Hyperparameter Tuning in Cheminformatics: A Practical Guide for Accelerating Drug Discovery

This guide provides cheminformatics researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing hyperparameter tuning to enhance the predictive performance of machine learning models.

Hyperparameter Tuning in Cheminformatics: A Practical Guide for Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This guide provides cheminformatics researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing hyperparameter tuning to enhance the predictive performance of machine learning models. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, it explores why hyperparameters are critical for tasks like molecular property prediction and binding affinity forecasting. The content details established and modern optimization techniques, from Grid Search to Bayesian methods, and addresses common pitfalls like overfitting. Through validation strategies and comparative analysis of real-world case studies, this article demonstrates how systematic hyperparameter optimization can lead to more reliable, efficient, and interpretable models, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

Why Hyperparameters Matter: The Foundation of Robust Cheminformatics Models

Defining Hyperparameters vs. Model Parameters in a Chemical Context

In the field of chemical informatics, the development of robust machine learning (ML) models is paramount for accelerating drug discovery, predicting molecular properties, and designing novel compounds. The performance of these models hinges on two fundamental concepts: model parameters and hyperparameters. Understanding their distinct roles is a critical first step in constructing effective predictive workflows. Model parameters are the internal variables that the model learns directly from the training data, such as the weights in a neural network. In contrast, hyperparameters are external configuration variables whose values are set prior to the commencement of the training process and control the very nature of that learning process [1] [2]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these concepts, framed within the practical context of hyperparameter tuning for chemical informatics research.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Distinctions

Model Parameters: The Learned Variables

Model parameters are variables that a machine learning algorithm estimates or learns from the provided training data. They are intrinsic to the model and are essential for making predictions on new, unseen data [1] [2].

- Definition: A configuration variable that is internal to the model and whose value is estimated from the training data.

- Key Characteristics:

- Learned from Data: Their values are derived by optimizing an objective function (e.g., minimizing loss via algorithms like Gradient Descent or Adam) [1].

- Not Set Manually: Researchers do not directly specify parameter values; they are a consequence of the training process.

- Make Predictions Possible: The final learned parameters define the model's representation of the underlying data patterns, enabling it to make predictions [1].

- Examples in Common Models:

Hyperparameters: The Controlling Knobs

Hyperparameters are the configuration variables that govern the training process itself. They are set before the model begins learning and cannot be learned directly from the data [1] [4].

- Definition: An external configuration variable whose value is set before the learning process begins.

- Key Characteristics:

- Set Before Training: Their values are chosen by the researcher prior to initiating model training [1].

- Control Model Training: They influence how the model parameters are learned, impacting the speed, efficiency, and ultimate quality of the training [1].

- Estimated via Tuning: Optimal hyperparameters are found through systematic experimentation and optimization techniques, known as hyperparameter tuning (HPO) [1] [4].

- Categories of Hyperparameters [2]:

- Architecture Hyperparameters: Control the structure of the model (e.g., number of layers in a Neural Network, number of neurons per layer, number of trees in a Random Forest).

- Optimization Hyperparameters: Control the optimization process (e.g., learning rate, number of iterations/epochs, batch size).

- Regularization Hyperparameters: Help prevent overfitting (e.g., strength of L1/L2 regularization, dropout rate).

The table below provides a consolidated comparison of model parameters and hyperparameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Model Parameters and Hyperparameters

| Aspect | Model Parameters | Model Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Internal variables learned from data | External configurations set before training |

| Purpose | Make predictions on new data | Estimate model parameters effectively and control training |

| Determined By | Optimization algorithms (e.g., Gradient Descent) | The researcher via hyperparameter tuning [1] |

| Set Manually | No | Yes |

| Examples | Weights & biases in Neural Networks; Coefficients in Linear Regression | Learning rate; Number of epochs; Number of layers & neurons; Number of clusters (k) [1] |

Hyperparameters and Parameters in a Chemical Context

The theoretical distinction between hyperparameters and parameters becomes critically important when applied to concrete problems in cheminformatics, such as predicting molecular properties.

Case Study: Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Property Prediction

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), such as ChemProp, have emerged as a powerful tool for modeling molecular structures. In these models, atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph [5] [6].

- Model Parameters in GNNs: These are the weights and biases within the message-passing neural network. They determine how information from an atom and its neighbors is aggregated and transformed to learn a meaningful representation of the entire molecule. These values are learned during training to minimize the error in predicting properties like solubility or toxicity [1] [6].

- Hyperparameters in GNNs: These are the architectural and optimization choices made before training, such as the number of message-passing steps (which defines the depth of the network and the "radius" of atomic interactions), the size of the hidden layers, the learning rate, and the dropout rate for regularization [5] [7]. The performance of GNNs is highly sensitive to these choices, making their optimization a non-trivial task [5].

A Practical Example: Solubility Prediction

A recent study on solubility prediction highlights the practical implications of hyperparameter tuning. Researchers found that while hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is common, an excessive search across a large parameter space can lead to overfitting on the validation set used for tuning. In some cases, using a set of sensible, pre-optimized hyperparameters yielded similar model performance to a computationally intensive grid optimization (requiring ~10,000 times more resources), but with a drastic reduction in computational effort [8]. This underscores that HPO, while powerful, must be applied judiciously to avoid overfitting and inefficiency.

Table 2: Examples of Parameters and Hyperparameters in Cheminformatics Models

| Model / Algorithm | Model Parameters (Learned from Data) | Key Hyperparameters (Set Before Training) |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (e.g., ChemProp) | Weights and biases in graph convolution and fully connected layers [1] | Depth (message-passing steps), hidden layer size, learning rate, dropout rate [5] [7] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Coefficients defining the optimal separating hyperplane [3] | Kernel type (e.g., RBF), regularization strength (C), kernel-specific parameters (e.g., gamma) [3] |

| Random Forest | The structure and decision rules of individual trees | Number of trees, maximum depth of trees, number of features considered for a split |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Weights and biases between all connected neurons [1] [9] | Number of hidden layers, number of neurons per layer, learning rate, activation function, batch size [9] |

Methodologies for Hyperparameter Optimization (HPO)

Selecting the right hyperparameters is both an art and a science. Several algorithms and methodologies have been developed to systematize this process.

Common HPO Algorithms

- Grid Search: An exhaustive search over a predefined set of hyperparameter values. It is guaranteed to find the best combination within the grid but can be computationally prohibitive for a large number of hyperparameters [4].

- Random Search: Randomly samples hyperparameter combinations from defined distributions. It is often more efficient than grid search, as it can discover good configurations without exploring the entire space [4].

- Bayesian Optimization: A more sophisticated sequential approach that builds a probabilistic model of the function mapping hyperparameters to model performance. It uses this model to select the most promising hyperparameters to evaluate next, typically requiring fewer iterations to find a good optimum [4] [10].

- Hyperband: An algorithm that focuses on computational efficiency by leveraging early-stopping. It uses a multi-fidelity approach, running a large number of configurations for a small budget (e.g., few epochs) and only continuing the most promising ones for longer training. A study on molecular property prediction found Hyperband to be the most computationally efficient algorithm, providing optimal or near-optimal results [4].

Advanced Workflow: Mitigating Overfitting in Low-Data Regimes

In chemical research, datasets are often small. A workflow implemented in the ROBERT software addresses overfitting by using a specialized objective function during Bayesian hyperparameter optimization. This function combines:

- Interpolation Performance: Measured via a standard 10-times repeated 5-fold cross-validation (CV).

- Extrapolation Performance: Assessed via a sorted 5-fold CV that tests the model's ability to predict data at the extremes of the target value range [10].

This combined metric ensures that the selected hyperparameters produce a model that generalizes well not only to similar data but also to slightly novel scenarios, a common requirement in chemical exploration [10].

Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

Detailed Methodology: HPO for a DNN in Molecular Property Prediction

The following protocol, adapted from a study on optimizing deep neural networks (DNNs), provides a step-by-step methodology [4]:

- Problem Definition: Define the molecular property to be predicted (e.g., glass transition temperature, Tg) and the input features (e.g., molecular descriptors or fingerprints).

- Data Preprocessing: Clean the data, handle missing values, and standardize or normalize the features. Split the data into training, validation, and test sets.

- Base Model Definition: Establish a baseline DNN architecture (e.g., an input layer, 3 hidden layers with 64 neurons each using ReLU activation, and an output layer with linear activation) and a base optimizer (e.g., Adam).

- Select HPO Algorithm and Software: Choose an HPO algorithm (e.g., Hyperband) and a software platform that supports parallel execution (e.g., KerasTuner).

- Define the Search Space: Specify the range of hyperparameters to be explored:

- Number of hidden layers: 1 - 5

- Number of neurons per layer: 16 - 128

- Learning rate: 0.0001 - 0.1 (log scale)

- Dropout rate: 0.0 - 0.5

- Batch size: 16, 32, 64

- Execute HPO: Run the HPO process, where the tuner will train and evaluate numerous model configurations on the training/validation sets.

- Evaluate Best Model: Retrieve the best hyperparameter configuration found by the tuner, train a final model on the combined training and validation data, and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HPO in Cheminformatics

Table 3: Key Software and Libraries for Hyperparameter Tuning in Cheminformatics

| Tool / Library | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| KerasTuner [4] | A user-friendly, intuitive hyperparameter tuning library that integrates seamlessly with TensorFlow/Keras workflows. | Ideal for tuning DNNs and CNNs for molecular property prediction; allows parallel execution. |

| Optuna [4] | A define-by-run hyperparameter optimization framework that supports various samplers (like Bayesian optimization) and pruners (like Hyperband). | Suitable for more complex and customized HPO pipelines, including combining Bayesian Optimization with Hyperband (BOHB). |

| ChemProp [6] | A message-passing neural network specifically designed for molecular property prediction. | Includes built-in functionality for hyperparameter tuning, making it a top choice for graph-based molecular modeling. |

| ROBERT [10] | An automated workflow program for building ML models from CSV files, featuring Bayesian HPO with a focus on preventing overfitting. | Particularly valuable for working with small chemical datasets common in research. |

Visualizing the Relationship and Workflow

Conceptual Relationship

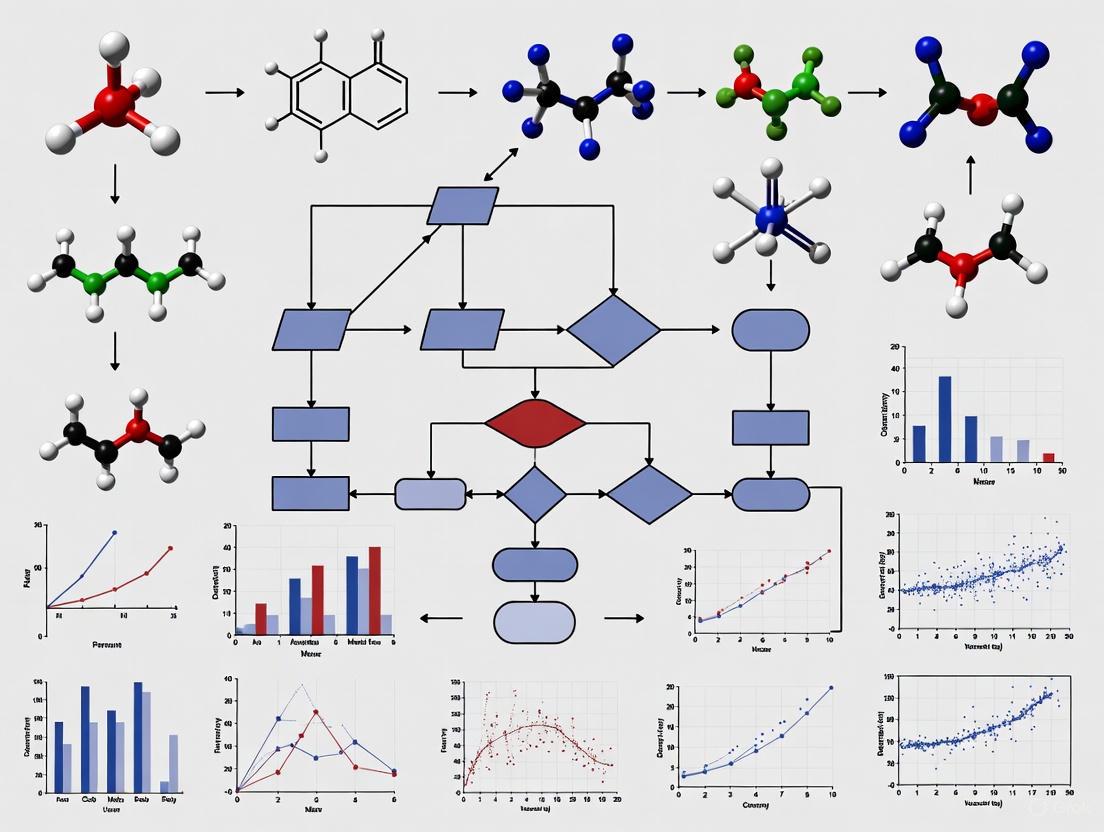

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between data, hyperparameters, and model parameters in the machine learning workflow.

Hyperparameter Optimization Workflow

This diagram outlines a generalized workflow for optimizing hyperparameters in a cheminformatics project.

A precise understanding of the distinction between model parameters and hyperparameters is a cornerstone of effective machine learning in chemical informatics. Model parameters are the essence of the learned model, while hyperparameters are the guiding hands that shape the learning process. As evidenced by research in solubility prediction and molecular property modeling, the careful and sometimes restrained application of hyperparameter optimization is critical for developing models that are both accurate and generalizable. By leveraging modern HPO algorithms like Hyperband and Bayesian optimization within specialized frameworks, researchers can systematically navigate the complex hyperparameter space, thereby building more predictive and reliable models to accelerate scientific discovery in chemistry and drug development.

Core Hyperparameters for Key Cheminformatics Algorithms (GNNs, Transformers, etc.)

In the interdisciplinary field of cheminformatics, where computational methods are applied to solve chemical and biological problems, machine learning has revolutionized traditional approaches to molecular property prediction, drug discovery, and material science [5]. The performance of sophisticated deep learning algorithms like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformers in these tasks is highly sensitive to their architectural choices and parameter configurations [5]. Hyperparameter tuning—the process of selecting the optimal set of values that control the learning process—has thus emerged as a critical step in developing effective cheminformatics models. Unlike model parameters learned during training, hyperparameters are set before the training process begins and govern fundamental aspects of how the model learns [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals working with chemical data, mastering hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is essential for building models that can accurately predict molecular properties, generate novel compounds, and ultimately accelerate scientific discovery.

Core Hyperparameters in Deep Learning

Hyperparameters in deep learning can be categorized into two primary groups: core hyperparameters that are common across most neural network architectures, and architecture-specific hyperparameters that are particularly relevant to specific model types like GNNs or Transformers [11].

Universal Deep Learning Hyperparameters

The following table summarizes the core hyperparameters that influence nearly all deep learning models in cheminformatics:

Table 1: Core Hyperparameters in Deep Learning for Cheminformatics

| Hyperparameter | Impact on Learning Process | Typical Values/Ranges | Cheminformatics Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | Controls step size during weight updates; too high causes divergence, too slow causes slow convergence [11] | 1e-5 to 1e-2 | Critical for stability when learning from limited chemical datasets |

| Batch Size | Number of samples processed before weight updates; affects gradient stability and generalization [11] | 16, 32, 64, 128 | Smaller batches may help escape local minima in molecular optimization |

| Number of Epochs | Complete passes through training data; too few underfits, too many overfits [11] | 50-1000 (dataset dependent) | Early stopping often necessary with small molecular datasets |

| Optimizer | Algorithm for weight updates (e.g., SGD, Adam, RMSprop) [11] | Adam, SGD with momentum | Adam often preferred for molecular property prediction tasks |

| Activation Function | Introduces non-linearity (e.g., ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid) [11] | ReLU, GELU, Swish | Choice affects gradient flow in deep molecular networks |

| Dropout Rate | Fraction of neurons randomly disabled to prevent overfitting [11] | 0.1-0.5 | Essential for regularization with limited compound activity data |

| Weight Initialization | Sets initial weight values before training [11] | Xavier, He normal | Proper initialization prevents vanishing gradients in deep networks |

Hyperparameter Tuning Techniques

Several systematic approaches exist for navigating the complex hyperparameter space in deep learning:

Grid Search: Exhaustively tries all combinations of predefined hyperparameter values. While thorough, it becomes computationally prohibitive for models with many hyperparameters or large datasets [12]. For example, tuning a CNN for image data might test learning rates [0.001, 0.01, 0.1] with batch sizes [16, 32, 64], resulting in 9 combinations to train and evaluate [11].

Random Search: Randomly samples combinations from defined distributions, often more efficient than grid search for high-dimensional spaces [11] [12]. For a deep neural network for text classification, random search might sample dropout rates between 0.2-0.5 and learning rates from 1e-5 to 1e-2 from log-uniform distributions [11].

Bayesian Optimization: Builds a probabilistic model of the objective function to guide the search toward promising regions, balancing exploration and exploitation [11] [12]. This approach is particularly valuable for cheminformatics applications where model training is computationally expensive and time-consuming [11].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for hyperparameter optimization in cheminformatics:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in Cheminformatics

GNN Applications and Hyperparameter Challenges

Graph Neural Networks have emerged as a powerful tool for modeling molecular structures in cheminformatics, naturally representing molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [5]. This representation allows GNNs to learn from structural information in a manner that mirrors underlying chemical properties, making them particularly valuable for molecular property prediction, chemical reaction modeling, and de novo molecular design [5]. However, GNN performance is highly sensitive to architectural choices and hyperparameters, making optimal configuration selection a non-trivial task that often requires automated Neural Architecture Search (NAS) and Hyperparameter Optimization (HPO) approaches [5].

Key GNN Hyperparameters

Table 2: Key Hyperparameters for Graph Neural Networks in Cheminformatics

| Hyperparameter | Impact on Model Performance | Common Values | Molecular Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of GNN Layers | Determines receptive field and message-passing steps; too few underfits, too many may cause over-smoothing [5] | 2-8 | Deeper networks needed for complex molecular properties |

| Hidden Dimension Size | Controls capacity to learn atom and bond representations [5] | 64-512 | Larger dimensions capture finer chemical details |

| Message Passing Mechanism | How information is aggregated between nodes (e.g., GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE) [5] | GCN, GAT, MPNN | Choice affects ability to capture specific molecular interactions |

| Readout Function | Aggregates node embeddings into graph-level representation [5] | Mean, Sum, Attention | Critical for molecular property prediction tasks |

| Graph Pooling Ratio | For hierarchical pooling methods; controls compression at each level [5] | 0.5-0.9 | Determines resolution of structural information retained |

| Attention Heads (GAT) | Multiple attention mechanisms to capture different bonding relationships [5] | 4-16 | More heads can model diverse atomic interactions |

Transformer Models in Cheminformatics

Transformer Applications for Molecular Data

Transformer models have gained significant traction in cheminformatics due to their ability to process sequential molecular representations like SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) and SELFIES, as well as their emerging applications in molecular graph processing [13] [14] [15]. The self-attention mechanism in Transformers enables them to identify complex relationships between molecular substructures, making them particularly valuable for tasks such as molecular property prediction, molecular optimization, and de novo molecular design [13] [16]. For odor prediction, for instance, Transformer models have been used to investigate structure-odor relationships by visualizing attention mechanisms to identify which molecular substructures contribute to specific odor descriptors [13].

Key Transformer Hyperparameters

Table 3: Key Hyperparameters for Transformer Models in Cheminformatics

| Hyperparameter | Impact on Model Performance | Common Values | Molecular Sequence Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Attention Heads | Parallel attention layers learning different aspects of molecular relationships [11] | 8-16 | More heads capture diverse substructure relationships |

| Number of Transformer Layers | Defines model depth and capacity for complex pattern recognition [11] | 4-12 | Deeper models needed for complex chemical tasks |

| Embedding Dimension | Size of vector representations for atoms/tokens [11] | 256-1024 | Larger dimensions capture richer chemical semantics |

| Feedforward Dimension | Hidden size in position-wise feedforward networks [11] | 512-4096 | Affects model capacity and computational requirements |

| Warm-up Steps | Gradually increases learning rate in early training [11] | 1,000-10,000 | Stabilizes training for molecular language models |

| Attention Dropout | Prevents overfitting in attention weights [11] | 0.1-0.3 | Regularization for limited molecular activity data |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hyperparameter Optimization for Drug Design

Recent research has demonstrated innovative frameworks integrating Transformers with many-objective optimization for drug design. One comprehensive study compared two latent Transformer models (ReLSO and FragNet) on molecular generation tasks and evaluated six different many-objective metaheuristics based on evolutionary algorithms and particle swarm optimization [16]. The experimental protocol involved:

Molecular Representation: Using SELFIES representations for molecular generation to guarantee validity of generated molecules, and SMILES for ADMET prediction to match base model implementation [16].

Model Architecture Comparison: Fair comparative analysis between ReLSO and FragNet Transformer architectures, with ReLSO demonstrating superior performance in terms of reconstruction and latent space organization [16].

Many-Objective Optimization: Implementing a Pareto-based many-objective optimization approach handling more than three objectives simultaneously, including ADMET properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) and binding affinity through molecular docking [16].

Evaluation Framework: Assessing generated molecules based on binding affinity, drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SAS), and other physio-chemical properties [16].

The study found that multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on dominance and decomposition performed best in finding molecules satisfying multiple objectives, demonstrating the potential of combining Transformers and many-objective computational intelligence for drug design [16].

Meta-Learning for Low-Data Molecular Optimization

For low-data scenarios common in early-phase drug discovery, meta-learning approaches have shown promise for predicting potent compounds using Transformer models. The experimental methodology typically involves:

Base Model Architecture: Adopting a transformer architecture designed for predicting highly potent compounds based on weakly potent templates, functioning as a chemical language model (CLM) [17].

Meta-Learning Framework: Implementing model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) that learns parameter settings across individual tasks and updates them across different tasks to enable effective adaptation to new prediction tasks with limited data [17].

Task Distribution: For each activity class, dividing training data into support sets (for model updates) and query sets (for evaluating prediction loss) [17].

Fine-Tuning: For meta-testing, fine-tuning the trained meta-learning module on specific activity classes with adjusted parameters [17].

This approach has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in model performance, particularly when fine-tuning data were limited, and generated target compounds with higher potency and larger potency differences between templates and targets [17].

The following diagram illustrates the meta-learning workflow for molecular optimization:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Cheminformatics Hyperparameter Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES/SELFIES | String-based molecular representations | Input format for Transformer models [16] |

| Molecular Graphs | Node (atom) and edge (bond) representations | Native input format for GNNs [5] |

| IUPAC Names | Human-readable chemical nomenclature | Alternative input for chemical language models [18] |

| ADMET Predictors | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity profiling | Key objectives in drug design optimization [16] |

| Molecular Docking | Predicting ligand-target binding affinity | Objective function in generative drug design [16] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit for molecular manipulation | Compound standardization, descriptor calculation [18] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Probabilistic hyperparameter search | Efficient HPO for computationally expensive models [11] [12] |

| Meta-Learning Frameworks | Algorithms for low-data regimes | Few-shot learning for molecular optimization [17] |

Hyperparameter optimization represents a critical component in the development of effective deep learning models for cheminformatics applications. As demonstrated throughout this guide, the optimal configuration of hyperparameters for GNNs and Transformers significantly influences model performance in key tasks such as molecular property prediction, de novo molecular design, and drug discovery. The interplay between architectural choices and hyperparameter settings necessitates systematic optimization approaches, particularly as models grow in complexity and computational requirements. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these tuning techniques—from foundational methods like grid and random search to more advanced approaches like Bayesian optimization and meta-learning—is essential for leveraging the full potential of deep learning in chemical informatics. As the field continues to evolve, automated optimization techniques are expected to play an increasingly pivotal role in advancing GNN and Transformer-based solutions in cheminformatics, ultimately accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

The Direct Impact of Tuning on Model Accuracy and Generalization

In chemical informatics research, machine learning (ML) has become indispensable for molecular property prediction (MPP), a task critical to drug discovery and materials design [4]. However, the performance of these models is profoundly influenced by hyperparameters—configuration settings that govern the training process itself. These are distinct from model parameters (e.g., weights and biases) that are learned from data [4]. Hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is the systematic process of finding the optimal set of these configurations. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering HPO is not a minor technical detail but a fundamental practice to ensure models achieve their highest possible accuracy and can generalize reliably to new, unseen chemical data. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the direct impact of tuning on model performance, framed within practical chemical informatics applications.

Hyperparameter Tuning: Core Concepts for Chemical Informatics

The Criticality of HPO in Molecular Property Prediction

The landscape of ML in chemistry is evolving beyond the use of default hyperparameters. Latest research findings emphasize that HPO is a key step for building models that can lead to significant gains in model performance [4]. This is particularly true for deep neural networks (DNNs) applied to MPP, where the relationship between molecular structure and properties is complex and high-dimensional. A comparative study on predicting polymer properties demonstrated that HPO could drastically improve model accuracy, as summarized in Table 1 [4].

Table 1: Impact of HPO on Deep Neural Network Performance for Molecular Property Prediction

| Molecular Property | Model Type | Performance without HPO | Performance with HPO | Reference Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melt Index (MI) of HDPE | Dense DNN | Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 0.132 | MAE: 0.022 | MAE (lower is better) |

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | MAE: 0.245 | MAE: 0.155 | MAE (lower is better) |

The consequences of neglecting HPO are twofold. First, it results in suboptimal predictive accuracy, wasting the potential of valuable experimental and computational datasets [4]. Second, it can impair a model's generalizability, meaning it will perform poorly when presented with new molecular scaffolds or conditions outside its narrow training regime. As noted in a recent methodology paper, "hyperparameter optimization is often the most resource-intensive step in model training," which explains why it has often been overlooked in prior studies, but its impact is too substantial to ignore [4].

Categories of Hyperparameters

For chemical informatics researchers, the hyperparameters requiring optimization can be broadly categorized as follows [4]:

- Structural Hyperparameters: These define the architecture of the neural network.

- Number of layers and neurons per layer.

- Type of activation function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid).

- Number of filters in a convolutional layer.

- Algorithmic Hyperparameters: These govern the learning process itself.

- Learning rate (arguably the most important single hyperparameter).

- Batch size and number of training epochs (iterations).

- Choice of optimizer (e.g., Adam, SGD) and its parameters.

- Regularization techniques like dropout rate and weight decay to prevent overfitting.

HPO Methodologies: Algorithms and Comparative Performance

Selecting the right HPO algorithm is crucial for balancing computational efficiency with the quality of the final model. Below is a summary of the primary strategies available.

Table 2: Comparison of Hyperparameter Optimization Algorithms

| HPO Algorithm | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | Exhaustive search over a predefined set of values | Simple, guaranteed to find best point in grid | Computationally intractable for high-dimensional spaces | Small, low-dimensional hyperparameter spaces |

| Random Search | Randomly samples hyperparameters from distributions | More efficient than grid search; good for high-dimensional spaces | May miss optimal regions; no learning from past trials | Initial explorations and moderately complex spaces |

| Bayesian Optimization | Builds a probabilistic surrogate model to guide search | High sample efficiency; learns from prior evaluations | Computational overhead for model updates; complex implementation | Expensive-to-evaluate models (e.g., large DNNs) |

| Hyperband | Uses adaptive resource allocation and early-stopping | High computational efficiency; good for large-scale problems | Does not guide sampling like Bayesian methods | Large-scale hyperparameter spaces with varying budgets |

| BOHB (Bayesian Opt. & Hyperband) | Combines Bayesian optimization with the Hyperband framework | Simultaneously efficient and sample-effective | More complex to set up and run | Complex models where both efficiency and accuracy are critical |

Based on recent comparative studies for MPP, the Hyperband algorithm is highly recommended due to its computational efficiency, often yielding optimal or nearly optimal results much faster than other methods [4]. For the highest prediction accuracy, BOHB (a combination of Bayesian Optimization and Hyperband) represents a powerful, state-of-the-art alternative [4].

Advanced Tuning: Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning Foundation Models

In data-sparse chemical domains, a powerful strategy is to leverage atomistic foundation models (FMs). These are large-scale models, such as MACE-MP, MatterSim, and ORB, pre-trained on vast and diverse datasets of atomic structures (e.g., the Materials Project) to learn general, fundamental geometric relationships [19] [20]. The process of adapting these broadly capable models to a specific, smaller downstream task (like predicting the property of a novel drug-like molecule) is known as fine-tuning or transfer learning.

Frozen Transfer Learning: A Data-Efficient Fine-Tuning Protocol

A highly effective fine-tuning technique is transfer learning with partially frozen weights and biases, also known as "frozen transfer learning" [19]. This method involves taking a pre-trained FM and freezing (keeping fixed) the parameters in a portion of its layers during training on the new, target dataset. The workflow for this process, which can be efficiently managed using platforms like MatterTune [20], is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Frozen Transfer Learning Workflow

This protocol offers two major advantages:

- Data Efficiency: It prevents catastrophic forgetting of general knowledge acquired during pre-training and allows the model to specialize using very small datasets. For instance, fine-tuning a MACE-MP foundation model with frozen layers (MACE-freeze) achieved state-of-the-art accuracy using only 10-20% of a target dataset—hundreds of data points—compared to the thousands required to train a model from scratch [19].

- Performance Retention: The frozen layers retain robust, transferable feature embeddings from the broad pre-training data. One study found that fine-tuning with four frozen layers (MACE-MP-f4) achieved force prediction accuracy on a challenging hydrogen/copper surface dataset that matched or exceeded a model trained from scratch on the full dataset [19].

Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

Detailed Methodology for HPO of a DNN

The following is a step-by-step protocol for optimizing a DNN for molecular property prediction using the KerasTuner library with the Hyperband algorithm, as validated in recent literature [4].

Problem Formulation and Data Preprocessing

- Define the MPP Task: Clearly specify the target property (e.g., solubility, binding affinity, glass transition temperature).

- Compile and Clean Dataset: Assemble a dataset of molecules with associated property values. Handle missing values and outliers appropriately.

- Featurize Molecules: Convert molecular structures into a numerical representation (e.g., molecular descriptors, fingerprints, or graph-based features).

- Split Data: Partition the data into training, validation, and test sets. The validation set is used by the HPO algorithm to evaluate performance.

Define the Search Space and Model-Building Function

- The search space is the range of hyperparameters the HPO algorithm will explore.

- Example Hyperparameter Ranges:

- Number of dense layers:

Int('num_layers', 2, 8) - Units per layer:

Int('units', 32, 256, step=32) - Learning rate:

Choice('learning_rate', [1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4]) - Dropout rate:

Float('dropout', 0.1, 0.5)

- Number of dense layers:

- Create a function that builds and compiles a DNN model given a set of hyperparameters from the search space.

Configure and Execute the HPO Run

- Instantiate Tuner: Configure the Hyperband tuner, specifying the objective (e.g.,

val_mean_absolute_error) and maximum number of epochs per trial. - Run the Search: Execute the tuner, which will automatically train and evaluate numerous model configurations (trials). The tuner uses early-stopping to halt underperforming trials, a key to Hyperband's efficiency.

- Leverage Parallelization: Use a platform like KerasTuner that allows for parallel execution of trials to drastically reduce total optimization time [4].

- Instantiate Tuner: Configure the Hyperband tuner, specifying the objective (e.g.,

Retrain and Evaluate the Best Model

- Retrieve Best Hyperparameters: Once the search is complete, query the tuner for the best-performing set of hyperparameters.

- Train Final Model: Use the best hyperparameters to train a model on the combined training and validation data.

- Report Final Performance: Evaluate this final model on the held-out test set to obtain an unbiased estimate of its generalization error.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software and data resources essential for modern hyperparameter tuning and model training in chemical informatics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Model Tuning

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Chemical Informatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| KerasTuner [4] | Software Library | User-friendly HPO (Hyperband, Bayesian) | Simplifies HPO for DNNs on MPP tasks; ideal for researchers without extensive CS background. |

| Optuna [4] | Software Library | Advanced, define-by-run HPO | Offers greater flexibility for complex search spaces and BOHB algorithm. |

| MatterTune [20] | Software Framework | Fine-tuning atomistic foundation models | Standardizes and simplifies the process of adapting FMs (MACE, MatterSim) to downstream tasks. |

| MACE-MP Foundation Model [19] [20] | Pre-trained Model | Universal interatomic potential & feature extractor | Provides a powerful, pre-trained starting point for force field and property prediction tasks. |

| Materials Project (MPtrj) [19] | Dataset | Large-scale database of crystal structures & properties | Serves as the pre-training dataset for many FMs, enabling their broad transferability. |

Hyperparameter tuning is not an optional refinement but a core component of the machine learning workflow in chemical informatics. As demonstrated, the direct impact of systematic HPO is a dramatic increase in model accuracy and robustness, transforming a poorly performing model into a powerful predictive tool. Furthermore, the emergence of atomistic foundation models and data-efficient fine-tuning protocols like frozen transfer learning offers a paradigm shift, enabling high-accuracy modeling even in data-sparse regimes common in early-stage drug and materials development. By integrating these tuning methodologies—from foundational HPO algorithms to advanced transfer learning—researchers can fully leverage their valuable data, accelerating the discovery and development of novel chemical entities and materials.

Hyperparameter tuning represents a critical step in developing robust and predictive machine learning (ML) models for chemical informatics. However, this process is profoundly influenced by the quality and characteristics of the underlying data. Researchers frequently encounter three interconnected data challenges that complicate model development: small datasets common in experimental chemistry, class imbalance in bioactivity data, and experimental error in measured endpoints. These issues are particularly pronounced in drug discovery applications where data generation is costly and time-consuming. This technical guide examines these data challenges within the context of hyperparameter tuning, providing practical methodologies and solutions to enhance model performance and reliability in chemical informatics research.

Navigating the Small Data Regime in Chemical ML

The Small Data Challenge in Chemistry

Chemical ML often operates in low-data regimes due to the resource-intensive nature of experimental work. Datasets of 20-50 data points are common in areas like reaction optimization and catalyst design [10]. In these scenarios, traditional deep learning approaches struggle with overfitting, and multivariate linear regression (MVL) has historically prevailed due to its simplicity and robustness [10]. However, properly tuned non-linear models can now compete with or even surpass linear methods when appropriate regularization and validation strategies are implemented.

Automated Workflows for Small Data

Recent research has demonstrated that specialized ML workflows can effectively mitigate overfitting in small chemical datasets. The ROBERT software exemplifies this approach with its automated workflow that incorporates Bayesian hyperparameter optimization using a combined root mean squared error (RMSE) metric [10]. This metric evaluates both interpolation (via 10-times repeated 5-fold cross-validation) and extrapolation performance (via selective sorted 5-fold CV) to identify models that generalize well beyond their training data [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms on Small Chemical Datasets (18-44 Data Points)

| Dataset | Size (Points) | Best Performing Algorithm | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 19 | Non-linear (External Test) | Non-linear models matched or outperformed MVL in half of datasets |

| D | 21 | Neural Network | Competitive performance achieved with 21 data points |

| F | 44 | Non-linear | Non-linear algorithms superior for external test sets |

| H | 44 | Neural Network | Non-linear models captured chemical relationships similarly to linear |

Foundation Models for Tabular Data

The emergence of tabular foundation models like Tabular Prior-data Fitted Network (TabPFN) offers promising alternatives for small-data scenarios. TabPFN uses a transformer-based architecture pre-trained on millions of synthetic datasets to perform in-context learning on new tabular problems [21]. This approach significantly outperforms gradient-boosted decision trees on datasets with up to 10,000 samples while requiring substantially less computation time for hyperparameter optimization [21].

Small Data ML Workflow: Automated pipeline for handling small chemical datasets.

Strategies for Imbalanced Data in Chemical Classification

The Prevalence and Impact of Imbalance

Imbalanced data presents a fundamental challenge across chemical informatics applications, particularly in drug discovery where active compounds are significantly outnumbered by inactive ones in high-throughput screening datasets [22] [23]. This imbalance leads to biased models that exhibit poor predictive performance for the minority class (typically active compounds), ultimately limiting their utility in virtual screening campaigns [23].

Resampling Techniques and Their Applications

Multiple resampling strategies have been developed to address data imbalance, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Oversampling techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) generate new minority class samples by interpolating between existing instances [22]. Advanced variants include Borderline-SMOTE, which focuses on samples near class boundaries, and SVM-SMOTE, which uses support vector machines to identify important regions for oversampling [22].

Undersampling approaches reduce the majority class to balance dataset distribution. Random undersampling (RUS) removes random instances from the majority class, while NearMiss uses distance metrics to selectively retain majority samples [24]. Recent research indicates that moderate imbalance ratios (e.g., 1:10) rather than perfect balance (1:1) may optimize virtual screening performance [24].

Table 2: Performance of Resampling Techniques on PubChem Bioassay Data

| Resampling Method | HIV Dataset (IR 1:90) | Malaria Dataset (IR 1:82) | Trypanosomiasis Dataset | COVID-19 Dataset (IR 1:104) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (Original) | MCC: -0.04 | Moderate performance across metrics | Worst performance across metrics | High accuracy but misleading |

| Random Oversampling (ROS) | Boosted recall, decreased precision | Enhanced balanced accuracy & recall | Improved vs. original | Highest balanced accuracy |

| Random Undersampling (RUS) | Best MCC & F1-score | Best MCC values & F1-score | Best overall performance | Significant recall improvement |

| SMOTE | Limited improvements | Similar to original data | Moderate improvement | Highest MCC & F1-score |

| ADASYN | Limited improvements | Highest precision | Moderate improvement | Highest precision |

| NearMiss | Highest recall | Highest recall, low other metrics | Moderate performance | Significant recall improvement |

Paradigm Shift in Evaluation Metrics

Traditional QSAR modeling practices emphasizing balanced accuracy and dataset balancing require reconsideration for virtual screening applications. For hit identification in ultra-large libraries, models with high positive predictive value (PPV) built on imbalanced training sets outperform balanced models [23]. In practical terms, training on imbalanced datasets achieves hit rates at least 30% higher than using balanced datasets when evaluating top-ranked compounds [23].

Imbalance Solutions Taxonomy: Classification of methods for handling imbalanced chemical data.

Accounting for Experimental Error and Variability

The Impact of Experimental Error on Model Validation

Experimental measurements in chemistry inherently contain error, which propagates into ML models and affects both training and validation. For biochemical assays, measurement errors of +/- 3-fold are not uncommon and must be considered when interpreting model performance differences [25]. Traditional statistical comparisons that ignore this experimental uncertainty may identify "significant" differences that lack practical relevance.

Robust Validation Protocols

Proper validation methodologies account for both model variability and experimental error:

Repeated Cross-Validation: 5x5-fold cross-validation (5 repetitions of 5-fold CV) provides more stable performance estimates than single train-test splits [25]. This approach mitigates the influence of random partitioning on performance metrics.

Statistical Significance Testing: Tukey's Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test with confidence interval plots enables robust model comparisons while accounting for multiple testing [25]. This method visually identifies models statistically equivalent to the best-performing approach.

Paired Performance Analysis: Comparing models across the same cross-validation folds using paired t-tests provides more sensitive discrimination of performance differences [25]. This approach controls for dataset-specific peculiarities that might favor one algorithm over another.

Integrated Hyperparameter Tuning Frameworks

Bayesian Optimization with Integrated Validation

Advanced hyperparameter tuning frameworks for chemical ML must address multiple data challenges simultaneously. Bayesian optimization with Gaussian process surrogates effectively navigates hyperparameter spaces while incorporating specialized validation strategies [10] [26]. The integration of a combined RMSE metric during optimization—accounting for both interpolation and extrapolation performance—has proven particularly effective for small datasets [10].

LLM-Enhanced Bayesian Optimization

Emerging frameworks like Reasoning BO enhance traditional Bayesian optimization by incorporating large language models (LLMs) for improved sampling and hypothesis generation [26]. This approach leverages domain knowledge encoded in language models to guide the optimization process, achieving significant performance improvements in chemical reaction optimization tasks [26]. For direct arylation reactions, Reasoning BO increased yields to 60.7% compared to 25.2% with traditional BO [26].

Pre-selected Hyperparameters for Small Data

For particularly small datasets, extensive hyperparameter optimization may be counterproductive due to overfitting. Recent research suggests that using pre-selected hyperparameters can produce models with similar or better accuracy than grid optimization for architectures like ChemProp and Attentive Fingerprint [7]. This approach reduces the computational burden while maintaining model quality.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Small Dataset Modeling

ROBERT Workflow Implementation:

- Data Curation: Input CSV database containing molecular structures and target properties

- Automated Splitting: Reserve 20% of data (minimum 4 points) as external test set with even distribution of target values

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Bayesian optimization using combined RMSE objective (interpolation + extrapolation)

- Model Selection: Choose configuration minimizing combined RMSE across 10× 5-fold CV and sorted extrapolation CV

- Comprehensive Reporting: Generate PDF with performance metrics, feature importance, and outlier detection [10]

Protocol for Imbalanced Data Handling

K-Ratio Undersampling Methodology:

- Initial Assessment: Calculate imbalance ratio (IR) as minority class size / majority class size

- Ratio Optimization: Test multiple IRs (1:50, 1:25, 1:10) rather than default balance (1:1)

- Model Training: Train ML models (RF, XGBoost, GCN, etc.) on resampled datasets

- Performance Evaluation: Focus on PPV for top-ranked predictions (e.g., first 128 compounds)

- External Validation: Assess generalization on completely independent test sets [24]

Protocol for Method Comparison

Statistically Rigorous Benchmarking:

- Cross-Validation Design: Implement 5x5-fold CV with identical splits across methods

- Performance Aggregation: Collect metrics across all folds and repetitions

- Statistical Testing: Apply Tukey's HSD test with confidence interval plots

- Practical Significance: Consider experimental error when interpreting differences

- Visualization: Create paired performance plots with statistical annotations [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Addressing Data Challenges in Chemical ML

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ROBERT Software | Automated workflow for small data | Mitigates overfitting in datasets with <50 points through specialized Bayesian optimization [10] |

| TabPFN | Tabular foundation model | In-context learning for small-to-medium tabular datasets without dataset-specific training [21] |

| SMOTE & Variants | Synthetic data generation | Addresses class imbalance by creating synthetic minority class samples [22] |

| Farthest Point Sampling | Diversity-based sampling | Enhances model performance by maximizing chemical diversity in training sets [27] |

| Reasoning BO | LLM-enhanced optimization | Incorporates domain knowledge and reasoning into Bayesian optimization loops [26] |

| ChemProp | Graph neural network | Specialized architecture for molecular property prediction with built-in regularization [7] |

Effective hyperparameter tuning in chemical informatics requires thoughtful consideration of underlying data challenges. Small datasets benefit from specialized workflows that explicitly optimize for generalization through combined validation metrics. Imbalanced data necessitates a paradigm shift from balanced accuracy to PPV-driven evaluation, particularly for virtual screening applications. Experimental error must be accounted for when comparing models to ensure practically significant improvements. Emerging approaches including foundation models for tabular data, LLM-enhanced Bayesian optimization, and diversity-based sampling strategies offer promising avenues for addressing these persistent challenges. By integrating these methodologies into their hyperparameter tuning workflows, chemical researchers can develop more robust and predictive models that accelerate scientific discovery and drug development.

Mastering the Methods: A Guide to Hyperparameter Optimization Techniques

In the data-driven field of chemical informatics, where predicting molecular properties, optimizing chemical reactions, and virtual screening are paramount, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models have become indispensable. The performance of these models, particularly complex architectures like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) used to model molecular structures, is highly sensitive to their configuration settings, known as hyperparameters [5]. Hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is therefore not merely a final polishing step but a fundamental process for building robust, reliable, and high-performing models. It is the key to unlocking the full potential of AI in drug discovery and materials science [5] [7].

While advanced optimization methods like Bayesian Optimization and evolutionary algorithms like Paddy are gaining traction [28], Grid Search and Random Search remain the foundational "traditional workhorses" of HPO. Their simplicity, predictability, and ease of parallelization make them an ideal starting point for researchers embarking on hyperparameter tuning. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of implementing these core methods within chemical informatics research, equipping scientists with the knowledge to systematically improve their predictive models.

Hyperparameter Tuning Fundamentals

What are Hyperparameters?

In machine learning, we distinguish between two types of variables:

- Model Parameters: These are internal variables whose values are learned from the data during the training process. Examples include the weights and biases in a neural network.

- Hyperparameters: These are external configuration variables whose values are set prior to the training process. They control the very learning process itself, acting as a steering mechanism for the optimization algorithm [29].

An apt analogy is to consider your model a race car. The model parameters are the driver's reflexes, learned through practice. The hyperparameters are the engine tuning—RPM limits, gear ratios, and tire selection. Set these incorrectly, and you will never win the race, no matter how much you practice [29].

The Impact of Key Hyperparameters

The following hyperparameters are frequently tuned in chemical informatics models, including neural networks for molecular property prediction:

Learning Rate: Perhaps the most critical hyperparameter. It controls the size of the steps the optimization algorithm takes when updating model weights [29] [11].

Batch Size: Determines how many training samples are processed before the model's internal parameters are updated. It affects both the stability of the training and the computational efficiency [29] [11].

Number of Epochs: Defines how many times the learning algorithm will work through the entire training dataset. Too few epochs result in underfitting, while too many can lead to overfitting [11].

Architecture-Specific Hyperparameters: For GNNs and other specialized architectures, this includes parameters like the number of graph convolutional layers, the dimensionality of node embeddings, and dropout rates [5] [11].

The Traditional Workhorses: A Comparative Analysis

Grid Search

Grid Search (GS) is a quintessential brute-force optimization algorithm. It operates by exhaustively searching over a manually specified subset of the hyperparameter space [30].

- Methodology: The researcher defines a set of discrete values for each hyperparameter to be tuned. Grid Search then trains and evaluates a model for every single possible combination of these values. The combination that yields the best performance on a validation set is selected as optimal [29] [30].

- Luck Factor: "0% Luck, but RIP the compute budget" [29]. Its strength is its comprehensiveness, but this comes at a high computational cost.

Random Search

Random Search (RS) addresses the computational inefficiency of Grid Search by adopting a stochastic approach.

- Methodology: Instead of an exhaustive search, Random Search randomly samples a fixed number of hyperparameter combinations from the defined search space (which can be specified as probability distributions). It evaluates these sampled configurations to find the best one [30].

- Luck Factor: "I'm not lucky, but a 10% chance beats 0%" [29]. It sacrifices guaranteed coverage for efficiency, often finding good solutions much faster than Grid Search.

The table below synthesizes the core characteristics of both methods to guide method selection.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Grid Search and Random Search.

| Feature | Grid Search | Random Search |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Exhaustive, brute-force search over a discrete grid [29] [30] | Stochastic random sampling from defined distributions [30] |

| Search Strategy | Systematic and sequential | Non-systematic and random |

| Computational Cost | Very high (grows exponentially with parameters) [29] | Lower and more controllable [30] |

| Best For | Small, low-dimensional hyperparameter spaces (e.g., 2-4 parameters) | Medium to high-dimensional spaces [11] |

| Key Advantage | Guaranteed to find the best point on the defined grid | More efficient exploration of large spaces; faster to find a good solution [30] |

| Key Disadvantage | Computationally prohibitive for large search spaces [29] [30] | No guarantee of finding the optimal configuration; can miss important regions |

The intuition behind Random Search's efficiency, especially in higher dimensions, is that for most practical problems, only a few hyperparameters truly critically impact the model's performance. Grid Search wastes massive resources by exhaustively varying the less important parameters, while Random Search explores a wider range of values for all parameters, increasing the probability of finding a good setting for the critical ones [11].

Implementation Protocols

This section provides detailed, step-by-step methodologies for implementing Grid and Random Search, using a hypothetical cheminformatics case study.

Case Study: Tuning a GNN for Molecular Property Prediction

Research Objective: Optimize a Graph Neural Network to predict compound solubility (a key ADMET property) using a molecular graph dataset.

Defined Hyperparameter Search Space:

- Learning Rate: Log-uniform distribution from

1e-5to1e-1 - Number of GNN Layers:

[2, 3, 4, 5] - Hidden Layer Dimension:

[64, 128, 256] - Dropout Rate: Uniform distribution from

0.1to0.5 - Batch Size:

[32, 64, 128]

Evaluation Metric: Mean Squared Error (MSE) on a held-out validation set.

Protocol 1: Grid Search Implementation

Discretize the Search Space: Convert all continuous parameters to a finite set of values. For example:

- Learning Rate:

[0.0001, 0.001, 0.01] - Number of GNN Layers:

[2, 3, 4] - Hidden Dimension:

[128, 256] - Dropout Rate:

[0.1, 0.3] - Batch Size:

[32, 64]

- Learning Rate:

Generate the Grid: Create the Cartesian product of all these sets. In this example, this results in (3 \times 3 \times 2 \times 2 \times 2 = 72) unique hyperparameter combinations.

Train and Evaluate: For each of the 72 configurations:

- Initialize the model with the configuration.

- Train on the training set for a fixed number of epochs.

- Evaluate the trained model on the validation set and record the MSE.

Select Optimal Configuration: Identify the hyperparameter set that achieved the lowest validation MSE. This is the final, optimized configuration.

Table 2: Example Grid Search configuration results (abridged).

| Trial | Learning Rate | GNN Layers | Hidden Dim | Dropout | Validation MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.001 | 3 | 128 | 0.1 | 0.89 |

| 2 | 0.001 | 3 | 128 | 0.3 | 0.92 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 72 (Best) | 0.0001 | 4 | 256 | 0.1 | 0.47 |

Protocol 2: Random Search Implementation

Define Parameter Distributions: Specify the sampling distribution for each hyperparameter.

- Learning Rate: Log-uniform between

1e-5and1e-1 - Number of GNN Layers: Choice of

[2, 3, 4, 5] - Hidden Dimension: Choice of

[64, 128, 256] - Dropout Rate: Uniform between

0.1and0.5 - Batch Size: Choice of

[32, 64, 128]

- Learning Rate: Log-uniform between

Set Computational Budget: Determine the number of random configurations to sample and evaluate (e.g.,

n_iter=50). This is a fixed budget, independent of the number of parameters.Sample and Train: For

iinn_iter:- Randomly sample one value for each hyperparameter from its distribution.

- Train and evaluate the model as in the Grid Search protocol.

- Record the validation MSE.

Select Optimal Configuration: After all 50 trials, select the configuration with the lowest validation MSE.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points for both Grid Search and Random Search, highlighting their distinct approaches to exploring the hyperparameter space.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing these optimization techniques requires both software libraries and computational resources. The following table details the key components of a modern HPO toolkit for a chemical informatics researcher.

Table 3: Essential tools and resources for hyperparameter optimization.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Cheminformatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides ready-to-use GridSearchCV and RandomizedSearchCV implementations for ML models [31]. |

Ideal for tuning traditional ML models (e.g., Random Forest) on molecular fingerprints or descriptors. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Software Library | Deep learning frameworks for building and training complex models like GNNs [31]. | The foundation for creating and tuning GNNs and other DL architectures for molecular data. |

| SpotPython / SPOT | Software Library | A hyperparameter tuning toolbox that can be integrated with various ML frameworks [31]. | Offers advanced search algorithms and analysis tools for rigorous optimization studies. |

| Ray Tune | Software Library | A scalable Python library for distributed HPO, compatible with PyTorch/TensorFlow [31]. | Enables efficient tuning of large, compute-intensive GNNs by leveraging cluster computing. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware Resource | Provides massive parallel processing capabilities. | Crucial for running large-scale Grid Searches or multiple concurrent Random Search trials. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Library (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | Software Library | Specialized libraries for implementing GNNs. | Provides the model architectures whose hyperparameters (layers, hidden dim) are being tuned [5]. |

Application in Chemical Informatics: A Closer Look

The choice of HPO method can significantly impact research outcomes in chemical informatics. For instance, a study optimizing an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to predict HVAC heating coil performance utilized a massive Grid Search, testing 288 unique hyperparameter configurations multiple times, resulting in a total of 864 trained models. This exhaustive search identified a highly specific, non-intuitive optimal architecture with 17 hidden layers and a left-triangular shape, which significantly outperformed other configurations [32]. This demonstrates Grid Search's power in smaller, well-defined search spaces where computational cost is acceptable.

In contrast, for tasks involving high-dimensional data or complex models like those common in drug discovery, Random Search often proves more efficient. A comparative analysis of HPO methods for predicting heart failure outcomes highlighted that Random Search required less processing time than Grid Search while maintaining robust model performance [30]. This efficiency is critical in cheminformatics, where model training can be time-consuming due to large datasets or complex architectures like GNNs and Transformers [7].

A critical consideration in this domain, especially when working with limited experimental data, is the risk of overfitting during HPO. It has been shown that extensive hyperparameter optimization (e.g., large grid searches) on small datasets can lead to models that perform well on the validation set but fail to generalize. In such cases, using a preselected set of hyperparameters can sometimes yield similar or even better real-world accuracy than an aggressively tuned model, underscoring the need for careful experimental design and robust validation practices like nested cross-validation [7].

Grid Search and Random Search are foundational techniques that form the bedrock of hyperparameter optimization in chemical informatics. Grid Search, with its brute-force comprehensiveness, is best deployed on small, low-dimensional search spaces where its guarantee of finding the grid optimum is worth the computational expense. Random Search, with its superior efficiency, is the preferred choice for exploring larger, more complex hyperparameter spaces commonly encountered with modern deep learning architectures like GNNs.

Mastering these traditional workhorses provides researchers with a reliable and interpretable methodology for improving model performance. This, in turn, accelerates the development of more accurate predictive models for molecular property prediction, virtual screening, and reaction optimization, thereby driving innovation in drug discovery and materials science. As a practical strategy, one can begin with a broad Random Search to identify a promising region of the hyperparameter space, followed by a more focused Grid Search in that region for fine-tuning, combining the strengths of both approaches [29].

Advanced Bayesian Optimization for Efficient Search in High-Dimensional Spaces

In chemical informatics research, optimizing complex, expensive-to-evaluate functions is a fundamental challenge, encountered in tasks ranging from molecular property prediction and reaction condition optimization to materials discovery. These problems are characterized by high-dimensional parameter spaces, costly experiments or simulations, and frequently, a lack of gradient information. Bayesian Optimization (BO) has emerged as a powerful, sample-efficient framework for navigating such black-box functions, making it particularly valuable for hyperparameter tuning of sophisticated models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in cheminformatics [5] [33] [34].

However, applying BO in high-dimensional spaces—a common scenario in chemical informatics—presents significant challenges. The performance of traditional BO can degrade as dimensionality increases, a phenomenon often exacerbated by poor initialization of its surrogate model [35]. Furthermore, the choice of molecular or material representation critically influences the optimization efficiency, and an inappropriate, high-dimensional representation can hinder the search process [36]. This technical guide explores advanced BO methodologies designed to overcome these hurdles, providing cheminformatics researchers and drug development professionals with practical protocols and tools for efficient search in high-dimensional spaces.

Core Challenges in High-Dimensional Bayesian Optimization

Successfully deploying BO in high-dimensional settings requires an understanding of its inherent limitations. The primary challenges include:

- The Curse of Dimensionality: The volume of the search space grows exponentially with dimensionality, making it difficult for the surrogate model to effectively learn the underlying function. High-dimensional representations of molecules and materials, while informative, can lead to poor BO performance if not managed correctly [36].

- Vanishing Gradients and Model Initialization: Simple BO methods can fail in high dimensions due to vanishing gradients caused by specific Gaussian process (GP) initialization schemes. This can stall the optimization process early on [35].

- Inadequate Representation: The efficiency of BO is heavily influenced by the completeness and compactness of the feature representation for molecules and materials. Using a fixed, suboptimal representation can introduce bias and severely limit performance, especially when prior knowledge for a novel optimization task is unavailable [36].

- Local Optima Trapping: Traditional BO methods are prone to becoming trapped in local optima and often lack interpretable, scientific insights that could guide a more global search [26].

Advanced Methodologies and Algorithms

To address these challenges, several advanced BO frameworks have been developed. The table below summarizes key methodologies relevant to cheminformatics applications.

Table 1: Advanced Bayesian Optimization Algorithms for High-Dimensional Spaces

| Algorithm/Framework | Core Methodology | Key Advantage | Typical Use Case in Cheminformatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Adaptive BO (FABO) [36] | Integrates feature selection (e.g., mRMR, Spearman ranking) directly into the BO cycle. | Dynamically adapts material representations, reducing dimensionality without prior knowledge. | MOF discovery; molecular optimization when optimal features are unknown. |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) / MSR [35] | Uses MLE of GP length scales to promote effective local search behavior. | Simple yet state-of-the-art performance; mitigates vanishing gradient issues. | High-dimensional real-world tasks where standard BO fails. |

| Reasoning BO [26] | Leverages LLMs for hypothesis generation, multi-agent systems, and knowledge graphs. | Provides global heuristics to avoid local optima; offers interpretable insights. | Chemical reaction yield optimization; guiding experimental campaigns. |

| Heteroscedastic Noise Modeling [37] | Employs GP models that account for non-constant (input-dependent) measurement noise. | Robustly handles the unpredictable noise inherent in biological/chemical experiments. | Optimizing biological systems (e.g., shake flasks, bioreactors). |

Feature Adaptive Bayesian Optimization (FABO)

The FABO framework automates the process of identifying the most informative features during the optimization campaign itself, eliminating the need for large, pre-existing labeled datasets or expert intuition [36].

Experimental Protocol for FABO:

- Initialization: Begin with a complete, high-dimensional pool of features for the materials or molecules (e.g., combining chemical descriptors like RACs and geometric pore characteristics for Metal-Organic Frameworks).

- Data Labeling: Perform an experiment or simulation (e.g., measure CO₂ uptake of a MOF) to get a labeled data point.

- Feature Selection: At each BO cycle, apply a feature selection method (e.g., mRMR) only on the data acquired so far to select the top-k most relevant features.

- Model Update: Update the Gaussian Process surrogate model using the adapted, lower-dimensional representation.

- Next Experiment Selection: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) on the updated model to select the next candidate to evaluate.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 until a stopping criterion is met.

This workflow has been benchmarked on tasks like MOF discovery for CO₂ adsorption and electronic band gap optimization, where it successfully identified representations that aligned with human chemical intuition and accelerated the discovery of top-performing materials [36].

Reasoning BO with Large Language Models

The Reasoning BO framework integrates the reasoning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) to overcome the black-box nature of traditional BO [26].

Workflow of the Reasoning BO Framework:

Diagram 1: Reasoning BO architecture.

Experimental Protocol for Reaction Yield Optimization:

- Problem Definition: The user describes the optimization goal and search space in natural language via an "Experiment Compass" (e.g., "optimize the yield of a direct arylation reaction by varying catalyst, solvent, and temperature").

- Candidate Proposal & Evaluation: The BO core proposes candidate reaction conditions. The LLM reasons about these candidates, leveraging domain knowledge from its internal model and an integrated knowledge graph. It generates scientific hypotheses and assigns a confidence score to each candidate.

- Filtering & Safeguarding: Candidates are filtered based on their confidence scores and consistency with prior results to ensure scientific plausibility and avoid nonsensical or unsafe experiments.

- Experiment & Knowledge Update: The top candidate is run in the lab. The result is stored and assimilated into the dynamic knowledge management system, which updates the knowledge graph for use in subsequent cycles.

In a benchmark test optimizing a Direct Arylation reaction, Reasoning BO achieved a final yield of 94.39%, significantly outperforming traditional BO, which reached only 76.60% [26].

Practical Implementation and Workflow Design

Implementing an effective BO campaign requires careful workflow design. The following diagram and protocol outline a robust, generalizable process for cheminformatics.

End-to-End Bayesian Optimization Workflow:

Diagram 2: BO workflow with adaptive representation.

Detailed Implementation Protocol:

Problem Formulation

- Objective Function: Define the expensive black-box function to optimize (e.g., molecular property prediction accuracy of a GNN, chemical reaction yield, material adsorption capacity).

- Search Space: Define the high-dimensional parameter space. For hyperparameter tuning, this includes parameters like learning rate, number of layers, and dropout. For molecular design, it includes structural and chemical features.

Initial Experimental Design

- Start with a small set of initial evaluations (e.g., 5-10 points) selected via random sampling or space-filling designs like Latin Hypercube Sampling to build an initial surrogate model.

Iterative Optimization Loop

- Surrogate Modeling: Model the objective function with a Gaussian Process. Configure the GP kernel (e.g., Matérn, RBF) and consider heteroscedastic noise models if experimental noise is variable [37].

- Acquisition Function Selection: Choose an acquisition function based on goals:

- Expected Improvement (EI): Good for rapid convergence to the optimum.

- Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Explicitly tunable exploration/exploitation trade-off.

- Thompson Sampling (TS): Effective for multi-objective problems via algorithms like TSEMO [33].

- Subspace & Representation Management: Integrate a feature selection module (as in FABO) or a generative model for dimensionality reduction to adapt the representation used by the surrogate model throughout the campaign [36].

Convergence and Termination

- Stop after a fixed number of iterations, when the objective plateaus, or when the acquisition function value falls below a threshold, indicating diminishing returns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful application of advanced BO requires both computational tools and an understanding of key chemical concepts. The table below lists "research reagents" for in-silico experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for BO in Cheminformatics

| Item Name | Type | Function / Relevance | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revised Autocorrelation Calculations (RACs) [36] | Molecular Descriptor | Captures the chemical nature of molecules/MOFs from their graph representation using atomic properties. | Representing MOF chemistry for property prediction in BO. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [36] | Material Class | Porous, crystalline materials with highly tunable chemistry and geometry; a complex testbed for BO. | Discovery of MOFs with optimal gas adsorption or electronic properties. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) with Matern Kernel [35] [37] | Surrogate Model | A flexible probabilistic model that serves as the core surrogate in BO; the Matern kernel is a standard, robust choice. | Modeling the black-box function relating reaction conditions to yield. |

| BayBE [38] | Software Package | A Bayesian optimization library designed for chemical reaction and condition optimization. | Identifying an optimal set of conditions for a direct arylation reaction. |