Mastering Overfitting and Underfitting: A Model-Informed Drug Development Perspective

This article provides a comprehensive guide to overfitting and underfitting in machine learning, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Mastering Overfitting and Underfitting: A Model-Informed Drug Development Perspective

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to overfitting and underfitting in machine learning, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational concepts of bias-variance tradeoff, explores methodological applications in MIDD, details advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques for predictive models, and discusses robust validation frameworks. By aligning model complexity with specific Context of Use (COU), this resource aims to enhance the reliability and regulatory acceptance of AI/ML models in biomedical research, from early discovery to clinical decision support.

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff: Core Principles for Robust Model Generalization

Defining Overfitting and Underfitting in Machine Learning

Contents

- Introduction

- Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Framing

- A Quantitative Comparison

- Methodologies for Detection and Evaluation

- Experimental Protocols and Empirical Evidence

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

- Conclusion

In machine learning (ML), the ultimate goal is to develop models that generalize—they must perform reliably on new, unseen data after being trained on a finite dataset [1] [2]. The path to achieving this is fraught with two fundamental pitfalls: underfitting and overfitting. These concepts represent a critical trade-off between a model's simplicity and its complexity, directly impacting its predictive accuracy and utility in real-world applications, such as drug discovery and development [3]. For researchers and scientists, a deep understanding of these phenomena is not merely academic; it is essential for building robust, reliable, and interpretable models that can accelerate research and reduce failure rates in critical domains like healthcare. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of overfitting and underfitting, framed within contemporary ML research.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Framing

At its core, the challenge of model fitting is governed by the bias-variance trade-off, a fundamental concept that decomposes a model's generalization error into interpretable components [1] [4].

The Bias-Variance Decomposition

The expected prediction error on a new sample can be formally decomposed as follows: [ \text{Error} = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{Variance} + \text{Irreducible Error} ]

- Bias: The error introduced by approximating a real-world problem, which may be exceedingly complex, with a simplified model. High bias causes the model to miss relevant relationships between features and the target output, leading to underfitting [1] [4].

- Variance: The error introduced by the model's excessive sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set. A high-variance model learns not only the underlying signal but also the noise in the training data, leading to overfitting [4] [5].

- Irreducible Error: The inherent noise in the data that cannot be reduced by any model.

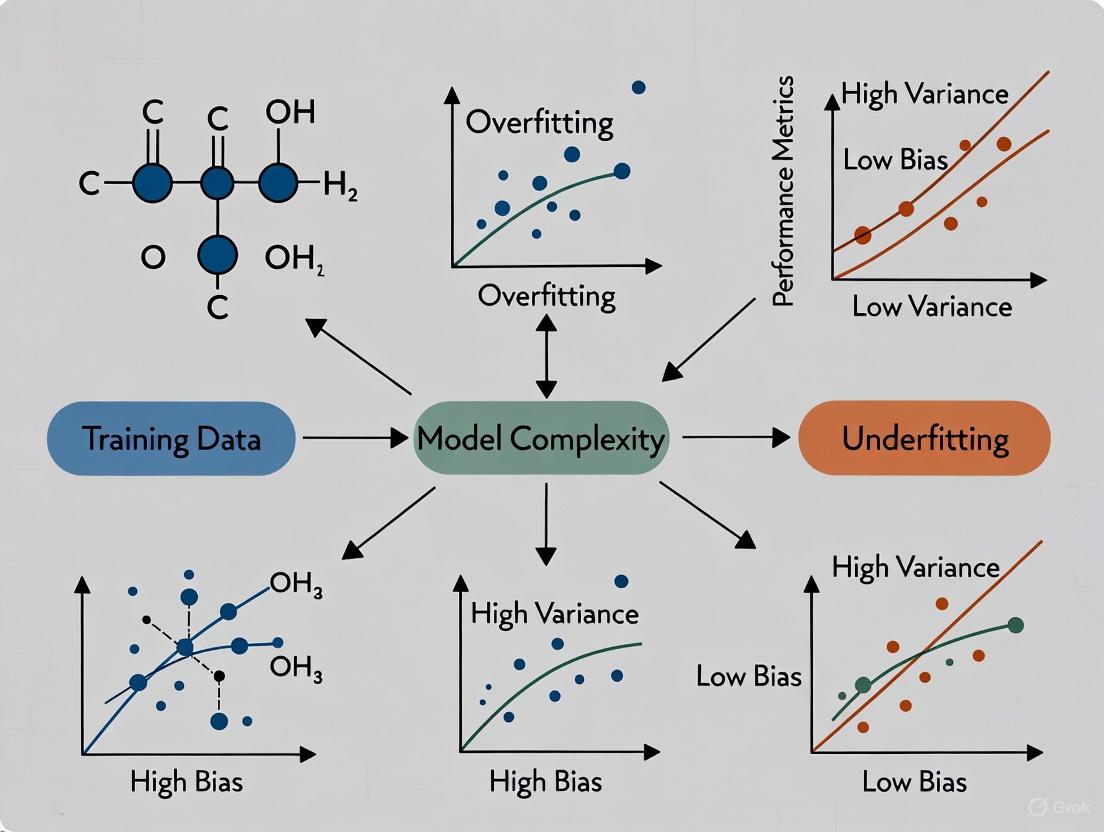

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between model complexity, error, the bias-variance tradeoff, and the resulting model behavior:

Formal Definitions in the Empirical Risk Framework

Within the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) framework, overfitting and underfitting can be precisely defined [5]. Let ( h ) represent a prediction model from a hypothesis class ( H ), and ( l ) be a loss function.

- Overfitting occurs when the empirical risk (training error) of model ( h ) is small relative to its true risk (test error). The model corresponds too closely to the training dataset and may fail to fit additional data reliably [2] [5].

- Underfitting occurs when a model cannot achieve a sufficiently small empirical risk, indicating that it has failed to capture the underlying structure of the training data [2].

A Quantitative Comparison

The distinct characteristics of underfit, overfit, and well-generalized models are summarized in the table below for clear comparison. This is critical for rapid diagnosis during model development.

Table 1: Diagnostic Characteristics of Model Fit States

| Feature | Underfitting | Overfitting | Good Fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance on Training Data | Poor [1] [4] | Excellent (often 95%+) [1] [6] | Good [1] |

| Performance on Test/Validation Data | Poor [1] [4] | Poor [1] [4] | Good [1] |

| Model Complexity | Too Simple [1] | Too Complex [1] | Balanced [1] |

| Bias | High [1] [4] | Low [1] | Low [1] |

| Variance | Low [1] [4] | High [1] | Low [1] |

| Primary Fix | Increase complexity/features [1] [4] | Add more data/regularize [1] [4] | Maintain current approach |

Methodologies for Detection and Evaluation

Robust detection of overfitting and underfitting requires systematic validation protocols beyond a simple train-test split.

Key Detection Methods

- Validation Set and Learning Curves: The most direct method is to monitor the model's performance on a held-out validation set during training. A signature of overfitting is a continuous decrease in training error while validation error begins to increase after a certain point. Underfitting is indicated when both training and validation error are high [1] [6].

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: This technique involves splitting the data into 'k' subsets. The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold, rotating the process for all folds. This provides a more reliable, robust estimate of model generalization performance and helps identify instability indicative of overfitting [1].

- Nested Cross-Validation: For complex workflows involving feature selection and hyperparameter tuning, a nested protocol is essential. Feature selection and model fitting must be performed on the training fold of an outer cross-validation loop, with error estimation performed strictly on the held-out test fold. This prevents "data leakage" and optimistic bias in error estimates, a critical concern in high-dimensional data like genomics [2].

The following workflow diagram outlines a robust experimental protocol that incorporates these validation methods to mitigate overfitting and underfitting:

Experimental Protocols and Empirical Evidence

Real-world case studies from recent literature highlight the practical implications and solutions for overfitting and underfitting.

Case Study 1: IoT Botnet Detection with a Multi-Model Framework

A 2025 study on IoT botnet detection provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing model fit [7].

- Experimental Protocol: The researchers systematically addressed data quality across three distinct datasets (BOT-IOT, CICIOT2023, IOT23). Their methodology included a Quantile Uniform transformation to reduce feature skewness, a multi-layered feature selection process, and a robust model fitting optimization framework using Random Forest and Logistic Regression with threshold-based decision-making [7].

- Findings on Model Fit: The study demonstrated significant performance variations across datasets. While BOT-IOT and CICIOT2023 allowed for high accuracy, IOT23 presented more complex, real-world challenges. The authors implemented cross-validation to reveal these dataset-specific fitting challenges, addressing class imbalance via SMOTE to prevent the model from underfitting to minority classes. Their final weighted soft-voting ensemble of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM), Random Forest, and Logistic Regression achieved superior performance (100% accuracy on BOT-IOT, 99.2% on CICIOT2023, 91.5% on IOT23) by leveraging the strengths of individual models and mitigating their individual tendencies to overfit or underfit [7].

Case Study 2: Lung Cancer Level Classification with Traditional ML

A comprehensive analysis on lung cancer staging compared traditional ML models with deep learning [8].

- Experimental Protocol: The research implemented a suite of models, including XGBoost (XGB), Logistic Regression (LR), and Random Forest (RF). A critical part of their methodology was the careful tuning of hyperparameters like learning rate and child weight to minimize the risk of overfitting [8].

- Findings on Model Fit: The study concluded that traditional ML models, particularly XGBoost and Logistic Regression, outperformed more complex deep learning models, achieving nearly 100% classification accuracy. The authors argued that the deep learning models underperformed due to the limited dataset size, making them prone to overfitting. This underscores that model complexity must be appropriate for the available data volume. The success of well-regularized traditional models highlights an effective strategy to avoid overfitting while maintaining low bias in contexts with constrained data [8].

Table 2: Experimental Findings on Model Fit from Case Studies

| Study | Domain | Key Methodology to Control Fit | Finding on Over/Underfitting |

|---|---|---|---|

| IoT Botnet Detection (2025) [7] | Cybersecurity | Quantile Uniform transformation, multi-layered feature selection, ensemble learning | Ensembles mitigated overfitting; complex datasets (IOT23) revealed harder generalization challenges. |

| Lung Cancer Classification [8] | Medical Diagnostics | Careful tuning of learning rate and child weight in XGBoost | Traditional ML (XGB, LR) outperformed deep learning, which was prone to overfitting on limited data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological "reagents" — techniques and tools — essential for designing experiments to diagnose and prevent fitting problems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Managing Model Fit

| Research Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [1] | Provides a robust estimate of generalization error by rotating data through k training and validation splits. | Generalization Error Estimation |

| L1 (Lasso) & L2 (Ridge) Regularization [1] [3] | Adds a penalty to the loss function to constrain model complexity. L1 can shrink coefficients to zero, performing feature selection. | Preventing Overfitting |

| Dropout [1] [3] | A regularization technique for neural networks where random neurons are ignored during training, preventing complex co-adaptations. | Preventing Overfitting in DNNs |

| Early Stopping [1] [4] | Halts the training process when performance on a validation set begins to degrade, preventing the model from over-optimizing on training data. | Preventing Overfitting during Training |

| SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) [7] | Generates synthetic samples for minority classes to address class imbalance, preventing the model from underfitting to those classes. | Mitigating Underfitting due to Imbalance |

| Quantile Uniform Transformation [7] | Reduces feature skewness while preserving critical information (e.g., attack signatures in security data), improving model stability. | Data Preprocessing for Better Fit |

Overfitting and underfitting are not merely abstract concepts but are practical challenges that dictate the success of machine learning models in scientific research and drug development. The bias-variance tradeoff provides the theoretical underpinning, while rigorous methodological practices—such as cross-validation, regularization, and careful feature engineering—form the first line of defense. As evidenced by contemporary research, the choice of model complexity must be carefully matched to the quality and quantity of available data. For high-stakes fields like healthcare, a disciplined approach to managing model fit is non-negotiable. It is the cornerstone of developing reliable, generalizable, and trustworthy AI systems that can truly accelerate discovery and innovation.

The Critical Role of Generalization in Predictive Modeling

In the realm of machine learning, the ultimate test of a predictive model's value lies not in its performance on training data, but in its ability to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data. This capability is known as generalization [9]. For researchers and professionals in fields like drug development, where models must reliably inform critical decisions, achieving robust generalization is paramount. It represents the bridge between theoretical model performance and real-world utility [10].

The pursuit of generalization is fundamentally governed by the need to balance two opposing challenges: overfitting and underfitting. These concepts are central to a model's performance and are best understood through the lens of the bias-variance tradeoff [4] [11]. A model that overfits has learned the training data too well, including its noise and irrelevant details; it exhibits low bias but high variance, leading to excellent training performance but poor performance on new data [4] [12]. Conversely, a model that underfits has failed to capture the underlying patterns in the data; it exhibits high bias but low variance, resulting in suboptimal performance on both training and test sets [4] [11]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, practical techniques, and experimental protocols for achieving generalization, with a particular focus on its critical importance in scientific research.

Theoretical Foundations: The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

The bias-variance tradeoff provides a fundamental framework for understanding generalization [4] [13].

- Bias is the error arising from overly simplistic assumptions in the learning algorithm. A high-bias model is inflexible and may fail to capture complex patterns, leading to underfitting [4] [11]. For example, using a linear model to represent a non-linear relationship will typically result in high bias [11].

- Variance is the error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set. A high-variance model is overly complex and learns the noise in the training data as if it were a true pattern, leading to overfitting [4] [11].

The goal in machine learning is to find an optimal balance where both bias and variance are minimized, resulting in a model that generalizes well [4]. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between model complexity, error, and the concepts of overfitting and underfitting.

Figure 1: The Bias-Variance Tradeoff. As model complexity increases, bias error decreases but variance error increases. The goal is to find the optimal complexity that minimizes total error, ensuring good generalization [4] [11] [13].

Techniques for Achieving Generalization

A suite of techniques has been developed to help models generalize effectively. The table below summarizes the primary methods used to combat overfitting and underfitting.

Table 1: Techniques to Improve Model Generalization

| Technique | Primary Target | Mechanism of Action | Common Algorithms/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regularization [9] [11] | Overfitting | Adds a penalty term to the loss function to discourage model complexity. | Lasso (L1), Ridge (L2), Elastic Net |

| Cross-Validation [9] [11] | Overfitting | Rotates data splits for training/validation to ensure performance is consistent across subsets. | k-Fold, Stratified k-Fold, Nested CV |

| Data Augmentation [9] [11] | Overfitting | Artificially expands the training set by creating modified versions of existing data. | Image rotation/flipping, noise injection |

| Ensemble Methods [9] [13] | Overfitting & Underfitting | Combines predictions from multiple models to reduce variance and improve robustness. | Random Forests, Bagging, Boosting |

| Dropout [4] [12] | Overfitting | Randomly "drops out" neurons during training to prevent co-adaptation. | Neural Networks |

| Increase Model Complexity [4] [11] | Underfitting | Uses a more powerful model capable of learning complex patterns. | Deep Neural Networks, Polynomial Features |

| Feature Engineering [4] [11] | Underfitting | Creates or selects more informative features to provide the model with better signals. | Interaction terms, domain-specific transforms |

The Generalization Workflow

Implementing these techniques effectively requires a structured workflow. The following diagram outlines a standard, iterative pipeline for building a generalized predictive model, incorporating key validation and tuning steps to mitigate overfitting and underfitting.

Figure 2: Iterative Workflow for Building Generalized Models. This pipeline emphasizes the cyclical nature of model development, where failure to generalize on the test set necessitates a return to earlier stages for improvement [9] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Generalization

Rigorous experimental design is non-negotiable for accurately assessing a model's ability to generalize. This is particularly critical in healthcare and drug development, where model failures can have significant consequences [10].

Case Study: Generalizing Clinical Text Models

A 2025 study published in Scientific Reports provides a robust template for evaluating generalization in a complex, real-world domain. The research aimed to classify anesthesiology Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from clinical free text across 44 U.S. institutions [10].

Table 2: Key Experimental Components from Clinical Text Generalization Study [10]

| Component | Description | Role in Generalization Research |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | 3-layer architecture (500, 250, 48 units) with ReLU/Softmax and 25% dropout. | Base predictive model to test generalization hypotheses. |

| Multi-Institution Data | 1,607,393 procedures from 44 institutions, covering 48 CPT codes. | Provides a real-world testbed for internal and external validation. |

| Text Preprocessing Levels | Three tiers: "Minimal," "cSpell" (automated), and "Maximal" (physician-reviewed). | Tests the impact of data cleaning on generalization. |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) | Statistical measure of divergence between probability distributions of datasets. | A heuristic to predict model performance on new institutional data. |

| k-Medoid Clustering | Clustering algorithm applied to composite KLD metrics. | Groups institutions by data similarity to understand generalization patterns. |

Experimental Methodology:

- Model Training Schemes: The researchers created and evaluated three types of models:

- Single-Institution Models: Trained on one institution's data and tested on all others.

- "All-Institution" Model: Trained on a combined 80% of data from all institutions and tested on the remaining 20%.

- "Holdout" Models: Trained on data from 43 institutions and tested on the one held-out institution [10].

- Performance Metrics: Accuracy and F1-score (micro-averaged) were used to compare predicted versus actual CPT codes [10].

- Generalizability Assessment: The core of the experiment involved pairwise evaluation, where a model trained on one set of institutions was evaluated on data from a completely different set of institutions [10].

Quantitative Findings:

Table 3: Summary of Quantitative Results from Clinical Text Study [10]

| Model Type | Internal Data Performance (Accuracy/F1) | External Data Performance (Accuracy/F1) | Generalization Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Institution | 92.5% / 0.923 | -22.4% / -0.223 | Large performance drop, indicating poor generalization. |

| All-Institution | -4.88% / -0.045 (vs. single) | +17.1% / +0.182 (vs. single) | Smaller gap; trades peak performance for better generalization. |

The study concluded that while single-institution models achieved peak performance on their local data, they generalized poorly. In contrast, models trained on aggregated data from multiple institutions were significantly more robust to distributional shifts, despite a slight drop in internal performance [10]. This highlights a key trade-off in generalization research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Solutions

For researchers aiming to reproduce or build upon generalization experiments, the following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Generalization Experiments

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function in Generalization Research |

|---|---|---|

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [9] [11] | Evaluation Framework | Provides a robust estimate of model performance by rotating training and validation splits, reducing the variance of the performance estimate. |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence (KLD) [10] | Statistical Metric | Quantifies the divergence between the probability distributions of two datasets (e.g., training vs. test, Institution A vs. Institution B), serving as a predictor of generalization performance. |

| Dropout [4] [12] | Regularization Technique | Prevents overfitting in neural networks by randomly disabling neurons during training, forcing the network to learn redundant representations. |

| L1 / L2 Regularization [4] [11] | Regularization Technique | Adds a penalty to the loss function (L1 for sparsity, L2 for small weights) to constrain model complexity and prevent overfitting. |

| Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) [10] | Feature Engineering | Converts unstructured text into a numerical representation, highlighting important words while downweighting common ones. Crucial for NLP generalization tasks. |

| Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [10] | Domain Knowledge Base | A set of files and software that brings together key biomedical terminologies. Used in Informed ML to incorporate domain knowledge and improve generalization. |

Generalization is the cornerstone of effective predictive modeling in research and industry. The challenge lies in navigating the bias-variance tradeoff to avoid the twin pitfalls of overfitting and underfitting. As demonstrated by both theoretical frameworks and rigorous clinical experiments, achieving generalization requires a principled approach that combines technical strategies—like regularization and cross-validation—with robust experimental design that tests models on truly external data. For drug development professionals and scientists, embracing these practices is not merely an academic exercise; it is a necessary discipline for building trustworthy AI systems that can deliver reliable insights and drive innovation in the real world.

In the pursuit of building effective machine learning models, researchers and practitioners aim to develop systems that perform well on their training data and, more importantly, generalize effectively to new, unseen data. The central challenge in this pursuit lies in navigating the tension between two fundamental sources of error: bias and variance. This tradeoff represents a core dilemma in statistical learning and forms the theoretical foundation for understanding the phenomena of overfitting and underfitting [14].

Framed within a broader thesis on model generalization, this decomposition provides a mathematical framework for diagnosing why models fail and offers principled approaches for improvement. For professionals in fields like drug development, where predictive model performance can have significant implications, understanding these concepts is essential for building reliable, robust systems that can accurately predict molecular activity, patient responses, or compound properties [15].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of bias-variance decomposition, its mathematical foundations, practical implications for model selection, and experimental methodologies for evaluating these error sources in research contexts.

Theoretical Foundation: Defining Bias and Variance

Core Concepts and Mathematical Definitions

In statistical learning, we typically assume an underlying functional relationship between input variables ( X ) and output variables ( Y ), expressed as ( Y = f(X) + \varepsilon ), where ( \varepsilon ) represents irreducible noise with mean zero and variance ( \sigma^2 ) [14]. Given a dataset ( D ) sampled from this distribution, we aim to learn an estimator or model ( \hat{f}(X; D) ) that approximates the true function ( f(X) ).

The bias of a learning algorithm refers to the error introduced by approximating a real-world problem, which may be complex, by a simplified model [16] [14]. Formally, for a given input ( x ), the bias is defined as the difference between the expected prediction of our model and the true value:

[ \text{Bias}(\hat{f}(x)) = \mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x)] - f(x) ]

High bias indicates that the model is missing relevant relationships between features and target outputs, a phenomenon known as underfitting [4].

Variance refers to the amount by which the model's predictions would change if it were estimated using a different training dataset [14]. It captures the model's sensitivity to specific patterns in the training data:

[ \text{Var}(\hat{f}(x)) = \mathbb{E}\left[(\mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x)] - \hat{f}(x))^2\right] ]

High variance indicates that the model has learned the noise in the training data rather than just the signal, a condition known as overfitting [4].

The Bias-Variance Decomposition

The bias-variance tradeoff finds its mathematical expression in the decomposition of the mean squared error (MSE). For a given model ( \hat{f} ) and test point ( x ), the expected MSE can be decomposed as follows [16] [14]:

[ \begin{align} \mathbb{E}[(y - \hat{f}(x))^2] &= \text{Bias}(\hat{f}(x))^2 + \text{Var}(\hat{f}(x)) + \sigma^2 \end{align} ]

Where ( \sigma^2 ) represents the irreducible error stemming from noise in the data generation process [16]. This decomposition reveals that to minimize total error, we must balance both bias and variance, as reducing one typically increases the other.

Table 1: Components of Mean Squared Error

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Bias² | ( (\mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x)] - f(x))^2 ) | Error from overly simplistic assumptions |

| Variance | ( \mathbb{E}[(\mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x)] - \hat{f}(x))^2] ) | Error from sensitivity to training data fluctuations |

| Irreducible Error | ( \sigma^2 ) | Noise inherent in the data generation process |

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff and Model Behavior

Relationship to Overfitting and Underfitting

The concepts of bias and variance provide a formal framework for understanding overfitting and underfitting [14]. When a model has high bias, it makes strong assumptions about the data and is too simple to capture underlying patterns, leading to underfitting [15] [4]. Such models typically exhibit poor performance on both training and test data. Linear regression applied to nonlinear data is a classic example of a high-bias model [15].

Conversely, when a model has high variance, it is excessively complex and sensitive to fluctuations in the training data, leading to overfitting [14] [4]. These models often perform well on training data but generalize poorly to unseen data. Decision trees with no pruning and high-degree polynomial regression are examples of high-variance models [15].

Table 2: Characteristics of Model Fit Conditions

| Condition | Bias | Variance | Training Performance | Test Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underfitting | High | Low | Poor | Poor |

| Proper Fitting | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Good |

| Overfitting | Low | High | Excellent | Poor |

Visualizing the Tradeoff

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between model complexity, error, the bias-variance tradeoff, their relationship to overfitting and underfitting:

As model complexity increases, bias decreases but variance increases [17]. The optimal model complexity is found at the point where the total error (the sum of bias², variance, and irreducible error) is minimized [14]. This point represents the best possible generalization performance for a given learning algorithm and dataset.

Quantitative Analysis Through Polynomial Regression

Experimental Framework

Polynomial regression provides an excellent experimental framework for demonstrating the bias-variance tradeoff [15]. By varying the degree of the polynomial, we can directly control model complexity and observe its effects on bias and variance.

Consider a scenario where the true underlying function is ( f(x) = \sin(2\pi x) ) but we observe noisy samples: ( y = f(x) + \varepsilon ), where ( \varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2) ). We fit polynomial regression models of varying degrees to different samples from this distribution.

Table 3: Model Performance Across Complexity Levels

| Model Type | Polynomial Degree | Bias² | Variance | Total MSE | Model Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Model | 1 | 0.2929 (High) | Low | 0.2929 | Underfitting |

| Polynomial Model | 4 | Moderate | Moderate | 0.0714 | Optimal Balance |

| Complex Polynomial | 25 | Low | 0.059 (High) | ~0.059 | Overfitting |

Experimental Protocol

To quantitatively evaluate bias and variance in practice, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol [18]:

Dataset Creation: Generate a synthetic dataset with known underlying function plus noise, or use a real dataset with sufficient samples.

Data Partitioning: Split the data into training and test sets, ensuring representative distributions.

Model Training: Train multiple models of varying complexity (e.g., polynomial degrees 1, 2, ..., 25) on the training data.

Bootstrap Sampling: Create multiple bootstrap samples from the original training data.

Model Evaluation:

- Train the same model architecture on each bootstrap sample

- Generate predictions on the test set from each model

- Calculate bias as the squared difference between the average prediction and true value

- Calculate variance as the average squared difference between individual predictions and the average prediction

Error Calculation: Compute total error as the sum of bias², variance, and optional noise term.

This methodology allows researchers to quantify the bias-variance profile of different algorithms and select the optimal complexity for their specific problem [18].

Managing the Tradeoff: Methods and Techniques

Regularization Approaches

Regularization techniques modify the learning algorithm to reduce variance at the expense of a small increase in bias, typically leading to better overall generalization [15] [17].

Ridge Regression (L2 Regularization) adds a penalty term proportional to the square of the coefficients to the loss function [15] [17]:

[ \text{Loss}{\text{Ridge}} = \sum{i=1}^{n}(yi - \hat{y}i)^2 + \lambda\sum{j=1}^{p}\betaj^2 ]

This discourages overly large coefficients, effectively reducing model variance [15].

Lasso Regression (L1 Regularization) adds a penalty term proportional to the absolute value of the coefficients [15] [17]:

[ \text{Loss}{\text{Lasso}} = \sum{i=1}^{n}(yi - \hat{y}i)^2 + \lambda\sum{j=1}^{p}|\betaj| ]

This can drive some coefficients to exactly zero, performing feature selection in addition to variance reduction [15].

Elastic Net Regression combines both L1 and L2 regularization penalties, offering a balance between feature selection and coefficient shrinkage [17].

Ensemble Methods

Ensemble methods combine multiple models to reduce variance without substantially increasing bias [15].

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) trains multiple instances of the same algorithm on different bootstrap samples of the training data and averages their predictions [15]. This approach is particularly effective for high-variance algorithms like decision trees [15].

Boosting builds models sequentially, with each new model focusing on the errors of the previous ones [15]. This can reduce both bias and variance but requires careful tuning to avoid overfitting.

Other Strategic Approaches

- Cross-Validation: Using k-fold cross-validation provides a more robust estimate of model performance and helps select optimal complexity [15].

- Early Stopping: In iterative algorithms, stopping training before convergence can prevent overfitting [4].

- Feature Selection: Reducing the number of features can decrease variance [4].

- Increasing Training Data: Adding more diverse training samples can help reduce variance without increasing bias [4].

For researchers implementing bias-variance analysis, the following tools and techniques are essential:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Bias-Variance Analysis

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bootstrap Sampling | Generates multiple training datasets with replacement | Estimating variance of learning algorithms |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Provides robust performance estimation | Model selection and hyperparameter tuning |

| Regularization (L1/L2) | Constrains model complexity | Variance reduction in high-dimensional problems |

| Ensemble Methods (Bagging/Boosting) | Combines multiple models | Variance reduction while maintaining low bias |

| Learning Curves | Plots training/validation error vs. sample size | Diagnosing high bias or high variance conditions |

| Polynomial Feature Expansion | Controls model complexity | Systematic study of bias-variance tradeoff |

Implications for Drug Development and Research

In drug development research, where datasets are often high-dimensional and sample sizes may be limited, understanding and managing the bias-variance tradeoff is particularly important [19]. For example:

Predictive Modeling: When building QSAR (Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship) models to predict compound activity, researchers must balance model complexity to ensure accurate predictions on novel chemical structures.

Biomarker Discovery: In high-dimensional omics data (genomics, proteomics), regularization techniques like LASSO can help identify the most relevant biomarkers while avoiding overfitting to noise in the data [19].

Clinical Trial Optimization: Predictive models for patient response must generalize beyond the trial population to be clinically useful, requiring careful bias-variance management.

The mean squared error framework provides a principled approach for model selection in these critical applications, ensuring that models are neither too simplistic to capture important biological relationships nor so complex that they capitalize on chance patterns in the training data [19].

The bias-variance decomposition provides a fundamental framework for understanding generalization in machine learning. By formally characterizing the sources of error that lead to overfitting and underfitting, this theoretical foundation informs practical strategies for model development and selection. For researchers in drug development and other scientific fields, applying these principles leads to more robust, reliable predictive models that can better withstand the test of real-world application. The ongoing challenge remains in finding the optimal balance specific to each dataset and problem domain, using the methodological toolkit outlined in this guide.

The translation of machine learning (ML) models from research to clinical practice represents a profound challenge, where the theoretical concepts of overfitting and underfitting manifest with direct consequences for patient care and medical decision-making. Overfitting occurs when a model learns patterns specific to the training data that do not generalize to the broader population, while underfitting results from overly simplistic models that fail to capture essential predictive relationships [2]. In healthcare applications, these are not merely statistical artifacts but fundamental determinants of whether a model will enhance clinical outcomes or potentially cause harm.

The high-dimensional nature of healthcare data, often characterized by many potential predictors relative to patient samples, creates an environment particularly susceptible to overfitting [2] [20]. Simultaneously, the heterogeneity of patient populations and variations in clinical practice across institutions threaten model generalizability. This technical review examines concrete case studies where these phenomena have directly impacted model performance, extracting lessons for researchers and clinicians working at the intersection of ML and healthcare.

Theoretical Framework: Overfitting and Underfitting in Clinical Context

Defining Generalization Error in Clinical Prediction Models

In clinical prediction modeling, performance must be understood through three distinct error measurements: training data error (error on the data used to derive the model), true generalization error (error on the underlying population distribution), and estimated generalization error (error estimated from sample data) [2]. The discrepancy between training error and true generalization error represents the overfitting component, which arises when models learn idiosyncrasies of the training sample that are not representative of the population.

The bias-variance tradeoff manifests uniquely in clinical settings. Underfitted models (high bias) may overlook clinically relevant predictors, while overfitted models (high variance) may identify spurious correlations that fail to generalize beyond the development cohort. The optimal balance depends on the clinical use case, with high-stakes decisions requiring more conservative approaches that prioritize reliability over maximal accuracy [2] [21].

Methodological Origins of Poor Generalization

Several methodological factors contribute to overfitting and underfitting in clinical prediction models. Imperfect study designs that do not adequately represent the target population can introduce sampling biases that become embedded in the model [2]. Error estimation procedures that do not properly separate training and testing phases, such as using the same data for feature selection and model evaluation, create overly optimistic performance estimates [2]. Additionally, model complexity that is not justified by the available sample size represents a common pathway to overfitting, particularly with powerful learners like deep neural networks [22].

Case Studies in Clinical Prediction Models

Ovarian Malignancy Classification: Overfitting with Competitive Generalization

A study on ovarian tumor classification demonstrated the complex relationship between overfitting and generalization in random forest models. Researchers developed prediction models to classify ovarian tumors into five categories using clinical and ultrasound data. The random forest model achieved a nearly perfect Polytomous Discrimination Index of 0.93 on training data, significantly higher than logistic regression models (PDI 0.47-0.70), suggesting substantial overfitting [23].

Unexpectedly, during external validation, the random forest model maintained competitive performance (PDI 0.54) compared to other methods (PDI 0.41-0.55), despite the extreme overfitting indicators in training [23]. Visualization of the probability estimates revealed that the random forest learned "spikes of probability" around events in the training set, where clusters of events created broader peaks (signal) while isolated events created local peaks (noise) [23]. This case illustrates that near-perfect training performance does not necessarily preclude clinical utility, challenging conventional assumptions about overfitting.

Dynamic Mortality Prediction in Critical Care

A study developing deep learning models for dynamic mortality prediction in critically ill children, termed the "Criticality Index," highlighted challenges in model complexity and implementability. The model achieved good discrimination (AUROC >0.8) but faced criticism for its extreme complexity, incorporating numerous variables and different neural networks for each 6-hour time window [21].

A significant limitation was the absence of benchmarking against more parsimonious and interpretable models, making it difficult to determine whether the complexity was justified [21]. This case exemplifies the tension between model complexity and practical implementation, where over-engineered solutions may achieve competitive performance metrics while sacrificing the simplicity required for clinical adoption and trust.

In-Hospital Mortality Prediction: Feature Selection Impact

Research on in-hospital mortality prediction using the eICU Collaborative Research Database provided insights into how feature selection affects model performance and interpretation. Researchers trained XGBoost models using 20,000 distinct feature sets, each containing ten features, to assess how different combinations influence performance [20].

Table 1: Performance Variation Across Feature Combinations in Mortality Prediction

| Metric | Average Performance | Best Performance | Key Influential Features | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUROC | 0.811 | 0.832 | Age, admission diagnosis, mean blood pressure | |

| AUPRC | Varied across sets | Highest with specific combinations | Different features than AUROC |

Despite variations in feature composition, models exhibited comparable performance across different feature sets, with age emerging as particularly influential [20]. This demonstrates that multiple feature combinations can achieve similar discrimination, suggesting that the common practice of identifying a single "optimal" feature set may be misguided. The study also revealed that feature importance rankings varied substantially across different combinations, challenging the reliability of interpretation methods when features are correlated [20].

Breast Cancer Metastasis Prediction: Hyperparameter Effects

An empirical study on feedforward neural networks for breast cancer metastasis prediction systematically evaluated how 11 hyperparameters influence overfitting and model performance [22]. Researchers conducted grid search experiments to quantify relationships between hyperparameter values and generalization gap.

Table 2: Hyperparameter Impact on Overfitting in Deep Learning Models

| Hyperparameter | Impact Direction on Overfitting | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | Negative correlation | High |

| Iteration-based Decay | Negative correlation | High |

| Batch Size | Negative correlation | High |

| L2 Regularization | Negative correlation | Medium |

| Momentum | Positive correlation | Medium |

| Epochs | Positive correlation | Medium |

| L1 Regularization | Positive correlation | Medium |

The findings revealed that learning rate, decay, and batch size had more significant impacts on overfitting than traditional regularization techniques like L1 and L2 [22]. This emphasizes the importance of comprehensive hyperparameter tuning beyond conventional regularization approaches. The study also identified interaction effects between hyperparameters, such as between learning rate and momentum, where large momentum values combined with high learning rates particularly degraded performance [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Evaluation of Feature Combinations

The in-hospital mortality study employed a rigorous protocol for evaluating feature combinations [20]:

Initial Feature Selection: 41 clinically relevant features were selected based on physiological importance and alignment with established scoring systems like APACHE IV.

Feature Reduction: The feature set was reduced to 20 using SHAP value importance rankings derived from cross-validated models.

Complementary Pair Generation: 10,000 complementary feature set pairs of size 10 were created through unordered sampling without replacement.

Model Training: XGBoost models were trained using an 80/20 train/test split with consistent partitioning across all experiments.

Performance Assessment: Models were evaluated using AUROC and AUPRC, with SHAP values used to interpret feature importance across different combinations.

This protocol enabled systematic assessment of how feature interactions affect model performance and interpretation, providing insights beyond what single-feature analysis can reveal.

Hyperparameter Grid Search Methodology

The breast cancer metastasis study implemented comprehensive grid search experiments [22]:

Hyperparameter Selection: 11 hyperparameters were selected for systematic evaluation: activation function, weight initializer, number of hidden layers, learning rate, momentum, decay, dropout rate, batch size, epochs, L1, and L2.

Value Ranges: Each hyperparameter was tested across a wide range of values to capture nonlinear relationships with model performance.

Model Training: Feedforward neural networks were trained using electronic health records data with consistent evaluation metrics.

Overfitting Quantification: The generalization gap was measured as the difference between training and test performance.

Interaction Analysis: Pairwise interactions between hyperparameters were evaluated to identify compounding effects.

This methodological approach enabled ranking of hyperparameters by their impact on overfitting and provided practical guidance for tuning clinical prediction models.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodological Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Clinical Prediction Modeling

| Component Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function in Mitigating Overfitting/Underfitting |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Electronic Health Records, Patient Registries, Wearable Devices | Provides representative real-world data covering diverse populations |

| Feature Selection | SHAP Value Analysis, Clinical Domain Knowledge, Univariate Screening | Balances model complexity with predictive information |

| Algorithms | XGBoost, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Neural Networks | Offers varying complexity-flexibility tradeoffs |

| Regularization Methods | L1 (Lasso), L2 (Ridge), Dropout, Early Stopping | Explicitly constrains model complexity to improve generalization |

| Interpretability Tools | SHAP, LIME, Partial Dependence Plots | Enables validation of clinical plausibility of learned patterns |

| Validation Frameworks | Nested Cross-Validation, External Validation, Temporal Validation | Provides unbiased performance estimation |

Discussion and Synthesis

Cross-Cutting Themes and Recommendations

Across the case studies, several consistent themes emerge regarding the real-world consequences of overfitting and underfitting in clinical prediction models. First, performance metrics alone are insufficient for evaluating model readiness for clinical implementation. The ovarian cancer study demonstrated that models showing extreme overfitting on training data can still generalize competitively, while the mortality prediction studies revealed that multiple feature combinations can achieve similar discrimination through different pathways [20] [23].

Second, model interpretability and complexity directly impact clinical utility. The tension between complex "black box" models and simpler interpretable approaches represents a fundamental challenge in clinical ML [21]. When multiple models achieve similar performance (the "Rashomon effect"), preference should be given to interpretable, parsimonious models that align with clinical understanding [21].

Third, implementation feasibility must be considered from the earliest development stages. Complex models requiring extensive feature engineering or specialized data elements face substantial barriers to real-world adoption, with one study estimating implementation costs exceeding $200,000 for even simple models [21].

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

Advancing clinical prediction models requires addressing several persistent challenges. Prospective validation remains uncommon, with only 13% of implemented models being updated following deployment [24]. Standardized evaluation frameworks that assess not just discrimination but also calibration, clinical utility, and implementation feasibility are needed [21] [24]. Furthermore, regulatory science must evolve to provide clearer pathways for model validation and monitoring in clinical practice.

The case studies collectively demonstrate that understanding and addressing overfitting and underfitting extends beyond statistical considerations to encompass clinical relevance, implementation practicality, and sustainable integration into healthcare workflows. By learning from these real-world examples, researchers can develop more robust, generalizable, and ultimately impactful clinical prediction models.

In machine learning, the Goldilocks Principle describes the critical goal of finding a model that is "just right"—neither too simple nor too complex [25] [26]. This principle directly addresses the core challenge of balancing overfitting and underfitting, two fundamental problems that determine a model's ability to generalize beyond its training data to new, unseen data [4] [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, achieving this balance is not merely theoretical; it directly impacts the reliability and translational potential of predictive models in critical applications such as drug discovery, patient stratification, and treatment efficacy prediction.

The essence of the problem lies in the bias-variance tradeoff [25] [4]. Bias refers to error from erroneous assumptions in the learning algorithm, typically resulting in oversimplification. Variance refers to error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set, resulting in over-complexity that captures noise as if it were signal [26] [11]. A model with high bias pays little attention to training data, leading to underfitting, while a model with high variance pays too much attention, leading to overfitting [4]. The idealized goal is to minimize both, creating a model that captures underlying patterns without memorizing dataset-specific noise [26].

Defining the Extremes: Overfitting and Underfitting

Conceptual Foundations and Symptoms

Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex and learns the training data too closely, including its noise and random fluctuations [25] [27]. Imagine a student who memorizes specific exam questions but fails to understand the underlying concepts; when question formats change, the student performs poorly [27]. An overfit model exhibits low bias but high variance [26] [11]. Key symptoms include:

- Excellent performance on training data (low training error) [11]

- Poor performance on validation and test data (high testing error) [4] [11]

- Overly complex decision boundaries that adapt to noise [11]

- Failure to generalize to new data from the same distribution [25]

In drug development, an overfit model might memorize specific experimental artifacts in training biomarker data rather than learning the true biological signatures of disease, failing when applied to new patient cohorts [11].

Underfitting occurs when a model is too simple to capture the underlying patterns in the data [25] [26]. This is akin to a student who only reads a textbook summary and misses crucial details needed to pass an exam [26]. An underfit model exhibits high bias but low variance [26] [11]. Key symptoms include:

- Poor performance on both training and testing data [4] [11]

- Consistently high errors across all datasets [11]

- Inability to capture relevant relationships between features and target variables [25]

- Systematic residual patterns indicating missed patterns [11]

In pharmaceutical research, underfitting might manifest as a linear model attempting to predict drug response based solely on dosage while ignoring crucial factors like genetic markers, metabolic pathways, and drug-drug interactions [11].

Visualizing the Tradeoff

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between model complexity, error, and the optimal "Goldilocks Zone" where a well-fit model achieves balance:

Figure 1: The relationship between model complexity, bias, variance, and total error, showing the target "Goldilocks Zone."

Quantitative Evaluation Framework

Core Classification Metrics

Evaluating model fit requires robust metrics that reveal different aspects of performance. For classification problems common in biomedical research (e.g., disease classification, treatment response prediction), multiple metrics provide complementary insights [28] [29].

Table 1: Key Evaluation Metrics for Classification Models

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) [28] [29] | Overall correctness | Balanced datasets, equal cost of errors [29] |

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP) [28] [29] | How reliable positive predictions are | When false positives are costly (e.g., drug safety) [29] |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP+FN) [28] [29] | Ability to find all positives | When false negatives are costly (e.g., disease screening) [29] |

| F1-Score | 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall) [28] [30] | Balance of precision and recall | Imbalanced datasets, single metric needed [29] |

| Specificity | TN/(TN+FP) [30] | Ability to identify negatives | When correctly identifying negatives is crucial |

| AUC-ROC | Area under ROC curve [28] [30] | Overall discrimination ability | Model selection across thresholds [28] |

Regression and Model Performance Metrics

For regression problems (e.g., predicting drug dosage efficacy, patient survival time), different metrics quantify prediction errors:

Table 2: Key Evaluation Metrics for Regression Models

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | (1/N)∑⎮yj-ŷj⎮ [28] | Average magnitude of errors | Less sensitive to outliers |

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | (1/N)∑(yj-ŷj)² [28] | Average squared errors | Highly sensitive to outliers |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | √MSE [28] | Standard deviation of errors | More interpretable, same units |

| R-squared (R²) | 1 - (∑(yj-ŷj)²/∑(y_j-ȳ)²) [28] | Proportion of variance explained | Goodness-of-fit measure |

Diagnostic Tools and Visualization

Beyond single-number metrics, diagnostic visualizations provide deeper insights into model behavior and fit:

- Learning Curves: Plot training and validation error against training set size or iteration. Overfit models show a large gap between curves; underfit models show convergence at high error [11].

- Confusion Matrix: A tabular display of actual vs. predicted classifications, enabling detailed error analysis [28] [30].

- ROC Curves: Plot true positive rate against false positive rate across classification thresholds, with AUC (Area Under Curve) quantifying overall performance [28] [30].

- Residual Plots: For regression, plot differences between predicted and actual values to identify patterns suggesting underfitting [11].

Methodologies for Achieving Optimal Fit

Experimental Protocols and Techniques

Achieving the Goldilocks zone requires systematic experimentation with model architecture, training strategies, and data preparation. The following workflow provides a structured methodology:

Figure 2: A systematic workflow for diagnosing and addressing model fit issues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Technical Solutions

Based on the diagnosis, researchers can select from a comprehensive toolkit of techniques to address specific fit issues:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Model Optimization

| Technique | Primary Use | Mechanism | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 & L2 Regularization [25] [11] | Combat overfitting | Adds penalty to loss function to constrain weights | L1 (Lasso) promotes sparsity; L2 (Ridge) shrinks weights evenly |

| Dropout [25] [4] | Neural network regularization | Randomly disables neurons during training | Prevents co-adaptation of features; effective in deep networks |

| Early Stopping [25] [4] | Prevent overfitting | Halts training when validation performance plateaus | Monitors validation loss; requires separate validation set |

| Cross-Validation [11] | Robust performance evaluation | Splits data into k folds for training/validation | Provides better generalization estimate; computational cost |

| Data Augmentation [25] [11] | Improve generalization | Artificially expands training data | Domain-specific transformations; preserves label integrity |

| Ensemble Methods [4] [11] | Improve predictive performance | Combines multiple models | Bagging reduces variance; boosting reduces bias |

| Feature Engineering [4] [11] | Address underfitting | Creates more informative features | Domain knowledge crucial; can include interactions, polynomials |

Advanced Protocol: Nested Cross-Validation for Robust Evaluation

For drug development applications where model reliability is critical, nested cross-validation provides a robust framework for both hyperparameter tuning and evaluation [11]:

- Outer Loop: Split data into k-folds for performance estimation

- Inner Loop: On each training fold, perform cross-validation to tune hyperparameters

- Validation: Train with optimal hyperparameters on outer training fold, test on outer test fold

- Iteration: Repeat across all outer folds, aggregate performance metrics

This approach prevents optimistic bias in performance estimates by keeping the test set completely separate from parameter tuning decisions [11].

Application in Drug Development and Pharmaceutical Research

Case Studies and Domain-Specific Considerations

The Goldilocks Principle finds critical application throughout drug development pipelines, where both over-optimistic and over-pessimistic models can have significant consequences:

Drug Dosage Optimization: Finding the therapeutic window between ineffective and toxic doses represents a literal Goldilocks problem. Models must balance underfitting that misses efficacy signals against overfitting that fails to generalize across patient populations [31] [11].

Biomarker Discovery: Predictive models for patient stratification must capture genuine biological signals without overfitting to batch effects or experimental noise. Underfit models miss clinically relevant biomarkers, while overfit models identify spurious correlations [11].

High-Throughput Screening: In virtual screening of compound libraries, models must generalize from limited training data to novel chemical spaces. Regularization and ensemble methods help maintain this balance [11].

Implementation Framework for Pharmaceutical Applications

Successful implementation requires domain-specific adaptations of the general methodologies:

Multi-Scale Validation: Validate models across biological replicates, experimental batches, and independent cohorts to ensure robustness.

Domain-Informed Regularization: Incorporate biological constraints (e.g., pathway information, chemical similarity) into regularization strategies.

Causality-Aware Modeling: Prioritize models that not only predict but provide mechanistic insights compatible with biological knowledge.

Regulatory-Compliant Evaluation: Maintain completely separate validation sets that simulate real-world deployment conditions, following FDA guidelines for algorithm validation.

The Goldilocks Principle provides both a philosophical framework and practical guidance for developing machine learning models that generalize effectively to new data. By systematically diagnosing and addressing overfitting and underfitting through appropriate evaluation metrics, regularization strategies, and validation protocols, researchers can create models that are "just right" for their intended applications. In drug development and pharmaceutical research, where predictive accuracy directly impacts patient outcomes and therapeutic discoveries, mastering this balance is not merely technical excellence but an ethical imperative. The methodologies and frameworks presented here provide a roadmap for achieving models that are sufficiently complex to capture meaningful patterns while remaining sufficiently simple to generalize beyond their training data.

Fit-for-Purpose Modeling: Techniques and Applications in Drug Development

Aligning Model Complexity with Context of Use (COU) in MIDD

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is an essential framework that uses quantitative methods to accelerate hypothesis testing, improve efficiency in assessing drug candidates, reduce costly late-stage failures, and support regulatory decision-making [32]. A core principle in MIDD is the "fit-for-purpose" (FFP) approach, which strategically aligns model development and complexity with a specific Context of Use (COU) and key Question of Interest (QOI) [32]. This alignment is critical; an overly complex model may become a "black box," difficult to validate and interpret, while an overly simplistic one may fail to capture essential biology or pharmacology, leading to poor predictive performance and misguided decisions [32] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between model complexity and the specific Context of Use within the MIDD paradigm.

Figure 1: The Alignment of Model Complexity with Drug Development Stage and Context of Use. The appropriate level of model complexity is determined by the specific stage of drug development and its corresponding Context of Use (COU), ranging from simpler models in early discovery to highly complex models for clinical development.

The "Fit-for-Purpose" Framework: Core Principles

Defining Context of Use (COU) and Question of Interest (QOI)

The Context of Use (COU) is a formal definition that describes the specific role and scope of a model—how its predictions will inform a particular decision in drug development or regulatory evaluation [32]. The COU is intrinsically linked to the Question of Interest (QOI), the precise scientific or clinical question the model is built to answer [32]. A well-defined COU specifies the model's purpose, the decisions it supports, and the applicable boundaries, ensuring the modeling effort is targeted and impactful.

A model is considered not FFP if it fails to define the COU, suffers from poor data quality, or lacks proper verification and validation. Oversimplification, insufficient data, or unjustified complexity can also render a model unfit for its intended purpose [32].

The Spectrum of Model Complexity in MIDD

MIDD employs a wide array of quantitative tools, each with its own level of complexity and appropriate application. The following table summarizes the key MIDD methodologies and their primary characteristics.

Table 1: Key Methodologies in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)

| Methodology | Description | Primary Applications in Drug Development | Typical Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) [32] | Computational modeling predicting biological activity from chemical structure. | Early target identification, lead compound optimization. | Low |

| Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA) [32] | Model-independent estimation of PK parameters (exposure, clearance). | Initial PK analysis from rich plasma concentration-time data. | Low |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) [32] | Mechanistic modeling simulating drug disposition based on physiology and drug properties. | Predicting drug-drug interactions, formulation impact, First-in-Human (FIH) dose prediction. | Medium |

| Population PK (PPK) & Exposure-Response (ER) [32] | Models explaining variability in drug exposure and linking exposure to efficacy/safety outcomes. | Optimizing dosing regimens, informing clinical trial design, supporting label claims. | Medium |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) [32] | Integrative, mechanistic modeling of drug effects within biological system networks. | Predictive safety evaluation, target validation, identifying critical biomarkers. | High |

| AI/ML Approaches [33] [3] | Data-driven models learning complex patterns from large datasets (e.g., bioactivity prediction, molecular design). | Drug target associations, biomarker discovery, de novo molecular design, predictive ADMET. | High |

Aligning Model Complexity with Drug Development Stages

Early Discovery and Preclinical Development

In early stages, the COU often involves rapid screening and prioritization. Models are used to filter thousands of potential candidates, requiring interpretability and speed over high predictive precision for human outcomes [32] [33].

- Typical QOIs: "Which chemical series shows the most promise for potency?" or "What is the predicted human PK profile?"

- FFP Models: QSAR models are ideal for predicting structure-activity relationships [32]. Machine Learning models trained on public and proprietary data can predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties, significantly accelerating lead optimization [33] [3].

- Complexity Consideration: While some ML models can be complex, their use here is FFP because they are applied to high-volume, early-stage prioritization where the cost of error is lower. The focus is on low bias to avoid missing promising compounds (underfitting), accepting that some false positives may occur [1].

Clinical Development and Regulatory Submissions

During clinical development, the COU shifts to informing study designs and dosing strategies, with a greater need for models that can extrapolate to human populations and support regulatory decisions [32] [34].

- Typical QOIs: "What is the recommended Phase 2 dose?" or "How will renal impairment affect drug exposure?"

- FFP Models: PBPK models are FFP for predicting drug-drug interactions and FIH doses [32]. Population PK/ER models are central to understanding sources of variability in drug response and justifying dosing recommendations [32].

- Complexity Consideration: These medium-complexity models are justified because they incorporate known physiology and population variability. The FDA's MIDD Paired Meeting Program highlights regulatory acceptance of these approaches for dose selection and trial simulation [34]. The primary risk is overfitting the model to sparse early clinical data, which can be mitigated by using prior knowledge and external validation [32] [1].

Confirmatory Trials and Post-Market Surveillance

For late-stage and post-market decisions, the COU often involves generating evidence to support specific label claims or optimizing use in real-world populations. The consequence of an incorrect model prediction is high, requiring robust validation [32].

- Typical QOIs: "Can we justify a new patient population in the label?" or "What is the potential effectiveness of a new combination therapy?"

- FFP Models: QSP models, which are highly complex and mechanistic, can be FFP for exploring combination therapies or long-term outcomes where clinical trials are unethical or impractical [32]. Model-based meta-analyses (MBMA) integrate data across multiple trials to provide context for a new drug's performance.

- Complexity Consideration: The high complexity of QSP is warranted by the complex QOI. The key is to manage the risk of overfitting by ensuring the model is grounded in established biology and calibrated against multiple data sources [32].

A Practical Framework for Risk Assessment and Model Selection

Selecting a FFP model requires a structured assessment of the decision at hand. The following workflow provides a methodological approach for researchers to align model complexity with COU while mitigating risks of overfitting and underfitting.

Figure 2: A Risk-Based Workflow for "Fit-for-Purpose" Model Selection. This decision process guides the selection of appropriate model complexity by evaluating the consequence of an incorrect prediction and the model's intended influence on the final decision.

The FDA emphasizes that the model risk assessment should consider both the weight of model predictions in the totality of data (model influence) and the potential risk of making an incorrect decision (decision consequence) [32] [34]. The following table outlines a framework for this assessment.

Table 2: Risk Assessment Framework for MIDD Model Selection and Validation

| Decision Consequence | Model Influence | Recommended FFP Model Complexity & Key Actions | Primary ML Pitfall to Mitigate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., internal compound prioritization) | Supporting (one of several evidence sources) | Lower Complexity. Use well-established, interpretable models (e.g., QSAR, linear regression). Limited validation may be sufficient. | Underfitting (high bias). Ensure the model is sufficiently complex to capture the real signal in the data. [1] |

| Medium (e.g., informing Phase 2 dose) | Informative (guides design but not sole evidence) | Medium Complexity. Use models with mechanistic basis (e.g., PBPK, PopPK). Requires internal and potentially external validation. | Overfitting (high variance). Use techniques like cross-validation and regularization to ensure generalization. [1] [3] |

| High (e.g., primary evidence for a regulatory decision) | Substantial/Decisive (critical evidence for a key claim) | Higher Complexity. Use of QSP or complex ML is permissible but requires extensive validation, documentation, and external verification. A comprehensive analysis of uncertainty is mandatory. [32] [34] | Overfitting and lack of interpretability. Employ sensitivity analysis, uncertainty quantification, and methods like SHAP to explain predictions. [1] [35] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Ensuring a model is FFP requires rigorous experimental protocols for validation. These methodologies are critical for diagnosing and preventing both overfitting and underfitting.

Protocol for Diagnosing and Mitigating Overfitting

Objective: To assess whether a model has learned the training data too well, including its noise, and fails to generalize to new data. This is a common risk with complex models like deep neural networks and QSP models with many unidentifiable parameters [1] [3].

Methodology:

- Data Splitting: Partition the available dataset into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20-30%). The test set must not be used for any aspect of model training or parameter tuning [3].

- Resampling and Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=5 or 10) on the training set. This involves splitting the training data into k folds, training the model on k-1 folds, and validating on the remaining fold, repeating the process k times. This provides a robust estimate of model performance on unseen data and helps tune hyperparameters without leaking information from the test set [1].

- Apply Regularization Techniques: Introduce penalties for model complexity during training.

- L1 Regularization (Lasso): Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of coefficient magnitudes, which can shrink less important coefficients to zero, performing feature selection. [1] [3]

- L2 Regularization (Ridge): Adds a penalty equal to the square of coefficient magnitudes, forcing weights to be small but rarely zero. [1] [3]

- Dropout (for Neural Networks): Randomly ignores a percentage of neurons during training, preventing complex co-adaptations and forcing the network to learn more robust features. [3]

- Performance Comparison: Calculate key performance metrics (e.g., R², RMSE for regression; AUC, accuracy for classification) on both the training and test sets. A significant performance drop on the test set is a hallmark of overfitting [1].

- Early Stopping: For iterative models like neural networks, monitor performance on a validation set during training. Halt training when validation performance begins to degrade, even if training performance continues to improve [1].

Protocol for Diagnosing and Mitigating Underfitting

Objective: To determine if a model is too simple to capture the underlying structure of the data, resulting in poor performance on both training and test data. This is a risk with overly simplistic models applied to complex problems [1].

Methodology:

- Baseline Performance Analysis: Train a simple model (e.g., linear model) and evaluate its performance on the training data. If performance is unacceptably poor, it is a strong indicator of underfitting [1].

- Model Complexity Increase: Iteratively increase model complexity.

- Reduce Regularization: If regularization was applied, reduce the regularization hyperparameter to allow the model greater flexibility to fit the data [1].

- Error Analysis: Analyze the residuals (difference between predictions and actual values). If residuals show a non-random pattern (e.g., a curve), it suggests the model is missing a key relationship in the data [1].

- Feature Importance Check: Use techniques like permutation importance or tree-based feature importance scores to ensure key predictive features are being utilized effectively by the model [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for implementing FFP modeling in MIDD.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MIDD

| Tool / Resource | Function in FFP Modeling | Relevance to Over/Underfitting |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn [3] | A comprehensive Python library providing simple and efficient tools for data mining and analysis. Includes implementations of many classic ML algorithms, preprocessing tools, and model validation techniques like cross-validation. | Essential for implementing standardized validation workflows to detect overfitting and for comparing multiple model complexities to avoid underfitting. |

| TensorFlow & PyTorch [3] | Open-source libraries for numerical computation and large-scale machine learning, specializing in defining, training, and running deep neural networks. | Provides built-in functions for dropout and other regularization techniques to mitigate overfitting in complex models. Allows for flexible model architecture design to combat underfitting. |

| ColorBrewer & Accessibility Tools [36] [37] | Scientifically developed color schemes for maps and visualizations that are perceptually uniform and colorblind-safe. | Critical for creating honest and accessible visualizations of model diagnostics (e.g., residual plots, validation curves) to prevent misinterpretation of model performance. |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation [1] [3] | A resampling procedure used to evaluate models by partitioning the data into k subsets, training on k-1 subsets, and validating on the remaining one. | A core technique for obtaining a reliable estimate of model generalization error, which is the primary metric for diagnosing overfitting. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [35] | A game theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model. It quantifies the contribution of each feature to a single prediction. | Enhances interpretability of complex models, helping to build trust and identify if the model is relying on spurious correlations (a sign of overfitting) or meaningful features. |

| Model-Informed Drug Development Paired Meeting Program [34] | An FDA initiative that allows sponsors to meet with Agency staff to discuss MIDD approaches in a specific drug development program. | Provides a formal pathway for aligning the planned model's complexity and COU with regulatory expectations early in development, de-risking the overall strategy. |

Success in MIDD hinges on the disciplined application of the "fit-for-purpose" principle. There is no universal "best" model—only the model that is optimally aligned with the Context of Use, adequately addresses the Question of Interest, and is rigorously validated for its intended task. By systematically assessing decision consequence and model influence, leveraging appropriate experimental protocols for validation, and utilizing the modern toolkit of software and regulatory pathways, drug developers can strategically navigate the trade-offs between underfitting and overfitting. This disciplined approach maximizes the potential of MIDD to streamline development, reduce attrition, and ultimately deliver safe and effective therapies to patients more efficiently.

The pursuit of robust, predictive models is a central challenge in modern drug development. Researchers employ a spectrum of sophisticated methodologies, including Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP), Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, and Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML). Each approach offers a distinct strategy for understanding the complex interplay between drugs and biological systems. A critical consideration that transcends all these methodologies is the machine learning concept of the bias-variance tradeoff, manifesting as underfitting (high bias) or overfitting (high variance). A model that underfits is too simplistic to capture the underlying biological or chemical patterns, leading to poor predictive performance on all data. In contrast, a model that overfits has memorized the noise and specificities of its training data, failing to generalize to new, unseen datasets or real-world scenarios. This guide explores these core modeling frameworks, their interrelationships, and the practical strategies researchers use to navigate the critical path between underfitting and overfitting to build reliable, translatable models.

Core Modeling Methodologies