Optimizing Computational Chemistry Parameters: A Practical Guide for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing computational chemistry parameters to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of drug discovery.

Optimizing Computational Chemistry Parameters: A Practical Guide for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing computational chemistry parameters to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of drug discovery. It covers foundational principles, advanced methodologies including AI and machine learning, practical troubleshooting for parameter selection, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to navigate the critical speed-accuracy trade-offs in computational modeling, ultimately facilitating the design of more effective therapeutics.

Core Principles: Understanding the Speed-Accuracy Trade-off in Computational Chemistry

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles and Method Selection

Q1: What is the core difference between a Quantum Mechanics (QM) and a Molecular Mechanics (MM) approach?

The core difference lies in the treatment of electrons. Molecular Mechanics (MM) treats atoms as classical particles, using a ball-and-spring model. It calculates energy based on pre-defined parameters for bond stretching, angle bending, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic), completely ignoring explicit electrons [1]. This makes it fast but incapable of modeling chemical reactions where bonds form or break. In contrast, Quantum Mechanics (QM) explicitly models electrons by solving the Schrödinger equation (approximately), describing electron density, polarization, and bond formation/breaking from first principles [1] [2].

Q2: When should I use a pure QM method versus a hybrid QM/MM method?

The choice depends on your system size and the process you are studying [3].

- Pure QM: Best for studying isolated chemical reactions, small molecular clusters, or calculating highly accurate electronic properties for systems of up to a few hundred atoms [3] [2].

- Hybrid QM/MM: Essential for studying chemical processes within a biological or condensed-phase environment, such as enzyme catalysis or reactions in solution [4] [5]. The reactive core (where bonds change) is treated with QM, while the surrounding protein and solvent are treated with the faster MM, offering a balance of accuracy and computational feasibility [3].

Q3: What are the main types of embedding in QM/MM simulations?

There are three primary embedding schemes, with increasing levels of sophistication [4] [5]:

- Mechanical Embedding: The QM region is not electronically influenced by the MM environment. The interaction is treated purely with the MM force field. This is less accurate for processes where polarization is key.

- Electrostatic Embedding: The most common approach. The point charges of the MM atoms are included in the QM Hamiltonian, so the QM region's electron density is polarized by the classical environment [5].

- Polarizable Embedding: An advanced method that allows the MM environment to also be polarized by the QM region and by itself, using polarizable force fields (e.g., CHARMM Drude, AMOEBA). This provides a more realistic two-way polarization response but is computationally more demanding [6] [5].

Technical and Operational Challenges

Q4: My QM/MM hydration free energy results are worse than pure MM results. What could be wrong?

This is a known challenge, often stemming from an imbalance between the QM and MM components [6]. The solute's Lennard-Jones parameters are typically optimized for use with a fixed-charge MM force field and may not be compatible with your chosen QM method or a polarizable water model. This mismatch creates biased solute-solvent interactions [6]. To troubleshoot:

- Ensure the van der Waals parameters for the QM solute are compatible with your QM method.

- Test the sensitivity of your results to different QM methods (e.g., DFT vs. MP2) and MM water models (fixed-charge vs. polarizable) [6].

- Consider using a polarizable MM force field for the environment, as it can provide better phase space overlap with the QM Hamiltonian [6].

Q5: How do I handle a covalent bond at the boundary between my QM and MM regions?

Creating a boundary across a covalent bond is a common challenge. Simply cutting the bond leaves an unsatisfied valence in the QM region. Several techniques exist to address this [5]:

- Link Atom (LA): The most common method, where a hydrogen atom (or other capping atom) is added to the QM atom at the boundary to satisfy its valence. The MM charge on the corresponding MM atom is often set to zero [4] [5].

- Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO): A more sophisticated method that creates special hybrid orbitals at the boundary atom to seamlessly connect the QM and MM regions [5].

- Pseudobond: Replaces the MM boundary atom with a special atom with customized parameters that mimics the severed bond [5].

Q6: My QM/MM simulation is not converging or is running extremely slowly. How can I improve performance?

Performance issues can arise from several factors [3]:

- QM Region Size: The computational cost of QM scales poorly with the number of atoms. Review your QM region selection—is it larger than necessary? Use systematic tools to identify the minimal set of residues essential for an accurate reaction description [3].

- Level of Theory: High-level ab initio methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) are prohibitively expensive for dynamics. Consider using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with an appropriate functional, or even semi-empirical methods (e.g., PM6, DFTB) for initial sampling, followed by energy re-calculation at a higher level (e.g., the "Learn on Chemical" or "Look" approach) [3].

- Sampling: For free energy calculations, use advanced sampling techniques like umbrella sampling or free energy perturbation. Reweighting classical ensembles generated with a polarizable force field to obtain QM/MM free energies can also be a efficient strategy [6] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unphysical Energies or Simulation Crash at the QM/MM Boundary

Symptoms: The simulation crashes with errors related to high energy, or you observe unrealistic bond lengths or angles at the boundary between the QM and MM regions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

This flowchart outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve boundary-related issues.

Recommended Actions:

- Verify Link Atom Setup: If using link atoms, ensure they are correctly positioned along the severed bond and that appropriate constraints are applied to prevent them from drifting and causing van der Waals clashes with the MM environment [5].

- Check MM Parameters: The classical atom at the boundary (to which the QM region is covalently linked) often requires special treatment. Its charge may need to be set to zero or redistributed to prevent over-polarization of the QM region. Its Lennard-Jones parameters may also need adjustment for compatibility [5].

- Upgrade the Boundary Method: If problems persist, consider implementing a more robust boundary method like the Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO) or Pseudobond approach, which are designed to create a more chemically realistic and stable boundary [5].

Problem 2: Selecting an Inappropriate QM Method for the Research Problem

Symptoms: Results do not agree with experimental data (e.g., reaction barriers are significantly off, interaction energies are inaccurate), especially for systems involving transition metals, charge transfer, or dispersion forces.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Use the following table to diagnose and select an appropriate QM method based on your system's properties.

Table 1: Quantum Method Selection Guide for Common Scenarios

| System / Property of Interest | Recommended QM Method(s) | Methods to Avoid / Use with Caution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Bond Formation, Reaction Mechanism | DFT (with hybrid functional), MP2 [6] | Molecular Mechanics (MM) | MM cannot model bond breaking/forming. DFT functional choice is critical [1] [3]. |

| Transition Metal Centers | DFT+U, specific meta-GGA/hybrid functionals [3] | Standard LDA/GGA DFT, Hartree-Fock | Standard DFT has known errors for metal centers (e.g., self-interaction error). Method must describe diverse spin states and ligand field effects [3]. |

| Non-Covalent Interactions (e.g., van der Waals) | MP2, DFT with dispersion correction (DFT-D), M06-2X [6] [3] | Standard DFT, Hartree-Fock | Hartree-Fock and most standard DFT functionals poorly describe dispersion forces, leading to underestimated binding [2]. |

| Large System Screening (>500 atoms) | Semi-empirical (AM1, PM6, DFTB), QM/MM [3] [2] | High-level ab initio (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Semi-empirical methods offer speed but lower accuracy. QM/MM is the preferred choice for large biomolecular systems [5] [2]. |

| Charge Transfer & Strong Correlation | Wavefunction Theory (WFT), specialized DFT functionals [3] | Standard DFT, low-level semi-empirical | Strongly correlated systems (e.g., in some superconductors or radicals) are a challenge for most common DFT functionals [7]. |

Problem 3: Inefficient Sampling and High Computational Cost

Symptoms: Free energy estimates have large uncertainties, the simulation fails to explore relevant configurations, or the calculation takes an impractically long time.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Experimental Protocol for Efficient QM/MM Free Energy Calculation [6] [3]:

System Preparation:

- Target System: A solute (e.g., drug-like molecule) in explicit solvent (e.g., water).

- Goal: Calculate the absolute hydration free energy (ΔG_hyd), a key benchmark for solvation models.

Generate Classical Ensembles:

- Perform long-scale (e.g., 500 ns) molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the solute annihilation process in both the aqueous phase and the gas phase. This provides thorough sampling of the classical configurational space.

- Recommended: Use a polarizable force field (e.g., CHARMM Drude) for the classical sampling, as it has been shown to have higher phase space overlap with QM Hamiltonians, leading to better convergence when reweighting [6].

QM/MM Reweighting:

- Extract a large number of uncorrelated snapshots (e.g., saved every 20 ps) from the classical MD trajectories.

- For each snapshot, perform a single-point QM/MM energy calculation for both the solute and the system without the solute. The QM method can be DFT, MP2, etc., applied to the solute.

- Use free energy perturbation (FEP) or Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) methods to reweight the classical ensemble averages to obtain the QM/MM free energy difference.

Analysis and Validation:

- Compare the QM/MM hydration free energy to high-quality experimental data and to the purely classical result.

- Assess the statistical error and convergence of the free energy estimate. The use of a polarizable MM reference state typically leads to faster convergence and smaller variance compared to a fixed-charge reference state [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for QM/MM Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to QM/MM |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM [6] [5] | Software Suite | Molecular dynamics simulation | Widely used for MM and QM/MM simulations, supports both fixed-charge and polarizable (Drude) force fields. |

| Gaussian [2] | Software Package | Quantum chemical calculations | A standard program for performing QM calculations (HF, DFT, MP2), often integrated as the QM engine in QM/MM. |

| LICHEM [5] | Software Interface | QM/MM simulations | A code designed to interface QM and MM software packages, supporting advanced features like polarizable force fields. |

| CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) [6] | Force Field | MM parameters for organic molecules | Provides parameters for drug-like molecules in the CHARMM ecosystem. |

| CHARMM Drude Force Field [6] | Polarizable Force Field | MM parameters with explicit polarization | Used for more accurate classical sampling that better matches QM electronic response. |

| TeraChem [3] | Software Package | GPU-accelerated QM and QM/MM | Enables very fast QM calculations, making QM/MM dynamics and property calculations more feasible. |

FAQs: Foundational Concepts for Researchers

1. What is a basis set and why is its selection critical? A basis set is a set of functions used to represent the electronic wave function in computational models like Hartree-Fock or Density Functional Theory (DFT). These functions are combined in linear combinations to create molecular orbitals, turning complex partial differential equations into algebraic equations that can be solved efficiently on a computer. The selection is a compromise between accuracy and computational cost; larger basis sets approach the complete basis set (CBS) limit but require significantly more resources. [8] [9]

2. What is the key limitation of the Hartree-Fock method that advanced methods correct? The Hartree-Fock method uses a mean-field approximation, treating each electron as moving in an average field of the others. This approach neglects electron correlation, the instantaneous interaction between electrons, leading to substantial inaccuracies in predicting properties like bond lengths, vibrational frequencies, and reaction energies. Correcting for this correlation is a primary goal of advanced computational methods. [10]

3. How do modern neural network potentials (NNPs) like those trained on OMol25 overcome traditional computational limits? Methods like DFT, while more efficient than Hartree-Fock, can still be prohibitively expensive for large, complex systems. Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) or NNPs are trained on high-accuracy quantum chemical data (e.g., from DFT or coupled-cluster theory). Once trained, they can predict energies and forces with near-DFT accuracy but ~10,000 times faster, enabling simulations of large biomolecular systems or materials that were previously impossible. [11] [12]

4. What makes the OMol25 dataset a transformative resource for training AI models in chemistry? OMol25 is unprecedented in its scale and chemical diversity. It contains over 100 million molecular snapshots calculated at a high level of DFT theory (ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD), cost 6 billion CPU hours to generate, and covers a wide range of chemistries, including biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes with up to 350 atoms. This vast and chemically diverse dataset allows for the training of more robust and generalizable neural network potentials. [11] [12]

Troubleshooting Common Computational Issues

Inaccurate Energy and Molecular Property Predictions

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant errors in bond lengths and vibrational frequencies compared to experimental data. | Use of a method that neglects electron correlation (e.g., Hartree-Fock) or an insufficient basis set. [10] | Upgrade to a correlated method like DFT with a suitable functional (e.g., ωB97M-V) or a wavefunction-based method like CCSD(T). Use a larger basis set with polarization functions. [10] [12] |

| Poor description of non-covalent interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces) or anionic systems. | Lack of diffuse functions in the basis set, which are essential for modeling the "tail" of electron density far from the nucleus. [8] | Switch to a basis set that includes diffuse functions, such as 6-31+G or aug-cc-pVDZ. [8] |

| Inaccurate reaction energies and thermodynamic predictions. | Inadequate treatment of electron correlation, particularly in systems with strong electron-electron interactions (e.g., transition metal complexes, radical species). [10] | Employ a higher-level correlation method such as Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) or use a more sophisticated DFT functional validated for your chemical system. [10] [13] |

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| DFT calculations becoming intractable for large molecular systems (e.g., proteins, complex materials). | The computational cost of DFT scales poorly with system size, making large simulations impossible on standard resources. [11] | Use a pre-trained Neural Network Potential (NNP) like Meta's eSEN or UMA models trained on OMol25. These provide DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. [11] [12] |

| High-level correlated calculations (e.g., CCSD(T)) are too slow even for medium-sized molecules. | The computational expense of methods like CCSD(T) grows very rapidly (e.g., 100x for doubling electrons). [13] | Leverage new machine learning approaches like MEHnet, which are trained on CCSD(T) data and can predict multiple electronic properties accurately and rapidly for larger systems. [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Selecting a Basis Set for Organic Molecule Geometry Optimization

Objective: To achieve chemically accurate results for an organic molecule while balancing computational cost.

- Starting Point: Begin with a standard double-zeta valence basis set like 6-31G or cc-pVDZ for initial geometry scans and optimizations. [8]

- Add Polarization: For final, publication-quality geometry optimization and frequency calculations, add polarization functions to all atoms. This is typically denoted by

*(heavy atoms) or(all atoms) in Pople-style sets, e.g., 6-31G, or use correlation-consistent sets like cc-pVTZ. Polarization functions (d-orbitals on carbon, p-orbitals on hydrogen) add flexibility to describe the deformation of electron density during bond formation. [8] - Add Diffuse Functions: If the system involves anions, weak non-covalent interactions, or spectroscopy, use basis sets with diffuse functions, such as 6-31+G or aug-cc-pVDZ. Diffuse functions are essential for describing the spatially extended orbitals in these systems. [8]

- Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) Correction: When calculating interaction energies (e.g., in complexes), apply a BSSE correction, such as the Counterpoise method.

Protocol: Assessing the Impact of Electron Correlation

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effect of electron correlation on molecular properties.

- System Selection: Choose a test molecule (e.g., water, H₂O). [10]

- Single-Point Energy Calculation with HF: Perform a geometry optimization and frequency calculation using the Hartree-Fock method and a moderate basis set (e.g., 6-31G). Record the bond length(s), vibrational frequency(s), and total energy.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation with Correlated Method: Using the same molecular geometry and basis set, perform a single-point energy calculation using a method that includes electron correlation. Standard choices include:

- Comparison and Analysis: Compare the results from step 3 with those from step 2. You will typically observe that correlated methods yield longer, more accurate bond lengths and lower vibrational frequencies compared to Hartree-Fock, which consistently overestimates binding. [10]

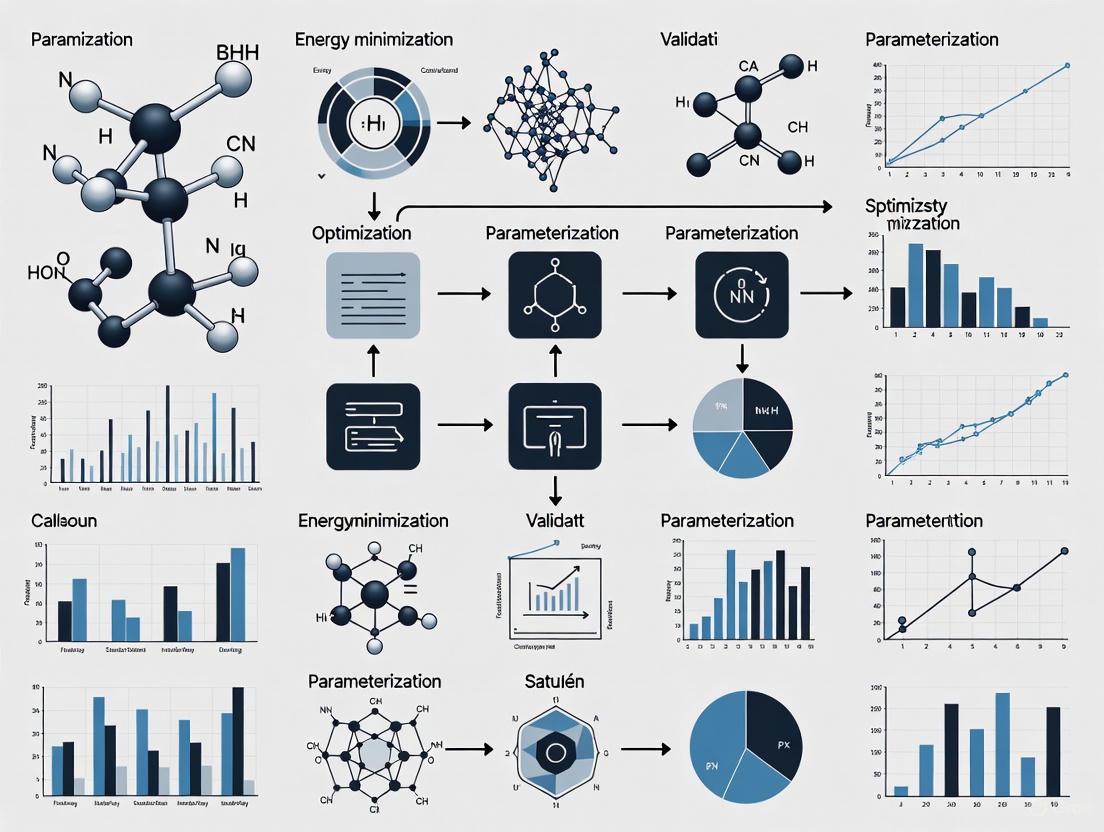

Essential Workflow Visualizations

Computational Parameter Selection Strategy

Neural Network Potential Application Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pople Basis Sets (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311+G) | Split-valence basis sets for efficient HF/DFT calculations on organic molecules. Notation indicates primitive Gaussians for core and valence orbitals. [8] | Ideal for molecular structure determination. Add * for polarization, + for diffuse functions. More efficient per function than other types for HF/DFT. [8] |

| Dunning Basis Sets (cc-pVXZ: X=D,T,Q,5) | Correlation-consistent basis sets designed to systematically converge post-HF calculations (e.g., CCSD(T)) to the complete basis set limit. [8] | The go-to choice for high-accuracy wavefunction-based methods. Larger X (D→T→Q) increases accuracy and cost. Use "aug-" prefix for diffuse functions. [8] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computationally efficient workhorse that uses the electron density to account for electron correlation via an approximate exchange-correlation functional. [10] [14] | Functional choice is critical. Modern functionals like ωB97M-V offer high accuracy for diverse chemistries. B3LYP is historically popular but may be less accurate for non-covalent interactions. [12] [15] |

| Coupled Cluster Theory (e.g., CCSD(T)) | A high-level wavefunction-based method, considered the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its high accuracy in modeling electron correlation. [10] [13] | Computationally very expensive, traditionally limited to small molecules (~10 atoms). New ML models trained on CCSD(T) data are making this accuracy accessible for larger systems. [13] |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learning models trained on quantum mechanical data to predict energies and forces with high accuracy and low computational cost. [11] [12] | Models like eSEN and UMA, trained on OMol25, provide near-DFT accuracy but are thousands of times faster, enabling simulations of large, complex systems. [11] [12] |

| OMol25 Dataset | A massive, open dataset of over 100 million molecular configurations with properties calculated at a high level of DFT. Used for training generalizable MLIPs/NNPs. [11] | Provides unprecedented chemical diversity (biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes). The primary resource for developing next-generation computational models. [11] [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) value tell me about my energy prediction model's accuracy?

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is a measure of the strength and direction of a linear relationship between your model's predictions and the experimental or reference data [16]. It ranges from -1 to +1 [17] [16] [18].

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) Value | Strength of Relationship | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Greater than ±0.5 | Strong | Positive / Negative |

| Between ±0.3 and ±0.5 | Moderate | Positive / Negative |

| Between 0 and ±0.3 | Weak | Positive / Negative |

| 0 | No linear relationship | None [16] |

In practice, a study benchmarking AlphaFold3 for predicting protein-protein binding free energy changes reported a "very good" Pearson correlation of 0.86 against the SKEMPI 2.0 database, indicating a strong, positive linear relationship between its predictions and the reference values [19].

Q2: I've obtained a low Pearson correlation. What are the common causes and how can I troubleshoot them?

A low correlation suggests a weak linear relationship. The table below outlines common issues and methodological checks to perform.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Methodological Check & Troubleshooting Guide |

|---|---|---|

| Data Distribution | Non-normal data distribution [16] [18] | Verify data normality with histograms or statistical tests (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk). For non-normal or ordinal data, use Spearman's rank correlation instead [17] [16]. |

| Outliers | Presence of influential outliers [16] | Examine a scatter plot of predictions vs. reference data to identify anomalous points. Investigate the source of outliers (e.g., experimental error, simulation instability). |

| Model/System Issues | Incorrectly described system interactions [20] | For force-field methods, check the quality of Lennard-Jones and other non-bonded parameters [20]. Consider running longer simulations to improve sampling, especially for charge changes [21]. |

| Poor hydration in simulations [21] | Use techniques like 3D-RISM or GIST to analyze hydration sites. Implement advanced sampling like Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCNCMC) to ensure proper hydration [21]. | |

| Relationship Type | Non-linear or complex relationship [16] | Plot your data to visually assess if the relationship is monotonic but non-linear. If so, Spearman's correlation may be more appropriate [16]. |

Q3: My model shows a strong Pearson correlation, but the prediction error (e.g., RMSE) is still high. Is this possible?

Yes, this is a critical distinction. A strong correlation indicates that the relative ordering and trend of your predictions are correct, but it does not guarantee their absolute accuracy [19].

The AlphaFold3 benchmark is a prime example: it achieved a high Pearson correlation (r=0.86), but its Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was 8.6% higher than calculations based on original Protein Data Bank structures [19]. This means that while AlphaFold3's predictions were excellent at ranking mutations by their effect, there was a consistent deviation in the absolute magnitude of those predicted effects. Always complement correlation analysis with error metrics like RMSE or Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

Q4: In free energy perturbation (FEP), how can I improve the correlation between calculated and experimental binding free energies?

Optimizing your FEP protocol is key. Here are some advanced methodologies:

- Automate Lambda Scheduling: Use short exploratory calculations to automatically determine the optimal number of intermediate states (lambda windows) for each transformation, improving accuracy and saving GPU time [21].

- Refine Force Field Parameters: Poor torsion descriptions can introduce error. Use quantum mechanics (QM) calculations to generate improved, specific torsion parameters for your ligands [21].

- Handle Charges Carefully: For perturbations involving formal charge changes, run longer simulations to improve sampling and consider using a counterion to maintain charge neutrality where appropriate [21].

- Ensure Proper Hydration: Use techniques like Grand Canonical Non-equilibrium Candidate Monte Carlo (GCNCMC) to correctly sample water molecules in the binding site, reducing hysteresis and improving reliability [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details key computational tools and their functions in energy prediction and benchmarking workflows.

| Tool / Solution Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Open Force Fields (OpenFF) | A community-driven initiative to develop accurate, open-source force fields for molecular simulations, continually improving the description of ligand energetics [21]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine learning models trained on quantum chemical data that provide a fast and accurate way to compute molecular potential energy surfaces, bypassing expensive quantum mechanics calculations [12]. |

| Running Average Power Limit (RAPL) | A software interface for estimating the energy consumption of CPUs and RAM, useful for benchmarking the computational efficiency of different methods and hardware [22]. |

| Active Learning Workflows | A cycle that combines slow, accurate methods (like FEP) with fast, approximate methods (like QSAR) to efficiently explore large chemical spaces and focus resources on promising candidates [21]. |

| Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | A simulation method to calculate the binding affinity of a single ligand independently, offering greater scope for modeling diverse compounds compared to relative methods [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Validating Energy Predictions

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for running and validating computational energy predictions, incorporating checks for correlation and error.

Decision Pathway for Interpreting Validation Results

After calculating your metrics, use this logical pathway to diagnose your model's performance and identify the next steps.

The Role of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation in Molecular Simulation

Fundamental Concepts FAQ

What is the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) Approximation? The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is a fundamental concept in quantum chemistry that allows for the separation of nuclear and electronic motions in molecular systems. It assumes that due to the much larger mass of atomic nuclei compared to electrons (a proton is nearly 2000 times heavier than an electron), electrons move much faster and can instantaneously adjust to any change in nuclear positions. This enables researchers to solve for electronic wavefunctions while treating nuclei as fixed, significantly simplifying molecular quantum mechanics calculations [23] [24] [25].

What is the mathematical basis for this separation?

The BO approximation recognizes that the total molecular wavefunction can be approximated as a product of electronic and nuclear wavefunctions: Ψ_total ≈ ψ_electronic * ψ_nuclear [23]. The full molecular Hamiltonian is separated, allowing you to first solve the electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclear positions:

H_e χ(r,R) = E_e(R) χ(r,R)

where E_e(R) becomes the potential energy surface for the subsequent nuclear Schrödinger equation:

[T_n + E_e(R)] φ(R) = E φ(R) [23] [26].

How does this approximation enable molecular dynamics simulations? In Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD), the forces acting on nuclei are derived from the ground state electronic configuration via the Hellmann-Feynman theorem. The nuclear motion is then described by classical mechanics, integrating Newton's equations of motion using algorithms like Velocity-Verlet while the electrons remain in their ground state for each nuclear configuration [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: When the BO Approximation Fails

Problem 1: Conical Intersections and Avoided Crossings

Symptoms: Unexpected energy transfers between electronic states, inaccurate prediction of reaction pathways in photochemical processes, or failure to model internal conversion accurately.

Underlying Cause: The BO approximation breaks down when electronic energy levels become very close or intersect, creating a conical intersection where the electronic wavefunction changes rapidly with nuclear coordinates [28]. In these regions, the assumption that electrons instantly adjust to nuclear motion becomes invalid.

Solutions:

- Multi-reference methods: Use MRCI or MR-EOM-CC instead of single-reference methods like Hartree-Fock or DFT [28]

- Non-adiabatic dynamics: Implement surface hopping or other beyond-BO algorithms that explicitly account for couplings between electronic states

- Vibronic coupling: Include explicit electron-nuclear coupling terms in your Hamiltonian

Problem 2: Light Nuclear Systems

Symptoms: Significant errors in calculated vibrational spectra, inaccurate zero-point energies, or poor prediction of thermodynamic properties for systems containing light atoms (especially hydrogen).

Underlying Cause: For light nuclei, quantum effects like zero-point motion and tunneling become significant because the mass ratio justification for the BO approximation weakens [28] [29].

Solutions:

- Path-integral dynamics: Treat light nuclei with quantum mechanical methods while maintaining BO for electrons

- Diagonal Born-Oppenheimer Correction (DBOC): Add first-order correction terms to account for nuclear momentum coupling [28]

- Vibrational SCF: Apply self-consistent field methods specifically for nuclear motion

Problem 3: Electron-Phonon Coupling and Polarons

Symptoms: Inaccurate description of charge transport in materials, failure to predict superconducting properties, or incorrect modeling of spectral line shapes.

Underlying Cause: In condensed matter systems, particularly semiconductors and superconductors, strong coupling between electronic states and lattice vibrations (phonons) can invalidate the BO approximation [28].

Solutions:

- Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT): Add back electron-phonon coupling after initial BO calculation

- Polaronic methods: Use specialized approaches that explicitly dress electrons with lattice distortions

- Beyond-adiabatic treatments: Implement methods that treat electron-nuclear dynamics on equal footing

Problem 4: Ultra-High Precision Spectroscopy

Symptoms: Discrepancies between calculated and observed rotational-vibrational spectra at high resolution, inability to match experimental isotope effects.

Underlying Cause: For spectroscopic precision exceeding ~0.1 cm⁻¹, non-adiabatic effects and breakdown of the BO approximation become significant enough to affect results [28].

Solutions:

- Non-adiabatic perturbation theory: Include corrections to rotational-vibrational Hamiltonians

- Direct non-BO calculations: Use explicitly correlated methods that treat all particles quantum mechanically for small systems

- DBOC for spectroscopic constants: Compute diagonal Born-Oppenheimer corrections for molecular parameters

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard BOMD Implementation

Purpose: To simulate nuclear dynamics on a single Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surface.

Workflow:

- Initialization: Set initial nuclear positions

R₀and velocitiesv₀ - Electronic Structure Calculation: For current nuclear positions

R_n, solve electronic Schrödinger equation to obtain energyE_nand forcesF_n - Nuclear Propagation: Update nuclear positions and velocities using Velocity-Verlet algorithm:

- Force Recalculation: Compute new forces

F_{n+1}for positionsR_{n+1} - Velocity Finalization: Complete velocity update:

v_{n+1} = v_{n+1/2} + (Δt/2m) * F_{n+1} - Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 for desired number of MD steps [27]

Typical Parameters:

- Time step (Δt): 0.5-2.0 fs (depending on system stiffness)

- Thermostat: Nose-Hoover, Langevin, or Andersen for temperature control

- Convergence criteria for SCF: 10⁻⁶ - 10⁻⁸ Ha for energy differences

Protocol 2: Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics with Surface Hopping

Purpose: To simulate dynamics involving multiple electronic states where BO approximation fails.

Workflow:

- Multiple State Calculation: For current nuclear positions, solve electronic structure for multiple electronic states

- Non-adiabatic Couplings: Compute derivative couplings between electronic states

⟨ψ_i|∇_R|ψ_j⟩ - Surface Hopping Decision: At each time step, determine probability of hopping between states based on non-adiabatic coupling strength

- Stochastic Hopping: Implement hops between potential energy surfaces using Monte Carlo approach

- Velocity Adjustment: Rescale nuclear velocities when hops occur to conserve energy

- Continuation: Propagate dynamics on current potential energy surface until next possible hop [28]

Visualization of Key Concepts

Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Process

BO Approximation Breakdown Scenarios

Computational Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Methods for Molecular Simulation

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Primary Function | BO Approximation Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure | Hartree-Fock, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T) | Solve electronic problem for fixed nuclei | Core application - depends on BO separation |

| Dynamics Algorithms | Born-Oppenheimer MD, Car-Parrinello MD | Propagate nuclear motion | BOMD uses BO; CPMD maintains electronic adiabaticity |

| Beyond-BO Methods | Surface hopping, Ehrenfest dynamics, MCTDH | Handle non-adiabatic effects | Explicitly addresses BO breakdown |

| Vibrational Methods | Harmonic approximation, VSCF, path integrals | Describe nuclear quantum effects | Builds on BO potential surfaces |

| Spectroscopic Methods | VPT2, DVR, linear response | Predict experimental observables | Often includes non-adiabatic corrections |

Performance Data and Quantitative Comparisons

Table: Characteristic Energy and Time Scales in Molecular Systems

| Process Type | Energy Scale | Time Scale | BO Approximation Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Motion | 1-10 eV (valence) | ~1-100 as (attoseconds) | Fast electrons justify BO assumption |

| Molecular Vibrations | 0.1-0.5 eV | ~10-100 fs (femtoseconds) | Nuclear motion treated separately |

| Molecular Rotation | 0.001-0.01 eV | ~1-10 ps (picoseconds) | Well-separated from electronic motion |

| Non-adiabatic Transitions | 0.01-1 eV | ~10-100 fs | Regions where BO approximation fails |

| Zero-point Energy | 0.01-0.1 eV (per mode) | N/A | Correction needed for light atoms |

Advanced Implementation Notes

Thermostat Selection for BOMD:

- Andersen thermostat: Uses stochastic collisions with fictitious particles; adjust collision probability

q_col = 1 - e^(-Δt/τ)[27] - Langevin thermostat: Implements viscous solvent model with fluctuation-dissipation; update momenta as

p_new = p * e^(-γΔt)[27] - Nose-Hoover chains: Deterministic thermostat with extended Lagrangian; set thermostat masses as

Q_th1 = 3N*k_B*T/ω²for proper sampling [27]

Convergence Monitoring:

- Track electronic energy differences between MD steps (should be < 10⁻⁵ Ha)

- Monitor temperature fluctuations and energy conservation in NVE simulations

- Check for unphysical drift in total energy, indicating SCF convergence issues

- Validate forces using the Hellmann-Feynman theorem consistency

FAQs: Choosing and Troubleshooting Computational Methods

FAQ 1: What are the core differences between CCSD(T), DFT, and Force Fields, and when should I use each one?

The choice between these methods hinges on a trade-off between computational cost and the required accuracy and system size.

- CCSD(T) is the gold standard for accuracy but is prohibitively expensive for large systems. Use it for small molecules when you need benchmark-quality results for energies or to validate lower-level methods [30] [31].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) offers a balance between accuracy and efficiency. It is the workhorse for studying ground-state properties, reaction mechanisms, and electronic structures of medium-sized systems, such as reaction intermediates and solid-state materials [32] [31]. Its accuracy depends on the chosen functional.

- Force Fields use pre-defined analytical functions to achieve high computational efficiency for large systems. They are ideal for molecular dynamics simulations of proteins, polymers, and materials, providing insights into structural dynamics, adsorption, and diffusion over long timescales [32] [33]. They are generally not suitable for modeling reactions where bonds are broken or formed, except for specialized reactive force fields.

The table below provides a structured comparison to guide your selection.

| Method | Computational Cost | Typical System Size | Key Applications | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Very High [32] [31] | Small molecules [31] | Benchmark accuracy; validating DFT/force fields [30] [31] | Scales poorly with system size; computationally infeasible for large systems [32] |

| DFT | Moderate to High [32] | Medium-sized systems (up to hundreds of atoms) [32] | Reaction mechanisms; electronic structure prediction; material properties [32] [31] | Accuracy depends on functional; can struggle with van der Waals forces, strongly correlated systems [31] |

| Force Fields | Low [32] | Very large systems (10,000+ atoms) [32] | Protein folding; material adsorption; diffusion processes [32] [33] | Fixed bonding prevents modeling chemical reactions (in classical FFs); lower accuracy than QM [32] |

FAQ 2: My DFT results do not agree with my experimental data. What should I do?

Discrepancies between DFT and experiment are common and can be systematically addressed.

- Troubleshooting Step 1: Verify the Functional. Different density functionals have known strengths and weaknesses. If your system involves dispersion forces (e.g., adsorption, biomolecules), ensure your functional includes an empirical dispersion correction (like DFT-D3 or DFT-D4) [31]. For reaction barriers, meta-GGAs or hybrid functionals often perform better.

- Troubleshooting Step 2: Check the Basis Set. A larger, more flexible basis set can improve accuracy but increases cost. Ensure your basis set is appropriate for your system and property of interest [12].

- Troubleshooting Step 3: Consider a Multi-Pronged Validation Approach. If resources allow, use CCSD(T) on a smaller model system to validate your DFT functional's performance for the specific property you are calculating [30]. Alternatively, consider a fused data learning strategy, where a machine learning force field is trained simultaneously on your DFT data and the experimental observables, effectively correcting for the DFT functional's inaccuracies [30].

FAQ 3: How do I develop a reliable classical force field for a new material?

Developing a robust force field is a parameterization process that relies on high-quality reference data.

- Experimental Protocol 1: Target Data Selection

- Objective: Define a set of quantum mechanical (QM) and/or experimental properties for parameter optimization.

- Procedure: Perform QM calculations (e.g., DFT) on a diverse set of atomic configurations relevant to your system. Essential target data includes:

- Experimental Protocol 2: Parameter Optimization

- Objective: Find the force field parameters that best reproduce the target data.

- Procedure: Use a parameter optimization toolkit (e.g., ParAMS) [34]. The workflow involves:

- Defining an objective function that quantifies the difference between force field predictions and target data.

- Employing optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms, Bayesian optimization) to minimize the objective function by iteratively adjusting parameters [34].

- Validating the final parameter set on a separate set of configurations and properties not used in training.

FAQ 4: When should I consider using machine learning force fields instead of traditional methods?

Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) are a powerful alternative when you need near-QM accuracy for systems too large for routine QM simulations.

- Consider MLFFs when:

- You require high accuracy for complex potential energy surfaces across a wide range of configurations [12].

- Your system involves large-scale molecular dynamics (e.g., biomolecules, complex materials) where traditional QM is too slow, and classical force fields are not accurate enough [30].

- You have access to a large, diverse, and high-quality QM dataset for training, such as the newly released OMol25 dataset which contains over 100 million calculations [12].

- Stick with Classical Force Fields when: Your system is well-described by existing parameters, and you need maximum computational speed for very long-timescale simulations (microseconds to milliseconds) [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Computational Chemistry

The table below lists key software, datasets, and tools that form the essential "reagent solutions" for modern computational chemistry research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Parameter Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| ParAMS [34] | Software Toolkit | Parameter optimization for atomistic models. | Efficiently fine-tunes force field parameters using genetic algorithms, gradient-based, or Bayesian optimization methods. |

| OMol25 Dataset [12] | Dataset | Massive repository of quantum chemical calculations. | Provides high-quality training data for developing and benchmarking machine learning force fields. |

| ILJ Formulation [33] | Potential Function | Improved Lennard-Jones potential for intermolecular interactions. | Offers a more accurate and transferable description of van der Waals forces in force fields for adsorption and material science. |

| DiffTRe Method [30] | Algorithm | Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting. | Enables direct training of ML potentials on experimental data, bypassing the need for backpropagation through entire simulations. |

| Canonical Approaches [35] | Mathematical Method | Generates highly accurate potentials from minimal ab initio data. | Creates precise pair potentials without traditional fitting, useful for molecular dynamics under extreme conditions. |

Advanced Techniques and Real-World Applications in Drug Design

Leveraging AI and Graph Neural Networks for Multi-Task Property Prediction

Troubleshooting Guide: Common GNN Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My multi-task GNN model is overfitting to smaller datasets. What strategies can I use to improve generalization?

Issue: Overfitting on small, expensive computational chemistry datasets.

Solutions:

- Implement a Multi-Task Architecture: Use a single model with a shared backbone to evaluate multiple electronic properties simultaneously. This allows knowledge gained from predicting one property to inform predictions of others, which is particularly beneficial when data for individual tasks is scarce [36].

- Incorporate Physics-Informed Inductive Biases: Utilize an E(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture. This built-in symmetry ensures the model's predictions are consistent with physical laws (e.g., rotational and translational invariance), guiding the learning process and reducing reliance on large amounts of data [36].

- Leverage Advanced Optimization Techniques: Employ optimizers like Adam, which adapts learning rates for each parameter using estimates of the first and second moments of the gradients. This leads to faster and more stable convergence, especially in high-dimensional parameter spaces common in chemistry [37].

- Adopt a Hybrid Modeling Approach: Pre-train your model using highly accurate quantum chemistry methods like CCSD(T). While computationally expensive, using CCSD(T) results as training data provides a "gold standard" target, enabling the model to achieve high accuracy with fewer data points than would be required with less accurate methods [36].

FAQ 2: The performance of my property predictor drops significantly when evaluating newly generated molecules. How can I address this out-of-distribution generalization problem?

Issue: Poor performance on molecules that are structurally different from those in the training set.

Solutions:

- Benchmark with DFT-Verified Properties: Do not rely solely on the ML model's own predictions for validation. Perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations on a subset of generated molecules to confirm the model's performance on out-of-distribution data. Studies show that proxy models can maintain low error on their test set but exhibit much larger errors (e.g., ~0.8 eV vs. 0.12 eV) on newly generated structures [38].

- Enforce Chemical Valence Rules: When using GNNs for inverse design (generating molecules), ensure your graph construction method strictly enforces chemical rules. This can be done by defining atoms from their valence (sum of bond orders) and using constrained optimization to prevent the generation of chemically invalid structures, keeping the model within a more realistic region of chemical space [38].

- Explore Novel Architectures for Expressivity: Investigate next-generation GNNs like Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs). These models replace standard multi-layer perceptrons with learnable, Fourier-series-based functions on the edges, which can enhance the model's ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships in molecular data, potentially improving generalization [39].

FAQ 3: The training process of my GNN is unstable and slow. How can I improve its convergence?

Issue: Unstable training dynamics and slow convergence.

Solutions:

- Select an Appropriate Optimizer: Use adaptive optimizers like Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation). Adam combines the benefits of momentum (which accelerates convergence in relevant directions) and adaptive learning rates (which stabilizes updates for each parameter), making it well-suited for the noisy and high-dimensional landscapes of GNN training [37].

- Utilize Residual Connections: In deeper GNN architectures, incorporate residual KAN (Kolmogorov-Arnold Network) layers or other residual connections. This helps mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, allowing for the training of more powerful and complex networks without severe instability [39].

- Apply Gradient Clipping: This technique caps the norm of the gradients during backpropagation. It prevents exploding gradients, which are a common cause of training instability in deep neural networks, including GNNs.

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Multi-Task Electronic Property Predictor

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a GNN capable of predicting multiple quantum chemical properties from a single model, as demonstrated by the MEHnet architecture [36].

1. Data Preparation and Pre-processing:

- Source Data: Obtain molecular structures and their corresponding high-fidelity property data. Ideal sources are quantum chemistry databases (e.g., QM9) where properties are calculated using methods like CCSD(T) or DFT [36] [38].

- Graph Representation: Convert each molecule into a graph

G = (V, E), where nodes (V) represent atoms and edges (E) represent chemical bonds [40] [41]. - Feature Initialization:

- Node Features: Encode atom-specific information (e.g., atomic number, hybridization state).

- Edge Features: Encode bond-specific information (e.g., bond type, length).

2. Model Architecture Configuration:

- Backbone Network: Employ an E(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network. This ensures predictions are invariant to rotations and translations of the input molecule [36].

- Multi-Task Output Heads: The shared graph backbone is connected to multiple task-specific output layers. Each head is a small neural network that takes the final graph embeddings and maps them to a specific property (e.g., dipole moment, polarizability, HOMO-LUMO gap) [36].

3. Model Training and Loss Function:

- Loss Function: Use a weighted sum of losses for each task.

Total Loss = w₁ * Loss_property₁ + w₂ * Loss_property₂ + ... + wₙ * Loss_propertyₙAdjust the weightswᵢto balance the learning across tasks of different scales or importance. - Optimization: Use the Adam optimizer to minimize the total loss. A recommended starting learning rate is 0.001 [37].

4. Model Validation:

- Hold-out Test Set: Evaluate the final model on a held-out test set of molecules not seen during training.

- External Validation: For critical applications, validate the model's predictions on a small set of novel molecules using established computational methods like DFT to assess real-world performance [38].

Protocol 2: Inverse Molecular Design via Gradient Ascent on a GNN

This protocol describes a direct inverse design (DIDgen) method to generate molecules with desired properties by optimizing the input to a pre-trained GNN [38].

1. Pre-train a Property Prediction GNN:

- Train a GNN to predict a target property (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gap) from a molecular graph. This model's weights will be frozen during the generation phase.

2. Input Optimization Loop:

- Initialize a Graph: Start with a random graph or an existing molecular structure.

- Define a Target Property Loss:

Loss = (Predicted_Property - Target_Property)². - Gradient Ascent:

- Compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the input graph's adjacency matrix (

A) and feature matrix (F), while keeping the GNN weights fixed. - Update

AandFusing these gradients to create a new graph that better approximates the target property.

- Compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the input graph's adjacency matrix (

- Apply Valence Constraints:

3. Output and Validation:

- The optimized graph is decoded into a molecular structure.

- The properties of the generated molecule must be validated using independent, high-fidelity methods like DFT [38].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 1: Key software and algorithmic "reagents" for AI-driven molecular property prediction.

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| E(3)-equivariant GNN [36] | Model Architecture | Learns molecular representations invariant to 3D rotations/translations. | Core backbone for geometry-aware property prediction. |

| Multi-Task Learning Head [36] | Learning Paradigm | Predicts multiple molecular properties from a shared model. | Increases data efficiency; predicts property profiles. |

| Adam Optimizer [37] | Optimization Algorithm | Adapts learning rates for each parameter for stable training. | Standard optimizer for training deep neural networks. |

| Fourier-KAN Layer [39] | Network Component | Learnable activation functions based on Fourier series. | Used in KA-GNNs for enhanced expressivity and accuracy. |

| Gradient Ascent Input Optimization [38] | Generation Algorithm | Inverts a trained GNN to generate structures from properties. | Core engine for direct inverse molecular design (DIDgen). |

| Sloped Rounding Function [38] | Constraint Function | Enforces integer bond orders while allowing gradient flow. | Ensures chemically valid graphs during inverse design. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Multi-Task GNN Prediction Workflow

Diagram 2: Inverse Design via Gradient Ascent

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Why do my docked poses have good RMSD but poor physical validity or interaction recovery?

Answer: This common issue arises because some deep learning models, particularly generative diffusion and regression-based approaches, prioritize pose accuracy (low RMSD) over fundamental physical and chemical constraints. The PoseBusters toolkit has revealed that many AI-generated poses exhibit steric clashes, incorrect bond lengths/angles, and poor stereochemistry despite favorable RMSD values [42].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Run Physical Validity Checks: Use a tool like PoseBusters to evaluate the chemical and geometric consistency of your generated poses. This helps identify specific issues like protein-ligand clashes or incorrect bond lengths [42].

- Cross-Validate with Traditional Docking: Feed your best AI-generated poses into a traditional physics-based docking tool like Glide SP or AutoDock Vina for refinement. These methods often excel at producing physically plausible structures [42].

- Employ a Hybrid Method: For new projects, consider starting with a hybrid docking method (e.g., Interformer) that integrates AI-driven scoring with traditional conformational searches. These methods have demonstrated a better balance between pose accuracy and physical validity [42].

- Inspect Key Interactions Manually: Always visually inspect the top-ranked poses to verify the recovery of critical molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) that are essential for biological activity [42].

FAQ: How can I improve virtual screening performance when using predicted protein structures from AlphaFold2?

Answer: AlphaFold2-predicted structures are often in an "apo" (unbound) state and may not capture the ligand-induced conformational changes ("holo" state) necessary for effective virtual screening. Using the raw AlphaFold2 model directly can lead to suboptimal results [43].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Generate Drug-Friendly Conformations: Modify the AlphaFold2 structural space by altering its input multiple sequence alignment (MSA). Introduce alanine mutations at key binding site residues to induce conformational shifts that are more receptive to ligand binding [43].

- Optimize with a Genetic Algorithm: Guide the MSA modification process using a genetic algorithm. This strategy optimizes mutation sites through iterative ligand docking simulations and is particularly effective when a sufficient number of known active compounds is available to guide the search [43].

- Use a Random Search for Limited Data: If active compound data is scarce, a random search strategy for MSA modification can be more effective and still lead to significant improvements in virtual screening accuracy [43].

FAQ: How do I address the trade-off between binding affinity and drug-likeness in AI-generated molecules?

Answer:

Advanced 3D-SBDD generative models often produce molecules with good docking scores but distorted substructures (e.g., unreasonable ring formations) that compromise drug-likeness, solubility, and stability. This is a known limitation of models that focus primarily on the conditional distribution p(molecule | target) without incorporating broader drug-like property knowledge [44].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement a Collaborative Framework: Adopt a framework like Collaborative Intelligence Drug Design (CIDD), which synergizes 3D-SBDD models with Large Language Models (LLMs). The 3D-SBDD model generates initial molecules for the target, while the LLM refines them to enhance drug-likeness and correct unreasonable structures, preserving critical interactions [44].

- Apply Post-Processing Filters: Use rule-based metrics like the Molecular Reasonability Ratio (MRR) and Atom Unreasonability Ratio (AUR) to screen out generated molecules with problematic aromaticity patterns or unstable conjugations that deviate from known drug space [44].

- Iterative Refinement with LLMs: Employ LLMs in a cycle of analysis, design, and reflection. The LLM can identify key interaction fragments, propose structurally sound modifications, and evaluate designs to iteratively improve both binding affinity and drug-like properties [44].

FAQ: What strategies can improve the reliability of Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations?

Answer: FEP reliability can be affected by several factors, including ligand force field inaccuracies, charge changes, and inadequate hydration within the binding pocket [21].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Refine Torsion Parameters: For ligands with torsions poorly described by the standard force field, run quantum mechanics (QM) calculations to generate improved, system-specific torsion parameters. This enhances the accuracy of the molecular description [21].

- Manage Charge Changes: When studying ligands with different formal charges, introduce a counterion to neutralize the system and maintain a consistent net charge across the perturbation map. For these charged transformations, run longer simulation times to improve reliability [21].

- Ensure Proper Hydration: Use techniques like 3D-RISM or GIST to analyze initial hydration. Employ advanced sampling methods like Grand Canonical Non-equilibrium Candidate Monte Carlo (GCNCMC) to ensure the binding site is adequately hydrated, reducing hysteresis in results [21].

- Utilize Active Learning Workflows: Combine FEP with faster 3D-QSAR methods in an active learning loop. Use FEP on a subset of designs, then use QSAR to predict the larger set. Select promising molecules from the QSAR set for subsequent FEP calculations, iterating until convergence [21].

Performance Data and Method Selection

The following table summarizes the performance of various docking methodologies across critical dimensions, based on a comprehensive multi-dataset evaluation. This data can guide tool selection based on your primary objective [42].

Table 1: Multidimensional Performance Comparison of Docking Methods

| Method Category | Example Methods | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Interaction Recovery | Generalization to Novel Pockets | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | High | Very High (>94%) | High | Moderate | Reliability, production virtual screening |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | Very High (>70%) | Moderate | Moderate | Low to Moderate | Maximum pose accuracy when physical checks are applied |

| Regression-Based | KarmaDock, QuickBind | Low | Low | Low | Low | Fast, preliminary screening |

| Hybrid (AI Score + Search) | Interformer | High | High | High | High | Projects requiring a balance of accuracy and robustness |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimizing AlphaFold2 Structures for Virtual Screening

Objective: To generate a protein structure conformation from AlphaFold2 that is more amenable to ligand binding, thereby improving virtual screening performance [43].

Materials:

- AlphaFold2 protein structure prediction system.

- Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for the target protein.

- A set of known active ligands for the target.

- A molecular docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide SP).

- Computing cluster for parallel processing.

Procedure:

- MSA Modification: Create a series of modified MSAs by systematically introducing alanine substitutions at residues lining the predicted ligand-binding pocket.

- Structure Prediction: Run AlphaFold2 using each modified MSA to generate an ensemble of alternative protein conformations.

- Docking and Scoring: Dock a small set of known active and decoy compounds into each generated protein structure. Calculate an enrichment metric (e.g., EF1% or AUROC) for each structure.

- Genetic Algorithm Optimization:

- Initialization: Start with a population of different MSA mutation strategies.

- Evaluation: Score each mutant by the virtual screening enrichment of its resulting protein structure.

- Selection: Select the top-performing mutants for "reproduction."

- Crossover and Mutation: Create a new generation of mutants by combining (crossover) and randomly altering (mutation) the selected MSAs.

- Iteration: Repeat steps (b) to (d) for multiple generations until convergence is achieved.

- Final Model Selection: The protein structure derived from the highest-scoring MSA in the final generation is selected for the full-scale virtual screening campaign.

Visualization of Workflow:

Protocol: Collaborative Drug Design (CIDD) Workflow

Objective: To generate drug candidates that excel in both target binding affinity and drug-like properties by integrating 3D-SBDD models with Large Language Models (LLMs) [44].

Materials:

- A 3D-SBDD generative model (e.g., TargetDiff, Pocket2Mol).

- Access to a proficient LLM (e.g., GPT-4, specialized scientific LLMs).

- Protein target pocket structure.

- Molecular docking and property calculation software (e.g., for QED, SA, LogP).

Procedure:

- Initial Generation: Use the 3D-SBDD model to generate an initial set of ligand poses within the target protein pocket.

- Interaction Analysis: The LLM analyzes the generated poses to identify key molecular fragments responsible for crucial interactions (e.g., H-bonds, π-π stacking) with the protein.

- Design and Refinement: The LLM proposes modifications to the molecular structure to:

- Correct chemically unreasonable substructures (e.g., distorted rings).

- Improve drug-likeness metrics (e.g., QED, SA).

- Maintain or optimize the key interacting fragments identified in step 2.

- Reflection and Selection: The LLM evaluates the refined designs, highlighting strengths and weaknesses. This iterative cycle of design and reflection is repeated multiple times to produce a diverse set of candidate molecules.

- Final Evaluation: The resulting molecules are scored based on a balanced combination of docking score (affinity) and drug-likeness properties, and the top-ranking candidates are selected.

Visualization of Workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for SBDD Optimization

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| PoseBusters [42] | Validation Toolkit | Checks physical and chemical validity of docked poses. | Identifying steric clashes, bad bond lengths, and incorrect stereochemistry. |

| Open Force Field (OpenFF) [21] | Force Field | Provides accurate parameters for small molecules in molecular simulations. | Improving the reliability of FEP and MD simulations through better ligand description. |

| OMol25 Dataset [12] [11] | Training Dataset | Massive dataset of quantum chemical calculations for diverse molecules. | Training and benchmarking machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). |

| eSEN/UMA Models [12] | Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Provides DFT-level accuracy for energy calculations at a fraction of the cost. | Running highly accurate and scalable molecular dynamics simulations. |

| Glide SP [42] | Molecular Docking Software | Traditional physics-based docking with robust conformational search. | Producing physically plausible poses and reliable virtual screening hits. |

| AlphaFold2 [43] | Protein Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences. | Generating structural models for targets without experimental structures. |

| CIDD Framework [44] | AI Workflow | Integrates 3D-SBDD models with LLMs for molecular optimization. | Bridging the gap between high binding affinity and drug-likeness in generated molecules. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Under what circumstances should I question the results of my Coupled-Cluster calculation? You should critically evaluate your results when studying systems known for strong electron correlation, such as reaction transition states, bond-breaking processes, open-shell systems, or molecules with degenerate or near-degenerate electronic states (e.g., the ozone molecule or the permanganate anion). In these cases, standard single-reference methods like CCSD(T) can produce nonsensical results, including incorrect geometries or absurd dissociation pathways [45].

FAQ 2: What diagnostic tools can I use to assess the quality and reliability of my CCSD or CCSD(T) calculation? Several diagnostic tools are available:

- T1 Diagnostic: A simple measure proposed by Lee and Taylor. A high value (conventionally above

0.02) suggests significant "multireference character" and potential inaccuracies [45]. - Density Matrix Asymmetry Diagnostic: A newer measure that quantifies the non-Hermitian character of the one-particle reduced density matrix in truncated CC theory. A larger value indicates the wavefunction is farther from the exact Full-CI limit. This diagnostic provides information on both the difficulty of the problem and how well a specific CC method is performing [45].

FAQ 3: My research involves large organic molecules or reaction dynamics, and CCSD(T) is too computationally expensive. Are there any reliable alternatives? Yes, new AI-enhanced quantum mechanical methods are emerging. For instance, AIQM2 is a universal method designed for organic reaction simulations. It uses a Δ-learning approach, applying neural network corrections to a semi-empirical baseline (GFN2-xTB) to achieve accuracy approaching the gold-standard coupled-cluster level at a computational cost orders of magnitude lower than typical DFT. This makes it suitable for large-scale reaction dynamics studies that were previously prohibitive [46].

FAQ 4: Why are my calculated energies not size-extensive, and why does it matter? Size-extensivity is the property that the energy of a system scales correctly with the number of particles. Truncated Configuration Interaction (CI) methods are not size-extensive, meaning the error in the correlation energy increases as the system grows. In contrast, Coupled-Cluster theory is size-extensive, even in its truncated forms (like CCSD or CCSD(T)), which is one of its major advantages. If your energies are not size-extensive, you are likely using a non-size-extensive method like CI. This is critical for obtaining accurate thermodynamic limits and for meaningful comparisons between systems of different sizes [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unphysical Results or Convergence Failure

Problem Description:

A CCSD(T) calculation produces results that are physically implausible, such as predicting incorrect molecular symmetries (e.g., C_s instead of C_2v for ozone), spontaneous dissociation of multiple bonds, or a failure of the CC equations to converge [45].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Run a Diagnostic Check: Calculate the T1 diagnostic and the newer density matrix asymmetry diagnostic [45]. High values confirm that the system has strong correlation effects that the single-reference CC ansatz is struggling to capture.

- Verify Reference Wavefunction: Check if your Hartree-Fock reference is appropriate. A single Slater determinant might be a poor starting point for your system.

Resolution:

- Consider Multi-Reference Methods: For strongly correlated systems, transition to multi-reference methods like CASSCF or MRCI, which are designed to handle such problems.

- Use Diagnostics for Validation: If you must use CC theory, the diagnostics can help you identify when the results are not trustworthy. The density matrix asymmetry diagnostic, in particular, can show how the description improves or worsens with different levels of CC theory (e.g., CCSD vs. CCSD(T)) [45].

Issue: Prohibitive Computational Cost for Target System

Problem Description: The system size (number of atoms/electrons) or the basis set required for a CCSD(T) calculation makes the computation intractable with available resources [46] [48].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Assess System Size: Note that the computational cost of CCSD(T) scales with the seventh power of the system size (

N^7), making it very expensive for large molecules [45]. - Identify Critical Region: Determine if the chemically relevant part (e.g., a reaction site in an enzyme) is localized.

Resolution:

- Employ Embedding Schemes: Use methods like the ONIOM (Our own N-layered Integrated molecular Orbital and molecular Mechanics) scheme. In this approach, a high-level method like CCSD(T) is applied to a small, chemically active region, while a lower-level method (e.g., DFT or semi-empirical) describes the rest of the system [46].

- Explore Foundational AI Models: For organic systems, investigate the use of next-generation methods like AIQM2, which is available in open-source software such as

MLatom[46]. These methods can provide coupled-cluster level accuracy for reaction energies and barrier heights at a fraction of the cost. - Utilize Periodic CC Codes: For solid-state materials, use specialized periodic coupled-cluster codes that leverage symmetry and efficient algorithms [48].

Quantitative Data for Method Selection

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Quantum Chemistry Calculations

| Method | Typical Accuracy (kcal/mol) | Computational Scaling | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIQM2 | ~1 (Approaches CCSD(T)) [46] | Near semi-empirical cost [46] | Extremely fast, robust, good for dynamics & large systems [46] | Primarily for organic molecules (CHNO), new method [46] |

| CCSD(T) | ~1 (Chemical Accuracy) [48] | N^7 [45] |

"Gold Standard", highly accurate, systematic improvability [48] | Very high cost, fails for strong correlation [45] [48] |

| DFT | Varies widely (>>1) | N^3 - N^4 |

Workhorse, good cost/accuracy for many systems [46] [49] | Uncontrolled approximations, functional choice is critical [49] [48] |

| CCSD | 1-5 | N^6 [45] |

More affordable than CCSD(T), size-extensive [47] | Lacks higher-order excitations, less accurate than CCSD(T) |

| QCISD | 2-8 | N^6 |

An approximation to CCSD | Not as robust as CCSD, less commonly used |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Validating a Coupled-Cluster Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps to assess the reliability of a CCSD or CCSD(T) calculation.

1. Objective: To ensure that the results of a coupled-cluster computation are physically meaningful and not compromised by strong electron correlation effects.

2. Materials/Software Requirements:

- A quantum chemistry package capable of performing CCSD or CCSD(T) calculations with analytic gradients (e.g., CFOUR, NWChem, PySCF).

- The molecular geometry of interest.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Perform a CCSD Calculation. Run a standard CCSD energy and gradient calculation on your system.

- Step 2: Extract the T1 Diagnostic. From the output file, locate the value of the

T1diagnostic. A value greater than0.02is a common, though not infallible, indicator of potential multireference character [45]. - Step 3: Compute the One-Particle Density Matrix. If available in your software, request the calculation of the one-particle reduced density matrix (1PRDM) during the gradient calculation [45].

- Step 4: Calculate the Asymmetry Diagnostic. Compute the diagnostic value using the formula:

( \text{Diagnostic} = \frac{||D - D^T||F}{\sqrt{N{\text{electrons}}}} )

where

Dis the 1PRDM, ( D^T ) is its transpose, and ( || \cdot ||_F ) is the Frobenius norm. A larger value indicates a greater deviation from the exact, Hermitian limit [45]. - Step 5: Interpret Results. If both diagnostics are low, you can have higher confidence in your results. If they are high, consider using a higher-level CC theory (e.g., CCSDT) or a multi-reference method, and interpret the CCSD(T) results with extreme caution.

Protocol for High-Throughput Reaction Simulation using AIQM2

This protocol describes how to use the AIQM2 method for large-scale reaction dynamics simulations, as showcased in [46].

1. Objective: To efficiently simulate organic reaction mechanisms and obtain product distributions with near-CCSD(T) accuracy.

2. Materials/Software Requirements:

- The open-source software

MLatom(available via GitHub). - Access to the AIQM2 model within the Universal and Updatable AI-enhanced QM (UAIQM) foundational models library in

MLatom[46].

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Install and Configure MLatom. Follow the installation instructions on the

MLatomGitHub repository to set up the software and its dependencies, including the AIQM2 model [46]. - Step 2: Prepare Input Files. Prepare the input files containing the initial geometries of the reactants for the reaction of interest.

- Step 3: Set Up Reactive Dynamics. Use

MLatom's interface to configure a reactive molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using the AIQM2 potential energy surface (PES). - Step 4: Propagate Trajectories. Run the simulation to propagate thousands of trajectories in parallel. As reported, thousands of high-quality trajectories can be run overnight on 16 CPUs [46].

- Step 5: Analyze Output. Analyze the resulting trajectories to determine the final products, calculate the product distribution (branching ratios), and revise previous mechanisms, as demonstrated for the bifurcating pericyclic reaction in [46].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: CC Implementation Decision Tree

Diagram 2: CC Validation Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Computational "Reagents" for Coupled-Cluster and Beyond-DFT Calculations

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | A robust semi-empirical quantum mechanical method that serves as the fast baseline in the AIQM2 model for generating initial PES data [46]. |

| ANI Neural Networks | An ensemble of neural networks (part of AIQM2) that corrects the GFN2-xTB baseline energy towards coupled-cluster level accuracy [46]. |

| D4 Dispersion Correction | An empirical correction added to AIQM2 (for the ωB97X functional) to properly describe long-range noncovalent interactions [46]. |

| MLatom Software | An open-source computational platform that provides access to AIQM2 and other machine learning-enhanced quantum chemistry methods for reaction simulation [46]. |

| T1 Diagnostic | A simple scalar metric obtained from a CCSD calculation that helps diagnose multireference character and potential accuracy issues [45]. |

Lambda (Λ) Operator |

In coupled-cluster gradient theory, the de-excitation operator used to define the left-hand wavefunction, which is essential for calculating properties and density matrices [45]. |

Troubleshooting Common AI Workflow Failures

Molecular Optimization Convergence Issues

Problem: Molecular geometry optimizations fail to converge or yield structures that are not local minima (indicated by imaginary frequencies) [50].

| Problem Indicator | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization exceeds maximum step limit (e.g., 250 steps) [50] | Overly strict convergence criteria; Noisy potential energy surface; Inappropriate optimizer [50] | • Switch to a more robust optimizer (e.g., from geomeTRIC to Sella with internal coordinates) [50].• Increase maximum steps to 500 for difficult systems [50].• Relax convergence criteria (e.g., increase fmax from 0.01 eV/Å) [50]. |

| Optimized structure is a saddle point (has imaginary frequencies) [50] | Optimizer trapped in transition state; Insufficient optimization precision [50] | • Use an optimizer known for finding minima (e.g., Sella (internal) or L-BFGS) [50].• Perform frequency calculation post-optimization to verify minima [50].• For NNPs, ensure model training adequately covers the relevant conformational space. |

| Large hysteresis in free energy calculations [21] | Inconsistent hydration environment between simulation legs [21] | • Use techniques like 3D-RISM or GIST to analyze hydration [21].• Implement Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) steps to equilibrate water placement [21]. |

Poor Predictive Performance in AI Models

Problem: AI models for virtual screening or property prediction show poor accuracy or generalization [51] [52].

| Problem Indicator | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|