Multireference Perturbation Methods for Bond Breaking: From Theory to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multireference perturbation theory (MRPT) methods for accurately modeling chemical bond breaking, a fundamental process in chemical reactions and drug mechanisms.

Multireference Perturbation Methods for Bond Breaking: From Theory to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multireference perturbation theory (MRPT) methods for accurately modeling chemical bond breaking, a fundamental process in chemical reactions and drug mechanisms. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles that explain why single-reference methods fail for bond dissociation, details key methodologies like CASPT2 and NEVPT2, and offers practical guidance for overcoming computational challenges such as intruder states and active space selection. The content further validates these methods through benchmark studies against full configuration interaction and discusses emerging applications, including the use of analytical gradients for reaction path analysis and the conceptual parallel of 'perturbation signatures' in drug discovery, providing a crucial link to quantitative systems pharmacology.

Why Single-Reference Methods Fail: The Essential Guide to Multireference Systems and Bond Breaking

The Quantum Mechanical Challenge of Bond Dissociation

The accurate quantum mechanical description of bond dissociation represents a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry, with critical implications for drug development, catalysis, and materials science. When chemical bonds break, the electronic structure undergoes a profound transformation that conventional single-reference quantum chemistry methods fail to capture. These methods, including standard density functional theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock, assume a dominant electronic configuration described by a single Slater determinant. This assumption becomes increasingly invalid as bonds stretch toward dissociation, where multiple electronic configurations become near-degenerate in energy—a phenomenon known as strong electron correlation [1].

This breakdown manifests quantitatively as unphysical energy profiles and catastrophic failures in predicting dissociation limits. For example, the hydrogen molecule (H₂) at equilibrium bond length is well-described by a single determinant, but at dissociation, it requires an equal superposition of two configurations: H⁻H⁺ and H⁺H⁻. Single-reference methods cannot describe this multiconfigurational character, leading to dramatically incorrect dissociation energies and reaction barriers that undermine predictive drug design and materials discovery [1]. The core challenge lies in the exponential scaling of truly accurate multireference methods with system size, which prohibits their application to biologically relevant molecules and extended materials encountered in pharmaceutical development.

Multireference Methods: Theoretical Framework

Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF)

The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) method provides the foundational approach for treating strong electron correlation in bond dissociation. CASSCF selects a set of active orbitals containing a distribution of active electrons, forming a Complete Active Space (CAS) where a full configuration interaction (FCI) calculation is performed. This active space is described by the notation CAS(e,m), where 'e' represents the number of active electrons and 'm' the number of active orbitals. The method optimizes both the CI coefficients and molecular orbitals self-consistently, providing a balanced treatment of static correlation essential for bond breaking [1].

For a typical carbon-carbon single bond dissociation (C-C), a minimal active space might include the bonding and antibonding orbitals involved in the bond breakage, typically requiring a CAS(2,2) calculation. However, larger active spaces are often necessary for quantitative accuracy, incorporating additional correlation effects. The primary limitation of CASSCF is its exponential scaling with active space size, becoming computationally prohibitive for active spaces beyond approximately 18 electrons in 18 orbitals—the so-called "CAS(18,18) barrier" that prevents application to many biologically relevant systems [1].

Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) and Quantum Embedding

Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) addresses the scaling limitations of pure multireference methods by partitioning the system into fragments embedded in a mean-field environment. The DMET algorithm begins with a converged Hartree-Fock wave function of the full system, followed by orbital localization onto atomic centers. The system is then partitioned into fragments, and through a Schmidt decomposition, each fragment is embedded in a bath of environmental orbitals that entangle with it. An impurity Hamiltonian is constructed for each fragment-plus-bath cluster, which is solved using a high-level multireference solver such as CASSCF [1].

The self-consistency in DMET is achieved through a correlation potential that modifies the mean-field Hamiltonian to minimize the difference between the embedded and global density matrices. For bond dissociation problems, this approach allows the application of high-level multireference treatment specifically to the dissociating bond while treating the remainder of the system at a lower level of theory. This fragmentation dramatically reduces computational cost while maintaining accuracy where it matters most—at the breaking bond [1].

Quantitative Data on Bond Dissociation

Accurate quantitative data on bond energies and lengths provides essential benchmarks for validating multireference methods in bond dissociation studies. The following tables summarize key experimental values for common chemical bonds relevant to pharmaceutical and materials research.

Table 1: Bond Dissociation Energies and Lengths for Hydrogen-Containing Bonds

| Bond | Dissociation Energy (kJ/mol) | Bond Length (pm) |

|---|---|---|

| H-H | 432 | 74 |

| H-C | 411 | 109 |

| H-N | 386 | 101 |

| H-O | 459 | 96 |

| H-F | 565 | 92 |

| H-Cl | 428 | 127 |

| H-Br | 362 | 141 |

| H-I | 295 | 161 |

Table 2: Carbon-Containing Bond Dissociation Energies and Lengths

| Bond | Dissociation Energy (kJ/mol) | Bond Length (pm) |

|---|---|---|

| C-C | 346 | 154 |

| C=C | 602 | 134 |

| C≡C | 835 | 120 |

| C-N | 305 | 147 |

| C=N | 615 | 129 |

| C≡N | 887 | 116 |

| C-O | 358 | 143 |

| C=O | 799 | 120 |

| C≡O | 1072 | 113 |

| C-F | 485 | 135 |

| C-Cl | 327 | 177 |

| C-Br | 285 | 194 |

| C-I | 213 | 214 |

Table 3: Other Notable Bond Dissociation Energies and Lengths

| Bond | Dissociation Energy (kJ/mol) | Bond Length (pm) |

|---|---|---|

| N-N | 167 | 145 |

| N=N | 418 | 125 |

| N≡N | 942 | 110 |

| O-O | 142 | 148 |

| O=O | 494 | 121 |

| F-F | 155 | 142 |

| Cl-Cl | 240 | 199 |

| Br-Br | 190 | 228 |

| I-I | 148 | 267 |

These quantitative values, particularly for bonds like C-C, C-N, and C-O that are ubiquitous in pharmaceutical compounds, provide critical reference data for assessing the accuracy of multireference methods in predicting bond dissociation curves and energies [2].

Computational Protocols for Bond Dissociation Studies

Protocol for Multireference Calculation of Bond Dissociation Curves

The accurate computation of bond dissociation curves requires careful attention to active space selection, basis set requirements, and method compatibility. The following protocol provides a standardized approach:

System Preparation:

- Geometry optimization at the equilibrium structure using a standard DFT method

- Sequential bond elongation in fixed increments (typically 0.05-0.1 Å) while relaxing other coordinates

- Use of correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ) with diffuse functions for accurate dissociation limits

Active Space Selection:

- For single bond dissociation: Include bonding (σ) and antibonding (σ*) orbitals plus relevant lone pairs (CAS(2,2) minimum)

- For multiple bonds: Include all π and π* orbitals in addition to σ/σ* pairs

- For transition metal complexes: Include metal d-orbitals and relevant ligand donor/acceptor orbitals

Multireference Calculation:

- CASSCF calculation for static correlation treatment at each geometry point

- Multireference perturbation theory (CASPT2 or NEVPT2) for dynamic correlation recovery

- Density matrix embedding theory (DMET) for large systems, applying high-level treatment only to the dissociating bond

Analysis:

DMET Implementation for Molecular Fragmentation

For large biomolecular systems or extended materials, the DMET protocol enables application of multireference methods to bond dissociation:

Mean-Field Calculation:

- Perform Hartree-Fock calculation on full system

- Localize orbitals using Pipek-Mezey or Foster-Boys localization

System Partitioning:

- Partition system into fragments based on chemical intuition (e.g., dissociating bond plus adjacent groups)

- Construct bath orbitals for each fragment through Schmidt decomposition

Embedded Calculation:

- Construct impurity Hamiltonian for each fragment plus bath

- Solve embedded system using CASSCF with appropriate active space

- Iterate to self-consistency through correlation potential optimization [1]

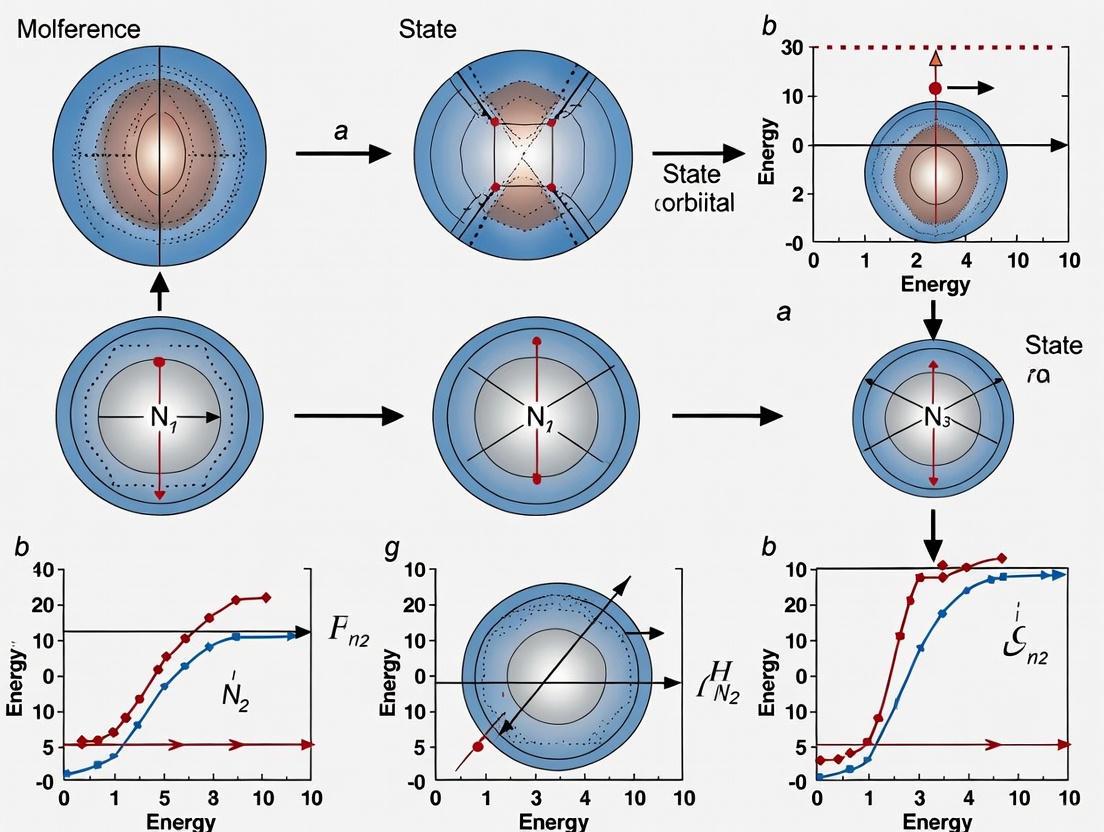

Visualization of Computational Workflows

Multireference Bond Dissociation Workflow

DMET Embedding Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Bond Dissociation Studies

| Tool/Software | Function | Application in Bond Dissociation |

|---|---|---|

| CASSCF Solver (e.g., Molpro, OpenMolcas, PySCF) | Multireference wavefunction calculation | Treatment of static correlation at stretched bond geometries |

| DMET Implementation (e.g., PySCF, ChemPS2) | Quantum embedding framework | Application of high-level methods to large systems via fragmentation |

| Multireference Perturbation Theory (CASPT2, NEVPT2) | Dynamic correlation recovery | Quantitative accuracy beyond CASSCF for dissociation energies |

| Orbital Localization (Pipek-Mezey, Foster-Boys) | Localized orbital construction | Essential preprocessing step for DMET fragmentation |

| Active Space Selector (e.g., AVAS, DMRG-CAS) | Automated active space selection | Systematic approach for complex systems with many correlated orbitals |

| VQE Quantum Algorithm | Quantum computer eigensolver | Future potential for exponential speedup in large active space calculations |

These computational tools represent the essential toolkit for researchers investigating bond dissociation phenomena. The integration of classical multireference methods with emerging quantum algorithms through embedding theories represents a particularly promising direction for addressing currently intractable systems in pharmaceutical research and materials design [1].

The quantum mechanical challenge of bond dissociation underscores the fundamental limitations of single-reference quantum chemistry methods and highlights the necessity of multireference approaches for predictive computational chemistry. Multireference perturbation methods, particularly when enhanced with embedding frameworks like DMET, provide a path forward for accurate bond dissociation studies in biologically relevant systems. The quantitative data, computational protocols, and visualization workflows presented here offer researchers a foundation for implementing these advanced methods in drug development and materials discovery.

Looking forward, the integration of quantum embedding theories with quantum computing algorithms presents a transformative opportunity. Variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) and other quantum algorithms could potentially overcome the exponential scaling of classical multireference methods, enabling accurate bond dissociation studies in large pharmaceutical compounds and complex materials that are currently beyond reach. As these technologies mature, the combination of multireference perturbation methods with quantum computational approaches will likely become an indispensable tool for understanding and predicting chemical reactivity across the molecular sciences [1].

A fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry is the accurate description of electron correlation—the effect whereby the motion of one electron is influenced by the repulsive presence of all others [4]. Within the Hartree-Fock (HF) approximation, this intricate interplay is only partially captured, primarily through the exchange interaction that prevents electrons with parallel spins from occupying the same region of space (Pauli correlation) [4]. The remaining Coulomb correlation, which describes the correlation between electron spatial positions due to their Coulombic repulsion, is neglected. The correlation energy is consequently defined as the difference between the exact, non-relativistic energy of a system and its energy within the Hartree-Fock limit [4]. For chemical applications, particularly those involving bond breaking processes, this missing correlation energy must be accounted for, leading to the critical distinction between static and dynamic electron correlation.

This dichotomy forms the central core problem in the development of multireference perturbation methods for bond breaking research. While dynamic correlation pertains to the instantaneous, local correlations of electron motion, static correlation arises when a system's ground state cannot be qualitatively described by a single electronic configuration [4]. The failure of single-reference methods, such as standard coupled-cluster or perturbation theory, in describing bond dissociation stems directly from their inability to adequately handle strong static correlation effects [4] [5]. This whitepaper delineates the core definitions, methodological implications, and quantitative benchmarks essential for researchers navigating the complexities of electron correlation in chemical systems and drug development.

Defining Static and Dynamic Electron Correlation

Dynamic Electron Correlation

Dynamic electron correlation (DEC) refers to the local, short-range correlation in the instantaneous movements of electrons as they avoid each other due to Coulomb repulsion [4]. It is a ubiquitous effect present in all molecular systems. DEC is considered "dynamic" because it involves the correlated fluctuations of electrons around their average positions. In a simplified picture, it accounts for the "Coulomb hole"—the reduced probability of finding two electrons close to one another compared to the Hartree-Fock prediction.

Methods that build upon a single reference determinant, such as Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2, MP4), Coupled-Cluster (CCSD, CCSD(T)), and Configuration Interaction (CISD, CISDT), are primarily designed to capture dynamic correlation [4]. These post-Hartree-Fock methods add excitations from a single reference wavefunction to account for the instantaneous correlations. However, their performance is contingent on the quality of the reference wavefunction; when the reference HF wavefunction is a poor starting point, these methods fail dramatically.

Static Electron Correlation

Static electron correlation (SEC), also known as non-dynamical correlation, arises in situations where multiple electronic configurations are nearly degenerate and contribute significantly to the ground state wavefunction [4]. This occurs in several key scenarios:

- Bond Breaking and Forming: As a chemical bond is stretched, the HF reference becomes increasingly inadequate, and multiple determinants are needed for a qualitatively correct description [4].

- Open-Shell Transition Metal Complexes: Common in catalysis and organometallic chemistry, where near-degenerate d-orbitals lead to multiple important configurations.

- Diradicals and Biradicals: Molecules with two unpaired electrons, which are prevalent in photochemistry and some pharmaceutical intermediates.

SEC is considered "static" because it involves the mixing of different electronic configurations that are important for the correct zeroth-order description of the system, rather than just correcting a single good reference wavefunction. Systems with strong static correlation require a multi-configurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) wavefunction, such as a Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) wavefunction, as a starting point [4]. The CASSCF method accounts for static correlation by allowing all possible configurations within a selected active space of orbitals and electrons.

Table 1: Comparative Features of Static and Dynamic Electron Correlation

| Feature | Static Correlation (SEC) | Dynamic Correlation (DEC) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Near-degeneracy of multiple electronic configurations | Instantaneous Coulombic repulsion between electrons |

| Nature | Global, multi-configurational | Local, short-range corrections |

| Primary Methods | MCSCF, CASSCF, MR-CI | MP2, CCSD(T), CISD, DFT |

| Key Area of Application | Bond dissociation, diradicals, transition metal complexes | Thermochemistry, non-covalent interactions, molecular properties |

| Role in Bond Breaking | Essential for qualitative correctness at large separation | Necessary for quantitative accuracy across potential energy surface |

Methodological Approaches for Electron Correlation

The treatment of electron correlation requires a hierarchical approach to method selection, dictated by the relative importance of static versus dynamic effects in the system under study.

Single-Reference Methods

For systems where static correlation is negligible, single-reference methods provide excellent accuracy:

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: A computationally efficient approach to capture dynamic correlation, with MP2 being widely popular for its favorable cost-to-accuracy ratio [4].

- Coupled-Cluster Methods: Particularly CCSD(T), often considered the "gold standard" for single-reference systems, providing high accuracy for dynamic correlation [4].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Standard DFT approximations incorporate some dynamic correlation through the exchange-correlation functional, though the exact partitioning is not well-defined.

Multi-Reference Methods

When static correlation is significant, multi-reference approaches are necessary:

- Multi-Configurational SCF (MCSCF): Provides the foundational wavefunction by accounting for static correlation through the simultaneous optimization of orbitals and configuration coefficients [4].

- Multi-Reference Configuration Interaction (MR-CI): Adds dynamic correlation on top of a multi-reference wavefunction through excitation operators [5].

- Multi-Reference Perturbation Theory (e.g., CASPT2): A computationally efficient alternative to MR-CI that treats dynamic correlation using second-order perturbation theory based on a CASSCF reference [5].

Advanced and Hybrid Approaches

- Spin-Flip Methods: Novel approaches that can capture both static and dynamic correlation effects by using a high-spin reference state to describe low-spin states with broken bonds [5].

- Composite Methods: Combinations like CASPT2//CASSCF, where different methods handle different correlation components, providing a balanced treatment for challenging systems.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Quantum Chemical Methods for Bond Breaking in Hydrocarbons (Errors in kcal/mol) [5]

| Method | Methane C-H Bond Breaking (Entire Curve) | Methane C-H Bond Breaking (Intermediate Region) | Ethane C-C Bond Breaking (Entire Curve) | Ethane C-C Bond Breaking (Intermediate Region) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-CCSD | <3.0 NPE | ~0.1-0.2 NPE | Within 1.0 of MR-CI | Within 0.4 of MR-CI |

| SF with Triples | 0.32 NPE | ~0.35 NPE | N/A | N/A |

| MR-CI | <1.0 NPE | ~0.1-0.2 NPE | Reference | Reference |

| CASPT2 | ~1.2 NPE | ~0.1-0.2 NPE | 1.8 NPE | 0.4 NPE |

| FCI | Reference | Reference | N/A | N/A |

NPE (Nonparallelity Error) = |Maximum Error - Minimum Error| along the potential energy curve

Experimental Protocols for Probing Electron Correlation

Atomic Force Microscopy for Single Bond Rupture

Recent advances in scanning probe microscopy have enabled direct experimental investigation of bond breaking at the single-molecule level, providing quantitative data to validate theoretical predictions of electron correlation effects.

Experimental Setup and Materials:

- Microscope: High-resolution Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) using a qPlus sensor [6] [7].

- Environment: High-vacuum chamber at cryogenic temperature (4 Kelvin) to minimize thermal vibrations and external perturbations [6].

- Sample System: Iron phthalocyanine (FePc) molecules adsorbed on a Cu(111) surface, with carbon monoxide (CO) molecules dosed to form CO-FePc complexes [7].

- Probe Tips: Two distinct tip types employed: (1) CO-terminated tip (chemically inert), and (2) Bare copper tip (chemically active) [6] [7].

Methodology for Bond Rupture Measurement:

- Imaging: First, obtain high-resolution AFM images of the CO-FePc complex using non-contact AFM with a CO-terminated tip to characterize the initial system [7].

- Tip Approach: Precisely control the tip height using picometer increments while scanning across the center of the CO-FePc complex [6].

- Force Mapping: Record frequency shifts (Δf) of the AFM probe at different tip heights to construct a 3D force map [7].

- Bond Rupture Detection: Identify the breaking point through discontinuities in frequency shift curves and corresponding changes in image contrast [7].

- Force Calculation: Calculate interaction forces from measured frequency shifts using established methods [7].

- Post-Rupture Verification: Confirm bond rupture through subsequent imaging showing characteristic features of free FePc molecules [7].

Key Findings from AFM Experiments:

- The dative bond between CO and FePc ruptured under different mechanical forces depending on the tip type [6] [7].

- With a CO-terminated tip, bond breaking occurred via repulsive forces of 220 ± 30 pN [7].

- With a bare copper tip, bond breaking occurred via attractive forces of 150 ± 30 pN [7].

- Quantum-based simulations revealed significant contributions from shear forces and accompanying changes in the spin state of the system during bond rupture [7].

Computational Benchmarking Protocols

For theoretical validation of electron correlation methods, standardized benchmarking protocols are essential:

System Selection: Small to medium hydrocarbons (methane, ethane) for which high-level reference data (FCI, MR-CI) can be obtained [5].

Potential Energy Surface Mapping: Calculate energies across bond dissociation coordinates, from equilibrium geometry to separated fragments [5].

Error Metrics: Use Nonparallelity Error (NPE) defined as the absolute difference between maximum and minimum errors along the potential energy curve, providing a measure of balanced description across geometries [5].

Regional Analysis: Evaluate performance separately for the entire dissociation curve and the intermediate region (e.g., 2.5-4.5 Å) most relevant for chemical kinetics [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Methods for Electron Correlation Studies

| Item/Method | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Contact AFM with qPlus Sensor | Experimental Instrument | Measures mechanical forces during single bond rupture | Requires high vacuum and cryogenic temperatures (4K) for precise measurements [6] [7] |

| CO-Terminated Tip | Experimental Probe | Chemically inert tip for AFM imaging and repulsive force bond breaking | Exerts repulsive forces up to ~220 pN before bond rupture [7] |

| Metal (Cu) Tip | Experimental Probe | Chemically active tip for attractive force bond breaking | Ruptures dative bonds with attractive forces of ~150 pN [7] |

| FePc on Cu(111) | Model System | Well-defined coordination complex for bond breaking studies | Exhibits dative bonding with CO; shows trans effect upon ligand removal [7] |

| CASSCF | Computational Method | Handles static correlation via multi-configurational wavefunction | Active space selection critical for balanced description [4] |

| CASPT2 | Computational Method | Adds dynamic correlation to CASSCF via perturbation theory | Efficient balanced treatment for potential energy surfaces [5] |

| MR-CI | Computational Method | High-level treatment of both correlation types | Computationally demanding but provides benchmark quality results [5] |

| Spin-Flip CCSD | Computational Method | Single-reference approach capable of describing bond breaking | Uses high-spin reference to access diradical and bond-breaking states [5] |

| Real-Space DFT | Computational Method | Models tip-sample interactions in AFM experiments | Provides atomic-scale insights into bond rupture mechanisms [7] |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Electron Correlation Classification Diagram

AFM Bond Rupture Experimental Workflow

Multi-Reference Computational Strategy

The fundamental distinction between static and dynamic electron correlation represents a core consideration in the accurate theoretical description of bond breaking processes. Static correlation dominates the qualitative description of dissociated limits and strongly correlated intermediates, while dynamic correlation provides essential quantitative corrections across the entire potential energy surface. The integration of advanced experimental techniques, particularly single-molecule AFM force measurements, with sophisticated multi-reference computational methods creates a powerful framework for validating and refining our understanding of electron correlation effects.

For researchers in chemical kinetics, catalysis, and pharmaceutical development, this dichotomy necessitates careful method selection based on the specific chemical problem. Multi-reference perturbation theories like CASPT2 offer a balanced approach for systems with moderate static correlation, while more demanding methods such as MR-CI or novel spin-flip approaches may be required for challenging cases with extensive degeneracies. The quantitative benchmarks and experimental protocols outlined herein provide essential guidance for navigating these methodological choices in bond breaking research and drug development applications.

A foundational challenge in quantum chemistry is the accurate description of strongly correlated electrons, a phenomenon paramount in processes like chemical bond breaking and formation. Single-reference wavefunction methods, such as standard density functional theory (DFT) or Hartree-Fock, model electrons as interacting with a average field and often fail for systems where multiple electronic configurations contribute significantly to the wavefunction [8]. This is precisely the case in transition states, diradicals, and across bond dissociation potential energy surfaces [9].

Multireference (MR) methods were developed to address this limitation by using a wavefunction constructed from multiple electronic configurations [9]. Among these, the Complete Active Space (CAS) concept provides a systematic framework for selecting the most important configurations, offering a robust starting point for accurate quantum chemical simulations of challenging electronic structures. This guide details the core principles, computational protocols, and practical application of the CAS approach, with a specific focus on its role in multireference perturbation methods for bond breaking research.

Theoretical Foundations of Multireference Methods and CAS

The Limitation of Single-Reference Theories

Single-reference methods like DFT and Hartree-Fock begin with a single determinant description of the electron configuration. While computationally efficient, this approach fails when electron correlation causes several configurations to become near-degenerate. This "static" or "strong" correlation is not captured by single-reference models, leading to large errors, such as unrealistic barrier heights and incorrect dissociation limits [8]. For example, when a bond is broken, a single Slater determinant is a poor representation of the correct physical state, which is often a mixture of several configurations [9].

Multireference Wavefunctions and the Active Space

Multireference methods explicitly account for strong electron correlation by using a wavefunction that is a linear combination of multiple configuration state functions (CSFs) or determinants [9]. The central challenge is to select a manageable yet physically meaningful set of reference configurations. The Complete Active Space (CAS) approach, formalized as CASSCF (Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field), solves this by partitioning molecular orbitals into three subsets:

- Inactive Orbitals: Doubly occupied in all configurations.

- Virtual Orbitals: Unoccupied in all configurations.

- Active Orbitals: A carefully chosen set where electrons are distributed in all possible ways.

A CAS reference is denoted as CAS(n, m), where n is the number of active electrons and m is the number of active orbitals. The CASSCF method then variationally optimizes both the CI coefficients of the CSFs and the molecular orbitals simultaneously [1] [10].

CAS in the Context of Multireference Perturbation Theory

While CASSCF effectively captures static correlation, it often lacks dynamic correlation, which arises from the instantaneous repulsions between electrons. This can lead to insufficient accuracy for quantitative predictions [9]. The solution, and the core of modern multireference chemistry, is to combine a CAS reference with perturbation theory.

In this hybrid approach:

- A CASSCF calculation provides a zeroth-order multireference wavefunction that correctly describes the static correlation, such as that encountered during bond breaking.

- A perturbative method (e.g., CASPT2, NEVPT2, or GVVPT2) adds a correction to capture the dynamic correlation [9]. As noted in the ORCA manual, "NEVPT2 is typically the method of choice as it is fast and easy to use" [10]. This combined method (e.g., CASSCF/CASPT2) delivers a balanced description of both types of electron correlation across the entire potential energy surface.

Computational Protocols and Methodologies

The CASSCF Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for performing a CASSCF calculation, highlighting the critical decision points.

Active Space Selection Protocol

Selecting the appropriate active space is the most critical and expertise-dependent step. An ill-chosen active space will yield meaningless results. The following protocol provides a systematic approach for selecting the CAS(n, m) for bond breaking studies.

System Preparation:

- Initial Calculation: Perform a preliminary Hartree-Fock (HF) or DFT calculation on the molecular system at a geometry of interest (e.g., equilibrium or near the transition state).

- Orbital Localization: Transform the canonical molecular orbitals into localized orbitals using a method like Pipek-Mezey [1]. This is crucial as it converts delocalized orbitals into recognizable σ, π, and lone-pair orbitals, making selection intuitive.

Active Space Identification:

- Identify Correlated Electrons/Orbitals: For the bond being broken, include the corresponding bonding (σ) and antibonding (σ*) orbitals, along with the two electrons of the bond. This forms a minimal (2e,2o) active space.

- Include Adjacent Pi Systems: For conjugated systems or transition metals, extend the active space to include relevant π and π* orbitals, as well as metal d-orbitals and their electrons [9].

- Validation: Check the natural orbital occupations from an initial CASSCF calculation. Occupations significantly different from 2 or 0 (e.g., between 0.02 and 1.98) indicate orbitals that should be in the active space.

Calculation Execution:

- Run CASSCF: Using the selected active space, execute the CASSCF calculation. The program will variationally optimize the orbitals and CI coefficients.

- Convergence Check: Ensure the energy and wavefunction are properly converged. This may require adjusting convergence algorithms or initial guesses.

Perturbative Correction:

Key Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Computational "Reagents" for CAS-Based Calculations.

| Item/Component | Function in Calculation | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Guess Orbitals | Provides a starting point for the CASSCF orbital optimization. | Typically from a Hartree-Fock calculation. Crucial for convergence [1]. |

| Atomic Basis Set | Set of mathematical functions (Gaussians) used to construct molecular orbitals. | Larger basis sets (e.g., triple-zeta) are needed for accuracy but increase cost [8]. |

| Auxiliary Basis Set | Used for the Resolution of the Identity (RI) approximation to speed up integral computation. | Required for efficient MRCI/perturbation calculations; specific sets are recommended for accuracy [10]. |

| Active Space (CAS(n,m)) | Defines the set of orbitals and electrons treated with full configuration interaction. | The core user-defined parameter; accuracy hinges on its correct selection [10]. |

| Orbital Localizer | Algorithm to transform canonical orbitals into localized ones for intuitive active space selection. | Methods like Pipek-Mezey are standard [1]. |

Data Presentation and Software Implementation

Quantitative Performance of Multireference Methods

The computational cost and accuracy of quantum chemical methods vary significantly. The table below benchmarks common methods, highlighting the position of CAS-based approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Quantum Chemical Method Scaling and Application to Bond Breaking.

| Method | Typical Scaling | Handles Bond Breaking? | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | O(N⁴) | No | Simple, size-consistent | Lacks electron correlation, poor for bonds [8]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | O(N³) to O(N⁴) | Often fails (depends on functional) | Good cost/accuracy for many systems | Can fail for strong correlation [8]. |

| MP2 | O(N⁵) | No | Improves upon HF, includes dynamic correlation | Fails for static correlation, not for bond breaking [8]. |

| Coupled-Cluster (CCSD(T)) | O(N⁷) | No | "Gold standard" for single-reference systems | Prohibitively expensive, fails when reference is poor [8]. |

| CASSCF | Exponential in active space size | Yes | Captures static correlation, fundamental for MR | Lacks dynamic correlation, expensive active space [1] [9]. |

| CASPT2/NEVPT2 | Exponential + O(N⁵) | Yes | Captures both static & dynamic correlation | More complex than single-reference methods [10] [9]. |

Practical Software and Thresholds

Implementing these methods requires specialized software. The ORCA package documentation provides insight into critical parameters for its multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) module, which shares concepts with CASSCF [10].

- Integral Handling (

IntMode): The default mode performs a full integral transformation, which is memory-intensive. Using the Resolution of the Identity (RI) approximation with a suitable auxiliary basis set is recommended for larger systems [10]. - Selection Thresholds: Many MRCI programs are "individually selecting," meaning they include only CSFs that interact with the zeroth-order wavefunction more strongly than a threshold.

- Including Single Excitations (

AllSingles): With a CASSCF reference, single excitations do not interact directly with the reference but are important for properties. It is often necessary to force their inclusion [10].

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

Beyond Canonical CAS: Embedding and Localization

A fundamental limitation of canonical CASSCF is its exponential scaling, which restricts calculations to active spaces of about 18 electrons in 18 orbitals ("18e,18o") on classical computers [1]. This is often insufficient for realistic molecules in drug discovery or materials science. Quantum embedding methods like Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) have been developed to overcome this. These methods partition a large system into a smaller, strongly correlated fragment (treated with a high-level method like CASSCF) embedded in a mean-field environment [1]. This leverages the locality of electron correlation, enabling the application of multireference methods to complex molecules and extended materials.

The Role of Quantum Computing

Quantum computers offer a promising path forward due to their theoretical ability to simulate quantum systems with polynomial scaling [1]. Algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) can be used as the solver for the active space problem within a CASSCF-like framework, potentially allowing for the treatment of much larger active spaces than are possible classically [1]. While current hardware is too noisy for practical advantage, the integration of quantum embedding methods with quantum algorithms represents a cutting-edge research direction for extending the reach of multireference methods [1].

Logic of Modern Multireference Problem Solving

The field is evolving towards hybrid strategies that combine classical and emerging quantum techniques to tackle complex problems. The following diagram outlines this logical progression.

The Critical Role of Multireference Perturbation Theory (MRPT)

Multireference Perturbation Theory (MRPT) represents a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, providing a sophisticated framework for tackling quantum mechanical problems where single-reference methods fail. These multireference methods are widely regarded as some of the most accurate approaches in computational chemistry, particularly when studying entire potential energy surfaces (PESs) and excited electronic states [9]. The critical importance of MRPT emerges from its ability to handle systems with significant static correlation, such as bond dissociation processes, diradicals, and transition metal complexes, where the electronic structure cannot be adequately described by a single Slater determinant.

The theoretical foundation of MRPT rests on a hybrid variational-perturbational approach that captures large amounts of both dynamical and static correlation effects [9]. By combining the strengths of multiconfigurational wavefunctions with computationally efficient perturbation theory, MRPT methods achieve an exceptional balance between accuracy and computational feasibility for studying complex chemical phenomena, particularly bond breaking processes essential for understanding reaction mechanisms in drug development and materials science.

Theoretical Foundations of MRPT

The Mathematical Framework

Multireference Perturbation Theory begins with a variational treatment of a reference wavefunction composed of multiple electronic configurations, followed by perturbative inclusion of dynamic electron correlation. The methodology can be conceptually divided into several critical components:

- Reference Wavefunction: Typically a Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) wavefunction that provides a zeroth-order description incorporating static correlation

- Perturbative Correction: Second-order perturbation theory accounts for dynamic correlation effects from excitations outside the active space

- Hamiltonian Partitioning: $H = H0 + V$, where $H0$ is the zeroth-order Hamiltonian and V represents the perturbation

The mathematical formulation varies among different MRPT implementations, but all share the common goal of efficiently capturing electron correlation effects that are intractable for single-reference methods.

Addressing the Intruder State Problem

A significant challenge in practical MRPT applications is the intruder state problem, where low-energy virtual states cause divergences in the perturbation expansion [9]. Second-order Generalized Van Vleck Perturbation theory (GVVPT2) addresses this issue through a nonlinear, hyperbolic tangent resolvent, enabling finite, physically sensible results even for challenging systems like the Cr₂ dimer, notorious for its strong multireference character and susceptibility to this problem [9].

Table 1: Key MRPT Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Reference Type | Perturbation Order | Key Features | Size Extensivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASPT2 | CASSCF | Second | Widely used; requires level shift | Nearly extensive |

| NEVPT2 | CASSCF | Second | Internally contracted; strict separability | Strictly extensive |

| GVVPT2 | MCSCF | Second | Avoids intruder states; finite results | Nearly extensive |

| MRCISD(TQ) | MRCISD | Perturbative (TQ) | Includes triple/quadruple excitations | Reduces size-extensivity error |

MRPT Methodologies: A Technical Comparison

Established MRPT Approaches

The MRPT landscape encompasses several sophisticated methodologies, each with distinct theoretical foundations:

GVVPT2 (Generalized Van Vleck Perturbation Theory) operates as a variant of intermediate Hamiltonian quasidegenerate perturbation theory [9]. Similar to CASPT2 and other MRPT2 methods, GVVPT2 perturbatively includes singly and doubly excited configurations from an MCSCF reference. Its distinctive implementation generates an external space from single- and double-excitations from each configuration state function (CSF) in the reference, but constructs a matrix representation of only the primary-external interaction operator [9].

MRCISD(TQ) represents a higher-level approach that variationally considers reference functions and their single and double excitations, with perturbative treatment of triple and quadruple excitations [9]. While computationally intensive, this method delivers high accuracy and largely eliminates size-extensivity errors present in singles and doubles configuration interaction methods.

Emerging Methodologies: FragPT2

Recent innovations like FragPT2 demonstrate the ongoing evolution of MRPT methods. This novel embedding framework addresses multiple interacting active fragments by [11]:

- Assigning separate active spaces to fragments through localization of canonical molecular orbitals

- Solving each fragment with a multireference method while embedded in the mean field of other fragments

- Reintroducing interfragment correlations through multireference perturbation theory

This approach provides exhaustive classification of interfragment interaction terms, enabling analysis of processes such as dispersion, charge transfer, and spin exchange [11]. The method shows promise even for fragments defined by cutting through covalent bonds, significantly expanding the potential applications of MRPT in complex molecular systems.

Table 2: Computational Characteristics of MRPT Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Memory Requirements | Parallelization Strategy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVVPT2 | High | Extensive | MPI-based; macroconfiguration pairs | Transition metal dimers, excited states |

| MRCISD(TQ) | Very High | Very Extensive | Master/slave dynamic assignment | Multi-radicals, delocalized electrons |

| FragPT2 | Moderate-High | Moderate | Embarrassingly parallel fragment pairs | Large fragmented systems, covalent bonds |

Computational Implementation and Protocols

Efficient MRPT Computational Strategies

Implementing MRPT methods requires sophisticated computational strategies to manage the steep computational scaling:

Configuration-Driven Approach: Both GVVPT2 and MRCISD(TQ) utilize configuration-driven GUGA (Graphical Unitary Group Approach) to organize CSFs, significantly increasing efficiency in evaluating Hamiltonian matrix elements by avoiding line-up permutations [9].

Parallelization Schemes: MRPT calculations employ MPI-based parallelization using OpenMPI libraries, with specialized approaches that map pairs of macroconfigurations to nodes [9]. A master/slave scheme dynamically assigns macroconfigurations to available processors, crucial for load balancing given the varying sizes of macroconfigurations.

Wavefunction Compression: Techniques like internally or externally contracted CI functions can reduce computation time, though may sacrifice some correlation energy [9].

Experimental Protocol for MRPT Calculations

The following diagram outlines the generalized workflow for performing MRPT calculations:

Step 1: Active Space Selection

- Identify correlated molecular orbitals and electrons

- Balance computational feasibility with chemical accuracy

- For FragPT2: define molecular fragments based on chemical intuition [11]

Step 2: Reference Wavefunction Generation

- Perform CASSCF calculation to optimize orbitals and CI coefficients

- Ensure adequate description of static correlation

- For FragPT2: generate localized fragment orbitals and solve each fragment self-consistently [11]

Step 3: Perturbation Treatment

- Construct zeroth-order Hamiltonian appropriate for the specific MRPT method

- Apply perturbation theory to capture dynamic correlation

- For GVVPT2: employ nonlinear resolvent to avoid intruder states [9]

- For FragPT2: classify and include interfragment interaction terms [11]

Step 4: Analysis and Validation

- Compute total energies and property surfaces

- Compare with experimental data or higher-level calculations where available

- Analyze wavefunction character and correlation effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MRPT Research

| Tool/Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CASSCF Solver | Generates reference wavefunction | Critical for proper active space definition |

| Integral Transformation | Handles molecular integrals | Memory-intensive for large basis sets |

| Configuration Interaction | Manages CSF expansions | Exponential scaling with active space size |

| Perturbation Module | Computes second-order correction | Must address intruder state issues |

| Localization Algorithms | Fragment orbital construction | Essential for FragPT2 implementation [11] |

| MPI/OpenMP | Parallel computation | Required for practical application times |

Applications in Bond Breaking and Drug Development

MRPT methods provide critical insights for pharmaceutical research, particularly in understanding reaction mechanisms involving bond dissociation. The ability to accurately model potential energy surfaces across the entire bond-breaking coordinate makes MRPT invaluable for:

Reaction Mechanism Elucidation: MRPT accurately describes transition states and intermediates where bonds are partially broken, providing insights unavailable through single-reference methods.

Transition Metal Chemistry: Pharmaceutical catalysts often involve transition metals with strong static correlation effects. GVVPT2 has proven successful for challenging transition metal dimers [9].

Photochemical Processes: Drug photodegradation and photopharmacology require excited state modeling, where MRPT methods simultaneously address multiple electronic states [9].

The following diagram illustrates the MRPT application workflow in drug development:

The evolution of MRPT continues with emerging trends focusing on:

- Methodological Efficiency: Improved algorithms and computational strategies to extend application domains

- Embedding Approaches: Methods like FragPT2 that combine fragmentation with MRPT for larger systems [11]

- Machine Learning Enhancement: Potential integration of ML for active space selection and correlation energy prediction

Multireference Perturbation Theory remains indispensable for accurate quantum chemical simulations of processes involving bond breaking, excited states, and strongly correlated systems. Its continued development, particularly through innovative approaches like FragPT2, ensures MRPT will maintain its critical role in advancing computational chemistry, drug discovery, and materials science. The unique capability of MRPT methods to balance computational feasibility with high accuracy for challenging electronic structures makes them fundamental tools for researchers investigating complex chemical phenomena where qualitative insights from simpler methods prove inadequate.

A primary challenge in modern quantum chemistry is the accurate modeling of strong electron correlation, which arises when multiple electronic configurations become nearly degenerate and contribute significantly to the wavefunction. Single-reference methods, including standard density functional theory (DFT) and coupled-cluster theory, typically fail in these scenarios as they are based on the assumption that a single Slater determinant provides an adequate description of the electronic structure. Multireference (MR) methods address this limitation by explicitly considering multiple configurations from the outset. However, many high-level multireference approaches exhibit exponential scaling with system size, rendering them computationally prohibitive for large molecules and extended materials. Multireference Perturbation Theory (MRPT) strikes a balance between accuracy and computational feasibility by treating static correlation with a multiconfigurational wavefunction and adding dynamic correlation effects via perturbation theory. This technical guide examines three electronic scenarios where MRPT is indispensable—transition metal complexes, diradicals, and excited states—with particular emphasis on their relevance to bond-breaking research.

Theoretical Foundation of Multireference Methods

The Electronic Structure Problem

The non-relativistic electronic molecular Hamiltonian in second quantization forms the basis for all calculations:

[ \hat{H}=\sum{pq}^{N}h{pq}\hat{E}{pq}+\frac{1}{2}\sum{pqrs}^{N}V{pqrs}\hat{e}{pqrs}+V_{NN} ]

Here, ( \hat{E}{pq} ) and ( \hat{e}{pqrs} ) are spin-summed one- and two-electron excitation operators, ( h{pq} ) and ( V{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( V_{NN} ) is the nuclear repulsion energy. Accurately solving this Hamiltonian for strongly correlated systems requires methods that can handle the configurational quasi-degeneracy that arises when multiple determinants have similar weights. This is precisely where single-reference methods fail and multireference approaches become essential.

Quantum Embedding and Multireference Methods

Quantum embedding theories offer a promising solution to the scalability problem of multireference methods by partitioning complex systems into smaller, manageable subsystems. Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) has been particularly successful for systems with close-lying electronic states, including point defects in solids, spin-state energetics in transition metal complexes, magnetic molecules, and molecule-surface interactions. These applications are characterized by strong electron correlation that necessitates multireference treatment. The recent integration of DMET with active-space multireference quantum eigensolvers, such as the complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) method, demonstrates the synergy between embedding strategies and multireference approaches for treating correlation in extended systems.

Table 1: Key Quantum Embedding Approaches for Multireference Problems

| Embedding Method | Quantum Variable | Partitioning Scheme | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) | Density matrix | Fock matrix partitioning | Transition metal complexes, point defects |

| Dynamical Mean Field Theory (DMFT) | Green's function | Self-energy partitioning | Extended materials, periodic systems |

| Wavefunction-in-DFT | Electron density | Real-space partitioning | Reactive sites in large molecules |

| Self-Energy Embedding Theory (SEET) | Green's function | Self-energy partitioning | Strongly correlated clusters |

Transition Metal Complexes

Electronic Structure Challenges

Transition metal complexes present exceptional challenges for quantum chemical methods due to the presence of close-lying d-orbitals that lead to near-degeneracies, significant electron delocalization effects, and complex metal-ligand bonding. The competing electronic states often have strong multireference character, making single-reference methods unreliable for predicting spectroscopic properties, spin-state energetics, and reactivity.

Ab Initio Ligand Field Theory (AILFT)

The Ab Initio Ligand Field Theory (AILFT) approach provides a connection between first-principles electronic structure theory and the conceptual framework of ligand field theory. The original formulation extracts ligand field parameters by fitting the ligand field Hamiltonian to a complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) Hamiltonian. This extraction is unique when the active space consists of five metal d-based molecular orbitals for d-block elements. Recent developments in extended active space AILFT (esAILFT) circumvent previous limitations and are applicable to arbitrary active spaces, providing a more balanced description of metal-ligand covalency and reducing the exaggerated ionicity typical of CASSCF calculations.

Protocol for MRPT Treatment of Transition Metal Complexes

Active Space Selection: For first-row transition metals, begin with a minimal (10 electrons in 5 orbitals) active space containing the metal 3d orbitals. Extend this space to include ligand donor orbitals or a second d-shell for radial correlation using natural orbital analysis or atomic population criteria.

CASSCF Calculation: Perform a state-averaged CASSCF calculation including all states of interest to generate optimized orbitals that provide a balanced description of the electronic states.

Dynamic Correlation Treatment: Apply multireference perturbation theory (NEVPT2 or CASPT2) to incorporate dynamic correlation effects. Use an appropriate ionization potential-electron affinity (IPEA) shift and level shift to avoid intruder state problems.

Property Calculation: Compute electronic spectra, magnetic properties, and spin-state energy splittings from the MRPT wavefunctions.

Ligand Field Analysis: For AILFT, transform the CASCI matrix to the effective ligand field Hamiltonian basis and extract parameters like the Racah B parameter and ligand field splitting (10Dq).

Table 2: Active Space Selection Guidelines for Transition Metal Complexes

| Metal Center | Minimal Active Space | Common Extensions | Targeted Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-row (Sc-Cu) | 5d orbitals (10e,5o) | σ-donor ligands, 4d for radial correlation | Covalency, charge transfer |

| Second-row (Y-Ag) | 4d orbitals (10e,5o) | π-acceptor ligands, 5d for radial correlation | Relativistic effects, bonding |

| Third-row (Lu-Au) | 5d orbitals (10e,5o) | f-orbitals for actinides, full second shell | Spin-orbit coupling, bonding |

Diagram 1: MRPT workflow for transition metal complexes. The pathway shows the sequential steps from initial system setup through to final analysis.

Diradicals and Bond Breaking

Mechanochemical Bond Rupture in Diels-Alder Adducts

Substituted furan–maleimide Diels–Alder adducts represent important mechanophores with dynamic covalent bonds. While thermal retro-Diels–Alder reactions typically proceed via a concerted mechanism in the ground electronic state, asymmetric mechanical force applied along the anchoring bonds favors a sequential diradical pathway. This switching from concerted to sequential mechanism occurs at external forces of approximately 1 nN, with the first bond rupture requiring a projection of the pulling force on the scissile bond of approximately 4.3 nN for the exo adduct and 3.8 nN for the endo adduct.

Multireference Character Along the Reaction Path

In the intermediate region between the rupture of the first and second bond, the lowest singlet state exhibits pronounced diradical character and lies close in energy to a diradical triplet state. This near-degeneracy between singlet and triplet diradical states creates a challenging electronic structure scenario that necessitates multireference treatment. The computed spin–orbit coupling values along the path are typically too small to induce significant intersystem crossings, confining the reactivity to the singlet potential energy surface.

Protocol for MRPT Treatment of Diradical Bond Breaking

Reaction Path Mapping: Identify the bond dissociation coordinate and generate molecular structures along the reaction path using the mechanical force as a constraint.

Active Space Selection: For diradical systems, employ a minimum active space of 2 electrons in 2 orbitals (2e,2o) that represent the radical centers. Extend the space to include adjacent π-systems or polar groups that may participate in spin delocalization.

Reference Wavefunction: Perform state-averaged CASSCF calculations including both singlet and triplet states to ensure balanced description of the diradical character.

Dynamic Correlation: Apply MRPT (typically NEVPT2 or CASPT2) to capture dynamic correlation effects that are crucial for accurate energy gaps between electronic states.

Property Analysis: Calculate spin-density distributions, diradical character indices, and singlet-triplet gaps to characterize the electronic structure along the bond-breaking pathway.

Table 3: Quantitative Data for Furan–Maleimide Adduct Bond Breaking under Mechanical Force

| Parameter | Endo Adduct | Exo Adduct | Computational Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force for mechanism switch | ~1 nN | ~1 nN | Force-modified PES |

| First bond rupture force | ~3.8 nN | ~4.3 nN | CASSCF/NEVPT2 |

| Force inhibition threshold | ~3.4 nN | ~3.6 nN | Kinetic analysis |

| Rate enhancement at 4 nN | ~10³ faster | Reference | RRKM theory |

Diagram 2: Diradical mechanism in mechanochemical bond rupture. Under applied force, the reaction proceeds through a singlet diradical intermediate with a nearly degenerate triplet state.

Excited States and Conical Intersections

Limitations of Single-Reference Excited State Methods

Theoretical studies of molecular systems interacting with electromagnetic radiation require calculating potential energy surfaces for both ground and excited states. Single-reference methods like linear-response time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) fail to capture double excitations and exhibit incorrect topology at conical intersections, limiting their utility in photochemical simulations. The equation-of-motion coupled-cluster (EOM-CC) approach also struggles with systems exhibiting strong configurational quasi-degeneracy, particularly at stretched bond lengths.

State-Specific Multireference Approaches

State-specific multireference coupled-cluster (SSMRCC) theory provides a robust framework for excited state calculations by treating each state independently with a reference tailored to its specific character. The complete-active-space coupled-cluster (CASCC) method has demonstrated high accuracy for excited-state potential energy surfaces, outperforming EOMCC and multireference perturbation theory in benchmark studies on systems like hydrogen fluoride dissociation.

Advanced Methods: MRSF-TDDFT

Multi-Reference Spin-Flip Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (MRSF-TDDFT) represents a significant advancement that combines the practicality of linear response theory with multireference advantages. This approach successfully addresses key limitations of conventional TDDFT by:

- Correctly describing bond-breaking and bond-forming reactions

- Accurately treating open-shell singlet systems like diradicals

- Providing correct topology for conical intersections

- Incorporating double excitations into the response space

- Achieving balanced treatment of dynamic and nondynamic electron correlations

MRSF-TDDFT achieves accuracy comparable to high-level coupled-cluster methods for tasks like calculating adiabatic singlet–triplet gaps while maintaining computational efficiency similar to conventional TDDFT.

Protocol for MRPT Treatment of Excited States

State Classification: Identify the target excited states by their character (valence, Rydberg, charge-transfer) to guide active space selection.

Reference Calculation: Perform state-averaged CASSCF calculations including all states of interest to generate balanced orbitals.

Dynamic Correlation: Apply second-order N-electron valence state perturbation theory (NEVPT2) or CASPT2 to incorporate dynamic correlation effects crucial for accurate excitation energies.

Surface Mapping: Calculate potential energy surfaces along relevant nuclear coordinates, paying special attention to regions of avoided crossings and conical intersections.

Topology Verification: Check the dimensionality and topology of conical intersection seams to ensure proper description of nonadiabatic coupling regions.

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Excited State Methods for FH Dissociation

| Method | Description of Ground State | Description of Excited States | Conical Intersection Topology | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | Reasonable | Balanced but too ionic | Correct | High |

| CASPT2 | Good | Good with IPEA shift | Generally correct | Very High |

| EOM-CCSD | Poor at dissociation | Qualitative errors at dissociation | Incorrect | High |

| MRSF-TDDFT | Good | Excellent, includes double excitations | Correct | Moderate |

| SSMRCC | Excellent | Excellent | Correct | Very High |

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MRPT Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenQP | Software package | Implements MRSF-TDDFT method | Diradical character, conical intersections |

| esAILFT | Methodology extension | Extended active space ligand field analysis | Transition metal complex spectroscopy |

| DCD-CAS | Dynamic correlation method | Non-diagonal dressing of CASCI matrix | Improved LFT parameter extraction |

| ORCA | Electronic structure package | Multireference calculations with NEVPT2 | General MRPT applications across all scenarios |

| GAMESS | Quantum chemistry package | CASSCF and SSMRCC calculations | Excited state PES, bond dissociation |

Multireference perturbation theory provides an essential computational framework for treating strong electron correlation in three fundamental chemical scenarios: transition metal complexes, diradicals, and electronically excited states. The development of advanced methods like esAILFT for extended active spaces in transition metal systems, force-integrated approaches for mechanochemical diradical pathways, and state-specific multireference coupled-cluster theories for excited states continues to expand the applicability and accuracy of MRPT approaches. As quantum embedding techniques mature and quantum computing platforms advance, the integration of MRPT with these emerging technologies promises to further extend the reach of multireference methods in tackling complex bond-breaking phenomena across chemistry and materials science. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with essential tools for addressing these challenging electronic structure problems in their investigations of bond-breaking processes.

A Practical Guide to MRPT Methodologies: CASPT2, NEVPT2, and Beyond

The accurate computational description of molecular processes involving bond breaking, such as those in catalytic cycles or reactive intermediates, presents a significant challenge in quantum chemistry. Such processes are characterized by strong electron correlation, where a single electronic configuration is insufficient to describe the system's quantum mechanical state. Multireference methods were developed to address this challenge, with Complete Active Space Second-Order Perturbation Theory (CASPT2) emerging as a cornerstone for recovering dynamical electron correlation. This framework provides near-quantitative accuracy for ground and excited states, making it invaluable for research in drug development and materials science where understanding bond dissociation is critical [12] [13]. This guide details the historical development, theoretical underpinnings, and practical workflow of the CASPT2 method, contextualized within modern computational research.

Historical Development

The evolution of quantum chemical methods for treating electron correlation culminated in the development of CASPT2. The trajectory began with more approximate methods, progressively incorporating greater physical rigor.

Table 1: Key Milestones in Multireference Methods Pre- and Post-CASPT2

| Time Period | Methodological Development | Significance for Bond Breaking |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1990s | Multireference Configuration Interaction (MRCI) [14] | Provided accurate potential energy curves but with prohibitively high computational cost, limiting application to small molecules like water dimer [14]. |

| Early 1990s | Application of MRCI to systems like O-H bond breaking in water monomer and dimer [14] | Demonstrated the necessity of multireference methods for accurately modeling bond dissociation pathways in both isolated and interacting systems. |

| 1990s | Introduction and development of CASPT2 | Addressed the scalability issues of MRCI by combining a multiconfigurational zeroth-order wavefunction with efficient perturbation theory. |

| Recent Advances | Data-Driven CASPT2 (DDCASPT2) [12] | Uses machine learning to capture dynamical correlation from lower-level features, offering near-CASPT2 accuracy with reduced computational cost. |

| Recent Advances | Analytic CASPT2 Gradients with Implicit Solvation [13] | Enables efficient geometry optimization in solution, critical for modeling biochemical reactions and drug-receptor interactions. |

| Future Outlook | Integration with Quantum Computing Embedding [15] [1] | Aims to leverage quantum algorithms for the active space problem, potentially extending CASPT2's accuracy to much larger systems. |

The drive to develop CASPT2 was rooted in the need for a computationally feasible yet accurate method that could handle the multiconfigurational character of transition states and dissociated bonds, which single-reference methods like coupled-cluster theory fail to describe correctly [16]. The recent innovation of DDCASPT2 represents a paradigm shift, moving from a purely first-principles calculation to a data-driven approach that maintains physical interpretability through game-theoretic feature analysis [12]. Furthermore, the development of analytic first-order derivatives for CASPT2 combined with solvation models has dramatically expanded its practical utility, allowing researchers to optimize molecular geometries in realistic solvent environments reliably [13].

Theoretical Foundations

The CASPT2 method is a hybrid approach that separates the problem of electron correlation into two parts: static and dynamic. Its theoretical rigor stems from a well-defined separation of the electronic wavefunction.

The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) Zeroth-Order Wavefunction

The foundation of a CASPT2 calculation is a CASSCF wavefunction. This step accounts for static correlation (or near-degeneracy correlation), which is essential for describing bond breaking. The active space is defined by distributing a certain number of electrons in a set of active orbitals, denoted as CAS(n,m), where 'n' is the number of active electrons and 'm' is the number of active orbitals. The CASSCF wavefunction is a linear combination of all possible configuration state functions (CSFs) generated by distributing the n electrons in all possible ways among the m orbitals. This provides a qualitatively correct description of the wavefunction at a geometry where bonds are broken.

Second-Order Perturbation Theory (PT2)

The CASSCF wavefunction, while capturing static correlation, lacks dynamical correlation—the instantaneous correlation of electron motion due to Coulomb repulsion. CASPT2 treats this dynamical correlation as a perturbation on the CASSCF zeroth-order wavefunction. The method computes the first-order correction to the wavefunction and the second-order correction to the energy, resulting in quantitative accuracy. The effective Hamiltonian is given by:

[ \hat{H}{\text{eff}} = \hat{H}0 + \hat{V} ]

where (\hat{H}_0) is the zeroth-order Hamiltonian and (\hat{V}) is the perturbation. The second-order energy correction (E^{(2)}) is obtained by summing over all excited states relative to the CASSCF reference.

Figure 1: Theoretical workflow of the CASPT2 method, showing the sequential treatment of static and dynamic correlation.

Detailed Workflow and Protocols

A successful CASPT2 calculation requires careful execution of several steps, from active space selection to final energy evaluation. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology.

Figure 2: A practical workflow for performing CASPT2 calculations, from initial setup to final analysis.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

System Preparation and Mean-Field Calculation

- Input Preparation: Define the molecular geometry in Cartesian coordinates or internal coordinates. Select an appropriate atomic basis set (e.g., cc-pVDZ, ANO-RCC).

- Initial Guess: Perform a Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation. This provides the initial molecular orbitals and one-electron integrals.

Active Space Selection (CAS(n,m))

- This is the most critical step. The active space must include all orbitals directly involved in the bond breaking/forming process.

- For a typical O-H bond dissociation in water, the active space would be CAS(4,4), comprising 2 electrons in the σ bonding orbital, 2 electrons in the σ* antibonding orbital, and potentially lone pairs.

- Protocol for Complex Systems: For transition metal complexes or larger organic molecules, use chemical intuition and automated tools (e.g., atomic orbital participation, natural orbital occupation numbers from a preliminary correlated calculation) to select the active space.

CASSCF Calculation

- Orbital Optimization: Perform the CASSCF calculation to optimize the molecular orbitals within the active space. This is an iterative process.

- Convergence Check: Ensure the energy and density matrix have converged to a stable minimum. The resulting wavefunction and orbitals serve as the reference for CASPT2.

CASPT2 Energy Calculation

- Perturbation Setup: Specify the level of theory (e.g., single-state CASPT2 (SS-CASPT2) or multi-state CASPT2 (MS-CASPT2) for excited states).

- Execute Perturbation: The code computes the second-order energy correction. This step is non-iterative but can be computationally demanding due to the large number of excitations.

Geometry Optimization (Using Analytic Gradients)

- Gradient Calculation: Use the recently developed analytic first-order derivatives of CASPT2 [13] to compute the energy gradient with respect to nuclear coordinates.

- Optimization Cycle: Employ quasi-Newton methods (e.g., BFGS) to optimize the geometry to a minimum or transition state. For solution-phase studies, the gradient equations are solved with a modified Z-vector equation incorporating the polarizable continuum model (PCM) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Methods in the CASPT2 Workflow

| Tool/Reagent | Function in CASPT2 Workflow | Representative Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Basis Sets | Mathematical functions representing electron orbitals; larger bases improve accuracy but increase cost. | Correlation-consistent (cc-pVXZ) sets, Atomic Natural Orbital (ANO-RCC) sets. |

| Active Space Orbitals | The subset of orbitals where electrons are correlated; defines the multiconfigurational reference. | Selected based on chemical intuition (e.g., bonding/antibonding pairs in breaking bonds) or automated algorithms. |

| Mean-Field Reference | Provides the initial set of molecular orbitals for active space selection and CASSCF. | Typically Hartree-Fock (HF) [12] [17]. |

| Implicit Solvation Model | Mimics the effect of a solvent environment on the molecular system's electronic structure. | Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), used with analytic gradients for solution-phase geometry optimization [13]. |

| Embedding Potential | In hybrid quantum-classical or quantum computing methods, this potential represents the environment's effect on the active fragment [15] [1]. | Used in methods like range-separated DFT embedding to study localized states in materials [15]. |

Current Research and Future Directions

The CASPT2 framework is actively evolving, with current research focused on extending its applicability and integrating it with cutting-edge computational paradigms.

Data-Driven Correlation and Machine Learning: The novel Data-Driven CASPT2 (DDCASPT2) method captures dynamical electron correlation using machine learning models trained on features from lower-level methods like HF and CASSCF [12]. This approach, which uses SHAP analysis for feature interpretability, provides a promising path to near-CASPT2 accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, though it currently relies on training data from a diverse set of molecules [12].

Integration with Quantum Computing: A general framework for active space embedding is being developed to couple CASSCF and CASPT2 with quantum computations [15] [1]. In this scheme, the complex active space problem could be offloaded to a quantum processor using algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), while the rest of the system is treated classically. This hybrid approach aims to overcome the exponential scaling of traditional active space methods [15] [1].

Advanced Error Mitigation for Strong Correlation: For quantum computations of strongly correlated systems, Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) has been developed. This technique improves upon single-reference error mitigation by using compact multireference states (linear combinations of Slater determinants) prepared via Givens rotations, thereby enhancing the accuracy of quantum simulations for bond dissociation problems [17].

These advancements indicate a future where the core CASPT2 framework is not replaced but rather enhanced by machine learning and quantum computing, solidifying its role as a critical tool for modeling complex chemical phenomena in academic and industrial research.

Accurately modeling chemical systems where electron correlation effects are paramount, such as bond dissociation, excited states, and transition metal complexes, remains a central challenge in quantum chemistry. Single-reference methods like density functional theory (DFT) often struggle in these situations, necessitating multireference (MR) approaches. Among these, the complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) method provides a robust description of static correlation by performing a full configuration interaction within a carefully selected active space of orbitals and electrons [18]. However, for quantitative accuracy, the dynamic correlation stemming from the instantaneous interactions between electrons must also be captured.

This whitepaper examines Second-Order N-Electron Valence State Perturbation Theory (NEVPT2), a multireference perturbation theory that serves as an intruder-free alternative to other methods like CASPT2. Framed within a broader thesis on multireference methods for bond-breaking research, this document details the theoretical foundation, computational advantages, practical protocols, and applications of NEVPT2, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an in-depth guide to this powerful technique.

Theoretical Foundation of NEVPT2

NEVPT2 is a multireference perturbation theory designed to treat both static and dynamic correlation in a balanced manner. Its theoretical structure is built upon several key components.

The Dyall Hamiltonian

A cornerstone of NEVPT2 is its use of the Dyall Hamiltonian as the zeroth-order Hamiltonian [19]. The Dyall Hamiltonian is a block-diagonal Hamiltonian that acts only within the active space and contains the one-electron and Coulomb interaction terms for the inactive (doubly occupied) and virtual (unoccupied) spaces. This sophisticated choice ensures that the resulting perturbation theory is intruder-state-free, meaning it avoids the numerical instabilities that plague other methods like CASPT2 when a state in the first-order interaction space has an energy very close to the reference state [18]. Furthermore, NEVPT2 is parameter-free, eliminating controversies associated with parameters such as the IPEA shift in CASPT2 [18].

Contracted and Uncontracted Formulations

NEVPT2 can be implemented in different variants, primarily distinguished by how the first-order interacting space is handled [19]:

- Strongly Contracted (SC-NEVPT2): All configuration state functions (CSFs) belonging to a particular class (or subspace) are gathered into a single "perturber" function. This is the most computationally efficient variant.

- Partially Contracted (PC-NEVPT2): A larger set of perturber functions is constructed, leading to a more accurate but computationally demanding treatment.