and stoichiometric reagents in organic synthesis [5] [6].

Catalytic Applications: Organometallic complexes dominate the field of homogeneous catalysis, enabling transformations such as hydrogenation, hydroformylation, polymerization, and cross-coupling reactions [5]. Their ability to undergo oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and migratory insertion mechanisms distinguishes them from most classical coordination compounds.

Pharmaceutical Relevance: While classical coordination compounds have a longer history in medicine (e.g., platinum anticancer drugs), organometallic complexes are emerging as promising therapeutic agents with unique modes of action [5]. Bioorganometallic chemistry explores compounds such as methylcobalamin (a form of Vitamin B₁₂), which contains a cobalt-methyl bond [5].

Electronic and Magnetic Properties

The differing bonding models between the two classes of compounds lead to distinct electronic and magnetic properties:

Magnetic Behavior: The magnetic properties of coordination compounds provide indirect evidence of orbital energy levels used in bonding [10]. Strong-field ligands (often found in organometallic complexes) tend to produce low-spin complexes, while weak-field ligands (common in classical coordination compounds) often yield high-spin complexes [10].

Spectrochemical Series: Ligands can be ordered according to their ability to split d-orbital energy levels [9] [10]: CN⁻ > CO > phen > NO₂⁻ > en > NH₃ > NCS⁻ > H₂O > F⁻ > RCOO⁻ > OH⁻ > Cl⁻ > Br⁻ > I⁻ π-acceptor ligands (common in organometallics) generally produce larger splitting than π-donor ligands (common in classical coordination compounds).

The distinction between organometallic complexes and classical coordination compounds represents a fundamental conceptual boundary in inorganic chemistry with far-reaching implications for research and application. The presence of direct metal-carbon bonds in organometallic complexes imparts unique electronic structures, reactivity patterns, and physical properties that differentiate them from classical coordination compounds bonded through heteroatoms. For researchers and drug development professionals, this classification system provides a framework for predicting compound behavior, selecting appropriate characterization methodologies, and designing new materials with tailored properties. As chemical exploration continues to evolve toward increasingly sophisticated molecular designs, understanding these core definitions remains essential for advancing both fundamental knowledge and practical applications across the chemical sciences.

The transition from proto-organic to organometallic regimes in chemical exploration represents a paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry, moving beyond purely organic molecules and classical coordination complexes. Organometallic compounds, characterized by at least one direct, covalent metal-carbon bond, offer unique therapeutic possibilities due to their distinctive physicochemical properties [11] [3]. These properties include structural diversity that surpasses organic compounds, tunable redox and catalytic activities, and controlled ligand exchange kinetics [11] [12]. This shift has created new avenues for attacking drug-resistant cancers, overcoming limitations of traditional chemotherapeutics like cisplatin, which suffer from resistance development and severe side effects [3]. The exploration of this chemical space is driven by motifs with proven biological relevance: sandwich complexes, carbonyls, and carbenes, each contributing unique attributes to medicinal applications.

Structural Motif 1: Sandwich Complexes

Sandwich complexes feature metal centers positioned between two cyclic, planar, π-bonded ligands. First discovered with ferrocene, this structural class has expanded to include various ring sizes and metal centers, creating what are termed "super sandwich" compounds when involving larger ring systems [13].

Medicinal Applications and Mechanisms

Ferrocene and Ferrocifen Derivatives: Ferrocene itself exhibits low toxicity, but its incorporation into known pharmacophores can yield potent anticancer agents. Ferrocifen, a ferrocene-tamoxifen hybrid, demonstrates efficacy against both estrogen receptor-positive and negative breast cancer cells, suggesting a dual mechanism involving both receptor binding and redox activation [11] [3]. The redox activity of ferrocene facilitates generation of reactive oxygen species, inducing cancer cell death via oxidative stress pathways [3].

Lanthanide Sandwich Complexes: Recent research has explored lanthanide-based sandwich complexes utilizing cyclooctatetraenyl (C8H8) and cyclononatetraenyl (C9H9) ligands. These complexes, such as [(η9-C9H9)Ln(η8-C8H8)] (where Ln = Nd, Sm, Dy, Er), exhibit single-molecule magnet behavior and have potential applications in quantum computing and magnetic resonance imaging [13].

Half-Sandwich Anticancer Agents: Ru(η6-p-cymene) and Rh(η5-C5Me5) complexes represent prominent half-sandwich structures with demonstrated anticancer activity. These "piano-stool" complexes offer three coordination sites for functionalization, enabling fine-tuning of anticancer properties and selectivity [14].

Table 1: Representative Medicinal Sandwich Complexes and Their Activities

| Complex | Metal | Ligands | Medicinal Activity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrocifen | Fe | Cp rings, tamoxifen derivative | Anticancer (breast) | Active against ERα+ and ERα- cell lines; redox-activated [11] [3] |

| [(η8-C8H8)Er(η9-C9H9)] | Er | C8H8, C9H9 | Single Molecule Magnet | Potential for quantum computing and MRI applications [13] |

| [Rh(η5-C5Me5)(HQCl-pip)Cl]Cl | Rh | C5Me5, 8-hydroxyquinoline | Anticancer (MDR cells) | IC50 = 0.22 μM against MDR MES-SA/Dx5 cells; high selectivity [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Heteroleptic Lanthanide Sandwich Complexes

Objective: Synthesis of [(η9-C9H9)Ln(η8-C8H8)] (Ln = Nd, Sm, Dy, Er) heteroleptic sandwich complexes [13].

Procedure:

- Synthesis of KC9H9 precursor: Prepare potassium cyclononatetraenyl following the method of Katz et al. [13].

- Preparation of [(η8-C8H8)LnI(thf)n]: React lanthanide metal (Nd, Sm, Dy, or Er) with cyclooctatetraene and iodine in hot THF. For Dy and Er, activate the metal by in situ amalgamation. Reaction times vary from 2 days (Nd, Sm) to 3-4 weeks (Dy, Er) [13].

- Metathesis Reaction: React [(η8-C88H)LnI(thf)2] complexes with KC9H9 in refluxing toluene for 24 hours [13].

- Isolation: Cool the reaction mixture to precipitate the product. Collect crystals by filtration and dry under vacuum. Yields typically range from 31-36% [13].

Characterization: Confirm structure by X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and elemental analysis. Magnetic properties can be investigated using SQUID magnetometry [13].

Structural Motif 2: Metal Carbonyls

Metal carbonyl complexes feature carbon monoxide ligands bound to metal centers and represent fundamental structures in organometallic chemistry with growing medicinal importance.

Medicinal Applications and Mechanisms

Technetium Carbonyl Radiopharmaceuticals: Technetium-99m carbonyl complexes serve as versatile platforms for developing single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging agents. The fac-[TcI(CO)3]+ core exhibits exceptional stability and allows for functionalization with targeting biomolecules [15]. This core structure maintains integrity under physiological conditions, making it ideal for diagnostic applications.

Anticancer Activity: Metal carbonyl complexes, particularly those with rhenium and manganese, have demonstrated potential as anticancer agents. Carbon monoxide release in controlled manner may contribute to cytotoxic effects, although the precise biological mechanisms remain under investigation [3].

Table 2: Medicinal Metal Carbonyl Complexes and Applications

| Complex | Metal | Application | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| fac-[TcI(CO)3]+ core | Tc | SPECT Imaging | Highly stable; versatile functionalization; ideal for biomolecule conjugation [15] |

| [ReI(CO)3]+ complexes | Re | Anticancer | Cytotoxic activity; potential for CO delivery [3] |

| [MnI(CO)3]+ complexes | Mn | Anticancer | Photoactivated CO release; cytotoxic effects [3] |

Experimental Protocol: Preparation of the fac-[TcICl3(CO)3]2- Synthon

Objective: Synthesis of fac-[TcICl3(CO)3]2-, a fundamental precursor for technetium-99m radiopharmaceuticals [15].

Procedure:

- Carbonyl Source Preparation: Use CO gas or solid CO-releasing molecules such as potassium boranocarbonate or boranocarbonates [15].

- Reduction and Carbonylation: Reduce pertechnetate (TcO4-) in aqueous solution under a CO atmosphere in the presence of BH4- as reducing agent [15].

- Acidification: Treat the intermediate with concentrated HCl to form fac-[TcICl3(CO)3]2- [15].

- Purification: Isolate as the (NEt4)2[fac-TcICl3(CO)3] salt for characterization and storage [15].

Characterization: Analyze by infrared spectroscopy (characteristic CO stretches at ~2000 cm-1), NMR spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography [15].

Alternative Method: For facilities with radiation protection restrictions, use fac-[TcI2(μ–Cl)3(CO)6]– as an alternative precursor, which can be prepared under milder conditions [15].

Structural Motif 3: N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (NHCs)

N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) are strong σ-donor ligands that form exceptionally stable bonds with metal centers, creating complexes with superior stability for biological applications compared to their phosphine counterparts [16].

Medicinal Applications and Mechanisms

Gold(I) NHC Anticancer Agents: Alkynylgold(I) NHC complexes demonstrate promising antiproliferative activity against cancer cells. The most active complex (5f, featuring a 4-fluoroethynylbenzene ligand) showed increased cellular uptake and high albumin affinity (~90%), suggesting potential for improved bioavailability and tumor targeting [17]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate dipole moment influences activity, with larger dipole moments correlating with enhanced antiproliferative effects [17].

Antimicrobial Silver NHC Complexes: Silver-NHC complexes exhibit potent antimicrobial properties, with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values in the low μg/mL range against various bacterial strains including Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [16]. The exceptional stability of silver-NHC complexes (d/b ratios 7.8-12.68) makes them effective transmetallating agents for preparing other metal-NHC complexes [16].

Multifunctional NHC Therapeutic Agents: NHC complexes of other metals including rhodium, ruthenium, iridium, and palladium have demonstrated diverse biological activities including antibacterial, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory effects [16] [12].

Table 3: Bioactive N-Heterocyclic Carbene Metal Complexes

| Complex | Metal | Medicinal Activity | Key Properties & Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkynylgold(I) NHC (5f) | Au | Anticancer | High cellular uptake; 90% albumin binding; increased dipole moment enhances activity [17] |

| Silver-NHC complexes | Ag | Antimicrobial | MIC values 1.13-125 μg/mL; high stability (d/b ratios 7.8-12.68) [16] |

| Rhodium-NHC complexes | Rh | Anticancer | Activity against various cancer cell lines; potential for selective kinase inhibition [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Alkynylgold(I) NHC Complexes

Objective: Preparation of alkynylgold(I) NHC complexes 5a-5f and 6a/b as prospective anticancer agents [17].

Procedure:

- Synthesis of NHC Precursors: Prepare imidazolium or related azolium salts by alkylation of corresponding N-heterocycles [16].

- Generation of Silver-NHC Transfer Agents: React imidazolium salts with silver oxide in dichloromethane to form Ag-NHC complexes, which serve as transmetallation agents [16].

- Transmetallation to Gold: React Ag-NHC complexes with chloro(dimethylsulfide)gold(I) or similar gold precursors [17].

- Alkynyl Ligand Incorporation: Introduce alkynyl ligands (e.g., 4-fluoroethynylbenzene or mestranol derivatives) via metathesis or direct substitution reactions [17].

- Purification: Isolate products by precipitation or chromatography and characterize fully [17].

Characterization: Analyze by NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, elemental analysis, and X-ray crystallography. Perform DFT calculations to determine stability and dipole moments. Evaluate biological activity through cell viability assays (e.g., MTT) and cellular uptake studies [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents in Medicinal Organometallic Chemistry

| Reagent/Category | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| N-Heterocyclic Carbene Precursors | Imidazolium salts as NHC ligand precursors; tunable steric and electronic properties | 3-alkylthiomethyl-1-ethylimidazolium chlorides; 1,3-diazolidinium salts [16] |

| Sandwich Complex Precursors | Cyclic π-ligands for sandwich complex synthesis | KC9H9; K2C8H8; [LnI(COT)(thf)n] complexes [13] |

| Carbonyl Sources | CO ligands for metal carbonyl complexes | CO gas; potassium boranocarbonate; boranocarbonates as safe CO-releasing molecules [15] |

| Half-Sandwich Precursors | Organometallic dimers for piano-stool complexes | [M(arene)Cl2]2 (M = Ru, Rh, Ir); [Cp*MCl2]2 [14] |

| Stability Assessment Tools | Evaluate solution behavior and ligand exchange kinetics | DFT calculations; NMR speciation studies; electrochemical analysis [17] [11] |

Conceptual Framework and Future Directions

The strategic integration of organometallic motifs in drug design follows a logical progression from structural foundation to therapeutic application, as visualized below:

Diagram Title: Organometallic Drug Design Logic

Future research will focus on advanced delivery systems including ganglioside-functionalized nanoparticles for improved bioavailability and multidrug resistance selectivity [14]. The intersection of organometallic chemistry with nanotechnology promises enhanced drug absorption, controlled release, and reduced side effects through targeted delivery [12]. Additionally, the development of theranostic agents combining diagnostic and therapeutic functions represents a frontier in the field, particularly with radiolabeled organometallics for image-guided therapy [3] [15].

The transition from proto-organic to organometallic regimes continues to expand the chemical space available for drug discovery, offering innovative solutions to persistent challenges in medicinal chemistry through the unique properties of sandwich complexes, carbonyls, and carbenes.

The evolution of chemical science from its proto-organic roots to the modern organometallic regime represents a fundamental shift in how chemists understand, create, and utilize matter. At the heart of this transition lies the metal-carbon bond—a versatile linkage whose unique covalent character and electronic structures have enabled unprecedented control over molecular synthesis and design. The exploration of chemical space has progressed through three distinct historical regimes: a proto-organic period (pre-1860) characterized by uncertain year-to-year output of compounds, an organic regime (1861-1980) marked by regular production of carbon-hydrogen based molecules, and the current organometallic regime (1981-present) featuring renewed interest in metal-containing compounds with minimal annual variance in discovery rates [18] [19]. Throughout this progression, the metal-carbon bond has emerged as a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry, enabling breakthroughs across diverse fields from pharmaceutical development to materials science.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the bonding paradigm in organometallic chemistry, focusing specifically on the covalent character and electronic structures that govern metal-carbon bonding. By synthesizing fundamental principles with advanced theoretical frameworks and practical applications, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge tools necessary to harness these versatile interactions for innovative scientific discovery.

Fundamental Bonding Theories in Organometallic Chemistry

Covalent Bonding Fundamentals

Covalent bonding occurs when pairs of electrons are shared between atoms, allowing each atom to attain a stable electronic configuration [20] [21]. In traditional main-group chemistry, this typically follows the octet rule, where atoms achieve noble gas configurations through electron sharing. However, transition metal complexes exhibit expanded bonding possibilities due to the availability of d-orbitals, leading to more complex bonding paradigms [22].

The nature of covalent bonds depends significantly on the electronegativity differences between bonded atoms. When two identical nonmetals form covalent bonds (e.g., H-H), electrons are shared equally, creating nonpolar covalent bonds. In contrast, when atoms with different electronegativities form covalent bonds (e.g., H-Cl), unequal sharing results in polar covalent bonds [21]. Metal-carbon bonds typically fall between these extremes, exhibiting varying degrees of covalent character depending on the specific metal and its oxidation state.

Theoretical Framework for Organometallic Complexes

Theoretical organometallic chemistry employs a fragment-based approach to understand the electronic structure, geometrical preferences, and reactivity of complexes [23]. This methodology conceptually decomposes molecules into a metal fragment (MLₙ) and ligands, then reconstructs the molecule by examining orbital interactions between these components. This approach has been particularly valuable for understanding the bonding in diverse organometallic structures that have emerged in recent decades.

The molecular orbitals of these fragments form a conceptual library that allows researchers to predict bonding scenarios. The interaction between ligand orbitals (typically from organic molecules) and the orbitals of the MLₙ fragment determines the stability and properties of the resulting complex. This theoretical framework has proven essential for rationalizing and predicting the behavior of organometallic systems across various applications [23].

Electronic Structure and Electron Counting in Organometallic Complexes

The 18-Electron Rule

The 18-electron rule represents a fundamental principle in organometallic chemistry, describing the tendency of metal centers to achieve noble gas configurations (18 electrons) in their valence shells by utilizing one s, three p, and five d orbitals [22]. Complexes that satisfy this electron count are described as "electron-precise" or "saturated," with no empty low-lying orbitals available for additional ligand coordination. In contrast, complexes with fewer than 18 electrons are "unsaturated" and can electronically bind to additional ligands [22].

The applicability of the 18-electron rule depends heavily on ligand and metal characteristics. The rule is most consistently followed in complexes with strong-field ligands that are good σ-donors and π-acceptors (e.g., CO ligands) [22]. In these systems, the energy difference (Δ₀) between t₂g and eₐ* orbitals is large, making the t₂g orbitals bonding and the eₐ* orbitals strongly antibonding. This orbital arrangement favors 18-electron configurations.

Table 1: Common Exceptions to the 18-Electron Rule

| Exception Type | Electron Count | Typical Configurations | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16-Electron Complexes | 16 | d⁸ configuration | Rh(I), Ni(II), Pd(II), Pt(II) complexes |

| Bulky Ligand Systems | <18 | Variable | Complexes with agostic interactions |

| Strong π-Donor Ligands | <18 | Variable | Complexes with F⁻, O²⁻, RO⁻, RN²⁻ ligands |

| Early Transition Metals | <18 | High oxidation states | 4th/5th row metals with high oxidation states |

| Radical Species | Odd-electron | Various | Organometallic radicals |

Electron Counting Methodologies

Two primary methods exist for electron counting in organometallic complexes: the covalent method and the ionic method. Both approaches yield identical electron counts despite their different accounting systems [22] [24].

Covalent Method: In this approach, all metal-ligand bonds are considered covalent, with ligands treated as neutral entities. The steps include:

- Identifying the group number of the metal center

- Determining electrons contributed by ligands

- Accounting for the overall complex charge

- Adding electrons from metal-metal bonds (one per bond per metal)

- Summing contributions to obtain final electron count [22]

Ionic Method: This alternative approach assigns filled valences to ligands, often resulting in different formal charges than the covalent method. For example, a methyl group is treated as CH₃⁻ rather than a neutral radical [24]. The ionic method more directly provides oxidation state information but requires careful charge accounting.

Table 2: Electron Donation of Common Ligands in Organometallic Chemistry

| Ligand | Covalent Method Donation | Ionic Method Donation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 2 electrons | 2 electrons | Neutral ligand |

| NH₃ | 2 electrons | 2 electrons | Neutral ligand |

| Methyl (CH₃) | 1 electron | 2 electrons | Different formalisms |

| Hydride (H) | 1 electron | 2 electrons | Different formalisms |

| Chloride (Cl) | 1 electron | 2 electrons | Different formalisms |

| Cyclopentadienyl (C₅H₅) | 5 electrons | 6 electrons | Different formalisms |

| Ethylene (C₂H₄) | 2 electrons | 2 electrons | Neutral ligand |

Historical Evolution of Chemical Exploration

The Three Regimes of Chemical Discovery

Analysis of millions of reactions stored in the Reaxys database reveals that chemical discovery has progressed through three statistically distinguishable historical regimes [18]. This analysis examined 14,341,955 compounds associated with 16,356,012 reactions reported between 1800 and 2015, demonstrating an exponential growth in compound discovery with a remarkable 4.4% annual production rate that remained stable despite world wars and theoretical shifts [18] [19].

Proto-organic Regime (pre-1860): This period was characterized by high variability in year-to-year output of new compounds (σ = 0.4984), with an annual growth rate of 4.04% [18]. Metal-containing compounds represented a higher proportion of new molecules than in any subsequent period, though carbon- and hydrogen-based compounds still dominated. Chemical exploration primarily involved extraction and analysis of animal and plant products, alongside inorganic compounds [18].

Organic Regime (1861-1980): The adoption of valence and structural theories of chemistry around 1860 marked a transition to more regular discovery patterns (σ = 0.1251) with a higher annual growth rate of 4.57% [18] [19]. This period featured carbon- and hydrogen-containing compounds surpassing 90% of new discoveries by approximately 1880, with a corresponding decline in metal-containing compounds. The establishment of synthetic methodology as the primary means of compound discovery characterized this era.

Organometallic Regime (1981-present): The modern era has witnessed a revival in metal-containing compound discovery with exceptionally stable output (σ = 0.0450) though a reduced growth rate of 2.96% [18]. This regime reflects increased interest in organometallic compounds and their applications in catalysis, materials science, and pharmaceutical development. The period from 1995-2015 has seen a return to 4.40% annual growth, indicating renewed vigor in organometallic exploration [18].

Impact of Major Events on Chemical Discovery

The analysis of chemical discovery reveals notable impacts from global conflicts. Both World Wars caused significant disruptions in chemical output, with World War I (1914-1918) resulting in a -17.95% annual growth rate and World War II (1940-1945) showing a -6.00% rate [18]. Remarkably, the chemical community demonstrated resilience in both cases, with recovery to pre-war discovery rates within approximately five years after each conflict [18].

Metal-Carbon Bond Strength and the "Goldilocks Principle" in Catalysis

Quantitative Assessment of Metal-Carbon Bond Strength

The bond strength between metal catalysts and carbon substrates plays a crucial role in determining catalytic efficacy, particularly in processes like carbon nanotube (CNT) growth. First-principle density functional theory (DFT) calculations have established a "Goldilocks principle" for metal-carbon bonding, where optimal catalytic activity requires bond strength that is "just right" [25].

This principle establishes that metal-carbon bonds must be strong enough to facilitate dissociation of the catalytic metal particle from the carbon nanostructure (preventing deactivation) but not so strong that they favor the formation of stable metal carbides (which would also deactivate the catalyst) [25]. Bonds that are too weak cannot stabilize the growing hollow structure of materials like carbon nanotubes.

Table 3: Metal-Carbon Bond Strengths and Catalytic Activity for CNT Growth

| Metal | Adhesion Energy per Bond (eV) | Catalytic Activity | Primary Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe, Co, Ni | Moderate | Excellent | Covalent with moderate strength |

| Cu, Au, Ag | Weak | Poor | Physisorption/weak covalent |

| Mo, W | Strong | Poor (carbide formation) | Strong covalent/ionic |

| Y, Rh, Pd, Pt | Moderate | Good | Covalent with moderate strength |

| La, Ce | Moderate | Good | Covalent with moderate strength |

Bond Strength Optimization in Catalytic Systems

The Goldilocks principle for metal-carbon bonding has guided the development of advanced catalytic systems, particularly through metal alloying strategies. Combining metals with weak carbon bonding (e.g., Cu, Pd) with those exhibiting strong carbon bonding (e.g., Mo, W) has produced effective catalysts from components that are individually inactive for CNT growth [25]. This approach enables fine-tuning of metal-carbon bond strengths to achieve optimal catalytic performance.

For carbon nanotube growth specifically, effective catalysts must fulfill three key criteria: (i) decompose carbon feedstock gases, (ii) form graphitic caps at their surface, and (iii) maintain the CNT hollow structure by stabilizing the growing end through appropriate metal-carbon bond strength [25]. Criterion (iii) follows the Goldilocks principle and represents one of the key parameters determining successful CNT synthesis.

Experimental Methods and Analytical Techniques

Electrochemical Analysis of Organometallic Complexes

Electrochemical methods provide powerful tools for investigating the redox properties and electron transfer mechanisms of organometallic complexes. Voltammetry techniques, particularly cyclic voltammetry, enable controlled potential application to assess redox characteristics and electroactivity [26]. These methods are complemented by spectroelectrochemical (SEC) techniques that combine electrochemical manipulation with in situ spectroscopic monitoring.

Redox activity in organometallic complexes (LₙM–(CX)) can originate from three distinct sites: (I) the metal center (M), (II) the organometallic ligands (CX) bonded through metal-carbon bonds, or (III) potentially non-innocent co-ligands (Lₙ) [26]. This diversity creates various reactivity patterns, including unusual metal oxidation states, carbon-centered radicals, and ligand redox systems.

Electrochemical Synthesis Protocols

Electrochemical methods offer sustainable alternatives to conventional organometallic synthesis, replacing hazardous reagents with electrical energy and enabling in situ generation of unstable intermediates [26]. Key electrochemical synthesis protocols include:

Cathodic Reduction Methods: These techniques employ working electrodes as electron sources to reduce metal precursors and organic halides, facilitating metal-carbon bond formation. The method is particularly valuable for generating organometallic compounds with sensitive functional groups that might not survive conventional chemical reduction [26].

Anodic Oxidation Approaches: Utilizing working electrodes as electron sinks, these methods oxidize metal centers or organic substrates to create reactive intermediates for metal-carbon bond formation. This approach has proven effective for synthesizing metallocenes and related organometallic architectures [26].

Catalytic Electrosynthesis: This methodology combines electrochemical activation with catalytic cycles, enabling efficient carbonylation and C–H activation processes. These systems often operate under milder conditions than their purely chemical counterparts, enhancing functional group compatibility [26].

Carbonylation Methodologies

Carbon monoxide serves as a versatile C1 building block in organometallic chemistry, with bond dissociation energy of 1,072 kJ/mol—higher than that of nitrogen gas (942 kJ/mol) [27]. Modern carbonylation methodologies encompass three primary approaches:

Transition-Metal-Mediated Carbonylation: CO activation occurs through coordination to transition metal centers, enabling migratory insertion into metal-carbon bonds. Recent advances have focused on earth-abundant metal catalysts (Fe, Co, Ni), enhanced selectivity control, and carbonylation of inert bonds (C–F, C–O) [27].

Ionic Carbonylation: This pathway involves acyl cation or anion intermediates, traditionally requiring strong acids or bases. Recent innovations employing frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) have enabled milder reaction conditions and broader substrate scope [27].

Free-Radical Carbonylation: CO reacts with organic radicals to form acyl radicals, providing complementary reactivity to conventional methods. Photoredox catalysis has particularly advanced this approach by enabling gentler reaction conditions and improved functional group tolerance [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Organometallic Chemistry Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Precursors | Provide metal centers | Catalyst synthesis | Metal carbonyls, halides, acetates |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | C1 building block | Carbonylation reactions | High-pressure reactors often required |

| Ferrocene | Reference compound | Electrochemical studies | Internal standard for redox potentials |

| Cyclopentadienyl Compounds | Ligand precursors | Sandwich complex synthesis | Often generated in situ |

| Phosphine Ligands | Electron donation, steric control | Catalyst tuning | Significant impact on metal electronics |

| Organolithium/Boronic Reagents | Transmetalation agents | Cross-coupling reactions | Air- and moisture-sensitive |

| Electrochemical Cells | Reaction vessels | Electrosynthesis | Three-electrode systems common |

| DFT Computational Codes | Electronic structure modeling | Bonding analysis | VASP, TURBOMOLE commonly used |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Advanced Carbonylation Technologies

The carbonylation field continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping its trajectory. The development of more efficient catalytic systems capable of activating inert chemical bonds represents a high priority research direction [27]. Additionally, significant potential exists in exploring renewable CO sources and surrogates to enhance sustainability.

Integration of carbonylation with emerging technologies like photochemistry, flow chemistry, electrochemistry, and machine learning presents exciting prospects for scalable, efficient, and greener processes [27]. These interdisciplinary approaches are expected to drive the field forward, reinforcing carbonylation's central role in modern synthetic chemistry.

Electrochemical Advancements

Organometallic electrochemistry is increasingly focused on molecular electroactivation for bond functionalization. Key research directions include C–H and metal-metal bond activation in organometallic complexes, enabling new synthetic transformations and catalytic processes [26]. These developments are particularly valuable for direct functionalization of ubiquitous C–H bonds, offering more efficient and atom-economical approaches to complex molecules.

The combination of electrochemical techniques with spectroscopic and microscopic characterization methods continues to provide deeper insights into electron transfer mechanisms and structure-property relationships in organometallic systems [26]. These fundamental advances support the development of improved catalytic systems, functional materials, and electronic devices based on organometallic architectures.

The continued evolution of metal-carbon bonding paradigms promises to drive innovation across chemical sciences. As theoretical models refine and experimental techniques advance, researchers will gain increasingly sophisticated control over these fundamental interactions, enabling the design of next-generation catalysts, materials, and pharmaceutical agents. The organometallic regime, now in its fifth decade, continues to offer fertile ground for scientific discovery and technological innovation.

The history of organoarsenicals in medicine is a compelling narrative that underscores the paradoxical nature of arsenic—a potent poison that has been harnessed as a powerful therapeutic agent. Arsenicals represent one of the oldest known treatments for human diseases, with a documented legacy spanning over two millennia [28]. The very name "arsenic" derives from the Greek word "arsenikon," meaning "potent," reflecting its dual identity as both a toxin and a medicine [28]. This review examines the transition from proto-organic to organometallic regimes in chemical exploration research, focusing specifically on the journey of organoarsenicals from ancient empirical remedies to modern targeted antimicrobial therapies. The organoarsenical legacy provides a fascinating case study in drug development, illustrating how understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) and molecular mechanisms can transform a toxic element into a valuable chemotherapeutic agent [29].

The evolution of organoarsenicals reflects broader trends in medicinal chemistry, where the initial use of crude mineral preparations gradually gave way to purified synthetic compounds with refined therapeutic properties. This transition was marked by key discoveries in chemical synthesis, mechanistic understanding, and resistance mechanisms that collectively shaped the development of organometallic-based therapies. Today, with the escalating crisis of antibiotic resistance, there is renewed interest in revisiting arsenical compounds with proven efficacy to combat emerging pathogens, employing contemporary scientific approaches to design novel agents with improved therapeutic indices [28] [30].

Historical Development of Organoarsenicals

Ancient and Empirical Uses

The medicinal use of arsenic predates modern chemical understanding by centuries. Ancient Greek, Roman, Chinese, and Indian civilizations employed arsenic minerals for therapeutic purposes, establishing a foundation for later scientific development. Key historical figures and their contributions to arsenical medicine are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Arsenical Medicine

| Era/Date | Practitioner/Culture | Arsenical Compound | Medical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 460–377 BC | Hippocrates (Greek) | Orpiment (As₂S₃), Realgar (As₄S₄) | Escharotics for ulcers and abscesses [28] |

| 25–220 AD | Chinese (Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing) | Arsenic pills | Treatment of periodic fever [28] |

| 581–682 AD | Sun Si-Miao (Chinese) | Realgar, Orpiment, Arsenic Trioxide | Malaria treatment [28] |

| 1493–1541 AD | Paracelsus (Swiss) | Elemental arsenic | Early chemical therapeutics [28] |

| 1786 | Thomas Fowler (British) | Fowler's solution (1% potassium arsenite) | Malaria, remittent fevers, headaches [28] |

| 1900s | Paul Ehrlich & Alfred Bertheim | Arsphenamine (Salvarsan) | Syphilis treatment [29] |

The empirical use of arsenicals established their potential therapeutic value while simultaneously revealing their narrow therapeutic window. The principle articulated by Paracelsus that "the dosage makes the difference between a drug and a poison" perfectly captures the challenge faced by early practitioners of arsenical therapy [28]. This historical foundation set the stage for the more systematic chemical investigations that would follow in the modern era.

The Transition to Organometallic Regimes

The early 20th century marked a critical transition from inorganic arsenicals to organoarsenicals, representing a fundamental shift from proto-organic to truly organometallic therapeutic regimes. Paul Ehrlich and Alfred Bertheim conducted pioneering structure-activity relationship studies seeking safer alternatives to aminophenyl arsenic acid (Atoxyl) for treating African sleeping sickness [29]. Their work exemplified the systematic approach of modern medicinal chemistry, methodically modifying chemical structures to optimize therapeutic properties while minimizing toxicity.

This research culminated in the development of arsphenamine (Salvarsan) in 1907, which became the first synthetic chemotherapeutic agent and a landmark in the history of medicine [29]. Salvarsan represented a prototypical organoarsenical with direct arsenic-carbon bonds, distinguishing it from earlier inorganic preparations. Ehrlich's methodical approach established foundational principles for drug development, including the concept of "magic bullets" that could selectively target pathogens without harming the host. The evolution from inorganic to organic arsenicals marked a paradigm shift in chemical therapeutics, demonstrating that deliberate molecular design could yield compounds with superior pharmacological profiles compared to naturally occurring minerals.

Modern Organoarsenicals: Mechanisms and Applications

Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Action

Contemporary research has elucidated specific molecular mechanisms through which organoarsenicals exert antimicrobial effects, moving beyond empirical observations to precise mechanistic understanding.

Inhibition of Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis

Recent studies have identified MurA, a critical enzyme in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis, as a key target of trivalent organoarsenicals [31]. MurA catalyzes the first committed step in peptidoglycan synthesis, transferring enolpyruvate from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) [31]. This pathway is essential for bacterial cell wall formation and represents an attractive target for antimicrobial development.

Methylarsenite (MAs(III)) specifically inhibits MurA activity, thereby disrupting cell wall synthesis and exerting potent antibacterial effects [31]. Importantly, this inhibition is selective for organoarsenicals, as inorganic arsenite (As(III)) does not significantly affect MurA function [31]. The mechanism of MurA inhibition by MAs(III) differs from that of the phosphonate antibiotic fosfomycin, as demonstrated by mutagenesis studies showing that a C117D MurA mutant retains sensitivity to MAs(III) while becoming resistant to fosfomycin [31]. This distinction suggests that organoarsenicals represent a novel structural class for inhibiting peptidoglycan biosynthesis.

Evolutionary Perspective on Arsenical Warfare

The antimicrobial properties of organoarsenicals can be understood within an evolutionary framework of microbial warfare. The enzyme ArsM (bacterial As(III) S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase), which methylates inorganic As(III) into highly toxic MAs(III) and dimethylarsenite (DMAs(III)), is evolutionarily ancient, dating back approximately 3.5 billion years [32]. This suggests that microbes developed the capacity to weaponize arsenic as a competitive strategy early in evolutionary history [32].

In contemporary microbial communities, biogenic MAs(III) exhibits significant antimicrobial activity, functioning as a natural antibiotic that provides competitive advantages to producing organisms [32]. This evolutionary perspective contextualizes organoarsenicals not merely as synthetic therapeutic agents but as adaptations of natural chemical warfare mechanisms that have evolved over geological timescales.

Experimentation and Protocol

Key Experimental Methodologies

Research on organoarsenical mechanisms employs well-established microbiological and biochemical approaches. The following experimental workflow (Figure 1) outlines a standard protocol for investigating organoarsenical activity and resistance mechanisms:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Identifying Organoarsenical Targets

Critical to these investigations is the preparation of trivalent organoarsenicals. For in vivo assays, methylarsenate (MAs(V)) is reduced to MAs(III) using a solution containing Na₂S₂O₃, Na₂S₂O₅, and H₂SO₄, followed by pH adjustment to 6 with NaOH [31]. For in vitro enzymatic studies, methylarsonous acid iodide (MAs(III)I₂) is synthesized to avoid interference from reduction reagents that can compromise enzyme activity [31].

Bacterial growth and resistance assays typically utilize lysogeny broth (LB) or 2x ST medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, with incubation at 30°C or 37°C under aerobic conditions [31]. Antimicrobial susceptibility is evaluated using standard methods such as the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion assay and determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Organoarsenical Research

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| MAs(III) (Methylarsenite) | Synthesized from MAs(V) reduction or as MAs(III)I₂ | Primary antimicrobial compound for mechanistic studies [31] |

| S. putrefaciens 200 | Environmental Gram-negative bacterium | Source of genomic DNA for resistance gene identification [31] |

| E. coli TOP10 | F- mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG | Host for genomic library construction and resistance screening [31] |

| E. coli BL21 | fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal (λ DE3) [dcm] ΔhsdS λ DE3 = λ sBamHIo ΔEcoRI-B int::(lacI::PlacUV5::T7 gene1) i21 Δnin5 | Protein expression host for MurA purification [31] |

| pUC118 Vector | Cloning vector with HindIII site | Library construction and gene expression [31] |

| pET26b Vector | Expression vector with T7 promoter | Recombinant protein expression [31] |

| HindIII | Restriction endonuclease | Genomic DNA fragmentation for library construction [31] |

| Fosfomycin | Phosphonate antibiotic | Control inhibitor for MurA comparison studies [31] |

Resistance Mechanisms and Microbial Adaptation

Molecular Basis of Resistance

The efficacy of organoarsenicals as antimicrobial agents has driven the evolution of sophisticated resistance mechanisms in microorganisms. These adaptive responses illustrate the dynamic interplay between therapeutic compounds and microbial survival strategies.

The primary resistance mechanisms include:

Enzyme Overexpression: Amplification of target enzymes such as MurA can confer resistance to MAs(III), as demonstrated by the selection of MAs(III)-resistant clones expressing MurA from genomic libraries [31].

Efflux Systems: Specialized transport proteins such as ArsP facilitate the active extrusion of MAs(III) from bacterial cells, reducing intracellular concentrations to subtoxic levels [31] [32].

Detoxification Enzymes: Enzymes including ArsH oxidase MAs(III) to less toxic MAs(V), while ArsI dioxygenase cleaves the carbon-arsenic bond, demethylating MAs(III) to less toxic As(III) [31].

Transcriptional Reprograming: Exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of heavy metals like arsenic and copper upregulates multidrug efflux pumps (acrB, mdtA, tolC), global regulators (marA, soxS, baeS), and metal-detoxification operons (ars, cop), contributing to cross-resistance to antibiotics [33].

These resistance mechanisms highlight the remarkable adaptability of microorganisms and the challenges in maintaining therapeutic efficacy against evolving pathogens.

Co-resistance and Cross-resistance Dynamics

The interaction between heavy metals and antibiotics represents a significant concern in antimicrobial therapy. Studies with enteric pathogens from poultry have demonstrated that co-exposure to heavy metals like arsenic and antibiotics enhances resistance and promotes transcriptional adaptation [33]. Pre-exposure to AsO₄³⁻ and Cu²⁺ significantly reduces zones of inhibition for multiple antibiotics including ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, meropenem, imipenem, and tetracycline [33]. Furthermore, prolonged exposure to AsO₄³⁻ or Cu²⁺ increases the MIC of tetracycline by approximately 60%, accompanied by transcriptional upregulation of resistance determinants [33].

These findings illustrate the complex co-selection dynamics in environmental and clinical settings, where metal exposure can inadvertently promote antibiotic resistance through shared mechanisms such as efflux pump activation and stress response pathways.

Contemporary Applications and Future Directions

Renaissance in Infectious Disease Therapeutics

After a period of declining use following the discovery of conventional antibiotics in the 1940s, organoarsenicals are experiencing renewed interest due to the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance [28]. The identification of novel organoarsenicals with potent antibacterial properties represents a promising frontier in the search for effective antimicrobial agents.

A significant recent development is the discovery of arsinothricin (AST), a naturally occurring organoarsenical antibiotic produced by soil bacteria [30]. AST is a non-proteinogenic analog of glutamate that inhibits glutamine synthetase, exhibiting broad-spectrum activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant pathogens [30]. The biosynthetic pathway for AST involves a relatively simple three-gene cluster (arsQML), in contrast to the more than 20 genes required for the synthesis of its phosphonate counterpart, phosphinothricin [30].

Table 3: Modern Organoarsenical Antimicrobial Agents

| Compound | Chemical Characteristics | Mechanism of Action | Spectrum of Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsinothricin (AST) | 2-amino-4-(hydroxymethylarsinoyl) butanoate | Glutamine synthetase inhibition [30] | Broad-spectrum vs. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant pathogens [30] |

| Hydroxyarsinothricin (AST-OH) | 2-amino-4-(dihydroxyarsinoyl) butanoate | Glutamine synthetase inhibition (precursor to AST) [30] | Antimicrobial activity prior to methylation [30] |

| Methylarsenite (MAs(III)) | CH₃As(OH)₂ | Inhibition of MurA in peptidoglycan biosynthesis [31] | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial [32] |

Strategic Integration in Therapeutic Development

The future development of organoarsenicals as antimicrobial agents will likely focus on several key strategies:

Rational Drug Design: Leveraging structural biology and computational approaches to design novel organoarsenicals with enhanced target specificity and reduced off-target effects.

Combination Therapies: Employing organoarsenicals in conjunction with conventional antibiotics to overcome resistance and enhance efficacy through synergistic mechanisms [28].

Pathogen-Specific Targeting: Developing organoarsenicals that selectively target pathogenic species while preserving commensal microbiota, potentially through exploitation of species-specific metabolic pathways.

Delivery System Optimization: Designing advanced formulation strategies that maximize therapeutic index by improving bioavailability while minimizing systemic exposure.

The unique properties of organoarsenicals, including their distinct mechanisms of action and the relative unfamiliarity of these targets to bacterial resistance systems, position them as valuable assets in the ongoing struggle against antimicrobial resistance.

The legacy of organoarsenicals in antimicrobial therapy represents a remarkable journey from ancient empirical remedies to modern targeted therapeutics. This evolution exemplifies the broader transition from proto-organic to organometallic regimes in chemical exploration research, highlighting how systematic investigation of structure-activity relationships and mechanistic insights can transform toxic elements into valuable therapeutic agents. The continued exploration of organoarsenicals, informed by both historical wisdom and contemporary scientific innovation, offers promising avenues for addressing the pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance. As this field advances, the integration of evolutionary perspectives, mechanistic understanding, and strategic drug design will likely yield new generations of organoarsenical antimicrobials with enhanced efficacy and safety profiles.

Mechanisms and Medicine: Catalytic and Therapeutic Applications in Drug Development

Organometallic chemistry, the study of compounds containing metal-carbon bonds, represents a fundamental transition from proto-organic to advanced synthetic regimes in chemical exploration research. These reactions enable transformations impossible with traditional organic chemistry alone, serving as crucial tools for constructing complex molecular architectures in pharmaceutical development, materials science, and industrial chemical synthesis [34] [35]. The importance of this subfield is evidenced by multiple Nobel Prizes awarded for organometallic catalysis, underscoring its transformative role in chemical synthesis [34]. This technical guide examines three cornerstone mechanisms—oxidative addition, reductive elimination, and migratory insertion—that form the foundational framework upon which sophisticated catalytic cycles are built, providing researchers with mechanistic understanding essential for innovation in drug development and beyond.

Core Principles and Definitions

Organometallic reactions can be systematically classified into two primary categories: those involving gain or loss of ligands and those involving modification of existing ligands [36]. The reactions explored in this guide span both categories, with oxidative addition and reductive elimination belonging to the former, and migratory insertion representing the latter. Understanding these processes requires familiarity with key concepts including oxidation state (the formal charge on a metal center if all ligands were removed along with their electron pairs), coordination number (the number of atoms directly bonded to the metal center), and electron count (the total number of valence electrons surrounding the metal) [34].

The movement of electrons during these transformations is denoted using curved arrow notation, where a full-headed arrow indicates the shift of an electron pair, crucial for tracking electronic reorganization during two-electron processes characteristic of these mechanisms [37]. These reactions typically occur at transition metal centers, which provide suitable orbitals for bonding changes and oxidation state variations, with their d-electron configuration significantly influencing reactivity patterns [36] [35].

Oxidative Addition

Mechanism and Characteristics

Oxidative addition is a fundamental organometallic reaction wherein a covalent single bond (A-B) is cleaved, with both resulting fragments (A and B) forming new bonds to a metal center [36] [34]. This process simultaneously increases the metal's oxidation state by two units and its coordination number by two [34]. The reaction can proceed through multiple pathways, including concerted, SN2, and radical mechanisms, depending on the substrate and metal complex involved [35].

The reaction can occur in different spatial arrangements: cis-addition places the two newly added ligands adjacent to each other, while trans-addition positions them opposite one another in the coordination sphere [36]. Additionally, oxidative additions can be classified as mononuclear (occurring at a single metal center) or dinuclear (cleaving a metal-metal bond and adding one ligand to each fragment) [36].

Experimental Manifestations and Examples

A quintessential example of mononuclear cis-addition involves the reaction of dihydrogen (H₂) with a square planar iridium(I) complex. The H-H bond cleaves homolytically, forming an octahedral iridium(III) dihydride complex with two hydrido ligands in cis orientation [36]. Steric factors typically favor the cis product when small ligands like hydride are involved [36].

A representative trans-addition example features methyl bromide (CH₃Br) adding to an iridium complex, resulting in methyl and bromo ligands in trans positions [36]. Dinuclear oxidative addition is exemplified by the reaction of dihydrogen with dicobalt octacarbonyl (Co₂(CO)₈), which cleaves the Co-Co bond and produces two molecules of hydridocobalt tetracarbonyl (HCo(CO)₄) [36].

Table 1: Quantitative Changes in Oxidative Addition

| Parameter | Initial State | Final State | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation State | +1 (Ir) | +3 (Ir) | +2 [36] |

| Coordination Number | 4 | 6 | +2 [36] |

| Total Valence Electrons | 16 | 18 | +2 [34] |

| Metal Geometry | Square planar | Octahedral | - |

Experimental Protocol for Oxidative Addition

Objective: To demonstrate oxidative addition of methyl iodide to iridium(I) complex.

Materials:

- Vaska's complex (IrCl(CO)(PPh₃)₂)

- Anhydrous methyl iodide

- Toluene (degassed)

- Schlenk line for inert atmosphere operations

- NMR tube with J. Young valve

Procedure:

- Prepare an NMR sample of 10 mg IrCl(CO)(PPh₃)₂ in 0.6 mL deuterated toluene in a J. Young valve NMR tube.

- Record initial ³¹P NMR spectrum (singlet at ~25 ppm).

- Add 5 molar equivalents of methyl iodide via microsyringe under inert atmosphere.

- Monitor reaction progress by ³¹P NMR spectroscopy.