Statistical Validation Techniques for Predictive Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the statistical validation of predictive models in biomedical and clinical research.

Statistical Validation Techniques for Predictive Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the statistical validation of predictive models in biomedical and clinical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of model evaluation, key methodological approaches for assessing performance, advanced techniques for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous strategies for external validation and model comparison. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging methodologies, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build reliable, clinically applicable predictive models that can withstand the complexities of real-world data and support critical decision-making in healthcare.

Core Principles and the Critical Importance of Model Validation

In the field of predictive modeling, particularly within medical and pharmaceutical research, model validation is the critical process of evaluating a model's performance to ensure its predictions are accurate, reliable, and trustworthy for supporting clinical decisions [1] [2]. Validation provides essential safeguards against the risks of deploying models that may fail when applied to new patient populations or in different clinical settings. Without rigorous validation, prediction models may appear effective in the development data but prove misleading or harmful in real-world applications [3].

The core distinction in validation approaches lies between internal and external validation. Internal validation assesses model performance on data from the same source population as the development data, primarily addressing overfitting—where a model learns patterns specific to the development data that do not generalize. External validation evaluates performance on data collected from different populations, locations, or time periods, assessing the model's transportability and generalizability beyond its original development context [1]. Both forms of validation are essential components of a comprehensive validation strategy, with external validation being particularly crucial for verifying that a model can safely support decisions in diverse clinical environments [3] [1].

Internal Validation: Concepts and Methodologies

Core Principle and Purpose

Internal validation aims to estimate how well a predictive model would perform when applied to new samples from the same underlying population as the development data [2]. It focuses on quantifying and correcting for overfitting, which occurs when a model learns random noise or idiosyncratic patterns in the development dataset rather than true underlying relationships. This over-optimism, known as optimism bias, means the model's performance in the development data will be better than its performance in new data from the same population [3]. Internal validation techniques provide corrected estimates of model performance to address this bias.

Key Methodological Approaches

Table 1: Common Internal Validation Techniques

| Technique | Description | Key Advantages | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holdout Validation | Dataset randomly split into training and testing sets [4] [5] | Simple to implement; computationally efficient | Large datasets with ample samples |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Data divided into k subsets; each subset serves once as validation while others train [4] [5] | More robust performance estimate; uses data efficiently | Medium-sized datasets; model comparison |

| Bootstrap Validation | Multiple random samples with replacement from original data; model evaluated on unsampled cases [3] | Provides optimism-corrected estimates; does not require large holdout samples | Small to medium datasets; optimal for clinical models [3] |

| Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation | Special case of k-fold where k equals number of observations [5] | Minimizes bias; uses nearly all data for training | Small datasets where every observation counts |

Application in Medical Research

In clinical prediction model development, internal validation is considered a mandatory step. Research indicates that models developed from small datasets are particularly vulnerable to overfitting, making internal validation essential [3]. For example, in a study developing a nomogram to predict overall survival in cervical cancer patients, the researchers randomly split their 13,592 patient records from the SEER database into a training cohort (n=9,514) and an internal validation cohort (n=4,078) using a 70:30 ratio [6]. This internal validation approach allowed them to obtain optimism-corrected performance estimates, with the model achieving a concordance index (C-index) of 0.885 in the internal validation cohort, similar to the training performance [6].

External Validation: Concepts and Methodologies

Core Principle and Purpose

External validation tests whether a predictive model developed in one setting performs adequately in different populations, locations, or time periods [1]. Where internal validation addresses reproducibility, external validation focuses on transportability—the model's ability to maintain performance when applied to new environments with potentially different patient characteristics, measurement procedures, or clinical practices [1]. A model succeeding only in internal validation but failing in external validation may be clinically dangerous if implemented broadly.

Key Methodological Approaches

Table 2: Types of External Validation

| Validation Type | Description | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Validation | Validation on data from different locations or centers [1] | Tests cross-center applicability; identifies geographic variations | May reflect different healthcare systems rather than model flaws |

| Temporal Validation | Validation on data from the same location but different time period [3] | Assesses temporal stability; detects model decay over time | Does not test spatial generalizability |

| Domain Validation | Validation on data with different inclusion criteria or patient populations [1] | Tests robustness to population shifts; broadest generalizability test | Most challenging to pass; may require model recalibration |

Critical Challenges in External Validation

Three fundamental reasons explain why models often perform worse during external validation [1]:

Patient populations vary: Differences in demographics, risk factors, disease severity, and healthcare systems between development and validation settings affect model performance. These variations can impact both discrimination (separation between risk groups) and calibration (accuracy of absolute risk estimates) [1].

Measurement procedures vary: Equipment from different manufacturers, subjective assessments, clinical practice patterns, and measurement timing can create heterogeneity that diminishes model performance [1].

Populations and measurements change over time: Natural temporal shifts in patient characteristics, disease management, and measurement technologies can degrade model performance, a phenomenon known as "model drift" [1].

Application in Medical Research

The cervical cancer prediction study exemplifies rigorous external validation, where researchers tested their nomogram on 318 patients from Yangming Hospital Affiliated to Ningbo University—a completely different institution from the SEER database used for development [6]. The model maintained strong performance with a C-index of 0.872, demonstrating successful geographic transportability [6]. Similarly, in HIV research, a study developing a random survival forest model to predict survival following antiretroviral therapy initiation conducted external validation using data from a different city [7]. While the model showed excellent internal performance (C-index: 0.896), external validation revealed a substantial decrease (C-index: 0.756), highlighting how model performance can vary across settings and the critical importance of external testing [7].

Comparative Analysis: Performance Across Validation Contexts

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Validation Types in Medical Studies

| Study & Condition | Model Type | Internal Performance (C-index/AUC) | External Performance (C-index/AUC) | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer Survival [6] | Cox Nomogram | C-index: 0.885 (95% CI: 0.873-0.897) | C-index: 0.872 (95% CI: 0.829-0.915) | -0.013 |

| HIV Survival Post-HAART [7] | Random Survival Forest | C-index: 0.896 (95% CI: 0.885-0.906) | C-index: 0.756 (95% CI: 0.730-0.782) | -0.140 |

| HIV Treatment Interruption Prediction [8] | Various ML Models | Mean AUC: 0.668 (SD=0.066) | Rarely performed [8] | Not assessed |

Interpretation of Performance Discrepancies

The performance differences between internal and external validation reveal important characteristics about model robustness and generalizability. The cervical cancer nomogram demonstrated remarkable consistency between internal and external validation, suggesting the identified prognostic factors (age, tumor grade, stage, size, lymph node metastasis, and lymph vascular space invasion) maintain consistent relationships across healthcare settings [6]. In contrast, the substantial performance drop in the HIV survival model during external validation indicates higher sensitivity to differences between development and validation settings, potentially due to variations in patient populations, measurement procedures, or clinical practices [7].

Systematic reviews highlight that performance degradation during external validation is common. One analysis of 104 cardiovascular prediction models found median C-statistics decreased from 0.76 in development data to 0.64 at external validation [1]. This underscores why external validation is indispensable for determining a model's true clinical utility.

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Validation

Recommended Validation Workflow

A comprehensive validation strategy should incorporate both internal and external validation components [3]:

Internal validation using bootstrapping: For the development dataset, use bootstrap resampling (with 1000 or more replicates) to obtain optimism-corrected performance estimates [3]. This approach is preferred over simple data splitting, particularly for small to medium-sized datasets, as it uses the full dataset for development while providing robust overfitting corrections.

Internal-external cross-validation: When multiple centers or studies are available, use a leave-one-center-out approach where the model is developed on all but one center and validated on the left-out center, repeating for all centers [3]. This provides preliminary evidence of transportability while using all available data.

External validation in fully independent data: Seek validation in completely independent datasets from different locations, preferably collected at different times and representing the intended use populations [1].

Critical Performance Metrics

Both internal and external validation should assess multiple performance dimensions:

- Discrimination: Ability to separate high-risk and low-risk patients, measured by C-index (survival models) or AUC (classification models) [6] [7]

- Calibration: Agreement between predicted and observed event rates, assessed via calibration plots or tests [6] [1]

- Clinical utility: Net benefit of using the model for clinical decisions, evaluated through decision curve analysis [6]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Researcher's Toolkit for Predictive Model Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Validation | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R software with specific packages | Implementation of validation techniques and performance metrics | R version 4.3.2 used for cervical cancer nomogram development [6] |

| Validation Techniques | Bootstrap resampling, k-fold cross-validation | Internal validation and optimism correction | Bootstrapping with 1000 replicates recommended for internal validation [3] |

| Performance Metrics | C-index, AUC, calibration plots, Brier score | Quantifying discrimination, calibration, overall performance | C-index reported in cervical cancer (0.872-0.885) and HIV (0.756-0.896) studies [6] [7] |

| Data Splitting Methods | Random sampling, stratified sampling, temporal splitting | Creating training/validation splits | 70:30 random split used in cervical cancer study [6] |

| Reporting Guidelines | TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) | Ensuring comprehensive reporting of validation results | TRIPOD guidelines followed in HIV prediction study [7] |

Internal and external validation serve complementary but distinct roles in establishing the credibility of predictive models. Internal validation, through techniques such as bootstrapping and cross-validation, provides essential safeguards against overfitting and generates optimism-corrected performance estimates [3]. External validation, including geographic, temporal, and fully independent validation, tests the model's transportability to new settings and populations [1]. The empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that models frequently exhibit degraded performance during external validation, underscoring why both validation types are indispensable in the model development lifecycle [6] [7] [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, a comprehensive validation strategy should progress from rigorous internal validation to multiple external validations across diverse settings. This systematic approach ensures that predictive models deployed in clinical practice are both statistically sound and clinically useful across the varied contexts in which they will be applied.

The statistical validation of predictive models is a cornerstone of reliable research, particularly in fields like drug development and healthcare, where model predictions can directly impact clinical decisions and patient outcomes. A model's utility is not determined solely by its algorithmic sophistication but by its rigorously demonstrated performance on new, unseen data. This evaluation process moves beyond simple metrics to provide a holistic view of how a model will behave in real-world settings.

The TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis) checklist was developed to improve the reliability and value of clinical predictive model reporting, promoting transparency and methodological rigor [9]. Independent validation is crucial because a model's performance on its development data is often overly optimistic due to overfitting, where the model learns not only the underlying data patterns but also the noise specific to that sample [9] [10]. This guide objectively compares the three pillars of model assessment—Discrimination, Calibration, and Overall Accuracy—providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data needed for robust statistical validation.

Defining the Key Performance Aspects

Discrimination

- Definition: Discrimination is a model's ability to separate distinct outcome classes. For instance, it quantifies how well a model distinguishes between patients who will experience an event (e.g., disease progression) from those who will not [9].

- Core Concept: A model with high discrimination assigns a higher predicted risk or probability to subjects who have the event compared to those who do not.

Calibration

- Definition: Calibration reflects the agreement between predicted probabilities and the actual observed event rates. It assesses the reliability of a model's probability estimates [9] [11].

- Core Concept: A perfectly calibrated model would mean that among 100 patients each assigned a risk of 20%, the event would occur for exactly 20 of them. Poor calibration has been identified as the 'Achilles heel' of predictive models, as it directly reduces a model's clinical utility and net benefit [9].

- Definition: Overall Accuracy is a general measure of a model's correctness. For classification models, it is typically defined as the proportion of total correct predictions (both positive and negative) among all predictions made [12] [10].

- Core Concept: While intuitive, accuracy can be a misleading metric, especially for imbalanced datasets where one outcome class is much more frequent than the other.

Quantitative Comparison of Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the key metrics, their interpretation, and comparative data for evaluating discrimination, calibration, and accuracy.

Table 1: Core Evaluation Metrics for Discrimination, Calibration, and Accuracy

| Performance Aspect | Key Metric(s) | Interpretation & Calculation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) [9] [12] | Proportion of randomly selected patient pairs (one with, one without the event) where the model assigns a higher risk to the patient with the event. Ranges from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination). | 0.8 - 0.9 (Excellent), >0.9 (Outstanding) |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) Statistic [12] | Measures the degree of separation between the positive and negative distributions. Higher values indicate better separation. | 0 (No separation) to 100 (Perfect separation) | |

| Calibration | Calibration Slope [9] [11] | Slope of the linear predictor in a validation model. A slope of 1 indicates perfect calibration, <1 suggests overfitting, and >1 suggests underfitting. | ~1.0 |

| Calibration-in-the-Large [9] | Compares the overall observed event rate to the average predicted risk. Assesses whether the model systematically over- or under-predicts. | ~0.0 | |

| Hosmer-Lemeshow Test [11] | A goodness-of-fit test comparing predicted and observed events across risk groups. A low chi-square statistic and p-value >0.05 suggest good calibration. | p > 0.05 | |

| Brier Score [9] | The mean squared difference between the predicted probabilities and the actual outcomes (0 or 1). A proper scoring rule that combines discrimination and calibration. | 0 (Perfect) to 0.25 (Worthless) | |

| Overall Accuracy | Accuracy [12] [10] | (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Predictions. The overall proportion of correct predictions. | Higher is better, but context-dependent. |

| F1 Score [12] | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. Provides a single score that balances the two concerns. Useful for imbalanced datasets. | 0 to 1, higher is better. |

Table 2: Example Performance Comparison of Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Models

This table summarizes data from a systematic review comparing the performance of laboratory-based and non-laboratory-based models on external validation cohorts [11].

| Model Type | Median C-Statistic (IQR) | C-Statistic Difference (vs. Lab-based) | Calibration Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Based | 0.74 (0.72 - 0.77) | (Reference) | Similar to non-lab models, but non-calibrated equations often overestimated risk. |

| Non-Laboratory-Based | 0.74 (0.70 - 0.76) | Median Absolute Difference: 0.01 (Very Small) | Similar to lab models, but non-calibrated equations often overestimated risk. |

Table 3: The Researcher's Toolkit for Model Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Provides libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, rms, pROC) for calculating all key metrics and performing resampling. |

| Resampling Methods (Bootstrap, Cross-Validation) | Core techniques for internal validation to estimate model optimism and correct for overfitting [9]. |

| Validation Dataset | An independent, unseen dataset held out from the model development process, essential for external validation [9]. |

| Fairness Metrics (e.g., Equalized Odds, Demographic Parity) | Tools to evaluate potential disparities in model performance across sensitive subgroups like sex, race, or ethnicity [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Assessment

Protocol for Internal Validation using Resampling

Aim: To estimate the optimism in model performance metrics due to overfitting using only the development dataset [9].

- Bootstrap Resampling: Repeatedly draw many samples (e.g., 1000) with replacement from the original development dataset. Each sample should be the same size as the original dataset.

- Model Development & Testing: For each bootstrap sample:

- Develop the model using the same entire procedure (variable selection, parameter tuning) on the bootstrap sample.

- Calculate the apparent performance (e.g., AUC, Brier score) of this model on the same bootstrap sample.

- Calculate the test performance of this model on the original dataset (or the data points not in the bootstrap sample, known as the out-of-bag sample).

- Optimism Calculation: For each bootstrap iteration, compute the optimism as the difference between the apparent performance and the test performance.

- Performance Correction: Calculate the average optimism across all iterations. Subtract this average optimism from the apparent performance of the model developed on the original full dataset to obtain an optimism-corrected performance estimate.

Protocol for External Validation

Aim: To quantify the model's performance and generalizability in a fully independent participant sample from a different location or time period [9] [11].

- Dataset Acquisition: Obtain a dataset that was not used in any part of the model development process. The population can be from a different clinical site, geographic region, or time period.

- Apply Model: Apply the exact, finalized model (including the same coefficients and intercept) to the new data to generate predictions for each individual.

- Measure Performance: Calculate all relevant performance metrics—including discrimination (AUC), calibration (calibration slope, intercept, and plot), and overall accuracy—directly on this new dataset.

- Analyze Calibration: Create a calibration plot:

- Stratify the validation cohort into groups (e.g., deciles) based on their predicted risk.

- For each group, plot the mean predicted risk against the observed event rate (with confidence intervals).

- Fit a logistic regression of the observed outcome on the log-odds of the predicted probability to estimate the calibration intercept and slope.

Relationships and Workflows in Model Validation

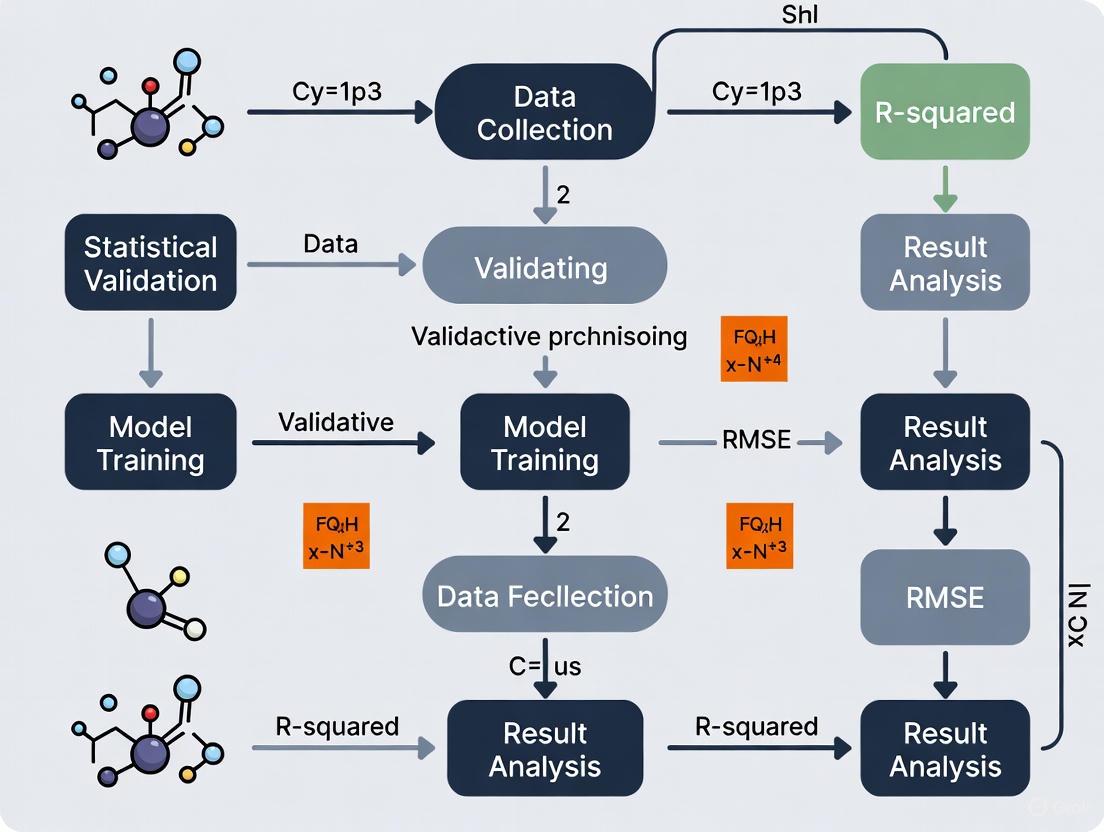

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in the model validation process, highlighting the roles of discrimination, calibration, and accuracy.

Model Validation Workflow

Critical Considerations for Researchers

The Interplay of Metrics and Potential Pitfalls

- The Limitation of Discrimination: A model can have high discrimination (AUC) but poor calibration, leading to systematically biased risk estimates that are clinically harmful [9]. Furthermore, recent research highlights that a model can retain high discrimination after implementation and still harm patients if it creates "harmful self-fulfilling prophecies"—where the model's predictions directly influence decisions that make the prediction come true, without improving outcomes [14].

- The Insensitivity of C-Statistics: When comparing models, a difference in the c-statistic (AUC) of less than 0.025 is generally considered "very small" [11]. As shown in Table 2, laboratory and non-laboratory-based models can show nearly identical discrimination, demonstrating that this metric is insensitive to the inclusion of additional predictors. The clinical value of new predictors may be better assessed by their hazard ratios and impact on reclassification metrics [11].

- The Bias-Variance Trade-off: Both overfitting and underfitting are critical pitfalls. Overfitting occurs when a model is too complex and learns noise from the training data, leading to poor performance on new data. Underfitting occurs when a model is too simple to capture the underlying trends in the data [10]. Techniques like cross-validation and regularization are essential to find the right balance.

The Critical Role of Fairness and Reporting

- Algorithmic Fairness: As predictive models are integrated into clinical care, it is vital to evaluate their performance across sensitive demographic subgroups (e.g., sex, race, ethnicity). Fairness metrics, such as Equalized Odds and Demographic Parity, are tools to detect disparities [13]. However, a 2025 review found that the use of these metrics in clinical risk prediction literature remains rare, and training data are often racially and ethnically homogeneous, risking the perpetuation of health inequities [13].

- Robust External Validation: The common practice of using a simple train-test split for validation can fail for spatial or temporal data because it violates the assumption that data points are independent and identically distributed [15]. For such data, validation techniques that account for geographic or temporal correlation are necessary for reliable performance estimates [15].

In predictive model research, particularly for binary outcomes in fields like clinical development and epidemiology, statistical validation is paramount for assessing model reliability and accuracy. Three core metrics form the foundation for evaluating probabilistic prediction models: the Brier Score, the C-statistic, and various calibration measures. The Brier Score provides an overall measure of prediction accuracy, the C-statistic (or concordance index) evaluates the model's ranking ability, and calibration measures assess the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. Together, these metrics offer complementary insights into model performance, with the Brier Score uniquely incorporating aspects of both discrimination and calibration [16]. Understanding their distinct properties, interpretations, and interrelationships enables researchers to perform comprehensive model validation and select the most appropriate models for specific applications, ultimately supporting robust decision-making in drug development and clinical research.

Metric Definitions and Core Concepts

Brier Score

The Brier Score (BS) is a strictly proper scoring rule that measures the accuracy of probabilistic predictions for binary or categorical outcomes. It represents the mean squared difference between the predicted probabilities and the actual outcomes, serving as an overall measure of prediction error [17] [18] [19].

Formula: For a set of N predictions, the Brier Score is calculated as:

( BS = \frac{1}{N} \sum{t=1}^{N} (ft - o_t)^2 )

where ( ft ) is the forecast probability (between 0 and 1) and ( ot ) is the actual outcome (0 or 1) [17] [18].

Interpretation: The score ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 represents perfect accuracy and 1 indicates perfect inaccuracy [17] [19].

Extension: For multi-category outcomes with R classes, the Brier Score extends to:

( BS = \frac{1}{N} \sum{t=1}^{N} \sum{i=1}^{R} (f{ti} - o{ti})^2 )

where the probabilities across all classes for each event must sum to 1 [18] [19].

C-Statistic (Concordance Statistic)

The C-statistic (C), also known as the concordance index or C-index, measures the discriminative ability of a model—its capacity to separate those who experience an event from those who do not [20] [21] [22].

Definition: The C-statistic represents the probability that a randomly selected subject who experienced the event has a higher predicted risk than a randomly selected subject who did not experience the event [20] [22]. It is equivalent to the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) [20] [22].

Interpretation: Values range from 0 to 1, where:

- 0.5 indicates no discrimination better than chance

- 0.7-0.8 suggests acceptable discrimination

- 0.8-0.9 indicates excellent discrimination

- 1.0 represents perfect discrimination [22]

Limitation: The C-statistic is often conservative and can be insensitive to meaningful improvements in model performance, particularly when new biomarkers are added to already robust models [21].

Calibration Measures

Calibration refers to the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed event rates. A well-calibrated model that predicts a 70% chance of an event should see that event occur approximately 70% of the time across many such predictions [23] [24].

Confidence Calibration: A model is considered confidence-calibrated if for all confidence levels c, the model is correct c proportion of the time:

( \mathbb{P}(Y = \text{arg max}(\hat{p}(X)) | \text{max}(\hat{p}(X)) = c) = c \ \forall c \in [0, 1] ) [23]

Expected Calibration Error (ECE): A widely used measure that bins predictions and calculates the weighted average of the difference between accuracy and confidence across bins:

( ECE = \sum{m=1}^{M} \frac{|Bm|}{n} |\text{acc}(Bm) - \text{conf}(Bm)| )

where ( B_m ) is the m-th bin, acc is the average accuracy, and conf is the average confidence in that bin [23].

Multi-class and Class-wise Calibration: Extends the concept beyond binary outcomes to multiple classes, requiring alignment between predicted probability vectors and actual class distributions [23].

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Validation Metrics

| Metric | Primary Function | Measurement Range | Optimal Value | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brier Score | Overall prediction accuracy | 0 to 1 | 0 | Strictly proper scoring rule; incorporates both discrimination and calibration |

| C-statistic | Discrimination ability | 0 to 1 | 1 | Intuitive interpretation; equivalent to AUC; widely understood |

| Calibration Measures | Agreement between predicted and observed probabilities | Varies by measure | 0 (for ECE) | Direct assessment of probability reliability; crucial for clinical decision-making |

Table 2: Metric Limitations and Complementary Uses

| Metric | Key Limitations | Best Paired With | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brier Score | Does not directly incorporate clinical costs; insufficient for clinical utility alone [16] | Calibration measures | Provides overall accuracy assessment but lacks cost-sensitive evaluation |

| C-statistic | Conservative; insensitive to model improvements; ignores calibration [21] | Brier Score, calibration plots | Assesses ranking ability but not magnitude of risk differences |

| Calibration Measures | ECE sensitive to binning strategy; does not measure discrimination [23] | Brier Score, C-statistic | Critical for probability interpretation in treatment decisions |

Methodologies for Metric Calculation

Brier Score Calculation Protocol

The Brier Score can be decomposed into three additive components, providing deeper insight into the sources of prediction error [18]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Collect N prediction-outcome pairs (f, o) where f is the predicted probability (0-1) and o is the actual outcome (0 or 1)

- Direct Calculation: Compute ( BS = \frac{1}{N} \sum{t=1}^{N} (ft - o_t)^2 )

- Reference Calculation: For comparison, compute the reference Brier Score using climatology: ( BS{ref} = \frac{1}{N} \sum{t=1}^{N} (\bar{o} - o_t)^2 ) where ( \bar{o} ) is the overall event rate

- Brier Skill Score Calculation: Determine relative improvement: ( BSS = 1 - \frac{BS}{BS_{ref}} ) [18] [19]

Interpretation: The Brier Skill Score ranges from -∞ to 1, where positive values indicate improvement over the reference forecast, 0 indicates no improvement, and negative values indicate worse performance [17] [19].

C-Statistic Derivation Methodology

Analytical Derivation under Binormality [20]:

- Assumption: Continuous explanatory variable follows normal distribution in both affected (Y=1) and unaffected (Y=0) populations

- Calculation: With means μA and μU and variances σA² and σU² in affected and unaffected groups:

- General case: ( C = \Phi(\frac{\muA - \muU}{\sqrt{\sigmaA^2 + \sigmaU^2}}) = \Phi(\frac{d}{\sqrt{2}}) ) where d is Cohen's effect size

- Equal variances: ( C = \Phi(\frac{\sigma\beta}{\sqrt{2}}) ) where β is the log-odds ratio

- Empirical Estimation: Using all possible pairs of subjects where one experienced the event and one did not, calculate the proportion where the subject with the event had higher predicted risk [20]

Calibration Assessment Protocol

Expected Calibration Error (ECE) Calculation [23]:

- Binning: Partition predictions into M bins (typically 10) of equal interval (0-0.1, 0.1-0.2, ..., 0.9-1.0)

- Bin Statistics: For each bin Bm, calculate:

- Accuracy: ( acc(Bm) = \frac{1}{|Bm|} \sum{i \in Bm} \mathbb{1}(\hat{y}i = yi) )

- Confidence: ( conf(Bm) = \frac{1}{|Bm|} \sum{i \in Bm} \hat{p}(x_i) )

- ECE Computation: ( ECE = \sum{m=1}^{M} \frac{|Bm|}{n} |acc(Bm) - conf(Bm)| )

Reliability Diagrams: Visual representation of calibration by plotting expected accuracy (confidence) against observed accuracy (true frequency) for each bin [24].

Advanced Concepts and Recent Developments

Brier Score Decomposition

The Brier Score can be decomposed to provide deeper insights into model performance [18]:

Three-component decomposition: ( BS = REL - RES + UNC ) where REL is reliability (calibration), RES is resolution, and UNC is uncertainty

Two-component decomposition: ( BS = CAL + REF ) where CAL is calibration and REF is refinement

The uncertainty component measures inherent outcome variability, resolution measures how much forecasts differ from the average outcome, and reliability measures how close forecasts are to the actual probabilities [18].

Weighted Brier Score for Clinical Utility

Traditional Brier Score is limited in assessing clinical utility as it weights all prediction errors equally regardless of clinical consequences [16]. The weighted Brier score incorporates clinical utility by aligning with decision-theoretic frameworks:

- Framework: Considers different costs for false positives and false negatives in clinical decisions

- Implementation: Uses cost-weighted misclassification loss functions that balance trade-offs between false positives and false negatives

- Advantage: Provides a single measure incorporating calibration, discrimination, and clinical utility [16]

Relationship Between Metrics

The C-statistic primarily measures discrimination, calibration measures assess probability agreement, while the Brier Score incorporates both aspects. Under the assumption of binormality (explanatory variable normally distributed in both outcome groups), the C-statistic follows a standard normal cumulative distribution with dependence on the product of the standard deviation and the log-odds ratio [20]. This relationship highlights that discriminative ability depends on both the effect size and population heterogeneity.

Visual Guide to Metric Relationships

Figure 1: Relationship between predictive model validation metrics and their composite contributions to clinical utility assessment

Figure 2: Brier Score calculation workflow and decomposition process

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Predictive Model Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Research Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python with scikit-learn | Metric calculation and model validation | sklearn.metrics.brier_score_loss, roc_auc_score |

| Calibration Visualization | Reliability diagrams, Calibration curves | Visual assessment of probability calibration | Plotting expected vs. observed probabilities by bin |

| Model Validation Frameworks | ROC analysis, Decision curve analysis | Comprehensive model performance assessment | Calculating net benefit across probability thresholds |

| Clinical Utility Assessment | Weighted Brier score, Net benefit functions | Incorporating clinical consequences into evaluation | Applying cost-weighted loss functions for clinical decisions |

The Brier Score, C-statistic, and calibration measures provide distinct but complementary insights into predictive model performance. The Brier Score offers an overall measure of prediction accuracy that incorporates both discrimination and calibration, the C-statistic specifically evaluates ranking ability, and calibration measures assess the reliability of probability estimates. For comprehensive model validation, researchers should consider all three metrics rather than relying on a single measure. Recent developments, such as weighted Brier scores that incorporate clinical utility, represent promising advances for aligning statistical evaluation with clinical decision-making. By understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts for each metric, researchers in drug development and clinical research can make more informed decisions about model selection and implementation.

The Role of Validation in Clinical Decision-Making and Regulatory Science

Validation serves as the foundational bridge between innovative predictive models and their reliable application in clinical and regulatory settings. In both clinical decision-making and regulatory science, validation transforms theoretical algorithms into trusted tools for patient care and drug development. As defined by regulatory bodies, validation provides "objective evidence that a process consistently produces a result meeting predetermined specifications," ensuring that predictive models perform as intended in real-world scenarios [25]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) emphasizes that active innovation in regulatory science is required to keep pace with accelerating technological advances, underscoring validation's role in protecting human and animal health [26].

The year 2025 represents a pivotal moment for validation practices, with nearly 60% of U.S. hospitals projected to adopt AI-assisted predictive tools in routine clinical care, a significant increase from approximately 35% in 2022 [27]. This rapid adoption necessitates robust validation frameworks to ensure these technologies deliver accurate, reliable, and equitable healthcare outcomes. Validation provides the critical evidence base that allows healthcare professionals, patients, and regulatory authorities to trust predictive models guiding medical decisions [28] [29].

Core Principles of Predictive Model Validation

The Validation Lifecycle

The validation of clinical prediction models follows a structured pathway from development through implementation. This lifecycle approach ensures models remain accurate and relevant throughout their operational use. According to foundational texts in clinical prediction models, a "practical checklist" guides development of valid prediction models, encompassing preliminary considerations, handling missing values, predictor coding, selection of main effects and interactions, and model parameter estimation with shrinkage methods [29].

The core principles of clinical prediction model validation include both internal and external validation techniques. Internal validation assesses model performance using the original development dataset, typically through methods like bootstrapping or cross-validation, which provide optimism-adjusted performance measures. External validation evaluates whether a model developed in one setting performs adequately in different populations or healthcare settings, testing its transportability and generalizability [28]. This distinction is crucial for determining whether a model requires updating or complete recalibration when deployed in new environments.

Performance Metrics and Evaluation

Comprehensive model evaluation extends beyond simple discrimination metrics to include calibration and clinical utility. Standard validation metrics include:

- Discrimination: The model's ability to distinguish between different outcome classes, typically measured by the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) or C-statistic [30].

- Calibration: The agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes, often visualized using calibration plots [28] [29].

- Clinical Utility: The net benefit of using a model for clinical decision-making across various probability thresholds, evaluated through decision curve analysis [29].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Predictive Model Validation

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Interpretation | Optimal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrimination | AUC-ROC, C-statistic | Ability to distinguish between outcome classes | >0.7 (acceptable), >0.8 (good), >0.9 (excellent) |

| Calibration | Calibration slope, intercept | Agreement between predictions and observed outcomes | Slope close to 1, intercept close to 0 |

| Overall Performance | Brier score, R² | Accuracy of probabilistic predictions | Lower Brier score indicates better accuracy |

| Clinical Utility | Decision Curve Analysis | Net benefit across decision thresholds | Positive net benefit versus default strategies |

Regulatory Validation Frameworks to 2025

Evolving Regulatory Expectations

Regulatory science is undergoing significant transformation to address emerging challenges in medicine development and evaluation. The EMA's Regulatory Science to 2025 strategy reflects stakeholder priorities for enhancing evidence generation throughout a medicine's lifecycle [26]. This strategy acknowledges that regulators must innovate both science and processes themselves rather than maintaining "business as usual" approaches [26].

Key regulatory trends impacting validation include increased emphasis on computer system validation (CSV), process validation aligned with lifecycle management, and data integrity in validation processes [25]. The integration of real-world evidence and digital health technologies into regulatory decision-making requires novel validation approaches that maintain scientific rigor while accommodating new data types. Regulatory agencies are particularly focused on risk-based validation approaches that prioritize resources based on the potential impact on product quality and patient safety [25].

Validation in Pharmaceutical Contexts

Pharmaceutical validation extends beyond predictive models to encompass manufacturing processes, analytical methods, and cleaning procedures. Preparation for pharmaceutical validation in 2025 involves anticipating regulatory trends and adopting advanced technologies while enhancing traditional validation practices [25]. The transition from traditional validation methods to continuous process validation (CPV) represents a significant shift, using real-time data to monitor and validate manufacturing processes throughout their lifecycle [25].

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Validation Framework Components for 2025

| Validation Domain | Key Requirements | Emerging Technologies | Regulatory Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computer System Validation | Data integrity, security, electronic records | Blockchain for traceability, paperless validation systems | 21 CFR Part 11, ALCOA+ principles |

| Process Validation | Lifecycle approach, real-time monitoring | Process Analytical Technology, IoT sensors | FDA Process Validation Guidance (2011) |

| Cleaning Validation | Scientifically justified limits, contamination control | Modern analytical methods, automation | EMA Guidelines on setting health-based exposure limits |

| Analytical Method Validation | Accuracy, precision, specificity | Advanced spectroscopy, chromatography | ICH Q2(R2) Guideline |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Future-Guided Learning for Time-Series Forecasting

Recent advances in validation methodologies include sophisticated approaches like Future-Guided Learning for enhancing time-series forecasting. This protocol employs a dynamic feedback mechanism inspired by predictive coding theory, using two models: a detection model that analyzes future data to identify critical events, and a forecasting model that predicts these events based on current data [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Architecture: Implement two separate models - a "teacher" detection model with access to short-term future data and a "student" forecasting model using only current and historical data.

- Training Procedure: When discrepancies occur between forecasting and detection models, apply significant parameter updates to the forecasting model to minimize prediction surprise.

- Evaluation Metrics: Quantify performance using AUC-ROC for event prediction tasks and Mean Squared Error for regression forecasting.

- Validation: Apply rigorous internal validation through cross-validation and external validation on completely separate datasets [30].

This approach demonstrated a 44.8% increase in AUC-ROC for seizure prediction using EEG data and a 23.4% reduction in MSE for forecasting in nonlinear dynamical systems [30]. The method showcases how innovative validation frameworks can substantially enhance model performance while maintaining methodological rigor.

Machine Learning Classifier Validation

A comprehensive study on machine learning classifiers for construction quality and schedule prediction provides a transferable protocol for clinical and regulatory applications. The research utilized nine ML classifiers including MLP, SVM, KNN, LDA, LR, DT, RF, AdaBoost, and Gradient Boosting, systematically comparing their performance on standardized inspection data [31].

Experimental Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Address missing values, normalize features, and handle class imbalance through appropriate sampling techniques.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Systematically tune model parameters using grid search or Bayesian optimization with cross-validation.

- Model Training: Implement appropriate regularization techniques to prevent overfitting and ensure generalizability.

- Performance Evaluation: Assess models using multiple metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Identify which input features most significantly impact model predictions to enhance interpretability [31].

This structured validation protocol highlights the importance of comparing multiple algorithms rather than relying on a single modeling approach, particularly for high-stakes applications in regulatory science and clinical decision-making.

Comparative Performance of Validation Techniques

Quantitative Validation Metrics

Different validation approaches yield substantially different performance outcomes, as demonstrated by comparative studies across domains. In clinical settings, biomarker-based predictive models have shown significant improvements in early disease identification, with some applications achieving up to 48% improvement in early detection rates [27]. The integration of multi-omics data with advanced analytical methods has improved early Alzheimer's disease diagnosis specificity by 32%, providing a crucial intervention window [32].

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Predictive Modeling Techniques

| Model Category | Best Application Context | Performance Strengths | Validation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistical Models | Small datasets, strong prior knowledge | High interpretability, clinical acceptance | Prone to bias with correlated predictors |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | High-dimensional data, complex interactions | Handles non-linear relationships, robust to multicollinearity | Requires large samples, hyperparameter tuning critical |

| Deep Learning Models | Image, temporal, and multimodal data | Superior accuracy for complex patterns | "Black box" limitations, extensive computational needs |

| Time-Series Forecasting | Longitudinal data, dynamic systems | Captures temporal dependencies, trend analysis | Sensitive to non-stationary data, requires specialized validation |

Addressing Validation Challenges

Even with robust protocols, significant challenges persist in predictive model validation. Biomarker-based models face particular hurdles including data heterogeneity, inconsistent standardization protocols, limited generalizability across populations, high implementation costs, and substantial barriers in clinical translation [32]. These challenges necessitate integrated frameworks prioritizing multi-modal data fusion, standardized governance protocols, and interpretability enhancement [32].

In regulatory contexts, validation must also address ethical considerations such as algorithmic bias mitigation. If historical data reflects societal biases or inequalities, predictive analytics could perpetuate these issues in decision-making processes [27]. Organizations must prioritize fairness in their algorithms by implementing measures to identify and mitigate bias during model development and validation [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing robust validation frameworks requires specific methodological tools and approaches. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for predictive model validation in clinical and regulatory contexts.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Model Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python, SAS, IBM SPSS Modeler | Model development, performance metrics, visualization | General predictive modeling, comprehensive analysis |

| Time-Series Analysis | Prophet, ARIMA models | Specialized forecasting, seasonality handling | Longitudinal data, dynamic system prediction |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Algorithm implementation, hyperparameter tuning | High-dimensional data, complex pattern recognition |

| Data Standards | CDISC, OMOP Common Data Model | Data harmonization, interoperability | Multi-site studies, regulatory submissions |

| Validation Frameworks | CARP, TRIPOD, PROBAST | Methodological guidance, reporting standards | Study design, protocol development, manuscript preparation |

| Visualization Tools | Tableau, ggplot2, matplotlib | Performance communication, exploratory analysis | Result interpretation, stakeholder engagement |

Visualization of Validation Workflows

Clinical Prediction Model Development Pathway

Regulatory Validation Decision Framework

Validation represents both a scientific discipline and a strategic imperative in clinical decision-making and regulatory science. As predictive technologies continue to evolve, validation frameworks must similarly advance to ensure these tools deliver safe, effective, and equitable outcomes. The EMA's Regulatory Science to 2025 initiative highlights the critical importance of stakeholder engagement and collaborative approaches to validation in an era of rapid innovation [26].

Future directions in validation science include expanded application to rare diseases, incorporation of dynamic health indicators, strengthened integrative multi-omics approaches, conduct of longitudinal cohort studies, and leveraging edge computing solutions for low-resource settings [32]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on real-world evidence and continuous monitoring of deployed models will require more adaptive validation frameworks that can accommodate iterative learning systems while maintaining rigorous oversight.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering validation principles and practices is no longer optional but essential for translating predictive models into clinically useful tools and regulatory-approved solutions. By adhering to robust validation standards while innovating new approaches, the scientific community can harness the full potential of predictive technologies to advance patient care and public health.

Key Validation Metrics and Performance Assessment Techniques

The performance of prediction models is critically assessed using a variety of methods and metrics to ensure their reliability and appropriateness for real-world applications [33]. In evidence-based medicine, well-validated risk scoring systems play an indispensable role in selecting prevention and treatment strategies by predicting the occurrence of clinical events [34]. Traditional measures for evaluating models with binary and survival outcomes include the Brier score for overall model performance, the concordance statistic (C-statistic) for discriminative ability, and goodness-of-fit statistics for calibration [33]. These metrics provide complementary insights into different aspects of model performance, with discrimination measuring how well models separate those with and without outcomes, and calibration assessing the accuracy of the absolute risk estimates [35].

Despite the emergence of newer measures, reporting discrimination and calibration remains fundamental for any prediction model [33]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three traditional performance measures, offering researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge needed for robust statistical validation of predictive models in medical research.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, interpretations, and optimal values for the Brier score, C-statistic, and calibration slope.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Performance Measures for Predictive Models

| Metric | Primary Function | Interpretation | Optimal Value | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brier Score | Overall performance measurement [33] | Mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes [36] | 0 (perfect) [36] | Strictly proper scoring rule; evaluates both discrimination and calibration [37] | Difficult to interpret without context; value range depends on incidence [37] |

| C-statistic (AUC) | Discrimination assessment [33] | Probability that a random patient with event has higher risk score than one without event [34] | 1 (perfect discrimination) | Intuitive interpretation; handles censored data [38] [34] | Does not measure prediction accuracy [38]; insensitive to calibration [35] |

| Calibration Slope | Calibration evaluation [35] | Spread of estimated risks; slope of linear predictor [33] | 1 (perfect calibration) | Identifies overfitting (slope <1) or underfitting (slope >1) [35] | Does not fully capture calibration; requires sufficient sample size [35] |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Brier Score: Protocol for Implementation and Interpretation

Calculation Methodology

The Brier score represents a quadratic scoring rule calculated as the mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes [33]. For binary outcomes, the mathematical formulation is:

BS(p,y) = 1/n × Σ(pi - yi)² [37]

where:

- n = total number of predictions

- pi = predicted probability of event for case i

- yi = actual outcome (1 if event occurred, 0 otherwise) [37]

The Brier score ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 represents perfect accuracy and 1 indicates the worst possible performance [36]. However, the maximum value for a non-informative model depends on the outcome incidence; for a 50% incidence, the maximum is 0.25, while for a 10% incidence, it is approximately 0.09 [33].

Interpretation Guidelines

When interpreting Brier scores, researchers should avoid common misconceptions. A Brier score of 0 is theoretically perfect but practically improbable, as it requires extreme predictions (0% or 100%) that exactly match outcomes [37]. Lower Brier scores generally indicate better performance, but comparisons should only be made within the same population and context, as the score depends on the underlying outcome distribution [37]. Importantly, a low Brier score does not necessarily indicate good calibration, as these measure different aspects of model performance [37].

C-statistic: Protocol for Implementation and Interpretation

Calculation Methodology

The C-statistic measures discrimination—the ability to distinguish between patients who experience an event earlier versus those who experience it later or not at all [38]. For survival outcomes, the calculation involves comparing pairs of patients:

C = Pr(g(Z₁) > g(Z₂) ∣ T₂ > T₁) [34]

where:

- g(Z) = risk score derived from the model

- T = event time

- The subscript indicates two independent patients [34]

In practice, the C-statistic is computed as the proportion of concordant pairs among all usable pairs [38] [34]. A pair is concordant if the patient with the shorter observed event time has a higher risk score. Modifications exist to handle censored observations, such as Harrell's C-statistic and Uno's C-statistic, with the latter being less dependent on the study-specific censoring distribution [38] [34].

Interpretation Guidelines

The C-statistic ranges from 0.5 (no discriminative ability) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) [34]. However, it's crucial to recognize that the C-statistic quantifies only the model's ability to rank patients according to risk, not the accuracy of the predicted risk values themselves [38]. Two models with identical C-statistics can have substantially different prediction accuracy, particularly if one uses transformed predictors [38].

Calibration Slope: Protocol for Implementation and Interpretation

Calculation Methodology

The calibration slope evaluates the spread of estimated risks and is an essential aspect of both internal and external validation [33]. It is obtained by fitting a logistic regression model to the outcome using the linear predictor of the original model as the only covariate:

logit(pᵢ) = α + β × LPᵢ

where:

- pᵢ = predicted probability for patient i

- LPᵢ = linear predictor from the original model

- β = calibration slope [35]

The linear predictor LPᵢ is typically the sum of the product of regression coefficients and predictor values from the original model.

Interpretation Guidelines

The target value for the calibration slope is 1 [35]. A slope less than 1 indicates that predictions are too extreme (overfitting), meaning high risks are overestimated and low risks are underestimated [35]. Conversely, a slope greater than 1 suggests that risk estimates are too moderate (underfitting) [35]. It's important to note that the calibration slope alone does not fully capture model calibration, as it primarily measures the spread of risk estimates rather than their absolute accuracy [39].

Relationships Between Performance Measures

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationships between the three performance measures and what they assess in a predictive model.

Figure 1: Interrelationships between traditional performance measures in predictive model validation

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Study

In a recent study predicting cardiovascular composite outcomes in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, three Cox models were evaluated using traditional performance measures [38]. The model with 21 variables demonstrated a C-statistic of 0.76, while a simplified model containing only log NT-proBNP achieved a C-statistic of 0.72 [38]. This minimal difference in discrimination, despite dramatic differences in model complexity, highlights how the C-statistic alone may not fully capture clinical utility.

Esophageal Cancer Risk Model Comparison

A comparison of standard and penalized logistic regression models for predicting pathologic nodal disease in esophageal cancer patients revealed remarkably consistent performance across measures [40]. The standard regression and four penalized regression models had nearly identical Brier scores (0.138-0.141), C-statistics (0.775-0.788), and calibration slopes (0.965-1.05) [40]. This case demonstrates that when datasets are large and outcomes relatively frequent, different modeling approaches may yield similar predictive performance as measured by traditional metrics.

Cardiovascular Model Calibration Comparison

An external validation study of QRISK2-2011 and NICE Framingham models in 2 million UK patients demonstrated the critical importance of calibration [35]. Although both models had similar C-statistics (0.771 vs. 0.776), the Framingham model significantly overestimated risk [35]. At the 20% risk threshold for intervention, QRISK2-2011 identified 110 per 1000 men as high-risk, while Framingham identified nearly twice as many (206 per 1000) due to miscalibration [35]. This case illustrates how poor calibration can lead to substantial overtreatment even when discrimination appears adequate.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Analytical Tools for Predictive Model Validation

| Tool | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Calculation of performance metrics | R: rms, survival packages; Python: scikit-learn |

| Calibration Curves | Visual assessment of risk accuracy | Plotting observed vs. predicted probabilities by risk decile [35] |

| Kaplan-Meier Estimator | Handling censored data in C-statistic | Nonparametric survival curve estimation for risk stratification [34] |

| Penalized Regression | Preventing overfitting | Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net for improved calibration [40] |

| Validation Cohorts | External performance assessment | Split-sample, bootstrap, or external dataset validation [33] |

The Brier score, C-statistic, and calibration slope provide complementary insights into different aspects of predictive model performance. The Brier score offers an overall measure of prediction accuracy, the C-statistic quantifies the model's ability to discriminate between outcomes, and the calibration slope assesses the appropriateness of the absolute risk estimates. Researchers should report all three measures to provide a comprehensive assessment of model performance, with particular attention to calibration when models inform clinical decisions [33] [35]. No single metric captures all aspects of model performance, and the choice of emphasis should align with the intended application of the predictive model.

In the field of predictive model research, traditional performance metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) offer limited insight because they measure diagnostic accuracy without accounting for clinical consequences or patient preferences [41] [42]. Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) has emerged as a decision-analytic method that evaluates the clinical utility of prediction models and diagnostic tests by quantifying the net benefit across a range of clinically reasonable threshold probabilities [43] [44]. First introduced by Vickers and Elkin in 2006, DCA addresses a critical gap in model evaluation by integrating the relative value that patients and clinicians place on different outcomes (e.g., true positives vs. false positives) into the assessment framework [42] [45]. This approach allows researchers and drug development professionals to determine whether a model, despite having good statistical accuracy, is truly useful for guiding clinical decisions and improving patient outcomes.

The core principle of DCA is to compare the net benefit of using a prediction model against two default strategies: intervening on all patients or intervening on no patients [42] [43]. "Intervention" is defined broadly and can include administering a drug, performing a surgery, conducting a diagnostic workup, or providing lifestyle advice [42]. By using net benefit as a standardized measure that combines model performance with clinical consequences, DCA provides a more pragmatic and patient-centered framework for model validation than traditional statistical metrics alone.

Core Principles and Quantification of Net Benefit

The Concept of Threshold Probability

A foundational element of DCA is the threshold probability, denoted as ( p_t ) [41]. This represents the minimum probability of a disease or event at which a patient or clinician would decide to intervene. This threshold inherently reflects a personal valuation of the relative harms of unnecessary intervention (a false positive) versus missing a disease (a false negative) [42].

For example, in a prostate cancer biopsy scenario, a patient who is highly cancer-averse (perhaps due to family history) might opt for a biopsy even at a low predicted risk (e.g., 5%). This patient has a low threshold probability. Conversely, a patient who is more averse to the potential side effects of a biopsy might only proceed if the predicted risk is high (e.g., 30%), indicating a high threshold probability [42]. The DCA framework acknowledges that no single threshold fits all patients, and therefore evaluates model performance across a range of reasonable threshold probabilities [41].

Calculating Net Benefit

The net benefit is the key quantitative output of a DCA, providing a single metric that balances the benefits of true positives against the harms of false positives, weighted by the threshold probability [41]. The standard formula for net benefit for the treated is:

[ \text{net benefit}{\text{treated}} = \frac{\text{TP}}{n} - \frac{\text{FP}}{n} \times \left(\frac{pt}{1 - p_t}\right) ]

Where:

- TP = Number of True Positives

- FP = Number of False Positives

- n = Total number of subjects

- ( p_t ) = Threshold probability [41]

This calculation can be adapted to focus on untreated patients or an overall net benefit, but the ranking of models typically remains consistent across these variations [41]. The net benefit is calculated for each strategy (the model, "treat all," and "treat none") across the entire range of threshold probabilities. A model is considered clinically useful at a specific threshold if its net benefit surpasses that of the "treat all" and "treat none" strategies for that value of ( p_t ) [41] [43].

DCA Versus Traditional Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the critical distinctions between DCA and traditional metrics for evaluating predictive models.

Table 1: Comparison of DCA with Traditional Model Evaluation Metrics

| Feature | Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) | Traditional Metrics (AUC, Sensitivity/Specificity) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Clinical utility and decision-making consequences [41] [43] | Diagnostic accuracy and statistical discrimination [41] |

| Incorporation of Preferences | Explicitly integrates patient/clinician preferences via threshold probability (( p_t )) [41] [42] | Does not incorporate preferences or clinical consequences of decisions [42] |

| Result Interpretation | Identifies if and for whom (i.e., at what preferences) a model is useful [42] [43] | Indicates how well a model separates classes, but not if it improves decisions [41] |

| Reference Strategies | Directly compares against "treat all" and "treat none" default strategies [43] [44] | No comparison to simple default clinical strategies |

| Handling of Probability Thresholds | Evaluates all possible thresholds simultaneously [41] | A single, often arbitrary, threshold must be chosen for sensitivity/specificity [42] |

A key advantage of DCA is its ability to reveal that a model with a high AUC may not always offer superior clinical utility. A study comparing the Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS), leukocyte count, and serum sodium for suspected appendicitis found that while both PAS and leukocyte count had acceptable AUCs, their decision curves showed substantially different net benefit profiles [46]. This demonstrates that higher discrimination does not automatically translate to superior clinical value, a critical insight that traditional metrics fail to provide.

Experimental Protocols for Implementing DCA

Data Requirements and Model Preparation

To perform a DCA, you need a dataset with observed binary outcomes (e.g., disease present/absent) and the predicted probabilities from the model(s) you wish to evaluate [43]. These probabilities can come from a model developed on the same dataset (requiring internal validation to correct for overfitting) or from an externally published model applied to your validation cohort [41] [43].

Key Consideration: A common pitfall is evaluating a model on the same data used to build it without correcting for overfitting. This can lead to overly optimistic net benefit estimates. Bootstrap validation or cross-validation should be used to correct for this optimism [41].

Step-by-Step DCA Protocol

- Define the Clinical Decision: Clearly state the intervention (e.g., "biopsy," "prescribe drug") and the target outcome (e.g., "high-grade cancer," "disease recurrence") [42].

- Calculate Predicted Probabilities: For each patient in the validation dataset, obtain the predicted probability of the outcome from the model(s) under evaluation [43].

- Specify the Threshold Probability Range: Define a sequence of threshold probabilities (( p_t )) from just above 0% to just below 100%. The range can be restricted to clinically plausible values (e.g., 5% to 35%) for a clearer visualization [43].

- Compute Net Benefit for Each Strategy:

- For the Prediction Model: At each ( pt ), classify patients as "test positive" if their predicted probability ≥ ( pt ). Calculate net benefit using the formula in Section 2.2 [41].

- For "Treat All": This strategy has a net benefit of ( \pi - (1 - \pi)\frac{pt}{1 - pt} ), where ( \pi ) is the outcome prevalence [41].

- For "Treat None": This strategy always has a net benefit of 0 [41].

- Visualize the Results: Plot net benefit (y-axis) against threshold probability (x-axis) for all strategies [41] [43].

- Statistical Comparison (Optional): For a formal comparison between two models, use bootstrap methods to calculate confidence intervals and p-values for the difference in net benefit across the range of ( p_t ) [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit for DCA

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" for Implementing Decision Curve Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Platforms / Packages |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Provides the computational environment to perform data management, model fitting, and DCA calculations. | R, Stata, SAS, Python [44] |

| DCA Software Package | Dedicated functions that automate the calculation of net benefit and plotting of decision curves. | R: dcurves [43], rmda; Stata: dca [44] |

| Validation Dataset | A dataset with observed outcomes and model-predicted probabilities, used to evaluate the model's clinical utility. | Internally validated cohort or external validation dataset [43] |

| Bootstrap Routine | A resampling method used to correct for model overfitting and to calculate confidence intervals for net benefit. | Available in standard statistical software (e.g., R's boot package) [41] |

| Plotting System | A graphics library used to create the decision curve plot, ideally with smooth curves and confidence intervals. | R's ggplot2 system [41] |

Interpretation of Decision Curves and Case Study

How to Read a Decision Curve

Interpreting a decision curve involves a few simple steps [42]:

- Identify the Highest Line: At any given threshold probability on the x-axis, the strategy with the highest net benefit (the top line on the y-axis) is the preferred clinical strategy.

- Determine the Useful Range: A prediction model is clinically useful across the range of ( p_t ) where its net benefit is higher than both the "treat all" and "treat none" lines.

- Understand the Extremes: The "treat all" strategy typically has a high net benefit at very low thresholds (where missing a disease is considered far worse than an unnecessary intervention). The "treat none" strategy is only preferred at very high thresholds.

Case Study: Prostate Cancer Biopsy

A pivotal application of DCA is in evaluating models for predicting high-grade prostate cancer to guide biopsy decisions. In a study comparing two models—the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculator and a new model incorporating free PSA—traditional analysis showed both had reasonable AUCs (0.735 and 0.774, respectively). However, the PCPT model was miscalibrated [45].

The decision curve analysis revealed critical insights:

- The free PSA model (green line) demonstrated superior net benefit across a wide range of threshold probabilities compared to the default strategies [45].

- The PCPT model (orange line), despite its acceptable AUC, had lower net benefit than the "biopsy all" strategy for much of the range, indicating that using this model would lead to worse clinical outcomes than the current practice of biopsying everyone [45].

Table 3: Net Benefit Comparison in Prostate Cancer Biopsy Case Study (Selected Thresholds)

| Threshold Probability | Free PSA Model | PCPT Model | Biopsy All | Biopsy None |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 0.110 | 0.085 | 0.092 | 0.000 |

| 10% | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.042 | 0.000 |

| 15% | 0.055 | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.000 |

| 20% | 0.040 | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

Note: Net benefit values are illustrative approximations based on the case study description [45].

This case demonstrates DCA's power to identify a model that is not just statistically significant but clinically harmful, a conclusion that would be missed by relying on AUC alone.

Decision Curve Analysis represents a paradigm shift in the statistical validation of predictive models. By moving beyond pure accuracy metrics to a framework that incorporates clinical consequences and patient preferences, DCA provides a pragmatic and powerful tool for researchers and drug development professionals. It directly answers the critical question: "Will using this model improve patient decisions and outcomes?"

The experimental protocols and case studies outlined in this guide provide a foundation for implementing DCA in practice. As the demand for clinically actionable predictive models grows, DCA is poised to play an increasingly vital role in translating statistical predictions into tangible clinical benefits.

In predictive modeling research, particularly within medical and drug development contexts, the statistical validation of survival models is paramount. Survival analysis, or time-to-event analysis, deals with predicting the time until a critical event occurs, such as patient death, disease relapse, or recovery. A fundamental challenge in this domain is the presence of censored data, where the event of interest has not been observed for some subjects during the study period, meaning we only know that their true survival time exceeds their last observed time [47]. This characteristic necessitates specialized performance metrics that can handle such incomplete information. The research community has historically relied heavily on the Concordance Index (C-index) for evaluating survival models. However, a narrow focus on this single metric is increasingly recognized as insufficient, as it measures only a model's discriminative ability—how well it ranks patients by risk—and ignores other critical aspects like the accuracy of predicted probabilities and survival times [47]. A comprehensive evaluation strategy should integrate multiple metrics, primarily the C-index and the Integrated Brier Score (IBS), to provide a holistic view of model performance, assessing not just discrimination but also calibration and overall prediction error [33].

Core Metrics: Theoretical Foundations

The Concordance Index (C-index)

The Concordance Index, also known as the C-statistic, is a rank-based measure that evaluates a survival model's ability to correctly order patients by their relative risk. Intuitively, it calculates the proportion of all comparable pairs of patients in which the model's predictions and the observed outcomes agree. Formally, two patients are comparable if the one with the shorter observed time experienced the event (i.e., was not censored at that time). A comparable pair is concordant if the patient who died first had a higher predicted risk score; otherwise, it is discordant [48] [49].

The C-index is estimated using the following equation, where ( N ) is the number of comparable pairs: [ \text{C-index} = \frac{\text{Number of Concordant Pairs}}{N} ]

A C-index of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination, 0.5 indicates a model no better than random chance, and values below 0.5 suggest worse-than-random performance. While Harrell's C-index is widely used, it can be overly optimistic with high levels of censoring. Alternative estimators, such as the Inverse Probability of Censoring Weighting (IPCW) C-index, have been developed to provide a less biased estimate in such scenarios [48].

The Integrated Brier Score (IBS)

The Brier Score (BS) is a strict proper scoring rule that measures the accuracy of probabilistic predictions. For survival models, which predict a probability of survival over time, the BS is calculated at a specific time point ( t ) as the mean squared difference between the observed survival status (1 if alive, 0 if dead) and the predicted survival probability at ( t ) [18]. For a model that predicts a survival probability ( S(t | xi) ) for patient ( i ), the Brier Score at time ( t ) is: [ BS(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N \left( I(ti > t) - S(t | xi) \right)^2 ] where ( I(ti > t) ) is the indicator function that is 1 if the patient's observed time ( ti ) exceeds ( t ), and 0 otherwise.