Homoscedasticity vs. Heteroscedasticity: A Biomedical Researcher's Guide to Valid Model Residuals

This article provides a comprehensive guide for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, detecting, and correcting heteroscedasticity in statistical models.

Homoscedasticity vs. Heteroscedasticity: A Biomedical Researcher's Guide to Valid Model Residuals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, detecting, and correcting heteroscedasticity in statistical models. Covering foundational concepts through advanced applications, we explore the critical implications of residual variance patterns on the reliability of regression analyses, hypothesis testing, and polygenic risk scores in clinical and pharmacological research. Practical methodologies for visual and statistical diagnosis are detailed, alongside robust correction techniques including weighted regression, variable transformation, and modern error modeling approaches specifically relevant to pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

What is Heteroscedasticity? Core Concepts for Biomedical Data

Defining Homoscedasticity and Heteroscedasticity in Statistical Modeling

Within the broader research on model residuals, understanding the dynamics of error variance is fundamental to building reliable statistical models. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity—concepts describing the consistency, or lack thereof, of the error term's variance across observations in regression analysis. Violations of the homoscedasticity assumption, a cornerstone of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, can lead to biased standard errors, inefficient parameter estimates, and ultimately, invalid statistical inference. This guide details the theoretical foundations, practical consequences, robust detection methodologies, and corrective measures for heteroscedasticity, with a specific focus on applications relevant to researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and other data-intensive fields.

Core Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

In statistical modeling, particularly linear regression, the error term (also known as the residual or disturbance) represents the discrepancy between the observed data and the values predicted by the model. The behavior of this error term is governed by key assumptions, one of the most critical being the characteristics of its variance [1] [2].

Homoscedasticity describes a situation where the variance of the error term is constant across all levels of the independent variables [1] [3]. Formally, for a sequence of random variables, homoscedasticity is present if all random variables have the same finite variance:

Var(u_i|X_i=x) = σ²for all observationsi=1,…,n[1] [3]. This property is also known as the homogeneity of variance. In practical terms, it means the model's predictions are equally reliable across the entire range of the data. Visually, on a plot of residuals versus predicted values, homoscedasticity is indicated by a random, unstructured band of points evenly spread around zero [4] [5].Heteroscedasticity is the violation of this assumption, occurring when the variance of the error term is not constant but differs across the values of one or more independent variables [1] [2]. Formally, this is denoted as

Var(u_i|X_i=x) = σ_i²[3]. The residual plot for heteroscedastic data often exhibits systematic patterns, most commonly a fan-shaped or cone-shaped scatter, where the spread of the residuals increases or decreases with the fitted values [5] [6]. It is crucial to note that heteroscedasticity does not cause bias in the OLS coefficient estimates themselves, but it invalidates the standard errors and statistical tests derived under the homoscedasticity assumption [1] [5].

The table below summarizes the core distinctions between these two states.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Homoscedasticity and Heteroscedasticity

| Aspect | Homoscedasticity | Heteroscedasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Constant variance of the error term across observations [1]. | Non-constant variance of the error term across observations [1]. |

| Key Property | Homogeneity of variance [1]. | Heterogeneity of variance [1]. |

| Impact on OLS Coefficients | Unbiased and efficient (Best Linear Unbiased Estimator) [1]. | Unbiased but inefficient [1]. |

| Impact on Standard Errors | Reliable and unbiased [1]. | Biased and unreliable, leading to misleading inference [1] [2]. |

| Visual Pattern in Residual Plot | Random, unstructured scatter forming a horizontal band [4]. | Systematic pattern, often a fan or cone shape (e.g., spread increases with fitted values) [5]. |

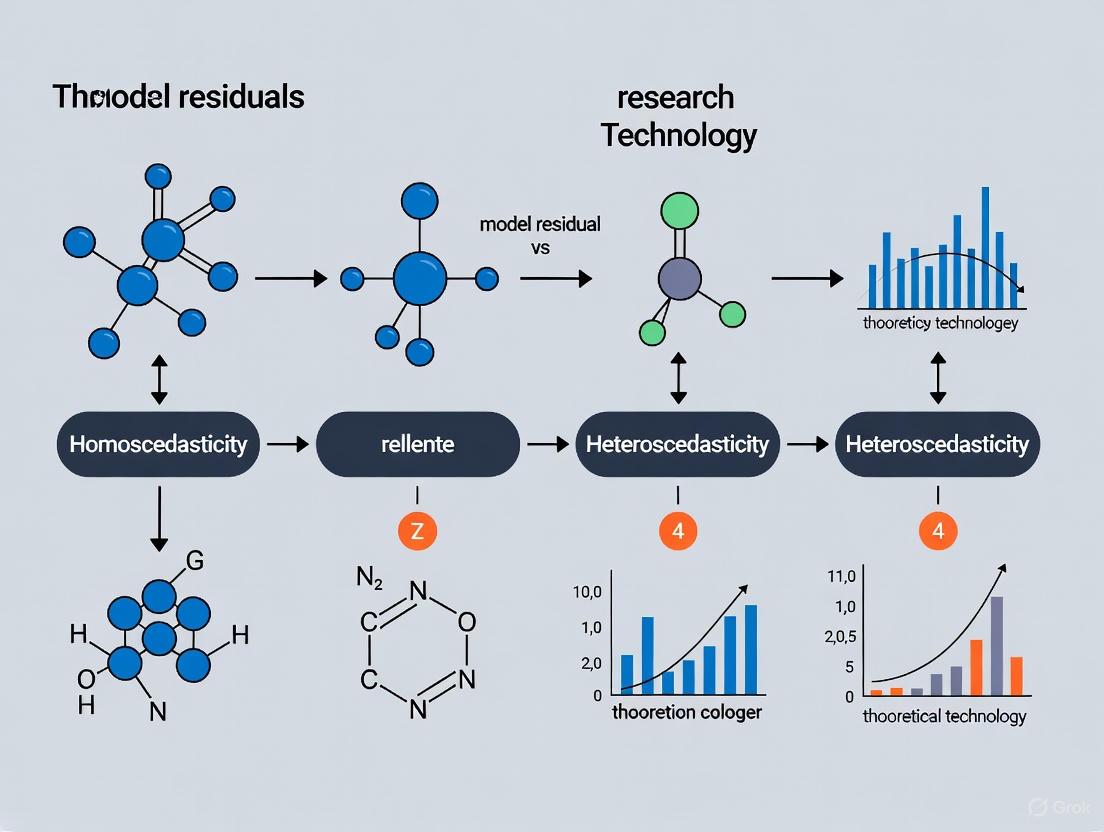

A Conceptual Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core concepts, the problems arising from heteroscedasticity, and the available solutions, providing a high-level overview of the domain.

Consequences for Statistical Inference and Model Validity

The presence of heteroscedasticity has profound implications for the validity of a regression model's output. While the OLS coefficient estimates remain unbiased, their reliability is compromised [1] [5].

- Inefficient Estimates: The OLS estimators are no longer the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE). This means that while they are correct on average, other unbiased estimators could exist with smaller variances, making the OLS estimates less precise [1].

- Biased Standard Errors and Invalid Inference: The most severe problem is that the standard formulas for the standard errors of the coefficients assume homoscedasticity. When this assumption is violated, the calculated standard errors are biased [1] [2]. This bias directly impacts all statistical inference:

- t-statistics and p-values: The t-statistics for coefficient significance become unreliable. Heteroscedasticity often leads to an underestimation of the standard errors, resulting in inflated t-statistics and p-values that are smaller than they should be [5]. This increases the risk of Type I errors, where a researcher falsely declares a predictor as statistically significant [1].

- Confidence Intervals: Biased standard errors lead to incorrect confidence intervals. They may be narrower or wider than they should be, providing a false sense of precision or uncertainty about the parameter estimates [4].

- Impact on Model Fit: Heteroscedasticity can lead to overestimating the goodness of fit as measured by the Pearson coefficient [1].

The problem's severity is amplified in unbalanced designs where sample sizes across groups are unequal, and the smaller samples come from populations with larger standard deviations [7].

Detection and Diagnostic Methodologies

A systematic approach to diagnosing heteroscedasticity is crucial for validating model assumptions. The following workflow and subsequent sections detail the primary methods, ranging from visual exploration to formal statistical tests.

Diagnostic Workflow

A robust diagnostic protocol typically progresses from visual checks to formal testing, as outlined below.

Visual Inspection: Residual Plots

The most accessible diagnostic method is the residual-versus-fitted plot. This graph plots the model's predicted (fitted) values on the x-axis against the residuals on the y-axis [5] [8].

- Protocol: After fitting an OLS regression model, calculate the residuals (

e_i = y_i - ŷ_i) and the fitted values (ŷ_i). Create a scatter plot with fitted values on the x-axis and residuals on the y-axis [8]. - Interpretation for Homoscedasticity: The residuals should be evenly dispersed around zero (the horizontal line) with no discernible systematic pattern. The spread of the points should remain roughly constant across all fitted values, forming a horizontal band [4] [5].

- Interpretation for Heteroscedasticity: A tell-tale sign is a fanning or cone-shaped pattern, where the spread of the residuals systematically increases (or decreases) as the fitted values increase [5] [6]. Other patterns, such as curves or clusters, can also indicate violation.

Formal Testing: The Breusch-Pagan Test

For objective, quantitative evidence, the Breusch-Pagan test is a widely used formal statistical test [1] [9].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Fit the Initial Model: Estimate the original regression model:

y_i = β_0 + β_1*x_{1i} + ... + β_p*x_{pi} + e_i[9]. - Calculate Squared Residuals: For each observation

i, compute the square of the residual,e_i²[9]. - Fit an Auxiliary Regression: Regress the squared residuals (

e_i²) on the original independent variables (x_{1i}, ..., x_{pi}). This model is:e_i² = γ_0 + γ_1*x_{1i} + ... + γ_p*x_{pi} + v_i[9]. - Compute Test Statistic: Calculate the test statistic as

LM = n * R²_aux, wherenis the sample size andR²_auxis the R-squared value from the auxiliary regression in step 3. Under the null hypothesis, this statistic follows a chi-square (χ²) distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of predictors (p) [9]. - Hypothesis Test:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): Homoscedasticity is present (error variance is constant) [9].

- Alternative Hypothesis (Hₐ): Heteroscedasticity is present (error variance is not constant) [9]. A p-value less than the chosen significance level (e.g., α = 0.05) leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis, confirming the presence of heteroscedasticity [9].

- Fit the Initial Model: Estimate the original regression model:

Table 2: Summary of Key Diagnostic Methods for Heteroscedasticity

| Method | Type | Underlying Principle | Key Output | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residual Plot [5] | Visual / Graphical | Scatter plot of residuals vs. fitted values. | A plot showing the distribution of residuals. | Homoscedasticity: Random scatter, constant spread. Heteroscedasticity: Systematic pattern (e.g., fan/cone shape). |

| Breusch-Pagan Test [9] | Formal Statistical Test | Auxiliary regression of squared residuals on predictors. | Lagrange Multiplier (LM) statistic and p-value. | p-value > α: Fail to reject H₀ (Homoscedasticity). p-value ≤ α: Reject H₀ (Heteroscedasticity). |

Correction and Mitigation Strategies

When heteroscedasticity is detected, several corrective measures are available. The choice of method depends on the nature of the data and the severity of the issue.

- Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Standard Errors: A popular modern solution, especially in econometrics, is to calculate robust standard errors, such as White's estimator [1] [3]. This method corrects the standard errors of the OLS coefficients without altering the coefficients themselves, allowing for valid hypothesis testing. This is often preferred over complex transformations as it is simpler to implement and avoids changing the model's interpretation [1].

- Data Transformation: Applying a transformation to the dependent variable can often stabilize the variance. Common transformations include the natural logarithm, square root, or inverse [1] [10] [7]. These transformations can help when the variance increases with the mean. For example, a log transformation can compress the scale of large values, reducing their disproportionate influence [10].

- Weighted Least Squares (WLS): WLS is a generalization of OLS used when observations have different variances. It operates by assigning a weight to each data point, typically inversely proportional to the variance of its error term [1] [5]. This down-weights the influence of observations with higher variance, leading to more efficient estimates. The challenge lies in correctly specifying the weights, which often requires knowledge or an estimate of how the variance changes with the independent variables [5].

- Redefining the Dependent Variable: In some contexts, particularly with cross-sectional data involving size or scale (e.g., city populations, company revenues), redefining the model in per capita or rate terms can naturally resolve heteroscedasticity [5]. For instance, instead of modeling the total number of accidents in a city, model the accident rate per capita [5]. This approach often improves model interpretability alongside fixing the variance issue.

For researchers implementing the diagnostics and corrections outlined in this guide, the following "research reagents" are essential. This toolkit comprises statistical software and specialized packages that facilitate the entire workflow, from model fitting to generating robust inferences.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analyzing Model Residuals

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python, Stata) | Software Environment | Provides the core computational engine for fitting regression models, calculating residuals, and performing transformations. Essential for all subsequent steps. |

| Visualization Package (e.g., ggplot2, matplotlib) | Software Library | Generates high-quality residual-versus-fitted plots and other diagnostic charts for visual inspection of homoscedasticity. |

lmtest Package (R) |

Statistical Library | Contains the bptest() function, which is a standard implementation of the Breusch-Pagan test for formal detection of heteroscedasticity [9]. |

sandwich Package (R) |

Statistical Library | Provides functions like vcovHC() for calculating heteroskedasticity-consistent (HC) covariance matrices, which are used to compute robust standard errors [3]. |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) Module | Algorithm | A standard feature in most statistical software (e.g., the weights argument in R's lm() function) for performing weighted regression to correct for known variance structures. |

Homoscedasticity is a fundamental assumption that underpins the reliability of inferences drawn from linear regression models. In the rigorous context of drug development and scientific research, ignoring the violation of this assumption—heteroscedasticity—can lead to false positives and unsupported conclusions. This whitepaper has articulated the theoretical distinction between these two states, detailed their critical implications for model validity, and provided a structured, practical framework for diagnosis and correction. By integrating visual diagnostics like residual plots with formal statistical tests such as the Breusch-Pagan test, researchers can robustly identify variance instability. Subsequently, employing remedies like robust standard errors, data transformations, or weighted least squares ensures the derivation of valid, trustworthy results. Mastery of these concepts and techniques is indispensable for any professional dedicated to building statistically sound and scientifically credible models.

Why Constant Residual Variance is a Key OLS Regression Assumption

Within the rigorous framework of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, the assumption of constant residual variance, or homoscedasticity, is foundational for deriving reliable inferences. This whitepaper delineates the theoretical and practical repercussions of violating this assumption—a condition known as heteroscedasticity—which is a pivotal concern in model residuals research. For professionals in drug development and scientific research, where models inform critical decisions, understanding and diagnosing heteroscedasticity is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of the assumption's role, the consequences of its violation, and robust methodologies for its validation and correction, thereby ensuring the integrity of statistical conclusions.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is the most common estimation method for linear models, prized for its ability to produce the best linear unbiased estimators (BLUE) when its underlying classical assumptions are met [11]. These assumptions collectively ensure that the coefficient estimates for the population parameters are unbiased and have the minimum variance possible, making them efficient and reliable [11] [12].

Among these core assumptions is the requirement of homoscedasticity—that the error term (the unexplained random disturbance in the relationship between independent and dependent variables) has a constant variance across all observations [11] [2]. The complementary concept, heteroscedasticity, describes a systematic pattern in the residuals where their variance is not constant but changes with the values of the independent variables or the fitted values [1] [13]. This violation, while not biasing the coefficient estimates themselves, fundamentally undermines the trustworthiness of the model's inference, a risk that is unacceptable in high-stakes fields like pharmaceutical research and scientific development.

Theoretical Underpinnings: Homoscedasticity vs. Heteroscedasticity

Defining the Core Concepts

- Homoscedasticity: Describes a situation where the variance of the error term is constant across all values of the independent variables. Formally, this is stated as

Var(ε_i | X) = σ², where σ² is a constant [1] [13]. In a homoscedastic model, the spread of the observed data points around the regression line is consistent, resembling a band of equal width [14]. - Heteroscedasticity: Occurs when the variance of the error term is non-constant, often depending on the values of the independent variables [1]. Visually, this manifests in residual plots where the spread of residuals forms patterns, such as a classic "cone" or "fan" shape, where the variability increases or decreases with the fitted values [11] [10].

The Gauss-Markov Theorem and Efficiency

The critical importance of homoscedasticity is enshrined in the Gauss-Markov theorem. This theorem states that when all OLS assumptions (including homoscedasticity and no autocorrelation) hold true, the OLS estimator is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) [11] [12]. "Best" in this context means it has the smallest variance among all other linear unbiased estimators, making it efficient [11]. When heteroscedasticity is present, this optimality is lost; while the OLS coefficient estimates remain unbiased, they are no longer efficient, as other estimators may exist with smaller variances [1] [15].

Consequences of Heteroscedasticity on Regression Inference

Violating the constant variance assumption has profound implications for the interpretation of a regression model, primarily affecting the precision and reliability of the inferred results.

Table 1: Consequences of Heteroscedasticity on OLS Regression Outputs

| Regression Component | Impact of Heteroscedasticity |

|---|---|

| Coefficient Estimates | Remain unbiased on average [1] [16]. However, they are no longer efficient, meaning they do not have the minimum possible variance [11] [1]. |

| Standard Errors | Become biased [2] [16]. The typical OLS formula for standard errors relies on a constant σ², which is incorrect under heteroscedasticity. |

| Confidence Intervals | Inaccurate [16] [14]. Biased standard errors lead to confidence intervals that are either too narrow or too wide, failing to capture the true parameter at the stated confidence level. |

| Hypothesis Tests (t-tests, F-tests) | Misleading [1] [14]. Inflated standard errors can lead to a failure to reject false null hypotheses (Type II errors), while deflated standard errors can cause false rejections of true null hypotheses (Type I errors). |

| Goodness-of-Fit (R²) | Potentially overestimated as the model may appear to explain more variance than it truly does [1]. |

The core issue is that OLS gives equal weight to all observations [2] [10]. In the presence of heteroscedasticity, observations with larger error variances exert more "pull" on the regression line, distorting the true underlying relationship and compromising the model's inferential power [2].

Diagnostic Methodologies: Detecting Non-Constant Variance

A systematic approach to diagnosing heteroscedasticity is crucial for researchers to validate their models.

Visual Diagnostics: Residual Plots

The most straightforward method is to visually inspect plots of the residuals [16] [14].

- Residuals vs. Fitted Values Plot: This is the primary diagnostic tool. After fitting a model, a scatterplot is created with the fitted (predicted) values on the x-axis and the residuals on the y-axis. If the constant variance assumption holds, the points should be randomly scattered without any discernible pattern, forming a roughly horizontal band around zero. A classic sign of heteroscedasticity is a fan or cone shape, where the spread of the residuals systematically increases or decreases with the fitted values [11] [16] [14].

- Residuals vs. Independent Variables: Similarly, plotting residuals against each independent variable can help identify if non-constant variance is linked to a specific predictor [16].

Formal Statistical Tests

For objective, quantitative assessment, several formal tests are available.

- Breusch-Pagan Test: This test involves an auxiliary regression of the squared residuals from the original model on the original independent variables. The test statistic is calculated as

n*R²from this auxiliary regression, which follows a chi-squared distribution. A significant p-value indicates evidence of heteroscedasticity [1] [13]. - White Test: A generalization of the Breusch-Pagan test, the White test regresses the squared residuals on the independent variables, their squares, and their cross-products. It is more general but consumes more degrees of freedom [1] [13].

- Goldfeld-Quandt Test: This test splits the data into two groups (often by ordering based on an independent variable suspected of causing heteroscedasticity) and compares the variance of the residuals from these two groups using an F-test [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Diagnostic Tests for Heteroscedasticity

| Test | Methodology | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Inspection | Plotting residuals vs. fitted values or predictors [16]. | Intuitive, easy to implement, reveals pattern of heteroscedasticity. | Subjective; may be difficult to interpret with small samples. |

| Breusch-Pagan (BP) | Auxiliary regression of squared residuals on X's [1] [13]. | Powerful for detecting linear forms of heteroscedasticity. | Sensitive to departures from normality [1]. |

| White Test | Auxiliary regression of squared residuals on X's, their squares, and cross-products [13]. | General, can detect nonlinear heteroscedasticity. | Can lose power due to many regressors in the auxiliary model. |

The following workflow provides a structured, diagnostic approach for researchers:

Corrective Measures and Robust Solutions

When heteroscedasticity is detected, researchers have several remedial options.

Heteroscedasticity-Consistent Standard Errors

A popular and straightforward solution, especially in econometrics, is to use heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors (HCSE), such as those proposed by White [1] [16] [13]. This method recalculates the standard errors of the coefficients using a modified formula that accounts for the heteroscedasticity, without altering the coefficient estimates themselves. This allows for valid hypothesis testing and confidence intervals while keeping the original OLS coefficients. This is often the preferred first step as it is easy to implement in modern statistical software [1].

Variable Transformation

Transforming the dependent variable can often stabilize the variance. Common variance-stabilizing transformations include:

- Logarithmic transformation:

Y_new = log(Y)[16] [14]. - Square root transformation:

Y_new = sqrt(Y)[2] [16]. - Inverse transformation:

Y_new = 1/Y[14]. These transformations, particularly the log, can help compress the scale of the data, reducing the influence of extreme values and mitigating heteroscedasticity [14].

Weighted Least Squares (WLS)

For cases where the form of heteroscedasticity is known or can be modeled, Weighted Least Squares (WLS) is a more efficient alternative to OLS [1] [13]. WLS assigns a weight to each data point, typically inversely proportional to the variance of its error term. Observations with higher variance (more "noise") are given less weight in determining the regression line. This method directly addresses the inefficiency of OLS under heteroscedasticity but requires knowledge or a model of the variance function [2] [13].

Redefining the Dependent Variable

In some contexts, it may be more meaningful to redefine the dependent variable. For instance, instead of modeling a raw count, one could model a rate (e.g., number of events per capita) [14] [10]. This can naturally account for scale differences that lead to heteroscedasticity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Robust Regression

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Diagnosing and Correcting Heteroscedasticity

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Residual vs. Fitted Plot | Primary visual diagnostic for identifying patterns of non-constant variance [16] [14]. | Mandatory first step in all regression diagnostic workflows. |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Formal statistical test for detecting heteroscedasticity linked to model predictors [1] [13]. | Objective verification after visual suspicion; requires normal errors for best performance. |

| White Test | More general formal test that can detect nonlinear heteroscedasticity [13]. | Used when the form of heteroscedasticity is unknown or complex. |

| White/HCSE Standard Errors | Corrects inference (p-values, CIs) without changing coefficient estimates [1] [16]. | The modern standard for obtaining robust inference in the presence of heteroscedasticity. |

| Log Transformation | Variance-stabilizing transformation for positive-valued, right-skewed data [16] [14]. | Applied to the dependent variable to reduce the influence of large values. |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) | Estimation technique that weights observations by the inverse of their error variance [1] [13]. | The most efficient solution if the pattern of heteroscedasticity is known and can be modeled. |

The assumption of constant residual variance is not a mere statistical technicality but a cornerstone of valid and efficient inference using OLS regression. In the context of scientific and drug development research, where models guide pivotal decisions, acknowledging the distinction between homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity is non-negotiable. While heteroscedasticity does not invalidate the unbiased nature of coefficient estimates, it systematically erodes the reliability of standard errors, confidence intervals, and hypothesis tests. Fortunately, a robust arsenal of diagnostic visualizations, formal tests, and corrective measures—from heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors to weighted least squares—exists to equip researchers. A diligent approach to testing this assumption and applying appropriate remedies ensures that the conclusions drawn from a regression model are both accurate and trustworthy.

In biomedical research, the statistical assumption of homoscedasticity—the consistency of error variance across observations—serves as a foundational requirement for valid inference in regression models. Violations of this assumption, termed heteroscedasticity, systematically undermine the reliability of hypothesis tests, confidence intervals, and prediction accuracy in critical research domains from genomics to clinical trial analysis [17]. This technical guide examines the pervasive challenge of heteroscedasticity through two prominent biomedical case studies: polygenic prediction of body mass index (BMI) and the analysis of treatment response heterogeneity in clinical interventions. Within the broader thesis on variance stability in model residuals, we demonstrate how heteroscedasticity not represents a mere statistical nuisance but rather reveals fundamental biological phenomena requiring specialized analytical approaches.

The implications of heteroscedasticity extend beyond statistical formalism to directly impact scientific interpretation and healthcare applications. When phenotypic variance changes systematically with genetic risk scores or treatment dosage, conventional regression analyses produce biased standard errors, inflate Type I error rates, and generate misleading conclusions about intervention efficacy [18]. Through structured protocols, quantitative comparisons, and diagnostic workflows presented herein, researchers can identify, quantify, and address variance heterogeneity to ensure both methodological rigor and biological validity in their investigations.

Foundational Concepts: Homoscedasticity versus Heteroscedasticity

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Homoscedasticity describes the scenario where the variance of regression residuals remains constant across all levels of explanatory variables, formally expressed as Var(ε_i) = σ² for all observations i [17]. This constant variance assumption ensures that ordinary least squares estimators achieve optimal efficiency properties, providing the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators under the Gauss-Markov theorem. Conversely, heteroscedasticity occurs when residual variance changes systematically with predicted values or specific covariates, potentially arising from omitted variable bias, nonlinear relationships, or measurement error heterogeneity [17].

In biomedical contexts, heteroscedasticity frequently manifests as variance changes across genetic risk strata or treatment dosage levels, reflecting underlying biological heterogeneity rather than mere statistical artifact. For instance, in BMI genomics, individuals with higher polygenic risk scores may exhibit greater phenotypic variability due to gene-environment interactions, creating a "fanning" pattern in residual distributions [18]. Similarly, in clinical trials, treatment response heterogeneity emerges when patient subgroups experience differential variability in outcomes beyond simple mean differences, complicating the interpretation of average treatment effects [19].

Consequences for Biomedical Inference

The inferential consequences of heteroscedasticity impact multiple aspects of biomedical research:

- Standard Error Estimation: Conventional standard errors become biased, typically downwardly, inflating Type I error rates and producing falsely precise estimates [17]

- Hypothesis Testing: Test statistics for treatment effects and association parameters follow incorrect sampling distributions, invalidating p-value interpretation

- Prediction Intervals: Uncertainty quantification becomes systematically biased, with prediction intervals either too narrow or too wide depending on the heteroscedastic pattern [18]

- Model Efficiency: Parameter estimates lose statistical efficiency, reducing power to detect genuine biological signals

These issues prove particularly problematic in precision medicine applications, where accurate characterization of individual-level variation directly impacts clinical decision-making [19].

Case Study 1: Heteroscedasticity in BMI Polygenic Prediction

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified hundreds of genetic variants associated with body mass index, enabling construction of polygenic scores (GPS) for obesity risk prediction. However, the assumption of constant BMI variance across genetic risk strata rarely holds in practice, creating analytical challenges for personalized risk assessment [18]. This case study examines heteroscedasticity in BMI prediction using UK Biobank data from 275,809 European-ancestry participants, with BMI as the continuous outcome variable and LDpred2-derived GPS as the primary predictor [18].

Table 1: Study Population Characteristics for BMI Polygenic Prediction Analysis

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N=344,761) | Test Set (N=68,952) | Validation Set (N=275,809) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.75 ± 7.98 | 56.77 ± 7.97 | 56.74 ± 7.98 |

| Sex (% Female) | 53.85% | 53.69% | 53.89% |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 27.38 ± 4.76 | 27.37 ± 4.77 | 27.29 ± 4.76 |

The analytical protocol proceeded through sequential phases: (1) GPS calculation using LDpred2 with BMI GWAS summary statistics; (2) residual variance analysis across GPS percentiles; (3) heteroscedasticity testing via Breusch-Pagan and Score tests; and (4) assessment of prediction accuracy under homoscedastic versus heteroscedastic subsamples [18].

Diagnostic Findings and Heteroscedasticity Detection

Graphical analysis revealed a systematic pattern of increasing BMI variance with higher GPS percentiles, contradicting the homoscedasticity assumption. Formal statistical testing confirmed this observation, with both Breusch-Pagan test (χ² = 37.2, p < 0.001) and Score test (χ² = 41.6, p < 0.001) rejecting the null hypothesis of constant variance [18]. This heteroscedastic pattern suggests that individuals with higher genetic predisposition to obesity exhibit greater phenotypic variability, potentially reflecting differential environmental sensitivity or gene-environment interactions.

To quantify the impact on prediction accuracy, researchers compared model performance between heteroscedastic samples and artificially constructed homoscedastic subsamples with restricted residual variance. The homoscedastic subsamples demonstrated significantly improved prediction accuracy (ΔR² = 0.12, p < 0.01), establishing a quantitative negative correlation between heteroscedasticity magnitude and prediction efficiency [18].

Methodological Protocols for BMI Variance Analysis

Diagram 1: Analytical Workflow for Detecting and Addressing BMI Heteroscedasticity

The experimental workflow for BMI heteroscedasticity analysis incorporates both diagnostic and remedial components. Following initial model specification, researchers employ visual diagnostics (residual plots) and formal statistical tests to quantify variance heterogeneity [17]. Subsequent steps investigate potential moderators of heteroscedasticity, including gene-environment interactions, while parallel analyses evaluate the consequences for prediction accuracy in homoscedastic versus heteroscedastic subsamples [18].

Case Study 2: Treatment Response Heterogeneity in Clinical Trials

Conceptual Framework and Causal Inference Challenges

Treatment response heterogeneity represents a specialized form of heteroscedasticity where variance in clinical outcomes differs systematically between intervention arms, potentially reflecting variable biological susceptibility to therapy. The fundamental challenge in quantifying true response heterogeneity lies in the causal inference framework: each patient possesses two potential outcomes (under treatment and control), but only one is observable [19]. This missing data structure precludes direct calculation of individual treatment effects and their variance.

Table 2: Contrasting Change versus Response in Clinical Trial Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Change in Outcome | Observed difference from baseline to follow-up within a single arm | Confounds treatment effect with natural history and regression to the mean |

| Treatment Response | Causal difference between potential outcomes under treatment versus control | Counterfactual nature prevents direct observation in individual patients |

| Apparent Heterogeneity | Variance in observed changes within treatment group | Includes both true response heterogeneity and natural variability |

| True Response Heterogeneity | Variance in individual causal treatment effects | Requires strong assumptions or specialized designs for estimation |

Traditional pre-post analyses fundamentally confuse change with response by implicitly assuming zero change under the counterfactual control condition. Randomized controlled trials with parallel control groups overcome this limitation by providing a population-level estimate of the average treatment effect, but characterizing the distribution of individual treatment effects remains methodologically challenging [19].

Bounding Approach for Heterogeneity Estimation

When individual treatment effects cannot be directly observed, researchers can bound the variance of treatment response using the observed variances in treatment and control groups. Given sample variances s²Y(T) and s²Y(C) in treatment and control groups respectively, the variance of individual treatment effects σ²_D satisfies the inequality:

(sY(T) - sY(C))² ≤ σ²D ≤ (sY(T) + s_Y(C))²

The lower bound corresponds to perfect positive correlation between potential outcomes, while the upper bound assumes perfect negative correlation [19]. In most clinical contexts, the correlation likely falls between 0 and 1, suggesting the true heterogeneity variance lies closer to the lower bound. An F-test for equal variances between treatment and control groups simultaneously tests the presence of treatment response heterogeneity, providing a practical diagnostic tool for clinical researchers [19].

Alternative Study Designs for Response Heterogeneity

Beyond conventional parallel-group RCTs, several specialized designs enhance capacity for investigating treatment response heterogeneity:

- Balaam's Design: Participants randomly assigned to receive (1) treatment then control, (2) control then treatment, (3) treatment only, or (4) control only, combining within-person and between-person comparisons

- N-of-1 Trials: Intensive repeated-measurement designs within individual patients, estimating person-specific treatment effects through crossover sequences

- Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trials (SMARTs): Adaptive designs that randomize non-responders to alternative treatments, directly characterizing response heterogeneity

Each design provides enhanced statistical leverage for estimating variance components associated with true treatment response heterogeneity, addressing fundamental limitations of standard parallel-group designs [19].

Diagnostic Methodologies and Statistical Protocols

Visual Diagnostic Tools

Residual plots serve as the primary visual tool for detecting heteroscedasticity, with distinct patterns suggesting different underlying mechanisms:

- Funnel Pattern: Expanding or contracting residual variance across the prediction range suggests variance correlation with outcome magnitude

- Dual/Multiple Clusters: Distinct residual groupings may indicate unmeasured categorical moderators or subgroup structure

- Systematic Bands: Regularly spaced residual patterns suggest rounding, measurement quantization, or threshold effects

In Python, residual plots can be generated through multiple implementations. The manual approach calculates residuals as residuals = y_actual - y_predicted followed by plt.scatter(y_predicted, residuals), while specialized functions like seaborn.residplot() automate both regression fitting and residual visualization [20]. For comprehensive regression diagnostics, statsmodels provides plot_regress_exog() which generates four-panel plots including residual dependence, Q-Q normality assessment, and leverage indicators [20].

Formal Statistical Testing

Formal hypothesis tests complement visual diagnostics by providing objective criteria for heteroscedasticity detection:

- Breusch-Pagan Test: Evaluates whether squared residuals show significant relationship with explanatory variables, with null hypothesis of constant variance [17] [18]

- White Test: A generalization that incorporates quadratic and interaction terms, more robust to model misspecification [17]

- Goldfeld-Quandt Test: Compares residual variances between data partitions, particularly effective for monotonic variance changes

- F-test for Equal Variances: Directly compares outcome variances between treatment and control groups in randomized trials [19]

Implementation typically involves fitting the primary regression model, extracting residuals, then applying specialized test functions from statistical packages like lmtest in R or statsmodels in Python [17] [18].

Remedial Methods and Variance Stabilization

When heteroscedasticity is detected, multiple analytical strategies can restore valid inference:

- Weighted Least Squares: Downweights high-variance observations using inverse variance weights (wi = 1/σ²i), particularly effective when variance patterns follow known covariates [17]

- Variance-Stabilizing Transformations: Logarithmic, square root, or Box-Cox transformations compress the measurement scale to equalize variance [17]

- Robust Standard Errors: Huber-White ("sandwich") estimators provide consistent inference despite heteroscedasticity, without altering point estimates [17]

- Bootstrap Resampling: Non-parametric approach that empirically estimates sampling distributions, inherently robust to variance heterogeneity [17]

Table 3: Variance Stabilization Techniques and Applications

| Technique | Mechanism | Biomedical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Box-Cox Transformation | Power transformation with optimal λ selection | Laboratory values with proportional measurement error |

| Logarithmic Scaling | Multiplicative to additive effect conversion | Biomarker concentrations spanning orders of magnitude |

| Weighted Least Squares | Inverse variance weighting | Known precision differences across measurement platforms |

| Huber-White Robust Errors | Asymptotically correct standard errors | Post-hoc correction of heteroscedasticity in completed studies |

| Bootstrap Resampling | Empirical sampling distribution estimation | Small samples with complex variance structure |

Statistical Software and Programming Tools

- R Statistical Environment: Comprehensive regression diagnostics through

lmtest,car, andsandwichpackages; specialized functions for Breusch-Pagan testing (bptest) and residual visualization [17] - Python SciPy Ecosystem:

statsmodelsfor regression diagnostics and heteroscedasticity tests;scikit-learnfor machine learning implementations with residual analysis [17] [20] - SAS PROC MODEL: Automated heteroscedasticity testing in enterprise clinical trial environments

- Stata Regression Diagnostics: Built-in commands for White test and weighted estimation

- UK Biobank Dataset: Large-scale genomic and phenotypic data enabling investigation of heteroscedasticity across genetic strata [18]

- LDpred2 Software: Polygenic score calculation with explicit modeling of genetic architecture [18]

- Rubin Causal Model Framework: Potential outcomes formalization for treatment response heterogeneity [19]

- N-of-1 Trial Design Protocols: Structured templates for single-patient crossover studies characterizing individual response variability [19]

Integrated Analytical Workflow for Biomedical Researchers

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Framework for Addressing Heteroscedasticity in Biomedical Research

The integrated workflow guides researchers from initial detection through biological interpretation of heteroscedasticity patterns. Following model estimation, systematic residual analysis determines whether observed variance heterogeneity requires remedial action. For confirmed cases, characterization of the specific variance pattern informs selection of appropriate methodological responses, ranging from data transformation to robust inference techniques. Throughout this process, maintaining connection to the underlying biomedical context ensures that statistical adjustments enhance rather than obscure biological understanding.

Heteroscedasticity in biomedical research transcends statistical technicality to represent meaningful biological heterogeneity with direct implications for scientific interpretation and clinical application. The case studies presented—BMI polygenic prediction and treatment response heterogeneity—demonstrate how variance patterns systematically influence prediction accuracy and causal inference across diverse research domains. Through rigorous application of the diagnostic protocols, remedial methods, and analytical workflows outlined in this technical guide, researchers can transform variance heterogeneity from a statistical obstacle into a biological insight opportunity, advancing both methodological rigor and scientific understanding in precision medicine.

In statistical modeling, particularly in regression analysis and the analysis of variance, the nature of the variance in model residuals—specifically, whether they are homoscedastic or heteroscedastic—has profound implications for the validity of research conclusions. Homoscedasticity denotes a scenario where the variance of the error terms (residuals) is constant across all levels of the independent variables; formally, Var(u_i|X_i=x) = σ² for all observations i=1,…,n [3]. This property is a foundational assumption of the classical linear regression model. Conversely, heteroscedasticity exists when the variance of the error terms is not constant but depends on the values of the independent variables; that is, Var(u_i|X_i=x) = σ_i² [1] [3]. Homoscedasticity can thus be considered a special case of the more general heteroscedastic condition [3].

Understanding this distinction is not merely a technical formality. The presence of heteroscedasticity invalidates statistical tests of significance that assume a constant error variance, leading directly to the two core problems highlighted in this paper: biased standard errors and inflated Type I error rates [1] [21]. This is a critical concern in fields like drug development and psychopathology research, where random assignment to treatment or condition groups is often unfeasible or unethical, and observed data frequently exhibit inherent variability [21].

Core Consequences of Heteroscedasticity

Biased Standard Errors and the Breakdown of the Gauss-Markov Theorem

When the assumption of homoscedasticity is violated, the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator retains the property of being unbiased; that is, on average, it still accurately estimates the true population regression coefficients [1]. However, it ceases to be efficient. This means that among all linear unbiased estimators, OLS no longer has the smallest variance [1]. Consequently, the Gauss-Markov theorem, which guarantees that OLS is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) under its assumptions, no longer applies [1].

The most immediate practical consequence is that the standard formulas used to estimate the standard errors of the regression coefficients become biased. These conventional formulas, which assume a single, constant error variance (σ²), are derived under the homoscedasticity assumption. When this assumption is false, the estimated standard errors are incorrect [1] [3]. The direction of this bias is not always predictable; it can lead to standard errors that are either systematically too large or too small compared to the true variability of the estimator [1]. This bias in standard error estimation is the primary gateway to more severe inferential errors.

Inflated Type I Error Rates and Compromised Hypothesis Testing

A Type I error occurs when a researcher incorrectly rejects a true null hypothesis (a false positive). The probability of making a Type I error is denoted by alpha (α), typically set at 0.05. Biased standard errors directly undermine this probability.

If heteroscedasticity causes the standard errors to be underestimated, the resulting t-statistics and F-statistics become artificially inflated. This makes effects appear statistically significant when they are not. Consequently, the actual Type I error rate can become substantially inflated above the nominal alpha level [21]. For instance, a test conducted at a nominal α of 0.05 might have an actual Type I error rate of 0.10 or higher, meaning the researcher has a 10% or greater chance of falsely declaring a significant effect.

This issue is a major concern in psychopathology research and other observational fields. As noted in one review, the misuse of models like ANCOVA, which are vulnerable to this bias when covariates are correlated with the independent variable and measured with error, is prevalent and often occurs without researchers showing awareness of the problem [21]. The ultimate risk is that models with heteroscedastic errors can lead to a failure to reject a null hypothesis that is actually untrue (a Type II error) when standard errors are overestimated, or, more alarmingly, a heightened risk of false positives (inflated Type I error) when standard errors are underestimated [1].

Table 1: Consequences of Ignoring Heteroscedasticity on OLS Estimation and Inference

| Aspect | Under Homoscedasticity | Under Heteroscedasticity (if ignored) |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient Estimate (β) | Unbiased | Remains Unbiased |

| Efficiency | Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) | Not Efficient |

| Standard Error Estimate | Consistent | Biased (can be over or under-estimated) |

| t-statistics / F-statistics | Valid | Invalid Distribution |

| Type I Error Rate | Controlled at nominal level (e.g., 5%) | Inflated or Deflated |

| Confidence Intervals | Valid Coverage | Invalid Coverage (too narrow or too wide) |

Detection and Diagnostic Methodologies

Before corrective measures can be applied, researchers must first diagnose the presence of heteroscedasticity. Several established experimental protocols and statistical tests are available for this purpose.

Visual Inspection: The First Line of Defense

A simple yet effective initial diagnostic is the visual inspection of residuals.

- Procedure: Plot the regression residuals (or the squared residuals) against the predicted values of the dependent variable or against the independent variables suspected of driving the heteroscedasticity.

- Interpretation: Under homoscedasticity, the spread of residuals should be roughly constant across all values of the predictor (forming a random band around zero). A systematic pattern in the spread—such as a funnel or cone shape where the variability increases or decreases with the predicted value—is a classic visual indicator of heteroscedasticity [3].

Formal Statistical Testing

Visual evidence should be supplemented with formal hypothesis tests.

- Breusch-Pagan Test: This is a common test for heteroscedasticity. It operates by conducting an auxiliary regression of the squared OLS residuals on the original independent variables. The test statistic is derived from the explained sum of squares from this auxiliary regression and follows a chi-squared distribution under the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity [1].

- Koenker-Bassett Test: Also known as the generalized Breusch-Pagan test, this test is often preferred because it is more robust to departures from the normality assumption of the errors [1].

The logical workflow for diagnosing heteroscedasticity is summarized in the diagram below.

Correction Protocols and Robust Solutions

Once heteroscedasticity is detected, researchers must employ methodologies that yield valid inference. The following protocols are standard in the scientific toolkit.

Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Standard Errors

The most common correction in modern econometrics and related fields is to use Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Standard Errors (HCSE), also known as Eicker-Huber-White standard errors [1] [3].

- Methodology: This technique involves computing a new estimator for the variance-covariance matrix of the coefficients that does not assume a constant error variance. The formula accounts for the individual squared residuals

û_i²of each observation, providing a consistent estimate of the standard errors even in the presence of heteroscedasticity [3]. - Implementation: In practice, this is easily implemented in statistical software (e.g., the

vcovHCfunction in R). The key advantage is that it corrects the standard errors without altering the original OLS coefficient estimates. Therefore, researchers can obtain reliable t-statistics and confidence intervals for their unbiased coefficient estimates [3].

Generalized Least Squares

An alternative approach is Generalized Least Squares.

- Methodology: GLS transforms the original regression model to create a new model whose errors are homoscedastic. This is typically achieved by weighting each observation by the inverse of the estimated standard deviation of its error term (i.e.,

1/σ_i). If the form of heteroscedasticity is known or can be accurately modeled, GLS is efficient and BLUE [1]. - Caveat: A significant drawback is that GLS can exhibit strong bias in small samples if the skedastic function (the model for the variance) is misspecified. For this reason, HCSE are often the preferred standard practice in many disciplines [1].

Data Transformation and Weighted Least Squares

For specific types of data, other transformations may be effective.

- Stabilizing Transformations: Applying a non-linear transformation to the dependent variable, such as the natural logarithm, can sometimes stabilize the variance. This is particularly relevant for data that exhibit exponential growth and thus increasing variability [1].

- Weighted Least Squares: WLS is a special case of GLS where each observation is weighted by a factor, often the inverse of the variance of the dependent variable within a group or a function of an independent variable. This is a formalized way of giving less weight to observations with higher variance [1].

Table 2: Summary of Key Correction Methods for Heteroscedasticity

| Method | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCSE | Recomputes standard errors\nusing a robust formula | Does not change coefficients;\neasy to implement; consistent. | Standard errors are only asymptotically valid; can be biased in small samples. |

| GLS | Transforms model to have\nhomoscedastic errors | Efficient if variance structure\nis correctly specified. | Can be strongly biased if the form of\nheteroscedasticity is misspecified. |

| WLS | Weights observations by\ninverse of their variance | Can be more powerful than\nHCSE if weights are correct. | Requires knowledge or a good estimate\nof how variance changes. |

| Data Transformation | Applies a function (e.g., log)\nto the dependent variable | Can normalize the data and\nstabilize variance. | Interpretation of coefficients\nbecomes non-linear. |

The decision-making process for selecting and applying these corrections is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust Inference

To effectively implement the methodologies described, researchers should be familiar with the following essential "reagents" in their statistical toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Heteroscedasticity Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| OLS Regression | Provides unbiased coefficient estimates and raw residuals for initial diagnosis. | lm(y ~ x1 + x2, data = mydata) in R |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Formal diagnostic test for the presence of heteroscedasticity. | bptest(model) in R (from lmtest package) |

| White/HCSE Estimator | Computes heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors for reliable inference. | coeftest(model, vcov = vcovHC(model, type="HC1")) in R (using sandwich & lmtest) |

| GLS/WLS Estimator | Fits a model that directly accounts for heteroscedasticity in the estimation. | gls(y ~ x1 + x2, weights = varPower(), data = mydata) in R (from nlme package) |

| Data Visualization | Creates residual plots for visual diagnostics of heteroscedasticity. | plot(fitted(model), resid(model)) in R |

Within the broader thesis on model residuals, the distinction between homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity is far from academic. The consequences of ignoring heteroscedasticity—specifically, biased standard errors and inflated Type I error rates—pose a direct and severe threat to the validity of scientific research. This is especially critical in high-stakes fields like drug development and psychopathology, where false positives can misdirect resources and policy. While OLS estimates remain unbiased, the accompanying inference is rendered unreliable. Fortunately, a robust toolkit of diagnostic methods, such as the Breusch-Pagan test and residual analysis, and corrective solutions, primarily HCSE, are readily available. Integrating these checks and corrections into the standard research workflow is an essential practice for ensuring the integrity and reproducibility of scientific findings.

This technical guide examines the critical distinction between pure and impure heteroscedasticity within the broader context of homoscedasticity versus heteroscedasticity in model residuals research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this dichotomy is essential for developing accurate statistical models and drawing valid scientific conclusions. Heteroscedasticity—the non-constant variance of error terms in regression models—can either reflect innate data characteristics (pure) or result from model specification errors (impure). This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of both phenomena, including detection methodologies, corrective approaches, and specialized applications in scientific research, with particular relevance to dose-response studies in toxicology and pharmacology.

Heteroscedasticity describes the circumstance where the variance of residuals in a regression model is not constant across the range of measured values, instead displaying unequal variability across a set of predictor variables [22] [23]. This phenomenon directly contravenes the assumption of homoscedasticity required by ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, wherein error terms maintain constant variance [22]. The term itself originates from ancient Greek roots: "hetero" meaning "different" and "skedasis" meaning "dispersion" [22].

In scientific research, particularly in drug development and biomedical studies, recognizing and addressing heteroscedasticity is crucial because it violates fundamental assumptions of many statistical procedures. When heteroscedasticity exists, the population used in regression contains unequal variance, potentially rendering analysis results invalid [23]. The Gauss-Markov theorem no longer applies, meaning OLS estimators are not the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE), and their variance is not the lowest of all other unbiased estimators [22]. This ultimately compromises statistical tests of significance that assume modeling errors all share the same variance [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts of Variance in Regression Models

| Concept | Definition | Implications for Statistical Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Homoscedasticity | Constant variance of residuals across all levels of independent variables [24] | Satisfies OLS assumptions, valid standard errors, reliable hypothesis tests [22] |

| Heteroscedasticity | Non-constant variance of residuals across the range of independent variables [23] | Inefficient parameter estimates, biased standard errors, compromised significance tests [22] [25] |

| Pure Heteroscedasticity | Non-constant variance persists even with correct model specification [22] | Requires variance-stabilizing transformations or alternative estimation methods [22] [26] |

| Impure Heteroscedasticity | Non-constant variance resulting from model misspecification [22] | Requires model respecification through added variables or corrected functional forms [22] [27] |

Theoretical Framework: Pure versus Impure Heteroscedasticity

Pure Heteroscedasticity

Pure heteroscedasticity refers to cases where the model is correctly specified with the appropriate independent variables, yet the residual plots still demonstrate non-constant variance [22] [23]. This form arises from the inherent data structure itself rather than from analytical errors. The variability in error terms is intrinsic to the phenomenon under study and would persist even in a perfectly specified model.

This innate variability often emerges from the natural heterogeneity of populations studied in biomedical research. For instance, in toxicological studies, the variability in response may not be constant across dose groups due to biological factors including the bioassay, dose-spacing, and the endpoint of interest [26]. Similarly, models involving a wide range of values are more prone to pure heteroscedasticity because the relative differences between small and large values can be substantial [22] [23].

Impure Heteroscedasticity

Impure heteroscedasticity occurs when an incorrect model specification causes non-constant variance in the residual plots [22] [23]. This typically results from omitted variables, incorrect functional forms, or measurement errors [27] [25]. When relevant variables are excluded from a model, their unexplained effects are absorbed into the error term, potentially producing patterns of heteroscedasticity if these omitted effects vary across the observed data range [22].

The distinction between pure and impure heteroscedasticity is critically important because the corrective strategies differ substantially [22]. For impure heteroscedasticity, the solution involves identifying and correcting the specification error, whereas pure heteroscedasticity requires specialized estimation techniques that account for the innate variance structure.

Diagram 1: Heteroscedasticity Classification and Solutions

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Graphical Detection Approaches

The initial detection of heteroscedasticity typically involves visual inspection of residual plots, which provides an intuitive understanding of data variability [24]. Researchers create scatterplots of residuals against fitted values or independent variables and examine the patterns [22] [25]. A funnel-shaped pattern—where the spread of residuals systematically widens or narrows across the range of values—indicates heteroscedasticity [24] [28]. In contrast, a consistent, uniform band of points suggests homoscedasticity [24].

This visual approach is particularly valuable in biomedical research where researchers can quickly assess the variance structure before proceeding to formal statistical testing. For example, in studying the effects of a new drug on blood pressure, plotting residuals against drug dosage may reveal whether variability changes with dosage levels [24].

Formal Statistical Tests

When visual inspection suggests potential heteroscedasticity, researchers should employ formal statistical tests to objectively confirm its presence. The most commonly used tests include:

Breusch-Pagan Test: This test examines whether squared residuals are related to independent variables [22] [25]. The procedure involves:

- Fitting an OLS regression and computing residuals

- Regressing squared residuals on all independent variables

- Calculating test statistic: BP = n × R², where n is sample size and R² from auxiliary regression

- Comparing against chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to number of independent variables

White Test: A more general approach that detects both heteroscedasticity and model specification errors [27] [25]. The protocol includes:

- Fitting original OLS regression and computing residuals

- Running auxiliary regression of squared residuals on all independent variables, their squares, and cross-products

- Calculating test statistic: W = n × R²

- Comparing against chi-square distribution

Goldfeld-Quandt Test: Particularly useful when heteroscedasticity is suspected relative to a specific variable [22] [25]. The methodology involves:

- Sorting data by the suspected variable

- Dividing data into two groups, omitting central observations

- Running separate regressions on each group

- Computing F-statistic = (RSS₂/df₂)/(RSS₁/df₁), where RSS is residual sum of squares

- Comparing F-statistic to critical values from F-distribution

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Heteroscedasticity Detection

| Test | Underlying Principle | Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breusch-Pagan | Regresses squared residuals on independent variables [25] | General regression settings | Simple implementation, direct interpretation | Assumes specific form of heteroscedasticity |

| White Test | Regresses squared residuals on independent variables, their squares, and cross-products [27] [25] | Detection of both heteroscedasticity and specification errors | Comprehensive, no assumption on heteroscedasticity form | Consumes degrees of freedom with many variables |

| Goldfeld-Quandt | Compares variance ratios between data subsets [22] [25] | Suspected monotonic variance relationship with a specific variable | Intuitive F-test framework | Requires prior knowledge of problematic variable |

| Visual Residual Analysis | Examines patterns in residual plots [24] | Preliminary screening | Simple, intuitive, requires no assumptions | Subjective interpretation, cannot prove absence |

Corrective Approaches and Estimation Techniques

Addressing Impure Heteroscedasticity

For impure heteroscedasticity resulting from model misspecification, the primary corrective approach involves model respecification [22] [27]. Researchers should:

- Identify omitted variables through theoretical reasoning and exploratory data analysis, then incorporate them into the model [27]

- Test alternative functional forms (non-linear transformations) if the relationship between variables appears mispecified [27]

- Address measurement errors through improved instrumentation or statistical control [25]

These approaches target the root cause of impure heteroscedasticity by improving the model structure itself rather than merely addressing the symptomatic variance issues.

Addressing Pure Heteroscedasticity

When heteroscedasticity persists in correctly specified models, several specialized techniques can mitigate its effects:

Data Transformation: Applying mathematical functions to stabilize variance [24] [25]. Common transformations include:

- Logarithmic transformation: y' = ln(y) [22] [25]

- Square root transformation: y' = √y [25] [28]

- Box-Cox transformation: A flexible power transformation that estimates optimal parameters [27]

Weighted Least Squares (WLS): This approach assigns different weights to observations based on their variance [25]. Observations with higher variance receive lower weights, reducing their influence on parameter estimates. The weight for each observation is typically: wi = 1/σi², where σ_i² is the estimated variance [25].

Heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors: Also known as robust standard errors, this approach adjusts inference without altering coefficient estimates [22] [24]. Methods like White's estimator provide valid standard errors, confidence intervals, and hypothesis tests despite heteroscedasticity [22] [25].

Weighted M-estimation: In toxicological research with common outliers, this robust approach combines M-estimation with weighting to handle both heteroscedasticity and influential observations [26].

Diagram 2: Decision Framework for Addressing Heteroscedasticity

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Dose-Response Modeling

In toxicology and pharmacology, researchers frequently use nonlinear regression models like the Hill model to describe dose-response relationships [26]. The Hill model is expressed as: y = θ₀ + θ₁x^θ₂/(θ₃^θ₂ + x^θ₂) + ε, where y represents response at dose x, θ₀ is the intercept, θ₁ is the difference between maximum effect and intercept, θ₂ is the slope parameter, and θ₃ is ED₅₀ (drug concentration producing 50% of maximum effect) [26].

In such models, heteroscedasticity frequently occurs because variability in response may not be constant across dose groups [26]. This heteroscedasticity can significantly impact parameter estimation. For example, simulation studies demonstrate that different estimation approaches (OLS vs. IWLS) produce substantially different ED₅₀ estimates when heteroscedasticity exists [26].

Advanced Methodologies for Biomedical Data

The Preliminary Test Estimation (PTE) methodology addresses uncertainty about error variance structure by selecting an appropriate estimation procedure based on a preliminary test for heteroscedasticity [26]. This approach uses either ordinary M-estimation (OME) or weighted M-estimation (WME) depending on the test outcome, making it robust to both heteroscedasticity and outliers common in toxicological data [26].

M-estimation utilizes Huber score functions to minimize the influence of outliers while maintaining estimation efficiency [26]. The Huber function is defined as:

- h(u) = u/2, if |u| < k₀

- h(u) = {k₀(|u| - k₀/2)}¹/², otherwise where k₀ is a pre-specified constant (typically 1.5) [26].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Heteroscedasticity Analysis

| Tool/Software | Application Context | Key Functionality | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statsmodels (Python) | Regression analysis and statistical testing [28] | Breusch-Pagan test, White test, robust standard errors | Quantile regression for heteroscedastic social media data [28] |

| PyMC (Python) | Bayesian statistical modeling [28] | Conditional variance modeling via probabilistic programming | Modeling mean and variance as functions of inputs [28] |

| R Statistical Software | Comprehensive statistical analysis [25] | Weighted least squares, M-estimation, variance function estimation | Implementing PTE for dose-response models [26] |

| Huber M-Estimator | Robust regression with outliers [26] | Minimizing influence of extreme observations | Toxicological data analysis with influential points [26] |

| Sklearn QuantileRegression | Machine learning with heteroscedastic data [28] | Predicting conditional quantiles rather than means | Modeling engagement-follower relationships [28] |

Distinguishing between pure and impure heteroscedasticity represents a critical step in developing valid statistical models for scientific research. While both forms manifest as non-constant variance in residuals, their underlying causes and corrective strategies differ substantially. Impure heteroscedasticity stems from model misspecification and requires diagnostic respecification, whereas pure heteroscedasticity reflects innate data patterns demanding specialized estimation techniques.

For drug development professionals and biomedical researchers, acknowledging this distinction is particularly important in domains like dose-response modeling, where heteroscedasticity can significantly impact parameter estimation and consequent scientific conclusions. By implementing appropriate detection protocols and corrective methodologies outlined in this technical guide, researchers can enhance the reliability of their statistical inferences and advance the rigor of scientific investigations across multiple domains.

Detecting Heteroscedasticity: Visual and Statistical Diagnostics in Practice

In the validation of regression models, the analysis of residuals—the differences between observed and predicted values—is a critical diagnostic procedure. This examination is central to the debate between homoscedasticity and heteroscedasticity, a fundamental concept determining the reliability of statistical inferences [10]. Homoscedasticity describes a situation where the variance of the residuals is constant across all levels of an independent variable [10]. In contrast, heteroscedasticity refers to a systematic change in the spread of these residuals over the range of measured values, often visualized as a classic fan or cone shape in residual plots [29]. The presence of this pattern indicates a violation of a key assumption of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, which can render the results of an analysis untrustworthy by, for instance, increasing the likelihood of declaring a term statistically significant when it is not [29]. This paper provides an in-depth technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals on identifying, understanding, and remediating this specific form of model inadequacy.

Theoretical Framework: Homoscedasticity vs. Heteroscedasticity

Foundational Concepts

- Residuals: In regression analysis, a residual is defined as the difference between an observed value and the value predicted by the model (

Residual = Observed – Predicted) [30]. These residuals contain valuable clues about the model's performance and are essential for diagnosing potential problems [31] [32]. - Homoscedasticity: This is the ideal condition for OLS regression. It means that the variance of the error terms (residuals) is constant across all levels of the independent variables [10]. In a well-behaved residual plot, this manifests as a random scatter of points, evenly distributed around the horizontal axis at zero, with no discernible systematic pattern [33] [34] [35].

- Heteroscedasticity: This occurs when the size of the error term differs across the values of an independent variable [10]. It represents a systematic change in the spread of the residuals, making the results of a regression analysis hard to trust [29]. While it doesn't cause bias in the model's coefficient estimates, it reduces their precision, leading to incorrect p-values and unreliable inferences [33] [10].

Consequences for Statistical Inference

The core problem with heteroscedasticity lies in its impact on the statistical tests that underpin regression analysis. OLS regression assumes homoscedasticity, and when this assumption is violated, the standard errors of the regression coefficients become biased [32]. Specifically:

- Inflated Variance: Heteroscedasticity increases the variance of the regression coefficient estimates, but the model itself fails to account for this [10] [29].

- Compromised Hypothesis Testing: The biased standard errors lead to invalid t-statistics and F-statistics. This means that confidence intervals and hypothesis tests become unreliable. A researcher may conclude that a variable is a significant predictor when it is not (a Type I error), or fail to detect a significant effect that is truly present (a Type II error) [33].

Table 1: Comparison of Homoscedasticity and Heteroscedasticity

| Feature | Homoscedasticity | Heteroscedasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Constant variance of residuals | Non-constant variance of residuals |

| Visual Pattern | Random scatter around zero | Fan, cone, or other systematic shape |

| Impact on Coefficients | Unbiased estimates | Unbiased but inefficient estimates |

| Impact on Standard Errors | Accurate | Biased (often underestimated) |

| Impact on Inference | Reliable hypothesis tests | Unreliable p-values and confidence intervals |

Identifying the Fan or Cone Shape

Visual Diagnosis

The primary method for detecting heteroscedasticity is visual inspection of a residual plot. The most common and useful plot is the fitted values vs. residuals plot, where the predicted values from the model are on the x-axis and the residuals are on the y-axis [31] [29].

- The Ideal Plot: A residual plot that satisfies the homoscedasticity assumption will show residuals randomly scattered around the horizontal line at zero. The spread of the points will be roughly the same across the entire range of fitted values, forming a horizontal band with no obvious structure [33] [30] [35].

- The Classic Fan/Cone: Heteroscedasticity is indicated when the residuals fan out or form a cone shape as the fitted values increase (or decrease) [10] [29]. For example, the plot may start narrow for small predicted values and become wider for larger predicted values. This pattern signifies that the variance is not constant and is a function of the predicted value [31] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the diagnostic workflow for identifying heteroscedasticity from a residual plot.

Common Scenarios and Examples

Heteroscedasticity often occurs naturally in datasets with a wide range of observed values [29]. Consider these classic examples:

- Income vs. Expenditure: For individuals with lower incomes, variability in expenditures is low, as money is spent primarily on necessities. For high-income individuals, variability is much greater, as some spend lavishly while others are frugal, creating a fan-shaped pattern [10] [29].

- City Population vs. Number of Businesses: Small towns may uniformly have few businesses (low variability). Large cities, however, can have a wide range in the number of businesses, leading to greater variability in the residuals for larger fitted values [10] [29].

- Age vs. Income: Younger people's incomes tend to cluster near the minimum wage, showing low variability. As age increases, the variability in income expands significantly, creating a cone-shaped residual plot [10].

Methodological Protocols for Detection and Analysis

Experimental Workflow for Residual Analysis

A rigorous approach to diagnosing heteroscedasticity involves both graphical and formal testing methods. The following protocol ensures a comprehensive assessment.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for the Researcher's Toolkit

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitted vs. Residual Plot | Graphical | Primary visual tool for identifying patterns like the fan/cone shape. | ||

| Scale-Location Plot | Graphical | Plots √( | Residuals | ) vs. Fitted Values to make trend identification easier. |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Statistical Test | Formal hypothesis test for detecting heteroscedasticity. | ||

| Goldfeld-Quandt Test | Statistical Test | Another formal test, useful when the variance increases with a specific variable. | ||

| Weighted Least Squares | Remedial Algorithm | A regression method that assigns weights to data points to address non-constant variance. |