Hypothesis Testing for Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for using statistical hypothesis testing to validate predictive models in biomedical research and drug development.

Hypothesis Testing for Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for using statistical hypothesis testing to validate predictive models in biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational statistical principles, practical methodologies for comparing machine learning algorithms, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like p-hacking and underpowered studies, and advanced techniques for robust model comparison and Bayesian validation. Designed for researchers and scientists, the guide synthesizes classical and modern approaches to ensure model reliability, reproducibility, and translational impact in clinical settings.

Core Principles of Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Foundations for Model Validation

Defining the Null and Alternative Hypothesis in a Validation Context

In model validation and scientific research, hypothesis testing provides a formal framework for investigating ideas using statistics [1]. It is a critical process for making inferences about a population based on sample data, allowing researchers to test specific predictions that arise from theories [1]. The core of this framework rests on two competing, mutually exclusive statements: the null hypothesis (H₀) and the alternative hypothesis (Hₐ or H₁) [2] [3]. In a validation context, these hypotheses offer competing answers to a research question, enabling scientists to weigh evidence for and against a particular effect using statistical tests [2].

The null hypothesis typically represents a position of "no effect," "no difference," or the status quo that the validation study aims to challenge [4] [3]. For drug development professionals, this often translates to assuming a new treatment has no significant effect compared to a control or standard therapy. The alternative hypothesis, conversely, states the research prediction of an effect or relationship that the researcher expects or hopes to validate [2] [4]. Properly defining these hypotheses before data collection and interpretation is crucial, as it provides direction for the research and a framework for reporting inferences [5].

Fundamental Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Null Hypothesis (H₀)

The null hypothesis (H₀) is the default position that there is no effect, no difference, or no relationship between variables in the population [2] [4]. It is a claim about the population parameter that the validation study aims to disprove or challenge [4]. In statistical terms, the null hypothesis always includes an equality symbol (usually =, but sometimes ≥ or ≤) [2].

In the context of model validation and drug development, the null hypothesis often represents the proposition that any observed differences in data are due to chance rather than a genuine effect of the treatment or model being validated [6]. For example, in clinical trial validation, the null hypothesis might state that a new drug has the same efficacy as a placebo or standard treatment.

Alternative Hypothesis (Hₐ or H₁)

The alternative hypothesis (Hₐ or H₁) is the complement to the null hypothesis and represents the research hypothesis—what the statistician is trying to prove with data [2] [3]. It claims that there is a genuine effect, difference, or relationship in the population [2]. In mathematical terms, alternative hypotheses always include an inequality symbol (usually ≠, but sometimes < or >) [2].

In validation research, the alternative hypothesis typically reflects the expected outcome of the study—that the new model, drug, or treatment demonstrates a statistically significant effect worthy of validation. The alternative hypothesis is sometimes called the research hypothesis or experimental hypothesis [6].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Null and Alternative Hypotheses

| Characteristic | Null Hypothesis (H₀) | Alternative Hypothesis (Hₐ) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A claim of no effect in the population [2] | A claim of an effect in the population [2] |

| Role in Research | Represents the status quo or default position [3] | Represents the research prediction [2] |

| Mathematical Symbols | Equality symbol (=, ≥, or ≤) [2] | Inequality symbol (≠, <, or >) [2] |

| Verbal Cues | "No effect," "no difference," "no relationship" [2] | "An effect," "a difference," "a relationship" [2] |

| Mutually Exclusive | Yes, only one can be true at a time [2] | Yes, only one can be true at a time [2] |

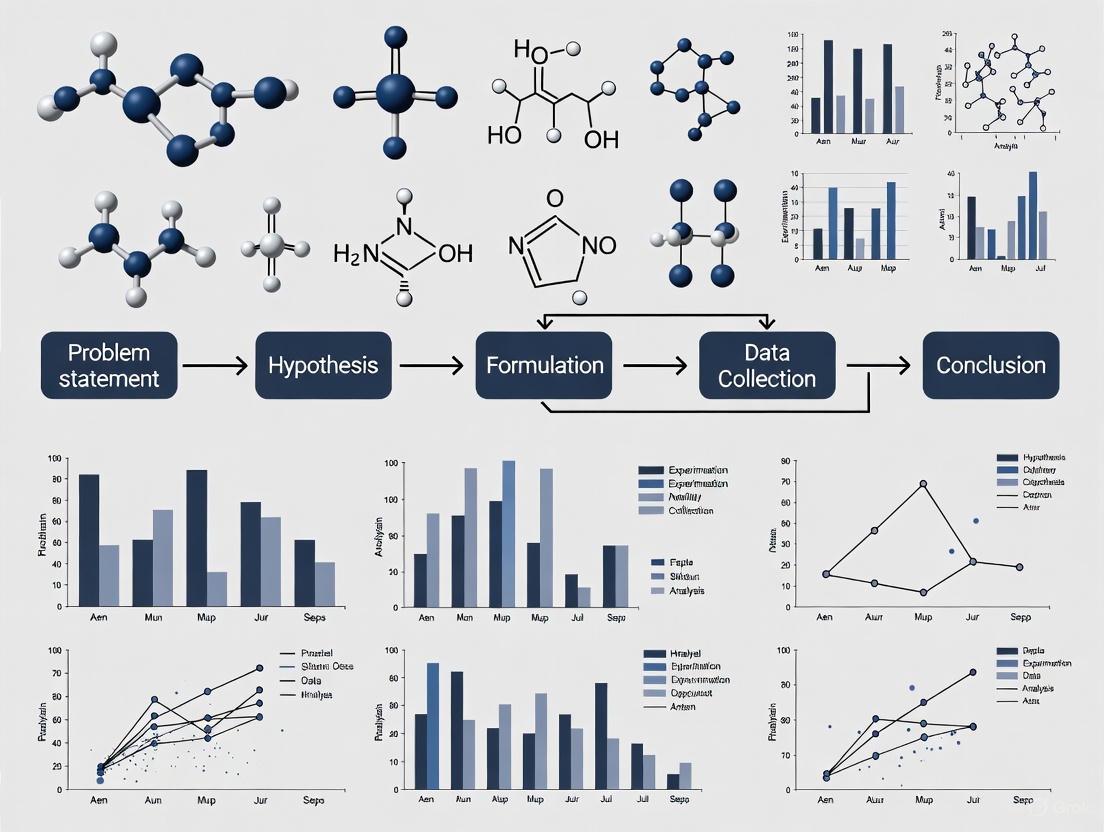

Figure 1: Hypothesis Testing Workflow in Validation Research

Formulating Hypotheses for Validation Studies

General Template Sentences

To formulate hypotheses for validation studies, researchers can use general template sentences that specify the dependent and independent variables [2]. The research question typically follows the format: "Does the independent variable affect the dependent variable?"

- Null hypothesis (H₀): "Independent variable does not affect dependent variable." [2]

- Alternative hypothesis (Hₐ): "Independent variable affects dependent variable." [2]

These general templates can be adapted to various validation contexts in drug development and model testing. The key is ensuring that both hypotheses are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, covering all possible outcomes of the study [4].

Test-Specific Formulations

Once the statistical test is chosen, hypotheses can be written in a more precise, mathematical way specific to the test [2]. The table below provides template sentences for common statistical tests used in validation research.

Table 2: Test-Specific Hypothesis Formulations for Validation Studies

| Statistical Test | Null Hypothesis (H₀) | Alternative Hypothesis (Hₐ) |

|---|---|---|

| Two-sample t-test | The mean dependent variable does not differ between group 1 (µ₁) and group 2 (µ₂) in the population; µ₁ = µ₂ [2] | The mean dependent variable differs between group 1 (µ₁) and group 2 (µ₂) in the population; µ₁ ≠ µ₂ [2] |

| One-way ANOVA with three groups | The mean dependent variable does not differ between group 1 (µ₁), group 2 (µ₂), and group 3 (µ₃) in the population; µ₁ = µ₂ = µ₃ [2] | The mean dependent variable of group 1 (µ₁), group 2 (µ₂), and group 3 (µ₃) are not all equal in the population [2] |

| Pearson correlation | There is no correlation between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; ρ = 0 [2] | There is a correlation between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; ρ ≠ 0 [2] |

| Simple linear regression | There is no relationship between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; β₁ = 0 [2] | There is a relationship between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; β₁ ≠ 0 [2] |

| Two-proportions z-test | The dependent variable expressed as a proportion does not differ between group 1 (p₁) and group 2 (p₂) in the population; p₁ = p₂ [2] | The dependent variable expressed as a proportion differs between group 1 (p₁) and group 2 (p₂) in the population; p₁ ≠ p₂ [2] |

Directional vs. Non-Directional Alternative Hypotheses

Alternative hypotheses can be categorized as directional or non-directional [5] [6]. This distinction determines whether the hypothesis test is one-tailed or two-tailed.

- Non-directional alternative hypothesis: A hypothesis that suggests there is a difference between groups but does not specify the direction of this difference [6]. This leads to a two-tailed test. For example: "The drug efficacy of Treatment A is different from Treatment B."

- Directional alternative hypothesis: A hypothesis that specifies the direction of the expected difference between groups [6]. This leads to a one-tailed test. For example: "The drug efficacy of Treatment A is greater than Treatment B."

The choice between directional and non-directional hypotheses should be theoretically justified and specified before data collection, as it affects the statistical power and interpretation of results.

Experimental Protocol for Hypothesis Testing in Validation

Step-by-Step Hypothesis Testing Procedure

The hypothesis testing procedure follows a systematic, step-by-step approach that should be rigorously applied in validation contexts [1].

Step 1: State the null and alternative hypotheses After developing the initial research hypothesis, restate it as a null hypothesis (H₀) and alternative hypothesis (Hₐ) that can be tested mathematically [1]. The hypotheses should be stated in both words and mathematical symbols, clearly defining the population parameters [7].

Step 2: Collect data For a statistical test to be valid, sampling and data collection must be designed to test the hypothesis [1]. The data must be representative to allow valid statistical inferences about the population of interest [1]. In validation studies, this often involves ensuring proper randomization, sample size, and control of confounding variables.

Step 3: Perform an appropriate statistical test Select and perform a statistical test based on the type of variables, the level of measurement, and the research question [1]. The test compares within-group variance (how spread out data is within a category) versus between-group variance (how different categories are from one another) [1]. The test generates a test statistic and p-value for interpretation.

Step 4: Decide whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis Based on the p-value from the statistical test and a predetermined significance level (α, usually 0.05), decide whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis [1] [4]. If the p-value is less than or equal to the significance level, reject H₀; if it is greater, fail to reject H₀ [4].

Step 5: Present the findings Present the results in the formal language of hypothesis testing, stating whether you reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis [1]. In scientific papers, also state whether the results support the alternative hypothesis [1]. Include the test statistic, p-value, and a conclusion in context [7].

Figure 2: Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for Hypothesis Testing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Validation Studies

| Item/Reagent | Function in Validation Research |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Performs complex statistical calculations, generates p-values, and creates visualizations for data interpretation [5] |

| Sample Size Calculator | Determines minimum sample size needed to achieve adequate statistical power for detecting effects |

| Randomization Tool | Ensures unbiased assignment to experimental groups, satisfying the "random" condition for valid hypothesis testing [7] [6] |

| Data Collection Protocol | Standardized procedure for collecting data to ensure consistency, reliability, and reproducibility |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Reference materials that validate experimental procedures by producing known, expected results |

| Standardized Measures/Assays | Validated instruments or biochemical assays that reliably measure dependent variables of interest |

| Blinding Materials | Procedures and materials to prevent bias in treatment administration and outcome assessment |

| Documentation System | Comprehensive system for recording methods, observations, and results to ensure traceability and reproducibility |

Interpretation and Decision Making in Validation

Understanding P-values and Significance

The p-value is a critical part of null-hypothesis significance testing that quantifies how strongly the sample data contradicts the null hypothesis [4]. It represents the probability of observing the obtained results, or more extreme results, if the null hypothesis were true [4].

A smaller p-value indicates stronger evidence against the null hypothesis [4]. In most validation research, a predetermined significance level (α) of 0.05 is used, meaning that if the p-value is less than or equal to 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected [4]. Some studies may choose a more conservative level of significance, such as 0.01, to minimize the risk of Type I errors [1].

Using precise language when reporting hypothesis test results is crucial, especially in validation research where conclusions inform critical decisions.

- When rejecting H₀: "Because the p-value (0.018) is less than α = 0.05, we reject H₀. We have convincing evidence that the alternative hypothesis is true." [7]

- When failing to reject H₀: "Since the p-value (0.063) is greater than α = 0.05, we fail to reject H₀. We do not have convincing evidence that the alternative hypothesis is true." [7]

It is essential to never say "accept the null hypothesis" because a lack of evidence against the null does not prove it is true [4] [3]. There is always a possibility that a larger sample size or different study design might detect an effect.

Error Types in Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing involves two types of errors that researchers must consider when interpreting results, particularly in high-stakes validation contexts [4] [3].

- Type I Error (False Positive): Rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true [4] [3]. The probability of a Type I error is denoted by α (alpha) and is typically set at 0.05 in scientific research [4].

- Type II Error (False Negative): Failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false [4] [3]. The probability of a Type II error is denoted by β (beta), and statistical power is defined as 1-β [3].

Table 4: Error Matrix in Hypothesis Testing for Validation

| Decision/Reality | H₀ is TRUE | H₀ is FALSE |

|---|---|---|

| Reject H₀ | Type I Error (False Positive) [4] [3] | Correct Decision (True Positive) |

| Fail to Reject H₀ | Correct Decision (True Negative) | Type II Error (False Negative) [4] [3] |

Applications in Model Validation and Drug Development

In model validation research, hypothesis testing provides a rigorous framework for evaluating model performance, comparing different models, and assessing predictive accuracy. For example, a null hypothesis might state that a new predictive model performs no better than an existing standard model, while the alternative hypothesis would claim superior performance.

In pharmaceutical development, hypothesis testing is fundamental to clinical trials, where the null hypothesis typically states that a new drug has no difference in efficacy compared to a placebo or standard treatment. Regulatory agencies like the FDA require rigorous hypothesis testing to demonstrate safety and efficacy before drug approval.

The principles outlined in this document apply across various validation contexts, ensuring that conclusions are based on statistical evidence rather than anecdotal observations or assumptions. Properly formulated and tested hypotheses provide the foundation for scientific advancement in drug development and model validation.

In the rigorous field of model validation research, particularly within drug development, statistical hypothesis testing provides the critical framework for making objective, data-driven decisions. This process allows researchers to quantify the evidence for or against a model's accuracy, moving beyond subjective assessment to rigorous statistical proof. At the heart of this framework lie three interconnected concepts: the significance level (α), the p-value, and statistical power. These concepts form the foundation for controlling error rates, interpreting experimental results, and ensuring that models are sufficiently sensitive to detect meaningful effects. Within model validation, this translates to a systematic process of building trust in a model through iterative testing and confirmation of its predictions against experimental data [8].

The core of hypothesis testing involves making two competing statements about a population parameter. The null hypothesis (H₀) typically represents a default position of "no effect," "no difference," or, in the context of model validation, "the model is not an accurate representation of reality." The alternative hypothesis (H₁ or Hₐ) is the logical opposite, asserting that a significant effect, difference, or relationship does exist [9] [10]. The goal of hypothesis testing is to determine whether there is sufficient evidence in the sample data to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative.

Deep Dive: P-values and Significance Levels (α)

The Significance Level (α) - A Pre-Defined Threshold

The significance level, denoted by alpha (α), is a pre-chosen probability threshold that determines the required strength of evidence needed to reject the null hypothesis. It represents the probability of making a Type I error, which is the incorrect rejection of a true null hypothesis [9] [11]. In practical terms, a Type I error in model validation would be concluding that a model is accurate when it is, in fact, flawed.

The choice of α is arbitrary but governed by convention and the consequences of error. Common thresholds include:

- α = 0.05: Accepts a 5% chance of a Type I error. This is the most common standard for general research and exploratory analysis [9].

- α = 0.01: Accepts a 1% chance of a Type I error. This is a stricter threshold often used in high-stakes research like clinical trials where the cost of a false positive is high [9].

- α = 0.001: Accepts a 0.1% chance of a Type I error. This signifies a "highly statistically significant" threshold and is used for findings where near-certainty is required [9].

The selection of α should be a deliberate decision based on the research context, goals, and the potential real-world impact of a false discovery [9].

The P-value - A Calculated Probability

The p-value is a calculated probability that measures the compatibility between the observed data and the null hypothesis. Formally, it is defined as the probability of obtaining a test result at least as extreme as the one actually observed, assuming that the null hypothesis is true [9] [11].

Unlike α, which is fixed beforehand, the p-value is computed from the sample data after the experiment or study is conducted. A smaller p-value indicates that the observed data is less likely to have occurred under the assumption of the null hypothesis, thus providing stronger evidence against H₀ [9].

Interpreting P-values and Making Decisions

The final step in a hypothesis test involves comparing the calculated p-value to the pre-defined significance level α. This comparison leads to a statistical decision:

- If the p-value ≤ α, there is sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The result is considered statistically significant, suggesting that the observed effect is unlikely to be due to chance alone [9] [12].

- If the p-value > α, there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The result is not statistically significant, and we "fail to reject H₀." It is critical to note that this is not the same as proving the null hypothesis true [9].

The table below summarizes this decision-making framework and the potential for error.

Table 1: Interpretation of P-values and Decision Framework

| P-value Range | Evidence Against H₀ | Action | Interpretation Cautions |

|---|---|---|---|

| p ≤ 0.01 | Very strong | Reject H₀ | Does not prove the alternative hypothesis is true; does not measure the size or importance of an effect. |

| 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05 | Strong | Reject H₀ | A statistically significant result may have little practical importance. |

| p > 0.05 | Weak or none | Fail to reject H₀ | Not evidence that the null hypothesis is true; may be due to low sample size or power. |

The Concept of Statistical Power

Statistical power is the probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis. In other words, it is the likelihood of detecting a real effect when it genuinely exists. Power is calculated as 1 - β, where β (beta) is the probability of a Type II error—failing to reject a false null hypothesis (a false negative) [11] [13].

A study with high power (e.g., 0.8 or 80%) has a high chance of identifying a meaningful effect, while an underpowered study is likely to miss real effects, leading to wasted resources and missed scientific opportunities [13]. Power is not a fixed property; it is influenced by several factors:

- Effect Size: Larger, more substantial effects are easier to detect and require less power.

- Sample Size (n): Larger samples provide more reliable estimates and increase power.

- Significance Level (α): A larger α (e.g., 0.05 vs. 0.01) makes it easier to reject H₀ and thus increases power, albeit at the cost of a higher Type I error rate.

- Data Variability: Less variability in the data increases the precision of measurements and improves power.

Table 2: Summary of Error Types in Hypothesis Testing

| Decision | H₀ is TRUE | H₀ is FALSE |

|---|---|---|

| Reject H₀ | Type I Error (False Positive) Probability = α | Correct Decision Probability = 1 - β (Power) |

| Fail to Reject H₀ | Correct Decision Probability = 1 - α | Type II Error (False Negative) Probability = β |

Application in Model Validation: Protocols and Workflows

In model validation, hypothesis testing is not a one-off event but an iterative construction process that mimics the implicit process occurring in the minds of scientists [8]. Trust in a model is built progressively through the accumulated confirmations of its predictions against repeated experimental tests.

An Iterative Validation Protocol

The following workflow formalizes this dynamic process of building trust in a scientific or computational model.

Power Analysis for Validation Study Design

A critical step in the validation protocol is designing the experiment with sufficient power. Conducting a power analysis prior to data collection ensures that the study is capable of detecting a meaningful effect, safeguarding against Type II errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Validation

The following table details essential "research reagents" and methodological components required for implementing hypothesis tests in a model validation context.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Methodological Components for Validation

| Item / Component | Function / Relevance in Validation |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SPSS) | Automates calculation of test statistics, p-values, and confidence intervals, reducing manual errors and ensuring reproducibility [9]. |

| Pre-Registered Analysis Plan | A detailed, publicly documented plan outlining hypotheses, primary metrics, and analysis methods before data collection. This is a critical safeguard against p-hacking and data dredging [13]. |

| A Priori Justified Alpha (α) | The pre-defined significance level, chosen based on the consequences of a Type I error in the specific research context (e.g., α=0.01 for high-stakes safety models) [9] [12]. |

| Sample Size Justification (Power Analysis) | A formal calculation, performed before the study, to determine the number of data points or experimental runs needed to achieve adequate statistical power [13]. |

| Standardized Metric Suite | Pre-defined primary, secondary, and guardrail metrics for consistent model evaluation and comparison across different validation experiments [14]. |

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Errors and Misinterpretations to Avoid

- P-hacking: The practice of continuously modifying data, models, or statistical tests until a statistically significant result (p < 0.05) is achieved. This massively inflates the false positive rate (Type I error) and leads to non-reproducible findings [13]. The safeguard is a pre-registered analysis plan.

- Underpowered Studies: Using a sample size that is too small to detect a meaningful effect. This results in a high probability of a Type II error, leading to the incorrect conclusion that a valid model is invalid simply because the test lacked the sensitivity to detect its accuracy [13].

- Misinterpreting 'Fail to Reject H₀': Concluding that a non-significant result (p > 0.05) proves the null hypothesis is true. It only indicates that the evidence was not strong enough to reject it; the model may still be valid but the test was inconclusive [9] [8].

- Neglecting Effect Size and Confidence Intervals: A statistically significant p-value does not indicate the magnitude or practical importance of an effect. Always report and interpret confidence intervals to understand the precision and potential real-world impact of the finding [9] [11].

Best Practices for Robust Validation

- Report Exact P-values: Instead of stating only p < 0.05, report the exact p-value (e.g., p = 0.032) to two or three decimal places, with values below 0.001 reported as p < .001. This provides more information about the strength of the evidence [9].

- Interpret P-values Alongside Other Evidence: P-values should be interpreted in the context of confidence intervals, effect sizes, study design quality, and prior replication evidence to form a reliable conclusion [9].

- Use Two-Tailed Tests by Default: Unless there is a powerful, a priori reason to expect an effect in only one direction, use two-tailed tests. This is a more conservative and generally more appropriate approach for model validation [11].

- Frame Validation as an Iterative Process: As captured in the workflow diagram, validation is not a binary "pass/fail" but a process of building trust through repeated, rigorous testing against a variety of data [8].

Definition and Core Concepts

In statistical hypothesis testing, two types of errors can occur when making a decision about the null hypothesis (H₀). A Type I error (false positive) occurs when the null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected, meaning we conclude there is an effect or difference when none exists. A Type II error (false negative) occurs when the null hypothesis is incorrectly retained, meaning we fail to detect a true effect or difference [15] [16] [17].

These errors are fundamental to understanding the reliability of statistical conclusions in research. The null hypothesis typically represents a default position of no effect, no difference, or no relationship, while the alternative hypothesis (H₁) represents the research prediction of an effect, difference, or relationship [16] [13].

Table 1: Characteristics of Type I and Type II Errors

| Characteristic | Type I Error (False Positive) | Type II Error (False Negative) |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Definition | Rejecting a true null hypothesis | Failing to reject a false null hypothesis |

| Probability Symbol | α (alpha) | β (beta) |

| Typical Acceptable Threshold | 0.05 (5%) | 0.20 (20%) |

| Relationship to Power | - | Power = 1 - β |

| Common Causes | Overly sensitive test, small p-value by chance | Insufficient sample size, high variability, small effect size |

| Primary Control Method | Setting significance level (α) | Increasing sample size, increasing effect size |

Table 2: Comparative Examples Across Research Domains

| Application Domain | Type I Error Consequence | Type II Error Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Diagnosis | Healthy patient diagnosed as ill, leading to unnecessary treatment [15] | Sick patient diagnosed as healthy, leading to lack of treatment [15] |

| Drug Development | Concluding ineffective drug is effective, wasting resources on false lead | Failing to identify a truly effective therapeutic compound |

| Fraud Detection | Legitimate transaction flagged as fraudulent, causing customer inconvenience [15] | Fraudulent transaction missed, leading to financial loss [15] |

Mathematical Formulation and Error Trade-offs

The probabilities of Type I and Type II errors are inversely related when sample size is fixed. Reducing the risk of one typically increases the risk of the other [17].

Key metrics for evaluating these errors include:

- Significance Level (α): The probability of making a Type I error, typically set at 0.05 (5%) [17]

- Power (1-β): The probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis, typically set at 0.80 (80%) or higher [17]

- Precision: TP/(TP+FP) - Measures how many positive predictions are truly positive [15]

- Recall (Sensitivity): TP/(TP+FN) - Measures how many actual positives are correctly identified [15]

Experimental Protocols for Error Control

Protocol for Controlling Type I Error Rate

Objective: Minimize false positive conclusions while maintaining adequate statistical power.

Procedure:

- Establish significance level prior to data collection (typically α = 0.05)

- Apply Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons: divide α by the number of hypotheses tested

- Implement pre-registration of analysis plans to prevent p-hacking [13]

- Conduct a priori power analysis to determine appropriate sample size

- Use validated statistical methods with assumptions verified for the data type

Validation: Simulation studies demonstrating that under true null hypothesis, false positive rate does not exceed nominal α level.

Protocol for Controlling Type II Error Rate

Objective: Minimize false negative conclusions while maintaining controlled Type I error rate.

Procedure:

- Conduct power analysis prior to data collection to determine sample size

- Minimize measurement error through standardized protocols and calibrated instruments

- Increase effect size where possible through improved experimental design

- Consider one-tailed tests when direction of effect can be confidently predicted

- Use more sensitive statistical tests appropriate for the data distribution

Validation: Post-hoc power analysis or sensitivity analysis to determine minimum detectable effect size.

Protocol for Balanced Error Control

Objective: Balance risks of both error types based on contextual consequences.

Procedure:

- Assess relative consequences of each error type for the specific research context

- Adjust significance level based on risk assessment (may use α = 0.10, 0.05, or 0.01)

- Implement sample size calculation that considers both α and β simultaneously

- Utilize Bayesian methods where appropriate to incorporate prior knowledge

- Apply cost-benefit analysis to determine optimal balance between error risks

Visual Representation of Error Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Error Control

| Research Component | Function in Error Control | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Power Analysis Software | Determines minimum sample size required to detect effect while controlling Type II error | G*Power, SAS POWER procedure, R pwr package |

| Multiple Comparison Correction | Controls family-wise error rate when testing multiple hypotheses, reducing Type I error inflation | Bonferroni correction, False Discovery Rate (FDR), Tukey's HSD |

| Pre-registration Platforms | Prevents p-hacking and data dredging by specifying analysis plan before data collection, controlling Type I error | Open Science Framework, ClinicalTrials.gov |

| Bayesian Analysis Frameworks | Provides alternative approach incorporating prior knowledge, offering different perspective on error trade-offs | Stan, JAGS, Bayesian structural equation modeling |

| Simulation Tools | Validates statistical power and error rates under various scenarios before conducting actual study | Monte Carlo simulation, bootstrap resampling methods |

In the scientific process, particularly in fields like drug development, hypothesis testing serves as a formal mechanism for validating models against empirical data [8]. This process involves making two competing statements about a population parameter: the null hypothesis (H0), which is the default assumption that no effect or difference exists, and the alternative hypothesis (Ha), which represents the effect or difference you aim to prove [10]. Model validation can be viewed as an iterative construction process that mimics the implicit trust-building occurring in the minds of scientists, progressively building confidence in a model's predictive capability through repeated experimental confirmation [8]. The core of this validation lies in determining whether observed differences between model predictions and experimental measurements are statistically significant or merely due to random chance, a determination made through carefully selected statistical tests [18].

Theoretical Foundations: Parametric and Non-Parametric Tests

Core Principles of Parametric Tests

Parametric statistics are methods that rely on specific assumptions about the underlying distribution of the population being studied, most commonly the normal distribution [19]. These methods estimate parameters (such as the mean (μ) and variance (σ²)) of this assumed distribution and use them for inference [20]. The power of parametric tests—their ability to detect a true effect when it exists—is maximized when their underlying assumptions are satisfied [21] [19].

Key Assumptions:

- Normality: The data originate from a population that follows a normal distribution [22] [19].

- Homogeneity of Variance: The variance within populations should be approximately equal across groups being compared [19].

- Interval/Ratio Data: The dependent variable should be measured on a continuous scale [20].

- Independence: Observations must be independent of one another [19].

Core Principles of Non-Parametric Tests

Non-parametric statistics, often termed "distribution-free" methods, do not rely on specific assumptions about the shape or parameters of the underlying population distribution [22] [19]. Instead of using the original data values, these methods often conduct analysis based on signs (+ or -) or the ranks of the data [23]. This makes them particularly valuable when data violate the stringent assumptions required for parametric tests, albeit often at the cost of some statistical power [23] [20].

Key Characteristics:

- Distribution-Free: No assumption of a specific population distribution (e.g., normality) is required [24] [22].

- Robust to Outliers: Results are not seriously affected by extreme values because they use ranks [23] [19].

- Handles Various Data Types: Applicable to ordinal, nominal, or non-normal continuous data [22] [20].

- Small Sample Usability: Can be used with very small sample sizes where parametric assumptions are impossible to verify [23].

Decision Framework: Choosing the Appropriate Test

A Structured Workflow for Test Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to selecting the appropriate statistical test, integrating considerations of data type, distribution, and study design. This workflow ensures that the chosen test aligns with the fundamental characteristics of your data, which is a prerequisite for valid model validation.

Comparative Analysis of Statistical Tests

Table 1: Guide to Selecting Common Parametric and Non-Parametric Tests

| Research Question | Parametric Test | Non-Parametric Equivalent | Typical Use Case in Model Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compare one group to a hypothetical value | One-sample t-test | Sign test / Wilcoxon signed-rank test [23] | Testing if model prediction errors are centered around zero. |

| Compare two independent groups | Independent samples t-test | Mann-Whitney U test [24] [23] | Comparing prediction accuracy between two different model architectures. |

| Compare two paired/matched groups | Paired t-test | Wilcoxon signed-rank test [24] [23] | Comparing model outputs before and after a calibration adjustment using the same dataset. |

| Compare three or more independent groups | One-way ANOVA | Kruskal-Wallis test [23] [22] | Evaluating performance across multiple versions of a simulation model. |

| Assess relationship between two variables | Pearson correlation | Spearman's rank correlation [24] [20] | Quantifying the monotonic relationship between a model's predicted and observed values. |

When to Choose Parametric vs. Non-Parametric Methods

Choose Parametric Methods If:

- Your data is approximately normally distributed [24] [20].

- The dependent variable is measured on an interval or ratio scale [20].

- Assumptions of homogeneity of variance and independence are met [20] [19].

- The goal is to estimate population parameters (e.g., mean difference) with high precision and power [21] [19].

Choose Non-Parametric Methods If:

- Your data is ordinal, nominal, or severely skewed and not normally distributed [24] [20].

- The sample size is small (e.g., n < 30) and the population distribution is unknown [24] [23].

- Your data contains significant outliers that could unduly influence parametric results [23] [19].

- Assumptions of homogeneity of variance for parametric tests are violated [20].

Experimental Protocols for Test Application

Protocol 1: Normality Testing and Data Assessment

Purpose: To objectively determine whether a dataset meets the normality assumption required for parametric tests, a critical first step in the test selection workflow.

Materials: Statistical software (e.g., R, Python with SciPy/StatsModels, PSPP, SAS).

Procedure:

- Visual Inspection: Generate graphical summaries of the data [22].

- Create a histogram with a superimposed normal curve. Assess the symmetry and bell-shape of the distribution.

- Create a Q-Q (Quantile-Quantile) plot. Data from a normal distribution will closely follow the reference line.

- Formal Normality Tests: Conduct statistical tests for normality.

- Perform the Shapiro-Wilk test (preferred for small to moderate samples) or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [23].

- Interpretation: A non-significant p-value (p > 0.05) suggests a failure to reject the null hypothesis of normality. A significant p-value (p < 0.05) indicates a deviation from normality.

- Assess Homogeneity of Variance: If comparing groups, test for equal variances.

- Use Levene's test or Bartlett's test.

- Interpretation: A non-significant p-value (p > 0.05) suggests homogeneity of variances is met.

Decision Logic: If both visual inspection and formal tests indicate no severe violation of normality, and group variances are equal, proceed with parametric tests. If violations are severe, proceed to non-parametric alternatives [22].

Protocol 2: Executing the Mann-Whitney U Test for Independent Groups

Purpose: To compare the medians of two independent groups when the assumption of normality for the independent t-test is violated. This is common in model validation when comparing error distributions from two different predictive models.

Materials: Dataset containing a continuous or ordinal dependent variable and a categorical independent variable with two groups; statistical software.

Procedure:

- Hypothesis Formulation:

- Null Hypothesis (H0): The distributions of the two groups are equal.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The distributions of the two groups are not equal.

- Data Preparation: Ensure data is correctly formatted with one column for the dependent variable and one for the group assignment.

- Rank the Data: Combine the data from both groups and assign ranks from 1 to N (where N is the total number of observations). Average the ranks for tied values [23].

- Calculate U Statistic:

- Determine Significance:

- For large samples (typically n > 20 in each group), the U statistic is approximately normally distributed. Software will compute a Z-score and a corresponding p-value.

- For small samples, consult exact critical value tables for U.

- Interpretation:

- If the p-value is less than the chosen significance level (α, typically 0.05), reject the null hypothesis and conclude a statistically significant difference in the distributions between the two groups.

Protocol 3: Model Validation via Equivalence Testing

Purpose: To flip the burden of proof in model validation by testing the null hypothesis that the model is unacceptable, rather than the traditional null hypothesis of no difference. This is a more rigorous framework for demonstrating model validity [18].

Materials: A set of paired observations (model predictions and corresponding experimental measurements); a pre-defined "region of indifference" (δ) representing the maximum acceptable error.

Procedure:

- Define Equivalence Margin: Establish the region of indifference (δ). This is the maximum difference between model predictions and observations that is considered practically negligible. This requires domain expertise (e.g., a 5% deviation is acceptable) [18].

- Calculate Differences: For each pair (i), compute the difference:

x_di = x_observed_i - x_predicted_i[18]. - Formulate Hypotheses:

- H0: |μd| ≥ δ (The mean difference is outside the acceptable margin; the model is invalid).

- H1: |μd| < δ (The mean difference is within the acceptable margin; the model is equivalent).

- Perform Two One-Sided Tests (TOST):

- Conduct two separate one-sided t-tests.

- Test 1: H01: μd ≤ -δ vs. H11: μd > -δ

- Test 2: H02: μd ≥ δ vs. H12: μd < δ

- Construct Confidence Interval: Alternatively, construct a (1 - 2α)% confidence interval for the mean difference. For a standard α of 0.05, this is a 90% confidence interval [18].

- Decision Rule: If the entire (1 - 2α)% confidence interval lies entirely within the equivalence region [-δ, +δ], then reject the null hypothesis H0 and conclude the model is equivalent (valid) at the α significance level [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Statistical Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Tools / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Provides the computational engine to perform hypothesis tests, calculate p-values, and generate confidence intervals. | R, Python (with pandas, SciPy, statsmodels), SAS, PSPP, SPSS [23]. |

| Data Visualization Package | Enables graphical assessment of data distribution, outliers, and relationships, which is the critical first step in test selection [22]. | ggplot2 (R), Matplotlib/Seaborn (Python). |

| Normality Test Function | Objectively assesses the normality assumption, guiding the choice between parametric and non-parametric paths. | Shapiro-Wilk test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [23]. |

| Power Analysis Software | Determines the sample size required to detect an effect of a given size with a certain degree of confidence, preventing Type II errors. | G*Power, pwr package (R). |

| Pre-Defined Equivalence Margin (δ) | A domain-specific criterion, not a software tool, that defines the maximum acceptable error for declaring a model valid in equivalence testing [18]. | Must be defined a priori based on scientific or clinical relevance (e.g., ±10% of the mean reference value). |

Advanced Considerations in Model Validation

The Iterative Nature of Validation

It is crucial to recognize that model validation is not a single event but an iterative process of building trust [8]. Each successful statistical comparison between model predictions and new experimental data increases confidence in the model's utility and clarifies its limitations. This process mirrors the scientific method itself, where hypotheses are continuously refined based on empirical evidence [8].

Power and Error Management

The choice between parametric and non-parametric tests directly impacts a study's statistical power—the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis. When their strict assumptions are met, parametric tests are generally more powerful than their non-parametric equivalents [21] [19]. Using a parametric test on severely non-normal data, however, can lead to an increased risk of Type II errors (failing to detect a true effect) [22]. Conversely, applying a non-parametric test to normal data results in a loss of efficiency, meaning a larger sample size would be needed to achieve the same power as the corresponding parametric test [23] [20]. The workflow and protocols provided herein are designed to minimize these errors and maximize the reliability of your model validation conclusions.

In the scientific method, particularly within model validation research, hypothesis testing provides a formal framework for making decisions based on data [13]. A critical initial step in this process is the formulation of the alternative hypothesis, which can be categorized as either directional (one-tailed) or non-directional (two-tailed) [25] [26]. This choice, determined a priori, fundamentally influences the statistical power, the interpretation of results, and the confidence in the model's predictive capabilities [27]. For researchers and scientists validating complex models in fields like drug development, where extrapolation is common and risks are high, selecting the appropriate test is not merely a statistical formality but a fundamental aspect of responsible experimental design [8]. This article outlines the theoretical underpinnings and provides practical protocols for implementing these tests within a model validation framework.

Theoretical Foundations

Defining Directional and Non-Directional Hypotheses

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about the relationship between variables [26]. In statistical testing, the null hypothesis (H₀) posits that no relationship or effect exists, while the alternative hypothesis (H₁ or Ha) states that there is a statistically significant effect [28] [13].

Directional Hypothesis (One-Tailed Test): This predicts the specific direction of the expected effect [26] [28]. It is used when prior knowledge, theory, or physical limitations suggest that any effect can only occur in one direction [29] [30]. Key words include "higher," "lower," "increase," "decrease," "positive," or "negative" [28].

Non-Directional Hypothesis (Two-Tailed Test): This predicts that an effect or difference exists, but does not specify its direction [31] [26]. It is used when there is no strong prior justification to predict a direction, or when effects in both directions are scientifically interesting [27].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and formulating a hypothesis type.

The Connection to One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Statistical Tests

The choice of hypothesis directly corresponds to the type of statistical test performed, which determines how the significance level (α), typically 0.05, is allocated [25] [32].

- One-Tailed Test: The entire alpha level (e.g., 0.05) is placed in a single tail of the distribution to test for an effect in one specific direction [25]. This provides greater statistical power to detect an effect in that direction because the barrier for achieving significance is lower [25] [27].

- Two-Tailed Test: The alpha level is split equally between the two tails of the distribution (e.g., 0.025 in each tail) [25]. This tests for the possibility of an effect in both directions, making it more conservative and requiring a larger sample size to achieve the same power as a one-tailed test for the same effect size [27].

Table 1: Core Differences Between One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Tests

| Feature | One-Tailed Test | Two-Tailed Test |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis Type | Directional [26] | Non-Directional [26] |

| Predicts Direction? | Yes [28] | No [28] |

| Alpha (α) Allocation | Entire α (e.g., 0.05) in one tail [25] | α split between tails (e.g., 0.025 each) [25] |

| Statistical Power | Higher for the predicted direction [25] [27] | Lower for a specific direction [27] |

| Risk of Missing Effect | High in the untested direction [25] | Low in either direction [27] |

| Conservative Nature | Less conservative [30] | More conservative [30] |

Decision Framework and Application Protocols

Guidelines for Choosing the Appropriate Test

Choosing between a one-tailed and two-tailed test is a critical decision that should be guided by principle, not convenience [29] [30]. The following protocol outlines the decision criteria.

When a One-Tailed Test is Appropriate: A one-tailed test is appropriate only when all of the following conditions are met [25] [29] [30]:

- Strong Directional Prediction: You have a strong theoretical, empirical, or logical basis (e.g., physical limitation) to predict the direction of the effect before looking at the data.

- Irrelevance of Opposite Effect: You can state with certainty that you would attribute an effect in the opposite direction to chance, and it would not be of scientific or practical interest. For example, testing if a new antibiotic impairs kidney function; an improvement in function is considered impossible given the drug's known mechanism [29] [30].

- A Priori Decision: The decision to use a one-tailed test is documented in the experimental protocol prior to data collection.

When a Two-Tailed Test is Appropriate (Default Choice): A two-tailed test should be used in these common situations [27] [30]:

- Exploratory Research: When there is limited or ambiguous prior evidence regarding the direction of the effect.

- Importance of Both Directions: When an effect in either direction would be meaningful and require follow-up. For instance, in A/B testing a new website feature, both a significant increase or decrease in conversion rates are critical to detect [27].

- Conservative Standard: As a default and more conservative option, especially when the consequences of a false positive (Type I error) are high [30].

When a One-Tailed Test is NOT Appropriate:

- To make a nearly significant two-tailed test become significant [25].

- When the decision is made after viewing the data to see which direction the effect went [29] [30].

- When a result in the opposite direction would still be intriguing and warrant investigation [29].

Quantitative Interpretation and p-Value Conversion

The p-value is the probability of obtaining results as extreme as the observed results, assuming the null hypothesis is true [13]. The choice of test directly impacts how this p-value is calculated and interpreted.

Table 2: p-Value Calculation and Interpretation

| Test Type | p-Value Answers the Question: | Interpretation of a Significant Result (p < α) |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Tailed | What is the chance of observing a difference this large or larger, in either direction, if H₀ is true? [29] [30] | The tested parameter is not equal to the null value. An effect exists, but its direction is not specified by the test. |

| One-Tailed | What is the chance of observing a difference this large or larger, specifically in the predicted direction, if H₀ is true? [29] [30] | The tested parameter is significantly greater than (or less than) the null value. |

For common symmetric test distributions (like the t-distribution), a simple mathematical relationship often exists between one-tailed and two-tailed p-values, provided the effect is in the predicted direction [25] [29].

- From Two-Tailed to One-Tailed: One-tailed p-value = (Two-tailed p-value) / 2 [25] [29] [30].

- From One-Tailed to Two-Tailed: Two-tailed p-value = (One-tailed p-value) * 2 [29] [30].

Example Conversion: If a two-tailed t-test yields a p-value of 0.08, the corresponding one-tailed p-value (if the effect was in the predicted direction) would be 0.04. At α=0.05, this would change the conclusion from "not significant" to "significant" [25].

Critical Note: If the observed effect is in the opposite direction to the one-tailed prediction, the one-tailed p-value is actually 1 - (two-tailed p-value / 2) [29] [30]. In this case, the result is not statistically significant for the one-tailed test, and the hypothesized effect is not supported.

Application in Model Validation Research

Framing Validation as an Iterative Hypothesis Test

In model validation, the process is not merely a single test but an iterative construction of trust, where the model is repeatedly challenged with new data [8]. The core question shifts from "Is the model true?" to "To what degree does the model accurately represent reality for its intended use?" [8]. This can be framed as a series of significance tests.

The null hypothesis (H₀) for a validation step is: "The model's predictions are not significantly different from experimental observations." The alternative hypothesis (H₁) can be either:

- Non-Directional (Two-Tailed): "The model's predictions are significantly different from the observations." This is the standard, conservative approach for general model assessment.

- Directional (One-Tailed): "The model's predictions are significantly worse (e.g., have a larger error) than the observations." This could be used in specific tuning phases where the goal is specifically to ensure the model does not exceed a certain error threshold in a particular direction.

Protocol for Validating a Predictive Model in Drug Development

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for integrating hypothesis testing into a model validation workflow, such as validating a pharmacokinetic (PK) model.

1. Pre-Validation Setup and Hypothesis Definition

- Define Validation Metrics: Determine the quantitative metrics for comparison (e.g., Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between model predictions and observed plasma concentration data, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)) [8].

- Set Acceptance Criteria: Define the clinical or scientific relevance threshold. For example, a pre-specified error margin (δ) of 15% might be the maximum acceptable deviation.

- Formalize Hypotheses:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The model's prediction error (e.g., RMSE) is less than or equal to the acceptance threshold (δ). (RMSE ≤ δ)

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The model's prediction error is greater than the acceptance threshold (RMSE > δ). This is a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis, as you are specifically testing for the model being unacceptably bad.

- Choose Test and Document: Select the appropriate statistical test (e.g., a one-sample t-test comparing errors to δ) and document this entire protocol before accessing the validation dataset [29].

2. Experimental and Computational Execution

- Run Model Simulations: Using the fixed, trained model, generate predictions for the conditions of the hold-out validation dataset.

- Collect Observational Data: Use the pre-defined validation dataset (e.g., clinical PK data from a new trial) that was not used in model training.

3. Data Analysis and Inference

- Calculate Test Statistic: Compute the validation metric (e.g., RMSE) from the comparison of predictions and observations.

- Perform Statistical Test: Conduct the pre-specified test. For example, test if the observed RMSE is significantly greater than the δ threshold at a significance level of α=0.05.

- Interpret Results:

- If p-value < 0.05: Reject H₀. There is significant evidence that the model error exceeds the acceptable threshold. The model fails this validation step and requires refinement.

- If p-value ≥ 0.05: Fail to reject H₀. There is not enough evidence to conclude that the model is unacceptable. Trust in the model increases, and it proceeds to the next validation step [8].

4. Iterative Validation Loop

- The model undergoes multiple such validation cycles against different datasets and under different conditions, each time potentially using different metrics and hypothesis tests tailored to the intended use [8]. This iterative process progressively builds confidence in the model's predictive capabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Validation Experiments

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Model Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation Context |

|---|---|

| Validation Dataset | A hold-out dataset, not used in model training, which serves as the empirical benchmark for testing model predictions [8]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python, Prism) | The computational environment for performing statistical tests (t-tests, etc.), calculating p-values, and generating visualizations [29] [30]. |

| Pre-Registered Protocol | A document detailing the planned analysis, including primary metrics, acceptance criteria, and statistical tests (one vs. two-tailed) before the validation exercise begins. This prevents p-hacking and confirms the a priori nature of the hypotheses [13]. |

| Reference Standard / Control | A known entity or positive control used to calibrate measurements and ensure the observational data used for validation is reliable (e.g., a standard drug compound with known PK properties). |

The judicious selection between one-tailed and two-tailed tests is a cornerstone of rigorous scientific inquiry, especially in high-stakes model validation research. A one-tailed test offers more power but should be reserved for situations with an unequivocal a priori directional prediction, where an opposite effect is negligible. For the vast majority of cases, including the general assessment of model fidelity, the two-tailed test remains the default, conservative, and recommended standard. By embedding these principles within an iterative validation framework—where models are continuously challenged with new data and pre-specified hypotheses—researchers and drug development professionals can construct robust, defensible, and trustworthy models, thereby ensuring that predictions reliably inform critical decisions.

Hypothesis testing is a formal statistical procedure for investigating ideas about the world, forming the backbone of evidence-based model validation research. In the context of drug development and scientific inquiry, it provides a structured framework to determine whether the evidence provided by data supports a specific model or validation claim. This process moves from a broad research question to a precise, testable hypothesis, and culminates in a statistical decision on whether to reject the null hypothesis. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this pipeline is critical for demonstrating the efficacy, safety, and performance of new models, compounds, and therapeutic interventions. The procedure ensures that conclusions are not based on random chance or subjective judgment but on rigorous, quantifiable statistical evidence [1] [33].

The core of this methodology lies in its ability to quantify the uncertainty inherent in experimental data. Whether validating a predictive biomarker, establishing the dose-response relationship of a new drug candidate, or testing a disease progression model, the principles of hypothesis testing remain consistent. This document outlines the complete workflow—from formulating a scientific question to selecting and executing the appropriate statistical test—with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical research [33].

The Five-Step Hypothesis Testing Pipeline

The process of hypothesis testing can be broken down into five essential steps. These steps create a logical progression from defining the research problem to interpreting and presenting the final results [1].

Step 1: State the Null and Alternative Hypotheses

The first step involves translating the general research question into precise statistical hypotheses.

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): This is the default assumption, typically representing "no effect," "no difference," or "no relationship." In model validation, it often states that the model does not perform better than an existing standard or a random chance baseline. Example: "The new predictive model for patient stratification does not improve accuracy over the current standard of care." [1] [34]

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Ha): This is the research hypothesis that you want to prove. It is a direct contradiction of the null hypothesis. Example: "The new predictive model for patient stratification significantly improves accuracy over the current standard of care." [1] [34]

The hypotheses must be constructed before any data collection or analysis occurs to prevent bias.

Step 2: Collect Data

Data must be collected in a way that is designed to specifically test the stated hypothesis. This involves:

- Study Design: Choosing an appropriate design (e.g., randomized controlled trial, case-control study) that minimizes bias.

- Sampling: Ensuring the data are representative of the population to which you wish to make statistical inferences.

- Power Analysis: Determining the sample size required to detect a meaningful effect, if one exists, with a high probability [1].

Step 3: Perform an Appropriate Statistical Test

The choice of statistical test depends on the type of data collected and the nature of the research question. Common tests include:

- t-test: Compares the means of two groups.

- ANOVA (Analysis of Variance): Compares the means of three or more groups.

- Chi-square test: Assesses the relationship between categorical variables.

- Regression analysis: Models the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables [35] [34].

The test calculates a test statistic (e.g., t-statistic, F-statistic) which is used to determine a p-value [35].

Step 4: Decide to Reject or Fail to Reject the Null Hypothesis

This decision is made by comparing the p-value from the statistical test to a pre-determined significance level (α).

- The most common significance level is 0.05 (5%) [1].

- If p-value ≤ α: You reject the null hypothesis, concluding that the results are statistically significant. This supports the alternative hypothesis.

- If p-value > α: You fail to reject the null hypothesis. The evidence is not strong enough to support the alternative hypothesis [1] [33].

It is critical to note that "failing to reject" the null is not the same as proving it true; it simply means that the current data do not provide sufficient evidence against it [1].

Step 5: Present the Findings

The results should be presented clearly in the results and discussion sections of a research paper or report. This includes:

- A brief summary of the data and the statistical test results.

- The estimated effect size (e.g., difference between group means).

- The p-value and/or confidence interval.

- A discussion on whether the initial hypothesis was supported and the clinical or practical significance of the findings [1] [33].

The following workflow diagram encapsulates this five-step process and its application to model validation research:

Core Components of a Testable Hypothesis

A well-structured validation hypothesis is built upon several key components that ensure it is both testable and meaningful. Understanding these elements is crucial for designing a robust validation study [34].

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The hypothesis of "no effect" or "no difference" that you aim to test against. It serves as the default or skeptical position. Example: "The new drug has the same effect on disease progression as the placebo." [1] [34]

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The hypothesis that contradicts H₀. It represents the effect or relationship the researcher believes exists or hopes to prove. Example: "The new drug has a different effect on disease progression compared to the placebo." (This can be one-sided or two-sided). [1] [34]

- Significance Level (α): The threshold of probability for rejecting the null hypothesis. It is the maximum risk of a Type I error you are willing to accept. A common choice is α = 0.05, meaning a 5% risk of concluding a difference exists when there is none [1] [34].

- Test Statistic: A standardized value (e.g., t, F, χ²) calculated from sample data during a hypothesis test. It measures the degree of agreement between the sample data and the null hypothesis [35].

- P-value: The probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the observed results, assuming the null hypothesis is true. A small p-value (typically ≤ α) provides evidence against the null hypothesis [33] [34].

- Confidence Interval (CI): An estimated range of values that is likely to include an unknown population parameter. A 95% CI means that if the same study were repeated many times, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true population parameter. CIs provide information about the precision and magnitude of an effect [33].

Table 1: Core Components of a Statistical Hypothesis

| Component | Definition | Role in Model Validation | Example/Common Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis (H₀) | The default assumption of no effect, difference, or relationship. | Serves as the benchmark; the model is assumed invalid until proven otherwise. | "The new diagnostic assay has a sensitivity ≤ 90%." |

| Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) | The research claim of an effect, difference, or relationship. | The validation claim you are trying to substantiate with evidence. | "The new diagnostic assay has a sensitivity > 90%." |

| Significance Level (α) | The probability threshold for rejecting H₀. | Sets the tolerance for a Type I error (false positive). | α = 0.05 or 5% |

| P-value | Probability of the observed data (or more extreme) if H₀ is true. | Quantifies the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis. | p = 0.03 (leads to rejection of H₀ at α=0.05) |

| Confidence Interval (CI) | A range of plausible values for the population parameter. | Provides an estimate of the effect size and the precision of the measurement. | 95% CI for a difference: 1.9 to 7.8 |

Selecting the Appropriate Statistical Test

Choosing the correct statistical test is fundamental to drawing valid conclusions. The choice depends primarily on the type of data (categorical or continuous) and the study design (e.g., number of groups, paired vs. unpaired observations) [35] [34].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting a common statistical test based on these factors:

Table 2: Guide to Selecting a Statistical Test for Model Validation

| Research Question Scenario | Outcome Variable Type | Number of Groups / Comparisons | Recommended Statistical Test | Example in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compare a single group to a known standard. | Continuous | One sample vs. a theoretical value | One-Sample t-test | Compare the mean IC₅₀ of a new compound to a value of 10μM. |

| Compare the means of two independent groups. | Continuous | Two independent groups | Independent (Unpaired) t-test | Compare tumor size reduction between treatment and control groups in different animals. |

| Compare the means of two related groups. | Continuous | Two paired/matched groups | Paired t-test | Compare blood pressure in the same patients before and after treatment. |

| Compare the means of three or more independent groups. | Continuous | Three or more independent groups | One-Way ANOVA | Compare the efficacy of three different drug doses and a placebo. |

| Assess the association between two categorical variables. | Categorical | Two or more categories | Chi-Square Test | Test if the proportion of responders is independent of genotype. |

| Model the relationship between multiple predictors and a continuous outcome. | Continuous & Categorical | Multiple independent variables | Linear Regression | Predict drug clearance based on patient weight, age, and renal function. |

| Model the probability of a binary outcome. | Categorical (Binary) | Multiple independent variables | Logistic Regression | Predict the probability of disease remission based on biomarker levels. |

When comparing quantitative data between groups, a clear summary is essential. This involves calculating descriptive statistics for each group and the key metric of interest: the difference between groups (e.g., difference between means). Note that measures like standard deviation or sample size do not apply to the difference itself [36].

Table 3: Template for Quantitative Data Summary in Group Comparisons

| Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) | Median | Interquartile Range (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (e.g., Experimental) | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value |

| Group B (e.g., Control) | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value |

| Difference (A - B) | Value | - | - | - | - |

Table 4: Example Data - Gorilla Chest-Beating Rate (beats per 10 h) [36]

| Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger Gorillas | 2.22 | 1.270 | 14 |

| Older Gorillas | 0.91 | 1.131 | 11 |

| Difference | 1.31 | - | - |

Experimental Protocol: A Sample Framework for In Vitro Drug Validation

This protocol outlines a hypothetical experiment to validate the efficacy of a new anti-cancer drug candidate in a cell culture model, following the hypothesis testing framework.

Hypothesis Formulation

- Research Question: Does the novel compound 'Drug X' reduce the viability of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7 line) more effectively than the current standard of care, 'Drug S'?

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The mean cell viability after 72 hours of treatment with Drug X is greater than or equal to the mean cell viability after treatment with Drug S. (μ_Drug X ≥ μ_Drug S)

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The mean cell viability after 72 hours of treatment with Drug X is less than the mean cell viability after treatment with Drug S. (μ_Drug X < μ_Drug S)

- Significance Level (α): Set at 0.05.

Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Cell Culture: Human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, maintained in standard conditions.

- Treatment Groups:

- Control Group: Vehicle control (e.g., DMSO).

- Standard Drug Group: Treated with Drug S at its IC₅₀ concentration.

- Experimental Group: Treated with Drug X at its IC₅₀ concentration.

- Experimental Units: 30 independent cell culture wells per group (n=30).

- Outcome Measure: Cell viability assessed after 72 hours of treatment using a colorimetric assay (e.g., MTT assay). The result is a continuous variable (optical density, OD).

Data Analysis and Statistical Testing

- Summary Statistics: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of cell viability (OD) for each group. Present in a table as in Table 3.

- Statistical Test Selection:

- Objective: Compare the means of three independent groups.

- Test Chosen: One-Way ANOVA.

- Post-hoc Test: If the ANOVA is significant, a post-hoc test (e.g., Tukey's HSD) will be used to make specific comparisons between Drug X and Drug S, and each drug against the control.

- Software: Analysis will be performed using a statistical software package (e.g., R, GraphPad Prism).

Decision and Interpretation

- The p-value from the ANOVA (and post-hoc tests) will be compared to α=0.05.

- If p ≤ 0.05: Reject the null hypothesis. Conclude that there is a statistically significant difference in cell viability between the treatment groups.

- If p > 0.05: Fail to reject the null hypothesis. Conclude that there is not enough evidence to say the drugs differ in their effect on cell viability under these experimental conditions.

- Reporting: Report the F-statistic, degrees of freedom, p-value, and effect sizes (e.g., mean differences with 95% confidence intervals).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biochemical Validation Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Validation |

|---|---|

| Cell Viability Assay Kits (e.g., MTT, WST-1) | Colorimetric assays to quantify metabolic activity, used as a proxy for the number of viable cells in culture. Critical for in vitro efficacy testing. |

| ELISA Kits | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays used to detect and quantify specific proteins (e.g., biomarkers, cytokines) in complex samples like serum or cell lysates. |

| Validated Antibodies (Primary & Secondary) | Essential for techniques like Western Blot and Immunohistochemistry to detect specific protein targets and confirm expression levels or post-translational modifications. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Pre-mixed solutions containing enzymes, dNTPs, and buffers required for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to measure gene expression. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), used for metabolite or drug compound quantification, ensuring minimal background interference. |

| Stable Cell Lines | Genetically engineered cells that consistently express (or silence) a target gene of interest, providing a standardized system for functional validation studies. |

| Reference Standards / Controls | Compounds or materials with known purity and activity, used to calibrate instruments and validate assay performance across multiple experimental runs. |

Practical Methods and Statistical Tests for Validating Predictive Models

In model validation research, particularly within pharmaceutical development, selecting the appropriate statistical test is fundamental to ensuring research validity and generating reliable, interpretable results. Hypothesis testing provides a structured framework for making quantitative decisions about model performance, helping researchers distinguish genuine effects from random noise [13]. This structured approach to statistical validation is especially critical in drug development, where decisions impact clinical trial strategies, portfolio management, and ultimately, patient outcomes [37] [38].

The core principle of hypothesis testing involves formulating two competing statements: the null hypothesis (H₀), which represents the default position of no effect or no difference, and the alternative hypothesis (H₁), which asserts the presence of a significant effect or relationship [34] [13]. By collecting sample data and calculating the probability of observing the results if the null hypothesis were true (the p-value), researchers can make evidence-based decisions to either reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis [13]. This process minimizes decision bias and provides a quantifiable measure of confidence in research findings, which is indispensable for validating predictive models, assessing algorithm performance, and optimizing development pipelines.

A Decision Framework for Statistical Test Selection

The following decision framework provides a systematic approach for researchers to select the most appropriate statistical test based on their research question, data types, and underlying assumptions. This framework synthesizes key decision points into a logical flowchart, supported by detailed parameter tables.

Statistical Test Selection Decision Tree

The diagram below maps the logical pathway for selecting an appropriate statistical test based on your research question and data characteristics. Follow the decision points from the top node to arrive at a recommended test.

Statistical Test Specifications and Applications

Table 1: Key Statistical Tests for Research Model Validation

| Statistical Test | Data Requirements | Common Research Applications | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student's t-test [13] [39] | Continuous dependent variable, categorical independent variable with 2 groups | Comparing model performance metrics between two algorithms; Testing pre-post intervention effects | Normality, homogeneity of variance, independent observations |

| One-way ANOVA [13] [39] | Continuous dependent variable, categorical independent variable with 3+ groups | Comparing multiple treatment groups or model variants simultaneously | Normality, homogeneity of variance, independent observations |

| Chi-square test [13] [39] | Two categorical variables | Testing independence between classification outcomes; Validating contingency tables | Adequate sample size, independent observations, expected frequency >5 per cell |

| Mann-Whitney U test [13] [39] | Ordinal or continuous data that violates normality | Comparing two independent groups when parametric assumptions are violated | Independent observations, ordinal measurement scale |

| Pearson correlation [13] [39] | Two continuous variables | Assessing linear relationship between predicted and actual values; Feature correlation analysis | Linear relationship, bivariate normality, homoscedasticity |

| Linear regression [13] [39] | Continuous dependent variable, continuous or categorical independent variables | Modeling relationship between model parameters and outcomes; Predictive modeling | Linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, normality of residuals |

| Logistic regression [13] [39] | Binary or categorical dependent variable, various independent variables | Classification model validation; Risk probability estimation | Linear relationship between log-odds and predictors, no multicollinearity |

Table 2: Advanced Statistical Tests for Complex Research Designs

| Statistical Test | Data Requirements | Common Research Applications | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated Measures ANOVA [39] | Continuous dependent variable measured multiple times | Longitudinal studies; Time-series model validation; Within-subject designs | Sphericity, normality of residuals, no outliers |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test [13] [39] | Paired ordinal or non-normal continuous data | Comparing matched pairs or pre-post measurements without parametric assumptions | Paired observations, ordinal measurement |