From Theory to Therapy: The Historical Development of Computational Chemistry (1800-2015)

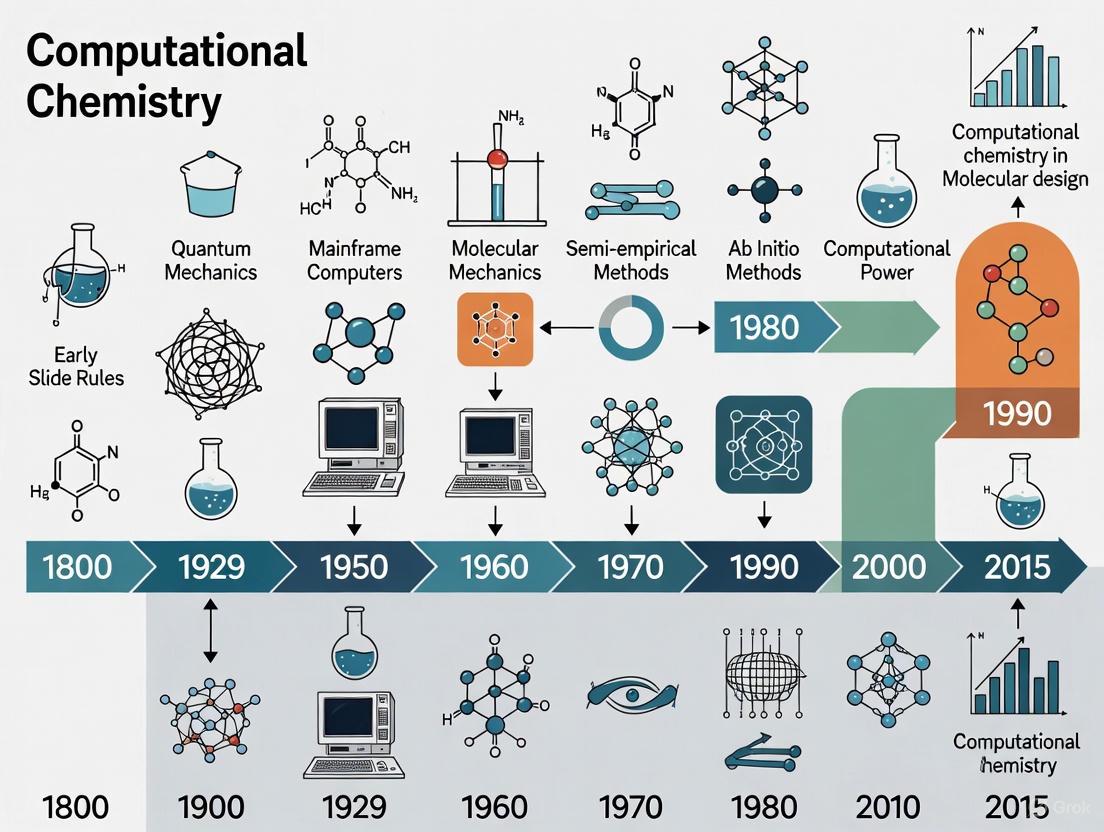

This article traces the transformative journey of computational chemistry from its 19th-century theoretical foundations to its modern status as an indispensable tool in scientific research and drug development.

From Theory to Therapy: The Historical Development of Computational Chemistry (1800-2015)

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of computational chemistry from its 19th-century theoretical foundations to its modern status as an indispensable tool in scientific research and drug development. It details the pivotal shift from a purely experimental science to one empowered by computer simulation, covering the inception of quantum mechanical theories, the birth of practical computational methods in the mid-20th century, and the rise of Nobel Prize-winning methodologies like Density-Functional Theory and multiscale modeling. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content explores key methodological advancements, persistent challenges in accuracy and scalability, the critical role of validation against experimental data, and the field's profound impact on rational drug design and materials science. By synthesizing historical milestones with current applications, this review provides a comprehensive resource for understanding how computational chemistry has reshaped the modern scientific landscape.

The Precursors to Computation: Laying the Theoretical Groundwork (1800-1940s)

This whitepaper examines the 19th-century Chemical Revolution through the dual lenses of atomic theory development and the systematic expansion of chemical space. By analyzing quantitative data on compound discovery from 1800-2015, we identify three distinct historical regimes in chemical exploration characterized by fundamental shifts in theoretical frameworks and experimental practices. The emergence of atomic theory provided the foundational paradigm that enabled structured navigation of chemical possibility, establishing principles that would later inform computational chemistry approaches. This historical analysis provides context for understanding the evolution of modern chemical research methodologies, particularly in pharmaceutical development where predictive molecular design is paramount.

The Chemical Revolution, traditionally dated to the late 18th century, represents a fundamental transformation in chemical theory and practice that established the modern science of chemistry [1]. While often associated primarily with Antoine Lavoisier's oxygen theory of combustion and his systematic approach to chemical nomenclature, this revolution extended well into the 19th century through the development and acceptance of atomic theory [1] [2]. The chemical revolution involved the rejection of phlogiston-based explanations of chemical phenomena in favor of empirical, quantitative approaches centered on the law of conservation of mass and the composition of compounds [2].

This period established the foundational principles that would eventually enable the emergence of computational chemistry centuries later. The systematic classification of elements and compounds, coupled with growing understanding of combination rules and reaction patterns, created the conceptual framework necessary for mathematical modeling of chemical systems [3]. Historical analysis reveals that the exploration of chemical space—the set of all possible molecules—has followed distinct, statistically identifiable regimes from the early 19th century to the present, with the 19th century establishing the essential patterns for subsequent chemical discovery [4].

Quantitative Analysis of Chemical Space Expansion

Analysis of millions of chemical reactions documented in the Reaxys database reveals clear patterns in the exploration of chemical space from 1800 to 2015 [4]. The annual number of new compounds reported grew exponentially at a stable 4.4% annual rate throughout this period, demonstrating remarkable consistency in the expansion of chemical knowledge despite major theoretical shifts and historical disruptions [4] [5].

Three Historical Regimes of Chemical Discovery

Statistical analysis identifies three distinct regimes in the exploration of chemical space, characterized by different growth rates and variability in annual compound output [4]:

Table 1: Historical Regimes in Chemical Space Exploration

| Regime | Period | Annual Growth Rate (μ) | Standard Variation (σ) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-organic | Before 1861 | 4.04% | 0.4984 | High variability in year-to-year output; mix of organic, inorganic, and metal-containing compounds |

| Organic | 1861–1980 | 4.57% | 0.1251 | More regular production dominated by carbon- and hydrogen-containing compounds (>90% after 1880) |

| Organometallic | 1981–2015 | 2.96% | 0.0450 | Revival of metal-containing compounds; most stable output variability |

The transition between these regimes corresponds to major theoretical developments in chemistry. The shift from the proto-organic to organic regime around 1860 aligns with the widespread adoption of valence and structural theories, which enabled more systematic and predictable chemical exploration [4] [5]. This transition marks a movement from exploratory investigation to guided search within chemical space.

Impact of Major Historical Events

Analysis of the chemical discovery data reveals how major historical events affected the pace of chemical exploration [4]:

Table 2: Impact of World Wars on Chemical Discovery

| Period | Annual Growth Rate | Contextual Factors |

|---|---|---|

| 1914–1918 (WWI) | -17.95% | Significant disruption to chemical research |

| 1919–1924 (Post-WWI) | 18.98% | Rapid recovery and catch-up in chemical discovery |

| 1940–1945 (WWII) | -6.00% | Moderate disruption, less severe than WWI |

| 1946–1959 (Post-WWII) | 12.11% | Sustained recovery and expansion |

Remarkably, the long-term exponential growth trend continued despite these major disruptions, with the system returning to its baseline growth trajectory within approximately five years after each war [4] [5]. This resilience demonstrates the robustness of the chemical research enterprise once established patterns of investigation became institutionalized.

Foundations of Atomic Theory and Molecular Structure

The development of atomic theory provided the conceptual framework necessary for structured exploration of chemical space. John Dalton's atomic theory, introduced in the early 19th century, established several fundamental postulates that would guide chemical research for centuries [6] [7]:

- Elemental Atomic Uniqueness: Atoms of each element are identical in mass and properties and differ from atoms of all other elements [6]

- Compound Formation: Compounds form through the combination of atoms of different elements in fixed, small whole-number ratios [6] [7]

- Conservation in Reactions: Atoms are neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions, only rearranged [6]

Dalton's theory provided a physical explanation for the Law of Multiple Proportions, which states that when two elements form more than one compound, the masses of one element that combine with a fixed mass of the other are in a ratio of small whole numbers [7]. This mathematical relationship between elements in compounds became a powerful predictive tool for exploring chemical space.

Experimental Foundations of Atomic Theory

Dalton's methodological approach established patterns for chemical investigation that would influence both experimental and later computational approaches:

Diagram 1: Dalton's Methodology for Atomic Theory Development

Dalton's experimental approach involved precise gravimetric measurements of elements combining to form compounds [7]. Despite limitations in his experimental technique and some incorrect molecular assignments (such as assuming water was HO rather than H₂O), his foundational insight that elements combine in fixed proportions provided the basis for calculating relative atomic masses and predicting new chemical combinations [7].

Experimental Protocols in 19th-Century Chemistry

Lavoisier's Combustion Experiments

Antoine Lavoisier's experimental work established new standards for precision measurement in chemistry and provided the empirical foundation for overturning phlogiston theory [1]:

Objective: Demonstrate that combustion involves combination with atmospheric components rather than release of phlogiston [1] [2]

Methodology:

- Precision Gravimetry: Conduct careful weighing of reactants and products before and after reactions using precision balances [1]

- Closed System Design: Utilize sealed apparatus to prevent mass loss or gain from the environment [1]

- Mercury Calx Experiment: Heat mercury in a sealed container to form mercury calx (oxide), noting the decreased air volume and increased solid mass [1]

- Gas Identification: Collect and characterize gases produced during reactions, identifying oxygen's role in combustion and respiration [1]

- Instrumentation: Employ thermometric and barometric measurements; collaborate in developing the calorimeter for heat measurement [1]

Key Reagents and Materials:

Table 3: Key Research Reagents in 19th Century Chemical Revolution

| Reagent/Material | Chemical Formula | Primary Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury (Hg) | Hg | Primary material in calx experiments demonstrating oxygen combination |

| Mercury Calx | HgO | Mercury oxide used to isolate oxygen upon decomposition |

| Oxygen | O₂ | Isolated and identified as the active component in air supporting combustion |

| Hydrogen | H₂ | Studied in combination reactions; used in water formation experiments |

| Water | H₂O | Decomposed and synthesized to demonstrate compound nature |

| Precision Balance | - | Gravimetric measurement for conservation of mass demonstrations |

| Calorimeter | - | Instrument for measuring heat changes in chemical reactions |

Dalton's Atomic Weight Determinations

Objective: Establish relative weights of "ultimate particles" of elements through quantitative analysis of compound composition [7]

Methodology:

- Compound Selection: Identify binary compounds containing elements in simple combinations [7]

- Composition Analysis: Determine mass proportions of elements in compounds through decomposition or synthesis [7]

- Reference Standard: Establish hydrogen as reference atom with mass of 1 unit [7]

- Ratio Calculation: Compute relative masses of other elements based on combination ratios [7]

- Multiple Compound Analysis: Examine series of compounds containing the same elements to identify simple whole-number ratios [7]

Key Insight: The consistent appearance of small whole-number ratios in compound compositions provided primary evidence for discrete atomic combination [6] [7].

Theoretical Framework and Its Evolution

The 19th century witnessed the transition from phenomenological chemistry to theoretical frameworks with predictive capability. This evolution is visualized in the following conceptual map:

Diagram 2: Theoretical Evolution in 19th Century Chemistry

The Phlogiston to Oxygen Transition

The chemical revolution began with the rejection of phlogiston theory, which posited that combustible materials contained a fire-like element called phlogiston that was released during burning [2]. Lavoisier's systematic experiments demonstrated that combustion actually involved combination with oxygen, leading to the oxygen theory of combustion [1] [2]. This theoretical shift was significant because it replaced a qualitative, principle-based explanation with a quantitative, substance-based model that enabled precise predictions [2].

Structural Theory and Its Impact

The adoption of structural theory in the mid-19th century, including Kekulé's assignment of the cyclic structure to benzene and the development of valence theory, marked a critical turning point in chemical exploration [8]. This theoretical advancement enabled chemists to visualize molecular architecture and understand the spatial arrangement of atoms, dramatically increasing the efficiency of chemical synthesis and discovery [4]. The effect is visible in the quantitative data as a sharp reduction in the variability of annual compound output around 1860, indicating a transition from exploratory investigation to guided search within chemical space [4].

Bridge to Computational Chemistry

The theoretical and methodological foundations established during the 19th-century Chemical Revolution created the essential framework for the eventual development of computational chemistry in the 20th century [3]. The key connections include:

From Atomic Weights to Quantum Calculations

Dalton's relative atomic weights provided the first quantitative parameters for chemical prediction, establishing a tradition of numerical characterization that would evolve through Mendeleev's periodic law to modern quantum chemical calculations [7] [3]. The 20th century saw the implementation of these principles in computational methods:

- Early Computational Methods (1950s-1960s): The first semi-empirical atomic orbital calculations and ab initio Hartree-Fock methods applied quantum mechanics to molecular systems [3]

- Density Functional Theory (1960s-): Walter Kohn's development of density-functional theory demonstrated that molecular properties could be determined from electron density rather than wave functions [3] [9]

- Computational Software (1970s-): John Pople's development of the Gaussian program enabled practical quantum mechanical calculations for complex molecular systems [3] [9]

From Chemical Synthesis to Molecular Modeling

The 19th-century practice of systematic compound synthesis and characterization established the experimental data that would later train computational models [4] [3]. The exponential growth in characterized compounds documented in Reaxys and other chemical databases provides the essential reference data for validating computational chemistry predictions [4] [3].

Modern computational chemistry applies these historical principles to drug design and materials science, using quantum mechanical simulations to predict molecular behavior before synthesis [3] [9]. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Levitt, Karplus, and Warshel for developing multiscale models of complex chemical systems represents the direct descendant of the methodological traditions established during the Chemical Revolution [9].

The 19th-century Chemical Revolution established the conceptual and methodological foundations that enabled the systematic exploration of chemical space. Through the development of atomic theory, structural understanding, and quantitative experimental approaches, chemists created a framework for navigating chemical possibility that would eventually evolve into computational chemistry. The exponential growth in chemical discovery documented from 1800 to 2015 demonstrates the remarkable productivity of this paradigm, while the identification of distinct historical regimes reveals how theoretical advances dramatically reshape research efficiency. For contemporary researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding this historical trajectory provides essential context for current computational approaches that build upon centuries of chemical investigation. The principles established during the Chemical Revolution continue to inform modern computational methodologies, creating an unbroken chain of chemical reasoning from Dalton's atomic weights to contemporary quantum simulations.

The period from 1800 to 2015 witnessed chemistry's transformation from an observational science to a predictive, computational discipline. This shift became possible only after theorists provided a mathematical description of matter at the quantum level. The pivotal breakthrough came in 1926, when Erwin Schrödinger published his famous wave equation, creating a mathematical foundation for describing the behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules [10] [11]. This equation, now fundamental to quantum mechanics, gave chemists an unprecedented tool: the ability to calculate molecular properties from first principles rather than relying solely on experimental measurement [10] [3].

Schrödinger's equation is the quantum counterpart to Newton's second law in classical mechanics, predicting the evolution over time of the wave function (Ψ), which contains all information about a quantum system [10]. The discovery that electrons could be described as waves with specific probability distributions meant that chemists could now computationally model atomic structure and chemical bonding [11]. This quantum leap created the foundation for computational chemistry, a field that uses computer simulations to solve chemical problems that are often intractable through experimental methods alone [3]. The subsequent development of computational chemistry represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in the history of chemical research, enabling scientists to explore chemical space—the totality of possible molecules—through simulation rather than solely through laboratory synthesis [5] [4].

Historical Backdrop: Chemical Discovery from 1800-2015

The exponential growth of chemical knowledge from 1800 to 2015 provides crucial context for understanding Schrödinger's revolutionary impact. Analysis of millions of compounds recorded in chemical databases reveals distinct eras of chemical discovery, each characterized by different approaches and theoretical understandings [4].

Table 1: Historical Regimes in Chemical Discovery (1800-2015)

| Regime | Time Period | Annual Growth Rate | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-organic | 1800-1860 | 4.04% | High variability in annual compound discovery; mix of organic and metal-containing compounds; early synthetic chemistry |

| Organic | 1861-1980 | 4.57% | More regular discovery pace; carbon- and hydrogen-containing compounds dominated (>90% after 1880); structural theory guided synthesis |

| Organometallic | 1981-2015 | 2.96%-4.40% | Most consistent discovery rate; revival of metal-containing compounds; computational methods increasingly important |

Analysis of the Reaxys database containing over 14 million compounds reported between 1800 and 2015 demonstrates that chemical discovery grew at a remarkable 4.4% annual rate over this 215-year period [5] [4]. This exponential growth was surprisingly resilient, continuing through World Wars despite temporary dips, with recovery to pre-war discovery rates within five years after each conflict [4]. What changed fundamentally with Schrödinger's contribution was not the pace of discovery, but the methodology—providing a theoretical framework that would eventually enable predictive computational chemistry rather than purely empirical approaches.

The Schrödinger Equation: Mathematical Foundation

Core Theoretical Principles

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a quantum-mechanical system [10]. Its time-dependent form is:

iℏ(∂/∂t)|Ψ(t)⟩ = Ĥ|Ψ(t)⟩

where i is the imaginary unit, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, |Ψ(t)⟩ is the quantum state vector (wave function) of the system, and Ĥ is the Hamiltonian operator corresponding to the total energy of the system [10]. For many practical applications in chemistry, the time-independent form is used:

Ĥ|Ψ⟩ = E|Ψ⟩

where E is the energy eigenvalue corresponding to the stationary state |Ψ⟩ [10]. Solving this eigenvalue equation provides both the wave function, which describes the probability distribution of electrons, and the associated energy levels of the system [12].

The Hamiltonian operator consists of two fundamental components: the kinetic energy of all particles in the system and the potential energy arising from their interactions [12]. For chemical systems, this typically includes electron kinetic energy, electron-nucleus attraction, and electron-electron repulsion. The complexity of solving the Schrödinger equation increases dramatically with the number of particles in the system, giving rise to the many-body problem that necessitates computational approaches for all but the simplest chemical systems [3].

From Equation to Atomic Model

Schrödinger's critical innovation was applying wave equations to describe electron behavior in atoms, representing a radical departure from previous planetary models of the atom [11]. His model assumed the electron behaves as a wave and described regions in space (orbitals) where electrons are most likely to be found [11]. Unlike Niels Bohr's earlier one-dimensional model that used a single quantum number, Schrödinger's three-dimensional model required three quantum numbers to describe atomic orbitals: the principal (n), angular (l), and magnetic (m) quantum numbers, which describe orbital size, shape, and orientation [11].

This wave-mechanical approach fundamentally changed how chemists conceptualized electrons—abandoning deterministic trajectories for probabilistic distributions [11]. The Schrödinger model no longer told chemists precisely where an electron was at any moment, but rather where it was most likely to be found, represented mathematically by the square of the wave function |Ψ|² [13] [11]. This probabilistic interpretation formed the crucial link between abstract mathematics and chemically meaningful concepts like atomic structure and bonding.

The Computational Framework: From Equation to Application

Implementing the Schrödinger Equation in Chemistry

Applying the Schrödinger equation to chemical systems involves constructing an appropriate Hamiltonian operator for the system of interest, then solving for the wave functions and corresponding energies [12]. The process follows a systematic methodology:

The Hamiltonian operator (Ĥ) is built from the kinetic energy of all particles (electrons and nuclei) and the potential energy of their interactions (electron-electron repulsion, electron-nucleus attraction, and nucleus-nucleus repulsion) [12]. For a molecular system, this becomes extraordinarily complex due to the many interacting particles, necessitating the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motion based on their mass difference [13]. This approximation simplifies the problem by treating nuclei as fixed while solving for electron distribution, making computational solutions feasible [13].

Computational Methodologies and Approximations

As computational chemistry evolved, distinct methodological approaches emerged to solve the Schrödinger equation with varying balances of accuracy and computational cost:

Table 2: Computational Chemistry Methods for Solving the Schrödinger Equation

| Method Class | Key Approximations | Accuracy vs. Cost | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio | No empirical parameters; begins directly from theoretical principles | High accuracy, high computational cost | Small to medium molecules; benchmark calculations |

| Hartree-Fock | Approximates electron-electron repulsion with average field | Moderate accuracy, high cost for large systems | Basis for post-Hartree-Fock methods |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density rather than wave function | Good accuracy with reasonable cost | Large molecules; solids and surfaces |

| Semi-empirical | Incorporates empirical parameters to simplify calculations | Lower accuracy, lower cost | Very large systems; initial screening |

The Hartree-Fock method represents a fundamental approach that approximates the many-electron wave function as a Slater determinant of single-electron orbitals [3]. While it provides a starting point for more accurate calculations, its neglect of electron correlation (the instantaneous repulsion between electrons) limits its accuracy [3]. Post-Hartree-Fock methods like configuration interaction, coupled cluster theory, and perturbation theory introduce electron correlation corrections, improving accuracy at increased computational expense [3].

The development of Density Functional Theory (DFT) provided a revolutionary alternative by using electron density rather than wave functions as the fundamental variable, significantly reducing computational complexity while maintaining good accuracy for many chemical applications [3]. This breakthrough, for which Walter Kohn received the Nobel Prize in 1998, made calculations on larger molecules practically feasible and became one of the most widely used methods in computational chemistry [3].

Modern computational chemistry relies on specialized software tools and databases that implement methods for solving the Schrödinger equation across diverse chemical systems:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Computational Chemistry Research

| Resource Type | Examples | Primary Function | Role in Schrödinger Equation Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | Gaussian, Schrödinger Maestro, ATMO | Implement computational methods | Provide algorithms for solving electronic structure equations |

| Chemical Databases | Reaxys, BindingDB, RCSB, ChEMBL | Store chemical structures and properties | Provide experimental data for method validation |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | GAMESS, NWChem, ORCA | Perform ab initio calculations | Specialize in wave function-based electronic structure methods |

| Visualization Tools | Maestro, PyMOL | Represent molecular structures and orbitals | Translate wave function data into visual atomic models |

These tools enable researchers to apply the Schrödinger equation to practical chemical problems without developing computational methods from scratch. For example, the Schrödinger computational platform provides integrated tools for molecular modeling, visualization, and prediction of molecular properties, allowing researchers to bring "molecules to life on the computer" by accurately simulating properties that would otherwise require laboratory experimentation [14].

Databases play a crucial role in both validating computational methods and providing starting points for further exploration. The Reaxys database, containing millions of compounds and reactions, has been instrumental in tracing the historical development of chemical discovery and provides essential reference data for comparing computational predictions with experimental results [5] [4].

Applications and Impact: Transforming Chemical Research

Drug Design and Development

Computational chemistry has revolutionized pharmaceutical research by enabling the prediction of drug-target interactions without synthesizing every candidate compound [14]. For example, recent applications have demonstrated the ability to explore over 1 billion molecules computationally to design new inhibitors for therapeutic targets like d-amino acid oxidase (DAO) for schizophrenia treatment [14]. This approach combines quantum mechanics with machine learning to screen vast chemical spaces rapidly, accelerating the lead optimization process that traditionally required extensive laboratory work [14].

The integration of active learning with physics-based molecular docking represents another significant advancement, allowing researchers to test approximately 30,000 compounds per second compared to traditional computational methods that process about one compound every 30 seconds—a 10,000-fold speed increase [14]. This dramatic acceleration enables pharmaceutical researchers to explore chemical space more comprehensively while focusing synthetic efforts on the most promising candidates.

Materials Science and Industrial Applications

Beyond pharmaceuticals, computational chemistry methods have transformed materials design across multiple industries. In consumer packaged goods, companies like Reckitt use quantum mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations to design more sustainable materials, reportedly speeding development timelines by 10x on average compared to purely experimental approaches [14].

In energy research, atomic-scale modeling facilitates the design of improved battery technologies by simulating ion diffusion, electrochemical responses in electrodes and electrolytes, dielectric properties, and mechanical responses [14]. These computational approaches enable the screening of Li-ion battery additives that form stable solid electrolyte interfaces, a crucial factor in battery performance and longevity [14].

Catalysis represents another area where computational chemistry has made significant contributions. Modern electronic structure theory and density functional theory allow researchers to understand catalytic systems without extensive experimentation, predicting values like activation energy, site reactivity, and thermodynamic properties that guide catalyst design [3]. Computational studies provide insights into catalytic mechanisms that are difficult to observe experimentally, enabling the development of more efficient and selective catalysts for industrial applications [3].

Current Status and Future Directions

The field of computational chemistry continues to evolve, with ongoing developments in both methodological sophistication and computational infrastructure. The integration of machine learning with physics-based methods represents the current frontier, combining the accuracy of first-principles calculations with the speed of data-driven approaches [14]. This synergy addresses the fundamental trade-off between computational cost and accuracy that has constrained the application of quantum chemical methods to very large systems [14].

The historical analysis of chemical discovery suggests that we are currently in the organometallic regime, characterized by decreased variability in annual compound output and the rediscovery of metal-containing compounds [5] [4]. This era has also seen computational chemistry become fully integrated into the chemical research enterprise, with several Nobel Prizes recognizing contributions to the field, including the 1998 award to Walter Kohn and John Pople and the 2013 award to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel for developing multiscale models for complex chemical systems [3].

As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, the applications of Schrödinger's equation in chemistry will expand further, potentially enabling fully predictive molecular design across increasingly complex chemical and biological systems. This progression continues the quantum leap that began nearly a century ago, transforming chemistry from a primarily observational science to a computational and predictive one, fundamentally expanding our ability to explore chemical space and design novel molecules with desired properties.

The year 1927 marked a seminal moment in the history of theoretical chemistry, as Walter Heitler and Fritz London provided the first successful quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen molecule (H₂). This groundbreaking work, emerging just one year after Erwin Schrödinger published his wave equation, laid the foundational principles for understanding the covalent bond and established the cornerstones of what would later evolve into the field of computational chemistry [15] [16] [3]. Their approach, now known as the Heitler-London (HL) model or the valence bond method, demonstrated that chemical bonding could be understood through the application of quantum mechanics, moving beyond classical descriptions to explain the stability, bond length, and binding energy of molecules from first principles [17] [3].

The broader historical development of chemistry from 1800 to 2015 is characterized by exponential growth in the discovery of new compounds, with an annual growth rate of approximately 4.4% over this period [4]. This exploration of chemical space has transitioned through three distinct historical regimes: a proto-organic regime (before ~1860) with high variability in annual output, a more structured organic regime (approx. 1861-1980), and the current organometallic regime (approx. 1981-present) characterized by decreasing variability and more regular production [4]. The HL model emerged during the organic regime, providing the theoretical underpinnings for understanding molecular structure and bonding that would fuel further chemical discovery. The development of computational chemistry as a formal discipline represents a natural evolution from these early theoretical foundations, bridging the gap between chemical theory and the prediction of chemical phenomena.

The Heitler-London Model: Theoretical Foundations

The Quantum Mechanical Framework

The Heitler-London approach addressed the fundamental challenge of describing a four-particle system: two protons and two electrons. Within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which decouples nuclear and electronic motion due to the significant mass difference, the electronic Hamiltonian for the H₂ molecule in atomic units is given by [17] [16]:

$$ \hat{H} = -\frac{1}{2}{\nabla}1^{2} -\frac{1}{2}{\nabla}2^{2} -\frac{1}{r{1A}} -\frac{1}{r{1B}} -\frac{1}{r{2A}} -\frac{1}{r{2B}} +\frac{1}{r_{12}} +\frac{1}{R} $$

Table 1: Components of the Hydrogen Molecule Hamiltonian

| Term | Physical Significance |

|---|---|

| $-\frac{1}{2}\nabla1^2 -\frac{1}{2}\nabla2^2$ | Kinetic energy of electrons 1 and 2 |

| $-\frac{1}{r{1A}} -\frac{1}{r{1B}} -\frac{1}{r{2A}} -\frac{1}{r{2B}}$ | Attractive potential between electrons and protons |

| $\frac{1}{r_{12}}$ | Electron-electron repulsion |

| $\frac{1}{R}$ | Proton-proton repulsion |

The coordinates refer to the two electrons (1,2) and two protons (A,B), with $r{ij}$ representing the distance between particles $i$ and $j$, and $R$ the internuclear separation [16]. The complexity of this system lies in the electron-electron correlation term ($1/r{12}$), which prevents an exact analytical solution.

The Wave Function Ansatz

The key insight of Heitler and London was to construct a molecular wave function from a linear combination of atomic orbitals. For the hydrogen molecule, they proposed using the 1s orbitals of isolated hydrogen atoms:

$$ \phi(r{ij}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{\pi}} e^{-r{ij}} $$

where $\phi(r{ij})$ represents the 1s orbital for an electron at a distance $r{ij}$ from a proton [16]. The molecular wave function was then expressed as:

$$ \psi{\pm}(\vec{r}1,\vec{r}2) = N{\pm} [\phi(r{1A})\phi(r{2B}) \pm \phi(r{1B})\phi(r{2A})] $$

where $N_{\pm}$ is the normalization constant [16]. This wave function satisfies the fundamental requirement that as $R \to \infty$, it properly describes two isolated hydrogen atoms.

Bonding and Antibonding States

The symmetric ($\psi+$) and antisymmetric ($\psi-$) combinations of atomic orbitals give rise to bonding and antibonding states, respectively. When combined with the appropriate spin functions, these yield the singlet and triplet states of the hydrogen molecule [16]:

- Singlet State (Bonding): $\Psi{(0,0)}(\vec{r}1,\vec{r}2) = \psi+(\vec{r}1,\vec{r}2)\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|\uparrow\downarrow\rangle - |\downarrow\uparrow\rangle)$

- Triplet State (Antibonding): $\Psi{(1,1)}(\vec{r}1,\vec{r}2) = \psi-(\vec{r}1,\vec{r}2)|\uparrow\uparrow\rangle$, etc.

The bonding state corresponds to the electrons being spatially closer to both nuclei with opposite spins, resulting in a lower energy than two separated hydrogen atoms, thereby explaining the covalent bond formation [15] [16].

Figure 1: Theoretical workflow of the Heitler-London model showing the derivation of molecular states from atomic orbitals

Methodologies and Computational Approaches

Original Heitler-London Calculation Protocol

The original HL methodology followed a well-defined protocol for calculating molecular properties:

Wave Function Construction: Define the trial wave function as a linear combination of hydrogen 1s atomic orbitals as shown in Section 2.2.

Energy Calculation: Compute the total energy as a function of internuclear distance R using the variational integral: $$ \tilde{E}(R) = \frac{\int{\psi \hat{H} \psi d\tau}}{\int{\psi^2 d\tau}} $$ where $\hat{H}$ is the molecular Hamiltonian [17].

Energy Components: The total energy calculation involves determining several integrals representing:

- Coulomb integrals ($Q$) representing the energy of electron density around one nucleus interacting with the other nucleus

- Exchange integrals ($J$) representing the quantum mechanical exchange interaction

- Overlap integrals ($S$) measuring the spatial overlap of atomic orbitals

Optimization: Find the equilibrium bond length ($Re$) by identifying the minimum in the $E(R)$ curve, and calculate the binding energy ($De$) as the energy difference between the minimum and the dissociated atoms [17].

Modern Computational Refinements

Recent work by da Silva et al. (2025) has extended the original HL model by incorporating electronic screening effects [15] [16]. Their methodology includes:

Screening Modification: Introducing a variational parameter $\alpha(R)$ as an effective nuclear charge that accounts for how electrons screen each other from the nuclear attraction: $$ \phi(r{ij}) = \sqrt{\frac{\alpha^3}{\pi}} e^{-\alpha r{ij}} $$ where $\alpha$ is optimized as a function of $R$ [16].

Variational Quantum Monte Carlo (VQMC): Using stochastic methods to optimize the screening parameter and evaluate expectation values of the Hamiltonian with high accuracy, accounting for electron correlation effects beyond the mean-field approximation [15] [16].

Parameter Optimization: Determining $\alpha(R)$ by minimizing the energy with respect to this parameter at each internuclear separation, resulting in a function that describes how screening changes during bond formation and dissociation [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions – Computational Tools

| Computational Tool | Function/Role | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen 1s Atomic Orbitals | Basis functions for molecular wave function | $\phi(r) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{\pi}} e^{-r}$ [16] |

| Variational Principle | Energy optimization method | $\tilde{E} = \frac{\int{\psi \hat{H} \psi d\tau}}{\int{\psi^2 d\tau}}$ [17] |

| Effective Nuclear Charge ($\alpha$) | Accounts for electronic screening | Modified orbital: $\phi(r) = \sqrt{\frac{\alpha^3}{\pi}} e^{-\alpha r}$ [16] |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | Stochastic evaluation of integrals | Uses random sampling for high-accuracy correlation energy [15] |

Quantitative Results and Comparison

Molecular Properties of H₂

The Heitler-London model yielded quantitative predictions for the hydrogen molecule that, while approximate, captured the essential physics of the covalent bond:

Table 3: Comparison of H₂ Molecular Properties Across Computational Methods

| Method | Bond Length (Å) | Binding Energy (eV) | Vibrational Frequency (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original HL Model (1927) | ~0.90 [17] | ~0.25 [17] | Not reported |

| Screening-Modified HL (2025) | ~0.74 [16] | Improved agreement | Improved agreement |

| Experimental | 0.7406 [17] | 4.746 [17] | 4401 |

The original HL calculation obtained a binding energy of approximately 3.14 eV (0.25 eV according to [17]) and an equilibrium bond length of about 1.7 bohr (~0.90 Å), which, while qualitatively correct, significantly underestimated the actual binding strength of the molecule [17] [16]. The screening-modified HL model shows substantially improved agreement with experimental values, particularly for the bond length [16].

Energy Components and Potential Curves

The HL model decomposes the molecular energy into physically interpretable components:

Coulomb Integral (Q): Represents the classical electrostatic interaction between the charge distributions of two hydrogen atoms.

Exchange Integral (J): A purely quantum mechanical term arising from the indistinguishability of electrons, responsible for the energy splitting between bonding and antibonding states.

Overlap Integral (S): Measures the spatial overlap between atomic orbitals, influencing the normalization and strength of interaction.

The potential energy curve obtained from the original HL calculation shows the characteristic shape of a molecular bond: repulsive at short distances, a minimum at the equilibrium bond length, and asymptotic approach to the separated atom limit at large R [17]. The screening-modified model produces a potential curve with a deeper well and minimum at shorter bond lengths, in better agreement with high-precision calculations and experimental data [16].

Figure 2: Computational workflow for the screening-modified Heitler-London calculation

Historical Significance and Modern Context

Foundation of Computational Chemistry

The Heitler-London model represents the pioneering effort in what would become the field of computational chemistry. Their 1927 calculation marks the first successful application of quantum mechanics to a molecular system, establishing several fundamental concepts [3]:

Covalent Bond Explanation: Provided the first quantum mechanical explanation of the covalent bond as arising from electron sharing between atoms.

Valence Bond Theory: Established the basic principles of valence bond theory, which would compete with molecular orbital theory for describing chemical bonding.

Quantum Chemistry Methodology: Introduced the conceptual and methodological framework for performing quantum chemical calculations on molecules.

The historical development of computational chemistry from this foundation can be traced through several key advancements: the early semi-empirical methods of the 1950s, the development of ab initio Hartree-Fock methods, the introduction of density functional theory by Kohn in the 1960s, and the emergence of sophisticated computational packages like Gaussian [3]. The field was formally recognized with Nobel Prizes in 1998 to Walter Kohn and John Pople, and in 2013 to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel for developing multiscale models for complex chemical systems [9] [3].

Contemporary Applications and Relevance

The legacy of the Heitler-London approach continues in modern computational chemistry, particularly in drug development and materials science [3]:

Drug Design: Computational methods derived from these quantum mechanical principles are used to model drug-receptor interactions, predict binding affinities, and optimize pharmaceutical compounds before synthesis [3].

Catalysis Research: Computational chemistry enables the analysis of catalytic systems without extensive experimentation, predicting activation energies and reaction pathways for catalyst design [3].

Materials Science: The principles established in the HL model underpin calculations of electronic structure, band gaps, and properties of novel materials [3].

Quantum Chemistry Software: Modern computational packages (Gaussian, GAMESS, VASP) implement advanced methods that remain conceptually indebted to the HL approach [3].

The exponential growth in chemical discovery documented from 1800 to 2015, with distinct regimes of chemical exploration, has been accelerated by these computational approaches [4]. The transition from the proto-organic to organic regime around 1860 coincided with the development of structural theory, while the current organometallic regime (post-1980) benefits from sophisticated computational design methods rooted in the quantum mechanical principles first established by Heitler and London [4].

The period preceding the advent of digital computers established the foundational theoretical frameworks and calculational techniques that would later enable the emergence of computational chemistry as a formal discipline. This era was characterized by the development of mathematical descriptions of chemical systems and the ingenious application of manual approximation methods to solve complex quantum mechanical equations. Chemists and physicists devised strategies to simplify the many-body problem inherent in quantum systems, making calculations tractable with the available tools—primarily pencil, paper, and mechanical calculators. These early efforts were crucial for building the conceptual infrastructure that would later be encoded into computer programs, allowing for the quantitative prediction of molecular structures, properties, and reaction paths [3]. The work of this period, though computationally limited by modern standards, provided the essential theories and validation needed for the subsequent exponential growth of chemical knowledge [4].

Historical Context and the Growth of Chemical Knowledge (1800-1950)

The exploration of chemical space long preceded the formal establishment of computational chemistry. Analysis of historical data reveals that the reporting of new chemical compounds grew at an exponential rate of approximately 4.4% annually from 1800 to 2015, a trend remarkably stable through World Wars and scientific revolutions [4]. This exploration occurred through three distinct historical regimes, the first two of which fall squarely within the pre-computer era.

- The Proto-Organic Regime (pre-1860): This period was characterized by high variability in the year-to-year output of new compounds, with an annual growth rate of approximately 4.04%. Chemistry during this era focused on the extraction and analysis of animal and plant products alongside inorganic compounds. Contrary to common belief, synthesis was already a key provider of new compounds well before Friedrich Wöhler's 1828 synthesis of urea, though the methods were not yet systematic or guided by a unified structural theory [4].

- The Organic Regime (1861-1980): The establishment of structural theory around 1860 marked a sharp transition to a period of more regular and guided chemical production, with an annual growth rate of 4.57%. This theory provided a conceptual map for chemical space, enabling chemists to plan syntheses more rationally and leading to a significant decrease in the variability of chemical output [4]. The dominance of carbon-, hydrogen-, nitrogen-, oxygen-, and halogen-based compounds solidified during this period.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these historical regimes, highlighting the shifting patterns of chemical exploration during the pre-computer and early computer eras [4].

Table 1: Historical Regimes in the Exploration of Chemical Space

| Regime | Period | Annual Growth Rate (μ) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Organic | Before 1861 | 4.04% | High variability; extraction from natural sources; early synthesis; no unifying structural theory. |

| Organic | 1861–1980 | 4.57% | Guided by structural theory; decreased variability; dominance of organic molecules. |

| Organometallic | 1981–2015 | 2.96% | Rise of organometallic compounds; lowest variability; enabled by advanced computational modeling. |

The scientist's toolkit evolved significantly throughout these regimes. The following table details the most frequently used chemical reagents during various sub-periods, illustrating the changing focus and available materials for experimental and theoretical work [4].

Table 2: Evolution of Key Research Reagents (Top 3 by Period)

| Period | Top Reagents |

|---|---|

| Before 1860 | H₂O, NH₃, HNO₃ |

| 1860-1879 | H₂O, HCl, H₂SO₄ |

| 1880-1899 | HCl, EtOH, H₂O |

| 1900-1919 | EtOH, HCl, AcOH |

Foundational Theoretical Frameworks

The pre-computer era was marked by the development of several pivotal theoretical frameworks that provided the mathematical foundation for describing chemical systems.

The Birth of Quantum Chemistry

The first theoretical chemistry calculations stemmed directly from the founding discoveries of quantum mechanics. A landmark achievement was the 1927 work of Walter Heitler and Fritz London, who applied valence bond theory to the hydrogen molecule. This represented the first successful quantum mechanical treatment of a chemical bond, demonstrating that the stability of the molecule could be explained through the wave-like nature of electrons and their linear combination [3] [9]. This work proved that chemical bonding could be understood through the application of quantum theory, paving the way for a more rigorous and predictive theoretical chemistry.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Introduced in 1927, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation became a cornerstone of quantum chemistry. This approximation simplifies the molecular Schrödinger equation by exploiting the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei. It posits that due to their much heavier mass, nuclei move much more slowly than electrons. Consequently, the motion of the nuclei and electrons can be treated separately: the electrons can be considered as moving in a field of fixed nuclei [18]. This separation reduces the complexity of the problem dramatically. For example, the benzene molecule (12 nuclei and 42 electrons) presents a partial differential eigenvalue equation in 162 variables. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation allows this to be separated into a more manageable form, making hand-calculation of electronic structure for small systems feasible [18].

The Hartree Method and the Self-Consistent Field

Developed by Douglas Hartree in 1928, the Hartree method was a crucial step towards tackling multi-electron systems. The fundamental challenge is the electron-electron repulsion term in the Hamiltonian, which couples the motions of all electrons and makes the Schrödinger equation unsolvable without approximation. Hartree's key insight was to assume that each electron moves in an averaged potential created by the nucleus and the cloud of all other electrons [18]. This effective potential depends only on the coordinates of the single electron in question. The solution is found iteratively: an initial guess for the wavefunctions is made, the potential is calculated, and new wavefunctions are solved for. This process is repeated until the wavefunctions and potential become consistent, hence the name Self-Consistent Field (SCF) method. While this method neglected the fermionic nature of electrons (later corrected by Fock and Slater), it established the core SCF procedure that remains central to electronic structure calculations today.

Key Hand-Calculated Approximation Methods

With the theoretical frameworks in place, chemists developed specific approximation methods to perform practical calculations.

The Hückel Method

Proposed by Erich Hückel in the 1930s, Hückel Molecular Orbital (HMO) theory was a semi-empirical method designed to provide a qualitative, and later semi-quantitative, understanding of the π-electron systems in conjugated hydrocarbons. Its power lay in its drastic simplifications, which made hand-calculation of molecular orbital energies and wavefunctions possible for relatively large organic molecules [3]. The method's approximations include:

- σ-π Separation: The π-electrons are treated independently from the σ-framework, which is considered a rigid core.

- Differential Overlap Neglect: Certain integrals in the secular equations are set to zero.

- Parameterization: The Hamiltonian matrix elements are replaced with empirical parameters: the Coulomb integral (α) for the energy of an electron in a 2p orbital, and the resonance integral (β) for the interaction energy between two adjacent 2p orbitals [3].

By the 1960s, researchers were using computers to perform Hückel method calculations on molecules as complex as ovalene, but the method was originally designed for and successfully applied through manual calculation [3].

Semi-Empirical Methods

The need for more quantitative accuracy than Hückel theory could provide, while still avoiding the computational intractability of ab initio methods, led to the development of more sophisticated semi-empirical methods in the 1960s, such as CNDO (Complete Neglect of Differential Overlap) [3]. These methods retained the core LCAO (Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals) formalism of Hartree-Fock theory but made further approximations. They neglected certain classes of two-electron integrals and parameterized others based on experimental data (e.g., ionization potentials, electron affinities). This approach incorporated some of the effects of electron correlation empirically, yielding results that were more accurate than simple Hückel theory and could be applied to a wider range of molecules, though they still largely depended on manual setup and calculation before the widespread use of digital computers.

Methodologies for Early Calculations

The workflow for theoretical calculations in the pre-computer era was meticulous and labor-intensive, requiring a deep understanding of both the chemical system and the mathematical tools.

The Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) Approach

The LCAO approach forms the basis for most molecular orbital calculations. The methodology involves several key steps that were executed manually [3] [18]:

- Basis Set Selection: The calculation begins by selecting a set of atomic orbitals (the basis set) for each atom in the molecule. In early hand calculations, these were typically Slater-type orbitals (STOs) or minimal sets of hydrogen-like orbitals.

- Construction of the Secular Equation: The molecular orbitals are written as linear combinations of the chosen atomic orbitals. This leads to the formulation of the secular equation: H - ES = 0, where H is the Hamiltonian matrix, E is the orbital energy, and S is the overlap matrix.

- Matrix Element Calculation: The matrix elements of H and S are calculated based on the chosen approximation level (e.g., Hückel, semi-empirical). This often involved consulting tables of integrals and applying empirical parameters.

- Solving the Secular Determinant: The secular equation is solved by finding the roots of the secular determinant |H - ES| = 0. This yields the orbital energies (E). For a molecule with N basis functions, this is an N-th order polynomial equation.

- Determination of Molecular Orbitals: For each orbital energy, the coefficients in the LCAO expansion are determined by solving a system of linear equations. These coefficients define the shape and nodal structure of each molecular orbital.

- Electron Assignment and Property Calculation: Electrons are assigned to the molecular orbitals according to the Aufbau principle and Hund's rule. Finally, total electron density, bond orders, and other properties are derived from the occupied orbitals.

Workflow for a Hückel Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for performing a hand-calculated Hückel method study of a conjugated molecule.

Limitations and Challenges of Pre-Computer Calculations

Theoretical work in the pre-computer era was fundamentally constrained by the tools available. The primary challenge was the exponential scaling of computational effort with system size. Solving the secular determinant for a molecule with N basis functions involved finding the roots of an N-th order polynomial, a task that becomes prohibitively difficult for all but the smallest molecules as N increases. This severely limited the size and complexity of molecules that could be practically studied. Polyatomic molecules with more than a few heavy atoms were largely beyond reach for all but the most approximate methods like Hückel theory [3].

Furthermore, the neglect of electron correlation was a major source of inaccuracy. Methods like Hartree-Fock and Hückel theory treated electrons as moving in an average field, ignoring the correlated nature of their instantaneous repulsions. This led to systematic errors in predicting properties like bond dissociation energies and reaction barriers. While post-Hartree-Fock methods like Configuration Interaction (CI) were developed conceptually in the 1950s, they were computationally intractable for any meaningful chemical system without electronic computers [3]. The lack of computing power also meant that relativistic effects were almost entirely neglected, limiting accurate quantum chemical descriptions to elements in the first few rows of the periodic table [18].

The pre-computer era of theoretical chemistry was a period of profound intellectual achievement. Despite being limited to manual calculations, chemists and physicists established the core principles that would define the field: the application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems, the development of critical approximations like Born-Oppenheimer, and the creation of tractable computational models like the Hartree-Fock method and Hückel theory. The exponential growth of chemical knowledge during the Organic regime (1861-1980) was, in part, enabled by these theoretical frameworks, which provided a guided, rational approach to exploring chemical space [4]. The painstaking hand-calculations of this period not only solved specific chemical problems but also validated the underlying theories, creating a solid foundation. When digital computers finally became available in the latter half of the 20th century, this well-established conceptual framework was ready to be translated into code, launching computational chemistry as a formal discipline and unlocking the potential for the accurate modeling of complex chemical systems.

The Computing Revolution: Key Methodologies and Their Transformative Applications

The period from the 1950s to the 1960s marked a revolutionary epoch in chemistry, characterized by the transition from purely theoretical mathematics to practical computational experimentation. This era witnessed the birth of computational chemistry as a distinct discipline, enabled by the advent of digital computers that provided the necessary tools to obtain numerical approximations to the solution of the Schrödinger equation for chemical systems [19]. Prior to these developments, theoretical chemists faced insurmountable mathematical barriers in solving quantum mechanical equations for all but the simplest systems, leaving them unable to make quantitative predictions about molecular behavior [3] [19].

The dawn of digital chemistry emerged from a convergence of factors: the foundational work of theoretical physicists in the 1920s-1940s, the rapid development of digital computer technology during and after World War II, and the pioneering efforts of chemists who recognized the potential of these new tools [19] [20]. This transformation occurred within the broader context of chemistry's historical development, where the exponential growth in chemical discovery had already been established, with new compounds reported at a stable 4.4% annual growth rate from 1800 to 2015 [4] [5].

This article examines the groundbreaking work of the 1950s and 1960s that laid the foundation for modern computational chemistry, focusing on the first semi-empirical and ab initio calculations that transformed theoretical concepts into practical computational tools.

Historical and Scientific Context

The Pre-Computational Landscape (Pre-1950)

The groundwork for computational chemistry was established through pioneering theoretical developments in quantum mechanics throughout the early 20th century. The Heitler-London study of 1927, which applied valence bond theory to the hydrogen molecule, represented one of the first successful theoretical calculations in chemistry [3]. This work demonstrated that quantum mechanics could quantitatively describe chemical bonding, yet the mathematical complexity of solving the Schrödinger equation for systems with more than two electrons prevented widespread application of these methods [3].

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, influential textbooks by Pauling and Wilson, Eyring, Walter and Kimball, and Coulson served as primary references for chemists, establishing the theoretical framework that would later become computationally accessible [3]. During this period, chemistry continued its steady exploration of chemical space, with the proto-organic regime (pre-1860) giving way to the organic regime (1861-1980), characterized by more regular year-to-year output of new compounds dominated by carbon- and hydrogen-containing molecules [4].

The development of electronic computers during World War II provided the essential technological breakthrough that would enable theoretical chemistry to evolve into computational chemistry. In the postwar period, these machines became available for general scientific use, coinciding with a declining interest among physicists in molecular structure problems [19]. This created an opportunity for chemists to establish a new discipline focused on obtaining quantitative molecular information through numerical approximations [19].

The Theoretical Framework

The fundamental challenge that computational chemistry addressed was the many-body problem inherent in quantum mechanical descriptions of chemical systems. The Schrödinger equation, while providing a complete description of a quantum system, was mathematically intractable for systems with more than two electrons without introducing approximations [3] [19].

The time-independent Schrödinger equation for a system of particles is:

[ Hψ = Eψ ]

Where H is the Hamiltonian operator, ψ is the wavefunction, and E is the energy of the system [19]. For molecular systems, the Hamiltonian includes terms for electron kinetic energy, nuclear kinetic energy, and all Coulombic interactions between electrons and nuclei [19].

Two fundamental approaches emerged to make these calculations feasible:

- Ab initio methods: Solving the Schrödinger equation using only fundamental physical constants without empirical parameters [3]

- Semi-empirical methods: Introducing approximations and experimental parameters to simplify calculations [3]

The complexity of these calculations required the computational power that only digital computers could provide, setting the stage for the revolutionary developments of the 1950s.

Foundational Computational Methods

Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry

The term "ab initio" (Latin for "from the beginning") refers to quantum chemical methods that solve the molecular Schrödinger equation using only fundamental physical constants without inclusion of empirical or semi-empirical parameters [3]. These methods are rigorously defined on first principles and aim for solutions within qualitatively known error margins [3].

Ab initio methods require the definition of two essential components:

- Level of theory: The specific mathematical approximations used to solve the Schrödinger equation [3]

- Basis set: A set of functions centered on the molecule's atoms used to describe molecular orbitals via the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) approach [3]

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method emerged as a common type of ab initio electronic structure calculation, extending molecular orbital theory by including the average effect of electron-electron repulsions but not their specific interactions [3]. As basis set size increases, the energy and wave function tend toward a limit called the Hartree-Fock limit [3]. Going beyond Hartree-Fock requires methods that correct for electron-electron repulsion (electronic correlation), leading to the development of post-Hartree-Fock methods [3].

Semi-Empirical Methods

Semi-empirical methods represent a practical alternative to ab initio calculations by introducing approximations and experimental parameters to simplify computations. These methods reduce computational complexity by neglecting certain integrals or parameterizing them based on experimental data [3].

The development of semi-empirical methods followed a historical progression:

- Hückel method (1964): Used a simple linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) to determine electron energies of molecular orbitals of π electrons in conjugated hydrocarbon systems [3]

- CNDO (1960s): Complete Neglect of Differential Overlap replaced earlier empirical methods with more sophisticated semi-empirical approaches [3]

These methods played a crucial role in extending computational chemistry to larger molecules during the 1960s when computational resources were still limited.

Key Developments and Pioneers (1950-1960)

Major Theoretical and Computational Advances

Table 1: Key Developments in Computational Chemistry (1950-1960)

| Year | Development | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950-1955 | Early polyatomic calculations using Gaussian orbitals | Boys and coworkers [3] | First configuration interaction calculations performed on EDSAC computer |

| 1951 | LCAO MO approach paper | Clemens C. J. Roothaan [3] | Established foundational methodology; became second-most cited paper in Reviews of Modern Physics |

| 1956 | First ab initio Hartree-Fock calculations on diatomic molecules | MIT researchers [3] | Used basis set of Slater orbitals; demonstrated feasibility of ab initio methods |

| 1960 | Systematic study of diatomic molecules with minimum basis set | Ransil [3] | Extended ab initio methods to broader range of systems |

| 1960 | First calculation with larger basis set | Nesbet [3] | Demonstrated importance of basis set size for accuracy |

| 1964 | Hückel method calculations of conjugated hydrocarbons | Berkeley and Oxford researchers [3] | Applied semi-empirical methods to molecules ranging from butadiene to ovalene |

The 1950s witnessed foundational work that established the core methodologies of computational quantum chemistry. Although this decade produced virtually no predictions of chemical interest, it established the essential framework for future applications [21]. Much of this fundamental research was conducted in the laboratories of Frank Boys in Cambridge and Clemens Roothaan and Robert Mulliken in Chicago [21].

Significant contributions during this period came from numerous theoretical chemists including Klaus Ruedenberg, Robert Parr, John Pople, Robert Nesbet, Harrison Shull, Per-Olov Löwdin, Isaiah Shavitt, Albert Matsen, Douglas McLean, and Bernard Ransil [21]. Their collective work established the algorithms and mathematical formalisms that would enable practical computational chemistry in the following decades.

Pioneers of Computational Chemistry

Table 2: Key Pioneers in Early Computational Chemistry

| Researcher | Institution | Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Frank Boys | Cambridge University | Pioneered use of Gaussian orbitals for polyatomic calculations; performed first configuration interaction calculations [3] [21] |

| Clemens C. J. Roothaan | University of Chicago | Developed LCAO MO approach; published highly influential 1951 paper that became a foundational reference [3] [21] |

| Robert Mulliken | University of Chicago | Contributed to molecular orbital theory; provided theoretical foundation for computational approaches [21] [20] |

| John Pople | Cambridge University | Developed computational methods in quantum chemistry; later awarded Nobel Prize in 1998 [3] |

| Bernard Ransil | Conducted systematic study of diatomic molecules using minimum basis set (1960) [3] | |

| Robert Nesbet | Performed first calculations with larger basis sets (1960) [3] |

The collaborative nature of this emerging field is evident in the network of researchers who built upon each other's work. The cross-pollination of ideas between different research groups accelerated methodological developments, while the sharing of computer programs established a culture of collaboration that would characterize computational chemistry for decades to come.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Early Ab Initio Workflow

The first ab initio calculations followed a systematic workflow that combined theoretical framework with practical computational implementation. The following diagram illustrates the generalized protocol for these pioneering calculations:

The computational process began with the definition of the molecular system, typically focusing on diatomic molecules or small polyatomic systems due to computational constraints [3]. Researchers would then select an appropriate theoretical method, with the Hartree-Fock approach being the most common for early ab initio work [3].

The choice of basis set was critical, with early calculations employing either:

- Slater-type orbitals (STOs): More accurate representation of atomic orbitals but computationally demanding [3]

- Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs): Computational advantages for integral evaluation, though requiring more functions for equivalent accuracy [3]

The input preparation involved specifying molecular coordinates and basis set definitions, followed by the computation of one- and two-electron integrals and the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure to solve the Hartree-Fock equations iteratively [3].

Technical Specifications of Early Calculations

The first ab initio calculations were characterized by severe limitations in both hardware and methodology:

- Basis sets: Early calculations used minimal basis sets with just enough functions to accommodate the electrons of the constituent atoms [3]

- Integral evaluation: Computation of two-electron integrals presented significant computational challenges, with early calculations often neglecting or approximating certain classes of integrals [3]

- SCF convergence: The self-consistent field procedure required iterative solution, with convergence often problematic for early calculations [3]

- Computer systems: Calculations were performed on mainframe computers such as EDSAC with limited memory and processing speed by modern standards [3]

Despite these limitations, these pioneering calculations established the protocols and methodologies that would be refined throughout the following decades.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" in Early Quantum Chemistry

| Resource | Type | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Mathematical Functions | Describe atomic and molecular orbitals | Slater-type orbitals (STOs), Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) [3] |

| Theoretical Methods | Computational Algorithms | Approximate solution to Schrödinger equation | Hartree-Fock, Configuration Interaction, Valence Bond [3] |

| Computer Programs | Software | Implement computational methods | ATMOL, Gaussian, IBMOL, POLYAYTOM [3] |

| Integral Packages | Mathematical Routines | Compute one- and two-electron integrals | Fundamental for molecular orbital calculations [3] |

| SCF Algorithms | Numerical Methods | Solve self-consistent field equations | Iterative procedures for Hartree-Fock calculations [3] |

The "research reagents" of computational chemistry differed fundamentally from those of experimental chemistry, consisting of mathematical tools and computational resources rather than chemical substances. The basis set served as the fundamental building block, with Slater-type orbitals used in the first diatomic calculations and Gaussian-type orbitals enabling the first polyatomic calculations [3].

Theoretical methods formed the core algorithms that approximated solutions to the Schrödinger equation, with the Hartree-Fock method providing the starting point for most early ab initio work [3]. The development of computer programs such as ATMOL, Gaussian, IBMOL, and POLYAYTOM in the early 1970s represented the culmination of the methodological work begun in the 1950s, though only Gaussian remains in widespread use today [3].

Computational Hardware Environment

The hardware environment for these early calculations presented significant constraints:

- Computer systems: Mainframe computers with limited memory and processing speed compared to modern standards [3]

- Storage: Punch cards and magnetic tape for program input and data storage [3]

- Processing time: Calculations that now take seconds could require days or weeks of computation time [3]

- Programming: Low-level programming languages and manual optimization of computational routines [3]

Despite these limitations, the increasing accessibility of computers throughout the 1950s and 1960s enabled theoretical chemists to perform calculations that were previously impossible [3] [19].

Impact and Historical Significance

Immediate Scientific Impact

The development of computational chemistry in the 1950s and 1960s created a new paradigm for chemical research, establishing a third pillar of chemical investigation alongside experimental and theoretical approaches. While the immediate chemical predictions from early ab initio work were limited, the field laid an essential foundation for future applications [21].

The relationship between computational and theoretical chemistry became clearly defined during this period: theoretical chemists developed algorithms and computer programs, while computational chemists applied these tools to specific chemical questions [3]. This division of labor accelerated progress in both domains, with computational applications highlighting limitations in existing theories and driving methodological improvements.

By the late 1960s, computational chemistry began to achieve notable successes, such as the work by Kolos and Wolniewicz on the hydrogen molecule. Their highly accurate calculations of the dissociation energy diverged from accepted experimental values, prompting experimentalists to reexamine their measurements and ultimately confirming the theoretical predictions [19]. This reversal of the traditional validation process demonstrated the growing maturity and reliability of computational approaches.

Integration into Broader Chemical Research

The emergence of computational chemistry occurred within the broader context of chemical research, which had maintained a stable exponential growth in the discovery of new compounds since 1800 [4] [5]. Computational methods would eventually enhance this exploration of chemical space, though their significant impact on chemical discovery would not be realized until later decades.

The methodologies developed during the 1950s and 1960s established the foundation for computational chemistry's eventual applications in diverse areas including:

- Catalysis research: Analyzing catalytic systems without experiments by calculating energies, activation barriers, and thermodynamic properties [3]

- Drug development: Modeling potentially useful drug molecules to save time and cost in the discovery process [3]

- Materials science: Predicting structures and properties of molecules and solids [3]

- Chemical databases: Storing and searching data on chemical entities [3]

The pioneering work of this era would eventually be recognized through Nobel Prizes in Chemistry awarded to Walter Kohn and John Pople in 1998 and to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel in 2013 [3].

The period from 1950 to 1960 represents the true dawn of digital chemistry, when theoretical concepts transformed into practical computational methodologies. The pioneering work in semi-empirical and ab initio calculations established the foundational principles, algorithms, and computational approaches that would enable the explosive growth of computational chemistry in subsequent decades.

The development of these early computational methods occurred within the broader historical context of chemistry's steady expansion, characterized by exponential growth in chemical discovery since 1800 [4] [5]. The computational approaches established in the 1950s and 1960s would eventually enhance this exploration of chemical space, though their significant impact would not be fully realized until later decades when computational power increased and methodologies matured.

The collaboration between theoretical chemists, who developed algorithms, and computational chemists, who applied these tools to chemical problems, created a synergistic relationship that accelerated progress in both domains [3]. The methodological framework established during this formative period—encompassing basis sets, theoretical methods, computational algorithms, and validation procedures—continues to underpin modern computational chemistry, demonstrating the enduring legacy of these pioneering efforts.

The evolution of computational chemistry from a theoretical concept to a practical scientific tool represents one of the most significant transformations in modern chemical research. This progression was enabled by fundamental algorithmic breakthroughs in three interdependent areas: the development of the Hartree-Fock method for approximating electron behavior, the creation of basis sets for mathematically representing atomic orbitals, and continuous improvements in computational feasibility through both hardware and software innovations. These developments did not occur in isolation but rather through a complex interplay between theoretical chemistry, physics, mathematics, and computer science.

The trajectory of computational quantum chemistry reveals a fascinating history of interdisciplinary exchange. As noted by historians, quantum chemistry originally occupied an uneasy position "in-between" physics and chemistry before eventually establishing itself as a distinct subdiscipline [22]. This transition was catalyzed by the advent of digital computers, which enabled the practical application of theoretical frameworks that had been developed decades earlier. The period around 1990 marked a particularly significant turning point, often described as the "computational turn" in quantum chemistry, characterized by new modeling conceptions, decentralized computing infrastructure, and market-like organization of the field [22].

This review examines the intertwined development of Hartree-Fock methodologies, basis set formulations, and the progressive enhancement of computational feasibility that together transformed quantum chemistry from a theoretical endeavor to an indispensable tool across chemical disciplines.

Historical Foundations: From Theoretical Concepts to Practical Computation

The Pre-Computing Era (1920s-1950s)