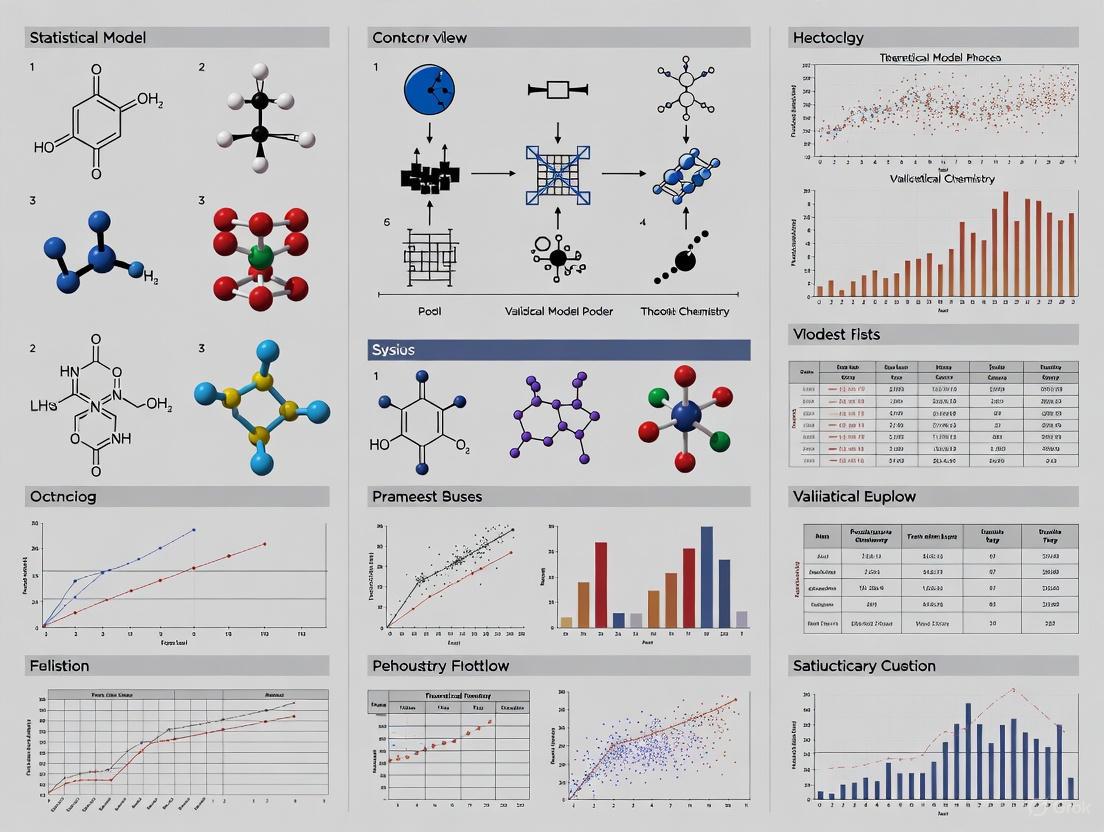

Statistical Model Validation: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Clinicians

This article provides a comprehensive overview of statistical model validation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Statistical Model Validation: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of statistical model validation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It bridges foundational concepts with advanced methodologies, addressing the critical need for robust validation in high-stakes biomedical research. The scope ranges from establishing conceptual soundness and data integrity to applying specialized techniques for clinical and spatial data, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and implementing strategic, business-aligned validation frameworks. The guide synthesizes modern approaches, including AI-driven validation and real-time monitoring, to ensure models are not only statistically sound but also reliable, fair, and effective in real-world clinical and research applications.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Business Alignment of Model Validation

Model validation has traditionally been viewed as a technical checkpoint in the development lifecycle, often focused on statistical metrics and compliance. However, a fundamental paradigm shift is emerging, recasting validation not as a bureaucratic hurdle but as a core business strategy [1]. This strategic approach ensures that mathematical models—increasingly central to decision-making in fields like drug development—are not only statistically sound but also robust, reliable, and relevant to business objectives. The traditional model validation process suffers from two critical flaws: validators often miss failure modes that genuinely threaten business goals because they focus on technical metrics, and they generate endless technical criticisms irrelevant to business decisions, creating noise that erodes stakeholder confidence [1]. In high-stakes environments like pharmaceutical development, where models predict drug efficacy, patient safety, and clinical outcomes, this shift from bottom-up technical testing to a top-down business strategy is essential for managing risk and enabling confident deployment.

A New Paradigm: From Technical Checkpoint to Business Discipline

The "Model Hacking" Framework

The "top-down hacking approach" proposes a proactive, adversarial methodology that systematically uncovers model vulnerabilities in business-relevant scenarios [1]. This framework begins with the business intent and clear definitions of what constitutes a model failure from a business perspective. It then translates these business concerns into technical metrics, employing comprehensive vulnerability testing. This stands in contrast to traditional validation, which is often focused on statistical compliance. The new model prioritizes discovering weaknesses where they matter most—in scenarios that could actually harm the business—and translates findings into actionable risk management strategies [1]. This transforms model validation from a bottleneck into a strategic enabler, providing clear business risk assessments that support informed decision-making.

Core Strategic Dimensions

The business-focused validation framework assesses models across five critical dimensions [1]:

- Heterogeneity: Does model performance degrade significantly for specific data subgroups or patient populations?

- Resilience: How does the model perform under data drift or unexpected shifts in the input data distribution?

- Reliability: Are the model's uncertainty estimates accurate and trustworthy?

- Robustness: How sensitive are the model's predictions to small, adversarial perturbations in the input data?

- Fairness: Does the model produce biased outcomes against any protected or sensitive group?

Table 1: Strategic Dimensions of Model Validation

| Dimension | Business Impact Question | Technical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneity | Will the drug dosage model work equally well for all patient subpopulations? | Performance consistency across data segments |

| Resilience | Can the clinical outcome predictor handle real-world data quality issues? | Stability under data drift and outliers |

| Reliability | Can we trust the model's confidence interval for a drug's success probability? | Accuracy of uncertainty quantification |

| Robustness | Could minor lab measurement errors lead to dangerously incorrect predictions? | Sensitivity to input perturbations |

| Fairness | Does the patient selection model systematically disadvantage elderly patients? | Absence of bias against protected groups |

Foundational Principles and Terminology

The Core Objective: Predicting Quantities of Interest

At its core, predictive modeling aims to obtain quantitative predictions regarding a system of interest. The model's primary objective is to predict a Quantity of Interest (QoI), which is a specific, relevant output measured within a physical (or biological) system [2]. The validation process exists to quantify the error between the model and the reality it describes with respect to this QoI. The design of validation experiments must therefore be directly relevant to the objective of the model—predicting the QoI at a prediction scenario [2]. This is particularly critical when the prediction scenario cannot be carried out in a controlled environment or when the QoI cannot be readily observed.

The Validation Experiment

A validation experiment involves the comparison of experimental data (outputs from the system of interest) and model predictions, both obtained at a specific validation scenario [2]. The central challenge is to design this experiment so it is truly representative of the prediction scenario, ensuring that the various hypotheses on the model are similarly tested in both. The methodology involves computing influence matrices that characterize the response surface of given model functionals. By minimizing the distance between these influence matrices, one can select a validation experiment most representative of the prediction scenario [2].

A Comprehensive Validation Methodology

The Four Pillars of Model Validation

For complex models, validation is not a single activity but a continuous process integrated throughout the software lifecycle. A robust validation framework should incorporate at least four distinct forms of testing [3]:

- Component Testing: This involves checking that individual software components and algorithms perform as intended. It includes fundamental verification, such as ensuring a simulation with a known input produces the mathematically expected output. For example, verifying that a model with an unimpeded travel rate of 1 metre per second correctly requires 100 seconds to travel 100 metres [3].

- Functional Validation: This step checks that the model possesses the range of capabilities required for its specific tasks. For a clinical trial model, this might involve testing its ability to handle different trial phases, patient dropout scenarios, and various endpoint analyses [3].

- Qualitative Validation: This form of validation compares the nature of the model's predicted behavior with informed, expert expectations. It demonstrates that the capabilities built into the model can produce realistic, plausible outcomes, even if it does not provide strict quantitative measures [3].

- Quantitative Validation: This is the systematic comparison of model predictions with reliable, experimental data. It requires careful attention to data integrity, experimental suitability, and repeatability. A robust quantitative validation includes both the use of historical data and "blind predictions," where simulations are performed prior to knowledge of the experimental results [3].

Essential Data Validation Techniques

Underpinning the broader model validation process are specific, technical data validation techniques that ensure the quality of the data used for both model training and validation. The following techniques are critical for maintaining data integrity [4]:

- Range Validation: Confirms that numerical, date, or time-based data falls within a predefined, acceptable spectrum. This prevents illogical data (e.g., a negative age) from entering the system [4].

- Format Validation (Pattern Matching): Verifies that data adheres to a specific structural rule using methods like regular expressions. It is indispensable for validating structured text data like patient IDs or lab codes [4].

- Type Validation: Ensures a data value conforms to its expected data type (e.g., number, string, date), preventing data corruption and runtime errors [4].

- Constraint Validation: Enforces complex business rules and data integrity requirements, such as uniqueness (e.g., no duplicate patient records) or referential integrity (e.g., ensuring a lab result links to a valid patient profile) [4].

Advanced Analytical Methods for Validation

The validation process is supported by a suite of advanced data analysis methods. These techniques help uncover patterns, test hypotheses, and ensure the model's predictive power is genuine [5].

- Regression Analysis: Models the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It is crucial for understanding how changes in input parameters affect the QoI and for calibrating model outputs [5].

- Factor Analysis: A statistical method used for data reduction and to identify underlying latent structures in a dataset. It can help in understanding the fundamental factors driving the observed outcomes in a clinical or biological system [5].

- Cohort Analysis: A subset of behavioral analytics that groups individuals (e.g., patients) sharing common characteristics over a specific period. This method is vital for evaluating lifecycle patterns and understanding how behaviors or outcomes differ across patient subgroups [5].

- Monte Carlo Simulation: A computational technique that uses random sampling to estimate complex mathematical problems. It is extensively used in validation to quantify uncertainty and assess risks by modeling thousands of possible scenarios and providing a range of potential outcomes [5].

Table 2: Key Data Analysis Methods for Model Validation

| Method | Primary Purpose in Validation | Example Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Regression Analysis | Model relationships between variables and predict outcomes. | Predicting clinical trial success based on preclinical data. |

| Factor Analysis | Identify underlying, latent variables driving observed outcomes. | Uncovering unobserved patient factors that influence drug response. |

| Cohort Analysis | Track and compare the behavior of specific groups over time. | Comparing long-term outcomes for patients on different dosage regimens. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Quantify uncertainty and model risk across many scenarios. | Estimating the probability of meeting primary endpoints given variability in patient response. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Model Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Sobol Indices | Variance-based sensitivity measures used to quantify the contribution of input parameters to the output variance of a model [2]. |

| Influence Matrices | Mathematical constructs that characterize the response surface of model functionals; used to design optimal validation experiments [2]. |

| JSON Schema / Pydantic | Libraries for enforcing complex data type and structure rules in APIs and data pipelines, ensuring data integrity for model inputs [4]. |

| Regular Expression (Regex) | A pattern-matching language used for robust format validation of structured text data (e.g., patient IDs, lab codes) [4]. |

| libphonenumber / Apache Commons Validator | Pre-validated libraries for standardizing and validating international data formats, reducing implementation error [4]. |

| Active Subspace Method | A sensitivity analysis technique used to identify important directions in the parameter space for reducing model dimensionality [2]. |

Model validation is undergoing a necessary and critical evolution. Moving beyond a narrow focus on technical metrics towards a comprehensive, business-strategic discipline is paramount for organizations that rely on predictive models for critical decision-making. By adopting a top-down approach that starts with business intent, employs rigorous methodologies like the four pillars of validation, and leverages advanced analytical techniques, researchers and drug development professionals can transform validation from a perfunctory check into a powerful tool for risk management and strategic enablement. This ensures that models are not only statistically valid but also resilient, reliable, and—most importantly—aligned with the core objective of improving human health.

In the rigorous world of statistical modeling, particularly within drug development and financial risk analysis, the validity of a model's output is paramount. This validity rests upon two critical, interdependent pillars: conceptual soundness and data quality. A model, no matter how sophisticated its mathematics, cannot produce trustworthy results if it is built on flawed logic or fed with poor-quality data. The process of evaluating these pillars is known as statistical model validation, the task of evaluating whether a chosen statistical model is appropriate for its intended purpose [6]. It is crucial to understand that a model valid for one application might be entirely invalid for another, underscoring the importance of a context-specific assessment [6]. This guide provides a technical overview of the methodologies and protocols for ensuring both conceptual soundness and data quality, framed within the essential practice of model validation.

The Foundation of Conceptual Soundness

Conceptual soundness verifies that a model is based on a solid theoretical foundation, employs appropriate statistical methods, and is logically consistent with the phenomenon it seeks to represent.

Core Principles and Definition

A conceptually sound model is rooted in relevant economic theory, clinical science, or industry practice, and its design choices are logically justified [7]. For example, the Federal Reserve's stress-testing models are explicitly developed by drawing on "economic research and industry practice" to ensure their theoretical robustness [7]. The core of conceptual soundness involves testing the model's underlying assumptions and examining whether the available data and related model outputs align with these established principles [6].

Methodologies for Assessment

Assessing conceptual soundness involves several key activities:

Residual Diagnostics: This involves analyzing the difference between the actual data and the model's predictions to check for effectively random errors. Key diagnostic plots include [6]:

- Residuals vs. Fitted Values Plot: Checks for non-linearity and non-constant variance (heteroscedasticity). An ideal pattern is a horizontal band of points randomly scattered around zero.

- Normal Q-Q Plot: Assesses the normality assumption of residuals. Deviations from the straight diagonal line indicate violations of normality.

- Scale-Location Plot: Visualizes homoscedasticity more clearly.

- Residuals vs. Leverage Plot: Identifies influential data points that disproportionately impact the model's results.

Handling Overfitting and Underfitting: The bias-variance trade-off is central to conceptual soundness. Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex and captures noise specific to the training data, leading to poor performance on new data. Underfitting occurs when a model is too simple to capture the underlying trend [8]. Techniques like cross-validation are used to find a model that balances these two extremes [8].

Experimental Protocols for Residual Analysis

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing residual diagnostics, a key experiment in validating a model's conceptual soundness.

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for Residual Diagnostics in Regression Analysis

| Step | Action | Purpose | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Fitting | Run the regression analysis on the training data. | Generate predicted values and calculate residuals (observed - predicted). | Fitted model, predicted values, residual values. |

| 2. Plot Generation | Create the four standard diagnostic plots: Residuals vs. Fitted, Normal Q-Q, Scale-Location, and Residuals vs. Leverage. | Visually assess violations of model assumptions including linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and influence. | Four diagnostic plots. |

| 3. Plot Inspection | Systematically examine each plot for patterns that deviate from the ideal. | Identify specific issues like non-linearity (U-shaped curve), heteroscedasticity (fan-shaped pattern), non-normality (S-shaped Q-Q plot), or highly influential points. | List of potential model deficiencies. |

| 4. Autocorrelation Testing | For time-series data, plot the Autocorrelation Function (ACF) and/or perform a Ljung-Box test. | Check for serial correlation in the residuals, which violates the independence assumption. | ACF plot, Ljung-Box test p-value. |

| 5. Issue Remediation | Address identified problems using methods such as variable transformation, adding non-linear terms, or investigating outliers. | Improve model specification and correct for assumption violations. | A refined and more robust model. |

| 6. Re-run Diagnostics | Repeat the diagnostic process on the refined model. | Confirm that the changes have successfully resolved the identified issues. | A new set of diagnostic plots for the final model. |

Visualization of the Residual Diagnostic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for performing residual diagnostics, as outlined in the experimental protocol above.

The Imperative of High-Quality Data

Data quality is the second critical pillar. Even a perfectly conceived model will fail if the data used to build and feed it is deficient. High-quality data is characterized by its completeness, accuracy, and relevance.

Robust data governance is essential, involving clear policies for data collection, processing, and review to ensure quality controls are documented and followed [9]. In regulatory environments, the Federal Reserve employs detailed data from regulatory reports (FR Y-9C, FR Y-14) and proprietary third-party data to develop its models [7]. Similarly, in drug development, the use of diverse Real-World Data (RWD) sources—such as electronic health records (EHRs), wearable devices, and patient registries—is becoming increasingly common to complement traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [10].

Protocols for Data Validation and Treatment of Deficiencies

Regulatory bodies provide clear frameworks for handling data deficiencies. Firms are responsible for the completeness and accuracy of their submitted data, and regulators perform their own validation checks [7]. The following table summarizes the standard treatments for common data quality issues.

Table 2: Protocols for Handling Data Quality Deficiencies

| Data Issue Type | Description | Recommended Treatment | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immaterial Portfolio | A portfolio that does not meet a defined materiality threshold. | Assign the median loss rate from firms with material portfolios. | Promotes consistency and avoids unnecessary modeling complexity. |

| Deficient Data Quality | Data for a portfolio is too deficient to produce a reliable model estimate. | Assign a high loss rate (e.g., 90th percentile) or conservative revenue rate (e.g., 10th percentile). | Aligns with the principle of conservatism to mitigate risk from poor data. |

| Missing/Erroneous Inputs | Specific data inputs to models are missing or reported incorrectly. | Assign a conservative value (e.g., 10th or 90th percentile) based on all available data from other firms. | Allows the existing modeling framework to be used while accounting for uncertainty. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Model Validation

The following table details essential analytical "reagents" and tools used by researchers and model validators to assess and ensure model quality.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Model Validation

| Tool / Technique | Function / Purpose | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Validation (CV) | Iteratively refits a model, leaving out a sample each time to test prediction on unseen data; used to detect overfitting and estimate true prediction error [6] [8]. | Machine Learning, Statistical Modeling, Drug Development. |

| Residual Diagnostic Plots | A set of graphical tools (e.g., Q-Q, Scale-Location) used to visually assess whether a regression model's assumptions are met [6]. | Regression Analysis, Econometrics, Predictive Biology. |

| Propensity Score Modeling | A Causal Machine Learning (CML) technique used with RWD to mitigate confounding by estimating the probability of treatment assignment, given observed covariates [10]. | Observational Studies, Pharmacoepidemiology, Health Outcomes Research. |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Estimates the relative quality of statistical models for a given dataset, balancing model fit with complexity [6]. | Model Selection, Time-Series Analysis, Ecology. |

| Back Testing & Stress Testing | Back Testing: Validates model accuracy by comparing forecasts to actual outcomes. Stress Testing: Assesses model performance under adverse scenarios [9]. | Financial Risk Management (e.g., CECL), Regulatory Capital Planning. |

Advanced Integration: Causal Machine Learning in Drug Development

The integration of high-quality RWD with Causal Machine Learning (CML) represents a cutting-edge application of these pillars. CML methods are designed to estimate treatment effects from observational data, where randomization is not possible. They address the confounding and biases inherent in RWD, thereby strengthening the conceptual soundness of causal inferences drawn from it [10].

Key CML methodologies include:

- Advanced Propensity Score Modelling: Using ML algorithms like boosting or tree-based models to better handle non-linearity and complex interactions in estimating propensity scores, outperforming traditional logistic regression [10].

- Doubly Robust Inference: Combining models for the treatment (propensity score) and the outcome to produce a causal estimate that remains consistent even if one of the two models is misspecified [10].

- Bayesian Integration Frameworks: Using Bayesian power priors and other methods to integrate and weight evidence from both RCTs and RWD, facilitating a more comprehensive drug effect assessment [10].

Visualization of the RWD/CML Integration Workflow

The following diagram outlines the workflow for integrating Real-World Data with Causal Machine Learning to enhance drug development.

The establishment of conceptual soundness and high-quality data as the foundational pillars of statistical model validation is non-negotiable across regulated industries. From the residual diagnostics that scrutinize a model's internal logic to the rigorous governance of data inputs and the advanced application of Causal Machine Learning, each protocol and methodology serves to build confidence in a model's outputs. For researchers and drug development professionals, a steadfast commitment to these principles is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental requirement for generating credible, actionable evidence that can withstand regulatory scrutiny and ultimately support critical decisions in science and finance.

In the field of drug development, the validation of statistical models is paramount for ensuring efficacy, safety, and regulatory success. Traditional approaches often falter due to a fundamental misalignment between technical execution and business strategy. This guide explores the critical failure points of a purely bottom-up, technically-focused validation process and advocates for the superior efficacy of an integrated, top-down strategy. By re-framing validation as a business-led initiative informed by technical rigor, organizations can significantly improve model reliability, accelerate development timelines, and enhance the probability of regulatory and commercial success.

The High Cost of Validation Failure

Inaccurate forecasting and poor model validation are not merely technical setbacks; they carry significant financial and strategic consequences. Organizations with poor forecasting accuracy experience 26% higher sales and marketing costs due to misaligned resource allocation and 31% higher sales team turnover resulting from missed targets [11]. Within drug development, these miscalculations can derail clinical programs, erode investor confidence, and ultimately delay life-saving therapies from reaching patients.

The root cause often lies in a one-dimensional approach. A bottom-up validation process, built solely on technical metrics without strategic context, may produce a model that is statistically sound yet commercially irrelevant. Conversely, a top-down strategy that imposes high-level business targets without grounding in operational data realities is prone to optimistic overestimation and failure in execution [11]. The following table summarizes the quantitative impact of these failures.

Table 1: The Business Impact of Poor Forecasting and Validation

| Metric | Impact of Inaccuracy | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Sales & Marketing Costs | 26% increase [11] | Misaligned resource allocation |

| Sales Cycle Length | 18% longer [11] | Inefficient pipeline management |

| Team Turnover | 31% higher [11] | Missed targets and compensation issues |

| Digital Transformation Failure | ~70% failure rate [12] | Lack of strategic alignment and technical readiness |

Defining the Paradigms: Bottom-Up Technical vs. Top-Down Business

The Bottom-Up Technical Approach

This methodology builds projections and validates models from the ground level upward. It relies on detailed analysis of granular data, individual components, and technical specifications [11] [13].

- Process: Analyzes elemental data → applies technical rules and statistical checks → validates individual modules → aggregates into a full system-level model.

- Strengths: High technical precision, minimizes redundancy through data encapsulation, effective for testing specific components and debugging [13].

- Weaknesses: Can miss the bigger strategic picture, may solve technical problems that are not business-critical, and often lacks alignment with organizational objectives, leading to models that are correct but unused [11].

The Top-Down Business Approach

This approach starts with the macro view of business objectives and market realities, then cascades downward to define technical requirements and validation criteria [11] [13].

- Process: Defines business objectives → analyzes total addressable market and competitive landscape → allocates targets and requirements → delegates technical execution.

- Strengths: Ensures strategic alignment, provides big-picture context, efficient for long-term planning and new market entry where historical data is limited [11].

- Weaknesses: Potential for overestimation, can overlook granular technical constraints, and may lack input from front-line technical experts, leading to a "reality gap" [11].

A Framework for Integrated Model Validation

The dichotomy between top-down and bottom-up is a false one. The most resilient validation strategy leverages both in a continuous dialogue. This integrated framework ensures that technical validation serves business strategy, and business strategy is informed by technical reality.

Diagram 1: Integrated Validation Strategy. This diagram illustrates how top-down business strategy and bottom-up technical validation must converge to form a robust, integrated validation process.

The Role of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)

MIDD provides a concrete embodiment of this integrated approach in pharmaceutical R&D. It maximizes and connects data collected during non-clinical and clinical development to inform key decisions [14]. MIDD employs both top-down and bottom-up modeling techniques:

- Top-Down MIDD Approaches: Methods like Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) use highly curated clinical trial data to understand the competitive landscape and support trial design optimization from a strategic, market-oriented perspective [14].

- Bottom-Up MIDD Approaches: Mechanistic modeling such as Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) build from fundamental physiological, biochemical, and cellular principles to predict drug behavior, drug-drug interactions, and effects in unstudied populations [14].

Table 2: MIDD Approaches as Examples of Integrated Validation

| MIDD Approach | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Business & Technical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Top-Down | Comparator analysis, trial design optimization, Go/No-Go decisions [14] | Informs strategic portfolio decisions; provides external control arms. |

| Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) | Hybrid | Characterizes dose-response, subject variability, exposure-efficacy/safety [14] | Supports dose selection and regimen optimization for late-stage trials. |

| Physiologically-Based PK (PBPK) | Bottom-Up | Predicts drug-drug interactions, dosing in special populations [14] | De-risks clinical studies; supports regulatory waivers (e.g., for TQT studies). |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Bottom-Up | Target selection, combination therapy optimization, safety risk qualification [14] | Guides early R&D strategy for novel modalities and complex diseases. |

Experimental Protocols for Strategic Validation

Adopting a top-down business strategy for validation requires a shift in methodology. The following protocols provide a actionable roadmap.

Protocol 1: Define Business-Driven Validation Criteria

Objective: To establish model acceptance criteria based on strategic business objectives rather than technical metrics alone. Methodology:

- Elicit Business Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Engage commercial, regulatory, and clinical leadership to define the key decisions the model will inform (e.g., "Is this drug more effective than the standard of care?", "What is the target product profile?").

- Translate CQAs to Quantitative Targets: Convert strategic questions into measurable outcomes. For example, a business requirement for "competitive efficacy" translates into a model validation target that must demonstrate a pre-specified effect size and confidence interval against a virtual control arm generated via MBMA [14].

- Set Risk-Based Tolerances: Define acceptable levels of model uncertainty based on the decision's risk. A model informing a final Phase 3 dose will have stricter tolerances than one guiding an early exploratory analysis.

Protocol 2: Conduct a Middle-Out Alignment Workshop

Objective: To bridge the translation gap between top-down strategy and bottom-up technical execution. Methodology:

- Assemble a Cross-Functional Team: Include members from leadership (top-down), modelers and statisticians (bottom-up), and crucially, project managers and translational scientists (the "middle").

- Map Strategic Goals to Technical Dependencies: Use process mapping to visually connect high-level goals (e.g., "accelerate timeline by 6 months") with the specific data and model requirements needed to achieve them (e.g., "PBPK model to waive a dedicated DDI study") [14].

- Develop a Shared Validation Plan: Co-create a document that explicitly links each business objective with its corresponding validation activity, responsible party, and success metric. This ensures technical work is purposeful and business goals are feasible [15].

Protocol 3: Implement a Model Lifecycle Governance Framework

Objective: To ensure continuous validation aligned with evolving business strategy throughout the drug development lifecycle. Methodology:

- Establish a Governance Committee: Form a body with representatives from statistics, clinical development, regulatory affairs, and commercial to oversee model development and deployment.

- Define Trigger Points for Re-validation: Pre-specify business and technical events that mandate model re-assessment (e.g., new competitor data, significant protocol amendments, unexpected trial results).

- Maintain an Integrated Audit Trail: Document all model assumptions, data sources, changes, and decisions linked to the strategic context at the time. This is critical for regulatory submissions and post-hoc analysis of model performance [12] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Robust Validation

Beyond strategic frameworks, successful validation requires a suite of technical and data "reagents." The following table details key components for building a validated, business-aligned modeling and simulation ecosystem.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation Process |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration & Governance | Cloud-native data platforms (e.g., RudderStack), iPaaS, Master Data Management (MDM) [16] | Unifies disparate data sources (clinical, non-clinical, real-world) to create a single source of truth, enabling robust data lineage and quality assurance. |

| Modeling & Simulation Software | PBPK platforms (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp), QSP platforms, Statistical software (R, NONMEM, SAS) [14] | Provides the computational engine for developing, testing, and executing both bottom-up mechanistic and top-down population models. |

| Metadata & Lineage Management | Data catalogs, version control systems (e.g., Git) [16] [17] | Tracks the origin, transformation, and usage of data and models, ensuring reproducibility and transparency for regulatory audits. |

| Process Standardization Tools | Electronic Data Capture (EDC) systems, workflow automation platforms [18] | Reduces manual errors and variability in data flow, leading to cleaner data inputs for modeling and more reliable validation outcomes. |

Validation fails when it is treated as a purely technical, bottom-up activity, divorced from the strategic business context in which its outputs will be used. The consequences—wasted resources, prolonged development cycles, and failed regulatory submissions—are severe. The path forward requires a deliberate shift to a top-down, business-led validation strategy. By defining success through the lens of business objectives, fostering middle-out alignment between strategists and scientists, and leveraging the powerful tools of Model-Informed Drug Development, organizations can transform validation from a perfunctory check-box into a strategic asset that drives faster, more confident decision-making and delivers safer, more effective therapies to patients.

In modern drug development, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" has evolved from a technical warning to a critical business and regulatory risk factor. Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) has become an essential framework for advancing drug development and supporting regulatory decision-making, relying on quantitative predictions and data-driven insights to accelerate hypothesis testing and reduce costly late-stage failures [19]. The integrity of these models, however, is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the underlying data. Poor data quality directly compromises model validity, leading to flawed decisions that can derail development programs, incur substantial financial costs, and potentially endanger patient safety.

Within the context of statistical model validation, data quality serves as the foundation upon which all analytical credibility is built. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the direct relationship between data integrity and model output is no longer optional—it is a professional imperative. This technical guide examines the multifaceted consequences of poor data quality, provides structured methodologies for its assessment, and outlines a robust framework for implementing data quality controls within governed model risk management systems.

Defining and Quantifying Data Quality in a Regulatory Context

Core Dimensions of Data Quality

Data quality is a multidimensional concept. For drug development applications, several key dimensions must be actively managed and measured to ensure fitness for purpose [20]:

- Accuracy: The degree to which data correctly describes the real-world object or event it represents.

- Completeness: The extent to which all required data points are available and populated.

- Consistency: The uniformity of data across different datasets or systems, ensuring absence of contradictions.

- Timeliness: The availability of data to users when required, and its recency relative to the events it describes.

- Uniqueness: The assurance that no duplicate records exist for a single entity within a dataset.

Quantitative Metrics for Data Quality Assessment

Systematic measurement is prerequisite to improvement. The following table summarizes key data quality metrics that organizations should monitor continuously.

Table 1: Essential Data Quality Metrics for Drug Development

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Measurement Approach | Target Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Number of Empty Values [20] | Count of records with missing values in critical fields | >95% complete for critical fields |

| Accuracy | Data to Errors Ratio [20] | Number of known errors / Total number of data points | <0.5% error rate |

| Uniqueness | Duplicate Record Percentage [20] | Number of duplicate records / Total records | <0.1% duplication |

| Timeliness | Data Update Delays [20] | Time between data creation and system availability | <24 hours for clinical data |

| Integrity | Data Transformation Errors [20] | Number of failed ETL/ELT processes per batch | <1% failure rate |

| Business Impact | Email Bounce Rates (for patient recruitment) [20] | Bounced emails / Total emails sent | <5% bounce rate |

The Consequences of Poor Data Quality

Impact on Statistical Analysis and Decision-Making

Compromised data quality fundamentally undermines the analytical processes central to drug development. The consequences manifest in several critical areas:

- Misleading Correlation and Causation Inferences: Poor quality data can create spurious correlations or mask true causal relationships. The well-established statistical principle that "correlation does not imply causation" becomes particularly dangerous when based on flawed data, potentially leading research efforts down unproductive paths [21].

- Erosion of Statistical Power and Significance: Incomplete or inaccurate data effectively reduces sample size and introduces noise, diminishing a study's power to detect true treatment effects. This can result in Type II errors (false negatives), where potentially effective therapies are incorrectly abandoned [21].

- Compromised Model Validation: The 2025 validation landscape report highlights that data integrity remains a top-three challenge for validation teams [22]. Without high-quality data, model validation becomes a theoretical exercise rather than a substantive assessment of predictive accuracy.

Regulatory and Compliance Implications

The regulatory environment for drug development is increasingly data-intensive, with severe consequences for data quality failures.

- Audit Readiness Challenges: In 2025, audit readiness has surpassed compliance burden as the top challenge in validation, with 69% of teams citing automated audit trails as a critical benefit of digital systems [22]. Poor data quality directly undermines audit readiness by creating inconsistencies in data lineage and traceability.

- Model Risk Management Deficiencies: Financial institutions face similar challenges, where regulators emphasize model risk management (MRM) frameworks that are inherently dependent on data quality. Core regulatory compliance requires "strong model validation practices, comprehensive documentation standards, and well-defined governance structures" [23], all of which are compromised by poor data.

- Statistical Significance Misinterpretation in Regulatory Submissions: Regulators often employ statistical significance testing to evaluate lending patterns, where a 5% significance level is commonly used to identify patterns unlikely to occur by chance [24]. In drug development, analogous statistical thresholds used in regulatory submissions can be misinterpreted when data quality issues inflate variance or introduce bias.

Financial and Operational Costs

The financial impact of poor data quality is substantial and multifaceted. Gartner's Data Quality Market Survey indicates that the average annual financial cost of poor data reaches approximately $15 million per organization [25]. These costs accumulate through several mechanisms:

- Increased Storage Costs: Rising data storage costs without corresponding increases in data utilization often indicate accumulation of low-quality "dark data" that provides no business value [20].

- Extended Development Timelines: The "data time-to-value" metric measures how quickly teams can convert data into business value. Poor data quality extends this timeline through required manual cleanup and rework [20].

- Regulatory Penalties: While difficult to quantify precisely, potential regulatory penalties for compliance failures represent a significant financial risk, particularly in highly regulated sectors like drug development.

Experimental Protocols for Data Quality Assessment

Protocol for a Comprehensive Data Quality Audit

Objective: To systematically assess data quality across all critical dimensions within a specific dataset (e.g., clinical trial data, pharmacokinetic data).

Materials and Methodology:

- Data Profiling Tools: Use automated data profiling software (e.g., Talend, Informatica, custom Python scripts) to analyze dataset structure and content.

- Statistical Analysis Software: R, SAS, or Python with pandas for statistical assessment.

- Domain Experts: Clinical researchers, data managers, and biostatisticians for contextual interpretation.

Procedure:

- Define Scope and Critical Data Elements: Identify specific data elements critical to research objectives and regulatory compliance.

- Execute Completeness Assessment: For each critical data element, calculate: Completeness Percentage = (1 - [Number of empty values / Total records]) × 100 [20].

- Perform Accuracy Validation: For a statistically significant sample (or 100% for small datasets), verify data against source documents or through double-entry verification.

- Conduct Consistency Analysis: Cross-reference related data elements across systems to identify contradictory values (e.g., patient birth date versus enrollment date).

- Implement Uniqueness Testing: Apply deterministic or probabilistic matching algorithms to identify duplicate records.

- Calculate Composite Quality Score: Weight and aggregate dimension-specific scores based on business criticality.

Quality Control: Independent verification of findings by a second analyst; documentation of all methodology and results for audit trail.

Protocol for Data Transformation Error Monitoring

Objective: To identify and quantify data quality issues introduced through data integration and transformation processes.

Materials and Methodology:

- ETL/ELT Monitoring Tools: Automated workflow monitoring (e.g., Apache Airflow, Dagster) with custom quality checks.

- Data Validation Framework: Great Expectations or similar data testing frameworks.

Procedure:

Implement Pre-Load Validation Checks:

- Schema validation against defined data models

- Data type verification for all fields

- Range checks for numerical values (e.g., physiological measurements)

- Format validation for coded values (e.g., medical terminology)

Monitor Transformation Failures:

- Log all transformation job failures

- Categorize failures by type (e.g., null handling, type conversion, business rule violation)

- Calculate: Transformation Failure Rate = [Failed transformations / Total transformations] × 100 [20]

Conduct Post-Load Reconciliation:

- Record counts between source and target systems

- Aggregated value comparisons for key metrics

- Data lineage verification for critical fields

Figure 1: Data Quality Assessment Workflow

A Framework for Data Quality in Model Risk Management

Integrating Data Quality Controls into Model Validation

For researchers and scientists engaged in model validation, data quality must be formally integrated into the model risk management lifecycle. The following framework provides a structured approach:

- Pre-Validation Data Assessment: Before model validation begins, conduct a formal data quality assessment using the protocols outlined in Section 4. Document data quality metrics as part of the model validation package.

- Risk-Based Data Tiering: Align data quality controls with model risk tiering. High-risk models (e.g., those supporting regulatory submissions or critical patient safety decisions) require more stringent data quality standards and validation [23].

- Continuous Monitoring Implementation: Move beyond point-in-time assessments to continuous data quality monitoring. Implement automated checks that track key data quality metrics throughout the model lifecycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Data Quality Assurance

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Quality Management

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in Data Quality Assurance |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Profiling | Data Profiling Software (e.g., Talend, Informatica) | Automatically analyzes data structure, content, and quality issues across large datasets. |

| Validation Frameworks | Great Expectations, Deequ | Creates automated test suites to validate data against defined quality rules. |

| Master Data Management | MDM Solutions (e.g., Informatica MDM, Reltio) | Creates single source of truth for critical entities (e.g., patients, compounds) to ensure consistency. |

| Data Lineage Tools | Collibra, Alation | Tracks data origin and transformations, critical for audit readiness and impact analysis. |

| Quality Monitoring | Custom Dashboards (e.g., Tableau, Power BI) | Visualizes key data quality metrics for continuous monitoring and alerting. |

Implementing a Culture of Data Quality

Technology alone cannot ensure data quality. Organizations must foster a culture where data quality is recognized as a shared responsibility.

- Clear Data Ownership: Assign named stewards accountable for critical data assets [25]. These stewards answer quality questions, investigate issues, and enforce policies.

- Data Literacy Training: Invest in training programs to improve data literacy across research and development teams, ensuring staff can accurately interpret data and identify potential quality issues.

- Governance Integration: Embed data quality into existing governance workflows, including protocol review, statistical analysis plan development, and study monitoring.

Figure 2: Data Quality Framework for Model Input Assurance

In the context of drug development, where decisions have significant scientific, financial, and patient-care implications, poor data quality represents an unacceptable risk. The convergence of increasing model complexity, regulatory scrutiny, and data volume demands a disciplined approach to data quality management. By implementing the structured assessment protocols, monitoring frameworks, and governance models outlined in this guide, research organizations can transform data quality from a reactive compliance activity into a strategic asset that enhances decision-making, strengthens regulatory submissions, and ultimately accelerates the delivery of new therapies to patients.

The evolving regulatory landscape in 2025, with its emphasis on audit readiness and real-world model performance [23] [22], makes data quality more critical than ever. For the research scientist, statistical modeler, or development professional, expertise in data quality principles and practices is no longer a specialization—it is an essential component of professional competency in model-informed drug development.

Model governance is the comprehensive, end-to-end process by which organizations establish, implement, and maintain controls over the use of statistical and machine learning models [26]. In the high-stakes field of drug development, where models inform critical decisions from clinical trial design to market forecasting, a robust governance framework is not merely a best practice but a foundational component of operational integrity and regulatory compliance [26] [27]. The purpose of such a framework is to ensure that all models—whether traditional statistical models or advanced machine learning algorithms—operate as intended, remain compliant with evolving regulations, and deliver trustworthy results throughout their lifespan [26].

The relevance of model governance has expanded dramatically with the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). According to industry analysis, nearly 70% of leading pharmaceutical companies are now integrating AI with their existing models to streamline operations [27]. This integration, while beneficial, introduces new complexities and risks that must be managed through structured oversight. Effective governance directly supports transparency, accountability, and repeatability across the entire model lifecycle, making it a critical capability for organizations aiming to leverage AI responsibly [26].

The Model Lifecycle: A Foundation for Governance

A well-defined model lifecycle provides the structural backbone for effective governance. It ensures that every model is systematically developed, validated, deployed, and monitored. A typical model lifecycle consists of seven key stages, which can be mapped to a logical workflow [28].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential stages and key decision gates of the model lifecycle:

Figure 1: Model Lifecycle Workflow

Stage Descriptions and Key Activities

Stage 1: Model Proposal The lifecycle begins with a formal proposal that outlines the business case, intended use, and potential risks of the new model. The first line of defence (business and model developers) identifies business requirements, while the second line (risk and compliance) assesses potential risks [28].

Stage 2: Model Development Data scientists and model developers gather, clean, and format data before experimenting with different modeling approaches. The final model is selected based on performance, and the methodology for training or calibration is defined and implemented [28].

Stage 3: Pre-Validation The development team conducts initial testing and documents the results rigorously. This internal quality check ensures the model is ready for independent scrutiny [28].

Stage 4: Independent Review Model validators, independent of the development team, analyze all submitted documentation and test results. This crucial gate determines whether the model progresses to approval or requires additional work [29] [28].

Stage 5: Approval Stakeholders from relevant functions (e.g., business, compliance, IT) provide formal approvals, acknowledging the model's fitness for purpose and their respective responsibilities [28].

Stage 6: Implementation A technical team implements the validated and approved model into production systems, ensuring it integrates correctly with existing infrastructure and processes [28].

Stage 7: Validation & Reporting Following implementation, the validation team performs a final review to confirm the production model works as expected. Once in production, ongoing monitoring begins—typically a first-line responsibility [28].

This lifecycle is not linear but cyclical; whenever modifications are necessary for a production model, it re-enters the process at the development stage [28].

Roles, Responsibilities, and the Three Lines of Defence

A robust governance framework clearly delineates roles and responsibilities through the "Three Lines of Defence" model, which ensures proper oversight and segregation of duties [28].

The Three Lines of Defence

Table 1: The Three Lines of Defence in Model Governance

| Line of Defence | Key Functions | Primary Roles | Accountability |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Line (Model Development & Business Use) | Model development, testing, documentation, ongoing monitoring, and operational management [28]. | Model Developers, Model Owners, Model Users [28]. | Daily operation and performance of models; initial risk identification and mitigation. |

| Second Line (Oversight & Validation) | Independent model validation, governance framework design, policy development, and risk oversight [26] [28]. | Model Validation Team, Model Governance Committee, Risk Officers [26] [28]. | Ensuring independent, effective validation; defining governance policies; challenging first-line activities. |

| Third Line (Independent Assurance) | Independent auditing of the overall governance framework and compliance with internal policies and external regulations [28]. | Internal Audit [28]. | Providing objective assurance to the board and senior management on the effectiveness of governance and risk management. |

The relationship between these lines of defence is visualized below:

Figure 2: Three Lines of Defence Model

Critical Governance Roles

- Model Owners: Typically business leaders who are ultimately accountable for the model's performance and business outcomes [26] [28].

- Model Developers: Data scientists and statisticians responsible for the technical construction, documentation, and initial testing of the model [26] [28].

- Model Validators: Independent experts who assess conceptual soundness, data quality, and ongoing performance [29] [30].

- Governance Committee: A cross-functional body that approves models, oversees the inventory, and ensures compliance with the governance framework [26].

Model Validation: Core of the Governance Framework

Model validation is not a single event but a continuous process that verifies models are performing as intended and is a core element of model risk management (MRM) [30]. It is fundamentally different from model evaluation: while evaluation is performed by the model developer to measure performance, validation is conducted by an independent validator to ensure the model is conceptually sound and aligns with business use [29].

Key Validation Techniques and Protocols

Independent Review and Conceptual Soundness The independent validation team must review documentation, code, and the rationale behind the chosen methodology and variables, searching for theoretical errors [29]. This includes testing key model assumptions and controls. For example, in a drug development forecasting model, this might involve challenging assumptions about patient recruitment rates or drug efficacy thresholds [29] [27].

Back-Testing and Historical Analysis Validation requires testing the model against historical data to assess its ability to accurately predict past outcomes [26] [30]. For financial models in drug development (e.g., forecasting ROI), this involves comparing the model's predictions to actual historical market data. Regulatory guidance like the ECB's requires back-testing at least annually and including back-testing at single transaction levels [30].

In-Sample vs. Out-of-Sample Validation

- In-sample validation assesses how well the model fits the data it was trained on (goodness of fit), often through residual analysis [31]. This is crucial for understanding relationships between variables and their effect sizes.

- Out-of-sample validation tests the model's predictive performance on new, unseen data, typically through cross-validation techniques [31]. This helps guard against overfitting, where a model is too specifically tuned to one dataset and fails to generalize [31].

Performance Benchmarking and Thresholds Establishing clear performance thresholds (e.g., minimum accuracy, precision, recall) is essential. Pre-deployment validation should confirm these metrics are met, both overall and across critical data slices to ensure the model performs well for all relevant patient subgroups or drug categories [32].

Table 2: Core Model Validation Techniques and Applications

| Technique | Methodology | Primary Purpose | Common Use Cases in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hold-Out Validation | Split data into training/test sets (e.g., 80/20) [33]. | Estimate performance on unseen data. | Initial forecasting models with sufficient historical data. |

| Cross-Validation | Partition data into k folds; train on k-1 folds, test on the remaining fold; rotate [33]. | Robust performance estimation with limited data. | Clinical outcome prediction models with limited patient datasets. |

| Residual Analysis | Analyze differences between predicted and actual values [31]. | Check model assumptions and identify systematic errors. | Regression models for drug dosage response curves. |

| Benchmark Comparison | Compare model performance against a simple baseline or previous model version [32]. | Ensure model adds value over simpler approaches. | Validating new patient risk stratification models against existing standards. |

Advanced Validation: From Traditional Models to AI

As drug development increasingly incorporates AI and machine learning, validation frameworks must evolve to address new challenges [26] [32].

The Five Stages of Machine Learning Validation

For AI/ML models, validation extends beyond traditional techniques to encompass a broader, continuous process [32]:

- ML Data Validations: Assess dataset quality for model training, including data engineering checks (null values, known ranges) and ML-specific validations (data distribution, potential bias) [32].

- Training Validations: Involve validating models trained with different data splits or parameters, including hyperparameter optimization and feature selection validation [32].

- Pre-Deployment Validations: Final quality checks before deployment, including performance threshold checks, robustness testing on edge cases, and explainability assessments [32].

- Post-Deployment Validations (Monitoring): Continuous checks in production, including rolling performance calculations, outlier detection, and drift detection to identify model deterioration [32].

- Governance & Compliance Validations: Ensure models meet government and organizational requirements for fairness, transparency, and ethics [32].

Addressing AI-Specific Risks

ML models introduce unique risks that validation must address:

- Algorithmic Bias: Models must be validated for unfair bias against protected classes, which is particularly critical in clinical trial participant selection [26].

- Explainability: Many stakeholders, including regulators, require explainable models. Balancing performance with explainability remains a persistent challenge [26].

- Model Drift: Even a small change in the environment can dramatically impact predictions, necessitating continuous monitoring for concept drift and data drift [32].

Implementation and Regulatory Compliance

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Table 3: Essential Components for a Model Governance Framework

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Model Inventory | Centralized tracking of all models in use, including purpose, ownership, and status [26]. | Database with key model metadata; dashboard for management reporting. |

| Documentation Standards | Capture rationale, methodology, assumptions, and data sources for transparency [26]. | Standardized templates for model development and validation reports. |

| Validation Policy | Group-wide policy outlining validation standards, frequency, and roles [30]. | Document approved by governance committee; integrated into risk management framework. |

| Monitoring Tools | Automated systems to track model performance and detect degradation [26]. | Dashboards for model metrics; automated alerts for performance drops or drift. |

| Governance Committee | Cross-functional body responsible for model approval and oversight [26]. | Charter defining membership, meeting frequency, and decision rights. |

Regulatory Landscape

Model governance in drug development operates within a complex regulatory environment. While no single regulation governs all aspects, several frameworks are relevant:

- SR 11-7 (United States): Sets the standard for model risk management in banking, requiring full model inventory and enterprise-wide governance practices [26]. While focused on banking, its principles are often adopted by other regulated industries.

- EU AI Act (European Union): Takes a risk-based approach to AI regulation, classifying certain medical AI applications as high-risk and subject to stricter requirements [26].

- GDPR (European Union): Impacts models processing personal data of EU citizens, requiring fairness, transparency, and accountability, which indirectly affects ML model governance, especially for explainability and data quality [26].

Supervisory expectations continue to evolve rapidly. Regulatory bodies increasingly emphasize the independence of model validation functions, robust back-testing frameworks, and the timely follow-up of validation findings [30].

Establishing robust model governance with clear roles, accountability, and a well-defined lifecycle is not an administrative burden but a strategic imperative for drug development organizations. As models become more embedded in core business processes—from clinical decision support to market forecasting—the consequences of model failure grow more severe [26]. A structured governance framework, supported by independent validation and continuous monitoring, enables organizations to leverage the power of advanced analytics while managing associated risks. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing this disciplined approach is essential for maintaining regulatory compliance, building trust with stakeholders, and ultimately ensuring that models serve as reliable tools in the mission to bring innovative therapies to patients.

A Methodological Toolkit: Choosing and Applying Validation Techniques

In the data-driven landscape of modern research and development, particularly in high-stakes fields like drug development, the validity of statistical and machine learning models is paramount. Model validation transcends mere technical verification; it ensures that predictive insights are reliable, reproducible, and fit-for-purpose, ultimately safeguarding downstream decisions and investments. A structured, strategic approach to validation is no longer a luxury but a necessity.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate model validation strategies, anchored by a decision-tree methodology. This approach systematically navigates the complex interplay of data characteristics, model objectives, and operational constraints. Framed within the broader context of statistical model validation, this whitepaper equips researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the principles and tools to implement rigorous, defensible validation protocols tailored to their specific challenges.

The Critical Role of Model Validation

Model validation is the cornerstone of credible model-informed decision making. It provides critical evidence that a model is not only mathematically sound but also appropriate for its intended context of use (COU). In sectors like pharmaceuticals, where models support regulatory submissions and clinical development, a fit-for-purpose validation strategy is essential [19].

A robust validation strategy mitigates the risk of model failure by thoroughly assessing a model's predictive performance, stability, and generalizability to unseen data. Without such rigor, organizations face the perils of inaccurate forecasts, misguided resource allocation, and ultimately, a loss of confidence in model-based insights. The following sections deconstruct the key factors that must guide the development of any validation strategy.

A Decision-Tree Framework for Validation Strategy Selection

The decision tree below provides a visual roadmap for selecting an appropriate validation strategy based on the nature of your data, the goal of the validation, and practical constraints. This structured approach simplifies a complex decision-making process into a logical, actionable pathway.

Diagram 1: Decision tree for model validation strategy selection. I.I.D. = Independent and Identically Distributed, CV = Cross-Validation. Adapted from [34].

Decision Tree Logic and Key Branch Points

The decision tree is structured around a series of critical questions about the data and project goals. The path taken determines the most suitable validation technique(s).

Data Structure: The first and most crucial branch concerns the fundamental structure of the dataset.

- Time-Ordered Data: For data with a temporal component, such as time series, standard random shuffling would destroy meaningful patterns. Specialized methods like Time Series Split are required, as they respect the temporal order of observations [34].

- Non-I.I.D. Data: If data instances are not independent and identically distributed (e.g., multiple measurements from the same patient, students nested within schools), standard validation methods can lead to optimistic bias and data leakage. Techniques like Grouped K-Fold or Clustered Validation, where all data from a single group appears exclusively in either the training or test set, are necessary to obtain realistic performance estimates [34].

- I.I.D. Data: For data that meets the i.i.d. assumption, the tree proceeds to evaluate the specific goals and characteristics of the modeling task.

Primary Goal and Data Characteristics: Within the i.i.d. data path, the choice of method is refined based on the project's priorities.

- Quick Baseline: For large datasets where a simple, computationally cheap baseline is sufficient, a Train-Test Split is a common starting point [34].

- General-Purpose Generalization: K-Fold Cross-Validation is a robust and widely recommended default for obtaining a reliable estimate of a model's ability to generalize to new data [34].

- Imbalanced Classification: In scenarios like fraud detection or medical diagnosis where one class is rare, Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation ensures that each fold preserves the percentage of samples for each class, leading to a more representative performance assessment [34].

- Reducing Variance: In high-stakes applications like clinical trials, the variance of the performance estimate itself must be minimized. Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation, which runs K-Fold CV multiple times with different random splits, provides a more stable estimate at a higher computational cost [34].

- Small Datasets and Bias Reduction: With very small datasets, the choice is between reducing bias or estimating uncertainty. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) is the preferred method for minimizing bias, as it uses nearly all data for training in each iteration. Alternatively, Bootstrapping (sampling with replacement) is a valid strategy for estimating the uncertainty of performance metrics, useful for constructing confidence intervals [34].

Quantitative Comparison of Core Validation Strategies

The table below summarizes the key attributes, strengths, and weaknesses of the core validation strategies outlined in the decision tree.

Table 1: Summary of Core Model Validation Strategies for I.I.D. Data

| Validation Method | Key Characteristics | Best-Suited Scenarios | Computational Cost | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train-Test Split | Single random partition into training and hold-out sets. | Large datasets, quick baseline evaluation, initial prototyping. | $ (Low) | Simple, fast, intuitive. | High variance estimate dependent on a single split. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation (CV) | Data partitioned into K folds; each fold serves as test set once. | General-purpose model evaluation, estimating generalization error. | $$ (Moderate) | Reduces variance of estimate compared to single split; makes efficient use of data. | Computationally more expensive than train-test split. |

| Stratified K-Fold CV | Preserves the class distribution in each fold. | Imbalanced classification tasks. | $$ (Moderate) | Provides more reliable performance estimate for imbalanced data. | Primarily for classification; requires class labels. |

| Repeated K-Fold CV | Runs K-Fold CV multiple times with different random seeds. | Risk-sensitive applications, reducing variance of performance estimate. | $$$ (High) | More reliable and stable performance estimate. | Computationally intensive. |

| Leave-One-Out CV (LOOCV) | K = N; each single sample is the test set. | Very small datasets where reducing bias is critical. | $$$ (High) | Low bias, uses maximum data for training. | High computational cost and variance of the estimator. |

| Bootstrapping | Creates multiple datasets by sampling with replacement. | Estimating uncertainty, constructing confidence intervals. | $$ (Moderate) | Good for quantifying uncertainty of metrics. | Can yield overly optimistic estimates; not a pure measure of generalization. |

Advanced Applications and Specialized Protocols

Validation in Pharmaceutical Development and MIDD

In Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), validation is a continuous, lifecycle endeavor aligned with the "fit-for-purpose" principle [19]. A model's validation strategy must be proportionate to its Context of Use (COU), which can range from internal decision-making to regulatory submission.

Table 2: Key "Fit-for-Purpose" Modeling Tools and Their Research Contexts in Drug Development

| Research Reagent Solution / Tool | Function in Development & Validation | Primary Context of Use (COU) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Integrates systems biology and pharmacology for mechanism-based prediction of drug effects and side effects. | Target identification, lead optimization, clinical trial design. |

| Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | Mechanistic modeling to predict pharmacokinetics based on physiology and drug properties. | Predicting drug-drug interactions, formulation selection, supporting generic drug development. |

| Population PK/PD and Exposure-Response (ER) | Explains variability in drug exposure and its relationship to efficacy and safety outcomes in a population. | Dose justification, trial design optimization, label recommendations. |

| Bayesian Inference | Integrates prior knowledge with observed data for improved predictions and probabilistic decision-making. | Adaptive trial designs, leveraging historical data, dynamic dose finding. |

| Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning | Analyzes large-scale biological, chemical, and clinical datasets for prediction and optimization. | Target prediction, compound prioritization, ADMET property estimation, patient stratification. |

A robust MIDD validation protocol often involves:

- Model Verification: Ensuring the computational implementation accurately reflects the underlying mathematical model.

- Model Calibration: Adjusting model parameters to fit observed data within a defined range.

- Model Evaluation: Assessing predictive performance against a dedicated validation dataset not used in model development. This includes goodness-of-fit plots, residual analysis, and predictive checks [19].

- Model Qualification: For a given COU, demonstrating the model's suitability through external data, sensitivity analysis, and sometimes clinical trial simulation to prospectively test its predictive power [19].

Experimental Protocol for LLM Evaluation in RAG Pipelines

For modern AI applications like Large Language Models (LLMs), particularly in Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, specialized evaluation protocols are essential. The following workflow, based on the "LLM-as-a-judge" pattern, assesses the faithfulness of generated answers [35].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for LLM faithfulness evaluation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Preparation: The inputs to the evaluator are the full text of the LLM's generated

responseand thecontext(e.g., retrieved documents) used to generate it [35]. - Claim Decomposition: The

responseis programmatically broken down into a list of discrete, factualclaims. For example, the response "The drug X, which was approved in 2020, works by inhibiting protein Y" would be decomposed into two claims: "Drug X was approved in 2020" and "Drug X works by inhibiting protein Y" [35]. - Claim Verification (LLM-as-a-Judge): Each

claimis presented to a secondary, typically more powerful, "judge" LLM (e.g., GPT-4) via a carefully designed prompt template. The prompt instructs the judge to determine if the claim can be logically inferred from the providedcontext, outputting a binaryYes/Nodecision [35]. - Score Calculation: The final faithfulness score is calculated as the fraction of total claims that were supported by the context:

Faithfulness Score = (Number of Supported Claims) / (Total Number of Claims). A score of 1.0 indicates all claims are grounded in the context, while a lower score indicates potential hallucination [35].

This protocol, supported by open-source frameworks like Ragas and DeepEval, provides a quantitative and scalable way to monitor a critical aspect of LLM application performance [36] [35].

Selecting the correct model validation strategy is a foundational element of rigorous research and development. The decision-tree approach provides a systematic and logical framework to navigate this complex choice, ensuring the selected method is aligned with the data's structure, the project's goals, and the model's intended context of use. As modeling techniques evolve—from traditional statistical models in drug development to modern LLMs—the principle remains constant: validation must be proactive, comprehensive, and fit-for-purpose.

Moving beyond a one-size-fits-all mindset to a strategic, tailored approach to validation builds confidence in predictive models, mitigates project risk, and underpins the credibility of data-driven decisions. By adopting the structured methodology and specialized protocols outlined in this guide, professionals can ensure their models are not just technically sound, but truly reliable assets in the scientific and clinical toolkit.

Within the framework of statistical model validation, hold-out methods stand as a fundamental class of techniques for assessing a model's predictive performance on unseen data. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of two core hold-out protocols: the simple train-test split and the more comprehensive train-validation-test split. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this whitepaper details the conceptual foundations, implementation methodologies, and practical considerations for applying these techniques to ensure models generalize effectively beyond their training data, thereby supporting robust and reliable scientific conclusions.

In predictive analytics, a central challenge is determining whether a model has learned underlying patterns that generalize to new data or has simply memorized the training dataset [37]. Hold-out validation addresses this by partitioning the available data into distinct subsets, simulating the ultimate test of a model: its performance on future, unseen observations [38] [39].

The core principle is that a model fit on one subset of data (the training set) is evaluated on a separate, held-back subset (the test or validation set). This provides an unbiased estimate of the model's generalization error—the error expected on new data [40] [39]. These methods are particularly vital in high-stakes fields like drug development, where model predictions can influence critical decisions. They help avoid the pitfalls of overfitting, where a model performs well on its training data but fails on new data, and underfitting, where a model is too simplistic to capture the underlying trends [38].

Core Concepts and Terminology

- Training Set: The subset of data used to fit the model. The model learns the relationships between input variables and the target output from this data [39].

- Test Set (or Hold-out Set): A separate subset of data, withheld from the training process, used to provide an unbiased evaluation of the final model's performance [39]. It is crucial that the test set remains completely unseen until the very end of the model development cycle.

- Validation Set: A second hold-out set used during the model development phase for hyperparameter tuning and model selection. Using the test set for this purpose would lead to information "leaking" from the test set into the model, making the test set performance an optimistic estimate [38] [39].

- Generalization: The ability of a model to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data. This is the primary objective of model building and the key metric that hold-out methods aim to estimate [37].