Robust Validation Strategies for Computational Models in Drug Discovery: A Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to validation strategies for computational models, with a specific focus on applications in drug discovery and development.

Robust Validation Strategies for Computational Models in Drug Discovery: A Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to validation strategies for computational models, with a specific focus on applications in drug discovery and development. It covers foundational concepts, core methodological techniques, advanced troubleshooting for real-world data challenges, and a comparative analysis of machine learning methods. Tailored for researchers and scientists, the content synthesizes current best practices to ensure model reliability, improve generalizability, and ultimately reduce the high failure rates in pharmaceutical pipelines.

Why Model Validation is Non-Negotiable in Drug Discovery

The Critical Role of Validation in Reducing Drug Development Attrition

Drug development is a high-stakes field characterized by astronomical costs and a notoriously high failure rate, with a significant number of potential therapeutics failing in late-stage clinical trials. This attrition not only represents a massive financial loss but also delays the delivery of new treatments to patients. Validation strategies for computational models are emerging as a powerful means to de-risk this process. By providing more reliable predictions of drug behavior, safety, and efficacy early in the development pipeline, robustly validated computational methods can help identify potential failures before they reach costly clinical stages [1] [2].

The adoption of these advanced computational tools is accelerating. The computational performance of leading AI supercomputers has grown by 2.5x annually since 2019, enabling vastly more complex modeling and simulation tasks that were previously infeasible [3]. This firepower is being directed toward critical challenges, including the prediction of drug-drug interactions (DDIs), which can cause severe side effects, reduced efficacy, or even market withdrawal [4]. As the industry moves toward multi-drug treatments for complex diseases, the ability to accurately predict these interactions through computational models becomes paramount for patient safety and drug success [4].

Comparing Computational Validation Methodologies

The landscape of computational tools for drug development is diverse, with different platforms offering unique strengths. The choice of tool often depends on the specific stage of the research and the type of validation required. The following table summarizes the core applications of key platforms in the method development and validation workflow [2].

Table 1: Computational Platforms for Method Development and Validation

| Platform | Primary Role in Validation | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB | Numerical computation & modeling | Simulating HPLC method robustness under ±10% changes in pH and flow rate to predict method failure rates [2]. |

| Python | Open-source flexibility & ML integration | Predicting LC-MS method linearity and Limit of Detection (LOD) using machine learning models trained on historical data [2]. |

| R | Statistical validation & reporting | Generating automated validation reports for linearity, precision, and bias formatted for FDA/EMA submission [2]. |

| JMP | Design of Experiments (DoE) & QbD | Executing a central composite DoE to optimize HPLC mobile phase composition and temperature simultaneously [2]. |

| Machine Learning | Predictive & adaptive modeling | Creating hybrid ML-mechanistic models to predict method robustness across excipient variability in complex formulations [2]. |

Beyond general-purpose platforms, specialized models for specific prediction tasks like DDI have demonstrated significant performance. A review of machine learning-based DDI prediction models reveals a variety of approaches, each with its own strengths as measured by standard performance metrics [4].

Table 2: Performance of Select Machine Learning Models in Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

| Model/Method Type | Key Methodology | Reported Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Networks | Uses chemical structure and protein-protein interaction data for prediction. | High accuracy in predicting DDIs and drug-food interactions in specific patient populations (e.g., multiple sclerosis) [4]. |

| Graph-Based Learning | Models drug interactions as a network, integrating similarity of chemical structure and drug-binding proteins. | Effectively identifies potential DDI side effects by capturing complex relational data [4]. |

| Semi-Supervised Learning | Leverages both labeled and unlabeled data to overcome data scarcity. | Shows promise in expanding the scope of predictable interactions with limited training data [4]. |

| Matrix Factorization | Decomposes large drug-drug interaction matrices to uncover latent patterns. | Useful for large-scale prediction of unknown interactions from known DDI networks [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

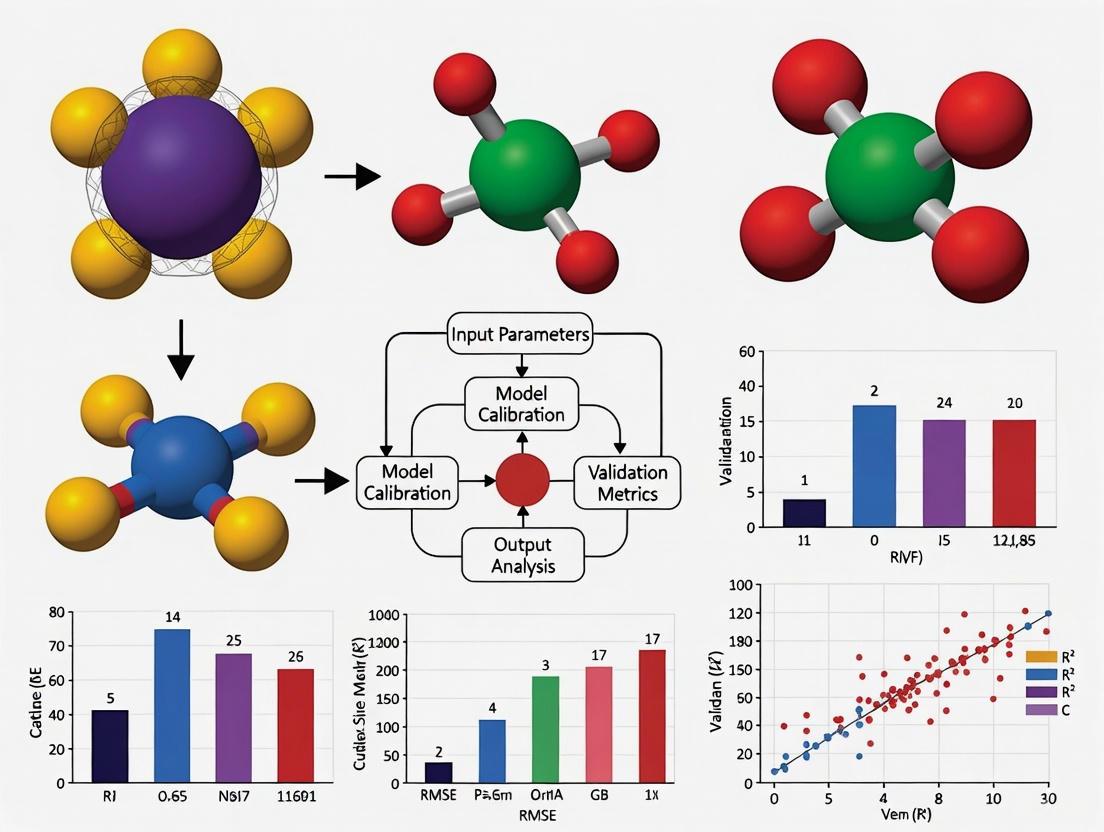

To ensure that computational models are reliable and fit for purpose, they must undergo rigorous validation based on well-defined experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines a generalized but critical pathway for developing and validating a computational model, such as one for DDI prediction, emphasizing the integration of machine learning.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Step 1: Problem Formulation & Data Collection

- Objective: Define the specific interaction to be predicted (e.g., pharmacokinetic alteration, increased toxicity) and gather relevant data [4].

- Data Sources: Collect data from structured databases, which may include drug-related entities such as chemical structures, genes, protein bindings, and known ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties [4]. Historical data from electronic health records can also be a source for mining interactions [4].

- Output: A curated dataset ready for preprocessing.

Step 2: Data Preprocessing & Feature Engineering

- Objective: Prepare raw data for machine learning algorithms and create meaningful input features.

- Methods:

- Handle Class Imbalance: A common issue in DDI prediction where known interactions are far fewer than non-interactions. Techniques like oversampling or undersampling may be applied [4].

- Feature Extraction: Generate features from molecular structures, such as chemical descriptors or fingerprints. Integrate features from biological data, like protein-protein interaction networks [4].

- Output: A clean, balanced dataset with engineered features.

Step 3: Model Selection & Training

- Objective: Choose an appropriate ML algorithm and train it on the prepared data.

- Methods:

- Algorithm Choice: Select from supervised (e.g., Deep Neural Networks), semi-supervised, self-supervised, or graph-based learning methods based on the data availability and problem complexity [4].

- Training: Split data into training and testing sets. Use the training set to fit the model parameters.

- Output: A trained predictive model.

Step 4: Model Validation & Performance Testing (Critical Phase)

- Objective: Empirically evaluate the model's predictive accuracy and robustness.

- Methods:

- Performance Metrics: Use the held-out test set to calculate metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), Specificity, and AUC-ROC curves [4].

- Robustness Testing: Evaluate model performance on new drugs not seen during training to assess generalizability, a known challenge for many models [4].

- Explainability Analysis: Investigate the model's decision-making process to build trust and identify potential biases. This is a key limitation in many state-of-the-art models [4].

- Output: A quantitative performance assessment and explainability report.

Step 5: Regulatory Alignment & Documentation

- Objective: Ensure the model and its validation process comply with regulatory standards.

- Methods:

- Adhere to Guidelines: Follow relevant FDA guidance, ICH guidelines, and standards like GAMP5 (2nd Edition) for computer system validation [1].

- Ensure Data Integrity: Implement controls that align with FDA 21 CFR Part 11 for electronic records [1].

- Documentation: Create a comprehensive validation report that details the entire process, from data provenance to performance results [2].

- Output: A regulatory-ready validation package.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental and computational workflow relies on a suite of essential tools and databases. The following table details key "reagent solutions" for computational scientists working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for Computational Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| AI Supercomputers | Hardware | Provides the computational power (FLOP/s) needed for training complex models and running large-scale simulations [3]. |

| MATLAB | Software Platform | Enables numerical modeling and simulation of analytical processes (e.g., chromatography) to predict method robustness [2]. |

| Python with ML Libraries | Software Platform | Offers open-source flexibility for building, training, and validating custom machine learning models for tasks like DDI prediction [2]. |

| Structured Biological Databases | Data Resource | Provides curated data on drug entities (genes, proteins, etc.) essential for feature engineering and model training [4]. |

| R Statistical Environment | Software Platform | The gold standard for performing rigorous statistical analysis and generating validation reports for regulatory submission [2]. |

| JMP | Software Platform | Facilitates Quality by Design (QbD) through statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) to optimize analytical methods computationally [2]. |

| Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) | Guideline | Provides standards for color contrast (e.g., 4.5:1 for normal text) to ensure data visualizations are accessible to all researchers [5] [6]. |

The critical path to reducing attrition in drug development lies in the rigorous and pervasive application of computational validation strategies. As the reviewed models and protocols demonstrate, the integration of machine learning with traditional pharmaceutical sciences creates a powerful framework for de-risking the development pipeline. The transition from empirical, trial-and-error methods to data-driven, simulation-supported approaches is no longer a future vision but a present-day necessity [2].

The future of this field points toward even deeper integration. The next generation of method development will be characterized by AI-driven adaptive models, digital twins of analytical instruments, and automated regulatory documentation pipelines [2]. Furthermore, overcoming current limitations—such as model explainability, performance on new molecular entities, and handling complex biological variability—will be the focus of ongoing research [4]. By embracing these advanced, validated computational tools, the pharmaceutical industry can significantly improve the efficiency of delivering safe and effective drugs to the patients who need them.

In computational modeling and simulation, the ability to trust a model's predictions is paramount. For researchers and drug development professionals, this trust is formally established through rigorous processes known as verification, validation, and the assessment of generalization. These are not synonymous terms but rather distinct, critical activities that collectively build confidence in a model's utility for specific applications. Within the high-stakes environment of pharmaceutical innovation, where model-informed drug development (MIDD) can derisk candidates and optimize clinical trials, a meticulous approach to these processes is non-negotiable [7]. This guide provides a foundational understanding of these core concepts, objectively compares their application across different computational domains, and details the experimental protocols that underpin credible modeling research.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Verification: "Did We Build the Model Right?"

Model verification is the process of ensuring that the computational model is implemented correctly and functions as intended from a technical standpoint. It answers the question: "Have we accurately solved the equations and translated the conceptual model into a error-free code?" [8] [9] [10].

- Key Focus: The internal correctness of the model's code, algorithms, and numerical methods. It is a check against coding errors, implementation mistakes, and numerical solution inaccuracies [8].

- Common Techniques: This process often involves techniques such as code reviews by experts, interactive debugging, verification of logic flows, and examining model outputs for reasonableness under a variety of input parameters [10]. The objective is to confirm that the computer program and its solution method are correct [9].

Validation: "Did We Build the Right Model?"

Model validation is the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of its intended uses [8] [9]. It answers the question: "Does the model's output agree with real-world experimental data?"

- Key Focus: The external accuracy and credibility of the model in representing the actual system [10]. It quantifies the level of agreement between simulation outcomes and experimental observations [8].

- Common Techniques: Validation is typically achieved through systematic comparison of model predictions with experimental data. This can include statistical hypothesis tests, confidence interval analysis, and sensitivity analysis to ensure the model exhibits reasonable behavior [11] [10]. A model is considered validated for a specific purpose when it possesses a "satisfactory range of accuracy" for that application [9].

Generalization: "Does the Model Perform in New Situations?"

Generalization, while sometimes discussed as part of validation, specifically refers to a model's ability to maintain accuracy beyond the specific conditions and datasets used for its calibration and initial validation. It assesses predictive power in new, unseen domains.

- Key Focus: The model's robustness and extrapolation capability. This is crucial for models intended for predictive use in scenarios where direct experimental data is unavailable [11].

- Common Context: The concept is heavily emphasized in data-driven fields like machine learning (ML), where it describes a model's performance on unseen test data, preventing overfitting [7]. In computational science, it relates to predicting system behavior in new domains where no physical observations exist, a process that requires careful quantification of prediction uncertainty [11].

Table 1: Core Concept Comparison

| Concept | Primary Question | Focus Area | Key Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verification | "Did we build the model right?" | Internal model implementation [10] | Ensure the model is solved and coded correctly [9] |

| Validation | "Did we build the right model?" | External model accuracy [8] | Substantiate model represents reality for its intended use [9] |

| Generalization | "Does it work in new situations?" | Model robustness and extrapolation [11] | Assess predictive power beyond calibration data [11] |

The Verification and Validation Workflow

Verification and Validation (V&V) is not a single event but an iterative process integrated throughout model development [10]. The following workflow outlines the key stages, illustrating how these activities interconnect to build a credible model.

Comparative Analysis Across Disciplines

The principles of V&V are universal, but their application varies significantly across different scientific and engineering fields. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from validation studies in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and computational biomechanics, contrasting them with approaches in drug development.

Table 2: Cross-Disciplinary Validation Examples and Performance

| Field / Model Type | Validation Metric | Reported Performance / Outcome | Key Challenge / Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFD (Wind Loads) | Base force deviation from wind tunnel data [12] | ~6% deviation using k-epsilon model with high turbulence intensity [12] | Model accuracy depends on selection of turbulence model [12] |

| CFD (Wind Pressure) | Correlation with experimental pressure coefficients [12] | R=0.98, R²=0.96 using k-omega SST model [12] | Identifying the most appropriate model for a specific flow phenomenon [12] |

| Computational Biomechanics | Cartilage contact pressure in human hip joint [13] | Validated finite element predictions against experimental data (No specific value) [13] | Creating accurate subject-specific models for clinical predictions [13] |

| AI in Drug Development (DDI Prediction) | Prediction accuracy for new drug-drug interactions [4] | Varies by model; challenges with class imbalance and new drugs [4] | Poor performance on new drugs, limited model explainability, data quality [4] |

| Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) | Match between computationally predicted and experimentally confirmed active peptides [14] | 63 peptides predicted, 54 synthesized, only 3 showed significant activity [14] | High false positive rates; mismatch between virtual screening and experimental validation [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Model V&V

Protocol for CFD Validation Using Wind Tunnel Data

This protocol, derived from a collaboration between Dlubal Software and RWTH Aachen University, provides a clear, step-by-step methodology for validating a CFD model [12].

- Define Validation Objectives: Clearly state the key parameters of interest (e.g., base forces, wind pressure coefficients) and the required level of accuracy.

- Collect Experimental Data: Obtain high-quality wind tunnel data, including the geometry of the test model (e.g., a 3D rectangular building), sensor measurements (pressure, forces), and inflow conditions (turbulence intensity) [12].

- Model Setup in CFD Software:

- Replicate the exact geometry of the experimental model.

- Define the computational domain and mesh, ensuring sufficient resolution near walls and regions of interest.

- Set boundary conditions (velocity inlet, pressure outlet) to match the wind tunnel inflow.

- Select turbulence models for testing (e.g., k-epsilon, k-omega SST) [12].

- Run Simulation: Execute the simulation until a converged solution is achieved.

- Post-Processing: Extract the same quantitative data (e.g., forces, pressure at sensor locations) from the simulation results as was measured in the experiment.

- Compare Results with Experimental Data:

- Calculate statistical measures like correlation coefficient (R) and coefficient of determination (R²) for pressure distributions [12].

- Compute percentage deviations for integrated quantities like base forces.

- Identify which turbulence model and settings yield the closest agreement.

- Documentation and Reporting: Document the entire process, including all setup parameters, comparison results, identified discrepancies, and reasons for them. This builds credibility and provides a basis for future model improvements [12].

Protocol for Validating a Machine Learning Model for Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Prediction

This protocol outlines a common workflow for developing and validating an ML model for DDI prediction, highlighting steps to assess generalization [4].

- Data Collection and Curation:

- Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering:

- Clean the data, handle missing values, and normalize features.

- Represent drugs and their properties as numerical features (e.g., molecular fingerprints, graph representations) [4].

- Dataset Splitting:

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets. The test set must be held out and only used for the final evaluation to get an unbiased estimate of generalization performance.

- A crucial practice is to perform "temporal splitting" or leave-new-drugs-out validation to test the model's ability to predict interactions for novel drugs not seen during training [4].

- Model Selection and Training:

- Select appropriate ML algorithms (e.g., supervised, semi-supervised, self-supervised, or graph-based learning) [4].

- Train the models on the training set and use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning.

- Model Validation and Performance Assessment:

- Primary Validation: Evaluate the final model on the untouched test set using metrics like AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, and recall [4].

- Generalization Assessment: Specifically test the model on the "new drugs" set to evaluate its real-world applicability. Performance often drops here, revealing the model's limitations [4].

- Analysis of Limitations and Uncertainty:

- Analyze failure modes, such as sensitivity to class imbalance or poor performance on certain drug classes.

- Acknowledge limitations like limited explainability and algorithmic bias, which are common challenges in the field [4].

For researchers embarking on model V&V, having the right "toolkit" is essential. The following table lists key computational resources and methodologies cited in modern research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational V&V

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in V&V |

|---|---|---|

| Wind Tunnel Facility [12] | Experimental Apparatus | Provides high-fidelity experimental data for validating CFD models of aerodynamic phenomena. |

| k-epsilon / k-omega SST Models [12] | Computational Model (CFD) | Turbulence models used in CFD simulations; validated against experiment to select the most accurate one. |

| Statistical Hypothesis Testing (t-test) [10] | Statistical Method | A quantitative method for accepting or rejecting a model as valid by comparing model and system outputs. |

| AlphaFold [14] | AI-Based Structure Prediction | Provides highly accurate 3D protein structures, serving as validated input for structure-based drug design (SBDD). |

| Molecular Docking & Dynamics [14] | Computational Method (CADD) | Simulates drug-target interactions; requires experimental validation to confirm predicted binding and activity. |

| Supervised & Self-Supervised ML [4] [15] | AI/ML Methodology | Used for building predictive models (e.g., for DDI); requires rigorous train-validation-test splits to ensure generalization. |

Verification, validation, and generalization are the three pillars supporting credible computational science. As summarized in this guide, verification ensures technical correctness, validation establishes real-world relevance, and generalization defines the boundaries of a model's predictive power. The comparative data and detailed protocols provided here underscore that while the concepts are universal, their successful application is context-dependent. In drug development, where the integration of AI and MIDD is accelerating innovation, a rigorous and disciplined approach to these processes is not optional—it is fundamental to making high-consequence decisions with confidence [8] [7]. The ongoing challenge for researchers is to continually refine V&V methodologies, especially in quantifying prediction uncertainty and improving the generalizability of complex data-driven models, to fully realize the potential of computational prediction in science and engineering.

Understanding Overfitting and Underfitting in High-Dimensional Biological Data

In the analysis of high-dimensional biological data, such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, the phenomena of overfitting and underfitting represent fundamental challenges that can compromise the validity and utility of computational models. Overfitting occurs when a model learns both the underlying signal and the noise in the training data, resulting in poor performance on new, unseen datasets [16]. Conversely, underfitting happens when a model is too simple to capture the essential patterns in the data, performing poorly on both training and test datasets [17]. In high-dimensional settings where the number of features (p) often vastly exceeds the number of observations (n), these problems are particularly pronounced due to what is known as the "curse of dimensionality" [18] [19].

The reliable interpretation of biomarker-disease relationships and the development of robust predictive models depend on successfully navigating these challenges [20]. This comparison guide examines the characteristics, detection methods, and mitigation strategies for overfitting and underfitting within the context of validation frameworks for computational models research, providing life science researchers and drug development professionals with practical guidance for ensuring model robustness.

Defining the Phenomena: Theoretical Foundations and Biological Consequences

Conceptual Framework

Overfitting describes the production of an analysis that corresponds too closely or exactly to a particular set of data, potentially failing to fit additional data or predict future observations reliably [16]. An overfitted model contains more parameters than can be justified by the data, effectively memorizing training examples rather than learning generalizable patterns [16]. In biological terms, an overfitted model might mistake random fluctuations, batch effects, or technical artifacts for genuine biological signals, leading to false discoveries and irreproducible findings.

Underfitting occurs when a model cannot adequately capture the underlying structure of the data, typically due to excessive simplicity [17]. An underfitted model misses important parameters or terms that would appear in a correctly specified model, such as when fitting a linear model to nonlinear biological data [16]. In practice, this means the model fails to identify true biological relationships, potentially missing valuable biomarkers or physiological interactions.

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

The concepts of overfitting and underfitting are intimately connected to the bias-variance tradeoff, a fundamental concept in statistical learning [21] [22]. Bias refers to the difference between the expected prediction of a model and the true underlying values, while variance measures how much the model's predictions change when trained on different datasets [22]. Simple models typically have high bias and low variance (underfitting), whereas complex models have low bias and high variance (overfitting) [17]. The goal is to find a balance that minimizes both sources of error, achieving what is known as a "well-fitted" model [22].

Table 1: Characteristics of Model Fitting Problems in Biological Data Analysis

| Aspect | Overfitting | Underfitting | Well-Fitted Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Complexity | Excessive complexity | Insufficient complexity | Balanced complexity |

| Training Performance | Excellent performance | Poor performance | Good performance |

| Testing Performance | Poor performance | Poor performance | Good performance |

| Bias | Low | High | Balanced |

| Variance | High | Low | Balanced |

| Biological Impact | False discoveries; irreproducible results | Missed biological relationships | Reproducible biological insights |

Diagram 1: The bias-variance tradeoff illustrates the relationship between model complexity and error.

Why High-Dimensional Biological Data is Particularly Vulnerable

High-dimensional biomedical data, characterized by a vast number of variables (p) relative to observations (n), presents unique challenges that exacerbate overfitting and underfitting problems [18]. Several characteristics of biological data contribute to this vulnerability:

- Data Sparsity: In high-dimensional spaces, data points become sparse, making it difficult to capture underlying patterns effectively with limited samples [19].

- Multicollinearity and Redundancy: High-dimensional biological data often contains correlated features (e.g., genes in the same pathway), making it challenging to distinguish each feature's unique contribution [19].

- Curse of Dimensionality: As dimensionality increases, the significance of distance between data points decreases, affecting the efficacy of distance-based algorithms [19].

- Multiple Testing Problems: With thousands or millions of simultaneous hypotheses (e.g., differential gene expression), the risk of false positives increases dramatically [18].

The STRengthening Analytical Thinking for Observational Studies (STRATOS) initiative highlights that traditional statistical methods often cannot or should not be used in high-dimensional settings without modification, as they may lead to spurious findings [18]. Furthermore, electronic health records and multi-omics data integrate diverse data types with varying statistical properties, creating additional complexity for model fitting [20].

Detection and Diagnosis: Recognizing Overfitting and Underfitting in Practice

Performance Metrics and Patterns

Detecting overfitting and underfitting requires careful evaluation of model performance across training and validation datasets:

- Overfitting Indicators: Low training error but high testing error; perfect or near-perfect performance on training data with poor performance on validation data [17]. In a practical example from immunological research, an XGBoost model with depth 6 achieved almost perfect training AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic) but significantly worse validation AUROC compared to a simpler model with depth 1 [21].

- Underfitting Indicators: Consistently high errors across both training and testing datasets; failure to capture known biological relationships [17].

Table 2: Comparative Performance Patterns Across Model Conditions

| Evaluation Metric | Overfitting | Underfitting | Well-Fitted Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Accuracy | High | Low | Moderately High |

| Validation Accuracy | Low | Low | Moderately High |

| Training Loss | Very Low | High | Moderate |

| Validation Loss | High | High | Moderate |

| Generalization Gap | Large | Small | Small |

Diagnostic Tools and Visualization

Learning curves, which plot model performance against training set size or training iterations, provide valuable diagnostic information [17]. For overfitted models, training loss decreases toward zero while validation loss increases, indicating poor generalization [21]. For underfitted models, both training and validation errors remain high even with increasing training time or data [17].

Mitigation Strategies: A Comparative Analysis of Solutions

Addressing Overfitting

Multiple strategies have been developed to prevent overfitting in high-dimensional biological data analysis:

Regularization Techniques: These methods add a penalty term to the model's loss function to discourage overcomplexity [21]. Common approaches include:

- L1 Regularization (Lasso): Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of coefficient magnitudes, encouraging sparsity and feature selection [21].

- L2 Regularization (Ridge): Adds a penalty equal to the square of coefficient magnitudes, shrinking coefficients without eliminating them [21].

- Elastic Net: Combines L1 and L2 penalties to encourage sparsity while handling correlated features [21].

Dimensionality Reduction: Methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduce the number of features while preserving essential information [19] [23].

Data Augmentation: Artificially expanding training datasets by creating modified versions of existing data, particularly valuable in genomics where datasets may be limited [24]. A 2025 study on chloroplast genomes demonstrated how generating overlapping subsequences with controlled overlaps significantly improved model performance while avoiding overfitting [24].

Ensemble Methods: Techniques like Random Forests combine multiple models to reduce variance and improve generalization [23].

Addressing Underfitting

Underfitting solutions typically focus on increasing model capacity or improving data quality:

- Model Complexity Enhancement: Switching from simple linear models to more flexible approaches like polynomial regression, decision trees, or neural networks [17].

- Feature Engineering: Creating or transforming features to provide more relevant information to the model [17].

- Reducing Regularization: Decreasing the strength of regularization penalties to allow the model more flexibility [17].

- Extended Training: Allowing more training time (epochs) for the model to learn from the data [17].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Mitigation Strategies for Overfitting and Underfitting

| Strategy | Mechanism | Best Suited Data Types | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regularization (L1/L2) | Adds penalty terms to loss function to limit complexity | High-dimensional omics data | L1 promotes sparsity; L2 handles multicollinearity |

| Cross-Validation | Evaluates model on multiple data splits to assess generalization | All biological data types | K-fold provides robust estimate; requires sufficient sample size |

| Feature Selection | Reduces dimensionality by selecting informative features | Genomics, transcriptomics | May discard weakly predictive but biologically relevant features |

| Ensemble Methods | Combines multiple models to reduce variance | Multi-omics, clinical data | Computational intensity; improved performance at cost of interpretability |

| Data Augmentation | Artificially expands training dataset | Genomics, medical imaging | Must preserve biological validity of synthetic data |

| Early Stopping | Halts training when validation performance plateaus | Neural networks, deep learning | Requires careful monitoring of validation metrics |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Cross-Validation Frameworks

Robust validation strategies are essential for detecting and preventing overfitting in high-dimensional biological data:

- K-Fold Cross-Validation: Partitions data into k subsets, using k-1 folds for training and one fold for testing, rotating through all folds [23]. This method provides a more reliable estimate of model performance than a single train-test split.

- Nested Cross-Validation: Employs an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop for hyperparameter tuning, preventing optimistic bias in performance estimates [17].

- Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation: Uses a single sample for testing in each iteration, particularly useful for small datasets but computationally intensive [23].

Performance Metrics for Biological Applications

The choice of evaluation metrics depends on the specific biological question and data characteristics:

- Classification Tasks: Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) [23].

- Regression Tasks: Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared [23].

- Specialized Biological Metrics: Q3 accuracy for protein secondary structure prediction, enrichment scores for gene set analysis [23].

Diagram 2: A robust validation workflow separating data for training, validation, and testing.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Overfitting and Underfitting

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regularization Packages | glmnet (R), scikit-learn (Python) | Implement L1, L2, and Elastic Net regularization | Generalized linear models, regression tasks |

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP | Reduce feature space while preserving structure | Exploratory analysis, preprocessing for high-dimensional data |

| Cross-Validation Frameworks | caret (R), scikit-learn (Python) | Implement k-fold and stratified cross-validation | Model evaluation, hyperparameter tuning |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forests, XGBoost, AdaBoost | Combine multiple models to improve generalization | Classification, regression with complex feature interactions |

| Neural Network Regularization | Dropout, Early Stopping | Prevent overfitting in deep learning models | Neural networks, deep learning applications |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Sliding window approaches, SMOTE | Artificially expand training datasets | Genomics, imaging, and imbalanced classification tasks |

The successful application of computational models to high-dimensional biological data requires careful attention to the balancing act between overfitting and underfitting. Based on comparative analysis of current methodologies and experimental evidence:

- For genomic sequence classification with large feature spaces, regularization methods combined with ensemble approaches like Random Forests typically provide the best balance [23].

- In transcriptomic studies with limited samples, data augmentation strategies combined with rigorous cross-validation offer promising approaches to maintain model performance [24].

- For complex deep learning applications in areas like medical imaging, dropout and early stopping techniques are essential components of the model architecture [21] [17].

The selection of appropriate strategies should be guided by the specific research question, data characteristics, and ultimate translational goals. By implementing robust validation frameworks and carefully considering the bias-variance tradeoff, researchers can develop models that not only perform well statistically but also provide biologically meaningful and clinically actionable insights.

The Impact of Data Quality and Curation on Predictive Model Performance

In computational model research, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, the focus has historically been on model architecture and algorithm selection. However, a paradigm shift toward data-centric artificial intelligence is underway, recognizing that model performance is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the underlying training data [25]. The adage "garbage in, garbage out" remains profoundly relevant in machine learning; even the most sophisticated algorithms cannot compensate for systematically flawed data. The curation process—encompassing collection, cleaning, annotation, and validation—transforms raw data into a refined resource that drives reliable model predictions [25].

This guide examines the measurable impact of data quality on predictive performance, compares data curation tools and methodologies, and provides experimental frameworks for validating data curation strategies within computational research pipelines. For researchers and scientists, understanding these relationships is crucial for developing models that are not only statistically sound but also scientifically valid and translatable to real-world applications.

Data Quality Dimensions and Metrology

Data quality is a multidimensional construct, each dimension of which directly influences model performance. Quantifiable metrics for these dimensions form the backbone of any systematic approach to data curation [26].

Table 1: Core Data Quality Dimensions and Associated Metrics

| Dimension | Description | Measurement Method | Impact on Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Degree to which all required data is present [26]. | Percentage of non-null values in a dataset [26]. | High incompleteness reduces statistical power and can introduce bias if data is not missing at random. |

| Consistency | Absence of conflicting information within or across data sources [26]. | Cross-system checks to identify conflicting values for the same entity [26]. | Inconsistencies confuse model training, leading to unstable and unreliable predictions. |

| Validity | Adherence of data to a defined syntax or format [26]. | Format checks (e.g., regex validation), range checks [26]. | Invalid data points can cause runtime errors or be processed as erroneous signals during training. |

| Accuracy | Degree to which data correctly describes the real-world value it represents [26]. | Cross-referencing with trusted sources or ground truth [26]. | Directly limits the maximum achievable model accuracy; models cannot be more correct than their training data. |

| Uniqueness | Extent to which data is free from duplicate entries [26]. | Data deduplication processes and record linkage checks [26]. | Duplicates can artificially inflate performance metrics during validation and create overfitted models. |

| Timeliness | Degree to which data is sufficiently up-to-date for its intended use [26]. | Measurement of time delay between data creation and availability [26]. | Critical for time-series models; stale data can render models ineffective in dynamic environments. |

Empirical research has quantified the performance degradation when models are trained on polluted data. A comprehensive study on tabular data found that the performance drop varies by algorithm and the type of data quality violation introduced. For instance, while tree-based models like XGBoost are relatively robust to missing values, they are highly sensitive to label noise [27] [28]. The study further distinguished between scenarios where pollution existed only in the training set, only in the test set, or in both, noting that the most significant performance losses occur when both training and test data are polluted, as this compounds error and invalidates the validation process [27] [28].

Data Curation Tools and Platforms

A robust data curation tool is indispensable for managing the data lifecycle at scale. The selection of a platform should be guided by the specific needs of the research project and the nature of the data.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Data Curation Tools for Research

| Tool | Primary Strengths | Automation & AI Features | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labellerr | High-speed, high-quality labeling; seamless MLOps integration; versatile data type support [29]. | Prompt-based labeling, model-assisted labeling, active learning automation [29]. | Large-scale projects requiring rapid iteration and integration with cloud AI platforms (e.g., GCP Vertex AI, AWS SageMaker) [29]. |

| Lightly | AI-powered data selection and prioritization; focuses on reducing labeling costs [25]. | Self-supervised learning to identify valuable data clusters [25]. | Handling massive image datasets (millions); projects where data privacy is paramount (on-prem deployment) [25] [29]. |

| Labelbox | End-to-end platform for the training data iteration loop; strong collaboration features [25] [29]. | AI-driven model-assisted labeling, quality assurance workflows [25]. | Distributed teams working on complex computer vision tasks requiring robust annotation and review cycles. |

| Scale Nucleus | Data visualization and debugging; similarity search; tight integration with Scale's labeling services [29]. | Model prediction visualization, label error identification [29]. | Teams already in the Scale ecosystem focusing on model debugging and data analysis. |

| Encord | Strong dataset visualization and management, especially for medical imaging [25]. | Model-assisted labeling, support for complex annotations [25]. | Medical AI and research involving complex data types like DICOM images and video. |

The core workflow of data curation, as implemented by these tools, involves a systematic process to convert raw data into a reliable resource. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and their interactions.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Curation Efficacy

To objectively evaluate the impact of data curation, researchers must employ rigorous, controlled experiments. The following protocol provides a framework for such validation.

Protocol: Measuring the Impact of Data Pollution on Model Performance

Objective: To quantify the performance degradation of a standard predictive model when trained on datasets with introduced quality issues.

Materials:

- Baseline Dataset: A clean, well-curated dataset (e.g., MNIST for vision, a curated public bioassay dataset for drug development).

- Model Architecture: A standard model (e.g., ResNet-50, XGBoost classifier).

- Evaluation Framework: Scripts for k-fold cross-validation and metric calculation (Accuracy, F1-Score, AUC-ROC).

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Train and validate the model on the pristine dataset to establish baseline performance.

- Controlled Pollution: Systematically introduce specific data quality issues into the training set to create polluted variants:

- Completeness: Remove a random X% of feature values or labels.

- Accuracy (Label Noise): Randomly flip Y% of training labels.

- Consistency: Introduce format inconsistencies (e.g., mixed date formats, unit conversions).

- Model Training & Evaluation: Retrain the model from scratch on each polluted training variant. Evaluate each model on the held-out, clean test set.

- Analysis: Compare the performance metrics of models trained on polluted data against the baseline. The performance delta is the cost of poor data quality.

This experimental design was effectively employed in a study cited in the search results, which found that the performance drop was highly dependent on the machine learning algorithm and the type of data quality violation [27] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for conducting rigorous data curation and validation experiments in computational research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Data Curation

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Curation Platform (e.g., Labellerr, Lightly) | Provides the interface and automation for data labeling, cleaning, and selection [25] [29]. | The primary environment for preparing training datasets for predictive models. |

| Computational Framework (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow, Scikit-learn) | Offers implementations of standard machine learning algorithms and utilities. | Used to train and evaluate models on both curated and polluted datasets to measure performance impact. |

| Validation Metric Suite (e.g., AUUC, Qini Score) | Specialized metrics for evaluating causal prediction models, which predict outcomes under hypothetical interventions [30]. | Critical for validating models in interventional contexts, such as predicting patient response to a candidate drug. |

| Propensity Model | Estimates the probability of an individual receiving a treatment given their covariates [30]. | Used in causal inference to adjust for confounding in observational data, ensuring more reliable effect estimates. |

Advanced Considerations: Causal Prediction and Model Validation

Moving beyond associative prediction, causal prediction models represent a frontier in computational science, particularly for drug development. These models aim to answer "what-if" questions, predicting outcomes under hypothetical interventions (e.g., "What would be this patient's 10-year CVD risk if they started taking statins?") [30] [31].

The validation of such models requires specialized metrics beyond conventional accuracy. The Area Under the Uplift Curve (AUUC) and the Qini score measure a model's ability to identify individuals who will benefit most from an intervention, which is crucial for optimizing clinical trials and personalized treatment strategies [30]. These methods rely on strong assumptions, including ignorability (no unmeasured confounders) and positivity (a non-zero probability of receiving any treatment for all individuals), which must be carefully considered during the data curation and model validation process [30].

For general model validation, a probabilistic metric that incorporates measurement uncertainty is recommended. This approach combines a threshold based on experimental uncertainty with a normalized relative error, providing a probability that the model's predictions are representative of the real world [32]. This is especially valuable in engineering and scientific applications where models must be trusted to inform decisions with significant consequences.

The performance of predictive models in computational research is inextricably linked to the quality of the data upon which they are trained. A systematic approach to data curation, guided by quantifiable quality metrics and implemented with modern tooling, is not a preliminary step but a core component of the model development lifecycle. As the field advances toward causal prediction and more complex interventional queries, the role of rigorous data validation and specialized assessment methodologies will only grow in importance. For researchers and drug development professionals, investing in robust data curation pipelines is, therefore, an investment in the reliability, validity, and ultimate success of their predictive models.

In the field of computational model research, the ability to distinguish between a model that has learned the underlying patterns in data versus one that has merely memorized noise is paramount. This distinction is the core of model validation, a process that determines whether a model's predictions can be trusted, especially in high-stakes environments like drug development. Validation strategies are broadly categorized into two types: in-sample validation, which assesses how well a model fits the data it was trained on, and out-of-sample validation, which evaluates how well the model generalizes to new, unseen data [33] [34]. Out-of-sample validation is often considered the gold standard for proving a model's real-world utility, as it directly tests predictive performance and helps guard against the critical pitfall of overfitting [34] [35]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two validation families, complete with experimental data and protocols, to equip researchers with the tools for robust model evaluation.

Core Concepts and Definitions

In-Sample Validation: This approach involves evaluating a model's performance using the same dataset that was used to train it. Its primary purpose is to assess the "goodness of fit"—how well the model captures the relationships and trends within the training data [34]. Common techniques include analyzing residuals to check if they exhibit random patterns and verifying that the model's underlying statistical assumptions are met [34].

Out-of-Sample Validation: This approach tests the model on a completely separate dataset, known as a holdout or test set, that was not used during training [33] [36]. Its purpose is to estimate the model's generalization error—its performance on future, unseen data [35]. This is the best method for understanding a model's predictive performance in practice and is crucial for identifying overfitting [34].

The Problem of Overfitting: Overfitting occurs when a model is excessively complex, learning not only the underlying signal in the training data but also the random noise [33] [35]. Such a model will appear to perform excellently during in-sample validation but will fail miserably when confronted with new data. The following diagram illustrates this core problem that out-of-sample validation seeks to solve.

Comparative Analysis: In-Sample vs. Out-of-Sample Validation

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each validation approach, highlighting their distinct objectives, methodologies, and interpretations.

Table 1: A direct comparison of in-sample and out-of-sample validation characteristics.

| Feature | In-Sample Validation | Out-of-Sample Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Evaluate goodness of fit to the training data [34] | Estimate generalization performance on new data [33] [34] |

| Data Used | Training dataset | A separate, unseen test or holdout dataset [36] |

| Key Interpretation | How well the model describes the seen data | How accurately the model will predict in practice [34] |

| Risk of Overfitting | High; cannot detect overfitting [33] | Low; primary defense against overfitting [34] [35] |

| Common Techniques | Residual analysis, diagnostic plots [34] | Train/test split, k-fold cross-validation, holdout method [33] [37] |

| Ideal Use Case | Model interpretation, understanding variable relationships [34] | Model selection, forecasting, and performance estimation [33] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure reproducible and credible results, researchers should adhere to structured experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for implementing both validation types.

Protocol 1: In-Sample Validation via Residual Analysis

This protocol is fundamental for diagnosing model fit and checking assumptions, particularly for linear models.

- Model Training: Train your chosen model (e.g., a linear regression) on the entire available dataset (the training set).

- Residual Calculation: For each data point in the training set, calculate the residual: the difference between the actual observed value and the value predicted by the model [34]. (Residual = Actual - Predicted).

- Residual Plotting: Create a scatter plot with the predicted values on the x-axis and the residuals on the y-axis.

- Pattern Analysis: Examine the residual plot for systematic patterns. A well-fitted model should have residuals that are randomly scattered around zero. Any discernible pattern (e.g., a curve, funnel shape) suggests the model is failing to capture some structure in the data [34].

- Assumption Checking: For linear models, check that the residuals are approximately normally distributed using a histogram or a Q-Q plot.

Protocol 2: Out-of-Sample Validation via K-Fold Cross-Validation

K-fold cross-validation is a robust method for out-of-sample evaluation that makes efficient use of limited data.

- Data Shuffling and Splitting: Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into k equal-sized subsets (called "folds"). A typical value for k is 5 or 10 [37].

- Iterative Training and Testing: For each of the k folds:

- Designate the current fold as the test set.

- Use the remaining k-1 folds combined as the training set.

- Train the model on the training set.

- Evaluate the model on the test set and record the chosen performance metric (e.g., accuracy, mean squared error).

- Performance Averaging: Calculate the average of the k performance scores obtained from the test folds. This average provides a more reliable estimate of the model's out-of-sample performance than a single train/test split [33] [37].

The workflow for this protocol, including the critical step of performance averaging, is illustrated below.

Application in Drug Development and Biomarker Research

The principles of model validation are critically applied in pharmaceutical research, where the terminology aligns with the concepts of in-sample and out-of-sample evaluation.

Analytical Method Validation vs. Clinical Qualification: In drug development, analytical method validation is akin to in-sample validation. It is the process of assessing an assay's performance characteristics (e.g., precision, accuracy, linearity) under controlled conditions to ensure it generates reliable and reproducible data [38] [39]. Clinical qualification, conversely, is an out-of-sample process. It is the evidentiary process of linking a biomarker with biological processes and clinical endpoints in broader, independent patient populations [38].

Fit-for-Purpose Framework: The validation approach is tailored to the biomarker's stage of development. An exploratory biomarker used for internal decision-making (e.g., in preclinical studies) may require less rigorous out-of-sample validation. In contrast, a known valid biomarker intended for patient selection or as a surrogate endpoint must undergo extensive out-of-sample testing across multiple independent sites to achieve widespread acceptance [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Robust Validation

Beyond methodology, successful validation requires careful consideration of the materials and data used. The following table details key "research reagents" in the context of computational model validation.

Table 2: Key components and their functions in a model validation workflow.

| Item / Component | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Training Dataset | The subset of data used to build and train the computational model. It is the sole dataset used for in-sample validation [36] [35]. |

| Holdout Test Dataset | A separate subset of data, withheld from training, used exclusively for the final out-of-sample evaluation of model performance [40]. |

| Cross-Validation Folds | The k mutually exclusive subsets of the data created to implement k-fold cross-validation, enabling robust out-of-sample estimation without a single fixed holdout set [33] [37]. |

| Reference Standards (for bio-analytical methods) | Materials of known quantity and activity used during analytical method validation to establish accuracy and precision, serving as a benchmark for in-sample assessment [39] [41]. |

| Independent Validation Cohort | An entirely separate dataset, often from a different clinical site or study, used for true external out-of-sample validation (OOCV). This is the strongest test of generalizability [38] [42]. |

In-sample and out-of-sample validation are not competing strategies but complementary stages in a rigorous model evaluation pipeline. In-sample validation is a necessary first step for diagnosing model fit and understanding relationships within the data at hand. However, reliance on in-sample metrics alone is dangerously optimistic and can lead to deployed models that fail in practice. Out-of-sample validation, through methods like k-fold cross-validation and external testing on independent cohorts, is the indispensable tool for estimating real-world performance, preventing overfitting, and building trustworthy models. For researchers in drug development and computational science, a disciplined workflow that prioritizes out-of-sample evidence is the foundation for making credible predictions and reliable decisions.

Core Validation Techniques and Their Application in Biomedical Research

A Deep Dive into K-Fold Cross-Validation for Reliable Performance Estimation

In computational model research, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, accurately estimating a model's performance on unseen data is paramount. The primary challenge lies in balancing model complexity to capture underlying patterns without overfitting the training data, which leads to poor generalization. Traditional single train-test splits, while computationally inexpensive, often provide unreliable and optimistic performance estimates due to their sensitivity to how the data is partitioned [43] [44]. This variability can obscure the true predictive capability of a model, potentially leading to flawed scientific conclusions and costly decisions in the research pipeline.

K-Fold Cross-Validation (K-Fold CV) has emerged as a cornerstone validation technique to address this critical issue of performance estimation. It is a resampling procedure designed to evaluate how the results of a statistical analysis will generalize to an independent dataset [37]. By systematically partitioning the data and iteratively using each partition for validation, it provides a more robust and reliable estimate of model performance than a single hold-out set [45] [46]. This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of K-Fold CV against other validation strategies, detailing its protocols, variations, and application within computational model research.

The K-Fold Cross-Validation Protocol: A Detailed Methodology

The core principle of K-Fold CV is to split the dataset into K distinct subsets, known as "folds". The model is then trained and evaluated K times. In each iteration, one fold is designated as the test set, while the remaining K-1 folds are aggregated to form the training set. After K iterations, each fold has been used as the test set exactly once. The final performance metric is the average of the K evaluation results, providing a single, aggregated estimate of the model's predictive ability [45] [37].

Step-by-Step Experimental Workflow

The standard K-Fold CV workflow can be broken down into the following detailed steps [45] [46] [47]:

- Define K and Prepare Data: Choose an integer K, representing the number of folds. Common choices are 5 or 10. The dataset D, with a total of N samples, is then randomly shuffled to minimize any order-based bias.

- Partition into Folds: Split the shuffled dataset D into K subsets (F₁, F₂, ..., Fₖ) of approximately equal size. Each subset is a fold.

- Iterative Training and Validation: For each iteration i = 1 to K:

- Assign Sets: Set the test set (Dtest) to be fold Fi. The training set (Dtrain) is the union of all other folds: Dtrain = D \ Fi.

- Train Model: Train the chosen machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) on the Dtrain dataset.

- Validate Model: Use the trained model to make predictions on the Dtest (hold-out) set.

- Record Performance: Calculate the chosen performance metric (e.g., Accuracy, RMSE, AUROC) for this iteration, denoted as Mi.

- Aggregate Results: After all K iterations, compute the final performance estimate by averaging the K individual metrics: Final Performance = (1/K) * Σ M_i. The standard deviation of these metrics can also be calculated to assess the stability of the model's performance across different data splits.

This process ensures that every observation in the dataset is used for both training and testing, maximizing data utility and providing a more dependable performance estimate [46].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data partitioning of the K-Fold Cross-Validation process.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Strategies

Selecting an appropriate validation strategy is a fundamental step in model evaluation. The choice involves a trade-off between computational cost, the bias of the performance estimate, and the variance of that estimate. The table below provides a structured comparison of K-Fold CV against other common validation methods.

Table 1: Objective Comparison of Model Validation Techniques

| Validation Technique | Key Methodology | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [45] [37] | Splits data into K folds; each fold serves as test set once. | Reduced bias compared to holdout; efficient data use; more reliable performance estimate [46]. | Higher computational cost; not suitable for raw time-series data [45]. | General-purpose model evaluation and hyperparameter tuning with limited data. |

| Hold-Out (Train-Test Split) [43] [37] | Single random split into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20). | Computationally fast and simple. | High variance in performance estimate; inefficient use of data [44]. | Initial model prototyping or with very large datasets. |

| Leave-One-Out CV (LOOCV) [46] [37] | A special case of K-Fold where K = N (number of samples). | Low bias; uses nearly all data for training. | Very high computational cost; high variance in estimate [44]. | Very small datasets where data is extremely scarce. |

| Stratified K-Fold CV [46] [37] | Preserves the percentage of samples for each class in every fold. | More reliable for imbalanced datasets; reduces bias in class distribution. | Similar computational cost to standard K-Fold. | Classification problems with imbalanced class labels. |

| Time Series Split [45] [46] | Creates folds based on chronological order; training on past, testing on future. | Respects temporal dependencies; prevents data leakage. | Cannot shuffle data; requires careful parameterization. | Time-series forecasting and financial modeling [44]. |

Supporting Experimental Evidence

Empirical studies across various domains consistently demonstrate the value of K-Fold CV. A 2025 study on bankruptcy prediction using Random Forest and XGBoost employed a nested cross-validation framework to assess K-Fold CV's validity. The research concluded that, on average, K-Fold CV is a sound technique for model selection, effectively identifying models with superior out-of-sample performance [48]. However, the study also highlighted an important caveat: the success of the method can be sensitive to the specific train/test split, with the variability in model selection outcomes being largely influenced by statistical differences between the training and test datasets [48].

In cheminformatics, a large-scale 2023 study evaluated K-Fold CV ensembles for uncertainty quantification on 32 diverse datasets. The research involved multiple modeling techniques (including DNNs, Random Forests, and XGBoost) and molecular featurizations. It found that ensembles built via K-Fold CV provided robust performance and reliable uncertainty estimates, establishing them as a "golden standard" for such tasks [49]. This underscores the method's applicability in drug development contexts, such as predicting physicochemical properties or biological activities.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Implementing K-Fold CV and related validation strategies requires a set of core software tools and libraries. The table below details key "research reagents" for computational scientists.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Model Validation

| Tool / Library | Primary Function | Key Features for Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scikit-Learn (Python) [45] [50] | Machine learning library. | Provides KFold, StratifiedKFold, cross_val_score, and GridSearchCV for easy implementation of various CV strategies. |

General-purpose model building, evaluation, and hyperparameter tuning. |

| XGBoost (R, Python, etc.) [48] | Gradient boosting framework. | Native integration with cross-validation for early stopping and hyperparameter tuning, enhancing model generalization. | Building high-performance tree-based models for structured data. |

| Ranger (R) [48] | Random forest implementation. | Efficiently trains Random Forest models, which are often evaluated using K-Fold CV to ensure robust performance. | Creating robust ensemble models for classification and regression. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks. | Enable custom implementation of K-Fold CV loops for training and evaluating complex neural networks. | Deep learning research and model development on large-scale data. |

| Pandas & NumPy (Python) [50] [44] | Data manipulation and numerical computing. | Facilitate data cleaning, transformation, and array operations necessary for preparing data for cross-validation splits. | Data preprocessing and feature engineering pipelines. |

Advanced Considerations and Variants of K-Fold CV

The Critical Choice of K

The value of K is not arbitrary; it directly influences the bias-variance tradeoff of the performance estimate. A lower K (e.g., 2 or 3) means less computational effort but also larger training sets. However, it can lead to a higher variance in the test performance because the evaluation is based on a smaller number of validation data points. Conversely, a higher K (e.g., 15 or 20) leads to more stable performance estimates (lower variance) but with increased computational cost and potential for higher bias, as the training sets across folds become more similar to each other [44] [47]. Conventional wisdom suggests K=5 or K=10 as a good compromise, often resulting in a test error estimate that neither suffers from excessively high bias nor very high variance [45] [44].

Recent methodological research underscores that the optimal K is context-dependent. A 2025 paper proposed a utility-based framework for determining K, arguing that conventional choices implicitly assume specific data characteristics. Their analysis showed that the optimal K depends on both the dataset and the model, suggesting that a principled, data-driven selection can lead to more reliable performance comparisons [51].

Specialized Variants for Specific Data Types

The standard K-Fold CV procedure assumes that data points are independently and identically distributed. This assumption is violated in certain data types, necessitating specialized variants:

- Stratified K-Fold: Crucial for classification tasks with imbalanced datasets. It ensures that each fold has the same proportion of class labels as the original dataset, preventing a scenario where a fold contains very few instances of a minority class, which would lead to an unreliable performance estimate for that class [46] [37].

- Time Series Cross-Validation: For time-dependent data, standard random shuffling would leak future information into the past, creating an invalid and overly optimistic model. This variant involves creating folds in a forward-chaining manner. For example, the model is trained on data up to time

tand validated on data at timet+1. This simulates a real-world scenario where the model predicts the future based on the past [45] [46]. - Nested Cross-Validation: When the goal is both model selection (or hyperparameter tuning) and performance estimation, a single K-Fold CV is insufficient as it can lead to optimistically biased estimates. Nested CV uses an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop for model selection, providing an almost unbiased estimate of the true performance of a model with its tuning process [48]. The following diagram visualizes this sophisticated workflow.

K-Fold Cross-Validation stands as a robust and essential technique for reliable performance estimation in computational model research. Its systematic approach to data resampling provides a more trustworthy evaluation of a model's generalizability compared to simpler hold-out methods, which is critical for making informed decisions in fields like drug development. While it comes with a higher computational cost, its advantages—including efficient data utilization, reduced bias, and the ability to provide a variance estimate—make it a superior choice for model assessment and selection in most non-sequential data scenarios. Researchers should, however, be mindful of its limitations and opt for specialized variants like Stratified K-Fold or Time Series Split when dealing with imbalanced or temporal data. By integrating K-Fold CV and its advanced forms like Nested CV into their validation workflows, scientists and researchers can ensure their models are not only accurate but also truly predictive, thereby enhancing the validity and impact of their computational research.

In computational model research, particularly within domains like drug development and biomedical science, the reliability of model evaluation is paramount. Validation strategies must not only assess performance but also ensure that predictive accuracy is consistent across all biologically or clinically relevant categories. Standard cross-validation techniques operate under the assumption that random sampling will create representative data splits, a presumption that fails dramatically when dealing with inherently imbalanced datasets. Such imbalances are fundamental characteristics of critical research areas, including rare disease detection, therapeutic outcome prediction, and toxicology assessment, where minority classes represent the most scientifically significant cases.

Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation emerges as a methodological refinement designed specifically to address this challenge. By preserving original class distribution in every fold, it provides a more statistically sound foundation for evaluating model generalization. This approach is particularly crucial for research applications where model deployment decisions—such as advancing a drug candidate or validating a diagnostic marker—depend on trustworthy performance estimates. This guide objectively examines Stratified K-Fold alongside alternative validation methods, providing experimental data and protocols to inform rigorous model selection in scientific computational research.

Theoretical Foundation: The Problem of Class Imbalance

The Statistical Challenge in Research Data

In scientific datasets, the class of greatest interest is often the rarest. For instance, in drug discovery, the number of compounds that successfully become therapeutics is vastly outnumbered by those that fail. This skewed distribution creates substantial problems for standard validation approaches that evaluate overall accuracy without regard for class-specific performance [52]. A model that simply predicts the majority class for all samples can achieve misleadingly high accuracy while failing completely on its primary scientific objective—identifying the minority class.

Limitations of Standard K-Fold Cross-Validation

Standard K-Fold Cross-Validation randomly partitions data into K subsets (folds), using K-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for testing in an iterative process [53]. While effective for balanced datasets, this approach introduces significant evaluation variance with imbalanced data because random sampling may create folds with unrepresentative class distributions [54]. In extreme cases, some test folds may contain zero samples from the minority class, making meaningful performance assessment impossible for the very categories that often hold the greatest research interest [52].

Table: Comparison of Fold Compositions in a Hypothetical Dataset (90% Class 0, 10% Class 1)

| Fold | Standard K-Fold Class 0 | Standard K-Fold Class 1 | Stratified K-Fold Class 0 | Stratified K-Fold Class 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 2 | 18 | 2 |

| 2 | 18 | 3 | 18 | 2 |

| 3 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 2 |

| 4 | 18 | 3 | 18 | 2 |

| 5 | 18 | 2 | 18 | 2 |

The mathematical objective of Stratified K-Fold is to maintain the original class prior probability in each fold. Formally, for a dataset with class proportions P(c) for each class c, each fold F_i aims to satisfy:

P(c | F_i) ≈ P(c) for all classes c and all folds i [54]

This preservation of conditional distribution ensures that each model evaluation during cross-validation reflects the true challenge of the classification task, providing more reliable estimates of real-world performance [54].

Methodological Comparison of Cross-Validation Techniques

Various cross-validation techniques exist for model evaluation, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The selection of an appropriate method depends on dataset characteristics, including size, distribution, and underlying structure [55].

Table: Comparison of Cross-Validation Techniques for Classification Models

| Technique | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hold-Out | Single random split into training and test sets | Computationally efficient; simple to implement | High variance; dependent on single random split | Very large datasets; initial model prototyping |

| Standard K-Fold | Random division into K folds; each serves as test set once | More reliable than hold-out; uses all data for testing | Unrepresentative folds with imbalanced data | Balanced datasets; general-purpose validation |

| Stratified K-Fold | Preserves class distribution in each fold | Reliable for imbalanced data; stable performance estimates | Not applicable to regression tasks | Imbalanced classification; small datasets |

| Leave-One-Out (LOOCV) | Each sample individually used as test set | Low bias; maximum training data usage | Computationally expensive; high variance | Very small datasets |

| Time Series Split | Maintains temporal ordering of observations | Respects time dependencies; prevents data leakage | Not applicable to non-sequential data | Time series; longitudinal studies |

Specialized Validation Strategies for Research Applications

Beyond standard approaches, specialized validation methods address particular research data structures. Repeated Stratified K-Fold performs multiple iterations of Stratified K-Fold with different randomizations, further reducing variance in performance estimates [56]. For temporal biomedical data, such as longitudinal patient studies, Time Series Cross-Validation maintains chronological order, ensuring that models are never tested on data preceding their training period [55].

Stratified Shuffle Split offers an alternative for scenarios requiring custom train/test sizes while maintaining class balance, generating multiple random stratified splits with defined dataset sizes [52]. This flexibility can be particularly valuable during hyperparameter tuning or when working with composite validation protocols in computational research.

Experimental Protocol and Implementation

Standardized Experimental Framework

To objectively compare cross-validation techniques, we established a consistent experimental protocol using synthetic imbalanced datasets generated via scikit-learn's make_classification function. This approach allows controlled manipulation of class imbalance ratios while maintaining other dataset characteristics [52].

Dataset Generation Parameters:

- Samples: 1,000

- Features: 20

- Informative features: 5

- Redundant features: 2

- Class imbalance ratios: 90:10, 95:5, 99:1

- Random state: 42 (for reproducibility)

Model Training Protocol:

- Apply each cross-validation technique with identical model architectures

- Use Logistic Regression with fixed regularization (C=1.0)

- Implement maximum iterations (1000) to ensure convergence

- Maintain consistent random state for weight initialization