Optimizing Active Learning for Chemical Space Exploration: Strategies for Enhanced Model Performance in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing active learning (AL) models to efficiently navigate vast chemical spaces.

Optimizing Active Learning for Chemical Space Exploration: Strategies for Enhanced Model Performance in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing active learning (AL) models to efficiently navigate vast chemical spaces. It covers the foundational principles of AL, including key query strategies like uncertainty and diversity sampling, and explores their integration with advanced machine learning techniques such as Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) and graph neural networks. Through methodological deep dives and real-world case studies in virtual screening and molecular property prediction, we outline best practices for troubleshooting common challenges like model robustness and data quality. Finally, the article presents rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of AL strategies, highlighting their proven impact on accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic compounds and materials.

Core Principles of Active Learning for Navigating Chemical Space

Defining Active Learning and Its Strategic Advantage in Data-Scarce Environments

Core Concept: What is Active Learning and How Does it Address Data Scarcity?

Active Learning is a supervised machine learning approach that uses an iterative feedback process to strategically select the most valuable data points for labeling from a large pool of unlabeled data [1] [2]. By focusing on the most informative samples, it minimizes the amount of labeled data required to train high-performance models, making it a powerful solution for data-scarce environments common in chemical and materials research [3].

The fundamental process involves an algorithm that actively queries an oracle (e.g., a computational simulation or a human expert conducting a lab experiment) to label the most informative data points [4] [5]. These newly labeled points are then used to update the model, creating a cycle that continuously improves model performance with minimal data [1].

Table: Active Learning vs. Traditional Passive Learning

| Feature | Active Learning | Passive Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Selection | Strategic querying of informative samples [1] | Uses a pre-defined, static dataset [1] |

| Labeling Cost | Significantly reduced [3] [1] | High, as all data must be labeled upfront |

| Adaptability | High; adapts to new, informative data [3] | Low; model is static after training |

| Model Performance | Can achieve higher accuracy with fewer labeled examples [3] [1] | Requires large volumes of data for high accuracy |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My initial dataset is very small. Will active learning still be effective?

A: Yes, this is precisely where active learning excels. A prominent study successfully explored a virtual search space of one million potential battery electrolytes starting from just 58 data points, ultimately identifying four high-performing electrolytes. The key is to use an initial dataset that is small but representative to seed the learning process effectively [6] [7].

Q2: During exploitative active learning, my model gets stuck proposing very similar compounds (analog bias). How can I improve scaffold diversity?

A: Analog identification is a known challenge in exploitative campaigns. Consider implementing the ActiveDelta approach. Instead of predicting absolute molecular properties, this method trains models on paired molecular representations to predict property improvements from your current best compound. This has been shown to identify more potent inhibitors while also achieving greater diversity in the discovered chemical scaffolds [8].

Q3: For regression tasks in materials science, how can I make the data selection more robust?

A: For regression tasks like predicting material properties, consider advanced query strategies that go beyond simple uncertainty sampling. The Density-Aware Greedy Sampling (DAGS) method integrates uncertainty estimation with data density, ensuring that selected points are both informative and representative of the broader data distribution. This has proven effective in training accurate regression models for functionalized nanoporous materials with a limited number of data points [5].

Q4: How do I validate that my active learning model is providing real-world value and not just optimizing for a computational proxy?

A: The most robust validation is to close the loop with real experiments. In the battery electrolyte study, the team did not rely solely on computational scores. They actually built and cycled batteries with the AI-suggested electrolytes, using the experimental results (e.g., cycle life) to feed back into the AI for further refinement. This "trust but verify" approach ensures your model optimizes for practical success [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

General Active Learning Workflow for Chemical Space Exploration

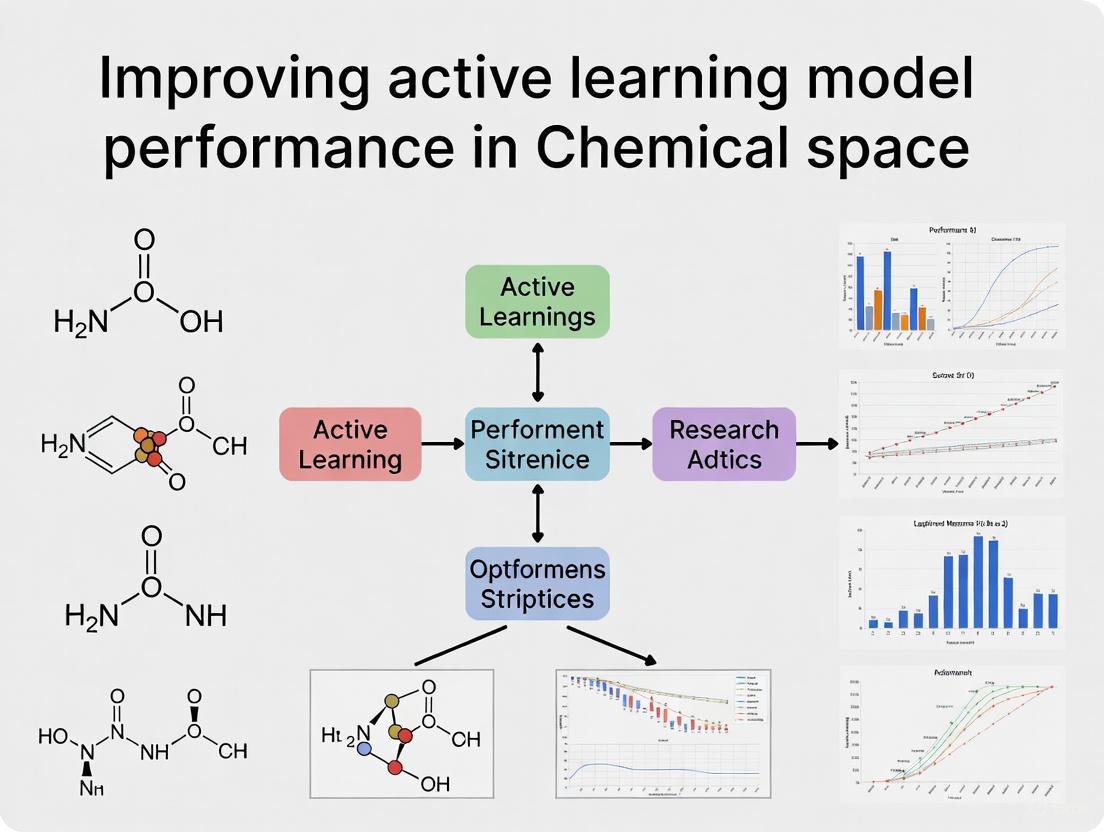

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative cycle of an active learning campaign, as applied to problems like virtual screening or materials discovery.

Protocol: Exploitative Active Learning for Potent Inhibitor Discovery

This protocol uses the ActiveDelta approach to directly optimize for compound potency, which is highly effective in low-data regimes [8].

Step 1: Initial Dataset Formation

- Select two random data points from your available training data to form the initial active learning training set. The remaining data points constitute the "learning pool" [8].

Step 2: ActiveDelta Model Training

- Cross-merge all compounds in the current training set to create pairs.

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., a paired-molecule Chemprop or XGBoost) to learn and predict the difference in potency (e.g., ΔKi) between the two molecules in each pair [8].

Step 3: Candidate Selection for the Next Experiment

- Identify the single most potent molecule in your current training set.

- Pair this best molecule with every molecule in the learning pool.

- Use the trained ActiveDelta model to predict the potency improvement for each of these pairs.

- Select the molecule from the learning pool that is part of the pair with the highest predicted potency improvement [8].

Step 4: Oracle Query and Model Update

- Acquire the true potency value for the selected molecule via your oracle (experimental assay or high-fidelity simulation).

- Add this newly labeled molecule to your training set.

- Retrain the ActiveDelta model on the updated, cross-merged training set.

- Repeat from Step 3 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a potency goal is achieved or a labeling budget is exhausted).

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Active Learning

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Active Learning Workflow |

|---|---|

| Alchemical Free Energy Calculations | Serves as a high-accuracy "oracle" for predicting ligand binding affinities to train ML models [4]. |

| Molecular Docking (e.g., Glide) | Used as a physics-based oracle to score protein-ligand interactions and find potent hits in ultra-large libraries [9]. |

| RDKit | Provides tools for generating molecular fingerprints, descriptors, and 3D coordinates for ligand representation [4]. |

| Pre-trained Chemical Language Models (e.g., CycleGPT) | Enables generative exploration of chemical space, such as macrocyclic compounds, overcoming data scarcity via transfer learning [10]. |

Advanced Query Strategies

The "query strategy" is the logic used to select the next data points. The optimal choice depends on your primary goal.

Table: Comparison of Active Learning Query Strategies

| Query Strategy | Primary Goal | Mechanism | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling [3] [1] | Improve Model Accuracy | Selects data points where the model's prediction confidence is lowest. | Rapidly improving overall model performance. |

| Diversity Sampling [3] [1] | Explore Chemical Space | Selects data points most dissimilar to the existing labeled set. | Initial stages to avoid bias and ensure broad coverage. |

| Exploitative (Greedy) [4] | Find Top Candidates | Selects data points with the best-predicted property (e.g., potency). | Quickly finding the most active compounds or best-performing materials. |

| Mixed Strategy [4] | Balanced Approach | Identifies top predicted candidates, then selects the most uncertain among them. | Balancing the discovery of high performers with model improvement. |

| Query-by-Committee [3] [1] | Improve Robustness | Selects data points where multiple models in an ensemble disagree. | Complex problems where a single model may be unreliable. |

Workflow: Integrating Active Learning in a Virtual Screening Pipeline

The following diagram details a specific workflow for using active learning to triage a large chemical library, incorporating multiple query strategies and a high-fidelity oracle.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core objective of a query strategy in Active Learning? The primary goal is to strategically select the most informative data points from a large pool of unlabeled samples to be labeled by an oracle (e.g., through experiments or high-fidelity computations). This process aims to train high-performance machine learning models while minimizing the costly and time-consuming process of data acquisition [11] [2].

2. When should I use Uncertainty Sampling over Diversity Sampling?

- Use Uncertainty Sampling when your model's predictions are unstable and you need to improve accuracy on challenging, ambiguous cases. It is highly effective for refining decision boundaries in classification or improving predictions in complex regions of a continuous output space [12] [2] [13].

- Use Diversity Sampling when you are in the early stages of learning or dealing with a highly heterogeneous chemical space. It ensures broad exploration and helps prevent the model from overlooking novel or underrepresented molecular scaffolds [11] [14].

3. My Uncertainty Sampling strategy is selecting outliers and not improving overall model performance. What is wrong? This is a common pitfall. Pure uncertainty sampling can be misled by noisy or anomalous data points that the model will always find difficult to predict. To fix this, consider a hybrid approach:

- Integrate density-awareness: Combine the uncertainty measure with the underlying data distribution density to avoid querying outliers in sparse regions [11].

- Use Query-by-Committee: The committee's disagreement is a more robust measure of uncertainty that is less susceptible to individual model artifacts [15].

4. How do I choose the right committee size for Query-by-Committee (QbC)? While a larger committee can offer a more robust variance estimate, it also increases computational costs. Empirical studies, such as those used to build the QDπ dataset, often use a committee of 4 to 5 models trained with different initializations or subsets of data. This size has proven effective for reliable uncertainty estimation without prohibitive computational overhead [15].

5. How can I address data imbalance with these query strategies? Active learning is particularly useful for imbalanced datasets. Strategic sampling techniques can be integrated within the AL framework to ensure minority classes are adequately represented.

- Uncertainty-based sampling can identify the rare active compounds that the model finds most difficult to classify, thereby enriching the training set with informative minority class examples [12].

- Combining ensemble learning with strategic k-sampling (dividing data into k-ratios) has been shown to successfully handle severe class imbalance in toxicity prediction, maintaining model stability and performance [12].

6. Can these strategies be applied to regression tasks, like predicting energy or binding affinity? Yes, though it is more complex than classification. For regression:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Use the predictive variance from models like Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) or the variance across an ensemble of neural networks [11] [13].

- Diversity Sampling: Methods like Greedy Sampling (GS) maximize the spread of selected points in the feature space [11].

- Advanced Hybrid: The Density-Aware Greedy Sampling (DAGS) method combines uncertainty with data density, proving effective for materials property prediction [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Generalization Despite High Confidence Selections

- Problem: Your active learning model seems to be stuck, selecting points that no longer lead to performance improvements on a hold-out test set. The model may be overfitting to the peculiarities of its current selected training set.

- Diagnosis: This is often a sign of sampling bias, where the query strategy has exploited its own model's weaknesses and failed to adequately explore broad regions of the chemical space [11].

- Solution: Recalibrate the exploration-exploitation balance.

- Shift to a Hybrid Strategy: If you started with pure Uncertainty Sampling, introduce a Diversity Sampling component. A framework that begins with a diversity-focused phase before switching to uncertainty or objective-driven selection has been shown to outperform static strategies [14].

- Implement a Schedule: Start the AL process with a strong emphasis on diversity and representative sampling. After a set number of iterations or when the model stabilizes, gradually increase the weight of the uncertainty criterion [11] [14].

Issue 2: Inefficient Sampling in Vast Chemical Spaces

- Problem: The computational cost of evaluating the query strategy (e.g., calculating uncertainty for billions of molecules) becomes a bottleneck, making the AL process impractically slow.

- Diagnosis: The strategy is not scalable to ultra-large libraries, such as multi-billion-molecule make-on-demand databases [16].

- Solution: Use a two-stage screening pipeline.

- Rapid Pre-screening: Employ a fast machine learning classifier, such as CatBoost, to process the entire vast library. Using the conformal prediction framework, this classifier can identify a much smaller subset of molecules that are likely to be top-scoring or high-uncertainty [16].

- Focused Evaluation: Apply your more computationally expensive AL query strategy (e.g., docking, high-fidelity simulation) only to this pre-filtered, promising subset. This workflow can reduce the number of compounds needing explicit scoring by over 1,000-fold [16].

Issue 3: High Variance in Model Performance During AL Cycles

- Problem: The performance of your model fluctuates significantly with each new batch of selected data, making it difficult to assess true progress.

- Diagnosis: This is common in Query-by-Committee if the committee members are too similar (low diversity) or if the uncertainty estimates are poorly calibrated [13] [15].

- Solution: Enhance committee diversity and calibration.

- Diversify the Committee: Ensure committee members are meaningfully different. Train them on different data subsets (bagging), with different model architectures, or with different hyperparameters [15].

- Calibrate Uncertainty: If using GPR, optimize hyperparameters via marginal log-likelihood. For ensemble variance, consider using a cheap, low-fidelity model to approximate and correct for the bias, as in the LFaB (Low-Fidelity as Bias) method, which can lead to more stable and optimal sample selection [13].

Comparison of Key Query Strategies

The table below summarizes the core principles, strengths, and weaknesses of the three key query strategies.

| Strategy | Core Principle | Typical Metric | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling | Selects data points where the model's prediction is least confident. | Entropy (classification); Variance (GPR/Ensemble regression) [12] [13]. | Highly efficient at refining model boundaries; directly targets model weaknesses. | Prone to selecting outliers; can ignore underlying data distribution [11]. |

| Diversity Sampling | Selects data points that maximize coverage and variety in the feature space. | Greedy Sampling (GSx); Clustering-based selection [11] [14]. | Ensures broad exploration; good for initial model building and discovering novel scaffolds. | May select many uninformative points from dense, well-understood regions [11]. |

| Query-by-Committee (QbC) | Selects points where a committee of models most disagrees. | Vote entropy (classification); Variance of predictions (regression) [15]. | Robust uncertainty estimation; less susceptible to noise from a single model. | Computationally expensive; performance depends on committee diversity [13] [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Query-by-Committee for Dataset Pruning

This protocol details the use of QbC to create a non-redundant, diverse dataset, as demonstrated in the construction of the QDπ dataset [15].

- Objective: To efficiently select a minimal subset of molecular structures from a large source database that retains maximum chemical diversity for training a machine learning potential (MLP).

- Materials: A large source database of molecular structures (e.g., from the ANI or SPICE datasets).

- Method: a. Initialization: Begin with an initial training set (can be small or empty). b. Committee Training: Train 4 independent MLP models on the current training set using different random seeds. c. Uncertainty Estimation: For every structure in the source database, calculate the standard deviation of the predicted energies and atomic forces across the 4 committee models. d. Selection Criterion: Apply pre-defined thresholds (e.g., energy std < 0.015 eV/atom and force std < 0.20 eV/Å). Structures with uncertainty above these thresholds are considered informative. e. Batch Selection: From the pool of informative candidates, randomly select a batch (e.g., up to 20,000 structures) for labeling with the high-fidelity method (e.g., ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD DFT calculations). f. Iteration: Add the newly labeled data to the training set and repeat steps b-e until all structures in the source database are either included or deemed redundant by falling below the uncertainty thresholds.

- Validation: The resulting dataset (e.g., QDπ) should be benchmarked by training a final MLP and evaluating its accuracy on a separate, high-fidelity holdout test set.

Protocol 2: Density-Aware Active Learning for Materials Regression

This protocol is based on the Density-Aware Greedy Sampling (DAGS) method designed to address limitations in materials science regression tasks [11].

- Objective: To train an accurate regression model for materials properties (e.g., gas uptake in MOFs) with a minimal number of data points, especially in non-homogeneous design spaces.

- Materials: A large pool of unlabeled material candidates (e.g., a database of Metal-Organic Frameworks).

- Method: a. Model Setup: Choose a regression model capable of uncertainty estimation, such as an ensemble or Gaussian Process. b. Integrated Criterion: The DAGS method integrates two components: i. Uncertainty: The model's predictive variance for a candidate. ii. Density: The local data density around the candidate, preventing over-selection from sparse outlier regions. c. Iterative Query: In each AL cycle, the candidate that maximizes a combined score of uncertainty and density-awareness is selected for labeling (e.g., via a computational simulation). d. Model Update: The newly acquired data is added to the training set, and the model is retrained.

- Validation: Compare the learning curve (model performance vs. number of labeled samples) of DAGS against baselines like random sampling and pure greedy sampling (iGS). DAGS has been shown to consistently outperform these methods on datasets with heterogeneous data distributions [11].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a unified active learning workflow that integrates multiple query strategies, adaptable for applications like photosensitizer design or virtual screening [14] [16].

Unified Active Learning Workflow for Chemical Space Exploration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function in Active Learning | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A probabilistic model that provides native uncertainty estimates (variance) for its predictions. | Used for uncertainty sampling in regression tasks, such as predicting potential energy surfaces or material properties [13]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A machine learning architecture that operates directly on molecular graph structures, learning rich representations. | Serves as a surrogate model for predicting molecular properties (e.g., S1/T1 energies) in an AL-driven photosensitizer design [14]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., Morgan/ECFP) | Fixed-length vector representations of molecular structure that encode chemical features. | Used as input features for machine learning classifiers (e.g., CatBoost) to rapidly pre-screen ultra-large chemical libraries [16]. |

| Conformal Prediction (CP) Framework | A method that produces predictions with statistically guaranteed confidence levels, handling class imbalance well. | Used to control the error rate when a classifier filters a billion-molecule library down to a manageable virtual active set for docking [16]. |

| Hybrid ML/MM Potential Energy Functions | Combines the speed of machine learning with the physics-based accuracy of molecular mechanics. | Used in FEgrow software to efficiently optimize ligand binding poses during structure-based de novo design guided by AL [17]. |

This technical support center provides practical guidance for implementing Active Learning (AL) loops in chemical space research and drug discovery. Active Learning is an iterative experimental strategy that selects the most informative new data points to maximize predictive model performance while minimizing resource expenditure [18]. This approach is particularly valuable in low-data scenarios typical of early drug discovery, where it has been shown to achieve up to a sixfold improvement in hit discovery compared to traditional screening methods [19].

Our FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common challenges researchers face when deploying these systems, with specific focus on human-in-the-loop frameworks, batch selection methods, and integration with goal-oriented molecule generation.

FAQs: Addressing Common Active Learning Implementation Challenges

FAQ 1: What is the core principle behind selective data acquisition in Active Learning for drug discovery?

Active Learning employs a strategic acquisition criterion to select which experiments would contribute most to improved predictive accuracy [20]. Rather than testing all possible compounds or using simple random selection, AL algorithms identify molecules that are poorly understood by the current property predictor—typically those with high predictive uncertainty—and prioritize them for experimental validation [20]. This creates a continuous feedback loop where each iteration of experimental data enhances model generalization for subsequent generation cycles, dramatically reducing the number of experiments needed to achieve target performance [18].

FAQ 2: How does human-in-the-loop Active Learning improve molecular property prediction?

Human-in-the-loop (HITL) Active Learning integrates domain expertise to address limitations in training data [20]. Chemistry experts confirm or refute property predictions and specify confidence levels, providing high-quality labeled data that refines target property predictors [20]. This approach is particularly valuable when immediate wet-lab experimental labeling is impractical due to time and cost constraints. Empirical results demonstrate that a reward model trained on feedback from chemistry experts significantly improves optimization of bioactivity predictions, ensuring that QSAR predicted scores optimized during molecular generation align better with true target properties [20].

FAQ 3: What are the practical considerations for implementing batch Active Learning in drug discovery pipelines?

Batch Active Learning selects multiple samples for labeling in each cycle, which is more realistic for small molecule optimization than sequential selection [18]. The key computational challenge is that samples are not independent—they share chemical properties that influence model parameters—so selecting a set based on marginal improvement doesn't reflect the improvement provided by the entire batch [18]. Effective batch methods must balance "uncertainty" (variance of each sample) and "diversity" (covariance between samples) by selecting subsets with maximal joint entropy [18]. Implementation requires specialized approaches like COVDROP or COVLAP that compute covariance matrices between predictions on unlabeled samples and select submatrices with maximal determinant [18].

FAQ 4: How does selective safety data collection (SSDC) relate to Active Learning in clinical development?

Selective Safety Data Collection represents a regulatory-approved application of selective data acquisition principles in late-stage clinical trials [21] [22]. For drugs with well-characterized safety profiles, SSDC implements a planned reduction in collecting certain types of routine safety data (common, non-serious adverse events) unlikely to provide additional clinically important knowledge [22]. This approach reduces participant burden, slashes study costs, and facilitates trial conduct while maintaining patient safety standards [22]. The framework demonstrates how selective data collection principles can be successfully applied across the drug development continuum, from early discovery to clinical trials.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor Generalization of Property Predictors

Symptoms: Generated molecules show artificially high predicted probabilities but fail experimental validation; significant discrepancy between predicted and actual property values [20].

Solutions:

- Implement Expected Predictive Information Gain (EPIG): Use this acquisition criterion to select molecules that provide the greatest reduction in predictive uncertainty, enabling more accurate model evaluations of subsequently generated molecules [20].

- Increase Human Expert Involvement: Leverage domain knowledge to confirm or refute property predictions, specifying confidence levels to allow for cautious predictor refinement [20].

- Expand Chemical Space Coverage: Intentionally generate molecules in poorly understood regions of chemical space to enhance model applicability domain [20].

Prevention: Regularly monitor model generalization performance during deployment and implement continuous AL cycles rather than single-round optimization [20].

Problem: Suboptimal Batch Selection in Active Learning Cycles

Symptoms: Slow model improvement despite multiple AL cycles; redundant information in selected batches; diminishing returns with additional data [18].

Solutions:

- Adopt Advanced Batch Selection Methods: Implement COVDROP or COVLAP approaches that use Monte Carlo dropout or Laplace approximation to compute covariance matrices between predictions [18].

- Maximize Joint Entropy: Select batches that maximize the log-determinant of the epistemic covariance of batch predictions, which enforces diversity by rejecting highly correlated batches [18].

- Balance Exploration and Exploitation: Ensure batch selection criteria balance between exploring diverse chemical space and exploiting similarity to existing training data [20].

Prevention: Establish appropriate batch sizes (typically 30 compounds) and use greedy approximation methods to optimally select samples that maximize the likelihood of model parameters [18].

Problem: Inefficient Resource Allocation in Experimental Cycles

Symptoms: High costs per informative compound; excessive wet-lab experimentation; prolonged discovery cycles [20] [18].

Solutions:

- Implement Tiered Validation: Use computational pre-screening followed by human expert review before wet-lab experimentation [20].

- Leverage Public Datasets: Incorporate diverse public data sources (e.g., ChEMBL, TCGA, dbSNP) for initial model training before targeted AL [23].

- Adopt Appropriate Acquisition Functions: Choose acquisition criteria based on specific optimization goals (see Table 1) [20] [18].

Prevention: Conduct retrospective analysis using existing datasets to optimize AL parameters before initiating new experimental campaigns [18].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Human-in-the-Loop Active Learning for Molecular Optimization

This protocol enables iterative refinement of property predictors through human expert feedback [20].

Step 1: Initial Model Training

- Train initial property predictors (QSPR/QSAR models) on available experimental data 𝒟₀ = {(xᵢ, yᵢ)}ᵢ=1^N⁰

- Use D-dimensional count fingerprints for molecule representation

- Implement appropriate neural network architectures (e.g., graph neural networks) [18]

Step 2: Goal-Oriented Molecule Generation

- Frame generation as multi-objective optimization maximizing scoring function: s(𝐱) = Σⱼ wⱼσⱼ(φⱼ(𝐱)) + Σₖ wₖσₖ(f𝛉ₖ(𝐱)) [20]

- Use transformation functions σ to map evaluation functions to [0,1]

- Normalize weights w to facilitate interpretation of overall score [20]

Step 3: Human Expert Evaluation

- Present generated molecules to chemistry experts for evaluation

- Experts confirm or refute property predictions using standardized interface

- Collect confidence levels for each assessment [20]

Step 4: Model Refinement

- Incorporate expert-validated molecules as additional training data

- Retrain property predictors using expanded dataset

- Repeat cycle until desired performance achieved [20]

Protocol: Batch Active Learning for ADMET Optimization

This protocol details batch AL implementation for drug property optimization [18].

Step 1: Uncertainty Estimation

- Use multiple methods to compute covariance matrix C between predictions on unlabeled samples 𝒱

- Apply MC dropout or Laplace approximation for uncertainty quantification [18]

Step 2: Batch Selection

- Employ iterative greedy approach to select submatrix Cᴮ of size B×B from C with maximal determinant

- Balance uncertainty (variance of each sample) and diversity (covariance between samples) [18]

Step 3: Experimental Testing

- Conduct appropriate assays for target properties (e.g., solubility, permeability, affinity)

- Ensure consistent experimental conditions across batches [18]

Step 4: Model Update

- Incorporate new experimental results into training data

- Retrain models and reassess performance metrics

- Continue until model performance plateaus or resource limits reached [18]

Data Presentation: Performance Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of Acquisition Functions for Active Learning in Drug Discovery

| Acquisition Function | Key Principle | Best For | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Predictive Information Gain (EPIG) | Selects molecules that maximize reduction in predictive uncertainty [20] | Goal-oriented generation with limited data | Improved alignment of predicted and actual properties [20] |

| COVDROP | Uses Monte Carlo dropout to compute covariance matrices for batch selection [18] | ADMET optimization with neural networks | Fast convergence; best overall performance on solubility and permeability datasets [18] |

| COVLAP | Uses Laplace approximation for uncertainty estimation [18] | Affinity prediction tasks | Superior performance on affinity datasets; effective with graph neural networks [18] |

| BAIT | Uses Fisher information for optimal sample selection [18] | Traditional machine learning models | Good performance but less effective with advanced neural networks [18] |

| k-Means | Selects diverse samples based on chemical space clustering [18] | Initial exploration of chemical space | Moderate performance; useful for initial model training [18] |

Table 2: Active Learning Performance Benchmarks Across Dataset Types

| Dataset Type | Dataset Size | Best Method | Performance Gain vs. Random | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | 9,982 compounds [18] | COVDROP | ~40% reduction in RMSE [18] | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

| Cell Permeability (Caco-2) | 906 drugs [18] | COVDROP | ~35% reduction in RMSE [18] | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

| Lipophilicity | 1,200 compounds [18] | COVLAP | ~30% reduction in RMSE [18] | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

| Affinity Datasets | 10 datasets (ChEMBL + internal) [18] | COVLAP | ~50% reduction in experiments needed [18] | Early enrichment factor |

| DRD2 Bioactivity | Limited data scenario [20] | HITL-EPIG | 6x improvement in hit discovery [19] | Hit rate vs. traditional screening |

Workflow Visualization

Active Learning Loop Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Active Learning in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepChem | Open-source library | Deep learning for drug discovery [18] | General-purpose molecular property prediction |

| GeneDisco | Benchmarking library | Evaluation of active learning algorithms [18] | Transcriptomics and chemical perturbation studies |

| ChEMBL | Public database | Bioactivity data for small molecules [18] | Initial model training and benchmarking |

| MC Dropout | Uncertainty estimation technique | Approximate Bayesian inference in neural networks [18] | Uncertainty quantification for COVDROP method |

| Laplace Approximation | Uncertainty estimation technique | Approximate Bayesian inference [18] | Uncertainty quantification for COVLAP method |

| Metis User Interface | Human-in-the-loop platform | Expert feedback collection for molecular properties [20] | Human-in-the-loop active learning implementations |

| TCGA | Public database | Genomics and functional genomics data [23] | Target identification and disease understanding |

| dbSNP | Public database | Single nucleotide polymorphisms [23] | Genetic variation analysis for personalized medicine |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is active learning and how does it specifically reduce labeling costs in molecular science? Active learning (AL) is a machine learning paradigm that iteratively selects the most informative data points from a large unlabeled pool for expert annotation. By targeting samples that are most uncertain or expected to maximize model improvement, it avoids the cost of labeling entire datasets. In molecular science, this has been shown to reduce the number of training molecules required by about 57% for mutagenicity prediction and achieve baseline model performance with only 15%-50% of the nanopore data needing labels, leading to massive savings in time and resources [24] [25].

Q2: My dataset is very small. Can active learning still be effective? Yes, active learning is particularly powerful for small data challenges. It is designed to start from a minimal set of labeled data and efficiently expand it. For instance, one study successfully explored a virtual search space of one million potential battery electrolytes starting from just 58 initial data points [6]. The key is the iterative process of training a model, using it to query the most valuable new data, and then retraining.

Q3: What are the most common model training errors encountered when implementing an active learning loop? Common errors include [26] [27] [28]:

- Data Leakage: When information from the test set leaks into the training process, leading to overly optimistic performance. This must be avoided by performing all preprocessing (like imputation and scaling) after splitting the data and using pipelines.

- Overfitting and Underfitting: Overfitting occurs when the model learns the training data too well, including its noise, and fails to generalize. Underfitting happens when the model is too simple to capture the underlying trends.

- Data Imbalance: When one class of data is underrepresented, the model becomes biased toward the majority class. Techniques like auditing for bias and using appropriate performance metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) are crucial.

Q4: How do I handle complex, noisy data like nanopore sequencing signals in active learning? For complex data with inherent noise, standard query strategies can be improved. One effective approach is to introduce a bias constraint into the sample selection strategy. This helps the model focus on informative samples while accounting for the confounding presence of noise sequences, leading to more robust learning [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance Despite Active Learning

Problem: Your active learning model is not achieving expected performance gains with each new batch of labeled data.

Solution:

- Step 1 - Verify the Query Strategy: Ensure you are using an appropriate strategy for your data. Uncertainty sampling (e.g., selecting samples where the model's prediction confidence is lowest) is a common and effective approach. Other strategies include diversity sampling to ensure selected samples represent different areas of the chemical space [25] [29].

- Step 2 - Check for Data Preprocessing Issues:

- Handle Missing Values: Impute missing values using the mean, median, or mode, but ensure the imputers are fit only on the training data to prevent data leakage [27].

- Scale Numeric Features: Use StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler to ensure all features are on a similar scale [27].

- Address Data Imbalance: Use tools like IBM’s AI Fairness 360 to audit for bias. If imbalance is detected, consider oversampling the minority class or undersampling the majority class in the training set [26].

- Step 3 - Re-examine the Initial Data: The initial small set of labeled data must be representative of the broader chemical space. If it is not, the active learner may struggle to query useful samples. A random, stratified selection is often a safe choice [29].

Issue 2: The "Cold Start" Problem with Minimal Initial Data

Problem: It is challenging to train a useful initial model when you have very few labeled samples to start the active learning cycle.

Solution:

- Step 1 - Leverage Data Augmentation: Create synthetic data points based on your existing labeled data. In molecular science, this can be done through physical model-based data augmentation or other techniques that generate valid, new molecular representations [30].

- Step 2 - Utilize Transfer Learning: If available, start with a model pre-trained on a related, larger dataset from a public database. Fine-tune this model on your small initial dataset. This provides a much stronger starting point for the active learning algorithm [30].

- Step 3 - Implement an Ensemble for Uncertainty: When using models that lack intrinsic uncertainty estimation (like many neural networks), use an ensemble of models. The disagreement among the models on a given sample is a powerful proxy for uncertainty and can guide the query strategy effectively [31].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic Active Learning Cycle for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the core iterative process for applying active learning, as used in mutagenicity prediction [25] and electrolyte screening [6].

- Initialization: Start with a small, randomly selected set of labeled molecules (e.g., 200 compounds). The remaining molecules constitute the large unlabeled pool.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., a deep neural network, random forest, or support vector machine) on the current labeled set.

- Uncertainty Scoring: Use the trained model to predict on the entire unlabeled pool. Calculate an uncertainty score for each unlabeled sample (e.g., using margin sampling, entropy, or ensemble disagreement).

- Querying: Select the top k molecules with the highest uncertainty scores.

- Oracle Labeling: Send the selected molecules to the "oracle" (e.g., a wet lab for an Ames test or an expert chemist) for labeling.

- Dataset Update: Add the newly labeled molecules to the training set and remove them from the unlabeled pool.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-6 until a performance plateau is reached or the annotation budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

This specialized protocol, used for predicting IR spectra, details how active learning guides data generation for computationally expensive simulations [31].

- Initial Data Generation: Generate an initial training set by sampling molecular geometries along their normal vibrational modes from DFT calculations.

- Initial MLIP Training: Train an initial MLIP (e.g., an ensemble of MACE models) on this small dataset.

- Active Learning Loop:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Run machine learning-assisted MD (MLMD) simulations at different temperatures (e.g., 300 K, 500 K, 700 K) to explore the configurational space.

- Uncertainty Acquisition: From the MD trajectories, select molecular configurations where the MLIP ensemble shows the highest uncertainty in its force predictions.

- DFT Calculation: Perform accurate DFT calculations on the selected configurations to obtain ground-truth energies and forces.

- Data Augmentation: Add these new high-quality, informative data points to the training set.

- Model Retraining: Retrain the MLIP on the expanded dataset.

- Convergence Check: Repeat the loop until the MLIP's accuracy on a separate test set of harmonic frequencies converges.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the demonstrated effectiveness of active learning in reducing data labeling costs across various chemical and biological applications.

Table 1: Labeling Efficiency of Active Learning in Different Studies

| Application Domain | Baseline Labeling Requirement | Active Learning Requirement | Performance Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenicity Prediction (muTOX-AL) [25] | Not specified | ~57% fewer training samples | Achieved similar testing accuracy as a model trained with a full dataset |

| Nanopore RNA Classification [24] | 100% of dataset | ~15% of dataset | Achieved the best baseline performance |

| Nanopore Barcode Classification [24] | 100% of dataset | ~50% of dataset | Achieved the best baseline performance |

| Electrolyte Solvent Screening [6] | Infeasible to test 1M compounds | Started with 58 data points | Identified four high-performing electrolytes |

Table 2: Common Model Training Errors and Solutions

| Training Error | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Leakage [26] [27] | Information from the test set influences the training process, causing inflated performance metrics. | Split data into train/test sets first. Use scikit-learn Pipelines to encapsulate all preprocessing steps fitted only on training data. |

| Overfitting [26] | Model learns training data too well, including noise, and performs poorly on new data. | Apply regularization, reduce model complexity (fewer layers/parameters), and use cross-validation. |

| Data Imbalance [26] | Model becomes biased towards the majority class because one class is underrepresented. | Use metrics like precision/recall/F1-score. Employ auditing tools (e.g., AI Fairness 360). Consider resampling techniques. |

| Insufficient Feature Engineering [27] | Model fails to capture key relationships because features are not optimally represented. | Use domain knowledge to create new features (e.g., interaction features, aggregated features). |

Workflow Diagrams

Core Active Learning Workflow

Bias-Aware Sampling for Noisy Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Active Learning in Molecular Science

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| AL for nanopore [24] | An active learning program specifically for analyzing high-throughput nanopore sequencing data. | Reduces the cost of labeling complex nanopore data for RNA classification and barcode analysis. |

| PALIRS (Python-based Active Learning Code for IR Spectroscopy) [31] | An active learning framework for efficiently training machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to predict IR spectra. | Accelerates the prediction of IR spectra for catalytic organic molecules by reducing the need for costly DFT calculations. |

| muTOX-AL [25] | A deep active learning framework for molecular mutagenicity prediction. | Significantly reduces the number of molecules that require experimental mutagenicity testing (e.g., Ames test). |

| TOXRIC Database [25] | A public database of toxic compounds with mutagenicity labels. | Serves as a benchmark dataset for training and validating predictive models in toxicology. |

| scikit-learn [27] | A popular Python library for machine learning. | Provides tools for building models, creating pipelines to avoid data leakage, and preprocessing data. |

| Uncertainty Estimation Ensemble [31] | A technique using multiple models to estimate prediction uncertainty. | Used in MLIP training to identify which molecular configurations the model is most uncertain about, guiding the active learning query. |

Advanced AL Frameworks and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

Integrating AL with Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) for Robust Model Selection

FAQs: Core Concepts

Q1: What is the primary benefit of integrating Active Learning (AL) with AutoML in chemical space research?

This integration addresses the critical challenge of data scarcity for novel chemical compounds. It creates a highly efficient, closed-loop system where AutoML rapidly identifies promising model pipelines, and AL strategically selects the most informative data points from the vast chemical space for experimental testing. This minimizes costly and time-consuming lab experiments, accelerating the discovery of new materials and drugs [6] [31].

Q2: How does the AL component decide which chemical compounds to test experimentally?

The AL component acts as an intelligent sampling strategy. It prioritizes compounds from the virtual chemical space where the current machine learning model is most uncertain or where the potential for performance improvement is the highest. In practice, this often means running molecular dynamics simulations, querying the model on new configurations, and selecting those with the highest predictive uncertainty for subsequent DFT validation and inclusion in the training set [31].

Q3: Our AutoML models are not converging well during the active learning cycles. What could be wrong?

Poor convergence can often be traced to the initial training set being too small or non-representative. The system lacks a foundational understanding of the chemical space. Furthermore, the acquisition function in the AL loop might be too exploitative, failing to explore diverse regions. Ensure your initial dataset, though small, covers a diverse set of molecular scaffolds and that your AL strategy balances exploration (testing novel structures) with exploitation (refining around promising candidates) [6] [31].

Q4: Can this integrated approach work with different types of chemical data?

Yes. The framework is versatile and has been successfully applied to various data types and prediction targets in computational chemistry. This includes predicting battery electrolyte performance [6], infrared (IR) spectra of organic molecules [31], and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties for drug candidates [32] [33]. The core principle of iterative model refinement and data selection remains consistent across these applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Model Uncertainty Stagnates After Initial AL Cycles

Problem: The average uncertainty of the model on new, unseen chemical compounds stops decreasing after the first few rounds of active learning, suggesting the system is no longer learning effectively.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diversify Initial Data: Check if the initial seed data has sufficient structural diversity. Incorporate molecules from different chemical classes, even with estimated properties, to provide a broader foundational model. | A more robust initial model that generalizes better to unexplored regions of chemical space. |

| 2 | Adjust AL Query Strategy: Switch from a pure uncertainty sampling to a hybrid strategy. Combine uncertainty with diversity metrics (e.g., Maximal Marginal Relevance) to select a batch of compounds that are both informative and structurally distinct from each other. | Prevents the AL loop from getting stuck in a local region and promotes exploration of the global chemical space. |

| 3 | Review AutoML Search Space: Ensure the AutoML system is configured to explore a wide range of model types and hyperparameters. An overly restricted search space may fail to find a model architecture capable of capturing complex, newly discovered structure-property relationships. | Enables the discovery of more powerful and adaptable models as new data is introduced. |

Issue 2: Prohibitive Computational Cost of Data Generation

Problem: The quantum mechanics calculations (e.g., Density Functional Theory) used to validate the AL-selected compounds are too slow, creating a bottleneck in the iterative loop.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Implement Multi-Fidelity Learning: Use faster, lower-fidelity computational methods (e.g., semi-empirical methods, molecular mechanics) to pre-screen a larger number of AL suggestions. Reserve high-fidelity DFT calculations only for the most promising candidates that pass the initial filter. | Dramatically reduces the wall-clock time per active learning cycle. |

| 2 | Leverage Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs): Train MLIPs on-the-fly using the data generated from high-fidelity calculations. These MLIPs can approximate energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost, significantly accelerating molecular dynamics simulations used in the AL process [31]. | Enables much larger and longer simulations for sampling configurations, leading to more robust uncertainty estimates. |

Issue 3: The Integrated Pipeline Fails to Discover Novel High-Performing Compounds

Problem: The system keeps proposing variations of known compounds but fails to make "leaps" to truly novel and high-performing chemical scaffolds.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Incentivize Novelty in Acquisition: Modify the AL acquisition function to include an explicit term for "novelty" or "surprise," measured by the distance of a proposed compound from the existing training set in a relevant molecular descriptor space. | Guides the search towards completely unexplored and potentially fruitful regions of the chemical universe. |

| 2 | Incorporate Generative Models: Introduce a generative model (e.g., a Generative Adversarial Network or a Variational Autoencoder) into the loop. This model can propose entirely new, synthetically accessible molecules from scratch, which the AL model can then evaluate and prioritize for testing [6]. | Unlocks the potential for discovering fundamentally new molecular entities not present in any starting database. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an AL-AutoML Workflow for IR Spectrum Prediction

This protocol is based on the PALIRS framework for predicting the infrared spectra of organic molecules, a key task in catalytic research [31].

1. Initial Data Curation and Model Setup

- Molecule Selection: Start with a set of 20-30 small, catalytically relevant organic molecules that represent the chemical space of interest.

- Initial Sampling: For each molecule, sample molecular geometries along their normal vibrational modes derived from DFT calculations. This initial dataset typically contains ~2000-3000 structures.

- AutoML Configuration: Configure the AutoML system (e.g., DeepMol [33]) to search for optimal model pipelines. The search space should include:

- Featureization: A variety of molecular descriptors (e.g., Mordred, MACCS keys) and fingerprints (e.g., ECFP).

- Models: A range of algorithms from random forests to gradient boosting and neural networks.

- Hyperparameters: A wide search space for learning rates, tree depths, etc., optimized using methods like Bayesian optimization.

2. Active Learning Loop

- Step 1 - MLMD Simulation: Use the current best MLIP from AutoML to run machine learning-assisted molecular dynamics (MLMD) simulations at multiple temperatures (e.g., 300 K, 500 K, 700 K) to explore different conformational states.

- Step 2 - Uncertainty Estimation: For all sampled molecular configurations, predict energies and forces. Use an ensemble of models or a model with intrinsic uncertainty quantification to estimate the uncertainty (e.g., standard deviation across the ensemble) for each prediction.

- Step 3 - Acquisition: Select the top N molecular configurations (e.g., 100-200 per cycle) with the highest uncertainty in their force predictions.

- Step 4 - High-Fidelity Validation: Perform accurate DFT calculations on the acquired configurations to obtain ground-truth energies and forces.

- Step 5 - Model Retraining: Add the newly acquired data (configurations and their DFT-validated properties) to the training set. Retrain or hyperparameter-tune the MLIP using the AutoML system.

3. Convergence and Spectra Calculation

- Iterate Steps 1-5 for ~40 cycles or until the model's accuracy on a separate test set of harmonic frequencies plateaus.

- Once a final MLIP is obtained, train a separate dipole moment model on the acquired dataset.

- Run a final, long MLMD production simulation and use the dipole moment model to calculate the dipole autocorrelation function, which is then converted into the final IR spectrum.

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Resource | Function in the AL-AutoML Pipeline |

|---|---|

| PALIRS (Python Active Learning for IR Spectroscopy) | An open-source software package that implements the active learning framework for training machine-learned interatomic potentials specifically for predicting IR spectra [31]. |

| DeepMol | An Automated ML (AutoML) framework specifically designed for computational chemistry. It automates data preprocessing, feature engineering, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning for molecular property prediction [33]. |

| FHI-aims | An all-electron, full-potential electronic structure code based on numeric atom-centered orbitals. It is used for the high-fidelity DFT calculations that provide the ground-truth data for training and validating the ML models in the workflow [31]. |

| MACE (Multipolar Atomic Cluster Expansion) | A state-of-the-art machine-learned interatomic potential model. It is used in PALIRS to represent the potential energy surface, providing accurate energies and forces for molecular dynamics simulations [31]. |

| Hyperopt-sklearn | An AutoML library that automatically searches over a space of scikit-learn classification algorithms and their hyperparameters. It can be used for the classical ML components within the broader pipeline, such as predicting ADMET properties [32]. |

Uncertainty-Driven Strategies for Virtual Screening of On-Demand Chemical Libraries

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using active learning for virtual screening?

Active learning addresses several key bottlenecks in virtual screening. It significantly reduces the computational cost of screening ultralarge, make-on-demand chemical libraries, which can contain billions of compounds and are too large for traditional docking methods [34]. Furthermore, it minimizes the number of experimental data points required to build an effective model. In some cases, research has shown it is possible to explore a virtual search space of one million potential molecules starting from just 58 initial data points [6]. This approach also helps reduce human bias by allowing the algorithm to explore chemical spaces a researcher might not initially consider [6].

Q2: My active learning model seems to have converged on poor-performing compounds. How can I improve its exploration of the chemical space?

This is a common challenge known as getting stuck in a local optimum. You can improve exploration by:

- Increasing Temperature in MD Simulations: Running machine learning-assisted molecular dynamics (MLMD) simulations at higher temperatures (e.g., 500 K or 700 K) can help the model explore a wider range of molecular configurations and escape low-energy basins [31].

- Incorporate Diverse Selection Criteria: Instead of selecting compounds based solely on the highest uncertainty, use a hybrid approach that also prioritizes compounds for their diversity or based on structural features that are underrepresented in your current training set [35].

- Validate with Experimental Outputs: To ensure computational predictions align with real-world performance, "bite the bullet and go all the way to experiments as a final output" [6]. Use the results from these wet-lab experiments to refine the model and correct its course.

Q3: How can I effectively screen a multi-billion compound library within a practical timeframe?

A proven strategy is to use a multi-stage filtering workflow that combines machine learning and molecular docking [34].

- Initial Machine Learning Filter: First, train a classification algorithm (like a CatBoost classifier) on a smaller, docked subset of the library (e.g., one million compounds). The model learns to identify top-scoring compounds.

- Conformal Prediction: Use this trained model and a conformal prediction framework to select the most promising candidates from the multi-billion-scale library. This step drastically reduces the number of compounds that need to be processed by the more computationally expensive docking algorithm.

- Final Docking Screen: Perform molecular docking only on the greatly reduced, pre-filtered compound set. This workflow has been shown to identify over 90% of the top-scoring molecules while only requiring docking of 3-5% of a 200-million-compound library [34].

Q4: What are the key criteria for selecting compounds for experimental validation in an active learning cycle?

The selection should be a balanced strategy based on multiple factors, which can be quantified and prioritized. The following table summarizes the core criteria:

| Criterion | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High Uncertainty | Selects compounds where the model's prediction has the highest uncertainty [31] [35]. | Improves the model by teaching it about the areas where it is least knowledgeable. |

| High Predicted Score | Selects compounds predicted to have the best docking scores or binding affinity [34]. | Exploits the current model to find the most promising hits. |

| Diversity | Prioritizes compounds that are structurally different from those already in the training set [35]. | Ensures broad exploration of chemical space and prevents over-concentration in one region. |

| Multi-objective Potential | Considers other properties like solubility, synthetic accessibility, or lack of toxicophores. | Identifies candidates that are not just active, but also have drug-like properties, saving downstream resources [6]. |

Q5: How do I know if my Machine-Learned Interatomic Potential (MLIP) is accurate enough for reliable virtual screening?

The accuracy of an MLIP should be quantitatively assessed against a predefined test set. For virtual screening applications related to molecular binding, key metrics and methods include:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Calculate the MAE of harmonic frequencies or energies between your MLIP and DFT reference calculations on a validation set of molecules. A low MAE indicates high accuracy [31].

- Benchmarking on Known Systems: Test your trained MLIP on a small set of molecules with known experimental results or high-fidelity simulation data (e.g., from AIMD). Compare the predicted IR spectra or binding energies to these references to validate the model's performance [31].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use an ensemble of models to estimate the uncertainty of predictions. High uncertainty in a region of chemical space signals that the model may be unreliable there and needs more training data [31].

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem 1: Handling Noisy or Unreliable Experimental Data

Issue: Experimental data used to train or validate the active learning model is inconsistent, leading to poor model performance and generalization.

Solution: Implement robust data preprocessing and quality control protocols.

- Standardize Data Collection: Use a single, well-defined set of reaction conditions for high-throughput experimentation (HTE) to minimize confounding variables [35].

- Employ Accurate Quantification: For yield validation, use precise methods like Ultra-High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography with Charged Aerosol Detection (UPLC-CAD) and generate calibration curves with structurally similar compounds to improve accuracy [35]. For binding assays, use standardized positive and negative controls.

- Data Curation: Clean the training data by removing duplicates, correcting errors, and standardizing formats (e.g., using tools like RDKit) [36]. Be prepared to exclude data points from failed or ambiguous experiments [35].

### Problem 2: High Computational Cost of Data Generation for MLIPs

Issue: Generating sufficient high-quality quantum mechanical data (e.g., from DFT calculations) to train a Machine-Learned Interatomic Potential is computationally prohibitive.

Solution: Implement an active learning framework specifically for efficient dataset construction.

- Initial Sampling: Start with a small initial dataset sampled from normal vibrational modes of your target molecules [31].

- Iterative Active Learning: Use the following workflow to iteratively and efficiently build your training set. The core of this method is a cycle that uses uncertainty to guide the selection of new data points, maximizing the value of each computation.

This active learning process for building an MLIP has been shown to accurately reproduce IR spectra at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional methods, creating a high-quality dataset with minimal redundancy [31].

### Problem 3: Model Failure on Novel Chemical Scaffolds

Issue: The model performs well on its training data but fails to generalize to new, structurally distinct compounds (e.g., new aryl bromide cores in cross-coupling reactions [35]).

Solution: Proactively plan for model expansion and use descriptive features.

- Featurization with DFT: Use Density Functional Theory (DFT) to calculate mechanism-relevant features (e.g., LUMO energy) for your compounds. These features often provide a more generalizable representation than simple molecular fingerprints alone [35].

- Cluster Your Chemical Space: Use techniques like UMAP for dimensionality reduction and hierarchical clustering to map your virtual chemical space. This helps you visualize and understand the diversity of your compound library [35].

- Targeted Expansion: When expanding to new chemical regions (e.g., new aryl bromides), select a minimal set of representative compounds from the new clusters. Running a small, targeted HTE campaign (e.g., <100 additional reactions) on these representatives can efficiently extend your model's capabilities into the new space [35].

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental resources essential for implementing uncertainty-driven virtual screening workflows.

| Tool / Resource | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Public Chemical Databases (e.g., PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL) [37] | Provide diverse chemical structures and biological activity data for initial model building and library sourcing. |

| Make-on-Demand Libraries (e.g., Enamine, over 75 billion compounds) [36] | Ultralarge virtual chemical libraries that can be synthesized and delivered for experimental validation. |

| RDKit [36] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for manipulating molecules, calculating molecular descriptors, and similarity analysis. |

| Active Learning Software (e.g., PALIRS [31]) | Specialized frameworks for implementing active learning cycles to efficiently build training datasets for machine learning models. |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) (e.g., MACE [31]) | ML models trained on quantum mechanical data that enable highly accelerated molecular dynamics simulations for property prediction. |

| Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock, Glide) [38] [34] | Perform structure-based virtual screening by predicting how small molecules bind to a protein target. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [35] | An automated platform for rapidly testing hundreds or thousands of chemical reactions to generate experimental data for model training and validation. |

The COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent, global need for effective antiviral therapeutics, pushing the drug discovery community to innovate and accelerate traditional development timelines. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) emerged as a primary drug target because it is essential for viral replication; inhibiting this enzyme effectively halts the virus's life cycle [39] [40]. This case study examines how Active Learning (AL) was integrated into the drug discovery workflow to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space and identify promising Mpro inhibitors.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Hit Rate in Virtual Screening

- Symptoms: A high proportion of computationally selected drug candidates show no inhibitory activity during experimental validation.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Use of traditional computational methods (e.g., simple molecular docking) that poorly predict binding affinities and generate many false positives [39].

- Solution: Implement a more rigorous free energy perturbation-based absolute binding free energy (FEP-ABFE) prediction method. This approach significantly improves hit rates. One study achieved a 60% success rate (15 out of 25 predicted drugs were confirmed potent inhibitors) by using this method [39].

- Cause: Screening compounds that are not optimized for the specific target's active site.

- Solution: Prioritize compounds that form specific interactions with key amino acid residues in the Mpro binding site, such as Cys145, His41, and His163 [39] [41].

Problem 2: Model Inaccuracy with Minimal Data

- Symptoms: An AI model makes poor predictions and suggests non-viable candidates, especially when trained on a small dataset.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: High prediction uncertainty when the model extrapolates too far from its initial training data [6].

- Solution: Integrate an active learning cycle where the model's most uncertain predictions are validated through experiment. The results are then fed back into the model for retraining, creating a iterative loop that improves accuracy with each cycle [6]. This "trust but verify" approach was key to finding promising battery electrolytes from a space of one million candidates starting with just 58 data points [6].

- Cause: The model is trained on computational proxies that do not correlate well with real-world experimental outcomes.

- Solution: Use real-world experimental data (e.g., antiviral activity assays) as the primary output for validating the AI's suggestions, ensuring the model learns from biologically relevant results [6].

Problem 3: Loss of Antiviral Potency in Cellular Assays

- Symptoms: A compound shows excellent potency against the purified Mpro enzyme but loses effectiveness in cellular infection models.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The compound may be inhibiting host cell proteases (e.g., cathepsins B and L) instead of, or in addition to, the viral Mpro. This is a common off-target effect [42].

- Solution: Conduct thorough selectivity profiling early in the discovery process. Test lead molecules against a panel of human proteases, particularly cathepsins, to identify and eliminate non-selective compounds [42].

- Cause: Redundant viral entry pathways. If the virus can use an alternative pathway (e.g., TMPRSS2) that bypasses the cathepsin-dependent pathway, the antiviral effect of a cathepsin-inhibiting compound will be lost [42].

- Solution: Evaluate antiviral activity in cell lines that express different entry pathways (e.g., with and without TMPRSS2 expression) to understand the true mechanism of action [42].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is SARS-CoV-2 Mpro considered a good drug target? A1: Mpro is an excellent target for several reasons. It is essential for processing the viral polyprotein, a critical step in viral replication. Its substrate specificity is distinct from human proteases, reducing the likelihood of off-target effects. Furthermore, it is highly conserved across coronavirus variants, making inhibitors potentially broad-spectrum [39] [40].

Q2: What is the role of Active Learning in this context? A2: Active Learning is a machine learning paradigm where the algorithm strategically selects the most informative data points for experimental testing. Instead of testing compounds randomly, an AL model prioritizes candidates based on high prediction uncertainty or high potential to meet the target profile. This creates a closed-loop system that maximizes the informational gain from each experiment, dramatically accelerating the exploration of massive chemical spaces with minimal data [6] [14].

Q3: What are the key properties of a successful Mpro inhibitor? A3: A successful inhibitor must have:

- High Binding Affinity: Strong, often covalent, interaction with the catalytic cysteine (Cys145) of Mpro [42] [41].

- Favorable Pharmacokinetics: Good absorption, distribution, and metabolic properties, often predicted by ADMET analysis [41].

- Selectivity: Does not significantly inhibit key human proteases like cathepsin L [42].

- Antiviral Efficacy: Demonstrates potent inhibition of viral replication in cellular assays [39] [40].

Q4: Our initial model performance is poor. How can we improve it without a large dataset? A4: This is a classic challenge that AL is designed to address. Implement an uncertainty-based acquisition strategy. Start by training an initial model on your small dataset, then use it to screen a large virtual library. Instead of picking the top predictions, select a batch of candidates where the model is most uncertain and test those. Add this new, high-value data to your training set and retrain the model. This iterative process efficiently targets the model's weaknesses and improves its accuracy with far fewer data points than traditional methods [6] [31] [14].

Table 1: Success Rates of Different Virtual Screening Approaches for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

| Screening Method | Number of Compounds Tested | Number of Potent Inhibitors Identified | Hit Rate | Most Potent Inhibitor (Ki) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP-ABFE-Based Screening | 25 | 15 | 60% | Dipyridamole (0.04 µM) | [39] |

| Traditional Virtual Screening (for reference) | 590 (for KEAP1 target) | 69 (binders) | ~11.7% | N/A | [39] |

Table 2: Key Pharmacokinetic and Safety Profile of a Promising Computationally Identified Mpro Inhibitor

| Property | Value for Compound 4896-4038 | Implication for Drug Development | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 491.06 | Within acceptable range for drug-likeness | |

| Lipophilicity (LogP) | 3.957 | Favorable for membrane permeability | |

| Intestinal Absorption | 92.119% | High, indicates good oral bioavailability | |

| Volume of Distribution (VDss) | 0.529 | Suggests broad tissue distribution | |

| Binding Affinity | Comparable to reference inhibitor X77 | Indicates strong potential efficacy | [41] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: FEP-ABFE-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the methodology for achieving high-hit-rate virtual screening [39].

- Library Preparation: Compile a library of existing drugs or lead-like compounds.

- Molecular Docking: Dock all compounds into the binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro crystal structure (e.g., PDB ID: 6W63). Filter for compounds that interact with key residues (Cys145, His41, Ser144, His163, Gly143, Gln166).

- Grouping by Charge: Separate the top docking hits into groups based on their net charge (neutral, +1, -1) to manage systematic errors in subsequent FEP calculations.

- FEP-ABFE Calculation: Perform accelerated Free Energy Perturbation calculations to determine the Absolute Binding Free Energy for each compound. This step uses a Restraint Energy Distribution (RED) function to improve computational efficiency.

- Selection for Experimental Validation: Within each charge group, select the top 20-40% of compounds with the most favorable (lowest) binding free energies for in vitro testing.

Protocol: Integrated Active Learning Workflow for Inhibitor Discovery

This protocol synthesizes AL approaches from related fields for application in antiviral discovery [6] [31] [14].

- Initial Dataset Curation: Assemble a small, diverse set of molecules with known experimental outcomes (e.g., inhibitory activity, Ki values).

- Surrogate Model Training: Train an initial machine learning model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on this dataset to predict the desired property (e.g., binding affinity).

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use an ensemble of models or a model with intrinsic uncertainty estimation to predict properties and uncertainties for a large virtual chemical library.

- Informed Candidate Selection: Employ an acquisition function (e.g., uncertainty-based, diversity-based, or expected improvement) to select the most informative batch of candidates from the virtual library.

- High-Fidelity Validation: Subject the selected candidates to experimental validation (e.g., enzymatic assays, antiviral activity tests).

- Iterative Model Refinement: Add the new experimental data to the training set and retrain the surrogate model. Repeat steps 3-6 until a satisfactory candidate is identified or resources are exhausted.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Active Learning-Driven Drug Discovery

Experimental Validation Funnel

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Mpro Inhibitor Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | Target protein for in vitro enzymatic activity assays to measure direct inhibition. | Ensure high purity and correct dimeric form for accurate activity measurements. |

| Fluorogenic Mpro Substrate | Peptide substrate with a fluorophore/quencher pair. Cleavage by Mpro generates a fluorescent signal to quantify enzyme activity. | Use extended substrates that include prime-side residues for higher catalytic turnover and assay sensitivity [42]. |

| Cell Lines with Varying TMPRSS2 Expression | Cellular models for antiviral efficacy testing (e.g., A549 lung epithelial cells with/without TMPRSS2 expression). | Critical for identifying compounds whose antiviral activity is due to off-target cathepsin inhibition rather than Mpro inhibition [42]. |

| Selective Cathepsin Inhibitors (e.g., E64d) | Control compounds to validate the selectivity of Mpro inhibitors and understand viral entry pathways. | Helps distinguish the mechanism of action in cellular assays [42]. |

| Crystallographic Mpro Structure (PDB: 6W63) | Template for molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and structure-based drug design. | Essential for understanding ligand-protein interactions and guiding lead optimization [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My molecular property predictions have high variance. How can I improve model stability? A: High variance often stems from inadequate sampling of chemical space. Implement an Active Learning loop where your model iteratively queries a QM calculation for the most uncertain data points from a larger, unlabeled molecular dataset. This targets QM computations to the most informative regions, improving stability and performance with fewer calculations [43].

Q: The computational cost of my QM/ML pipeline is too high. What can I optimize? A: Focus on your feature representation. High-dimensional QM-derived features are computationally expensive. Use feature selection or a simpler fingerprint representation (like Morgan fingerprints) for the initial active learning rounds. Reserve high-cost QM features only for the final validation and for molecules selected by the active learning cycle [44].