PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models: A Modern Paradigm for Identifying High-Quality Chemical Probes

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two predominant computational approaches in early drug discovery: the rule-based PAINS filters and the data-driven Bayesian models.

PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models: A Modern Paradigm for Identifying High-Quality Chemical Probes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two predominant computational approaches in early drug discovery: the rule-based PAINS filters and the data-driven Bayesian models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of each method, detailing their practical applications and workflows for validating chemical probes. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, such as mitigating the high false-positive rate of PAINS and improving Bayesian model interpretability. By presenting a head-to-head validation and discussing emerging trends like multi-endpoint modeling and explainable AI, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing these tools to improve the efficiency and success rate of probe discovery and development.

Chemical Probe Validation: Why PAINS Filters and Bayesian Models Are Essential

The pursuit of high-quality chemical probes—potent, selective, and cell-active small molecules that modulate protein function—represents a critical frontier in biomedical research and early drug discovery. These tools are essential for validating novel therapeutic targets and deconvoluting disease biology. This guide objectively compares two dominant methodological frameworks in chemical probe discovery: traditional PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) filters and emerging Bayesian computational models. The analysis is framed within the context of substantial public investment, notably from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the pervasive challenge of high attrition rates that plague the field. The strategic shift from reactive compound filtering to proactive, probability-driven discovery holds the potential to redefine the efficiency and success of probe and drug development.

The Probe Discovery Landscape: Investment, Goals, and Attrition

Major public and private sector initiatives underscore the immense strategic value and financial commitment required for probe development. The table below summarizes key global efforts and the challenging economic environment.

Table 1: Major Initiatives and Economic Context in Probe Discovery

| Initiative / Metric | Primary Focus | Key Outputs / Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Target 2035 [1] | Create pharmacological modulators for most human proteins by 2035. | Global open-science initiative; relies on partnerships like EUbOPEN. |

| EUbOPEN Consortium [1] | Develop openly available chemical tools for understudied targets (e.g., E3 ligases, SLCs). | Aims to deliver 100+ high-quality chemical probes and a chemogenomic library covering 1/3 of the druggable proteome. |

| NIH/NCI Funding (R01) [2] | Fund innovative research for novel small molecules in cancer. | Supports assay development, primary screening, and hit validation; projects can run for 3 years with budgets reflecting project needs. |

| Industry R&D Context [3] | Develop new drug candidates in a challenging economic landscape. | Phase 1 success rates plummeted to 6.7% in 2024 (from 10% a decade ago); R&D internal rate of return has fallen to 4.1%. |

The data reveals a stark contrast: while scientific ambition and public investment are high, the overall productivity of the biopharmaceutical R&D ecosystem is under significant strain. The success rate for drugs entering Phase 1 clinical trials has sharply declined, and the return on R&D investment is well below the cost of capital [3]. This underscores the critical need for more efficient and predictive discovery methodologies at the earliest stages, such as probe development, to improve the entire development pipeline.

Methodological Face-Off: PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models

The core challenge in probe discovery is distinguishing truly useful compounds from those that generate misleading results. The following table provides a detailed comparison of the two approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of PAINS Filters and Bayesian Models in Probe Discovery

| Feature | PAINS Filters | Bayesian Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Structural alert-based exclusion of compounds with known promiscuous or reactive motifs [4]. | Statistical inference integrating prior knowledge with new experimental data to update beliefs about compound behavior [5] [6] [7]. |

| Primary Function | Post-hoc filtering and triage of screening hits. | Prospective prediction and quantitative assessment of compound quality and reliability. |

| Key Inputs | 2D chemical structures of hit compounds. | Prior expectations (e.g., from historical HTS data), current sensory evidence (assay results), and their respective uncertainties [5] [6]. |

| Typical Workflow | 1. Run HTS assay.2. Identify preliminary hits.3. Filter hits against PAINS library.4. Manually investigate remaining hits. | 1. Define prior probabilities based on existing data.2. Collect new experimental data.3. Compute precision-weighted prediction errors.4. Update beliefs (posterior) iteratively [6] [7]. |

| Key Strength | Simple, fast, and readily implementable to flag common nuisance compounds [4]. | Provides a normative, probabilistic framework for learning under uncertainty; explains phenomena like placebo/nocebo and offset analgesia [6] [7]. |

| Main Limitation | Over-simplification; may discard useful scaffolds and lacks quantitative probabilistic output [4]. | Model complexity and computational cost; requires significant, well-structured data for training and validation. |

| Data Output | Binary classification (e.g., "PAINS" or "Not PAINS"). | Continuous probability scores (e.g., probability of success, precision of belief) [8]. |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Protocol for PAINS Identification in HTS: The standard methodology involves analyzing large-scale HTS data to identify compounds that hit frequently across multiple, unrelated assays. A foundational study analyzed 872 public HTS datasets to model frequent hitter behavior [4]. The core statistical model often involves a Binomial Survivor Function (BSF), which calculates the probability that a compound is active k times out of n trials given a background hit probability p [4]. Compounds with a BSF p-value exceeding a 99% confidence threshold are flagged as potential frequent hitters for further scrutiny [4].

Protocol for Bayesian Modeling of Pain Perception: Bayesian models have been empirically tested in psychophysical paradigms. In one study, a Nociceptive Predictive Processing (NPP) task was used [5]. Participants underwent a Pavlovian conditioning task where a visual cue was paired with a painful electrical cutaneous stimulus. Computational modeling using a Hierarchical Gaussian Filter (HGF) was then applied to the participants' response data. The HGF estimates the individual's relative weighting (ω) of prior beliefs versus sensory nociceptive input during perception, quantifying a top-down cognitive influence on pain [5].

A separate study on Offset Analgesia (OA)—the pain reduction after a sudden drop in noxious heat—contrasted a deterministic model with a recursive Bayesian integration model [6]. When high-frequency thermal noise was introduced, the Bayesian model was superior, showing how the brain filters out irrelevant noise to maintain stable pain perception, a process that can be formalized computationally [6].

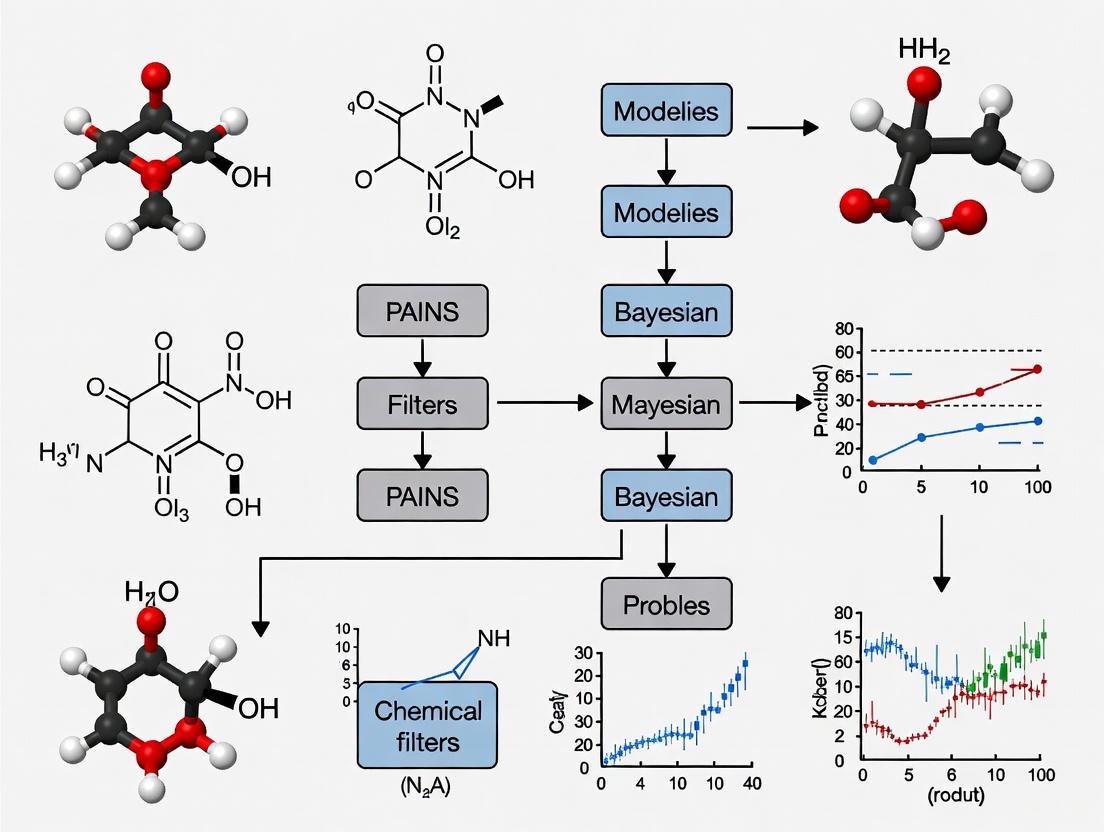

Visualizing the Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The diagrams below illustrate the logical workflow for PAINS identification and the theoretical signaling pathway for Bayesian pain perception.

PAINS Identification Workflow

Bayesian Inference in Pain Perception

Successful probe discovery relies on a suite of specialized tools and reagents. The following table details key resources for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Probe Discovery

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes | Highly characterized, potent, and selective small molecules for target validation. | EUbOPEN Donated Chemical Probes Project: peer-reviewed probes available upon request [1]. |

| Chemogenomic (CG) Libraries | Collections of well-annotated compounds with overlapping target profiles for target deconvolution. | EUbOPEN CG library covers one-third of the druggable proteome; an alternative to highly selective probes [1]. |

| Negative Control Compounds | Structurally similar but inactive analogs to confirm that observed phenotypes are target-mediated. | Provided alongside chemical probes from consortia like EUbOPEN to ensure experimental rigor [1]. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assays | In vitro or cell-based assays configured to rapidly test thousands of compounds for activity. | NIH/NCI funding supports development of innovative HTS assays for cancer target discovery [2]. |

| Public Bioactivity Databases | Repositories of compound-target interaction data for building prior distributions in Bayesian models. | Foundational for analyzing frequent hitter behavior and training computational models [4]. |

The comparison reveals that PAINS filters and Bayesian models are not simple replacements for one another but represent different evolutionary stages in chemical probe discovery. PAINS filters offer a crucial, if sometimes blunt, first line of defense against assay artifacts. However, the future of the field lies in embracing more sophisticated, quantitative frameworks that actively manage uncertainty. Bayesian models, supported by growing empirical evidence from computational neuroscience, provide a powerful paradigm for improving the predictive probability of success [8]. Integrating the heuristic power of PAINS knowledge as a prior within a dynamic Bayesian learning system offers a promising path forward. For researchers, navigating the high stakes of probe discovery will increasingly require a hybrid expertise—deep chemical and biological knowledge complemented by computational literacy—to leverage these tools effectively, mitigate attrition, and maximize the return on multimillion-dollar public and private investments.

In high-throughput screening (HTS), a significant challenge is the occurrence of false-positive compounds, particularly frequent hitters (FHs)—molecules that generate positive readouts across multiple unrelated biological assays. Among these, Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) represent a specific class of compounds that interfere with assay technologies through various undesirable mechanisms, leading to false indications of target engagement. Initially proposed in 2010, the PAINS filtering approach utilizes 480 substructural filters to identify and remove these problematic compounds from screening libraries. However, the scientific community has increasingly recognized limitations in the PAINS approach, including unknown specific mechanisms for most alerts, unclear validation schemes, and a high rate of false positives that may inadvertently eliminate viable chemical matter. Concurrently, Bayesian models have emerged as a powerful computational alternative, offering a probabilistic framework for identifying promiscuous binders by integrating multiple data sources and quantifying uncertainty. This guide provides an objective comparison of these divergent approaches, presenting experimental data and methodological details to inform researchers' selection of tools for chemical probe research.

Performance Comparison: PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Detection Capability for Different Interference Mechanisms

| Interference Mechanism | PAINS Sensitivity | PAINS Precision | Bayesian Model (ML) ROC AUC | Assessment Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Aggregators | <0.10 | 0.14 | 0.70 (AlphaScreen) | Large benchmark (>600,000 compounds) [9] |

| Blue/Green Fluorescent Compounds | <0.10 | 0.11 | 0.62 (FRET) | Large benchmark (>600,000 compounds) [9] |

| Luciferase Inhibitors | <0.10 | 0.08 | 0.57 (TR-FRET) | Large benchmark (>600,000 compounds) [9] |

| Reactive Compounds | <0.10 | 0.11 | 0.70 (AlphaScreen) | Large benchmark (>600,000 compounds) [9] |

| Overall Balanced Accuracy | <0.510 | N/A | 0.96 (Hit Dexter 2.0) | Benchmarking study [9] |

Table 2: Practical Applicability and Limitations

| Characteristic | PAINS Filters | Bayesian/Machine Learning Models |

|---|---|---|

| Coverage of FHs | Neglects >90% of FHs [9] | Wider coverage of interference mechanisms [10] |

| Applicability to Novel Compounds | Limited to known substructures | Can predict promiscuity of untested compounds [10] |

| Mechanism Explanation | Specific mechanisms remain unknown for most alerts [9] | Clear prediction endpoints and features [9] |

| Dependence on Assay Technology | Derived from AlphaScreen data, limited applicability to other technologies [10] | Can be trained on multiple technology platforms [10] |

| False Positive Rate | 97% of PAINS-flagged PubChem compounds are infrequent hitters in PPI assays [9] | Reduced false positives through multi-parameter assessment |

Key Performance Insights

Limited Detection Capability: PAINS filters demonstrate sensitivity values below 0.10 across all major interference mechanisms, indicating they miss more than 90% of true frequent hitters [9].

Technology Dependency: PAINS filters show slightly better performance for AlphaScreen technology (9% of CIATs correctly predicted) compared to FRET and TR-FRET (1.5% of CIATs correctly predicted), reflecting their development basis in AlphaScreen data [10].

Bayesian Advantages: Machine learning models employing random forest classification demonstrate superior performance with ROC AUC values of 0.70, 0.62, and 0.57 for AlphaScreen, FRET, and TR-FRET technologies, respectively, while achieving significantly higher balanced accuracy [10].

Scaffold vs. Substructure Focus: Unlike PAINS' substructure approach, Bayesian methods can incorporate scaffold-based promiscuity assessment similar to BadApple, which assigns promiscuity scores based on molecular scaffolds derived from screening results [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

PAINS Validation Experimental Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the real-world performance of PAINS filters against experimentally confirmed technology interference compounds.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound libraries from HTS databases (e.g., AstraZeneca in-house database)

- AlphaScreen, FRET, and TR-FRET assay platforms

- Artefact (counter-screen) assays containing all assay components except target protein

Methodology:

- Collect primary single-concentration HTS data from three technologies (AlphaScreen, FRET, TR-FRET)

- For compounds active in primary assays, obtain corresponding artefact assay results

- Classify compounds as CIATs (Compounds Interfering with Assay Technology) if active in artefact assay, or NCIATs (non-CIATs) if inactive

- Apply PAINS substructural filters (480 filters) to the classified compound sets

- Calculate performance metrics (sensitivity, precision, accuracy) by comparing PAINS alerts with experimental CIAT classification [10]

Key Findings from Implementation:

- PAINS filters correctly identified only 9% of CIATs for AlphaScreen and 1.5% for FRET/TR-FRET technologies

- Very low precision values (0.14 for aggregators, 0.11 for fluorescent compounds and reactive compounds, 0.08 for luciferase inhibitors)

- Balanced accuracy values below 0.510 across all interference mechanisms [9]

Bayesian Machine Learning Model Protocol

Objective: To develop a predictive model for assay technology interference from molecular structures using artefact assay data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Curated dataset of known CIATs and non-CIATs from historical artefact assays

- 2D structural descriptors for all compounds

- Random forest classification algorithm

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Gather results from primary HTS campaigns and corresponding artefact assays for AlphaScreen, FRET, and TR-FRET technologies

- Data Preparation: Subject initial data to rigorous multistep preparation scheme to create high-quality benchmark dataset

- Model Training: Train random forest classifier on known CIATs and non-CIATs using 2D structural descriptors as features

- Performance Validation: Evaluate model using ROC AUC, sensitivity, and precision metrics

- Comparative Analysis: Compare performance against PAINS filters and BSF (Binomial Survivor Function) methods [10]

Key Findings from Implementation:

- Successful prediction of CIATs for existing and novel compounds with ROC AUC values of 0.70 (AlphaScreen), 0.62 (FRET), and 0.57 (TR-FRET)

- Provides complementary and wider set of predicted CIATs compared to structure-independent BSF model and PAINS filters

- Demonstrates that well-curated datasets can provide powerful predictive models despite relatively small size [10]

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Relationships

PAINS Filtering Workflow and Limitations

Bayesian Inference Model for Pain Perception

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for PAINS and Bayesian Model Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Assays | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay Technologies | AlphaScreen | Bead-based proximity assay for detecting molecular interactions | PAINS filters derived from this technology; high false positive rate in other technologies [10] |

| FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) | Distance-dependent energy transfer between fluorophores | PAINS filters show low accuracy (1.5% CIATs correctly predicted) [10] | |

| TR-FRET (Time-Resolved FRET) | FRET with time-gated detection to reduce background | PAINS filters show low accuracy (1.5% CIATs correctly predicted) [10] | |

| Computational Tools | PAINS Substructure Filters | 480 substructural filters for compound triage | Limited by unknown mechanisms and high false positive rates [9] |

| Random Forest Classification | Machine learning approach for CIAT prediction | ROC AUC values of 0.70 (AlphaScreen), 0.62 (FRET), 0.57 (TR-FRET) [10] | |

| Binomial Survivor Function (BSF) | Statistical assessment of screening results | Structure-independent; cannot predict novel compounds [10] | |

| BadApple | Scaffold-based promiscuity scoring | Derived from screening results rather than substructure patterns [9] | |

| Experimental Validation | Artefact (Counter-Screen) Assays | Contains all assay components except target protein | Gold standard for experimental confirmation of technology interference [10] |

| Hit Dexter 2.0 | Frequent-hitter prediction platform | Covers both primary and confirmatory assays (MCC=0.64, ROC AUC=0.96) [9] |

The comparative analysis reveals fundamental limitations in the PAINS filtering approach, including inadequate detection capability (<10% sensitivity across interference mechanisms), technology specificity, and high false positive rates. Bayesian and machine learning models demonstrate superior performance with higher accuracy and broader applicability, though they require well-curated training data. For rigorous chemical probe research, we recommend:

Moving Beyond Exclusive PAINS Reliance: PAINS filters should not be used as a standalone triage tool due to poor detection capability and high false positive rates.

Adopting Bayesian Approaches: Implement machine learning models trained on artefact assay data for improved CIAT prediction, particularly for novel compounds.

Experimental Validation: Maintain artefact assays as the gold standard for confirming technology interference mechanisms.

Technology-Specific Considerations: Select computational tools appropriate for specific assay technologies, recognizing that performance varies significantly across platforms.

The integration of robust computational approaches with experimental validation represents the most promising path forward for reliable identification of promiscuous binders and technology interference compounds in drug discovery.

The discovery of high-quality chemical probes—compounds used to explore biological systems—is fundamental to chemical biology and drug development. Within this field, the problem of false-positive hits, or compounds that appear active due to assay interference rather than true biological activity, presents a significant challenge. To address this, the research community developed a rule-based filtering approach centered on expert-curated structural alerts known as PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds). These filters were derived from the analysis of compounds that showed activity across multiple, unrelated biological assays (frequent-hitter behavior) in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) campaigns. The core premise is that certain substructural motifs are inherently prone to cause interference through various mechanisms, such as covalent protein reactivity, fluorescence, redox cycling, or metal chelation [11]. This guide objectively examines the performance, utility, and limitations of the PAINS filtering approach, placing it within the broader context of alternative methods, such as Bayesian models, for validating chemical probes.

Performance Comparison: PAINS Filters Versus Alternative Methods

A critical assessment of PAINS filters requires a direct comparison of their performance against other computational triage methods. Independent, large-scale benchmarking studies reveal specific strengths and limitations of the rule-based approach.

Table 1: Benchmarking PAINS Filter Performance Against Other Methods

| Method | Basis of Prediction | Reported Sensitivity for FHs | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAINS Filters | 480 expert-curated substructural alerts [9] | <0.10 (misses >90% of FHs) [9] | Easy, fast application; no assay data required [12] | High false-negative rate; limited mechanistic insight [9] |

| Bayesian Models | Machine learning on historical screening data and molecular descriptors [13] | Accuracy comparable to other drug-likeness measures [13] | Can learn from expert intuition; probabilistic output [13] | Requires a training dataset; model interpretability can be low |

| Hit Dexter 2.0 | Machine learning on molecular fingerprints of PubChem compounds [10] | MCC of 0.64, ROC AUC of 0.96 [10] | High accuracy for promiscuity prediction; uses public data [10] | Limited to previously tested compounds and chemical space |

| Random Forest CIAT Model | Machine learning on 2D descriptors from counter-screen data [10] | ROC AUC: 0.70 (AlphaScreen), 0.62 (FRET), 0.57 (TR-FRET) [10] | Specifically trained on experimental interference data [10] | Performance varies by assay technology |

Quantitative data demonstrates that PAINS filters exhibit significant performance gaps. A benchmark of over 600,000 compounds across six common interference mechanisms showed that PAINS had an average balanced accuracy of less than 0.510 and a sensitivity below 0.10, meaning it failed to identify over 90% of frequent hitters [9]. Furthermore, when used to identify technology-specific interferers (CIATs), PAINS filters correctly identified only 9% of AlphaScreen CIATs and a mere 1.5% of FRET and TR-FRET CIATs [10]. This confirms that PAINS' applicability is narrow and should not be considered a comprehensive solution for all assay types.

Experimental Evidence and Validation Protocols

The initial development and subsequent validation of PAINS filters relied on specific experimental setups and data analysis techniques. Understanding these protocols is essential for contextualizing the performance data.

Original PAINS Derivation Protocol

The original set of 480 PAINS alerts was derived from a proprietary library of approximately 93,000 compounds tested in six HTS campaigns. The core experimental parameters were:

- Assay Technology: AlphaScreen detection technology.

- Biological Target: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) inhibition assays.

- Compound Concentration: High concentrations of 25–50 μM in primary screens.

- Analysis Method: Compounds active in at least two out of six assays were classified as PAINS. Substructural features common to these frequent hitters were identified and codified as SMARTS or SLN notations for use as filters [14] [10].

A critical limitation noted in subsequent analyses is that 68% (328) of these alerts were derived from four or fewer compounds, with over 30% (190 alerts) based on a single compound only, questioning their statistical robustness and general applicability [14].

Key Validation Studies and Findings

Independent researchers have performed large-scale analyses to test the validity of PAINS filters using public data. The following workflow summarizes a typical validation study design:

Diagram 1: Validation Study Workflow

One seminal study applied this workflow to six PubChem AlphaScreen assays measuring PPI inhibition. The results were revealing:

- High False-Negative Rate: Of the 153,339 unique compounds analyzed, only 23% of the true Frequent Hitters (902 compounds) contained PAINS alerts; the remaining 77% were not flagged [14].

- High False-Positive Rate: Strikingly, 97% of all compounds containing PAINS alerts were, in fact, Infrequent Hitters, meaning the vast majority of flagged compounds were not actual pan-assay interferers [14].

- Presence in Inactive Compounds: The study also found 109 different PAINS alerts in 3,570 compounds classified as Dark Chemical Matter—molecules extensively tested but consistently inactive—further challenging the association of these alerts with interference [14].

- Presence in Drugs: Eighty-seven FDA-approved drugs contain PAINS alerts, demonstrating that these structural motifs can be part of viable, specific therapeutics and should not be automatically discarded [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Researchers working in this field rely on a combination of software tools, datasets, and physical compound libraries.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for PAINS and Probe Validation

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Use Case in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PAINS Filter SMARTS | The set of 480 substructural patterns defined in a computable format [15]. | Integrated into cheminformatics pipelines (e.g., CDD Vault, StarDrop, ChEMBL) to flag potential interferers during virtual screening [15] [12]. |

| rd_filters.py Script | An open-source Python script that applies multiple structural alert sets, including PAINS, to compound libraries [12]. | Enables rapid, customizable filtering of large chemical datasets, providing pass/fail results and detailed reporting on which alerts were triggered. |

| Enamine PAINS Library | A commercially available library of 320 diverse compounds containing PAINS alerts [16]. | Used for HTS assay development and validation to intentionally test for and characterize interference in a specific assay system. |

| Orthogonal Assays | A different assay technology (e.g., SPR, cell-based) used to confirm activity from primary HTS [14] [11]. | Critical experimental control to confirm that a compound's activity is target-specific and not an artifact of the primary assay's detection technology. |

| Counter-Screen (Artefact) Assays | An assay containing all components of the primary HTS except the biological target [10]. | Used to experimentally identify technology-interfering compounds (CIATs) by measuring signal in the absence of the target. |

PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models: A Comparative Pathway

The choice between a rule-based system like PAINS and a probabilistic machine learning approach like a Bayesian model represents a fundamental methodological dichotomy in chemical probe research. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and key differentiators between these two approaches.

Diagram 2: PAINS vs. Bayesian Models

While PAINS filters offer a simple, rapid first pass, Bayesian models provide a complementary approach. Bayesian models can be trained to predict the "desirability" of a chemical probe based on molecular properties and even learn from the subjective evaluations of expert medicinal chemists [13]. This allows for a more nuanced, probabilistic assessment compared to the binary output of PAINS filters.

The evidence indicates that PAINS filters are a useful but deeply flawed tool. Their high rates of false positives and negatives, combined with their narrow derivation from a specific assay technology, mean they lack the reliability for use as a standalone triage method [14] [9] [10]. The scientific consensus, as reflected in the literature and guidelines from major journals, is moving away from blind application of PAINS filters. The recommended best practice is to use these filters as an initial warning system, not a final arbiter. Conclusions about compound interference should only be drawn after conducting orthogonal experiments, such as counter-screens, dose-response analysis, and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies, to firmly establish the validity and specificity of a chemical probe [14] [11]. In the context of chemical probe research, a Bayesian or other machine learning model may offer a more sophisticated and accurate complementary approach, but the ultimate validation must always be rigorous experimental confirmation.

The discovery of high-quality chemical probes—compounds that selectively modulate a biological target to investigate its function—is a cornerstone of chemical biology and drug development. This field faces a significant challenge: efficiently distinguishing true, progressable hits from nuisance compounds that masquerade as active agents in assays. Two computational philosophies have emerged to address this problem: the rule-based Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters and the data-driven Bayesian models. PAINS filters rely on predefined structural alerts to identify compounds likely to cause assay interference, offering a rapid, binary screening tool [17]. In contrast, Bayesian models provide a probabilistic framework that learns from multifaceted experimental data to predict bioactivity and optimize experimental design [18] [19]. This guide objectively compares the performance, methodologies, and applications of these two approaches, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to inform their choice of predictive tools.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The Bayesian Framework for Drug Discovery

Bayesian models in cheminformatics are built on the principle of updating prior beliefs with new experimental evidence to arrive at a posterior probability that reflects the most current state of knowledge. This framework is exceptionally adaptable, allowing for the integration of diverse data types, from chemical structures to complex phenotypic readouts.

- Mechanism: These models use machine learning to correlate molecular features (e.g., structural fingerprints, physicochemical properties) with biological outcomes (e.g., efficacy, cytotoxicity). The model calculates a Bayesian score, where a more positive value indicates a higher probability of a desired activity, such as target inhibition or low cytotoxicity [18].

- Model Variants: A key advancement is the development of dual-event Bayesian models. Unlike single-event models that predict only bioactivity, dual-event models simultaneously evaluate multiple endpoints, such as antitubercular activity and mammalian cell cytotoxicity. This provides a direct readout on a compound's selectivity index, a critical parameter for a useful chemical probe [18].

The PAINS Filtering Paradigm

PAINS filters represent a knowledge-based, binary approach to hit triage. They were derived from empirical observation of chemotypes that frequently appeared as hits in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns, particularly in assays measuring protein-protein interaction inhibition [17].

- Mechanism: PAINS are defined by substructural motifs believed to encode for behaviors that lead to assay interference, such as chemical reactivity, fluorescence, redox activity, or colloidal aggregation [17] [9]. Electronic filters screen compound libraries to flag any structures containing these motifs.

- Inherent Limitations: The utility of PAINS is limited by their origin. They were defined from a specific, pre-filtered library of about 100,000 compounds tested primarily in one assay technology (AlphaScreen) [17]. Consequently, they are not comprehensive and may fail to identify nuisance compounds with interference mechanisms absent from the original training set. Furthermore, they can incorrectly flag structurally complex natural products or approved drugs that contain a PAINS alert but are bona fide, progressable compounds [17].

Visualizing the Workflows

The fundamental difference between the two approaches is their operational workflow: one is a dynamic, learning system, while the other is a static filter.

Performance Comparison: Bayesian Models vs. PAINS Filters

A critical comparison of these approaches based on experimental data reveals stark differences in predictive accuracy, utility, and applicability.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Bayesian Models and PAINS Filters

| Performance Metric | Bayesian Models | PAINS Filters |

|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate (Prospective Validation) | 14% (Novel antitubercular compounds from commercial library) [18] | Not designed for hit identification; designed for nuisance compound removal. |

| Ability to Predict Novel Scaffolds | Yes. Capable of "scaffold hopping" by integrating high-level biological signatures beyond simple chemical structure [20]. | No. Inherently tied to predefined chemical substructures, limiting novelty [17]. |

| Validation Against Known Mechanisms | High. Dual-event models successfully identify compounds with desired bioactivity and low cytotoxicity, a key probe quality [18]. | Low. A benchmark of >600,000 compounds showed PAINS had poor precision and sensitivity (<0.10) for identifying compounds with known interference mechanisms (aggregators, fluorescers) [9]. |

| Basis for Prediction | Probabilistic score based on multi-factorial data integration. | Binary (pass/fail) based on substructure presence. |

| Adaptability & Learning | Continuously improves with new data. | Static; requires manual updating of alert definitions. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Building and Validating a Dual-Event Bayesian Model

This protocol is adapted from a study that led to the discovery of novel antitubercular hits [18].

Data Curation:

- Source: Gather large-scale public HTS data containing both active and inactive compounds.

- Endpoint Definition: For a dual-event model, define two primary endpoints. For example:

- Event 1 (Efficacy): IC90 for growth inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) < 10 μg/mL.

- Event 2 (Safety): Selectivity Index (SI = CC50 / IC90) > 10 in mammalian Vero cells.

- Labeling: Label compounds as "active" if they meet both criteria, and "inactive" otherwise.

Model Training:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular fingerprints and descriptors for all compounds in the training set.

- Algorithm: Use a Bayesian machine learning algorithm to build a model that distinguishes actives from inactives based on their molecular features. The model outputs a score indicating the probability of a compound being active.

- Validation: Perform leave-one-out cross-validation to assess model performance, typically reported as a Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) value. A perfect model has an ROC of 1 [18].

Prospective Screening:

- Virtual Screening: Apply the trained model to a new, unseen commercial library (e.g., >25,000 compounds from Asinex). Rank all compounds by their Bayesian score.

- Compound Selection: Purchase the top-scoring compounds (e.g., top 100) for experimental testing.

Experimental Validation:

- Primary Assay: Test selected compounds for the primary efficacy endpoint (e.g., Mtb growth inhibition).

- Counter-Screen: Test active compounds for the secondary safety endpoint (e.g., cytotoxicity in Vero cells).

- Hit Confirmation: Confirm actives through dose-response experiments and resynthesis of the compound to rule out impurities.

Protocol: Implementing PAINS Filtering in Hit Triage

This protocol outlines the typical use of PAINS filters, as described in critical assessments of the method [17] [9].

Filter Selection:

- Obtain a set of PAINS substructure alerts (e.g., the original 480 alerts defined by Baell et al.).

- Implement the filters using a cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., Scopy or other KNIME/CDK pipelines).

Library Processing:

- Screen the entire list of hit compounds from an HTS campaign against the PAINS substructure alerts.

- Flag any compound that contains one or more of the defined nuisance motifs.

Hit Triage:

- Exclusion or Scrutiny: Either automatically remove all flagged compounds from further consideration or subject them to rigorous additional testing.

- Contextual Evaluation: If possible, consider the assay technology. Some PAINS alerts are specific to certain assay formats (e.g., AlphaScreen), and the compound may not interfere in the assay used [17].

Limitation Acknowledgement:

- Recognize that PAINS filters are not comprehensive and may yield both false positives (flagging useful compounds) and false negatives (missing true nuisance compounds) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The effective application of these computational tools relies on access to high-quality data, software, and compound libraries.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Predictive Modeling

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Public HTS Data Repositories (e.g., PubChem BioAssay, ChEMBL) | Provides large-scale bioactivity data essential for training and validating Bayesian models [20]. | Foundational for data-driven approaches. |

| Commercial Compound Libraries (e.g., Asinex, ZINC) | Large collections of purchasable small molecules used for prospective virtual screening and experimental validation [18]. | Critical for testing model predictions. |

| Bayesian Machine Learning Software (e.g., Scopy, in-house pipelines) | Software that implements Bayesian algorithms to build classification models from chemical and biological data. | Core engine for model development. |

| PAINS Substructure Alerts | The defined set of SMARTS patterns or structural queries used to identify potential nuisance compounds. | The foundational rule set for PAINS filtering. |

| Cytotoxicity Assay Kits (e.g., Vero cell viability assays) | Provides experimental data on mammalian cell cytotoxicity, a key endpoint for dual-event Bayesian models [18]. | Essential for experimental validation of model predictions on compound safety. |

The experimental data and comparative analysis presented in this guide lead to a clear conclusion: while PAINS filters serve as a rapid, initial warning system, their static and simplistic nature limits their reliability as a standalone tool for identifying high-quality chemical probes. The high false-positive and false-negative rates, combined with an inability to predict novel chemotypes, render them a blunt instrument [9]. In contrast, Bayesian models offer a sophisticated, dynamic, and data-driven framework. Their demonstrated ability to prospectively identify novel, potent, and selective hits—with hit rates far exceeding typical HTS—establishes them as a superior predictive learning tool for chemical probe research [18] [20].

The future of predictive learning in this field lies in the continued expansion of Bayesian approaches. This includes integrating even more diverse data types (e.g., gene expression, proteomics) and applying Bayesian optimal experimental design (BOED) to strategically plan experiments that most efficiently reduce uncertainty in model parameters and accelerate the discovery of validated chemical probes [19].

In the critical field of chemical probe research, the choice between static rule-based systems and self-improving, evidence-driven algorithms is pivotal for generating reliable, translatable data. This guide objectively compares the performance of Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters—a prime example of a static rule-based system—with Bayesian models that exemplify self-improving, evidence-driven algorithms. The analysis, grounded in experimental data and systematic reviews, reveals a clear performance differential: while PAINS filters offer initial simplicity, they are hampered by high false-positive rates and an inability to adapt, whereas Bayesian models provide a nuanced, probabilistic framework that continuously refines its understanding, leading to more robust target validation and hit selection.

Theoretical Foundations & Core Mechanisms

Static Rule-Based Systems: The PAINS Filter Paradigm

Static rule-based systems operate on a foundation of predefined, human-expert-derived logic. In the context of chemical probes, PAINS filters represent a classic example.

- Core Mechanism: PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) comprises 480 substructural filters designed to identify compounds likely to generate false-positive results in high-throughput screening (HTS) assays [9]. The system functions on "if-then" rules; if a compound's structure matches a predefined problematic substructure, it is flagged as a potential frequent hitter [21] [22].

- Knowledge Representation: The system's knowledge is explicitly encoded and fixed at the time of creation. It does not learn from new data or assay results post-deployment. Its operation is deterministic—the same input (chemical structure) will always produce the same output (pass/fail flag) [21] [22].

- Objective: To provide a rapid, upfront screening tool for removing promiscuous compounds from screening libraries, thereby saving resources [9].

Self-Improving Algorithms: The Bayesian Model Framework

Self-improving, evidence-driven algorithms, such as Bayesian models, are grounded in probabilistic learning and continuous updating of beliefs based on incoming data.

- Core Mechanism: Bayesian models treat learning as a process of "statistically optimal updating of predictions based on noisy sensory input" [6]. In chemical biology, this translates to a computational framework that combines prior knowledge (e.g., existing bioactivity data) with new experimental evidence (e.g., HTS dose-response data) to form a continuously refined posterior understanding of a chemical's properties [23] [7].

- Knowledge Representation: Knowledge is represented probabilistically within model parameters. The model inherently quantifies uncertainty and "weights" the reliability of different information sources (e.g., prior beliefs vs. new observations) [6] [23]. This process is fundamentally adaptive.

- Objective: To move beyond simple binary flags and enable a nuanced, quantitative prediction of chemical behavior, such as full dose-response curves and activity-relevant chemical distances, even for unscreened compounds [23].

The logical relationship and core differences between these two approaches are summarized in the diagram below.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data & Benchmarks

Direct comparisons and individual performance benchmarks reveal significant differences in the capabilities and limitations of these two approaches.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of PAINS Filters and Bayesian Models

| Performance Metric | PAINS Filters (Static Rules) | Bayesian Models (Self-Improving) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Accuracy (Balanced Accuracy) | < 0.510 for various interference mechanisms [9] | Superior simulation performance in distance learning and prediction [23] |

| Sensitivity (Coverage) | < 10% (Over 90% of frequent hitters missed) [9] | Modest to large predictive gains over existing methods [23] |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Incapable; provides binary output without confidence metrics [9] [22] | Core functionality; provides full probabilistic predictions and uncertainty quantification [23] [7] |

| Adaptability to New Data | None; requires manual rule modification by experts [21] [9] | Continuous and automatic updating of beliefs with new evidence [6] [23] |

| Real-World Best-Practice Adoption | N/A (Widely used but with known limitations) [9] | Only ~4% of studies use orthogonal evidence-driven approaches [24] |

Key Experimental Insights

- Limitations of PAINS Filters: A large-scale benchmark study evaluating PAINS against over 600,000 compounds with six defined false-positive mechanisms (e.g., colloidal aggregators, fluorescent compounds) found its performance "disqualified," with low sensitivity and precision [9]. The study concluded that PAINS is not suitable for screening all types of false positives and that many approved drugs contain PAINS alerts, highlighting the risk of erroneously discarding valuable compounds [9].

- Capabilities of Bayesian Models: The Bayesian partially Supervised Sparse and Smooth Factor Analysis (BS3FA) model demonstrates the power of the self-improving approach. It learns a "toxicity-relevant" distance between chemicals by integrating chemical structure (

x_i) and toxicological dose-response data (y_i) [23]. This allows for superior prediction of dose-response profiles for unscreened chemicals based on structure alone, moving beyond simplistic binary classification [23].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Benchmarking a Static Rule-Based System (PAINS)

This protocol is derived from the methodology used to evaluate the PAINS filter [9].

- Data Set Curation:

- Source a large and diverse benchmark data set of chemical compounds (e.g., >600,000 compounds) from public databases like ZINC, ChEMBL, and PubChem Bioassay.

- Annotate compounds based on confirmed interference mechanisms (e.g., colloidal aggregators, luciferase inhibitors, reactive compounds, fluorescent compounds). Include a set of non-interfering compounds as a negative control.

- Rule Application:

- Implement the PAINS substructural filters using a cheminformatics library (e.g., the Scopy library was used in the benchmark study).

- Screen the entire benchmark data set against the 480 PAINS rules.

- Performance Calculation:

- Generate a confusion matrix by comparing PAINS flags against the annotated ground-truth labels.

- Calculate key metrics: Sensitivity (true positive rate), Precision (positive predictive value), and Balanced Accuracy.

Protocol for a Self-Improving Bayesian Model (BS3FA)

This protocol outlines the workflow for the BS3FA model as described in the research [23].

- Data Integration and Preprocessing:

- Input Data 1: Collect chemical structure data (e.g., SMILES strings) and process them into numerical molecular descriptors (e.g., using Mold2 software to generate 777 descriptors).

- Input Data 2: Obtain sparse, noisy dose-response data from high-throughput screening (HTS) programs like the EPA's ToxCast.

- Model Formulation and Training:

- The BS3FA model assumes that variation in molecular features (

x_i) is driven by two sets of latent factors:F_shared: Latent factors that drive variation in both the molecular structure and the toxicological response (the "toxicity-relevant" space).F_x-specific: Latent factors that drive variation only in the molecular structure and are irrelevant to toxicity.

- The model is trained using Bayesian inference to learn these latent factors and their relationships to the observed structure and activity data.

- The BS3FA model assumes that variation in molecular features (

- Prediction and Inference:

- Distance Learning: Calculate an activity-relevant distance between chemicals based on their proximity in the learned

F_sharedlatent space. - Dose-Response Prediction: For a new, unscreened chemical, embed its molecular structure into the

F_sharedspace and project this to predict its full, unobserved dose-response curve, complete with uncertainty estimates.

- Distance Learning: Calculate an activity-relevant distance between chemicals based on their proximity in the learned

The experimental workflow for the Bayesian approach, integrating multiple data sources for continuous learning, is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The effective application of these computational approaches relies on access to high-quality data and tools. The following table details essential resources for chemical probe research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Chemical Probe Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probes Portal [25] [26] | Expert-Curated Resource | Provides community-reviewed assessments and recommendations for specific chemical probes, highlighting optimal ones and outdated tools to avoid. | Relies on manual expert input; coverage can be limited for some protein families. Best used alongside data-driven resources. |

| Probe Miner [26] [24] | Computational, Data-Driven Resource | Offers an objective, quantitative ranking of small molecules based on statistical analysis of large-scale bioactivity data. | Comprehensive and frequently updated, but rankings may require chemical biology expertise to interpret fully. |

| ToxCast Database [23] | Bioactivity Data Repository | Provides a vast database of high-throughput screening (HTS) results for thousands of chemicals across hundreds of assay endpoints, used for training predictive models. | Data can be sparse and noisy; requires computational processing for many applications. |

| High-Quality Chemical Probe (e.g., (+)-JQ1) [25] | Physical Research Tool | A potent, selective, and well-characterized small molecule used to inhibit a specific protein and study its function in cells or organisms. | Must be used at recommended concentrations (typically <1 μM) to maintain selectivity. Requires use of a matched inactive control and/or an orthogonal probe [24]. |

| Matched Inactive Control Compound [25] [24] | Physical Research Control | A structurally similar but target-inactive analog of the chemical probe. Serves as a critical negative control to confirm that observed phenotypes are due to target inhibition. | Not always available for every probe. Its use is a key criterion for best-practice research. |

The evidence demonstrates a compelling case for the transition from static, rule-based systems to dynamic, evidence-driven algorithms in chemical probe research and early drug discovery. While PAINS filters offer a quick, initial check, their high false-negative rate, lack of nuance, and static nature limit their reliability as a standalone tool [9]. In contrast, Bayesian models and similar self-improving algorithms embrace the complexity and uncertainty inherent in biological systems. Their ability to integrate diverse data streams, provide probabilistic predictions, and continuously refine their understanding makes them a more powerful and robust framework for the future [6] [23].

The suboptimal implementation of best practices in probe use—with only 4% of studies employing a fully rigorous approach—underscores a significant reproducibility challenge in biomedicine [24]. Addressing this requires not only better tools but also a cultural shift among researchers. The solution lies in adopting a multi-faceted strategy: leveraging complementary resources (both expert-curated and data-driven), adhering to the "rule of two" (using two orthogonal probes or a probe with its inactive control), and integrating sophisticated computational models that learn from evidence. This integrated, self-improving approach is essential for generating reliable data, validating therapeutic targets, and ultimately accelerating the discovery of new medicines.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing PAINS and Bayesian Methods in Your Workflow

The discovery of high-quality chemical probes is fundamental to advancing chemical biology and drug discovery. These small molecules enable researchers to modulate the function of specific proteins in complex biological systems, thereby validating therapeutic targets and elucidating biological pathways. However, a significant challenge in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns is the prevalence of false positives—compounds that appear active in assays but whose activity stems from undesirable mechanisms rather than targeted interactions. More than 300 chemical probes have been identified through NIH-funded screening efforts with an investment exceeding half a billion dollars, yet expert evaluation has found over 20% to be undesirable due to various chemistry quality issues [13].

To address this challenge, the scientific community has developed computational filtering methods to identify problematic compounds before they consume extensive research resources. Two predominant approaches have emerged: substructure-based filtering systems, most notably the Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) protocol, and probabilistic modeling approaches such as Bayesian classifiers. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing specifically on the implementation of PAINS filtering with tools like FAFDrugs2, with supporting experimental data and protocols to inform their application in chemical probe research.

Understanding PAINS Filters and the FAFDrugs2 Implementation

The PAINS Filter Framework

PAINS filters represent a knowledge-based approach to identifying compounds with a high likelihood of exhibiting promiscuous assay behavior. These filters originated from systematic analysis of compounds that consistently generated false-positive results across multiple high-throughput screening assays. The fundamental premise is that certain molecular motifs possess intrinsic physicochemical properties that lead to nonspecific activity through various mechanisms, including covalent modification of proteins, redox cycling, aggregation, fluorescence interference, or metal chelation [13].

The PAINS framework comprises a set of structural alerts—defined as SMARTS patterns—that encode these problematic substructures. Initially described by Baell and Holloway in 2010, the PAINS filters have been progressively refined and expanded, with the current definitive set consisting of over 400 distinct substructural features designed for removal from screening libraries [13].

FAFDrugs2 as an Implementation Platform

FAFDrugs2 (Free ADME/Tox Filtering Tools) is an open-source software platform that provides a comprehensive implementation of PAINS filters alongside other compound filtering capabilities [13]. Developed as part of the FAF-Drugs2 program, it offers researchers a practical tool for applying PAINS filters to compound libraries prior to screening or during hit triage [13].

Core Functionality of FAFDrugs2:

- Structural Filtering: Applies SMARTS pattern matching to identify PAINS substructures

- Property Calculation: Computes key molecular descriptors relevant to compound quality

- Flexible Workflow: Enables customized filtering pipelines combining multiple criteria

- Visualization: Provides structural highlighting of flagged substructures for manual inspection

Experimental Protocols for PAINS Filter Application

Standardized Workflow for PAINS Implementation

Protocol 1: Pre-screening Library Preparation using FAFDrugs2

Input Preparation

- Format chemical structures in SDF or SMILES format

- Standardize tautomeric and protomeric states

- Remove salts and counterions

- Generate canonical representations

FAFDrugs2 Configuration

- Select PAINS filter set from available options

- Set additional property filters (optional): Molecular weight ≤ 600, logP ≤ 5, HBD ≤ 5, HBA ≤ 10

- Configure output format and reporting level

Execution and Analysis

- Process compound library through FAFDrugs2

- Export compounds flagged with PAINS alerts for manual review

- Compile statistics on filter passage rates

- Document specific substructure frequencies in flagged compounds

Protocol 2: Post-Hit Triage Application

Primary Screening Analysis

- Identify compounds showing activity in primary assays

- Process hit lists through FAFDrugs2 PAINS filters

- Categorize hits based on presence/absence of PAINS alerts

Confirmatory Testing Prioritization

- Assign lower priority to PAINS-containing compounds

- Design counter-screens specific to suspected interference mechanisms

- Proceed with stringent confirmation protocols for PAINS-containing hits

Experimental Validation Methodologies

To quantitatively evaluate PAINS filter performance, researchers have employed several experimental approaches:

Aggregation Testing Protocol:

- Measure concentration-dependent light scattering

- Assess enzymatic inhibition in presence of detergent (e.g., 0.01% Triton X-100)

- Perform centrifugal filtration to remove aggregates

Redox Activity Assessment:

- Measure glutathione reactivity using LC-MS

- Quantify hydrogen peroxide production in assay buffer

- Test for dithiothreitol (DTT) sensitivity of activity

Covalent Binding Evaluation:

- Incubate compounds with glutathione or N-acetyl cysteine

- Monitor adduct formation by mass spectrometry

- Perform time-dependent inhibition studies

Bayesian Models as a Complementary Approach

Bayesian Learning in Chemical Probe Evaluation

In parallel to substructure filtering, Bayesian classification models offer a probabilistic alternative for assessing compound quality. Unlike the binary classification of PAINS filters, Bayesian models generate a continuous probability score reflecting the likelihood that an expert medicinal chemist would classify a compound as desirable [13].

The Bayesian approach employs machine learning to identify complex patterns in molecular descriptors and structural features associated with high-quality probes. This methodology was validated using expert evaluations of NIH chemical probes, with models achieving accuracy comparable to other drug-likeness measures [13].

Key Differentiating Features

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between PAINS and Bayesian Approaches

| Characteristic | PAINS Filters | Bayesian Models |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Predefined structural alerts | Learned patterns from training data |

| Output | Binary (pass/fail) | Continuous probability score |

| Transparency | Explicit structural rules | Black-box probabilistic relationships |

| Adaptability | Static unless updated | Improves with additional training data |

| Implementation | Straightforward pattern matching | Requires model training and validation |

| Interpretability | Direct structural explanation | Statistical association without causality |

Comparative Performance Assessment

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Analysis of NIH chemical probe evaluations provides experimental data for comparing these approaches. In one study, an experienced medicinal chemist evaluated over 300 probes using criteria including literature related to the probe and potential chemical reactivity [13].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on NIH Probe Set

| Method | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | Implementation in Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Medicinal Chemist | Reference standard | Reference standard | Reference standard | 40+ years experience [13] |

| PAINS Filters | Comparable to other drug-likeness measures | Not specified | Not specified | Implemented via FAFDrugs2 [13] |

| Bayesian Classifier | Comparable to other measures | Not specified | Not specified | Sequential model building with iterative testing [13] |

| Molecular Properties | Informative but not definitive | Higher pKa, molecular weight associated with desirable probes | Heavy atom count, rotatable bonds informative | Calculated using Marvin suite [13] |

Case Study: NIH Probe Analysis

In a direct comparison, researchers applied both approaches to the same set of NIH probes. The Bayesian model was trained using a process of sequential model building and iterative testing as additional probes were included [13]. The study employed function class fingerprints of maximum diameter 6 (FCFP_6) and molecular descriptors in the Bayesian modeling [13].

Analysis of molecular properties of desirable probes revealed they tended toward higher pKa, molecular weight, heavy atom count and rotatable bond number compared to undesirable compounds [13]. This property profile contrasts with traditional drug-likeness guidelines, highlighting the specialized nature of chemical probes versus therapeutics.

Integrated Workflow for Optimal Probe Selection

Strategic Implementation Framework

Based on comparative performance data, an integrated approach leveraging both methodologies provides optimal coverage against false positives:

Diagram 1: Integrated PAINS-Bayesian Screening Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Chemical Probe Assessment

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAFDrugs2 | Software | PAINS filter implementation | Open source [13] |

| CDD Vault | Database Platform | Bayesian model development and compound management | Commercial [13] |

| Collaborative Drug Discovery (CDD) | Public Database | Access to published probe structures and data | Public [13] |

| Marvin Suite | Cheminformatics | Molecular property calculation | Commercial [13] |

| Bayesian Classification Models | Algorithm | Probability scoring of compound desirability | Research implementation [13] |

Both PAINS filtering through tools like FAFDrugs2 and Bayesian modeling offer valuable, complementary approaches to addressing the critical challenge of compound quality in chemical probe discovery. The experimental data demonstrates that each method has distinct strengths: PAINS filters provide transparent, easily interpretable structural alerts with straightforward implementation, while Bayesian models offer a probabilistic, adaptive framework capable of capturing complex patterns beyond simple substructure matching.

For research teams engaged in probe development, the optimal strategy involves sequential application—first employing PAINS filters to eliminate compounds with clear structural liabilities, then applying Bayesian scoring to prioritize compounds with characteristics historically associated with high-quality probes. This integrated approach, combined with appropriate experimental counter-screens, provides a robust defense against the resource drain of pursuing false positives while maximizing the identification of novel, high-quality chemical probes for biological exploration.

The validation of chemical probes and computational models presents a significant challenge in chemical discovery and drug development. Traditional methods, particularly Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters, have served as initial screening tools but present substantial limitations in accurately identifying truly problematic compounds [9]. Within this context, Bayesian model building has emerged as a sophisticated alternative, enabling researchers to sequentially learn from experimental data while quantifying uncertainty in a principled statistical framework.

Sequential Bayesian methods provide a dynamic approach to model calibration and validation, particularly valuable in environments where data arrives progressively and traditional cross-validation techniques are not feasible [27]. This step-by-step guide examines the core principles, implementation methodologies, and experimental validation of Bayesian approaches, contrasting them with the limitations of PAINS filters to provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for rigorous chemical probe research.

Theoretical Foundations of Sequential Bayesian Learning

Core Bayesian Principles for Chemical Applications

At the heart of sequential Bayesian learning lies Bayes' theorem, which describes the correlation between different events and calculates conditional probabilities. The theorem is expressed mathematically as:

P(A|B) = P(B|A) × P(A) / P(B)

where P(A) and P(B) are prior probabilities, P(A|B) and P(B|A) are posterior probabilities, and P(B) is assumed to be greater than zero [28]. In the context of chemical probe validation, this translates to updating beliefs about model parameters or compound behaviors based on newly acquired experimental evidence.

The sequential Bayesian framework operates through iterative model refinement. Beginning with prior knowledge or assumptions, the system updates its beliefs as new experimental data becomes available, resulting in posterior distributions that reflect updated understanding [29]. This process is repeated with each new experiment, progressively refining the model and reducing parameter uncertainty. The Bayesian approach proves particularly valuable in chemical discovery because it explicitly handles uncertainty, incorporates prior knowledge from domain experts, and adapts dynamically to new evidence—capabilities that are especially crucial when working with small, noisy datasets common in early-stage research [28].

The Sequential Calibration and Validation (SeCAV) Framework

The Sequential Calibration and Validation (SeCAV) framework represents an advanced implementation of Bayesian principles specifically designed for model uncertainty quantification and reduction. This approach addresses key limitations in earlier methods like direct Bayesian calibration and the Kennedy and O'Hagan (KOH) framework, whose effectiveness can be significantly affected by inappropriate prior distributions [30].

The SeCAV framework implements model validation and Bayesian calibration in a sequential manner, where validation acts as a filter to select the most informative experimental data for calibration. This process provides a confidence probability that serves as a weight factor for updating uncertain model parameters [30]. The resulting calibrated parameters are then integrated with model bias correction to improve the prediction accuracy of modeling and simulation, creating a comprehensive system for uncertainty reduction.

Comparative Analysis: PAINS Filters vs. Bayesian Models

Fundamental Limitations of PAINS Filters

PAINS filters emerged from the observation that certain chemotypes consistently produced false-positive results across various high-throughput screening assays. Initially developed through analysis of a 100,000-compound library screened against protein-protein interactions using AlphaScreen technology, these filters were designed to identify compounds with substructures associated with promiscuous behavior [17].

However, comprehensive benchmarking studies have revealed significant limitations in PAINS filter performance. When evaluated against a large benchmark containing over 600,000 compounds representing six common false-positive mechanisms, PAINS filters demonstrated poor detection capability with sensitivity values below 0.10, indicating they missed more than 90% of true frequent hitters [9]. The filters also produced substantial false positives, incorrectly flagging numerous valid compounds, including over 85 approved drugs and drug candidates [9].

The fundamental issues with PAINS filters include their origin from a limited dataset with structural bias, technology-specific interference patterns (primarily AlphaScreen), and high test concentrations (50 μM) that may not translate to different experimental conditions [17]. Perhaps most critically, PAINS filters lack mechanistic interpretation for most alerts and provide no clear follow-up strategy for flagged compounds beyond exclusion [9].

Advantages of Sequential Bayesian Approaches

In contrast to the static nature of PAINS filters, Bayesian models offer a dynamic, learning-based approach to chemical validation. Rather than relying on predetermined structural alerts, Bayesian methods evaluate compounds based on their experimental behavior within a specific context, continuously refining predictions as new data becomes available [29].

Sequential Bayesian approaches excel in their ability to quantify and reduce uncertainty over time. By explicitly modeling uncertainty through probability distributions, these methods provide confidence estimates for their predictions—a critical feature for decision-making in chemical probe development [31]. Furthermore, Bayesian models can incorporate multiple data types and experimental conditions into a unified framework, enabling more nuanced compound assessment than binary PAINS classification.

The adaptive nature of Bayesian methods makes them particularly valuable for exploring new chemical spaces where interference patterns may differ from those in existing databases. As demonstrated in automated chemical discovery platforms, Bayesian systems can successfully identify valid reactivity patterns even among compounds that would be flagged by PAINS filters, preventing the premature dismissal of promising chemical matter [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between PAINS Filters and Bayesian Models

| Evaluation Metric | PAINS Filters | Bayesian Models |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | <0.10 (misses >90% of true frequent hitters) [9] | Context-dependent, improves sequentially [31] |

| Specificity | Low (flags many valid compounds) [9] | Adapts to experimental context [29] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | None | Explicit probability estimates [31] |

| Adaptability to New Data | Static rules | Dynamic updating with new evidence [29] |

| Mechanistic Interpretation | Limited for most alerts [9] | Model-based interpretation [29] |

| Experimental Guidance | None beyond exclusion | Actively suggests informative experiments [31] |

Implementation Guide: Sequential Bayesian Workflow

Step-by-Step Bayesian Model Building

Implementing a sequential Bayesian framework for chemical probe validation follows a structured workflow that integrates computational modeling with experimental validation:

Step 1: Define Prior Distributions The process begins with encoding existing knowledge or hypotheses into prior probability distributions. For chemical probe validation, this may include prior beliefs about structure-activity relationships, reactivity patterns, or assay interference mechanisms. These priors can be informed by literature data, computational predictions, or expert intuition [29].

Step 2: Design and Execute Initial Experiments Based on the current state of knowledge, design experiments that maximize information gain. Bayesian optimization techniques can guide this process by identifying experimental conditions that best reduce parameter uncertainty or distinguish between competing hypotheses [28].

Step 3: Update Model with Experimental Results As experimental data becomes available, apply Bayes' theorem to update prior distributions into posterior distributions. This updating process can be implemented through various computational techniques, including Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling or variational inference [29].

Step 4: Assess Model Convergence and Validation Evaluate whether the model has sufficiently converged or requires additional experimentation. Validation metrics may include posterior predictive checks, uncertainty quantification, or comparison with hold-out test data [30].

Step 5: Iterate or Conclude If model uncertainty remains high or validation metrics indicate poor performance, return to Step 2 for additional experimentation. Otherwise, proceed with final model interpretation and application [31].

Diagram 1: Sequential Bayesian Model Building Workflow. This process iterates until model convergence criteria are met.

Experimental Design and Active Learning

A key advantage of sequential Bayesian approaches is their ability to guide experimental design through active learning strategies. Unlike traditional experimental approaches that follow fixed designs, Bayesian active learning dynamically selects experiments based on their expected information gain [31].

The core principle involves optimizing a utility function that balances exploration (gathering information in uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining predictions in promising regions). For chemical probe validation, this might involve selecting compounds that best distinguish between specific and promiscuous binding mechanisms, or optimizing experimental conditions to reduce parameter uncertainty [31].

Formally, this can be framed as minimizing an expected risk function:

R(e;π) = Eθ'∼π(θ') Eo∼P(o|θ';e) Eθ∼P(θ|o;e)ℓ(θ,θ')

where e represents a candidate experiment, π represents the current parameter distribution, o represents observations, and ℓ is a loss function quantifying estimation error [31]. By selecting experiments that minimize this expected risk, researchers can dramatically reduce the number of experiments required to reach confident conclusions.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Bayesian Model Calibration Protocol

The SeCAV framework provides a structured protocol for model calibration and validation:

Initial Gaussian Process Modeling: For computationally intensive models, begin by constructing a Gaussian process (GP) model as a surrogate for the computer model. This approximation enables efficient computation during the calibration process [30].

Sequential Parameter Updates: Implement Bayesian calibration and model validity assessment in a recursive manner. At each iteration, model validation serves to filter experimental data for calibration, assigning confidence probabilities as weight factors for parameter updates [30].

Bias Correction: Following parameter calibration, correct the computational model by building another GP model for the discrepancy function based on the calibrated parameters. This step accounts for systematic differences between model predictions and experimental observations [30].

Posterior Prediction: Integrate all simulation and experimental data to estimate posterior predictions using the results of both parameter calibration and bias correction [30].

This protocol has demonstrated superior performance compared to direct Bayesian calibration, Kennedy and O'Hagan framework, and optimization-based approaches, particularly in handling model discrepancy and reducing the influence of inappropriate prior distributions [30].

Validation Through Historical Reaction Rediscovery

To validate the effectiveness of Bayesian approaches in chemical discovery, researchers have conducted studies testing the ability of Bayesian systems to rediscover historically significant chemical reactions. In one demonstration, a Bayesian Oracle was able to rediscover eight important named reactions—including aldol condensation, Buchwald-Hartwig amination, Heck, Mannich, Sonogashira, Suzuki, Wittig, and Wittig-Horner reactions—by analyzing experimental data from over 500 reactions covering a broad chemical space [29].

The validation process involved:

Probabilistic Model Formulation: Encoding chemical understanding as a probabilistic model connecting reagents and process variables to observed reactivity [29].

Sequential Exploration: The system explored chemical space by randomly selecting experiments, updating its beliefs after each outcome [29].

Anomaly Detection: Tracking observation likelihoods to identify unexpectedly reactive combinations [29].

Pattern Recognition: Inferring reactivity patterns corresponding to known reaction types from the accumulated data [29].

This approach successfully formalized the expert chemist's experience and intuition, providing a quantitative criterion for discovery scalable to all available experimental data [29].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Bayesian Optimization in Chemical Research

| Package Name | Key Features | License | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BoTorch | Modular framework, multi-objective optimization | MIT | [28] |

| COMBO | Multi-objective optimization | MIT | [28] |

| Dragonfly | Multi-fidelity optimization | Apache | [28] |

| GPyOpt | Parallel optimization | BSD | [28] |

| Optuna | Hyperparameter tuning | MIT | [28] |

| Ax | Modular framework built on BoTorch | MIT | [28] |

Successful implementation of sequential Bayesian methods requires both experimental and computational resources. The following toolkit outlines essential components for establishing a Bayesian validation pipeline:

Computational Resources:

- Bayesian Optimization Software: Packages such as BoTorch, Ax, or COMBO provide implementations of Bayesian optimization algorithms [28].

- Probabilistic Programming Languages: Systems like PyMC3, Stan, or TensorFlow Probability enable flexible specification of Bayesian models [29].

- High-Performance Computing: MCMC sampling and other Bayesian computations often require substantial computational resources, particularly for high-dimensional problems [29].

Experimental Resources:

- Robotic Chemistry Platforms: Automated systems such as Chemputer-based setups enable high-throughput experimentation with reproducible liquid handling [29].

- Online Analytics: Integrated analytical instruments including HPLC, NMR, and MS provide rapid characterization of reaction outcomes [29].