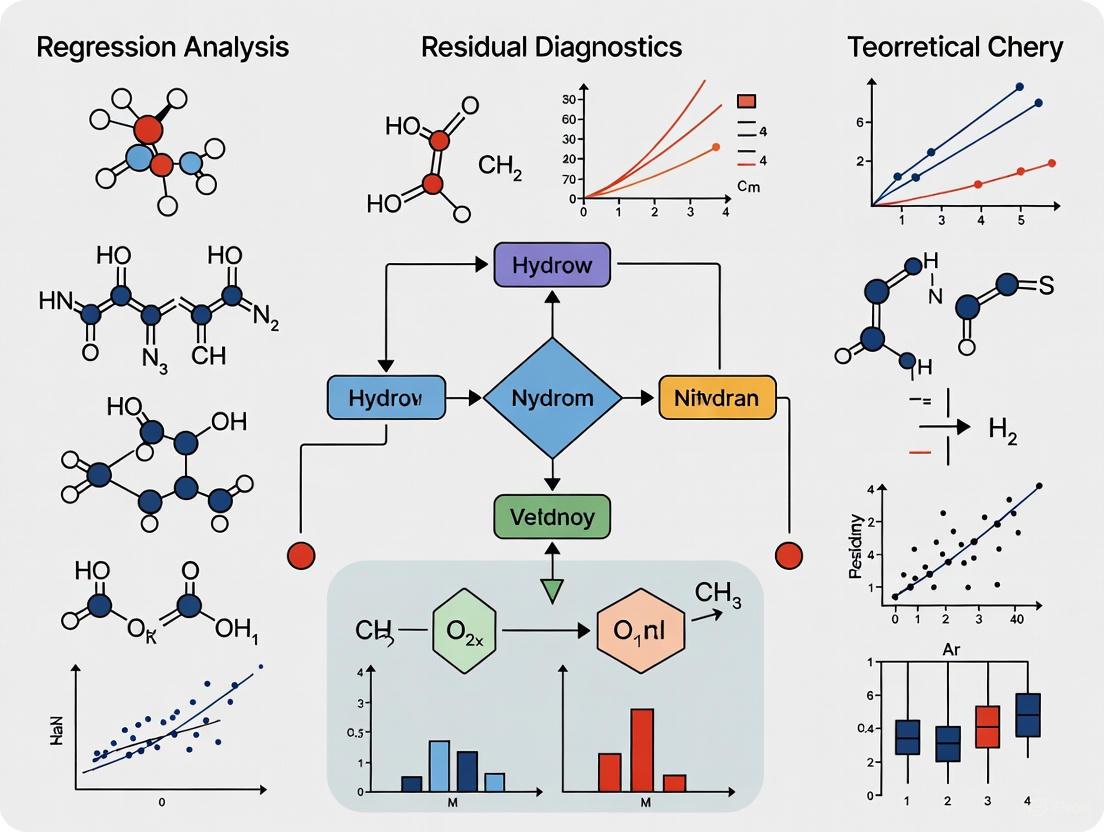

Residual Diagnostics in Regression Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This comprehensive guide explores residual diagnostics in regression analysis, tailored specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Residual Diagnostics in Regression Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores residual diagnostics in regression analysis, tailored specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The article covers foundational concepts of residuals and their critical role in validating regression assumptions, detailed methodologies for creating and interpreting diagnostic plots, practical troubleshooting techniques for addressing common violations, and advanced validation approaches for ensuring model robustness in biomedical applications. Through systematic examination of residual patterns, healthcare researchers can develop more reliable predictive models for clinical trials, treatment optimization, and patient outcome predictions, ultimately enhancing the validity and impact of their data-driven findings.

Understanding Residuals: The Foundation of Regression Model Validation

In regression analysis, the residual represents a fundamental diagnostic measure, defined as the difference between an observed value and the value predicted by a statistical model [1] [2]. This technical guide elaborates on the theoretical foundation, calculation, and diagnostic application of residuals within the broader context of residual diagnostics in regression analysis research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering residual analysis is critical for validating model assumptions, assessing fit adequacy, and ensuring the reliability of statistical inferences drawn from experimental data. This whitepaper provides detailed methodologies for conducting comprehensive residual diagnostics, supported by structured data presentation and visualization protocols essential for rigorous scientific research.

Residuals serve as the cornerstone of regression diagnostics, providing observable estimates of the unobservable statistical error [2]. In the context of statistical modeling, a residual is quantitatively defined as the difference between an observed data point and the corresponding value predicted by the fitted regression model [3] [4]. The conceptual relationship between observed values, predicted values, and residuals forms the basis for assessing model quality and verifying the underlying assumptions of regression analysis.

Within pharmaceutical research and development, residual diagnostics play a pivotal role in validating analytical methods, dose-response modeling, and pharmacokinetic studies. The systematic analysis of residuals enables researchers to identify non-linear relationships, detect outliers that may indicate unusual patient responses, and verify the homoscedasticity assumption critical for reliable confidence intervals and hypothesis tests [5] [6]. When models fail to account for these diagnostic indicators, the resulting statistical inferences may compromise drug efficacy and safety conclusions.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Residuals

| Property | Mathematical Expression | Diagnostic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | ( ri = yi - \hat{y}i ) where ( yi ) is observed value and ( \hat{y}_i ) is predicted value [3] | Base calculation for all residual diagnostics |

| Sum | ( \sum{i=1}^n ri = 0 ) [3] | Verification of calculation accuracy and model intercept |

| Mean | ( \bar{r} = 0 ) [3] | Assessment of systematic bias (non-zero mean indicates bias) |

| Independence | ( Cov(ri, rj) = 0 ) for ( i \neq j ) | Fundamental assumption for valid inference |

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation

Statistical Definition and Formulation

The statistical foundation of residuals distinguishes them from theoretical errors. While errors (( \epsiloni )) represent deviations from unobservable population parameters, residuals (( ri )) represent deviations from sample-based estimates [2]. This distinction is mathematically expressed as:

- Error Term: ( \epsiloni = yi - \mathbb{E}(Y|X) ), representing the deviation from the true population relationship

- Residual: ( ri = yi - \hat{y}_i ), representing the deviation from the sample-derived regression line [2]

In practical terms, the least squares estimation method minimizes the sum of squared residuals (( \sum r_i^2 )), providing the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) under the Gauss-Markov assumptions [3] [7].

Computational Methods

The calculation of residuals follows a systematic protocol applicable across research domains:

- Model Fitting: Estimate parameters of the regression model using least squares estimation or maximum likelihood estimation

- Prediction Generation: Compute predicted values (( \hat{y}_i )) for each observation using the fitted model equation

- Residual Calculation: Subtract predicted values from observed values (( ri = yi - \hat{y}_i )) for all observations [4]

Table 2: Residual Calculation Protocol for a Simple Linear Regression

| Step | Operation | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Specification | ( \hat{y}i = b0 + b1xi ) | Define regression equation with estimated coefficients |

| 2. Prediction | Substitute ( x_i ) into model | For ( xi = 8 ), ( \hat{y}i = 29.63 + 0.7553 \times 8 = 35.67 ) [3] |

| 3. Residual Calculation | ( ri = yi - \hat{y}_i ) | For ( yi = 41 ), ( ri = 41 - 35.67 = 5.33 ) [3] |

| 4. Sum Verification | ( \sum r_i = 0 ) | Confirm calculations sum to approximately zero |

For the drug development researcher, this computational protocol provides a standardized approach for validating model fits across diverse experimental contexts, from clinical trial data analysis to laboratory instrument calibration.

Diagnostic Framework: Residual Analysis in Research

Core Assumption Verification

Residual analysis provides the methodological foundation for verifying critical regression assumptions. The following diagnostic protocol should be implemented for comprehensive model validation:

Linearity Assessment

- Experimental Protocol: Create residual-by-predictor plots for each independent variable

- Diagnostic Interpretation: Random scatter indicates linearity; systematic patterns (e.g., U-shaped curves) suggest model misspecification [8] [5]

- Remedial Action: Apply transformations (log, polynomial) or introduce non-linear terms for predictor variables

Constant Variance (Homoscedasticity) Evaluation

- Experimental Protocol: Generate residuals versus fitted values plot

- Diagnostic Interpretation: Consistent spread across all fitted values confirms homoscedasticity; funnel-shaped patterns indicate heteroscedasticity [5] [9]

- Remedial Action: Implement weighted least squares or variance-stabilizing transformations (log, square root)

Normality Assumption Verification

- Experimental Protocol: Construct normal quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot of residuals [3] [6]

- Diagnostic Interpretation: Points following diagonal reference line support normality; systematic deviations indicate violations

- Remedial Action: Apply Box-Cox transformations or consider robust regression techniques

Independence Testing

- Experimental Protocol: Generate residuals versus time/sequence plot [6]

- Diagnostic Interpretation: Random scatter indicates independence; systematic patterns suggest autocorrelation

- Remedial Action: Incorporate time-series structure or implement generalized least squares

Advanced Residual Diagnostics for Research Applications

Beyond basic assumption checking, sophisticated residual diagnostics provide enhanced detection capabilities for specialized research contexts:

Studentized Residuals

- Calculation Method: ( ti = \frac{ri}{s{-i}\sqrt{1 - h{ii}}} ) where ( s{-i} ) is the RMSE excluding observation i, and ( h{ii} ) is the leverage [6]

- Diagnostic Application: Identifies outliers with greater sensitivity than raw residuals

- Interpretation Threshold: Values exceeding ±2 suggest potentially influential observations

Leverage and Influence Diagnostics

- Leverage Calculation: ( h_{ii} ) from hat matrix, with values > ( \frac{2p}{n} ) indicating high leverage points

- Cook's Distance: ( Di = \frac{\sum{j=1}^n (\hat{y}j - \hat{y}{j(i)})^2}{ps^2} ) quantifies influence on all fitted values [6]

- Interpretation Threshold: Cook's D > 1.0 indicates highly influential observations [6]

Table 3: Advanced Diagnostic Metrics for Pharmaceutical Research

| Diagnostic Metric | Calculation Formula | Research Application | Critical Threshold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studentized Residual | ( ti = \frac{ri}{s{-i}\sqrt{1 - h{ii}}} ) [6] | Detection of outliers in clinical measurements | t_i | > 2 | |

| Leverage (h~ii~) | Diagonal elements of hat matrix H = X(X'X)⁻¹X' | Identification of unusual predictor combinations | h~ii~ > 2p/n | ||

| Cook's Distance | ( Di = \frac{ri^2}{ps^2} \times \frac{h{ii}}{(1 - h{ii})^2} ) [6] | Assessment of individual influence on parameter estimates | D_i > 1.0 [6] | ||

| DFFITS | ( \text{DFFITS}i = ti \times \sqrt{\frac{h{ii}}{1 - h{ii}}} ) | Standardized measure of influence on predicted values | DFFITS | > 2√(p/n) |

Experimental Protocols for Residual Analysis

Standardized Residual Diagnostic Protocol

This section presents a comprehensive methodological framework for implementing residual analysis in drug development research:

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Residual Plot Analysis

- Objective: Systematically evaluate regression assumptions through visual diagnostics

- Materials: Fitted regression model, statistical software with graphing capabilities

- Procedure:

- Generate residuals versus fitted values plot

- Create normal Q-Q plot of residuals

- Produce residuals versus predictor variable plots for each independent variable

- If data is time-ordered, generate residuals versus observation order plot [6]

- Interpretation Criteria:

- Random scatter in residuals vs. fitted indicates appropriate linear specification

- Points following diagonal line in Q-Q plot support normality assumption

- No discernible patterns in residual vs. predictor plots validate linearity

Protocol 2: Quantitative Diagnostic Metrics

- Objective: Compute numerical measures of model adequacy and influence

- Materials: Dataset with observed and predicted values, statistical software

- Procedure:

- Calculate studentized residuals for all observations

- Compute leverage values for each data point

- Determine Cook's Distance measures [6]

- Perform Durbin-Watson test for autocorrelation (if time-ordered data)

- Interpretation Criteria:

- Fewer than 5% of |studentized residuals| > 2 supports normality

- Cook's D values < 1.0 indicate no excessively influential points [6]

- Durbin-Watson statistic near 2.0 supports independence

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Residual Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python, JMP, SAS) | Calculation of residuals and diagnostic metrics | Automated computation and visualization of residual diagnostics [6] |

| Studentized Residual Algorithm | Standardization of residuals accounting for leverage | Enhanced outlier detection in high-dimensional datasets [6] |

| Cook's Distance Calculator | Quantification of observation influence | Identification of data points disproportionately affecting parameter estimates [6] |

| Q-Q Plot Generator | Graphical assessment of distributional assumptions | Evaluation of normality assumption in regulatory submissions |

| Durbin-Watson Test | Formal testing for autocorrelation | Validation of independence assumption in time-course experiments |

Visualization and Interpretation of Residual Patterns

Diagnostic Pattern Recognition

Systematic residual patterns provide critical diagnostic information about model inadequacies:

Non-Linearity Patterns

- Visual Signature: Curvilinear pattern in residuals versus predictor plots

- Research Implication: Model misspecification of functional form

- Corrective Action: Introduce polynomial terms or apply transformations [8] [9]

Heteroscedasticity Patterns

- Visual Signature: Funnel-shaped distribution in residuals versus fitted plot

- Research Implication: Non-constant variance invalidates standard errors

- Corrective Action: Implement weighted regression or variance-stabilizing transformations [5] [9]

Outlier Patterns

- Visual Signature: Isolated points with large residual values

- Research Implication: Potential data errors or special-cause variation

- Corrective Action: Verify data integrity, consider robust regression methods [6]

Quantitative Decision Framework

The following decision matrix supports objective interpretation of residual diagnostics:

Table 5: Residual Pattern Interpretation and Remedial Actions

| Pattern Type | Diagnostic Visualization | Quantitative Metrics | Recommended Remedial Actions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Linearity | Curved pattern in residual vs. predictor plots | Significant lack-of-fit test (p < 0.05) | Polynomial terms, splines, or non-linear models [9] | ||

| Heteroscedasticity | Funnel shape in residual vs. fitted plot | Breusch-Pagan test p < 0.05 | Weighted least squares, variance-stabilizing transformations [5] | ||

| Non-Normality | Systematic deviation from line in Q-Q plot | Shapiro-Wilk test p < 0.05 | Response transformation, robust regression, nonparametric methods | ||

| Autocorrelation | Sequential correlation in residual vs. order plot | Durbin-Watson statistic ≠ 2 | Time series models, generalized least squares [5] | ||

| Influential Points | Isolated points in residual plots | Cook's D > 1.0, | DFBETAS | > 2/√n | Robust regression, validation of data integrity [6] |

Residual analysis provides an indispensable methodological framework for validating regression models in scientific research and drug development. The systematic examination of differences between observed and predicted values enables researchers to verify critical statistical assumptions, identify model deficiencies, and implement appropriate remedial actions. This technical guide has presented comprehensive diagnostic protocols, visualization techniques, and interpretation frameworks that support rigorous model evaluation. For the research professional, mastery of residual diagnostics strengthens the validity of statistical conclusions and enhances the reliability of scientific inferences drawn from regression models. As analytical methodologies continue to advance in complexity, the fundamental principles of residual analysis remain essential for ensuring the integrity of quantitative research across scientific disciplines.

In the rigorous world of statistical modeling, particularly within regression analysis and drug development, the validity of any conclusion hinges on the integrity of the model itself. While researchers often focus on parameters like R-squared and p-values, a model's true reliability is assessed not by its fitted values, but by what remains unexplained: its residuals. Residuals, defined as the differences between observed values and model-predicted values, serve as a powerful diagnostic tool for uncovering model inadequacies that summary statistics might obscure [10]. This technical guide frames residual diagnostics within a broader research thesis, positing that a systematic analysis of residuals is not merely a supplementary step but a critical foundation for robust scientific inference. For researchers and scientists, mastering residual analysis is essential for ensuring that models used for prediction and decision-making are built upon validated assumptions, thereby safeguarding the conclusions drawn in high-stakes environments like clinical trials and drug development.

The Core Assumptions of Regression and the Role of Residuals

Linear regression models, which include t-tests and ANOVA as special cases, rely on several key assumptions about the population error term, denoted as {εᵢ} [10]. Since these true errors are unobservable, analysts work with the estimated residuals, {ε̂ᵢ}, which are the observed values minus the modeled values [10]. The primary assumptions that must be verified through residual analysis are encapsulated by the LINE acronym:

- Linearity: The relationship between the independent and dependent variables is linear.

- Independence: The error terms are uncorrelated with each other.

- Normality: The error terms are normally distributed.

- Equal Variance (Homoscedasticity): The variance of the error terms is constant across all levels of the independent variables.

Violations of these assumptions can have serious practical consequences, including biased estimates, reduced statistical power, and confidence intervals whose actual coverage is far from the nominal value (e.g., 95%) [10]. The following table summarizes the core assumptions and the implications of their violation.

Table 1: Core Regression Assumptions and Implications of Violations

| Assumption | Description | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Independence | Error terms are uncorrelated [10]. | Incorrect estimates of variability, leading to invalid confidence intervals and p-values [10]. |

| Normality | Error terms are normally distributed. | Lack of normality can make estimates especially sensitive to heavy-tailed distributions, affecting the validity of tests and CIs [10]. |

| Constant Variance | Variance of errors is stable across fitted values [11]. | Nominal and actual probabilities of Type I and Type II errors can be very different; CI coverage can be far from nominal [10]. |

| Linearity | The model correctly captures the underlying linear relationship. | Model bias and inaccurate predictions. |

A Comprehensive Methodology for Residual Analysis

A thorough residual analysis employs a suite of graphical and numerical methods to diagnose potential problems. The process is not about eliminating every minor anomaly but about identifying severe violations that threaten the model's validity [11].

Graphical Methods: The First Line of Defense

Graphical methods provide an intuitive yet powerful means to assess the LINE assumptions holistically and judge the severity of any departures [10].

Residuals vs. Fitted Values Plot: This is the primary diagnostic tool. The plot should show a random scatter of points around zero.

Normal Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) Plot: This plot compares the quantiles of the residuals to the quantiles of a theoretical normal distribution.

Residuals vs. Predictor Variables: Plotting residuals against each predictor variable in the model, as well as against potential predictors omitted from the model.

- Purpose: To identify whether non-linearity or non-constant variance is associated with a specific predictor, and to discover if an important variable has been omitted from the model [11].

Residuals vs. Time/Sequence: If data were collected over time or space, this plot is essential.

Formal Statistical Tests

While graphical methods are invaluable for assessing the severity of departures, formal tests provide an objective benchmark [10]. The following table outlines common tests for regression assumptions.

Table 2: Formal Tests for Validating Regression Assumptions

| Assumption | Test Name | Brief Procedure | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independence | Durbin-Watson [10] | Tests for serial correlation in the residuals. | A statistic significantly different from 2 suggests autocorrelation. |

| Normality | Shapiro-Wilk [10] | A test based on a comparison of empirical and theoretical quantiles. | A significant p-value provides evidence against normality. |

| Normality | D'Agostino [10] | Based on sample skewness and kurtosis. | A significant p-value indicates non-normality. |

| Constant Variance | Breusch-Pagan [10] | Regresses squared residuals on the independent variables. | A significant p-value indicates non-constant variance (heteroscedasticity). |

| Constant Variance | Levene's Test [10] | Compares variances across groups. | A significant p-value suggests unequal variances between groups. |

It is crucial to note that with large sample sizes, these tests can flag trivial deviations as statistically significant, and with small sample sizes, they may lack the power to detect serious violations. Therefore, they should always be used in conjunction with graphical analysis [10].

Experimental Protocols for Residual Diagnostics

The following workflow provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for conducting a comprehensive residual analysis, as would be performed in a rigorous research setting.

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Visual Residual Analysis

Objective: To graphically assess a fitted linear regression model for violations of the LINE assumptions.

Materials: A fitted regression model and its resulting set of residuals, {ε̂ᵢ}, and fitted values, {ŷᵢ}.

Procedure:

- Generate the Residuals vs. Fitted Plot: Plot {ε̂ᵢ} on the vertical axis against {ŷᵢ} on the horizontal axis.

- Visual Assessment:

- Affirm the Linearity condition by confirming the average of the residuals remains close to 0 across all fitted values [11].

- Affirm the Equal variance condition by confirming the vertical spread of the residuals is approximately constant from left to right [11].

- Identify any excessively outlying points for further investigation [11].

- Generate the Normal Q-Q Plot: Plot the empirical quantiles of the residuals against the theoretical quantiles of a standard normal distribution.

- Visual Assessment: Check for substantial deviation from a straight line, which would indicate a violation of the Normality assumption [11] [10].

- Generate Residuals vs. Predictor Plots: Create scatterplots with residuals on the vertical axis and each predictor variable (both included and omitted from the model) on the horizontal axis.

- Visual Assessment: Look for any systematic patterns, which might suggest a missing non-linear effect or an omitted variable [11].

Protocol 2: The Lineup Protocol for Visual Inference

Objective: To formally test whether a perceived pattern in a residual plot is statistically significant using a visual inference framework, thereby avoiding over-interpretation of random features [12].

Materials: The true residual plot and a method for generating "null plots" consistent with the model being correctly specified (e.g., via residual rotation distribution) [12].

Procedure:

- Generate the Lineup: Embed the true residual plot randomly among a set of 19 null plots, creating a lineup of 20 plots in total [12].

- Conduct the Visual Test: Present the lineup to one or more human evaluators who are unaware of which plot is the true one.

- Collect Judgments: Ask the evaluators to identify the plot that appears most different from the others.

- Statistical Conclusion: If the true residual plot is consistently identified from the lineup, it provides evidence that the perceived pattern is real and inconsistent with the model assumptions, warranting a rejection of the null hypothesis (H₀) that the model is correct [12].

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

The field of residual diagnostics continues to evolve, with new computational methods enhancing traditional practices.

Automated Assessment with Computer Vision

A significant innovation is the use of computer vision models to automate the assessment of residual plots. This approach addresses the scalability limitation of the human-dependent lineup protocol.

- Methodology: Deep neural networks with convolutional layers are trained to scan images of residual plots and extract local features and patterns [12]. The model is trained to predict a distance measure that quantifies the disparity between the residual distribution of the fitted model and a reference distribution consistent with the null hypothesis [12].

- Performance: Extensive simulation studies show that computer vision models exhibit lower sensitivity than conventional tests but higher sensitivity than human visual tests, making them a valuable tool for automating the diagnostic process and supplementing existing methods [12].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for this automated assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Residual Diagnostics

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Residual Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Residuals vs. Fitted Plot | Primary visual check for linearity and homoscedasticity [11]. | Standard diagnostic for all linear models. |

| Normal Q-Q Plot | Assesses the normality of the error distribution [10]. | Critical for validating inference (CIs, p-values). |

| Durbin-Watson Statistic | Formal test for serial correlation (independence) [10]. | Essential for time series data or any sequentially ordered data. |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Formal test for heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance) [10]. | Used when graphical evidence of fan-shaped pattern is ambiguous. |

| Lineup Protocol | Statistical framework for visual inference to prevent over-interpretation [12]. | Used to formally test if a visual pattern in a residual plot is significant. |

| Computer Vision Model | Automated system for reading and classifying residual plots [12]. | Emerging tool for large-scale model diagnostics and quality control. |

Residual analysis stands as a non-negotiable pillar of rigorous model assessment in regression analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals, moving beyond a superficial examination of model parameters to a deep, diagnostic interrogation of residuals is what separates a reliable, trustworthy model from a potentially misleading one. The methodologies outlined—from foundational graphical techniques and formal tests to advanced protocols like visual inference and computer vision—provide a comprehensive framework for this critical task. By systematically employing these tools, scientists can affirm the validity of their model's assumptions, identify necessary corrections, and ultimately, fortify the scientific conclusions that guide development and innovation. A thorough understanding and application of residual diagnostics is, therefore, not just a statistical exercise, but a fundamental practice in ensuring research integrity.

Residual analysis forms the cornerstone of regression diagnostics, a critical process for verifying whether a statistical model's assumptions are reasonable and whether the results can be trusted for inference and prediction [13]. In essence, residuals—the differences between observed values and model predictions—represent the portion of the variation in the response variable that the regression model fails to explain [14]. Without empirically checking these assumptions through diagnostic techniques, researchers risk drawing misleading conclusions from their models, which is particularly consequential in fields like pharmaceutical research where decisions affect drug development and patient outcomes [13] [15].

The broader thesis of residual diagnostics positions these techniques as an essential safeguard against model misspecification, ensuring that formal inferences—including confidence intervals, statistical tests, and prediction limits—derive from properly validated foundations [13]. This technical guide examines the three primary residual types used in diagnostic procedures: raw, standardized, and studentized residuals. Each offers distinct advantages for detecting different types of model inadequacies, from outliers and influential points to violations of fundamental regression assumptions [16] [15] [17].

Core Concepts and Mathematical Foundations

Definition and Purpose of Residuals

Based on the multiple linear regression (MLR) model:

[Y = \beta0 + \beta1 X1 + \beta2 X2 + \ldots + \betaK X_K + \epsilon]

we obtain predictions (fitted values) for the (i^{th}) observation:

[\hat{yi} = \hat\beta0 + \hat\beta1 x{i1} + \hat\beta2 x{i2} + \ldots + \hat\betaK x{iK}]

The residual represents the discrepancy between the observed outcome and the model prediction, providing the basis for various diagnostic methods that check empirical reasonableness of model assumptions [14] [15].

Visual Representation of Residual Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between different residual types and their roles in regression diagnostics:

Types of Residuals: Properties and Applications

Raw Residuals

Raw residuals (also called ordinary or unstandardized residuals) represent the most straightforward calculation: the simple difference between each observed value and its corresponding fitted value [14] [17]. For the (i^{th}) observation, the raw residual (e_i) is computed as:

[ei = yi - \hat{yi} = yi - \left(\hat\beta0 + \hat\beta1 x_i\right)]

These residuals form the foundation for all other residual types and are particularly useful for checking the overall pattern of model fit [14]. However, a significant limitation of raw residuals is that they typically exhibit nonconstant variance—residuals with x-values farther from (\bar{x}) often have greater variance than those with x-values closer to (\bar{x})—which complicates outlier detection [17].

Standardized Residuals

Standardized residuals address the issue of nonconstant variance by dividing each raw residual by an estimate of its standard deviation [17]. This process yields residuals with a standard deviation very close to 1, making them comparable across the range of predictor values [14]. Standardized residuals are also referred to as internally studentized residuals in some statistical literature and software documentation [17].

The standardization process makes these residuals particularly valuable for identifying outliers, as they provide an objective standard for comparison. In practice, standardized residuals with absolute values greater than 2 are usually considered large, and statistical software like Minitab automatically flags these observations for further investigation [17]. With this criterion, researchers can expect approximately 5% of observations to be flagged as potential outliers in a properly specified model with normally distributed errors, simply by chance.

Studentized Residuals

Studentized residuals (also called externally studentized residuals or deleted t residuals) represent a more refined approach to outlier detection [17]. For each observation, the studentized residual is calculated by dividing its deleted residual by an estimate of its standard deviation, where the deleted residual (di) represents the difference between (yi) and its fitted value in a model that omits the (i^{th}) observation from the calculation [17].

This "leave-one-out" approach makes studentized residuals particularly sensitive to outliers, as the removal of an influential point substantially changes the model fit. Each studentized deleted residual follows a t distribution with ((n - 1 - p)) degrees of freedom, where (p) equals the number of terms in the regression model, allowing for formal statistical testing of potential outliers [17]. Studentized residuals are especially valuable for identifying influential observations—points that have disproportionate impact on the regression coefficients [16] [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Residual Types in Regression Diagnostics

| Residual Type | Calculation | Variance | Primary Diagnostic Use | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Residuals | (ei = yi - \hat{y_i}) | Non-constant | Checking overall patterns of model fit, detecting curvature | No objective standard for magnitude |

| Standardized Residuals | (\frac{ei}{\hat{\sigma}e}) | Constant (~1) | Identifying outliers across predictor space | Absolute value > 2 suggests potential outlier |

| Studentized Residuals | (\frac{di}{\hat{\sigma}{d_i}}) | Constant | Detecting influential observations | Compare to t-distribution with (n-p-1) degrees of freedom |

Diagnostic Applications in Regression Analysis

Detecting Unusual and Influential Observations

Residual analysis plays a crucial role in identifying observations that exert undue influence on regression results. In diagnostic practice, we categorize unusual observations into three distinct types [16] [15]:

Outliers: Observations with large residuals where the dependent-variable value is unusual given its values on the predictor variables [16]. An outlier may indicate a sample peculiarity, data entry error, or model deficiency [16] [15]. Studentized residuals are particularly effective for formal outlier testing, with Bonferroni correction often applied to account for multiple testing [15].

Leverage points: Observations with extreme values on predictor variables, measured by hat values [16] [15]. These points possess the potential to influence the regression curve, though they may not necessarily affect the actual parameter estimates if they follow the overall pattern of the data.

Influential observations: Points that substantially change the regression coefficients when removed, quantified by Cook's distance [15]. Influence can be conceptualized as the product of leverage and outlierness, making observations with both high leverage and large residuals particularly impactful on model results [16].

Assessing Regression Assumptions

Beyond identifying unusual observations, residuals provide the primary means for verifying key regression assumptions [13]:

Linearity: Residual plots against predictors should show no systematic patterns [16] [15]. Curvature may suggest the need for polynomial terms or transformations [15].

Homoscedasticity: The spread of residuals should remain constant across fitted values [16]. Funnel-shaped patterns indicate heteroscedasticity that may require weighted least squares or variance-stabilizing transformations.

Normality: While not always required for coefficient estimation, normally distributed errors are necessary for valid hypothesis tests and confidence intervals [16]. Q-Q plots of residuals provide visual assessment of this assumption.

Table 2: Common Diagnostic Patterns in Residual Analysis

| Diagnostic Pattern | Visual Indicator | Potential Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Nonlinearity | Curved pattern in residual vs. predictor plots | Add polynomial terms, transform predictors, use splines |

| Heteroscedasticity | Funnel or fan shape in residual vs. fitted plots | Transform response variable, use weighted regression, robust standard errors |

| Outliers | Points with large studentized residuals (>│2│) | Verify data accuracy, consider robust regression methods |

| High Leverage | Extreme hat values | Verify data accuracy, consider if observation belongs to population |

| High Influence | Large Cook's distance | Evaluate substantive impact, report results with and without point |

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Residual Analysis

Systematic Diagnostic Workflow

Implementing a structured approach to residual analysis ensures thorough assessment of regression assumptions and detection of problematic observations. The following workflow provides a methodological framework suitable for pharmaceutical research and other scientific applications:

Initial Model Fitting: Begin by estimating the proposed regression model using standard ordinary least squares (OLS) or maximum likelihood estimation, documenting coefficient estimates and overall model fit statistics [16] [15].

Calculation of Multiple Residual Types: Compute raw, standardized, and studentized residuals using statistical software functions. Most packages provide built-in procedures for these calculations, such as

rstudent()for studentized residuals in R or similar commands in Stata [16] [14].Graphical Assessment: Create diagnostic plots including:

- Residuals versus fitted values to assess homoscedasticity and identify nonlinearity [16]

- Residuals versus each predictor to detect missing nonlinear relationships [15]

- Q-Q plots of residuals to assess normality assumption [16]

- Leverage plots (studentized residuals versus hat values) to identify influential points [15]

Formal Statistical Testing: Conduct lack-of-fit tests when nonlinear patterns are suspected [15]. For potential outliers, compute Bonferroni-adjusted p-values based on the studentized residuals [15].

Influence Assessment: Calculate Cook's distance values for each observation, with values substantially larger than others warranting specific investigation [15]. The

influencePlot()function in R's car package simultaneously displays studentized residuals, hat values, and Cook's distances in a single informative plot [15].Sensitivity Analysis: Refit models excluding influential observations to determine their impact on parameter estimates and substantive conclusions. Document changes in coefficients, standard errors, and model fit statistics [15].

Research Reagent Solutions: Diagnostic Tools and Software

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Residual Diagnostics

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Comprehensive regression diagnostics | rstudent(), hatvalues(), cooks.distance() functions |

studentized_resids <- rstudent(model) |

| Stata | Regression modeling and diagnostics | predict command with rstudent option |

predict r, rstudent |

| car Package (R) | Companion to Applied Regression | influencePlot(), residualPlots() functions |

influencePlot(model, id.n=3) |

| ReDiag (Shiny App) | Interactive assumption checking | User-friendly interface for diagnostic testing | Web-based tool for educational use |

| Minitab | Statistical analysis and quality control | Automated outlier detection and residual plots | Flags observations with standardized residuals > │2│ |

Residual diagnostics represents an indispensable component of rigorous regression analysis, particularly in scientific fields like drug development where model misspecification can have substantial consequences. The triad of raw, standardized, and studentized residuals each offers distinct advantages for assessing different aspects of model adequacy, from verifying theoretical assumptions to identifying influential data points.

Raw residuals provide the foundation for diagnostic procedures but lack standardization for formal comparisons. Standardized residuals address this limitation through variance stabilization, enabling objective outlier detection. Studentized residuals further refine this process through external standardization, offering heightened sensitivity to influential observations that disproportionately affect regression results.

When implemented through systematic workflows incorporating both graphical and statistical methods, residual analysis transforms regression from a black-box estimation technique into a transparent, empirically-validated methodology. This diagnostic process ensures that researchers can have appropriate confidence in their models' conclusions, recognizing both the strengths and limitations of their analytical approach based on empirical evidence rather than unverified assumptions.

Within the framework of residual diagnostics in regression analysis research, validating core model assumptions is a critical prerequisite for generating reliable statistical inferences. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the four fundamental assumptions of linear regression—linearity, normality of errors, constant variance (homoscedasticity), and independence of observations. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this paper synthesizes diagnostic methodologies and experimental protocols, emphasizing the central role of residual analysis. The content is structured to serve as a practical reference for ensuring the validity of regression models in scientific and clinical research settings.

Linear regression is a foundational statistical technique for modeling relationships between variables, but its validity is contingent upon several key assumptions. Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased parameter estimates, unreliable confidence intervals, and compromised predictive accuracy [18] [19]. Residual analysis provides the primary diagnostic toolkit for detecting these violations. Residuals—the differences between observed and model-predicted values—serve as proxies for the unobservable error terms [20]. Systematic patterns in residuals indicate potential model misspecification or assumption violations, making their analysis crucial for robust statistical inference, particularly in high-stakes fields like pharmaceutical research and drug development.

The Four Key Assumptions and Their Diagnostic Protocols

Linearity

Conceptual Foundation: The assumption of linearity posits that the relationship between the independent (predictor) and dependent (response) variables is linear in its parameters [18] [21]. This is a fundamental requirement for the model's structural validity.

Diagnostic Methodology: The primary diagnostic tool is a residuals vs. fitted values plot [20] [19]. In this scatter plot, the fitted (predicted) values from the model are placed on the x-axis, and the corresponding residuals are on the y-axis.

- Assumption Met: The plot displays a random scatter of points with no discernible systematic pattern, forming an unstructured cloud centered around zero [20].

- Assumption Violated: The presence of a curvilinear pattern (e.g., a U-shape or inverted U-shape) indicates that the model has failed to capture a non-linear relationship in the data [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Fit the preliminary linear regression model to the dataset.

- Calculate the fitted values and residuals.

- Generate the residuals vs. fitted values plot.

- Visually inspect for the absence of curvilinear patterns.

Remedial Actions:

If non-linearity is detected, apply variable transformations to the dependent and/or independent variables. Common transformations include logarithmic (log(Y) or log(X)), square root (√Y), or polynomial (X², X³) terms to capture the non-linear effect within a linear model framework [21] [19].

Normality

Conceptual Foundation: This assumption states that the error terms of the model are normally distributed [18] [21]. While the coefficient estimates from ordinary least squares (OLS) remain unbiased even when this assumption is violated, normality is crucial for the validity of hypothesis tests (p-values), confidence intervals, and prediction intervals [21] [19].

Diagnostic Methodology:

- Normal Q-Q Plot (Quantile-Quantile Plot): This is the most common visual tool. The quantiles of the standardized residuals are plotted against the quantiles of a theoretical normal distribution [18] [19].

- Statistical Tests: Formal tests like the Shapiro-Wilk test or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test can provide a quantitative assessment of normality, though they are sensitive to large sample sizes [18] [21].

Experimental Protocol:

- After fitting the model, calculate and (optionally) standardize the residuals.

- Generate a Normal Q-Q plot.

- Visually assess the alignment of data points with the reference line.

- For formal validation, run a statistical test for normality.

Remedial Actions:

Apply non-linear transformations to the response variable (e.g., log(Y), √Y). If outliers are causing the non-normality, investigate their legitimacy and consider robust regression techniques [19].

Constant Variance (Homoscedasticity)

Conceptual Foundation: Homoscedasticity requires that the variance of the error terms is constant across all levels of the independent variables [22] [21]. When this assumption is violated (a condition known as heteroscedasticity), the OLS estimates of the coefficients remain unbiased, but their standard errors become biased and inefficient [22] [23]. This results in misleading significance tests and inaccurate confidence intervals [22] [19].

Diagnostic Methodology:

- Scale-Location Plot (Spread-Location Plot): This is a refined version of the residuals vs. fitted plot. It plots the square root of the absolute standardized residuals against the fitted values [19].

- Residuals vs. Fitted Plot: As described in the linearity section, a funnel shape in this plot also indicates heteroscedasticity [19].

- Statistical Tests: The Breusch-Pagan test or Cook-Weisberg test are specifically designed to detect heteroscedasticity [21] [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Fit the regression model and compute the residuals.

- Create a scale-location plot.

- Analyze the plot for any systematic pattern in the vertical spread of the points.

- Conduct a statistical test for heteroscedasticity for confirmation.

Remedial Actions: Transformation of the response variable (Y) is the most common remedy (e.g., log, square root) [22] [19]. Alternatively, weighted least squares (WLS) regression can be employed, assigning smaller weights to observations with higher variance [21] [19].

Independence

Conceptual Foundation: The assumption of independence dictates that the error terms are uncorrelated with each other [21] [20]. Violation of this assumption, known as autocorrelation, frequently occurs in time-series data or clustered data (e.g., repeated measurements from the same patient) [20] [24]. Autocorrelation leads to underestimated standard errors, which in turn inflates test statistics and increases the risk of Type I errors (false positives) [19] [24].

Diagnostic Methodology:

- Durbin-Watson Test: This is the primary statistical test for detecting autocorrelation in residuals.

- Residuals vs. Sequence Plot: If the data is collected over time or in a specific sequence, plotting residuals against their observation order can reveal temporal patterns or cycles [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Consider the data collection structure. Independence is often a question of research design (e.g., presence of repeated measures, clustering).

- For time-ordered data, perform the Durbin-Watson test.

- Create a residuals vs. observation order plot and look for trends or cycles.

Remedial Actions: For autocorrelated data, specialized modeling techniques are required. These include generalized least squares (GLS), linear mixed models (LMMs), or generalized estimating equations (GEEs), which are designed to account for within-cluster or within-time-series correlations [24].

Table 1: Summary of Key Regression Assumptions and Diagnostic Methods

| Assumption | Key Diagnostic Tool | Visual Cue for Violation | Statistical Test | Common Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity | Residuals vs. Fitted Plot | Curvilinear pattern | None widely used | Variable transformation (e.g., log, polynomial) |

| Normality | Normal Q-Q Plot | Deviation from diagonal line | Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov | Transform Y; use robust regression |

| Constant Variance | Scale-Location Plot | Funnel shape (increasing/decreasing spread) | Breusch-Pagan, Cook-Weisberg | Transform Y; Weighted Least Squares |

| Independence | Residuals vs. Sequence Plot | Trend or pattern over sequence/time | Durbin-Watson Test | Generalized Least Squares; Mixed Models |

The Researcher's Toolkit for Residual Diagnostics

The following diagram illustrates the integrated diagnostic workflow for assessing the four key regression assumptions, guiding researchers from model fitting to final validation.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Regression Diagnostic Analysis

Table 2: Essential Analytical Reagents for Regression Diagnostics

| Tool / 'Reagent' | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Residuals vs. Fitted Plot | Detects non-linearity and heteroscedasticity | Initial screening for model misspecification and non-constant variance. |

| Normal Q-Q Plot | Assesses normality of error distribution | Validating assumptions for hypothesis testing and confidence intervals. |

| Scale-Location Plot | Confirms homoscedasticity (constant variance) | Specific diagnosis of changing variance across fitted values. |

| Durbin-Watson Statistic | Tests for autocorrelation in residuals | Essential for time-series data or any sequentially ordered observations. |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | Quantifies multicollinearity (not a residual plot, but a key companion diagnostic) | Ensures independence of predictors; VIF > 5-10 indicates high multicollinearity [18] [21]. |

Residual analysis is the cornerstone of validating regression models, providing researchers with a powerful suite of diagnostic tools. The systematic process of checking for linearity, normality, constant variance, and independence is not merely a statistical formality but a critical step to ensure the integrity of research findings. For professionals in drug development and scientific research, where models inform critical decisions, a rigorous approach to residual diagnostics is indispensable. By adhering to the protocols and utilizing the "toolkit" outlined in this guide, researchers can detect model shortcomings, apply appropriate remedies, and ultimately place greater confidence in their statistical conclusions.

Within regression analysis, a foundational practice for researchers and professionals in drug development and other scientific fields, the accurate diagnosis of a model's validity is paramount. This guide addresses two pervasive and critical misconceptions that can undermine the integrity of statistical conclusions: the conflation of errors with residuals, and the misapplication of normality tests on raw data instead of model residuals. Framed within a broader thesis on residual diagnostics, this technical whitepaper delineates these concepts with mathematical rigor, provides structured experimental protocols for model validation, and visualizes the diagnostic workflow. By equipping scientists with the correct methodologies and tools, this document aims to fortify the analytical process in research and development.

Regression analysis serves as a cornerstone for modeling relationships in scientific data, from determining dose-response in pharmacology to identifying biomarkers in clinical studies. The validity of these models, however, rests upon several key assumptions. The Gauss-Markov theorem establishes that for Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimators to be the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE), specific conditions concerning the model's error term must be met [25]. A fundamental misunderstanding of core concepts can lead to the violation of these assumptions, producing biased, inconsistent, or inefficient estimates.

This guide focuses on clarifying two foundational concepts. First, the distinction between the unobservable error and the observable residual is not merely semantic but is central to understanding what our diagnostics can truly reveal [2] [26]. Second, the assumption of normality in linear regression applies to the error term of the underlying data-generating process (DGP), and since we cannot observe the errors, we use the residuals as their proxies for diagnosis [27] [25]. Testing the raw data for normality, a common error, is not only incorrect but can be misleading, as the distribution of the raw response variable is often a mixture of distributions conditioned on the predictors [28]. The subsequent sections will dissect these concepts, provide clear diagnostic protocols, and present a unified framework for residual analysis.

Core Concepts: Errors vs. Residuals

Theoretical Definitions and Distinctions

In a regression context, the terms "error" and "residual" refer to distinct statistical entities. Understanding this distinction is the first step toward robust model diagnostics.

Error Term (ϵ): The error, often denoted as u or ϵ, represents the unobservable deviation of an observed value from the true, population-level conditional mean [2] [29]. It embodies all unexplained variation in the dependent variable Y that is not captured by the true relationship with the independent variable(s) X. The error term is a theoretical concept inherent to the Data Generating Process (DGP). Key properties, such as being independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) with a mean of zero and constant variance, are assumptions about this error term [2] [26].

Residual (e): The residual, denoted as e, is the observable deviation of an observed value from the estimated, sample-level regression line [2] [29]. It is calculated after fitting the model to a sample of data. Formally, for an observed data point (Xᵢ, Yᵢ), the residual is eᵢ = Yᵢ - Ŷᵢ, where Ŷᵢ is the value predicted by the fitted model [8]. Residuals are estimates of the errors and serve as the primary data source for diagnosing the model's fit and checking the validity of assumptions about the error term [26].

The following table summarizes the critical differences:

Table 1: A Comparative Analysis of Errors and Residuals

| Feature | Error (ϵ) | Residual (e) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Deviation from the true population regression line. | Deviation from the estimated sample regression line. |

| Nature | Unobservable, theoretical [2]. | Observable, calculable from data [29]. |

| Relationship | Inherent part of the Data Generating Process (DGP). | An artifact of the model estimation process. |

| Sum | Sum is almost surely not zero. | Sum is always zero for models with an intercept [2]. |

| Independence | Assumed to be independent. | Not independent; they are constrained by the model [2]. |

| Variance | Has a true, constant variance (σ²). | Variance is estimated and can vary across observations [2]. |

Implications for Statistical Inference

The conflation of errors and residuals can lead to misinterpretations in statistical inference. Since the residuals are estimates and not the true errors, they are subject to the limitations of the sample and the model specification. For instance, the number of independent residuals is reduced by the number of parameters estimated in the model [26]. Furthermore, the distributions of residuals at different data points may vary even if the errors themselves are identically distributed; in linear regression, residuals at the ends of the domain often have lower variability than those in the middle [2]. This is why standardizing or studentizing residuals is a critical step before using them for outlier detection or assumption checking, as it accounts for their expected variability [2].

The Normality Assumption: A Persistent Misapplication

The Source of Confusion

A widespread misconception in regression analysis is that the raw data for the dependent (response) variable must be normally distributed. This is not a requirement of the linear regression model [27] [25]. The core assumption pertains to the distribution of the unobserved error term [25]. The classical linear model assumes that the errors are normally distributed with a mean of zero and constant variance (ϵ ~ N(0, σ²I)). It is this assumption, in conjunction with others, that allows us to derive the sampling distributions of the regression coefficients, enabling hypothesis tests (t-tests, F-tests) and the construction of confidence intervals [27].

Why Testing Raw Data is Misleading

Testing the raw dataset for normality is a diagnostic misstep for several reasons:

- Conditional Distribution: Regression analysis is concerned with the distribution of the dependent variable Y conditional on the independent variables X. The unconditional distribution of Y (the raw data) can be highly non-normal (e.g., skewed or multi-modal) even if the errors are perfectly normal. This occurs because the distribution of Y is a mixture of the conditional distributions across all levels of X.

- Empirical Evidence: Recent research in neuropsychology has directly compared using raw scores versus transformed scores in regression-based normative data. The study concluded that "raw scores should be the preferred choice" and explicitly discouraged transforming data for normality of the observed response. If residual analysis indicates poor model fit, the recommendation is to consider nonlinear models rather than transforming the raw data [28].

- The Central Limit Theorem's Role: For large sample sizes, the Central Limit Theorem ensures that the sampling distributions of the coefficients are approximately normal, even if the underlying errors are not. As noted in the search results, normality tests become more powerful with larger samples, potentially detecting trivial deviations from normality that have no practical impact on inference [27]. Conversely, with small samples, these tests have low power to detect actual non-normality that could be problematic.

The Correct Approach: Testing Residuals

The appropriate diagnostic practice is to test the residuals of the fitted model for normality. Since the residuals serve as empirical proxies for the unobservable errors, their distribution should be examined to evaluate the plausibility of the normality assumption [25]. The following protocol outlines the standard methodology:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Normality Testing of Residuals

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Estimation | Fit the regression model using OLS or another appropriate method. | Obtain the estimated coefficients (a, b₁, b₂, ...) for the model: Ŷ = a + b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + ... |

| 2. Residual Calculation | Calculate residuals for all observations: eᵢ = Yᵢ - Ŷᵢ. | Most statistical software (R, Python, SAS, Statistica) can automatically generate and save these values after model fitting [27]. |

| 3. Diagnostic Selection | Choose graphical and/or statistical tests. | Graphical: Histogram of residuals, Q-Q (Quantile-Quantile) plot [30] [25]. Statistical: Shapiro-Wilk test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [25]. |

| 4. Interpretation | Analyze the diagnostic outputs. | Graphical: In a Q-Q plot, points should closely follow the 45-degree reference line [30]. Statistical: A p-value > 0.05 suggests no significant evidence against normality [25]. |

A Comprehensive Workflow for Residual Diagnostics

Residual analysis extends far beyond testing for normality. A systematic examination of residuals can reveal non-linearity, heteroscedasticity, autocorrelation, and the presence of influential outliers [31]. The following workflow and diagram provide a structured approach for researchers.

Interpreting Residual Plots and Taking Action

The "Residuals vs. Predicted Values" plot is the most powerful tool for diagnosing a range of model inadequacies [8] [30]. The ideal plot shows a random cloud of points scattered evenly around zero, with constant variance across all levels of the predicted value [8]. Deviations from this pattern indicate specific problems:

Curved or U-shaped Pattern: This is a clear indicator of non-linearity [8] [9]. The model is misspecified, as it fails to capture the true functional form of the relationship.

Funnel or Fan-shaped Pattern: This indicates heteroscedasticity, a violation of the constant variance assumption [8] [9]. The spread (variance) of the residuals increases or decreases systematically with the predicted value.

Pattern of a few points with large residuals: This suggests the presence of outliers.

- Remedial Actions: Investigate these data points for measurement error. Use influence statistics like Cook's Distance to determine if they are unduly influencing the model [9]. Depending on the context, outliers might be corrected, removed, or the model might be refit using robust regression techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Regression Diagnostics

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Residual Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Residuals (eᵢ) | The primary diagnostic material; estimates the unobservable model error. | Calculate as Observed - Predicted [8]. Must be computed for all observations. |

| Residual vs. Predicted Plot | A graphical assay to detect non-linearity, heteroscedasticity, and outliers. | The first and most informative plot to generate [8] [30]. |

| Normal Q-Q Plot | A graphical assay to assess the normality of the residuals. | Plots sample quantiles against theoretical normal quantiles. Linearity suggests normality [30]. |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | A formal statistical test for normality. | A quantitative supplement to the Q-Q plot. P > 0.05 suggests normality [25]. |

| Cook's Distance | A statistical metric to identify influential outliers. | Flags data points whose removal would significantly alter the model coefficients [9]. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | The laboratory environment for conducting the analysis. | R (statsmodels, ggplot2) and Python (scikit-learn, statsmodels, seaborn) have built-in functions for all these diagnostics [30]. |

Within the rigorous framework of regression analysis, precision in concept and practice is non-negotiable. This guide has established that the distinction between errors (a theoretical property of the DGP) and residuals (an observable product of our model) is fundamental. Consequently, the diagnostic process for validating the normality assumption must be applied to the residuals, not the raw data. By adopting the comprehensive diagnostic workflow outlined—centered on the interpretation of residual plots and supported by formal tests—researchers and drug development professionals can move beyond common misconceptions. This ensures that their statistical models are not only well-specified but that the inferences drawn from them are valid and reliable, thereby strengthening the scientific conclusions that inform critical development decisions. A thorough residual analysis is not merely a box-ticking exercise; it is an integral part of the scientific dialogue between the model and the data.

Residual Diagnostic Methods: Practical Applications in Biomedical Research

Residual diagnostics form the cornerstone of model validation in regression analysis, serving as a critical bridge between theoretical assumptions and empirical data. Within the broader thesis of residual diagnostics research, these analytical techniques provide the necessary evidence to either substantiate a model's validity or reveal its inadequacies, thereby guiding meaningful model improvement. For researchers and drug development professionals, this is not merely a statistical exercise but a fundamental practice to ensure the reliability of inferences drawn from models, which can influence critical decisions in drug efficacy and safety. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive examination of the four essential diagnostic plots: Residuals vs. Fitted, Normal Q-Q, Scale-Location, and Residuals vs. Leverage. We will deconstruct their theoretical underpinnings, detail their interpretation protocols, and integrate their findings into a cohesive diagnostic workflow, thereby equipping scientists with a robust framework for model verification and refinement.

Residual diagnostics is a fundamental process in regression analysis aimed at evaluating the validity and adequacy of a fitted model. A residual, defined as the difference between an observed value and the value predicted by the model (e = y - ŷ), contains valuable information about why the model may or may not be appropriate for the data [5]. The core premise of residual analysis is that if a model is perfectly specified, the residuals should reflect the properties of the underlying, unobservable error term. Consequently, analyzing residuals allows researchers to check the key assumptions of linear regression, including linearity, normality, homoscedasticity (constant variance), and independence of errors [32] [5].

Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased parameter estimates, incorrect standard errors, and invalid confidence intervals and hypothesis tests, ultimately compromising the integrity of any scientific conclusions [33]. Therefore, conducting a thorough residual analysis is not an optional step but an essential component of the regression modeling process, ensuring the model's predictions and inferences are both reliable and valid [5]. This is particularly crucial in fields like drug development, where model outcomes can inform high-stakes decisions.

The Quartet of Essential Diagnostic Plots

The four diagnostic plots discussed in this guide are the primary tools for visual residual analysis. They are often produced simultaneously using statistical software. In R, for instance, the plot() function applied to an lm object generates these four plots sequentially [32].

The table below summarizes the primary purpose and key features of each plot.

Table 1: Overview of the Four Essential Diagnostic Plots

| Plot Name | Primary Diagnostic Purpose | X-Axis | Y-Axis | Ideal Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residuals vs. Fitted | Check for non-linearity and heteroscedasticity [34] [32] | Fitted Values (ŷ) | Residuals (e) | Residuals bounce randomly around zero; no discernible patterns [34] |

| Normal Q-Q | Assess if residuals are normally distributed [32] [33] | Theoretical Quantiles | Standardized Residuals | Points follow the dashed reference line closely [32] |

| Scale-Location | Evaluate homoscedasticity (constant variance) [32] [35] | Fitted Values (ŷ) | √Standardized Residuals√ | A horizontal line with equally spread points [35] |

| Residuals vs. Leverage | Identify influential observations [32] [36] | Leverage | Standardized Residuals | No points outside of Cook's distance lines [36] |

Residuals vs. Fitted Plot

Purpose and Interpretation

The Residuals vs. Fitted plot is the most frequently created plot in residual analysis [34]. Its primary purpose is to verify the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity. In a well-behaved model, the residuals should be randomly scattered around the horizontal line at zero (the residual = 0 line), forming a roughly horizontal band [34] [32]. This random scattering indicates that the relationship between the predictors and the outcome is linear and that the variance of the errors is constant.

Common Patterns and Diagnoses

Deviations from the ideal pattern reveal specific model shortcomings:

- Funnel or Megaphone Shape: The spread of the residuals increases or decreases systematically with the fitted values. This indicates heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance) [32] [37].

- Curvilinear Pattern (e.g., a U-shape or parabola): The residuals show a systematic curved pattern. This suggests a non-linear relationship that the model has failed to capture [32] [37]. The solution may be to add a quadratic term or apply a non-linear transformation to the variables.

The following diagram illustrates the diagnostic workflow for this plot.

Normal Q-Q Plot

Purpose and Interpretation

The Normal Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plot is a visual tool for assessing whether the model residuals follow a normal distribution [32] [33]. This is a critical assumption for conducting accurate hypothesis tests and constructing valid confidence intervals for the model parameters [33]. The plot compares the quantiles of the standardized residuals against the quantiles of a theoretical normal distribution. If the residuals are perfectly normal, the points will fall neatly along the straight reference line [32].

Common Patterns and Diagnoses

Systematic deviations from the reference line indicate specific types of non-normality:

- S-shaped Curve: Indicates light-tailed distributions (platykurtic).

- Inverted S-shaped Curve: Indicates heavy-tailed distributions (leptokurtic).

- Points consistently above the line at the left and below at the right: This "J-shape" indicates positive skew (the distribution has a long right tail) [33].

- Points consistently below the line at the left and above at the right: This indicates negative skew (the distribution has a long left tail).

Table 2: Interpreting Common Q-Q Plot Patterns

| Observed Pattern | Interpretation | Description of Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Points follow the line | Residuals are normally distributed | Symmetric, bell-shaped |

| J-shape | Positive Skew | Mean > Median; long tail to the right |

| Inverted J-shape | Negative Skew | Mean < Median; long tail to the left |

| S-shape | Light Tails | Fewer extreme values than a normal distribution |

| Inverted S-shape | Heavy Tails | More extreme values than a normal distribution |

Scale-Location Plot

Purpose and Interpretation

Also known as the Spread-Location plot, this graphic is specifically designed to check the assumption of homoscedasticity (constant variance) [32] [35]. It plots the fitted values against the square root of the absolute standardized residuals. This transformation helps in visualizing the spread of the residuals more effectively. A well-behaved plot will show a horizontal red line (a smoothed curve) with randomly scattered points, indicating that the spread of the residuals is roughly equal across all levels of the fitted values [35].

Common Patterns and Diagnoses

The most common violation is a clear pattern in the smoothed line:

- Upward Sloping Line: The spread of the residuals increases with the fitted values. This is another indicator of heteroscedasticity, consistent with the funnel pattern in the Residuals vs. Fitted plot [32] [35].

- Downward Sloping or Curved Line: Indicates that the variance is not constant, which violates a key assumption of ordinary least squares regression.

Residuals vs. Leverage Plot

Purpose and Interpretation

This plot is used to identify influential observations—data points that have a disproportionate impact on the regression model's coefficients [32] [36]. The x-axis represents Leverage, which measures how far an independent variable deviates from its mean. High-leverage points are outliers in the predictor space. The y-axis shows the Standardized Residuals. The plot also includes contour lines of Cook's distance, a statistic that measures the overall influence of an observation on the model [36].

Common Patterns and Diagnoses

The key is to look for points that fall outside of the Cook's distance contours (the red dashed lines).

- Points inside Cook's distance lines: These observations are not particularly influential.

- Points outside Cook's distance lines: These are highly influential observations. Their removal from the dataset would significantly change the results of the regression analysis [36]. It is crucial to investigate these points for data entry errors and to understand how their inclusion or exclusion affects the scientific conclusions.

Integrated Diagnostic Workflow and Experimental Protocol

A Unified Workflow for Diagnostic Plot Analysis

The true power of diagnostic plots is realized when they are interpreted in concert. The following workflow provides a systematic protocol for researchers.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Model Fitting and Plot Generation: After fitting a linear regression model using standard functions (e.g.,

lm()in R), generate the suite of four diagnostic plots. In R, this is typically achieved withplot(lm_object)[32]. - Sequential Interpretation:

- Begin with Residuals vs. Fitted: First, assess this plot for clear violations of linearity and constant variance. A clear pattern here is a major red flag [34] [32].

- Proceed to Normal Q-Q: Next, evaluate the normality of the residuals. Note that for large samples, slight deviations in the tails may not be critical, but severe skew is a concern [33].

- Confirm with Scale-Location: Use this plot to further investigate homoscedasticity. It often makes patterns of non-constant variance easier to see [35].

- Finish with Residuals vs. Leverage: Finally, screen for influential points that may be unduly affecting the model's results [36].

- Evidence Synthesis: Cross-reference the findings from all plots. For example, a point flagged as an outlier in the Q-Q plot might also be a high-leverage point in the Residuals vs. Leverage plot. Such a point warrants intense scrutiny [32].

- Corrective Action: Based on the synthesized evidence, proceed with model refinement. This may include variable transformation, adding polynomial terms, using robust regression methods, or investigating and potentially removing influential points after careful consideration [32] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Regression Diagnostics

In the context of statistical modeling, "research reagents" refer to the key functions, measures, and tests that form the essential toolkit for conducting thorough residual diagnostics.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Regression Diagnostics

| Reagent / Function | Type | Primary Function | Interpretation Guide |

|---|---|---|---|

plot.lm() (R) |

Software Function | Generates the four core diagnostic plots from an lm object [32] |

The primary tool for visual diagnostics. |

| Cook's Distance | Statistical Measure | Quantifies the influence of a single observation on the entire set of regression coefficients [36] | Points with Cook's D > 4/n are often considered influential [36]. |

| Standardized Residuals | Statistical Measure | Residuals scaled by their standard deviation, making it easier to identify outliers [5]. | Absolute values > 3 may indicate outliers. |

| Leverage (Hat Values) | Statistical Measure | Identifies outliers in the space of the independent variables (X-space) [36] [5]. | High leverage if > 2p/n (p = # of predictors). |

| Shapiro-Wilk Test | Statistical Test | Formal hypothesis test for normality of residuals [33]. | Null hypothesis: residuals are normal. Low p-value (e.g., <0.05) suggests non-normality [33]. |

| Breusch-Pagan Test | Statistical Test | Formal hypothesis test for heteroscedasticity [35]. | Null hypothesis: constant variance. Low p-value suggests heteroscedasticity [35]. |

The quartet of diagnostic plots—Residuals vs. Fitted, Normal Q-Q, Scale-Location, and Residuals vs. Leverage—provides an indispensable framework for validating regression models. Within the broader thesis of residual diagnostics, these plots move beyond mere technical checks; they form a dialogue between the model and the data, revealing the hidden stories of model inadequacy and guiding iterative improvement. For the research scientist, mastery of these tools is not optional. It is a fundamental aspect of rigorous, reproducible research, ensuring that the models upon which critical decisions are based are not just statistically significant, but are truly valid and reliable representations of complex biological and chemical realities.

Step-by-Step Guide to Creating and Interpreting Residual Plots in Statistical Software

Within the broader thesis of residual diagnostics in regression analysis research, this technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for creating and interpreting residual plots—a critical component of model validation and diagnostic assessment. Residual analysis serves as a foundational methodology for verifying regression assumptions, identifying model deficiencies, and ensuring the reliability of statistical inferences, particularly in scientific fields such as pharmaceutical development where accurate predictive models are paramount. This whitepaper establishes standardized protocols for residual diagnostic procedures, enabling researchers to systematically evaluate model adequacy and implement corrective measures when assumptions are violated.

Residual analysis constitutes a fundamental diagnostic procedure in regression modeling that examines the differences between observed values and those predicted by the statistical model. These differences, known as residuals, contain valuable information about model adequacy and potential assumption violations. Formally, a residual is defined as the difference between an observed value and the corresponding value predicted by the model: Residual = Observed - Predicted [8] [5]. In the context of scientific research and drug development, thorough residual analysis is indispensable for ensuring that statistical models accurately represent underlying biological relationships and produce reliable inferences for decision-making.

The theoretical foundation of residual analysis rests on several key assumptions of linear regression models: linearity of the relationship between independent and dependent variables, independence of errors, homoscedasticity (constant variance of errors), and normality of error distribution [5] [38]. Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased parameter estimates, incorrect standard errors, and invalid statistical inferences—potentially compromising research conclusions and subsequent applications in drug development pipelines. Residual plots provide visual diagnostic tools that allow researchers to detect these violations and assess whether regression assumptions have been satisfied.

Theoretical Foundations of Residuals

Mathematical Definition and Properties

Residuals represent the unexplained portion of the response variable after accounting for the systematic relationship described by the regression model. For a regression model with (n) observations, the residual (e_i) for the (i^{th}) observation is calculated as:

[ei = yi - \hat{y_i}]