Internal vs External Validation in Drug Development: A Scientific Framework for Predictive Model Assessment

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive examination of validation methodologies for clinical prediction models and AI tools.

Internal vs External Validation in Drug Development: A Scientific Framework for Predictive Model Assessment

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive examination of validation methodologies for clinical prediction models and AI tools. It explores the foundational distinctions between internal and external validation, presents rigorous methodological approaches for implementation, addresses common challenges in model optimization, and offers comparative analysis of validation strategies. Through case studies and empirical evidence, the content establishes a scientific framework for ensuring model reliability, generalizability, and regulatory acceptance throughout the therapeutic development pipeline.

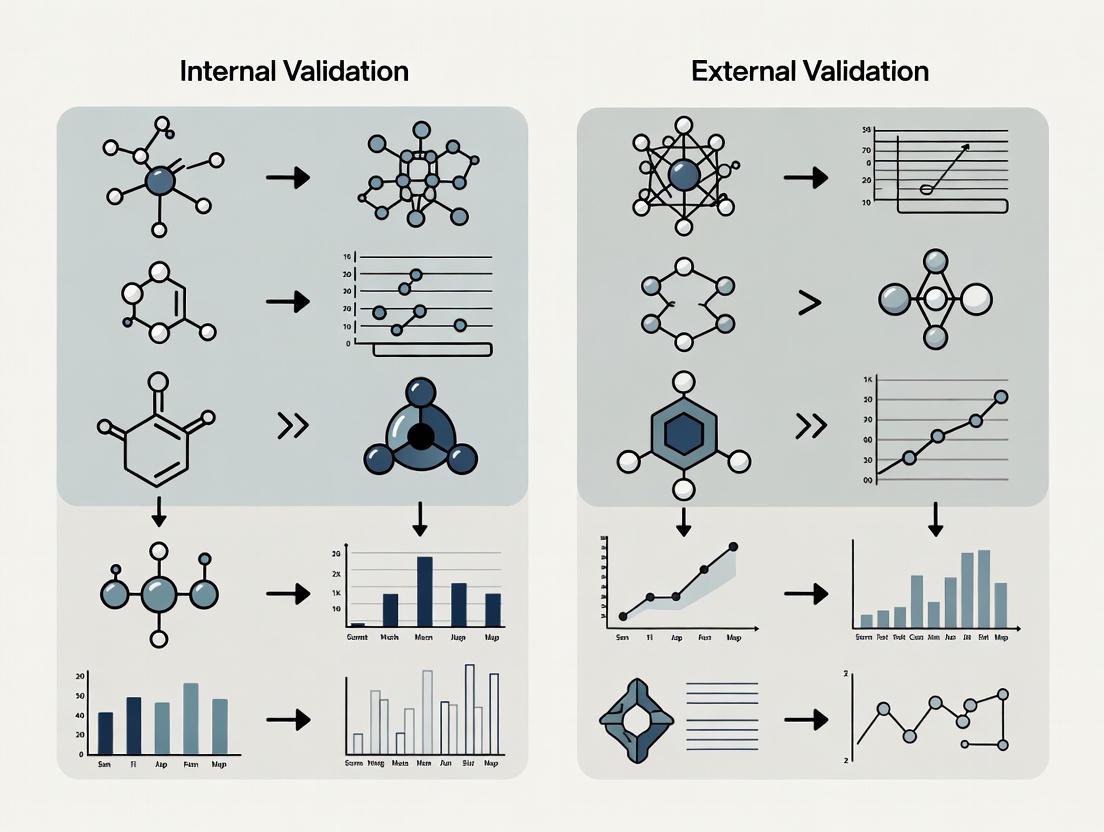

Core Principles: Defining Validation Paradigms in Biomedical Research

In the scientific development of predictive models, particularly in clinical and biomedical research, validation is a critical process that assesses the reliability and generalizability of a model's predictions. The scientific paradigm strictly differentiates between internal validation, which evaluates a model's performance on data from the same source as its development sample, and external validation, which tests the model on entirely independent data collected from different populations or settings [1] [2]. This distinction forms the cornerstone of rigorous predictive modeling, as a model must demonstrate both internal consistency and external transportability to be considered scientifically useful.

The fundamental trade-off between these validation types hinges on optimism bias (the tendency for models to perform better on the data they were trained on) and generalizability (the ability to maintain performance across diverse settings) [1]. This technical guide delineates the core definitions, methodologies, and applications of internal and external validation within the context of predictive model research for scientific professionals.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Internal Validation

Internal validation refers to a set of statistical procedures used to estimate the optimism or overfit of a predictive model when applied to new samples drawn from the same underlying population as the original development dataset [1]. Its primary purpose is to provide a realistic performance assessment that corrects for the over-optimism inherent in "apparent performance" (performance measured on the very same data used for model development) [1]. Internal validation is considered a mandatory minimum requirement for any proposed prediction model, as many failed external validations could be foreseen through rigorous internal validation procedures [1].

External Validation

External validation assesses the transportability of a model's predictive performance to data that were not used in any part of the model development process, typically originating from different locations, time periods, or populations [1] [2]. This process evaluates whether the model maintains its discriminative ability and calibration when applied to new settings, thus testing its generalizability beyond the original development context [3] [2]. External validation represents the strongest evidence for a model's potential clinical utility and real-world applicability across diverse settings.

Key Conceptual Differences

The table below summarizes the fundamental distinctions between internal and external validation approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Internal versus External Validation

| Aspect | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Same population as development data [1] | Truly independent data from different populations, centers, or time periods [1] [2] |

| Primary Objective | Correct for overfitting/optimism bias [1] | Assess generalizability/transportability [1] [2] |

| Timing | During model development [1] | After model development, using data unavailable during development [1] |

| Performance Expectation | Expected to be slightly lower than apparent performance | Ideally similar to internally validated performance; often worse in practice [1] |

| Interpretation | Tests reproducibility within the same data context [1] | Tests generalizability to new contexts [1] |

Internal Validation Methods and Protocols

Internal validation employs resampling techniques to simulate the application of a model to new samples from the same population. These methods vary in their stability, computational intensity, and suitability for different sample sizes.

Technical Methodologies

Bootstrap Validation

Bootstrap validation involves repeatedly drawing samples with replacement from the original dataset (typically of the same size as the original dataset) [1]. The model is developed on each bootstrap sample and then tested on both the bootstrap sample and the original dataset. The average optimism (difference in performance) across iterations is subtracted from the model's apparent performance to obtain an optimism-corrected estimate [1]. Conventional bootstrap may be over-optimistic, while the 0.632+ bootstrap method can be overly pessimistic, particularly with small sample sizes [4].

K-Fold Cross-Validation

In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is randomly partitioned into k equally sized folds. The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold. This process is repeated k times, with each fold used exactly once as the validation data [4]. The average performance across all k folds provides the internal validation estimate. Studies have shown that k-fold cross-validation demonstrates greater stability compared to other methods, particularly with larger sample sizes [4].

Nested Cross-Validation

Nested cross-validation (also known as double cross-validation) features an inner loop for model selection/tuning and an outer loop for performance estimation [4]. This approach is particularly important when model development involves hyperparameter optimization (e.g., in penalized regression or machine learning). The outer loop provides a nearly unbiased performance estimate, while the inner loop selects optimal parameters for each training set [4]. Performance can fluctuate depending on the regularization method used for model development [4].

Comparative Performance in Simulation Studies

Simulation studies provide quantitative evidence for selecting appropriate internal validation methods based on sample size and data characteristics:

Table 2: Internal Validation Method Performance Based on Simulation Studies [4]

| Method | Recommended Sample Size | Stability | Optimism Correction | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train-Test Split | Very large only (n > 1000) [1] | Unstable, especially with small holdout sets [4] | Moderate | "Only works when not needed" - inefficient in small samples [1] |

| Conventional Bootstrap | Medium to Large (n > 500) | Moderate | Can be over-optimistic [4] | Requires 100+ iterations [4] |

| 0.632+ Bootstrap | Medium to Large (n > 500) | Moderate | Overly pessimistic with small samples (n=50-100) [4] | Complex weighting scheme |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Small to Large (n=75+) [4] | High stability [4] | Appropriate | Preferred for Cox penalized models in high-dimensional settings [4] |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Small to Large (n=75+) [4] | Moderate, with fluctuations [4] | Appropriate | Essential when model selection is part of fitting [4] |

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for k-fold cross-validation, one of the recommended internal validation methods:

External Validation Methods and Protocols

Validation Typology

External validation encompasses several distinct approaches based on the relationship between development and validation datasets:

- Full External Validation: Conducted by different investigators using completely independent data collected after model development [1] [2]. This represents the strongest form of validation.

- Temporal Validation: The model is validated on data from the same institution(s) but collected from a later time period than the development data [1].

- Geographic Validation: Validation performed on data from different centers or geographic locations than where the model was developed [2].

- Internal-External Cross-Validation: A hybrid approach where data are repeatedly split by natural groupings (e.g., centers in a multicenter study), with each group left out once for validation of a model developed on the remaining groups [1].

Performance Assessment Metrics

External validation requires comprehensive assessment of both discrimination and calibration:

Table 3: Key Metrics for External Validation Performance Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Interpretation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | Area Under ROC Curve (AUC/AUROC) [3] | Ability to distinguish between outcome classes | CSM-4 sepsis model: AUROC=0.80 at 4h [3] |

| Discrimination | Concordance Index (C-index) [2] | Overall ranking accuracy of predictions | AI lung cancer model: Superior to TNM staging [2] |

| Calibration | Brier Score [4] | Overall accuracy of probability estimates | Integrated Brier score for time-to-event data [4] |

| Calibration | Calibration Plots/Slope | Agreement between predicted and observed risks | Slope <1 indicates overfitting [1] |

| Clinical Utility | Hazard Ratios [2] | Risk stratification performance | AI model: HR=3.34 vs 1.98 for TNM in stage I [2] |

Implementation Workflow

The external validation process follows a systematic approach to ensure comprehensive assessment:

Case Studies in Biomedical Research

Internal Validation: High-Dimensional Prognosis Models

A simulation study focusing on transcriptomic data in head and neck tumors (n=76 patients) compared internal validation strategies for Cox penalized regression models with time-to-event endpoints [4]. The study simulated datasets with clinical variables and 15,000 transcripts at sample sizes of 50, 75, 100, 500, and 1000 patients, with 100 replicates each [4]. Key findings included:

- Train-test validation showed unstable performance across sample sizes

- Conventional bootstrap was over-optimistic in its performance estimates

- 0.632+ bootstrap was overly pessimistic, particularly with small samples (n=50 to n=100)

- K-fold cross-validation and nested cross-validation improved performance with larger sample sizes, with k-fold demonstrating greater stability [4]

The study concluded that k-fold cross-validation and nested cross-validation are recommended for internal validation of Cox penalized models in high-dimensional time-to-event settings [4].

External Validation: Sepsis Mortality Prediction Models

A 2025 external validation study assessed eight different mortality prediction models in intensive care units for 750 patients with sepsis [3]. The study clarified which variables from each model were routinely collected in medical care and externally validated the models by calculating AUROC for predicting 30-day mortality. Key results demonstrated:

- The CSM-4 model performed best 4 hours after ICU admission (AUROC=0.80) using few frequently collected variables

- The ANZROD 24 model performed best 24 hours after admission (AUROC=0.83)

- Time after admission determines which prediction model is most useful

- Early after ICU admission, sepsis-specific models performed slightly better, while at 24 hours, general models not specific for sepsis performed well [3]

External Validation: AI for Lung Cancer Recurrence Risk

A 2025 study externally validated a machine learning-based survival model that incorporated preoperative CT images and clinical data to predict recurrence after surgery in patients with lung cancer [2]. The model was developed on 1,015 patients and validated on an external cohort of 252 patients. Key findings included:

- The ML model outperformed conventional TNM staging for stratifying stage I patients into high- and low-risk groups

- Higher hazard ratios were observed in external validation (HR=3.34) compared to conventional staging by tumor size (HR=1.98)

- The model showed significant correlations with established pathologic risk factors for recurrence (poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, pleural invasion) [2]

- The model successfully identified high-risk stage I patients who might benefit from more personalized treatment decisions and follow-up strategies [2]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The implementation of rigorous validation methodologies requires specific technical resources and computational tools:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Validation Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Validation | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Management | HL7/API Interfaces [5] | Real-time data integration from laboratory systems | Standardized healthcare data exchange protocols |

| Computational | K-fold Cross-Validation [4] | Robust internal performance estimation | Typically 5-10 folds; repeated for stability |

| Computational | Bootstrap Resampling [1] | Optimism correction for model performance | 100+ iterations recommended [4] |

| Biomarkers | Transcriptomic Data [4] | High-dimensional predictors for prognosis | 15,000+ transcripts in simulation studies [4] |

| Imaging | CT Radiomic Features [2] | Image-derived biomarkers for AI models | Preoperative CT scans for recurrence prediction [2] |

| Molecular | BioFire Molecular Panels [5] | Standardized inputs for infectious disease models | FDA-approved comprehensive molecular panels |

| Validation | Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) [5] | Expert oversight of ML training data | Multiple infectious disease experts for consistency |

Integration Framework for Comprehensive Validation

The most robust validation strategy incorporates both internal and external components throughout the model development lifecycle. The following framework illustrates this integrated approach:

This integrated approach emphasizes that internal and external validation are complementary rather than competing processes. Internal validation provides the necessary foundation for model refinement and optimism correction, while external validation establishes generalizability and real-world applicability [1]. The scientific community increasingly recognizes that both components are essential for establishing a prediction model's credibility and potential clinical utility.

The Critical Role of Validation in Clinical Prediction Models and AI Tools

Clinical prediction models (CPMs) and artificial intelligence (AI) tools are transforming healthcare by forecasting individual patient risks for diagnostic and prognostic outcomes. Their safe and effective integration into clinical practice hinges on rigorous validation—the systematic process of evaluating a model's performance and reliability. Validation provides the essential evidence that a predictive algorithm is accurate, reliable, and fit for its intended clinical purpose [6] [7]. Without proper validation, there is a substantial risk of deploying models with optimistic or unknown performance, potentially leading to harmful clinical decisions [1].

The scientific discourse on validation centers on a crucial dichotomy: internal validation, which assesses model performance on data from the same underlying population used for development, and external validation, which evaluates performance on data from new, independent populations and settings [6]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these validation paradigms, offering researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the methodologies and frameworks necessary to robustly validate clinical predictive algorithms.

Core Concepts: Internal versus External Validation

Defining the Paradigms

Internal Validation: Internal validation assesses the reproducibility of an algorithm's performance on data distinct from the development set but derived from the exact same underlying population. Its primary goal is to quantify and correct for in-sample optimism or overfitting, which is the tendency of a model to perform better on its training data than on unseen data from the same population [6] [7]. It provides an optimism-corrected estimate of performance for the original setting [6].

External Validation: External validation assesses the transportability of a model to other settings beyond those considered during its development [6]. It examines whether the model's predictions hold true in different settings, such as new healthcare institutions, patient populations from different geographical regions, or data collected at a later point in time [1] [6]. It is often regarded as a gold standard for establishing model credibility [7].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of and recommended methodologies for internal and external validation.

Table 1: Comparison of Internal and External Validation

| Aspect | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | How well will the model perform in the source population? | Will the model work in a new, target population/setting? |

| Primary Goal | Quantify and correct for overfitting (optimism) [7]. | Assess transportability and generalizability [6]. |

| Key Terminology | Reproducibility, Optimism-Correction [6] [7]. | Transportability, Generalizability [6] [7]. |

| Recommended Methods | Bootstrapping, Cross-Validation [1] [6]. | Temporal, Geographical, and Domain Validation [6]. |

Methodologies for Internal Validation

Internal validation is not merely a box-ticking exercise; it is a necessary component of model development that provides a realistic estimate of performance in the absence of a readily available external dataset [1]. A robust internal validation is often sufficient, especially when the development dataset is large and the intended use population matches the development population [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is widely considered the preferred approach for internal validation as it makes efficient use of the available data and provides a reliable estimate of optimism [1].

- Resampling: Generate a large number (typically 500-2000) of bootstrap samples from the original development dataset. Each sample is drawn with replacement and is of the same size as the original dataset [6].

- Model Development: On each bootstrap sample, develop a new model following the exact same steps used to create the original model. This includes any data pre-processing, variable selection, and parameter estimation procedures [1].

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the performance (e.g., discrimination, calibration) of each bootstrap-derived model on two sets:

- The bootstrap sample (test performance).

- The original development dataset (training performance).

- Optimism Calculation: Calculate the optimism for each bootstrap sample as the difference between the test performance and the training performance.

- Optimism Correction: Average the optimism estimates from all bootstrap samples and subtract this value from the apparent performance (the performance of the original model on the original data) to obtain the optimism-corrected performance estimate [1].

Protocol 2: k-Fold Cross-Validation

This method is particularly useful when the sample size is limited, but it can be computationally intensive and may show more variability than bootstrapping.

- Data Partitioning: Randomly split the entire development dataset into k equally sized, mutually exclusive folds (common choices are k=5 or k=10).

- Iterative Training and Testing: For each of the k iterations:

- Designate one fold as the temporary validation set.

- Combine the remaining k-1 folds to form the training set.

- Develop a model on the training set using the full pre-specified modeling strategy.

- Test this model on the held-out validation fold and record its performance.

- Performance Aggregation: Aggregate the performance metrics (e.g., average them) from the k iterations to obtain a single cross-validated performance estimate. To enhance stability, the entire k-fold procedure can be repeated multiple times (e.g., 10x10-fold cross-validation) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Internal Validation Reagents

Table 2: Essential Components for Internal Validation

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Development Dataset | The single, source dataset containing the patient population used for initial model training. |

| Bootstrap Sample | A sample drawn with replacement from the development dataset, used to simulate new training sets. |

| Optimism | The difference between a model's performance on its training data vs. new data from the same population; the quantity to be estimated and corrected. |

| Optimism-Corrected Performance | The final, more realistic estimate of how the model would be expected to perform in the source population. |

| Discrimination Metric (e.g., C-index) | A measure of the model's ability to distinguish between cases and non-cases. |

| Calibration Metric | A measure of the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. |

Methodologies for External Validation

External validation moves beyond the source data to test a model's performance in real-world conditions. It is the only way to truly assess a model's generalizability and is critical for determining its potential for broad clinical implementation [6].

A Framework for External Validity: Types of Generalizability

External validity can be broken down into three distinct types, each serving a unique goal and answering a specific question about the model's applicability [6].

- Temporal Validity: Assesses the performance of an algorithm over time at the development setting or in a new setting. This is crucial for understanding and detecting data drift—changes in the data distribution or patient population over time that can degrade model performance. It is typically assessed by testing the algorithm on a dataset from the same institution(s) but from a later time period [6].

- Geographical Validity: Assesses the generalizability of an algorithm to a different physical location, such as a new hospital, region, or country. This type of validation investigates heterogeneity across places and is required when an algorithm is intended for use outside its original development location. A powerful design for this is leave-one-site-out cross-validation within a multicenter study [6].

- Domain Validity: Assesses the generalizability of an algorithm to a different clinical context. This could involve changes in the medical background (e.g., emergency vs. surgical patients), medical setting (e.g., nursing home vs. hospital), or patient demographics (e.g., adult vs. pediatric populations). Performance is often better in "closely related" domains than in "distantly related" ones [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: The Internal-External Cross-Validation

This hybrid approach, often used in individual participant data meta-analysis (IPD-MA) or multicenter studies, provides a robust and efficient method for assessing external validity during the development phase [1] [6].

- Data Structuring: Assemble a dataset comprising multiple natural clusters. These could be different clinical studies (in an IPD-MA), different hospitals (in a multicenter study), or data from different calendar years [1].

- Iterative Validation Loop: For each cluster i in the dataset:

- Training Set: Designate all data except that from cluster i as the training set.

- Test Set: Designate the data from cluster i as the validation set.

- Model Development: Develop a model from scratch using only the training set.

- Model Testing: Validate this model on the held-out test set (cluster i) and record its performance.

- Performance Synthesis: Synthesize the performance metrics obtained from each of the held-out clusters to understand the model's performance variation across different settings.

- Final Model Development: After completing the loop, develop the final model to be used or published on the entire, pooled dataset. This final model is considered an 'internally-externally validated model' [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: External Validation Reagents

Table 3: Essential Components for External Validation

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Target Population | The clearly defined intended population and setting for the model's use; the focus of "targeted validation" [7]. |

| External Validation Dataset | A completely independent dataset from the target population, not used in any phase of model development. |

| Heterogeneity Assessment | The evaluation of differences in case-mix, baseline risk, and predictor-outcome associations across settings. |

| Model Updating | Techniques (e.g., recalibration, refitting) to adjust a model's performance for a new local setting. |

| Open Datasets (e.g., VitalDB) | Publicly accessible datasets that provide a highly practical resource for performing external validation, as demonstrated in a study predicting acute kidney injury [8]. |

Quantitative Data in Validation Studies

The performance of a clinical prediction model is quantified using specific metrics that evaluate different aspects of its predictive ability. The table below summarizes common performance metrics and their interpretation, providing a framework for comparing models across validation studies.

Table 4: Key Performance Metrics in Model Validation

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Interpretation and Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | C-index (AUC/AUROC) | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between patients with and without the outcome. A value of 0.5 is no better than chance; 1.0 is perfect discrimination [7] [8]. | A model for AKI prediction achieved an internal AUROC of 0.868 and an external AUROC of 0.757 on the VitalDB dataset, indicating good but reduced discrimination in the external population [8]. |

| Calibration | Calibration Slope & Intercept | Assesses the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. A slope of 1 and intercept of 0 indicate perfect calibration. Deviations suggest over- or under-prediction [6]. | Poor calibration in a new setting often necessitates model updating (recalibration) before local implementation [6]. |

| Overall Performance | Brier Score | The mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes. Ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 represents perfect accuracy. | A lower Brier score indicates better overall accuracy of probabilistic predictions. |

| Clinical Usefulness | Net Benefit | A decision-analytic measure that quantifies the clinical value of using a prediction model for decision-making, by weighting true positives against false positives at a specific probability threshold [6]. | Used to compare the model against default strategies of "treat all" or "treat none" and to evaluate the impact of different decision thresholds. |

Validation is the cornerstone of credible clinical prediction models and AI tools. A rigorous, multi-faceted approach is non-negotiable. This begins with robust internal validation via bootstrapping to quantify optimism, providing a realistic performance baseline [1]. This must be followed by targeted external validation efforts designed to explicitly test performance in the model's intended clinical environment, whether that involves assessing temporal, geographical, or domain generalizability [6] [7].

The future of validation will be shaped by several key developments. The concept of "targeted validation" sharpens the focus on the intended use population, potentially reducing research waste and preventing misleading conclusions from irrelevant validation studies [7]. Furthermore, the adoption of structured reporting guidelines like TRIPOD and the forthcoming TRIPOD-AI will enhance the transparency, quality, and reproducibility of prediction model studies [6]. Finally, the strategic use of open datasets for external validation, as demonstrated in contemporary research, provides a viable and powerful pathway for demonstrating model generalizability in an era of data access challenges [8]. By adhering to these rigorous validation principles, researchers and drug developers can ensure that clinical predictive algorithms are not only statistically sound but also safe, effective, and reliable in diverse real-world settings.

In the scientific method as applied to predictive model development, validation is the cornerstone that separates speculative concepts from reliable tools. The process establishes that a model works satisfactorily for individuals other than those from whose data it was derived [9]. Within a broader thesis on validation research, this whitepaper addresses the critical pathway from internal checks to external verification, providing researchers and drug development professionals with rigorous methodologies for assessing model performance and generalizability.

The fundamental challenge in prediction model development lies in overcoming overfitting—where models correspond too closely to idiosyncrasies in the development dataset [10]. Internal validation focuses on reproducibility and overfitting within the original patient population, while external validation focuses on transportability and potential clinical benefit in new settings [9]. Without proper validation, models may produce inaccurate predictions and interpretations despite appearing successful during development [11].

Theoretical Foundations: Internal Versus External Validation

Defining the Validation Spectrum

Validation strategies vary in rigor and purpose, creating a spectrum from internal reproducibility checks to external generalizability assessments:

- Internal Validation: Makes use of the same data from which the model was derived, primarily focusing on quantifying and reducing optimism in performance estimates [10]. Common approaches include split-sample, cross-validation, and bootstrapping [10].

- Temporal Validation: An intermediate approach where the validation cohort is sampled at a different time point from the development cohort, for instance by developing a model on patients treated from 2010-2015 and validating on patients from the same hospital from 2015-2020 [10].

- External Validation: Tests the original prediction model in a structurally different set of new patients, which may come from different regions, care settings, or have different underlying diseases [10]. Independent external validation occurs when the validation cohort was assembled completely separately from the development cohort [10].

Conceptual Workflow for Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and progression through different validation stages in a comprehensive model assessment strategy:

Quantitative Performance Metrics for Model Assessment

Core Metrics for Classification and Survival Models

A multifaceted approach to performance assessment is essential, as no single metric comprehensively captures model quality [12]. The following table summarizes key performance metrics across different model types:

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | Area Under ROC (AUROC) | Probability model ranks random positive higher than random negative; 0.5=random, 1.0=perfect | Binary classification |

| Concordance Index (C-index) | Similar to AUROC for time-to-event data | Survival models | |

| F1 Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | Imbalanced datasets | |

| Calibration | Calibration Plot | Agreement between predicted probabilities and observed frequencies | Risk prediction models |

| Integrated Brier Score | Overall measure of prediction error | Survival models | |

| Clinical Utility | Net Benefit Analysis | Clinical value weighing benefits vs. harms | Decision support tools |

| Decision Curve Analysis | Net benefit across probability thresholds | Clinical implementation |

Performance Benchmarks from Validation Studies

Recent validation studies across medical domains demonstrate the expected performance differential between internal and external validation:

| Study Context | Internal Validation Performance | External Validation Performance | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer OS Prediction [13] | C-index: 0.882 (95% CI: 0.874-0.890)3-year AUC: 0.913 | C-index: 0.872 (95% CI: 0.829-0.915)3-year AUC: 0.892 | C-index: -0.010AUC: -0.021 |

| Early-Stage Lung Cancer Recurrence [2] | Hazard Ratio: 1.71 (stage I)1.85 (stage I-III) | Hazard Ratio: 3.34 (stage I)3.55 (stage I-III) | HR improvement in external cohort |

| COVID-19 Diagnostic Model [14] | Not specified | Average AUC: 0.84Average calibration: 0.17 | Moderate impact from data similarity |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Internal Validation Methodologies

Split-Sample Validation

A cohort of patients is randomly divided into development and internal validation cohorts, typically with two-thirds of patients used for model development and one-third for validation [10]. This approach is generally inefficient in small datasets as it develops a poorer model on reduced sample size and provides unstable validation findings [1].

Cross-Validation

In k-fold cross-validation, the model is developed on k-1 folds of the population and tested on the remaining fold. This process is repeated k times, with each fold serving as the test set once [10]. For high-dimensional settings with limited samples, k-fold cross-validation demonstrates greater stability than train-test or bootstrap approaches [4].

Bootstrapping

Bootstrapping is a resampling method where numerous "new" cohorts are randomly selected by sampling with replacement from the original development population [10]. The model performance is tested in each resampled cohort and results are pooled to determine internal validation performance. The 0.632+ bootstrap method provides a bias-corrected estimate [4].

External Validation Protocol

A rigorous external validation protocol involves these critical methodological steps:

Model Selection: Choose an existing prediction model with clearly documented predictor variables and their coefficients, or the complete model equation [10].

Validation Cohort Definition: Assemble a new patient cohort that structurally differs from the development cohort through different locations, care settings, or time periods [10].

Predicted Risk Calculation: Compute the predicted risk for each individual in the external validation cohort using the original prediction formula and local predictor values [10].

Performance Assessment: Compare predicted risks to observed outcomes using discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility metrics [10] [12].

Heterogeneity Evaluation: Assess differences in patient characteristics, outcome incidence, and predictor effects between development and validation cohorts [1].

The following workflow details the complete experimental protocol for end-to-end model validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential methodological components for rigorous validation studies include:

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap Resampling | Estimates optimism correction by sampling with replacement | Preferred for internal validation; requires 100+ iterations [10] |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | Robust performance estimation in limited samples | Recommended for high-dimensional settings; k=5 or 10 typically [4] |

| Time-Dependent ROC Analysis | Evaluates discrimination for time-to-event data | Accounts for censoring in survival models [13] |

| Calibration Plots | Visualizes agreement between predicted and observed risks | Should include smoothed loess curves with confidence intervals [12] |

| Decision Curve Analysis | Quantifies clinical net benefit across threshold probabilities | Evaluates clinical utility, not just statistical performance [12] |

| Similarity Metrics | Quantifies covariate shift between development and validation datasets | Essential for interpreting external validation results [14] |

Methodological Pitfalls and Mitigation Strategies

Critical Errors in Validation Design

Several methodological pitfalls can severely compromise validation results while remaining undetectable during internal evaluation [11]:

Violation of Independence Assumption: Applying oversampling, feature selection, or data augmentation before data splitting creates data leakage. For example, applying oversampling before data splitting artificially inflated F1 scores by 71.2% for predicting local recurrence in head and neck cancer [11].

Inappropriate Performance Metrics: Using accuracy for imbalanced datasets or relying solely on discrimination without assessing calibration. In imbalanced datasets, a model that always predicts the majority class can have high accuracy while being clinically useless [12].

Batch Effects: Systematic differences in data collection or processing between development and validation cohorts. One pneumonia detection model achieved an F1 score of 98.7% internally but correctly classified only 3.86% of samples from a new dataset of healthy patients due to batch effects [11].

Recommended Mitigation Approaches

Temporal Splitting: Instead of random data splitting, use temporal validation where the validation cohort comes from a later time period than the development cohort [1] [10].

Multiple Performance Metrics: Report discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility metrics together for a comprehensive assessment [12].

Internal-External Cross-Validation: In multicenter studies, leave out each center once for validation of a model developed on the remaining centers, with the final model based on all available data [1].

The validation of prediction models deserves more recognition in the scientific process [9]. Despite methodological advances, external validation remains uncommon—only about 5% of prediction model studies mention external validation in their title or abstract [10]. This validation gap hinders the emergence of critical, well-founded knowledge on clinical prediction models' true value.

Researchers should consider that developing a new model with insufficient sample size is often less valuable than conducting a rigorous validation of an existing model [9]. As we move toward personalized medicine with rapidly evolving therapeutic options, validation must be recognized not as a one-time hurdle but as an ongoing process throughout a model's lifecycle [14] [9]. Through rigorous validation practices, the scientific community can ensure that prediction models fulfill their promise to enhance patient care and treatment outcomes.

In the realm of statistical prediction and machine learning, the ultimate goal is to develop models that generalize effectively to new, unseen data. However, this objective is persistently challenged by the dual problems of overfitting and optimism. Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying patterns in the training data but also the noise and random fluctuations, essentially "memorizing" the training set rather than learning to generalize [15] [16]. This phenomenon is particularly problematic in scientific research and drug development, where models must reliably inform critical decisions.

The statistical concept of "optimism" refers to the systematic overestimation of a model's performance when evaluated on the same data used for its training. This optimism bias arises because the model has already seen and adapted to the specific peculiarities of the training sample, performance metrics appear better than they would on independent data [1]. Understanding and correcting for this optimism is fundamental to building trustworthy predictive models in clinical research, where inaccurate predictions can directly impact patient care and therapeutic development.

This paper situates the discussion of overfitting and optimism within the broader framework of model validation, distinguishing between internal validation—assessing model performance on data from the same population—and external validation—evaluating performance on data from different populations, institutions, or time periods [17] [9]. While internal validation techniques aim to quantify and correct for optimism, external validation provides the ultimate test of a model's transportability and real-world utility.

The Statistical Nature of Overfitting and the Bias-Variance Tradeoff

Conceptual Foundations of Overfitting

Overfitting represents a fundamental failure in model generalization. An overfit model exhibits low bias but high variance, meaning it performs exceptionally well on training data but poorly on unseen test data [15] [18]. This occurs when a model becomes excessively complex relative to the amount and quality of training data, allowing it to capture spurious relationships that do not reflect true underlying patterns.

The analogy of student learning effectively illustrates this concept: a student who memorizes textbook answers without understanding underlying concepts will ace practice tests but fail when confronted with novel questions on the final exam [15]. Similarly, an overfit model memorizes the training data but cannot extrapolate to new situations.

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

The concepts of overfitting and its opposite, underfitting, are governed by the bias-variance tradeoff, which represents a core challenge in statistical modeling [15] [16]. This framework helps understand the relationship between model complexity and generalization error:

- High Bias (Underfitting): The model is too simple to capture underlying patterns, leading to high errors on both training and test data.

- High Variance (Overfitting): The model is too complex and sensitive to training data fluctuations, leading to low training error but high test error.

- Balanced Model: Achieves optimal complexity with low bias and low variance, performing well on both training and test data [15].

Table 1: Characteristics of Model Fit States

| Feature | Underfitting | Overfitting | Good Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Poor on train & test | Great on train, poor on test | Great on train & test |

| Model Complexity | Too Simple | Too Complex | Balanced |

| Bias | High | Low | Low |

| Variance | Low | High | Low |

| Primary Fix | Increase complexity/features | Add more data/regularize | Optimal achieved |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between model complexity, error, and the bias-variance tradeoff:

Quantifying Optimism in Predictive Performance

The Optimism Principle

Statistical optimism refers to the difference between a model's apparent performance (measured on the training data) and its true performance (expected performance on new data) [1]. This bias emerges because the same data informs both model building and performance assessment, creating an overoptimistic view of model accuracy. The optimism principle states that:

Optimism = E[Apparent Performance] - E[True Performance]

Where E[Apparent Performance] represents expected performance on training data and E[True Performance] represents expected performance on new data. In practice, optimism is always positive, meaning models appear better than they truly are.

Mathematical Formulations

For common performance metrics, optimism can be quantified mathematically. In linear regression, the relationship between expected prediction error and model complexity follows known distributions that allow for optimism correction. The expected optimism increases with model complexity (number of parameters) and decreases with sample size [1].

For logistic regression models predicting binary outcomes, the optimism can be quantified through measures like the overfitting-induced bias in hazard ratios or odds ratios. Research has shown that very high odds ratios (e.g., 36.0 or more) are often required for a new biomarker to substantially improve predictive ability beyond existing markers, highlighting how standard significance testing (small p-values) can be misleading without proper validation [17].

Internal Validation Techniques for Optimism Correction

Core Methodologies

Internal validation techniques aim to provide realistic estimates of model performance by correcting for optimism within the available dataset. These methods include:

4.1.1 Bootstrapping Techniques Bootstrapping is widely considered the preferred approach for internal validation of prediction models [1]. This method involves repeatedly sampling from the original dataset with replacement to create multiple bootstrap samples. The model building process is applied to each bootstrap sample, and performance is evaluated on both the bootstrap sample and the original dataset. The average difference between these performances provides an estimate of the optimism, which can then be subtracted from the apparent performance.

Table 2: Internal Validation Methods Comparison

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapping | Repeated sampling with replacement; full modeling process on each sample | Most efficient use of data; preferred for small samples | Computationally intensive |

| K-fold Cross-Validation | Data divided into K subsets; iteratively use K-1 for training, 1 for validation [16] | Reduced variance compared to single split | Can be optimistic if modeling steps not repeated |

| Split-Sample | Random division into training and test sets (e.g., 70/30) | Simple to implement | Inefficient data use; unstable in small samples [1] |

| Internal-External Cross-Validation | Natural splits by study, center, or time period | Provides assessment of transportability | Requires multiple natural partitions |

4.1.2 Cross-Validation Protocols In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is partitioned into k equally sized folds or subsets [16]. The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold, repeating this process k times with each fold serving once as the validation set. The performance estimates across all k folds are then averaged to produce a more robust assessment less affected by optimism.

Implementation Considerations

The key to effective internal validation lies in repeating the entire model building process—including any variable selection, transformation, or hyperparameter tuning steps—within each validation iteration [1]. Failure to do so can lead to substantial underestimation of optimism. For small datasets (median sample size in many clinical prediction models is only 445 subjects), bootstrapping is particularly recommended over split-sample methods, which perform poorly when sample size is limited [1].

External Validation: Beyond Optimism to Generalizability

The External Validation Imperative

While internal validation corrects for statistical optimism, external validation assesses a model's generalizability to different populations, settings, or time periods [17] [9]. External validation involves applying the model to completely independent data that played no role in model development and ideally was unavailable to the model developers.

True external validation requires "transportability" assessment—evaluating whether the model performs satisfactorily in different clinical settings, patient populations, or with variations in measurement techniques [9]. This is distinct from "reproducibility," which assesses performance in similar settings.

Methodological Approaches

5.2.1 Temporal and Geographic Validation Temporal validation assesses model performance on patients from the same institutions but from a later time period, testing stability over time. Geographic validation evaluates performance on patients from different institutions or healthcare systems, testing transportability across settings [1].

5.2.2 Internal-External Cross-Validation In datasets with natural clustering (e.g., multiple centers in a clinical trial), internal-external cross-validation systematically leaves out one cluster at a time (e.g., one clinical center), develops the model on the remaining data, and validates on the left-out cluster [1]. This approach provides insights into a model's potential generalizability while still using all data for final model development.

5.2.3 Heterogeneity Assessment More direct than global performance measures are tests for heterogeneity in predictor effects across settings or time. This can be achieved through random effects models (with many studies) or testing interaction terms (e.g., "predictor × study" or "predictor × calendar time") [1].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive validation process from model development through to external validation:

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Sample Size Considerations

Adequate sample size is critical for both model development and validation. For external validation studies, sample size calculations should ensure sufficient precision for performance measure estimates [9]. One framework recommends that external validation studies require a minimum of 100 events and 100 non-events for binary outcomes to precisely estimate key performance measures like the C-statistic and calibration metrics.

For model development, the events per variable (EPV) ratio—the number of events divided by the number of candidate predictor parameters—should ideally be at least 10-20 to minimize overfitting [1]. In biomarker studies with high-dimensional data (e.g., genomic markers), regularized regression methods (LASSO, ridge regression) are preferred to conventional variable selection to mitigate overfitting.

Performance Measures and Evaluation

Comprehensive validation requires multiple performance measures to assess different aspects of model performance:

6.2.1 Discrimination Measures

- C-statistic (AUC): For binary outcomes, measures the model's ability to distinguish between cases and non-cases

- R²: Proportion of variance explained (for continuous outcomes)

6.2.2 Calibration Measures

- Calibration-in-the-large: Comparison of average predicted risk versus observed risk

- Calibration slope: Degree of overfitting/underfitting (ideal value = 1)

- Calibration plots: Visual assessment of predicted versus observed risks

6.2.3 Clinical Utility

- Decision curve analysis: Net benefit across different decision thresholds

- Classification measures: Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values at clinically relevant thresholds

Research Reagent Solutions: Methodological Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Validation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Methods | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Bootstrapping, k-fold cross-validation, repeated hold-out | Estimates and corrects for optimism in performance measures |

| Regularization Methods | Ridge regression, LASSO, elastic net | Prevents overfitting in high-dimensional data; performs variable selection |

| Performance Measures | C-statistic, Brier score, calibration plots, decision curve analysis | Comprehensively assesses discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility |

| Software/Computational | R packages (rms, glmnet, caret), Python (scikit-learn), Amazon SageMaker [16] | Implements validation protocols; detects overfitting automatically |

| Statistical Frameworks | TRIPOD+AI statement [9], REMARK guidelines (biomarkers) [17] | Reporting standards ensuring complete and transparent methodology |

The statistical underpinnings of overfitting and optimism reveal fundamental truths about the limitations of predictive modeling. While internal validation techniques provide essential corrections for optimism, they cannot fully replace the rigorous assessment provided by external validation [9]. The scientific community, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, must prioritize both internal and external validation to establish trustworthy prediction models.

Future directions should emphasize ongoing validation as a continuous process rather than a one-time event, especially given the dynamic nature of medical practice and evolving patient populations [9]. Furthermore, impact studies assessing whether prediction models actually improve patient outcomes when implemented in clinical practice represent the ultimate validation of a model's value beyond statistical performance metrics.

By understanding and addressing the statistical challenges of overfitting and optimism, researchers can develop more robust, reliable predictive models that genuinely advance scientific knowledge and improve decision-making in drug development and clinical care.

In contemporary drug development, the translation of preclinical findings into clinically effective therapies remains a significant challenge. Validation strategies are paramount in bridging this gap, ensuring that predictive models and experimental results are both reliable and generalizable. The validation process is fundamentally divided into two complementary phases: internal validation, which assesses a model's performance on the originating dataset and aims to mitigate optimism bias, and external validation, which evaluates its performance on entirely independent data, establishing generalizability and real-world applicability [13] [4]. Despite recognized frameworks, critical gaps persist, particularly in the transition from internal to external validation and in the handling of high-dimensional data, which can lead to failed clinical trials and inefficient resource allocation. This paper examines these gaps within the current drug development landscape, provides a quantitative analysis of prevailing methodologies, and outlines detailed experimental protocols and tools to bolster validation robustness.

Quantitative Landscape of Validation in Current Drug Development

An analysis of the active Alzheimer's disease (AD) drug development pipeline for 5 reveals a vibrant ecosystem with 138 drugs across 182 clinical trials [19]. This landscape provides a context for understanding the scale at which robust validation is required. The following tables summarize key quantitative data from recent studies, highlighting the performance of prognostic models and the characteristics of the current drug pipeline.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of a Validated Prognostic Model in Cervical Cancer (Sample Size: 13,592 patients from SEER database) [13]

| Validation Cohort | Sample Size | C-Index (95% CI) | 3-Year OS AUC | 5-Year OS AUC | 10-Year OS AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training (TC) | 9,514 | 0.882 (0.874–0.890) | 0.913 | 0.912 | 0.906 |

| Internal (IVC) | 4,078 | 0.885 (0.873–0.897) | 0.916 | 0.910 | 0.910 |

| External (EVC) | 318 | 0.872 (0.829–0.915) | 0.892 | 0.896 | 0.903 |

Table 2: Simulation Study of Internal Validation Methods for High-Dimensional Prognosis Models (Head and Neck Cancer Transcriptomic Data) [4]

| Validation Method | Sample Size (N) | Performance Stability | Key Finding / Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Train-Test (70/30) | 50 - 1000 | Unstable | Showed unstable performance across sample sizes. |

| Conventional Bootstrap | 50 - 100 | Over-optimistic | Particularly over-optimistic with small samples. |

| 0.632+ Bootstrap | 50 - 100 | Over-pessimistic | Particularly over-pessimistic with small samples. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | 500 - 1000 | Stable | Recommended for its greater stability. |

| Nested Cross-Validation | 500 - 1000 | Fluctuating | Performance fluctuated with the regularization method. |

Table 3: Profile of the 2025 Alzheimer's Disease Drug Development Pipeline [19]

| Category | Number of Agents | Percentage of Pipeline | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Novel Drugs | 138 | - | Across 182 clinical trials. |

| Small Molecule DTTs | ~59 | 43% | Disease-Targeted Therapies. |

| Biological DTTs | ~41 | 30% | e.g., Monoclonal antibodies, vaccines. |

| Cognitive Enhancers | ~19 | 14% | Symptomatic therapies. |

| Neuropsychiatric Symptom Drugs | ~15 | 11% | e.g., For agitation, psychosis. |

| Repurposed Agents | ~46 | 33% | Approved for another indication. |

| Trials Using Biomarkers | ~49 | 27% | As primary outcomes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Internal and External Validation

Protocol 1: Internal-External Validation of a Clinical Prognostic Model

This protocol is based on a retrospective study developing a nomogram for predicting overall survival (OS) in cervical cancer [13].

- Objective: To develop and validate a prognostic model for predicting 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year overall survival in cervical cancer patients.

- Data Source and Cohort Selection:

- Primary data was extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database for patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2020.

- Inclusion Criteria: Primary tumor site clearly identified as the cervix (C53), diagnosis between 2000-2020, and behavior code indicating malignancy.

- Exclusion Criteria: Non-cancer-related deaths, missing data (tumor type, grade, size, treatment), and incomplete survival records.

- A total of 13,592 patient records were obtained and randomly split into a training cohort (TC, n=9,514) and an internal validation cohort (IVC, n=4,078) using a 7:3 ratio and random number tables.

- Predictor Variables and Endpoint:

- Ten initial predictors were selected: age, histologic subtype, FIGO 2018 stage, tumor size, tumor grade, lymph node metastasis (LNM), lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI), invasion, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

- The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS).

- Statistical Analysis and Model Development:

- Univariate Cox regression analysis was performed on the TC to identify significant predictors.

- Statistically significant factors from the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate Cox regression model to identify independent prognostic factors. The final model was selected based on the highest concordance index (C-index).

- A nomogram was constructed to visualize the model and predict 3-, 5-, and 10-year OS probabilities.

- Validation and Performance Assessment:

- Internal Validation: The nomogram was applied to the IVC.

- External Validation: The model was tested on an external validation cohort (EVC) of 318 patients from Yangming Hospital Affiliated to Ningbo University (2008-2020).

- Performance was assessed using the C-index, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, calibration charts, and decision curve analysis (DCA).

Protocol 2: Internal Validation of a High-Dimensional Prognostic Model

This protocol is derived from a simulation study focusing on internal validation strategies for transcriptomic-based prognosis models in head and neck tumors [4].

- Objective: To compare internal validation strategies for Cox penalized regression models in high-dimensional time-to-event settings and provide recommendations.

- Data Simulation:

- A simulation study was conducted using real data parameters from the SCANDARE head and neck cohort (n=76).

- Simulated datasets included clinical variables (age, sex, HPV status, TNM staging) and transcriptomic data (15,000 transcripts).

- Disease-free survival was simulated with a realistic cumulative baseline hazard.

- Sample sizes of N=50, 75, 100, 500, and 1000 were simulated, with 100 replicates for each sample size.

- Model Development:

- Cox penalized regression (e.g., Lasso, Ridge, Elastic Net) was performed for model selection on each simulated dataset.

- Internal Validation Strategies Compared:

- Train-Test Validation: 70% of data for training, 30% for testing.

- Bootstrap Validation: 100 bootstrap iterations.

- 0.632+ Bootstrap Validation: An enhanced bootstrap method to correct optimism.

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: 5-fold cross-validation.

- Nested Cross-Validation: 5x5 nested cross-validation.

- Performance Metrics:

- Discrimination: Assessed using the C-Index and time-dependent Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- Calibration: Assessed using the 3-year integrated Brier Score.

Visualization of Validation Workflows and Method Selection

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships and workflows for the validation strategies discussed.

Diagram 1: Clinical Model Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Internal Validation Method Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, datasets, and software tools essential for conducting robust validation in drug development, as referenced in the featured studies and broader context.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| SEER Database | A comprehensive cancer registry database providing incidence, survival, and treatment data for a significant portion of the US population. Used for developing and internally validating large-scale prognostic models. | Source of 13,592 cervical cancer patient records for model development and internal validation [13]. |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | A federally mandated registry of clinical trials. Serves as the primary source for analyzing the drug development pipeline, including trial phases, agents, and biomarkers. | Primary data source for profiling the 2025 Alzheimer's disease pipeline (182 trials, 138 drugs) [19]. |

| Institutional Patient Registries | Hospital or university-affiliated databases containing detailed clinical, pathological, and outcome data. Critical for external validation of models developed from larger public databases. | External validation cohort (N=318) from Yangming Hospital used to test the generalizability of the cervical cancer nomogram [13]. |

| R Software with Survival Packages | Open-source statistical computing environment. Essential for performing complex survival analyses, Cox regression, and generating nomograms and validation metrics. | Used for all statistical analyses, including univariate/multivariate Cox regression and nomogram construction [13]. |

| Cox Penalized Regression Algorithms | Statistical methods (e.g., Lasso, Ridge, Elastic Net) used for model selection and development in high-dimensional settings where the number of predictors (p) far exceeds the number of observations (n). | Used for model selection in the high-dimensional transcriptomic simulation study [4]. |

| Biomarker Assays | Analytical methods (e.g., immunoassays, genomic sequencing) to detect physiological or pathological states. Used for patient stratification and as outcomes in clinical trials. | Biomarkers were used as primary outcomes in 27% of active AD trials and for establishing patient eligibility [19]. |

Implementation Strategies: Rigorous Validation Techniques for Predictive Models

In the realm of statistical modeling and machine learning, the ultimate test of a model's value lies not in its performance on the data used to create it, but in its ability to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data. This principle is especially critical in fields like pharmaceutical research and drug development, where model predictions can influence significant clinical decisions. Internal validation provides a framework for estimating this future performance using only the data available at the time of model development, before committing to costly external validation studies or real-world deployment [20] [21].

Internal validation exists within a broader validation framework that includes external validation. While internal validation assesses how the model will perform on new data drawn from the same population, external validation tests the model on data collected by different researchers, in different settings, or from different populations [20] [21] [22]. A model must first demonstrate adequate performance in internal validation before the resource-intensive process of external validation is justified. Without proper internal validation, researchers risk deploying models that suffer from overfitting—a situation where a model learns the noise specific to the development dataset rather than the underlying signal, resulting in poor performance on new data [23].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the two predominant internal validation methodologies: bootstrapping and cross-validation. We will explore their theoretical foundations, detailed implementation protocols, comparative strengths and weaknesses, and practical applications specifically for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations: Bootstrapping vs. Cross-Validation

The Bootstrap Methodology

Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that estimates the sampling distribution of a statistic by repeatedly drawing new samples with replacement from the original dataset. In the context of internal validation, it is primarily used to estimate and correct for the optimism bias in apparent model performance (the performance measured on the same data used for training) [24] [22].

The fundamental principle behind bootstrap validation is that each bootstrap sample, created by sampling with replacement from the original dataset of size N, contains approximately 63.2% of the unique original observations, with the remaining 36.8% forming the out-of-bag (OOB) sample that can be used for validation [22]. By comparing the performance of a model fitted on the bootstrap sample when applied to that same sample (optimistic estimate) versus when applied to the original dataset or the OOB sample (pessimistic estimate), we can calculate an optimism statistic. This optimism is then subtracted from the apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected performance estimate [24] [25].

Several variations of the bootstrap exist for model validation, with the .632 and .632+ estimators being particularly important. The standard bootstrap .632 estimator combines the apparent performance and the out-of-bag performance using fixed weights (0.368 and 0.632 respectively), while the more sophisticated .632+ estimator uses adaptive weights based on the relative overfitting rate to provide a less biased estimate, particularly for models that perform little better than random guessing [22].

The Cross-Validation Methodology

Cross-validation (CV) provides an alternative approach to internal validation by systematically partitioning the available data into complementary subsets for training and validation. The most common implementation, k-fold cross-validation, divides the dataset into k roughly equal-sized folds or segments [26] [23].

In each of the k iterations, k-1 folds are used to train the model, while the remaining single fold is held back for validation. This process is repeated k times, with each fold serving exactly once as the validation set. The performance metrics from all k iterations are then averaged to produce a single estimate of model performance [26]. This approach ensures that every observation in the dataset is used for both training and validation, making efficient use of limited data.

Common variants of cross-validation include:

- Stratified K-Fold: Maintains the same class distribution in each fold as in the complete dataset, particularly important for imbalanced datasets [26].

- Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV): A special case where k equals the number of observations (N), providing nearly unbiased estimates but with high computational cost and variance, especially for large datasets [26].

- Repeated K-Fold: Performs multiple rounds of k-fold CV with different random splits of the data, providing more robust performance estimates at increased computational cost [25].

Methodological Protocols and Implementation

Bootstrap Validation Protocol

The bootstrap validation process follows a systematic protocol to obtain a bias-corrected estimate of model performance. The following workflow outlines the key steps in this procedure, with specific emphasis on the calculation of the optimism statistic.

Figure 1: Workflow diagram of the bootstrap validation process for estimating model optimism.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Model Development on Original Data: Begin by fitting the model to the entire original dataset (Dorig) and calculate the apparent performance (θapparent) by evaluating the model on this same data. This initial performance estimate is typically optimistically biased [24] [22].

Bootstrap Resampling: Generate B bootstrap samples (typically B = 200-400) by sampling N observations with replacement from the original dataset. Each bootstrap sample (D_boot) contains approximately 63.2% of the unique original observations, with some observations appearing multiple times [24] [22].

Bootstrap Model Training and Validation: For each bootstrap sample b = 1 to B:

- Fit the model to the bootstrap sample D_boot^b

- Calculate the bootstrap performance (θboot^b) by evaluating this model on Dboot^b itself

- Calculate the test performance (θtest^b) by evaluating the model on the original dataset Dorig

Optimism Calculation: Compute the optimism statistic for each bootstrap iteration: O^b = θboot^b - θtest^b. The average optimism across all B iterations is given by: Ō = (1/B) × ΣO^b [24].

Bias-Corrected Performance: Subtract the average optimism from the apparent performance to obtain the optimism-corrected performance estimate: θcorrected = θapparent - Ō [24].

For enhanced accuracy, particularly with models showing significant overfitting, the .632+ estimator can be implemented, which uses adaptive weighting between the apparent and out-of-bag performances based on the relative overfitting rate [22].

Essential Research Reagents: Computational Tools for Bootstrap Validation

Table 1: Essential computational tools and their functions for implementing bootstrap validation

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Comprehensive environment for statistical computing and graphics | boot package for bootstrap procedures [24] |

| rms Package (R) | Regression modeling strategies with built-in validation functions | validate() function for automated bootstrap validation [24] |

| Python Scikit-Learn | Machine learning library with resampling capabilities | Custom implementation using resample function |

| Stata | Statistical software for data science | bootstrap command for resampling and validation [25] |

Cross-Validation Protocol

The k-fold cross-validation method provides a structured approach to assessing model performance through systematic data partitioning. The following workflow illustrates the process for a single k-fold cross-validation cycle.

Figure 2: Workflow diagram of the k-fold cross-validation process for model performance estimation.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Data Partitioning: Randomly shuffle the dataset and partition it into k roughly equal-sized folds or segments. For stratified k-fold CV (recommended for classification problems), ensure that each fold maintains approximately the same class distribution as the complete dataset [26] [23].

Iterative Training and Validation: For each fold i = 1 to k:

- Designate fold i as the validation set, and the remaining k-1 folds as the training set

- Fit the model using the training set (k-1 folds)

- Evaluate the fitted model on the validation set (fold i)

- Record the performance metric (e.g., accuracy, AUC) for this iteration

Performance Aggregation: Calculate the final cross-validation performance estimate by averaging the performance metrics across all k iterations: θcv = (1/k) × Σθi [26] [23].

Optional Repetition: For increased reliability, particularly with smaller datasets, repeat the entire k-fold process multiple times (e.g., 10×10-fold CV or 100×10-fold CV) with different random partitions, and average the results across all repetitions [25].

Essential Research Reagents: Computational Tools for Cross-Validation

Table 2: Essential computational tools and their functions for implementing cross-validation

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Python Scikit-Learn | Machine learning library with comprehensive CV utilities | cross_val_score, KFold, StratifiedKFold [23] |

| R caret Package | Classification and regression training with CV support | trainControl function with CV method [26] |

| R Statistical Software | Base environment for statistical computing | Custom implementation with loop structures |

| Weka | Collection of machine learning algorithms | Built-in cross-validation evaluation option |

Comparative Analysis and Practical Applications

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

The choice between bootstrap and cross-validation methods depends on various factors including dataset characteristics, computational resources, and the specific modeling objectives. The following table provides a structured comparison to guide methodology selection.

Table 3: Comprehensive comparison of bootstrap and cross-validation methods for internal validation

| Characteristic | Bootstrap Validation | K-Fold Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Optimism correction, uncertainty estimation [24] [22] | Reduced bias, reliable performance estimation [26] [23] |

| Sample Size Suitability | Excellent for small samples (n < 200) [27] | Preferred for medium to large datasets [27] |

| Computational Efficiency | Moderate (200-400 iterations typically) [24] | Varies with k; generally efficient for k=5 or 10 [26] |

| Performance Estimate Bias | Can be biased with highly imbalanced data [27] | Lower bias with appropriate k [26] |

| Variance Properties | Lower variance, stable estimates [25] | Higher variance, especially with small k [26] |

| Data Utilization | Models built with ~63.2% of unique observations [22] | Models built with (k-1)/k of data in each iteration [23] |

| Key Advantage | Validates model built on full sample size N [25] | Efficient use of all data for training and testing [26] |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate (requires custom programming) [24] | Low (readily available in most ML libraries) [23] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

The selection of appropriate internal validation methods has particular significance in pharmaceutical research, where predictive models inform critical development decisions:

Clinical Prediction Models: Bootstrap methods are particularly valuable for validating clinical prediction models developed from limited patient cohorts, common in rare disease research or early-phase clinical trials [27]. The bootstrap's ability to provide confidence intervals for performance metrics alongside bias-corrected point estimates makes it invaluable for assessing model robustness with limited data.

Biomarker Discovery and Genomic Applications: In high-dimensional settings such as genomics and proteomics (e.g., GWAS, transcriptomic analyses), where the number of features (p) far exceeds the number of observations (N), repeated k-fold cross-validation is often preferred as it remains effective even when N < p [25]. The stratification capability of k-fold CV also helps maintain class balance in imbalanced biomarker validation studies.

Causal Inference and Treatment Effect Estimation: While both methods have applications in causal modeling, bootstrap is particularly widely used for quantifying variability in treatment effect estimates (e.g., bootstrapped confidence intervals for Average Treatment Effects) [27]. Cross-validation finds application in assessing the predictive accuracy of propensity score models or outcome regressions within causal frameworks.

Bayesian Models: For Bayesian approaches, which naturally quantify uncertainty through posterior distributions, leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) and its approximations (e.g., WAIC, PSIS-LOO) are commonly employed, while bootstrap validation is less frequently used as the posterior samples already account for parameter uncertainty [27].

Internal validation through bootstrapping and cross-validation represents a critical phase in the model development lifecycle, providing essential estimates of how well a model will perform on new data from the same population. While bootstrap methods excel in small-sample settings and provide robust optimism correction, cross-validation techniques offer efficient performance estimation with reduced bias for medium to large datasets.